You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

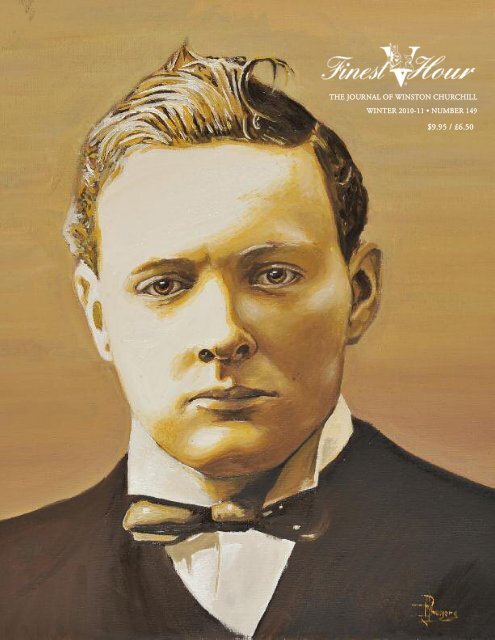

THE JOURNAL OF WINSTON CHURCHILLWINTER 2010-11 • NUMBER 149$9.95 / £6.50

Prime Minister? Had the situationsbeen reversed, and <strong>Churchill</strong> had “gotthere on his own,” I think FDRwould’ve lost Britain. <strong>Churchill</strong> wouldhave been over in the U.S. poundingthe podium, but with the lack of a parliamentarysystem, he’d have beenstuck out of it. I suppose we should behappy things were the way they were.DEAN KARAYANIS, VIA EMAIL• Them’s fightin’ words to someof our readers, I suspect! But it’s aninteresting speculation. —Ed.THANKS...I treasure my copies from 1991.I’ve always said it’s the best associationmagazine I have ever read—more ajournal that a magazine, a literary andhistorical work, a source of nostalgia.CYRIL MAZANSKY, NEWTON CENTER, MASS.THE “DRUNKEN OFFER”Nicely done on <strong>Churchill</strong>’s reunificationoffer to de Valera (FH 147:57). David Freeman’s exegesis of theworks of Terry de Valera and DiarmaidFerriter blows their allegations out ofthe water. I do find the PM’s innercircle defensive about his alcohol consumption,and there were others whocommented on his being worse for thewear on occasion. It’s plausible that hewas so exhilarated by the significanceof the Japanese attack that he celebratedwith an extra brandy or two. Sowhat? (Nor would an extra brandy havemade much difference.) His curioussense that Ireland was really “part ofthe family” was consistent, and hisoffer to de Valera was in character.WARREN F. KIMBALL, JOHN ISLAND, N.C.TOYEING AROUNDOn page 56, Richard Toye isquoted as quoting <strong>Churchill</strong> that theHindus were “protected by their ownpullulation.” I did not know that one.Do you know where it comes from?ANTOINE CAPET, UNIVERSITY OF ROUEN• The more we read of Toye’sopus the more we think we let it offlightly. The quotation is from theColville Diaries in Martin Gilbert’s<strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong> VI: 1232, whereColville writes of a conversation on 22February 1945:“The PM was rather depressed,thinking of the possibilities of Russiaone day turning against us….He hadbeen struck by the action of theGovernment of India in not removinga ‘Quit India’ sign which had beenplaced in a prominent place inDelhi....He seemed half to admire andhalf to resent this attitude. The PMsaid the Hindus were a foul race ‘protectedby their mere pullulation fromthe doom that is their due’ and hewished Bert Harris [RAF BomberCommand] could send some of hissurplus bombers to destroy them.”Taken in context with <strong>Churchill</strong>’ssour mood that night, the statement isunextraordinary, and we can believe itwas said (privately of course) with asmirk, since everyone knows <strong>Churchill</strong>never wished to wipe out the Hindus.Toye breathlessly quotes it as a kind ofshocking revelation that WSC hatedIndians—which is nonsense. —Ed.FROM OUR PATRONI have been greatly touched byFinest Hour 148 dedicating its cover tome to mark my 88th birthday. Thankyou so much.THE LADY SOAMES LG DBE, LONDONAMBIDEXTROUS?In FH 148: 34, <strong>Churchill</strong> isholding what appears to be a paintbrush in his left hand. Since he wasright-handed, was he ambidextrous, orwas the picture printed the wrong wayround?RODNEY CROFT, ENGLAND• The picture is not “flopped,”and we asked David Coombs aboutthis when we saw it. We concludedthat either <strong>Churchill</strong> occasionallytouched something up left-handed, orthat the thing in his left hand was asteadying rod used as a support for hisright hand when painting fine detail,which is sometimes seen in otherphotos of him at the easel. —Ed.CHURCHILL AND HITLERManfred Weidhorn’s remarkableanalysis (FH 148: 26-30) showing theFINEST HOUR 149 / 5numerous similarities of Hitler and<strong>Churchill</strong>—from being artists to notknowing how to surrender—linkedtogether these shared traits in a way Ihave not seen before. There is oneother similarity: Hitler like <strong>Churchill</strong>gained high office by democraticprocess. It wasn’t until Hindenburgretired that Nazism took full effect.RICHARD C. GESCHHKE, BRISTOL, CONN.• Professor Weidhorn replies:Good point, though to be precise, theNazis never obtained a majority voteunder the Weimar Republic (themaximum was 43.9% in the March1933 election), while the Conservativesdid. Hitler was head of the party andso automatically projected into power,while <strong>Churchill</strong> was on the marginsand was only belatedly and grudginglygiven power. There probably are othersimilarities I overlooked. I just tried tohit the big ones, as an exercise in life’sironies. Thank you for your observationand for the kind words.THE SUMMER OF ’41After Hitler invaded Russia,Clementine <strong>Churchill</strong> sponsored theBritish Red Cross Aid to Russia Fund.Aged 13, I assisted by running a locallending library, carrying a bag of booksaround on my bicycle and lendingthem to neighbours at one penny perweek. Over a few months I lent 504books and was able to contribute twoguineas to the fund.Little did I know that ten yearslater I would be taking the PrimeMinister’s wife out to dinner at a localhostelry in my capacity as chairman ofthe Woodford constituency YoungConservatives. I still have Mrs.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s letters of thanks.JOHN R. REDFERN, EPPING AND WOODFORDBRANCH, CHURCHILL CENTRE UK ,

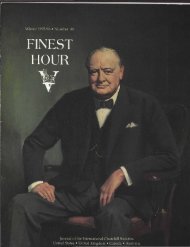

T H E M E O F T H E I S S U EThe Value of Intelligence, Then and NowConsidering articles for this issue, I searched—asalways—for a common thread around which tobuild the contents. On the surface, publicationreadyarticles seemed interesting but eclectic: one onYoung <strong>Winston</strong> and Mark Twain (ergo, our cover); a colorfulexposition of WSC’s travelogue My AfricanJourney; the <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre-NEH 2010 TeacherInstitute in England; the last of our San Francisco conferencepapers; book review on the alleged <strong>Churchill</strong>-Mussolini letters. But nothing, it seemed, jelled together.We had a lengthy article by Sir Martin Gilbert,spawned after one of our conversations on “LeadingMyths,” detailing <strong>Churchill</strong>’s global involvement withWorld War II Intelligence; and what Christopher Sterlingcalled a “technology footnote,” on security methods forwartime phone conversations. Far more important thanhis modest title suggested, this was in fact the beginningof the modern digital age.Intelligence, perhaps? The theme still needed bolstering.<strong>Churchill</strong> was deeply involved with intelligencelong before World War II.I thought of David Stafford, the great intelligencescholar, author of the best books on the subject, and anold friend. I asked if I might republish his remarks at our1996 Conference on <strong>Churchill</strong> and intelligence fromWorld War I to Pearl Harbor to 1953 Iran (yes, Iran;fancy that!)—subjects which dovetailed quite nicely withSir Martin’s commentary. And lo, we were on our way.By good fortune arrived a human interest story byMyra Collyer, an 86-year-old ex-WAAF who had helpeddecypher aerial reconnoissance photos with none otherthan Sarah <strong>Churchill</strong>. It was ideal to “pace” the issue,between the technical articles. Almost there! But Iwanted an article to stitch it together in modern context.What might we learn today by comparing the nearreverencewith which <strong>Churchill</strong> treated intelligenceinformation—his “Golden Eggs,” he often called it—compared to our modern, lackadaisical approach to it?Why, for example, aren’t more of today’s leaders callingfor “WikiLeaks” to be prosecuted for posting secret documentson the Iraqi and Afghan wars for the wholeworld, including the enemy, to peruse? What would<strong>Churchill</strong> think about that?I asked David Freeman, who has the critical facultyand historical perspective to consider that question. Heduly produced a reminder that <strong>Churchill</strong> had actuallyfaced something similar. Suddenly we had another“themed” issue of Finest Hour.And then there was the back cover. Imagine mysatisfaction in realizing, as the layout process started, thatDanny Rogers, the gifted artist who portrays “Young<strong>Churchill</strong>” on our cover, had also painted Alan Turing,proclaimed a hero by WSC: the Bletchley encryptionexpert who had designed the “bombe” machine whichbroke the German Enigma. Rounding off the theme withTuring on the back cover was as if the ghost of Sir<strong>Winston</strong> were guiding us with an invisible hand.Only in Finest Hour, I suppose, could we expect toread so much on one aspect of <strong>Churchill</strong>, and the workof such contributors—writers who for forty years havehelped us explore what Sir Martin calls “The Vineyard,”and Lady Soames “The Saga.” This issue is truly thework of the best people in their spheres—which it is myprivilege to refract.Where else could we find such expert and goodscholars as Gilbert, Stafford, Sterling and Freeman, toinform us about <strong>Churchill</strong> and intelligence? To whomdoes Christopher Schwarz turn to publish his account of<strong>Churchill</strong> and Twain? Ronald Cohen, the great bibliographer;Arthur Herman, Pulitzer Prize nominee; SuzanneSigman, our education leader and exemplar; columnistsMcMenamin and Lancaster; artist Daniel Rogers;Patrizio Giangreco, ever ready to help us dismember sillybooks by Italians; senior editors Muller and Courtenay,without whose polish FH would be a lesser product; Sir<strong>Winston</strong> himself, the craftsman whose words resoundregularly in our pages—all are represented.It is overpoweringly satisfying to know that FinestHour has established that no one or two people are indispensableto its role as the Journal of <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>:the magazine that keeps the tablets. I look at FH and sayto myself that it is kept alive by people who dare tobelieve that <strong>Churchill</strong>’s inspiration isn’t dead, can’t bepermitted to die—who make sure that they, their childrenand grandchildren have, to plead <strong>Churchill</strong>’s causeand irradiate his wisdom, this little beacon of faith. ,FINEST HOUR 149 / 6

