Nutrition III - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

Nutrition III - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

Nutrition III - NCC Pediatrics Residency at Walter Reed

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

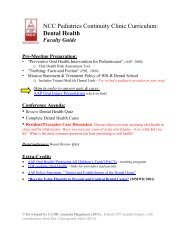

<strong>NCC</strong> <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> Continuity Clinic Curriculum:<strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>III</strong>: School-Age & AdolescentFaculty GuideGoal:To understand the nutrition recommend<strong>at</strong>ions and key issues for school-age children andadolescents, and to be able to transl<strong>at</strong>e them into practical, anticip<strong>at</strong>ory guidance for parents.* Note: Obesity will be covered separ<strong>at</strong>ely in the <strong>Nutrition</strong> IV Module.Pre-Meeting Prepar<strong>at</strong>ion:• “School-Age & Adolescent <strong>Nutrition</strong>” (Excerpts from HealthyChildren.org)• “Vegetarian Diets in Children and Adolescents” (PIR, 2009)• “Diagnosis of E<strong>at</strong>ing Disorders in Primary Care” (AAFP, 2003)• “Feeding & E<strong>at</strong>ing Disorders” (DSM-V Upd<strong>at</strong>e, 2013)• Be prepared to provide a case-example or FAQ rel<strong>at</strong>ed to School-Age & Adolescent<strong>Nutrition</strong> from your clinic experience. Discuss how you approached the case/ question.Conference Agenda:• Review <strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>III</strong> Quiz• Complete <strong>Nutrition</strong> <strong>III</strong> Cases• Round table discussion of resident School-Age & Adolescent casesPost-Conference: Board Review Q&AExtra Credit:Please review the following enclosures, rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the practical guidelines, above:• AAP Clinical Report on E<strong>at</strong>ing Disorders (<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong>, 2010)• E<strong>at</strong>ing Disorders (PIR, 2011)• Vegetarian E<strong>at</strong>ing for Children and Adolescents (JPEDHC, 2006)• Vitamin Deficiency & Overdose Chart (helpful for Board Review questions)

• Sugar: Many children consume sugar in gre<strong>at</strong> quantities, usually <strong>at</strong> the expense of healthier foods(e.g. sodas and juice, instead of milk or w<strong>at</strong>er). Keep consumption <strong>at</strong> moder<strong>at</strong>e levels.• Salt: The habit of using extra salt is acquired. Thus, as much as possible, serve your child foodlow in salt, to decrease the risk of high blood pressure. Use herbs, spices, or lemon juice to flavorfoods and avoid processed foods such as cheese, instant puddings, canned vegetables and soups,hot dogs, salad dressing, pickles, and pot<strong>at</strong>o chips.VitaminsSupplements are rarely needed in middle childhood, since a balanced diet contains sufficient quantitiesfor the essential vitamins and minerals. However, children with poor appetite, err<strong>at</strong>ic e<strong>at</strong>ing habits, orhighly selective diets (e.g. vegetarian or vegan) may need vitamin supplements.Over-the-counter supplements (e.g. Flintstones chewables or gummies) are generally safe; however, iftaken in excessive amounts or combined, some—particularly f<strong>at</strong>-soluble vitamins (ADEK)—can be toxic.Of note, “mega-vitamin therapy” or “orthomolecular medicine”— in which vitamins are given inextremely large doses for conditions ranging from the common cold to hyperactivity— has no provenscientific validity and may pose risks.Following are some of the vitamins and minerals necessary for normally growing children, and some ofthe foods th<strong>at</strong> contain them. (Review this “Vitamin Deficiency & Overdose Chart” chart for a morecomplete list of vitamins and the conditions associ<strong>at</strong>ed with deficiency or excessive intake).• Vitamin A promotes normal growth, healthy skin, and tissue repair, and aids in night and colorvision. Rich sources include yellow vegetables, dairy products, and liver.• B vitamins promote red blood cell form<strong>at</strong>ion and assist in a variety of metabolic activities. Foundin me<strong>at</strong>, poultry, fish, soybeans, milk, eggs, whole grains, and enriched breads and cereals.• Vitamin C hastens the healing of wounds and increases resistance to infection. Found in citrusfruits, strawberries, tom<strong>at</strong>oes, pot<strong>at</strong>oes, Brussels sprouts, spinach, and broccoli.• Vitamin D promotes tooth and bone form<strong>at</strong>ion and regul<strong>at</strong>es calcium absorption. Sources includefortified dairy products, fish oils, fortified margarine, and egg yolks. Sunlight also contributes todietary sources of vitamin D, stimul<strong>at</strong>ing the conversion in the skin.Adolescent <strong>Nutrition</strong>M<strong>at</strong>erial adapted from: http://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/Calories & ServingsThe body demands more calories during early adolescence than <strong>at</strong> any other time of life. On average,boys require about 2800 calories per day; and girls, 2200 calories per day. Typically, the ravenoushunger of adolescence starts to wane once a child has stopped growing, though not always. Kids whoparticip<strong>at</strong>e in physical activity will still need increased amounts of energy into l<strong>at</strong>e adolescence.Serving sizes for teenagers should still be about the same as they are for adults. Please review thechart on the following page to see the number of servings and sizes recommended for the average teen.The USDA “Food Pl<strong>at</strong>e” can still be used as a visual guide.

Food GroupNumber of Servings Per DayFemalesCalories Aged 11-24Total Calories: 2,200MalesAged 11-14Total Calories: 2,500Aged 15-18Total Calories: 3,000Aged 19-24Total Calories: 2,900Bread, Cereal, Rice and Pasta Group6-11 servingsMilk, Yogurt and Cheese Group4-5 servingsVegetable Group3-5 servingsFruit Group2-4 servingsMe<strong>at</strong>, Poultry, Fish, Dry Beans, Eggs and Nuts2-3 servings9 servings 11servings4 or 5 servings Aged 11-18: 4 or 5 servingsAged 19-24: 2-3 servings4 servings 5 servings3 servings 4 servings6 ounces total 7 ounces totalTotal F<strong>at</strong> 73 grams Aged 11-14: 83 gramsAged 15-18: 1,000 gramsTotal Added Sugar 12 teaspoons 18 teaspoonsVariety & NutrientsThere are a number of obstacles to balanced adolescent nutrition:• Skipping meals: According to a recent poll, about ½ boys and girls aged 9-15 years said th<strong>at</strong>they didn’t e<strong>at</strong> breakfast on school mornings. Breakfast-to-go options include a bagel andpeanut-butter, a hard-boiled egg, nuts & raisins, a yogurt, or an apple.• Snacking: 1/3 of the caloric intake of adolescents comes from snacks—particularly unhealthyones. It’s therefore important to keep the refriger<strong>at</strong>or and pantry stocked with healthy optionslike low-f<strong>at</strong> cheeses, applesauce, air-popped popcorn, and baked pot<strong>at</strong>o chips.• E<strong>at</strong>ing away from home: At school, adolescents will often settle for a stop <strong>at</strong> the vendingmachine for lunch. After school, they may decide th<strong>at</strong> fitting in with their peers <strong>at</strong> a fast-foodrestaurant or pizza shop is more important than making healthy food selections. Brainstormhealthy altern<strong>at</strong>ives and/or other activities to do with their peers.• The lure of fad diets: As teenage girls “hopscotch” from one fad diet to another, good nutritionmay fall by the wayside. Reinforce th<strong>at</strong> these diets are too restrictive and unhealthy and bad forweight-loss in the long-run.The guidance in the above section for “Foods to Reduce” still applies to adolescents. Also remember,each gram of protein and carbohydr<strong>at</strong>es supplies 4 calories, whereas f<strong>at</strong> contributes 9 calories/gram.VitaminsAdolescents—particularly girls, who e<strong>at</strong> roughly 25% fewer calories per day than boys— tend to fallshort of their daily quotas of vitamins and minerals. Calcium, iron and zinc are most vulnerable.

