SPORT SCIENCE - Professional Tennis Registry

SPORT SCIENCE - Professional Tennis Registry

SPORT SCIENCE - Professional Tennis Registry

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

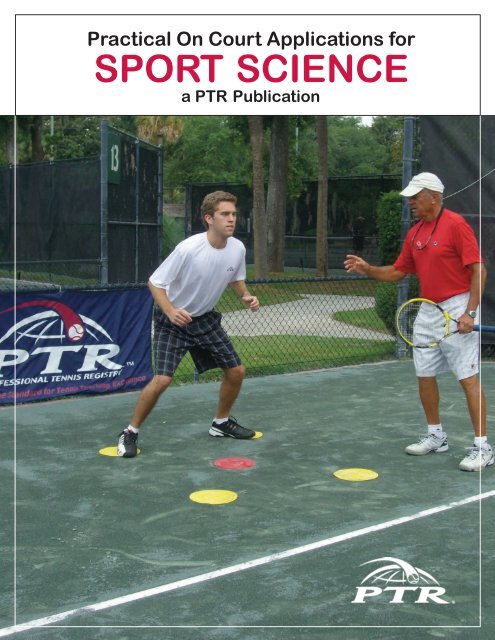

Practical On Court Applications for<strong>SPORT</strong> <strong>SCIENCE</strong>a PTR Publication

© 2012 <strong>Professional</strong> <strong>Tennis</strong> <strong>Registry</strong>All rights reservedReproduction of any portion ofPractical On Court Applications for Sport Scienceis not permitted without written consent of PTR.PTR logo is protected through trademark registration in the United States Office of Patents and Trademarks

ContentsAbout this Publication 3Part IWhat is Sport Science? 4Principles of Training <strong>Tennis</strong> Players 4The Physical Demands of <strong>Tennis</strong> 7Assessing Players 7Measuring Athleticism in <strong>Tennis</strong> Players 8Areas of Athleticism That Can Be Improved 11The Difference Between Strength and Power 11How the Kinetic Chain Works 12How Difficult or Easy Should Training Sessions Be? 13Planning Training and Playing Schedules - Periodization 14Heat Related Illnesses 17Hydration During Training and Matches 17Energy Systems 19The Most Common <strong>Tennis</strong> Injuries and Prevention 25Best Practices for the Warm Up 30Best Practices for the Cool Down 31Recovery Tips 31Strength Training 34Plyometrics 35Deliberate Practice 36Additional Literature and Resources 37PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 1

Part IIDynamic Warm Up Exercises 38Rotational Walking Lunges 38Hamstring Walk - Inchworm; Spiderman Crawl 39Froggers; Scorpion Stretch 40Trunk Twists with Rotational Lunge - Helicopters; Rapid Response Base Rotations 41Arm Hugs; Wipers 42Cheerleaders 43Essential Cool Down Stretches 44Calf Stretch; Lying Hamstring Stretch 44Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch; Piriformis Stretch; Knee to Chest Stretch 45Crossed Arm Stretch; Sleeper Stretch; Wrist Flexor Stretch 46Shoulder and Upper Arm Exercises 47External Shoulder Rotation 4790/90 External Shoulder Rotation; Lateral Shoulder Raise 48Upper Body Exercises 49Rotational Pull - Lawnmower 49Single Arm/Single Leg Row; Push Ups (Tricep Push Ups) 50Suspension Chest Press 51Exercises to Strengthen/Stabilize Core and Hips/Glutes 52Side Plank with Hip Abduction 52Side Plank Rotation; Russian Twist 53Kneeling Superdog (Bird Dog); Glute/Hip Bridge 54Quadruped Hip Extension; Dumbbell Squat 55Power Exercises with a Medicine Ball 56Medicine Ball X Drill 56Medicine Ball Mini-<strong>Tennis</strong>; Forehand and Backhand Tosses Using . . . Stances 57Medicine Ball Granny Toss; Medicine Ball Overhead Toss 58Medicine Ball Chest Pass; Medicine Ball Rotational Lunge 59Lower Body Exercises 60Monster Walk; Alley Hops 60Box Jump 61Exercises to Strengthen the Serve 62Single Arm Rotational Pull; Overhead Triceps Extension 62Shotput Serve; 90/90 Catch and Throw 63Single Leg Jump to Romanian Deadlift 64Drills for Speed, Agility and Footwork 65Figure 8 Drill - Lateral and Linear 65V-Volley Drill; Spider Drill 66Lateral Crossover Drill; Lateral Shuffle Drill with Crossover Recovery 67Additional Resources 68Online Resources 69References 70PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 2

