Recalcitrant Giant Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient With ...

Recalcitrant Giant Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient With ...

Recalcitrant Giant Molluscum Contagiosum in a Patient With ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

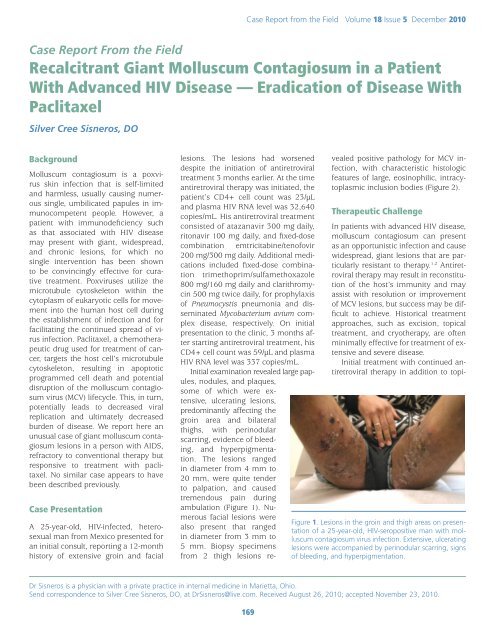

Case Report from the Field Volume 18 Issue 5 December 2010Case Report From the Field<strong>Recalcitrant</strong> <strong>Giant</strong> <strong>Molluscum</strong> <strong>Contagiosum</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Patient</strong><strong>With</strong> Advanced HIV Disease — Eradication of Disease <strong>With</strong>PaclitaxelSilver Cree Sisneros, DOBackground<strong>Molluscum</strong> contagiosum is a poxvirussk<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fection that is self-limitedand harmless, usually caus<strong>in</strong>g numerouss<strong>in</strong>gle, umbilicated papules <strong>in</strong> immunocompetentpeople. However, apatient with immunodeficiency suchas that associated with HIV diseasemay present with giant, widespread,and chronic lesions, for which nos<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>tervention has been shownto be conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>gly effective for curativetreatment. Poxviruses utilize themicrotubule cytoskeleton with<strong>in</strong> thecytoplasm of eukaryotic cells for movement<strong>in</strong>to the human host cell dur<strong>in</strong>gthe establishment of <strong>in</strong>fection and forfacilitat<strong>in</strong>g the cont<strong>in</strong>ued spread of virus<strong>in</strong>fection. Paclitaxel, a chemotherapeuticdrug used for treatment of cancer,targets the host cell’s microtubulecytoskeleton, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> apoptoticprogrammed cell death and potentialdisruption of the molluscum contagiosumvirus (MCV) lifecycle. This, <strong>in</strong> turn,potentially leads to decreased viralreplication and ultimately decreasedburden of disease. We report here anunusual case of giant molluscum contagiosumlesions <strong>in</strong> a person with AIDS,refractory to conventional therapy butresponsive to treatment with paclitaxel.No similar case appears to havebeen described previously.Case PresentationA 25-year-old, HIV-<strong>in</strong>fected, heterosexualman from Mexico presented foran <strong>in</strong>itial consult, report<strong>in</strong>g a 12-monthhistory of extensive gro<strong>in</strong> and faciallesions. The lesions had worseneddespite the <strong>in</strong>itiation of antiretroviraltreatment 3 months earlier. At the timeantiretroviral therapy was <strong>in</strong>itiated, thepatient’s CD4+ cell count was 23/µLand plasma HIV RNA level was 32,640copies/mL. His antiretroviral treatmentconsisted of atazanavir 300 mg daily,ritonavir 100 mg daily, and fixed-dosecomb<strong>in</strong>ation emtricitab<strong>in</strong>e/tenofovir200 mg/300 mg daily. Additional medications<strong>in</strong>cluded fixed-dose comb<strong>in</strong>ationtrimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole800 mg/160 mg daily and clarithromyc<strong>in</strong>500 mg twice daily, for prophylaxisof Pneumocystis pneumonia and dissem<strong>in</strong>atedMycobacterium avium complexdisease, respectively. On <strong>in</strong>itialpresentation to the cl<strong>in</strong>ic, 3 months afterstart<strong>in</strong>g antiretroviral treatment, hisCD4+ cell count was 59/µL and plasmaHIV RNA level was 337 copies/mL.Initial exam<strong>in</strong>ation revealed large papules,nodules, and plaques,some of which were extensive,ulcerat<strong>in</strong>g lesions,predom<strong>in</strong>antly affect<strong>in</strong>g thegro<strong>in</strong> area and bilateralthighs, with per<strong>in</strong>odularscarr<strong>in</strong>g, evidence of bleed<strong>in</strong>g,and hyperpigmentation.The lesions ranged<strong>in</strong> diameter