here - UCSF Alumni

here - UCSF Alumni

here - UCSF Alumni

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

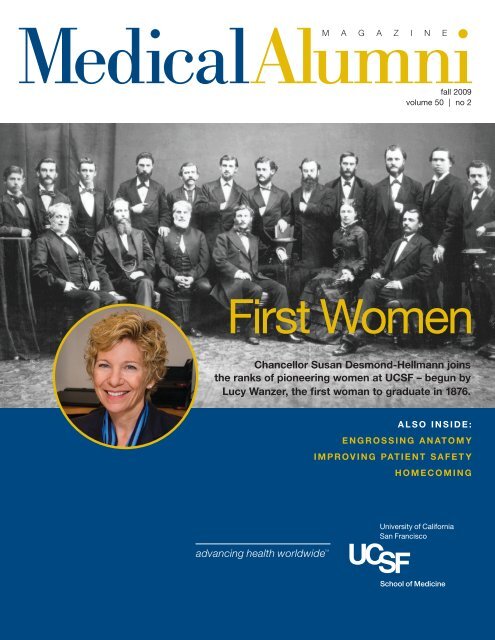

Medical<strong>Alumni</strong>M A G A Z I N Efall 2009volume 50 | no 2First WomenChancellor Susan Desmond-Hellmann joinsthe ranks of pioneering women at <strong>UCSF</strong> – begun byLucy Wanzer, the first woman to graduate in 1876.A l s o I N S I D E :e n g r o s s i n g a n at o m yimproving patient safetyhomecoming

NEWSHawgoodAppointed DeanSam Hawgood, MBBS, has beenappointed dean of the School ofMedicine and vice chancellor formedical affairs.In a message to the campuscommunity,ChancellorSusanDesmond-Hellmann, MD,MPH, said,“The School ofMedicine andthe campus asa whole havebeen fortunateto haveDr. Hawgoodin the role ofinterim deanSam Hawgoodduring the past year and a half.Facing unprecedented financialchallenges, he has more thansucceeded in his goal of‘responding responsibly to shortto-mediumterm constraints onresources while maintaining anaggressive strategic and solutionfocus on investments.’ Histransparency, accountability andwillingness to tackle the mostsignificant challenges, even while inan interim role, have created a levelof confidence, cooperation andrespect in the school that can onlyserve to promote further growthand excellence. Dr. Hawgood hasproven himself to be a true leaderand the right one for the <strong>UCSF</strong>School of Medicine at this criticalpoint in our history.”Hawgood, who earned hismedical degree from the Universityof Queensland in Australia and hasspent his career at <strong>UCSF</strong>, is adistinguished physician-scientist,professor in the Department ofPediatrics, and associate directorof the Cardiovascular ResearchInstitute. Prior to his appointmentas dean, he served as chair ofthe Department of Pediatrics,physician-in-chief of <strong>UCSF</strong>Children’s Hospital, and presidentof the <strong>UCSF</strong> Medical Group.EditorialTraining Physicians for an Unknown FutureWill we have enough physicians by 2025? Will they be the right kind of physicians?Somew<strong>here</strong> in my medical training I learned that the shelf-life of medical truthwas about six months. It appears the same could be said for medical workforceprojections. According to the AAMC Statement on Physician Workforce, publicpolicymakers in the 1980s predicted the United States would experience asubstantial excess of physicians by 2000. As a result, steps were taken to reducethe physician supply to avert the predicted surplus. This led to essentially flatenrollment at medical schools over the past 20 years.It is pretty clear that those predictions were erroneous. Current projectionspredict a shortage of 124,000 to 159,000 physicians by 2025. Given that ittakes an average of 14 years to train a physician, we need to make significantchanges to our system of education and health care delivery. Such a limitedphysician workforce would have devastating consequences to health care accessand availability.Before we determine what should be done, we needto understand why the previous projections were so off.Their main tenet was that managed care would be thesolution to health care inefficiencies and cost overruns –which obviously did not happen. The populationprojections also did not accurately account for the rapidrise in people over 65, the fastest growing segment of theU.S. population today, and the growing epidemics of obesityand diabetes, both of which account for a very large partof health care costs.Current projections of the physician shortage are actually“PC” – or pre-health care reform. So their accuracy is trulyunknown and may not be known for some time – perhapsanother 20 years. But we can’t wait until then to stave offGordon Fungsuch a health care disaster.The AAMC recommended a 12-point program that firstcalled for a 30 percent increase in enrollment in accredited medical schools by2015 (from 2002) as well as establishing new medical schools. Otherrecommendations included expanding the number of graduate medical educationpositions to accommodate the additional graduates, expanding the Medicareresidency training allowance, assessing and promoting foreign medical schoolprograms, and increasing collaborations.At the University of California t<strong>here</strong> are plans to open two new medicalschools and increase enrollment in the existing schools. But the biggest challengefacing medical schools is training physicians for the future when the entirety ofhealth care delivery may be completely different. T<strong>here</strong> is a major push to evaluateand adopt the “medical home” model of health care delivery, w<strong>here</strong> primarycare providers serve as leaders to a team of nurse practitioners and physicianassistants. Should we be training our physicians to be managers rather thanclinicians? Is the master clinician a dinosaur of the past and inefficient bydefinition? Do we only want to enroll medical students who intend to pursueclinical roles and not research? These tough questions must be addressed byevery school if we are to meet the health care needs of the future.Gordon Fung, MD ’79, MPH, PhDEditorgordon.fung@ucsf.edumedical alumni magazine | 1

educationEngrossing AnatomyBy Anne KavanaghAlmost 60 years ago, Selvyn Bleiferheld a human heart in his handsand knew he was going topursue cardiology. “I remember itvividly,” he says.Bleifer was a first-year medicalstudent at <strong>UCSF</strong> in a course many citeas a rite of passage: gross anatomy.The Class of 1955 graduate can stillsharply recall his initial foray into theanatomy lab – bodies stretched out onmetal tables, the wafting odor ofpreservatives, a classmate quicklyfainting. And later, that beautiful heart.“You can look at a picture of one,”he says, “but it’s different having it inyour hands.”At the time, gross anatomy hadchanged little since the school’sinception in the late 1800s, and wouldchange little for the next half-century.But in 2001 advances in medicineand education would bring sweepingalterations to the teaching of anatomyat <strong>UCSF</strong>.An ancient disciplineAnatomy has perhaps the longesthistory as a discipline in medicaleducation. Yet Hippocrates neverdissected a human body. Neitherdid the esteemed Greek physicianClaudius Galen (A.D. 131-200), whoseinfluential but often erroneous writingson anatomy came from dissectingcats and pigs. Human dissection wasforbidden in most societies until 1240when a Roman emperor permittedit in order to better train doctorsand aid public health. By the early14th century, human dissections –mostly of executed criminals – werebeing conducted at leading Europeanuniversities.In 1865, the California Legislatureapproved a dissection law permittingpauper bodies to be studied byaccredited physicians. At TolandMedical College, the precursor tothe <strong>UCSF</strong> School of Medicine,highlights included “many opportunitiesfor performing autopsies inSan Francisco’s advantageousdissecting climate.” Early on grossanatomy assumed importance,evolving into a 400-hour, six-monthcourse. Four students shared onecadaver. Over time, new medical fieldsand findings transformed othercourses, but gross anatomy heldfirmly to its roots.Doing away with dissectionsThen in 2001 the School of Medicineintroduced a completely redesignedcurriculum. It promoted integration ofdisciplines, an early introduction ofclinical concepts, and expedited entryinto patient care. Eight “block”courses organized around centralthemes or systems constituted the first18 months. Gross anatomy wasintegrated into the introductoryprologue block and instruction wasreduced from about 250 hours to 60.To save time, the school decidedto use previously dissected cadavers,or prosections. Twelve students wouldgather around a body and a facultymember, who would lecture for twohours while pointing things out. “Itturned into a one-way informationhighway,” says Kimberly Topp, PT,PhD, a longtime <strong>UCSF</strong> anatomyprofessor who is now chair of theDepartment of Physical Therapy andRehabilitation Science. “The students’eyes would glaze over.”A second problem: fitting in allpertinent body parts and functions.“The first year, t<strong>here</strong> wasn’t enoughtime for the head and neck,” saysTopp. “Then the head and neck wasadded, but t<strong>here</strong> wasn’t time for upperand lower limbs. So only upper limbswere covered.”Something else was lost, too,something elemental and profound.“You need the hands-on experience ofworking with a human body,” saysAllan Basbaum, PhD, chair of theDepartment of Anatomy. “It signifies:Welcome to the real world. You aredealing with someone who has died.”Laying on of the hands, againAfter two years of prosections,Basbaum charged Topp withrevamping the anatomy curriculum.She focused on making the learningmore interactive, peer-driven andintegrated. As such, dissectionsbecame paramount once again. “Thecadaver is really the students’ firstpatient, and they need to learn asmuch as they can from it,” she says.Today 110 hours are devoted toanatomy. Students spend eight weeksin the prologue block dissectingaspects of the entire body as anintroduction – the “10,000-foot view”as one student describes it.2 | fall 2009