About this PublicationSport science is an integral part of performance enhancement in tennis. Coaches and tennisprofessionals are always seeking ways to help players improve. For that reason, there is anabundance of research and many textbooks on sport and exercise science applicable totennis. The intent of this publication is to provide a compilation of some basic sport scienceinformation relevant to tennis coaches.It is directed to the many coaches working with competitive players, even 10 to 12 year oldswho are starting to compete, to senior league players. It is meant as a practical resource foron court training. Therefore, some subjects, such as lifting free weights during the off season,are not specifically addressed in detail, since tennis coaches typically do not supervisestrength and conditioning. At many schools and major academies, a strength and conditioningspecialist with certification from NSCA or iTPA can implement those modalities of training.At clubs, personal trainers can often supplement on court training.This PTR publication is divided into two sections. Part I addresses topics that will interesttennis coaches. Part II includes some of the best training exercises. Although this resourcecannot cover all of the exercises available in more comprehensive books and videos, it ishoped that providing some of the more interesting exercises can improveperformance of players, while keeping training stimulating.It is important for tennis coaches to stay within their own scope of practice, and to understandwhen to seek the services of a professional in the field of sport science (sport physiology,biomechanics, nutrition, sport psychology, strength and conditioning) to appropriately traintennis players.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 3

PART IWhat is Sport Science?Sport science involves the practical application of sciences toward human physical activity,namely competitive sports and exercise. These sciences include exercise physiology, sportsmedicine, biomechanics, sport psychology, sports nutrition, kinesiology, motor learning andother fields. Additional sport sciences include recent technological advances in materials(e.g., clothing that is advantageous for athletes) and the application of physics andmathematics.This PTR publication will focus on biologically based sport science involving humanperformance enhancement and training athletes. Applied biological sport sciences includesports medicine and injury prevention, exercise physiology, and competitive performanceenhancement, which is this publication’s main focus.With the game of tennis evolving, it is important to include the latest information that canhelp coaches better train athletes of all skill levels.Principles of Training <strong>Tennis</strong> PlayersPractical uses of tennis specific sciences may help an athlete improve endurance, movementor power. <strong>Tennis</strong> specific applications include those improving movement, racquet skills,recovery, energy systems, injury prevention and general training.In training, there are several basic exercise physiological principles:• Specificity• Adaptation• Loading• Recovery and Reversibility• Individuality• VarietyPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 4

SpecificitySpecificity means employing training methods that are mechanically and metabolicallysimilar to those used in a particular sport. Some training methods may be useful for manysports and may not resemble skills specific to tennis. Mechanically specific trainingincludes engaging muscles in activities that mimic tennis strokes or movement. Thesetraining methods that resemble tennis movement or skills are called tennis specific.Metabolically tennis specific training includes utilizing energy systems employed in a tennismatch and using similar work/rest intervals. More general or nonspecific exercises providea good foundation for athletic skills.AdaptationAdaptation refers to how the body changes in response to the demands placed on it.The body adapts to appropriate stress or load. Adaptations occur to improve body functionduring stress or load. For example, running will make the body adapt to better utilizeoxygen at the cellular level. Lifting heavy weights will increase strength and muscle size(i.e., hypertrophy) over time.LoadingProgressive loading refers to applying a greater than usual load of stress on the body thatenhances performance without risking injury by overtraining or overuse. Applying greaterthan usual stress is known as overloading. In addition, as the athlete improves andadaptations occur, the amount of load or stress can increase. Therefore, a highly trainedathlete can work at higher loads due to physiological adaptations. Poorly trained athletesmust start with lesser loads, since their bodies have not yet made adaptations and injuriesmay be more likely.Loading involves challenging the athlete, but not to the point of overtraining or injury.An important related concept is perceived exertion, the effort the athlete feels was made.For example, after a tough session, an athlete might feel s/he gave an effort of 9 out of amaximum of 10. Athletes should be taught to gauge perceived exertion to increase bodyawareness and recovery using a scale of 1 to 10. 1 represents sitting and relaxing, and10 represents that hardest possible workout the athlete has ever undertaken and cannotcontinue.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 5

