Paper 89 - Square Circles Publishing

Paper 89 - Square Circles Publishing

Paper 89 - Square Circles Publishing

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

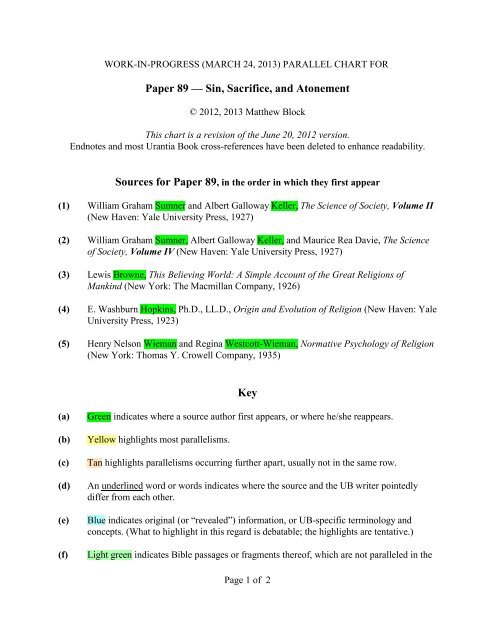

WORK-IN-PROGRESS (MARCH 24, 2013) PARALLEL CHART FOR<strong>Paper</strong> <strong>89</strong> — Sin, Sacrifice, and Atonement© 2012, 2013 Matthew BlockThis chart is a revision of the June 20, 2012 version.Endnotes and most Urantia Book cross-references have been deleted to enhance readability.Sources for <strong>Paper</strong> <strong>89</strong>, in the order in which they first appear(1) William Graham Sumner and Albert Galloway Keller, The Science of Society, Volume II(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927)(2) William Graham Sumner, Albert Galloway Keller, and Maurice Rea Davie, The Scienceof Society, Volume IV (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927)(3) Lewis Browne, This Believing World: A Simple Account of the Great Religions ofMankind (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1926)(4) E. Washburn Hopkins, Ph.D., LL.D., Origin and Evolution of Religion (New Haven: YaleUniversity Press, 1923)(5) Henry Nelson Wieman and Regina Westcott-Wieman, Normative Psychology of Religion(New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1935)Key(a)(b)(c)(d)(e)(f)Green indicates where a source author first appears, or where he/she reappears.Yellow highlights most parallelisms.Tan highlights parallelisms occurring further apart, usually not in the same row.An underlined word or words indicates where the source and the UB writer pointedlydiffer from each other.Blue indicates original (or “revealed”) information, or UB-specific terminology andconcepts. (What to highlight in this regard is debatable; the highlights are tentative.)Light green indicates Bible passages or fragments thereof, which are not paralleled in thePage 1 of 2

source texts.Matthew Block24 March 2013Page 2 of 2

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Work-in-progress Version 20 June 2012© 2012 Matthew BlockRevised 24 Mar. 2013PAPER <strong>89</strong> — SIN ,S A C R I F I C E , A N DATONEMENTXXXVI: HUMAN SACRIFICE (Sumner& Keller 1251)§295.* Redemption and Covenant. (Sumner& Keller 1263)One of the widest phases of religioussentiment represents all men as underdebt to the spirits.<strong>89</strong>:0.1 Primitive man regarded himselfas being in debt to the spirits,as standing in need of redemption.This may be merely because the latterhave held off and not inflicted damagewhen they might have done so (S&K1263).As the savages looked at it, in justice thespirits might have visited much more badluck upon them.As time passed, this concept developedinto the doctrine of sin and salvation.The thing to be bought off or ransomed isnot infrequently life itself; the ransomedsoul is a more developed conception. It isas if life comes into the world underforfeit, by reason of some originalobligation or “original sin”.The soul was looked upon as coming intothe world under forfeit—original sin.The soul must be ransomed;This topic is closely allied to that ofthe scape-goat (S&K 1263).Head-hunting, besides being a result ofskull-worship, also provides a substitutefor one’s own life (S&K 1264).a scapegoat must be provided.The head-hunter, in addition to practicingthe cult of skull worship, was able toprovide a substitute for his own life, ascapeman.1

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>XXXIII: PROPITIATION (Sumner &Keller 1167)§278. Nature of Propitiation. (Sumner &Keller 1167)<strong>89</strong>:0.2 The savage was early possessedwith the notion thatNudity, again, though it seems to begenerally coercitive, is often interpretableas propitiatory, for the daimons getsatisfaction out of the sight of humanmisery, humiliation, and self-discipline(S&K 1168).The faults hitherto considered have beenalmost wholly those of commission:something wrong has been done; sometaboo broken (S&K 1170).It is also necessary to perform positivecult-obligations and to incur no guilt byreason of omissions; for the daimons havemight-supported rights that rootultimately in the supposed needs of theghosts (S&K 1170).spirits derive supreme satisfaction fromthe sight of human misery, suffering, andhumiliation.At first, man was only concerned withsins of commission,but later he became exercised over sins ofomission.And the whole subsequent sacrificialsystem grew up around these two ideas.Whatever the nature of the sin,whether of commission or of omission,there was but one recourse for the sinnerif he were to evade or lessen the penalty:conciliation or propitiation (S&K 1170).Misfortune will come of itself unlesssomething is done to prevent it, whereasfortune will not arrive unless something isdone to bring it (S&K 1167).Considerable development is called forbefore people arrive at the idea of aconsistently benevolent god (S&K 1167).This new ritual had to do with theobservance of the propitiation ceremoniesof sacrifice.Primitive man believed that somethingspecial must be done to win the favor ofthe gods;only advanced civilization recognizes aconsistently even-tempered andbenevolent God.2

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Propitiation, in fact, is rather a mode ofdodging great ill fortune throughacquiescing in an endurable, recurringpresent loss than it is a deliberate policyof getting good luck. It is insurance ratherthan investment (S&K 1167).It is to be noted in the cases that theline between coercion and conciliation isnot hard and fast; in fact, avoidance,exorcism, coercion, propitiation mergeinto one another (S&K 1168).Propitiation was insurance againstimmediate ill luck rather than investmentin future bliss.And the rituals of avoidance, exorcism,coercion, and propitiation all merge intoone another.1. THE TABOOXXXI: THE TABOO (Sumner & Keller1095)§268.* Religious Nature of the Taboo.(Sumner & Keller 1095)The taboo is extended generally toprohibit what would bring bad luck; itproscribes words and names, days andseasons, attitudes and actions (S&K1098).What might offend the spirits or mightattract them when not wanted is theobject of strenuous taboo (S&K 1098).Some reputable writers do notrecognize the religious element in thetaboo: Finsch, for example, assigns it, asit appears on the Gilbert Islands, toeconomic necessity (S&K 1095-96).<strong>89</strong>:1.1 Observance of a taboo wasman’s effort to dodge ill luck,to keep from offending the spirit ghostsby the avoidance of something.The taboos were at first nonreligious,3

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>“A man being told to make a regularflight of steps to his house instead of theold notched ladder, replied ‘No, thatwould be pomali.’” Nothing is addedconcerning the reason of the taboo; ... if,however, the context is examined, in thiscase the Malay attitude toward pomali,there can be small doubt as to thedaimonic sanction (S&K 1096).but they early acquired ghost or spiritsanction,and when thus reinforced,§269. Societal Function. (Sumner & Keller1105)Within the society the taboo is thegreat institution-builder, for, as we haveseen, it cuts away at the amorphous massof folkways, eliminating this and that,until what is left shows a shape andconsistency that is more permanent andinstitutional (S&K 1108).In general it governs that aspect ofsocietal life called by Spencer“ceremonial” (S&K 1109).[See <strong>89</strong>:3.3, below.]Taboo was the primordial form of societalregulation; it reduced society to order forexpedient ends and thus gave it shape andconsistency (S&K 1107).“The system of tapu, so widelyspread throughout the islands of thePacific, was carried to its highest pitch ofdevelopment as a social law of the land ofthe Maori.... It was really the only lawsave that of the spear and the patu that theMaori possessed ...” (S&K 1103).they became lawmakers and institutionbuilders.The taboo is the source of ceremonialstandardsand the ancestor of primitive self-control.It was the earliest form of societalregulationand for a long time the only one;it is still a basic unit of the socialregulative structure.4

