Scoliosis - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

Scoliosis - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

Scoliosis - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

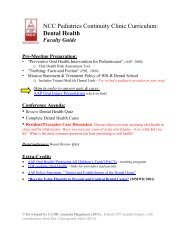

<strong>NCC</strong> <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> Continuity Clinic Curriculum:Crooked Backs: <strong>Scoliosis</strong> for General <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong>Goals & Objectives:1. Show how to physical screen for scoliosis2. Calcul<strong>at</strong>e a Cobb Angle and Risser Stage from an x-ray3. Tell your preceptor when to refer a p<strong>at</strong>ient with scoliosis.Pre-Meeting Prepar<strong>at</strong>ion:• Read the 2 articleso <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> In Review article on <strong>Scoliosis</strong>o Adolescent Idiop<strong>at</strong>hic <strong>Scoliosis</strong>: Radiologic Decision-Making inthe AAFP (May 2002)• Complete the <strong>Scoliosis</strong> Crossword Puzzle.Conference Agenda:• Answer the questions as a group.• Demonstr<strong>at</strong>e your technique for calcul<strong>at</strong>ing Cobb Angles using the imagesprovidedExtra-Credit:• Use your computer based radiography software to calcul<strong>at</strong>e Cobb Angles on a p<strong>at</strong>ient• Find out something about the ‘Adams’ of the Adams Forward Bend Test or ‘Risser’• Answer the board questions© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

How to Calcul<strong>at</strong>e a Cobb Angle-------------- cut here for a handy protractor to calcul<strong>at</strong>e your angles ---------------------------© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

Calcul<strong>at</strong>e a Cobb Angle for the following images. Show your work.© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

<strong>Scoliosis</strong> Crossword Puzzle© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

in briefIn Brief<strong>Scoliosis</strong>Jacob J. Rosenberg, MD, FAAP, FRCPCVaughan Pedi<strong>at</strong>ric ClinicWoodbridge, Ontario, CanadaAuthor DisclosureDrs Rosenberg and Adam havedisclosed no financial rel<strong>at</strong>ionshipsrelevant to this In Brief. Thiscommentary does not contain adiscussion of an unapproved/investig<strong>at</strong>ive use of a commercialproduct/device.Screening for Idiop<strong>at</strong>hic <strong>Scoliosis</strong> inAdolescents. Richards S, Vitale M.J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:195–198Screening for Adolescent Idiop<strong>at</strong>hic<strong>Scoliosis</strong>. Policy St<strong>at</strong>ement. US PreventiveServices Task Force. JAMA.1993;269:2664–2666<strong>Scoliosis</strong> is a l<strong>at</strong>eral curv<strong>at</strong>ure of thespine. Although it can result from avariety of causes, more than 60% ofall cases are considered idiop<strong>at</strong>hic.Eighty percent of idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosisoccurs in adolescents, while infantilescoliosis (ages 0 to 3 y) and juvenilescoliosis account for 1% and 12% to21% of cases, respectively. Nonidiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis, about one third ofall cases, is associ<strong>at</strong>ed with underlyingneurologic disorders (cerebral palsy,myelomeningocele, tethered cord syndrome,spinal muscular <strong>at</strong>rophy, syringomyelia,muscular dystrophy, Friedrich<strong>at</strong>axia, Riley-Day syndrome), musculoskeletaldisorders (leg length discrepancy,developmental dysplasia of thehip, osteogenesis imperfecta, Klippel-Feil syndrome), and connective tissuedisorders (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, homocystinuria).The primary tasks for the clinicianwhen scoliosis is diagnosed are to:1) determine whether the condition isidiop<strong>at</strong>hic or if there is an underlyingcause and 2) measure the curv<strong>at</strong>ure andascertain whether it is likely to worsen.The major factors influencing the progressionof the curve are sex, potentialfor future growth, and the magnitudeof the curve <strong>at</strong> the time of diagnosis.Mild curv<strong>at</strong>ure of the spine (10 to 30degrees) occurs equally in males andfemales, but 80% to 90% of p<strong>at</strong>ientswho have curves gre<strong>at</strong>er than 30 degreesare females. The more potentialfor growth, the gre<strong>at</strong>er is the risk th<strong>at</strong>the curv<strong>at</strong>ure will worsen. Growth potentialcan be determined by assessingSexual M<strong>at</strong>urity R<strong>at</strong>ing (SMR) on physicalexamin<strong>at</strong>ion and Risser grading onradiography. Risser grading is a measurementof the ossific<strong>at</strong>ion of the iliacapophysis: 0 is no ossific<strong>at</strong>ion, grade 1is up to 25% ossific<strong>at</strong>ion, grade 2 is 26%to 50% ossific<strong>at</strong>ion, grade 3 is 51% to75% ossific<strong>at</strong>ion, grade 4 is 76% to99% ossific<strong>at</strong>ion, and grade 5 is completeossific<strong>at</strong>ion. The lower the SMRstage and Risser grade, the gre<strong>at</strong>er isthe risk th<strong>at</strong> the scoliosis will progress.The magnitude of the curve is measuredon radiograph by determining the Cobbangle: an angle derived from the positionsof the most tilted vertebrae aboveand below the apex of the curve. Thegre<strong>at</strong>er the Cobb angle, the higher isthe risk of progression.The adverse effects of progressivescoliosis include cosmetic deformitywith its potential for social and psychologicalconsequences both during childhoodand adulthood; the financial costsof therapy; and although the associ<strong>at</strong>ionis controversial before adulthood,the development of chronic back pain.With extreme curv<strong>at</strong>ures (possibly 50degrees, certainly 75 degrees), scoliosiscan lead to respir<strong>at</strong>ory compromiseas well. Because scoliosis often occurswithout symptoms, the concept of universalscreening during the adolescentyears has been advoc<strong>at</strong>ed, both throughscreening in school and by routine examin<strong>at</strong>ionduring health supervisionvisits. School-based screening was begunin 1984 and endorsed by the AmericanAcademy of Orthopaedic Surgeons(AAOS), with the underlying convictionth<strong>at</strong> early detection of scoliosis whenthe deformity may have gone unnoticedcan lead to nonoper<strong>at</strong>ive tre<strong>at</strong>mentth<strong>at</strong> can have a positive impact onlong-term outcome.The primary screening test is thephysical examin<strong>at</strong>ion, which includesvisual inspection of the back with thep<strong>at</strong>ient standing upright and the Adamsforward bending test. With this test,the p<strong>at</strong>ient stands with feet togetherand knees straight and slowly bendsforward from the waist, as if to touchthe toes, allowing the arms to hangwith palms touching. The examiner,with eyes level with the back, looks forasymmetry of one scapula or one sideof the rib cage or the paraspinousmuscles more prominent than the other.A scoliometer, which is a vari<strong>at</strong>ion of acarpenter’s level, is useful for quantifyingthe degree of chest deformity, bothin the initial evalu<strong>at</strong>ion and in followingprogression of the curve. The degreemeasurements noted on the scoliometerare not equivalent to the degreesof the Cobb angle. Many clinicians usea scoliometer measurement of 6 to 7degrees or more as an indic<strong>at</strong>ion forobtaining radiographs. If scoliosis is<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.32 No.9 September 2011 397Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> USUHS LRC on April 21, 2012