Then they go back and tackle theindividual organs in the blockpertinent to that organ’s system.The heart, for example, isdissected when they are studyingthe cardiovascular, pulmonaryand renal systems. This allows forunderstanding in context, explainsTopp. “If you are learning aboutEKG, it’s best to put the anatomytogether with everything t<strong>here</strong> is toknow about the heart, includingphysiological assessment and<strong>UCSF</strong> anatomy lab, 1950s“You need the hands-onexperience of workingwith a human body.It signifies: Welcometo the real world. You aredealing with someonewho has died.” – Allan Basbaummedical treatment.” Opportunitiesto practice clinical procedures suchas suturing and inserting a chesttube have also been added.Five to six students are assignedone cadaver for the duration andmostly left on their own to proceed,with guidance from circulatingfaculty. “They have to figure outhow to work together,” says Topp.“That in itself is so importantbecause medicine today is a veryinteractive practice.”Though far from the timeintensivetradition that most Schoolof Medicine alumni experienced,Basbaum is confident the educationremains effective. “I don’t think weare hurting the training of studentsby cutting back,” he says. “Theydon’t need to know every detailupfront, such as all the digitalnerves. If they are going to becomehand surgeons, then they cango back and learn them.” Toppconcurs, “Immersion is great ifyou are going to be an anatomyinstructor. But if you are going tobe a physician, I’m not sure it’sthe best way to learn anymore.”And both say that despiteadvances in computer simulation –and the expense of obtaining andmaintaining cadavers – dissectionwill stay. “It is absolutely a definingexperience,” says Basbaum.A body of knowledgeIt certainly was for MatthewSchechter, now in his second yearat <strong>UCSF</strong>. “In that very first week ofmedical school, you are suddenlyand forever different from thenon-medical community,”he says. He and his five lab-mateswere assigned a well-muscled andtattooed cadaver. “I was surprisedat the humanity. It’s hard todescribe.” They named him Mick.Over the ensuing months, theygrew to know Mick intimately,and one another. “You can’t spend10 hours a week hovering over acadaver together and not bond,”he laughs. Schechter says thekinesthetic and emotionalexperience of dissecting a bodycreated an understanding that nocomputer or prosection ever could.“I liken it to the difference betweenreading a map of a city and walkingthough it,” he says. “For the rest ofmy career, whenever I’m faced withanatomy, it’s Mick I’ll picture. Notsome abstract concept of vessels,but his vessels. He gave me the giftof knowledge.”Honor your favorite professor!To find out how, contactCarrie Smith, director of developmentand alumni relations,at 415/476-6341 orcsmith@support.ucsf.edu.The <strong>UCSF</strong>Willed BodyProgramIt’s one last way to be useful.That’s one reason why peopledonate their bodies to the <strong>UCSF</strong>Willed Body Program, says AndrewCorson, the program’s coordinator.And it is indeed useful.<strong>UCSF</strong> receives about 300donated bodies a year through theWilled Body Program.Since its inception in 1947 theprogram has supplied cadavers for<strong>UCSF</strong>’s medical and dentalprograms. Today it also suppliescadavers for <strong>UCSF</strong> pharmacy andphysical therapy programs and foranatomy programs at the Cal Stateand community college systemsand private universities throughoutnorthern California. The WilledBody Program also supportsresearch projects such as thetesting of new orthopedic devices,surgical procedural training, alliedhealth education and postgraduatemedical education.About 60 percent of donationsare committed in advance of deathby individuals; the rest comethrough families of the deceased.The bodies come from all overnorthern California, from San LuisObispo to the Oregon border.“Medicine has changed by leapsand bounds, but the fundamentals– the human body and how itworks – have not changed,” saysCorson. “People will always needto know the essentials, and theWilled Body Program is helpingkeep that foundation solid byserving as stewards to donors.Their selfless final act makes sucha difference in our world.”medical alumni magazine | 3

IMPROVING PATIENT SAFETY“First,Do NoHarm”By Elizabeth Chur“ Until 10 years ago, wewere taught in the healthprofessions to believethat errors were manifestationsof bad, careless people,”says Robert Wachter, MD,chief of the Division of HospitalMedicine at <strong>UCSF</strong>. “We nowknow that most errors are madeby competent, well-trained,caring people trying to becareful, and the errors simplydemonstrate they are human.”In 1999, an Institute of Medicinereport entitled “To Err is Human:Building a Safer Health System” sentshockwaves through the medicalcommunity. It estimated that up to98,000 people died each year due tomedical errors.Wachter has led <strong>UCSF</strong>’s efforts toimprove patient safety. In twobestselling books, Internal Bleeding:The Truth Behind America’s TerrifyingEpidemic of Medical Mistakes, andUnderstanding Patient Safety, Wachterchampions a new perspective. Insteadof blaming individuals, he argues forsystemic changes to prevent mistakesfrom happening in the first place.“The most common causes ofmedical mistakes are communicationlapses – information didn’t make itfrom place A to place B correctly, orfrom person A to person B correctly,”says Wachter. Common mistakesinclude giving a patient the wrongdrug or dose, performing surgery onthe wrong patient or body part, ormaking the wrong diagnosis.One example of how bettercommunication has increased patientsafety at <strong>UCSF</strong> is the way medicalresidents entrust their patients to otherphysicians at the end of their shifts –the handoff process.Previously, this process washaphazard. Residents would spendlots of time hunting down keyinformation – vital signs, lab reportsand medication lists. Arpana Vidyarthi,MD, who arrived at <strong>UCSF</strong> as a hospitalmedicine fellow in 2002, says, “Idistinctly remember seeing residentsthrow down a stack of index cards,two inches thick, with information for50 patients hand-scribbled on them,and say to the next person, ‘T<strong>here</strong>’snothing to do.’ Given how sick many ofour patients are, this would cause meanxiety as I recognized the potentialfor harm during the cross-coverage.”In 2003, the Accreditation Councilfor Graduate Medical Educationlimited residents to an 80-hourworkweek and maximum 30-hourshifts. Vidyarthi, who is now director ofpatient safety and quality programs forthe Dean’s Office of Graduate MedicalEducation, says, “The reductions inwork hours were designed to reduceerrors caused by fatigue.” However,this has resulted in more frequenthandoffs among residents, which alsoincreases the risk of communicationerrors.With the assistance of <strong>UCSF</strong>Medical Center, Vidyarthi andJonathan Carter, MD (then a <strong>UCSF</strong>surgery resident) developed acomputer-based system dubbedSynopSIS. It provides a snapshot ofthe most important informationresidents need to know duringhandoffs, including the patient’sphysical location and list ofmedications, why the patient wasadmitted, and anticipated problems.Drawing on his or her understandingof each patient’s case, the outgoingresident prepares a list of “if-then”statements: if the patient develops afever, then test for infection and startcertain antibiotics; if the patient4 | fall 2009

ecomes short of breath, then get anX-ray; if the patient is dying, call hisdaughter in Philadelphia at this phonenumber. Before SynopSIS, these vitalpieces of information too often got lostin the handoff process.Vidyarthi trains residents in bestpractices for these face-to-facemeetings between outgoing andincoming residents. She recommendsthat they find a quiet place w<strong>here</strong>they can review SynopSIS information.She also reminds them that toneof voice and facial expressionsprovide valuable information. Beforethe meeting ends, the incomingresident repeats back his or herunderstanding of the departingresident’s recommendations.“At the beginning of your internship,it takes a little longer, as you learn howto sign out effectively,” Vidyarthi says.“By mid-year, using SynopSIS andverbally signing out is so ingrained inthe culture that nobody thinks twiceabout it – it’s like driving.”1 picture = 1,000 wordsThe opportunities to improve patientsafety continue after discharge. “Whatgoes on after the hospital, and inbetween visits?” asks Dean Schillinger,MD, director of the <strong>UCSF</strong> Center forVulnerable Populations at SanFrancisco General Hospital (SFGH).“Ninety-nine percent of the care isgoing on at their homes,” Schillingersays. “The number of medications, theseverity of people’s illnesses, and theexpectations we have for patients toself-manage their conditions haveincreased. The potential for patientsafety issues to arise in the outpatientsetting has worsened.”For example, Schillinger andEdward Machtinger, MD, found thatnearly 50 percent of patients on bloodthinners were unaware that they weretaking their medication improperly.“These are very high-risk populationstaking high-risk medications,” saysSchillinger. “I call it the ‘GoldilocksRobert Wachter,Arpana Vidyarthi andAndrew Auerbach reviewpatient safety data.medical alumni magazine | 5

