CPG for Eating Disorders

CPG for Eating Disorders

CPG for Eating Disorders

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Clinical Practice Guideline<strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN THE NHS.MINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE AND CONSUMER AFFAIRS

CLINICAL PRACTICEGUIDELINE FOREATING DISORDERSCLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN THE NHSMINISTRY OF HEALTHCARE AND CONSUMER AFFAIRS

This clinical practice guideline (<strong>CPG</strong>) is an aid <strong>for</strong> decision-making in health care. It is not in any way an obligedrequirement to adhere to every aspect of this <strong>CPG</strong> and it does not replace the clinical judgement of health careprofessionals.Edition: 1/February/2009Edited by: Catalan Agency <strong>for</strong> Health Technology Assessment and ResearchRoc Boronat, 81-9508005 BarcelonaNIPO: 477-08-022-8ISBN: 978-84-393-8010-8Legal Deposit: B-55481-2008© Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs© Catalan Agency <strong>for</strong> Health Technology Assessment and Research3CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Table of ContentsPresentation 9Authors and Collaborations 11Key Questions 13<strong>CPG</strong> Recommendations 171. Introduction 332. Scope and Objectives 393. Methodology 434. Definition and Classification of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 475. Prevention of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 556. Detection of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 637. Diagnosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 738. Interventions at the Different Levels of Care in the Management of 81<strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>9. Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 9110. Assessment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 17911. Prognosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 19112. Legal Aspects Concerning Individuals with <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> in 195Spain13. Detection, Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies <strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 20114. Dissemination and Implementation 21515. Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Future Research 219ANNEXESAnnex 1. Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation 221Annex 2. Clinical Chapters 223Annex 2.1. Spanish version of the SCOFF survey 223Annex 2.2. Spanish version of the EAT-40 224Annex 2.3. Spanish version of the EAT-26 226Annex 2.4. Spanish version of the ChEAT 227Annex 2.5. Spanish version of the BULIT 228Annex 2.6. Spanish version of the BITE 2345CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Annex 2.7. Diagnostic Criteria <strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 236Annex 2.8. Spanish version of the EDE-12 semistructuredinterview 242Annex 2.9. Incorrect Ideas about Weight and Health 242Annex 2.10. Description of Proposed Indicators 243Annex 3. In<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong> Patients with <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> and theirFamilies247Annex 3.1. Patient In<strong>for</strong>mation 247Annex 3.2. Support Associations <strong>for</strong> Patients with<strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> and their Families 252Annex 4. Glossary 253Annex 5. Abbreviations 261Annex 6. Others 267Annex 6.1. Protocols, Recommendations, TherapeuticOrientations and Guidelines <strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 267Annex 6.2. Results of the Search, Selection and QualityAssessment of Evidence based on the stages per<strong>for</strong>med 269Annex 6.3. Description of the NICE’S <strong>CPG</strong> 270Annex 6.4. Description of the AHRQ’S SRSE 272References 2756CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

PresentationHealth care practice is becoming more and more complex due to multiple factors,the most relevant being the exponential increase of scientific in<strong>for</strong>mation.To ensure that clinical decisions are appropriate, efficient and safe, health careprofessionals must constantly update their knowledge, an objective that entails greatdedication and ef<strong>for</strong>t.In the year 2003, the National Health System’s Interterritorial Council created theHealth Guide (GuíaSalud) project, which aims ultimately to improve evidence-basedclinical decision-making by means of training activities and the configuration of aClinical Practice Guidelines (<strong>CPG</strong>) register in the NHS. Since then, the Health Guideproject has assessed dozens of <strong>CPG</strong>s in accordance with explicit criteria generated by itsscientific committee, registered these <strong>CPG</strong>s and disseminated them throughout theInternet. In early 2006, the Directorate General of the National Health System QualityAgency elaborated the Quality Plan <strong>for</strong> the National Health System, a plan thatencompasses twelve strategies. The objective of this Plan is to increase cohesion of theNHS and aid in guaranteeing maximum quality health care to all citizens, regardless oftheir place of residence. As part of the plan, the development of eight <strong>CPG</strong>s onprevalent pathologies related with health strategies was assigned to different agenciesand experts groups. This guide on eating disorders is the result of this assignment.Additionally, the establishment of a common <strong>CPG</strong> development methodology <strong>for</strong>the NHS was assigned to <strong>CPG</strong> experts groups in our country, resulting in a collectiveef<strong>for</strong>t of consensus and coordination amongst them.In 2007, the Health Guide project was renovated by creating the Clinical PracticeGuideline Library. This project thoroughly covers the elaboration of <strong>CPG</strong>s and includesother services and products of evidence-based medicine. It also aims to favour theimplementation and assessment of the use of <strong>CPG</strong>s in the National Health System.<strong>Eating</strong> disorders, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, as well as other similarclinical pictures, are disorders of multifactorial ethiopathogeny that have been a greatchallenge <strong>for</strong> public health care in the last decades. Sociocultural factors that can lead toeating disorders, as well as the serious physical, social and psychological sequelae thatthese disorders entail have caused great social alarm. <strong>Eating</strong> disorders are diseases thatnot only involve the affected individual, but also the family and closest environment,and even health care and education professionals who are directly or indirectly involved,and who have no access to guides to address these disorders successfully.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS7

This <strong>CPG</strong> aims to provide the population and health care and education professionalswith a useful instrument to address the most basic aspects of the disease, especially thoseconcerning prevention and treatment. Understanding and assessing these diseases,identifying them and assessing their risk potential, as well as presenting therapeuticobjectives, and deciding on the best site <strong>for</strong> treatment and providing help to families, aretasks that can be tackled from different professional settings with an undeniable benefit<strong>for</strong> patients and family members. Such is the role that this evidence-based guide aims toexercise, and which is the result of the work per<strong>for</strong>med by a group of professionalsinvolved in the field of eating disorders and experts on <strong>CPG</strong> methodology.This <strong>CPG</strong> has been revised by Spanish eating disorders experts and is endorsed bySpanish patient associations and scientific societies involved in the management of thesepatients.Pablo RiveroGeneral DirectorQuality Agency of the National Health SystemCLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS8

Authorship and Collaborations<strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> <strong>CPG</strong> Working GroupFrancisco J. Arrufat, psychiatrist, Consorci Hospitalari de Vic Hospital (Barcelona)Georgina Badia, psychologist, Hospital de Santa Maria (Lérida)Dolors Benítez, research support technician, CAHTA (Barcelona)Lidia Cuesta, psychiatrist, Hospital Mútua de Terrassa (Barcelona)Lourdes Duño, psychiatrist, Hospital del Mar (Barcelona)Maria-Dolors Estrada, preventive physician and Public Health, CAHTA (Barcelona)CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP)Fernando Fernández, clinical psychologist, Hospital of Bellvitge,Hospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona)Joan Franch, psychiatrist, Institut Pere Mata, Reus (Tarragona)Cristina Lombardia, psychiatrist, Parc Hospitalari Martí Julià,Health Care Institute, Salt (Gerona)Santiago Peruzzi, psychiatrist, Sant Joan de Déu Hospital,Esplugues de Llobregat (Barcelona)Josefa Puig, nurse, Hospital Clínic i Provincial de Barcelona (Barcelona)Maria Graciela Rodríguez, clinical and biochemical analyst, CAHTA (Barcelona)Jaume Serra, physician, nutritionist and dietician, Department of Health ofCatalonia(Barcelona)José Antonio Soriano, psychiatrist, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona)Gloria Trafach, clinical psychologist, Inastitut d’Assistència Sanitària, Salt (Gerona)Vicente Turón, psychiatrist, Department of Health of Catalonia (Barcelona)Marta Voltas, attorney, Fundación Imagen y Autoestima (Barcelona)CoordinationTechnical CoordinatorMaria-Dolors Estrada, preventive physician and Public Health, CAHTA (Barcelona)CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP)Clinical CoordinatorVicente Turón, psychiatrist, Departament of Health of Catalonia (Barcelona)CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS9

