Advanced Liver Disease: What Every Hepatitis C Virus Treater ...

Advanced Liver Disease: What Every Hepatitis C Virus Treater ...

Advanced Liver Disease: What Every Hepatitis C Virus Treater ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

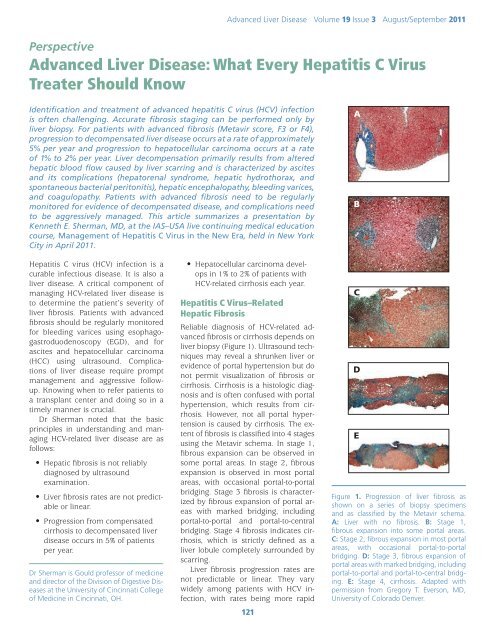

<strong>Advanced</strong> <strong>Liver</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> Volume 19 Issue 3 August/September 2011Perspective<strong>Advanced</strong> <strong>Liver</strong> <strong>Disease</strong>: <strong>What</strong> <strong>Every</strong> <strong>Hepatitis</strong> C <strong>Virus</strong><strong>Treater</strong> Should KnowIdentification and treatment of advanced hepatitis C virus (HCV) infectionis often challenging. Accurate fibrosis staging can be performed only byliver biopsy. For patients with advanced fibrosis (Metavir score, F3 or F4),progression to decompensated liver disease occurs at a rate of approximately5% per year and progression to hepatocellular carcinoma occurs at a rateof 1% to 2% per year. <strong>Liver</strong> decompensation primarily results from alteredhepatic blood flow caused by liver scarring and is characterized by ascitesand its complications (hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic hydrothorax, andspontaneous bacterial peritonitis), hepatic encephalopathy, bleeding varices,and coagulopathy. Patients with advanced fibrosis need to be regularlymonitored for evidence of decompensated disease, and complications needto be aggressively managed. This article summarizes a presentation byKenneth E. Sherman, MD, at the IAS–USA live continuing medical educationcourse, Management of <strong>Hepatitis</strong> C <strong>Virus</strong> in the New Era, held in New YorkCity in April 2011.AB<strong>Hepatitis</strong> C virus (HCV) infection is acurable infectious disease. It is also aliver disease. A critical component ofmanaging HCV-related liver disease isto determine the patient’s severity ofliver fibrosis. Patients with advancedfibrosis should be regularly monitoredfor bleeding varices using esophagogastroduodenoscopy(EGD), and forascites and hepatocellular carcinoma(HCC) using ultrasound. Complicationsof liver disease require promptmanagement and aggressive followup.Knowing when to refer patients toa transplant center and doing so in atimely manner is crucial.Dr Sherman noted that the basicprinciples in understanding and managingHCV-related liver disease are asfollows:• Hepatic fibrosis is not reliablydiagnosed by ultrasoundexamination.• <strong>Liver</strong> fibrosis rates are not predictableor linear.• Progression from compensatedcirrhosis to decompensated liverdisease occurs in 5% of patientsper year.Dr Sherman is Gould professor of medicineand director of the Division of Digestive <strong>Disease</strong>sat the University of Cincinnati Collegeof Medicine in Cincinnati, OH.• Hepatocellular carcinoma developsin 1% to 2% of patients withHCV-related cirrhosis each year.<strong>Hepatitis</strong> C <strong>Virus</strong>–RelatedHepatic FibrosisReliable diagnosis of HCV-related advancedfibrosis or cirrhosis depends onliver biopsy (Figure 1). Ultrasound techniquesmay reveal a shrunken liver orevidence of portal hypertension but donot permit visualization of fibrosis orcirrhosis. Cirrhosis is a histologic diagnosisand is often confused with portalhypertension, which results from cirrhosis.However, not all portal hypertensionis caused by cirrhosis. The extentof fibrosis is classified into 4 stagesusing the Metavir schema. In stage 1,fibrous expansion can be observed insome portal areas. In stage 2, fibrousexpansion is observed in most portalareas, with occasional portal-to-portalbridging. Stage 3 fibrosis is characterizedby fibrous expansion of portal areaswith marked bridging, includingportal-to-portal and portal-to-centralbridging. Stage 4 fibrosis indicates cirrhosis,which is strictly defined as aliver lobule completely surrounded byscarring.<strong>Liver</strong> fibrosis progression rates arenot predictable or linear. They varywidely among patients with HCV infection,with rates being more rapid121CDEFigure 1. Progression of liver fibrosis asshown on a series of biopsy specimensand as classified by the Metavir schema.A: <strong>Liver</strong> with no fibrosis. B: Stage 1,fibrous expansion into some portal areas.C: Stage 2, fibrous expansion in most portalareas, with occasional portal-to-portalbridging. D: Stage 3, fibrous expansion ofportal areas with marked bridging, includingportal-to-portal and portal-to-central bridging.E: Stage 4, cirrhosis. Adapted withpermission from Gregory T. Everson, MD,University of Colorado Denver.

