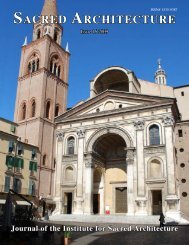

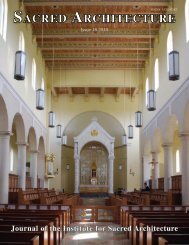

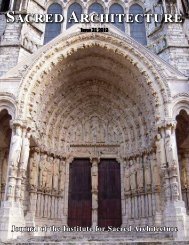

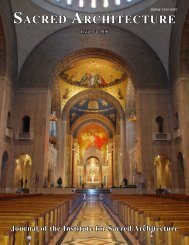

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

Download Issue PDF - The Institute for Sacred Architecture

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

N E W S<strong>The</strong> long awaited revision of the GeneralInstruction of the Roman Missal,which accompanies the Roman Missal, hasbecome available in Latin from the VaticanPress. According to an analysis issued bythe Bishops Committee on the Liturgy, thecomposition of the present Instruction,which replaces the 1975 edition, remainsgenerally unchanged, although there aremany minor and some major alterations.<strong>The</strong> Instruction treats the renovation ofchurches when an old altar, impossible tomove without compromising its artisticvalue, is so positioned that it makes theparticipation of the people difficult. Anotherfixed and dedicated altar may beerected, and the old altar is no longer decoratedin a special way, and the liturgy is celebratedon the new fixed altar. <strong>The</strong> revisedInstruction speaks of a cross with the figureof Christ crucified upon it positioned eitheron the altar or near it and clearly visible,not only during the liturgy but at all times,recalling <strong>for</strong> the faithful the saving passionof the Lord, and remaining near the altareven outside of liturgical celebrations. <strong>The</strong>section on the place of reservation of theBlessed Sacrament has been adjusted andexpanded. Two options <strong>for</strong> the location ofthe tabernacle are given: 1) either in thesanctuary, apart from the altar of celebration,not excluding on an old altar or 2)even in another chapel suitable <strong>for</strong> adorationand the private prayer of the faithful,which is integrally connected with thechurch and is conspicuous to the faithful. Itis more fitting that the tabernacle not be onthe altar on which Mass is celebrated. Anew introductory paragraph has beenadded to the section on sacred images settingtheir use in an eschatological frame: Inthe earthly liturgy, the Church participatesSACRED ARCHITECTURE NEWSin a <strong>for</strong>etaste of the heavenly liturgy, whichis celebrated in the holy city Jerusalem, towardswhich she tends as a pilgrim andwhere Christ sits at the right hand of God.By so venerating the memory of the saints,the Church hopes <strong>for</strong> some small part andcompany with them. Throughout the revisedInstruction there is an increased emphasison the care of all things destined <strong>for</strong>liturgical use, including everything associatedwith the altar and liturgical books.Thus the tabernacle, organ, ambo, priest’schair, vestments, sacred vessels, and all liturgicalelements should receive a blessing.<strong>The</strong> original Latin text can be obtained onthe internet from http://www.nccbuscc.org/liturgy/current/missalisromanilat.htm. An approvedEnglish version has not yet beenmade available.Art can effectively communicate “thehistory of the covenant between God andman and the richness of the revealed message,”John Paul II said at the plenary assemblyof the Pontifical Commission <strong>for</strong>the Cultural Patrimony of the Church inVatican City on March 31, 2000. John PaulII called Christian art “a particularly significantcultural good.” He emphasizedthat “<strong>The</strong> Church is not only the custodianof the past,” and “constantly increases itsown patrimony of cultural goods to respondto the needs of every epoch and culture.”He made further recommendationsabout the quality of new art, that its variousexpressions “develop in harmony withthe Church’s mind in the service of its mission,using a language capable of announcingthe Kingdom of God to all.”<strong>The</strong> Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, MA, was dedicated this past JuneTwenty Cathedrals are being renovatedin the U.S., according to Fr. CarlLast, <strong>for</strong>mer head of the Federation of DiocesanLiturgical Commissions. Amongthe Cathedrals undergoing major renovationsare San Antonio, Detroit, Milwaukee,New Orleans, Memphis, Kansas City (Kansas),Covington, Savannah, Wheeling,Colorado Springs, Lafayette, and Honolulu.Other dioceses such as Houston,Laredo, Oakland and Los Angeles arebuilding new Cathedrals. In addition to repairingroofs, restoring stained glass andartwork, and replacing electrical and mechanicalsystems, many of these projectsare proposing major redesigns of the naveand sanctuary, removal of historic elements,and simplification of iconography.Some of the renovations have met with objectionsfrom preservationists, laity, andother people in their communities. <strong>The</strong>cost of the Cathedral renovations is presumedto be over $150 million, while thetotal cost of new Cathedrals could be wellover $230 million.<strong>The</strong> Church of the Transfiguration wasdedicated on the feastday this June with afestive celebration that included banquets,fireworks, concerts, and specially commissionedmusic and dance. <strong>The</strong> Communityof Jesus, an ecumenical community of 325members in the Benedictine monastic tradition,is located in Orleans, Massachusetts,on Cape Cod. <strong>The</strong>ir new abbey church ispart of the master plan <strong>for</strong> the communityand adds a worship space which accommodatesa full choir, orchestra, a 10,000-pipe organ, procession and sacramentalspaces, and up to 540 worshipers. <strong>The</strong> iconographyplanned <strong>for</strong> the church is rich inbiblical scenes and symbols of faith in castbronze, mosaic, stained glass, marble, limestoneand fresco. <strong>The</strong> apse mosaic, plannedto be 55 feet high, will illustrate the risenChrist and the Four Evangelists. ArchitectWilliam L. Rawn III of Boston, based hisdesign <strong>for</strong> the church on the Early Christianbasilica type at the request of the community,who wished to relate to the timebe<strong>for</strong>e Christianity was divided. <strong>The</strong> 12,000square foot church is built with concretewalls sheathed inside and out with Minnesotalimestone, Douglas fir roof trusses 55feet above the ground, and a Vermont slateroof. <strong>The</strong> liturgical elements of altar, ambo,font and tabernacle were designed byKeefe Associates. Built <strong>for</strong> approximately$10 million, with an additional $3 millionscheduled <strong>for</strong> artwork, it is thecommunity’s desire that the church serveas a model <strong>for</strong> other new churches aroundthe country.4 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>Photo courtesy of <strong>The</strong> Community of Jesus

