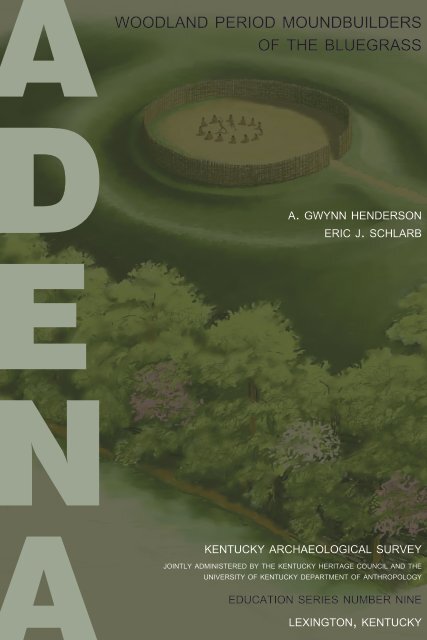

woodland period moundbuilders of the bluegrass - Kentucky ...

woodland period moundbuilders of the bluegrass - Kentucky ...

woodland period moundbuilders of the bluegrass - Kentucky ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

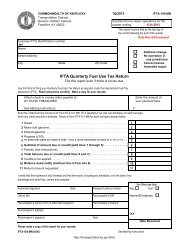

Over time, <strong>the</strong>se people will return to this mound. They will buryo<strong>the</strong>r important members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir communities here, and <strong>the</strong>y will covereach burial with earth. In this way, <strong>the</strong> mound will grow in height andmass.After some time, <strong>the</strong>y will bury <strong>the</strong> last person, <strong>the</strong>n cover <strong>the</strong> wholemound with a layer <strong>of</strong> clean soil. Although no longer an active cemetery,<strong>the</strong> mound is still a prominent feature on <strong>the</strong> landscape and a place <strong>of</strong>OhioIndianaColumbusCincinnatiLexingtonHuntingtonW. Virginia<strong>Kentucky</strong>Adena CultureThe Adena Culture extended across parts <strong>of</strong> sou<strong>the</strong>rn Ohio, westernVirginia, and central and eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>.rituals. For several generations, <strong>the</strong> people will hold ceremonies on <strong>the</strong>mound’s summit.And <strong>the</strong>n, after more time has passed, no one in living memory willhave attended ceremonies <strong>of</strong> any kind at <strong>the</strong> mound. Two hundred yearsafter building <strong>the</strong> enclosure, prehistoric people will not worship incircular enclosures or build burial mounds. But <strong>the</strong>y will remember <strong>the</strong>sesacred places.**********Today, from that same ridgecrest, <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> horizon is stillunbroken. The rolling Bluegrass landscape stretches out in everydirection. The tall ear<strong>the</strong>n mound, now covered with wild flower-fleckedhay, is still <strong>the</strong>re. It does not stand quite as tall as it did when newlycovered with its final soil mantle. Erosion has done its work.3

The preceding story is based on information archaeologists uncoveredat a Bath County mound and what anthropologists know aboutmoundbuilding peoples worldwide. We do not know how closely itdescribes what took place at <strong>the</strong> mound, just as we do not know <strong>the</strong> namethose prehistoric <strong>moundbuilders</strong> called <strong>the</strong>mselves. Today, archaeologistscall <strong>the</strong>m Adena (Uh-DEE-nuh), after an estate <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> same name insouth-central Ohio where researchers first excavated an Adena mound.These mobile hunting-ga<strong>the</strong>ring-gardening peoples lived in <strong>the</strong> middleOhio River valley between 2500 and 1800 years ago. Over this long<strong>period</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y built thousands <strong>of</strong> burial mounds and scores <strong>of</strong> geometricearthworks. Their mounds were <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir social, economic, andreligious lives, and <strong>the</strong> physical expression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir beliefs about <strong>the</strong>world and <strong>the</strong>ir place in it.A.D. 2000A.D. 1000Euro-americansMississippianWoodland1000 B.C.Archaic8000 B.C.Paleoindian12000 B.C.The Adena Culture flourished during <strong>the</strong> Middle Woodland <strong>period</strong>.The mound in <strong>the</strong> background once stood in Bath County.

However, Adena people kept no written records. Their stories havebeen lost to time, so we must learn about <strong>the</strong>m indirectly.Much <strong>of</strong> what we know comes from <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> archaeologists. Theseresearchers are piecing toge<strong>the</strong>r a picture <strong>of</strong> Adena culture by studying<strong>the</strong> places <strong>the</strong>y once lived, <strong>the</strong> mounds <strong>the</strong>y built, and <strong>the</strong> patterns <strong>of</strong>objects <strong>the</strong>y left behind. This booklet presents our current ideas aboutwhat <strong>the</strong>ir day-to-day lives and burial practices were like around 2000years ago. It is based on research carried out at eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>Adena campsites, and at Adena mounds and earthworks in <strong>Kentucky</strong>’sBluegrass region.Adena moundInner BluegrassOuter BluegrassAdena mounds and earthworks are scattered acrosscentral <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s Bluegrass region.5

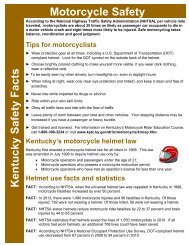

MOUNDBUILDERS, RELIEF CREWS, AND ARCHAEOLOGISTSIn <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass region, people have recorded and studied Adenamounds and earthworks for over 200 years. Our understanding <strong>of</strong> Adenaculture, however, has depended on an assortment <strong>of</strong> events, discoveries,and characters.The Moundbuilder MythDuring <strong>the</strong> late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-centuries, Adenamounds and earthworks stirred <strong>the</strong> imagination <strong>of</strong> European explorers,pioneers, and travelers heading west <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Appalachian Mountains.A few were moved to action. Constantine Rafinesque, a naturalist andpr<strong>of</strong>essor at Transylvania University, made detailed drawings anddescribed several central <strong>Kentucky</strong> examples.They all wondered: “Who built <strong>the</strong>se mounds?” Historians andscholars hotly debated this question throughout <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century. Itmay seem strange to us today, but many seriously credited <strong>the</strong> Egyptians,Mongols, or Welsh.O<strong>the</strong>rs thought a vanished race, <strong>the</strong> Moundbuilders, had built <strong>the</strong>m.They believed that <strong>the</strong> ancestors <strong>of</strong> living American Indian peoples hadbeen brutal savages. In <strong>the</strong>ir minds, <strong>the</strong>se people could not possibly havebuilt mounds - <strong>the</strong>y drove <strong>of</strong>f or killed <strong>the</strong> ‘real’ Mound builders. It alsodid not help that nineteenth-century native peoples with historic links to<strong>the</strong> Ohio Valley lacked direct recollections or stories, myths, and legends<strong>of</strong> moundbuilding.The crew (and dog!) pause for a photograph during work at a Montgomery County mound.

As people debated <strong>the</strong> Moundbuilders’ identity, <strong>the</strong> mounds<strong>the</strong>mselves were disappearing at an alarming rate. Farmers were clearing<strong>the</strong> land and planting crops. America’s cities and towns were growing.Relic hunters were looting <strong>the</strong> largest mounds for <strong>the</strong> objects inside<strong>the</strong>m. Wealthy, well-meaning individuals, doing what <strong>the</strong>y thoughtwas increasing scientific knowledge, were actually destroying moreinformation than <strong>the</strong>y recovered.Map <strong>of</strong> a Montgomery County Adena mound and earthwork complex.Based on a Rafinesque survey, it was published by Squier and Davis.Two surveyors, Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis, were an exceptionto <strong>the</strong> wealthy antiquarians. They accurately recorded many Ohio Valleyprehistoric mounds and earthworks, including several examples in <strong>the</strong>Bluegrass region. The Smithsonian Institution published <strong>the</strong>ir researchin 1848. Locally, Robert Peter, a distinguished Lexington physician,investigated <strong>the</strong> mounds and earthworks on his farm near Elkhorn Creek.Geologist J. B. Hoeing also carefully marked <strong>the</strong> locations <strong>of</strong> ear<strong>the</strong>nburial mounds on his maps as he surveyed Bluegrass bedrock formations.As <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century ended, research funded by <strong>the</strong> federalgovernment finally laid <strong>the</strong> Moundbuilder myth to rest. Teams <strong>of</strong> mensurveyed and excavated many mounds in <strong>the</strong> Midwest and Sou<strong>the</strong>ast,including several in <strong>the</strong> Ohio Valley. Their work, analyzed and publishedby Cyrus Thomas in 1894, showed through artifacts and soil stratigraphythat <strong>the</strong> ancestors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> American Indians built <strong>the</strong> mounds.7