External Review of Patient In<strong>for</strong>mationAssociation in Defense of Anorexia Nerviosa and Bulimia Management (ADANER)Spanish Federation of Support Associations <strong>for</strong> Anorexia y Bulimia(FEACAB)Collaborating societies, associations or federationsThis <strong>CPG</strong> is endorsed by the following organizations:Luis Beato, Spanish Association <strong>for</strong> the Study of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (AEETCA)AEETCA is the only scientific society specifically dedicated to eating disordersRosa Calvo, General Council of the Spanish PsychologistAssociationJavier García Campayo, Spanish Society of PsychosomaticsLourdes Carrillo, Spanish Society of Family and CommunityMedicine (SemFYC) (Barcelona)Dolors Colom, General Council of Social WorkersMaría Diéguez, Spanish Neuropsychiatry AssociationAlberto Fernández de Sanmamed, General Council of Spanish Social Educator AssociationsCarlos Iglesias, Spanish Society of Dietetics and Food SciencesPilar Matía, Spanish Society of Endocrinology and NutritionAlberto Miján, Spanish Society of Internal MedicineJosé Manuel Moreno, Spanish Pediatrics AssociationRosa Morros, Spanish Society of Clinical PharmacologyVicente Oros, Spanish Society of Primary Care PhysiciansNúria Parera, Spanish Society of Gynaecology and ObstetricsBelén Sanz-Aránguez, Spanish Society of Psychiatry and Spanish Society ofBiological PsychiatryIngrid Thelen, National Association of Mental Health NursingM. Alfonso Villa, Spanish Odontologist and Stomatologist AssociationDeclaration of Interests:All members of the working group, as well as the individuals who have collaborated in thedevelopment of this guide (experts on eating disorders, representatives from differentassociations, scientific societies, federations and external reviewers), have carried out thedeclaration of conflict of interests by completing a <strong>for</strong>m designed to this end.None of the participants have declared having a conflict of interest related with eatingdisorders.This guide is editorially independent from the funding organisation.11CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Key QuestionsDefinition and Classification of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>1. How are eating disorders defined and classified? What are the shared and specific clinicalfeatures of each type?2. Ethiopathogeny of eating disorders: What are the main risk factors?3. What are the most frequent co morbidities of eating disorders?Prevention of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>4. What is the efficacy of primary care interventions in avoiding eating disorders? Are there anynegative effects?Detection of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>5. What screening instruments are useful to identify cases of eating disorders?Diagnosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>6. What clinical criteria are useful to diagnose eating disorders?7. How are eating disorders diagnosed?8. What is the differential diagnosis of eating disorders?Interventions at the Different Levels of Care in the Management of <strong>Eating</strong><strong>Disorders</strong>9. What are the primary care (PC) and specialised care interventions <strong>for</strong> eating disorders?Other resources?10. In eating disorders, what clinical criteria may be useful to assess referral amongst the healthcare resources available in the NHS?11. In eating disorders, what clinical criteria may be useful to assess inpatient care (completehospitalisation) in the healthcare resources available in the NHS?12. In eating disorders, what clinical criteria may be useful to assess discharge in the healthcareresources available in the NHS?Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>13. What is the efficacy and safety of re-nutrition in patients with eating disorders?12CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

14. What is the efficacy and safety of nutritional counselling in patients with eating disorders?15. What is the efficacy and safety of cognitive-behavioural therapy in patients with eatingdisorders?16. What is the efficacy and safety of self-help and guided self-help in patients with eatingdisorders?17. What is the efficacy and safety of interpersonal therapy in patients with eating disorders?18. What is the efficacy and safety of family therapy (systemic or not) in patients with eatingdisorders?19. What is the efficacy and safety of psychodynamic therapy in patients with eating disorders?20. What is the efficacy and safety of behavioural therapy in patients with eating disorders?21. What is the efficacy and safety of antidepressants in patients with eating disorders?22. What is the efficacy and safety of antipsychotic drugs in patients with eating disorders?23. What is the efficacy and safety of appetite stimulants in patients with anorexia nervosa(AN)?24. What is the efficacy and safety of opioid antagonists in patients with eating disorders?25. What is the efficacy and safety of other psychoactive drugs in patients with eatingdisorders?26. What is the efficacy and safety of combined interventions in patients with eating disorders?27. What is the treatment <strong>for</strong> eating disorders that occur with comorbidities?28. How are chronic cases of eating disorders treated?29. What is the treatment <strong>for</strong> eating disorders in special situations such as pregnancy and delivery?Assessment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>30. What tools are useful to assess the symptoms and behaviour of eating disorders?31. What tools are useful <strong>for</strong> the psychopathological assessment of eating disorders?Prognosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>32. What is the prognosis of eating disorders?13CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

33. Are there prognostic factors <strong>for</strong> eating disorders?Legal Aspects Concerning Patients with <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> in Spain34. What legal procedure must be followed when a patient with an eating disorder refuses toreceive treatment?35. Is the in<strong>for</strong>med consent of a minor with an eating disorder legally valid?36. In the case of a minor with an eating disorder, what is the legal solution to the dilemmastemming from the responsibility of confidentiality, respect of autonomy and obligationstowards the minor’s parents or legal guardians?CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS14

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS15

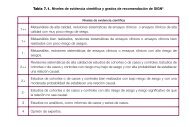

<strong>CPG</strong> RecommendationsIn this section recommendations are presented following the guide’s structure. Chapters 1,2 and3 of the <strong>CPG</strong> include an introduction, scope and objectives, and methodology, respectively.Chapter 4 covers eating disorders and Chapter 11 addresses prognosis. All these chapters aredescriptive and thus no recommendations have been <strong>for</strong>mulated <strong>for</strong> clinical practice. Chapter 5,which covers prevention, is the first to provide recommendations. This section’s abbreviationscan be found at the end.Grade of recommendation: A, B, C o D, depending on whether evidence quality is very high,high, moderate or low. Good clinical practice: recommendation based on the working group’s consensuses.(Please refer to Annex 1).5. Primary Prevention of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Question 5.1.) 5.1. Sample, <strong>for</strong>mat and design characteristics of eating disorder preventionprogrammes that have shown greater efficacy should be considered themodel <strong>for</strong> future programmes. 5.2. In the design of universal eating disorder prevention strategies, it must betaken into account that expected behavioural changes in children andadolescents without these types of problems might differ from those ofhigh-risk populations. 5.3. Messages on measures that indirectly protect individuals from eatingdisorders should be passed on to the family and adolescent: following ahealthy diet and eating at least one meal at home with the family,facilitating communication and improving self-esteem, avoiding familyconversations from compulsively turning to eating and image andavoiding jokes and disapproval regarding the body, weight or eatingmanner of children and adolescents.6. Detection of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Question 6.1.)D 6.1. Target groups <strong>for</strong> screening should include young people with low bodymass index (BMI) compared to age-based reference values, patientsconsulting with weight concerns without being overweight or people whoare overweight, women with menstrual disorders or amenorrhoea, patientswith gastrointestinal symptoms, patients with signs of starvation orrepeated vomiting, and children with delayed or stunted growth, children,adolescents and young adults who per<strong>for</strong>m sports that entail a risk ofdeveloping an eating disorder (athletics, dance, synchronised swimming,etc.).CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS16

D 6.2. In anorexia nervosa (AN), weight and BMI are not considered the onlyindicators of physical risk.D 6.3. Early detection and intervention in individuals presenting weight loss areimportant to prevent severe emaciation.D 6.4. In the case of suspected AN, attention should be paid to overall clinicalassessment (repeated over time), including rate of weight loss, growthcurve in children, objective physical signs and appropriate laboratorytests. 6.5. It is recommended to use questionnaires adapted and validated in theSpanish population <strong>for</strong> the detection of eating disorder cases (screening).The use of the following tools is recommended:<strong>Eating</strong> disorders in general: SCOFF (<strong>for</strong> individuals aged 11 years andover)AN: EAT-40, EAT-26 and ChEAT (the latter <strong>for</strong> individuals aged between8 and 12 years)Bulimia nervosa (BN): BULIT, BULIT-R and BITE (the three <strong>for</strong>individuals aged 12-13 years and over) 6.6. Adequate training of PC physicians is considered essential <strong>for</strong> earlydetection and diagnosis of eating disorders to ensure prompt treatment orreferral, when deemed necessary. 6.7. Due to the low frequency of visits during childhood and adolescence, it isrecommended to take advantage of any opportunity to providecomprehensive management and to detect eating disorder risk habits andcases. <strong>Eating</strong> disorder risk behaviour, such as repeated vomiting, can bedetected at dental check-ups. 6.8. When interviewing a patient with a suspected eating disorder, especiallyif the suspected disorder is AN, it is important to take into account thepatient’s lack of awareness of the disease, the tendency to deny thedisorder and the scarce motivation to change, these reactions being morepronounced in earlier stages of the disease. 6.9. It is recommended that different groups of professionals (teachers, schoolpsychologists, chemists, nutritionists and dieticians, social workers, etc.)who may be in contact with at-risk population have adequate training andbe able to act as eating disorder detection agents.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS17

7. Diagnosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Questions 7.1.-7.3.) 7.1. It is recommended to follow the WHO’s (ICD-10) and the APA’s (DSM-IV o DSM-IV-TR) diagnostic criteria.D 7.2.1. Health care professionals should acknowledge that many patients witheating disorders are ambivalent regarding treatment due to the demandsand challenges it entails.D 7.2.2. Patients and, when deemed necessary, carers should be provided within<strong>for</strong>mation and education regarding the nature, course and treatment ofeating disorders.D 7.2.3. Families and carers may be in<strong>for</strong>med of existing eating disorderassociations and support groups. 7.2.4. It is recommended that the diagnosis of eating disorders includeanamnesis, physical and psychopathological examinations andcomplementary explorations. 7.2.5. Diagnostic confirmation and therapeutic implications should be in thehands of psychiatrists and clinical psychologists.8. Interventions at the Different Levels of Care (Questions 8.1.-8.4.)D 8.1. Individuals with eating disorders should be treated in the appropriate carelevel based on clinical criteria: outpatient care, day care (day hospital) andinpatient care (general or psychiatric hospital).D 8.2. Health care professionals without specialist experience in eatingdisorders or who are faced with uncertain situations should seek theadvice of a trained specialist when emergency inpatient care is deemedthe most appropriate option <strong>for</strong> a patient with an eating disorder.D 8.3. The majority of patients with BN can be treated on an outpatient basis.Inpatient care is indicated when there is risk of suicide, self-inflictedinjuries and serious physical complications.D 8.4. Health care professionals should assess patients with eating disorders andosteoporosis and advise them to refrain from per<strong>for</strong>ming physicalactivities that may significantly increase the risk of fracture.D 8.5. The paediatrician and the family physician must be in charge of themanagement of eating disorders in children and adolescents. Growth anddevelopment must be closely monitored.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS18

D 8.6. Primary care centres should offer monitoring and management ofphysical complications to patients with chronic AN and repeatedtherapeutic failures who do not wish to be treated by mental healthservices.D 8.7. Family members, especially siblings, should be included in theindividualized treatment plan (ITP) of children and adolescents witheating disorders. The most common interventions involve sharing ofin<strong>for</strong>mation, advice on behavioural management of eating disorders andimproving communication skills. The patient’s motivation to changeshould be promoted by means of family intervention.D 8.8. Where inpatient care is required, it should be carried out within areasonable distance to the patient’s home to enable the involvement ofrelatives and carers in treatment, to enable the patient to maintain socialand occupational links and to prevent difficulties between care levels.This is particularly important in the treatment of children and adolescentsD 8.9. Patients with AN whose disorder has not improved with outpatienttreatment must be referred to day patient treatment or inpatient treatment.For those who present a high risk of suicide or serious self-inflictedinjuries, inpatient management is indicated.D 8.10. Inpatient treatment should be considered <strong>for</strong> patients with AN whosedisorder is associated with high or moderate risk due to common disease orphysical complications of AN.D 8.11. Patients with AN who require inpatient treatment should be admitted to acentre that ensures adequate re-nutrition, avoiding the re-feedingsyndrome, with close physical monitoring (especially in the first fewdays), along with the appropriate psychological intervention.D 8.12. The family physician and paediatrician should take charge of theassessment and initial intervention of patients with eating disorders whoattend primary care.D 8.13. When management is shared between primary and specialised care, thereshould be close collaboration between health care professionals, patientsand relatives and carers. 8.14. Patients with confirmed diagnosis or clear suspicion of an eating disorderwill be referred to different health care resources based on clinical andage criteria.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS19

8.15. Referral to adult or children mental health centres (CSMA/CSMIJ) by thefamily physician or paediatrician should consist of integrated care withshared responsibilities. 8.16. Cases referred to adult or children mental health centres (CSMA/CSMIJ)still require different levels to work together and short- and mid-termmonitoring of patients, to avoid complications, recurrences and the onsetof emotional disorders, and to detect changes in the patient’senvironment that could influence the disease. 8.17. The need to prescribe oestrogen treatment to prevent osteoporosis in girlsand adolescents with AN should be carefully assessed, given that thismedication can hide the presence of amenorrhoea. 8.18. In childhood, specific eating disorder treatment programmes designed <strong>for</strong>these ages will be required.9. Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Questions 9.1.-9.20.)Medical Measures (Re-nutrition and Nutritional Counselling)Re-nutrition (Question 9.1.)Anorexia nervosaD 9.1.1.1. A physical exploration and in some cases oral multivitamin and/ormineral supplements are recommended, both in outpatient and inpatientcare, <strong>for</strong> patients with AN who are in the stage of body weightrestoration.D 9.1.1.2. Total parenteral nutrition should not be used in patients with AN unlessthe patient refuses nasogastric feeding and/or when there isgastrointestinal dysfunction. 9.1.1.3. Enteral or parenteral re-nutrition must be applied using strict medicalcriteria and its duration will depend on when the patient is able to resumeoral feeding.General Recommendations on Medical Measures (GM) <strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>(Questions 9.1.-9.2.)<strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> 9.GM.01. Nutritional support <strong>for</strong> patients with eating disorders will be selectedbased on the patient’s degree of malnutrition and collaboration, andalways with the psychiatrist’s approval.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS20

9.GM.02. Be<strong>for</strong>e initiating artificial nutrition the patient’s degree of collaborationmust be assessed and an attempt must always be made to convincehim/her of the benefits of natural feeding. 9.GM.03. In day hospitals, nutritional support <strong>for</strong> low-weight patients, where anoral diet is insufficient, can be supplemented with artificial nutrition (oralenteral nutrition). To ensure its intake, it must be administered during theday hospital’s hours, providing supplementary energy ranging from 300to 1,000 kcal/day. 9.GM.04. Oral nutritional support in eating disorder inpatients is deemed adequate(favourable progress) when a ponderal gain greater than 0.5 kg per weekis produced, with up to 1 kg increments being the usual during thatperiod. Sometimes, when the patient with moderate malnutrition resistsresuming normal feeding, the diet can be reduced by 500-700 kcal and besupplemented by complementary oral enteral nutrition in the sameamount, which must be administered after meals and not instead ofmeals. 9.GM.05. In the case of severe malnutrition, extreme starvation, poor progress orlack of cooperation of the patient in terms of eating, artificial nutritiontreatment is indicated. If possible, an oral diet with or without oralenteral nutrition is always the first step, followed by a 3 to 6 day periodto assess the degree of collaboration and medical-nutritional evolution. 9.GM.06. Regarding estimated energetic requirements, it is recommended thatcaloric needs at the beginning always be below the usual, that realweight, as opposed to ideal weight, is used to make the estimation andthat in cases of severe malnutrition energetic requirements be 25 to 30kcal/kg real weight or total kcal not higher than 1,000/day.Anorexia nervosaD 9.GM.1. In feeding guidelines <strong>for</strong> children and adolescents with anorexiaNervosa, carers should be included in any dietary in<strong>for</strong>mation, educationand meal planning.D 9.GM.2. Feeding against the will of the patient should be used as a last resort inthe management of AN.D 9.GM.3. Feeding against the will of the patient is an intervention that must beper<strong>for</strong>med by experts in the management of eating disorders and relatedclinical complications.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS21

