Volume 8, Issue 1 Fall 2010 — Special Edition - Binghamton ...

Volume 8, Issue 1 Fall 2010 — Special Edition - Binghamton ...

Volume 8, Issue 1 Fall 2010 — Special Edition - Binghamton ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

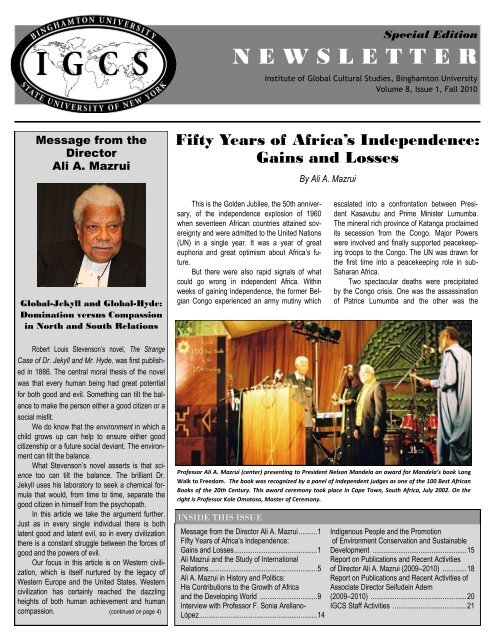

2 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>… Fifty Years of Africa’s Independence: Gains and LossesInstitute of GlobalCultural StudiesDIRECTORAli A. MazruiASSOCIATE DIRECTORSeifudein AdemRESEARCH ASSISTANT PROFESSORF. Sonia Arellano–LópezRESEARCH ASSOCIATEPatrick DikirrRESEARCH AFFILIATEAmadu Jacky KabaGRADUATE ASSISTANTSRamzi BadranAnand JahagirdarPauravi PatilADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANTRavenna NarizzanoSECRETARYJennifer WinansSECRETARYBarbara Tiernoseemingly accidental air crash near Ndola in Zambiawhich killed the Secretary-General of the UN,Dag Hammarskjöld.The Congo crisis of 1960–1965 also initiatedAfrica‘s involvement in the Cold War. The newlyindependent African countries were courted bymembers of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization(capitalist) on one side, and on the other, membersof the Warsaw Pact (communist). For the followingthree decades the Soviet Union and itsallies, along with the People‘s Republic of China,had a flirtation with leftwing African governments.These were diplomatic flirtations between states.In terms of command of roles in the world body,the Cold War was the golden age of Third Worldinfluence and leverage in world institutions.But there was also Africa‘s ideological experimentationduring this period. From the 1960s tothe 1980s Africa had a love affair with differentversions of socialism.But almost none of the African countriesruled by Great Britain went the whole hog to Marxism-Leninism.On the other hand, all the countriespreviously ruled by Portugal started their earlyyears of sovereignty with Marxism-Leninism. Countriespreviously ruled by France had some governmentsflirting with Marx and Lenin while otherswere either liberal or socialist only rhetorically. Formore than fifty years the UN echoed the concernsof Marxist-Leninist countries.The Communist world‘s flirtation with Africain foreign policy had longer term consequencesthan Africa‘s own flirtation ideologically with socialism.The members of the Warsaw Pact wereprepared to arm African liberation fighters — andspeeded up decolonization especially in SouthernAfrica and in the Portuguese colonies. Castro‘sCuba even sent troops to engage with South Africantroops and speed up Namibia‘s liberation, aswell as defend newly independent Angola. TheUN pursued the diplomatic path of the struggle forNamibia‘s independence.Without the military help of socialist countriesabroad the liberation of the Portuguese coloniesand Southern Africa could have been delayed bya generation. Socialist governments abroad had agreater impact on Africa than socialist governmentsat home.The big exception was Julius Nyerere‘s socialistgovernment in Tanzania. The socialist partof Nyerere‘s efforts was heroic, but not spectacularlysuccessful. But history will judge Nyereremuch more as a nation-builder than as a builder ofa socialist state. His language policy (Swahilization)and his efforts to open up the rural countrysidewere major contributions to the building ofTanzania‘s sense of nationhood.Tanzania‘s independence was in 1961 ratherthan 1960. The independence explosion of thatyear of 1960 included the largest Anglophone countryin population, Nigeria, and the largest Francophonecountry, what is now the Democratic Republicof the Congo.The flowering sovereignty in 1960 also includedcountries which were neither Anglophonenor Francophone — such as Somalia. There wererich countries in 1960 as well as poor ones, likeNiger.The most dazzling statesmen of the periodincluded not only Nyerere, but also KwameNEWSLETTER EDITORIAL TEAMF. Sonia Arellano–LópezRavenna NarizzanoPauravi PatilJennifer Winans<strong>Binghamton</strong> UniversityPO Box 6000 LNG-100<strong>Binghamton</strong>, New York 13905-6000Tel: 607-777-4494Fax: 607-777-2642Web: igcs.binghamton.eduEmail: igcs@binghamton.eduArchbishop Desmond Tutu in consultation with Professor Kole Omotoso, Master of Ceremony (middle, seated)Dr. Ali A. Mazrui on the right. The event was a celebration of Africa’s best 100 books of the 20th century, July2002.

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 3Nkrumah of Ghana, Felix Houphouët-Boigny ofthe Ivory Coast, Leopold Senghor of Senegal,Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, and Gamal AbdelNasser of Egypt.But more dazzling than Nigeria‘s politicianswere Nigeria‘s leaders in culture and the arts.Chinua Achebe became by far Africa‘s bestsellingnovelist. Wole Soyinka was making hisway toward becoming Africa‘s first Nobel PrizeLaureate in Literature. Senegal, Nigeria, and laterDar es Salaam and Kampala hosted major Pan-African festivals of Arts and Culture.Other Nobel Laureates in Literature includedNadine Gordimer of South Africa, Najuib Mahfuzof Egypt and J. M. Coetzee also of South Africa.Africa has been richer in Nobel Peace Laureates.These have been: Albert Luthuli, ArchbishopTutu, Nelson Mandela, F. W. de Klerk,Anwar Sadat, Wangari Maathai (first womanAfrican Peace Laureate), Kofi Annan, andMohammed El-Baradei.Bad news in Africa in this period includedthe Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa in 1960,Nigeria‘s civil war 1967–1970, and the multipleconflicts of the Sudan in the South and in theWest. There was also the horrendous genocidalcollapse in Rwanda in 1994. The Global Mr.Hyde had exploded into genocide in Rwanda inthat year. But in the same year of 1994 theGlobal Dr. Jekyll ended political apartheid inSouth Africa.As the 20th century was coming to an endone happy development was the end of politicalapartheid in South Africa, but not the end of economicapartheid as yet.The black man in South Africa acquired thepolitical crown, but the white man successfullyretained the economic jewels.Gender achievements of this half century includednot only Kenya‘s Wangari Maathai, as thefirst black woman to win the Nobel Prize forPeace, but also Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in Liberiaas the first elected African woman head of state.The most spectacular African Diaspora eventthis decade was Barack Obama — this son of aKenyan father was successfully elected Presidentof the United States. Barack Obama hasbecome the most powerful black person in thehistory of civilization. More powerful than RamsesII of Egypt, Menelik II of Ethiopia, and Shaka Zuluof South Africa. Obama is the most powerful sonof a Muslim father since the dynasty of Harun-al-Rashid of the Abbasid over ten centuries ago.But is Obama afraid of his own power? Is he aDr. Jekyll afraid of becoming Mr. Hyde?In addition to heroes there have been martyrs.Early martyrs of Africa‘s independence includedthe assassination of Patrice Lumumba inJanuary 1961 and of Sylvanus Olympio in 1963.The UN puts its troops in harm‘s way in conflictsituations. The UN also lost its Secretary-Generalin Africa‘s cause, Dag Hammarskjold in1961. Was the air crash near Ndola an accident(on a plane called Albertina), or was it sabotagedby a nefarious global Mr. Hyde?There was even a suspicion that DagHammarskjold wanted to die in Africa‘s cause,―Do I fear a compulsion in me to be so destroyed?Tired and lonely. So tired the heart aches,‖Hammarskjold lamented in writing.IGCS Director Ali A. Mazrui being interviewedby African journalists in 2002.Dag Hammarskjold was another supremeDr. Jekyll afraid of turning into a Mr. Hyde.A tale of two history makers: Salim AhmedSalim and Adebayo AdedejiIn the earlier years of Tanzania‘s independenceSalim Ahmed Salim became the secondmost important architect of Tanzania‘s post colonialforeign policy — after Julius K. Nyerere himself.In those initial decades of independenceSalim Ahmed Salim served as the most seniorMinister of Foreign Affairs and as the PermanentRepresentative of Tanzania at the UN. AmongAfrican ambassadors he often led the way onimportant issues, including the struggle to get thePeople‘s Republic of China admitted to the UNas the proper occupant of the fifth PermanentSeat in the Security Council instead of the fig leafof Taiwan.It is widely believed that Salim AhmedSalim‘s visible role in the admission of CommunistChina to the UN cost Salim Ahmed Salim thechance to become the first African Secretary-General of the UN instead of Boutros Boutros-Ghali a few years later.The US Administrations of both LyndonJohnson and Richard Nixon, in reality misunderstoodSalim Ahmed Salim‘s role in the UN — andbecame hostile to him.Salim Ahmed Salim himself has denied thathe danced in ecstasy in the corridors of the UNwhen the People‘s Republic of China won thevote of admission. But he did play a dignified rolein the politics of supporting China‘s assumptionof proper role as a major power in the SecurityCouncil.Subsequently Salim Ahmed Salim was electedrepeatedly as Secretary-General of the Organizationof African Unity (O.A.U.) — becoming thelongest serving Secretary-General of the O.A.U.He helped to move the O.A.U. towards amore active role in managing African conflicts —including civil wars.He also helped to sharpen the O.A.U.‘s rolein the struggle against apartheid in South Africaand the effort to liberate Namibia.With the help of the late Chief M. K. O.Abiola of Nigeria and President Ibrahim Babangida,Salim Ahmed Salim helped create the Committeeof Eminent Persons of the O.A.U. with amission to demand reparations for hundreds ofyears of African enslavement, colonization andracial exploitation. I was sworn in before Africa‘spresidents as a member of the Reparations Committeeof Eminent Persons.The debate on reparations is still alive andwell in the United States and the United Kingdom.The controversy was recently reignited by ProfessorHenry Louis Gates Jr., of Harvard in anarticle he published in the New York Times. ProfessorGates made the case that the election ofBarack Obama to the U.S. Presidency had madethe reparations debate moot.Salim Ahmed Salim is great partly becauseof what he achieved domestically as Prime Ministeras well as Foreign Minister of Tanzania, butalso as O.A.U. Secretary-General in the finalyears of the 20th century.History will also note that Salim AhmedSalim nearly became the first African Secretary-General of the UN. He also nearly became Presidentof the United Republic of Tanzania — butfor the ethnic politics of Zanzibar.But he has lived to maintain the legacy ofJulius K. Nyerere in his continuing internationalactivities and as leader of the Julius K. NyerereFoundation in Dar es Salaam.We salute Salim Ahmed Salim not only as adistinguished Tanzanian — but also as a majorarchitect of Pan Africanism in the first fifty yearsof postcolonial history.Adebayo AdedejiOne of the two or three most distinguishedpolitical economists produced by postcolonial Africahas been Adebayo Adedeji.As Executive Secretary (or Secretary-General)of the UN Economic Commission for Africa,Dr. Adedeji became a major role model of the left