medicine’: You have to take it justright. You can’t take too much, or youmay bleed and die; you can’t take toolittle, or you may have a stroke anddie.” Often, patients need to takedifferent amounts of the drug ondifferent days, further increasingthe likelihood ofincorrect dosage.Schillinger andMachtingerdeveloped a visualmedication schedule(VMS), a computergeneratedweeklycalendar showing thetype and amount ofmedication to be takeneach day, with writteninstructions in the patient’s nativelanguage (see image above). They alsohad patients “teach back” the dosageinstructions to their doctors, sodoctors could confirm that patientsunderstood correctly. Their studyshowed that patients who receivedthe VMS plus the “teach back”opportunity reached the target safelevel for their anticoagulant almosttwice as fast as patients who didnot use this method. This tool wasespecially effective among Spanishspeakingpatients.“Do the right thing” by defaultMuch of the Department of Medicine’ssafety and quality research is focusedon how to get a life-saving treatmentto its ultimate destination: the patient.“How do you get physicians toadopt it?” asks Andrew Auerbach, MD,MPH, associate clinical professor ofmedicine and director of researchfor the Division of Hospital Medicine.“How do you get systems to deliverit regularly? Moreover, how do youmeasure that implementation process?In business, t<strong>here</strong> are whole areas ofmanagement theory around how tomanage change in complex systems.But in health care, that’s a veryunderdeveloped field.”Auerbach recently redesigned<strong>UCSF</strong>’s physician order forms to, inhis words, “make it easier to do theright thing, and harder to do thenot-right thing.” For example, deepvein thrombosis, or clotting of theblood in a vein such as the leg, canVisual medicationscheduleoccur shortly after surgery. It can befatal if a clot travels to the lungs andobstructs blood flow, causing what iscalled pulmonary embolism.Fortunately, this is completelypreventable – if a patient receives theappropriate blood thinner. Untilrecently, however, only half of <strong>UCSF</strong>surgery patients received bloodthinners. This was partly becauset<strong>here</strong> was no systematic way forsurgeons to prescribe them. Threeyears ago, Auerbach developed aneasy-to-use order form and trainedsurgeons on the importance ofprescribing blood thinners.“T<strong>here</strong> are three legs to a qualityimprovement stool,” says Auerbach.“Education – explain why this is theright thing to do; change the system;and then audit and feedback – wepull charts at random, and if patientsdid not get the right drug, we senda report to the physicians involved.”Today, 95 percent of eligible <strong>UCSF</strong>surgery patients receive the properblood thinners.Auerbach is also developing theHospital Medicine Reporting Network.This network shares patient qualityand safety data to provide benchmarkinginformation. This allowshospitals to see w<strong>here</strong> they need toimprove and what they can learn fromother institutions. “It’s entirely possiblethat t<strong>here</strong>’s some innovation out t<strong>here</strong>that would be easily disseminated to“The number of medications, the severity ofpeople’s illnesses, and the expectationswe have for patients to self-manage theirconditions have increased. The potentialfor patient safety issues to arise in theoutpatient setting has worsened.”— Dean Schillinger, MD, director of the <strong>UCSF</strong> Center forVulnerable Populations at San Francisco General Hospitalothers,” says Auerbach. “I think ofthat as the ‘gene discovery’ of quality.We have the ability now with largedatabases to start sifting around forthose gems.”A little fear is healthy“If t<strong>here</strong> was a way to have gottenthis job done without scaring people,that would have been better,” saysWachter. “Systems are so recalcitrantto change that unless people did havesome anxiety about the current stateof affairs, we wouldn’t have changeda thing.“I got a call from a reporter from astate in the Midwest that had justbegun requiring hospitals to reportserious errors,” says Wachter. “Onehospital had 15 reports, and anotherhospital had zero. I said, ‘You wouldn’tcatch me dead going to the hospitalwith zero – because they either havea culture in which nobody talksabout these things, or they’re lying.’The state of medicine is such that youcan’t have a hospital that does notperiodically harm or kill somebodythrough errors.“What I want to see is that hospitalsare open and honest, using each erroras an opportunity to make themselvesbetter,” says Wachter. “I’m very proudof our organization, because I thinkthat’s what we’re doing. This is w<strong>here</strong> Iget my health care, and I know what’sin the sausage factory.”6 | fall 2009

PROFILE: ROBERT WACHTERHealing Patients and Health Care SystemsBy Elizabeth Chur“ Growing up Jewish in the New York suburbs, thefirstborn son of a socially climbing family, I thinkyou begin thinking about medicine in utero,” saysRobert Wachter, MD, with a chuckle. “The tension for mewas that I was a politics junkie, and found myself muchmore drawn to reading about politics and history than Iwas chemistry or biology.”Wachter, an international leader in the patient safetyfield, grew up on Long Island, the oldest of three children.His father ran a women’s clothing company started by hisgrandfather, an immigrant from Poland. In high school,Wachter volunteered at a local hospital and found mentorsamong the physicians. Although he wanted to become adoctor, he joined the debate team and majored in politicalscience at the University of Pennsylvania.“I enjoyed trying to understand how things wereorganized – how complex enterprises moved and changed– how people were motivated to do their work better,which is what you study in political science,” says Wachter.“I always thought I would have these dual lives: one as aphysician, and then I would come home and read theNew York Times. It never dawned on me that I would havea career w<strong>here</strong> I could combine those two interests.”He went to medical school at Penn, w<strong>here</strong> he founda mentor in John Eisenberg, one of the nation’s firstMD/MBAs. “He was a great doctor and teacher, but hisresearch involved thinking about the health care system:how we pay, how it’s organized, and how the work force isconstructed,” says Wachter. When Wachter came to<strong>UCSF</strong> for his internship and residency, he met StevenSchroeder, MD, then the founding chief of the Divisionof General Internal Medicine, who went on to lead theRobert Wood Johnson Foundation. “T<strong>here</strong> seemed to bea niche for people who had these dual parts of their brain,”says Wachter. “That was an epiphany for me.”Founding a new specialtyIn 1995, Lee Goldman, MD, then the chair of theDepartment of Medicine, appointed Wachter to run theinpatient medical service. “Lee always was looking toimprove systems, and charged me with finding ways tomake our medical service better,” Wachter says.Thus emerged the “hospitalist,” a term that Wachterand Goldman coined in a 1996 New England Journal ofMedicine article. Like orchestra conductors, thesehospital-based specialists oversee all the elements of ahospitalized patient’s care – lab reports, medication lists,reports from surgeons, specialists and others – andweave together the big picture, making connectionsbetween disparate pieces of information and ensuring thatthe whole patient receives the best care possible.In 2007, Wachter was named chief of the Division ofHospital Medicine. The growth of the hospital medicinefield has been astonishing: the Society for HospitalMedicine now has 7,000 members, and the AmericanHospital Association estimates that t<strong>here</strong> are more than20,000 practicing hospitalists in the United States – makingthis one of the fastest growing specialties in the history ofAmerican medicine.“As a new field, we were branded in part as being aboutsaving money,” says Wachter. “But it seemed to me that themodel should also improve the quality of care.” He waspresident of the Society of Hospital Medicine when the1999 Institute of Medicine report was released, stating thatup to 98,000 patients a year are killed annually by medicalerrors. “A light bulb went off, and I said, ‘We need to be atthe forefront of making this better.’”Putting it all together“One of my mantras is that all hospitalists have two sickpatients,” says Wachter. “One of them is the person in thebed, and one of them is the building that we’re working in.Both are in intensive care, and both need a lot of help andexpertise. It’s our job to fix both.“T<strong>here</strong> were already people focusing on silos withinpatient safety: information technology, diagnostic errorsand medication safety,” says Wachter. “Part of this is mypolitical science background, and part of this is mygeneralist mindset: I like to be the person who sees the bigpicture and explains things in ways that are accessible.”He has spent much of his career doing just that.In addition to publishing six books and 200 articles,Wachter edits the federal government’s two leading patientsafety websites (webmm.ahrq.gov and psnet.ahrq.gov).He also has his own lively and accessible blog (www.wachtersworld.org).“I have the world’s best job,” he says. “I get to be aphysician, teacher, mentor, writer, speaker and administrator– and to do it in a great organization with wonderfulpeople who have terrific values. Every day I feel like I’vewon the lottery. I don’t ever tell anybody this, but if I couldfigure out how to live, I’d probably do it for free.”medical alumni magazine | 7

COVER STORY: first womenBy Kate VolkmanFrom the moment Lucy Wanzer fought herway in to Toland Hall in 1874, becomingthe first woman admitted to what wouldbecome the <strong>UCSF</strong> School of Medicine, thewomen of <strong>UCSF</strong> have been making nationalnames for themselves and the University.As the only woman, Wanzer was 0.18percent of her class. Over the last 135 yearsthe numbers of women in the medicalschool have increased progressively, sothat the <strong>UCSF</strong> Class of 2013 is 58 percentwomen. So too have women in medicalleadership become increasingly visible.Just this August, <strong>UCSF</strong> handed thechancellorship to a woman for the firsttime: Susan Desmond-Hellmann, MD, MPH.8 | fall 2009

