Peacekeeping without Accountability - Yale Law School

Peacekeeping without Accountability - Yale Law School

Peacekeeping without Accountability - Yale Law School

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

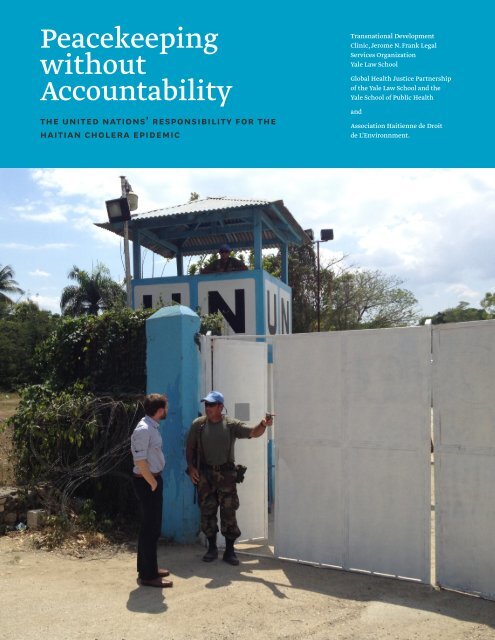

<strong>Peacekeeping</strong><strong>without</strong><strong>Accountability</strong>The United Nations’ Responsibility for theHaitian Cholera EpidemicTransnational DevelopmentClinic, Jerome N. Frank LegalServices Organization<strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong>Global Health Justice Partnershipof the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> and the<strong>Yale</strong> <strong>School</strong> of Public HealthandAssociation Haitienne de Droitde L’Environnment.1 section

The Transnational Development Clinic is a legal clinic, part of the Jerome N.Frank Legal Services Organization at the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong>. The clinic works on arange of litigation and non-litigation projects designed to promote communitycenteredinternational development, with an emphasis on global poverty. Theclinic works with community-based clients and client groups and provides themwith legal advice, counseling, and representation in order to promote specificdevelopment projects. The clinic also focuses on development projects that havea meaningful nexus to the U.S., in terms of client populations, litigation oradvocacy forum, or applicable legal or regulatory framework.The Global Health Justice Partnership (GHJP) is a joint program of the <strong>Yale</strong><strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> and the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>School</strong> of Public Health, designed to promote research,projects, and academic exchanges in the areas of law, global health, and humanrights. The GHJP has undertaken projects related to intellectual property andaccess to medicines, reproductive rights and maternal health, sexual orientationand gender identity, and occupational health. The partnership engages studentsand faculty through a clinic course, a lunch series, symposia, policy dialogues,and other events. The partnership works collaboratively with academics,activists, lawyers, and other practitioners across the globe and welcomes manyof them as visitors for short- and long-term visits at <strong>Yale</strong>.Copyright © 2013,Transnational DevelopmentClinic, Jerome N. Frank LegalServices Organization, <strong>Yale</strong><strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong>, Global HealthJustice Partnership of the<strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> and the <strong>Yale</strong><strong>School</strong> of Public Health,and Association Haitiennede Droit de L’Environnment.All rights reserved.Printed in the UnitedStates of AmericaReport design byJessica SvendsenCover photograph was takenoutside the MINUSTAH basein Méyè in March of 2013,during the research team’svisit to Haiti.L’Association Haïtienne de Droit de l’Environnement (AHDEN) is a non-profitorganization of Haitian lawyers and jurists with scientific training. Theorganization’s mission is to help underprivileged Haitians living in rural areasfight poverty through the defense and promotion of environmental and humanrights. These rights are in a critical condition in places like Haiti where ruralcommunities have limited access to education and justice.

ContentsIIIAcknowledgementsGlossary6 Executive Summary10 Summary of Recommendations11 Methodology13 chapter IMINUSTAH and the Cholera Outbreak in Haiti22 chapter IIScientific Investigations Identify MINUSTAHTroops as the Source of the Cholera Epidemic33 chapter IIIThe Requirement of a Claims Commission39 chapter IVThe U.N. Has Failed to Respect Its InternationalHuman Rights Obligations47 chapter VThe U.N.’s Actions Violated Principles andStandards of Humanitarian Relief54 chapter VIRemedies and Recommendations62 Endnotes

AcknowledgmentsThis report was written by Rosalyn Chan MD,MPH, Tassity Johnson, Charanya Krishnaswami,Samuel Oliker-Friedland, and Celso PerezCarballo, student members of the TransnationalDevelopment Clinic (a part of the Jerome N. FrankLegal Services Organization) and the Global HealthJustice Partnership of the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> and the<strong>Yale</strong> <strong>School</strong> of Public Health, in collaboration withAssociation Haitienne de Droit de L’Environnment(AHDEN). The project was supervised by ProfessorMuneer Ahmad, Professor Ali Miller, and SeniorSchell Visiting Human Rights Fellow Troy Elder.Professor James Silk also assisted with supervision.Jane Chong, Hyun Gyo (Claire) Chung, and PaigeWilson, also students in the TransnationalDevelopment Clinic, provided research andlogistical support.The final draft of the report incorporatescomments and feedback from discussions withrepresentatives from: AHDEN, Association desUniversitaires Motivés pour une Haiti de Droits(AUMOHD), Bureau des Avocats Internationaux(BAI), U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC),Collectif de Mobilisation Pour Dedommager LesVictimes du Cholera (Kolektif), Direction Nationalede l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement (DINEPA),Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF); Partners inHealth (PIH), and the United States Agency forInternational Development (USAID). The authorsalso wish to thank the residents of Méyè, Haiti whowere directly affected by the cholera epidemic forsharing their experiences with the authors duringtheir visit to Méyè.The report has benefited from the close reviewand recommendations of Professor Jean-AndrèVictor of AHDEN and Albert Icksang Ko, MD, MPH,Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health at the<strong>Yale</strong> University <strong>School</strong> of Medicine. The authors aregrateful for their time and engagement.The authors would like to thank <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong><strong>School</strong> and the Robina Foundation for theirgenerosity in funding this project.Finally, the authors thank the followingorganizations and individuals for sharing their timeand wisdom with the team: Joseph Amon, Directorof Health and Human Rights at Human RightsWatch; Dyliet Jean Baptiste, Attorney at BAI; Jean-Marie Celidor, Attorney at AHDEN; Paul ChristianNamphy, Coordinator at DINEPA; Karl “Tom”Dannenbaum, Research Scholar in <strong>Law</strong> and RobinaFoundation Human Rights Fellow at <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong><strong>School</strong>; Melissa Etheart, MD, MPH, Cholera MedicalSpecialist, CDC; Evel Fanfan, Attorney and Presidentof AUMOHD; Jacceus Joseph, Attorney and Authorof La MINUSTAH et le cholera; Olivia Gayraud, Head ofMission in Port-au-Prince at MSF; Yves-Pierre Louisof Kolektif; Alison Lutz, Haiti Program Coordinatorat PIH; Duncan Mclean, Desk Manager at MSF;Nicole Phillips, Attorney at Institute for Justiceand Democracy in Haiti ; Leslie Roberts, MPH,Clinical Professor of Population and Family Healthat the Columbia University Mailman <strong>School</strong> ofPublic Health; Margaret Satterthwaite, Professor ofClinical <strong>Law</strong> at New York University <strong>School</strong> of <strong>Law</strong>;Scott Sheeran, Director of the LLM in InternationalHuman Rights <strong>Law</strong> and Humanitarian <strong>Law</strong> at theUniversity of Essex; Deborah Sontag, InvestigativeReporter at the New York Times; Chris Ward,Housing and Urban Development Advisor at USAID;and Ron Waldman, MD, MPH, Professor of GlobalHealth in the Department of Global Health atGeorge Washington University. The authors are alsograteful for the assistance of Maureen Furtak andCarroll Lucht for helping coordinate travel to Haiti.While the authors are grateful to all of theindividuals and organizations listed above,the conclusions drawn in this report representthe independent analysis of the TransnationalDevelopment Clinic, the Global Justice HealthPartnership, and AHDEN, based solely on theirresearch and fieldwork in Haiti.Iacknowledgments

Glossary of Acronyms and AbbreviationsCDCCEDAWCERDCRCCRPDCTCDINEPAGeneral ConventionIACHRICESCRICJICRCIDPHAPHRCICCPRLNSPMINUSTAHMSFMSPPNGOPAHOSOFAUDHRU.N.UNCCCenters for Disease ControlConvention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against WomenInternational Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial DiscriminationConvention on the Rights of the ChildConvention on the Rights of Persons with DisabilitiesCholera Treatment CenterHaitian National Directorate for Water Supply and SanitationConvention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United NationsInter-American Commission on Human RightsInternational Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural RightsInternational Court of JusticeInternational Committee of the Red CrossInternally Displaced PersonHumanitarian <strong>Accountability</strong> PartnershipHuman Rights CommissionInternational Convention on Civil and Political RightsHaitian National Public Health LaboratoryU.N. Stabilization Mission in Haiti (Mission des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisationen Haïti)Médecin Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders)Haitian Ministry of Health (Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population)Non-Governmental OrganizationPan-American Health OrganizationStatus of Forces AgreementUniversal Declaration of Human RightsUnited NationsV. cholerae Vibrio choleraeVCFWHOUnited Nations Compensation Commission in IraqSeptember 11th Victims Compensation FundWorld Health OrganizationIIglossary