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>§268.* Religious Nature of the Taboo.(Sumner & Keller 1095)A taboo is a prohibition; but a prohibitionis just as strong as the power that issuesand guarantees it (S&K 1097).<strong>89</strong>:1.2 The respect which theseprohibitions commanded in the mind ofthe savage exactly equaled his fear of thepowers who were supposed to enforcethem.Taboos first arose because of chanceexperience with ill luck;Taboos are in fact generally imposed bythe chief or medicine-man, and both ofthese are fetish-men with indwellingspirits that speak and act through them(S&K 1097).later they were proposed by chiefs andshamans—fetish men who were thoughtto be directed by a spirit ghost, even by agod.The fear of spirit retribution is so great inthe mind of a primitive thatThe taboo, by its nature, does notadmit of experimental verification. Thenative does not dare, by ignoring it, tomake the test; or if by chance,involuntarily, he does, still he is morelikely to support the theory by promptlydying of fright than to live to note thenon-appearance of the consequences(S&K 1098).he sometimes dies of fright when he hasviolated a taboo, and this dramaticepisode enormously strengthens the holdof the taboo on the minds of thesurvivors.§270.* The Industrial Taboo. (Sumner &Keller 1109)Whatever is of economic value toprimitive societies, such as property andwomen, is subject to taboo (S&K 1110).<strong>89</strong>:1.3 Among the earliest prohibitionswere restrictions on the appropriation ofwomen and other property.§268.* Religious Nature of the Taboo.(Sumner & Keller 1095)As religion began to play a larger part inthe evolution of the taboo,The tabooed thing is likely to be“unclean” or “holy” or both at once, forthe two terms run together (S&K 1104).the article resting under ban was regardedas unclean, subsequently as unholy.5

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>There are many taboos mentioned inthe Old Testament, the most famousbeing that laid upon the tree of knowledge(S&K IV 581).The records of the Hebrews are full of themention of things clean and unclean, holyand unholy,but their beliefs along these lines were farless cumbersome and extensive than werethose of many other peoples.<strong>89</strong>:1.4 The seven commandments ofDalamatia and Eden, as well as“The ten commandments, as apprehendedby the white man in their ethical splendor,are not so apprehended by the black manwhen God ‘ties him with ten tyings’ inthe ‘early morning’ of his Christian day.They are not then to him the expressionsof ideals; they are facts, definite laws ofabstainings, of omission and commission.the ten injunctions of the Hebrews, weredefinite taboos,all expressed in the same negative form aswere the most ancient prohibitions.They are the Eldorado of taboo. Theyreplace with a great calm the agitations ofthe experimental efforts of the past, wheneverything was at stake and nothing wassure; when man was exhausted in hiseffort to fill his side of the contract, butmight never count upon the party of thesecond part. In this they areemancipating; they are the way of escapefrom a man-made yoke...” (S&K 1100).But these newer codes were trulyemancipating in that they took the placeof thousands of pre-existent taboos.And more than this, these latercommandments definitely promisedsomething in return for obedience.6

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>§271.* Food-Taboo. (Sumner & Keller 1114)In general, African food-taboos restupon irrational daimonistic notions andthere is more than an indication that theyare imposed chiefly upon the flesh offetish-animals. Since almost every tribehas its special tribal animal, there isprobably a considerable admixture oftotemism in the restrictive measures(S&K 1116).The Phœnicians were forbidden to eat theflesh of both swine and cows (S&K IV593).<strong>89</strong>:1.5 The early food taboos originatedin fetishism and totemism.The swine was sacred to the Phoenicians,the cow to the Hindus.[The flesh of certain holy or of certain particularlyunholy animals was considered taboo, andtherefore might not be eaten. (That primitivesuperstition is responsible for the aversion to porkwhich marked the ancient Egyptians, and stillmarks the Jews and Moslems.) (Browne 40)]“ ... In the island of Aurora, in the NewHebrides, mothers sometimes have afancy, before the birth of a child, that theinfant is connected in its origin with acocoanut or breadfruit, or some suchobject, a connection which the nativesexpress by saying that the children are akind of echo of such things.The child, therefore, is taught not to eatthat in which it has had its origin, and istold, what the mothers entirely believe,that to eat it will bring disease” (S&K IV584).It is not alone the food upon whichrestriction descends; the manner of eatingalso comes in for attention (S&K 1119).The Egyptian taboo on pork has beenperpetuated by the Hebraic and Islamicfaiths.A variant of the food taboo was the beliefthat a pregnant woman could think somuch about a certain food that the child,when born, would be the echo of thatfood.Such viands would be taboo to the child.<strong>89</strong>:1.6 Methods of eating soon becametaboo,7

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Such restrictions are the beginning notonly of decency, but even of etiquette andnicety of behavior; when their originaldaimonistic sense has long been lost, suchforms as covering the mouth in yawningor repressing a sneeze are reinterpreted onthe basis of delicacy of manners andconcern for the comfort of one’s fellows(S&K 1119).Social distinctions account for some ofthe food-taboos of the Atharaka ... (S&KIV 585). [See also S&K 1119-20.]and so originated ancient and moderntable etiquette.Caste systems and social levels arevestigial remnants of olden prohibitions.BOOK ONE: HOW IT ALL BEGAN(Browne 25)II: RELIGION (Browne 42)5. How religion made society possible—anddesirable—how it gave rise to art—the significanceof Primitive Religion. (Browne 54)Religion proved in time rather tooeffective a preservative.It sheltered too extensively andindiscriminately, keeping alive not merelythe morals necessary to the life of society,but also every scrap of ancient ritual andsavage taboo (B 54).But it is well to remember that, had it notbeen for religion and its underlying faiththat the universe and its fell “powers”could be controlled, there would not havebeen any civilization to frustrate (B 55).The taboos were highly effective inorganizing society, but they were terriblyburdensome;the negative-ban system not onlymaintained useful and constructiveregulations but also obsolete, outworn,and useless taboos.<strong>89</strong>:1.7 There would, however, be nocivilized society to sit in criticism uponprimitive man except for these far-flungand multifarious taboos, and the taboowould never have endured but for theupholding sanctions of primitive religion.8

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Many of the essential factors in man’sevolution have been highly expensive,have cost vast treasure in effort, sacrifice,and self-denial,Religion was the boot-strap by which manraised himself out of savagery.... In a veryreal sense it was his salvation. . . (B 55).but these achievements of self-controlwere the real rungs on which manclimbed civilization’s ascending ladder.2. THE CONCEPT OF SINXXXI: THE TABOO (Sumner & Keller1095)§273. Miscellaneous Taboos. (Sumner &Keller 1127)After all is said and done, the object ofevolving religion is insurance against thealeatory element,<strong>89</strong>:2.1 The fear of chance and the dreadof bad luck literally drove man into theinvention of primitive religion assupposed insurance against thesecalamities.From magic and ghosts, religion evolvedthrough spirits and fetishes to taboos.Every primitive tribe had its tree offorbidden fruit, literally the apple butfiguratively consisting of a thousandbranches hanging heavy with all sorts oftaboos. And the forbidden tree alwayssaid,and the methods pursued have beenconsistently and characteristically thoseof avoidance. But the taboo is the veryformulation of the avoidance-policy:Thou shalt not (S&K 1132).“Thou shalt not.”9

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>XXXII: SIN, EXORCISM, COERCION(Sumner & Keller 1133)§274.* Sin. (Sumner & Keller 1133)<strong>89</strong>:2.2 As the savage mind evolved tothat point where it envisaged both goodand bad spirits, and when the tabooreceived the solemn sanction of evolvingreligion, the stage was all set for theappearance of the new conception of sin.The idea of sin was universallyestablished in the world before revealedreligion ever made its entry.[See 86:3.3.]The man who has broken a taboo hassinned, and the wages of sin must beapportioned to him. One tree in Eden wasput under taboo; man must renounce itsfruit, for on the day on which he ate of ithe would surely die (S&K 1133).It should be noted at the outset that sin isritual, not rational; and that it is a matterof act, not of thought, intent, or state ofmind (S&K 1134).It was only by the concept of sin thatnatural death became logical to theprimitive mind.Sin was the transgression of taboo, anddeath was the penalty of sin.<strong>89</strong>:2.3 Sin was ritual, not rational; anact, not a thought.And this entire concept of sin wasfostered by the lingering traditions ofDilmun and the days of a little paradiseon earth.The tradition of Adam and the Garden ofEden also lent substance toThe belief is always present, byimplication at least, that there was once asinless time, when all were happy; thiswas the Golden Age.the dream of a onetime “golden age” ofthe dawn of the races.10

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>And all this confirmed the ideas laterexpressed in the belief that man had hisorigin in a special creation,There were once perfect people, likeHomer’s “blameless Ethiopians, some atthe rising sun, some at the setting” (S&K1136).Generally such beliefs in the good oldtimes are accompanied by explanations oftheir disappearance wherein it appearsthat man was responsible, by reason ofhis injudicious and sinful behavior, forthe existence of death and woes of everydescription (S&K 1136).[contd] The drawing of a distinctionbetween sin, crime, and vice may help toclarify all three conceptions. Vice isindividual and is the original and realthing.Religion makes it a sin; law a crime.Among primitive people, since law is solargely a matter of religious taboo, sinand crime are pretty much the same thing(S&K 1136).Calamity to the community is proofpositive of the presence of sin (S&K1138).Men have exercised themselves in allages concerning the relation of goodnessand happiness. Theoretically they oughtto go together; but there were instancesenough where the wicked flourished likethe green bay tree (S&K 1140).that he started his career in perfection,and that transgression of the taboos—sin—brought him down to his later sorryplight.<strong>89</strong>:2.4 The habitual violation of a taboobecame a vice;primitive law made vice a crime; religionmade it a sin.Among the early tribes the violation of ataboo was a combined crime and sin.Community calamity was alwaysregarded as punishment for tribal sin.To those who believed that prosperity andrighteousness went together,the apparent prosperity of the wickedoccasioned so much worry that it wasnecessary to invent hells for thepunishment of taboo violators;11

