Genomic imprinting in the mealybugs - CDFD

Genomic imprinting in the mealybugs - CDFD

Genomic imprinting in the mealybugs - CDFD

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

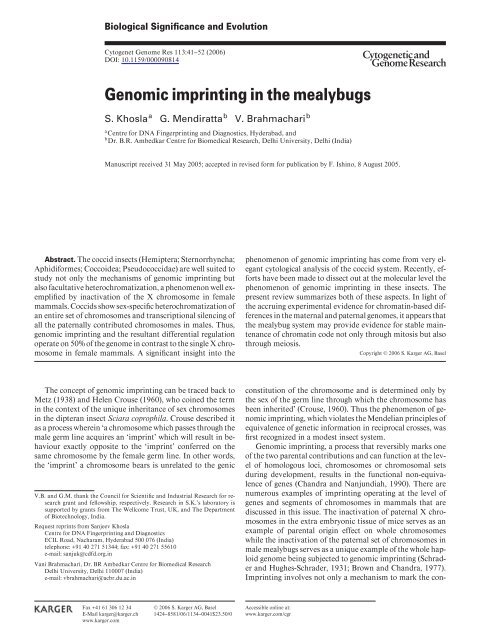

Biological Significance and EvolutionCytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)DOI: 10.1159/000090814<strong>Genomic</strong> <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>a b bS. Khosla G. Mendiratta V. BrahmachariaCentre for DNA F<strong>in</strong>gerpr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g and Diagnostics, Hyderabad, andbDr. B.R. Ambedkar Centre for Biomedical Research, Delhi University, Delhi (India)Manuscript received 31 May 2005; accepted <strong>in</strong> revised form for publication by F. Ish<strong>in</strong>o, 8 August 2005.Abstract. The coccid <strong>in</strong>sects (Hemiptera; Sternorrhyncha;Aphidiformes; Coccoidea; Pseudococcidae) are well suited tostudy not only <strong>the</strong> mechanisms of genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> butalso facultative heterochromatization, a phenomenon well exemplifiedby <strong>in</strong>activation of <strong>the</strong> X chromosome <strong>in</strong> femalemammals. Coccids show sex-specific heterochromatization ofan entire set of chromosomes and transcriptional silenc<strong>in</strong>g ofall <strong>the</strong> paternally contributed chromosomes <strong>in</strong> males. Thus,genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and <strong>the</strong> resultant differential regulationoperate on 50% of <strong>the</strong> genome <strong>in</strong> contrast to <strong>the</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle X chromosome<strong>in</strong> female mammals. A significant <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>phenomenon of genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> has come from very elegantcytological analysis of <strong>the</strong> coccid system. Recently, effortshave been made to dissect out at <strong>the</strong> molecular level <strong>the</strong>phenomenon of genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>sects. Thepresent review summarizes both of <strong>the</strong>se aspects. In light of<strong>the</strong> accru<strong>in</strong>g experimental evidence for chromat<strong>in</strong>-based differences<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> maternal and paternal genomes, it appears that<strong>the</strong> mealybug system may provide evidence for stable ma<strong>in</strong>tenanceof chromat<strong>in</strong> code not only through mitosis but alsothrough meiosis.Copyright © 2006 S. Karger AG, BaselThe concept of genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> can be traced back toMetz (1938) and Helen Crouse (1960), who co<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> term<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context of <strong>the</strong> unique <strong>in</strong>heritance of sex chromosomes<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> dipteran <strong>in</strong>sect Sciara coprophila . Crouse described itas a process where<strong>in</strong> ‘a chromosome which passes through <strong>the</strong>male germ l<strong>in</strong>e acquires an ‘impr<strong>in</strong>t’ which will result <strong>in</strong> behaviourexactly opposite to <strong>the</strong> ‘impr<strong>in</strong>t’ conferred on <strong>the</strong>same chromosome by <strong>the</strong> female germ l<strong>in</strong>e. In o<strong>the</strong>r words,<strong>the</strong> ‘impr<strong>in</strong>t’ a chromosome bears is unrelated to <strong>the</strong> genicV.B. and G.M. thank <strong>the</strong> Council for Scientific and Industrial Research for researchgrant and fellowship, respectively. Research <strong>in</strong> S.K.’s laboratory issupported by grants from The Wellcome Trust, UK, and The Departmentof Biotechnology, India.Request repr<strong>in</strong>ts from Sanjeev KhoslaCentre for DNA F<strong>in</strong>gerpr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g and DiagnosticsECIL Road, Nacharam, Hyderabad 500 076 (India)telephone: +91 40 271 51344; fax: +91 40 271 55610e-mail: sanjuk@cdfd.org.<strong>in</strong>Vani Brahmachari, Dr. BR Ambedkar Centre for Biomedical ResearchDelhi University, Delhi 110007 (India)e-mail: vbrahmachari@acbr.du.ac.<strong>in</strong>constitution of <strong>the</strong> chromosome and is determ<strong>in</strong>ed only by<strong>the</strong> sex of <strong>the</strong> germ l<strong>in</strong>e through which <strong>the</strong> chromosome hasbeen <strong>in</strong>herited’ (Crouse, 1960). Thus <strong>the</strong> phenomenon of genomic<strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, which violates <strong>the</strong> Mendelian pr<strong>in</strong>ciples ofequivalence of genetic <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> reciprocal crosses, wasfirst recognized <strong>in</strong> a modest <strong>in</strong>sect system.<strong>Genomic</strong> <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, a process that reversibly marks oneof <strong>the</strong> two parental contributions and can function at <strong>the</strong> levelof homologous loci, chromosomes or chromosomal setsdur<strong>in</strong>g development, results <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> functional non-equivalenceof genes (Chandra and Nanjundiah, 1990). There arenumerous examples of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>the</strong> level ofgenes and segments of chromosomes <strong>in</strong> mammals that arediscussed <strong>in</strong> this issue. The <strong>in</strong>activation of paternal X chromosomes<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> extra embryonic tissue of mice serves as anexample of parental orig<strong>in</strong> effect on whole chromosomeswhile <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>activation of <strong>the</strong> paternal set of chromosomes <strong>in</strong>male <strong>mealybugs</strong> serves as a unique example of <strong>the</strong> whole haploidgenome be<strong>in</strong>g subjected to genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> (Schraderand Hughes-Schrader, 1931; Brown and Chandra, 1977).Impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>volves not only a mechanism to mark <strong>the</strong> con-Fax +41 61 306 12 34E-Mail karger@karger.chwww.karger.com© 2006 S. Karger AG, Basel1424–8581/06/1134–0041$23.50/0Accessible onl<strong>in</strong>e at:www.karger.com/cgr

Fig. 1. Life cycle of a mealybug. The photographson <strong>the</strong> top show <strong>in</strong>terphase nucleifrom female (left panel) and male (right panel).The heterochromatic set of chromosomes formale nuclei is <strong>in</strong>dicated by white arrows. Thebottom right panel shows sperm bundles (redarrows <strong>in</strong>dicate degenerat<strong>in</strong>g heterochromaticset of chromosomes; photograph taken fromNelson-Rees, 1963).Fig. 2. A diagrammatic representation of<strong>the</strong> various patterns of sex-specific behaviourof chromosomes <strong>in</strong> coccids. The fate of paternaland maternal genomes <strong>in</strong> males is <strong>in</strong>dicated.Blue l<strong>in</strong>es represent paternal and p<strong>in</strong>k l<strong>in</strong>esmaternal chromosomes; th<strong>in</strong> and thick l<strong>in</strong>esfor euchromat<strong>in</strong> and heterochromat<strong>in</strong> respectively.Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006) 43