Executive SummaryThis report addresses the responsibility of the United Nations (U.N.) for the choleraepidemic in Haiti—one of the largest cholera epidemics in modern history. The reportprovides a comprehensive analysis of the evidence that the U.N. brought cholerato Haiti, relevant international legal and humanitarian standards necessary tounderstand U.N. accountability, and steps that the U.N. and other key national andinternational actors must take to rectify this harm. Despite overwhelming evidencelinking the U.N. Mission for the Stabilization in Haiti (MINUSTAH) 1 to the outbreak, theU.N. has denied responsibility for causing the epidemic. The organization has refusedto adjudicate legal claims from cholera victims or to otherwise remedy the harmsthey have suffered. By causing the epidemic and then refusing to provide redress tothose affected, the U.N. has breached its commitments to the Government of Haiti, itsobligations under international law, and principles of humanitarian relief. Now, nearlyfour years after the epidemic began, the U.N. is leading efforts to eliminate cholera buthas still not taken responsibility for its own actions. As new infections continue tomount, accountability for the U.N.’s failures in Haiti is as important as ever.The Cholera Epidemic in Haiti and U.N.<strong>Accountability</strong>: BackgroundIn October 2010, only months after the countrywas devastated by a massive earthquake, Haiti wasafflicted with another human tragedy: the outbreakof a cholera epidemic, now the largest in the world,which has killed over 8,000 people, sickened morethan 600,000, and promises new infections for adecade or more. Tragically, the cholera outbreak—the first in modern Haitian history—was causedby United Nations peacekeeping troops whoinadvertently carried the disease from Nepal tothe Haitian town of Méyè. In October 2010, theU.N. deployed peacekeeping troops from Nepal tojoin MINUSTAH in Haiti. The U.N. stationed thesetroops at an outpost near Méyè, approximately 40kilometers northeast of Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince. The Méyè base was just a few meters froma tributary of the Artibonite River, the largestriver in Haiti and one the country’s main sourcesof water for drinking, cooking, and bathing.Peacekeepers from Nepal, where cholera is endemic,arrived in Haiti shortly after a major outbreakof the disease occurred in their home country.Sanitation infrastructure at their base in Méyèwas haphazardly constructed, and as a result,sewage from the base contaminated the nearbytributary. Less than a month after the arrival ofthe U.N. troops from Nepal, the Haitian Ministry ofPublic Health reported the first cases of cholera justdownstream from the MINUSTAH camp.Cholera spread as Haitians drank contaminatedwater and ate contaminated food; the country’salready weak and over-burdened sanitary systemonly exacerbated transmission of the diseaseamong Haitians. In less than two weeks after theinitial cases were reported, cholera had alreadyspread throughout central Haiti. During the first30 days of the epidemic, nearly 2,000 people died.By early November 2010, health officials recordedover 7,000 cases of infection. By July 2011, cholerawas infecting one new person per minute, and thetotal number of Haitians infected with cholerasurpassed the combined infected population ofthe rest of the world. The epidemic continued toravage the country throughout 2012, worsenedby Hurricane Sandy’s heavy rains and flooding1 executive summary

in October 2012. In the spring of 2013, with thecoming of the rainy season, Haiti has once moresaw a spike in new infections.Haitian and international non-governmentalorganizations have called on the U.N. to acceptresponsibility for causing the outbreak, but to datethe U.N. has refused to do so. In November 2011,Haitian and U.S. human rights organizations fileda complaint with the U.N. on behalf of over 5,000victims of the epidemic, alleging that the U.N.was responsible for the outbreak and demandingreparations for victims. The U.N. did not respondfor over a year, and in February 2013, invoking theConvention on Privileges and Immunities of theUnited Nations, summarily dismissed the victims’claims. Relying on its organizational immunityfrom suit, the U.N. refused to address the merits ofthe complaint or the factual question of how theepidemic started.Summary of the MethodologyResearch, writing, and editing for this report wascarried out by a team of students and professorsfrom the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>Law</strong> <strong>School</strong> and the <strong>Yale</strong> <strong>School</strong> ofPublic Health. Desk research draws from primaryand secondary sources, including official U.N.documents, international treatises, news accounts,epidemiological studies and investigations, andother scholarly research in international lawand international humanitarian affairs. Over aone year period, student authors also conductedextensive consultations with Haitians affected bythe epidemic, as well as national and internationaljournalists, medical doctors, advocates, governmentofficials, and other legal professionals with firsthandexperience in the epidemic and its aftermath.In March 2013, students and faculty traveled toHaiti to carry out additional investigations. Theyconsulted stakeholders and key informants in boththe Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince and near theMINUSTAH Méyè base where the outbreak started.The <strong>Yale</strong> student and faculty team presentedstakeholders in and outside of Haiti with a draftsummary and outline of the report for review,discussion and comment. The final draft of thereport incorporates comments and feedback fromall of these consultations.Summary of FindingsThis report provides the first comprehensiveanalysis of not only the origins of the choleraoutbreak in Haiti, but also the U.N.’s legal andhumanitarian obligations in light of the outbreakand the steps the U.N. must take to remediate thisongoing humanitarian disaster. This analysis hasconcluded the following:1 The cholera epidemic in Haiti is directly traceableto MINUSTAH peacekeepers and the inadequatewaste infrastructure at their base in Méyè.2 The U.N.’s refusal to establish a claimscommission for the victims of the epidemicviolates its contractual obligation to Haiti underinternational law.3 By introducing cholera into Haiti and denyingany form of remedy to victims of the epidemic,the U.N. has failed to uphold its duties underinternational human rights law.4 The U.N.’s introduction of cholera into Haitiand refusal to accept responsibility for doingso has violated principles of internationalhumanitarian aid.Chapter I examines the legal and political statusof MINUSTAH before and during the epidemic, aswell as the U.N.’s official response to the outbreak.From its establishment in 2004, MINUSTAH hasbeen charged with a broad mandate encompassingpeacekeeping, the re-establishment of the rule oflaw, the protection of human rights, and social andeconomic development. Moreover, following theJanuary 12, 2010 earthquake, MINUSTAH troopsalso assisted in humanitarian recovery effortsin Haiti. After cholera broke out in October 2010,a number of independent studies and clinicalinvestigations pointed to the MINUSTAH basein Méyè as the source of the epidemic. Choleravictims and their advocates have subsequentlycalled on the U.N. for reparations to remedy thesituation and requested meaningful accountabilitymechanisms to review claims, to no avail.Meanwhile, the national and international2 executive summary

