You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

plain talk®<br />

<strong>Taxes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mutual</strong> <strong>Funds</strong><br />

How taxes can affect your investments

Why Plain Talk?<br />

At The Vanguard Group—a leading proponent of investor education in<br />

the mutual fund industry—we believe that knowledge is one of the<br />

keys to investment success. To that end, we have developed our Plain<br />

Talk Library, a series of c<strong>and</strong>id, concise, <strong>and</strong> easy-to-underst<strong>and</strong><br />

publications on a wide variety of investment topics.<br />

To request a free copy of any of these brochures, call us at<br />

1-800-662-7447 on business days from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. <strong>and</strong><br />

on Saturdays from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Eastern time. You can also<br />

read or order them online at www.vanguard.com.<br />

We hope you find the information in the Plain Talk Library helpful as<br />

you chart your investment course with us.<br />

■ <strong>Mutual</strong> Fund Basics<br />

■ The Vanguard Investment Planner<br />

■ Women <strong>and</strong> Investing<br />

■ Financing College<br />

■ Preparing to Retire<br />

■ Investing During Retirement<br />

■ Estate Planning Basics<br />

■ How to Select a Financial Adviser<br />

■ Measuring <strong>Mutual</strong> Fund Performance<br />

■ Bear Markets<br />

■ Bond Fund Investing<br />

■ Index Investing<br />

■ International Investing<br />

■ <strong>Taxes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mutual</strong> <strong>Funds</strong><br />

■ Dollar-Cost Averaging<br />

■ Why Vanguard?

<strong>Taxes</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Mutual</strong> <strong>Funds</strong><br />

<strong>Taxes</strong> are an important consideration for investors. Unless<br />

you pay careful attention to the tax implications of your<br />

mutual fund investments, taxes can sharply reduce the<br />

earnings you are actually able to keep. Fortunately, you don’t<br />

need an accounting or law degree to underst<strong>and</strong> the basics of<br />

taxes <strong>and</strong> mutual funds.<br />

This Plain Talk brochure explains how mutual fund investments<br />

are taxed. The focus is on mutual funds in taxable accounts, but<br />

we will also note how you can delay or even completely avoid<br />

taxes by using tax-deferred or tax-exempt accounts.<br />

Though this brochure is not meant to serve as a complete guide<br />

for all tax questions, it can help you make sound investment<br />

decisions, choose funds that are appropriate for you, <strong>and</strong><br />

minimize the impact of taxes on your investment returns.<br />

Note that a glossary appears at the back of this brochure. Terms<br />

that may be new to readers are printed in blue (for example, cost<br />

basis) the first time they occur.

Contents<br />

How Your <strong>Mutual</strong> Fund Investments Are Taxed ....................................... 1<br />

How a Fund’s Investment Strategy Can Affect <strong>Taxes</strong> ............................... 8<br />

Calculating <strong>and</strong> Reporting Your <strong>Taxes</strong> ...................................................... 12<br />

The Impact of <strong>Taxes</strong> on Your Investment Returns .................................... 17<br />

What to Do About <strong>Taxes</strong> ........................................................................... 19<br />

Tax-Efficient Vanguard <strong>Funds</strong> ................................................................... 24<br />

Vanguard’s Tax Information Services ........................................................ 26<br />

A Vanguard Invitation ............................................................................... 28<br />

Glossary .................................................................................................... 30

H OW YOUR M UTUAL F UND<br />

I NVESTMENTS A RE TAXED<br />

Since your goal as an investor should be to keep as much as<br />

possible of what you earn from mutual fund investments, you<br />

can’t look past the inescapable reality that taxes take a big bite<br />

out of bottom-line returns.<br />

As a mutual fund investor, you can incur income taxes in three<br />

ways: when the fund distributes income dividends, when the<br />

fund distributes capital gains from the sale of securities, <strong>and</strong><br />

when you sell or exchange fund shares at a profit. First we’ll<br />

explain how a fund’s earnings are taxed—then we’ll show how<br />

your sales or exchanges of shares can trigger taxes.<br />

Owning shares <strong>and</strong> paying taxes<br />

A mutual fund is not taxed on the income or profits it earns<br />

on its investments as long as it passes those earnings along<br />

to shareholders. The shareholders, in turn, pay any taxes due.<br />

Two common types of distributions that mutual funds make<br />

are income distributions <strong>and</strong> capital gains distributions.<br />

■ Income distributions represent all interest <strong>and</strong> dividend income<br />

earned by securities—whether cash investments, bonds, or<br />

stocks—after the fund’s operating expenses are subtracted.<br />

■ Capital gains distributions represent the profit a fund makes<br />

when it sells securities. When a fund makes such a profit, a<br />

capital gain is realized. When a fund sells securities at a price<br />

lower than it paid, it realizes a capital loss. If total capital gains<br />

exceed total capital losses, the fund has net realized capital gains,<br />

which are distributed to fund shareholders. Net realized capital<br />

losses are not passed through to shareholders but are retained<br />

by the fund <strong>and</strong> may be used to offset future capital gains.<br />

1

Occasionally distributions from mutual funds may include a<br />

return of capital. Returns of capital are not taxed (unless they<br />

exceed your original cost basis) because they are considered<br />

a portion of your original investment being returned to you.<br />

Generally, income dividend <strong>and</strong> capital gains distributions are<br />

subject to federal income taxes (<strong>and</strong> often state <strong>and</strong> local taxes as<br />

well). You must pay taxes on distributions regardless of whether<br />

you receive them in cash or reinvest them in additional shares.<br />

The exceptions to the general rule are:<br />

■ U.S. Treasury securities, whose interest income is exempt from<br />

state income taxes.<br />

■ Municipal bond funds, whose interest income is exempt from<br />

federal income tax <strong>and</strong> may be exempt from state taxes as well.<br />

However, any capital gains on U.S. Treasury securities or<br />

municipal bond funds are generally taxable.<br />

While the amount of income <strong>and</strong> capital gains you receive from a<br />

mutual fund affects the taxes you pay, another important factor is<br />

the holding period—that is, how long the fund held the securities<br />

before they were sold. Securities held for one year or less before<br />

being sold are categorized as short-term capital gains (or losses).<br />

Short-term capital gains are taxed at your ordinary income tax<br />

rate, as shown in Figure 1. But long-term capital gains—gains on<br />

Figure 1<br />

Federal Income Tax Rates<br />

Rates applied to taxable income in 2001<br />

15% 28% 31% 36% 39.6%<br />

Single Up to $ 27,051 to $ 65,551 to $136,751 to $297,351<br />

$27,050 $ 65,550 $136,750 $297,350 <strong>and</strong> up<br />

Married, Up to $ 45,201 to $109,251 to $166,501 to $297,351<br />

Filing Jointly $45,200 $109,250 $166,500 $297,350 <strong>and</strong> up<br />

Married, Up to $ 22,601 to $ 54,626 to $ 83,251 to $148,676<br />

Filing Separately $22,600 $ 54,625 $ 83,250 $148,675 <strong>and</strong> up<br />

Note: Income brackets are adjusted annually for inflation.<br />

Source: Internal Revenue Service.<br />

2

New tax rates on certain capital gains<br />

Federal income tax rates have been reduced on certain capital gains known<br />

as “qualified five-year gains.”<br />

■ For taxpayers in the 15% bracket, the tax rate on capital gains from the<br />

sale of assets that have been held longer than five years has dropped<br />

from 10% to 8%. Tax rates on capital gains from the sale of assets held<br />

five years or less are unchanged.<br />

■ For taxpayers in the higher brackets (28%, 31%, 36%, <strong>and</strong> 39.6%), the tax<br />

rate on capital gains from the sale of assets purchased after January 1,<br />

2001, <strong>and</strong> held longer than five years (that is, the assets are not sold until<br />