in briefsuspected based on physical examin<strong>at</strong>ionfindings, a radiograph of the backshould be considered to measure thedegree of curv<strong>at</strong>ure (ie, the Cobb angle)and the Risser grade.Screening is not without its difficulties.Almost one third of p<strong>at</strong>ients whoare identified as having scoliosis byschool screening programs are found onfurther investig<strong>at</strong>ion to have no abnormality.In 1996, the United St<strong>at</strong>es PreventiveServices Task Force (USPSTF)concluded th<strong>at</strong> evidence was insufficientto make a recommend<strong>at</strong>ion for oragainst screening. However, the USPSTFchanged its position in 2004, recommendingagainst routine screening ofasymptom<strong>at</strong>ic adolescents for idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis because of the low predictivevalue, the rel<strong>at</strong>ively small percentageof children whose curves progress, andthe possibility of screening leading tounnecessary tre<strong>at</strong>ment, including theuse of braces. This change in positionwas influenced by a study in the Netherlandsth<strong>at</strong> showed no significant reductionin the need for scoliosis surgery<strong>at</strong>tributable to screening. P<strong>at</strong>ientsdetected by screening were significantlyyounger <strong>at</strong> diagnosis than p<strong>at</strong>ients whowere detected otherwise. Further, p<strong>at</strong>ientsdetected by routine screening hadadditional years of concern about theirscoliosis, and although they were morelikely to be tre<strong>at</strong>ed with bracing, they didnot have better final outcomes.The USPSTF urges th<strong>at</strong> instead ofroutine screening, clinicians shouldevalu<strong>at</strong>e scoliosis when it presents as asymptom or is found incidentally. Ifscoliosis screening is undertaken, theAAOS, <strong>Scoliosis</strong> Research Society, Pedi<strong>at</strong>ricOrthopaedic Society of NorthAmerica, and the American Academyof <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> (AAP) agree th<strong>at</strong> girlsshould be screened twice, <strong>at</strong> ages 10 and12 years, and boys once <strong>at</strong> 13 or 14 years.The AAP Bright Futures recommends examin<strong>at</strong>ionof the back <strong>at</strong> adolescenthealth supervision visits, which can includethe forward bend test.Tre<strong>at</strong>ment of scoliosis begins with afocused history and physical examin<strong>at</strong>ion,looking for an underlying causeof the curv<strong>at</strong>ure. In cases of idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis, intervention is aimed <strong>at</strong> preventing,or <strong>at</strong> least minimizing, cosmeticdeformity, respir<strong>at</strong>ory compromise,and significant pain. Exercise therapyhas been advoc<strong>at</strong>ed, but there is noevidence th<strong>at</strong> it reverses or even slowsthe progression of curv<strong>at</strong>ure. Bracinguses mechanical force to straightenthe spine, but whether it can reliablyprevent progression of the curve isless certain. One of the major issueswith brace therapy is the difficulty th<strong>at</strong>adolescents have in adhering to theregimen, with one study showing only15% compliance and reporting th<strong>at</strong>most p<strong>at</strong>ients wore their braces only65% of the recommended time. Ingeneral, bracing can be considered forcurves between 20 and 40 degrees inp<strong>at</strong>ients who still have significantgrowth potential. With skeletal m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion,as evidenced by a high Rissergrading, such curves should not needintervention. For curves gre<strong>at</strong>er than40 degrees, surgery using spinal fusionand any of a variety of instrument<strong>at</strong>iontechniques is the generally recommendedtre<strong>at</strong>ment.Comment: Two controversial questionsfor the pedi<strong>at</strong>rician surroundingscoliosis are whether to screen routinely,and in a child complaining ofbackache who has a curve, how likelyis scoliosis an explan<strong>at</strong>ion for the pain.The problem with routine screening isth<strong>at</strong> it is poorly predictive of p<strong>at</strong>ientswho will ultim<strong>at</strong>ely benefit from intervention.Most children identified byroutine screening in early adolescenceeither do not have scoliosis or havecurves th<strong>at</strong> require no tre<strong>at</strong>ment. Thesechildren will more than likely be irradi<strong>at</strong>ed<strong>at</strong> least once, if not serially, andwill face anxiety over whether theywill become “deformed” or need surgery.The argument for routine screeningbecomes more difficult in the absenceof solid evidence th<strong>at</strong> earlybracing really retards curve progression.If it does not, curves destined to warrantsurgery will progress despite earlyscreening.As for back pain and scoliosis, althoughlong-term follow-up studiessupport the associ<strong>at</strong>ion of scoliosis andchronic back pain in adulthood, theevidence among pedi<strong>at</strong>ric p<strong>at</strong>ients isless clear. When a child or adolescentwho has scoliosis complains of backpain, consider<strong>at</strong>ion should be given tothe possibility of the scoliosis not beingidiop<strong>at</strong>hic, an underlying musculoskeletalor neurologic cause producingthe pain, or the back pain being unrel<strong>at</strong>edto the scoliosis. Who said practicingmedicine is easy?Henry M. Adam, MDEditor, In BriefParent Resources from the AAP <strong>at</strong> HealthyChildren.orgThe reader is likely to find m<strong>at</strong>erial to share with parents th<strong>at</strong> is relevant to this article byvisiting this link: http://www.healthychildren.org/english/health-issues/conditions/orthopedic/pages/scoliosis.aspx.398 <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.32 No.9 September 2011Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> USUHS LRC on April 21, 2012