esponse to the epidemic has been underfundedand incomplete.In the years following the outbreak, the U.N.has denied responsibility for the epidemic. TheU.N. has repeatedly relied on a 2011 study by a U.N.Independent Panel of Experts, which concludedthat at the time there was no clear scientificconsensus regarding the cause of the epidemic.However, these experts have since revised theirinitial conclusions. In a recent statement, theyunequivocally stated that new scientific evidencedoes point to MINUSTAH troops as the cause of theoutbreak. As Chapter II of this report establishes,epidemiological studies of the outbreak linkingthe outbreak to the MINUSTAH base in Méyèbelie the U.N.’s claims. Four key findings confirmthat MINUSTAH peacekeeping troops introducedcholera into the country. First, doctors observedno active transmission of symptomatic cholera inHaiti prior to the arrival of the MINUSTAH troopsfrom Nepal. Second, the area initially affectedby the epidemic encompassed the location ofthe MINUSTAH base. Third, the troops at theMINUSTAH base were exposed to cholera in Nepal,and their feces contaminated the water supplynear the base. Finally, the outbreak in Haiti istraceable to a single South Asian cholera strainfrom Nepal. No compelling alternative hypothesisof the epidemic’s origins has been proposed.As Chapter III details, in refusing to provide aforum to address the grievances of victims of thecholera epidemic, despite clear scientific evidencetracing the epidemic to the MINUSTAH camp’sinadequate waste infrastructure, the U.N. violatesits obligations under international law. According tothe U.N. Charter and the Convention on Privilegesand Immunities of the U.N., the U.N. is immunefrom suit in most national and internationaljurisdictions. Because of this legal immunity,the U.N. must provide to third parties certainmechanisms for holding it accountable if and whenit engages in wrongdoing during peacekeepingoperations—an obligation the U.N. Secretary-General has publicly recognized. In a series ofreports submitted to the General Assembly in thelate 1990s, the Secretary-General explained thatthe U.N. has an international responsibility for theactivities of U.N. peacekeepers. This responsibilityincludes liability for damage caused by peacekeepersduring the performance of their duties.The U.N. historically has addressed the scopeof its liability in peacekeeping operations throughStatus of Forces Agreements (SOFAs) signed withhost countries. The Haitian government signedsuch an agreement with MINUSTAH in 2004. Inthis SOFA, the U.N. explicitly promises to create astanding commission to review third party claimsof a private law character—meaning claims relatedto torts or contracts—arising from peacekeepingoperations. Despite its obligations under the SOFA,the U.N. has not established a claims commission inHaiti. In fact, the U.N. has promised similar claimscommissions in over 30 SOFAs since 1990. To date,however, the organization has not established asingle commission, leaving countless victims ofpeacekeeper wrongdoing <strong>without</strong> any remedy at law.The U.N.’s refusal to establish a claims commissionnot only violates the terms of its own contractualagreement with Haiti; it also defies the organization’sresponsibilities under international humanrights law. As Chapter IV explains, the U.N.’s foundingdocuments require that the U.N. respect internationallaw, including international human rightslaw, and promote global respect for human rights. Inaddition, the SOFA requires that MINUSTAH observeall local laws, which include Haiti’s obligations toits citizens under international human rights law.International human rights law guarantees accessto clean water and the prevention and treatment ofinfectious disease, forbids arbitrary deprivation oflife, and ensures that when a person’s human rightsare not respected, he or she may seek reparation forthat harm. By failing to prevent MINUSTAH fromintroducing cholera into a major Haitian watersystem and subsequently denying any remedy to thevictims of the epidemic it caused, the U.N. failed torespect its victims’ human rights to water, health,life, and an effective remedy. Furthermore, giventhe U.N.’s role as a leader in the development, promotion,and protection of international human rightslaw, it risks losing its moral ground by refusing tocomply with the very law it demands states andother international actors respect.The U.N.’s role in introducing cholera into Haitiis particularly troubling given the humanitarianrole that MINUSTAH has played in Haiti. AsChapter V explains, through its conduct thatled to the cholera epidemic in Haiti, MINUSTAH3 executive summary

violated widely accepted principles that mostinternational humanitarian aid organizationspledge to follow. These principles have also beenaccepted and promoted by U.N. agencies. First, theU.N. violated the “do no harm” principle, whichrequires, among other general and specific duties,that humanitarian organizations observe minimalstandards of water management, sanitation, andhygiene in order to prevent the spread of disease.Second, by denying victims of the epidemicany remedy for the harms it caused, the U.N.violated the principle of accountability to affectedpopulations. Humanitarian relief standardsemphasize that establishing and recognizingmechanisms for receiving and addressingcomplaints of those negatively affected by reliefwork is a critical responsibility of humanitarianaid organizations. In Haiti, the U.N. has refusedto create a claims commission to receive andadjudicate third party claims. By not only rejectingits responsibility for the epidemic but also refusingto provide a forum in which its victims canmake their claims, the U.N. continues to violateminimum standards of accountability.Necessary Steps toward <strong>Accountability</strong>in HaitiHaving examined the U.N.’s derogation of itsobligations to the victims of the cholera epidemicunder international law, international humanrights law, and international humanitarianstandards, Chapter VI outlines the steps the U.N.and other principal actors in Haiti must take tomeaningfully address the cholera epidemic andensure U.N. compliance with its legal and moralduties. The U.N. will need to accept responsibilityfor its failures in Haiti, apologize to the victimsof the epidemic, vindicate the legal rights of thevictims, end the ongoing epidemic, and takesteps to ensure that it will never again cause suchtragically avoidable harm, in Haiti or elsewhere.The first three proposed courses of action forthe U.N. respond to the concerns raised in ChaptersIII-V: By accepting accountability when it errs,apologizing for its wrongs, and providing a remedyto victims of its wrongdoing, the U.N. will satisfyits obligations under the SOFA, internationalhuman rights law, and the humanitarian ethic ofaccountability. Furthermore, by taking concreteand meaningful steps to end the ongoing epidemicand guaranteeing that it will reform its practicesto ensure that it does not again cause such a publichealth crisis, the U.N. will address the structuralfailures that led to the outbreak and will begin tofulfill its moral duty to repair what it has damaged.To accomplish this, the U.N. must commit tomaking all necessary investments—particularlyin the areas of emergency care and treatmentfor victims of the disease and clean waterinfrastructure—to ensure that the epidemic doesnot claim more lives. In addition to reducing Haiti’svulnerability to future waterborne epidemics,investments in clean water can also help eliminatecholera from the country.Other entities, starting with the Governmentof Haiti and including NGOs, foreign governments(notably the United States, France, and Canada),and other intergovernmental actors, are also key toremediating the cholera epidemic. These actors musthelp provide direct aid to victims, infrastructuralsupport, and adequate funding for the preventionand treatment of cholera. This includes properlyfunding and supporting the recently completedNational Plan for the Elimination of Cholera in Haiti.The Plan is the Haitian Ministry of Health’s (MSPP)comprehensive program for the elimination ofcholera in Haiti and the Dominican Republic over thenext ten years.Finally, prevention of similar harms in thefuture requires that the U.N. commits to reformingthe waste management practices of its peacekeepersand complying with all provisions of the SOFAs itsigns with countries hosting peacekeepers.While the U.N. has played an important role inthe Haitian post-earthquake recovery effort, it hasalso caused great harm. The introduction of choleraby U.N. peacekeepers in Haiti has killed thousandsof people, sickened hundreds of thousandsmore, and placed yet another strain on Haiti’sfragile health infrastructure. The U.N.’s ongoingunwillingness to hold itself accountable to victimsviolates its obligations under international lawand established principles of humanitarian relief.Moreover, in failing to lead by example, the U.N.undercuts its very mission of promoting the rule oflaw, protecting human rights, and assisting in thefurther development of Haiti.4 executive summary

Recommendations Divided by Relevant Actor1. The United Nations and its Organs,Agencies, Departments, and ProgramsOffice of the Secretary-General• Appoint a claims commissioner per therequirements of paragraph 55 of the SOFA.• Ensure, per the requirements of Paragraph51 of the SOFA, that a claims commission isestablished and that its judgments are enforced.• Apologize publicly to the Haitian people for thecholera epidemic.• Coordinate funding for the MSPP Plan.Security Council• Ensure that peacekeepers are accountable fortheir actions in future missions.Department of <strong>Peacekeeping</strong> Operations• Ensure that SOFAs are followed in all missions topromote peacekeeper accountability.• Promulgate procedures consistent with SphereStandards to guide peacekeeping operations andconduct.MINUSTAH• Apologize publicly to the Haitian people for thecholera epidemic.• Ask the Secretary-General to establish a claimscommission.• Abide by compensation decisions as ordered by aclaims commission or any other legal forum• Vacate the Méyè peacekeeper base and allow thecommunity to turn the land into a treatmentcenter or memorial.2. The World Health Organization andthe Pan-American Health Organization• Continue and increase funding of the MSPP plan.• Provide technical expertise and ensureimplementation of the MSPP plan.3. National GovernmentsHaiti• Fund and supply cholera treatment centers forprimary care of cholera victims.• Continue to monitor outbreaks and gatherreliable data on the incidence of cholera.• Appoint a claims commissioner under Paragraph55 of the SOFA.• Demand that the U.N. appoint a claimscommissioner under paragraph 55 of the SOFA.• Effectively implement the MSPP Plan.United States• Fund immediate cholera treatment andprevention via grants to NGOs, the MSPP, andDINEPA.• Fund the MSPP plan, both directly and viaassistance to the U.N with fundraising fromother countries.• Request that the U.N. appoint a claimscommissioner.• Ensure that the CDC continues to support theMSPP Plan.France, Canada, and other NationalGovernments• Fund immediate cholera treatment andprevention, via grants to NGOs, the MSPP, andDINEPA.• Fund the MSPP plan, both directly and viaassistance to the U.N. with fundraising fromother countries.4. Non-Governmental Organizations• Provide supplies and technical expertise forimmediate cholera relief.• Help fundraise for and channel donations towardthe MSPP plan.• Continue to support the Government of Haiti inits public health efforts.5 recommendations