Recovery and ReversibilityRecovery and Reversibility are related principles in training. Both refer to time spentbetween training sessions. Recovery refers to proper pacing and time spent on restbetween sessions, or between exercises during a session, to allow the athlete to train andimprove. If insufficient time is given for recovery, an athlete will not be able to improveperformance in training or actual match play. Instead, insufficient time can fatigue the bodyand increase risk of overuse injuries or overtraining. In addition, too long of a recoverymay not challenge the athlete sufficiently, and even allows detraining or reversibility.Likewise, if an athlete is injured, often a long inactive period of rest follows. During thistime period, the athlete can experience a decline in physiological adaptations (e.g., themuscles get weaker). That decline is referred to as reversibility. In short, if an athletedoes not train regularly, the gain in performance may be lost. Typically over a period oftime greater than two weeks, muscular endurance is lost more easily than muscularstrength. There is a minimal amount of training for a well conditioned athlete to avoiddetraining effects. For example, running twice per week at near maximal effect may wardoff aerobic detraining. Often athletes in the off season still remain physically active.That activity is known as active rest.IndividualityIndividuality refers to the differences between individual tennis players. Some may needadditional leg strengthening, while others may need greater flexibility, and still others mightneed higher muscular endurance. In addition, surfaces, gender, age, skill level andindividual styles should be addressed in training.VarietyVariety means the use of different exercises for the same purpose. An athlete can getbored or stale by doing the same routines. Changing the pace helps keep the player freshand motivated. Slightly changing exercises also helps the athlete use muscles in differentways that facilitates general athleticism and coordination of the tennis player. Using avariety of exercises also helps recovery from difficult days.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 6

The Physical Demands of <strong>Tennis</strong>There are numerous studies examining the physical demands and characteristics of tennis. 1-6According to these studies, tennis points generally last 4 to 10 seconds, with 20 seconds restand 90 seconds between changeovers. A typical clay court rally lasts 6 to 8 seconds and ahard court rally lasts 4 to 6 seconds. Therefore, the work:rest ratio in tennis ranges typicallyfrom 1:2 to 1:5. A player might change directions 3 to 6 times during a typical rally. Movementis usually lateral along the baseline, and 80% of movement between strokes is 8 feet or less. 6Because of the stop and go nature of tennis, the sport is mostly anaerobic, but requires goodaerobic capabilities to help during recovery between points. During a typical singles match,the heart rate can reach 190 beats per minute and drop to 110 during changeovers. 5-8 A typicalplayer might burn 300 to 2,000 calories in a singles match, which could last anywhere from 45minutes to 3 hours, depending on the quality of rallies, skill level, age, gender and body weight.Assessing PlayersThere are three general ways to measure an athlete’s training or performance. First, a coachcan work with an athletic trainer, physical therapist and/or certified tennis performancespecialist, to screen physical weaknesses and strengths of individual athletes. Thatinformation is highly useful in determining how an athlete should train to help avoid injuriesand optimize performance. That same information may also help determine what loads andintensities the athlete can undertake. For example, a tennis player might have poor shoulderstability and therefore needs strengthening before attempting to develop a powerful serve.Second, a coach might also initially test tennis players for athleticism. For example, a coachmight have a leg strength test, a sprint test and an agility test. There are some well knowntests, including the Spider Drill (see Page 66). The results can help a coach determine howpractices might incorporate more movement drills. Testing might also help motivate a team totrain harder. A coach can announce a fitness testing day in which players can endeavor toexcel.Third, a coach might track progress of players and periodically test athletes during the seasonor from year to year. Young athletes, who are growing fast, might find such tests fun andmotivating. A director of junior tennis may find tracking highly motivational and useful indeveloping an overall junior program. There are many tests that give typical scores fordifferent ages.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 7

Screening for physical deficiencies should be performed by a knowledgeable athletic trainer,physical therapist and/or certified tennis performance specialist.Assessment and testing can track an athlete’s weaknesses and progress. The USTA has aHigh Performance Profile that includes a battery of tests that assess stability, flexibility andstrength. It is advisable to work with an appropriate healthcare provider who can implementthese assessments and provide appropriate feedback.Assessments can be made with many different tests, as long as they are specific to tennis orinjury prevention. Traditional tests include BMI (body mass index), 20 Meter Shuttle Test(aka Bleep Test), Spider Drill Test for agility, Hexagon Test, and the Sit and Reach Test forflexibility. It should be noted that an athlete may be flexible in some areas but not in others, socoaches should assess the legs, hips and shoulders separately.The ITF website has a battery of tests that are useful for coaches:http://www.itftennis.com/scienceandmedicine/conditioning/20 Meter Shuttle - http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3184250Hexagon Test - http://www.itftennis.com/scienceandmedicine/conditioning/testing/agility.aspSit and Reach Test - http://www.itftennis.com/scienceandmedicine/conditioning/testing/Spider Drill - see Page 66Measuring Athleticism in <strong>Tennis</strong> PlayersPTR has a partnership with Pat Etcheberry, the renowned strength and conditioning coach,who has a series of tennis specific tests. The Etcheberry Experience course has anabundance of exercises that prepares and improves the performance of tennis players.You’ll find very simple tests on the next two pages.http://www.etcheberryexperience.comPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 8

