Continuity Patient Case Day - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter ...

Continuity Patient Case Day - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter ...

Continuity Patient Case Day - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

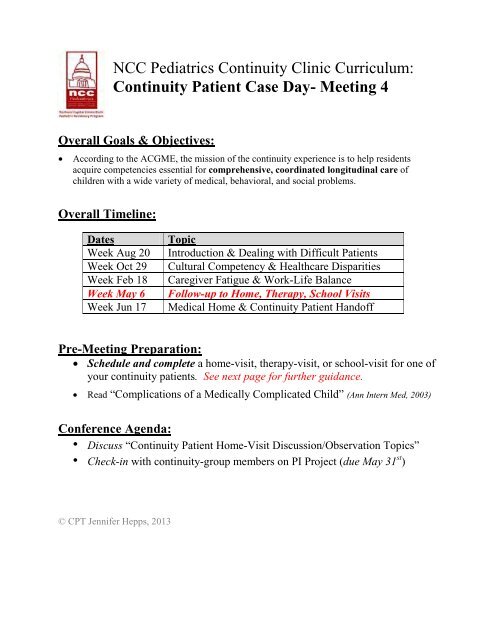

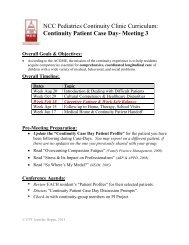

<strong>NCC</strong> <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> <strong>Continuity</strong> Clinic Curriculum:<strong>Continuity</strong> <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong> <strong>Case</strong> <strong>Day</strong>- Meeting 4Overall Goals & Objectives:• According to the ACGME, the mission of the continuity experience is to help residentsacquire competencies essential for comprehensive, coordin<strong>at</strong>ed longitudinal care ofchildren with a wide variety of medical, behavioral, and social problems.Overall Timeline:D<strong>at</strong>esWeek Aug 20Week Oct 29Week Feb 18Week May 6Week Jun 17TopicIntroduction & Dealing with Difficult <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong>sCultural Competency & Healthcare DisparitiesCaregiver F<strong>at</strong>igue & Work-Life BalanceFollow-up to Home, Therapy, School VisitsMedical Home & <strong>Continuity</strong> <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong> HandoffPre-Meeting Prepar<strong>at</strong>ion:• Schedule and complete a home-visit, therapy-visit, or school-visit for one ofyour continuity p<strong>at</strong>ients. See next page for further guidance.• Read “Complic<strong>at</strong>ions of a Medically Complic<strong>at</strong>ed Child” (Ann Intern Med, 2003)Conference Agenda:• Discuss “<strong>Continuity</strong> <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong> Home-Visit Discussion/Observ<strong>at</strong>ion Topics”• Check-in with continuity-group members on PI Project (due May 31 st )© CPT Jennifer Hepps, 2013