N E W S<strong>The</strong> Chicago Tribune noted a new trendtowards public religious art in the Chicagoarea. A 33 foot tall stainless-steel sculptureof the Virgin Mary, Our Lady of the NewMillenium, has been trucked from parish toparish <strong>for</strong> more than a year. It even inspiredanother donor to commission a massivestatue of Jesus, the Icon of the DivineMercy, which was unveiled recently at St.Stanislaus Kostka Church in Chicago. It isscheduled to go on permanent display justfeet from the southbound lanes of theKennedy Expressway this fall.Built of Living Stones is the new nameof the Bishops’ Committee on Liturgydocument on art and architecture. <strong>The</strong>draft document, previously entitled DomusDei, was reviewed at the June meeting ofthe BCL and a number of changes weremade, according to Fr. James Moroney, Secretaryof the BCL. After a special Augustmeeting to review the revision, the AdministrativeCommittee considered the documentin September. <strong>The</strong> Committee judgedthe document to be ready <strong>for</strong> full debateand a possible vote at the November meetingof the American Bishops.<strong>The</strong> new entrance <strong>for</strong> the Vatican Museumsis now open, allowing access <strong>for</strong>20,000 visitors a day. In the inaugurationceremony, Pope John Paul II said that thecompletion of this project is proof of theChurch’s will <strong>for</strong> a dialogue between faithand art. This is the most ambitious of thearchitectural projects undertaken by theHoly See <strong>for</strong> the Jubilee year and cost $23million.Fr. Andrew Greeley criticized churchrenovations and modern liturgists in anaddress to the Religious Education Congressin Los Angeles this Spring. <strong>The</strong> novelistand sociologist said that “Un<strong>for</strong>tunately,since Vatican II, a highly authoritarianand doctrinaire perspective has infectedmany liturgists: All the beauty of thepast should be eliminated-only the pulpit,the altar and baptistery, nothing else. Ourbeautiful altars were stripped. With thebattle cry ‘we can’t do Vatican II liturgy in apre-Vatican II church,’ this kind of liturgisthas written off 2,000 years of Catholic artisticexpereience, 2,000 years of Catholicheritage. You tell people when they’re doingthis-removing statues, stations of thecross, vigil lights-that they are offendingthe Catholic people; and they say, ‘if you’reright, you don’t need an opinion poll tomake a decision; you don’t need to consultpeople.’” <strong>The</strong> liturgy, and the celebrationof all the sacraments, he said, quoting PopeJohn Paul II, must be appealing: “We haveto do them so beautifully that people outsidethe Household of the Faith will givesecond thoughts about the Church.”<strong>The</strong> Cathedral of Our Lady of Angels, under construction in Los Angeles, Cali<strong>for</strong>nia<strong>The</strong> Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angelsin Los Angeles is planned <strong>for</strong> dedicationsometime in 2002. <strong>The</strong> $163 millionstructure is built on a massive 64,000square foot foundation – uniquely engineeredto withstand major earthquakes –with a nave one foot longer than St.Patrick’s in New York. <strong>The</strong> monumentalnave will seat 3,000 people and will havean 85 foot tall ceiling, a 200 foot ambulatoryand 24,000 square feet of alabaster inits windows.<strong>The</strong> Charlemagne corridor of St.Peter’s was dedicated in January 2000. Inkeeping with the Jubilee message of conversion,it is a place of recollected prayer,flanked by two lines of confessionals in thismonumental passage that rises to the basilica.“At least in the United States, it seemseucharistic teaching and preaching havebeen neglected, eucharistic adoration hasbeen discouraged outside of the Mass andeven the Mass sometimes lacks the prayerfulattitude it deserves” said Francis CardinalGeorge of Chicago. In his address atthe International Eucharistic Congress inRome this June, the Cardinal said that“there is a growing desire among theCatholic people <strong>for</strong> more clarity and insightinto our eucharistic faith and practice.”Because it is not simply a re-enactmentof the Last Supper, the Eucharist inthe tabernacle is worthy of the same venerationas the Eucharist on the altar duringMass. <strong>The</strong> cardinal said the eucharisticspirituality Catholics are called to live andto share with others must follow the stagespresent in the Mass itself: asking <strong>for</strong>giveness,listening to God’s word, intercedingin prayer <strong>for</strong> others, offering gifts, consecratingthem, sharing in communion andgoing <strong>for</strong>th in mission.During the Eucharistic Congress inRome, Pope John Paul II said that withoutthe Eucharist, it is impossible to understandthe witness of missionaries and martyrsover the last twenty centuries. <strong>The</strong> celebrationof the Eucharist, he said, “is themost effective missionary action that theecclesial community can make in worldhistory.” <strong>The</strong> Pope said the Eucharist givesbelievers “the courage to be agents of solidarityand renewal, responsible <strong>for</strong> changingthe structures of sin in which individuals,communities, and sometimes entirepeoples, are trapped.”Earlier this year, the National Galleryin London featured an exhibition entitled“Seeing Salvation: <strong>The</strong> Image of Christ”,which aimed to put Jesus back at the heartof art history. <strong>The</strong> National Gallery’s director,Neil MacGregor, in explaining the reason<strong>for</strong> the exhibit said that Christianity “isthe fundamental element of western culture.<strong>The</strong> vast majority of these pictures arefrom British collections: it is our job to remindthe public that it owns these astonishingthings.”John Paul II’s Letter on the anniversaryof Aachen Cathedral referred to the tiesthat unite the Catholic community spreadover the world with the Church of Romeand the Holy City of Jerusalem. <strong>The</strong> Cathedral,dedicated to the Virgin, was built in800 at the request of Charlemagne, whowas crowned that same year in Rome byPope Leo III. Aachen Cathedral also containsfour precious relics that Jerusalemgave Charlemagne and that recall “withPhoto by Kirsten Kiser<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 5

N E W SRendering of proposed changes to Milwaukee’s Cathedral ofSt. John the Evangelistprofound reverence events in thehistory of salvation.” <strong>The</strong> fourrelics are fragments of the newbornJesus’ diapers, the clothJesus wore around his waist onthe cross, the dress Mary wore onChristmas Eve, and the cloth ofJohn the Baptist’s beheading.<strong>The</strong> Archdiocese of Milwaukeehas unveiled a $10 millionplan <strong>for</strong> the renovation of the Cathedralof St. John the Evangelist.<strong>The</strong> plan <strong>for</strong> the landmark 1847structure, which includes aglassy atrium, a cloistered courtyardand extensive changes tothe cathedral’s sanctuary, drewpraise from city officials andcriticism from others. Along withreplacing the church’s outdatedmechanical, sound and lightingsystems, the original sanctuarywill be removed, and a new altarwill be placed in the middle ofthe nave. Seating capacity, now740, would be increased to morethan 900, with chairs arranged in theround. <strong>The</strong> architect <strong>for</strong> the project isHammel, Green & Abrahamson and the liturgicalconsultant is Rev. Richard Vosko.<strong>The</strong> 1931 statue of Christ the Redeemerthat overlooks Rio de Janeiro is being restored.<strong>The</strong> project is being funded by theBrazilian Environmental <strong>Institute</strong>, thenewspaper “O Globo,” and Banco Real. Atitanium mesh will be placed in the interiorof the 125 foot statue to conduct electriccurrent, preventing salt from damagingChrist’s robe.Brazil’s oldest church has been rediscoveredon a hill considered sacred by theinhabitants of Porto Seguro. Vestiges of theChurch of St. Francis, constructed between1503 and 1515, were discovered in Marchof this year. Up until the 1970s, Mass wascelebrated on the hill, although no oneknew exactly where the ruins were buried.Researchers of the University of Salvadorof Bahia made the find of the outside walls,the base of the belfry and the main altar.Chronicles of the time refer to the Churchof St. Francis as being part of the first urbannucleus established by the Portuguese inBrazil.<strong>The</strong> mystery of beauty was the subjectof a Lenten Meditation addressed to PopeJohn Paul II. Fr. Cantalamessa, the Capuchinwho delivered the series of meditations,quoted an Orthodox author: “God isnot the only one covered in beauty. Evilimitates him and makes beauty profoundlyambiguous.” Referring to Genesis, hespoke of Eve, who was seduced by beauty;she realized the fruit was beautiful, desirable,aesthetically attractive. This meansthat, although truth is always beautiful,beauty is not always true. This ambiguityis overcome by Jesus, who redeemedbeauty by depriving himself of it <strong>for</strong> thesake of love in the mystery of his passion,death and resurrection. In this way, the Sonof God demonstrated that there is only oneprecious thing: the beauty of love thatpasses through the cross and is purified bythe cross. Rather than closing one’s eyes be<strong>for</strong>eambiguous beauty, they must beopened wide to look at the transfiguredChrist. Fr. Cantalamessa ended by paraphrasingFyodor Dostoyevski: “It won’t bethe love of beauty that saves the world, butthe beauty of love.”<strong>The</strong> congress “Abbeys and Monasteriesin Europe’s Roots” was held inConques, France, on June 8, 2000. It waspart of the “Campaign <strong>for</strong> a Common Patrimonyof Europe,” promoted by the EuropeanCouncil, and was organized by thePontifical Council <strong>for</strong> Culture and the EuropeanCenter of Art and Medieval Civilization.Pontifical Council President CardinalPaul Poupard called the congress an invitationto study the value and importanceof abbeys and monasteries in the making ofEurope. Moreover, through this initiative,the Vatican reaffirmed its profound interestin Europe’s cultural and religious patrimonyand its desire to protect and make itaccessible to the greatest possible numberof people.A Second Floating Russian OrthodoxChurch has been provided by the Catholiccharity “Aid to the Church in Need”. <strong>The</strong>first such ship has been serving on theVolga River since May, 1998.On July 11, 2000 a second wasconsecrated in Volgograd inthe name of St. Nicholas by theRussian Orthodox Archbishopof Volgograd and Kamyshin.<strong>The</strong>se church-boats are in thespirit of the 35 “chapel cars”instituted by “Aid to theChurch in Need’s” founder, Fr.Werenfried van Straaten, the“bacon priest,” in Germany afterWorld War II. <strong>The</strong> agency isworking with the Orthodox inresponse to the desires of theHoly Father <strong>for</strong> the unity ofChristians. At present, its workstands as one of the few examplesof successfulecumenism with the RussianOrthodox.Over 3,000 artists met withthe Pope on the feast ofBlessed Fra Angelico. <strong>The</strong> artistslistened to the Pope’s callto conversion in the most difficultwork of art of all: the sculpturing ofChrist’s features on the stone of one’s ownheart. “<strong>The</strong> artist who can do this profoundlyis the Holy Spirit, but he requiresour correspondence and docility,” thePope said. At this point, the Pontiff intoneda beautiful song about Michelangelo’s cupola.Everyone present followed the wordswith attention, gazing on the beauty of theBasilica transfigured by the clear middaylight. “Seen from outside, it seems to curveagainst the sky over a community recollectedin prayer, as is the love of God. Fromwithin, instead, with its vertiginouslaunching to the heights, it evokes thework of elevation toward the full encounterwith God.” John Paul II proclaimedBlessed Fra Angelico patron of artists onFebruary 18, 1984.New England Jesuits are consideringrestoring the historic South End BostonChurch of the Immaculate Conception,fourteen years after they had dismantledmany of its artistic elements. <strong>The</strong> BostonGlobe reports that the Jesuits are “drivenby concerns over the structural soundnessof the church’s roof and by the fact that aonce-dying congregation is now flourishing.”While the Renaissance Revival church,designed by Patrick C. Keely in 1861, stillhas a 19th century pipe organ consideredone of the best in the world, 30-foot-highetched-glass windows, and rosette-strewnpale blue coffers on a barrel-vaulted ceiling,many elements were lost in the renovationfourteen years ago. Pews wereripped out and destroyed, the pulpit brokenand put in a closet, the communion railhidden, and Stations of the Cross andpaintings of Jesus, St. Andrew and St. John6 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>Photo courtesy Archdiocese of Milwaukee