D A T E L I N E SWhether or not he ultimately succeeds,he has established that there is a largeaudience for truth and reason—perhaps a larger one than for theircheaply appealing opposites.—JOHN O’SULLIVAN IN NATIONAL REVIEW¡VIVA CHILE!LONDON,OCTOBER18TH— Baskingin the glory ofthe Chileanmine rescue,Chile’sPresidentSebastian Piñera began a state visit toBritain with a tour of the <strong>Churchill</strong>War Rooms. Sr. Piñera refrained fromrepeating the words “blood, toil, tearsand sweat” from his boyhood hero’s1940 speech, which he had kept at hisside during the miners’ ordeal. But hesat in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s wooden chair andpulled from a suit pocket a sack containinga lump of rock taken from theSan José mine, from which thirty-threeminers were freed after sixty-nine daysbelow ground. He also offered as a giftto the War Rooms’ director Phil Reed afacsimile of the first, red-lettered notesaying “Estamos bien en el refugio, lostrente-tres” (“We are doing well in ourrefuge, the thirty-three.”) In return,Mr. Reed gave the President a book of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s quotations.Overseen by Piñera in a 22-houroperation, at the end of which hehugged each miner as he emerged fromthe emergency chute bored 622 metresunder the Atacama desert, the extraordinaryrescue lifted his poll ratings andChile’s international standing, providingthe ideal springboard for hislong-planned tour of Europe.A billionaire businessman, theHarvard-educated economist hoped hisvisit would underline Chile’s transitionfrom an insular dictatorship to a democraticeconomic power, and attractinvestment. He is also hoping to banishany lingering memories of AugustoPinochet, the last Chilean head of stateto make headlines in the UK duringhis arrest twelve years ago for murderingcivilians during the 1970s.President Piñera gave HM TheQueen and Prime Minister Cameronfragments of the mine in bags bearingthe legend: “In your hands are rocksfrom the depths of the earth and thespirit of thirty-three Chilean miners.”He later brought similar gifts to FrenchPresident Nicolas Sarkozy and GermanChancellor Angela Merkel. But hechose the War Rooms for his first dayin Europe.The 60-year-old, who said he wascurrently re-reading <strong>Churchill</strong>’s TheSecond World War, was shown theCabinet Room, the Map Room,WSC’s private quarters and the<strong>Churchill</strong> Museum. He also met<strong>Churchill</strong>’s granddaughter, CeliaSandys, 67. “Chile,” Piñera said, “hasgiven a good example of the realmeaning of commitment, courage,faith, hope and unity. We did itbecause we were united. We did itbecause we were convinced. We did itbecause we would never leave anyonebehind, which is a good principle forChile and for the world.”—MARTIN HICKMAN IN THE INDEPENDENTSOMERVELL AWARD 2010CHICAGO, OCTOBER 15TH— NevilleBullock’s “Eye-Witness to Potsdam”(Finest Hour 145) was selected by theFH editorial board for the 2010Somervell Award, for the best articleappearing over the past year (numbers#144-47).There were many strong contendersamong those four issues,including Martin Gilbert’s “A Plan ofWar Against the Bolsheviks” andWarren Kimball’s “The Real ‘Dr. Winthe-War.’”But Bullock’s recollection ofhis time at Potsdam impressed ourboard with its insight.“It is always good to hear aworm’s-eye view from an intelligentand observant worm,” wrote senioreditor Paul Courtenay. David Freemanadded: “I found it to contain a gooddeal of strong, impressionable materialthat could be incorporated into my lectures.”Said Terry Reardon: “I liked thearticles on Ed Murrow and HarryHopkins. But I give my vote to thisfirsthand account: informative andhighly entertaining.”The Somervell Award, formerlythe Finest HourJournal Award, wasrenamed at the suggestionof DavidDilks for the Harrowmaster who taughtyoung <strong>Churchill</strong>English. PreviousSomervellwinners were: PaulAlkon for the Lawrence of Arabia features,FH 119; Larry Arnn for “NeverDespair,” FH 122; Robert Pilpel for“What <strong>Churchill</strong> Owed the GreatRepublic,” FH 125; Terry Reardon for“<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> and MackenzieKing,” FH 130; David Dilks for “TheQueen and Mr. <strong>Churchill</strong>,” FH 135;Philip and Susan Larson for“Hallmark’s <strong>Churchill</strong> Connection,”FH 137; and David Jablonsky for “The<strong>Churchill</strong> Experience and the BushDoctrine,” FH 141.STALIN CORRESPONDENCEMOSCOW, APRIL 15TH— Russian historianVladimir Pechatnov has received majorfunding from the Russian governmentto support a new annotated edition ofStalin’s correspondence with Rooseveltand <strong>Churchill</strong>, using archival memosand papers that indicate what Stalinand company were really thinking. Heclaims full access to dig out the kind ofmaterial that Oleg Rzheshevsky producedin an initial way in his War andDiplomacy. Petchatnov is also workingto arrange an English translation. Oneof FH’s contributors had a long talkwith Petchatnov in Moscow about thisproject. It will be helpful to have a newcollection to replace various editions ofthe correspondence compiled withoutaccess and/or references to Russianarchival material.THE YOUTH VOTEWe were asked recently what we’vebeen doing to promote interest inWSC among young people. A trollthrough the past two years of FinestHour and the Chartwell Bulletin providesa list of events and peopleresponsible, though there are more:First Teacher Institute with NEHgrant support, Ashland University,Muller/Lyons/Sigman, 2007.<strong>Churchill</strong> in Advance PlacementFINEST HOUR 149 / 8