MethodologyThe findings in this report are based on aninvestigation of the origins of the outbreak andU.N. legal accountability conducted over a oneyearperiod. Researchers consulted U.N. treatiesand resolutions, international law treatises,and epidemiological studies of the cholerabacterium causing the epidemic, news accounts,and academic research in international law andinternational humanitarian law. Researchersalso consulted victims of the epidemic, activists,attorneys, journalists, aid workers, medicaldoctors, and government agency officials with firsthandknowledge of the epidemic and its aftermath.Researchers conducted most of theirinvestigation from the United States and wereregularly in contact with experts in Haiti. InMarch 2013, researchers traveled to Haiti to consultstakeholders in both the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince and in the town closest to the MINUSTAHbase where the cholera epidemic began.While in Haiti, researchers met withrepresentatives from: Association Haitienne deDroit de L’Environnment (AHDEN), Association desUniversitaires Motivés pour une Haiti de Droits(AUMOHD), Bureau des Avocats Internationaux(BAI), U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC),Collectif de Mobilisation Pour Dedommager LesVictimes du Cholera (Kolektif), Direction Nationalede l’ l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement (DINEPA),Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Partners inHealth (PIH), and the United States Agency forInternational Development (USAID). Researchersalso consulted residents of Méyè, Haiti who weredirectly affected by the cholera epidemic and whofiled claims against the U.N. seeking relief.Researchers presented the stakeholderswith a summary and outline of the report forcritical discussion. The final draft of the reportincorporates comments and feedback from theconsultations made during the trip to Haiti, as wellas from the close review of experts in internationallaw and public health.6 methodology

Chapter IMINUSTAH and theCholera Outbreak in Haiti7 section

Chapter IMINUSTAH and the Cholera Outbreak in HaitiSince the early 1990s, the United Nations hasdeployed several peacekeeping and humanitarianmissions to Haiti in response to recurring periodsof political unrest and socio-economic instability.In 2004, following a period of political turmoil,the U.N. Security Council established its currentHaitian mission: the U.N. Stabilization Missionin Haiti, known as MINUSTAH. 2 The SecurityCouncil charged MINUSTAH with a broadmandate encompassing both peacekeeping andhumanitarian operations. On January 12, 2010,a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, killinghundreds of thousands and further jeopardizingthe country’s already fragile infrastructure. Inthe wake of this tragedy, the Security Councilexpanded MINUSTAH’s mandate to respond to theongoing crisis. While MINUSTAH has contributedto Haiti’s stabilization, the mission has also beencriticized for its failures to protect human rights.Between October 19–20, 2010, nine monthsafter the earthquake, health officials confirmedeight cases of cholera in a remote region of centralHaiti. Cholera had not been observed in thecountry in over a century. The disease spread atan alarming rate, rapidly causing severe cases ofdiarrhea, dehydration, and death. Even before the2010 earthquake, Haiti suffered from a history ofpoor water, sanitation, and health infrastructure.While cholera can be easily prevented and treated,the country’s scarce resources and socio-politicalinstability have made the disease difficult tocontrol. As of April 2013, over 650,000 Haitians hadbeen infected by cholera and over 8,100 had died.The disease continues to spread through Haititoday, and the most optimistic estimates suggestit will take at least another decade to eliminate itfrom the country and the island.Independent investigations by scientists andjournalists have traced the source of the epidemicto MINUSTAH peacekeeping troops. An extensivebody of evidence shows that between October8–21, 2010, troops arriving from cholera-affectedareas of Nepal carried the disease into Haiti. Dueto poor sanitation facilities at the base wherethe troops were stationed, waste containingcholera contaminated the Artibonite River, Haiti’slargest river, and spread to the local population.Scientific studies and firsthand accounts leavelittle doubt that MINUSTAH peacekeepers were theinadvertent source of the cholera outbreak.Since the outbreak began, cholera victims andtheir advocates have repeatedly called on the U.N.to remedy past injuries and meaningfully addressthe ongoing crisis. The U.N., however, has refusedto hear these claims and its overall response to thecholera epidemic remains inadequate. The U.N.has denied its role in the epidemic and refusedto address victims’ claims for redress, despite itsobligations to do so under its own agreementswith Haiti and under instruments and principlesof international law. National and internationalactors have proposed plans to treat and eliminatecholera, but the plans lack sufficient funding toeffectively prevent and treat the disease. Haitianhealth and water and sanitation officials andNGOs that have been essential to the provision ofcholera treatment struggle to manage waves ofthe epidemic that spike during each rainy season.Haitians continue to suffer the consequences of thelargest cholera epidemic in the country’s history,while the party responsible for the outbreak—the U.N.—refuses to make a meaningful effort tocontain, control, and eliminate the disease or toremedy the harm already done.A. MINUSTAH Has Had an ExpandingMandate Marked by a Broad<strong>Peacekeeping</strong> Authority <strong>without</strong><strong>Accountability</strong>.The U.N. has had an intermittent peacekeepingpresence in Haiti since the early 1990s. 3 In April2004, following a period of political instability,the Security Council passed Resolution 1542,creating the U.N. Mission for the Stabilization ofHaiti (MINUSTAH). 4 MINUSTAH was establishedas a joint military and civilian mission with amandate to help Haiti address a broad range of8 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

issues, including peace and political stability, there-establishment of the rule of law, the protectionof human rights, and social and economicdevelopment. 5 MINUSTAH’s scope and operationshave expanded since 2004, and the longstandingpresence and activity of the mission have been metwith local criticism.MINUSTAH’s administration and fundinginvolve many players. In Resolution 1542, theSecurity Council supported the establishment ofthe Core Group, comprising representatives of theOrganization of American States, the CaribbeanCommunity and Common Market, internationalfinancial institutions, and other interestedstakeholders. 6 The Core Group’s purpose is tofacilitate the implementation of MINUSTAH’smandate and states enhance the effectiveness ofthe role of the international community in Haiti.Several countries, including Argentina, Brazil,Canada, Chile, France, Peru, and the United States,have assumed lead roles in MINUSTAH’s operationsin Haiti pursuant to Resolution 1542. 7Since its establishment, MINUSTAH has been amultidimensional peacekeeping mission uniquelyaimed at addressing a broad range of concerns. 8Whereas U.N. peacekeeping operations are generallydeployed in support of a peace agreement reachedbetween parties to a conflict, MINUSTAH wasdeployed <strong>without</strong> such an agreement or ongoingconflict. 9 Instead, MINUSTAH was established inresponse to a complicated and sometimes violentpolitical struggle among different factions in Haiti.In 2000, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was votedinto office during an election contested by politicalopponents and some members of the internationalcommunity. 10 In February 2004, former soldierstraining in the Dominican Republic invaded Haitiand took large areas of the country. PresidentAristide left Haiti on a plane controlled by the U.S.government. The U.S. government claimed thatPresident Aristide left willingly; President Aristideclaimed he was forced onto the plane. BonifaceAlexandre, then President of the Supreme Court,was sworn in as Interim President. 11 Mr. Alexandrerequested assistance from the United Nations instabilizing the country in the aftermath of theinsurrection, a request that eventually led to theestablishment of MINUSTAH. 12The complicated politics of MINUSTAH’sorigins are reflected in the mission’s broadmandate. The terms of MINUSTAH’s missionhave been defined by a series of Security CouncilResolutions establishing and renewing theMINUSTAH mandate. MINUSTAH’s originalmandate, set forth in Security Council Resolution1542, established three main mission goals: toensure a secure and stable environment, to supportthe conditions for democratic governance andinstitutional development, and to support thepromotion and development of human rights. 13In the same resolution, the Security Councilprovided that MINUSTAH “shall cooperate with theTransitional Government [of Haiti] as well as withtheir international partners, in order to facilitatethe provision and coordination of humanitarianassistance.” 14 Subsequent resolutions between 2005and 2009 renewed and provided minor adjustmentsto the original MINUSTAH mandate. 15MINUSTAH’s mission structure and operationsreflect the breadth of its mandate. The original 2004mission plan envisioned three main components:a military force to establish a secure and stableenvironment throughout the country, a civilianaffairs component responsible for overseeing acivilian police force and supporting initiatives tostrengthen local governmental and civil societyinstitutions, and a humanitarian affairs anddevelopment component. 16 The humanitarianaffairs and development office was tasked withcoordinating humanitarian aid among differentnational and international actors. Senior officersof all three components reported to the head ofmission, the U.N. Special Representative of theSecretary-General. 17 Additionally, the mission as awhole received support from the U.N. Secretariat’sDepartment of <strong>Peacekeeping</strong> Operations. 18 While thespecific structure of the different components haschanged since 2004, the basic organization remains. 19On January 12, 2010, a 7.0-magnitudeearthquake struck Haiti, killing over 200,000,destroying much of the capital, and strainingthe country’s already fragile social and politicalorder. 20 In response to the earthquake, the SecurityCouncil passed Resolutions 1908 and 1927, raisingMINUSTAH’s in-country troop levels and adjustingthe MINUSTAH mandate to include assisting9 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