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Tibetan Buddhism distinguishes sixhells for different classes of sins ... (S&KIV 597).the numbers of these places of futurepunishment have varied from one to five.§275.* Remission. (Sumner & Keller 1140)One of the prime methods of selfclearanceis confession (S&K 1142).A rather forehanded case of remissionis reported from Alaska, where “a notedwoman of Sitka prayed openly in prayermeetingthat God forgive her for the sinsshe had in mind to commit the followingweek” (S&K IV 602).Confession is a sort of exorcism byritual (S&K 1142).Though later ideas demand admission ofsin as the first preliminary to remission,the original object of insisting uponconfession seems to have been the sameas that for requiring a notification of thepresence of disease, like the “Unclean!unclean!” of the leper (S&K 1142).[See S&K 1143-44.][See 88:5.1, 92:1.1.]<strong>89</strong>:2.5 The idea of confession andforgiveness early appeared in primitivereligion.Men would ask forgiveness at a publicmeeting for sins they intended to committhe following week.Confession was merely a rite ofremission,also a public notification of defilement, aritual of crying “unclean, unclean!”Then followed all the ritualistic schemesof purification. All ancient peoplespracticed these meaningless ceremonies.Many apparently hygienic customs of theearly tribes were largely ceremonial.12

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>XXXIII: PROPITIATION (Sumner &Keller 1167)§280.* Renunciation. (Sumner & Keller1179)3. R ENUNCIATION ANDHUMILIATION<strong>89</strong>:3.1 Renunciation came as the nextstep in religious evolution;Fasting was a common practice of theHebrews and Christians, as anyconcordance of the Bible amplydemonstrates (S&K IV 637).Then there is the renunciation of sexrelationsand social ties in general, and atlength the system of asceticism appears(S&K 1180).[See S&K IV 636-37.][See 87:2.10.]The notion that poverty was meritoriousand a good in itself was widelyentertained but unformulated at thebeginning of the thirteenth century; itlater gave rise to the mendicant orders(S&K IV 637).fasting was a common practice.Soon it became the custom to foregomany forms of physical pleasure,especially of a sexual nature.The ritual of the fast was deeply rooted inmany ancient religions and has beenhanded down to practically all moderntheologic systems of thought.<strong>89</strong>:3.2 Just about the time barbarianman was recovering from the wastefulpractice of burning and burying propertywith the dead, just as the economicstructure of the races was beginning totake shape, this new religious doctrine ofrenunciation appeared, and tens ofthousands of earnest souls began to courtpoverty. Property was regarded as aspiritual handicap.These notions of the spiritual dangers ofmaterial possession were widespreadlyentertained in the times of Philo and Paul,13

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>and they have markedly influencedEuropean philosophy ever since.[If [the gods delight in human pain andmisfortune], then one of the ways to propitiatethem is through renunciation, actual or ostensible,of life’s goods and pleasures; and another ispositive self-torture or “mortification of the flesh”(S&K 1179).]<strong>89</strong>:3.3 Poverty was just a part of theritual of the mortification of the fleshwhich, unfortunately, becameincorporated into the writings andteachings of many religions, notablyChristianity.Renunciation is sacrifice, though itmight be termed negative as comparedwith the offering of actual goods.... Thetaboo, coercitives, asceticism, penance,and the “state of grace” are allinterconnected ... (S&K 1180).Penance is the negative form of thisofttimes foolish ritual of renunciation.But all this taught the savage self-control,and that was a worth-while advancementin social evolution. Self-denial andself-control were two of the greatestsocial gains from early evolutionaryreligion.Renunciation really taught a greatlife-policy, though no one was aware ofit.It is the method, in its refined form, ofincreasing life’s fraction by lowering thedenominator of demands instead ofstriving always to increase the numeratorof satisfactions. It comes to be one of thegreat life-philosophies (S&K 1182).Self-control gave man a new philosophyof life;it taught him the art of augmenting life’sfraction by lowering the denominator ofpersonal demands instead of alwaysattempting to increase the numerator ofselfish gratification.14

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>§282.* Self-Discipline. (Sumner & Keller1187)Self-discipline means to the majority ofreaders something like self-torture (S&K1187).“ ... The priest of the Great Motherconsecrated himself to her service with anact of self-sacrifice as great as that of anymodern monk or priest. He knew what itwas to fast, he was merciless to his fleshon the Dies sanguinis, and was nostranger to the pain of self-scourging.”The final act of consecration, by whichone became a minister of the cult, wascastration... (S&K IV 643).[Compare S&K IV 640-41 re Hindus and Jains;contrast 94:7.2 re the attitude of Buddhism towardextreme self-discipline.]Pious works not alone pile up credits forthe individual; a surplus of them is alsoavailable for all in the cult-union,including both the living and the dead(S&K 1194).The foregoing introduces us bluntlyto the idea that the cult-activities inpropitiation are to be regarded as restingupon a sort of ledger account kept bysome supernatural agency (S&K 1194).<strong>89</strong>:3.4 These olden ideas ofself-discipline embraced flogging and allsorts of physical torture.The priests of the mother cult wereespecially active in teaching the virtue ofphysical suffering,setting the example by submittingthemselves to castration.The Hebrews, Hindus, and Buddhistswere earnest devotees of this doctrine ofphysical humiliation.<strong>89</strong>:3.5 All through the olden times mensought in these ways for extra creditson the self-denial ledgers of their gods.§283. Vows. (Sumner & Keller 1195)[See four rows down.]It was once customary, when under someemotional stress, to make vows ofself-denial and self-torture.15

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>[contd] The vow is a sort of contractwith the spirits;In time these vows assumed the form ofcontracts with the godsand, in that sense, represented trueevolutionary progress in that the godswere supposed to[Often something definite was expected in return,as when Ezra proclaimed a fast at the river ofAhava, “that we might afflict ourselves before ourGod, to seek of him a right way for us, and for ourlittle ones, and for all our substance. . . . So wefasted and besought our God for this: and he wasintreated of us” (S&K IV 637).]and it may promise either renunciation orpositive sacrifice (S&K 1195).India is a land of extreme vows, ashas already appeared.... Lippert thinksthese vows of self-torture in India werethe substitute for positive sacrifice ofwhich poverty did not permit (S&K 1195-96).do something definite in return for thisself-torture and mortification of the flesh.Vows were both negative and positive.Pledges of this harmful and extremenature are best observed today amongcertain groups in India.§281.* Continence. (Sumner & Keller 1183)<strong>89</strong>:3.6 It was only natural that the cultof renunciation and humiliation shouldhave paid attention to sexual gratification.When the Maori went to war, “theywere separated from their wives, and didnot again approach them until peace wasproclaimed ...” (S&K 1184). [See S&K 1184for more cases.]The continence cult originated as a ritualamong soldiers prior to engaging inbattle;in later days it became the practice of“saints.”[Nevertheless, to avoid fornication, let everyman have his own wife, and let every woman haveher own husband (1 Cor. 7:2).][Compare S&K 1186.]This cult tolerated marriage only as anevil lesser than fornication.Many of the world’s great religions havebeen adversely influenced by this ancientcult, but none more markedly thanChristianity.16

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>The Apostle Paul was a devotee of thiscult, and his personal views are reflectedin the teachings which he fastened ontoChristian theology:[Now concerning the things whereof ye wroteunto me: It is good for a man not to touch a woman(1 Cor. 7:1).][For I would that all men were even as Imyself. But every man hath his proper gift of God,one after this manner, and another after that.I say therefore to the unmarried and widows,It is good for them if they abide even as I (1 Cor.7:7-8).]“It is good for a man not to touch awoman.”“I would that all men were even as Imyself.”“I say, therefore, to the unmarried andwidows, it is good for them to abide evenas I.”Paul well knew that such teachings werenot a part of Jesus’ gospel, and hisacknowledgment of this is illustrated byhis statement,[But I speak this by permission, and not ofcommandment (1 Cor. 7:6).]“I speak this by permission and not bycommandment.”But this cult led Paul to look down uponwomen. And the pity of it all is that hispersonal opinions have long influencedthe teachings of a great world religion. Ifthe advice of the tentmaker-teacher wereto be literally and universally obeyed,then would the human race come to asudden and inglorious end. Furthermore,the involvement of a religion with theancient continence cult leads directly to awar against marriage and the home,society’s veritable foundation and thebasic institution of human progress.The struggle to maintain a celibatepriesthood was carried on by suchdetermined prelates as Popes Leo IX andGregory VII. [Etc.] (S&K IV 640) [SeeS&K IV 638 for cases of celibate priesthoods inother religions.]And it is not to be wondered at that allsuch beliefs fostered the formation ofcelibate priesthoods in the many religionsof various peoples.17