2006 or later) has dropped from 20% to 18%. Tax rates on capital gains<br />

from the sale of assets held five years or less are unchanged.<br />

Taxpayers in the higher brackets (28% or higher) can make assets they own<br />

eligible for the 18% rate (rather than the 20% rate) in 2006 or later by treating<br />

those assets as having been sold <strong>and</strong> reacquired at their closing prices on<br />

January 2, 2001. By “marking assets to market” in this way, a taxpayer can<br />

recognize capital gains (but not losses). The gains as of January 2 are taxed<br />

currently at the old rate of 20% (or a higher rate if it’s a short-term gain) <strong>and</strong><br />

must be reported to the IRS in a letter filed with the investor’s tax return for the<br />

tax year that includes January 1, 2001. If the asset is then sold in 2006 or later,<br />

increases in the value of that asset are taxed at the 18% rate.<br />

Example: An investor bought 100 shares of a company for $1,000, or $10<br />

a share, in 1996. On January 2, 2001, the shares closed at $20 each. The<br />

investor marks them to market <strong>and</strong> pays a 20% tax on her $1,000 profit—a<br />

total of $200 in tax. In 2006, she sells the shares for $3,000, or $30 a share,<br />

so she has a five-year gain of another $1,000 that is taxable at 18% ($180).<br />

Her total tax bill is $380—$200 paid in 2001 <strong>and</strong> $180 paid in 2006. If she<br />

had not marked the shares to market, her total tax bill would have been $400<br />

in 2006—so she saved $20. However, the $200 paid in taxes in 2001 could<br />

have been invested from 2001 to 2006, possibly earning more than $20.<br />

We recommend that you consult a tax or financial adviser about whether<br />

marking to market would be beneficial in your individual situation. Be sure<br />

to consider state <strong>and</strong> local income taxes in making your decision.<br />

3

securities the fund held for longer than one year before being sold—<br />

are taxed at a maximum rate of 20%. (The long-term capital gains<br />

rate is a maximum rate of 10% for taxpayers in the lowest income<br />

tax bracket.)<br />

Your mutual fund will tell you the category of any capital gains<br />

it distributes. This is determined by how long the fund held the<br />

securities it sold, not by how long you have owned your shares.<br />

For example, say you first bought shares in a fund last month <strong>and</strong><br />

today the fund is making a capital gains distribution as a result<br />

of selling securities it owned for five years. That distribution is<br />

a long-term capital gain because the fund’s holding period was<br />

longer than one year. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, say you bought shares<br />

in a mutual fund ten years ago. The fund makes a capital gains<br />

distribution because it sold securities it had held for six months.<br />

That distribution is a short-term capital gain for you because<br />

the fund’s holding period was less than one year.<br />

These are key distinctions simply because not all investment income<br />

is treated equally. Income (such as interest <strong>and</strong> dividends) <strong>and</strong> shortterm<br />

capital gains are taxed as ordinary income at your marginal tax<br />

rate (which can range from 15% to 39.6%, as shown in Figure 1 on<br />

page 2). Net capital gains on securities held longer than one year<br />

are taxed at a maximum rate of 20% (a maximum rate of 10% for<br />

taxpayers in the lowest tax bracket).<br />

Internal Revenue Service Form 1099-DIV, which your mutual<br />

fund usually sends in January for the previous tax year, details fund<br />

distributions you must report on your federal income tax return,<br />

including both income distributions <strong>and</strong> capital gains distributions<br />

from your funds. You won’t receive a Form 1099-DIV for mutual<br />

funds that distribute tax-exempt interest dividends (such as<br />

municipal bond funds) or for funds on which you earned less<br />

than $10 in dividends. (However, you still owe taxes on all taxable<br />

distributions, regardless of their size.) For more information,<br />

see Calculating <strong>and</strong> Reporting Your <strong>Taxes</strong> on page 12.<br />

4

<strong>Taxes</strong> on sales or exchanges of shares<br />

You can trigger capital gains taxes on mutual fund investments by<br />

selling some or all of your shares at a profit, or by exchanging shares<br />

of one fund for shares of another. The length of time you hold<br />

shares <strong>and</strong> your tax bracket determine the tax rate on any gain.<br />

Three important notes:<br />

■ All capital gains from your sale of mutual fund shares are<br />

taxable, even those from the sale of shares of a tax-exempt fund.<br />

■ Exchanging shares between funds is considered a sale, which<br />

may lead to capital gains. (An exchange involves selling shares of<br />

one fund to buy shares in another.)<br />

■ Writing a check against an investment in a mutual fund<br />

with a fluctuating share price (all funds except money market<br />

funds) also triggers a sale of shares <strong>and</strong> may expose you to<br />

tax on any resulting capital gains.<br />

Timing affects your taxes<br />

Here’s an example of how timing may affect taxes on the sale of mutual fund<br />

shares: If you buy 100 shares of mutual fund ABC for $20 a share <strong>and</strong> sell<br />

them six months later for $22 a share, you owe taxes on your $200 shortterm<br />

capital gain. If you’re in the 31% marginal tax bracket, that’s $62.<br />

However, if you hold on to the shares for more than 12 months after the<br />

original purchase, your profit is considered a long-term gain. Therefore, it is<br />

taxed at a maximum capital gains rate of 20% (for a maximum total tax of<br />

$40 on the $200 capital gain).<br />

Real-life calculations often aren’t so tidy, especially for investors who buy<br />

mutual fund shares at different times <strong>and</strong> at different prices. In Calculating<br />

<strong>and</strong> Reporting Your <strong>Taxes</strong> (pages 12–16), we’ll explain how to figure gains or<br />

losses on sales of mutual fund shares.<br />

5

Don’t buy a tax bill with your fund shares<br />

The tax owed on mutual fund investments may also depend in part<br />

on when you buy the shares. <strong>Mutual</strong> fund distributions, whether<br />

from income dividends or capital gains, are taxed in the year they<br />

are made. However, under certain circumstances, distributions<br />

declared during the last three months of a year <strong>and</strong> paid the<br />

following January are taxable in the year they were declared.<br />

If you hold shares in mutual funds that declare dividends daily<br />

—such as money market <strong>and</strong> bond funds—you are entitled to<br />

a dividend for each day you own shares in the fund. For other<br />

funds, such as stock <strong>and</strong> balanced funds, dividend <strong>and</strong> capital<br />

gains distributions are not declared daily but according to a<br />

regular schedule (monthly, quarterly, semiannually, or annually).<br />

When a mutual fund makes a distribution, its share price (or net<br />

asset value) falls by the amount of the distribution. For example,<br />

let’s say you own 1,000 shares of Fund X worth $10,000, or<br />

$10 a share. The fund distributes $1 a share in capital gains, so<br />

its share price drops to $9 a share on the fund’s reinvestment<br />

date (not counting market activity). You’ll still have $10,000<br />

(1,000 x $9 = $9,000, plus the $1,000 distribution). But you’ll<br />

owe tax on the $1,000 distribution, even if you reinvest it to buy<br />

more shares.<br />

So when considering a purchase of fund shares, ask the fund<br />

company about the fund’s next distribution—when it will take<br />

place <strong>and</strong> how large it is expected to be. If you own shares on<br />

the fund’s record date, you will receive the distribution. That<br />

means if you purchase shares shortly before the record date,<br />

you are “buying the distribution”—you’ll owe taxes on the<br />

capital gains that were reflected in the share price when you<br />

bought shares. In effect, a portion of your investment is being<br />

“returned” to you as a taxable capital gain.<br />

6

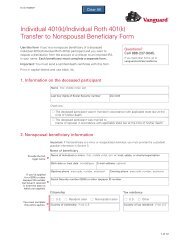

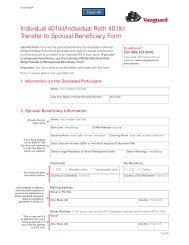

Tax-deferred <strong>and</strong> tax-exempt accounts<br />

The rules explained in this brochure apply only to taxable investments, not<br />

to tax-deferred investments such as those in employer-sponsored retirement<br />

plans (401(k) <strong>and</strong> 403(b) plans), individual retirement accounts (traditional<br />