the Government of Haiti in post-disaster reliefand recovery. 21 The Resolutions also reaffirmedMINUSTAH’s obligation to promote and protect thehuman rights of the Haitian people. 22MINUSTAH troops were tasked with key rolesin the immediate response to the earthquake, aswell as the longer-term humanitarian effort. 23Troops assisted in essential humanitarianfunctions including clearing debris, distributingfood, and rebuilding local infrastructure. 24MINUSTAH troops were also responsible formonitoring the human rights situation ofparticularly vulnerable Haitians. For instance,troops led security assessments and policingefforts to ensure the security of those living inspontaneous camps and in areas affected by theearthquake. 25 The mission was further chargedwith building capacity of local institutions toadminister justice and ensure the rule of law. 26Despite MINUSTAH’s role in Haiti’sstabilization, the mission has drawn repeatedcriticism on several fronts. 27 Since the earlydays of the mission, Haitians have denouncedalleged physical abuses by troop members 28 —andMINUSTAH’s seeming unwillingness to investigatethese claims. In November 2007, for instance, over100 Sri Lankan troops were repatriated due toallegations of sexual exploitation and abuse. 29 InSeptember 2011, media outlets released a video ofUruguayan troops harassing an 18-year-old boy,who later claimed that he had been raped by thetroops. 30 In August 2010, 16-year-old Jean GéraldGilles was found hanging outside the MINUSTAHbase in Cap Haitïen. 31 MINUSTAH never initiateda public investigation. 32 These and other similarincidents have led to popular discontent amongHaitians with MINUSTAH’s presence.artibonite riverMirebalais ● MéyèPort-au-Prince ●10 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

The MINUSTAH base (misspelled “MINUSTHA” on Google Earth) in Méyè, on the banks of the Méyè Tributary.Artibonite RiverMéyè TributaryThe town of Mirebalais, located just north of Méyè, where the Méyè Tributary meets the Artibonite River.11 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

B. The Outbreak of Cholera Has HadDevastating Consequences for theHaitian Population.On October 19, 2010, Haitian health officialsdetected an unusually high number of cases ofacute diarrhea, vomiting, and severe dehydrationin two of Haiti’s ten geographical regions known asadministrative departments. 33 Officials sent stoolsamples for testing to the Haitian National PublicHealth Laboratory (LNSP), and four days later, theLNSP confirmed the presence of Vibrio cholerae(V. cholerae), the bacterium that causes cholera. 34The first set of cases was localized in the upperArtibonite River region, where the Méyè Tributarymeets the Artibonite. By late October 2010, Haitianofficials reported a second set of cases in the lowerArtibonite River region, near the river’s delta. 35 Byearly November, cholera had reached the capital ofPort-au-Prince. 36 Cholera had also spread to citiesacross the North-West and North Departments. 37By November 19, the Haitian Ministry of Health(MSPP) reported positive cholera cases in all tenadministrative departments. 38 By then, over 16,000Haitians had been hospitalized with acute waterydiarrhea and over 900 had died from cholera. 39As Chapter II details, cholera is transmitted bythe consumption of food or water contaminatedwith V. cholerae. 40 The main sources of an outbreakare usually contaminated drinking water andinadequate sanitation; feces from those infectedwith V. cholerae contaminate the water supply,and the bacterium spreads when others drinkthe contaminated water. 41 A gastrointestinaldisease characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, anddehydration, cholera is easily treatable. Withaggressive electrolyte replacement—often simplydelivered in drinking water—fatalities are reducedto less than 1%. 42In Haiti, poor water, sanitation, and healthinfrastructure has facilitated the spread of choleraand prevented its effective treatment. Even beforethe earthquake, the country had an ineffectual andinstitutionally fragmented water and sanitationsector. 43 Approximately 10% of Haitians had accessto running water and only 17% had access toimproved sanitation services. 44 Additionally, untilAugust 2009, the water and sanitation sector hadneither a single national coordination authoritynor sufficient funds. 45 Instead, the sector wasregulated by several governmental institutionsthat were unable to ensure quality water andsanitation services. 46 After a 2009 reform, the waterand sanitation sector still lacked sufficient fundingand was unable to prevent the spread of cholerain the early stages of the epidemic. 47 Meanwhile,the public health sector in Haiti has been unableto treat cholera effectively. The health system inHaiti is supervised and coordinated by a singleentity, the MSPP. 48 Due to financial constraints andthe lack of local capacity to coordinate health careservices, the MSPP has been unable to guaranteeadequate cholera treatment for all Haitians.The Haitian cholera epidemic is one of theworld’s largest national cholera epidemics inrecent history. 49 In 2010 and 2011, Haitiansaccounted for roughly half of cholera cases anddeaths reported to the World Health Organization(WHO). 50 In the first year of the epidemic, over470,000 Haitians were infected and over 6,600 diedof cholera. 51 By October 2012, over 600,000 Haitianshad been infected and over 7,400 had died fromcholera. 52 As of April 2013, the MSPP has reportedover 650,000 infections, and over 8,100 deaths. 53Due to unreported cases in remote areas, thesenumbers likely underestimate the actual harmcaused by the cholera epidemic in Haiti. 54Although more than two years have passedsince the outbreak began, cholera still poses anongoing threat to people in Haiti. 55 The diseasecontinues to contaminate Haiti’s drinking watersources. As rivers overflow with each rainy season,inadequate sewage systems allow for continuedcross-contamination between infected feces anddrinking water sources, perpetuating the cycle ofdisease. Additionally, treatment programs remaininadequate due to a shortage of funding. 56 Expertsexpect Haiti will suffer from cholera for at least adecade more. 57C. Independent Investigations HaveTraced the Source of the Epidemic toMINUSTAH <strong>Peacekeeping</strong> Troops.As Chapter II discusses, nearly every majorinvestigation of the cholera crisis has identified12 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

Top:The MINUSTAH base in Méyè.Below:MINUSTAH peacekeepersentering the base.U.N. peacekeeping troops from Nepal as thesource of the outbreak. 58 Outbreak investigations,environmental surveys, molecular epidemiologicalstudies, and journalistic accounts all demonstratethat the troops were exposed to cholera in Nepaland introduced V. cholerae bacterium into Haiti.These investigations highlight five key factsabout the epidemic. First, there was no activetransmission of cholera in Haiti prior to October2010. Second, the epidemic began at a single pointin an area that encompassed the MINUSTAHbase where Nepalese peacekeeping troops werestationed. Third, these troops had been exposedto cholera in Nepal, and fourth, their fecescontaminated the local water supply in Haiti.Finally, the Haitian outbreak involved a singlestrain of Nepalese origin.Historical records show no reported cases ofsymptomatic cholera in Haiti before the arrivalof MINUSTAH troops in October 2010. 59 Expertshave identified three major cholera outbreaks inthe Caribbean: in 1833–1834, 1850–1856, and 1865-13 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

1872. 60 None of these three outbreaks affected Haiti,even though cholera cases were reported in theneighboring Dominican Republic in 1867. 61 As earlyas 1850, Haitian historians commented on thestriking absence of cholera cases in the country.Additionally, no symptomatic cases of cholera werereported in the Caribbean during the 20th century. 62The 2010 Haitian outbreak began in a regionencompassing the MINUSTAH base in Méyè,a small town in the Artibonite administrativedepartment of central Haiti. Following the firststool samples from patients in this area sent fortesting on October 19 and 20, 2010, 63 the LNSPconfirmed the presence of V. cholerae on October22. 64 Initial cases of cholera were clustered in anarea surrounding the MINUSTAH base. The base issituated on the Méyè Tributary, which flows pastthe town of Mirebalais and into the ArtiboniteRiver. The initial cases of confirmed choleraoccurred downstream from the base. 65Nepalese troops stationed at the Méyè basehad been recently exposed to cholera in Nepal, andtheir feces contaminated the drinking water oflocal Haitians. As part of MINUSTAH’s 2010 troopincrease, a battalion of Nepalese soldiers arrivedin Haiti between October 8–24, 2010. 66 The soldierscame from regions of Nepal recently afflicted byoutbreaks of cholera. 67 The MINUSTAH base hadpoor sanitation conditions. The camp’s wasteinfrastructure was haphazardly constructed,allowing for waste from the camp’s drainage canaland an open drainage ditch to flow directly intothe nearby Méyè Tributary. 68 The drainage siteswere also susceptible to flooding and overflow intothe tributary during rainfall. 69 Direct evidencethat sewage from the base contaminated theMéyè Tributary of the Artibonite River exists. 70 OnOctober 27, journalists caught MINUSTAH troopson tape trying to contain what appeared to be asewage spill at the MINUSTAH base. Families inthe area also confirmed that waste from the campfrequently flowed into the river. 71 Most of the initialcholera patients reported drinking water from theArtibonite River.The close relationship between the Haitiancholera strain and the Nepalese strain furthersupports the conclusion that Nepalese troopsbrought cholera into Haiti. 72 Although there hasbeen no medical documentation of the MINUSTAHtroops carrying cholera, researchers have identifieda common strain of V. cholerae causing cholera inHaiti. 73 Experts have compared this strain with anumber of known cholera strains from around theworld. 74 Genetic evidence shows that the Haitianstrain is descended from a V. cholerae strain ofNepalese origin. In other words, the cholera thatcaused Haiti’s epidemic originated in Nepal. 75D. National and International EffortsHave Been Unsuccessful inEliminating Cholera.A combination of Haitian national agencies,multilateral agencies, other countries, andinternational NGOs have responded to thecholera outbreak. Unfortunately for Haitians, thispatchwork of services, training, and surveillancehas proven inadequate. Much of the choleraresponse effort is not adequately funded andineffective for either the short or longterm.1. Short-term ResponseIn the immediate aftermath of the earthquake,national, international, and NGOs anticipatedthat the massive damage done to Haiti’s fragileinfrastructure would render the countryvulnerable to disease and began to prepareaccordingly. None of these organizations, however,expected an outbreak of cholera, given the disease’slong absence from the country. As a result, localhealth workers had little more than basic trainingon cholera treatment. National health staff had anexisting knowledge of cholera, how it was spread,its treatment, and proper modes of prevention,but few were trained in handling an emergencyoutbreak of the disease.Because of this, during the first phase ofthe epidemic, an international NGO, MédecinSans Frontières (MSF), was the lead provider oftreatment. International humanitarian NGOslike MSF have provided medical services in Haitithroughout the cholera crisis. MSF establishedsome of the first cholera treatment programs,rapidly expanding services in the months of thespiraling outbreak by deploying health workers tothe country and opening cholera treatment centers14 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