First Step (Service Line Repeaters) TestWith a racquet, players start halfway between the center line and a singles sideline.Players run laterally (may use side steps or crossover steps) from center to sideline andtouch the lines with the racquet. Do this for 30 seconds, counting how many lines playerscan touch. Rest 30 seconds and then repeat. Rest again and repeat a third time. This drillmeasures tennis fitness and lateral agility (first step and change of direction). Comparewith good scores for different age groups.Band Jump TestTwo people hold a short (4 to 5 feet) rope or exercise tubing at either end 18 inches abovethe ground. You may also tie the tubing to chairs or other objects, but the height must be18 inches above and parallel to the ground. The athlete jumps laterally side to side overthe rope for 30 seconds. Rest 2 minutes and repeat. Use the best score and comparescores. With smaller players, or inexperienced 12 and under juniors, it may be wise to use12 or 15 inches as height for the rope.Etcheberry <strong>Tennis</strong> Specific Fitness Tests 830 SecondBand JumpFirst StepAge Male Female Male Female10 29 25 37 3212 31 27 40 3514 33 29 42 3716 34 30 44 3918 35 31 45 4021 36 32 46 41Pro 38 33 48 4340 34 28 42 3750 29 25 N/A N/A60 26 22 N/A N/APTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 9

Areas of Athleticism That Can Be ImprovedLike all sports, tennis requires athleticism. Although some individuals are natural athletes,many people can be trained systematically to improve their athleticism. Often playingdifferent sports develops skills that may be useful for tennis. For example, playing soccer(international football) is excellent for improving footwork in tennis. Participating in differentphysical activities is known as cross training.Basic components of athleticism that should be trained include:• Balance• Flexibility• Agility• Muscular Endurance• Cardiovascular Endurance• Speed• Muscular Strength• PowerA tennis player may be strong in some areas, but need improvement in others. Childrenrequire development in all areas, but usually their load is far less than older individuals. Manyareas can be started early when training children, but it must be understood that some areaswill have limited improvement due to limitations in hormone production and other factors.The Difference Between Strength and PowerMany people confuse the last two components of athleticism - strength and power. Strengthis the ability to exert maximal force. For example, lifting a very heavy object requires strength(regardless of the time it takes to the lift the object). Power is the combination of strength andtime over which the force is produced. Lifting a very heavy object quickly requires more powerthan lifting it slowly.Applied to tennis, loading the legs and driving a big forehand requires more power than hittinga drop shot. In addition, a serve traveling 125 mph requires powerful use of the body. Speedisn’t power, since it doesn’t discriminate between loads or stress. Rather, power is related to(strength) x (speed).PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 11

How the Kinetic Chain WorksMost coaches and teaching pros have heard of the kinetic chain. It is described as using partsof the body, normally starting from the ground up, to transfer energy successively from bodypart to body part. Typically, legs act on the ground, transferring energy to the hips, core,shoulders, upper arm, forearm, and finally the hand, in that order.One might commonly see a stroke with mostly arm motion, and understand that the legs werenot applying force. Normally, such a stroke would generate less power.The well known teaching term loading refers toan initial downward, eccentric musclecontraction, also known as a countermove.That downward movement allows the body toadd and store energy that can be released laterin the stroke. For example, if a tennis playerhad to jump vertically, s/he would first bend theknees, get low and store energy beforeexploding up and jumping into the air. Thekinetic chain results in a summation of forcesor impetus resulting in hitting the ball.Toni LanzoSequence of the kinetic chain is critical. If, on the forehand, the arm moves before the legsload, then the legs don’t contribute to generating power. The term timing also refers to thekinetic chain. Timing of the links is important. For example, a hitch in the serve can reducethe power generated from the rest of the service motion. A hitch loses the momentum of theracquet swing.Finally, it is important to note that kinetic chain results in optimal use of the body. It isn’t aguarantee of maximal acceleration or optimal hitting. For example, a proper kinetic chainmight occur on the serve, but the racquet face doesn’t make accurate contact, resulting in amishit. In addition, if the racquet face moves due to an improper grip, loss of power couldresult.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 12