IAS–USATopics in Antiviral MedicineCase: A 48-Year-Old Man with HCV InfectionThe patient is a 48-year-old man with HCV infection, a history of 2 years ofinjection drug use from age 19 years to 21 years, and moderate social alcoholuse. The patient presents with fatigue and insomnia, with laboratory evaluationshowing alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 89 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase(AST) level of 67 U/L, bilirubin level of 1.5 mg/dL, alkaline phosphataselevel of 197 IU/L, hemoglobin level of 13.4 gm/dL, platelet count of 111,000/µL,HCV RNA level of 2.7 million IU/mL, and HCV genotype 1b. Right upper quadrantultrasound shows an echogenic liver consistent with fat or liver disease.Instead of undergoing biopsy for staging of fibrosis, the patient is started ona 3-drug regimen containing pegylated interferon alfa, ribavirin, and a directactingantiviral.After 12 weeks of treatment, virus is undetectable. The patient notes a 10-lbweight gain, and his wife complains that he sometimes appears drunk, thoughhe denies alcohol use. <strong>What</strong> is the best next step in the treatment of this patient:1. Prescribe an antidepressant? 2. Reassure the patient that he is experiencingcommon side effects of interferon alfa therapy? 3. Order a stat ultrasound?4. Suggest diet and exercise?Dr Sherman explained that an ultrasound will determine if the weight gainis associated with the development of ascites, and is thus the best next step.Although the severity of fibrosis in this patient is unknown, his workup prior totreatment initiation produced some findings that raise concern over the potentialfor decompensated liver disease, including a somewhat low platelet leveland the presence of fatigue and insomnia. Reversal of sleep patterns is a commonvery early symptom of hepatic encephalopathy.Weight gain is not expected in patients receiving interferon alfa; in fact,interferon alfa treatment is more commonly associated with anorexia andweight loss. Ultrasound reveals that the patient has ascites, indicating the presenceof advanced liver disease that became decompensated as a result of anti-HCV therapy.in those with cofactors for progressionthat include concurrent HIV infectionand excessive consumption of alcohol.Overall, some 15% to 33% of HCVinfectedpatients may exhibit mild ormoderate liver fibrosis over the courseof 40 or more years, whereas 20% to33% have disease that progresses to severecirrhosis or HCC over 20 or moreyears. Some patients, however, haveliver fibrosis that progresses to severedisease in as little as 3 or 4 years. 1In a sense, there are 2 timelines tokeep in mind when considering progressionof HCV-related liver disease.One timeline begins when a patientbecomes infected with HCV, markingthe onset of liver injury and a course ofprogression (in the absence of successfultreatment) that varies from severalyears to as long as 50 years. The secondtimeline begins at the onset of cirrhosis.Progression from compensatedasymptomatic cirrhosis to decompensatedliver disease occurs in approximately5% of HCV-infected patientsper year. In addition, HCC develops in1% to 2% of patients with HCV-relatedcirrhosis per year and eventuallyresults in symptomatic decompensateddisease.Cirrhosis and HepaticDecompensationApproximately 5% of HCV-infectedpatients with cirrhosis will have progressionto hepatic decompensationper year. Hepatic decompensation ischaracterized by: (1) ascites, which itselfmay be complicated by hepatorenalsyndrome (HRS), hepatic hydrothorax,and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis(SBP); (2) encephalopathy; (3) bleedingvarices; and (4) coagulopathy(indicated