An archaeologist carefullyremoves soil fromnear a broken Adenaceramic jar. Aluminumfoil pouches nearby holdcharred wood samplesfor radiocarbon dating.The next four decades witnessed <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> research focusedon <strong>the</strong> Adena culture. Investigators outside <strong>Kentucky</strong> studied Adenaburial mounds and began to recognize <strong>the</strong>ir unique features. In <strong>Kentucky</strong>,William S. Webb and William D. Funkhouser, University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kentucky</strong>physics and biology pr<strong>of</strong>essors, published a county-by-county list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>state’s prehistoric sites. Many Bluegrass sites were Adena mounds.Depression-Era ArchaeologyDuring <strong>the</strong> Great Depression (1929-1941), thousands <strong>of</strong> Kentuckianswere desperate for work. Some found it excavating prehistoric villages,shell heaps, mounds, and earthworks through federal relief programs.William S. Webb, founder <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s newDepartment <strong>of</strong> Archaeology and Anthropology, directed <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kentucky</strong>program.Excavations took place in <strong>the</strong> counties hardest-hit by <strong>the</strong> saggingeconomy. Sites chosen for excavation were <strong>of</strong>ten ones that had a goodchance <strong>of</strong> being vandalized, although <strong>the</strong> desires <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sponsoringagencies also played a part in <strong>the</strong> selection process. From 1934-1942 in<strong>the</strong> Bluegrass counties <strong>of</strong> Bath, Boone, Fayette, and Montgomery alone,federal relief programs funded excavations at 17 Adena mounds andearthworks.These projects represented <strong>the</strong> first sustained research efforton <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s Adena sites. Some <strong>of</strong> America’s brightest young8

archaeologists supervised <strong>the</strong> excavations. They used <strong>the</strong> most modernscientific techniques <strong>the</strong>n available.During <strong>the</strong> peak years <strong>of</strong> 1938-1939, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Kentucky</strong> program employedalmost 300 people each month. Activities focused on documentingpits, hearths, posts, burials, and soil layers, and on recovering as manyartifacts as possible. Crews excavated year-round under all sorts <strong>of</strong>wea<strong>the</strong>r conditions. Work on some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest Adena mounds tookalmost two years to complete.In 1941, America entered World War II. The federal relief programsstopped soon after, thus ending <strong>the</strong> era <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most intensive work everundertaken, before or since, at <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s Adena sites.The significance <strong>of</strong> Depression-era investigations at <strong>Kentucky</strong>’sAdena mounds and earthworks cannot be understated. These make-workprojects were revolutionary, given <strong>the</strong> enormous amount <strong>of</strong> informationrecovered. Without that information, our understanding <strong>of</strong> Adena culturetoday would be severely limited.The University <strong>of</strong> <strong>Kentucky</strong>’s William S. Webb Museum <strong>of</strong>Anthropology in Lexington still carefully curates all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> artifacts,photographs, notes, maps, and drawings from <strong>the</strong>se projects. Thesematerials continue to provide data for new generations <strong>of</strong> scholars.Adena Research TodayBy <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> World War II, Webb and his colleagues had written<strong>the</strong> bulk <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir reports on <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass region’s Adena moundsand earthworks. In <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>y described <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>irinvestigations.They also attempted to interpret some <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong>yhad found. Understandably, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se interpretationshave changed over <strong>the</strong> years. For example, Webb ando<strong>the</strong>rs thought that <strong>the</strong> circular patterns <strong>of</strong> paired postsdocumented beneath some burial mounds representedhouses. We know today that <strong>the</strong>y were ritual structures.In <strong>the</strong> 1950s, radiocarbon dating (a techniquethat dates a previously living thing by measuring<strong>the</strong> decay <strong>of</strong> C14, a radioactive isotope <strong>of</strong> carbon)revolutionized archaeology. It provided a new wayfor archaeologists to measure time. Now it wasfinally possible to consider exactly when <strong>the</strong> Adenaculture flourished and how it had changed during its700-year long history.9an Adena spearpoint witha short stem

Since <strong>the</strong> Depression era, <strong>the</strong> pace <strong>of</strong> Adena mound research in <strong>the</strong>Bluegrass has slowed, but it has not stopped. Archaeologists are stillrecording and describing new mounds. They excavate <strong>the</strong>m only rarely,for example, when modern construction projects cannot avoid <strong>the</strong>m. In2006, archaeologists got <strong>the</strong>ir first glimpse <strong>of</strong> an Adena <strong>of</strong>f-mound ritualarea. It was near a Montgomery County burial mound that archaeologistshad recorded in 1932.Although research today builds on <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong> Webb and hiscolleagues, archaeologists have moved beyond simply describing what<strong>the</strong>y find. Their goals are to interpret and understand all aspects <strong>of</strong>Adena life. For <strong>the</strong> past thirty years, native son Dr. R. Berle Clay hasresearched Adena burial ritual. He has drawn on <strong>the</strong> findings <strong>of</strong> his ownexcavations, but has relied equally on Depression-era materials. His workhas shown how complex and diverse Adena burial practices were. O<strong>the</strong>rinvestigators have begun to study how Adena people gotcopper from distant places, research that also depends onmaterials curated at <strong>the</strong> William S. Webb Museum.Archaeologists now recognize that a fullunderstanding <strong>of</strong> Adena culture will depend onknowing more about peoples’ day-to-day lives.Thus, some have begun to research <strong>the</strong> placesAdena people once lived. They are using newtechniques to collect new kinds <strong>of</strong> information.For example, a technique developed in <strong>the</strong>1970s, called flotation, recovers charred foodremains from soil using water separation. Nowarchaeologists study <strong>the</strong> kinds <strong>of</strong> plants Adenapeoples grew, ate, and used at home and in<strong>the</strong>ir ceremonies. We really have only begunto learn about Adena people: <strong>the</strong>ir domesticlife, <strong>the</strong>ir foodways, <strong>the</strong>ir biology anddiseases, where <strong>the</strong>y lived and why, and <strong>of</strong>course, <strong>the</strong>ir fascinating ritual lives.an Adena spearpoint with a rounded stem10

DAILY LIFEAdena lifeways were firmly rooted in those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rerancestors. Yet, <strong>the</strong>ir lives were different in several very important ways.Adena peoples depended more heavily on <strong>the</strong> plants <strong>the</strong>y grew for food.Unlike <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors, <strong>the</strong>y made containers from locally available clays,built geometric earthworks, and buried some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir dead in mounds.Archaeologists know much less about Adena daily life than <strong>the</strong>y doabout Adena burial practices. This is because archaeologists have onlystudied a few <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> places Adena people once lived.Sometimes <strong>the</strong>ycooked <strong>the</strong>ir food inearth ovens: deeppits <strong>the</strong>y filled withhot rocks or coals.We can infer much about Adena daily life by studying <strong>the</strong>contemporary campsites <strong>of</strong> groups who lived in eastern <strong>Kentucky</strong>. Thewell-preserved, but much earlier, campsites <strong>of</strong> hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rer groups inwest-central <strong>Kentucky</strong> also can <strong>of</strong>fer insights. Information about <strong>the</strong> lives<strong>of</strong> modern and prehistoric hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rers in o<strong>the</strong>r places in <strong>the</strong> worldhelps, too.Society and PoliticsLife in Adena times, as it had in <strong>the</strong> past, revolved around family.Between 15 and 20 people probably made up an extended family. Thiswould have consisted <strong>of</strong> a man, a woman, and <strong>the</strong>ir unmarried children;<strong>the</strong>ir married children, <strong>the</strong>ir spouses, and children; and perhaps a fewo<strong>the</strong>r close kin. Several extended families formed a lineage or clan.People chose spouses from lineages/clans o<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong>ir own.11