from 4 mm to20 mm, were quite tenderto palpation, and causedtremendous pa<strong>in</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>gambulation (Figure 1). Numerousfacial lesions werealso present that ranged<strong>in</strong> diameter from 3 mm to5 mm. Biopsy specimensfrom 2 thigh lesions revealedpositive pathology for MCV <strong>in</strong>fection,with characteristic histologicfeatures of large, eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic, <strong>in</strong>tracytoplasmic<strong>in</strong>clusion bodies (Figure 2).Therapeutic ChallengeIn patients with advanced HIV disease,molluscum contagiosum can presentas an opportunistic <strong>in</strong>fection and causewidespread, giant lesions that are particularlyresistant to therapy. 1,2 Antiretroviraltherapy may result <strong>in</strong> reconstitutionof the host’s immunity and mayassist with resolution or improvementof MCV lesions, but success may be difficultto achieve. Historical treatmentapproaches, such as excision, topicaltreatment, and cryotherapy, are oftenm<strong>in</strong>imally effective for treatment of extensiveand severe disease.Initial treatment with cont<strong>in</strong>ued antiretroviraltherapy <strong>in</strong> addition to topi-Figure 1. Lesions <strong>in</strong> the gro<strong>in</strong> and thigh areas on presentationof a 25-year-old, HIV-seropositive man with molluscumcontagiosum virus <strong>in</strong>fection. Extensive, ulcerat<strong>in</strong>glesions were accompanied by per<strong>in</strong>odular scarr<strong>in</strong>g, signsof bleed<strong>in</strong>g, and hyperpigmentation.Dr Sisneros is a physician with a private practice <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternal medic<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> Marietta, Ohio.Send correspondence to Silver Cree Sisneros, DO, at DrSisneros@live.com. Received August 26, 2010; accepted November 23, 2010.169

International AIDS Society–USATopics <strong>in</strong> HIV Medic<strong>in</strong>eNormalKerat<strong>in</strong>ocyteHypergranulosis<strong>Molluscum</strong> Body(Henderson-Patterson Body)Figure 2. A section of a biopsy specimen from a thigh lesion reveal<strong>in</strong>ghistologic features characteristic of <strong>in</strong>fection with molluscumcontagiosum virus: large, eos<strong>in</strong>ophilic, <strong>in</strong>tracytoplasmic <strong>in</strong>clusionbodies (Henderson-Patterson bodies).cal liquid nitrogen cryotherapy was notassociated with any improvement <strong>in</strong>this patient’s lesions. Considerationwas given to us<strong>in</strong>g topical therapy withimiquimod or cidofovir, but because ofthe extent of the lesions, further topicaltreatment was expected to offer nobenefit. The decision was made to use<strong>in</strong>travenous paclitaxel because of thedrug’s potential ability to alter the lifecycleof the MCV via disruption of thehost’s cellular microtubule cytoskeletonk<strong>in</strong>etics.The patient was adm<strong>in</strong>istered “offlabel”treatment (ie, not approved bythe US Food and Drug Adm<strong>in</strong>istration[FDA]) with <strong>in</strong>travenous paclitaxel100 mg/m 2 (108 mg), which is a lowerdose than that recommended forthe treatment of ovarian, breast, ornon–small cell lung cancer. This dose(100 mg/m 2 ) has been used successfullyfor the treatment of AIDS-relatedKaposi sarcoma. There are no knowndrug-drug <strong>in</strong>teractions between thepatient’s antiretroviral drugs and paclitaxel.Paclitaxel was adm<strong>in</strong>istered <strong>in</strong>travenouslyon an outpatient basis every21 days for 4 cycles of therapy, alongwith standard pretreatment with famotid<strong>in</strong>e,dexamethasone, and diphenhydram<strong>in</strong>e.