<strong>Continuity</strong> <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong> Home/Therapy/School VisitsGoals:• To learn how a chronic health condition affects a p<strong>at</strong>ient’s physical, emotional, andspiritual well-being, as well as th<strong>at</strong> of his or her family.• To appreci<strong>at</strong>e how living with a chronic condition affects all aspects of a family’s life—to include home, school, work, and healthcare experiences.• To understand medical diagnoses from the p<strong>at</strong>ient’s perspective, as an extension offamily-centered care practiced in the inp<strong>at</strong>ient arena.Objectives:• Contact one of your continuity p<strong>at</strong>ient’s and his/her family. Ideally, select the p<strong>at</strong>ient youhave been following throughout the <strong>Continuity</strong> <strong>Case</strong>-<strong>Day</strong> Conference Series.o You may select outp<strong>at</strong>ients with a wide range of chronic conditions—includingcommon pedi<strong>at</strong>ric conditions (e.g. asthma, ADHD, developmental delay). Youmay also select an inp<strong>at</strong>ient, whom you have followed closely on the Ward.• Schedule a visit to their home, specific therapy session (PT, OT, speech, behavioralhealth), or school, as appropri<strong>at</strong>e for the p<strong>at</strong>ient’s condition and family’s level of comfort.o If a home/therapy/school visit is impossible to schedule, you can consideraddressing the topics below in the context of a regular clinic-visit.• Complete visit prior to your continuity clinic during the week of May 6 th and be preparedto discuss your observ<strong>at</strong>ions from the visit.Topics of Discussion/Observ<strong>at</strong>ion (for p<strong>at</strong>ients or parents):• <strong>Day</strong> in the Life:o Can you describe a typical day in your life? During the work-week? Weekend?o Wh<strong>at</strong> is it like to care for your child? (Consider medic<strong>at</strong>ion administr<strong>at</strong>ion,feeding schedules, doctors’/therapists’ appointments, etc.)• Coping with a Chronic Condition:o Wh<strong>at</strong> are the best & worst aspects of having your condition? Parenting a childwith a chronic illness/disability?o Wh<strong>at</strong> has been the impact of your/your child’s condition on your life/lives?o How do you cope with the stress of your condition?o How do you feel your child is coping with his illness/disability? Wh<strong>at</strong> does heunderstand about it? Do you ever discuss it? Does he discuss it with friends?• Support Services:o To whom do you turn for help and support?o How do you and your partner divide up parenting and care-givingresponsibilities? Who else helps you take care of your child?o Have you ever felt “burnt out” as a caregiver? Wh<strong>at</strong> do you do with th<strong>at</strong> feeling?o How have your interactions been with your/your child’s doctors? Ideally, howwould you want your doctors to interact with you and your family?