D 9.GM.4. Legal requirements must be taken into account and complied with whendeciding whether to feed a patient against his/her will.D 9.GM.5. Health care professionals must be careful with the healthy weightrestoration process in children and adolescents with AN, administeringthe nutrients and energy required by providing an adequate diet in orderto promote normal growth and development.Bulimia nervosaD 9.GM.6. Patients with BN who frequently vomit and abuse laxatives can developabnormalities in electrolyte balance.D 9.GM.7. When electrolyte imbalance is detected, in most cases elimination of thebehaviour that caused it is sufficient to correct the problem. In a smallnumber of cases, oral administration of electrolytes whose plasmaticlevels are insufficient is necessary to restore normal levels, except incases involving gastrointestinal absorption.D 9.GM.8. In the case of laxative misuse, patients with BN must be advised on howto decrease and stop abuse. This process must be carried out gradually.Patients must also be in<strong>for</strong>med that the use of laxatives does not decreasenutrient absorption.D 9.GM.9. Patients who vomit habitually must have regular dental check-ups and beprovided with dental hygiene advice.Psychological Therapies <strong>for</strong> <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>Cognitive-Behavioural therapy (Question 9.3.)Bulimia nervosaA9.3.2.1.1. CBT-BN is a specifically adapted <strong>for</strong>m of CBT and it is recommended that16 to 20 sessions are per<strong>for</strong>med over 4 or 5 months of treatment.B 9.3.2.1.2Patients with BN who do not respond to or refuse to receive CBTtreatment may be offered alternative psychological treatment.D9.3.2.1.3.Adolescents with BN can be treated with CBT adapted to their age, levelof development, and, if appropriate, the family’s intervention can beincorporated.22CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderA 9.3.3.1. A specifically adapted <strong>for</strong>m of CBT can be offered to adults with bingeeatingdisorder (BED).Self-Help (guided or not) (Question 9.4.)Bulimia nervosaB 9.4.1.1.1. A possible first step in BN treatment is initiating a SH programme(guided or not).B 9.4.1.1.2. SH (guided or not) is sufficient only in a small number of patients withBN.Interpersonal Therapy (Question 9.5.)Bulimia nervosaB 9.5.2.1. IPT should be considered an alternative to CBT although patientsshould be in<strong>for</strong>med that it requires 8 to 12 months to achieve resultssimilar to those obtained with CBT.Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderB 9.5.3.1. IPT-BED can be offered to patients with persistent BED.Family Therapy (systemic or not) (Question 9.6)Anorexia nervosaB 9.6.1.1.1. FT is indicated in children and adolescents with AN.D 9.6.1.1.2. Family members of children with AN and siblings and family membersof adolescents with AN can be included in treatment, taking part inimproving communication, supporting behavioural treatment and sharingtherapeutic in<strong>for</strong>mation.D 9.6.1.1.3. Children and adolescents with AN can be offered individualappointments with health care professionals, separate from those inwhich the family is involved.D 9.6.1.1.4. The effects of AN on siblings and other family members justifies theirinvolvement in treatment.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS23

General Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Psychological Therapy (GP) in <strong>Eating</strong><strong>Disorders</strong> (GP) (Questions 9.3.-9.8.)Anorexia nervosaD 9.GP.1. The psychological therapies to be assessed <strong>for</strong> eating disorders are: CBT,SFT, IPT, PDT and BT.D 9.GP.2. In the case of patients who require special care, the selection of thepsychological treatment model that will be offered is even moreimportant.D 9.GP.3. The objective of psychological treatment is to reduce risk, to encourageweight gain by means of a healthy diet, to reduce other symptoms relatedwith eating disorders and to facilitate physical and psychologicalrecovery.D 9.GP.4. Most psychological treatments <strong>for</strong> patients with AN can be per<strong>for</strong>med onan outpatient basis (with physical monitoring) by professionalsspecialised in eating disorders.D 9.GP.5. The duration of psychological treatment should be of at least 6 monthswhen per<strong>for</strong>med on an outpatient basis (with physical monitoring) and 12months <strong>for</strong> inpatients.D 9.GP.6. For patients with AN who have undergone outpatient psychologicaltherapy but have not improved or have deteriorated, the indication ofmore intensive treatments (combined individual and family therapy, dayor inpatient care) must be considered.D 9.GP.7. For inpatients with AN, a treatment programme aimed at suppressingsymptoms and achieving normal weight should be established. Adequatephysical monitoring is important during renutrition.D 9.GP.8. Psychological treatments must be aimed at modifying behaviouralattitudes, attitudes related to weight and body shape and the fear ofgaining weight.D 9.GP.9. The use of excessively rigid behaviour modification programmes is notrecommended <strong>for</strong> inpatients with AN.D 9.GP.10. Following hospital discharge, patients with AN should be offeredoutpatient care that includes monitoring of normal weight restoration andpsychological intervention that focuses on eating behaviour, attitudes toweight and shape and the fear of social response regarding weight gain,along with regular physical and psychological follow-up. Follow-upduration must be of at least 12 months.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS24

D 9.GP.11. In children and adolescents with AN who require inpatient treatment andurgent weight restoration, age-related educational and social needsshould be taken into account.Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderA 9.GP.12. Patients must be in<strong>for</strong>med that all psychological treatments have alimited effect on body weight.B 9.GP.13. A possible first step in the treatment of patients with BED is to encouragethem to follow a SH programme (guided or not).B 9.GP.14. Health care professionals can consider providing BED patients with SHprogrammes (guided or not) that may yield positive results. However,this treatment is only effective in a limited number of patients with BED.D 9.GP.15. If there is a lack of evidence to guide the care of patients with EDNOS orBED, health care professionals are recommended to follow the eatingdisorder treatment that most resembles the eating disorder the patientpresents.D 9.GP.16. When psychological treatments are per<strong>for</strong>med on patients with BED, itmay be necessary in some cases to treat comorbid obesity.D 9.GP.17. Adolescents with BED must be provided with psychological treatmentsadapted to their developmental stage.Pharmacological Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>Antidepressants (Questions 9.9.)Bulimia nervosaB 9.9.2.1.1. Patients should be in<strong>for</strong>med that antidepressant treatment can reduce thefrequency of binge-eating and purging episodes but effects are notimmediate.B 9.9.2.1.2. In the treatment of BN, pharmacological treatments other thanantidepressants are not recommended.D 9.9.2.1.3.D 9.9.2.1.4.The dose of fluoxetine used in patients with BN is greater than the doseused <strong>for</strong> treating depression (60 mg/day).Amongst SSRI antidepressants, fluoxetine is the first-choice drug <strong>for</strong>treatment of BN, in terms of acceptability, tolerability and symptomreduction.25CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderB 9.9.3.1.1. SSRI antidepressant treatment can be offered to a patient with BED,regardless of whether he/she follows a guided SH programme or not.B 9.9.3.1.2. Patients must be in<strong>for</strong>med that SSRI antidepressant treatment can reducethe frequency of binge-eating, but the duration of long-term effects isunknown. Antidepressant treatment may be beneficial <strong>for</strong> a smallnumber of patients.General Recommendations <strong>for</strong> Pharmacological Treatment (GPH) of <strong>Eating</strong><strong>Disorders</strong> (Questions 9.9.-9.15.)Anorexia nervosaD 9.GPH1. Pharmacological treatment is not recommended as the only primarytreatment <strong>for</strong> patients with AN.D 9.GPH.2. Caution should be exercised when prescribing pharmacological treatment<strong>for</strong> patients with AN who have associated comorbidities such asobsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or depression.D 9.GPH.3. Given the risk of heart complications presented by patients with AN,prescription of drugs whose side effects may affect cardiac function mustbe avoided.D 9.GPH.4. If drugs with adverse cardiovascular effects are administered, ECGmonitoring of patients should be carried out.D 9.GPH.5. All patients with AN must be warned of the adverse effects ofpharmacological treatments.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS26

Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderD 9.GPH.6. In the absence of evidence to guide the management of BED, it isrecommended that the clinician treat the patient based on the eatingproblem that most closely resembles the patient’s eating disorderaccording to BN or AN guides.Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> in the Presence of Comorbidities (Question 9.18)<strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> with Organic <strong>Disorders</strong>D 9.18.1. Treatment of clinical and subclinical cases of eating disorders in patientswith diabetes mellitus (DM) is essential given the increased risk in thisgroup.D 9.18.2. Patients with Type 1 DM and an eating disorder must be monitored dueto the high risk of developing retinopathy and other complications.D 9.18.3. Young people with type 1 DM and poor adherence to antidiabetictreatment should be assessed <strong>for</strong> the probable presence of an eatingdisorder.Treatment of Chronic <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Question 9.19.) 9.19.1. The health care professional in charge of the management of chroniceating disorder cases should in<strong>for</strong>m the patient on the possibility ofrecovery and advise him/her to see the specialist regularly regardless ofthe number of years elapsed and previous therapeutic failures. 9.19.2. It is necessary to have access to health care resources that are able toprovide long-term treatments and follow-up on the evolution of chroniceating disorder cases, as well as to have social support to decrease futuredisability.Treatment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> in Special Cases (Question 9.20.)D 9.20.1. Pregnant patients with AN, whether it is the first episode or a relapse,require intensive prenatal care with adequate nutrition and follow-up offoetal development.D 9.20.2. Pregnant women with eating disorders require careful follow-upthroughout pregnancy and the postpartum period.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS27