Heterochromatic chromosomes of <strong>mealybugs</strong>The diploid number of chromosomes <strong>in</strong> most <strong>mealybugs</strong>is ten. Mealybugs follow <strong>the</strong> lecanoid system of chromosomebehaviour, which is characterized by <strong>the</strong> heterochromatizationof an entire set of chromosomes <strong>in</strong> males. Presented belowis <strong>the</strong> fate of <strong>the</strong>se chromosomes dur<strong>in</strong>g different developmentalstages <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> ( Fig. 1 ). The observations presentedhere are almost entirely based on cytological analysis.Heterochromat<strong>in</strong> and euchromat<strong>in</strong> are dist<strong>in</strong>guished by <strong>the</strong>ircytological appearance ra<strong>the</strong>r than any o<strong>the</strong>r biochemical ormolecular parameters.It was observed that all <strong>the</strong> chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybugembryo appear to be euchromatic from <strong>the</strong> zygotic stagethrough <strong>the</strong> cleavage divisions immediately follow<strong>in</strong>g fertilization.However, dur<strong>in</strong>g late cleavage or early blastula, half<strong>the</strong> number of chromosomes becomes heterochromatized <strong>in</strong>some of <strong>the</strong> embryos. These embryos develop <strong>in</strong>to maleswhile <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> embryos develop <strong>in</strong>to females. Thus, maleand female <strong>mealybugs</strong> are dist<strong>in</strong>guished cytologically by <strong>the</strong>heterochromatized set of chromosomes. Exhaustive studyof <strong>the</strong> chromosomal system <strong>in</strong> various species of mealybugand o<strong>the</strong>r related coccids is documented by Schrader (1921,1929), Schrader and Hughes-Schrader (1931), Hughes-Schrader (1948), and is reviewed <strong>in</strong> Brown and Nur (1964)and Brown and Chandra (1977). Heterochromatization thatoccurs around <strong>the</strong> blastula stage is ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>g subsequentdevelopment, except for cells <strong>in</strong> a few tissues whichshow reversal of heterochromatization (Nur, 1967).Gametogenesis <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>Mealybugs like o<strong>the</strong>r Hemipterans exhibit ‘<strong>in</strong>verse meiosis’.In this unorthodox meiosis, <strong>the</strong> first division is equationalwith chromatids and not chromosomes separat<strong>in</strong>g fromeach o<strong>the</strong>r and mov<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> opposite poles at anaphase I.Two chromatids from each bivalent pair at telophase I forma dyad. The second meiotic division is reductional, <strong>the</strong> dyadchromatids separate and move to opposite poles at anaphaseII, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> formation of haploid nuclei ( Fig. 1 , Hughes-Schrader, 1944, 1948).Spermatogenesis <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong> is unusual. At prophase<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> primary spermatocytes, <strong>the</strong> heterochromaticmass separates <strong>in</strong>to <strong>in</strong>dividual chromosomes, which rema<strong>in</strong>condensed, followed by <strong>the</strong> condensation of <strong>the</strong> euchromaticchromosomes, which is completed by metaphase I. Through<strong>the</strong> entire process, <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic and euchromaticchromosomes seem to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> dist<strong>in</strong>ct groups, <strong>the</strong> heterochromaticset form<strong>in</strong>g a tighter group than <strong>the</strong> euchromaticset. Thus, at <strong>the</strong> end of meiosis <strong>the</strong>re are four haploid nuclei,two of which exclusively conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> euchromatic and <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r two heterochromatic chromosomes. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> wholeprocess nei<strong>the</strong>r pair<strong>in</strong>g nor recomb<strong>in</strong>ation occurs ( Fig. 1 ,Brown and Nur, 1964). The meiotic division is not followedby cytoplasmic division and <strong>the</strong> nuclei rema<strong>in</strong> embedded <strong>in</strong>cysts and formation of a quadr<strong>in</strong>ucleate spermatid is observed(Hughes-Schrader, 1935; Nelson-Rees, 1963).However, <strong>the</strong> most important observation that was maderegard<strong>in</strong>g spermatogenesis was that <strong>the</strong> condensed chromosomeset slowly dis<strong>in</strong>tegrates <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> quadr<strong>in</strong>ucleate spermatidand does not form <strong>the</strong> sperm. Thus, only <strong>the</strong> euchromaticnuclei <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se cysts form <strong>the</strong> genetic cont<strong>in</strong>uum through <strong>the</strong>males (Hughes-Schrader, 1935, 1948; Nelson-Rees, 1963;Brown and Nur, 1964 [review]). Inverse meiosis is also observed<strong>in</strong> female <strong>mealybugs</strong> (Brown and Chandra, 1977).Correlation of heterochromatization with sexdeterm<strong>in</strong>ation and genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>In order to expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> unusual chromosomal behaviour<strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>, Schrader and Hughes-Schrader proposed that:(a) <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic set <strong>in</strong> males is genetically <strong>in</strong>ert andthus male <strong>mealybugs</strong> are physiologically haploid (Schraderand Hughes-Schrader, 1931) and (b) <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic setof chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> males is of paternal orig<strong>in</strong> (Hughes-Schrader, 1948).Brown and co-workers later confirmed <strong>the</strong>se hypo<strong>the</strong>ses.They made use of <strong>the</strong> fact that coccid chromosomes are holok<strong>in</strong>etici.e. <strong>the</strong>y have diffuse centromeres and are attachedto <strong>the</strong> mitotic sp<strong>in</strong>dle along <strong>the</strong>ir entire length. Fragmentedchromosomes of <strong>mealybugs</strong> do not lag beh<strong>in</strong>d at metaphaseand are mitotically stable (Hughes-Schrader and Ris, 1941).Brown and co-workers irradiated male and female <strong>mealybugs</strong>and mated <strong>the</strong>m with unirradiated counterparts. The progenyobta<strong>in</strong>ed was <strong>the</strong>n analysed cytologically.It was found that when mo<strong>the</strong>rs were irradiated, <strong>the</strong> euchromaticset of chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> male progeny was affected.It was <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> maleembryos that showed aberrations when fa<strong>the</strong>rs were irradiated(Brown and Nelson-Rees, 1961). This clearly <strong>in</strong>dicatesthat it is <strong>the</strong> paternally derived chromosomes that get heterochromatized<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> male progeny, as Schrader and Hughes-Schrader (1931) had hypo<strong>the</strong>sized. A corollary of this experimentwas <strong>the</strong> observation that even <strong>the</strong> smallest of <strong>the</strong> chromosomalfragments when derived from an irradiated fa<strong>the</strong>rwas heterochromatized <strong>in</strong> his male progeny. In <strong>the</strong> light of<strong>the</strong>se results it was observed that <strong>the</strong> ability to become heterochromaticis probably dispersed along <strong>the</strong> entire length of<strong>the</strong> chromosomes similar to <strong>the</strong> centromeric property (Brownand Chandra, 1977; Khosla et al., 1999). This is <strong>in</strong> contrastto what is known of a s<strong>in</strong>gle <strong>in</strong>activation centre on <strong>the</strong> mammalianX-chromosome (Cattanach, 1975; Lyon, 1995; Avnerand Heard, 2001; Brockdorff, 2002). This <strong>in</strong>ference, alongwith <strong>the</strong> previous observation that <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic set ofchromosomes degenerates after spermiogenesis, would meanthat <strong>the</strong> maternally derived euchromatic chromosomes of <strong>the</strong>fa<strong>the</strong>r become heterochromatic <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sons (Brown and Nur,1964). Thus imply<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> signals for heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> cleavage stages which is present on <strong>the</strong> paternally contributedgenome and absent on <strong>the</strong> maternally <strong>in</strong>herited genomeof <strong>the</strong> males, are acquired by <strong>the</strong> maternally derivedeuchromatic chromosomes dur<strong>in</strong>g spermatogenesis (Khoslaet al., 1996).44Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)