RADIOLOGIC DECISION-MAKINGAdolescent Idiop<strong>at</strong>hic <strong>Scoliosis</strong>:Radiologic Decision-MakingK. ALLEN GREINER, M.D., M.P.H., University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KansasAdolescent onset of severe idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis has traditionally been evalu<strong>at</strong>edusing standing posteroanterior radiographs of the full spine to assess l<strong>at</strong>eral curv<strong>at</strong>urewith the Cobb method. The most tilted vertebral bodies above and belowthe apex of the spinal curve are used to cre<strong>at</strong>e intersecting lines th<strong>at</strong> give the curvedegree. This definition is controversial, and p<strong>at</strong>ients do not exhibit clinically significantrespir<strong>at</strong>ory symptoms with idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis until their curves are 60 to 100degrees. There is no difference in the prevalence of back pain or mortality betweenp<strong>at</strong>ients with untre<strong>at</strong>ed adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis and the general popul<strong>at</strong>ion.Therefore, many p<strong>at</strong>ients referred to physicians for evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of scoliosis do notneed radiographic evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, back examin<strong>at</strong>ions, or tre<strong>at</strong>ment. Consensus recommend<strong>at</strong>ionsfor popul<strong>at</strong>ion screening, evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, and tre<strong>at</strong>ment of this disorder bymedical organiz<strong>at</strong>ions vary widely. Recent studies cast doubt on the clinical valueof school-based screening programs. (Am Fam Physician 2002;65:1817-22. Copyright©2002 American Academy of Family Physicians.)Coordin<strong>at</strong>ors of thisseries are Mark Meyer,M.D., University ofKansas School of Medicine,Kansas City, Kan.,and <strong>Walter</strong> Forred,M.D., University ofMissouri–Kansas CitySchool of Medicine,Kansas City, Mo.The editors of AFPwelcome the submissionof manuscriptsfor the RadiologicDecision-Making series.Send submissions toJay Siwek, M.D., followingthe guidelinesprovided in “Inform<strong>at</strong>ionfor Authors.”Adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosisis l<strong>at</strong>eral and rot<strong>at</strong>ional spinalcurv<strong>at</strong>ure in the absence ofassoci<strong>at</strong>ed congenital or neurologicabnormalities. Longitudinalstudies 1,2 estim<strong>at</strong>e the prevalence ofidiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis as 2 percent of the adolescentpopul<strong>at</strong>ion, using a definition of a spinalcurve gre<strong>at</strong>er than 10 degrees. 3 However, clinicallysignificant curves in the range of 40 to100 degrees are rare. Controversy surroundsclinical recommend<strong>at</strong>ions for evalu<strong>at</strong>ing andmanaging p<strong>at</strong>ients with a wide range of curvesizes. Recent deb<strong>at</strong>e has centered on the valueof school-based screening programs. 4School-Based ScreeningSchool-based scoliosis screening programsare currently mand<strong>at</strong>ed in 26 st<strong>at</strong>es, withmany other st<strong>at</strong>es having voluntary programs.Several studies 1,5,6 and the 1996 U.S.Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)Report 7 question the value and cost-effectivenessof these programs. Few children referredfor medical evalu<strong>at</strong>ion from these programsreceive any form of therapy. 8 Furthermore,the long-term health outcomes for tre<strong>at</strong>edversus untre<strong>at</strong>ed p<strong>at</strong>ients with scoliosis havenot been well studied, making it difficult todetermine the health impact of these screeningprograms. P<strong>at</strong>ients with severe curves arenot difficult to diagnose. Although someadvoc<strong>at</strong>es still recommend school-basedscreening of adolescents, there is no evidenceto support these programs. The AmericanAcademy of <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> recommends screening<strong>at</strong> physician visits. The USPSTF and theCanadian Task Force on the Periodic HealthExamin<strong>at</strong>ion st<strong>at</strong>e th<strong>at</strong> insufficient evidenceexists to support universal school-basedscreening. Radiographic decision-makingskills will help primary care physicians evalu<strong>at</strong>esevere scoliosis accur<strong>at</strong>ely.EtiologyThe etiology of adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosisis believed to be multifactorial, includinggenetic factors. One study 9 showed a 73 percentphenotypic concordance of scoliosis inmonozygotic twins. Eleven percent of firstdegreerel<strong>at</strong>ives of p<strong>at</strong>ients with scoliosis areaffected. Inheritance of scoliosis varies, andno single p<strong>at</strong>tern of genetic transmission hasbeen accepted. The physiologic causes of scoliosishave not been elucid<strong>at</strong>ed. Muscular,nervous system, hormonal, and connectivetissue defects have been noted in subgroupsof p<strong>at</strong>ients with scoliosis, but these abnor-MAY 15, 2002 / VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 1817