emoved. <strong>The</strong> restoration would be especiallysignificant in view of the long and bitterlegal battle over the Jesuits’ right to removemuch of the building’s interior. In1991 they won a precedent-setting rulingfrom the state Supreme Judicial Court,which held that it was unconstitutional <strong>for</strong>the city to regulate changes to a church interiorby declaring it a historic landmark.Mount Sinai is claimed to have beendiscovered at Mount Har Karkon, in the IsraeliNegeb desert. In his book, Mysteriesof Mount Sinai, Emmanuel Anati writes,“we found the altar and 12 boundary postsat the foot of the mount. Those 12 pillarsare mentioned in the pages of the Bible [Ex24:4]. <strong>The</strong>n, some 60 meters away, the remainsof a Bronze Age camp. This is alsomentioned in the Old Testament . . . In aprotruding commemorative burial moundwas an altar, and underneath, the vestigesof a fire. On the altar there was a whitestone in the shape of a half moon, the symbolof the moon god Sin.”Austrian archeologist Renate Pillingerof the University of Vienna revealed the discoveryin Ephesus of Christian cave paintingsrepresenting St. Paul. In 1995, a cavewas discovered a few kilometers away fromthe city’s ruins. Inside the cave, there arepaintings depicting the Transfiguration anda sequence inspired by the Acts of theApostles, refering to St. <strong>The</strong>cla and St.Paul’s preaching. Paul’s portrait is one ofthe best-preserved frescoes in the cave. It istoo early to state that the cave’s discoveryarcheologically confirms Paul’s presence inEphesus, which other sources, such as theBible, consider indisputable.<strong>The</strong> Basilica of the Agony in the Gardenof Gethsemani in Jerusalem wasrobbed in February. <strong>The</strong> robbery in the Basilicawas well planned. Two early twentiethcentury bronze deer were removed.<strong>The</strong> statues were life-size and located highin the tympanum of the building’s façadeat the foot of the cross.Cardinal Adam Maida plans to spend$20 million during the next three years todraw Detroit area Catholics back toBlessed Sacrament Cathedral in Detroit.Renovation plans include the addition of anew glass-and-steel wing to the north sideof the neo-Gothic church. <strong>The</strong> wing willbe near the main altar and flood the centerof the gray limestone building with sunlight.To meld the old with the new, anenormous stained-glass window will besuspended in the heart of the new wing.Stone arches around the altar will be trans<strong>for</strong>medby curving metal-mesh sheets to<strong>for</strong>m a multilayer abstract backdrop <strong>for</strong>the Mass. Seating will expand from 800 to1,200. Much of the renovation budget isset aside <strong>for</strong> repairs. <strong>The</strong> badly-needed replacementof the roof is almost finished.Archdiocesan officials and architectGunnar Birkerts are finalizing buildingplans and deciding where a redesigned altar,pulpit and archbishop’s chair will beplaced. <strong>The</strong> major portion of the new constructionis expected to begin in May 2001and end by early 2003.Fr. Rasko Radovic, parish priest of theSerbian community of Trieste, in Italy, denouncedthe destruction by Albanians ofmore than 80 Orthodox churches andmonasteries in Kosovo, since the arrival ofthe U.N. administration. Some of thebuildings dated back to the 13th century<strong>The</strong> $65 million Pope John Paul II Cultural Center in Washington, D.C. is expected toopen in November.N E W Sand were part of a considerable artistic andcultural heritage. Fr. Radovic said he didnot understand why the UNESCO, whichwas so active during the Balkans War, hasremained silent.CONFERENCES &EXHIBITIONSReconquering <strong>Sacred</strong> Space 2000: <strong>The</strong>Church in the City of the ThirdMillenium will be held at the PontificalUniversity of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome,Italy, December 1 and 2, 2000. <strong>The</strong> conferencewill include lectures by an internationalgroup of architects, theologians, andhistorians on the contemporary renaissanceof Catholic architecture. An exhibition onnew traditional Catholic churches will beheld at Palazzo Valentini December 1-20,and a catalog of the exhibition will be publishedby Il Bosco e la Nave. <strong>The</strong> conferenceand exhibition is being sponsored by theAgenzia per la Citta, publisher Il Bosco e laNave and the <strong>Institute</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>.For in<strong>for</strong>mation please contactdstroik@nd.edu or roscri@flashnet.it.Peter and Paul: History, Devotion, andMemories of the First Centuries, is an exhibitionrunning from June 30 until December10, 2000 at the Cancelleria Palace inRome. It will focus on the time when thetwo apostles were in Rome. <strong>The</strong> exhibitionwas organized by the Pontifical Council <strong>for</strong>the Laity and the Directorate of Monumentsof Vatican City. Heavy assistance iscoming from the Friendship Meetingamong Peoples, an organization which ispart of the ecclesial movement Communionand Liberation, which <strong>for</strong> years has organizedtravelling exhibitions on historicaltestimonies of the faith. Vestiges from thecatacombs and basilicas: commemorativetablets, sarcophagi and gilded glass aresome of the items on display. Objects werechosen to reflect the life and motivations ofearly Christians: their relations with thepre-existing Jewish community in Rome;their confrontation with the polytheistworld; their vision of the beyond; movingtestimonies that, as Francesco Buranelli, directorof the Vatican Museum recalled, revealhow the devotion to martyrs was alreadydeeply rooted. <strong>The</strong> Eternal Cityowes virtually everything to Peter andPaul, explained Archbishop CrescenzioSepe, secretary of the Vatican Jubilee Committee.“Without the message of these twoapostles, the history of this city would haveended, in all probability, at the end of theRoman Empire. Indeed, without knowingPeter and Paul, one cannot understand allthe signs that the Church has left in streetsand squares of the city of Rome.”<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 7Photo by James McCrery

F E A T U R ECATHOLIC ARCHITECTUREAND NEW URBANISMAN INTERVIEW WITH ELIZABETH PLATER-ZYBERKElizabeth Plater-Zyberk is dean of theUniversity of Miami School of <strong>Architecture</strong>and a partner in the design firm Duany Plater-Zyberk and Company. She is an ardent promoterof New Urbanism, a movement that has beensuccessful in designing new communities astowns rather than subdivisions and revitalizingolder communties. Among Duany Plater-Zyberk’s best known projects are the towns ofSeaside in Florida, Kentlands in Maryland anddowntown West Palm Beach, Florida, alldesigned to be pedestrian-oriented with schools,churches, libraries and shops within walkingdistance of homes.<strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>: Why is itimportant <strong>for</strong> America’s towns, cities, andcommunities to include significant churchbuildings?Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk:Churches are an importantplace <strong>for</strong> community lifetoday. <strong>The</strong> very large,suburban congregationwith multiple activities isproviding a focus <strong>for</strong>community in a landscapewhich otherwise does nothave one. In the poor urbanneighborhood, the churchprovides any number ofcommunity supportservices, including outrightsocial services such asfeeding the hungry. Acrossthe range of communities,churches are playing a veryimportant role incommunity life and itsquality.SA: How does the architectureof the churchwant to reflect that?EPZ: <strong>The</strong> church as aplace of civic gatheringJames C. McCrerycertainly should be reflected in its architecture.A number of issues are important inchurch design today in the various denominations,but the buildings also need toreflect their role in the community.SA: Why, if at all, should Catholics beinterested in New Urbanism?EPZ:Many aspects of New Urbanismhave to do with the goals of religion in general,but some in particular are related toconcerns which grow out of a RomanCatholic spiritual and intellectual foundation.I will offer three topics as examples: environment,society, and economy. <strong>The</strong> firstis environmental, and responsible stewardshipis an inherent part of understandingour role on the planet. Being a good stewardof the environment is very much a partAerial view of proposed village center with a churchof the New Urbanism’s core value system.I found it gratifying to read recently thatsome priests are preaching that urbansprawl is irresponsible.<strong>The</strong> second topic, perhaps more obviousto Catholics, is the social context. New Urbanismis concerned with structuring thephysical environment to promote a senseof community while enabling individualautonomy and empowerment, whether allowingchildren to walk to school or seniorsto live independently within theirhome community. An important aspect ofcommunity is interdependence and connectivity.By the proximity and interactionfostered by the physical environment, oneunderstands the role one plays in the community.<strong>The</strong> third topic regards the economiccontext. <strong>The</strong> New Urbanismproposes a framework<strong>for</strong> an economic systemthat is supportive ofindividuals in community.<strong>The</strong> economic picture isone of collaboration, diversity,and establishingor enabling institutions,the workplace and commercethat facilitate thecommunity and ensure itslongevity.We’re living in a timein which commercial activityis extremely shortlived.Main Street is dyingat the hands of cannibalisticretail development.This does not promotea sense of community,and is not related toany sense of responsibility<strong>for</strong> people. We think thephysical environment canreflect a better way, a betterphilosophy.8 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>Photo : Duany, Towns and Town-Making Principles, 1991