The heterochromatic set of chromosomes <strong>in</strong> males hasbeen demonstrated to be <strong>in</strong>ert by irradiation experiments. Irradiationof males at high doses of X-ray was lethal only to<strong>the</strong>ir female progeny but not <strong>the</strong> male progeny (Brown andNelson-Rees, 1961). The transcriptional silenc<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> heterochromaticchromosomes was shown by monitor<strong>in</strong>g RNAsyn<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>in</strong> situ (Berlowitz, 1965). The <strong>in</strong>ertness of <strong>the</strong> paternalchromosomes <strong>in</strong> males was also evident by <strong>the</strong> patternsof <strong>in</strong>heritance of genetic markers known <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>, likesalmon-eye, an eye colour mutation, and w<strong>in</strong>g morphology(Brown and Wiegmann, 1969).Male and female <strong>mealybugs</strong> are strik<strong>in</strong>gly different morphologicallythough as zygotes <strong>the</strong>y are similar. Even dur<strong>in</strong>gembryogenesis <strong>the</strong> only cytological difference is <strong>the</strong> heterochromatizationof a set of chromosomes, which is apparent only by<strong>the</strong> blastula stage of development. Thus, heterochromatizationseems to be <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t of divergence between <strong>the</strong> male andfemale developmental pathways. Whe<strong>the</strong>r it is a cause or aneffect of <strong>the</strong> sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation is not clear but it does seem toaffect <strong>the</strong> developmental pathways of <strong>the</strong> two sexes.Is facultative heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>dispensable?The heterochromatic chromosomes are genetically <strong>in</strong>activeand <strong>the</strong>refore what is <strong>the</strong> need of reta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g such a haploidset, or <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r words why did <strong>mealybugs</strong> not adopt true malehaploidy <strong>in</strong>stead of functional haploidy as a means of sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation?The answer is not straightforward and <strong>the</strong> reportssuggest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need for persistence of heterochromaticchromosomes are very few and not conclusive.Nelson-Rees (1962) dur<strong>in</strong>g irradiation studies found thatafter severe irradiation of fa<strong>the</strong>rs (60,000–90,000 rep), onlya few sons survived. In all <strong>the</strong>se survivors, no matter howbadly damaged or rearranged <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic set was,<strong>the</strong> amount of <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic material was estimated tobe similar to <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>in</strong> untreated controls. In this experimentNelson-Rees also observed sterility <strong>in</strong> a large proportionof sons of irradiated fa<strong>the</strong>rs and this fraction <strong>in</strong>creasedwith dose of irradiation (Nelson-Rees, 1962; Brown and Nur,1964).Nur and Chandra (1963) showed that a heterochromatic setfrom one species of <strong>mealybugs</strong> can not be substituted for thatof ano<strong>the</strong>r. The rationale was that heterochromatic chromosomesbe<strong>in</strong>g genetically <strong>in</strong>active, <strong>in</strong> some of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terspecificcrosses at least <strong>the</strong> male offspr<strong>in</strong>gs would survive, if not <strong>the</strong>females. However, <strong>the</strong>y found that no offspr<strong>in</strong>g of ei<strong>the</strong>r sexsurvived beyond <strong>the</strong> first <strong>in</strong>star stage <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terspecific crosses.These observations suggest<strong>in</strong>g a need to reta<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> heterochromaticset were challenged by <strong>the</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of Nur (1967).He reported reversal of heterochromatization <strong>in</strong> some tissuesof male <strong>mealybugs</strong>. In Planococcus citri as well as o<strong>the</strong>r species<strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g tissues did not show <strong>the</strong> presence of heterochromaticset (Nur, 1967): <strong>the</strong> yolk cells <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> embryo; <strong>the</strong>mycetocytes; some of <strong>the</strong> oenocytes; some skeletal musclecells; cyst wall cells of <strong>the</strong> testes; cells of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tractand cells of <strong>the</strong> malpighian tubules.Nur (1967) <strong>the</strong>n repeated <strong>the</strong> irradiation experiments ofNelson-Rees (1962) and <strong>in</strong>terspecies crosses of Nur andChandra (1963). He observed <strong>the</strong> reversal of heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> cells of malpighian tubules and gross modificationof <strong>the</strong> tissue <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sons of irradiated fa<strong>the</strong>rs. He po<strong>in</strong>tedout that male sterility was due to <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> tissueswhere reversal occurred did not develop properly, caus<strong>in</strong>gsterility or lethality and not because of bulk requirement of<strong>the</strong> heterochromatic set of chromosomes as was earlier postulated.Similarly, <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terspecific cross ( Pseudococcusobscurus females crossed with Pseudococcus gahanimales); female hybrid embryos did not survive beyond <strong>the</strong>blastoderm, whereas some male hybrid embryos survivedonly till <strong>the</strong> first <strong>in</strong>star stage. In <strong>the</strong>se males <strong>the</strong> tissues whichnormally show reversal of heterochromatization showed <strong>in</strong>completereversal. Most of <strong>the</strong> hybrid males lacked any structurewhich could be considered as malpighian tubules andwherever dist<strong>in</strong>guishable <strong>the</strong>y were poorly developed. However,<strong>the</strong>se analyses by Nur lacked <strong>the</strong> comprehensive studyof o<strong>the</strong>r tissues where reversal of heterochromatization doesnot occur and <strong>the</strong> results failed to provide a satisfactory explanationfor <strong>the</strong> need to reta<strong>in</strong> highly fragmented but equivalentamounts of heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> males irradiated at veryhigh doses.In a later study on males that were irradiated dur<strong>in</strong>g earlystages of <strong>the</strong>ir development, Nur (1970) found some spermatogoniawhere both sets of chromosomes were euchromatic.In <strong>the</strong>se spermatogonia, <strong>the</strong> second meiotic division wasdisrupted and diploid spermatids were formed. This wouldsuggest that heterochromatization of a haploid set is necessaryfor normal meiosis <strong>in</strong> males. It is possible that <strong>the</strong> genes <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> pair<strong>in</strong>g and recomb<strong>in</strong>ation are silent <strong>in</strong> males butbecome active when both chromosome sets are active <strong>in</strong>males. Defective resolution of synaptonemal complexes mayalso disrupt meiosis and lead to sterility as <strong>in</strong> human males.Even earlier observations by Hughes-Schrader (1935) andNelson-Rees (1963) po<strong>in</strong>ted to <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> movement ofheterochromatic chromosomes to <strong>the</strong> poles dur<strong>in</strong>g anaphaseII precedes <strong>the</strong> movement of <strong>the</strong> euchromatic set to <strong>the</strong> oppositepole. As apparent from <strong>the</strong> above discussion, <strong>the</strong> roleof heterochromatic chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> is debatableand <strong>in</strong>conclusive and needs to be substantiated.Models for <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>The phenomenon of parent-specific mark<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> epigeneticmodification of genes/chromosomes demands that anymechanism of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> should <strong>in</strong>clude reversibility, modulationof expression <strong>in</strong> cis without alter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> primary sequenceof DNA and clonal <strong>in</strong>heritablility.Nur described par<strong>the</strong>nogenesis <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> of <strong>the</strong> speciesPulvanaria hydrangea . In this species, <strong>the</strong> haploid egg pronucleusfirst divides and its products fuse to form a diploidzygote substitute. The progeny produced are females and noadult males are observed. However, he found some embryos<strong>in</strong> a particular population of this species which showed heterochromatizationof a set of chromosomes but <strong>the</strong>se did notCytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006) 45