Dorothy “Dee” FordBainton, MD, MSFirst woman to chair a departmentin the <strong>UCSF</strong> School of MedicineBy the time Dee Bainton gave birth to her first child, she hadgraduated from Tulane School of Medicine (one of fivewomen in a class of 128) and completed her internal medicineresidency at University of Rochester and University ofWashington. Her husband accepted a position as a residentin anesthesiology at <strong>UCSF</strong>, and upon their move she plannedto be a full-time mother and housewife.“I thought if you had a child in 1961, your job was to stayhome,” Bainton says. “After about four months, my husbandsaid, ‘You need to go back to work.’ I guess I was reallymissing it. So I started looking for a position.” She found onewith Marilyn Farquhar, MD, in the Department of Pathologyat <strong>UCSF</strong>. That began her climb up the academic andadministrative ladder.Bainton joined and headed multiple committees, andreceived numerous awards. In 1987 the dean asked her toapply for the position of chair of the Department of Pathology.Throwing her hat in the ring had never occurred to her –mostly because she was doing research and was happy,but also because she had been diagnosed with metastaticbreast cancer three years prior. She was in recovery, but still.Bainton took two weeks to weigh the pros and cons. “Con:If I fail as a woman chair, it is bad for all women. Pro: If theleadership at <strong>UCSF</strong> didn’t see me as disabled, why should Isee myself as disabled?”Ultimately she accepted the position and served as chair forseven years, until 1994 when the new chancellor invited her tobe vice chancellor for academic affairs. Under her leadership,among many things, mentoring and training programswere established and maternity leave was extended from sixweeks to 12, with pay. Bainton filled the position for 10 years,until she retired in 2004.This year, Bainton, 75, was awarded the <strong>UCSF</strong> Medal, aprestigious honor. She recalls, “Chancellor Bishop told me thatafter it was announced women would walk up to him in thehallway and say I’d been a mentor.” In her acceptance speech,Bainton replied, “It’s really wonderful to be called a pioneer,but I realize that I’ve just ridden the crest of the wave that’sswollen over the last 50 years for women.”NancyAscher, MD, PhDFirst woman to performa liver transplantWhen Nancy Ascher told her parents she wanted togo to medical school, they were delighted. Whenshe told them she wanted to specialize in surgery, theywere concerned. “They were worried about lifestyle,”she says. “Would I be able to have a family?“It was the field that excited me the most. It seemedas though I could combine something really fun withasking questions at the same time. And the gratificationof being able to make a difference in somebody’s lifevery quickly was appealing to me.”Ascher, 60, graduated from medical school at theUniversity of Michigan in 1974. She was one of 20women in a class of 180. “When I was applying,”she remembers, “women had to be interviewed byPsychiatry to see what our motivation was. We hada lot of opportunities and a lot of scrutiny at thesame time.”She completed her residency in surgery – the onlywoman of seven – and fellowship in transplant at theUniversity of Minnesota, w<strong>here</strong> she was named clinicaldirector of the liver transplantation program. It wast<strong>here</strong>, in 1981, that she became the first woman totransplant a liver. “Transplant patients are very gratefulpatients,” she says. “They really have an idea of theincredible miracle transplant is for their lives.”In 1988, <strong>UCSF</strong> recruited her to build its livertransplantation program. In 1991, she was named chiefof transplantation, a position that was passed on to herhusband, John Roberts, MD, when she became thefirst woman to chair the Department of Surgery in 1999.Ascher and Roberts did have a family, but theyjust got started a bit later than others. Their daughterwas born when Ascher was 41 and their son threeyears later. In the meantime, Ascher and her team ofsurgeons boast renowned transplantation programs.“When I arrived, t<strong>here</strong> already was a world-classkidney program,” she says. “I think we raised itsstature to a new level. And we built a world-class livertransplant program that maybe is second to none.”10 | fall 2009

DianeWara, MDFirst associate dean for women’saffairs at any medical schoolDiane Wara counts her role as first associate dean for women’saffairs as one of her most important firsts. After graduatingfrom medical school at UC Irvine and completing her internshipat Harbor General Hospital in Torrance, Calif., she came to <strong>UCSF</strong>to finish her residency in the Department of Pediatrics. As one oftwo women residents, and the only one with a 3-week-old child,the department chair arranged an apartment on campus for herto use during nights on call.“T<strong>here</strong>’s a risk and a benefit to being early and first,” Wara,67, says. “The risk is no one’s been t<strong>here</strong> to grease your path.The benefit is people treat you specially.”For her next first, Wara became the first woman fellow inallergy-immunology at <strong>UCSF</strong>. In the early 1980s she was amongthe group who first identified HIV-positive babies. Then in theearly 1990s, Wara was one of those who introduced the idea thatif HIV-positive pregnant women were given one of severalanti-HIV drugs just before delivery, they would have a greaterchance of giving birth to babies who were HIV-negative. Thistreatment is now the international standard.Wara was named chief of the Division of Pediatric Immunologyand Rheumatology in 1985 – the first woman division chief inany medical department at <strong>UCSF</strong>. She was a member, along withDee Bainton, of the Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on theStatus of Women, and worked to change not only the maternityleave policy, but the availability of child care at <strong>UCSF</strong>. The newchild-care centers at Mission Bay and at 5th and Kirkham, aswell as the expanded facility at Laurel Heights, are direct resultsof her efforts.From 1991 to 1996 she held the position of associate dean forwomen’s affairs, adding minority affairs in 1996 until 2002. Of theappointment, she remarks, “No other institution had identifiedmoving women up the academic ladder and into leadership spotsin a fair manner, with fair pay, and a fair job description.”One might consider Wara an activist – a title she’s happy toaccept. She says, “I have a long history and interest and successin working with women’s issues. It takes a community to makechange, and I like doing it. I like helping turn <strong>UCSF</strong> into a betterplace to be. That’s what a good citizen does, right?”JulieGerberding, MD, MPHFirst woman director of the U.S.Centers for Disease ControlAs a 4-year-old, Julie Gerberding collectedbugs, building her first laboratory in the familybasement and laying the foundation for her careerin public health. As the director of the Centersfor Disease Control (CDC), she led the nation’sagency that fights epidemics and environmentalhealth threats, including bioterrorism, AIDS andinfluenza pandemics.After graduating with her medical degree fromCase Western Reserve University in 1981, Gerberdingcompleted her internship and internal medicineresidency at <strong>UCSF</strong>. It was the early years of the AIDScrisis, and Gerberding continued her training with afellowship in clinical pharmacology and infectiousdiseases. She went on her earn her master’s degreein public health from UC Berkeley in 1990.Gerberding joined the CDC in 1988 as directorof the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, apart of the National Center for Infectious Diseases(NCID). In 2001 she was appointed acting director ofthe NCID and almost immediately drew attention forher honest, calm and decisive handling of theanthrax attacks.In 2002 she was promoted to director of theCDC. Just six months later SARS hit, and again,Gerberding was the voice of reason for an alarmedAmerican public. Next, she handled a rare outbreakof monkeypox, a return of the West Nile virus,and a threat of avian flu. She initiated a “HealthyPeople at Every Stage of Life” campaign, whichintroduced programs for smoking cessation,screening for heart disease and stroke, and pushesfor increased physical education in elementaryschools. Gerberding stepped down from the postearlier this year.Today, in addition to being a wife and mother,Gerberding, 54, is an associate professor of medicineat Emory University in Atlanta and at <strong>UCSF</strong>.medical alumni magazine | 11

2009 REUNIONCelebratingthe yearsBy tina vuWhen: May 8–9, 2009Classes celebrating reunions:1949, 1954, 1959, 1964, 1969,1974, 1979, 1984, 1989, 1994Money raised for medicaleducation by classes in honorof their reunions: More than$300,000Number of attendees: 37012 | fall 2009It was a symphony of sorts in the Grand Ballroomat the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. Pianomusic cascaded from the fingertips ofperforming medical students while glassesclinked in accompaniment. The laughter at theDean’s Reception joined in harmony.Ten classes came to celebrate their Schoolof Medicine reunions the weekend of May 8–9.At the table designated for the Class of 1954,Charles Aronberg, Harold Karpman, Harry Rothand Joseph Sabella greeted one another withtwinkling smiles and hearty hellos. The classmates,whose friendships began in the anatomylab, reminisced about penny-pinching mealsof horse meat and their thirdyearrotations in dermatology,psychiatry and neurology.Absent from the group of longtimefriends were Morton Rosenblum,who died earlier this year, andDaniel Kaplan.The friends, now split betweenNorthern and Southern California,reconnect during reunion, closingthe gap that careers, family andlife create in the years between.Their friendship embodies thespirit of homecoming, w<strong>here</strong>bonds formed in the classrooms at <strong>UCSF</strong> arefound – and treasured – again.“We went through a lot together,” Roth said.“It was a rite of passage. T<strong>here</strong> was suffering, butt<strong>here</strong> was joy.”Although they regularly attend the school gettogethers,the friends found a special occasionto celebrate this year: Two among the group –Aronberg and Karpman – received the AlumnusAbove: Anatomy buddies from the Class of 1954: HarryRoth, MD, Charles Aronberg, MD, Harold Karpman,MD, and Joseph Sabella, MD; below: the Class of 1959celebrated their 50th reunion50th

MAA President Larry Lustig, MD ’91, with theSadie Berkove Award winners: Angela Feraco,Aruna Venkatesan, Melissa Fitch, Laura EpsteinRuth Matsuura, MD ’54,and Sarita Johnson,MD ’54Stacy Globerman, MD ’84, Andrew Oliveira, MD ’84, LornaMcFarland, MD ’84, Moira Cunningham, MD ’84, David Friscia,MD ’84, Andres Betts, MD ’84, Ellen Hughes, MD, PhD ’84of the Year award during the reunion luncheon(see story on next page).As members of the Class of 1954 took to thestage to announce the winners, the banter thatbegan the night before continued. In introducinghis classmate and one of the Alumnus of theYear recipients, Sabella noted that Karpman’sCV would run “as long as both my arms, bothmy legs, and pasted back and front.” He said,“From the beginning, I knew my friend Halwas exceptional.”Karpman accepted the award and describedthe rewards of medicine as “a joy that Iexperienced and continue to experience everyday.” He also thanked his wife, Molinda, forgiving him the opportunity to do so. Molinda,whose own efforts produced a 150-page,photo-filled memory book for the 55th yearreunion class, began to cry. Sabella turned toher and said comfortingly, “Your husband issuch a sweet guy, he truly is.”Roth introduced Aronberg, the otherAlumnus of the Year, as “a man I’m proud toknow and who has always made me smile.”Aronberg proved Roth’s words as he approachedthe podium and strategically dropped forks,a banana, paper scraps and jokes in search ofhis reading glasses. But even wrapped in hishumor, Aronberg’s warmth shone through asthe ophthalmologist encouraged the room.“T<strong>here</strong>’s a lot you can do, and I hope you doit,” he said. “Take care of your patients, yourfamily, your friends and yourself.”The Class of 1984 celebrated their 25th reunionGerald Van Wieren, MD ’79Leon Smith-Harrison, MD ’79Wesley Moore, MD ’59, Ronald Stoney, MD ’59,Philip Morrissey, MD ’59, Donald Gillies, MD ’59,Donald Webb, MD ’59, Stephen Gaal, MD ’59Rochelle Nagel, PhD, Ted Schrock, MD ’64, BarbaraJorgensen, Jerren Jorgensen, MD ’64 (behind), BarbaraSchrock, Jacqueline Etemad, MD ’64Malcolm MacKenzie, MD ’59,and Natalie MacKenzieMel Hayes, Michael Gyepes,MD ’59, Barbara Bigelow,Welby Bigelow Jr., MD ’5925thmedical alumni magazine | 13