A p<strong>at</strong>ient’s skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity can determine the risk of progressionof more severe scoliosis curves.23 4 51The Authormalities may be a result of the disorder r<strong>at</strong>herthan a cause. 10K. ALLEN GREINER, M.D., M.P.H., is assistant professor of family medicine <strong>at</strong> the Universityof Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, where he also received his medicaldegree and masters of public health degree. He completed a residency in family medicineand a fellowship in primary care <strong>at</strong> the University of Kansas Medical Center.Address correspondence to K. Allen Greiner, M.D., M.P.H., Department of Family Medicine,University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Blvd., Kansas City, KS66160-7370 (e-mail: agreiner@kumc.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.RightLeftFIGURE 1. Ossific<strong>at</strong>ion of the iliac apophysisstarts <strong>at</strong> the anterior superior iliac spine andprogresses posteromedially. The iliac crest isdivided into quadrants, and the stage ofm<strong>at</strong>urity is design<strong>at</strong>ed as the number of ossifiedquadrants. For example, 50 percent ossifiedis a Risser grade 2. On the an<strong>at</strong>omic left(right side of the figure), all quadrants areossified and the apophysis is fused to the iliaccrest, for a Risser grade 5.N<strong>at</strong>ural HistoryStudies 11-13 of adolescent-onset scoliosishave demonstr<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> p<strong>at</strong>ients with scoliosisshow minimal progression in the magnitudeof the curve in adulthood if the curve is lessthan 30 degrees <strong>at</strong> skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity. Althoughcurves in different regions of the spineprogress differently, curves measuring 40 to50 degrees <strong>at</strong> skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity progress anaverage of 10 to 15 degrees during a normallifetime, while curves measuring gre<strong>at</strong>er than50 degrees <strong>at</strong> skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity progress <strong>at</strong> ar<strong>at</strong>e of approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 1 to 2 degrees per year. 11Because of the controversy surrounding idealtre<strong>at</strong>ment str<strong>at</strong>egies for p<strong>at</strong>ients with moder<strong>at</strong>ecurves, estim<strong>at</strong>ion of curve progressioncan aid in clinical management and counselingp<strong>at</strong>ients’ families about prognoses.Estim<strong>at</strong>ion of skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity can bedetermined by assessing the epiphyseal st<strong>at</strong>uson wrist radiographs, the Risser sign, Tannerstages, progressive sitting and standing heightmeasurements, and age <strong>at</strong> menarche.Risser sign is defined by the amount of calcific<strong>at</strong>ionpresent in the iliac apophysis andmeasures the progressive ossific<strong>at</strong>ion fromanterol<strong>at</strong>erally to posteromedially. A Rissergrade of 1 signifies up to 25 percent ossific<strong>at</strong>ionof the iliac apophysis, proceeding tograde 4, which signifies 100 percent ossific<strong>at</strong>ion(Figure 1).A Risser grade of 5 means theiliac apophysis has fused to the iliac crest after100 percent ossific<strong>at</strong>ion. Children usually progressfrom a Risser grade 1 to a grade 5 over <strong>at</strong>wo-year period. One study 8 found th<strong>at</strong> imm<strong>at</strong>urep<strong>at</strong>ients (Risser grades 0 and 1) with aspinal curv<strong>at</strong>ure measuring 20 to 29 degreeshad a 68 percent probability of progression of6 degrees or more during remaining growth.P<strong>at</strong>ients closer to m<strong>at</strong>urity (Risser grades 2 to4) and with the same degree of scoliosis had a23 percent probability of progression. 8Curves measuring 5 to 19 degrees in imm<strong>at</strong>urep<strong>at</strong>ients had a 22 percent probability ofprogression, while small curves in m<strong>at</strong>urep<strong>at</strong>ients had only a 1.6 percent probability ofprogression. 8If other clinical markers of m<strong>at</strong>urity suchas Tanner staging or age <strong>at</strong> menarche are notconsistent with the Risser grade, curve progressionmay proceed <strong>at</strong> a different r<strong>at</strong>e. Thus,ILLUSTRATION BY RENEE L. CANNON1818 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 / MAY 15, 2002