<strong>With</strong><strong>in</strong> 15 days of receiv<strong>in</strong>gthe first <strong>in</strong>jection, the patient experiencedrapid and complete resolution ofall sk<strong>in</strong> lesions, despite persistent immunesuppression(Figure 3).The patient cont<strong>in</strong>uedwith the 4scheduled cycles ofchemotherapy withoutany complicationsand rema<strong>in</strong>edfree of MCV diseaseat his last visit,7 months after the<strong>in</strong>itial consultation(Figure 4). Completeresolution of molluscumcontagiosumpersisted despite thepatient’s nonadherencewith his antiretroviraltherapyand an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>his plasma HIV RNAlevel to 10,600 copies/mL.The CD4+ cell count at the lastfollow-up visit was 145/µL.DiscussionMCV was first described <strong>in</strong> the medicalliterature <strong>in</strong> 1817 3 and <strong>in</strong> 1905,molluscum contagiosum was foundto be caused by a large DNA poxvirus(reviewed <strong>in</strong> reference 3 ). A majorbreakthrough came <strong>in</strong> 1996, whenthe genome of this tumorigenic viruswas sequenced. 4 <strong>With</strong> the eradicationof smallpox, MCV is now the onlymember of the poxvirus family thatcurrently causes substantial disease <strong>in</strong>humans. 5The study of MCV has been hamperedby the <strong>in</strong>ability to grow this virus<strong>in</strong> the laboratory and the lack of ananimal model to study the<strong>in</strong>fection. Vacc<strong>in</strong>ia virus hastherefore become the laboratoryprototype and moststudiedDNA poxvirus, andour knowledge of poxvirusbiology is derived largelyfrom studies of this virus. 6These studies show thatpoxviruses utilize the microtubulecytoskeleton with<strong>in</strong>the cytoplasm of eukaryoticcells for movement <strong>in</strong>to thehuman host cell dur<strong>in</strong>g establishmentof <strong>in</strong>fection andfor facilitat<strong>in</strong>g the cont<strong>in</strong>ued170spread of virus <strong>in</strong>fection. 7-9 Microtubulesare prote<strong>in</strong>-based structural componentsof the host cell cytoskeletonand are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g cellshape, <strong>in</strong>tracellular transport, and cellsignal<strong>in</strong>g, along with cell movement,reproduction, and division.Infection with MCV has a worldwide<strong>in</strong>cidence of as much as 8%. 10 Up to18% of patients with HIV <strong>in</strong>fection havesymptomatic molluscum contagiosum,an <strong>in</strong>cidence that <strong>in</strong>creases to 33% forpatients with CD4+ cell counts lessthan 100/µL. 11 In the United States from1990 to 1999, the estimated numberof physician visits for MCV <strong>in</strong>fectionwas 280,000 per year. 12 Acquisition ofthe virus follows contact with <strong>in</strong>fectedpersons or contam<strong>in</strong>ated objectsand sources such as towels, sponges,swimm<strong>in</strong>g pools, public baths, tattoo<strong>in</strong>struments, gymnasium equipment,<strong>in</strong>struments used <strong>in</strong> beauty salons, andpublic benches. 3,11,13 The estimated <strong>in</strong>cubationperiod ranges from 14 daysto 6 months. 14 Three dist<strong>in</strong>ct diseasepatterns are observed <strong>in</strong> 3 differentpatient populations: children who aregenerally healthy; adults who are generallyhealthy; and immunocompromisedchildren and adults. 11MCV <strong>in</strong>fection is most common <strong>in</strong>children who become <strong>in</strong>fected eitherdirectly through sk<strong>in</strong>-to-sk<strong>in</strong> contactor <strong>in</strong>directly through sk<strong>in</strong> contact withcontam<strong>in</strong>ated objects. In adults, MCV<strong>in</strong>fection is considered primarily asexually transmitted disease. In immunocompetentchildren and adults, MCV<strong>in</strong>fection is a harmless, self-limiteddisease that produces a papular erup-Figure 3. Photograph of the patient 15 days after the firstadm<strong>in</strong>istration of <strong>in</strong>travenous paclitaxel, show<strong>in</strong>g resolutionof all sk<strong>in</strong> lesions.