ALUMNUS OF THE YEARAronberg, Karpman Share MAA’s Highest Awardby tina vuOn His HonorAlthough it’s been many years sincehe served as a leader of the CubScouts and Boy Scouts – and evenmore since he was a Scout himself –Charles Aronberg, MD ’54, can stillrecite the Scout Law.A Scout is trustworthy, loyal, helpful,friendly, courteous, kind, obedient,cheerful, thrifty,brave, clean andreverent.When Aronbergwas a young boyin Chicago, hisfather died andhe was desolate.When peoplewere kind to him,giving him hope,“I never forgotthem,” he says.He attended aBoy ScoutMAA President LarryLustig with CharlesAronbergmeeting, w<strong>here</strong>he was furtherinspired, and hislife changedforever. Aronberg wanted to helpothers, and the path led to medicine.“One person can make a difference,”says Harold Karpman, MD ’54,of Aronberg, his fellow Alumnus ofthe Year.Since graduating from <strong>UCSF</strong>,Aronberg has served on the MedicalBoard of California, as chief of ophthalmologyat Cedars-Sinai MedicalCenter, chair of the Los AngelesCounty Hospital Commission, andophthalmologist for the Los AngelesLakers, Dodgers, Raiders and Kings,and the United States Olympic Team.He was an Olympic torch bearertwice and even mayor of BeverlyHills. But for the doctor, these arejust titles.“It’s what you do for people and forthe world that is important,” he says.As a physician, Aronberg takescare of men, women and children,helping with their sight and their lives.As a public servant, he has helpedimprove airline and automobile safety,reduce air and water pollution, expandthe national park system, and hashelped make the Beverly Hills Policeand Fire departments and paramedicsNo. 1 in the country – work he hasdone concurrently with his full-timemedical practice.As a family man, he is a devotedhusband to his wife, Sandy, MD, aprofessor at the UCLA David GeffenSchool of Medicine and UCLASchool of Public Health, and fatherto Cindy, deputy controller of theState of California.“I need nine hours of sleep anight, but then I can work the other15,” Aronberg says. “When it’simportant, I never give up.”Fifty-five years after receiving hisMD, Aronberg continues to practiceophthalmology. He is renowned as aphysician and for his sense of humor.“Laughter is good medicine,” says theman nicknamed “Chuckles” by hismedical school classmates.With Scout-like loyalty, kindnessand cheerfulness, Aronberg is keepingthe oath he made many years ago.The Good DoctorHarold Karpman, MD ’54, is gentleand soft-spoken. In the offices ofhis Cardiovascular Medical Group(CVMG), Karpman is one of the mostrecognizable faces. In the world ofcardiology and medicine, Karpman isalso a well-known name.“Hello, Dr. Karpman,” one assistantsays smiling. “Hello, Dr. Karpman,”echoes another.The cardiologist ambles through hiswaiting area. His right hand reachesout and pats a small brunet boy on thehead. “Hi, Dr. Karpman,” the boy says.CVMG is a 17-member, 100-employeepractice with three Los Angeles-arealocations. After his 6 a.m. patientvisits at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center,Karpman spends the majority of hisday at the Beverly Hills office, w<strong>here</strong>groundbreaking technology, excellentpatient care, and self- and industryfundedresearch meet. Karpman beganthe practice with Selvyn Bleifer, MD’55, and Dan Bleifer, MD ’51, in 1958.“He will drop everything and talkwith patients over and over again,and not think twice,” says CaralynPoskin, Karpman’s assistant of morethan 25 years. “That’s hard to findnowadays. He’s just a gem.”The son of a pharmacist, Karpmangrew up in Los Angeles and servedin the Navy at the end of WorldWar II. He performed researchunder renowned cardiologistMyron Prinzmetal, MD ’33, beforeestablishing his own advancementsin the field. One of the manycompanies Karpman led in his careerdeveloped the world’s first 24-hourHolter monitor.The author of two books and morethan 150 publications, Karpman hasheld leadership positions in notableorganizations both public and private,serves as a clinical professor at theDavid Geffen School of Medicine atUCLA, and is a former professor atthe University of Southern CaliforniaMedical School.Ever humble, Karpman wouldrather discuss his love of the arts.He has been a member of the boardof directors of the Los Angeles Opera,and he calls Placido Domingo a friend.Karpman shares that his daughter,Laura, composed an opera thatearned her a 10-minute standingovation at Carnegie Hall and wasperformed at the Hollywood Bowl inLos Angeles. His face glows whenhe talks about his family: his childrenDavid andLaura; hisgrandchildrenKai-Lilly andHuston; hisever-supportive,loving andbeautiful wife,Molinda.The gooddoctor displaysa similardevotion toCardiovascular pioneerHarold Karpmanhis patients.In giving a tourof the CVMGfacilities, Karpman stops to checkin with them, most of whom heknows by name. He will personallycall many the next day to give labresults. (“I think that’s owed to them,”he explains.)With a successful practice andloving family, Karpman has, in hiswords, “a corner office on life.” Headds, his voice soft, “I like w<strong>here</strong> Iam as a physician.”14 | fall 2009

Your MEDICAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATIONDear Fellow <strong>Alumni</strong>,Your representatives honored me with the role of president of the <strong>UCSF</strong>Medical <strong>Alumni</strong> Association for the next year. I look forward to workingwith you and the MAA to make it a valued organization for the nearly8,000 living graduates of our alma mater and its residency programs.By way of introduction, I’m a graduate of the Class of1967 and was chief medical resident at SFGH in 1972-1973. I escaped to Humboldt County, Calif., to practiceinternal medicine and oncology until 1991, at whichpoint I joined the U.S. Department of State. I was adiplomatic doctor in Mali, Bangladesh, the Philippines,South Africa and China until my retirement in late2006. I returned to San Francisco after 33 years awayand am happy as a clam, working a bit at the VA and volunteer teachingfirst- and second-year students at <strong>UCSF</strong>.The upcoming year promises to be a real challenge. Money is shorteveryw<strong>here</strong>. Our medical students are finding it more and more difficultto handle the ever-increasing tuition and expenses. Charitablecontributions are suffering and medicine is sure to change drastically inthe immediate future.The MAA and the School of Medicine need your help. We appreciateyour active involvement and hope that those of you who are not yet duespaying members of the MAA will see fit to join. On behalf of the Schoolof Medicine, we also ask you to consider contributing generously to theannual fundraising efforts for medical education, which support students.This year, we will initiate a new program in which a representative willbe chosen by each class to be the intermediary between the MAA andclass members. He or she will communicate regularly to seek informationabout you, your family and your career to be included in the <strong>UCSF</strong>Medical <strong>Alumni</strong> Magazine. The rep will also provide updates about what’shappening at your alma mater and with your fellow alumni. Please begenerous with your communication. If you are interested in serving asyour class rep, contact Gary Bernard, director of development and alumnirelations, at maa@support.ucsf.edu.Tell us what you think or send questions on any subject about <strong>UCSF</strong> orthe Medical <strong>Alumni</strong> Association. My email address is: chinadochill@yahoo.com.Lawrence Hill, MD ’67MAA PresidentTo join the MAA, visit www.ucsfalumni.orgTo contact the MAA, email maa@support.ucsf.eduUsed textbooks from <strong>UCSF</strong> reach health careproviders in Afghanistan.Book Drive for Iraq andAfghanistan a SuccessThe <strong>Alumni</strong> Association of <strong>UCSF</strong>(AA<strong>UCSF</strong>) teamed with OperationMedical Libraries last spring to receive,box and ship more than 3,000textbooks and journals to militaryhospitals in Iraq and Afghanistan. Thebooks were collected from individualswho had quite recently, or long since,become health care professionals.The call for books came fromValerie Walker, director of the UCLAMedical <strong>Alumni</strong> Association. Uponreceiving her request, members of theAA<strong>UCSF</strong>, alumni, faculty and studentsformed a network to get the word out toall members of the <strong>UCSF</strong> community.The effort first started in 2007 whenU.S. Army Major Laura Pacha, MD,a 1998 UCLA School of Medicinealumna serving in Iraq, saw the needfor such assistance. In an email toher alumni association, she wrote,“The war and ongoing fight againstthe insurgency has severely strainedIraqi medical sources.”Major Maureen Nolen, programcoordinator and recipient of materialssent from <strong>UCSF</strong>, wrote fromAfghanistan, “You may be aware thatprevious political regimes <strong>here</strong>destroyed many of the medical booksand learning materials. The currenteconomy is substantially challenged aswell, so replacing these materials forhealth care providers is a significanthardship for the facilities w<strong>here</strong> theywork. It is difficult to express to you inthis note the thrill I personally have seenin the eyes of the program participantswhen they are told that they may selectand keep a few of the books, journalsor other publications. Because of you,their elation is clearly evident.”<strong>Alumni</strong> who would still like to becomeinvolved with Operation MedicalLibraries can do so by visitingopmedlibs.medalumni.ucla.edu.medical alumni magazine | 15