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 5Ali Mazrui and the Study of International RelationsBy Seifudein AdemThe coming of age of Ali Mazrui as a scholarcoincided with the birth of postcolonial Africa inthe 1960s. By virtue of his field of training and hispolitical instincts, Mazrui displayed great readinessto rise to the intellectual challenges of thetime. Mazrui first made a name for himself bypublishing, ―On the Concept of ‗We are all Africans‘‖in the American Political Science Reviewin 1963. As it turned out, this was to be an importantlandmark in Mazrui‘s own intellectualdevelopment.The article was one of the first major writingsin that journal about postcolonial Africa writtenby a postcolonial African scholar. Americanpolitical scientist Herbert J. Spiro noted: ―Mazrui‘sarticle identified him as a perceptive and originalstudent of African political thought.‖ 1 By publishingin the journal, Mazrui declared that he wasready to engage intellectually one of the mostvibrant communities of scholars in his field. It wasalso significant that the article should be publishedin an influential journal of political sciencebased in an increasingly influential country in theworld — the United States. Another significanceof the article had to do less with where it waspublished than with what it was about: identityformation in the postcolonial African context. Itmay be recalled that theorizing about culture andidentity was less fashionable in mainstream Americanpolitical science in those days.The mainstream discipline was then relativelymore open not only to other issues but alsoto different perspectives. But why was this so? Inthe 1960s and 1970s the ―Third World‖ was drawingspecial attention in the West due partly to itsrelevance to the strategic interests of the superpowers.This was when the two superpowers, theUnited States and the Soviet Union, competedfor friendship with the newly independent Africanstates, when, for instance, Kwame Nkrumahcould go to Washington and say: ―… I was appealingto the democracies of Britain and theUnited States for their assistance in the firstplace, but that if this should not be forthcoming, Iwould be forced to turn elsewhere.‖ 2 The ThirdWorld also drew attention in this period, becauseof the relatively unified Southern voice regardinginternational economic and political issues. MainstreamInternational Relations (IR), too, sought toreflect the prevailing historical trend, with prominentscholars engaging issues of concern to theThird World. In fact, it was in the context of debatingthe issue of international justice versusinternational order with Mazrui that Hedley Bullrecognized Mazrui as a formidable intellectualadversary. 3 Just after he published his influentialThe Anarchical Society, Professor Bull had this toDr. Seifudein Adem at an International Conference inBeijing, China, November <strong>2010</strong>.say: ―Ali Mazrui is not only the most distinguishedwriter to have emerged from independent BlackAfrica, and the most penetrating and discriminatingexpositor of the ideology of the Third World,he is also a most illuminating interpreter of thedrift of world politics.‖ Bull added, ―[t]he issuesthat interest [Mazrui], the audience to whom headdresses himself, even the values he embraces,are not simply black or African or ThirdWorld, but global.‖ 4 Although Mazrui‘s focus wasboth Third World and global, his perspective was,and has continued to be, bottom-up. It was thispostcolonial ―ideology‖ which Bull had in mindwhen he described Mazrui as ―the expositor ofthe ideology of the Third World.‖The mainstream discipline of which HedleyBull was a part picked up Mazrui also becausescholars were then more eager to better understandinternational relations in all its complexities,including by explaining or evaluating what DonaldPuchala recently described as: ―… the significanceof the embittered tone, the complex motivations,the mythological underpinnings, or thehistorical dynamics of North-South relations.‖ 5The relationship between Bull and Mazrui was,however, not a one-way street. If J. D. B. Miller‘saccount is to be relied upon, and there is no reasonwhy not, Mazrui, too, was a positive influenceon Bull. 6 Miller has recorded: ―Hedley Bull‘scontact with stimulating people like Ali Mazrui,caused him to ask questions about the directionin which the Third World might be heading.Ultimately, however, it was perhaps thesame bottom-up perspective about the ThirdWorld which, to adapt a phrase from Philip Darby,not only articulates Third World dissatisfactionwith its lot but also attempts to change it, thatmarginalized Mazrui in the 1970s and 1980s IR. 7The external manifestations of how Mazrui‘srelationship with Bull eventually soured perhapssymbolized the then emerging ―paradigm shift‖ inthe mainstream discipline and the nature of itsconsequences. As Mazrui reminisced recently―Hedley Bull thought that I carried my anti-imperialismtoo far at a conference in Britain, whichaddressed international issues in connection withAmerican hostages held in revolutionary Iran inthe late 1970s. In my speech I argued that it wasa change that Americans were hostages. Most ofthe time the United States held much of the worldhostage to what Americans regarded as theirnational interest. I spoke with passion and at onestage I stopped speaking in a struggle to holdback my tears and prevent a breakdown. Afterquestions and answers Hedley Bull came to thefront and said to me with a twinkle in his eye —you are quite mad!‖ 8In the late 1970s and 1980s a general consensuswas emerging among neo-realists andneo-liberals that the Third World required a differentset of theories. Mainstream IR was reassertingits identity as ―American social science,‖ itwas focusing almost exclusively on ―the study ofgreat power behavior.‖ 9 The discipline effectivelyclosed itself off to Mazrui‘s concerns. This wascertainly not the kind of IR Mazrui had in mindwhen he wrote: ―I experienced international relationsas a person before I studied it professionally.‖10 With the study of international relationsthus ―provincialized,‖ it was less surprising thatthe stars of ―Third World‖ intellectuals like Mazruishould begin to dim in the discipline. 11There is another reason why Mazrui wasdropped by or became more obscure in the mainstreamdiscipline. When Mazrui later critiqued orchallenged some of the core assumptions of IRtheory, he rarely deployed familiar ―theoretical‖concepts. The relevance of Mazrui‘s contributionsin this period to the theoretical debates are thereforeinvisible unless one laboriously sifts throughhis sizable intellectual outputs to distil a theoryout of his historical analyses.The 1970s and 1980s also witnessed thegradual marginalization of the ―classical‖ method.Fact /value dichotomy became the order ofthe day, placing positivism on a solid ground asthe dominant method of research in IR. As aconsequence of this, Mazrui became the methodological―Other‖ in the eyes of mainstreampolitical scientists, who were in Mazrui‘s ownwords, ―… the different shades of behavioralistsin the Western world who believe that politicalscience ought not to include normative and valuepreoccupations.‖ 12 But Mazrui refused to change