Calcium:Adolescence provides a window of opportunity for avoiding osteoporosis l<strong>at</strong>er in life. During the teenageyears, the growing bones absorb more calcium from the blood than <strong>at</strong> any other time of life. By earlyadulthood, our bones stop accepting deposits, and not long after, the gradual loss of calcium begins.In a clinical study sponsored by the N<strong>at</strong>ional Institute of Child Health and Human Development, onegroup of teenage girls received daily supplements containing an extra 500 mg calcium; the other group’scalcium came strictly from food. The girls who were given supplements saw their bone density improveby 14%. Each 5% increase in bone mass reduces the risk of suffering a bone fracture by 40%.The American Academy of <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> recommends the following daily intake of calcium:Age Calcium Need (mg per day) Servings of Milk to Meet Need4–8 years 800 3 servings9–18 years 1,300 4 servings19–50 years 1,000 3–4 servingsMilk and milk products provide ¾ of the calcium in the American diet. Other foods contain calcium, likebroccoli and collard greens. However, these vegetables also contain substances th<strong>at</strong> impair the body’sability to absorb calcium, so th<strong>at</strong> a teen would need to e<strong>at</strong> approxim<strong>at</strong>ely 9 cups of broccoli a day to meetthe recommended intake. Also consider calcium-fortified juice (no more than 8-12 oz/day!) and cereals.Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, 2/3 of adolescent girls in the US fail to meet the daily requirement for calcium. The NIHsupports the use of supplements for young people who don’t get sufficient calcium through their diet. Foroptimal absorption, no more than 500mg should be taken <strong>at</strong> one time.Also remember th<strong>at</strong> other factors can decrease calcium and impair bone health: excessive soda intake;vegan diets; caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco; certain medic<strong>at</strong>ions (e.g. diuretics) and GI diseases (e.g. IBD).Iron:According to a n<strong>at</strong>ional survey conducted by the USDA, three in four teenage girls’ diets are deficient inthis essential mineral, as compared to just one in five of their male counterparts. Adolescent girls are alsoprone to iron-deficiency due to menstrual losses.Foods rich in iron include me<strong>at</strong>s (beef, pork, lamb, liver); poultry (especially dark me<strong>at</strong>); fish; dark-greenleafy vegetables (kale, collards, broccoli); legumes (lima beans, peas, dry beans); dried fruit (prunes,apricots, raisins); pot<strong>at</strong>oes with skin; seeds (sunflower, pumpkin, squash); and whole-whe<strong>at</strong> breads.Other points to keep in mind are, as follows: (1) the iron in me<strong>at</strong>, poultry, and fish is more readilyabsorbed than the iron in vegetables, beans, and grains; (2) vitamin C & citric acid in fruits promotesabsorption of iron; (3) the tannins in tea can interfere with metabolism of non-heme (i.e. non-me<strong>at</strong>) iron.Please review “Screening for Iron Deficiency” (see Health Maintenance II) for more inform<strong>at</strong>ion aboutthe p<strong>at</strong>hophysiology, evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, and tre<strong>at</strong>ment of iron-deficiency anemia.

Article nutritionVegetarian Diets in Childrenand AdolescentsMeredith Renda, MD,*Philip Fischer, MD*Author DisclosureDrs Renda and Fischerhave disclosed nofinancial rel<strong>at</strong>ionshipsrelevant to thisarticle. Thiscommentary does notcontain a discussionof an unapproved/investig<strong>at</strong>ive use of acommercial product/device.IntroductionVegetarianism is becoming more common among adults, with 1 in 40 adults currentlychoosing a vegetarian diet. Consequently, more children are raised as vegetarians. Vegetarianismis adopted for various reasons, including moral, religious, and health. Numerousstudies have shown significant health benefits for individuals following this type of diet.Pedi<strong>at</strong>ricians should be well informed about vegetarianism and its role in our pedi<strong>at</strong>ricpopul<strong>at</strong>ion.Case 1A first-time mother and her 2-month-old boy present to the clinic for a health supervision visit.The mother is breastfeeding, and her baby is growing appropri<strong>at</strong>ely. At the end of the visit, themother mentions th<strong>at</strong> she is a vegetarian and th<strong>at</strong> she would like to raise her son in the sameway. She would like to know wh<strong>at</strong> she should be doing as a breastfeeding mother and how she canmake sure th<strong>at</strong> her son has the appropri<strong>at</strong>e nutrition in the future.The physician should begin by taking a dietary history from the mother to determinewh<strong>at</strong> type of vegetarianism she practices. He or she should explain to the mother th<strong>at</strong> herinfant’s nutrition is based on her own dietary intake for as long as she continues tobreastfeed. The pedi<strong>at</strong>rician should counsel the mother on the importance of diet variety.If the mother is vegan, the pedi<strong>at</strong>rician must take time to ensure th<strong>at</strong> she is getting enoughvitamin B 12 and calcium in her diet. When she is ready to wean her infant, she shouldcontinue to focus on dietary variety. The mother should be cautioned th<strong>at</strong> adult vegetariandiets th<strong>at</strong> are high in bulk and low in calories are not always appropri<strong>at</strong>e for the growingand developing child. Finally, the pedi<strong>at</strong>rician should ensure th<strong>at</strong> the mother has theappropri<strong>at</strong>e resources to guide her in finding the best foods for her child’s nutritionalneeds.Initi<strong>at</strong>ing a DialogueWhen confronted with this scenario, it is most important to take a dietary history.Although this mother defines herself as a vegetarian, she did not specify wh<strong>at</strong> type ofvegetarianism she practices (Table 1). In the simplest sense, a vegetarian elimin<strong>at</strong>esanimal-flesh foods and products from the diet (including fish). However, the definition canbe deline<strong>at</strong>ed further. A lacto-ovovegetarian consumes milk and egg products. A lactovegetarianconsumes milk in addition to plant products. A vegan elimin<strong>at</strong>es all animal and fishproducts. Recommend<strong>at</strong>ions for this mother depend on wh<strong>at</strong> form of vegetarianism shefollows.Comparing Human Milk CompositionFor the first 6 to 12 months after birth, most babies are lactovegetarians. Their primarysource of nutrition is milk, either from human milk or formula. Studies have shown th<strong>at</strong> forthe first 6 months, the human milk of a lacto-ovovegetarian does not differ significantlyfrom th<strong>at</strong> of an omnivore. (1) Specifically, the composition of human milk betweenlacto-ovovegetarians and omnivores is similar in minerals, trace elements, lactose, and totalf<strong>at</strong>. Another study revealed th<strong>at</strong> human milk from vegetarians has fewer environmental andindirect additives than th<strong>at</strong> of nonvegetarians. (2)* Department of <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong>, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009 e1Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

nutritionvegetarian dietsTable 1. Types of VegetarianismSemivegetarianIncludes poultry and fishLacto-ovovegetarianIncludes milk and egg productsLactovegetarianIncludes milk productsVeganElimin<strong>at</strong>es all animal and fish productsImportant <strong>Nutrition</strong>al Consider<strong>at</strong>ionsLacto-ovovegetarians and lactovegetarians (who consumemilk or eggs or both in their diet) tend to be lessdeficient in certain elements than vegans, who elimin<strong>at</strong>eall fish and animal products. Surprisingly, the humanmilk of poorly nourished women often has rel<strong>at</strong>ivelyadequ<strong>at</strong>e volume and composition. One hypothesis isth<strong>at</strong> human milk composition is maintained to the detrimentof the mother’s overall nutritional st<strong>at</strong>us. Regardlessof the volume and composition, human milk ofpoorly nourished women may have fewer calories, w<strong>at</strong>ersolublevitamins, calcium, and protein. (3) All vegetariansshould pay special <strong>at</strong>tention to the amount of vitaminB 12 , fol<strong>at</strong>e, and omega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acids th<strong>at</strong> they consume.Vitamin B 12 and fol<strong>at</strong>e are important factors in proteinand DNA synthesis as well as in growth and developmentof the brain and nervous system. Omega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acidsplay a significant role in brain and retinal development.During times of growth and reproduction, requirementsfor these elements increase.Vitamin B 12Reliable sources for vitamin B 12 for the vegetarian includecereal, nondairy beverages, me<strong>at</strong> analogs, and supplements.It is important to read the labels to ascertainth<strong>at</strong> the item has been fortified with vitamin B 12 .Ifavegan mother does not consume enough B 12 -fortifiedfoods or supplements, her infant receives 0.4 mcg/day ofvitamin B 12 during the first 6 postn<strong>at</strong>al months and0.5 mcg/day after 6 months of age. (4) Another reasonth<strong>at</strong> a breastfed infant might need to receive supplement<strong>at</strong>ionwith vitamin B 12 is if the mother had an ilealresection. Removing this section of the bowel preventsthe body from absorbing vitamin B 12 .Fol<strong>at</strong>eFol<strong>at</strong>e is found in enriched breads, pastas, cereals, greenleafy vegetables, and orange juice. Interestingly, mostvegetarians consume more than the recommendedamount of fol<strong>at</strong>e. Although the addition of fol<strong>at</strong>e tofortified foods has helped to reduce the risk of neuraltube defects in infants, fol<strong>at</strong>e can mask some of thehem<strong>at</strong>ologic changes th<strong>at</strong> signal a vitamin B 12 deficiency.A vitamin B 12 deficiency th<strong>at</strong> has been masked by fol<strong>at</strong>emay not be apparent until deleterious neurologic consequencesalready have occurred. (5)Omega-3 F<strong>at</strong>ty AcidsOmega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acids are important in all lact<strong>at</strong>ing womenbecause they assist in brain and retinal development ofnursing infants. However, they also serve a special rolefor vegetarians because they act as building blocks for thelonger chain f<strong>at</strong>ty acids docosahexaenoic (DHA) andeicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), which are found in fish.DHA and EPA are critical for brain and organ developmentin the fetus and newborn. A daily intake of 3 to 5 gof omega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acids is adequ<strong>at</strong>e, based on a 2,000-kcal/day diet. However, lact<strong>at</strong>ing women (especiallyvegetarians) should consider supplement<strong>at</strong>ion with reliablesources of f<strong>at</strong>ty acids. Omega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acids can befound in walnuts, flax seed, hemp, dark greens, and tofu.Quality fish oil supplements and DHA-rich eggs also areavailable for consumption. (6)Weaning Future VegetariansWhen weaning infants from human milk, it is importantto ensure th<strong>at</strong> they receive adequ<strong>at</strong>e nutrition. Dietaryproblems th<strong>at</strong> stem from certain inadequacies are seenmore often in children than in adults. Children havegre<strong>at</strong>er energy requirements rel<strong>at</strong>ive to their bodyweight, and they are not always in control of wh<strong>at</strong> theye<strong>at</strong>. Many of the significant deficiencies seen in childrenoccur because of inappropri<strong>at</strong>e understanding and dietarychoices by adults.Vegetarian diets th<strong>at</strong> are appropri<strong>at</strong>e for adults are notalways right for children. Adults tend to want to consumefoods th<strong>at</strong> are lower in caloric and f<strong>at</strong> content, yet high inbulk. The bulk ensures th<strong>at</strong> the stomach feels full despitethe adult consuming a lesser amount of calories and f<strong>at</strong>.A child who is 1 to 3 years of age has a stomach capacityof only 200 to 300 mL <strong>at</strong> each meal. Thus, problemsensue when high-bulk foods are e<strong>at</strong>en by children. Childrenmay feel s<strong>at</strong>i<strong>at</strong>ed quickly, even though they have note<strong>at</strong>en an adequ<strong>at</strong>e amount of their nutritional requirements.(7)When well-informed parents raise vegetarian children,e2 <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