History, Bob Pettengill, CB 17.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Scotland Tour atDundee University, CB 17.Peacock College Students re-erectfirst <strong>Churchill</strong> Statue, CB17.Education Programs atVanderbilt University, Chicago, Seattleand Atlanta, CB 17.<strong>Churchill</strong>, Achievement andLiberty, by Bill Clinton & George W.Bush, FH 140.Baylor University StudentSeminar, Kimball/Muller, CB 17.William & Mary StudentSeminar, Sigman/Muller, CB 17.Changing Views of WSC since1968, by twenty authors, FH 140.Second NEH-TCC TeacherInstitute, Cambridge and London,Muller/Sigman, CB 18.<strong>Churchill</strong> and Family, by MarySoames, FH 140.<strong>Churchill</strong> and Statesmanship,Pittsburgh Teacher Seminar, SuzanneSigman, CB 19.Thought and Action in the Lifeof WSC, San Diego Seminar,Muller/Kambestad, CB 19.<strong>Churchill</strong> for Today, 2009Conference, Myers/Kambestad, CB 19.Finest Hour Online, by JustinLyons, FH 143.Young <strong>Winston</strong>’s WritingsShaped a Hero, by undergraduateAllison Hay, FH 143.Hillsdale College H.S. TeacherSeminar, Bob Pettengill, CB 20.Graduate Seminar at Chicago,Muller/Rahe, CB 20.Williams College LeadershipProgram, Warren Kimball, CB 20.High School Seminars inArizona, Massachusetts, Michigan andChicago, Suzanne Sigman, CB 20.Interviews with <strong>Churchill</strong> aged31 and 35, by Bram Stoker andHerbert Vivien, FH 144.What I Admire about <strong>Churchill</strong>,by student Timon Ferguson, CB 21.Going Live with the NewWebsite, John Olsen, CB 21.Placing <strong>Churchill</strong> in Classroomsand Curricula, Suzanne Sigman, CB 21.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s Futurist Essays and<strong>Churchill</strong> for Today, FH 146.<strong>Churchill</strong> College, Illinois, Phil &Susan Larson, FH 146. >>AROUND & ABOUTThe Wall Street Journal observed on September17th that proposals for the U.S. government to punishChina for its overvalued yuan with protective tariffs arebad policy: “…pegging the yuan to the dollar is not ‘currencymanipulation’ or ‘stealing American jobs’…China’s real sin is sterilization,which insulates its domestic economy from the money-creating effect of acurrency board.”Quoting Milton Friedman’s A Monetary History of the United States,the Journal says that in 1921-29, “when the world used gold instead ofdollars for monetary reserves, the [U.S.] gold stock grew by about 50%,reflecting its trade surplus. [But] from 1923 on, a policy of sterilizationcaused the level of high-powered money to remain stable, and wholesaleprices fell 8% from 1925-29. This short-circuited the self-correcting mechanisminherent in the gold standard, which is akin to a universal currencyboard when all currencies are pegged to gold. The U.S. should have seenan increase in the money supply, causing higher prices and over the longterm tending to restore trade balances.“Instead the Federal Reserve wreaked havoc on countries trying tostay on or rejoin the gold standard, especially Britain, which was hemorrhaginggold. It was forced into a period of deflation and couldn’t competewith the American export juggernaut. London responded with protectionismin the form of Imperial Preference, which contributed to the GreatDepression, and the gold standard system collapsed.”The reader who sent us this cutting added: “It’s too bad no one understandsthis except the Wall Street Journal. When <strong>Churchill</strong> decided tosupport Imperial Preference in the late 1920s, he was not abandoning FreeTrade, but reacting to U.S. monetary policy, desperate to defend Britainagainst the Fed.”The editor is very muddy where economic theory is concerned, butthis seems to make some sense. Though <strong>Churchill</strong> said his decisions asChancellor of the Exchequer only mirrored recommendations of the Bank ofEngland, the Bank at that time was as pro-gold as the late Dr. Friedman.We would welcome an article from a qualified reader who can explain allthis to us “on one sheet of paper.” Or, say, 1500 words.kkkkkTed R. Bromund in Commentary magazine, 27 August: “On FoxNews Sunday, a slightly incredulous Chris Wallace asked former IllinoisGovernor Rod Blagojevich if he were serious when he compared himself to<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> in his ability to come back from political oblivion.Blagojevich replied: “You’re right, I’m not serious. I don’t smoke cigars ordrink scotch, and I think I can run faster than him.”Bromund, who quoted <strong>Churchill</strong>’s reply to teetotaler Field Marshal SirBernard Montgomery (“I drink and smoke and am 200% fit”), went on torecall <strong>Churchill</strong>’s note to his War Secretary in 1941 (published in The GrandAlliance): “Is it really true that a seven-mile cross-country run is enforcedupon all in this division, from generals to privates?....A colonel or a generalought not to exhaust himself in trying to compete with young boys runningacross country seven miles at a time….Who is the general of this division,and does he run the seven miles himself? If so, he may be more useful forfootball than war. Could Napoleon have run seven miles across country atAusterlitz? Perhaps it was the other fellow he made run. In my experiencebased on many years’ observation, officers with high athletic qualificationsare not usually successful in the higher ranks.” Perhaps, Bromund adds,“<strong>Churchill</strong>’s maxim also applies to governors.” Well done, Mr. Bromund. ,FINEST HOUR 149 / 9

D A T E L I N E SVancouver student speakersTimon Ferguson/Kieran Wilson, CB 23.Young <strong>Winston</strong> on Afghanistan,Then and Now, FH 147.How Bad a Student Was Young<strong>Churchill</strong>?, CB 24.Students’ Choice, Best Recent<strong>Churchill</strong> Books, John Rossi, FH 148.Googleworld: New Generationsand the Concept of Joining, FH 148.Third Teacher Institute,Sigman/Muller, Summer 2010 (p. 45).ERRATA, FH 148Page 4: The letter on “...Prayersand the Lash was from James Mack inOhio, not Don Abrams—sorry.Page 7: Sidney Allinson remindsus that the Duke of Hamilton did notpersonally arrest Rudolf Hess, who washeld by ploughman David Maclean forthe Home Guard. The Duke interviewedHess, confirmed his identityand spoke to <strong>Churchill</strong>; one source sayshe was “summoned to Ditchley.” TheDuke was appalled at the thought thathis loyalty might be questioned.USS CHURCHILL RESCUEADEN, SEPTEMBER27TH— At leastthirteen Africanmigrants weredead after a U.S.Navy rescuemission in theGulf of Adenwent awry. USS<strong>Winston</strong> S.Finest Hour 110<strong>Churchill</strong> wascoming to the aid of eighty-five peopleadrift in an overcrowded motor skiff inthe busy shipping lanes between thecoasts of Yemen and Somalia. The boatwas initially discovered by a Koreanvessel, which passed its location to the<strong>Churchill</strong>, whose crew members wentto the skiff and tried to repair brokenengines but were unsuccessful. Thecrew then began towing it out of thesea lanes toward the coast of Somalia.As the crew of the <strong>Churchill</strong> attemptedto provide them with food and water,the passengers rushed to one side of thevessel, which capsized, throwing all ofthem into the water. Sailors from the<strong>Churchill</strong> rescued sixty-one.The Gulf of Aden is an importantshipping route between theMediterranean and the Indian Ocean.Somali pirates have lately hijackedseveral cargo vessels. In addition, theUnited Nations estimates 74,000Ethiopians and Somalis fled to Yemenas refugees in 2009. Most cross theGulf of Aden in overcrowded vesselsrun by smugglers. —NBC NEWSBUTTERFLIES RETURNCHARTWELL, KENT, AUGUST 19TH— The butterflyhouse where Sir <strong>Winston</strong> wouldindulge his passion for breeding rareinsects has been rebuilt. As a youth,WSC was an avid lepidopterist, collectingand pinning specimens fromthen-teeming fields around Harrow. Hereturned to the hobby periodically,with travels through South Africa,India and Cuba. At Chartwell, newbreeding cages allow visitors to experiencehis butterfly garden with itsinsect-friendly lavender borders andbuddleia jungles, just as WSC enjoyedthem in the Forties and Fifties.Matthew Oates, the NationalTrust conservation adviser, said<strong>Churchill</strong> contacted L. Hugh Newman,a towering figure in the butterflyworld, in 1939 after Newman movedto within five miles of Chartwell.Newman persuaded an eager <strong>Churchill</strong>to reintroduce species such as theblack-veined white and European swallowtail,and to convert the under-usedsummer house. Sadly, the attempt wasnot a success, Oates said: “He startedoff with a plan to breed species whichwere native to southern England butthen overreached himself with theseattempts, which ended in rather spectacularfailure.”Since <strong>Churchill</strong>’s death, half adozen butterfly species have disappearedfrom the Weald of Kent andpopulations of survivors have morethan halved in number. The newbreeding attempts, concentrating oncommon species, will not restoredepleted populations, ravaged by consumptionof habitats for farming andbuilding. Instead they are intended togive a more authentic history experiencefor visitors to Chartwell.More serious conservation workFINEST HOUR 149 / 10is takingplace amidthe swathesof grasslandin thegrounds,which arebeing leftButterfly Walk, Chartwellunmownthrough the growing season in anattempt to stimulate insect numbers.This is what the great man wouldhave wanted, said Mr. Oates. “I wouldargue very strongly that <strong>Churchill</strong> wasa pioneer wildlife gardener, and viewhim as a bit of a champion of wildlifeand butterflies.” Nigel Guest of the CCChartwell Branch, and a volunteer atChartwell, writes: “I can confirm thatthe revitalised butterfly house is a terrificinnovation and attraction. Lastyear was a superb year for butterfliesand negotiating the butterfly walk wasdifficult because there were so many ofthese beautiful creatures adorning theplants and the ground.”<strong>Churchill</strong>’s FavouritesPeacock: This feature of summergardenscamouflagesitself againsttree trunksand can facedown predatorssuch asmice by hissing and flashing thestriking “eyes” found on its hindwings.Small Tortoiseshell: hundreds oftortoiseshellsadded colourto gardenparties atChartwell.They havedeclined in recent years, possiblyaffected by a parasitic fly which thrivesin warmer, wetter conditions.European swallowtail: A raremigrant fromthe continent,it is related toBritain’slargest, rarestbutterfly.<strong>Churchill</strong>failed to breed these at Chartwell.