IRAs), or variable annuities. Nor do these rules apply to Roth IRAs, which<br />

can be tax-free at withdrawal.<br />

Usually people are not taxed on the earnings in tax-deferred accounts<br />

until they start withdrawing money from the accounts—typically during<br />

retirement. Whether the withdrawals take the form of a lump sum or an<br />

installment payment, the taxable portion is always considered ordinary<br />

income (as opposed to capital gains) <strong>and</strong> thus taxed at the taxpayer’s<br />

marginal rate for the years when the withdrawals occur. IRA withdrawals<br />

taken before age 591 /2 are generally taxable <strong>and</strong> subject to an additional<br />

10% penalty tax. (Note, however, that distributions from Roth IRAs after a<br />

taxpayer reaches age 591 /2 will be tax-free if the Roth IRA has been held<br />

longer than five years.)<br />

Some tax-deferred investments offer added tax advantages. For example,<br />

you may be able to contribute wages or salary on a pre-tax basis. In a 401(k)<br />

plan, for example, money you contribute to the plan is deducted from your<br />

pay before it is taxed, which reduces your taxable wages. Similarly, many<br />

investors can deduct some or all of their contributions to traditional IRAs,<br />

which also reduces their taxable income. (Contributions to Roth IRAs are<br />

never deductible.)<br />

In retirement plans that allow pre-tax contributions (for example, 401(k)<br />

plans <strong>and</strong> traditional IRAs), withdrawals from the account are taxed as<br />

ordinary income. But for after-tax contributions to tax-deferred accounts<br />

(for example, if you invest $1,000 of take-home pay in a variable annuity<br />

or a nondeductible traditional IRA), you pay taxes only on earnings that<br />

accumulate in the account, because the contribution has already been taxed.<br />

7

H OW A F UND’ S I NVESTMENT S TRATEGY<br />

CAN A FFECT TAXES<br />

The likelihood that a mutual fund will pass along taxable<br />

distributions is heavily influenced by two factors: the kinds of<br />

securities the fund invests in <strong>and</strong> the fund’s investment policies.<br />

Security holdings<br />

Money market funds<br />

Most money market funds pay dividends that are fully taxable.<br />

(Some funds—those that invest in municipal securities—earn<br />

interest that is generally not subject to federal income tax <strong>and</strong><br />

that often is exempt from state <strong>and</strong> local taxes as well.*) However,<br />

because these funds are designed to maintain a constant value<br />

of $1 per share,** they do not ordinarily generate capital gains or<br />

losses, either within the fund or as the result of sales or exchanges<br />

you make.<br />

Bond funds<br />

Ordinarily, bond funds produce relatively high levels of taxable<br />

income. Over long periods, almost all the return from bond funds<br />

comes from dividend payments. However, because the prices of<br />

bonds <strong>and</strong> bond funds fluctuate in response to changing interest<br />

rates, it is possible to have taxable capital gains from investing in<br />

bond funds, even tax-exempt bond funds. Sometimes a fund will<br />

generate taxable capital gains distributions by selling bonds at<br />

a profit. Alternatively, a shareholder can trigger a capital gain<br />

by selling shares in a bond fund for a price higher than the<br />

original cost.<br />

8<br />

*For some investors, however, a portion of the fund’s income may be subject to the<br />

alternative minimum tax.<br />

**An investment in a money market fund is not insured or guaranteed by the<br />

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or any other government agency.<br />

Although a money market fund seeks to preserve the value of your investment<br />

at $1 per share, it is possible to lose money by investing in such a fund.

Stock funds<br />

Stock funds may pass along income from dividends paid by<br />

stocks held in the fund as well as from capital gains from the<br />

sale of stocks. Over time, however, most of the return from<br />

stocks comes from appreciation in stock prices. Because stock<br />

prices fluctuate considerably, you are generally more likely to<br />

realize a capital gain or loss when selling shares of a stock mutual<br />

fund than when selling shares of bond funds or money market<br />

funds. If you sell shares that have fallen in value, you won’t owe<br />

taxes on the transaction; indeed, you may be able to take a<br />

deduction for a capital loss.<br />

But to gauge the tax impact, it’s not enough merely to know<br />

that a fund owns stocks. You must know what kind of stocks<br />

it owns. Carefully study a stock fund’s objective to learn whether<br />

it emphasizes income or capital appreciation. Also determine<br />

whether it concentrates on value stocks (which generally pay<br />

higher dividend yields) or growth stocks (which seek long-term<br />

capital growth rather than current income). The annualized rate<br />

at which a stock earns income (known as the dividend yield, which<br />

can be found in a fund’s annual report) serves as one indication<br />

of whether a fund takes a value or growth approach.<br />

Large, well-established companies are more likely to pay dividends<br />

than smaller companies, which generally reinvest any profits back<br />

into the company to pay for growth. Consequently, funds that<br />

emphasize large-company (“blue chip”) stocks tend to generate<br />

more taxable dividend income than funds that emphasize smallcompany<br />

stocks.<br />

Investment policies<br />

How a mutual fund’s adviser manages the fund’s securities can<br />

also affect the taxes of shareholders in the fund. Because capital<br />

gains distributions result from the profitable sale of securities in<br />

the fund, frequent selling within a fund makes the fund more likely<br />

to produce taxable distributions than a fund that follows a strategy<br />

of “buy <strong>and</strong> hold.”<br />

9

A common measure of a mutual fund’s trading activity is its<br />

turnover rate, which is expressed as a percentage of the fund’s<br />

average net assets. For example, a fund with a 50% turnover rate<br />

has (over the course of a year) sold <strong>and</strong> replaced securities with a<br />

value equal to 50% of the fund’s average net assets. This means<br />

that, on average, the fund holds securities for two years. (The<br />

average turnover rate for U.S. stock mutual funds is about<br />

113%.*) Turnover rates can’t be used to forecast a fund’s taxable<br />

distributions, but they can help you compare the trading policies<br />

among funds. Assuming that a fund’s holdings will increase in<br />

value over time, you need to consider how much of that increase<br />

in value will be passed along to you as a taxable capital gains<br />

distribution. The fund’s turnover rate bears directly on this point.<br />

A capital gain on the sale of securities is a realized gain. In<br />

contrast, an unrealized (“paper”) gain has not yet been locked in<br />

by the sale of securities. For example, a fund may have bought<br />

stock in XYZ Inc. for $5 per share three years ago. If the stock’s<br />

price rises to $15, the fund has an unrealized capital gain of $10<br />

per share on XYZ’s stock. As long as the fund continues to hold<br />

the XYZ shares, there is no taxable gain. But if the fund actually<br />

sells the stock at $15 per share, shareholders will usually have to<br />

pay taxes on the $10 per share of realized capital gains,<br />

regardless of whether the shareholders owned their own shares<br />

in the mutual fund for a month or for a decade. Thus, all<br />

unrealized capital gains have the potential to be converted<br />

eventually into realized capital gains.<br />

This means that you should consider both a fund’s realized <strong>and</strong><br />

unrealized gains (information that is available through your<br />

mutual fund company) <strong>and</strong> also its turnover rate to determine<br />

the potential tax implications of your investment.<br />

*Source: Lipper Inc.<br />

10

When the markets move<br />

The financial markets also play a part in determining the taxable<br />

distributions a fund may pass along to you. Generally, rising<br />

markets lead to bigger gains <strong>and</strong> higher tax liabilities. (Rising<br />

markets are no cause for concern—after all, strong returns are<br />

undoubtedly the goal of every mutual fund investor.)<br />

All these factors—security holdings, investment policies, <strong>and</strong><br />

market movements—cannot reliably predict your annual tax<br />

bill. Taken together, however, they should give you a sense of<br />

whether a fund may add to that bill. The information in Figure 2<br />

may also help.<br />

Figure 2<br />

Assessing Types of <strong>Mutual</strong> <strong>Funds</strong> for Tax Friendliness<br />