Fig. 3. Hypomethylation of paternal genome.Biot<strong>in</strong>ylated dUTP <strong>in</strong>corporated bynick translation is detected by FITC-labeledanti-biot<strong>in</strong> antibodies. The metaphase platesare treated with Hpa II restriction endonucleasebefore nick translation. Nuclei from males( a–c ) show <strong>in</strong>tense sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with FITC on heterochromaticchromosomes. (d–e) Nucleifrom females show non-uniform sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g withFITC. F+ <strong>in</strong>dicates <strong>the</strong> chromosomes that arelabeled by FITC <strong>in</strong> nuclei from females shown<strong>in</strong> frame e . Reproduced with authors’ permission.(Please see Bongiorni et al., 1999.)develop to term. Such embryos were produced only by a smallnumber of females. S<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r species of Pulvanaria witha sexual mode of reproduction, heterochromatization isl<strong>in</strong>ked to male development, Nur (1963) proposed that <strong>the</strong>seembryos would have subsequently developed <strong>in</strong>to males. In1972 Nur studied three more par<strong>the</strong>nogenetic species of coccidsand found that <strong>the</strong>y produce ei<strong>the</strong>r only male or femaleprogeny par<strong>the</strong>nogenetically, depend<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> species. InLecanium putamani, a species of <strong>mealybugs</strong> <strong>in</strong> which malesare produced par<strong>the</strong>nogenetically, female progeny developfrom fertilized eggs. In all <strong>the</strong>se species males had one set ofchromosomes heterochromatized.To expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> heterochromatization of a set of chromosomes<strong>in</strong> par<strong>the</strong>nogenetically produced males, Nur proposedthat <strong>the</strong> daughter pronucleus <strong>in</strong> Pulvanaria hydrangea ando<strong>the</strong>r par<strong>the</strong>nogenetic species of <strong>mealybugs</strong>, after division,are separated <strong>in</strong> space and this spatial distribution causes oneto become different from <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. He compared this with<strong>the</strong> separation of polar body I and II from <strong>the</strong> egg which makes<strong>the</strong>m different from <strong>the</strong> egg nucleus even though <strong>the</strong> genomiccomplements <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>m are identical (Nur, 1963, 1990).Based on <strong>the</strong> observations of Nur, two models were proposedto expla<strong>in</strong> differential behaviour of homologous chromosomes(Chandra and Brown, 1975; Sager and Kitch<strong>in</strong>,1975). Both <strong>the</strong> models suggest <strong>the</strong> place of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> to be<strong>the</strong> egg, where <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> occurs just after fertilization. Sagerand Kitch<strong>in</strong> addressed <strong>the</strong> molecular nature of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>and suggested that <strong>the</strong> oocyte genome is modified before fertilizationand <strong>the</strong> divergence of male and female developmentis decided by <strong>the</strong> state of modification of <strong>the</strong> sperm genomeafter fertilization. This is based on <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of <strong>the</strong> restriction-modificationsystem known <strong>in</strong> prokaryotes. However,Chandra and Brown (1975) suggested variability <strong>in</strong> extent of<strong>the</strong> <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> region with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> egg and also total absence ofsuch a region <strong>in</strong> some eggs. They proposed that <strong>the</strong> egg andpolar body nuclei escape <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.It is important to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between primary impr<strong>in</strong>t and<strong>the</strong> manifestation of <strong>the</strong> impr<strong>in</strong>t as separate events broughtabout at different stages <strong>in</strong> development. However, this dist<strong>in</strong>ctionis not apparent <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> above mentioned models. TheSager and Kitch<strong>in</strong> model (1975) failed to make impact s<strong>in</strong>cenei<strong>the</strong>r have restriction enzymes been reported <strong>in</strong> higher eukaryotesnor does <strong>the</strong> model expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> reversal of heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> some tissues of <strong>mealybugs</strong> <strong>in</strong> a satisfactorymanner.DNA methylation as a molecular correlate of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>Deobagkar et al. (1982) exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> methylation statusof <strong>the</strong> mealybug genome. Significant amounts of 5-methylcytos<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug genome not only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> d<strong>in</strong>ucleotide(CpG) but also <strong>in</strong> (CpA), (CpC) and (CpT) were found. Also46Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)