<strong>Scoliosis</strong>multiple measures of m<strong>at</strong>urity are importantto the clinical assessment of these p<strong>at</strong>ients.Although a recent study 14 showed anincreased incidence of precocious puberty, theaverage female reaches a Tanner stage 1 <strong>at</strong> 11years of age, the beginning of the growth spurt<strong>at</strong> 11.5 years of age, a Risser grade 1 <strong>at</strong> 12 yearsof age, and has an onset of menarche between12 and 13 years of age. A female p<strong>at</strong>ient whom<strong>at</strong>ures consistent with these averages will havea rel<strong>at</strong>ively higher risk of curve progressionbefore 12 years of age and a rel<strong>at</strong>ively lower riskof curve progression after 12.5 years of age. 15A scoliotic curve is more likely to progressin females, and thoracic curves or curves witha higher apex vertebral level are more likely toprogress than other types of curves. 8,14 Severecurves or moder<strong>at</strong>e curves expected to progressbeyond 100 degrees can lead to restrictivepulmonary disease and a possible reductionof life expectancy. 11 Curves of thismagnitude usually have an infantile or juvenileonset r<strong>at</strong>her than an adolescent onset.Studies 16,17 show an equal incidence of backpain and mortality in the general popul<strong>at</strong>ionand p<strong>at</strong>ients with adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis.There are few recent studies 18-20 th<strong>at</strong> evalu<strong>at</strong>ethe long-term cosmetic and psychosocialconsequences of progressive spinal curvesfrom the perspective of p<strong>at</strong>ients with scoliosis.Clinical Present<strong>at</strong>ion and Evalu<strong>at</strong>ionFamily physicians may need to examine childrenfor scoliosis who have been referred fromschool-based screening programs. Becausediastem<strong>at</strong>omyelia (congenital splitting of thespinal cord), syringomyelia (cavity in the spinalcord), a tethered cord, or a spinal tumor cancause spinal curv<strong>at</strong>ure, physicians should askthe p<strong>at</strong>ient questions concerning neurologicsymptoms. Neurofibrom<strong>at</strong>osis can be associ<strong>at</strong>edwith scoliosis, and a unil<strong>at</strong>eral cavus footcan be a manifest<strong>at</strong>ion of intraspinal p<strong>at</strong>hology.Magnetic resonance imaging should beobtained in p<strong>at</strong>ients with an onset of scoliosisbefore eight years of age, rapid curve progressionof more than 1 degree per month, anMagnetic resonance imaging should be obtained in p<strong>at</strong>ientswith an onset of scoliosis before eight years of age, rapidcurve progression, an unusual curve p<strong>at</strong>tern, neurologicdeficit, or pain.unusual curve p<strong>at</strong>tern such as left thoraciccurve, neurologic deficit, or pain. Spineabnormalities may present during routineexamin<strong>at</strong>ions of 10- to 19-year-olds. Manyexamin<strong>at</strong>ion techniques are used to evalu<strong>at</strong>ep<strong>at</strong>ients presenting with spinal curv<strong>at</strong>ures.Traditionally, the Adam’s test with level planeand ruler or a scoliometer evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of thep<strong>at</strong>ient while bending forward was used toguide clinical decision-making. 19 These measurementsare difficult to standardize andshould only be obtained when they will affectmanagement decisions for an individualp<strong>at</strong>ient or to reassure the p<strong>at</strong>ient and family. 6Height measurements of the p<strong>at</strong>ient sittingand standing should be taken in the physician’soffice every three to four months. Documentingrapid height increases helps the physiciandetermine the onset of the adolescent growthspurt and gauge the risk of rapid progressionof the spinal curve. Sitting heights can be measuredwith the p<strong>at</strong>ient sitting in a standardchair and the height of the se<strong>at</strong> subtractedfrom the total height. Changes in sitting heightcan be less than changes in standing height andgive a better estim<strong>at</strong>e of truncal growth r<strong>at</strong>e.Any examin<strong>at</strong>ion d<strong>at</strong>a must be combinedwith a thorough history to assess skeletal andsexual m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion. 21If an examin<strong>at</strong>ion of the back is conducted,the physician should begin with a survey ofthe back while the p<strong>at</strong>ient is standing. Physiciansmay be misled by scapular or shoulderasymmetry and should focus on waist creaseasymmetry or spine devi<strong>at</strong>ion during theupright examin<strong>at</strong>ion. When measuring waistcrease asymmetry, subtract perpendicularheight from the iliac crests on each side. Radiographsshould only be considered when aMAY 15, 2002 / VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 1819