Potential for Potential for<br />

Type of Fund Taxable Income Capital Gains<br />

Taxable money market High None<br />

Tax-exempt money market Very Low None<br />

Taxable bond High Low<br />

Tax-exempt bond Very Low Low<br />

State tax-exempt bond Very Low Low<br />

Balanced (stocks <strong>and</strong> bonds) Medium to High Medium<br />

Growth <strong>and</strong> income stock Medium Medium to High<br />

Growth stock Low High<br />

International stock Low High<br />

Tax-managed Low Low<br />

11

CALCULATING AND REPORTING YOUR TAXES<br />

Your mutual fund company will provide a variety of forms to help<br />

you complete your tax returns accurately. This information is also<br />

provided to the IRS. Here is a list of the various forms <strong>and</strong> how<br />

they can be used.<br />

■ IRS Form 1099-DIV, which is typically mailed by fund<br />

companies by late January of each year, lists the ordinary<br />

dividends <strong>and</strong> capital gains distributed by your funds. “Ordinary<br />

dividends” reported on Form 1099-DIV include both taxable<br />

dividends <strong>and</strong> any short-term capital gains. Form 1099-DIV<br />

may also include return-of-capital distributions <strong>and</strong> foreign<br />

taxes paid.*<br />

■ IRS Form 1099-B serves as a record of all sales of shares. Mailed<br />

in January, this form lists all of your sales of shares, checkwriting<br />

activity, <strong>and</strong> exchanges between funds. It is essential to<br />

determining capital gains or losses. If you realize capital gains<br />

or losses from the sale or exchange of mutual fund shares (or<br />

other capital assets), you must report them on your tax return.<br />

■ IRS Form 1099-R summarizes all distributions from retirement<br />

accounts such as IRAs, 401(k) plans, <strong>and</strong> annuities. Mailed in<br />

January, this form lists total distributions, the taxable amount,<br />

<strong>and</strong> any federal tax withheld.<br />

If you own shares of funds that hold U.S. Treasury securities, you<br />

may receive a United States Government Obligation listing with<br />

your Form 1099-DIV.** This provides the percentage of a fund’s<br />

income that came from U.S. government securities—<strong>and</strong> thus<br />

the percentage of income dividends that may be exempt from<br />

state income taxes.<br />

*<strong>Mutual</strong> funds that invest in foreign securities may elect to pass through foreign<br />

taxes paid by the fund to its shareholders. Shareholders may be able to claim a tax<br />

credit or deduction for their portion of foreign taxes paid.<br />

**Vanguard shareholders receive the United States Government Obligation listing.<br />

12

If you own shares of a municipal bond fund, you may receive an<br />

Income by State listing* that tells you the percentage of the fund’s<br />

income that came from each state’s obligations. You can use this<br />

information to exclude income from municipal bonds issued in<br />

the state where you live.<br />

You may also receive other tax-related information, depending<br />

on the types of funds you own. For example, if you invest in an<br />

international mutual fund, you may receive information that<br />

you can use to take a credit for foreign taxes paid by the fund.<br />

Capital gain or loss?<br />

To determine the gain or loss when you sell (or exchange)<br />

mutual fund shares, you must know both the price at which you<br />

sold the shares <strong>and</strong> your cost basis (generally the original price<br />

you paid for the shares). The sale price is the easy part. Figuring<br />

your cost basis can be complicated, especially if you bought<br />

shares at different times <strong>and</strong> at different prices.<br />

An important note: Always count reinvested dividend <strong>and</strong> capital<br />

gains distributions as part of your cost basis. This will raise your cost<br />

basis <strong>and</strong> thus reduce the amount of your taxable gain when you<br />

sell or exchange your shares. Because the size of the taxable gain<br />

will be smaller, you will owe less in taxes.<br />

When figuring your cost basis, keep in mind that any sales<br />

charge or transaction fee you pay when you buy shares is part of<br />

your cost basis. Any fees or charges paid when you sell shares<br />

reduce the proceeds of the sale. In general, fees paid when you<br />

buy or redeem shares reduce your taxable gain or increase your<br />

capital loss. (Other fees charged by a mutual fund, such as<br />

account maintenance fees, do not affect your cost basis.)<br />

The IRS allows you to figure the gain or loss on sales or exchanges<br />

of mutual fund shares by using one of four methods, each of which<br />

has its own benefits <strong>and</strong> drawbacks. Once you begin using an<br />

*Vanguard shareholders receive the Income by State listing.<br />

13

average cost method for the sale of shares of a particular fund, the<br />

IRS prohibits a switch to another method without prior approval.<br />

However, you may employ different methods for different funds.<br />

To determine which method is best for you, you may wish to<br />

consult a tax professional.<br />

First-in, first-out (FIFO)<br />

This method assumes that the shares sold were the first shares<br />

you purchased. While fairly easy to underst<strong>and</strong>, this method<br />

often leads to the largest capital gains, because the longer you<br />

hold shares, the more time they have to rise in value. If you do<br />

not specify a method for calculating your cost basis, the IRS<br />

assumes that you use the FIFO approach.<br />

14<br />

The simple approach to<br />

your cost basis<br />

Vanguard uses the average cost<br />

single category method to<br />

calculate the tax basis of shares<br />

redeemed from Vanguard fund<br />

accounts. We will send you the<br />

cost basis for each eligible<br />

investment that you sell during the<br />

year, updated on each statement<br />

you receive. (This service is not<br />

available for all accounts, such as<br />

those established before 1986 or<br />

some accounts acquired through a<br />

transfer.) See page 26 for more<br />

information on Vanguard’s average<br />

cost service.<br />

Average cost (single category)<br />

This method considers the<br />

cost basis of your mutual<br />

fund investment to be the<br />

average basis of all the shares<br />

you own—a figure that<br />

changes as you continue<br />

investing in a fund. Most<br />

mutual fund companies<br />

(including Vanguard) use<br />

this method to calculate<br />

average cost. In determining<br />

whether a sale generated a<br />

short-term gain or a longterm<br />

gain, the shares sold are<br />

considered to be the shares<br />

acquired first.<br />

Average cost (double category)<br />

This approach is similar to the single category method except<br />

that you must separate your shares into two categories—shares<br />

held for a year or less <strong>and</strong> shares held for longer than a year.

Selling short-term shares means basing the gain (which is<br />

taxed at ordinary income rates of up to 39.6%) on the difference<br />

between the average short-term basis <strong>and</strong> the sales price. By<br />

contrast, the gain on the sale of long-term shares (which is taxed<br />

at a maximum rate of 20%) is based on the difference between<br />

the average long-term basis <strong>and</strong> the sales price. If you choose<br />

this method, you must notify the fund company in advance of<br />

which category of shares to sell.<br />

Specific identification<br />

This method provides the most flexibility <strong>and</strong> therefore the best<br />

chance to minimize taxable gains. The first step is to identify the<br />

specific shares you want to sell—in most cases, these would be<br />

the shares bought at the highest price so that you can minimize<br />

your gain. However, this method is not necessarily the best<br />

choice because it can be complex <strong>and</strong> also imposes the heaviest<br />

recordkeeping burden on shareholders. In addition, the shares<br />

with the highest cost basis may be the ones you purchased most<br />

recently—which could mean your having to pay taxes at a higher<br />

rate if the gains that result are short-term.<br />

Help from the IRS<br />

More tax information is available from the Internal Revenue Service. Call the<br />