10. Assessment of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (Questions 10.1.-10.2.)D 10.1.1. Assessment of patients with eating disorders should be comprehensiveand include physical, psychological and social aspects, as well as acomplete assessment of risk to self.D 10.1.2. The therapeutic process modifies the level of risk <strong>for</strong> the mental andphysical health of patients with eating disorders, and thus should bemonitored throughout treatment.D 10.1.3. Throughout treatment, health care professionals who evaluate childrenand adolescents with eating disorders should be alert to possibleindicators of abuse (emotional, physical and sexual) to ensure an earlyresponse to this problem.D 10.1.4. Health care professionals who work with children and adolescents witheating disorders should familiarise themselves with national <strong>CPG</strong>s andcurrent legislation regarding confidentiality. 10.1.5. It is recommended to use questionnaires adapted and validated in theSpanish population in the assessment of eating disorders.At present, the following specific instruments <strong>for</strong> eating disorders arerecommended: EAT, EDI, BULIT, BITE, SCOFF, ACTA and ABOS(the selection of the version should be based on the patient’s age andother application criteria).To assess aspects related with eating disorders, the followingquestionnaires are recommended: BSQ, BIA, BAT, BES and CIMEC(the selection of the version should be based on age and other applicationcriteria). 10.2. The use of questionnaires adapted and validated in the Spanishpopulation is recommended <strong>for</strong> the psychopathological assessment ofeating disorders. At present, the following instruments <strong>for</strong>psychopathological assessment of eating disorders are suggested (versionselection based on patient’s age and other application criteria):Impulsiveness: BIS-11Anxiety: STAI, HARS, CETADepression: BDI, HAM-D, CDIPersonality: MCMI-III, MACI, TCI-R, IPDEObsessiveness: Y-BOCSCLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS28

11. Prognosis of <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong> (chapter without recommendations)12. Legal aspects concerning patients with eating disorders in Spain(questions 12.1.-12.2.)12.1. The use of the legal route is recommended in cases where the professionaldeems appropriate to safeguard the patient’s health, while upholding his/herright to be listened to and properly in<strong>for</strong>med on the process and medical andlegal measures that will be applied. Clearly conveying the procedure is not onlyrespectful to the right to in<strong>for</strong>mation, but can also facilitate the cooperation andmotivation of the patient and his/her environment in the procedure of completehospitalisation (According to current legislation).12.2. One of the characteristic symptoms of eating disorders, and especially of AN, isthe lack of awareness of the disease. The disease itself often entails a lack ofsufficient judgement to provide valid and unmarred consent regarding treatmentacceptance and decision. Hence, if a minor presenting AN and serious healthrisks refuses treatment, the use of appropriate legal and judicial routes shouldbe employed. (According to current legislation).12.3. The necessary balance between different clashing rights requires theprofessional to observe and interpret the best solution in each case. However, itis always important to in<strong>for</strong>m and listen carefully to both parties in order <strong>for</strong>them to understand the relationship between safeguarding health and thephysician’s decision. (According to current legislation).CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS29

Abbreviations, Clinical Questions and Recommendations. (The complete list ofabbreviations can be found in Annex 5)ABOS: Anorectic Behaviour Observation Scale <strong>for</strong> parents/spouseACTA: Attitude Towards Change in <strong>Eating</strong> <strong>Disorders</strong>AN: Anorexia nervosaAPA: American Psychiatric AssociationBAT: Body Attitude TestBED: Binge-<strong>Eating</strong> DisorderBDI or Beck: Beck Depression InventoryBES: Body Esteem ScaleBIA: Body Image AssessmentBIS-11: Barrat Impulsivity ScaleBITE: Bulimic Investigation Test of EdinburghBN: Bulimia nervosaBMI: Body Mass IndexBPD Borderline Personality DisorderBSQ: Body Shape QuestionnaireBT: Behavioural TherapyBULIT: Bulimia testBULIT-R: Revised version of BULITCBT: Cognitive-behavioural therapyCBT-BN: Cognitive-behavioural therapy <strong>for</strong> bulimia nervosaCBT-TA: Cognitive-behavioural therapy <strong>for</strong> binge-eating disorderCDI: Children Depression InventoryCETA: Assessment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescentsChEAT: Children’s <strong>Eating</strong> Attitude TestCIMEC: Questionnaire on Influences on the Aesthetic Body Model (Body ShapQuestionnaire (BSQ)<strong>CPG</strong>: Clinical Practice GuidelineDM: Diabetes mellitusDSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental <strong>Disorders</strong>, fourth edition- revisedtextEAT (EAT-40): <strong>Eating</strong> Attitude TestEAT-26: Short version of EAT-40ECG: ElectrocardiogramCLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS30

ED: <strong>Eating</strong> disorderEDNOS: <strong>Eating</strong> disorder not otherwise specified (non-specific ED)EDI: <strong>Eating</strong> Disorder InventoryFT: Family therapy (non-specific)GPH: General recommendations <strong>for</strong> pharmacological treatmentsGM: General recommendations <strong>for</strong> medical measuresGP: General recommendations <strong>for</strong> psychological therapiesHAM-D: Hamilton Depression ScaleHARS: Hamilton Anxiety ScaleICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th editionIPDE: International Personality Disorder ExaminationIPT: Interpersonal therapyIPT-BED: Interpersonal therapy <strong>for</strong> binge-eating disorderITP: Individualized Treatment PlanKcal.: KilocalorieKg: KilogramMHC: Mental Health CentreMHCFA Mental Health Centre <strong>for</strong> AdultsMGCFCA Mental Health Centre <strong>for</strong> Children and AdolescentsMACI: Millon Adolescent Clinical InventoryMCMI-III: Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory-IIINHS: National Health SystemOCD: Obsessive-Compulsive DisorderPDT: Psychodynamic TherapyPC: Primary careSCOFF: Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food questionnaireSH: Self-helpSSRI: Selective Serotonin Reuptake InhibitorSTAI: State-Trait Anxiety InventoryTCI-R: Temperament and Character Inventory-revisedY-BOCS: Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale31CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS32

1. IntroductionBackgroundThe development of the evidence-based clinical practice guideline elaboration Programme<strong>for</strong> the NHS is being carried out 2ithin the framework of the development of the Quality Plan ofthe Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs (MSC), through the National Health System(NHS)’s Quality Agency.In the initial phase of this Programme (2006), the development of eight <strong>CPG</strong>s has beenprioritised. A collaboration agreement has been established between the ISCIII and healthtechnology assessment agencies and units and the Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre. The HealthSciences Institute of Aragón is in charge of the Programme’s coordination activities.In the bilateral agreement between the CAHTA of Catalonia and the ISCIII it was agreed todevelop a <strong>CPG</strong> <strong>for</strong> eating disorders: anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and atypicalor unspecified eating disorders (EDNOS), based on the best scientific evidence available, whichwould address the most important areas <strong>for</strong> the NHS, in a coordinated manner and with sharedmethodology which would be determined by a group of NHS professionals experienced in <strong>CPG</strong>development. These professionals have comprised the methodological group and the panel ofcollaborators of the <strong>CPG</strong> development programme (1) .JustificationIn the last decades, eating disorders have gained increasing sociosanitary relevance due totheir severity, complexity and difficulty in establishing a diagnosis and specific treatment.<strong>Eating</strong> disorders are pathologies of multifactorial ethiology where genetic, biological,personality, family and sociocultural factors converge, affecting mainly children, adolescentsand young adults.There are is no data available in Spain that analyses the economic burden of eatingdisorder treatments nor studies that assess the cost-effectiveness of different treatments.However, different studies conducted in countries of the European Union 2-7 indicate that directcosts (diagnosis, treatment and monitoring or follow-up) and especially indirect costs (economiclosses derived from the disease that impact the patient and his/her social setting) entail a higheconomic burden and considerably decrease the quality of life of patients with eating disorders.According to a German study that was carried out in 2002, in the case of AN, averagehospitalisation cost is 3.5 times higher than the general hospitalisation average 4 .(1)N= 2,188 AN discharges, recorded during 2003 and 2004 in 156 health areas of 15 autonomous communities.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS33