nutritionvegetarian dietsstudies show th<strong>at</strong> the children’s means for height for age,weight for age, and weight for height are close to the50th percentile of the N<strong>at</strong>ional Center for Health St<strong>at</strong>isticsreference values. (8) Another study of vegetarianBritish children, ages 1 to 18 years, found heights,weights, and head and chest circumferences to be withinnormal range compared with those of nonvegetarianBritish children. (9)Dietary Variety is the Secret to SuccessWhen a vegetarian follows a well-rounded diet, thehealth benefits are numerous. In an analysis of five prospectivestudies examining mortality in vegetarians andnonvegetarians, vegetarians had a 24% decrease in ischemicheart disease. (10) Vegetarian children tend to beleaner and have lower rel<strong>at</strong>ive body weights and skinfoldthicknesses while retaining normal growth and m<strong>at</strong>ur<strong>at</strong>ion.(11) As food sources become increasingly fortified,it is easier and more convenient to provide vegetarianchildren with appropri<strong>at</strong>e food elements. Parents shouldensure th<strong>at</strong> their children are receiving adequ<strong>at</strong>eamounts of vitamin B 12 , fol<strong>at</strong>e, iron, and zinc (Table 2).Food also should be high in energy density withoutsignificant bulk.Table 2. Nutrients and FoodSourcesProteinTofu, tempeh, legumes, grains, eggs, dairyOmega-3 F<strong>at</strong>ty AcidsFlax seed, dark greens, tofu, fish oil, nutsIronLegumes, nuts, dried fruit, spinach, fortified grainsCalciumKale, broccoli, fortified orange juice, fortified soy, figs,dairyZincWhole grains, legumes, nuts, whe<strong>at</strong> germ, whole grainpastaFol<strong>at</strong>eLegumes, dark green leafy vegetables, fortified cereals/breadsVitamin B 12Fortified eggs, fortified dairy, cereals, breads, somefortified soyToddlers and preschool-age children tend to developstrong e<strong>at</strong>ing preferences, and it may be difficult topresent a variety of foods to them each day. P<strong>at</strong>ience,along with repe<strong>at</strong>ed exposure to unfamiliar foods, mayhelp. When opting for prepackaged foods made with tofuor tempeh (fermented soy), it is important to read thenutritional inform<strong>at</strong>ion. Many of these processed foodstend to be high in f<strong>at</strong>, sodium, and calories, similar tononvegetarian packaged foods.Parents should make “whole plant food” the primarystaple in their child’s diet. This element includes wholegrain breads, pastas, cereals, tofu, soy, legumes, vegetables,and fruits. Legumes are a class of vegetables th<strong>at</strong>includes a variety of beans, peas, and lentils. Nutrients invegetables are preserved best when they are cooked withthe least amount of he<strong>at</strong>, w<strong>at</strong>er, and time. Therefore,ideal cooking includes steaming vegetables in a smallamount of w<strong>at</strong>er, stir-frying, and boiling in a bag. Asmentioned, vitamin B 12 and fol<strong>at</strong>e are found in a varietyof fortified cereals and breads. Iron can be found in driedfruits, legumes, nuts, and fortified foods. Zinc also isfound in legumes, nuts, and whole grains.Although protein can be a concern, plant foods providemore than 10% of their calories in the form ofprotein. Plant foods combined with me<strong>at</strong> substitutessuch as soy and tempeh tend to provide adequ<strong>at</strong>e proteinfor the vegetarian child. The protein intake of veganchildren has been shown to be similar to th<strong>at</strong> of nonvegetarianchildren, and the intake also is higher than therecommended standard. (12)Case 2A new p<strong>at</strong>ient and his parents present to the clinic for ahealth supervision visit. The boy is 7 years old and has hadappropri<strong>at</strong>e growth and development. The parents arelacto-ovovegetarians, and they have raised their son in thesame way. As their son becomes older and more independent,they have concerns about his e<strong>at</strong>ing p<strong>at</strong>terns andnutrition. They want to ensure th<strong>at</strong> he makes appropri<strong>at</strong>efood choices <strong>at</strong> school and <strong>at</strong> friends’ houses. They ask you foradvice in ensuring th<strong>at</strong> he continues to have appropri<strong>at</strong>enutrition now and in the future.It is important to identify the parents’ reasons forbeing vegetarian as well as their reasons for raising theirson as a vegetarian. It also is essential th<strong>at</strong> the physicianask both the parents and child how each feels about beingvegetarian. Although the boy is only 7 years old, he mostlikely is exposed to many different types of food while <strong>at</strong>school and friends’ homes. How have these experiencesinfluenced his feelings about his daily diet? The physicianshould follow this discussion with a dietary history. If<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009 e3Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