eported were high amounts of 6-methyladenos<strong>in</strong>e and 7-methylguanos<strong>in</strong>e which are rarely found <strong>in</strong> DNA of highereukaryotes. This was later confirmed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same species byAchwal et al. (1983) us<strong>in</strong>g a highly sensitive immunochemicalapproach. Devajyothi and Brahmachari (1992) reported aCpA methylase from <strong>the</strong> mealybug Planococcus lilac<strong>in</strong>uswhich could methylate both (CpG) and (CpA) d<strong>in</strong>ucleotides.They also reported modulation of DNA methyltransferaseactivity dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> life cycle of P. lilac<strong>in</strong>us, <strong>the</strong> enzyme activitybe<strong>in</strong>g higher <strong>in</strong> third <strong>in</strong>star females when gametogenesis,fertilization and subsequent development are <strong>in</strong>itiated(Devajyoti and Brahmachari, 1989). Based on sequenc<strong>in</strong>g ofrandom stretches of DNA from <strong>the</strong> mealybug, P. lilac<strong>in</strong>us ,Mohan et al. (2002), <strong>in</strong>ferred that repetitive DNA content <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> mealybug genome is higher than that of Drosophila whileGC content is less. This might <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>the</strong> CpG d<strong>in</strong>ucleotidefrequency <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug genome.Scarbrough et al. (1984) did not f<strong>in</strong>d any modified baseso<strong>the</strong>r than 5-methylcytos<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> two o<strong>the</strong>r species of <strong>mealybugs</strong>,namely Pseudococcus obscurus and Pseudococcus calceolariae, though <strong>the</strong>y found somewhat higher levels of 5-methylcytos<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> males. This difference, however, was foundnot to be very significant. Later Bongiorni et al. (1999) reportedhypomethylation of <strong>the</strong> paternal genome <strong>in</strong> both malesand females us<strong>in</strong>g a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of restriction endonucleasetreatment followed by nick translation with fluorescence labelledprecursors. The <strong>in</strong>corporation of biot<strong>in</strong>ylated dUTPdur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> situ nick translation varied based on susceptibilityof <strong>the</strong> chromat<strong>in</strong> to methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes,Msp I and Hpa II. These results showed that <strong>the</strong> paternalgenome is hypomethylated as compared to <strong>the</strong> maternalset <strong>in</strong> both males and females ( Fig. 3 , Bongiorni et al., 1999).However, <strong>in</strong> this approach only methylation at CCGG sequencesis assessed.Chromat<strong>in</strong> organization as a correlate of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>mealybugs</strong>While dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> primary signal of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>from <strong>the</strong> manifestation of <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, Khosla et al. (1996)exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>the</strong> chromat<strong>in</strong> organization of <strong>mealybugs</strong>, P. lilac<strong>in</strong>us. They observed that approximately 10% of <strong>the</strong> genome <strong>in</strong>male <strong>mealybugs</strong> was organized <strong>in</strong>to a nuclease-resistant chromat<strong>in</strong>(NRC) only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> males and not <strong>in</strong> females, thus correlat<strong>in</strong>git with heterochromatization of <strong>the</strong> paternal genome<strong>in</strong> males ( Fig. 4 , Khosla et al., 1996). They demonstrated additionalattributes of heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>form of nuclease resistance and matrix association (Khosla etal., 1996, and unpublished data). These parameters can serveas novel and easily assayable readouts for heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>.Argu<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> nuclease resistant property if attributedto all <strong>the</strong> heterochromat<strong>in</strong> present <strong>in</strong> males, NRC should havebeen nearly 50% and not 10% of <strong>the</strong> genome as observed; <strong>the</strong>yhypo<strong>the</strong>sized that this fraction conta<strong>in</strong>s sequences that are at<strong>the</strong> core of <strong>the</strong> heterochromat<strong>in</strong> perhaps conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> putativecentres of <strong>in</strong>activation as a subset of sequences with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Fig. 4. Differential sensitivity of male and female nuclei to micrococcalnuclease. Nuclease Resistant Chromat<strong>in</strong> (NRC) is present exclusively<strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>. Nuclei from male and female <strong>mealybugs</strong> were<strong>in</strong>cubated for <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g time (represented by triangles above <strong>the</strong> panels)with MNase. (Please see Khosla et al., 1996 for details.)NRC (Khosla et al., 1996). The multiple centres of <strong>in</strong>activationthat were <strong>in</strong>dicated by <strong>the</strong> irradiation experiments fur<strong>the</strong>rimply that any sequence that can serve as a centre of<strong>in</strong>activation <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> should be present <strong>in</strong> multiple copies,dispersed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> genome. Khosla et al. identified onesuch middle repetitive DNA sequence (nrc51) which was partof <strong>the</strong> unusually organized genome <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> male ( Fig. 5 , Khoslaet al ., 1999). In conjunction with <strong>the</strong> hypomethylation ofpaternal genome <strong>in</strong> males observed by Bongiorni et al. (1999),this specialized packag<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> chromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>occurs on <strong>the</strong> paternal heterochromatized chromosomes.This mutual exclusiveness between DNA methylation andspecialized chromat<strong>in</strong> organization is also observed for severalimpr<strong>in</strong>ted loci <strong>in</strong> mammals (Feil and Khosla, 1999).Investigat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> possible <strong>in</strong>volvement of HP1-like prote<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> heterochromatization <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>, Bongiorni et al.demonstrated <strong>the</strong> differential distribution and co-localizationof HP1-like prote<strong>in</strong> with heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>( Fig. 6 , Bongiorni et al., 2001). The authors used monoclonalantibodies raised aga<strong>in</strong>st HP1 prote<strong>in</strong> of Drosophila melanogasterfor immunolocalization as well as Western blott<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Planococcus citri . HP1-like prote<strong>in</strong> was detected <strong>in</strong> both <strong>the</strong>sexes but it is scattered over <strong>the</strong> whole genome <strong>in</strong> femaleswhile <strong>in</strong> males it is localised to <strong>the</strong> heterochromatic genome.This exclusive localization of HP1 prote<strong>in</strong> to heterochromat<strong>in</strong>was ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed throughout <strong>the</strong> cell cycle. Thus HP1 prote<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> mealybug dist<strong>in</strong>guishes between metaphase condensationand <strong>the</strong> condensation of <strong>the</strong> paternal set <strong>in</strong> males.Bongiorni et al. (2001) also provide evidence of appearanceof this prote<strong>in</strong> preced<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> onset of heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g males. They observed <strong>the</strong> presence of HP1-like prote<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> embryos at seventh cleavage, while Schraderhad proposed that heterochromatization of <strong>the</strong> paternal genome<strong>in</strong> male occurs at fifth cleavage. The appearance of achromocenter represent<strong>in</strong>g heterochromat<strong>in</strong> occurs <strong>in</strong> a waveCytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006) 47

Dra IMsp IPvu IISau 3A1λ/H<strong>in</strong>d IIIAse Ibp23,1309,4166,5574,3612,3222,027560nrc51Fig. 5. Middle-repetitive sequences are a part of NRC. Mealybuggenomic DNA digested with different restriction enzymes (as <strong>in</strong>dicatedabove each lane) and electrophoresed on 1.1% agarose gel was Sou<strong>the</strong>rnblotted and probed with 32 P-labelled DNA from nrc51 (an NRC-specificclone) was found to be a middle repetitive sequence as it hybridizesat several loci <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug genome. (Please see Khosla et al., 1999for details.)Fig. 6. Co - localization of HP1-like prote<strong>in</strong> and <strong>the</strong> heterochromat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>. The frames from left to right represent <strong>the</strong> immunosta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g/DNAsta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g as <strong>in</strong>dicated above <strong>the</strong> panels. Monoclonal antibodiesdirected aga<strong>in</strong>st HP1 prote<strong>in</strong> from D. melanogaster were usedfor immunosta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Punctate sta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g on all chromosomes of female(shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> encircled area <strong>in</strong> A), chromosomes <strong>in</strong>tensely sta<strong>in</strong>ed withDAPI are sta<strong>in</strong>ed with anti-HP1 antibody <strong>in</strong> nuclei from males (shownby arrows <strong>in</strong> B and C). C shows prometaphse cell (top right). Scale bar:10 m. Figure reproduced with authors’ permission. (Bongiorni et al.,2001.)from one pole of <strong>the</strong> embryo towards <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r and not simultaneously<strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong> nuclei (Bongiorni et al., 2001). Theseresults are different from those reported by Epste<strong>in</strong> et al.(1992), <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> authors used antibodies directed aga<strong>in</strong>st<strong>the</strong> entire prote<strong>in</strong> from a gene ( pchet 1) hav<strong>in</strong>g homology with<strong>the</strong> chromodoma<strong>in</strong> of HP1 of Drosophila. They failed to correlate<strong>the</strong> localization of <strong>the</strong> signals with <strong>the</strong> presence of heterochromat<strong>in</strong>(Epste<strong>in</strong> et al., 1992). In <strong>the</strong>se two <strong>in</strong>stances<strong>the</strong> authors may be deal<strong>in</strong>g with different prote<strong>in</strong>s, as it isnot clear if pchet 1 prote<strong>in</strong> shares only <strong>the</strong> chromodoma<strong>in</strong> or<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r regions also with HP1 prote<strong>in</strong>. In Drosophila, HP1is associated with constitutive heterochromat<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> observationsof Bongiorni et al. (2001) suggest an underly<strong>in</strong>g similaritybetween constitutive and facultative heterochromatizationprocesses and illustrate that <strong>the</strong>se two descriptions ofheterochromat<strong>in</strong> may not necessarily <strong>in</strong>dicate mechanisticdifferences <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> compromised functional state ofchromat<strong>in</strong>.There are a number of covalent modifications of histonesthat correlate with active and <strong>in</strong>active chromat<strong>in</strong> organization.Acetylation of histone H4 is an activat<strong>in</strong>g modification whilemethylation of lys<strong>in</strong>e 9 of histone H3 is an <strong>in</strong>activat<strong>in</strong>g modi-48Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)