IRS at 1-800-TAX-1040 to ask questions about specific tax matters. You can<br />

order IRS forms <strong>and</strong> publications by calling 1-800-TAX-FORM. Among the<br />

publications you may find helpful in underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> reporting mutual fund<br />

taxes are:<br />

■ IRS Publication 17, Your Federal Income Tax<br />

■ IRS Publication 564, <strong>Mutual</strong> Fund Distributions<br />

■ IRS Publication 590, Individual Retirement Arrangements<br />

■ IRS Publication 514, Foreign Tax Credit for Individuals<br />

IRS forms <strong>and</strong> brochures are also available on the IRS website at<br />

www.irs.gov.<br />

15

To use the specific identification method, notify your mutual fund<br />

company in writing <strong>and</strong> provide detailed instructions about which<br />

shares you are selling each time you sell or exchange shares.<br />

Making losses work for you<br />

You can use losses on the sale of shares to offset other capital<br />

gains. You can also use up to $3,000 of net capital losses<br />

($1,500 for people who are married <strong>and</strong> filing separately) to<br />

offset ordinary income (such as salary, wages, or investment<br />

income) in any year.<br />

For example, if you have a net capital loss of $2,000 (because of<br />

unprofitable sales of mutual funds, for instance), that loss can be<br />

used to reduce your taxable income. Losses that exceed $3,000<br />

in one year can be carried forward for as long as you wish.<br />

A few cautionary notes:<br />

■ If you redeem shares at a loss <strong>and</strong> purchase shares in the<br />

same fund within 30 days before, after, or on the day of the<br />

redemption, the IRS considers the redemption a wash sale.<br />

This means that you may not be allowed to claim some or all<br />

of the loss on your tax return.<br />

■ If you redeem shares at a loss from a tax-exempt municipal<br />

bond fund by selling shares held for six months or less, a<br />

portion of the loss may not be allowed. In this case, the<br />

realized loss must be reduced by the tax-exempt income<br />

you received from these shares.<br />

■ If you realize a short-term capital loss on shares held six<br />

months or less in an account that received long-term capital<br />

gains distributions on those shares, the short-term loss you<br />

realize from a sale of shares (up to the amount of the capital<br />

gains distributions they earned) must be reported as a longterm<br />

loss.<br />

You may wish to consult with a tax adviser or tax preparer for<br />

guidance in dealing with these situations.<br />

16

T HE I MPACT OF TAXES ON<br />

YOUR I NVESTMENT RETURNS<br />

Underst<strong>and</strong>ing how mutual fund investments are taxed prepares<br />

you for the critical next step, which is to underst<strong>and</strong> the impact<br />

that taxes can have on the overall performance of your investment<br />

program. Ignoring their impact can be a serious error.<br />

Along with such fundamental factors as risk, return, <strong>and</strong> cost,<br />

taxes should be considered when deciding whether to invest in<br />

a mutual fund. Here’s why: Minimizing taxes can substantially<br />

boost the net returns you receive from mutual fund investments,<br />

particularly if you’re in a high tax bracket.<br />

According to one recent analysis, a significant portion of the pretax<br />

returns on domestic stock mutual funds ultimately goes to pay<br />

federal income tax on dividend <strong>and</strong> capital gains distributions—<br />

especially for investors in high tax brackets. Specifically, for the<br />

mutual funds included in the analysis, the average annual pre-tax<br />

return (for ten years ended December 31, 2000) was 16.1%, but<br />

the after-tax annual return was only 13.4%.* In other words, about<br />

one-sixth of the pre-tax returns was consumed by federal income<br />

tax. The amount lost to taxes for individual funds ranged from zero<br />

(the pre-tax <strong>and</strong> after-tax returns were equal) to 9.3 percentage<br />

points per year.<br />

*Source: Vanguard analysis using data from Morningstar, Inc.<br />

How Vanguard can help<br />

You can learn more about the after-tax returns on most<br />

Vanguard funds by using the After-Tax Returns Calculator<br />

on our website.<br />

This interactive tool calculates the fund’s after-tax returns based on your<br />

marginal tax rate for any time period you choose. An advanced version of the<br />

calculator can even factor in state <strong>and</strong> local income taxes.<br />

To use the calculator, go to www.vanguard.com/?aftertax.<br />

17

Over the long haul, efforts to minimize taxes can provide a<br />

h<strong>and</strong>some payoff. Figure 3 below demonstrates the growth<br />

of hypothetical taxable investments of $10,000 in two mutual<br />

funds. Both funds have pre-tax total returns of 10% a year, but<br />

their after-tax returns are different. Investors in one fund paid<br />

taxes equal to 10% of their earnings (for an after-tax return of<br />

9% a year), <strong>and</strong> investors in the other fund paid taxes equal to<br />

30% of their earnings (for an after-tax return of 7% a year).<br />

Though the advantage is not dramatic at first, it becomes huge<br />

as earnings compound over time. After 30 years, the investment<br />

with the smaller tax bite grows to almost $133,000 after taxes—<br />

about 75% more than the $76,123 produced by the more heavily<br />

taxed fund.<br />

Figure 3<br />

The Effect of <strong>Taxes</strong> Over the Long Term<br />

$140000<br />

120000<br />

100000<br />

18<br />

80000<br />

60000<br />

40000<br />

20000<br />

0<br />

$132,677<br />

9% Annual Return<br />

$76,123<br />

7% Annual Return<br />

5 10 15<br />

Years<br />

20 25 30<br />

This example, which assumes original investments of $10,000 each, is for illustrative<br />

purposes only <strong>and</strong> does not imply returns available on any particular investment.

W HAT TO D O A BOUT TAXES<br />

Because most mutual fund managers focus on maximizing<br />

pre-tax returns (within a fund’s guidelines), the important task of<br />

considering the tax effect of mutual fund investments is up to you.<br />

Several approaches can help in crafting an investment program<br />

that keeps taxes to a minimum:<br />

■ Deferring taxes on your investments for as long as possible.<br />

■ Selecting mutual funds that feature low turnover rates.<br />

■ Choosing tax-exempt investments such as municipal bond<br />

funds (for people in high tax brackets).<br />

Deferring taxes<br />

The most efficient investment strategy is to avoid taxes entirely—<br />

at least for a while. For example, mutual funds held in tax-deferred<br />

accounts (such as 401(k) <strong>and</strong> 403(b) plans, traditional IRAs, or<br />

variable annuities) are exempt from current taxation. Generally,<br />

withdrawals (both contributions <strong>and</strong> earnings) from these accounts<br />

are taxable. However, non-deductible contributions to a traditional<br />

IRA are usually not taxable when they are withdrawn.* The entire<br />

amount withdrawn from a Roth IRA is generally exempt from<br />

income taxes.<br />

On the following page, Figure 4 demonstrates the long-term<br />

benefit of delaying the payment of taxes. The “Taxable Account”<br />

column shows the value of annual $1,000 investments in a regular<br />

account on which taxes must be paid on the earnings every year.<br />

The “Tax-Deferred Account Before <strong>Taxes</strong>” column shows the<br />

value if the annual $1,000 investments are allowed to grow inside<br />

a tax-deferred account. The last column, “Tax-Deferred Account<br />

After <strong>Taxes</strong>,” shows the value of the tax-deferred account assuming<br />

*A 10% penalty tax may be levied on IRA withdrawals made before age 59 1 ⁄2.<br />

19

Figure 4<br />

The Power of Long-Term Tax Deferral<br />

Annual investments of $1,000<br />

that the account balance is withdrawn <strong>and</strong> taxes paid at the end of<br />

each period.<br />

Though the advantage of tax deferral is evident early on, the<br />

difference becomes increasingly impressive over longer periods.<br />

The tax-deferred account grows to more than $122,000 after<br />

30 years—nearly $48,000 more than the value of the taxable<br />

account over the same period. Even after taxes are paid at the<br />

end of the 30-year period, the tax-deferred account maintains an<br />

advantage of more than $17,000 over the taxable account—more<br />

than half the total investment of $30,000 over the 30-year period.<br />

The benefit of tax deferral is even greater on investments that<br />

offer additional tax advantages (such as 401(k) or 403(b) accounts,<br />

which permit pre-tax contributions). For example, in a taxable<br />

account, you would have to earn nearly $1,500 for every $1,000 of<br />

take-home pay that you plan to invest (assuming a 33% combined<br />

federal <strong>and</strong> state tax bracket). Therefore, by participating in a plan<br />

that allows pre-tax contributions, you could invest $1,500 without<br />

digging any deeper into your pocket than you would if you made<br />

a $1,000 investment after taxes.<br />

20<br />

Year-End Values<br />

Tax-Deferred Tax-Deferred<br />

Number of Taxable Account Account<br />

Years Invested Account Before <strong>Taxes</strong> After <strong>Taxes</strong><br />

10 $13,477 $ 15,645 $13,782<br />

15 23,361 29,324 24,597<br />

20 36,194 49,423 39,713<br />

25 52,854 78,954 61,149<br />

30 74,485 122,346 91,872<br />

Assumes an 8% annual rate of return <strong>and</strong> a 33% tax rate (federal <strong>and</strong> state combined). This<br />

chart should not be viewed as indicative of future investment performance. These data<br />

represent historical investment performance, which cannot be used to predict future returns.