F E A T U R EPhoto courtesy Duany Plater-Zyberk and Co.Masterplan <strong>for</strong> the Kentlands, Maryland, by Duany Plater-Zyberk and CompanySA: What role do you see the CatholicChurch being able to play in aiding the designor development of new towns?Should it have a role in it at all?EPZ: That is a very interesting question.I think the Catholic Church can playan important role in the revitalization ofneighborhoods. But I am not sure that itneeds to play an initiating role in newplaces, except insofar as the Church may beinterested in building a kind of ideal community.<strong>The</strong>re is a design role that should beplayed by the Church exemplifying thecivic role, the community-focused role thata Catholic Church plays in neighborhoods.And the biggest impediment to this designrole is dimensions. From my own experienceof designing one church in a suburbanpart of Miami and my understanding ofcommon practice, I find that these churchesare very big.<strong>The</strong> big, suburban church that we designedhad to seat 800 in the main sanctuaryand then be able to expand to 1,000 or1,200 <strong>for</strong> special occasions in the Churchyear. Of course, you have to have parking<strong>for</strong> all of those people. <strong>The</strong>n usually thereis a small office component, and a communityroom, and possibly even a school.Consequently, the church campus is verylarge.Even in their smallest permutations,these campuses require an enormous siteand the isolation of buildings amidst parkinglots, like other institutions in suburbia.However, large dimensions can be mitigated.<strong>The</strong>re are alternative solutions. Inthe new traditional neighborhood, the NewUrbanism, the parking is shared with commercialestablishments that are not usedmuch at night or on Sundays. In Canada,public and parochial schools share facilities.<strong>The</strong>y are developed by the governmentand Church, and they share the bigticket items, things like libraries or playingfields, that also happen to take up a lot ofspace.In several Canadian projects, we foundthere was a feasible way to put schools togetherin the greenbelt between the severalneighborhoods from which they draw theirstudents, who can walk to school. <strong>The</strong> institutionon the edge, rather than at thecenter of the neighborhood, is the least disruptiveof its walkability.In the New Urbanism, that is, in a compact,pedestrian-oriented community, dimensionsand measures are extremely important.<strong>The</strong> way we build churches nowsometimes seems contradictory to the goalof making these places pedestrian-friendlyand acceptable.In older neighborhoods where thereusually are already churches, the initiativesmay have less to do with the buildingitself reacting to its role in the physical fabricand more with revitalization. Renovationshould not be accomplished in such away that the building becomes defensiveagainst hostile surroundings, or that it beginsto take apart the neighborhood bysuburbanizing the urban fabric around it.I have often thought that wealthy, suburbancongregations could adopt congregationsin the inner city and do some concreteprojects, like building and rebuildinghousing <strong>for</strong> people in those places. I amsure that this already goes on in variousparts of the country. But all involved haveto pay attention to the fact that the structureof the physical environment is important.Not only <strong>for</strong> increasing the economicvalue of the place over time, but to promotegood community.SA: From your experience with churchprojects, what are some of the issues in designinga new church building, whether itbe in an established neighborhood or in anewly planned development?EPZ: We designed a little church in aneighborhood in Miami. It was initiated bya pastor who thought that if he franchisedsmaller chapels, creating what he called“missions” within his large parish then hemight be able to influence behavior inthose areas which weren’t within walkingdistance of the big church.So, we designed one on a 50 x 100 foot<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 9

F E A T U R EStreet facade of Mission San Juan Bautista, Miami, Florida, by Duany Plater-Zyberkand Company.lot in a traditional style. It is very simple,its vernacular details refer to the colonialprototype of Puerto Rico, the predominantethnicity of the neighborhood. Afront building at the sidewalk has a smallprayer chapel and an office <strong>for</strong> social services.Above the entry area is a smallapartment <strong>for</strong> a concierge, a caretakerkeeping an eye on the neighborhood. Behindthis is a courtyard, as you might findin a traditional Caribbean or Mediterraneanbuilding, and then beyond that is thenave, which seats about 200.SA: How many of these franchisedchapels are in this parish?EPZ: <strong>The</strong> intention was to have four.SA: Amazing, and how large is theparish?EPZ: It spreads out over a large areathat has both industrial and residentialneighborhoods in it.SA: That is a fine example of originalthinking on the part of pastors.EPZ: <strong>The</strong> pastor, Father JoseMenendez, a Cuban with a terrific amountof charisma, is at work in this parish withstruggling but very energetic immigrantneighborhoods. On his own initiative, heraised the money to buy a $40,000 lot. <strong>The</strong>lot was sandwiched between a café withloud, bawdy music and a crack house.<strong>The</strong> first thing he did was erect a woodencross and put a sheep in the lot, becausethis was going to be called “Mission SanJuan Bautista.” <strong>The</strong> cross and the sheepboth survived there <strong>for</strong> many months. Heconvinced various people who felt a connectionto this neighborhood, the ownersof the local grocery store, and some contractorswhose employees live in thisneighborhood, to contribute their timeand money. It was built entirely with donationsof materials, time and money. Ittook four or five years to complete.Father Menendez’s great belief was thatthe church should be filled with art and beas embellished as any other church. Hedidn’t like the industrial lamps that wespecified, so he began seeking out thechurch furnishings himself. <strong>The</strong>re is a fountainin the courtyard, which also serves as abaptismal font, constructed with marbleslabs he salvaged. He thenconvinced a Cuban sculptor todo a small statue of Saint Johnthe Baptist that stands on thefountain. He convinced apainter to do a mural on theceiling of the sanctuary. It is aheavenly scene full of peoplefrom the neighborhood.<strong>The</strong> church design symbolizesthe progression from theprofane to the sacred. Aftercrossing a short front yard ofgravel, the desert, one entersthe front building and walksover a mosaic floor of a coiledsnake with an apple in itsmouth, depicting the Gardenof Eden, the first sin. You arestepping on the snake as youbegin your procession fromthe profane to the sacred.Father Menendez found aJewish artist from MiamiBeach to do this mosaic ofEden. <strong>The</strong> project manager,Oscar Machado, is of a thirddenomination. So, here wehave a piece of art commissioned<strong>for</strong> free by a Catholicpriest, executed by a Jewishartist, with a man of anotherdenomination as the art director, all lookingat Pompeiian mosaics <strong>for</strong> inspiration.SA: That is a great American story.What are things <strong>for</strong> the patron, thecongretation, and architect to be concernedabout in the commissioning of a church?Anything absolutely crucial?EPZ: Outside of the urban context,there is one crucial issue. That is the conversationor conflict between tradition andmodernism. In the Church this conversationexists, and it is marked by conceptionsof “pre-Vatican II” and “post-Vatican II.”<strong>The</strong>re is a dominant directive towardsopenness, post-conciliarism and modernism.<strong>The</strong>re are design advisors within thechurch at large who will be very explicitabout what this post-conciliar attitudemeans: “don’t do what you would havedone be<strong>for</strong>e,” “don’t enter on axis,” “thecross should not be on axis,” and so on. Onthe other hand, many people still have aninclination to the traditional <strong>for</strong>m and avery emotional attachment to the history ofthe church, its ceremonies, its rituals, andits buildings.<strong>The</strong> modern/traditional discussion isunavoidable and very challenging. It requiresa sorting out of intellectual goalsand the emotional or visceral effect that aspace can have on a people’s spiritualstance. Obviously that wasn’t so much achallenge in the old Church. But I findthat truly challenging today, not just interms of design, but in terms of dealingwith the politics of the client and workingView of the courtyard of Mission San Juan Bautista10 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>Photo courtesy Duany Plater-Zyberk and Co.Photo courtesy Duany Plater-Zyberk and Co.