90°.Most tiltedvertebraabove apex.Cobb angle.Apex90°.Most tiltedvertebrabelow apexFIGURE 2. To use the Cobb method of measuringthe degree of scoliosis, choose the mosttilted vertebrae above and below the apex ofthe curve. The angle between intersectinglines drawn perpendicular to the top of thetop vertebrae and the bottom of the bottomvertebrae is the Cobb angle.p<strong>at</strong>ient has a curve th<strong>at</strong> might require tre<strong>at</strong>mentor could progress to a stage requiringtre<strong>at</strong>ment (usually 40 to 100 degrees). 22Radiologic Evalu<strong>at</strong>ion and Classific<strong>at</strong>ionThe standard radiologic evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of adolescentidiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis consists of standingposteroanterior radiographs of the fullspine. Follow-up is necessary in those p<strong>at</strong>ientswith severe curves who are <strong>at</strong> risk for significantcurve progression or require some formof tre<strong>at</strong>ment. Any discrepancy in leg lengthshould be corrected with a block placed underthe p<strong>at</strong>ient’s shorter leg when radiographs aretaken. One study 23 has shown th<strong>at</strong> long-termmanagement of scoliosis poses no radiograph-rel<strong>at</strong>edrisks to p<strong>at</strong>ients, but posteroanteriorviews assure maximal safety by minimizingradi<strong>at</strong>ion to the breasts. The Cobbmethod is used to measure the degree of scoliosison the posteroanterior radiograph (Figure2).In addition to curve degree, physiciansshould describe curves as “right” or “left,”based on their curve convexity. Standard measurementerror is 3 to 5 degrees for the sameFIGURE 3. Posteroanterior radiograph of thespine in a p<strong>at</strong>ient with a thoracic spinal curve.Right thoracic curve, T6-11 (most tilted vertebraeabove apex of curve T6, most tilted vertebraebelow apex of curve T11). The degreeof curv<strong>at</strong>ure is 65.observer and 5 to 7 degrees for differentobservers when the same end vertebrae areused for measurements. 24,25 Thus, physiciansshould use the same end vertebrae for subsequentmeasurements and assume th<strong>at</strong> somemeasurement change may be caused by errorr<strong>at</strong>her than true curve progression.Posteroanterior radiographs should beviewed in reverse to normal chest radiographswith the p<strong>at</strong>ient’s right side on the physician’sright side. Curves are named for the loc<strong>at</strong>ionof the apex vertebrae, and may be described asthoracic (Figure 3), lumbar, thoracolumbar,cervical, or double major (two curves in differentspinal regions). A thoracolumbar curve(Figure 4) has an apex vertebrae <strong>at</strong> T12 or L1.Thoracic and lumbar curves have apex vertebraein the middle of the thoracic and lumbarregions, respectively. A double curve (Figure 5)has a major and a minor curve (based on sizeand flexibility) and a primary and secondarycurve (based on respective development). Acompens<strong>at</strong>ory curve is nonstructural and1820 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 / MAY 15, 2002

<strong>Scoliosis</strong>FIGURE 5. Posteroanterior radiograph of thespine in a p<strong>at</strong>ient with a double spinal curve.Double curve: right thoracic curve, T5-12 with adegree of curv<strong>at</strong>ure of 45; left lumbar curve,T12-L4 with a degree of curv<strong>at</strong>ure of 35.FIGURE 4. Posteroanterior radiograph of thespine in a p<strong>at</strong>ient with a thoracolumbar spinalcurve. Left thoracolumbar curve, T10-L3 (mosttilted vertebrae above apex of curve T10,most tilted vertebrae below apex of curve L3).The degree of curv<strong>at</strong>ure is 56.develops to balance out a primary curve. Anonstructural curve differs from a structuralcurve because it can correct on l<strong>at</strong>eral bending,distraction, or sitting.Management and Follow-upThe primary goal of tre<strong>at</strong>ing adolescentidiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis is preventing progressionof the curve magnitude. Curves less than 10 to15 degrees require no active tre<strong>at</strong>ment andcan be monitored, unless the p<strong>at</strong>ient’s bonesare very imm<strong>at</strong>ure and progression is likely.Moder<strong>at</strong>e curves between 25 and 45 degrees inp<strong>at</strong>ients lacking skeletal m<strong>at</strong>urity used to betre<strong>at</strong>ed with bracing, but this tre<strong>at</strong>ment hasnever been proven to prevent curve progression.Poor compliance with wearing a braceobvi<strong>at</strong>es any potential usefulness of the therapy.26 Much controversy surrounds braceindic<strong>at</strong>ions, and trends over the past 20 yearshave moved toward no bracing or bracingonly the more significant curves (20 to50 degrees). Evidence 27-29 showing the lowsymptom<strong>at</strong>ic burden of p<strong>at</strong>ients with curvesless than 60 degrees has influenced this trendaway from tre<strong>at</strong>ment with bracing.Most p<strong>at</strong>ients with adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis who require tre<strong>at</strong>ment with a bracemay use a thoracolumbar-sacral orthosis(TLSO) or a cervicothoracolumbar-sacralBracing and surgery are reserved for p<strong>at</strong>ients with severescoliosis curves.MAY 15, 2002 / VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 1821