The concept is similar for tax-deferred investments on which you<br />

may take a tax deduction, such as contributions to a traditional IRA<br />

(if you meet certain income limits). Receiving a tax deduction<br />

reduces the taxes that would otherwise be payable.<br />

Seeking low turnover<br />

Though most funds are not managed to keep taxes low, some<br />

types of mutual funds are tax-friendly by nature, especially those<br />

that keep turnover (the buying <strong>and</strong> selling of securities) low. As<br />

discussed earlier, a fund that buys <strong>and</strong> holds securities is likely to<br />

realize fewer gains than a fund that engages in active trading <strong>and</strong><br />

is thus less likely to pass along taxable gains to investors. Such<br />

funds are sometimes called tax-efficient funds.<br />

Index funds<br />

The objective of an index fund is to track the performance <strong>and</strong> risk<br />

characteristics of a market benchmark, such as the St<strong>and</strong>ard &<br />

Poor’s 500 Index. Stock index funds—but not bond index funds—<br />

can reduce an investor’s exposure to taxes.<br />

Index funds buy <strong>and</strong> hold the securities in a specific index (or a<br />

representative sample of the index). Because of this, the portfolio<br />

turnover of index funds is typically low. The chance that a security<br />

held in an index fund will be sold for a large gain (thus generating<br />

a large tax bill for shareholders) is much lower than a fund that<br />

employs an active management approach (buying <strong>and</strong> selling<br />

securities at the fund manager’s discretion).<br />

Nonetheless, index funds do sometimes realize gains—for example,<br />

when a stock is removed from a fund’s target index <strong>and</strong> thus must<br />

be sold by the fund. An index fund could also be forced to sell<br />

securities in its portfolio if many investors decide to sell their<br />

shares—say, during a downturn in the stock market.<br />

Bond index funds do not offer a tax-efficiency edge over actively<br />

managed bond funds because income—not capital gains—<br />

typically accounts for almost all of the long-term total return<br />

from bond funds.<br />

21

Tax-managed funds<br />

Some funds are managed to keep taxable gains <strong>and</strong> income low.<br />

Among the strategies these funds employ are indexing (to hold down<br />

turnover), carefully selecting which shares to sell (so that capital<br />

losses offset most capital gains), <strong>and</strong> encouraging long-term<br />

investing (for example, by assessing fees on shareholders who<br />

redeem their shares soon after buying them).<br />

Investing for tax-exempt income<br />

Interest on most municipal bonds is exempt from federal income<br />

tax <strong>and</strong>, in some cases, from state <strong>and</strong> local income taxes as well.<br />

However, municipal bond funds (which pay lower yields than<br />

taxable bond funds as the trade-off for their tax advantage) are not<br />

for everyone. Generally, investors in lower tax brackets do not<br />

benefit from owning municipal bond funds. The box below explains<br />

how to compare yields on tax-exempt <strong>and</strong> taxable bond funds.<br />

22<br />

Choose your bonds—taxable or tax-exempt?<br />

Deciding between taxable <strong>and</strong> tax-exempt bond funds for your portfolio takes<br />

some analysis. Municipal bonds offer the advantage of producing income<br />

that is exempt from taxes—but they also pay yields lower than those<br />

available on taxable bond funds of comparable quality <strong>and</strong> maturity. To<br />

decide whether to invest in a tax-exempt bond fund or a taxable one, you<br />

need to know which provides the best overall return.<br />

Here is how to compare the yield of a municipal bond fund with that of a<br />

taxable bond fund that holds bonds of similar credit quality <strong>and</strong> maturities.<br />

First subtract the percentage of your marginal tax bracket from 1, then<br />

divide the resulting number into the yield of the tax-exempt fund to find the<br />

equivalent taxable yield. For an investor in the 28% tax bracket considering a<br />

tax-exempt fund with a 6% yield, the calculation is as follows:<br />

Example: 1.0 – 0.28 = 0.72 6% ÷ 0.72 = 8.33%<br />

In this example, a taxable fund must provide a yield of more than 8.33% to<br />

top a yield of 6% from a tax-exempt fund.

Keep in mind that only a municipal bond’s income is exempt from<br />

taxes. <strong>Taxes</strong> are payable on any capital gains that a tax-exempt<br />

fund distributes. And for some investors, a portion of the fund’s<br />

income may be subject to the alternative minimum tax.<br />

State-specific municipal bond funds provide an additional tax<br />

advantage. Municipal bond income is generally exempt from<br />

both state <strong>and</strong> federal taxes for investors who live in the state<br />

where the bonds are issued. For example, New York State<br />

residents pay no state taxes on income from a municipal bond<br />

fund that holds only securities of New York State issuers.<br />

23

TAX-EFFICIENT VANGUARD F UNDS<br />

Vanguard underst<strong>and</strong>s that taxes are an important consideration<br />

for all investors. To address that concern, we offer a wide variety<br />

of funds that may be suitable for tax-conscious investors.<br />

Vanguard ® Municipal Bond <strong>Funds</strong><br />

High-Yield Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Intermediate-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Limited-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Short-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

Vanguard ® State Tax-Exempt Income <strong>Funds</strong><br />

California Insured Intermediate-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

California Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

California Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

Florida Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Massachusetts Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

New Jersey Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

New Jersey Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

New York Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

New York Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

Ohio Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Ohio Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

Pennsylvania Insured Long-Term Tax-Exempt Fund<br />

Pennsylvania Tax-Exempt Money Market Fund<br />

24

Vanguard ® Index <strong>Funds</strong><br />

Vanguard ® Domestic Stock Index <strong>Funds</strong><br />

500 Index Fund<br />

Balanced Index Fund<br />

Calvert Social Index Fund<br />

Extended Market Index Fund<br />

Growth Index Fund<br />

Mid-Cap Index Fund<br />

Small-Cap Growth Fund<br />

Small-Cap Index Fund<br />

Small-Cap Value Index Fund<br />

Total Stock Market Index Fund<br />

Value Index Fund<br />

Vanguard ® International Stock Index <strong>Funds</strong><br />

Developed Markets Index Fund<br />

Emerging Markets Stock Index Fund<br />

European Stock Index Fund<br />

Pacific Stock Index Fund<br />

Total International Stock Index Fund<br />

Vanguard ® Tax-Managed <strong>Funds</strong><br />

Tax-Managed Balanced Fund<br />

Tax-Managed Capital Appreciation Fund<br />

Tax-Managed Growth <strong>and</strong> Income Fund<br />

Tax-Managed International Fund<br />

Tax-Managed Small-Cap Fund<br />

25

VANGUARD’ S TAX I NFORMATION S ERVICES<br />

If figuring your taxes already includes more calculations than<br />

you’d like, several Vanguard services can make tracking <strong>and</strong><br />

reporting taxes easier.<br />

Average Cost Service<br />

If you sell or exchange shares of any Vanguard fund that has a<br />

fluctuating share value, you will receive an Average Cost Statement<br />

that lists the average cost basis (using the single category method)<br />

of the shares you sold or exchanged. In addition, the statement lists<br />

the proceeds from each sale <strong>and</strong> the amount of any gain or loss.<br />

Each sale is classified as either a short-term or a long-term gain or<br />

loss. This service simplifies tax reporting <strong>and</strong> recordkeeping. Note<br />

that using a different method of calculating your cost basis could<br />

change the amount of taxes that you owe. Consult your tax adviser<br />

for further information.<br />

Information on your Average Cost Statement is not reported<br />

to the IRS, <strong>and</strong> you are not required to use it to calculate your<br />

capital gains or losses. However, if you use one of the three other<br />

methods (as described on pages 14 <strong>and</strong> 15), you must keep<br />

careful records for purchases <strong>and</strong> sales. Remember that while<br />

Form 1099-B provides information about sales, it does not show<br />

the cost basis for the shares.<br />

26<br />

How Vanguard can help<br />

Vanguard can give you daily updates on the cost basis of<br />

your shares.<br />

For example, if you’re considering a sale, you may want to check your<br />

average cost basis as of the previous day’s market closing price. Compare<br />

that figure with the current market value of your shares to estimate the<br />

tax implications of a sale.<br />

For assistance, call Vanguard ® Client Services at 1-800-662-2739.