F E A T U R Eciding what to take back in order to fosterchange. But a lot of people do feel the lossof historical attachment. Certainly, ourteaching about the Church and the body ofChrist on earth has to do with its history.Christ existed at a very specific time in history,creation was time-based. Every religionbrings along its history, so why not allowthat physical continuity to occur?By the same token, we shouldn’t precludethe spiritual opening that discoveryand the new can provide.So, it is still not an easy time to figurethings out stylistically. We should certainlyhave the opportunity to rebuild or to carryon the traditions of building of a specificplace. <strong>The</strong> exhibit, Reconquering <strong>Sacred</strong>Space, that opened in Rome in November1999 has some terrific examples of traditionaldesign, but it represents a fraction ofchurch building today.SA: Do you mean to say that it is okayin America to evoke an architectural styleor place in time that isn’t American?EPZ: Yes, or even one that is traditionallyAmerican. Our early Puritan heritage,religiously based, produced some wonderfulmodels of churches that should be acceptableto us <strong>for</strong> reinterpretation. At varioustimes in American architectural historywe referred to earlier times <strong>for</strong> spiritualreasons. American Neo-classicism connectedthe new land to the democracy ofancient Greece. In the early Renaissancethe Italians were excited by the <strong>for</strong>ms of aprior time that was pagan, cleverly integratingancient classical elements with theRoman Catholic imagery of the period.<strong>The</strong>re is a rich tradition of Christian apwithany kind of committee.SA: From your experience canyou say that working with committeesis beneficial? Are you able tocompare working with a single patronor a particularly strong leader ofa committee versus a band of semiinterestedparishioners? Do youhave a preference?EPZ: I haven’t had the fullrange of experience. FatherMenendez was basically a sole client.Father Greer, the Good Shepherdpastor, did have a committee,but he played a strong leadershiprole. <strong>The</strong> committee was eager to expeditethe church because <strong>for</strong> 12years they’d had only a communityhall.I could give one word of adviceabout committees. Bring the conversationto intellectual issues and principlesand be very explicit as a designerabout what different <strong>for</strong>msrepresent. Be very involving. It isnot always easy <strong>for</strong> designers to explainwhat they do, but the more rationalyou can be, the better.SA: Fantastic advice. Let’s goback to your comment earlier aboutdimension. Do parish priests and committeesthink too grandly when they commissionchurches that must seat 800, stand1,200 and accommodate 100 priests in thesanctuary? Would it be better <strong>for</strong> communitiesto have several small churches orparishes than one large one?EPZ: Well, in Miami the Archdioceseis a wise steward and does not let parishesbegin projects be<strong>for</strong>e they are ready to pay<strong>for</strong> them. In terms of size, I do think thatsmaller would be better. But locations andthe shortage of priests can create problems.SA: A question on style. What do youthink about the way the Catholic Churchhas planned and designed its church buildingsduring the last 30 years?EPZ:This has not been an outstandingtime <strong>for</strong> church architecture or any otherkind of architecture. That is a statementthat stands alone. Maybe we could lookupon this as a transitional time. We wereasked to deal with all sorts of new issuesafter the Council, and now we are in ashakeout time. Hopefully we can learnfrom those first attempts and ef<strong>for</strong>ts.SA: I’ve attended other conferenceswhere it has been suggested that afterVatican II in the United States there was avery good atmosphere architecturally anddesign-wise <strong>for</strong> Iconoclasm to thrive. Haveyou ever thought about a possible link; thatperhaps the two phenomena fed eachother, resulting in a dearth of architecturaland artistic expression?EPZ: That is why I am being kindabout calling the last thirty years a “periodof transition”. Because, perhaps you needthese rough moments of discarding and de-Good Shepherd Catholic Church, Miami, Florida, by Duany Plater-Zyberk and Co.propriation of symbols from prior culturesand prior spiritualities. That is an age-oldkind of inclusivity or appropriation that wedon’t seem to be allowing ourselves now.One must acknowledge that <strong>for</strong> all thehopefulness of multiple interpretationsthat the abstractions of modernism promotes,the turning away from representation,from evolution, is not an enrichmentat all.SA: So, then what should be done withall of these abysmal churches out there?What do you have to say to the priest whohas been committed by his bishop to a parishthat isn’t going to build anything soon,but who has an empty hall in which to celebratethe Mass?EPZ: This is actually the design challengeof our time, not just in the realm ofchurch architecture. A great deal has beenbuilt in recent decades which doesn’t lenditself to addition, renovation, and enhancement.It is so autonomous, so aggressivelyindividualistic that it is hard to imaginehow to engage it. This is something thatwe need to be teaching designers: how todeal with the suburban context, individualistic<strong>for</strong>ms and buildings that are far apartfrom each other with little hope of spatialrelationships. In the case of such a church,a parish priest should look <strong>for</strong> a very sensitiveand clever designer who can begindealing with the situation incrementally.James McCrery is an architect in Washington,D.C.Photo courtesy Duany Plater-Zyberk and Co.<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 11

A R T I C L E SANTONI GAUDI: GOD’S ARCHITECTMichael RoseAll the great cathedrals have taken centuriesto complete. <strong>The</strong> Cathedral ofthe Sagrada Familia (Holy Family) inBarcelona, Spain, is no exception. Begun in1883, only half of this imposing church isnow complete. Construction work, however,steadily continues as donations keepcoming in to support the work. Architectsestimate that the church will take at leastanother 40 years to complete. Some say itcould take as many as 150 years.Sagrada Familia is the most renownedbuilding designed by Spanish architectAntoni Gaudi, whose cause <strong>for</strong>beatification was opened last year bythe Cardinal Archbishop ofBarcelona. <strong>The</strong> cathedral is a testamentto the architect’s faith. In someways, Gaudi’s Barcelona church resemblesthe great cathedrals of theMedieval age: Sagrada Familia wasbased on the plan of a Gothic basilicawith five naves, a transept, an apse,and ambulatory.It is designed with soaring towers,capped by spires, and is repletewith dense symbolism throughoutthe structure. Gaudi, however,wanted to create a “20th century cathedral,”a synthesis of all his architecturalknowledge with a visual explicationof the mysteries of faith. Hedesigned façades representing theNativity, Crucifixion, and Resurrectionof Christ; and eighteen towers,symbolizing the twelve Apostles, thefour Evangelists, the Virgin Maryand Christ. <strong>The</strong> Christ tower, the tallest,when completed will stand some500 feet high. To date, eight of theeighteen towers are completed. Eachis of a unique spiral-shape coveredin patterns of Venetian glass and mosaiccrowned by the Holy Cross.God’s Architect“My client can wait,” was Gaudi’sgenial response to his helpers whendelays occurred due to his constantchanges to the original plans. Gaudi alwaysacknowledged that his ultimate clientwas God, whom he felt was in no hurry.<strong>The</strong> architect wanted the finest and mostperfect sacred temple <strong>for</strong> his client. Hetruly worked ad majorem Dei gloriam, <strong>for</strong> thegreater glory of God.Gaudi, known as “neo-Medieval” in hisday, developed a unique style of building.His work is characterized by the use ofnaturalistic <strong>for</strong>ms, and his approach cameto be known as the “biological style.”Sagrada Familia is known <strong>for</strong> its conicalspires, parabolic arched doorways andfreely curving lines. As in most of his work,Gaudi has created the impression the stoneused was soft and modeled like clay orwax.Gaudi directed the construction of thechurch from 1883 until his sudden death in1926. He became so involved with thechurch that he set up residence in his onsitestudy and devoted the last 14 years ofhis life to this most important of all hisprojects. He regarded Sagrada Familia as agreat mission. On June 7, 1926, Gaudi wasConstruction of Sagrada Familia continueshit by a street car. Three days later he diedat the age of 74.When he died, the people of Barcelonapopularly proclaimed him a “saint.” <strong>The</strong>rewas great commotion. Even though helived in a reserved manner, removed fromthe world, rumor of his sanctity had alreadyspread. No newspaper, not even themost virulently anti-Catholic, attackedhim. <strong>The</strong> director of the Museum of theBarcelona Archdiocese wrote an article callingGaudi “God’s Architect.” His architectureis an expression of his Christian commitment.From the very beginning of the20th century Sagrada Familia became anicon of the city of Barcelona, just as theEiffel Tower is an icon of Paris. And afterthe architect’s death, the people ofBarcelona regarded him as a patron of theirgrand city.<strong>The</strong>re have even been documented conversionsresulting from the architecture ofSagrada Familia. <strong>The</strong> most prominent involvedtwo Japanese men. One is architectKenji Imai. He arrived in Barcelona twomonths after Gaudi’s death. He was travelingall over the world to meet the great architectsof the day, but by the time hereached Barcelona Gaudi was deadand buried. Even so, Imai was notdisappointed. Sagrada Familia madesuch an impression on him that,when he became a professor in Japanhe gave several lectures on Gaudiand, finally, converted to Catholicism.<strong>The</strong> other convert is sculptorEtsuro Sotoo, who worked <strong>for</strong> yearsfashioning statues on Barcelona’s cathedral,and ultimately became aCatholic.<strong>The</strong> Work ContinuesAfter Gaudi’s death, work continuedon the church until 1936. <strong>The</strong>sewere the days of the bloody SpanishCivil War. <strong>The</strong> Communists, whohated all things Catholic, set fire toGaudí’s study which held his notesand designs <strong>for</strong> Sagrada Familia.Many of these were destroyed, butthe project resumed in 1952 using thesurviving drawings and models tocontinue the work. Today, the constructedpart is open to visitors aswell as the small museum that exhibitsGaudi’s original plans and models.Later this year, Cardinal RicardMaria Carles of Barcelona will inaugurateSagrada Familia with a solemnMass on December 31, the Feastof the Holy Family. <strong>The</strong> 150-foothighcentral nave is scheduled to betotally roofed by that date. Referring to theBasilica’s beauty, Cardinal Carles told aSpanish newspaper: “<strong>for</strong> me it transmits anevangelical message, very much Gaudi’sstyle.” Perhaps <strong>for</strong> that reason, AntoniGaudi is regarded still as “God’s Architect.”Michael S. Rose is editor of the St.Catherine Review and author of <strong>The</strong> RenovationManipulation: <strong>The</strong> Church Counter-Renovation Manual. He can be reached byemail at: mrose@erinet.com.12 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>