6 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>… Ali Mazrui and the Study of International Relationshis methodological approach even as he keptrelative distance from the theoretical exchangeswhich characterized this period. Mazrui was conspicuouslyabsent from the so-called ―inter-paradigm‖debates of the 1980s; apparently he choseto forget the mainstream discourse, by whom hewas also seemingly forgotten.While the values Mazrui had embraced andthe issues he had prioritized did not endear himto mainstream political scientists in North America,it was therefore the method he stubbornlyclung to, which made him the ultimate ―Other.‖Mazrui‘s ―methodological shortcomings‖ were indeedapparent even in the mid-seventies althoughthe discipline seemed more willing totolerate it. 13 In the 1980s the level of tolerance for―methodological shortcomings‖ had substantiallydecreased in the mainstream IR.Less preoccupied as he was with ―metatheoretical―issues, Mazrui has thus contributedrelatively little to theory of international relationsdirectly. Maximum preoccupation with meta-theoriesis likely, in Mazrui‘s view, to make the relevanceof one theory or method loom large. It wasthus also a cautionary step for an eclectic scholarsuch as Mazrui not to dwell on questions likewhat social theories are, how they should beformulated, and how they should be tested.Mazrui‘s ―problem-driven‖ approach of the tripleheritage which he formulated for exploring theAfrican condition is consistent with such methodologicalcommitment.The paucity of Mazrui‘s theoretical contributionhad therefore something to do with his positionon ―theory.‖ The very notion of an all-encompassingtheory is anathema to him. To theextent we can define Mazrui in theoretical terms;it is that he is anti-behavioralist. In Political Scienceand Political Futurology, one of a handful ofhis writings about theoretical issues, his antibehavioraliststance becomes crystal clear. Forinstance, he observes: ―only a thin dividing lineseparates scientific prediction from fortune telling‖14 Was Mazrui referring here to the ―metaphysicalcommitment‖ of science? We do notknow the answer to that for sure since he did notdevelop the notion more systematically as hesteadily drifted away from theory altogether.In line with his approach described above,Mazrui is generally unconcerned about the lackof consistency among his propositions vis-à-vismajor tenets of theoretical traditions in IR. He isabhorrent, for example, to the amoral fabric ofrealist theory. On one occasion, Mazrui describedMachiavelli as ―the first great rationalizer ofhypocrisy and false pretenses as a cornerstoneof high policy in diplomacy and politics.‖ 15 ButMazrui also shares some of the basic propositionsof realism such as the idea that nuclear proliferationis not necessarily inimical to global security.16 It must be noted, however, that Mazrui‘sargument about nuclear weapons is based onmoral calculus rather than on the logic of deterrence.Mazrui is for total nuclear disarmament,but he is also against what he had called ―nuclearapartheid.‖ Mazrui‘s pro-nuclear proliferation argumentwas premised on the assumption that ―adose of the disease becomes part of the necessarycure.‖ 17 As he elaborated: ―Some degree ofproliferation may shock the five principal nuclearpowers out of their complacency.‖ 18Mazrui has also advanced arguments whichare in tune with neoliberal institutionalism. In fact,it can be argued that Mazrui‘s scholarship showsbasic institutionalist impulse, particularly as it wasarticulated more fully in his most ambitious book,World Federation of Cultures. 19However, Mazrui parts company with bothrealism and neoliberalism in important ways suchas in his view that cultural groups, flexibly defined,constitute the main units of analysis ofworld politics and that both hierarchy and anarchyco-exist in and define contemporary internationalsystems. In Mazrui‘s framework, thestate also ceases to be the primary and unitaryactor in world politics. For Mazrui nothing is furtherfrom the truth than, for instance, the suggestionthat postcolonial African states are ―likeunits.‖Mazrui‘s framework does not privilege thestate which is for him just one of multiple playersin world politics. Depending on the issue, indeed,a tribe could be a more significant unit of analysisin his framework than a nation-state. Mazrui hasargued: ―African intellectuals have spent a lot ofenergy rejecting the concept of ‗tribe‘ for Africa.Why? Mainly because African intellectuals haveknown that most Europeans despised ‗tribes.‘ Europeanshave also often despised the black skin.Should we join them in the same prejudice?‖ 20However, Mazrui does not limit the usage of theterm tribe to Africa and other developing regions.For him, ―tribalism can as easily wear a whiteface as a black one.‖ In another sense, Mazruihad also applied the concept of ―macrotribalization‖to the European ―stride for regionalintegration,‖ arguing that ―pan-European identityis reasserting itself on a scale greater than theHoly Roman Empire.‖ 22In general it is impossible to pigeonholeMazrui in theoretical terms, a fact which did notnecessarily augur well for his place in the mainstreamdiscipline, especially as the rule of thegame in the North American IR became, in thewords of James Der Derian: ―without label, a boxor a school, one does not exist.‖ 23 But with hisemphasis on deconstructing Euro-centrism, withhis deep interest in the study of languages andtheir role in the ―construction of subjects,‖ with hisDr. Seifudein Adem (second from the left in front) with participants of “Africa in Contemporary InternationalRelations” conference, Grand Valley State University, Michigan, September 2009.special attention to intersubjectively sharedideas, norms and values, with his longstandingfascination about the issues of culture and identityformation, and with his preference for transactionalmethodology, including the reliance onsemi-autobiography, Mazrui‘s scholarship rhymesmore naturally with (post-positivist) social constructivismthan any other ―-ism‖ in the mainstreamdiscipline. (continued on page 8)

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 7(continued from page 4). . . Message from the DirectorThe Malignant North:Global Mr. HydeThe Benevolent North:Global Dr. JekyllIGCS Director Ali A. Mazrui, December <strong>2010</strong>regarded the nuclear arrogance of the West asinseparable from its much older politics of racism.One potential organizing principle isNkrumah‘s “Two swords of Damocles hangingover Africa,” — racism and nuclear power inhostile hands. I believe that is a defensibleparaphrasing of Nkrumah‘s thesis. One possiblechronological transition is therefore fromFrench Sahara Tests in early 1960s to thenuclearization of apartheid — the latter beinga fusion of the two swords of Damocles.Nkrumah‘s statement should ideally be anauthor‘s first quote of a chapter about Africaunder siege.There was also a fusion of race and nuclearconcerns in France‘s choice of sites fortesting in the 1960s. France‘s insistence onchoosing colonial sites had surely included aracist motif.On the other hand, France‘s nuclear desecrationof African soil seemed to bridge theracial divide between Arab Africa and BlackAfrica. Black Africa‘s outrage at French nucleartests was an implicit reaffirmation of theAfricanity of Algeria, where France was testing.In this respect, Afro-Arab relations havein part been a tale of two Deserts — the Saharaand the Sinai. The Sahara is sometimesin danger of dividing Black Africa from ArabAfrica; the Sinai has sometimes linked ArabAfrica to Asia.1. White capitalism and the ideology of greed:mother of liberal democracy and mother of imperialism.2. White technology and the corrupting tendencyof power.3. White nationalism, the nation-state and thetransition to racism.4. White secularism and the search for alternativeforms of solidarity (e.g., racial solidarity).5. White mobility and the encounters with othercultures.6. The nation-state: mother of patriotism andsacrifice and mother of war.But when either the Sinai or the Sahara isdesecrated by outsiders, they have shown acapacity to bring Arab Africa and Black Africatogether. Hence the Pan African unifying consequencesof (a) French tests in the Sahara(b) Israeli occupation of the Sinai. Just asBlack recognition of Algeria‘s Africanity wasaided by French desecration of the Sahara so,Black recognition of Egypt‘s Africanity wasaided by the Israeli occupation of the Sinai.De Gaulle‘s strategy of strengtheningFrance as a nuclear power was partly to compensatefor France‘s decline as an imperialpower. The process of nuclearization was a―power equivalence‖ in a declining Empire —and to compensate for the new imperative ofdecolonization.France as an Imperial power in the oldsense was more likely to clash with the Arabsthan France as an independent nuclearpower. On the contrary, nuclear France couldsell arms to independent Arab States — andeven try to build for Iraq a kind of Arab―Demon Reactor‖ (Premier Begin permitting)!Nkrumah‘s racial sword of Damocleshanging over Africa had itself two versions —the European racism of color and the Zionistracism of culture. The two converged in theTel Aviv/Pretoria Axis. The most controversialaspects of that Zionist /Apartheid axis1. The example of Jesus and service among thepoor and the sick.2. Service as a strategy of conversion: fromclinic to confession, from school to salvation.3. Rise of liberal humanitarianism in the West:Oxfam, Red Cross.4. Rise of liberal democracy; rise of Euro-socialismand other left wing movements: the youngerMarx and idealism.5. Euro-globalism: Discourse on world order andglobal concerns.6. Euro-environmentalism: Planet Earth is One.were: (a) nuclear collaboration between Israeland racist South Africa, (b) collaboration betweenthem on counter-insurgency (so-called―anti-terrorism‖).Another juxtaposition which may be illuminating(alas rather disconcerting) is Israel‘sappeal to Africans as a religious metaphor(―Israelites‖) and Israel‘s potential alienationfrom Afrabia as a scientific and technologicalmodel. A tension between Biblical and NuclearIsrael converged in African perceptions.Here was the contradiction between Jews atthe dawn of Biblical creation and Jews at thedark hour of nuclear destruction.One can explore these ideas to illustratedifferent ways of giving this historical phasetheoretical coherence and Afrocentrism.Further investigation is also neededabout how far African uranium has been importantnot only for South Africa‘s nuclearprogram, but also for French and Israeli programsfrom the 1950s to the 1980s.There may also be a compelling storyabout the Congo‘s nuclear research reactor.How does this relate to the Congo‘s militaryflirtation with Israel and their resumptionof diplomatic relations during the Congoleseera of Mobutu Sese Seko? This part of thestory is for another day.