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>[The erotic and the religious seem often to beclosely allied one to the other. Religion runs outinto sensuality and obscenity beyond description.It is not necessary to go beyond the mention of thismatter: there is unlimited license and debauch; alltaboos, even that proscribing incest, are suspended;the carnal runs out into unimagined variety andinventiveness (S&K 1192-93).] [See also S&K IV642.]<strong>89</strong>:3.7 Someday man should learn howto enjoy liberty without license,nourishment without gluttony, andpleasure without debauchery.Self-control is a better human policy ofbehavior regulation than is extremeself-denial.[See 143:2.] Nor did Jesus ever teach theseunreasonable views to his followers.XI: SACRIFICE (Hopkins 151)4. ORIGINS OF SACRIFICEThere have been various theories as to theorigin of sacrifice but none is satisfactory,because, though all are correct in theirinterpretation of certain phenomena, allare deficient in that they are intended tomake one interpretation cover allphenomena (H 151).Before man had a clear conception ofa spirit inhabiting a body, when he fearsrather the power of the jungle than anydemon in it, when he has no thought of alump of metal being the home of a spiritbut yet entreats it as a living whole, hemakes, in this attitude of mind, first of alla gesture indicating his appreciation ofthe power. If he is accustomed toprostrate himself before his chief, that isthe gesture he employs; if merely to bowthe head or stretch forth the arms, that ishis gesture here (H 151-52).<strong>89</strong>:4.1 Sacrifice as a part of religiousdevotions, like many other worshipfulrituals, did not have a simple and singleorigin.The tendency to bow down before powerand to prostrate oneself in worshipfuladoration in the presence of mystery18

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>It is a reflex in the individual of instinct(as a dog fawns) or social usage asapplied to an extraneous object ofrespect; its intent is to show the man’shumility in the presence of a recognizedpower (H 152).Further, the act which in social relationsis apt to accompany such a gestureaccompanies it here in many instances ofsavage procedure; that is, the savageoffers something to the power, just as heoffers a little something when he bows tohis chief, or greets an awesome strangepower in human shape. This offering is,so to speak, one with the gesture ofprostration (H 152).is foreshadowed in the fawning of the dogbefore its master.It is but one step from the impulse ofworship to the act of sacrifice.Primitive man gauged the value of hissacrifice by the pain which he suffered.When the idea of sacrifice first attacheditself to religious ceremonial, no offeringwas contemplated which was notproductive of pain.[The savage] makes no gift at all; heperforms his act of abnegation because hebelieves that the exercise of restraintstrengthens his own power in which weare forced to think of as a spiritual way;his mana is strengthened, is the way hethinks of the matter; or, one may say, hethinks of it in terms of increased vitality.It is for this reason that teeth are pulledout and hair is plucked deliberately (thisword is important) and other painproducingacts are undergone, tostimulate power (H 157-58).It is not so much the Aeschylean doctrineof ðáèåí ìáèåí (wisdom comes fromsuffering) as it is the Christiansanctification through sorrow which isadumbrated in these savage examples ofabnegation and initiation (H 159).The first sacrifices were such acts asplucking hair, cutting the flesh,mutilations, knocking out teeth, andcutting off fingers.As civilization advanced, these crudeconcepts of sacrifice were elevated to thelevel of the rituals of self-abnegation,asceticism, fasting, deprivation, and thelater Christian doctrine of sanctificationthrough sorrow, suffering, and themortification of the flesh.19

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong><strong>89</strong>:4.2 Early in the evolution of religionthere existed two conceptions of thesacrifice:Under the head of a “gift-sacrifice” issometimes, brought by straining a point,such a “gift” as was made byAgamemnon when he sacrificedIphigeneia. In reality, this was a form ofplacation made under duress to overcomedivine anger, piacular rather than “aspecial form of gift-sacrifice”; at bottomit was the payment of a debt, making upfor an injury.the idea of the gift sacrifice,[Contradicts <strong>89</strong>:8.6, below.] which connoted the attitude ofthanksgiving,According to one view of sacrifice asexplained by the Brahmans, everysacrifice is the paying of a debt, or rather,in giving a sacrifice everyone “buyshimself off,” âtmânam nishkrînîte,redeems himself, pays his debt by proxy(Ait. Brah., 2, 3, 11) (H 165-66).A substitute is always as acceptableas the original victim (H 164 fn.).There is, as already explained, a (notuncommon) form of sacrifice,—forexample, in Borneo,—where oneslaughters a pig or some such animal andby it sends a message or inquiry to theManes or gods; its spirit takes themessage and its liver shows the answer(H 168).[And the LORD smelled a sweet savour; andthe LORD said in his heart, I will not curse theground any more for man’s sake; for theimagination of man’s heart is evil from his youth;neither will I again smite any more every livingthing, as I have done (Gen. 8:21).]and the debt sacrifice, which embracedthe idea of redemption.Later there developed the notion ofsubstitution.<strong>89</strong>:4.3 Man still later conceived that hissacrifice of whatever nature mightfunction as a message bearer to the gods;it might be as a sweet savor in the nostrilsof deity.20

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>XXXV: ANTECEDENTS OF HUMANSACRIFICE (Sumner & Keller 1223)§2<strong>89</strong>. The Food-Interest. (Sumner & Keller1223)This brought incense and other aestheticfeatures of sacrificial rituals whichdeveloped into sacrificial feasting, in timebecoming increasingly elaborate andornate.With the higher development of spiritualconceptions, methods of conciliation andpropitiation worked toward the front,replacing, at least in outward form, thenegative recourse of avoidance andexorcism (S&K 1223).<strong>89</strong>:4.4 As religion evolved, thesacrificial rites of conciliation andpropitiation replaced the older methods ofavoidance, placation, and exorcism.XXXIV: SACRIFICE (Sumner & Keller1199)§286.* Atonement. (Sumner & Keller 1210)[contd] It has been noted that sacrificeoften represents a sort of neutrality-tolllevied by the gods (S&K 1210).<strong>89</strong>:4.5 The earliest idea of the sacrificewas that of a neutrality assessment leviedby ancestral spirits;only later did the idea of atonementdevelop.As man got away from the notion of theevolutionary origin of the race, as thetraditions of the days of the PlanetaryPrince and the sojourn of Adam filtereddown through time,21

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>In fact, there lies behind the aforesaidneutrality-toll the widespread notion thatman is by his actions, wittingly orunwittingly, always in sin—even that hehas come into the world already sinfuland under peril. “Original sin” maybelong, as a dogma, to a more developedstage of civilization, but the convictionthat anyone may at any time sin, and sobe a candidate for punishment, is entirelycorrelative with the common experienceof all mankind ... (S&K 1210).the concept of sin and of original sinbecame widespread,so that sacrifice for accidental andpersonal sin evolved into the doctrine ofsacrifice for the atonement of racial sin.An “unknown god” might, at any time,resent lack of propitiation. The only safecourse, under these circumstances, was toatone regularly and punctiliously for whatsins one must have committed or must becommitting that he could not know about.It was a sort of blanket insurance-device,covering visitations of the aleatoryelement not otherwise provided against(S&K 1211-12).The atonement of the sacrifice was ablanket insurance device which coveredeven the resentment and jealousy of anunknown god.<strong>89</strong>:4.6 Surrounded by so manysensitive spirits and grasping gods,There are so many creditors amongthe deities that it seems to be more than alife’s work for a man to get out of debt(S&K IV 649).primitive man was face to face with sucha host of creditor deities that it requiredall the priests, ritual, and sacrificesthroughout an entire lifetime to get himout of spiritual debt.The doctrine of original sin, or racialguilt, started every person out in seriousdebt to the spirit powers.22

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>§284.* Nature of Sacrifice. (Sumner & Keller1199)[contd] A gift or a bribe may be“given” to a human being; when it ispresented to a daimon, however, theproper term is to “dedicate” or “makesacred” or “sacrifice.”From renunciatory forms of propitiationthe series now passes to the positivegiving or sacrifice of property, and evenof life itself, in order to avoid misfortuneor to secure good luck (S&K 1199).Positive methods of propitiation include,in addition, whatever else would pleaseand predispose human beings, such aspraise, glorification, flattery, andentertainment in general (S&K 1199).<strong>89</strong>:4.7 Gifts and bribes are given tomen; but when tendered to the gods, theyare described as being dedicated, madesacred, or are called sacrifices.Renunciation was the negative form ofpropitiation; sacrifice became the positiveform.The act of propitiation included praise,glorification, flattery, and evenentertainment.And it is the remnants of these positivepractices of the olden propitiation cultthat constitute the modern forms of divineworship.The whole medley of forms taken bysacrifice and worship becomes ritualizedjust as do the negative forms of the cult;and—what is more significant—theelements of reverence, awe, dread,devotion, and adoration inherent in theformer are merely extensions andrefinements of original ghost-fear (S&K1199).Present-day forms of worship are simplythe ritualization of these ancientsacrificial techniques of positivepropitiation.<strong>89</strong>:4.8 Animal sacrifice meant muchmore to primitive man than it could evermean to modern races.23