(CTCs). By November 2010, just a month after thefirst cases of cholera appeared in Haiti, MSF hadset up 20 CTCs; by early December, 20 more CTCshad been built. CTCs providing oral rehydrationsolution, the primary course of treatment forcholera, were also created in all of the regionsaffected by the disease. MSF set aside some 3,300beds in its facilities for cholera treatment, and bymid-December 2010, the organization had providedcare for more than 62,000 people. 76 MSF’s abilityto provide cholera treatment, however, was soonoverwhelmed by the volume of cholera cases as theoutbreak proved worse than originally anticipated.The treatment plan in the immediateaftermath of the outbreak focused on preventionof cholera infection and death. Local healthauthorities disseminated prevention informationto inhabitants of the rural areas near Mirebalaisand the Artibonite Delta where the first casesappeared. The prevention materials advised boilingor chlorinating drinking water and buryinghuman waste in the hope of stemming the spreadof cholera and avoiding further contaminationof water sources. Due to the rapid spread of thedisease and the high initial case fatality rate, MSPPand the U.S. government focused on five immediatepriorities: preventing deaths in treatment facilitiesby distributing supplies and providing training;preventing deaths in communities by supplyingoral rehydration solution sachets to homes andurging sick individuals to seek immediate care;preventing disease spread by promoting properhygiene and sewage disposal; conducting fieldinvestigations and guiding prevention strategies;and establishing a national cholera surveillancesystem to monitor the spread of the disease. 77Some training of field workers by internationaland bilateral organizations, including the U.S.Centers for Disease Control (CDC), contributed tothe treatment of effected populations during thefirst months of the epidemic. However, neitherthe MSPP nor international NGOs were able tocompletely contain the outbreak.outbreak. The mere task of providing treatmentsupplies has proven daunting as people in Haiticontinue to contract cholera. Difficulties inproviding treatment at the onset of the epidemicwere exacerbated by the fact that only one actor—the Program on Essential Medicine and Supplies,overseen by MSPP and the Pan-American HealthOrganization (PAHO)—distributed all donatedhealth care materials.Several medical organizations continue toprovide prevention and treatment for cholera inpartnership with the MSPP, but the initial fundingfor such work is nearly exhausted. Many aid groupshave already withdrawn from the country due toa lack of funding, and emergency cholera fundingfrom the CDC and World Bank is expected todecrease next year. 78In November 2012, the U.N. announced a $2.27billion initiative to eliminate cholera in Haiti andthe Dominican Republic in the next ten years. 79 Ajoint initiative among the WHO, PAHO, the CDC,and MSPP, the plan is comprehensive; it addresseswater and sanitation, waste disposal, integration ofcholera diagnosis and treatment into basic medicalscreening practices, and provision of choleravaccinations to high-risk groups. However, theU.N. has yet to secure all but a small fraction of thefunding necessary to complete the project fromU.N. member states. 80 To date, the U.N. has onlycommitted to supplying $23.5 million, less than 1%of the necessary funding.Both the short-term and long-term plans forresponding to cholera in Haiti have been criticizedas unrealistically optimistic. International NGOslike MSF struggle to provide quality care as theirbasic treatment supplies dwindle. The mortalityrate in some CTCs has recently risen to analarming 4% as a result of diminishing supplies. 81Although the plan to eliminate cholera in Haitimay be well-conceived in the abstract, it is of littlepractical value <strong>without</strong> proper funding.2. Long-term ResponseThe long-term effort to treat cholera and eliminatethe disease from Haiti has been less effectivethan the short-term response following the initial15 minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

E. The United Nations Has Failed toProvide Redress for Victims of theEpidemic.Cholera victims and their advocates have calledon the U.N. to redress the injuries of those harmedby the disease and take responsibility for theongoing epidemic. A number of efforts to hold theU.N. accountable have been underway since theoutbreak began, although to date they have notbeen successfulFirst, Haitian human rights organizations,activists, and lawyers have called for the U.N.to assume responsibility for its actions underthe Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) it signedwith the Government of Haiti in July of 2004. 82The SOFA defines the relationship between theU.N., including its agents in MINUSTAH, and theGovernment of Haiti. It also lays out the terms ofthe MINUSTAH mission, providing peacekeepingtroops and U.N. personnel legal immunity fromsuit in national and international courts. Inexchange, the SOFA provides for the establishmentof a commission to hear claims from third partiesinjured as a result of MINUSTAH operations.Despite this, no such claims commission has beenestablished for victims of the cholera epidemic. 83In a letter to the Haitian Senate dated March 25,2013, lawyers on behalf of Haitian victims calledon the Government of Haiti to assert its right to aclaims commission under the SOFA. 84 In responseto the inaction of the U.N. and the Governmentof Haiti, these attorneys are also considering asuit to compel the Government of Haiti to initiatethe establishment of a claims commission byappointing a commissioner. 85A second effort to hold the U.N. accountablefor the epidemic was attempted through an appealto the Inter-American Commission on HumanRights (IACHR). In October 2011, a team of Brazilianlawyers acting on behalf of Haitian choleravictims filed a case against the U.N. at the IACHR. 86Petitioners claimed that the U.N.’s actions in Haitiviolated a number of rights under the AmericanConvention on Human Rights. Petitioners arguedthat the IACHR could receive the complaintbecause the U.N. was an organization actingwithin a territory under the IACHR’s jurisdiction. 87To date, the IACHR has not provided an officialresponse to this petition. 88A third legal process began in November 2011,when Haitians infected by cholera and familymembers of those who had died of the diseasesubmitted a petition for relief to the MINUSTAHclaims unit in Haiti and U.N. headquarters inNew York. 89 Petitioners alleged that MINUSTAHnegligently maintained its waste managementfacilities at the MINUSTAH camp in Méyè,which led to the cholera outbreak. 90 Petitionersrequested a fair and impartial adjudication ofthe claim according to the terms of the SOFA,compensation to petitioners, monetary reparationsto victims of cholera at large, and a public apologyincluding acceptance of responbility for causingthe epidemic. 91 On December 21, 2011, the U.N.acknowledged receipt of the petition, and promised“a response in due course.” 92 Fourteen monthslater, on February 21, 2013, petitioners received aresponse from the U.N. Under-Secretary-Generalfor Legal Affairs, Patricia O’Brien. 93 The U.N. refusedto consider the claims because such consideration“would necessarily include a review of political andpolicy matters.” 94 Citing no precedent or authority,the U.N. response stated that this made the claim“not receivable” under Section 29 of the Conventionon the Privileges and Immunities of the UnitedNations. Thus, the U.N. effectively invoked legalimmunity to defeat the claims. On May 7, 2013,petitioners responded to the letter, challenging theU.N.’s argument that the claim was not receivable. 95Additionally, petitioners stated that if they did notreceive a timely a response within 60 days, theywould file their claims in a court of law. 96Since the 2010 outbreak, Haitians haverepeatedly expressed discontent with MINUSTAHand the U.N. for causing the cholera epidemicin the first instance and their management of itthereafter. Repeated protests since 2010 have calledfor U.N. withdrawal. The U.N., however, has notprovided a meaningful response. The organizationhas refused to consider the petition for relief or toprovide a forum to adjudicate repeated demandsthat it accept responsibility for the introduction ofcholera into Haiti. 97 To this day, the U.N. continuesto deny accountability for the epidemic or considerthe merits of any claims made by its victims.16minustah and the cholera outbreak in haiti