arite boatstonePeople from perhaps as many as four to six differentlineages/clans would have formed an Adena social group.Kinship ties <strong>of</strong> birth and marriage would have knitted<strong>the</strong>se groups toge<strong>the</strong>r. They probably met with each o<strong>the</strong>rthroughout <strong>the</strong> year: to socialize, to trade, and to take partin ceremonies at <strong>the</strong> mounds. In times when food wasscarce or when enemies threatened, <strong>the</strong>y could depend oneach o<strong>the</strong>r for help.Every kin-based lineage/clan had its own leader. Like hunting andga<strong>the</strong>ring societies today, <strong>the</strong>se could have been men who were <strong>the</strong> mostsuccessful hunters or traders, or men o<strong>the</strong>rs respected for <strong>the</strong>ir commonsense or intelligence.Adena leaders probably led by consent. When <strong>the</strong> need arose, <strong>the</strong>ysettled arguments between <strong>the</strong>ir own lineage/clan members, and alsothose between members <strong>of</strong> different lineages/clans. Adena leaders mayhave helped organize ceremonies, and supervise mound and earthworkconstruction and upkeep. They undoubtedly also were responsible forworking-out social, political, and economic alliances with neighbors andfor trading with outside groups.Adena people followed certain rules when interacting with each o<strong>the</strong>r.It didn’t matter if <strong>the</strong> interaction was with close family members, lineage/clan relations, or more distant relatives in neighboring social groups.Sharing would have been one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most basic rules by which Adenapeoples lived. This rule made sure that everyone had equal access to all<strong>the</strong> necessities <strong>of</strong> life. Families, lineages/clans, or social groups, but notindividuals, controlled food, natural resources, and land.Differences in age and gender also created rules. It is likely that menwere responsible for clearing <strong>the</strong> land for garden plots. They probablywere <strong>the</strong> main hunters and politicians. Women’s responsibilities includedtaking care <strong>of</strong> children, collecting wild plants, and gardening. Older menand women probably served as religious leaders and healers.Personal accomplishments set some people apart. Archaeologistsbase this statement on <strong>the</strong> fact that Adena people buried some men andwomen in mounds. Rare and valuable burial <strong>of</strong>ferings sometimes wereplaced in <strong>the</strong>ir graves.SettlementsBecause Adena people built large ear<strong>the</strong>n mounds and buried some<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir dead in log-lined tombs inside <strong>the</strong>m, it’s easy to think <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m assettled village dwellers. But <strong>the</strong>y were not.12

Adena peoples were mobile hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rer-gardeners. They lived insmall camps commonly located along terraces overlooking permanentstreams, although <strong>the</strong>y built some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir camps on ridgetops, too. Theydid not live at <strong>the</strong>ir camps year-round, nor did <strong>the</strong>y necessarily return to<strong>the</strong> same one every year.Their lives were not ones <strong>of</strong> aimless wandering, though. They planned<strong>the</strong>ir moves carefully to take advantage <strong>of</strong> seasonally available wildplants and animals. The gardens <strong>the</strong>y planted in <strong>the</strong> spring and harvestedin <strong>the</strong> fall may have encouraged <strong>the</strong>m to stay put during certain times <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> year.Extended families moved within <strong>the</strong>ir social group’s home territory.Since <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass would have been home to many social groups, itwould have been a patchwork <strong>of</strong> home territories. As families movedduring <strong>the</strong> year, <strong>the</strong>y would have encountered o<strong>the</strong>rs families: from <strong>the</strong>irown social group and from neighboring ones.Sheets <strong>of</strong> mica, cut into crescents, served anunknown ritual purpose.At a site in Pike County, archaeologists uncovered <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong>an Adena camp. The house was a roughly rectangular structure thatenclosed about 200 square feet. The remains <strong>of</strong> a small hearth wereinside it. To form <strong>the</strong> walls, <strong>the</strong> people had set posts into <strong>the</strong> ground,although archaeologists found no evidence <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong> walls had beenmade <strong>of</strong>. Perhaps <strong>the</strong> people had used hides, mats, or brush.Outside, but near <strong>the</strong> structure, archaeologists found o<strong>the</strong>r hearths, aspearpoint cache (several spearpoints tightly bundled toge<strong>the</strong>r in a pit), afew small pits, and earth ovens. Archaeologists think <strong>the</strong> people carriedout most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir day-to-day activities in this outside area.13

Adena families might have stayed at camps like <strong>the</strong> Pike Countyexample for several months. This may have been particularly true in <strong>the</strong>late summer and early fall, when many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> plants <strong>the</strong>y grew wouldhave been ready to harvest.They would have camped briefly in some places for very specificreasons, like to be near important natural resources. These resourcesmight have included good hunting grounds; groves <strong>of</strong> nut-bearing trees;or places where <strong>the</strong>y could collect or quarry chert (a stone, commonlyknown as flint, used to make stone tools).FoodInformation from Adena campsites provides a glimpse <strong>of</strong> what <strong>the</strong>yate. The main animals were white-tailed deer, black bear, and elk. Smallmammals included squirrel, raccoon, and rabbit. They also ate wildturkey, fished, and ate reptiles and amphibians, like turtles, snakes, andlizards. Adena hunters used <strong>the</strong> atlatl, or spearthrower, to hunt <strong>the</strong> largeranimals. They may have used snares, traps, or nets to capture <strong>the</strong> smallerones.Many different kinds <strong>of</strong> wild fruits, such as blackberry, strawberry,grape, and persimmon, also were part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir diet. Their favorite nutswere hickory nuts and walnuts. Women could have used a variety <strong>of</strong>containers, such as baskets, and skin or net bags, on <strong>the</strong>ir wild plant foodcollecting trips.Adena peoples also grew some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> foods <strong>the</strong>y ate. In comparison to<strong>the</strong>ir ancestors’ diet, plants made up more <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>irs.Just as Kentuckians do today, Adena people prepared <strong>the</strong>ir gardensin <strong>the</strong> spring. Naturally open sunny spots on <strong>the</strong> landscape made goodgarden spots. So did <strong>the</strong> places <strong>the</strong>y cleared <strong>the</strong>mselves.They made <strong>the</strong>ir copper bracelets from Great Lakes copper.

Preparing a garden space took severalsteps. First, <strong>the</strong> men had to remove <strong>the</strong>larger trees. They could have cut <strong>the</strong>mdown with <strong>the</strong>ir stone axes. Or <strong>the</strong>y couldhave girdled <strong>the</strong>m (cut a band <strong>of</strong> bark fromaround <strong>the</strong> trunk) to kill <strong>the</strong> tree. Then <strong>the</strong>ywould have set small, controlled fires to kill<strong>the</strong> smaller trees and saplings and to burn<strong>of</strong>f<strong>the</strong> leaf litter, brush, and weeds. The ashfrom <strong>the</strong>se fires enriched <strong>the</strong> garden soil.Women planted seeds in <strong>the</strong>secleared garden areas using flat woodendigging sticks. They also could have justscattered seeds on <strong>the</strong> ground. They grewdomesticated varieties <strong>of</strong> gourds, squash(like crooknecks and acorn), and certain an Adena celt made <strong>of</strong> graniteweedy plants. The latter produced ediblegreens in <strong>the</strong> spring and small, highly nutritious seeds in late summer/early fall (see Focus On Adena Gardening ).Come harvest time, <strong>the</strong>y stored nuts and seeds for later use. Ceramicvessels may have done a better job controlling moisture and keepingpests out than ones made from gourds, wood, or skin. Adena familiesate <strong>the</strong>se stored plant foods during <strong>the</strong> winter when o<strong>the</strong>r foods were notavailable. They also saved enough seeds to plant <strong>the</strong> following spring.Tools and EquipmentAdena peoples used plants and animals in more ways than justas sources <strong>of</strong> food. They worked <strong>the</strong>m into a host <strong>of</strong> items that <strong>the</strong>irhunting-ga<strong>the</strong>ring-gardening way <strong>of</strong> life required. Wood, stone, and clayalso were necessary raw materials.They used plant fibers and animal sinew to make twine, cord, andyarn. These <strong>the</strong>y hand-wove into net bags, foot gear, and clothing (seeFocus On Adena Fabrics). Animal skins, furs, and bird fea<strong>the</strong>rs alsoserved as raw materials for clothing and bags. Plant dyes added color t<strong>of</strong>abrics, baskets, and nets. Herbal medicines eased a variety <strong>of</strong> aliments,such as toothaches, stomach or headaches, and fever.They used animal bones, skins, and turtle shells, and also gourds andwood, for rattles and drums. Animal bone, animal teeth, and antler, andfreshwater and marine shell and copper, provided <strong>the</strong> raw materials forornaments like beads and pendants.15

Bone and antler served more functional purposes, too. Split deer orturkey bones, sharpened to a point, served as awls used to pierce hides.Stone tool makers used animal bone and deer antler flakers to shape orresharpen spearpoints and scrapers.The atlatl, used to propel spears, was an Adena hunter’s main weapon.It was a two-part tool that required skill to make and use. A hunter made<strong>the</strong> spearshaft from wood or cane, and fitted it with a point <strong>of</strong> bone,antler, or chert. Adena chert spearpoints were broad-bladed and hadstems with straight or oval bases.The atlatl itself consisted <strong>of</strong> a handle and a hook made <strong>of</strong> wood,bone, or antler. To improve performance, hunters <strong>of</strong>ten attached a stonecounterweight to <strong>the</strong> handle. Boatstones made from barite sometimesserved as <strong>the</strong>se weights (see pg. 12). A locally available stone, barite iswhite, chalky, and heavy like lead.These people used locally and non-locally available stone for a variety<strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r tools. Hand-held chert scrapers, or ones socketed into a wooden,bone, or antler handle, were used to cut meat and work hides. Large chertspearpoints also could have served as knives, but small chert blade toolswould have worked just as well.Pitted sandstone rocks, sometimes called nutting stones, were used toprocess nuts. Sandstone pestles and grinding stones were used to prepareplant foods and dyes. They madewood-working tools, such asadzes and grooved axes, fromgranite. Toolmakers pecked ortapped <strong>the</strong>se objects into a roughshape, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y finished <strong>the</strong>m bygrinding and smoothing <strong>the</strong>m.Adena peoples used wood,skin or net bags, gourds, andturtle shells as containers forcooking, food storage or serving,and during rituals. They usedceramic pots for <strong>the</strong>se purposes,too.In making <strong>the</strong>ir vessels, Adenapotters added finely crushedfragments <strong>of</strong> locally availablerock, usually limestone, to <strong>the</strong>This jar is incised with nesteddiamonds.clay. Adding <strong>the</strong>se particles,called temper, improved <strong>the</strong>16