by a prothrombin time [PT]3 seconds above the control time or byan international normalized ratio [INR]greater than 1.5). Clinical staging ofcirrhosis was traditionally performedusing Child-Turcotte-Pugh scoring, ascoring system initially developed topredict a patient’s survival associatedwith portal shunt surgery. It was lateradapted to determine priority for livertransplantation. Scores are based onpresence and degree of abnormalitiesin bilirubin level, albumin level,INR, and on presence and severity ofhepatic encephalopathy and ascites.Cirrhosis staging under this system isdivided into class A, B, or C, with eachclass having an assigned 1- and 2-yearsurvival rate.The Child-Turcotte-Pugh scoring systemis not highly reliable for predictingmortality, however, and in recent yearshas been replaced by the more complexmodel for end-stage liver disease(MELD) scoring system. MELD scoringuses bilirubin, creatinine levels, and theINR to predict mortality risk and determinetiming of orthotopic liver transplantation.For example, for a patientwith end-stage liver disease, a creatininelevel of 1.6 mg/dL, bilirubin levelof 1.4 mg/dL, and an INR of 1.6, theMELD system will predict a 3-monthmortality risk of 18%.Most of the damage in decompensatedliver disease is related to alterationin blood flow through the liver. Theportal vein, which supplies the blood tothe liver, is formed by the confluenceof the superior and inferior mesentericveins and the splenic vein (Figure 2). Abuildup of fibrotic scar tissue in the livercan cause obstruction of blood flowinto the liver, causing blood to back upin the many vessels in the splanchniccirculation and resulting in numerousadverse consequences. The spleenbecomes enlarged and begins to filternonsenescent blood cells from the circulation,resulting in decreased levelsof platelets, red blood cells, and whiteblood cells. Decreased absorption offluids along the peritoneal surface alsooccurs because lymphatic drainage issupplemented by blood flow from theperitoneal space into the splanchniccirculation, resulting in ascites.A response to reduced blood flowinto the liver is the development ofcollateral vessels. These vessels grow122

<strong>Advanced</strong> <strong>Liver</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> Volume 19 Issue 3 August/September 2011<strong>Liver</strong>RightcolonSuperiormesentericveinSmallintestinePortalveinmostly in mucosal junction areas andcan result in the development of varicesin the esophagus, stomach, andrectum. Recanalization of vessels atthe umbilical vein occurs in some patients,driving the development of newvessels across the anterior abdomen(called caput medusae).Management of Ascites and itsComplicationsAscites can cause substantial pain anddiscomfort. Patients may ask for narcoticsfor pain relief, but narcotic useshould be avoided if possible by patientswho already have hepatic impairment.As noted, complications ofascites include HRS, hepatic hydrothorax,and SBP. Large ascites should alsobe relieved at first observation by tapping(also known as large volume paracentesis[LVP]). <strong>Every</strong> time the patientis admitted to the hospital and withevery change in health status (eg, worseningascites, development of bleedingvarices, or worsening hepatic encephalopathy),a diagnostic tap should beperformed. Tapping at the time of hospitaladmission is important because ahigh proportion of patients with ascitesSplenicveinSpleenInferiormesentericveinLeftcolonFigure 2. Splanchnic circulation. Arrows indicate direction ofblood flow.have SBP at the time ofadmission, whether or notfever or abdominal pain ispresent, and SBP is associatedwith marked morbidityand mortality.Tapping does not requirethat the patient besent to interventional radiologyfor a computedtomography (CT)–guidedtap. The procedure issafely performed in themidline subumbilical areawith the patient sitting ata 30-degree angle. For adiagnostic tap, the procedurecan be accomplishedin any patient with a 1.5-inch needle (and with a1.0-inch needle in most).Tapping is very safe regardlessof the patient’sdegree of coagulopathy,as the area beginning approximately2 cm belowthe