Fig. 7. Detection of H4 trimethylated at lys<strong>in</strong>e 20 (Me(3)K20H4) <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>. Prometaphase male mealybugnuclei sta<strong>in</strong>ed with DAPI ( A ) show <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tensely sta<strong>in</strong>ed heterochromat<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> same fraction sta<strong>in</strong>s with antibodies aga<strong>in</strong>stMe(3)K20H4 (arrowheads <strong>in</strong> B ). ( C ) Merged image with DAPI pseudocoloured <strong>in</strong> red. Scale bar 5 m. Figure reproducedwith authors’ permission. (Kourmouli et al., 2004.)fication (Li, 2002). Association of <strong>the</strong>se modifications with differentiallyregulated homologous chromosomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>has been exam<strong>in</strong>ed (Ferraro et al., 2001; Cowell et al., 2002).A difference <strong>in</strong> histone H4 acetylation between <strong>the</strong> paternallyand maternally <strong>in</strong>herited genomes was reported based on immunolocalizationus<strong>in</strong>g antibodies raised aga<strong>in</strong>st histone H4acetylated on all four lys<strong>in</strong>e residues (Ferraro et al., 2001).They fur<strong>the</strong>r observed <strong>the</strong> retention of acetylation on metaphasechromosomes, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that such a modification couldbe a part of a cellular memory mechanism dur<strong>in</strong>g mitosis.Cowell et al. (2002) demonstrated that histone H3 methylatedat lys<strong>in</strong>e 9 (Me9H3) is associated with both constitutiveand facultative heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> different animal species.In <strong>mealybugs</strong>, <strong>the</strong>y observed co-localization of Me9H3 andHP1 prote<strong>in</strong>s (Cowell et al., 2002). They used anitibodiesraised aga<strong>in</strong>st syn<strong>the</strong>tic peptide derived from histone H3 trimethylatedat lys<strong>in</strong>e while <strong>the</strong> HP1 antibody was <strong>the</strong> same asthat used by Bongiorni et al. (2001). In case of both HP1 andMe9H3 a difference <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> nature of chromat<strong>in</strong> localizationbetween male and female <strong>mealybugs</strong> is reported ra<strong>the</strong>r thandifferences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> presence/absence of <strong>the</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> or <strong>the</strong> modification(Bongiorni et al., 2001; Cowell et al., 2002). This canbe expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> terms of association of <strong>the</strong>se factors not onlywith facultative but also constitutive heterochromat<strong>in</strong>.More recently, trimethylated lys<strong>in</strong>e 20 of histone H4(Me(3)K20H4) has emerged as a robust marker for constitutiveheterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> mur<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>terphase and metaphasecells (Kourmouli et al., 2004). Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> association of thismodification with heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> different contexts,Kourmouli et al. (2004) reported <strong>the</strong> presence of Me(3)K20H4 on facultative heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> mealybug maleswhile <strong>in</strong> females it was scattered throughout <strong>the</strong> chromosomesand no difference was seen between <strong>the</strong> homologues ( Fig. 7 ).However, <strong>the</strong>y did not f<strong>in</strong>d any association of Me(3)K20H4with <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>active X chromosome <strong>in</strong> female mammals.The data available on molecular dissection of parentalorig<strong>in</strong>specific heterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> suggests a majorrole for chromat<strong>in</strong>-associated factors ra<strong>the</strong>r than DNA meth-ylation <strong>in</strong> this phenomenon. Except HP1, which appears beforeheterochromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g embryos, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r modificationsof histones are associated with heterochromat<strong>in</strong>.Khosla et al. (1996) have shown association of nuclease-resistantchromat<strong>in</strong> not only <strong>in</strong> somatic nuclei but also <strong>in</strong> nuclearpreparations enriched with sperm-derived nuclei. In <strong>the</strong> lightof <strong>the</strong>se reports, a chromat<strong>in</strong>-based <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> mechanismappears as a dist<strong>in</strong>ct possibility <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>.Differential chromat<strong>in</strong> organization as a mechanism ofgenomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>In this proposal, we dist<strong>in</strong>guish between heterochromat<strong>in</strong>as seen <strong>in</strong> somatic nuclei and <strong>the</strong> status of <strong>the</strong> paternal genome<strong>in</strong> sperms. Heterochromat<strong>in</strong> is an end po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> a sequence ofevents that beg<strong>in</strong>s dur<strong>in</strong>g spermatogenesis <strong>in</strong> males. The earlyevents <strong>in</strong> this sequence do not result <strong>in</strong> conferr<strong>in</strong>g all <strong>the</strong>attributes known for facultative heterochromat<strong>in</strong>. In <strong>the</strong> presentcontext consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> experimental evidence known sofar, we assume N uclease R esistant C hromat<strong>in</strong> (NRC) as adist<strong>in</strong>guishable organization of <strong>the</strong> paternal genome that canbe assayed by biochemical and/or molecular methods andconsider it as <strong>the</strong> primary event. This is analogous to <strong>the</strong> ‘seed<strong>in</strong>gelements’ that Wolffe (1944) proposed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context ofma<strong>in</strong>tenance of cellular memory factors through mitosis.Thus, NRC is not equivalent to heterochromat<strong>in</strong> but is a steptowards achiev<strong>in</strong>g facultative heterochromatization. One of<strong>the</strong> features of spermatogenesis <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong> that wasdiscussed earlier and is relevant here is <strong>the</strong> complete segregationof paternal and maternal genomes from each o<strong>the</strong>r dur<strong>in</strong>gspermatogenesis and <strong>the</strong> subsequent dis<strong>in</strong>tegration of <strong>the</strong>nuclei conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> heterochromatized paternal genome(Brown and Nur, 1964). Thus, it is to be noted that <strong>the</strong> maternaleuchromatic genome is packaged <strong>in</strong>to functional spermsand <strong>the</strong>y are received <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> oocytes as <strong>the</strong> paternal genome.Therefore, we propose that follow<strong>in</strong>g fertilization <strong>the</strong> zygotehas <strong>the</strong> paternal genome <strong>in</strong> NRC positive and hetero-Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006) 49

Fig. 8. A diagrammatic representation of<strong>the</strong> model proposed for altered chromat<strong>in</strong> as amechanism of genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>.NRC – Nuclease resistant chromat<strong>in</strong>,NRC + state is assumed as an epigenetic mark<strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> <strong>in</strong> this model. Mat-Maternal genome;Pat-Paternal genome; Ht <strong>in</strong>t is an <strong>in</strong>termediatestate of heterochromat<strong>in</strong> which isNRC + but not cytologically heterochromatic,Ht + is facultatively heterochromatized genome,Ht – is genome without facultative heterochromat<strong>in</strong>i.e. euchromatic genome. The crossedovals represent <strong>the</strong> haploid nuclei conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> paternal heterochromatic genome that dis<strong>in</strong>tegratedur<strong>in</strong>g spermatogenesis.chromat<strong>in</strong> negative state ( Fig. 8 ). Only after <strong>the</strong> sixth cleavage<strong>the</strong> NRC positive paternal genome acquires a heterochromat<strong>in</strong>izedstate as observed by cytological parameters. Consider<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> factor(s) contribut<strong>in</strong>g to NRC formation, we can attributecerta<strong>in</strong> properties to <strong>the</strong>se: (i) <strong>the</strong>y can be prote<strong>in</strong>s orRNA, (ii) <strong>the</strong>y exhibit co-operativity <strong>in</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g, (iii) one ormore of such factors should have male-specific expressiondur<strong>in</strong>g spermatogenesis, (iv) <strong>the</strong>y should be auto-regulatory<strong>in</strong> nature, (v) <strong>the</strong>ir expression would be sensitive to environmentalcues ei<strong>the</strong>r directly or <strong>in</strong>directly, (vi) <strong>the</strong>y function asrecruit<strong>in</strong>g factors for heterochromat<strong>in</strong> mediat<strong>in</strong>g prote<strong>in</strong>s. At<strong>the</strong> cleavage stages when <strong>the</strong> developmental decision has tobe made <strong>the</strong>re will be a choice to be executed between ma<strong>in</strong>tenanceor loss of <strong>the</strong> NRC positive state concurrent with <strong>the</strong>choice of a male or female developmental pathway.The <strong>in</strong>teractions between oppos<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>fluences to direct afemale or a male developmental pathway would be similar to<strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of competitive b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g with cis- / trans- act<strong>in</strong>g factorsthat are so often encountered <strong>in</strong> developmental systemsstart<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> lytic versus lysogenic pathway <strong>in</strong> lambda50Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)