Focus On Adena GardeningAdena peoples were members <strong>of</strong> a gardening traditionthat had been established more than 1000 years before<strong>the</strong>ir culture began. It focused on planting, growing, andharvesting domesticated native plants: weedy annuals thatproduced small, nutrient-rich seeds. Think <strong>of</strong> a handful <strong>of</strong>mixed bird seed, and you’ll have a good idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir size. Under amicroscope, archaeologists can tell <strong>the</strong> difference between <strong>the</strong> seeds<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> domesticated plants and those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir wild cousins: <strong>the</strong>y arebigger; <strong>the</strong> shape may be slightly different; or <strong>the</strong> shells or “seed coats”may be thinner.Like <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors, Adena peoples grew two different kinds <strong>of</strong> nativeplants. Goosefoot, knotweed, and maygrass produced seeds high incarbohydrates or starches. Sumpweed and sunflower produced seedshigh in fat and protein content, and so were high in calories.charred maygrass seedsThese plants grew best where <strong>the</strong> ground was open and disturbed.They were easy to grow and easy to harvest.But preparing <strong>the</strong>m to eat wasn’t so easy. Adena women first had toseparate <strong>the</strong> edible seeds from <strong>the</strong> inedible stalks and stems. Thismeant thrashing <strong>the</strong> plants to break <strong>the</strong>m up, and <strong>the</strong>n winnowing <strong>the</strong>seed from <strong>the</strong> chaff. Then <strong>the</strong>y had to break <strong>the</strong> hard seeds into smallerpieces. They did this by ei<strong>the</strong>r pounding <strong>the</strong> seeds or grinding <strong>the</strong>m.Pounding produced larger fragments like grits. Grinding produced fine,flour-like particles.If preparing <strong>the</strong>se small cereal grains was so time-consuming, why didAdena peoples bo<strong>the</strong>r growing <strong>the</strong>m at all? Any gardener can tell youwhy: good nutritional value; reliable production; disease resistance;and storability. These grains’ calorie content is similar to that <strong>of</strong> corn orrice, but <strong>the</strong>ir protein content is higher. Compared to hickory and oaktrees, <strong>the</strong>se plants are more reliable producers, <strong>the</strong>ir yields comparableto some varieties <strong>of</strong> corn. And although <strong>the</strong> seeds ripen in <strong>the</strong> latesummer/early fall, <strong>the</strong>y store well. Women could put <strong>of</strong>f preparing <strong>the</strong>muntil <strong>the</strong>ir families had almost used up o<strong>the</strong>r foods.17

clay’s workability and increased<strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong> vessel walls.Temper also ensured that <strong>the</strong>unfired vessel would not shrinktoo much before firing, andthat during firing, it would heatevenly and not crack. Adenapotters did not fire <strong>the</strong>ir vesselsin kilns; <strong>the</strong>y used open-airfires. Their finished pots werewatertight and sturdy.Unlike <strong>the</strong>ir ancestor’sclay pots, which were crude,deep, cauldron-like basins,Adena potters made wellsmoo<strong>the</strong>d,thick-walled, <strong>of</strong>tenflat-bottomed jars (see pg. 42).These jars had thickened rimsMaking Adena fabrics, like this exampleshowing red and yellow dyed bands, tooka lot <strong>of</strong> work and time.and no handles <strong>of</strong> any kind. Very rarely, <strong>the</strong>y were decorated on <strong>the</strong>outside with geometric designs. With <strong>the</strong> increased importance <strong>of</strong> gardenplants in <strong>the</strong>ir diet, Adena peoples may have developed new ways toprepare food, ones that differed from those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. This mayhave led <strong>the</strong>m to change <strong>the</strong> shape <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir cooking vessels.Trade and ExchangeBluegrass Adena peoples traded with <strong>the</strong>ir neighbors. Theyundoubtedly exchanged locally available, but unworked, raw materials,like chert, banded slate, and granite. Unfortunately, perishable goodsrarely leave any trace in <strong>the</strong> archaeological record. Thus, we can onlyguess what kinds <strong>of</strong> food, baskets and fabrics, fea<strong>the</strong>rs, paints, andmedicinal or dye plants might have changed hands. During <strong>the</strong> exchange<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se tangible goods, <strong>the</strong>y likely also shared information, stories, andsongs.They probably also would have traded for special ritual items madefrom local materials. These could have been leaf-shaped chert blades, orbarite and hematite cones and boatstones. The latter also are sources <strong>of</strong>pigment. When rubbed lightly, barite produces a white powder. Hematite,when ground, produces a red powder called red ochre.The raw materials for some ritual items and burial <strong>of</strong>ferings werenot available locally or regionally, however. Bluegrass Adena peoples18

Focus On Adena FabricsThere is no question that Adena people made fabrics. Archaeologistshave recovered small pieces from some mounds.Adena fabric-making started with yarn. Weavers probably made most <strong>of</strong>it from fibers found in <strong>the</strong> stems <strong>of</strong> plants, like milkweed and rattlesnakemaster, and in <strong>the</strong> inner bark <strong>of</strong> trees, like cedar and pawpaw.They likely made <strong>the</strong> yarn by twisting <strong>the</strong> processed fibers on <strong>the</strong>irthighs. They could produce very high-quality yarns barely thicker than1/32nd <strong>of</strong> an inch. These are as fine as <strong>the</strong> flax yarns Egyptians used tomake linen. Adena weavers also twisted water birds’ downy fea<strong>the</strong>rs intosome yarns. This would have created a finished fabric that was s<strong>of</strong>t andwarm.Adena fabrics were not strings haphazardly strung toge<strong>the</strong>r. They werestructurally complex. Adena weavers did not use looms. Instead, <strong>the</strong>ymade fabrics in many different ways using only <strong>the</strong>ir hands.Twining and plaiting were <strong>the</strong> most common methods. They producedtwined fabrics by twisting toge<strong>the</strong>r two or more horizontal yarns arounda vertical yarn. A common twined fabric consisted <strong>of</strong> twisted horizontalyarns around alternating pairs <strong>of</strong> vertical yarns. This created a diagonalpattern. In plaiting, <strong>the</strong>y passed horizontal and vertical yarns over andunder each o<strong>the</strong>r in a regular pattern. In a common form <strong>of</strong> plaiting, <strong>the</strong>yarns passed over and under each o<strong>the</strong>r at a 55-degree angle. Using just<strong>the</strong>se two methods, Adena weavers could have made a host <strong>of</strong> items tosuit any need: bags, sashes, mantles (similar to a large shawl), skirts,and blankets.an example <strong>of</strong> an Adena twined textileTo create designs, <strong>the</strong>y wove chevrons and diagonal lines into <strong>the</strong>irfabrics. But <strong>the</strong>y also could have used yarns <strong>of</strong> different colors tocreate <strong>the</strong> same effect. To dye yarn, Adena weavers soaked it in urine,which contained a chemical that would fix <strong>the</strong> color, mixed with parts<strong>of</strong> certain plants. These might include roots, nut hulls, seed skins, fruit,bark, leaves, or stems <strong>of</strong> plants like sumac, bedstraw, or black walnut.The resulting red, pink, yellow-gold, green, tan, brown, and black yarns,when woven toge<strong>the</strong>r, would have produced vibrant fabrics.On certain occasions, all members <strong>of</strong> an Adena lineage/clan or socialgroup might have worn clothing <strong>of</strong> a particular color or with a designpattern that was uniquely <strong>the</strong>ir own. Some people, like shamans orlineage/clan leaders, might have earned <strong>the</strong> right to wear special fabrics,colors, or designs.19