Chapter IIScientific InvestigationsIdentify MINUSTAHTroops as the Sourceof the Cholera Epidemic17 section

Chapter IIScientific Investigations Identify MINUSTAHTroops as the Source of the Cholera EpidemicAn extensive scientific literature has tracedthe source of the Haitian cholera epidemicto the MINUSTAH camp in Méyè. Outbreakinvestigations, environmental surveys, andmolecular epidemiological studies—includingthose conducted by the U.N.’s own experts andsome of the world’s foremost experts on choleraand infectious disease—all demonstrate thatcholera in Haiti was transmitted from a singlesource, the Méyè MINUSTAH base in central Haiti.These studies show that the peacekeepers stationedat the base, who had arrived from Nepal shortlybefore the first cases of cholera were reportedin Haiti, were carriers of a strain of V. cholerae,the bacterium (V. cholerae), the bacterium thatcauses cholera, also from Nepal. Poor sanitationconditions at the MINUSTAH camp allowed forwaste to flow into the nearby waterways, resultingin the inadvertent introduction of V. cholerae intothe Méyè tributary. The bacterium spread throughthe Tributary into the Artibonite River and otherconnected water sources. As a result, individualsconsuming water from the Méyè Tributary and theArtibonite River contracted cholera.Four key findings confirm that the epidemic’spoint source transmission—or common origin—was the MINUSTAH peacekeeping troops:• There was no active transmission of cholera inHaiti prior to October 2010. Historical recordsdating back to the 1800s report no cases ofcholera in Haiti. No cholera epidemics weredocumented in the Caribbean during the 20thcentury. During the Caribbean epidemics of the19th century, no cases were reported in Haiti.• The initial area affected by the epidemicencompassed the location of the MINUSTAHbase. Epidemiological modeling during theinitial outbreak shows no symptomatic choleracases other than in the areas surrounding theMINUSTAH camp in Méyè. Models suggestthat the origin of the disease was near theMINUSTAH base, from which cholera thenspread throughout the country.• The troops at the MINUSTAH base wereexposed to cholera in Nepal, and their fecescontaminated the water supply near the base.The peacekeeping troops stationed at theMINUSTAH base in Méyè were deployed toHaiti from Nepal, where cholera is endemicand a outbreak had occurred one month priorto their arrival in Haiti. These troops wereexposed to cholera in Nepal just prior to theirdeparture to Haiti. Due to the poor sanitationinfrastructure at the MINUSTAH base, fecesfrom the troops contaminated the ArtiboniteRiver, one of Haiti’s main water sources.• The Haiti cholera outbreak is traceable to asingle cholera strain of South Asian origin foundin Nepal. Molecular studies of stool samplescollected from multiple patients reveal a singlecholera strain as the source of infection in Haiti.Genetic analyses show that the Haitian strain isidentical to recent South Asian strains found inNepal and is most likely a descendant of thesestrains. Outbreak investigations demonstratethat the initial cases were confined to the areanear the MINUSTAH base in Méyè. Both setsof studies suggest that the outbreak beganwith the introduction of a single cholera strainendemic to parts of Nepal into the water sourcenear the MINUSTAH base.Separately, these various studies propose a linkbetween the MINUSTAH peacekeepers from Nepaland the Haitian cholera epidemic. Combined,they provide compelling evidence of the causalrelationship between the MINUSTAH troops andthe introduction of cholera into Haiti.18 scientific investigations identify minustah troops as the source of the cholera epidemic

The Méyè Tributary. The MINUSTAH camp is to the left of the tributary.The left-hand side of the picture shows barricades along the perimeterof the MINUSTAH camp.Barricades along the perimeter of the MINUSTAH camp.A. Historical Records Show No Evidenceof an Active Transmission of Cholera inHaiti Before October 2010.Historical records dating back to the 19th centuryshow no evidence of cholera in Haiti prior toOctober 2010. 98 While it is difficult to confirm thehistorical absence of disease, no cholera epidemicwas reported in the Caribbean region during the20th century. 99 Historical accounts documentthree Caribbean pandemics of cholera in the 19thcentury: in 1833–1834, 1850–1856, and 1865–1872. 100 Nomedical reports document cholera in Haiti duringthese periods. 101 Researchers thus have concludedthat there were no significant cases of cholera inHaiti during the 19th or 20th centuries. 102 Historicalevidence therefore supports the conclusion thatthe 2010 outbreak was caused by the introductionof cholera into Haiti from a foreign source.B. The Initial Area Affected by theEpidemic Encompassed the Locationof the MINUSTAH Base.Geographical and temporal analyses of theHaitian cholera outbreak show that the epidemicoriginated near the MINUSTAH base in Méyè andspread downstream through the Méyè Tributaryand into the Artibonite River. Case analyses revealthat only individuals exposed to water from thisriver system initially contracted cholera.The first cholera cases documented betweenOctober 14–18 arose in Méyè and Mirebalais, just2 kilometers north of Méyè. Hospital admissionrecords and anecdotal information from theMirebalais Government Hospital showed thatbetween September 1–October 17, sporadic diarrheacases <strong>without</strong> death were seen at a consistentbaseline rate in both adults and children. 103 Thefirst recorded case of severe diarrhea necessitatinghospitalization, and the first deaths fromdehydration in adult patients occurred the nightof October 17 and early morning of October 18.During these two days, the majority of the patientpopulation was of adult age, a fact stronglysuggesting that the cause of the diarrheal caseswas cholera as severe diarrhea in adults is rare. 104Staff reported that the first cases of cholerawere attributed to an area located 150 metersdownstream from the MINUSTAH camp in Méyè. 105On October 19, clusters of patients near theArtibonite Delta were hospitalized with severeacute diarrhea and vomiting, and deaths, includingof three children, were reported by health centersand hospitals in the region. 106 Staff at the AlbertSchweitzer Hospital reported that their firstsuspected case of cholera occurred on October18, 2010, when a migrant worker arrived at thehospital already deceased. The first confirmed casesof cholera occurred at the hospital on October 20.After October 20, the number of cases admittedto the hospital was so high that exact record19scientific investigations identify minustah troops as the source of the cholera epidemic

keeping became difficult. 107 At St. Nicolas Hospitalin St. Marc, a city located 70 kilometers southwestof Mirebalais, medical records showed that aconsistently low level of diarrhea cases, mostlyamong children, remained stable until October20, when 404 hospitalizations were recorded in asingle day—one patient every 3.6 minutes—alongwith 44 deaths from cholera. These cases came from50 communities throughout the Artibonite RiverDelta region, with an average of eight patients percommunity arriving at the hospital on October 20. 108Following the early reports of cholera, theMSPP and the CDC conducted an investigation ofdisease incidence at five hospitals in the ArtiboniteDepartment from October 21st to October 23.To establish a date of onset for the outbreak,investigators reviewed medical records fromOctober 2010 for each hospital to identify casesthat required hospitalization due to diarrheaand dehydration. Because detailed medicalrecords were not available for the investigation,hospitalizations due to “severe diarrhea” were usedas a proxy for cholera cases, with a particular focuson adult patients since severe diarrhea within thisage group is considered rare. 109 From October 20–22,the majority of patients admitted with symptomsof cholera and the majority of those who diedfrom these symptoms were older than 5 years old,strongly suggesting that the cause of their illnesswas in fact cholera. 110 In addition, stool samplesfrom patients hospitalized in the administrativedepartments of Artibonite and Centre, southeastof Artibonite Department, were brought to theLNSP where rapid tests on eight specimens testedpositive for V. cholerae O1. 111Epidemiologists have modeled the Haitianoutbreak using data collected by the MSPP’sNational Cholera Surveillance System. 112 Withan “explosive” start in the Lower Artibonite, thecholera epidemic peaked within two days, andthen decreased drastically until October 31. 113Once adjustments were made for population andspatial location, the risk of contracting cholerafor an individual living downstream of the MéyèTributary was calculated at 4.91 times higher thanthe average Haitian. 114By October 22, cholera cases were noted infourteen additional communes, 115 most of themin the mountainous regions that border theArtibonite plain and in Port-au-Prince. In eachcommune, the incidence of cholera coincidedwith the arrival of patients from the borderingcommunes where affected individuals worked inrice fields, salt marshes, or road construction. 116The southern half of Haiti, in contrast, remainedcholera-free for as long as six weeks after theepidemic broke out, with clusters of the diseasegradually occurring over a slightly staggeredtimespan in the North-West, Port-au-Prince, andNorth Departments. 117Cholera emerged in Port-au-Prince on October22 with the arrival of patients from Artibonite, andremained surprisingly moderate in the capital cityfor some time after the beginning of the outbreak.From October 22–November 5, 2010, the incidence ofcholera remained moderate with an average of only74 daily cases. Although the epidemic eventuallyexploded in Cité-Soleil, a slum located in thefloodplain near the sea, internally displaced person(IDP) camps in the city remained relatively free ofcholera for up to six weeks after the epidemic brokeout. Overall, despite the earthquake-related damageto the city and the presence of many IDP camps,cholera struck less severely in Port-au-Prince thanin other departments in the country. In the Haitiancapital, the incidence rate was only 0.51% untilNovember 30. By contrast, during this same period,the following incidence rates were reported: 2.67%in the Artibonite Department, 1.86% in the CentreDepartment, 1.45% in the North-West Department,and 0.89% in North Department. The mortality ratein Port-au-Prince was also significantly lower (0.8deaths/10,000 persons compared with 5.6/10,000 inArtibonite, 2/10,000 in Centre, 2.8/10,000 in North-West, and 3.2/10,000 in North). 118 As cholera is adisease commonly associated with poor water andsanitation, slum areas, over-crowding, and flooding,the low cholera incidence and mortality rates inPort-au-Prince, and the IDP camps in particular,were unexpected. Also contrary to expectations,data showed the highest incidence of disease in therural Artibonite region.The incredible speed at which choleraspread to all seven communes near the lowerArtibonite River in Haiti strongly suggests thatthe contamination began at the Méyè Tributary.20scientific investigations identify minustah troops as the source of the cholera epidemic