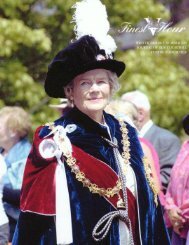

Painted Lady: A North Africanvisitor whichmakes a latesummermigration toBritain whenits numbersbecome unsustainable in native habitat.Black-veined White: A largewhitespeciesrecordedin the17thcentury,it disappearedin Britain around 1925,probably a victim of disease or predation.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s efforts to establish itat Chartwell failed.—JONATHAN BROWN, THE INDEPENDENTRepublished by kind permission; full article isat http:// xrl.us/bh5vi9. Photos by Etoile andKathyscola on Flickr and the Scottish RockGarden Club (www.srgc.org.uk).See also Hugh Newman, “Butterflies toChartwell” (FH 89: 34-39); and RonaldGolding, “Guarding Greatness,” (FH 143:32), where bodyguard Golding recalls how<strong>Churchill</strong> responded to Newman when hebecame a little too patronizing.GARTER CEREMONY 2010WINDSOR, JUNE 14TH— In 1348 King EdwardIII created the Most Noble Orderof the Garter; in addition to TheQueen and other royal persons, thecomplement is restricted to twenty-fourmembers, who are termed KnightsCompanion (KG) and Ladies Companion(LG). Chosen personally by TheQueen, they are among the most eminentpeople in the United Kingdomand other Commonwealth countries ofwhich she is also Queen.Since 1348, 1002 membershave been appointed, notablySir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>in 1953; his daughter, LadySoames, was admitted in2005.There is a romanticlegend about the Order’sorigin: at a court ball, theCountess of Salisbury’sgarter slipped to the floor and theKing, retrieving it, wrapped it roundhis own leg; as onlookers sniggered,the King said, “Honi soit qui mal ypense” (Shame on him who thinks evilof it). This became, and remains, themotto of the Order of the Garter. Butthe more likely explanation is that theGarter is a badge of unity and concord,possibly representing a sword-belt.Each June, Knights and Ladies ofthe Order of the Garter accompanyThe Queen to St. George’s Chapel atWindsor Castle for their annualservice. A magnificent procession isformed, led by the Military Knights ofWindsor, and the officers of theCollege of Arms (kings-of-arms, heraldsand pursuivants), with the Knights andLadies of the Order ofthe Garter followingthem. The Queen’sBodyguard of theHonourable Corps ofGentlemen at Armsand The Queen’sBodyguard of theYeomen of the Guardare also on duty.This year LadySoames invited mywife and me to bepresent in St. George’sChapel. We had asplendid front-rowview of the panoply ofstate as it made itsway into the chapelFinest Hour 129and—at the end—out again.Although the spectacle wasunforgettable, the purpose ofthe event could not be overlooked.It was a religiousobservance, in which theKnights and Ladies of theOrder of the Garter heldtheir annual service ofthanksgiving. I can do nobetter than record one of theAnglican prayers:“Almighty God, in whose sight athousand years are but as yesterday: Wegive thee most humble and heartythanks for that thou didst put into theheart of thy servant, King Edward, tofound this order of Christian chivalry,and hast preserved and prospered itthrough centuries until this day. Andwe pray that, rejoicing in thy goodness,we may bear our part with those illustriousCompanions who have witnessedto thy truth and upheld thine honour;through the grace of our Lord JesusChrist, himself the source and patternof true chivalry; who with thee and theHoly Spirit liveth and reigneth, everone God, world without end. Amen.”—PAUL H. COURTENAY ,Lady Soames between Sir John Major(former Prime Minister) and LordBingham of Cornhill (former Lord ChiefJustice) in an earlier year.Right: Shortly afterpublishing“Googleworld” lastissue, we read thiscounterattack by themagazine industry.We hope they’re right.FINEST HOUR 149 / 11

C H U R C H I L L A N D I N T E L L I G E N C EAdventures in Shadowland, 1909-1953<strong>Churchill</strong> valued secret intelligence more than any other politician of his century.Without him, the modern intelligence community might never have developed as it did.D A V I DS T A F F O R DCÓNSUL BRITÁNCO MADRIDPHILLIPE HALSMAN, 1950CHANCE ENCOUNTER of a cryptic1949 telegram from Alan Hillgarth inSpain to <strong>Churchill</strong> in London led to apreviously unknown, privateintelligence mission conducted by<strong>Churchill</strong> while out of office: keepingtrack of Soviet spies in Europe.In early 1995, after a week’s intensive work in the<strong>Churchill</strong> Archives at Cambridge, researching my book<strong>Churchill</strong> and Secret Service, I opened yet another file ofdocuments. I had reached that dangerous stage, rarelyadmitted by historians, of secretly hoping it would containnothing that demanded more tedious note-taking.It was marked “Private correspondence, 1949.” Thiswas promising for my unworthy hopes. After his triumphsin the Second World War, everyone wrote to <strong>Churchill</strong>, agreat deal of it inconsequential. With luck I might finishthis file quickly.Speeding through a bizarre miscellany of invitations tolectures, garden fetes, school prize-givings, even the blessingof babies, I came upon a telegram from Spain. It wasaddressed to <strong>Churchill</strong> at his London home at 28 HydePark Gate. There were only four lines. This is what it said:MESSAGE RECEIVED VERY LATE AS WAS TRAVELLINGAPOLOGIES STOP NUMBERS INCLUDING MINOR PARTS ANDATTACHMENTS IN BOTH CASES ARE NOW TWO HUNDRED ANDTHIRTY SIX THEIRS AND ONE HUNDRED AND THIRTEEN OURSWhat did it signify? Crates of sherry consumed bySpanish and British Cabinet members? Comparative advantagesof rival cigar-rolling devices? My eye was suddenlycaught by the name of the sender: Alan Hillgarth.I instantly knew that I had stumbled on someunknown episode in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s adventures with the secret____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________Dr. Stafford, of Victoria, B.C., was for many years project director at Edinburgh University’s Centre for the Study of the Two World Wars andLeverhulme Emeritus Professor in the University’s School of History, Classics and Archaeology. A preeminent intelligence scholar, his books includeCamp X: Canada’s School for Secret Agents, 1941-1945 (1986); The Silent Game: The Real World of Imaginary Spies (1988); Spy Wars: Espionageand Canada, with J.L. Granatstein (1990); <strong>Churchill</strong> and Secret Service (1998, reviewed FH 96); and Roosevelt and <strong>Churchill</strong>: Men of Secrets (2000,reviewed FH 110). His latest book is Endgame, 1945: The Missing Final Chapter of World War II (2007, reviewed FH 139). This article is excerptedfrom his paper, “<strong>Churchill</strong> and the Secret Wars,” 13th International <strong>Churchill</strong> Conference, Ashdown Park, East Sussex, England, October 1996.FINEST HOUR 149 / 12

world. I recognised Hillgarth’s name from my book aboutthe top secret agency <strong>Churchill</strong> created in 1940 to “setEurope ablaze” with the fires of sabotage and subversion,the Special Operations Executive (SOE).Hillgarth was just the sort of maverick adventurer towhom <strong>Churchill</strong> was magnetically drawn. Wounded as a16-year-old Royal Navy midshipman at the Dardanelles, hehad, he hinted, smuggled guns during the 1920s Riff rebellion—whentribal insurgents in Spanish Morocco dealtSpain one of the most severe reverses ever sustained by aEuropean colonising power at the hands of natives. LaterHillgarth went broke sinking a gold mine in Bolivia, andwrote a rollicking cloak and dagger novel of adventure andintrigue which even caught the eye of Graham Greene.The Spanish Civil War found him as British Vice-Consul in Majorca. By 1940 he was in Madrid for thatanxious period when <strong>Churchill</strong> feared that neutral Spainunder General Franco might join forces with Hitler.Nominally the British naval attaché, in reality Hillgarthhelped supervise Britain’s secret intelligence, sabotage, andsubversion operations in Spain.<strong>Churchill</strong>, who had met Hillgarth in Majorca in the1930s, regarded him with particular trust, interviewing himpersonally in London and circulating his reports to the WarCabinet. He also employed him on at least one particularlysensitive mission. In September 1941, Hillgarth visitedChequers to discuss ways of keeping Spain out of the war.As a result <strong>Churchill</strong> stage-managed the unblocking of $10million secreted in a Swiss Bank account in New York.Shortly afterwards the “Knights of Saint-George,” otherwiseknown as British gold sovereigns, were riding to war, liningthe pockets of Spanish generals willing to argue the neutralitycase with General Franco. Hillgarth, like <strong>Churchill</strong>,had had “a good war.” Ian Fleming, a close friend, calledhim “a useful petard and a valuable war winner.”But what was Hillgarth doing sending a telegram to<strong>Churchill</strong> in 1949?In fact, the telegram’s mysterious figures referred tothe number of intelligence officers, British and Soviet, inMoscow and London respectively. During this period, theCold War in Europe was becoming glacial. In 1945 IgorGouzenko, a junior cypher clerk, had walked out of theSoviet mission in Ottawa a month after Hiroshima andNagasaki, carrying beneath his coat documents that exposeda massive Soviet intelligence offensive against the West. Sixmonths later <strong>Churchill</strong> had delivered his “Iron Curtain”speech in Fulton, Missouri. In 1948 Prague fell to theCommunists and the Russians imposed their blockade ofBerlin. <strong>Churchill</strong>, in opposition since 1945, was anxious toexpose Soviet and Communist misdemeanours and calledfor vigilance against Moscow’s spies and Fifth Columnsaround the globe.In 1949 Hillgarth was retired and living in Ireland.But he travelled, and kept valuable contacts with old intelligenceand military friends in London. Even while out ofoffice, <strong>Churchill</strong> relied on private information to keep himinformed...right up to October 1951, when WSC returnedto Downing Street.Throughout his life <strong>Churchill</strong> relished the hands-oncontact with agents normally reserved to case officers.The Second World War—as my book demonstrated—is littered with examples of <strong>Churchill</strong> listening spellboundto the exploits of heroic young agents returned from behindenemy lines. Hillgarth was part of a long tradition.Sir Martin Gilbert’s official biography has revealed indetail how in the 1930s, a voice crying in the wildernessagainst the threat of Hitler, <strong>Churchill</strong> turned Chartwell intoa massive private intelligence centre. His best knowninformant was Desmond Morton, an officer in the SpecialIntelligence Service and head of the Industrial IntelligenceCentre. Morton became the Prime Minister’s official adviseron intelligence during the Second World War. Yet his namenever once appears in the Chartwell visitors book. Indeed itseems extraordinary that while still in opposition, <strong>Churchill</strong>could calmly invite an SIS officer to Chartwell to chatabout intimate secrets of state over lunch.Only within the last two decades or so has it becomepossible for scholars to write intelligence history. And as theshadows have lifted, we can see with increasing clarity >>“Even while out of office, <strong>Churchill</strong> relied on private sources ofinformation to keep him informed....Sir Martin Gilbert’s officialbiography has revealed in detail how in the 1930s, a voice crying in thewilderness against the threat of Hitler, <strong>Churchill</strong> turned Chartwell into amassive private intelligence centre. [We are] littered with examples of<strong>Churchill</strong> listening spellbound to the exploits of heroic young agents....”FINEST HOUR 149 / 13