ClassNotesWhat’s new? Your classmates want to know what’s going on in your life. Share your information atwww.ucsfalumni.org; mail it to <strong>Alumni</strong> Services, <strong>UCSF</strong> Box 0248, San Francisco, CA 94143-0248; or emailyour news and high-resolution photo to alumni@support.ucsf.edu. For best print quality, your photo resolutionshould be 300 pixels per inch or larger. To include as many alumni as possible, class notes published in thismagazine are edited for space. To read the full text of each note, please visit www.ucsfalumni.org.19 4 0 sn Arthur Anderson, MD ’49, and hiswife, June Ann, celebrated their 60thwedding anniversary in 2008. They havefive children, 13 grandchildren and fourgreat-grandchildren.n Armand P. Gelpi, MD ’49, andLucille have been married for 56 years andlive in Seattle.n William E. Latham, MD ’49,a board member of The Haggin Museumin Stockton, Calif., organized and escortedtrips to Europe as philanthropic supportfor the museum.Alumnus ReceivesLégion d’honneurPhysician Gordon M. Binder,MD ’43, was awardedFrance’s highest decoration,the Légion d’honneur, by Pierre-François Mourier, the ConsulGeneral of France in San Francisco.The ceremony took place onJuly 14 during the Bastille Daycelebration held at the WarMemorial Building. More than 400attended the event, during whichMourier recounted Binder’s acts ofvalor as a frontline surgeon inNormandy in World War II. Binderthanked the people of France forhonoring him and concluded bysaying, “I thank my creator forbringing me home alive.”16 | fall 2009n William Silen, MD ’49, teachesHarvard medical studentsin their third-year clerkship.He writes, “Ruth and Imoved to a wonderfulretirement community onthe Lasell College campus,which makes availableopportunities to learn, enjoyconcerts and lectures, and exercise.”n Donald B. St. Clair, MD ’49,practices three days per week atDel Norte Clinics Inc., which providesquality care to the underserved. He andMarilyn have been married 59 years.1950sn Aubrey L. Abramson, MD ’54,remains an emeritus member ofEI Camino Hospital and serves oncommittees three mornings a week.He collects antiquarian books, vintageoptical instruments and vintagephotographic material.n Mervyn Burke, MD ’54, andDelores continue a happy, healthy andretired life in San Francisco.n Olga Daiber, MD ’54, lives inDurango, Colo., and enjoys attendinglectures and concerts at Fort LewisCollege, taking jeep trips into themountains, exploring local archaeologicalsites and grandparenting.n Charles R. Geiberger, MD ’54,writes, “We are now ‘snowbirds,’spending the warm months on PugetSound and the winters in La Mesa.In the summer, all classmates areinvited for a free lunch or dinner and anovernight stay.”n Harriet B. (MD ’54) & J. Harold(MD ’54) Hanson live in Fresno, Calif.,and write, “After almost 58 years ofmarriage, our greatest accomplishment isour family.” They have three sons, threedaughters-in-law and six grandchildren.n Warren J. Newswanger, MD ’54,although retired, works a half-day for theSanta Barbara County Health Servicesgyn clinic and assists with ob-gynsurgeries when called in by anotherphysician.n Joseph D. Sabella, MD ’54, writes,“Iris and I have lived in Napa Valley forthe past 18 years. I am into woodworking,gardening and reading the many booksI had never had time to explore.”n Barton Byers, MD ’59, devotes fulltime to his vineyard, Bella Roccia, whichproduces premium cabernet grapes andItalian-style olive oil. He enjoys mountaineeringand fly fishing and writes, “I still planto catch a Permit and Taimen on a fly.”n Roy E. Christian, MD ’59, chasesicebergs, polar bears and penguins witha group called Bi-Polar and has traveledto Antarctica, Greenland, Baffin Island,Iceland, Alaska and many otherinteresting locations.n Eugene Dong, MD ’59, is anassociate professor emeritus of cardiacsurgery at Stanford University and anattorney specializing in scientific fraudand ambulance regulations.n Donald R. Gillies, MD ’59, leadstours as a docent at theSanta Barbara BotanicGarden, and volunteersas a naturalist with theChannel Islands NationalPark and the ChannelIslands National MarineSanctuary.n Carol K. Kasper, MD ’59, an emeritaprofessor of medicine at USC, works oneday a week at the Hemophilia TreatmentCenter, Orthopaedic Hospital, LosAngeles. She takes delight in artisticsewing, developing designs for quilts, children’sclothes and other fabric creations.n Herbert J. Konkoff, MD ’59,has practiced as a community-based

physician in San Francisco since 1966 andpresently performs outpatient proceduresat <strong>UCSF</strong> Medical Center at Mt. Zion. Hehas two children, four grandchildren, ninestep-grandchildren and three stepchildren.n Wesley S. Moore, MD ’59, is avascular surgeon specializing in surgeryof aortic aneurysm and carotid arterydisease. He and his wife, Patty (above),celebrated their 48th wedding anniversarywith a trip to game camps in Namibiaand South Africa.n Philip Morrissey, MD ’59, retiredfrom private practice and has stayedbusy ever since!n Carolyn J. Sparks, MD ’59,celebrated her 50th wedding anniversaryin June. She and Bob have three grandchildren,ages 7, 3 and 2.n Edmund E. Van Brunt, MD ’59,remains active with the Kaiser FoundationResearch Institute Institutional ReviewBoard. He and Claire celebrated their60th wedding anniversary with their threechildren and four grandchildren.n Donald E. Webb, MD ’59, a retiredorthopedic surgeon, has three childrenand four grandchildren.He writes, “The mostrewarding aspect of mypractice has been workingwith Orthopaedics Overseasand other internationalorganizations teachingand doing orthopedics.”n Belson J. Weinstein, MD ’59,enjoys his solo practice in preventivecardiology and internal medicine inPalo Alto, Calif. He has three children andthree grandchildren.n Elliott Wolfe, MD ’59, is the presidentand CEO of Arrowsmith Foundation, anonprofit that furthers the development ofcreative methods to advance the efficacyof medical education. Last fall, he receivedemeritus status at the Stanford UniversitySchool of Medicine and the Elliott WolfeAward for Excellence in the Teachingof the Art and Science of Clinical Medicine,presented annually, was establishedin his honor.n Maylene Wong, MD ’59, lives in SanFrancisco and is a consultant to the MarioNegri Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologichein Milan, Italy. She has traveled to Mt. Fuji,Mt. Stromboli, Brazil, Israel, Uganda, Borneo,Zimbabwe, Sri Lanka, South Africa and more.1960sn James W. Forsythe, MD ’64 (below),has an integrative oncology practice thatcombines immune stimulating therapiesand natural therapies for the treatment ofcancer with conventional standard-dose orlow-dose insulin potentiated chemotherapies.He writes, “My Salicinium study ofmore than 300 patients at three-and-a-halfyears has shown dramatic response rates,including in stage 4 cancers, adult cancers.”n Kevin D. Harrington, MD ’64,recently retired from orthopedic surgeryin San Francisco to practice golf. He isalso doing medical-legal evaluation work,traveling and oil painting.n Donald A. Lawson, MD ’64, wasrecalled from retirement to serve as theinterim chair of the Radiology Departmentat St. Joseph’s Hospital & Medical Centerin Phoenix. He and his wife, Joelle, travelextensively and took a 35-day cruisestarting in the South China Sea fromHong Kong through the Suez Canal toAthens in May.n Michael R. Nagel, MD ’64, returnedto an office-based, solo practice of clinicalcardiology with an emphasis on preventivecardiology.n David E. Smith, MD ’64, founderand former medical director of theHaight Ashbury Free Clinics, is semiretiredand serves as medical director atCenter Point in San Rafael, Calif., and aschair, Adolescent Addiction Treatment,at Newport Academy in Newport Beach,Calif. He writes, “My youngest daughterand her twin boys joined us inWashington, DC, for the historicinauguration of President Barack Obama.[See] more family photos and news atwww.DrDave.org.”n Evangeline Jang Spindler, MD ’64,is the training and supervising analyst atthe Michigan Psychoanalytic Council, pastpresident of the Michigan PsychoanalyticSociety, and faculty supervisor at thePsychodynamic Psychotherapy Program ofthe University of Michigan Medical School.n Robert J. Stallone, MD ’64, is thechief of surgery at Alta Bates SummitMedical Center in Berkeley. He enjoysbig-game hunting and has hunted in allthe western states, Canada, Alaska,Cameroon, Tanzania and Zimbabwe.n William R. Vincent, MD ’64, lessthan a year into retirement from a privatepractice in pediatric cardiology, writes,“I am adjusting to ‘every-day-is-Saturday’quite well.”n Stephen P. Ginsberg, MD ’66,partially retired from an ophthalmologypractice in Maryland, has been acceptedinto the doctoral program in bioethics atGeorgetown University. He has beenselected as one of the “Top Doctors”in Washingtonian Magazine every issuesince 1993.n Stephen L. Abbott, MD ’69,practices in a six-pediatrician office inSanta Barbara, Calif., with his son, David.He writes, “Barbe and I have been bestfriends for 49 years, and celebrated our44th anniversary in June.”n Michael H. Crawford, MD ’69,is interim chief of cardiology at <strong>UCSF</strong>.He writes, “[Janis and I] live in Tiburonand are enjoying being back in theSan Francisco area.”n Gregory J. Dixon, MD ’69, has takena year off from private practice in orthopedicsurgery to serve as themedical director of theTransitional CareCenter at MarshallHospital in Placerville,Calif. Also, he wasselected to be a guestprofessor at the KingFaisal SpecialistHospital in Riyadh,Saudi Arabia.medical alumni magazine | 17