THE SPIRIT OF MEDIATOR DEIA R T I C L E STHE RENEWAL OF CHURCH ARCHITECTURE BEFORE VATICAN IIIt is generally thought byliturgists and theorists ofliturgical architecture thatlittle occurred in the area ofrenewal of church designbe<strong>for</strong>e the Second VaticanCouncil. <strong>The</strong> architecturalmodernism of the post-Conciliarera has there<strong>for</strong>e oftenbeen thought to representthe Council’s artistic intentions.However, be<strong>for</strong>e theCouncil, church architecturehad already undergone significantchange in responseto the Liturgical Movementand Pius XII’s encyclicalMediator Dei (1947). Statementsof popes, architects,and pioneers of the LiturgicalMovement point to a liturgicaland architecturalcontext which presents avastly different approach toarchitecture than the starkinteriors presented by manyarchitects after the Council.Despite the prevailing beliefthat architectural modernismwas the only availableoption <strong>for</strong> the modernchurch, the early twentiethcentury provides considerableevidence of representational,historically-connectedand often beautifularchitectural designs responsiveto the same principlescanonized in thedocuments of Vatican II.SacrosanctumConciliumgrew directly out of theideas expressed in the LiturgicalMovement and MediatorDei, and must be read inthat context to convey a fullunderstanding of the authentic spirit ofVatican II regarding liturgical architecture.<strong>The</strong> Liturgical Movement inAmericaArchitects and liturgists of the earlytwentieth century proclaimed an almostunrelenting criticism of Victorian ecclesiasticaldesign. It was, they argued, the productof a pioneer mentality in American Catholicismin which poor and under-educatedpatrons hired uninspired architectsand purchased low quality mass-producedliturgical goods from catalogs. In response,Denis McNamaraVictorian ecclesiastical design: St. Mary’s Church, New Haven,Connecticut by James Murphy, 1874architect-authors like Charles Maginnisand Ralph Adams Cram called <strong>for</strong> moreadequate ecclesiastical design and furnishings.At the same time, the LiturgicalMovement began to establish its presencein the United States. <strong>The</strong> movement’s leadersbelieved that American liturgy had sufferedunder an individualist pioneer mentalityas well, leading to a minimalist liturgicalpractice and general lack of understandingabout the place of the Eucharisticliturgy in the life of the Church. <strong>The</strong> LiturgicalMovement mingled with the pre-existingtraditionally-based architectural designmethods of the 1920sand 1930s, and over the nextseveral decades wroughtconsiderable improvementin ecclesiastical design.One of the earliest Americanmouthpieces of the LiturgicalMovement was theBenedictine periodical OrateFratres, a journal of liturgyfounded by Benedictinemonk Virgil Michel andbased on his studies of philosophyand liturgy in Europein the 1920s. One of thejournal’s first articles, entitled“Why a LiturgicalMovement?,” was written byBasil Stegmann, O.S.B., whowas later to become an activeparticipant in the Americanliturgical discussions. 1 Heexplained the need <strong>for</strong> liturgicalre<strong>for</strong>m to an Americanchurch still generally unawareof European developments.Stegmann cited PiusX’s 1903 Motu propio whichexpressed the pope’s “mostardent desire to see the trueChristian spirit flourishagain” and which claimedthat “the <strong>for</strong>emost and indispensablefount is the activeparticipation in the mostholy mysteries and in thepublic and solemn prayer ofthe Church.” 2 Stegmanncalled <strong>for</strong> all members of theChurch to become intimatelyunited with Christ and <strong>for</strong>m“what St. Paul calls mysticallythe body of Christ.” <strong>The</strong>movement’s new concentrationon the baptistery, altarand improved participationnaturally lead to changes in church design.Other features of the Liturgical Movementincluded a “profound spirit of fidelity tothe Church,” a patristic revival, a new interestin Gregorian chant, the use of the Liturgyof the Hours <strong>for</strong> laypeople and themore frequent following of Latin-vernacularmissals. 3<strong>The</strong> early proponents of the LiturgicalMovement sought to improve liturgicalquality by putting the primary features ofthe liturgical life in their proper place. Previously,the prevailing individualist approachto liturgy meant that worshippers<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 13

A R T I C L E Snot only failed to follow along with the liturgicalaction, but often busied themselveswith other things, often pious enough, butunrelated to the Eucharistic liturgy. 4 Withrelatively little interest in making the liturgicalaction visible to the congregation, altarswere sometimes set in deep chancelsand attached to elaborate reredoses thatoverwhelmed their tabernacles. Variousdevotional altars had their own tabernacles,which quite often doubled as statuebases. Overly large and colorful statuesonly compounded the problem. With theBlessed Sacrament reserved in multipletabernacles, the centrality of the Eucharisticliturgy as a unified act of communal worshipbecame less clear. Since clarity ofChurch teaching on the Eucharist and liturgywere key features of the LiturgicalMovement, architecture changed to serveits ends.Liturgical Principles and Church<strong>Architecture</strong><strong>The</strong> Liturgical Movement called <strong>for</strong> clarityin representing the centrality of the Eucharistand the pious participation of themembership of the Mystical Body of Christin the Eucharistic liturgy. At the most basiclevel, architects of the Liturgical Movementwanted to raise the quality of American liturgicallife. By making the liturgical regulationsof the <strong>Sacred</strong> Congregation of Ritesmore widely known, they hoped to bringabout consistent practice in order to increasethe reverence <strong>for</strong> the Mass and otherdevotions. <strong>The</strong>ir concerns were not merelylegalistic, however. Intimately connectedwith these goals was the desire to increasethe active and pious participation of the laity,and architectural changes followed almostimmediately to serve that end.Maurice Lavanoux lamented in a 1929article in Orate Fratres that American architectsand liturgists often failed to veil thetabernacle, ordered low quality churchgoods from catalogues, and designedreredoses that enveloped the tabernacleand thereby failed to make it suitablyprominent. 5 Art and historical continuitystill had their place, but now the two primarysymbols, the altar and crucifix,would dominate. Lavanoux asked that artiststreat the altar with proper dignity, notsimply view it as a “vehicle <strong>for</strong> architecturalvirtuosity.” He quoted M.S.MacMahon’s Liturgical Catechism in describingthe new arrangement of the altaraccording to liturgical principles. Insteadof the old Victorian pinnacled altar with itsdisproportionately small tabernacle,MacMahon wrote,the tendency of the modern liturgicalmovement is to concentrate attentionupon the actual altar, to remove the superstructureback from the altar or todispense with it altogether, so that thealtar may stand out from it, with itsdominating feature of the Cross, as theplace of Sacrifice and the table of theLord’s Supper, and that, with its tabernacle,it may stand out as the throneupon which Christ reigns as King andfrom which He dispenses the bounteouslargesse of Divine grace.<strong>The</strong> intention to simplify the altar originatedin a desire to emphasize the activeaspect of Mass and clarify the place of thePrototypical “liturgical altar” from Liturgical Arts magazine, 1931Photo: Liturgical Arts, 1931reserved Eucharist.Advocates of architectural and liturgicalclarity received a new mouthpiece with thepremiere of Liturgical Arts magazine in1931. Its editors wrote that they were “lessconcerned with the stimulation of sumptuousbuilding than…with the fostering ofgood taste, of honest craftsmanship [and]of liturgical correctness.” 6 <strong>The</strong> resistance tomere sumptuous building and the emphasison honesty were means by which the LiturgicalMovement sought to correct the architecturalmistakes of the nineteenth centurywhile maintaining a design philosophyappropriate <strong>for</strong> church architecture.This call <strong>for</strong> honesty and simplicity was tobe extraordinarily influential <strong>for</strong> two reasons:first, it was echoed strongly inSacrosanctum Concilium, and second, with achanged meaning it became the leitmotif ofModernist church architects.Specific architectural changes appearedquickly in new construction and renovations.Altars with tall backdrops were replacedby those with a solid, simple rectangularshape and prominent tabernacles.Edwin Ryan included instructions on thedesign of the appropriate altar in the inauguralissue of Liturgical Arts. 7 He asked <strong>for</strong>“liturgical correctness” and included animage of two prototypical altars fulfillingliturgical principles. <strong>The</strong> rectangular slabof the altar remained dominant, and thetabernacle stood freely. Its rounded shapefacilitated the use of the required tabernacleveil. <strong>The</strong> crucifix remained dominantand read prominently against a plain backdrop.<strong>The</strong> tester or baldachino emphasizedthe altar and marked its status. Ryan madeit clear that these suggestions were notmeant to limit the creativity of the architectand that “within the requirements of liturgicalcorrectness and good taste the fullestliberty is of course permissible.” A builtexample from the firm of Comes, Perry andMcMullen gave the high altar of St. Luke’sChurch in St. Paul, MN a figural backdrop.<strong>The</strong> sculpture group stood behind the altarand not on it, was dominated by the crucifix,and contrasted in color with the largetabernacle. Clarification of the place of thealtar and the tabernacle did not necessarilymean a bare sanctuary and absence of ornamentaltreatment.Another influential journal, ChurchProperty Administration, provided in<strong>for</strong>mationon the liturgical movement and its architecturaleffects. With a circulation ofnearly 15,000 in 1951 that included 128bishops, 11,007 churches and 802 architects,the magazine reached a popular audiencebut included numerous articles on architecturewhich evidenced the ideals of the LiturgicalMovement. Michael Chapmanpenned a piece called “Liturgical Movementin America” in 1943 that spoke of liturgicallaw, tabernacle veils and rubrics,but his underlying thrust grew out of thecontext of the liturgical movement. <strong>The</strong>14 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>