CHURCHILL AND INTELLIGENCE...that <strong>Churchill</strong> enjoyed lifelong contacts with the secretworld that go back well before the First World War. It isclear that he valued secret intelligence more than any otherBritish politician of this century. Without <strong>Churchill</strong>, themodern intelligence community might never have taken theshape it did.World War ILet us briefly go back to the decade when Europe wasapproaching the fateful guns of August 1914. Behind thearms race raged bitter intelligence battles. Each Great Powerspied on its rivals and protected its secrets. Late as usual,Britain joined this continental game in 1909, when theCommittee of Imperial Defence approved the creation of aSecret Service Bureau. By the outbreak of war it consisted ofthe two branches that still exist today: MI5 for counterespionageand MI6—otherwise known as the SecretIntelligence Service or SIS—for foreign intelligence. Notsurprisingly, both MI5 and MI6 focussed on naval affairs.The former sent spy-catchers to sniff out German spiesnosing around naval installations in Britain. The latter sentagents to uncover the Kaiser’s naval plans. Both, being newand untried, had difficulty in gaining the ears of ministers.<strong>Churchill</strong> was the outstanding exception.It was natural that as First Lord of the Admiralty from1911 to 1915 he should be interested, as he hints in TheWorld Crisis. What he carefully concealed was the provenance,the intensity, and the significance of his influence onthe infant secret service. Richard Burdon Haldane, Secretaryof State for War in the pre-war Liberal Government, chairedthe 1909 committee that recommended its creation. TheDirector of Military Intelligence was a fellow Scot,Lieutenant-Colonel John Spencer Ewart, a veteran ofOmdurman. In November 1909, just weeks after the SecretService Bureau began its work, Haldane asked Ewart to goand talk to the young man concerned—the President of theBoard of Trade, <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>.The meeting took place on 15 November 1909 in<strong>Churchill</strong>’s private office, the bronze bust of Napoleon thathe carried with him from ministry to ministry carefullypositioned on the desk between them. It sparked a lifelonglove affair between <strong>Churchill</strong> and the Secret Service. He wasdeeply alarmed by what he had witnessed in Germany.Intrigued by Ewart’s mission, within weeks <strong>Churchill</strong> hadsent him a sixty-page memorandum packed with Board ofTrade data about German commerce.From then on, <strong>Churchill</strong> saw the Secret Service as vitalto national security. As Home Secretary, he eagerly promotedMI5 demands for greater surveillance powers: itslegendary registry of spies and potential subversives—whathas been described as “the most important and controversialweapon in the British counter-intelligence armoury.” It was<strong>Churchill</strong> who first authorised the clandestine interceptionof private mail by general warrants; and who conceived thelegislative sleight of hand by which the drastic third OfficialSecrets Act was slipped through Parliament in 1911.In 1994 Stella Rimington, then Director-General ofMI5, visited Edinburgh. I was able to engineer a few wordswith her. “Ah yes, <strong>Churchill</strong>,” she said briskly when I toldher of my book. “He opened all the doors when my predecessormade his first nationwide tour in 1911.”As Europe slid towards war <strong>Churchill</strong> kept in constanttouch with the man she meant: Sir Vernon Kell, the firstdirector of MI5. By the end of July 1914 he was livinground the clock in his office, surrounded by telephones. Itwas on one of these that, late on August 3rd, <strong>Churchill</strong> rangand ordered him to take the preemptive action the two hadlong been planning. The next day, as war officially began,suspected German spies on Vernon Kell’s secret list werearrested in a nationwide swoop by the Special Branch.Kell is not the only important intelligence player ofthis period in <strong>Churchill</strong>’s life. Sir Alfred Ewing, Director ofNaval Education, yet another Scot, was a short, thick-setman with keen blue eyes and ill-kempt shaggy eyebrows.His first wife was a great-great grandniece of GeorgeWashington. On the day war began, he turned up in<strong>Churchill</strong>’s office with Admiral Sir Henry Oliver, theDirector of Naval Intelligence, also a Scot—a taciturn figureof such silent discretion that he was known throughout theNavy as “Dummy” Oliver. They wanted to interceptGerman navy radio signals.<strong>Churchill</strong> immediately agreed and put Ewing incharge. By November, hidden deep within the Admiralty, acode breaking agency known as Room 40 had begun itswork. Three years later its greatest coup came with thedecyphering of the Zimmerman telegram that so memorablyhelped bring the United States into the war.Room 40 was the progenitor of World War II’sBletchley Park and of Britain’s present-day GovernmentCommunications Headquarters (GCHQ), that greatvacuum cleaner in the sky that works in tandem with theAmerican National Security Agency and other allies tosweep up signals intelligence from around the globe.<strong>Churchill</strong> was fascinated by Room 40’s work. He personallywrote out in longhand its founding charter andspent many an hour watching the codebreakers at theirwork. He captured the thrill in The World Crisis:...in Whitehall only the clock ticks and quiet men enter withquick steps laying slips of pencilled paper before other menequally silent who draw lines and scribble calculations andpoint with the finger or make brief subdued comments.Telegram succeeds telegram...as they are picked up anddecoded...and out of these a picture always flickering andchanging rises in the mind and imagination...Thus the statesman who so valued his secret intercepts inthe Second World War that he described them as hisFINEST HOUR 149 / 14

They Owed <strong>Churchill</strong>—and He Owed Most of Them...DESMOND MORTON (1891-1971)joined the SIS in 1919 and headedthe Industrial Intelligence Centre,Committee of Imperial Defence, 1929-39. Living close to Chartwell, it was asimple matter to walk over and brief<strong>Churchill</strong> with crucial intelligence onthe rearmament of Germany. Hisname never appeared in theChartwell Visitors Book.JOHN SPENCER EWART (1861-1920), War Office Director of MilitaryOperations, was sent by Haldane tobrief <strong>Churchill</strong>, then President of theBoard of Trade, on the the new SecretService Bureau. Captivated by thepotential value of the concept,<strong>Churchill</strong> furnished Ewart with a 60-page report on German commerce.ALFRED EWING (1855-1935), a short,thick-set Scot with ill-kempt shaggy eyebrows,was put in charge by <strong>Winston</strong><strong>Churchill</strong> of the World War I codebreakingagency known as Room 40. Itwas the predecessor to World War II’sBletchley Park and today’s GovernmentCommunications Headquarters (GCHQ),which shares intelligence with the U.S.National Security AgencyRICHARD BURDON HALDANE(1856-1928), Secretary of State forWar, 1905-12, chaired the committeethat recommended the creation of aBritish Secret Service Bureau. Itquickly evolved into two branches thatstill exist today: MI5 for counter-intelligenceand MI6 (Secret IntelligenceService) for foreign intelligence.SIR VERNON KELL (1873-1942),founder and first Director General ofMI5. On 3 August 1914, <strong>Churchill</strong> rangKell to signal the action they had longcontemplated: a nationwide round-upof suspected German spies by theSpecial Branch. As Prime Minister inJune 1940, <strong>Churchill</strong> removed theailing Kell shortly before his death.STELLA RIMINTON (1935-), John Major’shighly visible Director General of MI5, 1992-96. She famously opposed national ID cardsand described the American response to the9/11 attacks as a "huge overreaction.” Latershe warned that Prime Minister GordonBrown should be “recognising risks, ratherthan frightening people in order to be able topass laws which restrict civil liberties, preciselyone of the objects of terrorism: thatwe live in fear and under a police state.”“golden eggs” was the very person who in 1914 had made itall possible.Britain’s SIGINT agency, along with MI5 and MI6, isthe third of Britain’s intelligence services. Like them, itshistory is firmly imprinted with the <strong>Churchill</strong> stamp. Itshows that when he kept his assignment with destiny in1940, he was already a veteran of intelligence wars—andI’m passing over, of course, those personal encounters withthe “Great Game” he’d experienced as soldier-journalist onthe North-West frontier of India, in the Sudan, in Cuba,and in South Africa, all of which had made him an ardententhusiast of the shadow war.Intelligence is power: the better, the more effective.<strong>Churchill</strong>, politician that he was, instinctively knew it. Itgave him a weapon of multiple uses. He could deploy itagainst the enemy, as he did so brilliantly in both WorldWars, but it also helped in struggles with friends and allies.One reason he liked “Ultra” was that it put him on an equalfooting with his Chiefs of Staff and gave him a weapon towield against reluctant or recalcitrant Generals. But it wasalso a powerful tool in dealings with allies as well.Roosevelt and Pearl HarborOn Sunday evening, 7 December 1941, <strong>Churchill</strong> wasdining at Chequers with the American ambassador, John G.Winant, and Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s special envoy toMoscow. Shortly after nine o’clock he switched on his wireless,and barely caught an item announcing a Japaneseattack on the Americans. Within minutes he was talking toFranklin Roosevelt on the transatlantic line. The Presidenttold him of the assault on Pearl Harbor and his intention toseek a Congressional declaration of war on Japan.At first stunned by the momentous news, <strong>Churchill</strong>finally grasped its import. Anticipating Germany’s declarationof war on the United States, he concluded that Hitler’sfate was sealed and the war was won. “I went to bed,” herecalled, “and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful.” >>“Intelligence is power: the better, themore effective. <strong>Churchill</strong>, politicianthat he was, instinctively knew it....He could deploy it against theenemy, as he did so brilliantlyin both World Wars,but it also helped in struggleswith friends and allies.”FINEST HOUR 149 / 15