How Difficult or Easy Should Training Sessions Be?Training should always be designed around a competitive or playing schedule. Not only areappropriate exercises selected and varied to maximize a tennis player’s preparation, but alsoexertion in training depends on the competitive or developmental schedule. For example,training before and after a major competition should be light. If an athlete won’t be on courtduring a month, then the training regimen could be more challenging.In other words, training should be planned. In addition, take into account other factors, suchas chronological age, training age, tennis age, injury and general condition of the athlete.A 60 year old will train differently from a 21 year old college athlete, who also trains differentlyfrom a 12 year old. A 21 year old college player will train differently from his 21 year oldroommate who plays tennis a few times a year. Not only is the college player more fit, s/hehas greater coordination and experience in undertaking different exercises. A college playercoming back from a minor injury might not have trained in the past three weeks and lost someconditioning, resulting in training that may be lighter, even though the player has the sametraining age and experience as her teammates.There are principles that govern how training sessions are conducted.Intensity refers to the rate of work done, which is relative in terms of the athlete orabsolute in terms of actual work done. Different ways of measuring intensity includerating of perceived exertion, percentage of maximal heart rate, percentage of maximumweight lifted (i.e., % of one repetition maximum), etc.Volume is the total training load as a function of (intensity) x (duration).For example, lifting heavy weights for a long time is high volume.Frequency refers to the number of training sessions in a given period, most oftenper week. However, highly trained athletes may use multiple sessions per day.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 13

Planning Training and Playing Schedules - PeriodizationAthletes train around schedules, whether playing junior tournaments, USTA leagues, on highschool or college varsity programs, or the pro tour. It is important to map out a schedule,perhaps for the next 3 to 4 months (e.g., a high school season) or the full year (e.g., ATP Tour).An individual player, parent or private coach can select a personal playing schedule. Inselecting a schedule, it is important to prioritize which events are more or less significant.Other considerations in setting a schedule include school, work and personal obligations.The concept of training to peak in a schedule is known as periodization. Organizing variousaspects of training for a given time period greatly aids performance peaking during the mosthighly competitive phases of the season. A tennis player can also set goals and can approachtraining with greater commitment and discipline. Expectations are more clear, and injuries andovertraining become less likely.In a long term period, often given as a year, there are three basic phases: preparatoryphase, competitive phase and transition phase. The preparatory phase consists of thegeneral preparatory phase and the specific preparatory phase.The general preparatory phase typically focuses on developing a foundation for generalathleticism. Often, this phase involves the athlete coming from a less active transition phasewhere some detraining might have occurred. Therefore, the tennis player needs to graduallyincrease load and prepare for higher intensity in later training. General endurance andstrength training are essential components of this phase. For high school or college players,this phase might last several weeks. <strong>Tennis</strong> technical changes should be initiated in thepreparatory stage, since there is time before the season to make adjustments. For example, aplayer might work on changing the grip and loading position on the serve. Technical changesmay need a couple months to practice before major competition.The specific preparatory phase is usually closer to the competitive phase, when athletes aremore prepared for higher intensity and volume. Some training will be tennis specific, andindividual goals become more important. Technical skills are refined and tactical patterns maybe practiced to implement new skills. Deliberate practice combining technique and tactics isimportant. Practice may be semi-closed skilled, meaning for a particular session, rather thanworking on general groundstrokes, when the athlete might work on taking the ball early on theforehand or inside-out inside-in forehand patterns. A player working on a grip change (in theprevious paragraph) may now be working on placement, spin and pace, and how to set up thenext shot. That allows more specific, deliberate practice.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 14