phage. Auto-regulation of critical factors is once aga<strong>in</strong> a familiarstrategy seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation cascade of wellstudiedsystems like Drosophila melanogaster (Black, 2003).The assigned properties of factors required to be a part of <strong>the</strong>chromat<strong>in</strong>-based <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> mechanism <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> canaddress most of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g observations made over <strong>the</strong>years <strong>in</strong> relation to sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation and genomic <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong> (Brown and Chandra, 1977).The importance of chromat<strong>in</strong> remodel<strong>in</strong>g and covalentmodification of histones result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> unique ‘histone code’ <strong>in</strong>ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> developmental fate of cellular l<strong>in</strong>eages is be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly recognized (Strahl and Allis, 2000; Jenuwe<strong>in</strong>and Allis, 2001). The role of chromat<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation and ma<strong>in</strong>tenanceof X chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation <strong>in</strong> female mammalsis also established. The transcript from <strong>the</strong> Tsix gene acts asanti-sense for Xist <strong>in</strong> cis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiation of X chromosome<strong>in</strong>activation. Recently, it has been shown that <strong>the</strong> transcription<strong>in</strong>hibition of Xist is mediated through modification ofchromat<strong>in</strong> structure (Sado et al., 2005). Fur<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenanceof <strong>in</strong>activation <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement of Polycomb repressivecomplex (PRC) has been demonstrated. The <strong>in</strong>itial labilestate of <strong>in</strong>activation with PRC is re<strong>in</strong>forced by DNA methylation,recruitment of MACROH2A and hypoacetylation ofhistone (Hernandez-Munoz et al., 2005). Thus, DNA methylationis a late event <strong>in</strong> X chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation as wellwhile modification of chromat<strong>in</strong> prote<strong>in</strong>s occurs dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiationeven dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>activation of <strong>the</strong> paternal X chromosome<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> extra-embryonic tissues of mouse.Most of <strong>the</strong> known examples demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g chromat<strong>in</strong> asa key determ<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>in</strong> global regulation allude to <strong>the</strong> stablema<strong>in</strong>tenance of chromat<strong>in</strong> code dur<strong>in</strong>g mitosis, <strong>the</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>ystem may provide an example of stable ma<strong>in</strong>tenance ofchromat<strong>in</strong> code through meiosis.AcknowledgementThe authors thank Drs. Giorgio Prantera and Prim B. S<strong>in</strong>gh for permissionto reproduce figures from <strong>the</strong>ir published papers.ReferencesAchwal CW, Iyer CA, Chandra HS: Immunochemicalevidence for <strong>the</strong> presence of 5mC, 6mA and 7mG<strong>in</strong> human, Drosophila and mealybug DNA.FEBS Lett 158: 353–358 (1983).Avner P, Heard E: X-chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation:count<strong>in</strong>g, choice and <strong>in</strong>itiation. Nat Rev Genet2: 59–67 (2001).Bennett FD, Brown SW: Life history and sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> diasp<strong>in</strong>e scale Pseudaulacaspispentagona (Targ.) (Coccidea). Can Entomol 90:317–325 (1958).Berlowitz L: Correlation of genetic activity, heterochromatizationand RNA metabolism. Proc NatlAcad Sci USA 53: 68–73 (1965).Black DL: Mechanisms of alternative pre-messengerRNA splic<strong>in</strong>g. Annu Rev Biochem 72: 291–336(2003).Bongiorni S, C<strong>in</strong>tio O, Prantera G: The relationshipbetween DNA methylation and chromosome <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> coccid Planococcus citri . Genetics151: 1471–1478 (1999).Bongiorni S, Mazzuoli M, Masci S, Prantera G: Facultativeheterochromatization <strong>in</strong> parahaploidmale <strong>mealybugs</strong>: <strong>in</strong>volvement of a heterochromat<strong>in</strong>-associatedprote<strong>in</strong>. Development 128:3809–3817 (2001).Brockdorff N: X-chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation: clos<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> on prote<strong>in</strong>s that b<strong>in</strong>d Xist RNA. Trends Genet18: 352–358 (2002).Brown SW: Lecanoid chromosome behaviour <strong>in</strong>three more families of <strong>the</strong> coccoidea (Homoptera).Chromosoma 10: 278–300 (1959).Brown SW: Chromosomal survey of <strong>the</strong> armored andpalm scale <strong>in</strong>sects (Coccidea: Diaspididae andPhoenicococcidae). Hilgardia 36: 189–294(1965).Brown SW: Heterochromat<strong>in</strong>. Science 151: 417–425(1966).Brown SW, Bennett FD: On sex determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>diasp<strong>in</strong>e scale Pseudococcus pentagona (Targ.)(Coccidea). Genetics 42: 510–523 (1957).Brown SW, Chandra HS: Chromosome <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>and <strong>the</strong> differential regulation of homologouschromosomes, <strong>in</strong> Goldste<strong>in</strong> L, Prescott DM(eds): Cell Biology: A Comprehensive Treatise,Vol I, pp 109–189 (Academic Press, New York1977).Brown SW, Nelson-Rees WA: Radiation analysis ofa lecanoid genetic system. Genetics 46: 983–1007(1961).Brown SW, Nur U: Heterochromatic chromosomes<strong>in</strong> coccids. Science 145: 130–136 (1964).Brown SW, Wiegmann LI: Cytogenetics of <strong>the</strong> mealybugPlanococcus citri (Risso) (Homoptera: Coccidea):Genetic markers, lethals, and chromosomerearrangements. Chromosoma 28: 255–279(1969).Cattanach BM: Control of chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation.Annu Rev Genet 9: 1–18 (1975).Chandra HS, Brown SW: Chromosome <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>and <strong>the</strong> mammalian X chromosome. Nature 253:165–168 (1975).Chandra HS, Nanjundiah: The evolution of genomic<strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>. Dev Suppl 1990, pp 47–53 (1990).Cowell IG, Aucott R, Mahadevaiah SK, Burgoyne PS,Huskisson N, Bongiorni S, Prantera G, Fanti L,Pimp<strong>in</strong>elli S, Wu R, Gilbert DM, Shi W, FundeleR, Morrison H, Jeppesen P, S<strong>in</strong>gh PB: Heterochromat<strong>in</strong>,HP1 and methylation at lys<strong>in</strong>e 9 ofhistone H3 <strong>in</strong> animals. Chromosoma 111: 22–36(2002).Crouse HV: The controll<strong>in</strong>g element <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> sex chromosomebehaviour <strong>in</strong> Sciara. Genetics 45: 1429–1443 (1960).Deobagkar DN, Muralidharan K, Devare SG, KalghatgiK, Chandra HS: The mealybug chromosomesystem I: Unusual methylated bases andd<strong>in</strong>ucleotides <strong>in</strong> DNA of a Planococcus species.J Biosci (India) 4: 513–526 (1982).Devajyothi C, Brahmachari V: Modulation of DNAmethyltransferase dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> life cycle of a mealybugPlanococcus lilac<strong>in</strong>us. FEBS Letts 250: 134–138 (1989).Devajyothi C, Brahmachari V: Detection of a CpAmethylase <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>sect system: characterisationand substrate specificity. Mol Cell Biochem 110:103–111 (1992).Epste<strong>in</strong> H, James TC, S<strong>in</strong>gh PB: Clon<strong>in</strong>g and expressionof Drosophila HP1 homologs from a mealybug,Planococcus citri . J Cell Sci 101: 463–474(1992).Feil R, Khosla S: <strong>Genomic</strong> <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> mammals:an <strong>in</strong>terplay between chromat<strong>in</strong> and DNA methylation?Trends Genet 15: 431–435 (1999).Ferraro M, Buglia GL, Romano F: Involvement ofhistone H4 acetylation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> epigenetic <strong>in</strong>heritanceof different activity states of maternallyand paternally derived genomes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybugPlanococcus citri . Chromosoma 110: 93–101(2001).Heitz E: Das Heterochromat<strong>in</strong> der Moose. JahrbWiss Botanik 69: 762–818 (1928).Hernandez-Munoz I, Lund AH, van der Stoop P,Boutsma E, Muijrers I, Verhoeven E, Nus<strong>in</strong>owDA, Pann<strong>in</strong>g B, Marahrens Y, van Lohuizen M:Stable X chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>the</strong>PRC1 Polycomb complex and requires histoneMACROH2A1 and <strong>the</strong> CULLIN3/SPOP ubiquit<strong>in</strong>E3 ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7635–7640 (2005).Hughes-Schrader S: The chromosome cycle of Phenococcus(Coccidae). Biol Bull (Woods Hole, Mass)69: 462–468 (1935).Hughes-Schrader S: A primitive coccid chromosomecycle <strong>in</strong> Puto sp. Biol Bull (Woods Hole, Mass)87: 167–176 (1944).Hughes-Schrader S: Cytology of coccids (Coccoidea-Homoptera). Adv Genet 2: 127–203 (1948).Hughes-Schrader S, Ris H: The diffuse sp<strong>in</strong>dle attachmentof coccids, verified by <strong>the</strong> mitotic behaviourof <strong>in</strong>duced chromosome fragments. JExp Zool 87: 429–456 (1941).Jenuwe<strong>in</strong> T, Allis CD: Translat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> histone code.Science 293: 1074–1080 (2001).Khosla S, Kan<strong>the</strong>ti P, Brahmachari V, Chandra HS:A male-specific nuclease-resistant chromat<strong>in</strong>fraction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug Planococcus lilac<strong>in</strong>us.Chromosoma 104: 386–392 (1996).Khosla S, Augustus M, Brahmachari V: Sex-specificorganisation of middle repetitive DNA sequences<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug Planococcus lilac<strong>in</strong>us . NucleicAcids Res 27: 3745–3751 (1999).Kourmouli N, Jeppesen P, Mahadevhaiah S, BurgoyneP, Wu R, Gilbert DM, Bongiorni S,Prantera G, Fanti L, Pimp<strong>in</strong>elli S, Shi W, FundeleR, S<strong>in</strong>gh PB: Heterochromat<strong>in</strong> and tri-methylatedlys<strong>in</strong>e 20 of histone H4 <strong>in</strong> animals. J CellSci 117: 2491–2501 (2004).Li E: Chromat<strong>in</strong> modification and epigenetic reprogramm<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> mammalian development. Nat RevGenet 3: 662–673 (2002).Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006) 51