In 2002, Gowers SG, et al. 8 published the results of a survey conducted in 12 countries thatwere participating in the European project COST Action B6, which aimed to explore consensusand differences in the therapeutic approaches indicated <strong>for</strong> adolescents with AN (severaldifferent Spanish hospitals participated in this project). Results demonstrated significantagreement between the interviewed countries regarding the need to offer a wide array of servicesat the different levels of care. However, considerable differences were detected in terms ofstrategies, especially in hospital admission criteria, use of day centres/day hospitals, etc.In the case of AN 1 , according to the Atlas of Variations in medical practice of the NHS,where the variability in admissions into acute care public or publicly funded 9 hospitals, aredescribed and mapped, a low hospitalisation incidence is observed in AN with, 0.32 admissionsper 10,000 inhabitants and year. Hospitalisation rates <strong>for</strong> AN ranged between 0.08 –practicallynil- and 1.47 admissions per 10,000 inhabitants and year. In terms of the weighted variationcoefficient, the figures confirmed the wide variation among the different health areas in 70% ofAN cases. After consideration of the variation randomised effect, the systematic component ofvariation of the health areas included in the percentiles 5 to 95 shows high variability (SCV 5-95 =0,26). The ample variation found may be related either to demand factors (different morbidity,socio-economic differences of the cities and towns) or to offer factors (practice style, healthcareresources, different policies <strong>for</strong> the development of mental care procedures, etc. The variabilityobserved in hospitalisation rates among Spanish provinces is significant and accounts <strong>for</strong> a 40%of the variability in hospitalisation rates in cases of AN. Upon multilevel analysis, provinciallevel accounts <strong>for</strong> a larger variance proportion than in the region (regional level), rein<strong>for</strong>cing thehypothesis that the different provincial development of psychiatric models and services is behindthe variations found. The remaining studied factors (age, gender, available income, educationallevel, predisposition to hospitalisation) do not appear to exert an influence upon the variabilityobserved in hospitalisation rates in AN, save <strong>for</strong> the recorded unemployment that works in theopposite way: in areas with more recorded unemployment, the probability of hospitalisation islower. No data are available <strong>for</strong> BN or eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS-atypicaleating disorders).Different governmental Spanish and <strong>for</strong>eign institutions have published guides,recommendations and protocols on EDs in the last years, of which the following stand out:• Osona (2008) 10 and the Gerona health region (2006) 11 from the Department of Health-CatalanHealth Service• semFYC (prevention activities and health promotion group) (2007) 12 , (2005) 13 .• American Psychiatric Association (2006) 14 .• Action Manual of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs on the scientific evidenceregarding specialised nutritional support (2006) 15 .• General subdirectorate of Mental Health- Health Service of Murcia (2005) 16 .• Official College and Board of Physicians of Barcelona(2005) 17 .• Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (2004) 18 .• National Health Institute (INSALUD, 2000) 19 , (1995) 20 .CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS34

However, there is a need <strong>for</strong> a guide adapted to the Spanish population using the bestpossible methodology and based on the best available evidence.Recently, other important actions related with eating disorders have been carried out in ourcontext, such as: NAOS and PAOS programme <strong>for</strong> the prevention of obesity in children and ahealthy diet; the Social Pact of the Madrid <strong>for</strong> the prevention of eating disorders; Image andSelf-Esteem Foundation, and pacts between user federations (FEACAB and ADANER) and theMSC.Magnitude of the problemEstimations on the incidence and prevalence of eating disorders vary depending on the studiedpopulation and assessment tools employed. There<strong>for</strong>e, in order to compare data from differentnational and international sources it is essential that the study design be the same. The study in“two phases” is the most appropriate methodology <strong>for</strong> the detection of cases in the community.The first phase consists of screening using self-report symptom questionnaires. In the secondphase, assessment is carried out by means of clinical interviews that are conducted withindividuals who obtained scores above the cut-off point in the screening questionnaire (“at risk”subjects), meaning only a subsample of the total initially screened sample is interviewed.Within the studies that use correct two-phase methodology, very few per<strong>for</strong>m randomsampling of participants who score below the cut-off point of the screening questionnaire tointerviews, which leads to a subestimation of the prevalence of eating disorders by not takingfalse negatives into account 21-23 . An additional problem is the use of different cut-off points inscreening questionnaires.In spite of these methodological difficulties, the increased prevalence of eating disorders issignificant, especially in developed or developing countries, while it is nearly inexistent in thirdworldcountries. Increased prevalence is attributable to increased incidence and duration andchronicity of these clinical pictures.Based on two-phase studies conducted in Spain (Tables 1 and 2) on the highest risk population,women ranging from 12 to 21 years of age, a prevalence of 0.14% to 0.9% is obtained <strong>for</strong> AN,0.41% to 2.9% <strong>for</strong> BN and 2.76% to 5.3% in the case of EDNOS. In total, we would be lookingat an eating disorder prevalence of 4.1% to 6.41%. In the case of male adolescents, even thoughthere are fewer studies available, a prevalence of 0% <strong>for</strong> AN, 0% to 0.36% <strong>for</strong> BN and 0.18% to0.77% <strong>for</strong> EDNOS is obtained, with a total prevalence of 0.27% to 0.90% 21-29 .These numbers are similar to those presented in the NICE <strong>CPG</strong> (2004), where prevalence inof EDNOS, BN and AN in women ranges from 1% to 3.3%, 0.5% to 1.0% and 0.7%,respectively, and also to those in the Systematic Review of Scientific Evidence (SRSE) (2006)which reports prevalence in Western Europe and the United States (0.7% to 3% of EDNOS inthe community, 1% of BN in women and 0.3% of AN in young women).CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS35

Several studies on the incidence of eating disorders that have been published in NorthAmerica and Europe present a 5- to 6-fold increase in incidence between 1960 and 1970. In1998, a review presented by Pawluck, et al. on the general population of the United Statesreported that annual incidence of AN was 19 per 100,000 in women and 2 per 100,000 inmales 30 . In the review presented by Hoek in 2003, incidence was 8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants<strong>for</strong> AN and 12 cases per 100,000 inhabitants <strong>for</strong> BN 32 .In a recent study in the United Kingdom (UK), incidence <strong>for</strong> AN in 2000 was 4.7 per100,000 inhabitants (95% CI: 3.6 to 5.8) and 4.2 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1993 (95% CI: 3.4 to5.0). In Holland, incidence of AN was 7.7 (95% CI: 5.9 to 10.0) per 100,000 inhabitants/yearbetween 1995-1999 and 7.4 between 1985 and 1989 33 . In Navarra, a population survey in 1,07613-year old girls was used to estimate an eating disorder incidence of 4.8% (95% CI: 2.84 to6.82) in a period of 18 months, corresponding to: 0.3% AN (95% CI: 0.16 to 0.48): 0.3% BN(95% CI: 0.15 to 0.49) and 4.2% EDNOS (95% CI: 2.04 to 6.34) 34 .Incidence was greater in women aged 15 to 19 years: they constitute approximately 40%of identified cases in studies both in the US and Europe 30, 31, 33 . There are very few studies thatreport data on AN in prepubertal children or in adults 31 . There are also scarce studies thatpresent incidence data of AN in men. Of all the a<strong>for</strong>ementioned studies, we can conclude thatincidence is lower than 1 per 100,000 inhabitants/year 33 . All these sources establish an eatingdisorder prevalence ratio of 1 to 9 in males versus women.Table 1. Studies on the prevalence of eating disorders in adolescent females in SpainStudy NAge(years)AN(%)BN(%)EDNOS(%)EDs(%)Madrid, 1997 24Morandé G and Casas J.723 15 0.69 1.24 2.76 4.69Zaragoza, 1998 26Ruiz P et al.2,193 12-18 0.14 0.55 3.83 4.52Navarra, 2000 27Pérez-Gaspar M et al.2,862 12-21 0.31 0.77 3.07 4.15Reus, 2008 29Olesti M et al.551 12-21 0.9 2.9 5.3 9.136CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