8 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>… Ali Mazrui and the Study of International Relations(continued from page 6)But Mazrui‘s constructivism has, as indicatedabove, a peculiar strong postcolonial accent. Thatis why I decided to examine in a forthcoming articlethe issues surrounding Mazrui‘s complex intellectualrelationship with postcolonial theory. Why isMazrui (at least) as obscure in postcolonial IR as heis in the mainstream discipline? Why did postcolonialIR scholars not pick up Mazrui as one of theirown? Why has Mazrui‘s scholarship not struck achord with postcolonialism? Where could we findthe answers to these questions — in postcolonialtheory, in postcolonial theorists, in Mazrui‘s scholarship,or somewhere else?Endnotes1. See Patterns of African Development: Five Comparisons,edited by Herbert J. Spiro (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall,1967).2. Kwame Nkrumah, The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah(Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson, 1957).3. Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order inWorld Politics (2nd <strong>Edition</strong>, New York: Columbia UniversityPress, 1977).4. Hedley Bull, Times Literary Supplement, London, December1. (Extracts from Reviews of Writings by Ali A. Mazrui (n.d.,unpublished manuscript), 1978.5. D. Puchala, ―Third World Thinking and Contemporary InternationalRelations,‖ International Relations Theory and theThird World edited by Stephanie G. Neuman (New York: St.Martin‘s Press, 1998), pp. 133–157.6. J. D. B. Miller, ―The Third World‖ in Order and Violence:Hedley Bull and International Relations edited by J. D. B.Miller and R. J. Vincent (New York: Oxford University Press,1990), pp. 65–87.7. Philip Darby, ―Postcolonialism,‖ in At the Edge of InternationalRelations, Postcolonialism, Gender and Dependencyedited by P. Darby (London and New York: Pinter, 1997), pp.11–32.8. Interview with Mazrui, January 29, <strong>2010</strong>.9. S. Hoffman, ―An American Social Science: InternationalRelations,‖ Daedalus 106 (1977), pp. 41–60; K. J. Holsti,―Scholarship in an Era of Anxiety: The Study of InternationalPolitics During the Cold War,‖ in Review of International Studies<strong>Special</strong> issue), 24 (1998), pp. 17– 46; J. Mearsheimer, TheTragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W. W. Norton,2001).10. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Growing Up in a Shrinking World: A PrivateVantage Point,‖ in Journey through World Politics: AutobiographicalReflections of Thirty-four Academic Travelersedited by Joseph Kruzel and James Rosenau. (Lexington: LexingtonBooks, 1989), pp. 469–87.11. Kevin Dunn, ―Introduction: Africa and International RelationsTheory,‖ in Africa’s Challenges to International RelationsTheory edited by K. Dunn and T. M. Shaw (New York: Palgrave,2001), pp. 1–8.12. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Africa, My Conscience and I,‖ Transition 46(4) (1974a), pp. 67–71.13. See for instance John Nellis, ―Review of Cultural Engineeringand Nation Building in East Africa,‖ by Ali A. Mazrui,in The American Political Science Review 68(2) (1974), pp.331–832.14. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Political Science and Political Futurology:Problems of Prediction,‖ Proceedings of the University of EastAfrica Social Science Council Conference, Makerere University,Kampala, Uganda, 1969.15. Ali A. Mazrui, A World Federation of Cultures: An AfricanPerspective, (New York: The Free Press, 1976a).16. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Changing the Guards from Hindus toMuslims: Collective Third World Security from a CulturalPerspective,‖ International Affairs 57(1) (1980a): 1–20.17. Ali. A. Mazrui, op. cit., 1980a.18. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Can Proliferation End the Nuclear Threat?‖Middle East Affairs Journal 4(1– 2) (1978b): 5–11.19. Ali Mazrui, op. cit., 1976a.20. Ali A. Mazrui, ―Ideology and African Political Culture,‖ inExploration in African Political Thought: Identity, CommunityEthics edited by T. Kiros, (New York and London: Routledge,2001b), pp. 97–131.21. Ali. A. Mazrui, op. cit., 2001b.22. Ali A. Mazrui, “Global Apartheid? Race and Religion in theNew World Order,‖ The Gulf War and the New World OrderInternational Relations of the Middle East edited by T. S.Ismael and J. Ismael. (Gainesville: University Press of Florida,1994), pp. 521–535.23. James Der Derian, Critical Practices in InternationalTheory (London and New York: Routledge, 2009).* * *(Excerpt adapted from a forthcoming article scheduled forpublication in 2011.)Dr. Ali A. Mazrui delivering Barbara Ward Distinguished Lecture, at 23rd World Congress of the Society for International Development, andin the presence of the President of Tanzania, His Excellency Benjamin Mkapa, at Karimjee Hall, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, on July 4, 2002.

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 9Ali A. Mazrui in History and Politics:His Contributions to the Growth of Africa and the Developing WorldBy A. B. Assensoh and Yvette M. Alex-Assensoh*The observation of the busy as well as fulfilledlife and times of Professor Ali Al‘amin Mazruihave brought a lot of cogent meaning to our understandingof his well-lived and much-appreciatedlife, all of which go a long way to confirm thelate Morehouse College President BenjaminElijah Mays‘ conclusion in his eulogy of the lateReverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., his formerMorehouse College student, that it is not howlong one lives that matters, but how well andmeaningful that life has been. Dr. Mays, himself adistinguished Phi Beta Kappa scholar was, in hiseulogy, referring to the fact that at Dr. King‘s assassinationon April 4, 1968 in Memphis,Tennessee, the Nobel Peace Prize laureateand Baptist Preacher was only 39years old. Happily, Professor Mazrui has,comparatively, lived a very long and meaningfullife.Toward the foregoing ends and whereone‘s attributes are concerned, we alsoagree that, as we complete our co-authoredessay about 77-year-old Dr. Mazrui,every human being is deemed mortal. Discussingman‘s mortality versus his ambition,we remember Shakespeare‘s prompt conclusionin his published famous play, JuliusCaesar, as he touched on Caesar‘s ambitionthat all of these details evoke universality.Therefore, as we see the graduallyagingphotographs of Professor Mazrui,which makes him a meaningful Mwalimu, inthe true meaning of the accolade, we agree withmany other observers of the Mazuriana miraclethat one day, in the distant future, our belovedTeacher (Mwalimu), Mentor (Nana as Ghana‘sAkan chieftain), and indeed, our dear friendcalled Mazrui may not physically be in our midst.That thought, in itself, appropriately prompts usto enlist what Ghana‘s late British-educated AttorneyJoseph Emmanuel (Joe) Appiah aptlynoted when he utilized for illustration the followingquote from Thomas Moore in his brilliantautobiography, Joe Appiah: The Autobiographyof an African Patriot (1990):When time shall steal our years awayAnd steal our pleasures too,The memory of the past will stayAnd half our joys renew …Professor V. Y. Mudimbe and IGCS Director Ali A. Mazrui, April <strong>2010</strong>.Also, when we take the time to observe the sheerproductivity in teaching as well as the sheer volumeof the published output and distinction of Dr.Mazrui as a scholar, a teacher, a public-cumorganicintellectual, it seems that he did it inrapid succession with the onerous thought thatin the words of Alfred Tennyson, as Ghana‘s latePresident Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972) quotedin his 1957 published memoirs, Ghana: The Autobiographyof Kwame Nkrumah, that there was somuch to be done, with very little done in his life,that he (Mazrui) must also hurry with his accomplishments.Dr. Nkrumah, the future GhanaianPresident, quoted Tennyson‘s two-line memorablewords in his 1934 application for undergraduateadmission into Pennsylvania-basedLincoln University, where he had decided totravel from his native Gold Coast (now calledGhana) to acquire higher education, which wasobviously to prepare himself for the momentousand historic tasks that were lying ahead of him inhis native land (colonial Gold Coast) as part ofthe nationalist leadership to prompt the British, asthe colonial masters, to grant independence tothe colony. The words of Tennyson that Nkrumahquoted in 1934, which are important for us toquote as we are writing our essay about KenyanbornProfessor Mazrui, were the following:So many worlds, so much to doSo little done, such things to be …With a similar Western type of education, it isvery useful that we have drawn brief parallelsbetween Professor Mazrui‘s life and the lives ofGhana‘s Nkrumah and Uncle Joe (as AttorneyAppiah was affably called by all and sundry). Ofcourse, it is a truism that Mazrui is from Kenya inEast Africa, while Nkrumah and Appiah wereGhanaian compatriots, who were also earlierpolitical collaborators, thereby knowing eachother very well. Professor Mazrui, on the otherhand, also, knew both men well and has, in fact,written directly and indirectly about both of them.In his many classrooms, Dr. Mazrui has taughtan unlimited amount of courses in politics thattouched on the nationalist political struggles ofboth unique men when discussing West Africanpolitics. That is why we have deemed it veryuseful to quote, even if briefly, from theirpublished memoirs. While Dr. Mazrui‘s significancestarts with his birth in East Africa,it is a fact that the two West African politicalfigures, who were much older thanMazrui, lived and took part in the anti-colonialnationalist struggles of their belovedGold Coast, which became Ghana on March6, 1957, at independence. Fortunately, thepolitical and business aspects of AttorneyAppiah‘s life has been brilliantly discussedby Professor Emmanuel K. Akyeampong,the Harvard University historian, in a recentpublication in USA-based Journal of ThirdWorld Studies (<strong>2010</strong>), the flagship publicationof the Association of Third World Studies(ATWS) of Americus, Georgia.To a large extent, Dr. Mazrui — with hisversatility — could be seen as a product of Britishcolonial education in the 1950s and 1960s, andhe could easily be linked to the colonial history ofhis native Kenya and the overall colonial politicalexperiences in other parts of Africa. There, areindeed, many reasons for one to do such a comparisoneven if minimally.Therefore, before the advent of the activestruggles of African nationalists and Pan-Africaniststo break the yoke and shackles of colonialismas well as neo-colonialism on the continent, Africawas seen by European and other Western (or non-African) writers as being both mysterious andbackward. Toward that end, Joseph Conrad(1857–1924), the Polish-born English writer, hadthe audacity to pen his book, Heart of Darkness,in which he referred to Africa as the ―dark continent.‖It would take the writings of ProfessorMazrui and various progressive African authors tohelp debunk these stereotypical and condescend-