Class Notes 1960s | continuedn Anthony Eason, MD ’69, retired fromKaiser San Rafael on November 30, 2008.He is writing the biography of Dr. DonaldSmith, who was the chair of urology at<strong>UCSF</strong> for 40 years.n Michael Fein, MD ’69, writes, “I stillenjoy meeting new patients and going towork every day, so I hope that retirementwill be far off. I have been able to adaptto the ever-changing medical world byremembering Herodotus’ aphorism,‘The only certain thing is change.’ ”n Lawrence M. Friedlander, MD ’69,a retired pathologist, lives in Grass Valley,Calif., w<strong>here</strong> he is president of hishomeowners association and thelocal chapter of the California <strong>Alumni</strong>Association. His daughter Paige is athird generation <strong>UCSF</strong> graduate.n Larry Hartley, MD ’69, joined thelocal community clinic, sees patientstwo days a week, and does surgery oneday a week. He writes, “My wife Pat andI have been married almost 43 years.We have four wonderful daughters, fourgreat son-in-laws and eight amazinggrandchildren.”n Phil Hinton, MD ’69, practicesvascular surgery part time in Fresno, Calif.,which includes teaching duties with the<strong>UCSF</strong> Fresno Medical Education Program.He writes, “I love riding my two BMWmotorcycles and steelhead fishing withTom Brandes, MD ’69.”n James C. Jones, MD ’69, retiredwith the rank of colonel from the military,w<strong>here</strong> he served as a cardiothoracicsurgeon at major medical centers.He writes, “I do home improvementprojects, and go hiking, mountain bikingand mountaineering. I have climbedseveral mountains in the Pacific Northwestand Mount Kilimanjaro.”n Mark Kuge, MD ’69, writes, “[Loisand I] are in the throes of completing thefinishing touches on a little grass shacknear the slopes of Diamond Head [Hawaii]and the Pacific Ocean. It has been almostone year in the making. Our two childrenhave homes nearby, so we are finally all onone island.”n Julie L. Lee, MD ’69 (above), joinedher husband in retirement and writes,“Our newfound freedom is spent withfamily and friends, wonderful diningexperiences, pursuit of hobbies, cruisingand travel. We especially look forward toin-depth travels to destinations in ourbeautiful United States.”n Richard W. Peters, MD ’69, aretired pathologist, is an advanced mastergardener with a passion for dahlias andshows them throughout the Midwest.He is first vice president of the AmericanDahlia Society, president of the MidwestDahlia Conference, and president of theGrand Valley Dahlia Society.n Thomas J. Sherry, MD ’69, retiredfrom neonatology at Kaiser PermanenteWoodland Hills in December 2008.n Richard W. Terry, MD ’69, practicesinterventional cardiology full time in theOakland-East Bay area as part of a 22-person group covering Alameda and ContraCosta counties. He has been a Boy Scoutleader for more than 25 years leading highadventure treks: hiking/camping, canoeing,whitewater rafting and cycling.n Gordon R. Tobin, MD ’69, remainsfull time in plastic surgery at the Universityof Louisville. He writes, “Our clinicalteam has now done the only five handtransplants in the U.S., and we arepioneering new transplant applications inthe face and other new anatomic sites.”n Philip D. Walson, MD ’69, writes,“I am a remarried widower living full timein Europe with my wife, Sybill. We spendmost of our time in Hanover, Germany,or in Montespertoli, Italy. I retired fromCincinnati Children’s Hospital and theUniversity of Cincinnati in August 2008,and teach part time at Georg-August-Universität Göttingen in Germany, andconsult part time.”1970sn Chris Fukui, MD ’74, has worked atHawaii Permanente Medical Group fornearly 30 years. Presently the associatemedical director of quality improvementwith a clinical practice, she will retire atthe end of 2009. She writes, “I am activein the Hawaii Thoracic Society and theAmerican Thoracic Society. We put on agreat pulmonary critical care conferenceon Maui every Presidents Day weekendwith nationally and internationallyrecognized speakers. Please considerattending!”n Jeff Anderson, MD ’79, is in privatepractice in San Jose, Calif., specializing ingeneral orthopedics with a special interestin joint replacement.He and Mary Bethlive in Gilroy andhave threechildren and twograndchildren.He writes, “For thosein the area, come onby and enjoy a sunset and a glass of winewith us sometime.”n Warren S. Browner, MD ’79, is thevice president of academic affairs andscientific director of the California PacificMedical Center Research Institute inSan Francisco.n Martin A. Fogle, MD ’79, writes,“I stumbled on a perfect job in 2007 inFall River, Mass., to practice vascularsurgery in a medium-sized, veryappreciative and supportive, non-traumahospital. Kathy is a nurse practitioner.Dice, the cat, is like most other offspringof physicians – he has no intention ofbecoming a veterinarian.”n Brion Pearson, MD ’79, is thedirector of the hospitalist service, apracticing hospitalist and vice presidentfor medical affairs at Sutter Delta MedicalCenter in Antioch, Calif.n Elizabeth K. Tam, MD ’79, is chairof the Department of Medicine, Universityof Hawaii John A. Burns School ofMedicine. She and her husband, MarkGrattan, MD, ’79, have two children,Ryan and Lauren. Mark is in private practice,and serves as surgical director of theStraub Heart Center and vice chief of staffof Straub Clinic and Hospital in Honolulu.18 | fall 2009

1980sn Ronald Tamaru, MD ’82, writes, “Ourson Jeff graduated from high school andis off to Mike Nagata’s, MD ’82, almamater: USC. Good thing I went to medschool. I can almost afford the tuition!”n Calvin T. Eng, MD ’84, writes, “Sincefinishing residency in ophthalmology at theJules Stein Eye Institute-UCLA, I’ve beenin private practice in the San GabrielValley/Los Angeles area. Janice Low,MD ’84, and I celebrated our 21stanniversary this year. We travel a couple oftimes a year and look forward to the endof paying tuition for our four kids.”n Renée M. Howard, MD ’84, & DavidErle, MD ’84, have been married for23 years and have two children in college.Renée is in private pediatric and adultdermatology practice in San Rafael, Calif.,and holds a part-time academic position at<strong>UCSF</strong>. David conducts research in asthmaand lung disease at the Lung BiologyCenter at <strong>UCSF</strong>’s Mission Bay campusand does two months of clinical workeach year at SFGH.n Krista C. Farey, MD ’84, practicesfamily medicine in the county clinic inRichmond, Calif., including obstetrics,teaching and medical staff leadership.She and her husband, Vishu Lingappa,live in San Francisco with their twoteenage daughters (above).n David A. Friscia, MD ’84, practiceswith a largeorthopedicgroup inRancho Mirage,Calif., w<strong>here</strong> heis president ofthe DesertOrthopedicCenter group.Additionally, heis president-elect of the Riverside CountyMedical Association and an assistantclinical professor of orthopedic surgery atUSC. He and his wife, Karen, have twosons, Matthew (15) and Gregory (13).n David G. Hwang, MD ’84, writes,“Academic ophthalmology has been afortunate career choice for me, one wellsuitedto my temperament and interests.(Apparently Dan Schwartz, MD ’84, andTodd Margolis, MD ’84, also feel thesame way). Having spent all of the past 29years at <strong>UCSF</strong> (with the exception of aone-year fellowship stint in Los Angeles), I’mone of those who never left the mother ship.But it’s more than just inertia that has keptme <strong>here</strong> – this is truly a great place to work,mostly because of the outstanding peoplewho call <strong>UCSF</strong> home. I very much enjoy mycareer, which is focused on clinical research,teaching and practice in the sub-specialty ofcorneal and refractive surgery.”n Debra F. Vilinsky, MD ’84, &Michael Sopher, MD ’84 (above), havebeen married for 25 years and have twochildren, Marcus (21) and Ariana (17).Michael practices cardiac anesthesia atUCLA and co-coordinates the medicalschool second-year cardiac, respiratoryand renal curriculum block. Debbiepractices part time as an adult psychiatristand psychoanalyst, teaches ethics topsychoanalytic trainees, teaches secondandthird-year UCLA medical students inthe doctoring program, and mentorspsychoanalytic and psychiatric trainees.Additionally, she volunteers at two understaffed,underfunded public high schools,helping students prepare college, financialaid and scholarship applications.n Virginia C. Brack, MD ’89, worksat Mt. Ascutney Hospital in Windsor, Vt.n Ben Man-Fai Chue, MD ’89,practiced medical oncology, specializingin hard-to-treat cancers such as pancreaticadenocartinomas and published resultsfor treating pancreatic cancer (GI ASCO,2009, abstracts #175 & #177).n Sheri S. Dickstein, MD ’89, spendsthree days per week at the CSU ChannelIslands Student Health Center and ahalf day eachweek attendingat the VenturaFamily PracticeResidencyprogram.She writes,“I married IraSilverman, an ob-gyn, who is a full-timefaculty member for the Ventura FamilyPractice residency. One of his partners isour classmate Fred Kelley, MD ’89.Fred went back for a second residency inob-gyn after working several years as afamily doc in rural South Carolina.”n Cynthia J. (MD ’89) & Byron (PhD’92, MD ’94) Hann, celebrated 20 yearsof marriage in April. Byron is a scientist atthe <strong>UCSF</strong> Helen Diller Family ComprehensiveCancer Center w<strong>here</strong> he runs a mousehospital. Cindy works 80 percent time at aprivate pediatric practice in San Ramon,Calif. Their oldest daughter, Erica, attendsthe University of Puget Sound. Theiryoungest, Ellen, is in 7th grade and enjoyshorseback riding and soccer.n Eve Askanas Kerr, MD ’89, focusesher research on assessing and improvingquality of care for patients with chronicconditions at the Ann Arbor VA MedicalCenter for Clinical Management Researchand sees patients one-half day per week.She and Robb have two daughters,Jessica (14) and Rachel (10).1990sn Lee R. Atkinson-McEvoy, MD ’94,is in the <strong>UCSF</strong> Department of Pediatrics asthe director of the Parnassus Primary CareClinic and the associate director of thepediatric residency program. She and herhusband live in Oakland and have threechildren, Amara (5), Mason (3) and Noah (1).n Chinazo O. Cunningham, MD ’94,writes, “After moving unexpectedly to NewYork 14 years ago, I am officially a happyNew Yorker. I live just outside of NYC withEverett (married for 17 years) and ourthree daughters (ages 12, 10 and 8). I ama general internist spending most of mytime conducting research and developingprograms aimed at improving access tocare for marginalized populations at Albertmedical alumni magazine | 19