Between the preparatory phases and the competitive phase is the pre-competitive phase,which becomes increasingly tennis specific. Resistance training may mimic tennis strokes andmovement. In the preparatory phase, general strength is emphasized, but in thepre-competitive phase, strength is combined with speed to focus on power. For example,medicine ball and plyometric drills are power based exercises that require strength and speed.Skills may include more match play and drills in an open-skill environment. In addition, atransition phase may occur before the pre-competitive phase to allow recovery from highvolume, high intensity training in the preparatory phase.In the competitive phase, tennis players might have a busy schedule lasting several months.Competition for college and professional players is constant and occurs several times over aweek, as opposed to adult or junior players, who primarily play on weekends. Even highschool players encounter multiple events per week. A primary concern is maintenance ofphysical conditioning and abilities gained in the preparatory and pre-competitive phase.Training tends to be light to moderate, rather than heavy, so endurance, strength and powershould be maintained rather than enhanced. Lighter training, including agility and flexibility,can easily be incorporated.In the peaking phase, an athlete must be ready for optimal performance in major events. Theathlete is already competition ready, so recovery from minor events and staying injury free areessential. Training tends to be lighter, and psychologically, the athlete must be confident andfocused.After peaking, an athlete enters a transition phase where active rest keeps him or her at abase fitness level. The player might take a month or more off from competition, but might hitlightly and have enough training to maintain a minimal level of fitness and not detrain. <strong>Tennis</strong>players may also do other physical activities and cross train to exercise muscles differently.<strong>Tennis</strong> places highly asymmetric demands on the body (due to the forehand and serve), sobalance is important to reduce stress on the body. Psychologically, the player may assesswhat happened in the season and begin to plan new goals and a new schedule. In reality,self assessment is ongoing and athletes may constantly adjust goals, schedules and training.During the off season, s/he may consider major adjustments. The cycle repeats itself afteractive rest in the transition phase when the athlete begins to get ready again andre-enters the preparatory phase.A young tennis player, who is on a high school team and doesn’t play much outside the team,might follow a more traditional periodization plan. A junior tournament player would follow amore year-round program, similar to that of a touring pro, except with less intensity and moreoff time, especially during the academic year.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 15

Periodization for Players who Compete Year-roundPeriodization evolved out of the Eastern European athletic training system where nationalchampionships, world championships and the Olympics were the primary events.Therefore, there were often periods of little competition and only a few major events forwhich to prepare.However, tennis is an individual sport that is possible to play year-round. Many strongjuniors play, not only on the high school team, but in USTA tournaments. College playersplay and train in the summer, despite no college season. USTA Summer League playersmight play in other competitions or leagues during the rest of the year. And ATP and WTAtouring pros play nearly year-round. That makes the principle of individuality significant inplanning, but also diminishes the role of traditional periodization.In addition, consider giving at least one month off from competition a couple times duringthe year, where there is at least a three week competitive gap. For many juniors, March toAugust will be the most intense period with high school and USTA tournaments. Given that,a few suggestions can be made for the player with a busy competitive schedule. If a playeris not an active, Step 7 can be eliminated.1. Plan and write up the competitive schedule (6 to 12 months).2. Highlight the peak competitive events (up to 3 or 4 most important ones).3. Set goals around the season and peak events.4. Allow a transition and active rest period (or off season) sometime after the lastmajor competition or in the gap between major events.5. Consider several (up to 6) other major events.6. Examine the gaps between the 9 to 10 peak and major events. There should be2 to 8 weeks between most of them, annually.7. Consider general psychological and physiological feelings when deciding toincrease or decrease competition and training. If the player has been verysuccessful winning, more matches will be played, and hence, consider being moreselective and dropping some events.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 16

Heat Related IllnessesDue to the length of matches and typical hot weather, tennis players are susceptible, not onlyto dehydration, but also to heat illnesses. Heat cramps, heat exhaustion and heat strokes arethree types of heat illnesses. Many juniors battle in arduous summer tournaments and getdehydrated. Even spectators get heat illnesses, as tennis events often don’t have enoughsheltered areas. It is advisable for tennis coaches to have some First Aid certification.Understanding emergency and heat illness protocols 10 is essential.Heat cramps are the mildest form, and involve muscle spasms caused, in many instances, bythe imbalance of electrolytes and lack of appropriate hydration. Proper hydration, rest andstretching are helpful to combat heat cramps.Heat exhaustion is more serious. Symptoms include normal or elevated body temperature,heavy sweating, dizziness, nausea, weakness, rapid pulse, headache, and the skin appearsflushed or cool and pale. If heat exhaustion is suspected, get the person to a cool areaimmediately, have him drink fluids and remove excess clothing. Apply cool, wet cloths(e.g., towels) to the victim and consider immersion in a cool bath.Heat stroke is dangerous, even life threatening. Symptoms include increased bodytemperature of over 104˚F (40˚C), disorientation, shallow breathing, rapid weak pulse,disorientation, irregular heartbeat and hot red skin. The skin may be dry or moist (if playing).The body can no longer regulate temperature and, if left untreated, cardiac arrest and braindamage are possible. Call emergency or 911 immediately, move the victim to a cool place,and give the victim fluids. Remove excess and wet clothing from the victim, turn him on hisside and fan him. Apply cold compresses near wrists, neck, head, torso, ankles and groinareas (near large arteries). Body temperature must be lowered immediately.Hydration During Training and MatchesProper hydration is critical for optimal performance. Given the extreme heat and sunexposure, dehydration can be debilitating for performance. There is a significant amount ofliterature available on hydration, and the short list (next page) of best practices is useful forcoaches and players alike. Performance drops off when as little as 2% of body mass(i.e., water) is lost. 11,12 Players may sweat as much as 2.5 liters per hour and lose 4 to 7pounds per hour, if not replenished 13 . Most players tend to drink at 1+ liters/hour, which isn’tenough to replace fluid loss. However, not only water must be replaced, but also electrolytes -mostly sodium (Na + ). Sport drinks that help replace electrolytes are helpful for matches longerthan one hour.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 17