10 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>… Ali A. Mazrui in History and Politicsing descriptions. Sadly, some of these writerssuffered for their radical or ideological stancesand struggles in the interests of Africa as a continentand, to them, as a motherland. For example,Nkrumah, who was himself a prolific writerand a fierce fighter in the anti-colonial struggle inAfrica, suffered in a variety of ways. In the end,he had his elected government in Ghana overthrownon February 24, 1966 in a military-cumpolicecoup d’état that was, reportedly, engineeredby Western intelligence agencies (asdocumented in former CIA operative JohnStockwell‘s book, In Search of Enemies).As discussed in Kwame Nkrumah: PanafGreat Lives (1974) and in some of ProfessorMazrui‘s writings, Nkrumah eventually died inApril 1972 in faraway Bucharest, Romania, fromwhat Amical Cabral of Guinea-Bissau termed asa ―cancer of betrayal‖ (1974). Several other blackleaders and scholars, too, suffered in a variety ofways. For example, Finally They Killed Him(1980) was a book written by Nigerian scholars todocument several aspects of the brutal assassinationof Guyana‘s History Professor Walter Rodney,who penned How Europe UnderdevelopedAfrica (1968), a forceful indictment of Europeanforces that, in his opinion, kept Africa in the domainof what Conrad saw as a ―dark‖ continent;Dr. Mazrui has an affinity to him, including servingas a Rodney Professor in Guyana. Anotherblack nationalist scholar, who died from a mysteriousillness, was Franz Fanon, author of severalgreat works, including The Wretched of the Earth(1964).As the occupier of Albert Schweitzer EndowedProfessorship in the Humanities in theState University of New York (SUNY), with residenceat <strong>Binghamton</strong>, New York, Dr. Mazrui hasbenefitted from several prestigious invitations tocollege campuses. During such visits, he performsto his best and makes the name of Africashine, just as he did when, in 2009, his stellarachievements prompted the Indiana UniversityAfrican Students Association (IUASA) to bringhim to our campus. He held his large audiencespell-bound. It was similar to how both of us had,in an earlier period, successfully nominated andbrought on the Bloomington campus of IndianaUniversity (headed today by a stellar philosophyscholar, Provost Karen Hanson) two Nobel Laureates:Nobel Literature Laureate Wole Soyinkaof Nigeria and, later on, Costa Rican PresidentOscar Arias, the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate.In spite of Professor Mazrui‘s distinguishedPan-African scholarship and his ardent promotionof African culture, customs and ideals, he hasIGCS Director Ali A. Mazrui being awarded the Order ofthe Grand Companion of Oliver Tambo by former SouthAfrican President Thabo Mbeki, April 2007.had his share of African and diaspora-basedBlack critics for varied reasons. For example,some West African scholars, who admireGhana‘s late President Nkrumah (the Osagyefo)have never forgiven the famous Kenyan scholarfor writing an essay in the early years of TransitionMagazine, titled ―Nkrumah: The LeninistCzar,‖ which depicted Nkrumah as a ―Czar‖ ofsort in Africa. To such pro-Nkrumah critics ofMazrui, it was a ―how dare him‖ episodic issue.Yet, that did not dent the intellectual spirit or credentialsof Professor Mazrui, who had previouslybeen faulted because, to his ardent critics, hefirst rose to intellectual prominence by beingseen as a critic of some of the accepted orthodoxiesof African intellectuals between the 1960sand 1980s; he was also seen as an ardent criticof African socialism and Marxism, brands ofwhich Nkrumah as well as Tanzanian ex-PresidentJulius K. Nyerere and others practiced.Ali. A. Mazrui: Some Essential DetailsIn the 2005 global intellectual poll, ProfessorMazrui was ranked among 99 other distinguishedfigures, as being one of the world‘s top 100 publicintellectuals by readers of the United KingdombasedProspect Magazine and the WashingtonDC-based Foreign Policy Magazine. Yet, thosewho very well know the University of Oxford‘sNuffield College-educated political scientist add tothe public intellectual description a further descriptionof an ―organic intellectual.‖ In politicalscience dictum, it is Antonio Gramsci, who introducedthe concept, which has been applied toRodney in the superb writings of Caribbean‘sTrevor Campbell (1981); Horace Campbell (1991);and Nigeria‘s astute scholar, Biodun Jeyifo (1980).We have a purpose for adding the ―organicintellectual‖ accolade to Mazrui‘s public intellectualdistinction. In fact, we do not want to limithis intellectual precision and importance, hencewe have not added ―traditional intellectual‖ aspart of the accolade. For, as we understand itfrom Gramsci‘s perspective, traditional intellectualscan be seen as literary as well as scientificand religious persons, whose positions in intersticesof one‘s society has a certain inter-classaura about it. However, as Hoare and Smithhave been quoted as having underscored inLewis‘ book about Walter Rodney (1998), traditionalintellectual ―derives ultimately from pastand present class relations and seals an attachmentto various historical (and political) classforms.‖Instead, for various reasons, we see Dr.Mazrui as being both, a public intellectual and toa large extent, and an organic intellectual, especiallywith his contributions to Africa and the Developing(or Third) World. As variously amplified,the organic intellectual — of the Mazruian variation— happens to be, again in the words ofHoare and Smith (1978), the ever thinking andorganizing elements of a particular aura specificfundamental social class, who can be ―distinguishedless by their profession, which may beany job characteristic of their class, than by theirfunction in directing the ideas and aspirations ofthe class to which they organically belong.‖Unlike Rodney, who Columbia University ProfessorManning Marable (1986; 1987) as being partof the black intellectual tradition, Mazrui has afirebrand intellectual prowess as opposed toradical or revolutionary one.While Rodney and others used both astuteand propagandist scholarship in the interests ofblack people, Mazrui has purposely utilized hispolitical science expertise to bring Africa andother Developing (or Third) World areas into thefocus of the enlightened world. In fact, it is due tothe crusading writings of Mazrui and other blackintellectuals that is why today, we do not continueto hear some of the ridiculous questions of thepast about Africa; i.e., whether Africans live intrees, or whether Africans have tails, as depictedin some Tarzan movies. For example, in herexcellent memoirs, Living History (2003) — publishedimmediately after being America‘s FirstLady — U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary RodhamClinton, pointed out the importance of Americanslearning more about Africa. She was, indeed,pointing out several objectives for her fellowAmericans (before her departure for Africa, with