High altar, St. Luke’s Church, St. Paul, Minnesotachanges at the altar, he claimed, weremeant to “direct the attention of our peopleto the inner significance of the Action per<strong>for</strong>medat it.” <strong>The</strong> simplification of the altarand sanctuary was intended to help thealtar resume “its functional significance asthe place of Sacrifice; its very austerityserving to focus the mind and soul uponHim who is there enshrined, rather than onthe shrine itself.” 8 Chapman also critiquednineteenth century architects <strong>for</strong> reducingtabernacles to mere cupboards and reiteratedthat liturgical law <strong>for</strong>bade the nonethelesscommon practice of putting a statueor monstrance atop a tabernacle.<strong>The</strong> common abuse of using tabernaclesas stands <strong>for</strong> statues and altar crucifixes becameone of the immediate issues to resolve.This small but significant problemtied directly to the Liturgical Movement’saim to clarify the place of the Eucharist inthe life of the Church. Maurice Lavanouxlamented with “a sense of shame” that hehad once designed an extra-shallow tabernacle“so that the back could be filled withbrick as an adequate support” <strong>for</strong> a statue. 9Altar, tabernacle and statues were meant tobe brought into a harmonious wholethrough placement, treatment, and number.<strong>The</strong> various parts would amplify thetrue hierarchy of importance without diminishingthe rightful place of any individualcomponent of Christian worship orpiety. One author in Church Property Administrationtitled his article “Eliminate Distractionsin Church Interiors,” and suggestedthat all things which “distract attentivenessand reduce the powerof concentration” be removedor improved. 10 As H.A.Reinhold, one of the pioneers ofthe liturgical movement, put it,liturgical churches would “putfirst things first again, secondthings in the second place andperipheral things on the periphery.”11In the years leading up to theSecond Vatican Council, muchdiscussion continued concerningthe appropriate churchbuilding and the kind of designit required. <strong>The</strong> great majorityof architects and faithful held totheir traditions without fear ofappropriate updating. Whilecertain Modernist architectsbuilt high profile churchprojects, such as Le Corbusier’sNotre Dame du Haut (1950-54)and Marcel Breuer’s St. John’sAbbey in Minnesota (1961),most church architects avoidedthis type of modernism. Evenin 1948 when Reinhold suggestedthe possibility of semicircularnaves, priests facing thepeople, chairs instead of pews,and organs near the altar andnot in a loft, he would preserve his moretraditional sense of architectural propriety.Be<strong>for</strong>e the Council, a middle road of architecturalre<strong>for</strong>m emerged, one that sharedideas with the Liturgical Movement andMediator Dei. 12Photo: Cram, American Church Building of Today, 1929<strong>The</strong> Spirit of Mediator DeiIn his 1947 encyclical Mediator Dei, PiusXII praised the new focus on liturgy. Hetraced the renewed interest to severalBenedictine monasteries and thought itA R T I C L E Swould greatly benefit the faithful who<strong>for</strong>med a “compact body with Christ <strong>for</strong> itshead” (§5). However, one of the introductoryparagraphs explained that the encyclicalwould not only educate those resistantto appropriate change, but also addressoverly exuberant liturgists. Pius wrote:We observe with considerable anxietyand some misgiving, that elsewhere certainenthusiasts, over-eager in theirsearch <strong>for</strong> novelty, are straying beyondthe path of sound doctrine and prudence.Not seldom, in fact, theyinterlaid their plans and hopes <strong>for</strong> a revivalof the sacred liturgy with principleswhich compromise this holiest ofcauses in theory or practice, and sometimeseven taint it with errors touchingCatholic faith and ascetical doctrine(§8).Pius was concerned with abuses of liturgicalcreativity, a blurring of the lines betweenclerics and lay people regarding thenature of the priesthood, and the use of thevernacular without permission. In mattersmore closely related to art and architecture,he warned against the return of the primitivetable <strong>for</strong>m of the altar, against <strong>for</strong>biddingimages of saints, and against crucifixeswhich showed no evidence of Christ’spassion (§62). Mediator Dei offered strongrecommendations <strong>for</strong> sacred art as well, allowing“modern art” to “be given freescope” only if it were able to “preserve acorrect balance between styles tending neithertoward extreme realism nor to excessive‘symbolism’…”(§195). He deploredand condemned “those works of art, recentlyintroduced by some, which seem tobe a distortion and perversion of true artand which at times openly shock Christiantaste, modesty and devotion…” (§195). JesuitFather John La Farge, chaplain of theLiturgical Arts Society, lost no time in tak-Blessed Sacrament Church and Rectory, Sioux City, Iowa, 1958<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 15Photo: Church Property Administration, March-April 1958