Information for state tax returns<br />

In January, Vanguard provides a breakdown of the percentage<br />

of income that each Vanguard fund derives from direct U.S.<br />

Treasury obligations (such as U.S. Treasury bills, notes, or<br />

bonds). This information allows you to exclude that percentage<br />

of the income you earned from the income subject to state tax.<br />

Also in January, Vanguard furnishes shareholders of municipal<br />

bond funds a list of the percentage of the fund’s income derived<br />

from each state. Use this information to exclude from your tax<br />

return any income attributable to municipal bonds issued in the<br />

state where you live.<br />

Foreign Tax Credit Service<br />

Vanguard’s Foreign Tax Credit Service provides detailed tax<br />

information in January for all shareholders of Vanguard mutual<br />

funds that hold primarily international investments. A mutual<br />

fund that invests in stocks of overseas companies may have to<br />

pay foreign taxes on the dividends it receives. If this happens,<br />

you may either deduct your share of the foreign tax on your<br />

U.S. income tax return or claim a credit for it. (Claiming a<br />

credit is usually more advantageous, because a deduction only<br />

reduces your taxable income, while a credit reduces the tax you<br />

owe dollar-for-dollar.)<br />

This information specifies the foreign income you earned as well<br />

as the foreign taxes you paid. If you claim a credit, you can use<br />

this information to complete IRS Form 1116, Foreign Tax Credit.<br />

(Some shareholders may be able to claim a credit directly on Form<br />

1040 without completing Form 1116; check with your tax adviser.)<br />

You may receive a credit or deduction for foreign taxes only on<br />

funds you hold in taxable accounts. International investments<br />

held in a tax-deferred account such as an IRA are not eligible<br />

for a tax credit or deduction. If you are eligible to receive a credit<br />

or deduction for any of your fund investments, Vanguard will<br />

send you the appropriate information.<br />

27

A VANGUARD I NVITATION<br />

For more information about Vanguard ® funds <strong>and</strong> services,<br />

to learn more about investing, or to open an account online,<br />

visit our website at www.vanguard.com. There you’ll find the<br />

complete Plain Talk ® Library, Retirement Center, <strong>and</strong> our<br />

popular Education Center. Register for immediate secure<br />

access to our online investment-management center, <strong>and</strong><br />

you can monitor your accounts, conduct transactions, trade<br />

securities, <strong>and</strong> invest in both Vanguard <strong>and</strong> non-Vanguard<br />

funds—24 hours a day.<br />

Or you can speak with a Vanguard associate by calling us at<br />

1-800-662-7447 on business days from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. <strong>and</strong><br />

on Saturdays from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Eastern time. Our associates<br />

are always pleased to answer your questions or provide<br />

information about our funds <strong>and</strong> services.<br />

Vanguard also invites you to take advantage of the broad<br />

selection of programs <strong>and</strong> services that we offer that can teach<br />

you more about investing <strong>and</strong> help you stay on track toward<br />

reaching your financial goals.<br />

Vanguard ® Personal Financial Planning Service 1-800-567-5162<br />

At an affordable fee, this service offers customized one-time<br />

analysis <strong>and</strong> advice on investment, retirement, <strong>and</strong> estate planning.<br />

Vanguard ® Asset Management <strong>and</strong> Trust Services 1-800-567-5163<br />

Individuals who have a minimum of $500,000 in investable assets<br />

can receive comprehensive, ongoing wealth management services<br />

at a very reasonable fee.<br />

28

Vanguard Brokerage Services ® 1-800-992-8327<br />

Through Vanguard Brokerage, you can invest in individual stocks,<br />

bonds, options, <strong>and</strong> more than 2,600 non-Vanguard mutual funds.<br />

You can open an account <strong>and</strong> trade on our website as well.<br />

Retirement Resource Center 1-800-205-6189<br />

Our experienced retirement specialists can provide a wealth<br />

of information to help you plan or manage your retirement<br />

investments.<br />

Individual Retirement Plans 1-800-823-7412<br />

Self-employed individuals <strong>and</strong> small-business owners can find out<br />

how to establish <strong>and</strong> administer retirement plans for themselves<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or their employees.<br />

Voyager <strong>and</strong> Flagship Services 1-800-337-8476<br />

Vanguard offers special services for clients with substantial assets.<br />

■ Voyager Service ® , for clients investing more than $250,000 in Vanguard<br />

mutual funds, offers the expert assistance of a special service team.<br />

■ Flagship Service, for clients whose Vanguard mutual fund investments<br />

exceed $1 million, offers personal service from a dedicated representative.<br />

Eligible clients are invited to call Vanguard for more information.<br />

29

G LOSSARY<br />

Active management<br />

Portfolio management that seeks to exceed the returns of the<br />

financial markets. Active fund managers rely on research,<br />

market forecasts, <strong>and</strong> their own judgment <strong>and</strong> experience in<br />

making investment decisions.<br />

Alternative minimum tax (AMT)<br />

The AMT is a tax intended to ensure that taxpayers who<br />

receive certain tax benefits (such as tax-exempt interest from<br />

private activity bonds, accelerated depreciation deductions, <strong>and</strong><br />

incentive stock options) pay their fair share of income taxes<br />

despite tax benefits. Taxpayers must first calculate regular<br />

taxable income, then add back tax adjustments <strong>and</strong> preferences<br />

to determine the AMT. If the AMT is higher than the regular<br />

tax liability, the taxpayer must pay the AMT.<br />

Capital gains distribution<br />

Payment to mutual fund shareholders of net gains realized<br />

during the year on securities that have been sold at a profit.<br />

Capital gains are distributed on a “net” basis—that is, after<br />

subtracting any capital losses for the year. If losses exceed<br />

gains for the year, the difference may be carried forward <strong>and</strong><br />

subtracted from the fund’s future gains.<br />

Cost basis<br />

For tax purposes, the original cost of an investment, including any<br />

reinvested dividend or capital gains distributions. Cost basis may<br />

include adjustments such as increases for transaction fees paid at<br />

purchase or decreases for return-of-capital distributions. It is<br />

subtracted from the sales price to determine any capital gain<br />

or loss from the sale of mutual fund shares or other securities.<br />

30

Declared<br />

When the Board of Directors of a mutual fund announces the<br />

amount <strong>and</strong> date of a dividend or capital gains distribution, the<br />

distribution is said to have been declared. A declared distribution<br />

is payable to the shareholders of record as of the record date.<br />

Dividend yield<br />

The annualized rate at which an investment pays dividends,<br />

expressed as a percentage of the investment’s current price.<br />

Growth stocks<br />

Stocks of companies with a strong potential for earnings<br />

growth. They are likely to generate much of their total return<br />

in the form of capital gains rather than dividend income.<br />

Income distribution<br />

Interest <strong>and</strong> dividends earned on securities held by a mutual<br />