1. Be aware of the temperature, humidity and sun exposure that day.2. Encourage larger water jugs, rather than just water bottles, on warm days.3. Use sport drinks during long matches or on hot days. It is helpful to bring both waterand sport drinks.4. Encourage players to drink about 12 to 16 ounces one hour before going on thecourt.5. Drink 4 to 8 ounces after the warm up and during every changeover. On humid, hotdays, consider drinking even more.6. Suggest players weigh themselves before and after matches. Drink about 20 ouncesof fluid for each pound lost.7. After a match, drink and eat to replace carbohydrates. Salty carbohydrate foods,like chips, can help replace lost electrolytes.8. Especially after the match, educate players about the urine color test, where urineshould be fairly clear.Urine Color Chart1.2.3.If your urine matches the colors 1, 2 or 3,you are likely to be properly hydrated.Continue to consume fluids at the recommended amounts.Nice job!4.5.6.7.8.If your urine color is below the RED line, you may beDEHYDRATED and at greater risk for heat related illness!!YOU NEED TO DRINK MORE!Speak to a health care provider if your urine is dark andis not clearing despite drinking fluidsHypohydration (i.e., dehydration) can dangerously impair performance. In addition,hyponatremia can be a serious, but rare, condition in tennis athletes. Hyponatremia occurswhen electrolytes are lost in large amounts and large amounts of water is ingested. Wateralone does not replace electrolytes, but instead disrupts proper cellular functioning.Ultra-endurance athletes, such as triathletes, often face possible hyponatremia. In tennisplayers, it is rare. If your players have exceptionally long matches, encourage them to eatand use sport drinks, rather than just drink water alone.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 18

Energy SystemsHow many calories does a tennis player burn in a match?The amount of energy expended in a match depends on the intensity, duration, size, age,gender, body type, skill level, length of rallies, and style of play. There is an abundance ofliterature on sports and calories expended, 14-16 much of which refers to the average person.Typically 300 calories per hour and 450 calories per hour are given for doubles and singlesfor an average sized person, which does not take into account weight variations and otherfactors.Because of the large number of variables, it is difficult to gauge accurately caloriesexpended in a tennis match. A heart rate monitor can better estimate an individual’s energyexpenditure, but there are many factors even a heart rate monitor can’t account for, suchas percent of body fat. Leaner athletes burn more calories, since muscles require moreenergy. The following table was compiled from various sources. 14-16Energy Expended in Competitive <strong>Tennis</strong>Energy = number below x body weight in pounds x hours playedDoublesSinglesRecreational Player 1.5-2.5 x BW x hrs play 2.5-3.5 x BW x hrs playCompetitive Player 2.0-3.25 x BW x hrs play 3.0-5.0 x BW x hrs playAccordingly, a 175 pound competitive male might burn 525 to 875 calories. The low end ofthe range might be for an aggressive baseliner on a hard court. The high end of the rangemight be for a counterpuncher with long rallies on a clay court. The low end might also befor a 60 year old 4.0 league player, while the high end might be for a college player. A 125pound female recreational player might, therefore, burn 187.5 to 312.5 calories in an hourof play.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 19

Caloric and Nutritional NeedsToday, there is a great awareness of healthy diets. A very active athlete usually should eatmore than a sedentary person, because the athlete burns more calories.In general, there are five major food groups: grains, vegetables, fruits, dairy and protein(meat/beans). A sixth group, oils, is ingested in small quantities. Dietary Reference Intakes(DRIs) were created by the National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine and areincorporated into a simple graphic (below), which is available online atwww.choosemyplate.govThis website helps people make smart, healthy choices in diet.A tennis player might burn 500 to 1,500 calories in a match, but they will need significantlymore during the entire day. The total calories used in a day for an inactive person is knownas the basal metabolic rate (BMR). It is for maintenance of body functions at rest. Inaddition, even the food you eat requires energy to digest.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 20