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 11… Ali A. Mazrui in History and Politicsdaughter Chelsea), and inter alia added:―… the importance of this last objective was illustratedwhen a journalist asked me before the trip,‗What is the capital of Africa?‘ ‖ While Mrs. Clintoncould afford to make a trip to learn, on the spot,about Africa, several of her compatriots wouldhave to rely on great scholars like the Mazruisand others to get the needed information, distilland use it. That, in essence is why Dr. Mazruican also be seen as an organic intellectual.With multi-faceted talents and researchagenda, Professor Mazrui‘s research interests,as can be ascertained easily by following his prolificwritings, have always included African politics,international political culture, political Islamas well as North-South relations. Maybe, the politicalIslam aspect unfortunately made an otherwisenice Indiana-based colleague describe theindomitable Dr. Mazrui as an ―Islamic fundamentalist,‖among other unflattering descriptions. Inthe foregoing contexts, Mazrui writes about Africantopics and other issues affecting other areasof the Developing (or Third) World.Very uniquely, Professor Mazrui has madesure that his writings about these crucial areas ofthe world do not languish only on the pages ofbooks. Therefore, he has taken steps to providehis admirers and the world televised documentaries,including ―The Africans,‖ a 1986 WashingtonDC-based Annenberg /CPB Project that was anine-part television series by PBS and narratedby Mazrui himself. The series did provide a historical-cum-politicaland cultural overview of thecontinent within the framework of the triple heritageof the traditions of Africa and foreign influences.Interestingly, the series was derived fromtwo of Dr. Mazrui‘s publication: The Africans: ATriple Heritage (1987); and the Africans: A Reader(1986). There were some critics, who felt thatthe nine-part series was influenced by BasilDavidson‘s own ―Africa: A Voyage of Discovery,‖a home television series (1984). Even so, it simplymeans that Dr. Mazrui is not an arm-chairscholar, who sits around restless and doing nothingbecause he has attained laurels in academicpromotions.Mazrui and ControversyAccording to many admirers and critics ofProfessor Mazrui, he is a scholar who thrives oncontroversy in his speeches, in his classroomteachings and, also, in his writings. Often, hisaudiences wonder how and when he finds controversialbut meaningful topics to discuss, andIGCS Director Ali A. Mazrui at a meeting with Ugandan President (first from right) Yoweri KagutaMaseveni, Kampala, Uganda, 2009.even why so. For example, he was asked to givea major lecture about Ghana‘s late PresidentNkrumah, who once invited him to serve on theinitial editorial board of Encyclopedia Africana.One wonders if it were a mere boldness or sheerarrogance when Dr. Mazrui theorized, in a publiclecture in Ghana, that ex-President Nkrumahwas a great African, but not a great Ghanaian.He reportedly based his thesis on the pervadingPan-Africanist stature of Nkrumah as opposed toGhana‘s internal political conditions, whichprompted the public uproar that contributed to hisoverthrow in the 1966 coup d’etat.The Ghanaian citizenry, from whichNkrumah drew his many supporters, wonderedhow and why Mazrui came to Ghana to tell themthat their great Osagyefo, after all, did more inthe realm of Pan-Africanism, including the sponsorshipof very extravagant or expensive projectsand even liberation movements externallywhen, in fact, the economy of Ghana was, asreported, in tatters. Consequently, Mazrui‘s contentionwas applauded by several Ghanaians, whosaw themselves within the political contexts ofthe late Oxford-educated Prime Minister K. A.Busia and the earlier University of London-educatedopposition leader, Lawyer Joseph B. Danquah.His critics felt that the good he did for liberationmovements and countries struggling for decolonizationmade outsiders see him as a great leader.Whether that is correct depends on the one makingthe assessment.In his writings, Professor Mazrui also hadhis share of critics, some fairly and others unreasonably.For example, when Heinemann EducationalBooks and New York‘s Third Press publishedhis 1971 novel, The Trial of ChristopherOkigbo, several Nigerians were divided in theopinions. Igbos from breakaway ―Biafra‖ in the Nigeriancivil war saw the book as a bold literaryexercise while anti-―Biafra‖ elements, who supportedthe Nigerian efforts to re-unite their country,felt that Mazrui was pandering to the otherside. Most certainly, these were fascinating contentions.Non-Africans also had their take on theOkigbo story, as told by Mazrui. In The New YorkTimes Book Review, George Davis wrote, amongother details about the publication, that in spite ofthe seriousness of the questions raised by thebook, there was something detached and alsoplayful about Dr. Mazrui‘s novel, adding: ―it becomesits own best proof that important politicalquestioning and art are not mutually exclusive.The Trial of Christopher Okigbo is a fine and unusualpiece of fiction.‖Professor Mazrui‘s historical-political novel— which marked him as a serious literary figure,was about aspects of the time and untimely

12 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>… Ali A. Mazrui in History and Politicsdeath of the poet, Okigbo. At the time of hisdeath in the Biafran war, he had published onlywhat critics saw as a slim volume of poems, titledLabyrinths. Yet, he was seen in celebrated poetrysense. It was, therefore, not surprising that oneof Africa‘s best writers, Professor Chinua Achebeof Things <strong>Fall</strong> Apart fame, wrote in 1978 thatOkigbo was not only the finest Nigerian poet ofhis generation, but that as his poems becomewidely known internationally, ―he will also be recognizedas one of the most remarkable anywherein our time.‖Another African writer, Lewis Nkosi, had theopportunity to interview Okigbo in 1962. Seeinghim as a poet‘s poet, Nkosi saw skepticism ofOkigbo‘s that his true poetic audience in Africawould be limited, adding that he believed he was―writing for other poets all over the world to readand see whether they can share in my experience.‖It was the unique experience that promptedhis older friend, Professor Mazrui, to write thenovel.In retrospect, many African scholars andreaders have offered opinions on ProfessorMazrui‘s ―Leninist Czar‖ essay, published in TransitionMagazine (1966). Many of them discussedthe ideological implications, as they wondered ifa socialist scholar would have written whatMazrui wrote. They, however, did not look at howwell researched and comparative, in conclusions,the piece was, as Mazrui started his essay with acomparison of several aspects of Lenin‘s works.For example, he wrote that Nkrumah‘s first book,Toward Colonial Freedom, ―was inspired byLenin‘s theory of imperialism … Nkrumah‘s lastpublication in office is Neo-Colonialism: The LastStage of Imperialism,” was inspired by Lenin‘stheory of imperialism.All of the foregoing assessments did notcause any ripples for Dr. Mazrui‘s African readersuntil they saw his other polemical assertions(of which Mzee Mazrui is famous), including thisone: ―There is little doubt that Nkrumah saw himselfquite consciously as an African Lenin. Hewanted to go down in history as a major politicaltheorist, and he wanted a particular stream ofthought to bear his own name.‖ Hence the term―Nkrumahism‖ … he also sought to be Ghana‘sCzar. Seeing Nkrumah as an authentic Africanleader or writer, his supporters or admirers didnot take kindly to these assertions. Other critics,who sided with Mazrui‘s tantalizing essay, alsowondered if the award of the Lenin Prize toNkrumah by the then Soviet leaders did not confirmtacitly that he either wanted to be or enjoyedto be seen in Leninist terms. All of these discussions,no matter the motives of the writer (i.e.,Mazrui) and the discussants, did contribute immenselyto African historical as well as politicalstudies, and the originator of the same (Mazrui)should be applauded for the discussions.It is a known fact that Professor Mazrui is athis best when his writings raise or introduce controversy,as he would handily face his critics withmethodical and purposeful debate, very often witha very civilized approach. From that, youngergenerations of African writers have benefitted and,in the end, grown or influenced to become seasonedscholars, campus professors and writers.Mazrui’s Black Diaspora-Cum-Pan-African Forays; His Contributionsto Pax-Africana and Beliefin African Cultures and TraditionsIn fact, the exemplary and distinguishedachievements of Professor Mazrui often remindus of some of the axiomatic anecdotes of theReverend Jesse Jackson, Sr., of Rainbow Coalitionfame. Often, when speaking to black youth,the ordained Minister would urge them to leaveall distractions as well as family shortcomingsbehind and, instead, to strive to become ―Somebody‖in life. In his preacher‘s voice, he woulddraw all sorts of analogies for the benefit of theyoungsters; he would say to the youngsters; thatsome of them felt or thought that having beenborn in a ghetto should be a barring factor towardtheir growth and aspirations, and urging themfurther: ―You might have been born in a ghetto,but always remember that the ghetto is not inyou, just as when a pregnant dog enters an ovento deliver its babies, we do not call them biscuits,but we still see them as puppies.‖ Malcolm X,too, used the analogy of a cat giving birth in anoven: the babies produced by the cat were stillkitten but not biscuits. Drawing on the wise wordsof Rev. Jackson and Malcolm X, therefore, boilsdown to the fact that Dr. Mazrui was, for example,born in Mombasa, Kenya, an African countrythat would, in the early 1960s, be known for itsviolent anti-colonial indigenous organizationcalled the Mau-Mau movement. In fact, in hisbiographical anecdotes, it is often indicated thatthe young Mazrui (born on February 24, 1933)studied at schools in Mombasa, in Kenya.No matter the amenities that the Mombasaschools lacked, young Mazrui was so determinedthat he went on to the United Kingdom, where heenrolled at University of Manchester to earn hisBachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree in 1960 with distinction,his Master of Arts (M.A.) degree in 1961from an Ivy League institution (Columbia University)of New York City, USA, followed by his Doctorof Philosophy (D. Phil.) degree in 1966 fromNuffield College, University of Oxford. The immediatequery is whether or not Mazrui, upon bagginghis terminal Oxford D. Phil. degree (withMolly, an English spouse in tow) made him a―Westerner‖, abandoned Mother Africa for thegreener pastures of the Western World or, inessence, failed to return to Africa to contributehis economic and intellectual quota? No, he didnot do so. If anything, he would return to Africa,via Uganda, to begin his great teaching careerand distinguished scholarship!Therefore, we can answer the query that hedid not exactly disappoint Mother Africa! Instead,the African Patriot in the young Dr. Mazrui (justlike the patriotism of Ghana‘s Uncle Joe andother nationalist leaders) took over for him to reurnto the Motherland via Makerere University;indeed, he reminds us a lot of this same seriousAfrican patriot, ―Uncle‖ Joe Appiah of Ghana thatwe mentioned earlier and above. Attorney Appiah— who can as well be described like Dr. Mazruias a public intellectual — wrote the great memoir,African Patriot; the U.K.-trained Attorney (or Lawyer)was so transparently patriotic and Africanthat many of his Ghanaian compatriots verystrongly harbor the feeling today that he (UncleJoe) was one of the best Presidents that Ghananever had the opportunity to have in leadership!Like Dr. Mazrui, he also returned to Ghana withBritish credentials and, Lady Peggy Appiah, hisBritish spouse, to whom he affectionately dedicatedhis published brilliant and very usefulmemoirs.Upon attaining academic or professionalUpon attaining academic or professional laurels,these accomplished African students returned tothe Motherland (Africa) to work, mostly out ofpatriotism and nationalist pride. For example, outof patriotic zeal and also ever ready to serve hisfellow Africans in need of high quality education,Dr. Mazrui joined the faculty of Uganda-basedMakerere University and, between 1966 and1973, served as the head of the Department ofPolitical and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences.At Makerere, he teamed up with otheryoung scholars to ―mint‖ new and young minds.In fact, in Europe, we encountered Dr. KrespoMuyonga, a former Ugandan diplomat in India,who earned his honors political science degreeas ―a Mazrui student.‖ At Makerere, Krespo, as a