Planning AheadBecause of the many motiv<strong>at</strong>ions and r<strong>at</strong>ionales forchoosing vegetarianism, parents’ discussions will differamong their children. Regardless of the differences, parentscan be more prepared to work through specificissues if they have some universal tools <strong>at</strong> their disposal.Following a vegetarian diet can be challenging to eventhe most experienced vegetarian. Despite advancingpublic awareness, vegetarian options are not always available;planning ahead is often necessary. This proves to beof gre<strong>at</strong>er consequence when a child is involved. Thevegetarian school-age child always should leave thehouse with an appropri<strong>at</strong>e meal or <strong>at</strong> least with a snackth<strong>at</strong> he or she can e<strong>at</strong> if there are no vegetarian options. Ifpeer inclusion is an issue, parents should think aboutpacking vegetarian foods th<strong>at</strong> mimic popular me<strong>at</strong> products(ie, veggie burger, soy nuggets). Children feel moreincluded in peer groups if their meal appears similar.Packing food for other situ<strong>at</strong>ions may be more complex.If a vegetarian child is asked to dinner <strong>at</strong> a friend’shouse, the child and his parents may seem impolite if thechild brings his or her own food. In this case, communic<strong>at</strong>ionis the key. Once nonvegetarian parents understandthe situ<strong>at</strong>ion, they may be very accommod<strong>at</strong>ing interms of offering food th<strong>at</strong> is appropri<strong>at</strong>e for the vegetarianchild. On the other hand, some parents may welcomehelp from a vegetarian parent in terms of suggesting orpacking appropri<strong>at</strong>e foods. Parents of nonvegetarianchildren may be very agreeable to preparing foods fortheir vegetarian guest, but they may not know wh<strong>at</strong> tocook. Vegetarian parents can offer some basic educ<strong>at</strong>ionif they think other parents would be open to suggestions.Although planning ahead can address many scenarios,parents and children should role-play to practice scriptsth<strong>at</strong> deal with unexpected situ<strong>at</strong>ions. Role-playing isparticularly useful because it may help parents understandwh<strong>at</strong> type of circumstance causes their children themost worry or apprehension. Acting out a few scenarioscan do wonders in terms of quelling a school-age vegetarian’sconcerns regarding diet.Finally, it is important for parents to discuss vegetarianismand nonvegetarianism in a way th<strong>at</strong> does not placeundue positive or neg<strong>at</strong>ive values on either group.A common defense mechanism for parents of a vegetarnutritionvegetarian dietsadditional educ<strong>at</strong>ion is needed to teach the family aboutappropri<strong>at</strong>e nutrition, more time should be arranged todelve into this issue. The physician should ensure th<strong>at</strong>this family has the appropri<strong>at</strong>e resources available tothem. Finally, the physician needs to begin to touch onthe topics of independence and autonomy. Dependingon how this boy feels about being a vegetarian, thephysician may want to counsel the parents on ways th<strong>at</strong>they can be accepting of their son regardless of whetherhe chooses to be vegetarian in the future.Raising a School-age VegetarianFrom a nutritional standpoint, raising a school-age vegetarianis not very different from raising a younger vegetarian.These children require the same nutritional consider<strong>at</strong>ionsas their younger counterparts, with particular<strong>at</strong>tention paid to elements such as vitamin B 12 , fol<strong>at</strong>e,omega-3 f<strong>at</strong>ty acids, and protein. Dietary variety is thebest way to ensure normal growth and development forvegetarian children.Aside from the nutritional issues, however, manyother aspects of vegetarianism during elementary schoolages should be considered. Whereas the toddler orpreschool-age child is still e<strong>at</strong>ing most of his or her meals<strong>at</strong> home, the school-age child often e<strong>at</strong>s a large portion ofhis or her daily diet away from the home (school, extracurricularactivities, friends’ homes). Not only is it moredifficult for parents to be in control of wh<strong>at</strong> their childrenare e<strong>at</strong>ing, but it also may be difficult for the child tomake appropri<strong>at</strong>e choices based on the foods th<strong>at</strong> areavailable.The school-age child places a gre<strong>at</strong> deal of interest andimportance on fitting in among his or her social group.Acceptance in one’s social group often depends on theability to rel<strong>at</strong>e to other children and share in commonexperiences. If a vegetarian child is unable to share incommon experiences, such as meals, this st<strong>at</strong>e may bedistressing for the child and peers alike.Finally, school-age children are just beginning to realizeth<strong>at</strong> children and families are not all similar to theirown. Depending on school and social experiences, somevegetarian children may be exposed to many differentfoods th<strong>at</strong> they have never encountered. Curiosity maycause vegetarian children to desire new foods, includingme<strong>at</strong> products. If vegetarian children feel th<strong>at</strong> they areunjustly restricted, or if the restriction causes them distress,they may begin to resent their vegetarian diets.To identify and resolve issues rel<strong>at</strong>ed to school-agevegetarians, parents should determine how strongly theyfeel about reinforcing a vegetarian diet inside and outsideof the home. As children enter school and become moreindependent, some parents allow their children the freedomof dietary experiment<strong>at</strong>ion. Others may feel th<strong>at</strong> avegetarian diet takes precedence, regardless of the circumstances.Once a viewpoint has been determined,parents should include their children in a discussion th<strong>at</strong>tackles the issues pertinent to school-age vegetarians.e4 <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

nutritionvegetarian dietsian child who is questioning his or her diet may be tospeak of nonvegetarians neg<strong>at</strong>ively. This type of copingskill is detrimental because it accentu<strong>at</strong>es the differencesth<strong>at</strong> already are of concern to the vegetarian child. It alsomay have a paradoxic effect in th<strong>at</strong> the vegetarian childmay have heightened neg<strong>at</strong>ive feelings about his or herdiet if the child feels th<strong>at</strong> his or her parents have spokenneg<strong>at</strong>ively about a cherished friend or peer. Parentsshould <strong>at</strong>tempt to discuss issues of diet with objectivity.In doing so, they will make their argument more effectivelywithout alien<strong>at</strong>ing others.Case 3A 16-year-old girl returns to the pedi<strong>at</strong>ric clinic for her firsthealth supervision visit in 5 years. When questions ariseconcerning her diet, she appears very defensive. She st<strong>at</strong>esth<strong>at</strong> she became a vegetarian on February 16, approxim<strong>at</strong>ely2 months ago. She reluctantly shares th<strong>at</strong> her dietconsists largely of pasta, bagels, and “side dishes” from thefamily meal. She cites “animal cruelty” as her motiv<strong>at</strong>ionto become a vegetarian.The physician should begin by taking a dietary historyas well as <strong>at</strong>tempting to determine wh<strong>at</strong> prompted thisteen to change her diet, remembering th<strong>at</strong> adolescence isa unique period of development th<strong>at</strong> may have played arole in this teen’s motiv<strong>at</strong>ions. To provide the mostcomprehensive educ<strong>at</strong>ion regarding vegetarianism, theteen’s family should be included in the discussion wheneverpossible. The physician should ensure th<strong>at</strong> the teenand her family have access to accur<strong>at</strong>e resources th<strong>at</strong> canprovide them with important inform<strong>at</strong>ion. Finally, thephysician should take the time to ensure th<strong>at</strong> this teen’sdecision to be vegetarian was not based on an underlyingemotional problem, including an e<strong>at</strong>ing disorder.Adolescent Vegetarians: A Unique ChallengeDuring adolescence, youth assert their independence,develop their self-identity, and build rel<strong>at</strong>ionships withboth sexes. Adolescent vegetarians should not bethought of as younger versions of adult vegetarians. Thecommon adult explan<strong>at</strong>ions for a vegetarian diet includehealth, religious, familial, and cultural reasons. However,these motives do not always influence adolescents in thesame way. Often, the decisions th<strong>at</strong> adolescents make arerel<strong>at</strong>ed directly to their developmental needs and developmentalstage. (13)The most challenging of adolescent vegetarians is onewho has been raised as an omnivore and who decides tochange dietary habits independent of his or her family’se<strong>at</strong>ing style. Of a sample adolescent popul<strong>at</strong>ion in Minnesotaof just fewer than 20,000 individuals, 0.6% ofadolescents identified themselves as vegetarians. (14)The starting point for an appropri<strong>at</strong>e dialogue with <strong>at</strong>eenage p<strong>at</strong>ient is similar to th<strong>at</strong> of a breastfeeding mother:taking a dietary history. It is most important toascertain wh<strong>at</strong> it means to this young woman to be avegetarian. Similarly, how does she define and apply thisform of diet in her own life?The Typical Adolescent VegetarianMost adolescent vegetarians tend to be female. In onestudy th<strong>at</strong> investig<strong>at</strong>ed adolescent vegetarians in Minnesota,81% of self-identified vegetarians were female, andonly 19% were male. (14) Most often, adolescent vegetariansshare neg<strong>at</strong>ive feelings toward e<strong>at</strong>ing me<strong>at</strong>, feelstrongly about animal cruelty, and place more importanceon their appearance and environment. (13) Anothercommon characteristic of adolescent vegetarians isth<strong>at</strong> they engage in many positive behaviors. Adolescentvegetarians tend to consume more fruits and vegetableswhile consuming fewer sweet and salty snack foods.These youth also tend to weigh less than their nonvegetarianpeers.An important aspect of adolescence is th<strong>at</strong> many decisionsare made impulsively and without much consider<strong>at</strong>ionfor the future. Consequently, positive aspects ofvegetarianism also can lend themselves to neg<strong>at</strong>ive orharmful behaviors. All vegetarians are <strong>at</strong> risk for nutritionalinadequacies if they do not consume appropri<strong>at</strong>eamounts of foods rich in protein, iron, calcium, and zinc.Adolescents are <strong>at</strong> even gre<strong>at</strong>er risk if their decisions tobecome vegetarian were sudden and without proper<strong>at</strong>tention to necessary details and inform<strong>at</strong>ion.The adolescent p<strong>at</strong>ient in this case revealed a distinctd<strong>at</strong>e in history when she changed her e<strong>at</strong>ing habits. Hersudden dietary changes, as well as her current foodchoices, imply th<strong>at</strong> her decision was not well researched.If she were to continue to e<strong>at</strong> the foods th<strong>at</strong> she describes(pastas, bagels, and “side dishes”), she would be <strong>at</strong> riskfor specific nutritional deficiencies. However, adolescentsfrequently have difficulty imagining the future, andit can be challenging to impress on them future consequences.Regardless, efforts should be made to preparethem for the future because adolescents will be in chargeof all their dietary choices once they leave the home forcollege or employment.The Vegetarian Food Guide Pyramid, a NewModelTo capitalize on positive benefits and minimize neg<strong>at</strong>iveconsequences, it is important th<strong>at</strong> adolescent vegetariansreceive appropri<strong>at</strong>e counseling and guidance regarding<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009 e5Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