2010July 28–August 14 A 1,400-case outbreak of cholera occurs in mid-western region of Nepal.October 8–21October 12October 14–19October 19October 21–23October 23Late OctoberEarly NovemberNovember 19MINUSTAH troops arrive in Haiti after a 10-day leave visiting their families in Nepal.A 28-year-old man from the town of Mirebalais, located downstream from the MéyèMINUSTAH Base, is the first cholera patient of the 2010 epidemic. This man suffers from apsychiatric condition and regularly drank untreated water from a stream fed by the MéyèTributary. The man develops profuse watery diarrhea. Less than a day after the onset ofsymptoms, he dies <strong>without</strong> medical attention. The man is not diagnosed with V. choleraethrough laboratory methods.Outbreak investigations also identify several families living in Méyè as the firsthospitalized cholera patients. These individuals exhibit cholera symptoms. Stool samplesfrom a subset of these patients test positive for V. cholerae.Haitian health officials report unusually high numbers of patients with watery diarrheaand dehydration in two of Haiti’s ten administrative departments.Additional cases of cholera are reported among the inhabitants of Mirebalais.National Public Health Laboratory (LNSP) confirms presence of V. cholerae.Haitian officials report an explosion of cases across the Artibonite River Delta.Cholera has spread to cities across the Haitian North-West and North Departments,which are roughly equidistant from the Artibonite Delta.The Haitian Ministry of Health (MSPP) reports positive cholera cases in all ten Haitianadministrative departments.The transmission of a waterborne disease likecholera across geographical regions takes aslong as it would take for the water to travel thesame distance. An Independent Panel of Experts,appointed by the U.N. to investigate the originsof the epidemic, calculated that it would take twoto eight hours for water in the Méyè Tributaryto flow from near the MINUSTAH camp’s wastefacilities to its junction with the ArtiboniteRiver. 119 The U.N. Independent Panel of Expertsalso found that a contamination of the Artibonitestarting at the Méyè Tributary would be fullydispersed throughout the Artibonite River Deltawithin a maximum of two to three days. Thistimeline, the panel noted, was “consistent withthe epidemiological evidence” showing that theoutbreak began in Mirebalais, near the MéyèTributary, and that cases of patients experiencingcholera-like symptoms appeared in the ArtiboniteRiver Delta area two to three days after thefirst cases of cholera were seen upstream inMirebalais. 120C. The Troops at the MINUSTAH Base WereExposed to Cholera in Nepal, and TheirFeces Contaminated the Water SupplyNear the Base.Epidemiological studies report that the U.N.peacekeeping troops that arrived in Méyè justbefore the Haitian cholera outbreak had beenexposed to the disease in Nepal shortly before theirdeparture to Haiti. Poor sanitation infrastructureat the MINUSTAH camp in Méyè led to fecalcontamination of the water supply near the campand near the site of the first cases of cholera inHaiti. Locals regularly used this water for drinking,cooking, and bathing.Nepalese peacekeeping troops arriving at theMINUSTAH camp in Méyè between October 8–24had been exposed to cholera in Nepal. Cholera isendemic to Nepal and the country experiencessporadic outbreaks every year. In 2010, a 1,400-case outbreak occurred in the country, beginningaround July 28 and lasting until mid-August,just prior to the Nepalese troops’ deploymentto Haiti. 121 During this outbreak, MINUSTAH21scientific investigations identify minustah troops as the source of the cholera epidemic

peacekeeping troops were training in Kathmandu.At the end of their training in late Septemberand early October, the peacekeepers received amedical evaluation, and none showed symptomsof cholera. 122 The absence of symptoms, however,did not prove that the peacekeepers were cholerafree.Cholera has a two to five day incubationperiod and can be carried asymptomatically. 123Prior to their departure for Haiti, the peacekeepersspent ten days visiting their families. 124 Afterthis visiting period, none of the troops exhibitedcholera symptoms. 125 Despite the recent choleraoutbreak in Nepal and the high risk of exposureand infection during the ten-day visitation period,none of the peacekeepers were tested for V. choleraeimmediately before their departure to Haiti. 126Once a water source like the Méyè Tributarybecomes contaminated with cholera, humanpopulations exposed to the contaminated water areprone to subsequent outbreaks. 127 The magnitude ofsuch outbreaks varies according to the probabilityof secondary transmission. 128 A higher likelihoodof such transmission exists in countries likeHaiti with poor infrastructure and inadequatesewage systems and is also associated with thefrequent arrival of foreign populations like troopdeployments from overseas.Environmental surveys conducted by theU.N. Independent Panel of Experts describethe MINUSTAH camp’s inadequate wasteinfrastructure at the beginning of the epidemic.The experts identified a “significant potentialfor cross-contamination” of shower and cookingwater waste with water waste containing humanfeces due to the poor pipe connections in themain showering and toilet area of the camp. 129The experts also noted that the construction ofthe water pipes in these areas was “haphazard,with leakage from broken pipes and poorpipe connections.” 130 The experts found thatcontamination was especially likely in an areawhere pipes “run over an open drainage ditch thatruns throughout the camp and flows directly intothe Méyè Tributary system.” 131The U.N. Independent Panel of Experts’ surveyof the MINUSTAH base and its facilities furtherobserved that disposal of human waste outsidethe camp contaminated the Méyè Tributary. Blackwater tanks, containing water contaminatedwith fecal matter from the camp, were emptied“on demand by a contracting company approvedby MINUSTAH headquarters in Port-au-Prince.” 132According to MINUSTAH staff, the companycollected the waste in a truck and deposited itin a disposal pit several hundred meters fromthe camp. 133 This pit was near the southeasternbranch of the Méyè Tributary and was susceptibleto flooding and overflow into the Méyè Tributaryduring rainfall. 134 The experts calculated that itwould take roughly two to eight hours for water toflow from the septic pit to the junction with theArtibonite River. 135Haitians who contracted cholera in the earlystages of the epidemic had consumed water fromthe Artibonite River. Almost no cases of cholerawere reported in communities along the Artibonitethat did not use water from the river. From October21–23 the MSPP and CDC investigative team issueda standardized questionnaire to a sample of 27patients in the five hospitals of the ArtiboniteDepartment. The majority of the surveyedpatients reported living or working in rice fields incommunities that were located alongside a stretchof the Artibonite River. Of the patients surveyed,67% reported consumption of untreated water fromthe river or canals connected to the Artiboniteprior to onset of symptoms, 67% did not practiceclean water precautions (chlorination or boilingof water prior to use), and 27% practiced opendefecation.Furthermore, the U.N. Independent Panelof Experts found that in the Mirebalais market,seafood was neither sold nor consumed,making a route of infection originating inthe ocean surrounding Haiti highly unlikely.This determination left the Artibonite Riveras the only potential source of the epidemic.The experts concluded that, based on theepidemiological evidence, the cholera epidemicbegan in the upstream region of the ArtiboniteRiver on October 17 and the most likely cause ofinfection in individuals was their consumptionof contaminated water from the river. In theirinitial report in 2011, the U.N. Independent Panelof Experts concluded that there was insufficientevidence to attribute the epidemic to MINUSTAH22scientific investigations identify minustah troops as the source of the cholera epidemic