Table 2. Studies on the prevalence of eating disorders in adolescent males and females in SpainStudyNAge(years)AN(%)BN(%)EDNOS(%)EDs(%)Madrid, 1999 25Morandé G et al.1,314 15 0.00 to 0.69 0.36 to 1.24 0.54 to 2.763.044.700.90Valencia, 2003 21Rojo L et al.544 12-18 0.00 to 0.45 0.00 to 0.41 0.77 to 4.712.915.560.77Ciudad Real, 2005 22Rodríguez-Cano T et al.1,766 12-15 0.00 to 0.17 0.00 to 1.38 0.60 to 4.86Osona (Barcelona), 2006 28Arrufat F2,280 14-16 0.00 to 0.35 0.09 to 0.44 0.18 to 2.70Madrid, 2007 23Peláez MA et al.1,545 12-21 0.00 to 0.33 0.16 to 2.29 0.48 to 2.723.716.410.601.903.490.273.435.340.6437CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS38

2. Scope and ObjectivesTarget PopulationThe <strong>CPG</strong> is focused on patients aged 8 years and older with the following diagnoses: AN,BN and eating disorders not otherwise specified (EDNOS). EDNOS include: binge-eatingdisorder (BED) and non-specific, incomplete or partial <strong>for</strong>ms that do not satisfy all criteria <strong>for</strong>AN, BN and BED.Although binge-eating disorder is the standard name, the truth is that several recurrentbinge-eating episodes must take place to establish this diagnosis (amongst other manifestations).This guide refers to this disorder as binge-eating disorder.The <strong>CPG</strong> also includes treatment of chronic eating disorder patients, refractory totreatment, who can be provided with tertiary prevention of the most serious symptoms andsevere complications.ComorbiditiesThe most frequent comorbidities which may require a different type of care have been includedin the <strong>CPG</strong>:• Mental: substance abuse, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive, personality, mood and impulsecontrol disorders.• Organic: diabetes mellitus, obesity, malabsorbtion syndromes and thyroid diseases.Special situationsThe approach to be employed in special situations such as pregnancy and delivery is alsoincluded.Clinical settingThe <strong>CPG</strong> includes management provided in PC and specialised care. PC services are per<strong>for</strong>medin primary care centres (PCC), the first level of access to health care. Patients with eatingdisorders receive specialised care, the second and third levels of access to health care, by meansof inpatient management resources (psychiatric and general hospital), specialised outpatientconsultations (adult and child/adolescent mental health centres/units, day hospitals <strong>for</strong> day care(partial hospitalisation) (specialised in eating disorders and <strong>for</strong> other general mental healthdisorders), emergency services and medical services of general hospitals. In general hospitalsthere are specific units specialised in eating disorders that include the three care levels. Othertypes of specific units are included: borderline personality disorder and toxicology units.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS39

Aspects includedThe <strong>CPG</strong> includes the following aspects of eating disorders: prevention, detection, diagnosis,interventions at the different levels of care, treatment, assessment, prognosis and legal aspects.InterventionsThe <strong>CPG</strong> includes the following interventions <strong>for</strong> primary prevention of eating disorders:psychoeducational interventions, media literacy, social and political mobilization and activism(advocacy), dissonance-induction techniques, interventions focused on eliminating or reducingthe risk factors of eating disorders or interventions to make the patient stronger (by developingstress coping skills).Some of the outcome variables of primary prevention interventions are: incidence of eatingdisorders, BMI, internalisation of the thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction, anomalous diet, negativeaffects and eating disorders.The <strong>CPG</strong> includes the following treatments:• Medical measures: oral nutritional support, nutritional support with artificial nutrition (enteraloral [nasogastric tube] and parenteral intravenous) and nutritional counselling (NC). NCincludes dietary counselling, nutritional counselling and/or nutritional therapy.• Psychological therapies: cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), self-help (SH), guided self-help(GSH), interpersonal therapy (IPT), family therapy (systemic [SFT] or unspecified [FT]),psychodynamic therapy (PDT) and behavioural therapy (BT).• Pharmacological treatments: antidepressants, antipsychotics, appetite stimulants, opioidantagonists and other psychoactive drugs (topiramate, lithium and atomoxetine).• Combined interventions (psychological and pharmacological or more than one psychologicalintervention).Clinically important treatment outcome variables according to the working group are: BMI,menstruation, pubertal development, reduction/elimination of binge-eating and purging,restoration of a healthy diet, absence of depression and psychosocial and interpersonalfunctioning. The latter two aspects are described in the questions regarding safety ofinterventions.In some cases, recurrence or relapse results are described in the safety section, along withtreatment withdrawls.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS40

Aspects not included in the <strong>CPG</strong>The <strong>CPG</strong> does not include the following diagnoses related with eating disorders <strong>for</strong> severalreasons:• Orthorexia. A poorly defined and insufficiently studied syndromic spectrum that consists ofextreme focus on eating healthy and contaminant-free foods. This disorder can be related toobsessive concerns about health, hypochondriac fears of diseases, and, in a certain way, tocultural attitudes linked to diet and food. Though it is true that people with orthorexia maypresent restrictive anomalies in their diets and ponderal losses, they cannot be consideredatypical or incomplete cases of AN.• Vigorexia (muscle dysmorphia). This disorder is characterized by excessive concern aboutobtaining body perfection by per<strong>for</strong>ming specific exercises. This extreme preoccupationentails significant dissatisfaction with one’s own body image, excessive exercise, special dietsand foods, to the point of generating dependence, as well as substance abuse 35 . At the momentit remains a vaguely defined disorder related with obsessiveness, perfectionism anddysmorphophobia 36-40 .• Night eating syndrome (nocturnal eaters). People with this disorder experience recurrentepisodes of binge-eating during sleep. It is not defined whether these clinical pictures are dueto an eating disorder or to a primary sleep disorder 41-44 .The <strong>CPG</strong> does not include patients under the age of 8 and, thus, diagnoses relating to eatingdisorders most common during those ages, such as swallowing phobia, selective eating andrefusal to eat are not included. However, these disorders are not included either when they areobserved in patients aged 8 and older <strong>for</strong> the following reasons:• Food phobia (simple phobias). In some cases it may be an anxiety-related disorder, while inothers it may be linked to hypochondria (fear of choking, swallowing phobia and death).There<strong>for</strong>e, it does not seem to belong to the spectrum of eating disorders.• Selective eating and refusal to eat. Both are eating disorders but lack the complete andcharacteristic symptomatology associated with AN and BN (cognitive disturbances, distortedbody image, purging behaviours, etc).This does not mean that when deciding on primary prevention policies no interventions shouldbe carried out to address these behaviours, which could indeed be precursors of an eatingdisorder.The <strong>CPG</strong> does not include exclusive interventions <strong>for</strong> comorbid conditions that may occurwith eating disorders.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS41

ObjectivesMain objectiveTo provide health care professionals responsible <strong>for</strong> the management of patients with eatingdisorders with a tool that enables them to make the best decisions to address the problems theircare entails.Secondary objectivesa) To help patients with eating disorders by providing them with useful in<strong>for</strong>mation thatwill aid them in making decisions concerning their disease.b) To in<strong>for</strong>m families and carer on eating disorders and provide them with counselling andadvice so they become actively involved in treatment.c) To implement and develop health care quality indicators that enable the assessment ofthe clinical practice of recommendations presented in this <strong>CPG</strong>.d) To establish recommendations <strong>for</strong> research on eating disorders that enable knowledge togrow.e) To address confidentiality and in<strong>for</strong>med consent issues of patients, especially in the caseof minors under the age of 18, and to include legal procedures in the cases of completehospitalisation (inpatient care) and involuntary treatment.Main usersThis <strong>CPG</strong> is aimed at professionals who are in direct contact with patients with eating disordersor who make decisions regarding the care of these patients (family physicians, paediatricians,psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, dieticians, endocrinologists, pharmacists, gynaecologists,internal medicine physicians, odontologists, occupational therapists and social workers). It isalso aimed at professionals pertaining to other fields who are in direct contact with patients witheating disorders (education, social services, media, justice).The <strong>CPG</strong>’s purpose is to serve as a tool <strong>for</strong> planning the integrated care of patients witheating disorders.The <strong>CPG</strong> provides eating disorder patients with in<strong>for</strong>mation that can also be used by familymembers and friends, as well as by the general population.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS42