CHURCHILL AND INTELLIGENCE...But did he also dream contentedly of a conspiracycome to fruition? Claims quickly surfaced in the UnitedStates that Roosevelt had deliberately withheld intelligenceof the coming attack in order to silence the isolationists andbring the United States into the war.More recently, voices have suggested that the real PearlHarbor intelligence conspirator was not Roosevelt but<strong>Churchill</strong>. According to this claim, <strong>Churchill</strong>’s astonishedreaction at Chequers was nothing but a carefully constructedcharade that masked the secret of advancedintelligence about Pearl Harbor that he deliberately concealedin order to lure Roosevelt into war. This, argued twoauthors in 1991, one a former wartime codebreaker in theFar East, was the true “betrayal at Pearl Harbor.”Central to this startling conspiracy theory is the claimthat prior to the Japanese strike on Hawaii, British andAmerican codebreakers had broken not only Magic, theJapanese diplomatic cypher, but also the Japanese Navy’soperational cypher, JN-25. The American decrypts had notbeen sent to the White House, according to the conspiracytheorists, but the British ones did reach <strong>Churchill</strong> and forewarnedhim of the attack. In short, this theory not onlyplaces <strong>Churchill</strong> at the heart of an intelligence conspiracy. Itsimultaneously turns Roosevelt into an ignorant dupe.But the theory is fatally flawed. The reason is not that<strong>Churchill</strong> was incapable of manipulating intelligence tomaximise the chances of American participation. He hadalready done so in 1940-41, withholding Ultra intelligencerevealing German postponement of its invasion plans tokeep up pressure on Roosevelt. There are two more cogentreasons. First, the betrayal theory flies in the face of<strong>Churchill</strong>’s own patent desire to win American help. Whywould he deliberately have connived at the destruction ofthe U.S. Pacific Fleet? One reason he desired Americanentry was to protect British Far East interests. It would havemade far more sense, had he possessed advanced intelligence,to have passed it on to the White House. He wouldthus have saved the U.S. fleet and earned Roosevelt’s gratitudein a war that would in any case still have occurred.In fact—the heart of the matter—<strong>Churchill</strong> did nothave advance intelligence about Pearl Harbor. The authors’contention about JN-25 is simply wrong. It is true thatBritish Far East codebreakers had broken the cypher beforePearl Harbor, perhaps as early as 1939. But what the conspiracytheorists omit to note is that JN-25 was supersededby an improved system, JN-25B, in December 1940, andthen again in 1941 by two more successive changes,JN-25B7 and JN-25B8. These new cyphers for all practicalpurposes were unreadable and unproductive of intelligence.Moreover, the Japanese maintained an extremely high levelof security. “The Day of Infamy” was not just an Americanintelligence failure. It was also a brilliant Japanese intelligencesuccess.FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT (1882-1945),President of the United States, 1933-45,encouraged <strong>Churchill</strong> with Lend-Leasewhile Britain stood alone. Conspiracy theoristshave accused him of knowing inadvance of the Pearl Harbor attack, whichwould mean that he was either a fiendishmanipulator of intelligence or criminallyignorant and naive. Neither is true.Pearl Harbor to Teheran:DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER (1890-1969),Supreme Commander Allied Forces inEurope and later 34th President of theUnited States, 1953-61. When GeneralEisenhower arrived in Britain prior to theinvasion of North Africa in 1942, <strong>Churchill</strong>immediately informed him of the existenceof the Ultra code-breaking operations.Photo: Karsh of Ottawa.Of course, the specific claims about JN-25 must bedistinguished from the more general point that British andAmerican intelligence had long been predicting a Japaneseattack, somewhere. The Magic (diplomatic) interceptsunambiguously revealed by late November that Tokyo hadopted for war. But the consensus in London andWashington was that Japan’s most likely target was thePhilippines and South-East Asia.<strong>Churchill</strong> knew a Japanese attack was coming. Everyday personal files of intercepts were sent him from BletchleyPark. They were released to the public only in 1993. Theyreveal that on 6 December, <strong>Churchill</strong> read a telegram fromthe Japanese Foreign Minister in Tokyo to his ambassadorin London, instructing him to destroy all except certain keycodes and burn codes and secret documents. But neitherthis nor any other intercept he read in the forty-eight hoursbefore Pearl Harbor contained any hint of the actual target.Indeed, he was still desperately seeking it up to the lastminute. We know this because Malcolm Kennedy, a FirstWorld War veteran and Japanese linguist, was one of thoseon high alert at Bletchley Park. Against all the rules, he kepta diary that still survives. On December 5th he had been on24-hour duty. The next day, he noted that <strong>Churchill</strong> “is allover himself at the moment for latest information and indicationsre Japan’s intentions and rings up at all hours of theday and night, except for the 4 hours in each 24 (2 to 6pm)when he sleeps.” On December 7th, when Kennedy, like<strong>Churchill</strong>, heard the news of Japan’s attack on the wireless,he recorded his “complete surprise.” If Kennedy, working atBletchley Park, did not know in advance of Pearl Harbor,how would <strong>Churchill</strong>?FINEST HOUR 149 / 16

“<strong>Churchill</strong> exploited intelligence inall its guises as no other politicianbefore him—and certainly moreeffectively than either of his wartimeallies, Josef Stalin and FranklinRoosevelt. He left an indelible markon British intelligence, and theAnglo-American alliance owes morethan history acknowledges to hisfervent support.”CHURCHILL AND INTELLIGENCE...overseas asset. In 1951 Mossadeq nationalised this hatedsymbol of British imperialism and expelled its British technicians.The next year he kicked out all British diplomats.By 1953, London and Washington wanted to get rid ofhim. No one disliked him more than <strong>Churchill</strong>. As FirstLord of the Admiralty WSC had played a leading role innegotiating the Anglo-Iranian oil deal in the first place. Inprivate he mocked Mossadeq as “Mussy Duck.”The second actor was the head of the SIS in Iran, theHonourable “Monty” Woodhouse, later Tory MP forOxford. But he was more than that. In the Second WorldWar he’d been one of those brave young warriors fightingbehind enemy lines—in his case Greece, close to his and<strong>Churchill</strong>’s heart. In 1942 he’d helped blow up theGorgopotamos Viaduct carrying vital German supplies toNorth Africa. In 1944 he, too, had received a summons toChequers, where <strong>Churchill</strong> had taken a shine to him.Something else had happened while Woodhouse wasin England. Lunching with Anthony Eden, a fellow guestwas an attractive war widow named Davina Lytton. She wasthe daughter of the young woman who fifty years beforehad stunningly captured <strong>Churchill</strong>’s heart in India, PamelaPlowden. Romance again flourished, and Davina andMonty were soon married. “Our man in Teheran” had apersonal link with <strong>Churchill</strong>.The final actor was also well known to <strong>Churchill</strong> andhad a name resonant in the United States. Kermit Rooseveltwas a grandson to Theodore and cousin to Franklin. Heand <strong>Churchill</strong> had met at the White House Christmas partyin December 1941, and since then he’d risen high in theCIA. Now he was its field commander in Iran.The SIS and CIA concocted a joint plan to toppleMossadeq in a coup. In July 1953 Kermit Roosevelt secretlyentered Iran and, in several clandestine nighttime encounterswith the Shah worthy of any thriller, persuaded him tocooperate. In London, Woodhouse had several meetingswith <strong>Churchill</strong>. When a hesitant Anthony Eden, theForeign Secretary, fell sick, <strong>Churchill</strong> took over and gave thegreen light to the plot. In August, Teheran was convulsed incarefully-prepared rent-a-crowd riots and Mossadeq wasduly deposed.A week later a triumphant Kermit Roosevelt arrived atHeathrow Airport en route for Washington. SIS top brassgave him a splendid lunch at the Connaught Hotel beforehis final appointment of the day: Ten Downing Street.Characteristically defying his medical advisers, <strong>Churchill</strong>had soldiered on since his stroke in June. Events in Teheranhad gripped his imagination. Learning that Roosevelt was inLondon, he demanded a personal account.At precisely 4 o’clock, Roosevelt rang the doorbell andwas ushered in by a military aide. Downstairs, in a receptionroom converted into a bedroom, he found the PrimeMinister, lying in bed propped up by pillows. <strong>Churchill</strong>grunted a greeting, and Roosevelt sat down beside him. Thetwo men began with small talk and exchanged reminiscencesabout the White House Christmas Party. ThenRoosevelt launched on his tale, presenting the dramatichighlights in considerable detail. <strong>Churchill</strong> frequently interruptedwith questions and from time to time would dozeoff for a few moments, only to awake and grill theAmerican on a point of detail. For a full two hours the twomen talked.When Roosevelt had completed his account,<strong>Churchill</strong> grinned and shifted himself up on his pillows.“Young man,” he said, “if I had been but a few yearsyounger, I would have loved nothing better than to haveserved under your command in this great venture!”With this telling vignette I must take my leave of<strong>Churchill</strong>. A warrior to the end, he’d exploitedintelligence in all its guises as no other politicianbefore him—and certainly more effectively than eitherof his wartime allies, Josef Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt. Heleft an indelible mark on British intelligence, which servedhim well both in peace and war during his fifty year politicalcareer. The Anglo-American intelligence alliance thatendures to this day owes more than history acknowledges tohis fervent support.The quest to understand the protean figure of<strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> grows, not diminishes, with the passageof time. As we peel away the layers of historical varnish, theportrait becomes ever richer and more complex. His adventuresin the secret world of intelligence make him an evenmore intriguing figure than we thought. ,FINEST HOUR 149 / 18