<strong>Scoliosis</strong>orthosis (CTLSO). Recommend<strong>at</strong>ions for optimaluse of braces vary from eight to 24 hours aday depending on the style of brace chosen.In p<strong>at</strong>ients with a curve severe enough torequire surgery (gre<strong>at</strong>er than 45 degrees inadolescents and gre<strong>at</strong>er than 50 degrees inadults), rod placement and bone grafting maybe necessary to achieve partial or completecorrection. P<strong>at</strong>ient preference is essential indeciding on a surgical tre<strong>at</strong>ment, and primarycare physicians should work closely withp<strong>at</strong>ients and their families to reach optimalindividual outcomes.The author thanks Marc Asher, M.D., for editorialassistance, and Anne D. Walling, M.D., for review ofthe manuscript.The author indic<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> he does not have any conflictsof interest. Sources of funding: none reported.REFERENCES1. Yawn BP, Yawn RA, Hodge D, Kurland M, ShaughnessyWJ, Ilstrup D, et al. A popul<strong>at</strong>ion-based studyof school scoliosis screening. JAMA 1999;282:1427-32.2. Soucacos PN, Soucacos PK, Zacharis KC, Beris AE,Xenakis TA. School-screening for scoliosis: aprospective epidemiological study in northwesternand central Greece. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:1498-503.3. Kane WJ. <strong>Scoliosis</strong> prevalence: a call for a st<strong>at</strong>ementof terms. Clin Orthop 1977;126:43-6.4. Higginson G. Political consider<strong>at</strong>ions for changingmedical screening programs. JAMA 1999;282:1472-4.5. Morais T, Bernier M, Turcotte F. Age- and sex-specificprevalence of scoliosis and the value of schoolscreening programs. Am J Public Health 1985;75:1377-80.6. Grossman TW, Mazur JM, Cummings RJ. An evalu<strong>at</strong>ionof the Adams forward bend test and the scoliometerin a scoliosis school screening setting.J Pedi<strong>at</strong>r Orthop 1995;15:535-8.7. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinicalpreventive services. 2d ed. Baltimore: Williams& Wilkins, 1996:517-29.8. Lonstein JE, Carlson JM. The prediction of curveprogression in untre<strong>at</strong>ed idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis duringgrowth. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:1061-71.9. Carr AJ. Adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis in identicaltwins. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:1077.10. Miller NH. Cause and n<strong>at</strong>ural history of adolescentidiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am 1999;30:343-52.11. Weinstein SL, Ponseti IV. Curve progression in idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:447-55.12. Weinstein SL, Zavala DC, Ponseti IV. Idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis:long-term follow-up and prognosis inuntre<strong>at</strong>ed p<strong>at</strong>ients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:702-12.13. Weinstein SL. N<strong>at</strong>ural history. Spine 1999;24:2592-600.14. Peterson LE, Nachemson AL. Prediction of progressionof the curve in girls who have adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis of moder<strong>at</strong>e severity. Logisticregression analysis based on d<strong>at</strong>a from The BraceStudy of the <strong>Scoliosis</strong> Research Society. J Bone JointSurg Am 1995;77:823-7.15. Nachemson A. A long term follow-up study ofnon-tre<strong>at</strong>ed scoliosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1968;39:466-76.16. Branthwaite MA. Cardiorespir<strong>at</strong>ory consequencesof unfused idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis. Br J Dis Chest 1986;80:360-9.17. Cordover AM, Betz RR, Clements DH, Bosacco SJ.N<strong>at</strong>ural history of adolescent thoracolumbar andlumbar idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis into adulthood. J SpinalDisord 1997;10:193-6.18. Raso VJ, Lou E, Hill DL, Mahood JK, Moreau MJ,Durdle NG. Trunk distortion in adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis. J Pedi<strong>at</strong>r Orthop 1998;18:222-6.19. Bengtsson G, Fallstrom K, Jansson B, NachemsonA. A psychological and psychi<strong>at</strong>ric investig<strong>at</strong>ion ofthe adjustment of female scoliosis p<strong>at</strong>ients. ActaPsychi<strong>at</strong>r Scand 1974;50(1):50-9.20. White SF, Asher MA, Lai SM, Burton DC. P<strong>at</strong>ients’ perceptionsof overall function, pain, and appearanceafter primary posterior instrument<strong>at</strong>ion and fusion foridiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis. Spine 1999;24:1693-700.21. Amendt LE, Ause-Ellias KL, Eybers JL, Wadsworth CT,Nielsen DH, Weinstein SL. Validity and reliability testingof the Scoliometer. Phys Ther 1990;70:108-17.22. Bunnell WP. Outcome of spinal screening. Spine1993;18:1572-80.23. Drummond D, Ranallo F, Lonstein J, Brooks HL,Cameron J. Radi<strong>at</strong>ion hazards in scoliosis management.Spine 1983;8:741-8.24. Morrissy RT, Goldsmith GS, Hall EC, Kehl D, CowieGH. Measurement of the Cobb angle on radiographsof p<strong>at</strong>ients who have scoliosis. Evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of intrinsicerror. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72:320-7.25. Pruijs JE, Hageman MA, Keessen W, van der Meer R,van Wieringen JC. Vari<strong>at</strong>ion in Cobb angle measurementsin scoliosis. Skeletal Radiol 1994;23:517-20.26. DiRaimondo CV, Green NE. Brace-wear compliancein p<strong>at</strong>ients with adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis.J Pedi<strong>at</strong>r Orthop 1988;8:143-6.27. Roach JW. Adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hic scoliosis. OrthopClin North Am 1999;30:353-65.28. Karachalios T, Roidis N, Papagelopoulos PJ,Karachalios GG. The efficacy of school screeningfor scoliosis. Orthopedics 2000;23:386-91.29. Dickson RA. Spinal deformity—adolescent idiop<strong>at</strong>hicscoliosis. Nonoper<strong>at</strong>ive tre<strong>at</strong>ment. Spine1999;24:2601-6.1822 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 65, NUMBER 9 / MAY 15, 2002