nutritionvegetarian dietsFigure 1. The Food Guide Pyramid.their dietary choices. One of the challenges in providingappropri<strong>at</strong>e inform<strong>at</strong>ion is the limited number of easilyaccessible models th<strong>at</strong> demonstr<strong>at</strong>e wh<strong>at</strong> foods are importantand how they should be applied to the diet. Mostadolescents are familiar with the Food Guide Pyramid, amodel th<strong>at</strong> shows how nutritional guidelines and requirementsfit into one’s daily food choices (Fig. 1). Thedifficulty in using the Food Pyramid as a guide whentalking to vegetarian adolescents is th<strong>at</strong> it targets a popul<strong>at</strong>ionof omnivores. Thus, the nutritional standards arebased on a nonvegetarian diet. (15)There are adapt<strong>at</strong>ions of the food guide to account forvegetarianism. One example is the United St<strong>at</strong>es Departmentof Agriculture’s Food Guide Pyramid. In thisguide, flesh foods are elimin<strong>at</strong>ed from the protein foodgroup. Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, this guide does not take intoaccount th<strong>at</strong> some vegetarians exclude all animal and fishproducts. Therefore, dairy products and eggs also shouldbe elimin<strong>at</strong>ed. Additionally, the proportions of the pyramidno longer are appropri<strong>at</strong>e because certain staplefoods have been removed without accounting for rel<strong>at</strong>iveproportions or nutrient composition.When presented with accur<strong>at</strong>e inform<strong>at</strong>ion, vegetarianscan fulfill all of their nutritional requirements in allstages of life. Many individuals would like to becomevegetarians because they are aware of the health benefits.However, these individuals are <strong>at</strong> a loss as to how to makethe transition when there are no appropri<strong>at</strong>e and easilyaccessible guides.Recently, a Vegetarian Food Guide Pyramid was introducedto the United St<strong>at</strong>es Congress by organizers ofthe Third Intern<strong>at</strong>ional Congress on Vegetarian <strong>Nutrition</strong>(Fig. 2). (15) The bottom tiers of the pyramidconsist of the five major plant-based food groups: wholegrains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds. At thetop of the pyramid are the foods th<strong>at</strong> may or may not beincluded in a vegetarian diet: vegetable oil, dairy, eggs,and sweets. The hope is th<strong>at</strong> this provisional guide willmotiv<strong>at</strong>e additional research and development of futureguides. (15)Involving the FamilyAnother opportunity to counsel adolescent vegetarianscomes about because of an adolescent’s impulsivity. Suddenchanges in diet for newly converted adolescent vegetariansoften are not accompanied by a change in theirfamilies’ e<strong>at</strong>ing habits. Many families tend to be acceptingof their child’s new e<strong>at</strong>ing habits, but provisions arenot always made to help the child receive the nutritionth<strong>at</strong> he or she needs. The new vegetarian adolescentdescribed in the case reports e<strong>at</strong>ing “side dishes” <strong>at</strong> thefamily meal. The most common reason for e<strong>at</strong>ing onlye6 <strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

nutritionvegetarian dietsFigure 2. Vegetarian Food Guide Pyramid, depicting the specific food groups th<strong>at</strong> may be included in a vegetarian diet along withthe appropri<strong>at</strong>e food proportions for each food group. The Dairy, Eggs, and Sweets c<strong>at</strong>egories are optional. Modified from Haddadet al. (15)“side dishes” is th<strong>at</strong> the main dish usually is an animal orfish product. Many families assume th<strong>at</strong> their vegetarianchild is going through a phase and soon will return to ame<strong>at</strong>-based diet.Although most adolescents no longer depend solelyon their families for food, it still is important to educ<strong>at</strong>eTable 3. Available ResourcesUnited St<strong>at</strong>es Department of AgricultureMyPyramid.govLocal Farmers’ Marketshttp://www.ams.usda.gov/farmersmarkets/Vegetarian Resource Groupwww.vrg.orgVegetarian Children and AdolescentsVegetarianteen.comVegetarian Restaurants Around the WorldVegdining.comparents and siblings about vegetarianism and availableresources (Table 3). Families should not be expected tochange their e<strong>at</strong>ing habits, but it is important th<strong>at</strong> appropri<strong>at</strong>efoods be available for the vegetarian child. Wellinformedparents can guide vegetarian adolescents whoare having difficulty adapting to their new dietary restrictions.Vegetarian adolescents commonly e<strong>at</strong> foods out ofconvenience, such as pasta and bagels. It is important tostress th<strong>at</strong> these foods may be me<strong>at</strong>less, but they do notprovide adequ<strong>at</strong>e nutrition. It also is important to stressth<strong>at</strong> adolescent vegetarians need to be aware of nutritionalinform<strong>at</strong>ion for preprepared vegetarian meals.Vegetarians often have the misconception th<strong>at</strong> certainfoods must be healthy because they contain productssuch as tofu or tempeh. As with any food, assessingnutritional inform<strong>at</strong>ion concerning f<strong>at</strong>, sodium, calories,and sugar is important.Potential Disorders in the AdolescentVegetarianAn important point th<strong>at</strong> often can be the most difficult toelicit is whether an adolescent’s choice to be a vegetarianis a form of restriction. Is it possible th<strong>at</strong> vegetarianism<strong>Pedi<strong>at</strong>rics</strong> in Review Vol.30 No.1 January 2009 e7Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublic<strong>at</strong>ions.org/ <strong>at</strong> N<strong>at</strong>ional Naval Medical Center (NNMC) on August 12, 2011

COVER ARTICLEPROBLEM-ORIENTED DIAGNOSISDiagnosis of E<strong>at</strong>ing Disordersin Primary CareSARAH D. PRITTS, M.D., and JEFFREY SUSMAN, M.D.University of Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i College of Medicine, Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i, OhioE<strong>at</strong>ing disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, are significantcauses of morbidity and mortality among adolescent females and young women. E<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders are associ<strong>at</strong>ed with devast<strong>at</strong>ing medical and psychologic consequences,including de<strong>at</strong>h, osteoporosis, growth delay, and developmental delay. Prompt diagnosisis linked to better outcomes. A good medical history is the most powerful tool.Simple screening questions, such as “Do you think you should be dieting?” can be integr<strong>at</strong>edinto routine visits. Physical findings such as low body mass index, amenorrhea,bradycardia, gastrointestinal disturbances, skin changes, and changes in dentition canhelp detect e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders. Labor<strong>at</strong>ory studies can help diagnose these conditionsand exclude underlying medical conditions. The family physician can play an importantrole in diagnosing these illnesses and can coordin<strong>at</strong>e the multidisciplinary team of psychi<strong>at</strong>rists,nutritionists, and other professionals to successfully tre<strong>at</strong> p<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders. (Am Fam Physician 2003;67:297-304,311-2. Copyright© 2003 AmericanAcademy of Family Physicians.)O A p<strong>at</strong>ient inform<strong>at</strong>ionhandout aboute<strong>at</strong>ing disorders, writtenby the authors ofthis article, is providedon page 311.Members of variousfamily practice departmentsdevelop articlesfor “Problem-OrientedDiagnosis.” This is onein a series from theDepartment of FamilyMedicine <strong>at</strong> the Universityof Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i Collegeof Medicine.Guest coordin<strong>at</strong>or ofthe series is SusanMontauk, M.D.See page 237 for definitionsof strength-ofevidencelevels.E<strong>at</strong>ing disorders are amongthe most common psychi<strong>at</strong>ricproblems th<strong>at</strong> affectyoung women, 1 and theseconditions impose a highburden of morbidity and mortality.Unfortun<strong>at</strong>ely, the diagnosis of e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders can be elusive, and more thanone half of all cases go undetected. 2 Thefamily physician’s office is an ideal settingto identify e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders and initi<strong>at</strong>etre<strong>at</strong>ment in a timely fashion. This reviewfocuses on recognition and diagnosis ofe<strong>at</strong>ing disorders in primary care. A comprehensivereview of tre<strong>at</strong>ment and otheraspects of these conditions is available inthe American Psychi<strong>at</strong>ric Associ<strong>at</strong>ion’spractice guideline on the tre<strong>at</strong>ment ofe<strong>at</strong>ing disorders. 3EpidemiologyE<strong>at</strong>ing disorders occur most commonlyin adolescents and young adults and are10 times more common in females thanin males. They occur in all ethnic groupsbut are most common among whites inindustrialized n<strong>at</strong>ions. The principal e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders are anorexia nervosa,bulimia nervosa, and nonspecified e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorder. Anorexia has two subtypes—restricting type and binge-e<strong>at</strong>ing/purgingtype. Bulimia also has two subtypes—purging and nonpurging.In young women, the risk of developinganorexia is 0.5 to 1 percent, andmortality is estim<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>at</strong> 4 to 10 percent.4,5 In the same popul<strong>at</strong>ion, the riskof developing bulimia is 2 to 5 percent, 1,6and the incidence of disordered e<strong>at</strong>ingth<strong>at</strong> does not meet strict criteria for e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders may be twice th<strong>at</strong> of theabove conditions. 2 Frequent dieting anddesire for weight loss occur much morecommonly than overt e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders.In 1999, the Youth Risk Behavior SurveillanceSurvey 7 reported th<strong>at</strong> 58 percentof students in the United St<strong>at</strong>es hadexercised to lose weight, and 40 percentof students had restricted caloric intakein an <strong>at</strong>tempt to lose weight. Many adolescentsand young adults who do notmeet the strict diagnostic criteria fore<strong>at</strong>ing disorders have disordered e<strong>at</strong>ingp<strong>at</strong>terns, which can have a significantadverse impact on health. The distinctionbetween normal dieting and disor-JANUARY 15, 2003 / VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 297