R I D D L E S , M Y S T E R I E S , E N I G M A SHarvie-Watt: Behind Closed DoorsWhile visiting the secret War Rooms and <strong>Churchill</strong> Museum in London,Qxwe saw the rooms occupied by <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong>’s staff and assistants.The doors were open so that visitors could see where the people worked andslept during the Blitz. But there was one exception: a closed door under a signreading, “General Harvie-Watt.” Is there a reason for this? I understand thatHarvie-Watt was a personal assistant to <strong>Churchill</strong>, and influential, yet I foundno reference to him in the museum. —ADRIAN LOTHERINGTONAPhil Reed, director of the WarRooms, advises that Harvie-Watt’sroom has never been open since thearea was refurbished in 2003. Althoughsome rooms were restored to theirwartime appearance, space limitationsprevented more. The room housescomputer service equipment.George Harvie-Watt (1903-1989) was Conservative MP forKeighley, 1931-35, and for Richmond,Surrey, 1937-59. He was educated atGeorge Watson’s College, Edinburgh,then at the University of Glasgow andthe University of Edinburgh. He wascommissioned into the TerritorialArmy Royal Engineers in 1924 andbecame a barrister at Inner Temple in1930. In 1941-45 he was WSC’sParliamentary Private Secretary, so hewould certainly be entitled to a roomin the bunker.Harvie-Watt became a LieutenantColonel in the Territorial Army in1938 and was promoted to Brigadier in1941—hence the “General” title. Manycopies of his memoirs, Most of My Life(London: Springwood, 1980) are availableon bookfinder.com. There areseveral mentions of him in JockColville’s memoirs, The <strong>Churchill</strong>iansand Fringes of Power, and of course hecomes up in Sir Martin Gilbert’s officialbiography, <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>.In Volume VI, 828-29, is anamusing account from autumn 1940,when Harvie-Watt was commandingan anti-aircraft unit during a visit by<strong>Churchill</strong> and General Pile, whichhelps explain why WSC later madehim his PPS—and why <strong>Churchill</strong> wasable to imbibe so many whiskies—henever drank them neat!....As they arrived, Pile told Harvie-Wattthat <strong>Churchill</strong> was “frozen and in aHARVIE-WATT from the jacket of hismemoir, Most of My Life. Below: with<strong>Churchill</strong> and Inspector Thompson onV-E Day, London, 8 May 1945.bad temper” and suggested that thePrime Minister be brought “a strongwhisky and soda.” Harvie-Watt sent adespatch rider to find one.“Meanwhile,” he later recalled, “everythingwas going from bad to worse.The field was almost waterlogged andthe rain poured down. Everything Itried to show the Prime Minister hehad seen before.” The searchlightSend your questions to the editorcontrol radar set, which hadworked on the previousnight, failed to function.A few days earlier it had beenannounced that because of illhealth,Chamberlain wouldresign as Leader of the ConservativeParty. The question being muchdebated was whether or not <strong>Churchill</strong>should succeed Chamberlain as Leader.“I said it would be fatal if he did notlead the Conservative Party,” Harvie-Watt recalled, “as the bulk of the partywas anxious that he should be theLeader now we were at war.”<strong>Churchill</strong>, however, “was still suspiciousof [the Conservatives] and oftheir attitude to him before the war. Isaid it was only a small section of theparty that took that line and that themass of the party was with him. Mystrongest argument, however, and I feltthis very much, was that it was essentialfor the PM to have his ownparty—a strong one with alliesattracted from the main groups andespecially the Opposition parties. Butessentially he must have a majority andI was sure this majority could onlycome from the Conservative Party.”Not wishing to miss an opportunity ofadvice from a member of the WhipsOffice, <strong>Churchill</strong> questioned Harvie-Watt about “the strength of Ministersand what influence they wielded.”Harvie-Watt replied: “If you have astrong army of MPs under you,Ministers would be won over orcrushed, if necessary.” <strong>Churchill</strong>, henoted, “seemed to appreciate my argumentsand thanked me very much.Then he began to feel the cold againand agitated to get away.”At this moment the despatch riderarrived with the whisky, and Harvie-Wattpoured one for the freezing PrimeMinister. <strong>Churchill</strong> swallowed a halftumbler,then cried out at the taste of theneat whisky: “You have poisoned me.”<strong>Churchill</strong> did not nurse a bottle,as an alcoholic would, and occasionallyremarked to those who took whiskyneat, “you are not likely to live a longlife if you drink it like that.” Perhapsthis is more than you wanted to knowabout George Harvie-Watt. ,FINEST HOUR 149 / 19

C H U R C H I L L A N D I N T E L L I G E N C EGolden Eggs: The Secret War, 1940-1945Part I: Britain and America<strong>Churchill</strong> used secret intelligence on a global scale, freely shared it with the Americans, andmade it count in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Cabinet’s unanimous decision to aid Greecein 1941 would not have been made were it not for the Enigma decrypts.M A R T I N G I L B E R TCOLOSSUS: the world’s first electronic, programmable computer, above,was vital in the preparation of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s “Golden Eggs.” Commencing in1994, a team led by Tony Sale began reconstruction of a Colossus atBletchley Park. Right: Mr. Sale supervises the breaking of an encypheredmessage with the completed machine. (MaltaGC/Wikimedia)<strong>Churchill</strong> became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940.Twelve days later, on 22 May, the codebreakers atBletchley Park broke the Enigma key most frequentlyused by the German Air Force. This was the hourlytwo-way top-secret radio traffic between the combinedGerman Army, Navy and Air Force headquarters at Zossenand the commanders-in-chief on the battlefronts.Included in the newly broken key were the top-secretmessages of German Air Force liaison officers with theGerman Army. The daily instructions of these liaison officersincluded targets, supply and, crucially, details ofshortages such as aviation fuel.In the desperate days of late May and early June1940—when the British Expeditionary Force was beingevacuated from Dunkirk—daily decrypts indicated the positionand intentions of the German field formations as theyturned towards the sea. Even with delays in decrypting individualEnigma messages taking, at that time, up to six days,this was an indispensable benefit in guiding the continuationof the evacuation to the last possible moment.As the German air Blitz on Britain intensified inAugust and September 1940, fears of invasion mounted.On 11 September <strong>Churchill</strong> received details of an Enigmadecrypt that suggested that invasion plans were being made._______________________________________________________________________________________________________The Rt. Hon. Sir Martin Gilbert CBE was named the official biographer of Sir <strong>Winston</strong> <strong>Churchill</strong> following the death of Randolph <strong>Churchill</strong>in 1968, and has now published almost as many words on his subject as <strong>Churchill</strong> himself. “Official” is something of a misnomer, sincehe was never told what to write or what position to take on any aspect of the story. <strong>Winston</strong> S. <strong>Churchill</strong>, with eight narrative volumesand sixteen companion or document volumes, and more to come, is the longest biography ever published. It is now being reprinted infull by Hillsdale College Press, which offers all volumes so far published at affordable prices. See: http://www.hillsdale.edu/news/freedomlibrary/churchill.asp.Sir Martin is an honorary member of The <strong>Churchill</strong> Centre and has been a contributor to Finest Hour for nearlythirty years. For further information see http://www.martingilbert.com.FINEST HOUR 149 / 20