On Being a <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong>Complic<strong>at</strong>ions of a Medically Complic<strong>at</strong>ed ChildThere is a phenomenon in psychology th<strong>at</strong> st<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong>active observers—people who are involved in an action—havea gre<strong>at</strong> need to predict and control a situ<strong>at</strong>ion.This couldn’t hold more true for me, the mother of a childwho is “medically complic<strong>at</strong>ed.” My 20-month-old son isthe actor, and I am the active observer. My son doesn’trealize how unusual his life is, but I know th<strong>at</strong> runningfrom a meeting to a hospital appointment one or moretimes each week is not usual for many parents. I yearn tocontrol this chaotic frenzy, but until Sam’s health problemsare under control, our lives will not be, either.“Is life always like this?” our social worker asked us.She had been assigned to us by the st<strong>at</strong>e because our son isreceiving physical and occup<strong>at</strong>ional therapies as part of theearly intervention program. Having a social worker is perceivedto be “a good thing,” but it is one more appointmentI need to arrange in an already crowded schedule.She also suggested we <strong>at</strong>tend a support group for parents ofmedically complic<strong>at</strong>ed children. While a support groupmay be helpful, I don’t really feel th<strong>at</strong> I have the time to<strong>at</strong>tend.It is assumed th<strong>at</strong> our son Sam has a connective tissuedisorder. My husband and I had always thought th<strong>at</strong> therewas something not quite right about Sam: He cried a lotduring his early months; he made no <strong>at</strong>tempt to move orroll over; and he seemed weak. His thyroid screen waspositive, but upon repe<strong>at</strong>ing it, it showed normal results.He was born with two large hem<strong>at</strong>omas on his head, butthe x-rays indic<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> there were no abnormalitiespresent. Sam developed a case of thrush th<strong>at</strong> lasted for 5months. After a normal immunologic evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, it finallycleared up without intervention. When he was 6 monthsold, I discovered he had several pubic hairs, but the endocrinetests th<strong>at</strong> followed also showed normal results. Wetried to laugh and say, “There is always something goingon with Sam.”When Sam was 9 months old, we became very concernedwith how his feet turned up and toward the ankle,and how his legs turned out in a bowlegged appearance.He was also developmentally delayed. At a well-visit, ourpedi<strong>at</strong>rician also noticed these problems. We were referredto an orthopedic surgeon, who assumed the problem wasdue to unusual positioning in utero, and referred Sam tophysical therapy. Physical therapy helped a little, but itbecame clear th<strong>at</strong> a 2-month fix was not going to help ourson in the long term.L<strong>at</strong>er, our pedi<strong>at</strong>rician caught a glimpse of Sam’s lefteye turning outward. Assuming this was strabismus, shereferred us to a pedi<strong>at</strong>ric ophthalmologist for further examin<strong>at</strong>ion.It was on 16 July 2002 th<strong>at</strong> we found out th<strong>at</strong>Sam had bil<strong>at</strong>eral ectopia lentis. Sam’s lenses in both eyeswere not loc<strong>at</strong>ed behind the pupil and iris as they shouldhave been, but were displaced outward and upward. As aresult, Sam was focusing through the curved part of thelenses, and he was highly myopic. One reason th<strong>at</strong> Samhad not wanted to move very much became clear: Hecouldn’t see beyond wh<strong>at</strong> was literally in front of his face.While this inform<strong>at</strong>ion was disturbing enough, we learnedth<strong>at</strong> disloc<strong>at</strong>ed lenses were often associ<strong>at</strong>ed with geneticsyndromes, such as the Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria,and the Weill–Marchesani syndrome. The l<strong>at</strong>ter two wereunfamiliar to me, but I knew a woman whose brother haddied of the Marfan syndrome, and th<strong>at</strong> was all I couldfocus on for several days.Such began the life of being a parent of a medicallycomplic<strong>at</strong>ed child. We learned th<strong>at</strong> we needed to becomeour son’s biggest advoc<strong>at</strong>e in a confusing health care system.We learned all we could about disloc<strong>at</strong>ed lenses andassoci<strong>at</strong>ed syndromes through the Internet, through colleagues,and through our pedi<strong>at</strong>rician, who, in this HMOworld, gave more of her time to us than is imaginable.When we saw a vitreoretinologist who wanted to removeSam’s lenses, and we instinctively felt th<strong>at</strong> this was notright, we contacted the N<strong>at</strong>ional Institutes of Health andJohns Hopkins University and learned th<strong>at</strong> if Sam did havethe Marfan syndrome, removing the lenses was not theproper intervention. We immedi<strong>at</strong>ely canceled the surgery,and we then found a leading pedi<strong>at</strong>ric ophthalmologistwho specialized in genetic conditions. Our pedi<strong>at</strong>ricianreadily agreed to refer us to this specialist; we were fit intohis busy schedule within a week, and we learned th<strong>at</strong> thefirst str<strong>at</strong>egy to follow was providing Sam with correctivelenses. <strong>Day</strong>s after this first visit, Sam received his glasses.He wasn’t happy about wearing them <strong>at</strong> first, but withinminutes, he looked around and said “Ooohhh.” He was 12months old, and he was seeing the world clearly for thefirst time.We recently moved to a large, urban area, and this hascorresponded to excellent medical care. Sam’s diagnosis isnot yet defined: He does have something, although no oneknows wh<strong>at</strong>. Still, it is difficult for most of the physicianswe see to realize the full spectrum of wh<strong>at</strong> we are dealingwith. They view Sam through the lens of their own specialty:For example, two orthopedic surgeons think Samhas the Stickler syndrome; the otolaryngologist does not.The cardiologist and ophthalmologist think he has theMarfan syndrome. The physi<strong>at</strong>rist and neurologist thinkth<strong>at</strong> he is doing well; the geneticist is concerned. Sam recentlydeveloped several inguinal hernias, thought to becommon in people with connective tissue disorders. ButSam does not fit any one p<strong>at</strong>tern clearly. Gene testing canbe performed, but <strong>at</strong> $2800 per test, the geneticists areunder pressure from the health insurance company to dothis only when there is clear clinical evidence th<strong>at</strong> a particularsyndrome may be indic<strong>at</strong>ed. After nearly 6 months ofweekly visits to specialists, we have now been given permis-© 2003 American College of Physicians 301