It is important to aggressively tre<strong>at</strong> p<strong>at</strong>ients who have traitsof e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders but who do not meet the full criteriafor anorexia or bulimia.TABLE 1Diagnostic Criteria for Anorexia Nervosadered e<strong>at</strong>ing is based on whether the p<strong>at</strong>ienthas a distorted body image.EtiologyRisk factors for developing an e<strong>at</strong>ing disorderinclude particip<strong>at</strong>ion in activities th<strong>at</strong> promotethinness, such as ballet dancing, modeling,and <strong>at</strong>hletics, 4 and certain personalitytraits, such as low self-esteem, difficultyexpressing neg<strong>at</strong>ive emotions, difficultyresolving conflict, and being a perfectionist. 1E<strong>at</strong>ing disorders are particularly common inA. Refusal to maintain body weight <strong>at</strong> or above a minimally normal weightfor age and height (e.g., weight loss leading to body weight less than85 percent of th<strong>at</strong> expected; or failure to make expected weight gainduring period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85 percent ofth<strong>at</strong> expected)B. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming overweight, even though p<strong>at</strong>ientis underweightC. Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced,undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evalu<strong>at</strong>ion, or denial of theseriousness of the current low body weightD. Amenorrhea in postmenarchal females (i.e., the absence of <strong>at</strong> least threeconsecutive menstrual cycles. A woman is considered to have amenorrheaif her periods occur only following hormone administr<strong>at</strong>ion.)Specify type:Restricting type: during the current episode, the p<strong>at</strong>ient has not regularlyengaged in binge e<strong>at</strong>ing or purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting or the misuseof lax<strong>at</strong>ives, diuretics, or enemas)Binge-e<strong>at</strong>ing/purging type: during the current episode, the p<strong>at</strong>ient hasregularly engaged in binge e<strong>at</strong>ing or purgingReprinted with permission from Diagnostic and St<strong>at</strong>istical Manual of Mental Disorders.4th ed, text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychi<strong>at</strong>ric Associ<strong>at</strong>ion,2000:589.young women with type 1 diabetes mellitus.Up to one third of women with type 1 diabetesmay have e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders, and thesewomen are <strong>at</strong> especially high risk of microvascularand metabolic complic<strong>at</strong>ions. 8The role of family history in the developmentof e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders is not clear. Somestudies 9 of twins demonstr<strong>at</strong>e a strong link,and others demonstr<strong>at</strong>e no correl<strong>at</strong>ion. Afamily history of mood disorders in a firstdegreerel<strong>at</strong>ive also might be a risk factor. 5DiagnosisEarly diagnosis with intervention and earlierage <strong>at</strong> diagnosis are correl<strong>at</strong>ed withimproved outcomes in p<strong>at</strong>ients who have e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders. 5 Because family physicians serveas primary care providers for a large percentageof adolescents, they have an importantrole in diagnosing these disorders.The hallmark of anorexia is a refusal tomaintain body weight <strong>at</strong> or above 85 percentof expected weight, as defined by age-appropri<strong>at</strong>ebody mass index charts. P<strong>at</strong>ients withanorexia use caloric restriction or excessiveexercise to control emotional need or pain,and they are terrified of becoming overweight.P<strong>at</strong>ients with nonpurging-type bulimia alsomight severely restrict calories or exerciseexcessively to lose weight but do not meet theweight criteria for diagnosis of anorexia.Bulimia is characterized by uncontrollablebinge-e<strong>at</strong>ing episodes, often followed by purgingbehaviors such as vomiting or the use oflax<strong>at</strong>ives. P<strong>at</strong>ients with binge-e<strong>at</strong>ing/purgingtypeanorexia also might binge and purge.P<strong>at</strong>ients who have bulimia may be of normalweight, or they may be under- or overweight,whereas p<strong>at</strong>ients with binge-e<strong>at</strong>ing/purgingtypeanorexia are underweight.Both of the major e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders are characterizedby a disturbance in the perception ofbody shape, which is closely tied to self-image.Summaries of diagnostic criteria for anorexiaand bulimia are provided in Tables 1 and 2. 10It is also important to aggressively tre<strong>at</strong>p<strong>at</strong>ients who have traits of e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders298 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 / JANUARY 15, 2003

E<strong>at</strong>ing Disordersbut who do not meet the full criteria foranorexia or bulimia. 11Differential DiagnosisA wide variety of medical problems canmasquerade as e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders. Hyperthyroidism,malignancy, inflamm<strong>at</strong>ory bowel disease,immunodeficiency, malabsorption,chronic infections, Addison’s disease, and diabetesshould be considered before making adiagnosis of an e<strong>at</strong>ing disorder. Most p<strong>at</strong>ientswith a medical condition th<strong>at</strong> leads to e<strong>at</strong>ingproblems express concern over their weightloss. However, p<strong>at</strong>ients with an e<strong>at</strong>ing disorderhave a distorted body image and express adesire to be underweight. 10Psychi<strong>at</strong>ric comorbidity is extremely common;illnesses such as affective disorders, obsessive-compulsivedisorder, som<strong>at</strong>iz<strong>at</strong>ion disorder,and substance abuse must be consideredwhen p<strong>at</strong>ients present with such symptoms. 12Major depression is the most commoncomorbid condition among p<strong>at</strong>ients withanorexia, with a lifetime risk as high as 80 percent.5 Anxiety disorders, especially social phobia,also are common. 5 Obsessive-compulsivedisorder has a prevalence of 30 percent amongp<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders. 13 Substanceabuse prevalence is estim<strong>at</strong>ed <strong>at</strong> 12 to 18 percentin p<strong>at</strong>ients with anorexia and 30 to 70 percentin p<strong>at</strong>ients with bulimia. 14Personality disorders (Axis II diagnoses)also are common, with comorbidity r<strong>at</strong>esreported <strong>at</strong> 21 to 97 percent. 15 The wide rangeis rel<strong>at</strong>ed to the complexity of evalu<strong>at</strong>ing thesediagnoses. P<strong>at</strong>ients with bulimia are morelikely to have a cluster B diagnosis (dram<strong>at</strong>ic/err<strong>at</strong>ic), whereas p<strong>at</strong>ients with anorexia aremore likely to have a cluster C diagnosis(avoidant/anxious). 15Screening ToolsAll p<strong>at</strong>ients in high-risk c<strong>at</strong>egories for e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders should be screened during routineoffice visits. 16 The medical history is themost powerful tool for diagnosing e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders.Physical examin<strong>at</strong>ion and labor<strong>at</strong>oryP<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders have very high r<strong>at</strong>es of comorbidpsychi<strong>at</strong>ric conditions.findings might be normal, especially early inthe course of e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders.A number of comprehensive psychi<strong>at</strong>ricinterviews can be used to diagnose e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders,17,18 but these are impractical in the primarycare setting. One promising screeningtool is the SCOFF questionnaire (Table 3). 19Because of its 12.5 percent false-positive r<strong>at</strong>e,this test is not sufficiently accur<strong>at</strong>e for diagnosinge<strong>at</strong>ing disorders, but it is an appropri<strong>at</strong>escreening tool.TABLE 2Diagnostic Criteria for Bulimia NervosaA. Recurrent episodes of binge e<strong>at</strong>ing. An episode of binge e<strong>at</strong>ing ischaracterized by both of the following:(1) In a discrete period of time (e.g., within any two-hour period), e<strong>at</strong>ing anamount of food th<strong>at</strong> is larger than wh<strong>at</strong> most people would e<strong>at</strong> during asimilar period of time and under similar circumstances(2) A sense of lack of control over e<strong>at</strong>ing during the episodeB. Recurrent inappropri<strong>at</strong>e compens<strong>at</strong>ory behavior in order to prevent weightgain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of lax<strong>at</strong>ives, diuretics, enemas,or other medic<strong>at</strong>ions; fasting; or exercising excessivelyC. The binge e<strong>at</strong>ing and inappropri<strong>at</strong>e compens<strong>at</strong>ory behaviors both occur, onaverage, <strong>at</strong> least twice a week for three monthsD. Self-evalu<strong>at</strong>ion is unduly influenced by body shape and weightE. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexianervosaSpecify type:Purging type: during the current episode, the p<strong>at</strong>ient has regularly engaged inself-induced vomiting or the misuse of lax<strong>at</strong>ives, diuretics, or enemasNonpurging type: during the current episode, the p<strong>at</strong>ient has used inappropri<strong>at</strong>ecompens<strong>at</strong>ory behaviors, such as fasting or exercising excessively, buthas not regularly engaged in self-induced vomiting or the use of lax<strong>at</strong>ives,diuretics, or enemasReprinted with permission from Diagnostic and St<strong>at</strong>istical Manual of Mental Disorders.4th ed, text revision. Washington, D.C.: American Psychi<strong>at</strong>ric Associ<strong>at</strong>ion,2000:594.JANUARY 15, 2003 / VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 299