British Military Intelligence commented on this decrypt:“Although there are a number of possible reasons forthis order, it cannot be overlooked that it may be in connectionwith the movement of troops and armament forinvasion purposes.” 1Throughout the autumn and winter of 1940, thesearch for indications of a German invasion remained thetop priority of the Bletchley eavesdroppers. On 10 October1940, <strong>Churchill</strong> was shown summaries of decrypts ofGerman Air Force top-secret signals that had revealed,among other German instructions, the appointment in thefirst week of October of German Air Force officers to theembarkation staffs at Antwerp, Ostend, Dunkirk andCalais, where air reconnaissance—another indispensablearm of Intelligence—revealed the presence of what couldwould well have been invasion barges.Top-secret instructions had also been decrypted atBletchley with regard to a German air formation headquarters,which was known to be in charge of German Air Forceequipment in Belgium and Northern France, “settling thedetails of loading of units and equipment into ships.” On24 September 1940 the German Third Air Fleet receivedorders, also decrypted at Bletchley, concerning the supply ofair/sea rescue vessels by seaplane bases off Norway and alongthe North Sea and Channel coasts “in connection,” as themessage sent to <strong>Churchill</strong> explained, “with the Seelöwe (SeaLion) operation,” presumed to be the invasion of Britain.On 9 October 1940 a further decrypt revealed that onthe previous day the headquarters of the Second GermanAir Fleet “asked for provision of two tankers each filled withapproximately 250,000 gallons of aviation fuel to be held inreadiness for S+3 day (presumably the third day of invasionoperations against UK) at Rotterdam and Antwerp.” 2It was not until 12 January 1941 that <strong>Churchill</strong>received the details of an Enigma decrypt that German AirForce wireless stations on the circuit of the air formationheadquarters responsible for German Air Force equipmentin Belgium and Northern France—equipment that wasknown to have been on standby for invasion duties—was“no longer to be manned as from January 10.” 3The danger of invasion was over. Other decrypts werenow making it clear that the new German focus of militaryand air preparations was against its ally and partner of theprevious sixteen months, the Soviet Union. 4<strong>Churchill</strong>’s VigilanceAs Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, <strong>Churchill</strong>was intensely concerned with maintaining the secrecy of allaspects of war policy and planning. In no area was secrecymore important to him than with regard to Enigma.On 16 October 1940 he wrote to General Ismay, headof his Defence Office: “I am astounded at the vast congregationwho are invited to study these matters. The AirMinistry is the worst offender and I have marked a numberwho should be struck off at once, unless after careful considerationin each individual case it is found to beindispensable that they should be informed. I have addedthe First Lord, who of course must know everything knownto his subordinates, and also the Secretary of State for War.”<strong>Churchill</strong> continued: “A machinery should be constructedwhich makes other parties acquainted with suchinformation as is necessary to them for the discharge of theirparticular duties. I await your proposals. I should also addCommander-in-Chief Fighter and Commander-in-ChiefBomber Command, it being clearly understood that theyshall not impart them to any person working under them orallow the boxes to be opened by anyone save themselves.” 5Within three weeks of <strong>Churchill</strong>’s minute to Ismay,the number of recipients of Enigma-based material hadbeen fixed at thirty-one.<strong>Churchill</strong>’s vigilance was continual. In September1941, on reading the wide circulation given to a 7 a.m.summary of a series of decrypts giving the movement ofGerman fuel ships in the Mediterranean between Naplesand the North African port of Bardia, he wrote to BrigadierStewart Menzies, Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service(MI6), and to the Army and Navy Chiefs of Staff: “Surelythis is a dangerously large circulation. Why sh[oul]d anyonebe told but the 3 C-in-Cs. They can give orders withoutgiving reasons. Why should such messages go to subsidiaryHQs in the Western Desert.” 6When <strong>Churchill</strong> travelled outside London and overseas,the summaries and assessments of Enigma decryptswere sent on to him by courier or top-secret radio signal. >>“When <strong>Churchill</strong> travelled outside London and overseas, the summaries andassessments of Enigma decrypts were sent on to him by courier or top-secret radiosignal. When he was in Britain, translated summaries of the decrypts, and theBletchley assessments, were sent him in locked buff-coloured boxes to which healone had the key. None of his Private Office knew what the contents were.”FINEST HOUR 149 / 21

GOLDEN EGGS...When he was in Britain, translated summaries of thedecrypts, and the Bletchley assessments, were sent him inlocked buff-coloured boxes to which he alone had the key.None of his Private Office knew what the contents were. Ashis Junior Private Secretary, John Colville, noted in his diaryat Chequers in May 1941: “The PM, tempted by thewarmth, sat in the garden working and glancing at me withsuspicion from time to time in the (unwarranted) belief thatI was trying to read the contents of his special buff boxes.” 7<strong>Churchill</strong> made his first visit to Bletchley on 6September 1941. His Principal Private Secretary, JohnMartin, who accompanied him in the car on their way toOxfordshire for the weekend, did not enter the building,and had no idea what went on there. 8Following his visit to Bletchley, <strong>Churchill</strong> received aletter, dated 21 October 1941, from four Bletchley cryptographers,Gordon Welchman, Stuart Milner-Barry, AlanTuring and Hugh O’D. Alexander. In their letter, theyurged <strong>Churchill</strong> to authorize greater funding for the workthey were doing. Manual decoding was extremely time-consuming.Turing believed that a machine he haddevised—the “bombe,” then in its early days—could speedup the task considerably, but that more funding and morestaff were needed. Milner-Barry later explained: “The cryptographerswere hanging on to a number of keys by theircoattails and if we had lost any or all of them there wasno guarantee (given the importance of continuity inbreaking) that we should ever have found ourselves in businessagain.” 9In view of the exceptional secrecy, Milner-Barry tookthe letter by hand to 10 Downing Street. He later reflected:“The thought of going straight from the bottom to the topwould have filled my later self with horror and incredulity.”On receipt of the letter, <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote to the head of hisDefence Office, General Ismay (his letter marked “ActionThis Day”): “Make sure they have all they want on extremepriority and report to me that this has been done.” 10“Almost from that day,” Milner-Barry recalled, “therough ways began to be made smooth. The flow of bombeswas speeded up, the staff bottlenecks relieved, and we wereable to devote ourselves uninterruptedly to the business inhand.” Brigadier Menzies—who rebuked GordonWelchman when they met for having “wasted fifteenminutes” of the Prime Minister’s time—reported to<strong>Churchill</strong> on November 18th that every possible measurewas being taken. Bletchley’s needs were met.<strong>Churchill</strong>, fully aware of the crucial role of BletchleyPark in averting defeat—and in due course, if all went wellon the battlefield, to secure victory—had ensured that fundswould be made available to improve the bombe, which wasdecisively to accelerate the decrypting of Enigma messages.In the second week of March 1943, Enigma decryptsof German dispositions in the Mediterranean disclosed thatfour merchant vessels and a tanker, whose cargoes weredescribed by Field Marshal Kesselring as “decisive for thefuture conduct of operations” in North Africa, would sailfor Tunisia on March 12th and 13th, in two convoys.Alerted by this decrypt, British air and naval forcessank the tanker and two of the merchant ships.Unfortunately, before despatching the interceptingforce, the British planners of the operation failed to providesufficient alternative sightings, so as to protect the Enigmasource. An Enigma decrypt on March 14th made it clearthat the suspicions of the German Air Force had beenaroused, and that a breach of security was being blamed forthe loss of the vital cargoes. <strong>Churchill</strong>, reading this decrypt,minuted at once that the Enigma should be withheld unlessit was “used only on great occasions or when thoroughlycamouflaged.” 11Fortunately for Britain, the Germans did not suspectthat their Enigma secret was the cause of this apparentbreach of their security. Nor did the Germans manage tobreak into Britain’s own Signals Intelligence system. Hadthey done so, they would have learned at once that Enigmahad been compromised.What to Tell the Americans?Following the visit to Britain of President Roosevelt’semissary Harry Hopkins, in January 1941, <strong>Churchill</strong> agreedthat the United States could share information concerningEnigma, and could do so without delay. In February 1941the Currier-Sinkov mission from the United States broughta Japanese Foreign Office “Purple” cypher machine andother codebreaking items to Bletchley, where ColonelTiltman’s solutions of Japanese army code systems, whichhe explained to the American cryptographers during theirvisit, represented the first solutions of Japanese army materialthat United States cryptanalysts had seen. 12In his own reading of Enigma, <strong>Churchill</strong> was alwayson the lookout for items that he felt should be sent toRoosevelt. Especially with Enigma decrypts and interpretationsthat related to the Far East and the Pacific, he wouldnote for Brigadier Menzies: “Make sure the President knowsthis” or “make sure the President sees this.” 13In April 1942, four months after the Japanese attackon Pearl Harbor, <strong>Churchill</strong> authorized the visit by ColonelTiltman to OP-20-G, the United States Navy’s cryptanalyticoffice in Washington DC. 14 During Tiltman’s visit itbecame clear that the United States Navy wanted to attackthe German naval “Shark” key, against which Bletchley hadmade almost no progress since the introduction of the fourrotorEnigma (M4) on 1 February 1942: this Shark keyprovided the German Navy with all top-secret communicationswith its submarines.On 8 February 1942, <strong>Churchill</strong> wrote to Menzies:“Do the Americans know anything about our machine? Letme know by tomorrow afternoon.” Colonel Menzies repliedFINEST HOUR 149 / 22