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>[Robertson Smith, in his Religion of theSemites,] makes much of the reverenceand trust felt toward the gods on accountof the common consanguineal bondsexisting between them and theirworshippers. Even the victim, an animal,was within the sacred circle of kin; andthe sacrificial meal was therefore a sort ofcommunion between blood-kin (S&K1200).These barbarians regarded the animals astheir actual and near kin.§288. The Burden of Sacrifice. (Sumner &Keller 1219)As time passed, man became shrewd inhis sacrificing,The fact that the work-animal is notsacrificed is significant (S&K 1220).The Indians depleted their stock in similarmanner [as the Koryak]; “and in makingthese sacrifices, and all gifts to the GreatSpirit, there is one thing yet to betold—that, whatever gift is made, whethera horse, a dog, or other article, it is sure tobe the best of its kind that the giverpossesses, otherwise he subjects himselfto disgrace in his tribe, and to the ill willof the power he is endeavoring toconciliate...” (S&K 1220).Erman thinks the boastful records ofa Rameses III worthy of credence. In areign of thirty-three years, he had given tothe various temples113,433 slaves, 493,386 head of cattle, 88barks and galleys, and 2,756 goldenimages.Further contributions were 331,702 jarsof incense, honey, and oil; 228,380 jars ofwine and drink; 680,714 geese; 6,744,428loaves of bread; and 5,740,352 sacks ofcoin.ceasing to offer up his work animals.At first he sacrificed the best ofeverything, including his domesticatedanimals.<strong>89</strong>:4.9 It was no empty boast that acertain Egyptian ruler made when hestated that he had sacrificed:113,433 slaves, 493,386 head of cattle, 88boats, 2,756 golden images,331,702 jars of honey and oil, 228,380jars of wine, 680,714 geese, 6,744,428loaves of bread, and 5,740,352 sacks ofcoin.24

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>To get this wealth the king taxed hissubjects; he did not create it himself. Theburden rested squarely and heavily uponthe population (S&K 1221).[All people, savages and civilized, have opined thatspirits live on spirit-food, not the gross flesh butthe soul of the flesh, and have made the materialpart their own share while leaving the essence orsome part not desirable as human food for the gods(Hopkins 172).]The fact that the victim was devouredin good part by the sacrificers, while thegod was there to eat his part, makes of thesacrifice a sort of communion-meal, witha large significance of its own (S&K1222).And in order to do this he must needshave sorely taxed his toiling subjects.<strong>89</strong>:4.10 Sheer necessity eventuallydrove these semisavages to eat thematerial part of their sacrifices, the godshaving enjoyed the soul thereof.And this custom found justification underthe pretense of the ancient sacred meal, acommunion service according to modernusage.5 . S A C R I F I C E S A N DCANNIBALISMXXXV: ANTECEDENTS OF HUMANSACRIFICE (Sumner & Keller 1223)§293. Survivals and Legends. (Sumner &Keller 1243)Civilized men might think thatcannibalism was a usage of low savagery,far removed from our interest and servingonly to show how low human beings cansink. Evidently that is a grossmisconception of it. It was a leadingfeature of society at a certain stage,around which a great cluster of morescentered ... (S&K 1249).Our horror of cannibalism is due to along tradition, broken only by hearsay ofsome far distant and extremely savagepeople who practise it; therefore we thinkit, in itself, and “naturally,” revolting toeverybody and possible only to degradedraces (S&K 1249).<strong>89</strong>:5.1 Modern ideas of earlycannibalism are entirely wrong; it was apart of the mores of early society.While cannibalism is traditionallyhorrible to modern civilization,25

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>it was a part of the social and religiousstructure of primitive society.Where everybody believed thatcannibalism was the only expedientpossible under certain circumstances,beneficent alike for the eater and theeaten, or necessary for the preservation ofthe strength of the former alone, groupinterestcalled for the practice (S&K1250).Group interests dictated the practice ofcannibalism.It grew up through the urge of necessityand persisted because of the slavery ofsuperstition and ignorance. It was asocial, economic, religious, and militarycustom.§2<strong>89</strong>. The Food-Interest. (Sumner & Keller1223)[See S&K 1224.]Men dealt with the daimons as withhuman beings raised to a higher power ...(S&K 1223).Of all gifts to the spirits a largefraction have consisted of food; it was thevital interest, the thing most generally andsteadily in demand. The first need, forspirit as for man, was to be nourished, asany unselected collection of instances, nomatter how exhaustive, reveals (S&K1223).<strong>89</strong>:5.2 Early man was a cannibal; heenjoyed human flesh, and therefore heoffered it as a food gift to the spirits andhis primitive gods.Since ghost spirits were merely modifiedmen,and since food was man’s greatest need,then food must likewise be a spirit’sgreatest need.§290.* Cannibalism. (Sumner & Keller 1225)[contd] If it were not for the longstandingtaboo against the eating ofhuman flesh, the contention thatcannibalism was widespread and perhapsuniversal amongst mankind would rouselittle opposition (S&K 1225).<strong>89</strong>:5.3 Cannibalism was once well-nighuniversal among the evolving races.26

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Animal-ways present no series, nosignificant and steady tendency, whichwould force us to any conclusion as to theoriginal state of man.... All that we couldconclude from the facts about animals isthat some men were cannibals and somewere not, which we know already (S&K1226).The Sangiks were all cannibalistic, butoriginally the Andonites were not,nor were the Nodites and Adamites;neither were the Andites until after theyhad become grossly admixed with theevolutionary races.§291. Corporeal Cannibalism. (Sumner &Keller 1230)In the year 1200 A.D. the Nile failed andfamine ensued. Children were eaten bytheir parents. The civil authorities burnedsuch cannibals alive and all wasastonishment and horror over thisoutbreak of savagery. But the people gotused to the practice and acquired a tastefor human flesh (S&K 1235).<strong>89</strong>:5.4 The taste for human flesh grows.Having been started through hunger,friendship, revenge, or religious ritual, theeating of human flesh goes on to habitualcannibalism.The explanation of cannibalism asdue to lack of meat-food, or of food ingeneral, though supported by some littleevidence, is controverted by the greatpreponderance of cases (S&K 1230).Man-eating has arisen through foodscarcity,though this has seldom been theunderlying reason.27

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Instances of cannibalism due to utterdestitution, as where the Eskimo arecannibals only in times of famine, are notmarvellous or even significant; stories ofshipwrecks in relatively recent timesshow the breakdown of any food-taboounder stress (S&K 1231).[Compare S&K 1227 and S&K IV 662-63.]The Eskimos and early Andonites,however, seldom were cannibalisticexcept in times of famine.The red men, especially in CentralAmerica, were cannibals.§292.* Animistic Cannibalism. (Sumner &Keller 1235)In Queensland women kill and eattheir children in order to recover theirstrength (S&K 1238).“Children are eaten when they die, but thecrime of infanticide is not very common,unless in the case of a first child” (S&K1238).Thus cannibalism was a sort of warmeasureand a means of infusing terror(S&K 1241). [See also S&K 1240.]Cannibalism might then be retained by anindividual or group as a measure of“frightfulness”; cases of modern“outbreaks of savagery” are familiar(S&K 1241).It was once a general practice forprimitive mothers to kill and eat their ownchildren in order to renew the strengthlost in childbearing,and in Queensland the first child is stillfrequently thus killed and devoured.In recent times cannibalism has beendeliberately resorted to by many Africantribes as a war measure,a sort of frightfulness with which toterrorize their neighbors.§290.* Cannibalism. (Sumner & Keller 1225)Further, we are not disturbed in our use ofethnography by the objection, on the partof those who revolt at facing truthsunpalatable to their taste, that all cases ofcannibalism represent mere degeneration.Some of them do; but there is nothingbehind the general challenge toethnographic evidence except sentimentality(S&K 1226).<strong>89</strong>:5.5 Some cannibalism resulted fromthe degeneration of once superior stocks,28