fund <strong>and</strong> paid out to shareholders (after reduction for fund<br />

expenses) in the form of dividends.<br />

Index<br />

Statistical benchmarks designed to reflect changes in segments<br />

of the financial markets or the economy. In investing, indexes<br />

are used to measure changes in segments of the stock <strong>and</strong> bond<br />

markets <strong>and</strong> as st<strong>and</strong>ards against which fund managers <strong>and</strong><br />

investors can measure the performance of their investment<br />

portfolios. You cannot invest in an index.<br />

Indexing<br />

An investment management approach in which a mutual fund<br />

seeks to track the performance of a specific financial market<br />

benchmark, or index, by holding all the securities that compose<br />

the market segment (or a statistically representative sample of the<br />

index).<br />

Marginal tax rate<br />

The income tax rate at which the last dollar of your income is<br />

taxed. Under federal law, you often pay a lower tax rate on your<br />

31

first dollar of taxable income than you do on your last dollar.<br />

The marginal rate—the highest rate at which your income is<br />

taxed—is used to calculate taxes due on investment income.<br />

Net asset value (NAV)<br />

The value of a mutual fund’s assets, after deducting liabilities,<br />

divided by the number of shares currently outst<strong>and</strong>ing. NAV is<br />

expressed as the value of a single share in the fund <strong>and</strong> is reported<br />

daily in many newspapers.<br />

Ordinary income<br />

Ordinary income includes earned income (such as wages, salaries,<br />

<strong>and</strong> self-employment income), unearned income (such as taxable<br />

interest <strong>and</strong> dividends), <strong>and</strong> other income (such as taxable refunds<br />

of state income taxes). Ordinary income is taxed at higher rates<br />

than long-term capital gains.<br />

Record date<br />

The deadline for owning shares of a fund for the purpose of<br />

receiving the next distribution of dividends or capital gains. All<br />

investors who own shares on the record date receive a distribution<br />

<strong>and</strong> owe taxes on it, regardless of how long they have owned the<br />

shares. By buying shares after the record date, investors can avoid<br />

the distribution <strong>and</strong> resulting taxes.<br />

Return of capital<br />

When a mutual fund’s distributions exceed its earnings <strong>and</strong><br />

profits, the excess is considered a return of capital (or return of<br />

basis). That part of the distribution is generally not taxable<br />

because it represents a portion of the original investment being<br />

returned. The effect of a return of capital is to reduce basis in<br />

the investment, which may cause future capital gains to be<br />

higher. If a shareholder’s basis is eliminated by return-of-capital<br />

distributions, any excess is treated as a capital gain.<br />

Tax-deferred account<br />

An investment vehicle that shields earnings from taxes. These<br />

types of accounts include 401(k) plans, 403(b) plans, IRAs, <strong>and</strong><br />

32

variable annuities. Although mutual funds held in these accounts<br />

are not taxed currently, they are subject to federal <strong>and</strong> state taxes<br />

upon withdrawal (except for qualified distributions from Roth<br />

IRAs <strong>and</strong> Education IRAs <strong>and</strong> withdrawals of non-deductible<br />

contributions to traditional IRAs).<br />

Tax-efficient fund<br />

A fund that generates low taxable income for its shareholders<br />

is said to be tax-efficient.<br />

Tax-exempt bond<br />

A bond whose interest payments are not subject to income tax.<br />

The interest on bonds issued by municipal, county, <strong>and</strong> state<br />

governments <strong>and</strong> agencies is typically exempt from federal<br />

income tax <strong>and</strong> may also be exempt from state or local income<br />

taxes. Tax-exempt bonds are also called municipal bonds or<br />

tax-free bonds.<br />

Turnover rate<br />

A measure of a mutual fund’s trading activity. Turnover is<br />

calculated by taking the lesser of the fund’s total purchases or sales<br />

of securities (not counting securities with maturities under one<br />

year) <strong>and</strong> dividing by the average monthly assets. A turnover rate<br />

of 50% means that, during the year, a fund has sold <strong>and</strong> replaced<br />

securities with a value equal to 50% of the fund’s average net assets.<br />

Value stocks<br />

Stocks of companies with good long-term prospects but whose<br />

current prices are considered low given the companies’ assets or<br />

profit potential. These stocks tend to pay above-average dividends,<br />

so much of the total return from value funds comes in the form of<br />

ordinary income rather than capital gains.<br />

Wash sale rule<br />

IRS regulation that prohibits a taxpayer from claiming a loss<br />

on the sale of a security (such as stock, bond, or mutual fund<br />

shares) if that same security is purchased within 30 days before<br />

or after—or on the same day of—the sale.<br />

33

Invest with a leader<br />

The Vanguard Group traces its roots to the opening of its first mutual<br />

fund, Wellington Fund, in 1929. The nation’s oldest balanced fund,<br />

Wellington Fund emphasized conservatism <strong>and</strong> diversification in an<br />

era of rampant market speculation. Despite its creation just before the<br />

worst years in U.S. financial history, Wellington Fund prospered <strong>and</strong><br />

within a generation was one of the largest mutual funds in the nation.<br />

The Vanguard Group was launched in 1975 solely to serve the<br />

Vanguard mutual funds <strong>and</strong> their shareholders. From its start as a<br />

single fund in an infant industry, Vanguard has become one of the<br />

largest investment management firms in the world. Today, some<br />

$550 billion is invested with us in more than 100 investment portfolios.<br />

And some 11,000 crew members now serve millions of shareholders<br />

who have entrusted their investment assets—indeed, their financial<br />

future—to a company that they believe offers the best combination of<br />

investment performance, service, <strong>and</strong> value in the industry.<br />

35

Calvert Group ® <strong>and</strong> Calvert<br />

Social Index are trademarks of<br />

Calvert Group, Ltd., <strong>and</strong> have<br />

been licensed for use by The<br />

Vanguard Group, Inc. Vanguard ®<br />

Calvert Social Index Fund is not<br />

sponsored, endorsed, sold, or<br />

promoted by Calvert Group, Ltd.,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Calvert Group, Ltd., makes no<br />

representation regarding the<br />

advisability<br />

of investing in the fund.<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ard & Poor’s ® , S&P ® ,<br />

S&P 500 ® , St<strong>and</strong>ard & Poor’s<br />

500, <strong>and</strong> 500 are trademarks<br />

of The McGraw-Hill Companies,<br />

Inc., <strong>and</strong> have been licensed for<br />

use by The Vanguard Group, Inc.<br />

Vanguard mutual funds are not<br />

sponsored, endorsed, sold, or<br />

promoted by St<strong>and</strong>ard & Poor’s,<br />

<strong>and</strong> St<strong>and</strong>ard & Poor’s makes<br />

no representation regarding<br />

the advisability of investing<br />

in the funds.<br />

Vanguard funds <strong>and</strong> non-<br />

Vanguard funds offered through<br />

our FundAccess ® program<br />

are offered by prospectus only.<br />

Prospectuses contain more<br />

complete information on risks,<br />

advisory fees, distribution<br />

charges, <strong>and</strong> other expenses<br />

<strong>and</strong> should be read carefully<br />

before you invest or send money.<br />

Prospectuses for Vanguard funds<br />

can be obtained directly from The<br />

Vanguard Group; prospectuses<br />

for non-Vanguard funds offered<br />

through FundAccess can be<br />

obtained from Vanguard<br />

Brokerage Services, 1-800-992-<br />

8327.<br />

Vanguard Brokerage Services<br />

is a division of Vanguard<br />

Marketing Corporation.<br />

Post Office Box 2600<br />

Valley Forge, PA 19482-2600<br />

World Wide Web<br />

www.vanguard.com<br />

Toll-Free<br />

Investor Information<br />

1-800-662-7447<br />

Printed on recycled paper.<br />

© 2001 The Vanguard Group, Inc.<br />

All rights reserved.<br />

Vanguard Marketing<br />

Corporation, Distributor.<br />

BTAX 032001