<strong>Scoliosis</strong> Questions1. The resident who has most recently particip<strong>at</strong>ed in the orthopedicsrot<strong>at</strong>ion should answer this question: Wh<strong>at</strong> part of the skeleton isassessed during Risser Staging?2. The resident who has most recently been on a ship, bo<strong>at</strong>, or otherw<strong>at</strong>erborne craft should tell the group wh<strong>at</strong> percent of scoliosis is dueto a secondary condition.3. The residents with the 3 shortest last names should each name aunique cause of non-idiop<strong>at</strong>hic (secondary) scoliosis, and 1 additionalfact about th<strong>at</strong> condition.4. The youngest resident in the group should tell the group therel<strong>at</strong>ionship between gender and scoliosis.5. The resident with the last name alphabetically in the group should tellthe group the rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between Risser Stage, Tanner Stage, andscoliosis progression.6. The resident who was born furthest from your current loc<strong>at</strong>ion shouldtell the group <strong>at</strong> wh<strong>at</strong> Cobb Angles would respir<strong>at</strong>ory compromise beexpected with scoliosis.7. The resident should tell the group the angle on the scoliometer th<strong>at</strong>should prompt ordering of scoliosis films, and should do so in theirbest Southern drawl.© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012

<strong>Scoliosis</strong> Board Review1. A 14-year-old girl comes to your office because her mother is concerned about scoliosis. The mother had mildscoliosis as an adolescent, but she did not require tre<strong>at</strong>ment. The girl is previously healthy and particip<strong>at</strong>es in sports<strong>at</strong> school. She denies back pain, weakness, or abnormal sens<strong>at</strong>ions. On physical examin<strong>at</strong>ion, lumbar asymmetry isapparent when she bends forward with her arms hanging down. There are no cutaneous findings, and her neurologicexamin<strong>at</strong>ion results are normal. You order posteroanterior and l<strong>at</strong>eral radiographs of the spine to evalu<strong>at</strong>e the degreeof scoliosis.Of the following, the radiographic finding th<strong>at</strong> is MOST suggestive of a nonidiop<strong>at</strong>hic cause for this girl’s scoliosisis aA. Cobb angle of 30 degreesB. lack of thoracic kyphosisC. lumbar curve to the leftD. thoracic curve to the rightE. widening of the pedicles2. While examining a newborn, you note a persistent curve in the spine regardless of the baby’s position. You orderspine radiographs, which reveal multiple vertebral malform<strong>at</strong>ions and segment<strong>at</strong>ion defects.Of the following, the MOST appropri<strong>at</strong>e studies to guide further management areA. chromosome analysis and renal ultrasonographyB. echocardiography and chromosome analysisC. echocardiography and renal ultrasonographyD. head ultrasonography and ophthalmology consult<strong>at</strong>ionE. renal and head ultrasonography3. You work as a voluntary <strong>at</strong>tending pedi<strong>at</strong>rician in the resident continuity clinic <strong>at</strong> your local hospital. You areprecepting a resident, who tells you th<strong>at</strong> she has just evalu<strong>at</strong>ed a 16-year-old varsity volleyball player. The girl’sheight is 71 inches, weight is 125 lb, and blood pressure is 115/74 mm Hg. The resident is concerned about scoliosisand a 3/6 holosystolic murmur heard <strong>at</strong> the cardiac apex with radi<strong>at</strong>ion to the left axilla.Of the following, the MOST likely diagnosis for this p<strong>at</strong>ient isA. Ehlers—Danlos syndromeB. infective endocarditisC. Marfan syndromeD. rheum<strong>at</strong>ic heart diseaseE. Williams syndrome4. A 7-year-old boy who is new to your practice comes in for evalu<strong>at</strong>ion of developmental delay and poor schoolperformance. He began speaking in sentences <strong>at</strong> age 4. He repe<strong>at</strong>ed kindergarten and is struggling in first grade. Onphysical examin<strong>at</strong>ion, you note th<strong>at</strong> he has fair hair and light skin compared with his brown-haired, olive-skinnedyounger brother and mother. He is wearing thick glasses, and his mother says th<strong>at</strong> he was diagnosed as being nearsightedwhen he was 2 years old. He has a lanky build with long fingers, and on forward bending, there is a curve inthe thoracolumbar spine.Of the following, the condition th<strong>at</strong> is MOST consistent with this present<strong>at</strong>ion isA. alkaptonuriaB. homocystinuriaC. nonketotic hyperglycinemiaD. oculocutaneous tyrosinemiaE. phenylketonuria© <strong>NCC</strong>Peds, 2012