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>but it was mostly prevalent among theevolutionary races.In the northern New Hebrides, “after abitter fight they would take a slain enemyand eat him, as a sign of rage andindignation; they would cook him in anoven, and each would eat a bit of him,women and children too. When there wasa less bitter feeling, the flesh of a deadenemy was taken away by the conquerorsto be cooked and given to their friends”(S&K 1228).Man-eating came on at a time when menexperienced intense and bitter emotionsregarding their enemies.§292.* Animalistic Cannibalism (Sumner &Keller 1235)“The most acceptable explanation is thatmen, driven by a far-reaching desire forrevenge, ate the war-prisoners or theslain, to the end of annihilating themutterly and in the most shameful manner”(S&K 1240).Eating human flesh became part of asolemn ceremony of revenge; it wasbelieved that an enemy’s ghost could, inthis way, be destroyedor fused with that of the eater.Sorcerers [in Central Australia] allegethat they must eat human flesh to keep uptheir supernatural powers (S&K IV 664).It is to be noted in passing that manycannibals will devour only their fellowtribesmen;there is a so-called “endocannibalism,”by which is preserved inthe tribe the whole body of soul-strengthbelonging to it. In such case the eating ofthe deceased is an honor to them.Here is a sort of exclusive spiritual inbreeding,of interest chiefly in itsaccentuation of familial and tribalsolidarity (S&K 1237).It was once a widespread belief thatwizards attained their powers by eatinghuman flesh.<strong>89</strong>:5.6 Certain groups of man-eaterswould consume only members of theirown tribes,a pseudospiritual inbreeding which wassupposed to accentuate tribal solidarity.29

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>A common practice also is to eat the bodyof an enemy, with a view to theappropriation of his valor and strength,just as the heart of the lion is devoured toincrease one’s own heart-quality or“courage.”But they also ate enemies for revengewith the idea of appropriating theirstrength.It was considered an honor to the soul ofa friend or fellow tribesman if his bodywere eaten,Other seats of the soul are singled out forappropriation and there appears, further,the notion that some extra punishment isthus inflicted upon the dead foe; that hissoul is destroyed or damaged in someway (S&K 1237).while it was no more than justpunishment to an enemy thus to devourhim.The savage mind made no pretensions tobeing consistent.Funeral-cannibalism is also reported ofthe Birhors of Hindustan, who formerlyused to kill and eat their aged parents ...Reclus, without citing authority, says thatin this tribe “the parents beg that theircorpses may find a refuge in the stomachsof their children, rather than be left on theroad or in the forest” (S&K IV 667).<strong>89</strong>:5.7 Among some tribes aged parentswould seek to be eaten by their children;§290.* Cannibalism. (Sumner & Keller 1225)The Fang and other interior tribes eat anycorpse, regardless of the cause of death.Families hesitate to eat their own dead,but they sell or exchange them for thedead of other families” (S&K IV 660).among others it was customary to refrainfrom eating near relations; their bodieswere sold or exchanged for those ofstrangers.§291. Corporeal Cannibalism. (Sumner &Keller 1230)In one district of the Solomon Islandsvictims, mostly women, were purchasedin an neighboring island, fattened for thefeast, and “killed and eaten as pigs wouldhave been” (S&K 1233).There was considerable commerce inwomen and children who had beenfattened for slaughter.30

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>Sometimes cannibalism seems even to bea sort of groping population-policy, “tokeep the tribe from increasing beyond thecarrying capacity of the territory” (S&K1235).When disease or war failed to controlpopulation, the surplus was unceremoniouslyeaten.§293. Survivals and Legends. (Sumner &Keller 1243)As accounting for the decline ofcannibalism, a line of thought whichseems to cover a maximum of the factsand to incur a minimum of the objectionsis as follows (S&K 1247).<strong>89</strong>:5.8 Cannibalism has been graduallydisappearing because of the followinginfluences:§292.* Animistic Cannibalism. (Sumner &Keller 1235)Perhaps also there may be in thecommunal eating of the criminal the ideaof collective responsibility for putting todeath a tribal comrade.The blood-guilt, if any, must be incurredby all. The ritual of execution is like thatof sacrifice; it ceases to be a crime onlywhen done by all (S&K 1241).The Chinese, according to MarcoPolo, formerly ate all who were executedby authority (S&K 1242).If the phenomena of cannibalism areviewed as a whole, it is clear that maneatingis a matter of ceremonial and ritualrather than of mere alimentation (S&K1236).<strong>89</strong>:5.9 1. It sometimes became acommunal ceremony, the assumption ofcollective responsibility for inflicting thedeath penalty upon a fellow tribesman.The blood guilt ceases to be a crime whenparticipated in by all, by society.The last of cannibalism in Asia was thiseating of executed criminals.<strong>89</strong>:5.10 2. It very early became areligious ritual,but the growth of ghost fear did notalways operate to reduce man-eating.It is not the whole body that is eaten; it isthe few and selected parts, thosesupposed to contain the vital principle(S&K 1236).<strong>89</strong>:5.11 3. Eventually it progressed tothe point where only certain parts ororgans of the body were eaten, those partssupposed to contain the soul or portionsof the spirit.31

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>There seems to have been an idea amongprimitive races that by eating the flesh orsome portion of the body recognized asthe seat of power, or by drinking theblood of a human being, the person sodoing absorbs the nature or life of the onesacrificed (S&K 1237).Blood drinking became common,§293. Survivals and Legends. (Sumner &Keller 1243)[Compare first row of <strong>89</strong>:5.15 re “the concoction ofvarious medicines from parts of the human body”.]Cannibalism becomes narrowed downin practice, becoming a prerogative onlyof men,of chiefs, of shamans, and it takes on thequality of the antique and traditional, theholy, solemn, ritual, and judicial (S&K1243).and it was customary to mix the “edible”parts of the body with medicines.<strong>89</strong>:5.12 4. It became limited to men;women were forbidden to eat humanflesh.<strong>89</strong>:5.13 5. It was next limited to thechiefs, priests, and shamans.<strong>89</strong>:5.14 6. Then it became taboo amongthe higher tribes. The taboo onman-eating originated in Dalamatia andslowly spread over the world.[The Tauaré burn their dead. The ashes arepreserved in holly reeds and at each meal some ofthem are consumed (S&K IV 668).]Where the English government set out tostop [human sacrifices among the Bella-Coola Indians], the priests dug up corpsesand ate them, several being thus poisoned(S&K 1238).The Nodites encouraged cremation as ameans of combating cannibalismsince it was once a common practice todig up buried bodies and eat them.Human sacrifice sounded the death knellof cannibalism.If then, human flesh is tabooed infavor of superiors, it is in the naturalorder that it shall come to be set apart forthe daimons.Human flesh having become the food ofsuperior men, the chiefs, it was eventuallyreserved for the still more superior spirits;32

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>and thus the offering of human sacrificeseffectively put a stop to cannibalism,except among the lowest tribes.When human sacrifice was fullyestablished, man-eating became taboo;Such is the case, for it comes to be a holyfood, reserved for them; it is “unclean,”as holy things are wont to be,and man may not eat of it except onspecial religious occasions (S&K 1247-48).[Cannibalism] passes into practices thatrecall it more or less distinctly, such asthe concoction of various medicines fromparts of the human body and the animalsubstitutionsconnected with humansacrifice, which is itself the chief survivalof cannibalism (S&K 1243).There is a theory, interesting ratherthan demonstrable, according to whichdog-eating is to be regarded as a survivalof cannibalism (S&K 1244).The dog was undoubtedly the earliest andmost widespread domestic animal and so,very likely, the first to act as a substitutefor a human victim, as he is now asubstitute in the New Hebrides ... (S&K1244).human flesh was food only for the gods;man could eat only a small ceremonialbit, a sacrament.<strong>89</strong>:5.15 Finally animal substitutes cameinto general use for sacrificial purposes,and even among the more backward tribesdog-eating greatly reduced man-eating.The dog was the first domesticatedanimaland was held in high esteem both as suchand as food.33

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>XXXVI: HUMAN SACRIFICE (Sumner& Keller 1251)§294.* Nature of the Offering. (Sumner &Keller 1251)6. EVOLUTION OF HUMANSACRIFICE<strong>89</strong>:6.1 Human sacrifice was an indirectresult of cannibalism as well as its cure.There has already come before us a typeof human sacrifice that is neither directlynor indirectly connected with man-eating:the provision of an escort for the dead tothe spirit-world (S&K 1251).Providing spirit escorts to the spirit worldalso led to the lessening of man-eating asit was never the custom to eat these deathsacrifices.It is astonishing to one who holds thecurrent notions about human sacrifice toread that “there is not a people that hasnot practised this custom at some periodor other of its history.No race has been entirely free from thepractice of human sacrifice in some formand at some time,even though the Andonites, Nodites, andAdamites were the least addicted tocannibalism.<strong>89</strong>:6.2 Human sacrifice has beenvirtually universal;Hindus, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, evenIsraelites, differ, in this matter, from thenegroes of our own times in nothing savethe object they assign to this kind ofsacrifice. The longer the matter is studied,the less is one inclined to balk at thisuniversal” (S&K 1251).it persisted in the religious customs of theChinese, Hindus, Egyptians, Hebrews,Mesopotamians, Greeks, Romans, andmany other peoples, even on to recenttimes among the backward African andAustralian tribes.34