Case Report from the Field Volume 18 Issue 5 December 2010Figure 4. Photograph of the patient 4 months after thefirst adm<strong>in</strong>istration of paclitaxel, show<strong>in</strong>g susta<strong>in</strong>edresolution of disease despite the patient’s nonadherenceto his antiretroviral regimen.tion of numerous benign, umbilicatedtumors. 14 The <strong>in</strong>dividual tumors aresmall, sk<strong>in</strong> colored, firm, smooth, andpa<strong>in</strong>less, and they have a central whitecaseous plug. Individual lesions healspontaneously and are seldom presentlonger than 2 months. 11 In patients whoare severely immumocompromised orhave advanced HIV disease and lowCD4+ cell counts, the tumors may becomea widespread, chronic opportunistic<strong>in</strong>fection 2,15 characterized by giant,nodular, 1 necrotic, 16 symptomatic,and disfigur<strong>in</strong>g lesions, with secondary<strong>in</strong>fection. 17 In these patients, theimpaired cell-mediated immunity can<strong>in</strong>terfere with the resolution of diseaseand the tumors may be very resistantto therapy. 18 In immunocompromisedpatients, the differential diagnosis ofMCV disease is important to consider;it can <strong>in</strong>clude atypical mycobacterial<strong>in</strong>fection, cryptococcosis, pyogenicgranuloma, basal cell carc<strong>in</strong>oma, histoplasmosis,penicill<strong>in</strong>osis, pneumocystosis,and keratoacanthoma. 19Little data exist with regard to thebest treatment of MCV <strong>in</strong>fection. Nos<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>tervention has been shown tobe conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>gly effective, and no reliableevidence-based recommendationsexist. 14In healthy adults and children, treatmentis not necessary for recovery, andawait<strong>in</strong>g spontaneous resolution is apotential management strategy. Treatment,when used, is <strong>in</strong>tended to hastenthis process. Three broad categories oftreatment options have been used historicallyfor MCV disease: physical destructionof the tumor, topicaltreatment, and systemic treatment.Cryotherapy, curettage,and evisceration are examplesof destructive therapy. Treatmentmay be pa<strong>in</strong>ful and result<strong>in</strong> scarr<strong>in</strong>g. 14 Topical treatments<strong>in</strong>clude cantharid<strong>in</strong>,potassium hydroxide, podophyllotox<strong>in</strong>,tret<strong>in</strong>o<strong>in</strong>, liquefiedphenol, imiquimod, and cidofovir.Systemic treatments thathave been tried <strong>in</strong>clude cidofovirand cimetid<strong>in</strong>e. 14,20Traditional antiviral drugsare directed aga<strong>in</strong>st the prote<strong>in</strong>sand functional pathwaysof the virus itself. Because poxvirusesrely on cellular pathways to propagate,another possible antiviral treatmentapproach is to direct treatment that<strong>in</strong>terferes with the viral functions thatare dependent on the functional mach<strong>in</strong>eryof the cell. 21 The microtubulecytoskeleton pathway plays a role <strong>in</strong>the lifecycle of poxviruses 7 and maythus represent a new target for poxvirustherapy. 21Paclitaxel targets the host cell’s microtubulecytoskeleton. The drug wasdiscovered <strong>in</strong> 1964 and is derived fromthe bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxusbrevifolia). Paclitaxel is approved by theUS FDA as a chemotherapeutic drug forthe treatment of ovarian cancer, breastcancer, non–small cell lung cancer,prostate cancer, and AIDS-related Kaposisarcoma. 22 It belongs to the classof drugs called taxanes, which are anticancerdrugs that have validated theconcept of microtubules as effectivecancer chemotherapeutic targets. 23Cells treated with paclitaxel producetoo many microtubules and as a resultare unable to coord<strong>in</strong>ate cell division;they die after cont<strong>in</strong>ued attempts toreplicate their DNA without the abilityto divide. 24The rapid clearance of disease <strong>in</strong>this case supports the possibility thattreatment with <strong>in</strong>travenous paclitaxelmight disrupt the MCV lifecycle, therebyresult<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> decreased viral replicationand ultimately, decreased burdenof disease. Further cl<strong>in</strong>ical studies arerecommended to fully characterize thenature of this response.F<strong>in</strong>ancial Disclosure: Dr Sisneros has servedas a scientific advisor and paid lecturer forGilead Sciences, Inc.References1. Vozmediano JM, Manrique A, PetragliaS, Romero MA, Nieto I. <strong>Giant</strong> molluscumcontagiosum <strong>in</strong> AIDS. Int J Dermatol.1996;35:45-47.2. Gona P, Van Dyke RB, Williams PL, et al.Incidence of opportunistic and other <strong>in</strong>fections<strong>in</strong> HIV-<strong>in</strong>fected children <strong>in</strong> the HAARTera. JAMA. 2006;296:292-300.3. Kauffman CL and Beatty CN. <strong>Molluscum</strong>contagiosum. eMedic<strong>in</strong>e