umbilicus is relatively avascular.There is no need to have fresh frozenplasma or platelets on hand for theprocedure. Cell counts on the fluidshould be performed and fluid shouldbe injected directly into bedside culturebottles, because false-negative resultsoccur in 40% to 50% of cases in whichthe fluid is processed in the laboratoryrather than inoculated at bedside. Fortherapeutic taps, a large-gauge multiperforatedCaldwell or similar needleis used. Albumin replacement is requiredif the patient’s creatinine levelis elevated or if more than 5 L of fluidis removed.Management of ascites is diagrammedin Figure 3. At the initial visitfor patients with tense ascites, a largevolumetap is performed to relieve discomfortas quickly as possible. Patientsare placed on a sodium-restricted diet(maximum of 2 g/day) and diuretictherapy is initiated. The most effectiveapproach in diuretic treatment of ascitesis not to start with higher dosesof the rapid-acting agent furosemide,but rather to start with slower-actingtreatment such as the aldosterone antagonistspironolactone (50 mg/day) incombination with lower doses of furosemide(20 mg/day or 40 mg/day) orbumetanide (1 mg/day); doses are thentitrated upward at 2-week intervalsto maximum doses of 400 mg/day forspironolactone with 160 mg/day for furosemide,or 4 mg/day for bumetanide.When ascites is managed appropriately,the risk of progressing to refractoryascites is relatively low. When refractoryascites does occur, it is treatedwith repeated large-volume paracentesis.Consideration should be givento placement of a transjugular intrahepaticportosystemic shunt (TIPSS),which is successful in reducing ascitesin 60% to 70% of cases and eliminatingit in 20% to 30% of cases. Placementof TIPSS should only be performedby highly experienced interventionalradiologists after evaluation of the patientby a hepatologist. Finally, thepatient’s candidacy for liver transplantationshould be considered.Spontaneous Bacterial PeritonitisSBP is diagnosed by examining the asciticfluid: greater than 500 white bloodTenseParacentesisAscitesIf refractory ascites(10% of patients)NontenseSodium restriction (

IAS–USATopics in Antiviral Medicinecells/mL, greater than 250 polymorphonuclearcells/mL, or a positive cultureresult are indicative of SBP. Each definitionlisted is trumped by the next oneon the list. Treatment is with a 5-daycourse of intravenous cefotaxime orother cephalosporin. For beta-lactamallergy, ciprofloxacin may be used. Repeatparacentesis should be consideredat 48 hours to 72 hours after treatmentinitiation to check for white blood cellresponse; absence of response maysuggest the presence of an organismwith drug resistance or a complexpolymicrobial process that is not SBP.Albumin infusions should be given topatients with SBP, as they have beenshown to reduce mortality.One study showed a reduction in60-day mortality from 29% with cefotaximealone to 10% with cefotaximeplus 1.5 g/kg albumin administeredwithin 6 hours of SBP diagnosis, followedby 1.0 g/kg on day 3. 2 Antibioticprophylaxis with ciprofloxacin (750 mg/week) has been shown to prevent SBPin patients with ascites, with one classicstudy showing a 6-month incidenceof SBP of 4% with ciprofloxacin versus22% with placebo. 3 Alternative antibioticsfor prophylaxis are norfloxacin andtrimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.Hepatic HydrothoraxThe ascites complication of hepatichydrothorax results from a break inthe diaphragm that creates a ball-valveeffect such that each breath causesinflow of fluid from the abdomen intothe pleural space. The right pleuralspace is much more frequently involvedthan the left. Hepatic hydrothorax isnot to be confused with primary pleuraleffusion, and it is not to be treated withinsertion of a chest tube. Placement ofa chest tube in a patient with hepatichydrothorax results in a continuousloss of protein that rapidly rendersthe patient nutritionally depleted, makingliver transplantation impossible.Patients with hepatic hydrothorax mayor may not have visible ascites.Hepatic hydrothorax should be suspectedfor any patient with advancedliver disease and right-sided effusion.Hepatic hydrothorax