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 13… Ali A. Mazrui in History and Politicsmentee of Dr. Mazrui, was elected the Presidentof the Student Government. He, like his mentor(Professor Mazrui) was forced into exile by IdiAmin‘s regime. That was when, between 1974and 1988, Mazrui worked for University of Michiganat Ann Arbor, three years of which he promotedAfrica and African diaspora studies asDirector of the Center for Afro-American andAfrican Studies (1978–1981).When Professor Mazrui left Michigan in1989, at the direct urging of then New York GovernorMario Cuomo to accept a New York-basedendowed professorship, he followed the proverbialfootsteps of Toni Morrison as the AlbertSchweitzer Professor in the Humanities and,subsequently, as the founding Director of theInstitute of Global Cultural Studies (IGCS),through which he brought some of Africa‘s brilliantminds and public figures to his campus,including Professors Soyinka, Adu-Boahen andseveral others; Nigeria‘s former Head of State,Dr. Yakubu Gowon, has visited the campus aswell, which adds up to show Dr. Mazrui‘s eminentstature in African affairs.To many Mazruian admirers, it was noteworthy that the endowed position he went to occupyat <strong>Binghamton</strong> University of the State Universityof New York (SUNY) was named after amedical doctor, who did a lot for Africa and Africans,particularly in the Congo sub-region. Dr.Albert Schweitzer, who was born in Germany onJanuary 14, 1875 and died at 90 years old onSeptember 4, 1965, in fact received the NobelPeace Prize for his philosophy of reverence forlife, which he expressed actively in founding andsustaining the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in Lambarene,the area in Central Africa that is todaycalled Republic of Gabon. While Mazrui todaywrites prolifically to make his works available tohumanity, it is also a fact that Schweitzer had apassionate quest to introduce a universal ethicalphilosophy that would subsequently be envelopedin a universal reality.Apart from his respective full-time positionsin Michigan and <strong>Binghamton</strong> (New York), ProfessorMazrui has also held concurrent faculty appointmentsand other positions that have Pan-African input: as Albert Luthuli Professor-at-LargeEmeritusin Jos, Nigeria, and Senior Scholar inAfricana Studies at Cornell University, Ithaca,New York; and until recently, Chancellor ofJomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture andTechnology in Nairobi, Kenya.Very interestingly, Professor Mazrui doesnot concentrate his intellectual and professionalbenevolence in Africa. In fact, when Guyana‘seducational leaders saw fit to inaugurate WalterRodney Professorship on the Guyana campus ofthe University of Guyana, it was to Dr. Mazruithat they turned, thereby making him the inauguralWalter Rodney Professor. He traveled all theway to Georgetown, Guyana, for the inauguralfestivities; holding the position for several years,he retired from tit in 1999. Also, to propagate Africanstudies and scholarship, Professor Mazruihas traveled far and wide as well as held visitingprofessorships and lectureships in many countries,including Canada, Singapore, Pakistan,USA, Iran, Ghana, Tanzania, UK and Germany,among others.As a Muslim, with authentic Islamic credentialsthat he attained from his Kenyan father, whowas in his lifetime a leading Islamic scholar, ProfessorMazrui is known as an impeccable commentatoron Islam and Islamism. Pointedly andtransparently, he abhors terrorism in all of itsforms. His numerous honors and honorary doctoraldegrees go a long way to show that an Africancan achieve as much as serious scholarsfrom other racial entities. For example, apart frombeing honored in 2000 in a Millennium Tribute foroutstanding scholarship by the U.K.-basedHouse of Lords, it is very reassuring that ProfessorMazrui — as pointed out earlier — has beenranked among the world‘s top 100 public intellectuals.In fact, during his foreign travels and in hisinteractions with other Africans, Professor Mazruireceived traditional and cultural honors. For example,in Ghana, he was honorifically made (orenthroned) as an Akan chieftain, whereby he wasgiven the Akan title of Nana, symbolizing reverence.Therefore, several Ghanaians, includinghis great scholarly friend (the late History ProfessorAlbert Adu Boahen) referred to him as ProfessorNana Ali A. Mazrui. Many Akan peoplefrom Ghana were glad that Dr. Mazrui acceptedthe chieftaincy title and the Nana accolade. In hispublished 1990 memoirs, Attorney Appiah wrote,inter alia, about Ghanaian chieftaincy: ―Chieftaincyis one of the noblest and most sacredinstitutions bequeathed to us by our ancestors.‖Also, when our family presented Dr. Mazrui witha piece of Ghana-made Kente cloth, sometimescalled muffler, he used it very often during impor-(continued on page 17)Dr. Ali A. Mazrui with Indian Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, New Delhi, India,November 2008.Dr. Ali A. Mazrui speaking at a conference in Cairo, Egypt, on “Islam inInternational Affairs.” The session was chaired by an Egyptian scholar,seated next to Dr. Mazrui.