CopperBariteMicaShellsShellsShellsShellsAdena CultureBy identifying <strong>the</strong> sources <strong>of</strong> non-local materials, archaeologistscan document <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> Adena long-distance exchange.needed copper for bracelets, rings, and beads; and marine shells (conch,marginella, and columella) for beads and ornaments. They also neededflat pieces <strong>of</strong> copper <strong>the</strong>y could cut into antler headdresses or wraparound wooden ear ornaments. They needed sections <strong>of</strong> mica <strong>the</strong>y couldshape into crescents and attach to clothing.Bluegrass Adena peoples did not have to travel far, though, to getcopper, marine shells, or mica. That’s because <strong>the</strong>y were involved inlong-distance trade networks that linked <strong>the</strong>m to people and placesthousands <strong>of</strong> miles away. These non-local raw materials, or <strong>the</strong> finisheditems made from <strong>the</strong>m, moved great distances simply by being tradedfrom person-to-person through <strong>the</strong>se exchange networks.What did <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass Adena peoples have to <strong>of</strong>fer in exchange foritems made from copper, marine shells, and mica? Archaeologists thinkperhaps barite: raw, powdered, or fashioned into objects. That’s because<strong>the</strong> Bluegrass region may have been <strong>the</strong> only source <strong>of</strong> it, making ita rare commodity. Adena people could have dug it from undergroundveins and sinkholes or ga<strong>the</strong>red it from along creek banks in <strong>the</strong>ir hometerritories.20

Health and DiseaseAlthough Depression-eraarchaeologists excavated many Adenaburial mounds, we still do not havea detailed picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se peoples’health. One reason is that Adenapeople commonly cremated <strong>the</strong>ir dead.Never<strong>the</strong>less, archaeologists do knowsomething about <strong>the</strong> overall health andappearance <strong>of</strong> Adena people, and about<strong>the</strong> illnesses <strong>the</strong>y experienced.On average, <strong>the</strong> Adena were severalinches shorter than Americans aretoday. They rarely grew to six feet tall.To judge from <strong>the</strong> size <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir bonesand <strong>the</strong> muscle markings on <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>ywere heavily built and strong. The backs<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir heads were <strong>of</strong>ten flattened, somuch so that archaeologists assume <strong>the</strong>ypracticed cradleboarding. This flatteningoccurs when <strong>the</strong> heads <strong>of</strong> infants areroutinely fixed to a rigid surface, like acradle board. Eventually <strong>the</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t bones<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> skull are affected, but this changein skull shape has no o<strong>the</strong>r effect on aperson.Like preindustrial groups worldwide,most Adena people did not live verylong. Forty-five was a ripe old age, andfew lived beyond 65. Infant mortalitywas high, and many children died before<strong>the</strong>y reached <strong>the</strong>ir first birthday. This isgenerally true <strong>of</strong> all human groups.Recent people who live in <strong>the</strong>developed world are different. Twentyfirstcentury Americans can expect to liveto be about 78 years old, and very fewinfants die before <strong>the</strong>y are one-year old.When found, this eleven-inch-long copper knife or dagger from Fayette County waswrapped in two different kinds <strong>of</strong> fabric. It has a wooden hand-grasp.

Most Adena people had cavities in <strong>the</strong>ir teeth, which <strong>the</strong>y nevertreated. Often, this led to abscesses and tooth loss. The chewing surfaces<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir teeth were heavily worn from grit in <strong>the</strong>ir food, unlike our teethtoday. Grooves and pits on <strong>the</strong>ir teeth - places where <strong>the</strong> tooth enamelis poorly formed - show that, as children, Adena people experiencedtimes <strong>of</strong> malnutrition and infection. It is very likely that <strong>the</strong>se conditionsoccurred at <strong>the</strong> same time.Because most broken bones healed, archaeologists infer that injuredpeople were well-taken care <strong>of</strong>. This was also true for people whohad birth defects: a man who lived into adulthood with a congenitallydeformed leg was buried in one Boone County mound.Many diseases leave behind traces on bones, so we know that Adenapeople suffered from arthritis and anemia. The former was undoubtedlyrelated to <strong>the</strong>ir active lives. Anemia would have resulted from a poor dietor excessive, chronic blood loss, perhaps caused by intestinal parasites.O<strong>the</strong>r bone changes show that <strong>the</strong>se people also suffered from infections.Bloodborne infections affected many parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> skeleton all at once.Localized infections affected specific bones, like those that occurredbecause <strong>of</strong> overlying s<strong>of</strong>t tissue infections or from a kick in <strong>the</strong> shin.RITUAL SITESEach time a relative or friend dies, modern Kentuckians must facemany issues: practical, personal, social, economic, and spiritual. Deathsets in motion a host <strong>of</strong> events. The body must be taken care <strong>of</strong>, andceremonies <strong>of</strong> memorial and mourning must be planned. Relatives andfriends <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deceased visit with one ano<strong>the</strong>r and share food at formaland informal ga<strong>the</strong>rings. Death requires us to make decisions. Whatshould we do with her belongings? Who will take over his jobs andresponsibilities? Death gives <strong>the</strong> living an opportunity to think about<strong>the</strong>ir own place in <strong>the</strong> world and to remember o<strong>the</strong>rs who have passedaway.Adena peoples faced <strong>the</strong>se same issues when someone died. The factthat <strong>the</strong>y dealt with <strong>the</strong>se issues makes <strong>the</strong>m similar to us today, but <strong>the</strong>ways in which <strong>the</strong>y dealt with <strong>the</strong>m make <strong>the</strong>m Adena. These peopleleft behind ample evidence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir mortuary rituals that we are onlybeginning to understand. Archaeologists have identified three differentkinds <strong>of</strong> Adena ritual sites: circular paired-post enclosures, burialmounds, and geometric earthworks. No two are <strong>the</strong> same. Each site22

a cone-shaped MontgomeryCounty mound prior to itsexcavation in 1937reflects <strong>the</strong> decisions made by <strong>the</strong> people who created and used it. Eachsite is a record <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> unique series <strong>of</strong> events held <strong>the</strong>re.Adena groups commonly built <strong>the</strong>ir ritual sites on prominent ridgetopsor bluffs. Often, <strong>the</strong>se locales <strong>of</strong>fered commanding views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>surrounding countryside or stream or river valley. For unknown reasons,Adena groups did not live near <strong>the</strong>ir ritual sites. In this, <strong>the</strong>y differedfrom <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors, who held mortuary rituals at <strong>the</strong>ir seasonal camps.Adena people used some locations for many generations. Clusters <strong>of</strong>mounds and earthworks or pairs <strong>of</strong> mounds illustrate this. Small, singlemounds reflect <strong>the</strong> comparatively short-term use <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r spots. Notevery Adena ritual/mortuary area included an example <strong>of</strong> each kind <strong>of</strong>site.Archaeologists think that several neighboring Adena social groupsmay have taken part in <strong>the</strong> ceremonies carried out at <strong>the</strong>se sacred places.Thus, Adena ritual sites may have been situated where <strong>the</strong> boundaries <strong>of</strong>several groups’ home territories came toge<strong>the</strong>r, and not in <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong>one.Circular Paired-Post EnclosuresIn some spots, ritual activities began with topsoil removal and <strong>the</strong>construction <strong>of</strong> an enclosure. It consisted <strong>of</strong> a circle <strong>of</strong> paired posts made<strong>of</strong> locally available wood. Posts could range in diameter from small(three inches) to quite large (one foot). There is no evidence that <strong>the</strong>builders wove smaller saplings between <strong>the</strong> posts to create a solid wall.Thus, an enclosure may have looked more like a standing screen than awalled structure.23

Paired-post enclosures in <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass ranged in diameter from 26to 116 feet. Size probably was linked to <strong>the</strong> maximum number <strong>of</strong> peoplewho routinely used <strong>the</strong> space. Archaeologists estimate that about 45people could have used <strong>the</strong> smallest ones. More than 175 could have fitinto <strong>the</strong> largest.Excavation <strong>of</strong> this Boone Co. mound revealed <strong>the</strong> circular, paired-postenclosure built before it. With a 56-ft. diameter, about 95 people could havemet within it.The enclosures clearly lack any evidence for use as a living space.There are no hearths, no trash pits, and no domestic refuse. Instead, <strong>the</strong>irinteriors contain <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> clusters <strong>of</strong> posts; intensively fired patches<strong>of</strong> soil; and isolated burial <strong>of</strong>ferings. They also contain clay-lined firebasins where human bodies were cremated; oval pits containing crematedremains; scattered patches or piles <strong>of</strong> cremated remains; and in-<strong>the</strong>-fleshburials. Inside one Boone County enclosure, archaeologists documenteda raised clay platform built opposite an east-facing doorway. Benches orseats appear to have been arranged along a section <strong>of</strong> its perimeter.What did Adena people use <strong>the</strong>se enclosures for? Archaeologists think<strong>the</strong>y probably were special, open-air meeting spaces where Adena groupsheld important ceremonies. The enclosure’s posts would have set up aboundary around this ritual space and helped limit access to it by onlythose directly involved in <strong>the</strong> ceremonies.24