3. MethodologyThe methodology employed is described in the MSC’s <strong>CPG</strong> development manual 1 . The stepsfollowed have been:– Creation of the <strong>CPG</strong> working group comprised of a clinical team, a technical team and twocoordinators (clinical and technical). The clinical team consists of a group of health careprofessionals (psychology, psychiatry, nursing and nutrition and dietetics specialists)involved in the study and treatment of eating disorders and an attorney, who are carryingout their activity in Catalonia and are linked to the Master Plan of Mental Health andAddictions of the Catalan Department of Health, and representatives of Spanish scientificsocieties, associations or federations who are involved in the care of eating disorders. Thetechnical team is composed of CAHTA members who have a wealth of experience andknowledge on the development of evidence-based <strong>CPG</strong>s and on critical assessment, andresearch support staff. The working group has relied on the participation of a group ofcollaborating experts from all over Spain selected by the clinical coordinator <strong>for</strong> hisexpertise in the matter, as well as another group of CAHTA members who havecollaborated in some of the following activities: defining the scope, search, documentalmanagement, initial review of literature and internal review. Representatives of thesocieties, associations or federations involved in this project and expert collaborators havetaken part in defining the scope and objectives of the <strong>CPG</strong>, in the <strong>for</strong>mulation of keyclinical questions and in the review of the guide’s rough draft. The participants’declaration of conflict of interests can be found in the section “Authors andCollaborations”.– Formulation of key clinical questions in the following <strong>for</strong>mat: patient / intervention/ comparison / outcome or result (PICO).– The search <strong>for</strong> scientific evidence was structured in different stages:1) Generic databases, meta-search engines and organizations that compile guidelines(National Guidelines Clearinghouse, National Electronic Library <strong>for</strong> Health,Tripdatabase, The Cochrane Library, Pubmed/Medline and BMJ Clinical Evidence)were consulted between 2003 and March 2007.2) To complete the search, a manual search was per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> protocols, recommendations,narrative reviews, therapeutic orientations and guides on eating disorders elaborated byorganisations pertaining to the health care administration, scientific societies, hospitalsand other organizations of our setting. Some of these documents have inspired andserved as a model <strong>for</strong> certain sections of this guide (see Annex 6.1.). This annex alsolists documents created outside of Spain that have been excluded from the selectionprocess due to low quality. However, some have been considered <strong>for</strong> the developmentof certain aspects of this <strong>CPG</strong>.CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS43

3) To respond to those questions unanswered by the <strong>CPG</strong>s, SRSE and assessment reports(AR) included or to update them, a search <strong>for</strong> randomised controlled trials (RCTs) wasper<strong>for</strong>med in Pubmed/Medline between March 2007 and October 2007.4) The search <strong>for</strong> <strong>CPG</strong>/SRSE/AR in Tripdatabase and Pubmed/Medline was also updatedup to October 2007.5) Additional searches were carried out in Pubmed/Medline and Scopus <strong>for</strong> primaryprevention of eating disorders due to the limited in<strong>for</strong>mation available in the documentsincluded (until June 2008). The effect of primary prevention interventions <strong>for</strong> eatingdisorders has been assessed in RCT or in SRSE of RCT.6) A search was also per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> cohort studies and prognosis of eating disorders in theScopus and Psycinfo databases during the period spanning from 2000 to 2008.7) The Ginebrina Foundation was also consulted <strong>for</strong> Medical Training and Research and thedocuments provided by the working group and the references of the documentsincluded were reviewed.– Selection of Evidence. The most relevant documents were selected by applying predefinedinclusion and exclusion criteria:• Inclusion criteria: guides, SRSE and ARs in certain languages (Spanish, Catalan, French,English and Italian) that dealt with the previously mentioned objectives. Minimumquality criteria were established <strong>for</strong> the guides, SRSE and ARs: the bibliographic basesconsulted and/or the <strong>for</strong>mulation process of recommendations (ad hoc defined criteria)had to be described.• Exclusion criteria: documents/guides that were not original, unavailable (wrong referenceor electronic address), not directly related with the proposed objectives, already includedin the bibliography of other documents/guides or that didn’t comply with minimumquality criteria.Two independent reviewers examined the titles and/or summaries of the documents identified bythe search strategy. If any of the inclusion criteria were not fulfilled, the document wasexcluded. If criteria were fulfilled, the complete document was requested and evaluated in orderto decide whether it would be included or not. Discrepancies or doubts that arose during theprocess were resolved by consensus of the entire technical team.– Quality assessment of the scientific evidence. Assessment of <strong>CPG</strong> quality was per<strong>for</strong>med bya trained evaluator using the AGREE 45 instrument. Guides were considered of quality whenthey were classified as Recommended in the overall assessment. For SRSE/ARs and RCT,SIGN’s methodology checklists were applied by an evaluator, following the recommendationsestablished in the MSC’s 1 <strong>CPG</strong> development manual. Classification of evidence has beencarried out using the SIGN system (See Annex 1).CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS44

– Synthesis and analysis of the scientific evidence. Different templates were used <strong>for</strong>in<strong>for</strong>mation retrieval. In<strong>for</strong>mation regarding the main characteristics of the studies wasobtained and then synthesised in evidence tables <strong>for</strong> a subsequent qualitative analysis. Whenthe SRSE or <strong>CPG</strong>s reported the results of individual studies, these results were described in thesection “scientific evidence”.In Annex 6.2 results of the <strong>CPG</strong>’s search, selection and assessment of quality are described. InAnnex 6.3. and Annex 6.4. NICE’s <strong>CPG</strong> 30 and AHRQ’s SRSE 31 are respectively described,representing the main scientific base on which this guide is founded.– Formulation of recommendations based on <strong>for</strong>mal assessment or on SIGN’s consideredjudgement. The grading of recommendations has been per<strong>for</strong>med using SIGN’s system (SeeAnnex 1). Recommendations pertaining to the NICE <strong>CPG</strong> have been considered by theworking group and have been classified as: adopted (and, hence, accepted; they have simplybeen translated into Spanish) or adapted (and, hence, modified: changes have been made withthe purpose of contextualising them to our setting). Controversial recommendations or thoselacking in evidence have been resolved by the working group’s consensus. The category ofeach recommendation appears in the chapters.– Description of psychological therapies. Definitions are derived from the NICE 30 guide, fromthe SRSE where they have been assessed and from the working group itself (See Annex 4).– Description of drugs (mechanism of action and approved indications in Spain) included in the<strong>CPG</strong>. The following websites have been consulted: Spanish Drug Agency (AGEMED)(https://agemed.es) and Vademecum (http://www.vademecum.es). It is recommended to readthe technical chart of each drug be<strong>for</strong>e any therapeutic prescription given that the <strong>CPG</strong> onlyincludes a very brief description of each drug and does not go into depth in terms of schemes,contraindications, etc. (See Annex 4).– Legal aspects. To develop this chapter, aside from reviewing the current legislation in ourcountry, several different articles and reference documents 17, 46-49 have been consulted.– To develop patient in<strong>for</strong>mation (See Annex 3.1.), a search has been per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>for</strong> pamphletsand other documents containing in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>for</strong> the patient/carer both in printed and electronic<strong>for</strong>mats. To this end, all documents identified in the websites of three relevant organizations(www.feacab.org, www.itacat.com and www.adaner.org) that comprise the majority ofassociations declared of public use at a national level through their different delegations andsupport groups and the material provided by the clinical coordinator have been reviewed.Following the review of these documents, a content comparison table was elaborated from whichthe table of contents was developed. Once consensus of the final version had been reached bythe working group and collaborating experts, the Association in Defence of Anorexia Nervosaand Bulimia Management (ADANER) and the Spanish Federation of Support Associations <strong>for</strong>Anorexia (FEACAB), which include most local organisations, carried out an external review,using a specifically designed questionnaire that inquired on the suitability of the in<strong>for</strong>mationprovided, the examples used, style and language, etc. Although this in<strong>for</strong>mation is part of the<strong>CPG</strong> and must be delivered and explained to the patient/carer by health care professionals, wehope to edit individualised pamphlets that facilitate its dissemination.45CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR EATING DISORDERS