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>An author from whom we havequoted in the text goes into detail thatreveals the connection [among the Aztecsand the Maya in Mexico, and inNicaragua] of such sacrifices withcannibalism (S&K IV 674).In Chaldæa of the most ancientperiods there were human sacrifices; butlater they became rare and animals wereused instead (S&K IV 675).The later American Indians had acivilization emerging from cannibalismand, therefore, steeped in humansacrifice, especially in Central and SouthAmerica.The Chaldeans were among the first toabandon the sacrificing of humans forordinary occasions, substituting thereforanimals.§297.* Survivals of Human Sacrifice.(Sumner & Keller 1273)In Japan, “human sacrifice appears tohave been practiced, and, if we may judgeby the numerous legends handed down,was not entirely suppressed until longafter the period when clay images wereproduced as a substitute.” Legendascribes the substitute images to about thebeginning of the Christian era. Humansacrifice is said to have been abolishedthrough the compassion of the Emperor,when he heard the weeping and crying ofvictims who had been buried alive (S&K1276).About two thousand years ago atenderhearted Japanese emperorintroduced clay images to take the placeof human sacrifices,§294.* Nature of the Offering. (Sumner &Keller 1251)About 900 A.D., the Norsemen were in theOrkneys, and their leader, catching adefeated enemy “made them carve aneagle on his back with a sword and cutthe ribs all from the back-bone and drawthe lungs out, and gave him to Odin forthe victory he had won” (S&K 1256).but it was less than a thousand years agothat these sacrifices died out in northernEurope.35

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>§295.* Redemption and Covenant. (Sumner& Keller 1263)Where a person volunteers to serve assacrifice, we have what might be calledreligious suicide. Such is the case amongsome primitive tribes in China where avoluntary human sacrifice is offered, insome cases annually, so as to preserve thegroup from disease, hunger, and distress(S&K IV 680).Among certain backward tribes, humansacrifice is still carried on by volunteers,a sort of religious or ritual suicide.§294.* Nature of the Offering. (Sumner &Keller 1251)The Chukchi are devoted toshamanism. In 1814, on the appearance ofa contagion affecting men and reindeer,the shamans called for a human sacrificeas the only recourse, naming one of themost respected and beloved elderly menof the tribe.The people would not kill him but, as thedisease did not abate, the old mandevoted himself for his people. Nobodywould execute him until finally his ownson, at his command, put the knife intohis breast (S&K 1254).A shaman once ordered the sacrifice of amuch respected old man of a certain tribe.The people revolted; they refused toobey. Whereupon the old man had hisown son dispatch him;the ancients really believed in thiscustom.<strong>89</strong>:6.3 There is no more tragic andpathetic experience on record, illustrativeof the heart-tearing contentions betweenancient and time-honored religiouscustoms and the contrary demands ofadvancing civilization, than[The cases of the intended sacrifice of Isaacand that of Jephtha’s daughter will occur to thereader of the Old Testament; and the fact that childsacrificeis forbidden witnesses to its existence(S&K 1255).]the Hebrew narrative of Jephthah and hisonly daughter.As was common custom,36

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>[And Jephthah vowed a vow unto the LORD,and said, If thou shalt without fail deliver thechildren of Ammon into mine hands,Then it shall be, that whatsoever cometh forthof the doors of my house to meet me, when I returnin peace from the children of Ammon, shall surelybe the LORD’s, and I will offer it up for a burntoffering (Judg. 11:30-31).]this well-meaning man had made afoolish vow, had bargained with the “godof battles,” agreeing to pay a certain pricefor victory over his enemies. And thisprice was to make a sacrifice of thatwhich first came out of his house to meethim when he returned to his home.Jephthah thought that one of his trustyslaves would thus be on hand to greethim,[And Jephthah came to Mizpeh unto hishouse, and, behold, his daughter came out to meethim with timbrels and with dances: and she was hisonly child; beside her he had neither son nordaughter (Judg. 11:34).]but it turned out that his daughter andonly child came out to welcome himhome.And so, even at that late date and amonga supposedly civilized people,[And she said unto her father, Let this thing bedone for me: let me alone two months, that I maygo up and down upon the mountains, and bewailmy virginity, I and my fellows.And he said, Go. And he sent her away fortwo months: and she went with her companions,and bewailed her virginity upon the mountains.And it came to pass at the end of two months,that she returned unto her father, who did with heraccording to his vow which he had vowed: and sheknew no man (Judg. 11:37-38).]this beautiful maiden, after two months tomourn her fate,was actually offered as a human sacrificeby her father,and with the approval of his fellowtribesmen.And all this was done in the face ofMoses’ stringent rulings against theoffering of human sacrifice.But men and women are addicted tomaking foolish and needless vows, andthe men of old held all such pledges to behighly sacred.37

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>A special variety of human sacrifice,represented incidentally in foregoingexamples, is one which occurs inconnection with the beginning of someimportant undertaking. As it is oftenfound attendant upon the laying of afoundation, it has been called“foundation-sacrifice.”The original purpose was to secure aghost to watch over, to defend, or to givenotice of any peril to some valuedstructure (S&K 1256-57).It is reported that the Chinese used tothrow a young girl into melted bell-metal,to better the tone of the bell (S&K 1257).<strong>89</strong>:6.4 In olden times, when a newbuilding of any importance was started, itwas customary to slay a human being as a“foundation sacrifice.”This provided a ghost spirit to watch overand protect the structure.When the Chinese made ready to cast abell, custom decreed the sacrifice of atleast one maiden for the purpose ofimproving the tone of the bell; the girlchosen was thrown alive into the moltenmetal.<strong>89</strong>:6.5 It was long the practice of manygroups to build slaves alive into importantwalls.The Southern Slavs wall in theshadow of a passer-by; and the immuringof a girl or woman in the foundation of anew house is referred to in Bosnian andHerzogovinian songs (S&K 1259).The Chinese and Tatars, in building acity-wall, interred within it the bodies ofworkmen who died (S&K 1257).[In his days did Hiel the Bethelite buildJericho:he laid the foundation thereof in Abiram hisfirstborn, and set up the gates thereof in hisyoungest son Segub,In later times the northern Europeantribes substituted the walling in of theshadow of a passerby for this custom ofentombing living persons in the walls ofnew buildings.The Chinese buried in a wall thoseworkmen who died while constructing it.<strong>89</strong>:6.6 A petty king in Palestine, inbuilding the walls of Jericho,“laid the foundation thereof in Abiram,his first-born, and set up the gates thereofin his youngest son, Segub.”At that late date, not only did this fatherput two of his sons alive in the foundationholes of the city’s gates, but his action isalso recorded as being38

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>according to the word of the LORD, which he spakeby Joshua the son of Nun (1 Kings 16:34).] [Seealso S&K 1258.]“according to the word of the Lord.”Moses had forbidden these foundationsacrifices, but the Israelites reverted tothem soon after his death.Faint survivals of foundation-sacrificesappear in the dedication of a modernstructure, where the articles deposited inthe hollow of the foundation-stone are farfrom including anything as impressive asan immured victim (S&K 1257).The twentieth-century ceremony ofdepositing trinkets and keepsakes in thecornerstone of a new building isreminiscent of the primitive foundationsacrifices.§295.* Redemption and Covenant. (Sumner& Keller 1263)Offerings of the first-fruits are made totheir forefathers by almost every clan [ofthe Kuki-Lushai] (S&K IV 680). [See alsoS&K 1264.]Here are conceptions, commonlydismissed as symbolic, which aresurvivalistic and capable of explanationonly in the light of the evolution ofreligion. Ransom and redemption go backto the body of primitive ideas andpractices which we have been reviewing,and especially and most directly to humansacrifice as a means of reconciliation andpropitiation ... (S&K 1265).One’s child, especially his first-born, wasthe most obvious life to give for his own;then a slave or a prisoner (S&K 1266).In the case of the Phœnicians childsacrificedeveloped, on such lines oflogic, into an important societalinstitution. The Romans could not stampit out (S&K 1266).<strong>89</strong>:6.7 It was long the custom of manypeoples to dedicate the first fruits to thespirits.And these observances, now more or lesssymbolic, are all survivals of the earlyceremonies involving human sacrifice.The idea of offering the first-born as asacrifice was widespread among theancients,especially among the Phoenicians, whowere the last to give it up.39