TABLE 3SCOFF QuestionsDo you make yourself Sick (induce vomiting)because you feel uncomfortably full?Do you worry th<strong>at</strong> you have lost Control over howmuch you e<strong>at</strong>?Have you recently lost more than One stone(14 lb [6.4 kg]) in a three-month period?Do you think you are too F<strong>at</strong>, even though otherssay you are too thin?Would you say th<strong>at</strong> Food domin<strong>at</strong>es your life?One point for every yes answer; a score ≥ 2 indic<strong>at</strong>esa likely case of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa(sensitivity: 100 percent; specificity: 87.5 percent).Reprinted with permission from Morgan JF, Reid F,Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of anew screening tool for e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders. BMJ 1999;319:1467.Other screening questions th<strong>at</strong> might behelpful are listed in Table 4. 18,20 Positiveresponses to any of these questions shouldprompt further investig<strong>at</strong>ion with a morecomprehensive questionnaire. When screeningp<strong>at</strong>ients, it is important to take their developmentalstage into account; some questionsmight be inappropri<strong>at</strong>e for younger p<strong>at</strong>ients.History and Presenting SymptomsP<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders can have awide range of symptoms. Those with milderillness might have nonspecific complaints,such as f<strong>at</strong>igue, dizziness, or lack of energy. 4P<strong>at</strong>ients might deny th<strong>at</strong> they have symptoms,but their family members mightexpress concern. P<strong>at</strong>ients who have anorexi<strong>at</strong>ypically will be unconcerned about significantweight loss. Other symptoms th<strong>at</strong> mightbe reported or elicited include amenorrhea,sore thro<strong>at</strong>, gastroesophageal reflux disease,abdominal pain, cold intolerance, constip<strong>at</strong>ion,polyuria, polydipsia, and palpit<strong>at</strong>ions.When taking a medical history, it is alsoimportant to take a dietary history to askabout the use of lax<strong>at</strong>ives or diuretics. Table 5compares important clinical fe<strong>at</strong>ures ofanorexia and bulimia.When obtaining a history, it is important toestablish trust and rapport with the p<strong>at</strong>ient,especially when the p<strong>at</strong>ient does not perceive aproblem. Talking to the family and p<strong>at</strong>ienttogether, as well as talking to the p<strong>at</strong>ient individually,is appropri<strong>at</strong>e. If the p<strong>at</strong>ient is anadolescent, questions must be asked in adevelopmentally appropri<strong>at</strong>e, precise, nonjudgmentalway. 21Physical Examin<strong>at</strong>ionComplic<strong>at</strong>ions of anorexia and bulimia canaffect nearly every organ system. However,many p<strong>at</strong>ients might have a completely normalphysical examin<strong>at</strong>ion, especially early inthe disorder. It is important to explain top<strong>at</strong>ients and their families th<strong>at</strong> a normal physicalexamin<strong>at</strong>ion does not rule out an e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorder.Accur<strong>at</strong>e weight measurements are importantin diagnosing an e<strong>at</strong>ing disorder. Abnormalgrowth curves, especially in children andadolescents, can be revealing. A p<strong>at</strong>ient whoTABLE 4Suggested Screening Questions forAnorexia Nervosa and Bulimia NervosaHow many diets have you been on in the past year?Do you think you should be dieting?Are you diss<strong>at</strong>isfied with your body size?Does your weight affect the way you think aboutyourself?A positive response to any of these questions warrantsfurther evalu<strong>at</strong>ion.Inform<strong>at</strong>ion from Anstine D, Grinenko D. Rapidscreening for disordered e<strong>at</strong>ing in college-agedfemales in the primary care setting. J Adolesc Health2000;26:338-42.300 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 / JANUARY 15, 2003

E<strong>at</strong>ing DisordersTo avoid revealing their true weight, some p<strong>at</strong>ients withe<strong>at</strong>ing disorders might drink extra fluids, put weights intheir pockets, or wear layers of heavy clothing beforebeing weighed.initially had normal growth parameters mightstop gaining weight or might lose weight whileheight increases. Eventually, height will beaffected, and growth will diminish.To obtain accur<strong>at</strong>e weight measurements,office staff must be trained to use standardizedprotocols to record consistent, reliable measurements.Scales should be loc<strong>at</strong>ed in a priv<strong>at</strong>earea, and comments about weight shouldbe minimized and made discreetly. Staffshould be aware th<strong>at</strong> some p<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders, to avoid revealing their trueweight, might drink extra fluids, put weightsin their pockets, or wear layers of heavy clothingbefore being weighed. 1Vital signs might be abnormal, such asbradycardia, orthost<strong>at</strong>ic hypotension, andhypothermia. Abnormal skin findingsinclude dry skin, loss of subcutaneous f<strong>at</strong>,lanugo (fine body hair), and hypercarotenemia(an orange hue caused by increasedingestion of carrots). P<strong>at</strong>ients who inducevomiting might have calluses on the dorsumof the dominant hand, as well as loss of dentalenamel. Salivary gland enlargement isanother sign of purging behavior.Pulmonary complic<strong>at</strong>ions of e<strong>at</strong>ing disordersare rare, but vomiting can cause a pneumomediastinum.Pulmonary edema mayoccur in p<strong>at</strong>ients who undergo refeeding. Inaddition to bradycardia, cardiac findings mayinclude acrocyanosis and decrease in overallheart size and stroke volume. Cardiomegalycan indic<strong>at</strong>e ipecac use. Electrocardiogramfindings may include bradycardia, prolongedQT interval, and nonspecific ST-T changes.The gastrointestinal system also can beadversely affected. There can be decreasedbowel motility, leading to abdominal distension.Gastroesophageal reflux and pancre<strong>at</strong>itisTABLE 5A Comparison of Fe<strong>at</strong>ures of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia NervosaFe<strong>at</strong>ures Anorexia nervosa Bulimia nervosaHistory and Amenorrhea, constip<strong>at</strong>ion, headaches, Blo<strong>at</strong>ing, fullness, lethargy, GERD,symptoms fainting, dizziness, f<strong>at</strong>igue, cold abdominal pain, sore thro<strong>at</strong>intolerance(from vomiting)Physical findings Cachexia, acrocyanosis, dry skin, hair loss, Knuckle calluses, dental enamelbradycardia, orthost<strong>at</strong>ic hypotension, erosion, salivary gland enlargement,hypothermia, loss of muscle mass and cardiomegaly (ipecac toxicity)subcutaneous f<strong>at</strong>, lanugoLabor<strong>at</strong>ory Hypoglycemia, leukopenia, elev<strong>at</strong>ed Hypochloremic, hypokalemic, or metabolicabnormalities liver enzymes, euthyroid sick syndrome alkalosis (from vomiting), hypokalemia(low TSH level, normal T 3 , T 4 levels) (from lax<strong>at</strong>ives or diuretics), elev<strong>at</strong>edsalivary amylase (might also be presentin binging/purging subtype of anorexia)ECG findings Low voltage; prolonged QT interval, Low voltage; prolonged QT interval,bradycardiabradycardiaGERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; TSH = thyroid-stimul<strong>at</strong>ing hormone; T 3 = triiodothyronine; T 4 = thyroxine;ECG = electrocardiogram.JANUARY 15, 2003 / VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 301