should be managedby aggressive diuresis, pleuraltaps when needed, and immediateconsideration for liver transplantation.Patients requiring frequent pleural tapsmay gain additional MELD points onthe transplant list.VaricesP a t i e n t swith cirrhosismust bemonitoredfor the developmentof varices(Figure 4)and varicealbleedingusing EGD.Those withno varicesFigure 4. Gastroscopy imageof esophageal varices.should have repeat EGD performedat 3 years for well-compensated liverdisease and at 1 year for decompensateddisease. Patients with small varices(Grade 1) may begin nonselectivebeta-blocker prophylaxis. Patients withmedium (Grade 2, 5-10 mm) or large(Grade 3,>10 mm) varices who haveno red wales (evidence of impendingbleeding) should receive beta-blockertreatment; those with red wales shouldbe given beta-blocker treatment andconsidered for esophageal band ligation.Esophageal varices develop in35% to 80% of patients with cirrhosis,and bleeding occurs in 25% to 40% ofthose with varices. Of those with bleeding,30% to 50% die within 90 days. Ofthe 50% to 70% who survive an initialbleeding episode, 70% will experiencesubsequent bleeding.Hepatic EncephalopathyHepatic encephalopathy is classicallydetected by the observation of handasterixis (also known as liver flappingor flapping tremor). It is caused by theshunting of gut-derived neuroactivesubstances that cross the blood-brainbarrier; these substances are mostlynitrogen based and act as inhibitoryneurotransmitters. Survival probabilitiesfor patients with hepatic encephalopathyare 42% at 1 year and 23% at 3124years. Precipitating factors for hepaticencephalopathy include a high-proteindiet, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection(including SBP), vascular thrombosis,HCC, and poor adherence to hepaticencephalopathy treatment. Traditionaltreatments for hepatic encephalopathyinclude the use of lactulose or othernonabsorbable sugars, which causeosmotic diarrhea and movement of nitrogencompounds out of the gut, andthe use of antibiotics such as neomycinand metronidazole that change thegut flora.A recent phase III trial showed that,compared with placebo, the nonabsorbableantibiotic rifaximin administeredat 550 mg twice daily was associatedwith a statistically significantreduction in episodes of breakthroughhepatic encephalopathy in patients inremission from recurrent hepatic encephalopathy(breakthrough episodesoccurred in 22.1% of patients takingrifaximin vs 45.9% with placebo; P

<strong>Advanced</strong> <strong>Liver</strong> <strong>Disease</strong> Volume 19 Issue 3 August/September 2011Financial Disclosure: Dr Sherman hasserved as a consultant or scientific advisorto Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals,Inc, Genentech, Inc, Glaxo-SmithKline, Merck & Co, Inc, RegulusTherapeutics Inc, SciClone Pharmaceuticals,Three Rivers Pharmaceuticals,and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. He hasserved on data and safety monitoringboards and endpoint adjudication committeesfor MedPace, Inc, Pfizer Inc, andTibotec Therapeutics.References1. Afdhal NH. The natural history of hepatitisC. Semin <strong>Liver</strong> Dis. 2004;24(Suppl 2):3-8.2. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effectof intravenous albumin on renal impairmentand mortality in patients with cirrhosisand spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403-409.3. Rolachon A, Cordier L, Bacq Y, et al.Ciprofloxacin and long-term preventionof spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: resultsof a prospective controlled trial.Hepatology. 1995;22:1171-1174.4. Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, et al. Rifaximintreatment in hepatic encephalopathy.N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071-1081.Top Antivir Med. 2011;19(3):121-125©2011, IAS–USAEssential Management of HIV InfectionThis easy-to-readresource cardcontains currentrecommendationsfrom IAS–USApanels on:• When to initiateantiretroviral therapy• Selection of initialregimens• Patient monitoring• Changing therapy• A current list(as of Dec 2010) ofmutations associatedwith clinical resistanceto HIVOrder your copies today atwww.iasusa.org125