A R T I C L E SInterior of Blessed Sacrament Church, Sioux City, Iowaing the words of Pius XII to the readers ofLiturgical Arts in 1948, even be<strong>for</strong>e the officialEnglish language translation was available.13By the 1950s, the use of contemporarydesign methods had begun to merge withthe liturgical movement and provided anew set of buildings which have receivedlittle notice in the liturgical and art historicaljournals. With a few notable exceptions,most architects worked within the requestsof Mediator Dei while adapting newmaterials and artistic methodologies tochurch design. Despite some argumentsagainst a supposed “false” and “dishonest”use of historical styles like Gothic, architectscontinued to either build overtly traditionalchurches or use new idioms whichmaintained a logical continuity with thosethat came be<strong>for</strong>e. Architects like EdwardSchulte and others who echoed Pius XII’scall <strong>for</strong> moderation in liturgical innovationfound few allies in the architectural media.Without much fanfare, they simply continuedto design church buildings that servedthe needs of the day.Schulte, a Cincinnati architect and onetimepresident of the American <strong>Institute</strong> ofArchitects, took an approach to church designthat truly grew organically from thatwhich came be<strong>for</strong>e. His Blessed SacramentChurch in Sioux City, Iowa appeared inChurch Property Administration in 1958 andprovided a dignified and substantial answerto the problem presented by the architecturalModernists: how to make a modernchurch which espousednew ideas in liturgicaldesign. 14 <strong>The</strong> generousopenings of the westfacade and the single imageof “Our Lord in theBlessed Sacrament” embodiednoble simplicity asexpressed by the LiturgicalMovement withoutsacrificing content or resortingto an industrialaesthetic. <strong>The</strong> interiorpresented a large sanctuarywith a prominent tabernacle,a dominant crucifix,all of it at once appropriatelyornamental andwithout distractions. <strong>The</strong>limestone piers supportedvisible truss arches whichfulfilled much of themovement’s demand <strong>for</strong>“honesty” in construction.<strong>The</strong> adoring angelspainted on the ceiling appropriatelyenriched thechurch in a style whichcopied no past age.Schulte satisfied the demandto focus attentionon the high altar by placinghis one side altar outsidethe south arcade. Most strikingly, heplaced the choir behind the high altar, satisfyingthe requests of those such asReinhold and others to restore what manyliturgical scholars believed to be an ancientPhoto: Church Property Administration, March-April 1958Holy Trinity Church, Gary, Indiana, 1959arrangement.Another novel yet historically continuousapproach to the Liturgical Movementproduced the Church of the Holy Trinity inGary, Indiana. Published in 1959, it used astyle called “modern classic” but partookof the ideas generated by the LiturgicalMovement. Architect J. Ellsworth Pottergave the exterior a campanile, porticoedentrance, and a dignified ecclesiastical airgrowing from continuity of conventionalecclesiastical typology. <strong>The</strong> plan proved adeparture, however, turning the nave 90degrees and putting the sanctuary againstthe long end. This arrangement gave all ofthe congregation direct sight lines to thesanctuary’s prominent tabernacle and<strong>for</strong>ceful imagery. By providing seating <strong>for</strong>432 with only 12 rows of pews, the churchbrought “the congregation of Holy Trinitycloser to the main altar.” 15 Fulfilling the LiturgicalMovement’s requests <strong>for</strong> an increasedprominence <strong>for</strong> Baptism, the baptisterywas a substantial chapel-like room.Instead of competing with the high altar,another special shrine was pulled out fromthe main nave and given its own smallchapel. <strong>The</strong> desires of the Liturgical Movementwere incorporated within a churchwhich otherwise maintained a recognizablearchitectural continuity with olderchurches. It grew organically from thosethat came be<strong>for</strong>e.In one other example, an article entitled“Dignified Contemporary Church <strong>Architecture</strong>”appeared in Church Property Administrationin 1956 and presented theChurch of St. <strong>The</strong>rese in Garfield Heights,16 Fall 2000 <strong>Sacred</strong> <strong>Architecture</strong>Photo: Church Property Administration, July-August 1959

A R T I C L E SOhio. 16 Designed by Robert T. Miller ofCleveland, the building used a palette recallinghis early days as a designer of industrialbuildings but nonetheless maintaineda sense of Catholic purpose. <strong>The</strong>very large church seated 1,000 people, usingmaterials of steel, concrete block, andbrick. Despite the incorporation of industrialbuilding methods, the architect wascontent to let the “modern” materials be ameans rather than an end. <strong>The</strong> tall campanileproved visible <strong>for</strong> miles and the westfront of the building offered a grand entry.A well-proportioned Carrara marble statueof St. <strong>The</strong>rese in a field of blue mosaic withgold crosses and roses was surrounded byan ornamental screen inset with <strong>The</strong>resiansymbolism. A dramatic three-story facetedglass window with abstracted figural imagerygave the baptistery a grandeur it deserved.<strong>The</strong> sanctuary received dramaticnatural lighting over the high altar and itsprominent tabernacle. Images of Josephand the Virgin <strong>for</strong>m part of the scene, butwithout altars of their own. <strong>The</strong> symbolismin the aluminum baldachino joinedwith the precious materials of the altar toestablish its proper status. <strong>The</strong> altar carriedthe simple but essential message“Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus.” Modern materialscame together with a decorous arrangementof parts to <strong>for</strong>m a dignified contemporarychurch.<strong>The</strong>se churches were built in the spiritof Mediator Dei. <strong>The</strong>y eschewed the claimsof some <strong>for</strong> unusual shapes, banishment o<strong>for</strong>nament, and the use of exposed industrialmaterials. Despite the prevailing notionthat the post-war United States sawnothing but modernist architecture, in 1954three “traditional” churches were beingbuilt <strong>for</strong> every one “modern” church. 17Ironically, Modernist architect-heroes disproportionatelyfound their way into thesecular press, impressed other architectsand persuaded building committees. Nomatter how clearly the traditional architectsadopted features of the LiturgicalMovement, they could not compete withthe excitement of the stylistic avant-garde.<strong>The</strong> Modernist critique of traditional architecturereached all levels, from educationalinstitutions to popular culture to chanceryoffices.While leading architectural journalspraised the latest concrete designs, WilliamBusch, a liturgical pioneer and collaboratorwith Virgil Michel in the Liturgical Movement,asked readers to understand the truenature of a church building. In 1955 hepenned an article entitled “Secularism inChurch <strong>Architecture</strong>,” discussing the term“contemporary” and its associations withmodern secular buildings. Secularism inchurch architecture, he feared, would leadto buildings which would “lack the architecturalexpression which is proper to achurch as a House of God and a place of divineworship.” 18 Furthermore, he deniedInterior of St. Mary and St. Louis Priory Chapel, St. Louis, Missouri, by Hellmuth,Obata and Kassabaum. Featured in Liturgical Arts, November, 1962claims of some architectural modernists bywriting:A church edifice is not simply a place<strong>for</strong> the convenient exercise of prayerand instruction and <strong>for</strong> the enactment ofthe liturgy. <strong>The</strong> church edifice itself is apart of the liturgy, a sacred thing, madeholy by a divine presence through solemnconsecration: it is a sacramental object,an outward sign of invisible spiritualreality. 19<strong>The</strong> concept of the church building as a“skin” <strong>for</strong> liturgical action, as would bepresented later in documents like Environmentand Art in Catholic Worship (BCL,1978), was absolutely proscribed. In fact,Busch criticized architect Pietro Belluschi,who would become one of the major <strong>for</strong>cesin American church architecture, <strong>for</strong> seeinga church as “a meeting house <strong>for</strong> people.”He asked instead:Where is the thought of church architectureas addressed to God? And where isthe thought of God’s address to man inhallowing grace? Are we to imaginemodern society as in an attitude of moreor less agnostic and emotional subjectivism,and unconcerned about objectivetruth and the data of divine revelation? 20H.A. Reinhold, a prominent voice of theLiturgical Movement, also urged moderation.He asked that architects neither “canonizenor condemn any of the historicstyles,” rather, “appreciate all of thesestyles of architecture, each <strong>for</strong> its ownvalue.” 21 Although he spoke of “full participationof the congregation” he cautionedagainst centralized altars.Other writers and architects had differentideas, and many church architects whoignored Mediator Dei often received considerablenotoriety. Articles in Liturgical Artsbecame more and more clearly alignedwith a “progressive” notion of liturgical re<strong>for</strong>mat the same time that architecturalmodernism under architects like LeCorbusier and Pietro Belluschi were takinghold. Even be<strong>for</strong>e the arrival of the SecondVatican Council, Liturgical Arts was discussingabstract art <strong>for</strong> churches, presentingimages of blank sanctuaries, and encouragingMass facing the people. 22 Modernistarchitects and liturgists who privilegedwhat Pius XII called “exterior” participationin reaction to the individualismof the previous decades held the majorityopinions and established the normativeprinciples of new church architecture. 23<strong>The</strong> language of the Liturgical Movementfound its way into the documents ofVatican II and remains relatively unchangeddespite the variety of architecturalresponses that claim to grow from it.Phrases such as “noble simplicity” and “activeparticipation” were <strong>for</strong>mative conceptsin pre-Conciliar design which nonethelessallowed <strong>for</strong> a traditional architecture, onesuitably elaborate yet clear in its aims. Incontrast to the conceptions of post-Conciliararchitecture promoted by architecturalinnovators, the 1940s and 1950s providecontextual clues <strong>for</strong> the architecture ofthe Liturgical Movement. It is reasonableto ask whether the writers of SacrosanctumConcilium had the larger history of the liturgicalmovement in mind when they called<strong>for</strong> “noble beauty rather than mere extravagance”(SC, §124).Similarly, in understanding Vatican II’sstatement giving “art of our owndays…free scope in the Church” (SC, §123),it can be remembered that Pius XI (reigned1922-39) had chastised certain modern artists<strong>for</strong> deviating from appropriate art evenPhoto: Liturgical Arts, November, 1962<strong>Sacred</strong><strong>Architecture</strong> Fall 2000 17