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>An Englishman in India is figured ashaving had a son by a native woman, andas, at the instance of an old gate-keeper,performing the ceremony sacrifice bybeheading two goats. While so doing hematters the prayer: “Almighty! In place ofthis my son I offer life for life, blood forblood, head for head, bone for bone, hairfor hair, skin for skin” (S&K 1265).It used to be said upon sacrificing, “lifefor life.”Now you say at death, “dust to dust.”In the story of Abraham, his willingnessto comply with the divine command forthe sacrifice of his son is construed as amerit to be richly rewarded (S&K 1268).In distress it is asked what God demands:“Shall I give my first-born for my sin; thefruit of my body for my transgression?”The first-born is to be given, like the firstfruits(S&K 1268).The following Hindu legend recalls thestory of Abraham. [Etc.] (S&K IV 680)<strong>89</strong>:6.8 The spectacle of Abrahamconstrained to sacrifice his son Isaac,while shocking to civilized susceptibilities,was not a new or strange idea tothe men of those days.It was long a prevalent practice forfathers, at times of great emotional stress,to sacrifice their first-born sons.Many peoples have a tradition analogousto this story,for there once existed a world-wide andprofound belief that it was necessary tooffer a human sacrifice when anythingextraordinary or unusual happened.7. M O D IF IC A T IO N S O FHUMAN SACRIFICE“Even the first-born child, in thesame fashion as the animals, had at firstbeen sacrificed to a bloody Jehovah.Later on it was still in theory dedicated tothe Lord but its ransom was compulsory.Five shekels of silver paid to the Levitesredeemed it.” Each grown man was to paya half-shekel as “a ransom for his soul tothe Lord” (S&K 1268).<strong>89</strong>:7.1 Moses attempted to end humansacrifices by inaugurating the ransom asa substitute.40

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>[See Leviticus 27:1-34.]He established a systematic schedulewhich enabled his people to escape theworst results of their rash and foolishvows. Lands, properties, and childrencould be redeemed according to theestablished fees, which were payable tothe priests.Those groups which ceased to sacrificetheir first-born soon possessed greatadvantages over less advanced neighborswho continued these atrocious acts. Manysuch backward tribes were not onlygreatly weakened by this loss of sons, buteven the succession of leadership wasoften broken.<strong>89</strong>:7.2 An outgrowth of the passingchild sacrifice was the custom ofAt the festal time comes the angel ofJahweh and kills the first-born of theEgyptians. The Israelites, however, hadprotected themselves by sacrificing alamb and sprinkling their door-posts withblood (S&K 1269).Among the Mexicans the divineprimordial mother, Centeotl, at herfestivals, goes about through the land andabodes of men. To protect life, theypierced their ears, noses, tongues, arms,thighs, collected the blood and hung it inancient vessels on the door-posts of thehouses (S&K 1269).smearing blood on the house doorpostsfor the protection of the first-born. Thiswas often done in connection with one ofthe sacred feasts of the year,and this ceremony once obtained overmost of the world from Mexico to Egypt.§294.* Nature of the Offering. (Sumner &Keller 1251)<strong>89</strong>:7.3 Even after most groups hadceased the ritual killing of children, it wasthe custom to put an infant away by itself,off in the wilderness or in a little boat onthe water.41

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>“The exposed and later famous men, likeSargon, Cyrus, Moses, Romulus andRemus, play a great rôle.... Withoutsacrificing the child, it is offered to thegod who expresses his satisfaction bypreserving the child...” (S&K 1262).Another modified form of humansacrifice is the Roman ver sacrum, or“sacred springtime.” Though all the firstbornof a year were vowed to Mars, thatis, to death, they might save their lives, ifthey could, outside the tribe (S&K 1262).“According to the account of Festus,accepted by modern scholars, the versacrum took the following shape: In timesof severe distress the Governmentdedicated to the gods, for the purpose ofmoving them to compassion for thepeople, the entire offspring of both manand beast during the forth-coming year.The children were allowed to live untilthey had grown up; then the marriageableyouth of both sexes had to leave the townand seek their fortunes abroad, and makea new home for themselves elsewhere...”(S&K 1262).[contd from two rows up] This amounted tomass-exposure and led to colonization(S&K 1262).If the child survived, it was thought thatthe gods had intervened to preserve him,as in the traditions of Sargon, Moses,Cyrus, and Romulus.Then came the practice of dedicating thefirst-born sons as sacred or sacrificial,allowing them to grow up and thenexiling them in lieu of death;this was the origin of colonization.The Romans adhered to this custom intheir scheme of colonization.§296*. Sacral or Sacrificial “Prostitution.”(Sumner & Keller 1272)[contd] This practice, termed alsotemple-harlotry, has its relation to humansacrifice, obligation, and ransom (S&K1272).<strong>89</strong>:7.4 Many of the peculiarassociations of sex laxity with primitiveworship had their origin in connectionwith human sacrifice.42

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>The underlying idea is not unlike whatwas in the minds of the people concernedwhen a woman who met a party of headhunterswas allowed to surrender herselfsexually to save her life.A girl might be dedicated, in such arelation, to the god instead of being slainin sacrifice; then she might be bought offwith the earnings of her sojourn in thetemple (S&K 1272).In olden times, if a woman methead-hunters, she could redeem her lifeby sexual surrender.Later, a maiden consecrated to the godsas a sacrifice might elect to redeem herlife by dedicating her body for life to thesacred sex service of the temple; in thisway she could earn her redemptionmoney.The ancients regarded it as highlyelevating to have sex relations with awoman thus engaged in ransoming herlife. It was a religious ceremony toconsort with these sacred maidens, and inaddition, this whole ritual afforded anacceptable excuse for commonplacesexual gratification. This was a subtlespecies of self-deception which both themaidens and their consorts delighted topractice upon themselves.“But not seldom religious traditionrefused to move forward with theprogress of society;the goddess [Aphrodite at Byblos]retained her old character as a motherwho was not a wife bound to fidelity toher husband, and at her sanctuary sheprotected under the name of religion, thesexual license of savage society ...” (S&KIV 685-86).Sacral prostitution was known inEgypt and Assyria, and to the ancientSemites; it spread westward with theBabylonian and Phœnician religions and“flourished in Israel down into the laterera of kings” (S&K 1273).The mores always drag behind in theevolutionary advance of civilization,thus providing sanction for the earlier andmore savagelike sex practices of theevolving races.<strong>89</strong>:7.5 Temple harlotry eventuallyspread throughout southern Europe andAsia.43

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>The money earned by the templeprostitutes was held sacred among allpeoples—“No more welcome gift could a[Phœnician] woman bring to the deitythan the payment she received forsurrendering her body...” (S&K IV 685).[The women dedicated to the service ofthe temples in India] were once generallypatterns of piety and propriety but are notso now.“No doubt they drive a profitable tradeunder the sanction of religion, and somecourtesans have been known to amassenormous fortunes. Nor do they think itinconsistent with their method of makingmoney to spend it in works of piety. Hereand there Indian bridges and other usefulpublic works owe their existence to theliberality of the frail sisterhood” (S&K IV684).The cases given by Herodotus and Strabo... are mere variants of the above; oftenthe dowry for marriage was thuscollected, and there was no dishonorinvolved. Said Strabo: “The Armenianspay particular reverence to Anaïtis, andhave built temples to her honour inseveral places, especially in Acilisene.They dedicate there to her service maleand female slaves; in this there is nothingremarkable, but it is surprising thatpersons of the highest rank in the nationconsecrate their virgin daughters to thegoddess...” (S&K IV 686).Among the Dyaks of Borneo there is aclass of priestesses whose loose mode oflife does not make marriage impossiblefor them but rather the contrary (S&K1272).a high gift to present to the gods.The highest types of women thronged thetemple sex martsand devoted their earnings to all kinds ofsacred services and works of public good.Many of the better classes of womencollected their dowries by temporary sexservice in the temples,and most men preferred to have suchwomen for wives.44

SOURCE OR PARALLEL URANTIA PAPER <strong>89</strong>8 . R E D E M P T I O N A N DCOVENANTS§297.* Survivals of Human Sacrifice.(Sumner & Keller 1273)[contd] Perhaps redemption and sacralprostitution might be called modificationsor mitigations rather than survivals of thesacrifice of human beings; and the samemight be thought of several usages aboutto be mentioned (S&K 1273-74).In Uganda, at the cessation of a dance, alittle girl “was laid out at the base of thetree as though she was to be sacrificed,and every detail of the sacrifice was gonethrough in mock fashion.A slight incision was made in the child’sneck, but not such as to seriously hurther.... The girl on whom this ceremonywas performed, was, my informant learnt,dedicated by native custom to a life ofperpetual virginity” (S&K 1274).<strong>89</strong>:8.1 Sacrificial redemption andtemple prostitution were in realitymodifications of human sacrifice.Next came the mock sacrifice ofdaughters.This ceremony consisted in bloodletting,with dedication to lifelong virginity,and was a moral reaction to the oldertemple harlotry.[See S&K 1187 and 85:4.4.]In more recent times virgins dedicatedthemselves to the service of tending thesacred temple fires.§298.* Exuvial Sacrifice. (Sumner & Keller1278)[T]hat which has been taken to be mostdirectly and indisputably survivalistic ofhuman sacrifice is the actual offering ofparts of the body (S&K 1278).Mutilations are another form of theexuvial sacrifice (S&K 1283).<strong>89</strong>:8.2 Men eventually conceived theidea that the offering of some part of thebody could take the place of the older andcomplete human sacrifice.Physical mutilation was also consideredto be an acceptable substitute.45