Based on <strong>the</strong> materials found inside <strong>the</strong> enclosures, archaeologistsinfer that <strong>the</strong> rituals were complex and varied. They apparently involveddisplaying <strong>the</strong> dead, cremating individuals, processing or manipulating<strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> individuals cremated elsewhere, and burying <strong>the</strong> dead.Some archaeologists have suggested that Adena peoples also could havetracked <strong>the</strong> rising or setting sun through <strong>the</strong> spaces between <strong>the</strong> pairs <strong>of</strong>posts.Archaeologists do not know how long Adena social groups heldceremonies at an enclosure. It could have been for a considerable amount<strong>of</strong> time. At one spot in Montgomery County, for example, groups builtsix different enclosures in a variety <strong>of</strong> sizes.Sometimes, groups decided to bury one or more people within anenclosure. These may have been people who had achieved a certainsocial status. This decision triggered mound construction. Groups <strong>the</strong>nwould have ei<strong>the</strong>r burned down or dismantled <strong>the</strong> enclosure.To build <strong>the</strong> mound, <strong>the</strong> people <strong>of</strong>ten scraped-up nearby soil.Sometimes, this soil contained tool fragments and food remains left byprehistoric people who had lived at <strong>the</strong> spot hundreds, or even thousands,<strong>of</strong> years earlier. Mound diameter was <strong>of</strong>ten similar to that <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>enclosure.Because Adena builders set <strong>the</strong> posts at an outward slanting angle<strong>of</strong> about 67 degrees, <strong>the</strong> enclosures probably were not ro<strong>of</strong>ed.25

During excavation,Depression-eraarchaeologists easilyrecognized <strong>the</strong> outlines<strong>of</strong> individual basketloads.By mounding-up soil over an enclosure, Adena social groups turneda ritual activity space into a cemetery space. This single, significant actchanged <strong>the</strong> kinds <strong>of</strong> future ceremonies and ritual activities <strong>the</strong>y wouldcarry out at <strong>the</strong> site.Burial MoundsRitual activities did not have to begin with <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> apaired-post enclosure. Adena groups could decide to cremate or buryone or more people at a special spot. They laid <strong>the</strong> bodies or crematedremains on <strong>the</strong> ground surface or placed <strong>the</strong>m in simple pits. Then<strong>the</strong>y built mounds over <strong>the</strong>se graves. Just as previously described, <strong>the</strong>yscraped-up soil from around <strong>the</strong> burial area.The first burial mounds built at any ritual site stood only a few feettall and measured 70 feet or less in diameter. If <strong>the</strong>y buried no oneelse within a mound, it remained a small, low, conical feature on <strong>the</strong>landscape. Undoubtedly, thousands <strong>of</strong> small Adena mounds once werescattered across <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass. Most have been lost to historic plowingand farming, and <strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> towns and cities.However, at some mound sites, Adena social groups continued tobury people, covering each with soil. With every addition, <strong>the</strong>se moundsbecame larger and taller. Periodically, <strong>the</strong>y capped <strong>the</strong> whole mound witha layer <strong>of</strong> soil. Over time, <strong>the</strong>se mounds became vertical cemeteries thatgrew through several stages. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest Adena mounds in <strong>the</strong>Bluegrass stood 31 feet tall and measured 180 feet in diameter.Adena <strong>moundbuilders</strong> apparently did not decide beforehand howlarge a mound would become. Instead, a mound’s size and shape appearto reflect <strong>the</strong> activities that took place during its history <strong>of</strong> use. Size also26

does not accurately reflect <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> people buried within a mound.The two largest Bluegrass examples were <strong>of</strong> similar size: one containedone hundred people; <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, only 21 individuals.The fill used for later mound stages was <strong>of</strong>ten different from <strong>the</strong> loosetopsoil used to cover <strong>the</strong> first burials. It was a very tough, pure, denseclay that ranged in color from deep red to light yellow. Like <strong>the</strong> soil <strong>the</strong>yused initially, <strong>the</strong>y found this clay in places not too far from <strong>the</strong> mound.They used simple tools, like digging sticks, to break up <strong>the</strong> clay. Then<strong>the</strong>y filled-up baskets and carried <strong>the</strong>se 30-pound loads to <strong>the</strong> mound.Archaeologists do not know how long Adena people buried <strong>the</strong>ir deadin <strong>the</strong> larger mounds before <strong>the</strong>y capped <strong>the</strong> mounds with clean soiland no longer used <strong>the</strong>m as cemeteries. Perhaps burial stopped when itbecame too difficult to add individuals and still maintain <strong>the</strong> mound’sconical or loaf shape.Mounds may have been <strong>the</strong> most visible Adena ritual sites. Yet, like<strong>the</strong> enclosures, <strong>the</strong>y were not always self-contained. For certain people,a mound could be <strong>the</strong>ir final resting place. For o<strong>the</strong>rs, it could have beenjust a stopover on <strong>the</strong>ir journey to <strong>the</strong> afterlife. Bodies might be crematedor defleshed at a mound, but buried at an enclosure. Alternatively, bodiescould be prepared elsewhere and <strong>the</strong>n brought to a mound for burial.Besides graves, archaeologists have documented fired areas, layersor piles <strong>of</strong> stone or rock, pits, and artifact caches within some mounds.During one Montgomery County mound’s history, groups completelycovered its surface with logs laid out radially around its summit.Some items found within <strong>the</strong> mound fill were not associated with agrave, fired area, rock pile, pit, or cache. Examples include bits <strong>of</strong> animalbone, charred plant remains, chert chips and broken tools, and fragments<strong>of</strong> ceramic containers. These may have been accidentally mixed into <strong>the</strong>fill.Archaeologists think that o<strong>the</strong>r items, however, particularly thoseassociated with later mound stages, may have been purposefullyleft at or on <strong>the</strong> mound. These objects may have been used duringmortuary events, <strong>the</strong>n buried. They also could have been brokenLarger mounds could contain fourto eight stages. This Boone Countymound grew through four.

during ceremonies, and <strong>the</strong>n scattered by shamans across <strong>the</strong> moundas <strong>of</strong>ferings. They might represent <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> food eaten duringgraveside feasting rituals. Vessel fragments could represent sections<strong>of</strong> jars used to bring cremated human remains to <strong>the</strong> mound. Materialscleaned out <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r ritual areas could have found <strong>the</strong>ir way into <strong>the</strong>mound fill.Alternatively, <strong>the</strong>se objects could have been left behind during moundmaintenance activities carried out between interments and constructionphases. During visits to <strong>the</strong> mound, relatives could have left objects tomemorialize <strong>the</strong> dead.Archaeologists think it likely that Adena peoples carried out some <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>ir rituals away from, but within sight <strong>of</strong>, <strong>the</strong>ir mounds. Not far froman Adena mound in Montgomery County, researchers have investigatedjust such an activity area.In <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> this site, <strong>the</strong>y documented two posts, an ash pile,and a rock-filled pit containing a small amount <strong>of</strong> burned bone.Several individuals may have been cremated here. Also near <strong>the</strong> sitecenter, <strong>the</strong>y found small pits containing charred plant food remains.Plants represented were squash, acorn, goosefoot, maygrass, purslane,sunflower, persimmon, and strawberry. Mourners may have used <strong>the</strong>sepits for food storage before feasting, or for trash disposal afterwards.O<strong>the</strong>r pits contained a special clay brought to <strong>the</strong> site and fragments<strong>of</strong> worked barite and mica. Ritual participants may have used <strong>the</strong> clayto make graves or platforms inside <strong>the</strong> mound, or perhaps to build <strong>the</strong>mound itself. The barite and mica fragments suggest that Adena peoplemay have made burial <strong>of</strong>ferings or ritual objects at this site.Geometric EarthworksAdena people commonly built <strong>the</strong>ir earthworks near o<strong>the</strong>r Adenaearthworks and burial mounds. Most are circular, varying in diameterfrom 125 to 300 feet. They consist <strong>of</strong> an interior space, perhaps aramp extending to <strong>the</strong> center, a ditch, and a surrounding embankment.However, archaeologists have documented single examples <strong>of</strong> square andpossibly hexagonal Adena earthworks <strong>of</strong> similar size in <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass.Adena <strong>moundbuilders</strong> moved considerable amounts <strong>of</strong> earth during<strong>the</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se earthworks. They did it all using only diggingsticks to loosen <strong>the</strong> soil; baskets to transport it; and human muscle.First, <strong>the</strong>y traced a nearly perfect circle on <strong>the</strong> ground as a template.Then <strong>the</strong>y dug a C- or O-shaped ditch, and threw <strong>the</strong> soil outward tocreate <strong>the</strong> embankment. The ditch could measure 45 feet wide and28