14 Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong>Interview with Professor F. Sonia Arellano-LópezBy IGCS reporterDr. F. Sonia Arellano-López joined the Instituteof Global Cultural Studies (IGCS) in <strong>Fall</strong><strong>2010</strong> as a Research Assistant Professor.Could you please tell us more about your academicbackground?I began my academic studies in La Paz,Bolivia in the Sociology and Political ScienceDepartment of the Universidad Mayor de SanAndres. During my second year at the Universitythere was a military coup and the universityclosed. Many university students were taken incustody. Some spent some time in jail, otherswere deported, and others looked for asylum atthe embassies. As a result, I moved to Quito,Ecuador where I continued my studies at thePontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.There I obtained my bachelors degree in Sociologyand Political Science. Later, I completed myM.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Sociology at <strong>Binghamton</strong>University.What are you recent research interests?I have been interested for many years ingrassroots social movements, and particularly inthe struggles of indigenous people. Many socialmovements have developed around strugglesover land and natural resources, and I am interestedin how people‘s relationships to land, or therelationships they want to have with land, influencehow they define their political goals andstrategies. My doctoral research was on howtrade and commerce in Botswana was organizedalong lines of race and ethnicity. This has led meto be interested in the roles of race, ethnicity, andculture as sources of identity as well as organizingaxes of human productive activities.How did you come to know about ProfessorMazrui and his work?When I was a doctoral student at SUNY-<strong>Binghamton</strong>I read Professor Mazrui‘s work, and manypeople that I have worked with in southern Africahave been influenced by Professor Mazrui‘swork. His writing has provided material for manyinteresting conversations about developmentissues in Africa.What are the factors that have shaped yourscholarly pursuits?Two factors have been very important forme. One is that my parents were from modestsocioeconomic circumstances, and they believedstrongly that education was a key for understandingthe world and improving one‘s situation in it.They encouraged me to study and do my best,even when circumstances made study difficult.The second is that, while I was growing up, politicalinstability was a defining factor of life in Bolivia.That instability, and the associated conflict,made me want to understand the origin and dynamicsof political struggles.Your dissertation was on the historical developmentof ethically based networks of tradeand commerce in Botswana. Could youplease tell us more about your dissertation?My dissertation research focused on hownetworks of trade and commerce in colonial Botswanadeveloped along ethnic lines. Africanswere largely excluded from entrepreneurial rolesby the colonial authorities. However, the Europeanswho were there representing colonial authoritieswere only interested in those aspects oftrade and commerce that had to do with generatingwealth for Great Britain and extending Britishpower in southern Africa. This left many spacesthat were filled by Asians, but with many restrictions.As a result, trade and commerce was organizedalong ethnic lines, according to a racialhierarchy that was enforced by the colonial government,but which functioned on a day-to-daybasis based on informal rules. When Botswanabecame independent, the ethnic organization oftrade and commerce, along with the informal arrangementsamong different ethnic groups, continuedin the new context.What aspects of your previous work dealtwith the issue of culture?Most of my work has dealt with the issue ofculture. Culture underlies the way that peoplerelate to one another, in a context of trade andmarket relations, or in social conflicts over landand resources. It often is not explicit, and is embeddedin other issues, but it is always there.You have a wide experience working withNGOs, particularly on issues related to gender,culture and the environment, in whatNGOs activity are you currently involved?I should clarify that I am not working withany NGOs now, and all of my work is with theInstitute. I have worked with NGOs and developmentagencies interested in understanding socialconflicts in order to support poor rural populations,particularly populations composed of indigenouspeople, in improving their quality of life.This work enriched my professional development,because it forces you to confront socialtheory with empirical reality. This confrontation isusually more messy, and complicated, than mostof our academic publications suggest, and it challengesyou to reflect and question what you thinkyou know and understand.You are in the process of finalizing a numberof papers as well. Could you please tell usmore about your work that is still in progress?I am currently working on several articlesthat develop themes from my doctoral research,and I hope to turn my dissertation into a book. Iam also working on some Latin American materialthat has to do with indigenous women andenvironmental conservation. I am also finishingan entry on Sojourner Truth for an encyclopediaof Great African American Lives, which will bepublished by Salem Press.Which of the IGCS projects will you be involvedin? Could you please tell us moreabout your IGCS project plans?I have been working with ProfessorMazrui to help with the editing of some of hismanuscripts for publication. I also enjoy teachingand plan to teach some classes looking at culturalissues that complement what ProfessorsMazrui and Adem are already offering. Since mygeographic expertise is different from theirs, Ithink we have an opportunity to learn from oneanother. I know I have been learning a lot fromthem. Of course generating external funding is animportant task for any university professor, especiallyduring difficult economic times like we arecurrently experiencing. So, I hope to be successfulin developing some project to bring outsidefunds to the university that will help strengthenthe Institute‘s program.

Institute of Global Cultural Studies, <strong>Volume</strong> 8, <strong>Fall</strong> <strong>2010</strong> 15Indigenous People and the Promotion ofEnvironmental Conservation and Sustainable DevelopmentBy F. Sonia Arellano-LópezThere is currently great worldwide concernabout environmental issues generally, and thespecific actions needed to address the impacts ofclimate change. Developing countries are a focalpoint of this concern, and numerous donor organizationsare providing financial support in thename of improving their capacity to managenatural resources. This may be seen in a varietyof areas, including from policy reforms to reducecarbon emissions and manage carbon stocks,local-level projects to make the farming systemsof poor families more resilient in the face of climatechange, and the promotion of clean energyranging from the promotion of more efficient cookstoves to support for alternate fuel development.While diverse in their specific content these effortsshare stated objectives to promote sustainableuse of natural resources. Because efforts topromote environmental conservation and/or environmentallysustainable economic growth challengeexplicitly or implicitly models of economicgrowth that have dominated the thinking of donororganizations until very recently, there is a widespreadassumption that poor people will be majorbeneficiaries of development efforts based on thenew environmental consciousness.This assumption is particularly strong withrespect to indigenous peoples in Latin America.Not only are they among the poorest and mostoppressed people within many of the states inwhich they reside, we also tend to regard themas part of the environment we seek to protect.This vision contrasts with our self-image, whichtends to view the growth of Western society as aprogressive distancing from the limitations imposedby the natural environment. Thus, one featureof our concern with conservation and sustainabledevelopment is that we often turn toindigenous peoples for knowledge about how touse natural resources in ways that provide alternativesto the destructive and non-sustainablepattern of resource use commonly associatedwith the expansion of capitalist production relations.2A more critical understanding of the costs ofparticular patterns of economic growth will undoubtedlyyield social as well as environmentalbenefits. Similarly, it may well be that the productionknowledge of Native People contains importantunderstanding about the biological bases ofsustainable production systems, as well as aboutthe social and institutional relations required forthem to function. At the same time, efforts topromote environmental conservation and sustainabledevelopment and to improve the well beingof Native People also need to be subject to importantcaveats. First, the destructive use of naturalresources associated with capitalist economicgrowth has been closely linked to strugglesover access to land and other resources. To theextent that conservation and sustainable developmentefforts fail to promote institutional arrangementsthat equitably resolve these conflicts,their results will be disappointing. 3Second, as researchers such as Bartra(1992) have pointed out, Western assumptionsabout Native People as being close to naturehave more to do with our images of ourselves asbeing separate from nature than they do with anyparticular understanding of the historical contextin which their production systems have developed.If it is true that there are examples of NativePeople who offer the hope that their knowledgecan be the basis of sustainable patterns ofland management, and who seek to advancetheir struggles for land and political autonomythrough alliances with international environmentalinterests, it is also true that there are many moreNative People who are both major agents andvictims of environmental destruction, where conservationefforts have made environmental destructionworse by ignoring the historical circumstancesthat have fostered particular kinds ofland use. 4There are no clear, unequivocal criteria forclassifying specific people as ―indigenous,‖ inLatin America, or elsewhere. Phenomena associatedwith changing production relations in thecountryside, like rural-urban migration and agrarianreform have often disrupted customs, the useof indigenous languages, and land tenure relationsthat mark and reinforce the ethnic identity.This has increased assimilationist pressures onall but the most isolated populations. There areno reliable statistics that measure the numbers ofindigenous populations, or the degree to whichthey have been assimilated into the national societiesthat surround them. National populationcensuses are no more than rough guide becausemany governments tend to deny that their countrieshave substantial indigenous population. 5In this context, International Labor Organization(ILO) Convention No. 169, on Indigenousand Tribal Peoples, provides a description ofessential features of indigenous peoples. Thedeclaration defines as indigenous communities,peoples and nations that have a historical continuitywith the pre-invasion and pre-colonial societiesthat developed on their territories; andconsider themselves distinct from other sectorsof the societies now prevailing on those territoriesor parts of them. The declaration also affirms thatindigenous peoples represent non-dominant sectorsof the society and are determined to reserve,develop and transmit to future generations theirancestral territories and their ethnic identity asthe basis of their continued existence as peoples,in accordance with their own cultural patterns,social institutions and legal systems. 6The ILO declaration associates indigenouspeoples with a strong ancestral attachment toterritory and land issues, recognizing that historicallymost of them were integrated and subordinatedto broader economic and social groupingswithin colonial agricultural and mining systems.The subordination of indigenous peoples asfarmers and miners was understood as assimilationto the predominant economic system, andthe outcome of it was to deprive them of their socioculturalroots. Such assimilation often becamea justification for denying their right to territorydefined in terms of their indigenous identity.The declaration understands indigenouspeoples as integral collectivities, existing withinterritories, where western sociocultural and juridicalsystems prevail, adapting and modifyingsome of their patterns in order to survive in anunequal capitalist system. This is especially importantin cases where historical references tellus that the process by which their territory wasappropriated in the name of ―progress‖ and ―development‖signified the impoverishment andmarginalization of the already displaced indigenouspeople. 7It is the distinction between the individualand collective association of indigenous peopleswith economic, socio-cultural and juridical contextthat determines whom it is possible to categorizeas indigenous. Indigenous peoples who havebeen assimilated by the agricultural system areregarded first as peasants, small farmers orsmallholders. By the same token if they wereassimilated economically by the mining systemthey are regarded first as miners by governmentsand other interested parties. It is the associationof indigenous peoples with certain economicactivities that results in the loss of theirsocial, cultural and juridical systems, upon whichrests their collective identification in the overallsociety. Understanding the complexity of thedefinition of indigenous peoples and assumingthat they represent a collectivity as well individu-