Class Notes 1990s | continuedEinstein College of Medicine andMontefiore Medical Center in the Bronx.”n Tiffany S. Glasgow, MD ’94, is onthe pediatric faculty at the University ofUtah. She writes, “Rob and I celebratedour 15th anniversary this year. We havethree incredibly busy children, Matthew(12), Sommer (10), and Garrett (6). Wespend most of our free time watching ourkids participate in their various sports.”n Sondra S. Vazirani, MD ’94, isa hospitalist at theWest LA VA, and runs thePreoperative Clinic andMedicine Consult Service.She works with residents inthe combined CedarsSinai-VA internal medicineresidency, and is an associate clinicalprofessor at UCLA.n Charles V. Wang, MD ’94, is inprivate practice at the Palo AltoFoundation Medical Group. He writes,“The group keeps an entertaining blend ofslick, private and demanding academic(Stanford) cases. Recently, I’ve beenhelping with a rollout of an electronicmedical system for Sutter Health Hospitals.Every so often, t<strong>here</strong>’s time to volunteerin a Third World country – you definitelyget way more than you put in.”n Jacquelyn Chang, MD ’95, is inprivate practice in psychotherapy withmedications and supervises in theSan Mateo County psychiatric residencytrainingprogram.n Dineen Greer, MD ’95, is on facultyat the Sutter Health Family MedicineResidency Program in Sacramento, w<strong>here</strong>she greatly enjoys training future familymedicine physicians. She and herhusband, Darrin, have one son (6) and twodaughters (3) who keep them quite busy.n Scott Anderson, MD ’98, wasappointed clinical professor, Division ofRheumatology, Allergy and ClinicalImmunology at UC Davis in January.He writes, “I enjoy life in the Napa Valleyarea with my wife, Camille, a former <strong>UCSF</strong>anesthesiology technician, who runs ourboard-and-care facility for the elderly,the Renaissance Guest Home. Our kidsLuke (5) and Sophia (8) both swim for theSolano Aquatic Sea Otters team.”n Tessa B. Collins, MD ’99, is apartner in private practice at East BayAnesthesiology Medical Group that servesAlta Bates Summit Medical Center. Sheand husband, Adam Collins, MD, havetwo sons, Drew (4) and Cameron (3).n Diana V. Do, MD ’99, is an assistantprofessor of ophthalmology and assistanthead of the retina fellowship committee atthe Wilmer Eye Institute (Department ofOphthalmology), Johns Hopkins UniversitySchool of Medicine. She and herhusband (above) have traveled extensivelythroughout the world but still enjoycoming back to San Francisco each year.She encourages her former classmatesto email her at ddo@jhmi.edu.n Ritu Patel, MD ’99 (below), writes,“My job as a pediatric hospitalist at KaiserOakland is a role in which I put on threedifferent hats depending on the day.When I am ward attending, I have theprivilege of teaching residents and medicalstudents. When I take call in the PICU, Icare for children who have just had majorneurosurgery including removal of braintumors. As a transport physician, Istabilize and transport acutely ill childrento an ICU center.”n Julie L. Vails, MD ’99, is in soloprivate practice in Elk Grove, Calif., doingfamily medicine with pediatrics andobstetrics. She writes, “Currently I havea very full personal life parenting eightchildren with my husband, Tripp.”2000sn Joyce Leary, MD ’04, finished herinternal medicine residency and chief yearat UC Davis and continued on t<strong>here</strong> as anendocrinology fellow. With swimming asher primary hobby, she completed a swimfrom Alcatraz in August.n Alejandrina Rincon, MD ’04,finished her ob-gyn residency at UC Irvine,moved back to the Bay Area with herhusband, Andy, and works at KaiserPermanente Santa Clara Medical Center.Send usyour class notetoday...> Online: www.ucsfalumni.org> Email: alumni@support.ucsf.edu> Mail: <strong>Alumni</strong> Services, <strong>UCSF</strong> Box 0248,San Francisco, CA 94143-0248IN MEMORIAMALUMNICarr E. Bentel, MD ’29Robert C. Combs, MD ’39John S. Miller, MD ’43Robert H. Palmer, MD ’43Robert S. Rocke, MD ’43Ralph O. Wallerstein, MD ’45Dean L. Mawdsley, MD ’50Laurance V. Foye Jr., MD ’52Kenneth H. Root, MD ’53Yasin Balbaky, MD ’61Carolyn K. Montgomery, MD ’64John H. Austin, MD ’70Cynthia J. Kirsten, MD ’79faculty, housestaffGeorge C. KaplanJay V. LeopoldRobert D. Roller IIISteven E. RossWilliam H. ThomasHerschel S. Zackheim20 | fall 2009

<strong>UCSF</strong> is grateful to the many alumniwho have given back to the School of Medicine ……including those who have chosen to do sothrough their estate plans.H. James Cornelius, MD ’62Jim and his wife, Mimi, haveestablished a charitable giftannuity in support of the <strong>UCSF</strong>School of Medicine Class of1962 Scholarship Fund.“I’m concerned aboutthe high cost of medicalschool tuition, so it’stime for me to pay back.A charitable gift annuityprovides income for usfor life and a gift to theUniversity later on. Itmakes financial sensefor us to support theUniversity in this way.”Susan Detweiler, MD ’71Susan has includeda bequest to the <strong>UCSF</strong>School of Medicinein her will.“I received a tremendouslyvaluableeducation at <strong>UCSF</strong>.Without it I wouldn’tbe the person I amtoday. In choosing tosupport the Universitythrough a bequest, Iam able to give agreat deal more thanI could in my lifetime.”Peter Packard, MD ’48Peter and his wife, Mary Jane, havecreated a charitable remainder trustthat will fund the Peter and MaryJane Packard Endowment in supportof the Academy of Medical Educators.“The doctor-patientrelationship is critical topatient outcome. I want toensure with our gift to<strong>UCSF</strong> that future medicalstudents are taught both theimportance of a healthydoctor-patient relationshipand the skills and techniquesto create one.”For more information on making a bequest or life-income giftor to receive a copy of our “Leaving a Legacy” brochure,please contact the Office of Gift & Endowment Planning at415/476-1475 or email giftplanning@support.ucsf.edu.

0906<strong>UCSF</strong> School of MedicineMedical <strong>Alumni</strong> Association<strong>UCSF</strong> Box 0248San Francisco, CA 94143-0248Non-profit OrganizationU.S. PostagePAIDSacramento, CAPermit No. 333ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTEDSave the dateCelebrating at the 2009 Reunion, from left: Herbert Konkoff, MD ’59, and Karen Hays; Mark Luoto, MD ’79, Valerie Luoto,JaNahn Scalapino, MD ’79; Donald Webb, MD ’59; the Class of 1984 (See story on page 12.)<strong>UCSF</strong> School of Medicine Class ReunionsMay 7-8, 2010Plus 4-hour CME courseFor more information about theCME course and Reunion details,email maa@support.ucsf.edu.