extend nearly 8 feet below <strong>the</strong>ground surface. The embankmentcould stand more than 4 feet high.Occasionally, Adena groups builta circular paired-post structurewithin a circular earthwork’sinterior space, like <strong>the</strong> one shownon page 24. These structures arevirtually identical to <strong>the</strong> paired-postenclosures discussed previously.After <strong>the</strong>se structures had served<strong>the</strong>ir purpose, Adena groups simplytore <strong>the</strong>m down. They filled <strong>the</strong>holes with clay where <strong>the</strong> posts hadonce stood.These sites have produced veryfew artifacts; for some reason,Adena groups kept <strong>the</strong>se sitespurposefully clean. Archaeologistsalso have not found any pits, clayplatforms, or burials associatedwith <strong>the</strong>m, nor have <strong>the</strong>y found anyevidence <strong>of</strong> fire.The geometric Adena earthworksand <strong>the</strong>ir structures clearly wereritual sites that enclosed sacredor spiritually significant space.However, <strong>the</strong> kinds <strong>of</strong> activitiesAdena groups carried out withinor around <strong>the</strong>m apparently weredifferent from those that took placewithin or around <strong>the</strong>ir o<strong>the</strong>r ritualsites. To date, archaeologists do notclearly understand what role <strong>the</strong>earthworks and <strong>the</strong>ir structures mayhave played in Adena ceremoniallife. Perhaps, as archaeologists havesuggested for some paired-postenclosures, Adena people tracked <strong>the</strong>rising or setting sun from <strong>the</strong>se sites.From local cherts, <strong>the</strong>y chipped-out delicate leaf-shaped blades that <strong>the</strong>y placed incaches. They may have traded <strong>the</strong>se blades for items made outside <strong>the</strong> Bluegrass.

Early on a spring morning, Adenashamans hold a ceremony within acircular earthwork to celebrate <strong>the</strong> gift <strong>of</strong>renewed life. This earthwork sits next toNorth Elkhorn Creek in Fayette County.O<strong>the</strong>r FunctionsJust like places <strong>of</strong> worship today, Adena ritual sites undoubtedlywere much more than just places <strong>of</strong> burial and ceremony. By studyingtraditional hunter-ga<strong>the</strong>rer-gardener groups and moundbuilding peoplesworldwide, archaeologists can get an idea <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> kinds <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r social,economic, and symbolic functions Adena ritual sites may have served.Archaeologists think that neighboring social groups jointly used<strong>the</strong>se sites. Thus, <strong>the</strong>y provided places for groups to interact with notonly <strong>the</strong> dead, but with each o<strong>the</strong>r as well. As at funerals today, Adenapeople probably visited and socialized with each o<strong>the</strong>r at <strong>the</strong>ir ritualsites. Activities undoubtedly included feasting. Some couples mighthave married during <strong>the</strong>se ga<strong>the</strong>rings, establishing new social links orstreng<strong>the</strong>ning old ones.30

Adena groups probablyworked-out more than socialalliances at <strong>the</strong>se events, however.They probably also exchangedgifts, such as spearpoints, food,raw materials, and clothing. Thesegifts were symbols <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir socialrelationships. Gift-giving alsoestablished or cemented economicrelationships between individuals,families, lineages/clans, and <strong>the</strong>larger Adena social groups.In <strong>the</strong>ir rituals, <strong>the</strong>y used hematite celts.Lineage/clan leaders likelywere <strong>the</strong> ones responsible for <strong>the</strong> exchange <strong>of</strong> rare, non-local objects and<strong>the</strong> raw materials from which <strong>the</strong>y were made, like copper, mica, andmarine shell. The use <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se valuable items as burial <strong>of</strong>ferings removed<strong>the</strong>m from Adena trading networks. This kept <strong>the</strong>ir value high andcreated a constant demand for <strong>the</strong>m.Adena ritual sites also may have been symbolic focal points.Worshipers may have thought <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> isolated ridge- or blufftop sites asplaces that physically linked <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> spirit world. They also mayhave seen <strong>the</strong> stages <strong>of</strong> a person’s life reflected in <strong>the</strong> dynamic histories<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> largest mounds’ construction, use, renewal, and end.Adena social groups probably also held o<strong>the</strong>r kinds <strong>of</strong> ceremoniesat <strong>the</strong> mounds and earthworks besides those related to death. They<strong>period</strong>ically covered some larger mounds completely in a layer <strong>of</strong> soil orclean clay. Archaeologists think, <strong>the</strong>refore, that Adena people may haveheld world-renewal ceremonies at <strong>the</strong>se sites.The purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se annually held, communal ceremonies is to put<strong>the</strong> world back into balance, and <strong>the</strong>reby, make sure it continues. Worldrenewalceremonies carried out by groups today can last for weeks.Activities include dancing, singing, giving prayers <strong>of</strong> thanks to all spiritsand <strong>the</strong> Creator, and remembering <strong>the</strong> dead.Eventually, Adena groups no longer actively used a ritual site forceremonies or as a cemetery. They undoubtedly continued to carry outsome rites in or around <strong>the</strong>m for several generations, however. Theseplaces, so steeped in history, probably remained fixed in people’smemories for even longer.31

Adena people made several kinds <strong>of</strong> stone gorgets, a type<strong>of</strong> ornament worn at <strong>the</strong> throat.FORMS OF BURIALAdena burial practices were complex, diverse, and varied. Theywere very different from those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir ancestors. Those earlier peoplesburied <strong>the</strong>ir dead in a flexed (or fetal) position in simple pits dug into <strong>the</strong>ground.Archaeologists do not know how Adena peoples buried individualsnot covered by or placed within a mound. This means we do not knowhow <strong>the</strong>y treated most infants, children, and adults. They may havecremated <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>n scattered <strong>the</strong>ir ashes on <strong>the</strong> ground or on <strong>the</strong> surface<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> water. They could have stood on a ridgetop and let <strong>the</strong> wind take<strong>the</strong> ashes. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, <strong>the</strong>y may have laid <strong>the</strong> bodies on scaffolds,hung <strong>the</strong>m from trees, or buried <strong>the</strong>m in very shallow graves. We simplydo not know, because no one has found <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se people.This cut-away view shows an elaborate Adena log tomb or crypt, completewith temporary shelter. It measures 17 by 15 feet and is 5 feet deep. Thedead man’s relatives had completely covered his body with bark strips. Thispicture shows <strong>the</strong> beginning stage <strong>of</strong> this process, so <strong>the</strong> bark strips coveronly his feet. His body is partially wrapped in a boldly stiped woven blanket.He is wearing tall, knee-high lea<strong>the</strong>r boots and lea<strong>the</strong>r pants. His long hairis tied back with cord. On his left wrist, he wears a copper bracelet. Unseenfrom this viewpoint, but placed near his right shoulder, is a tubular smokingpipe. He may have been a shaman to his people.32

What we do know <strong>of</strong> Adena burial practices comes from <strong>the</strong>ir earthmounds. Archaeologists have documented a host <strong>of</strong> body processing/body disposal combinations, so it is clear that Adena peoples couldchoose from a variety <strong>of</strong> options. It is also clear that guiding lovedones from death to <strong>the</strong> afterlife could have involved many steps andconsiderable <strong>period</strong>s <strong>of</strong> time.Body processing could include exposure to <strong>the</strong> elements (in a placewhere <strong>the</strong> body could decay without being disturbed), cremation, and in<strong>the</strong>-fleshburial. Burial could take place inside a paired-post enclosure orit could take place in <strong>the</strong> open. These burials were <strong>the</strong>n covered with anearth mound. Burial also could occur within or on a mound.Only a fraction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Adena people who ever lived in <strong>the</strong> Bluegrasswere buried below or within mounds. They were adult men and women<strong>of</strong> all ages. Few were younger than twelve. Archaeologists think<strong>the</strong>se people were important members <strong>of</strong> Adena extended families orlineages/clans. They may have held important social positions in <strong>the</strong>ircommunities, like lineage/clan leader, diplomat, healer, or shaman. Theyalso could have been exceptional in some way. Special burial ceremoniesand, in some cases, elaborate burial <strong>of</strong>ferings, recognized and honored<strong>the</strong>se people and <strong>the</strong>ir lineage/clan.