The Authorscan cause epigastric pain. If the p<strong>at</strong>ient is constip<strong>at</strong>ed,stool might be palpable in the leftlower quadrant.Labor<strong>at</strong>ory Evalu<strong>at</strong>ionLabor<strong>at</strong>ory findings might be completelynormal, but targeted labor<strong>at</strong>ory testing can behelpful to rule out medical illness. In p<strong>at</strong>ientswho have e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders, the completeblood cell count might be normal, butleukopenia is not uncommon, probablybecause of increased margin<strong>at</strong>ion of neutrophils.Immune function does not appearto be impaired. In severe cases, pancytopeniamight be present. 12 Blood glucose levelsmight be low. 2 Hypochloremic, hypokalemic,or metabolic alkalosis might be present inp<strong>at</strong>ients who purge. Hypokalemia also mightresult from diuretic and lax<strong>at</strong>ive use. Severehypokalemia might lead to cardiac arrhythmias,muscle weakness, or confusion. Hypon<strong>at</strong>remiamight occur with excessive w<strong>at</strong>erintake. Thyroid-function test findings mightbe consistent with the euthyroid sick syndrome,with low triiodothyronine and thyroxinelevels and a normal thyroid-stimul<strong>at</strong>inghormone level.Osteopenia in e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders can resultfrom several factors. Decreased estrogen levelsand inadequ<strong>at</strong>e micronutrients, especiallyduring adolescence when bone strength istypically increasing, can lead to clinically significantosteopenia after as few as six monthsSARAH D. PRITTS, M.D., is assistant professor of clinical family medicine and a memberof the predoctoral faculty <strong>at</strong> the University of Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i College of Medicine. Shereceived her medical degree from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine,Chicago, and completed a residency in family medicine <strong>at</strong> the University ofCincinn<strong>at</strong>i/Mercy-Franciscan Mt. Airy Hospitals.JEFFREY SUSMAN, M.D., is professor of family medicine and director of the Departmentof Family Medicine <strong>at</strong> the University of Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i College of Medicine. Hereceived his medical degree from Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, N.H., and completedhis residency <strong>at</strong> Lancaster General Hospital, Lancaster, Pa.Address correspondence to Sarah D. Pritts, M.D., University of Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i Medical Center,Department of Family Medicine, P.O. Box 670582, Cincinn<strong>at</strong>i, OH 45267-0582(e-mail: prittssd@fammed.uc.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.of illness. 2 It is worthwhile to obtain dualenergyx-ray absorptiometry scans after sixmonths of amenorrhea in p<strong>at</strong>ients withanorexia and in p<strong>at</strong>ients with bulimia whohave a history of anorexia. 12Tre<strong>at</strong>mentTre<strong>at</strong>ment intensity and setting depend onthe severity of the illness. P<strong>at</strong>ients with mild illnesscan be managed on an outp<strong>at</strong>ient basis.P<strong>at</strong>ients who are medically or psychi<strong>at</strong>ricallyunstable require inp<strong>at</strong>ient tre<strong>at</strong>ment (Table 6). 3[Evidence level C, expert opinion] Tre<strong>at</strong>mentgoals include <strong>at</strong>tainment and maintenance ofa healthy weight, management of physicalcomplic<strong>at</strong>ions, management of comorbidpsychi<strong>at</strong>ric illness, and prevention of relapse.Eliciting cooper<strong>at</strong>ion from the p<strong>at</strong>ient, helpingto change maladaptive thoughts, and educ<strong>at</strong>ingthe p<strong>at</strong>ient about proper health andnutrition also are important. 3Adequ<strong>at</strong>e tre<strong>at</strong>ment of e<strong>at</strong>ing disordersrequires a multidisciplinary team approach.The family physician can and should be anintegral member of th<strong>at</strong> team. Early in the illness,frequent visits to the primary care physician’soffice are helpful for surveillance ofmedical conditions, as well as for nutritionalre-educ<strong>at</strong>ion. The family physician also will beindispensable in the role of coordin<strong>at</strong>ing theentire team of professionals involved in thep<strong>at</strong>ient’s care.PrognosisThe prognosis of p<strong>at</strong>ients who have e<strong>at</strong>ingdisorders is variable. The general consensus isth<strong>at</strong> 50 percent of p<strong>at</strong>ients with anorexia havegood outcomes, 30 percent have intermedi<strong>at</strong>eoutcomes, and 20 percent have poor outcomes.The percentages are similar in bulimicp<strong>at</strong>ients, with 45 percent having good outcomes,18 percent having intermedi<strong>at</strong>e outcomes,and 21 percent having poor outcomes.P<strong>at</strong>ients with anorexia have a mortality r<strong>at</strong>esix times th<strong>at</strong> of peers without anorexia. 5Factors th<strong>at</strong> predict improved outcomes fore<strong>at</strong>ing disorders include early age <strong>at</strong> diagnosis,302 AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN www.aafp.org/afp VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 / JANUARY 15, 2003

E<strong>at</strong>ing DisordersTABLE 6Level-of-Care Criteria for P<strong>at</strong>ients with E<strong>at</strong>ing DisordersLevel 2:Level 1: Intensive Level 3: Level 4: Level 5:Characteristic Outp<strong>at</strong>ient outp<strong>at</strong>ient Full-day outp<strong>at</strong>ient Residential tre<strong>at</strong>ment center Inp<strong>at</strong>ient hospitaliz<strong>at</strong>ionMedical complic<strong>at</strong>ions Medically stable to the extent th<strong>at</strong> more extensive monitoring, Medically stable (not Adults: HR < 40 be<strong>at</strong>s peras defined in Levels 4 and 5, is not required requiring NG feeds, minute; BP < 90/60 mm Hg;IV fluids, or multiple glucose < 60 mg per dLdaily labor<strong>at</strong>ories)(3.3 mmol per L); K + 85 percent > 80 percent > 70 percent < 85 percent Adults: < 75 percentof healthy body weightChildren and adolescents:acute weight decline withfood refusalMotiv<strong>at</strong>ion to recover Good to fair Fair Partial; preoccupied Fair to poor; preoccupied Poor to very poor; preoccupied(cooper<strong>at</strong>iveness, insight, with ego-syntonic with ego-syntonic with ego-syntonic thoughts;ability to control thoughts more thoughts 4 to 6 hours per uncooper<strong>at</strong>ive with tre<strong>at</strong>mentobsessive thoughts) than 3 hours per day; cooper<strong>at</strong>ive with or cooper<strong>at</strong>ive only withday; cooper<strong>at</strong>ive highly structured tre<strong>at</strong>ment highly structured environmentComorbid disorders Presence of comorbid condition may influence choice of level of care Any existing psychi<strong>at</strong>ric disorder(substance abuse,th<strong>at</strong> would requiredepression, anxiety)hospitaliz<strong>at</strong>ionStructure needed for Self-sufficient Needs some structure Needs supervision <strong>at</strong> all Needs supervision during ande<strong>at</strong>ing/gaining weight to gain weight meals or will restrict after all meals, or NG/speciale<strong>at</strong>ingfeedingImpairment and ability Able to exercise for fitness; able to Structure required Complete role impairment, cannot e<strong>at</strong> and gain weight byto care for self; ability control obsessive exercise to prevent self; structure required to prevent p<strong>at</strong>ient from compulsiveto control exercise excessive exercise exercisingPurging behavior Can gre<strong>at</strong>ly reduce purging in nonstructured settings; no Can ask for and use support Needs supervision during and(lax<strong>at</strong>ives and diuretics) significant medical complic<strong>at</strong>ions, such as ECG abnormalities or skills if desires to purge after all meals and inor others suggesting the need for hospitaliz<strong>at</strong>ionb<strong>at</strong>hroomsEnvironmental stress Others able to provide adequ<strong>at</strong>e Others able to Severe family conflict, problems, or absence so as unable toemotional and practical support provide <strong>at</strong> least provide structured tre<strong>at</strong>ment in home, or lives aloneand structure limited support without adequ<strong>at</strong>e support systemand structureTre<strong>at</strong>ment availability/ Lives near tre<strong>at</strong>ment setting Too distant to live <strong>at</strong> homeliving situ<strong>at</strong>ionNG = nasogastric; IV = intravenous; HR = heart r<strong>at</strong>e; BP = blood pressure; K + = potassium level; ECG = electrocardiogram.Adapted with permission from Practice guideline for the tre<strong>at</strong>ment of p<strong>at</strong>ients with e<strong>at</strong>ing disorders (revision). American Psychi<strong>at</strong>ric Associ<strong>at</strong>ion Work Groupon E<strong>at</strong>ing Disorders. Am J Psychi<strong>at</strong>ry 2000;157(suppl 1):20.brief interval before initi<strong>at</strong>ion of tre<strong>at</strong>ment,good parent-child rel<strong>at</strong>ionships, and havingother healthy rel<strong>at</strong>ionships with friends ortherapists. 5Because of the severity of these illnesses andthe improvement in outcomes when diagnosisoccurs earlier, the family physician can play acrucial role in helping p<strong>at</strong>ients recover frome<strong>at</strong>ing disorders by detecting them <strong>at</strong> an earlystage.JANUARY 15, 2003 / VOLUME 67, NUMBER 2 www.aafp.org/afp AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN 303