On Being a <strong>P<strong>at</strong>ient</strong> Complic<strong>at</strong>ions of a Medically Complic<strong>at</strong>ed Childsion for karyotyping. In May 2003, Sam was tested for theMarfan syndrome. Soon, we may know more, or no more.Apart from a diagnosis, we need Sam to receive tre<strong>at</strong>mentto improve his functional st<strong>at</strong>us. As a psychologist, Ican also see how important it is for Sam to achieve. I w<strong>at</strong>chhim make every effort to bend down and reach a fallenobject; I can follow his eyes and see him planning hisstr<strong>at</strong>egy to get across a room without letting go of a chair,a wall, or a table. Physicians X and Y both recommendedth<strong>at</strong> Sam start using corrective cable braces to turn his legsinward; however, Physician X st<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong> he should startusing them once he starts to walk, as the cable braces willslow down his progress in walking; Physician Y st<strong>at</strong>ed th<strong>at</strong>Sam should start using the cable braces now, and th<strong>at</strong> it ismore important for Sam to correct his muscle problemsbefore he begins to walk. Who is right? Interpreting medicaladvice is among the challenges we face in parenting amedically complic<strong>at</strong>ed child.An integr<strong>at</strong>ed health care system in which physiciansof various specialties meet to discuss difficult cases may beone way in which medically complic<strong>at</strong>ed children can bebest served. When Sam was diagnosed with ectopia lentis,the n<strong>at</strong>ural next step was for him to have an echocardiogram,given the associ<strong>at</strong>ion between disloc<strong>at</strong>ed lenses andthe Marfan syndrome. At this appointment, we asked thecardiologist if Sam’s difficulties with bre<strong>at</strong>hing and excessiveswe<strong>at</strong>ing could be rel<strong>at</strong>ed to a heart problem. He dismissedthis, told us th<strong>at</strong> Sam’s aortic root was large but notabnormally so and th<strong>at</strong> no cardiac problems existed. Sixmonths l<strong>at</strong>er, in our new city, Sam had a follow-up echocardiogramto recheck the aortic root size. It was then th<strong>at</strong>a p<strong>at</strong>ent ductus arteriosis was diagnosed: This congenitalheart defect may be responsible for his grunted bre<strong>at</strong>hing,excessive swe<strong>at</strong>ing, and poor weight gain. The difficulty indiagnosing this may have been due to fragmented healthcare. At the time of the second echocardiogram, Sam hadseen many more specialty physicians, and perhaps havingmore input from other physicians led to a more thoroughexam in the l<strong>at</strong>ter case, which resulted in the detection ofthe p<strong>at</strong>ent ductus arteriosis.Physicians struggle to determine Sam’s diagnosis; therapistsstruggle to get Sam to reach for th<strong>at</strong> ball, to turnthose knees in, to take an unaided step; but we, as parentsof a medically complic<strong>at</strong>ed child, struggle with muchmore. I coordin<strong>at</strong>e Sam’s medical records so th<strong>at</strong> everyphysician knows wh<strong>at</strong> every other physician is thinking.Most physicians seem gr<strong>at</strong>eful for this. I try to arrangemultiple procedures with multiple surgeons on the sameday so th<strong>at</strong> Sam will undergo anesthesia as little as possible.Many surgeons seem to want this to happen, but theirscheduling staff is not always as accommod<strong>at</strong>ing. I consultwith our daycare center to determine how Sam can best beserved next year in a classroom where everyone is walkingbut he may not be. I meet with our daughter’s teachers todiscuss her behavioral problems, possible signs of the stressshe feels. I struggle with keeping up with my work when Ineed to take off so much time to <strong>at</strong>tend medical appointments.While I know th<strong>at</strong> Sam is not any physician’s onlyp<strong>at</strong>ient, I wish sometimes th<strong>at</strong> they and the office staffwould <strong>at</strong>tempt to act like it. Recently, a pedi<strong>at</strong>ric surgeonasked me how I was coping with all of Sam’s complic<strong>at</strong>ions.It was the first time any physician had asked me howI felt. I wish it happened more often. But more important,I wish th<strong>at</strong> physicians had a better system in which theycould ask their colleagues of other specialties how they feltabout a medically complic<strong>at</strong>ed child.Rani Ghose, PhDBedford, MA 01730Note: Names have been changed to protect the identities of the p<strong>at</strong>ientand the tre<strong>at</strong>ing physicians.Requests for Single Reprints: Rani Ghose, PhD; e-mail, rani_ghose@hotmail.com.Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:301-302.302 19 August 2003 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 139 • Number 4 www.annals.org