Lyon MF: X chromosome <strong>in</strong>activation and <strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong>,<strong>in</strong> Ohlsson R, Hall K, Ritzen M (eds): <strong>Genomic</strong>Impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g: Causes and Consequences, pp129–141 (Cambridge University Press, NewYork 1995).Metz CW: Chromosome behaviour, <strong>in</strong>heritance andsex determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Sciara. Am Nat 72: 485–520(1938).Mohan KN, Ray P, Chandra HS: Characterization of<strong>the</strong> genome of <strong>the</strong> mealybug Planococcus lilac<strong>in</strong>us, a model organism for study<strong>in</strong>g whole-chromosome<strong>impr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g</strong> and <strong>in</strong>activation. Genet Res79: 111–118 (2002).Nelson-Rees WA: The effects of radiation damagedheterochromatic chromosomes on male fertility<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug, Planococcus citri (Risso). Genetics47: 661–683 (1962).Nelson-Rees WA: New observations on lecanoidspermatogenesis <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> mealybug, Planococcuscitri . Chromosoma 14: 1–17 (1963).Nur U: Meiotic par<strong>the</strong>nogenesis and heterochromatization<strong>in</strong> a soft scale, Pulvanaria hydrangeae(Coccidea: Homoptera). Chromosoma 19: 439–448 (1963).Nur U: Reversal of heterochromatization and <strong>the</strong> activityof <strong>the</strong> paternal chromosome set <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> malemealybug. Genetics 56: 375–389 (1967).Nur U: Translocations between eu- and heterochromaticchromosomes and spermatocytes lack<strong>in</strong>g aheterochromatic set <strong>in</strong> male <strong>mealybugs</strong>. Chromosoma29: 42–61 (1970).Nur U: Diploid arrhenotoky and automictic <strong>the</strong>lytoky<strong>in</strong> soft scale <strong>in</strong>sects (Lecaniidae: Coccoidea:Homptera). Chromosoma 39: 381–401 (1972).Nur U: Heterochromatization and euchromatizationof whole genomes <strong>in</strong> scale <strong>in</strong>sects (Coccidea:Homoptera). Dev Suppl, pp 29–34 (1990).Nur U, Chandra HS: Interspecific hybridisation andgynogenesis <strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>. Am Nat 97: 197–202(1963).Sado T, Hoki Y, Sasaki K: Tsix silences Xist throughmodification of chromat<strong>in</strong> structure. Dev Cell 9:159–202 (2005).Sager R, Kitch<strong>in</strong> R: Selective silenc<strong>in</strong>g of eukaryoticDNA. Science 89: 426–433 (1975).Scarbrough K, Hatmann S, Nur U: Relationship ofDNA methylation level to <strong>the</strong> presence of heterochromat<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>mealybugs</strong>. Mol Cell Biol 4: 599–603 (1984).Schrader F: The chromosomes of Pseudococcus nipae .Biol Bull (Woods Hole, Mass) 40: 259–270(1921).Schrader F: Experimental and cytological <strong>in</strong>vestigationsof <strong>the</strong> life cycle of Gosspypuria spuria (Coccidae)and <strong>the</strong>ir bear<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> problem of haploidy<strong>in</strong> males. Z Wiss Zool 128: 182–200(1929).Schrader F, Hughes-Schrader S: Haploidy <strong>in</strong> metazoa.Q Rev Biol 6: 411–438 (1931).Strahl BD, Allis CD: The language of covalent histonemodifications. Nature 403: 41–45 (2000).Wolffe AP: Inheritance of chromat<strong>in</strong> states. DevGenet 15: 463–470 (1994).52Cytogenet Genome Res 113:41–52 (2006)