Dermatology Website. July 23, 2010. http://emedic<strong>in</strong>e.medscape.com/article/1132908-overview. Updated July23, 2010. Accessed November 29, 2010.4. Senkevich TG, Bugert JJ, Sisler JR, Koon<strong>in</strong>EV, Darai G, Moss B. Genome sequence of ahuman tumorigenic poxvirus: prediction ofspecific host response-evasion genes. Science.1996;273:813-816.5. Krathwohl MD, Hromas R, Brown DR,Broxmeyer HE, Fife KH. Functional characterizationof the C---C chemok<strong>in</strong>e-like moleculesencoded by molluscum contagiosumvirus types 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.1997;94:9875-9880.6. Harrison SC, Alberts B, Ehrenfeld E, et al.Discovery of antivirals aga<strong>in</strong>st smallpox. ProcNatl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11178-11192.7. Ploubidou A, Moreau V, Ashman K, ReckmannI, González C, Way M. Vacc<strong>in</strong>ia virus <strong>in</strong>fectiondisrupts microtubule organization and centrosomefunction. EMBO J. 2000;19:3932-3944.8. Holl<strong>in</strong>shead M, Rodger G, Van Eijl H, etal. Vacc<strong>in</strong>ia virus utilizes microtubules formovement to the cell surface. J Cell Biol.2001;154:389-402.9. Laliberte JP, Moss B. Lipid membranes <strong>in</strong>poxvirus replication. Viruses. 2010;2:972-986.10. Billste<strong>in</strong> SA, Mattaliano VJ, Jr. The "nuisance"sexually transmitted diseases: molluscumcontagiosum, scabies, and crab lice. MedCl<strong>in</strong> North Am. 1990;74:1487-1505.11. Crowe MA. <strong>Molluscum</strong> contagiosum. eMedic<strong>in</strong>ePediatrics Web site. April 26, 2010. http://emedic<strong>in</strong>e.medscape.com/article/910570-overview.Updated April 26, 2010. Accessed November29, 2010.12. Mol<strong>in</strong>o AC, Fleischer AB, Jr., FeldmanSR. <strong>Patient</strong> demographics and utilization ofhealth care services for molluscum contagiosum.Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:628-632.171

International AIDS Society–USATopics <strong>in</strong> HIV Medic<strong>in</strong>e13. Postlethwaite R. <strong>Molluscum</strong> contagiosum.Arch Environ Health. 1970;21:432-452.14. van der Wouden JC, van der Sande R,van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Berger M, Butler C,Kon<strong>in</strong>g S. Interventions for cutaneous molluscumcontagiosum. Cochrane DatabaseSyst Rev. 2009;CD004767.15. Schwartz JJ, Myskowski PL. <strong>Molluscum</strong>contagiosum <strong>in</strong> patients with human immunodeficiencyvirus <strong>in</strong>fection. A review oftwenty-seven patients. J Am Acad Dermatol.1992;27:583-588.16. Baxter KF, Highet AS. Topical cidofovirand cryotherapy--comb<strong>in</strong>ation treatment forrecalcitrant molluscum contagiosum <strong>in</strong> a patientwith HIV <strong>in</strong>fection. J Eur Acad DermatolVenereol. 2004;18:230-231.17. L<strong>in</strong> HY, L<strong>in</strong>n G, Liu CB, Chen CJ, Yu KJ.An immunocompromised woman with severemolluscum contagiosum that respondedwell to topical imiquimod: a case reportand literature review. J Low Genit Tract Dis.2010;14:134-135.18. Hivnor C, Shepard JW, Shapiro MS, VittorioCC. Intravenous cidofovir for recalcitrantverruca vulgaris <strong>in</strong> the sett<strong>in</strong>g of HIV. ArchDermatol. 2004;140:13-14.19. Hogan MT. Cutaneous <strong>in</strong>fections associatedwith HIV/AIDS. Dermatol Cl<strong>in</strong>.2006;24:473-95, vi.20. Meadows KP, Tyr<strong>in</strong>g SK, Pavia AT, RallisTM. Resolution of recalcitrant molluscumcontagiosum virus lesions <strong>in</strong> humanimmunodeficiency virus-<strong>in</strong>fected patientstreated with cidofovir. Arch Dermatol.1997;133:987-990.21. Yang H, Kim SK, Kim M, et al. Antiviralchemotherapy facilitates control ofpoxvirus <strong>in</strong>fections through <strong>in</strong>hibition ofcellular signal transduction. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Invest.2005;115:379-387.22. McEvoy GK, Miller J, Litvak K, eds. AHFSDrug Information 2004. Bethesda, MD: AmericanSociety of Health-System Pharmacists;2004:1100-1111.23. Zhou J, Giannakakou P. Target<strong>in</strong>g microtubulesfor cancer chemotherapy. Curr MedChem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:65-71.24. The discovery of camptothec<strong>in</strong> and Taxol®.American Chemical Society. Published2007. http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/landmarks/taxol/tax.html. Accessed November29, 2010.Top HIV Med. 2010;18(5):169-172©2010, International AIDS Society–USADermatologicManifestations ofHIV Infection <strong>in</strong> AfricaResource CardCards Available NowBased on the Topics <strong>in</strong> HIV Medic<strong>in</strong>earticle from February/March 2010,this fold<strong>in</strong>g card is available onrequest by visit<strong>in</strong>g www.iasusa.org.Included are brief descriptions ofselected dermatologic manifestations,along with their differential diagnosesand treatment options.172