Differences in a person’s social status alone cannot explain <strong>the</strong>many paths to <strong>the</strong> Adena afterlife, however. The social standing <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> person’s relatives and <strong>the</strong> economic resources <strong>the</strong>y could committo <strong>the</strong> ceremonies likely would have played a part. Age, gender, andlineage/clan affiliation undoubtedly influenced how <strong>the</strong>y buried a person.Something as simple as <strong>the</strong> season <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> year also may have been takeninto consideration. Here, we highlight <strong>the</strong> most common forms <strong>of</strong> Adenaburial.CremationCremations did not occur as frequently as in-<strong>the</strong>-flesh burials,although <strong>the</strong>y might represent untold numbers <strong>of</strong> individuals. Cremationtook place away from <strong>the</strong> mounds. It also took place before moundconstruction, in <strong>the</strong> open and inside paired-post enclosures, and at <strong>the</strong>mounds. They built <strong>the</strong>ir crematory fires on prepared clay surfaces, or inshallow pits or clay-lined basins.They cremated some people in <strong>the</strong> flesh. These <strong>the</strong>y wrapped in fabricand laid <strong>the</strong>m out, fully extended, on <strong>the</strong>ir backs. For o<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>the</strong> fleshwas removed from <strong>the</strong> body before cremation. In <strong>the</strong>se cases, <strong>the</strong>y likelyexposed <strong>the</strong> body to <strong>the</strong> elements until only <strong>the</strong> bones remained. Then<strong>the</strong>y ga<strong>the</strong>red up <strong>the</strong> bones and cremated <strong>the</strong>m.Once cremated, <strong>the</strong>y had several burial options. Adena peoplerarely buried cremated remains where <strong>the</strong>y burned <strong>the</strong>m. Usually <strong>the</strong>yprocessed <strong>the</strong> body in one place, <strong>the</strong>n took <strong>the</strong> remains to ano<strong>the</strong>rlocation for burial. Sometimes <strong>the</strong>y scattered <strong>the</strong> remains on <strong>the</strong> floor <strong>of</strong>a paired-post enclosure. In o<strong>the</strong>r cases, <strong>the</strong>y buried <strong>the</strong>m in a pit dug into<strong>the</strong> ground or dug into an enclosure’s floor. The remains could be kepta carved stone platform pipefrom Boone County34

separate, or mixed with <strong>the</strong> remains <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. Beneath some mounds,archaeologists have documented piles and pits containing <strong>the</strong> crematedremains <strong>of</strong> many individuals.They placed <strong>of</strong>ferings with some cremated people. Offerings placedprior to cremation show evidence <strong>of</strong> burning. Offerings were diverse,though not numerous. They included spearpoints, stone gorgets <strong>of</strong>various styles, oval pendants made from slate, hematite cones, and boneawls and combs. Offerings <strong>of</strong> ceramic vessels, red ochre, and marineshell or copper beads were rare.In-<strong>the</strong>-Flesh BurialIn-<strong>the</strong>-flesh burial was <strong>the</strong> preferred form <strong>of</strong> burial associated with <strong>the</strong>mounds. Adena peoples laid <strong>the</strong> body out, fully extended on <strong>the</strong> back,usually with <strong>the</strong> head pointing toward <strong>the</strong> rising sun. They wrapped somepeople in textiles or skins; <strong>the</strong>y sprinkled a few with red ochre.Many were simply laid-out on <strong>the</strong> ground surface or on <strong>the</strong> floor <strong>of</strong> apaired-post enclosure. Some <strong>the</strong>y placed in a simple pit. They lined somepits with clay and/or bark, and after <strong>the</strong> body was placed inside, <strong>the</strong>ysealed <strong>the</strong> pits with <strong>the</strong> same materials.They encased some people’s bodies in a specially prepared, cleaned,easily workable clay <strong>the</strong> consistency <strong>of</strong> Silly Putty. The body wasplaced in a clay-lined pit or basin, or on a layer <strong>of</strong> prepared clay. Then<strong>the</strong>y covered <strong>the</strong> body with a layer <strong>of</strong> clay. This clay became extremelyhard when dry or burned, and <strong>the</strong> sealed grave was almost completelywaterpro<strong>of</strong>. This kind <strong>of</strong> burial usually contained only one person, butoccasionally <strong>the</strong>re were two.In-<strong>the</strong>-flesh burial most commonly took place within log tombs. Thebodies <strong>of</strong> both men and women, individually but sometimes in pairs,were placed on <strong>the</strong> floor in <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tomb. Sometimes <strong>the</strong> bodywas placed on a layer <strong>of</strong> clay covered with bark, and <strong>the</strong>n covered witha layer <strong>of</strong> bark and clay. This kind <strong>of</strong> log tomb burial is shown on page36. In a few cases, small piles <strong>of</strong> cremated human remains accompaniedtomb burials.A variety <strong>of</strong> burial <strong>of</strong>ferings, though few in number, were placed withsome people. Certain objects may have been <strong>the</strong> deceased’s personalitems. These included chipped-stone spearpoints and drills; granite celts;sandstone nutting stones and whetstones; bone flakers; and ornamentslike bone or freshwater shell beads.O<strong>the</strong>r items appear to have been made especially for burial, likedecorated ceramic jars and expanded bar or reel-shaped gorgets madefrom banded shale or granite. Objects made from non-local materials,35

like copper bracelets and marine shell beads, were particularly valuable.Adena groups could get <strong>the</strong>se only through trade.Snake skeletons placed in some graves probably representedritual symbols. Smoking pipes may have been ritual paraphernalia.Undoubtedly, all burial <strong>of</strong>ferings took on important symbolic or ritualmeanings, whe<strong>the</strong>r placed with cremated individuals or those buried in<strong>the</strong>-flesh.A clay- and bark-covered burial wihin a Montgomery County mound.Relatives laid <strong>the</strong> lower bark strips lengthwise on a clay platform.Then <strong>the</strong>y covered <strong>the</strong> body with bark strips, laid crosswise, and alayer <strong>of</strong> clay.36

a necklace <strong>of</strong> disk-shaped shell beadsLog TombsLog tombs deserve special mention here.They were <strong>the</strong> most elaborate Adena burialform and were <strong>the</strong> most common type usedtoward <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> Adena history.Most were rectangular. They built <strong>the</strong>m ina variety <strong>of</strong> sizes: from 7 by 4 feet to 16 by 16feet. They ranged from shallow (a foot) to verydeep (eight feet). Some tombs were completelylined with logs, and o<strong>the</strong>rs were only partiallyso. The following description broadly outlineshow Adena tomb builders might have built alog-lined tomb like <strong>the</strong> one shown on page ??.They began by digging a square orrectangular pit into <strong>the</strong> ground or into a mound.After removing all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> loose soil, <strong>the</strong> builderswere ready to construct <strong>the</strong> tomb. For this, <strong>the</strong>yneeded different sizes <strong>of</strong> logs. They also neededpure, clean, moist, moldable clay. It was similarto <strong>the</strong> kind <strong>the</strong>y used to make clay-sealedgraves.The tomb builders selected locally available trees, such as walnut, ash,elm, and hackberry, for <strong>the</strong> straightness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir trunks. A species’ ritualsignificance undoubtedly was a factor in its selection, too. Using woodhandledstone axes, <strong>the</strong>y cut down trees with a diameter <strong>of</strong> 6-12 inches.Leaving <strong>the</strong> bark intact, <strong>the</strong>y neatly trimmed <strong>of</strong>f all <strong>the</strong> branches usingsmaller, hand-held stone axes or celts. They dug <strong>the</strong> clay locally usingdigging sticks. Because <strong>the</strong>y had no domesticated animals, <strong>the</strong>y hauled<strong>the</strong>se materials to <strong>the</strong> tomb site <strong>the</strong>mselves.Now <strong>the</strong>y could begin tomb construction. The tomb builders lined<strong>the</strong> pit walls with logs <strong>of</strong> matching lengths: longer ones for <strong>the</strong> lengthand shorter ones for <strong>the</strong> width. They put a log at <strong>the</strong> base <strong>of</strong> each wall.Then, <strong>the</strong>y neatly stacked additional logs <strong>of</strong> matching length on top <strong>of</strong> it,leaning <strong>the</strong>m or pushing <strong>the</strong>m against <strong>the</strong> pit walls. Often, <strong>the</strong>y used clayto fill <strong>the</strong> spaces between <strong>the</strong> logs and to hold <strong>the</strong> logs in place.After finishing <strong>the</strong> walls, <strong>the</strong>y moved on to prepare <strong>the</strong> tomb floor andburial platform. The body would lie on <strong>the</strong> platform.They had many options. They might lay down a several-inch-thicklayer <strong>of</strong> pure clay to form a rectangular platform that nearly covered <strong>the</strong>pit bottom. Or <strong>the</strong>y could arrange several logs on <strong>the</strong> floor to form <strong>the</strong>37