Glycemic Index in Determining Pre-Match MealsGenerally, an active tennis player will require more calories, and those would come mainlyfrom carbohydrates. Not all carbohydrates are created equally however, as some takelonger to digest, and hence, produce energy more slowly for the body. Some foods aredigested quickly to become energy sources. Since they break down quickly, they raise theblood glucose and insulin. These foods are known as having a high glycemic index (GI).Diabetics have been long aware of these foods, and try to restrict their intake. Foods thatbreak down slowly and don’t raise blood glucose and insulin rapidly have low GI.If a player is in a three hour match and needs some energy quickly late in the competition,sport drinks and sugary foods provide quick energy, since they have high GIs. If a player iseating hours before a match, and wants to use the food more effectively as energy, s/hemay choose to eat foods with low GIs. For example, before a late morning match, a playermay choose a breakfast of bran cereal with blueberries and milk. Milk, blueberries (andmost fruits) and bran are low GI foods.After a tough match, a player should replenish for the next day’s competition, and usinghigh GI foods immediately after a match can be helpful. In addition, a light protein snack(e.g., yogurt) is best utilized by the body in the minutes after a match. Sometimes, anathlete might eat some pretzels, a moderate to high GI food. Bananas, commonly used fortennis matches, are moderate GI foods.The International GI database, as run by the University of Sydney (SUGiRS, SydneyUniversity Glycemic Index Research Service) is an excellent source to look up the GIs offoods.www.glycemicindex.com© USDAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 21

Protein Consumption for <strong>Tennis</strong> PlayersBecause athletes are more active, resulting in more muscle changes (i.e., breakdown andrepair) than the average person, the muscles need extra protein for repair. Proteins are themost abundant molecule types in the body and are found in all cells including muscles.Protein is utilized in cell membranes, body organs, hair and skin. Protein is also needed toform blood cells. When broken down into amino acids, proteins serve as precursors tonucleic acids, hormones, and are used by the immune system and for cellular repair.Major sources of proteins include meats, eggs and dairy. Vegans and vegetarians shouldeat a combination of legumes, grains, seeds and nuts, since proteins in these substancesare lower quality and need to be combined to supply essential amino acids for the body.Chicken is usually 30-33% protein, a hamburger can be 25-35% depending on fat or leancontent, and fish is in the range of 21-30% protein by weight typically. Yellowfin tuna hasone of the highest protein contents among fish. 17Much higher than meats, however, are some cheeses and beans. Parmesan cheese andmature roasted soybeans are around 40% protein. Hard cheese, and some softervarieties, such as Swiss, mozzarella and Romano, have 30% protein by weight. Soybeansrank the highest in protein among beans, and less mature, smaller beans drop in proteincontent. Soybeans are the only vegetable with high quality proteins like meats. Cheesealso has high quality protein.In addition to protein content, to find the nutritional value of many foods, visit the USDANational Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 24 online.http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/listKanko*PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 22

Special Considerations for Different AthletesTeenagers and children usually eat and burn many more calories than adults of the samesize. Young people tend to be physically weaker with higher centers of gravity (due togrowing and larger head to body ratio). Because they are growing, they also need moresleep as the body grows and repairs itself.Besides teenagers, other population differences include between men and women, youngchildren, mature athletes and special populations. Everyone is a bit different, so needs,even within the same age group, can vary. On a team, a coach might implement a baseprogram of skills and fitness, but some players may need additional work on core or legstrength. Others may need additional training in agility or endurance.In general, young children require basic athletic skills as a priority. Learning tends to beconcrete (as opposed to abstract), and basic movement and coordination skills are primaryconcerns. In addition, stability and balance are also valuable for a child’s motor learning.For example, skipping, balancing on one foot, turning directions, and coordinating handsand feet, are some of the main tasks for a child.Mature adults often have less flexibility, poorer balance and decreasing muscle mass.Decline in fast twitch muscle fibers and loss of muscle mass might reduce power or speedon the court. Hence, coaching mature players may involve different tactics (e.g., shorterpoints and less topspin) and different playing styles. On the other hand, training matureathletes off court can be highly valuable to maintain muscular strength, power, balance andflexibility. Finally, of course, they should get regular check ups and clearance from theirphysicians.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 23

Special Considerations for Female AthletesSome female athletes face complex issues regarding nutrition and health. 18 In training,many young female athletes have relative weakness in the knees, which tend to go inward(sometimes referred to as knee valgus position) when they lower the body or jump. Oftendue to weak hip stabilizers, hamstrings and landing, this effect (knee valgus) is oftenconnected to ACL injuries among female athletes. About 75% to 90% of ACL injuries areamong females. In rigorous movement, the ACL moves and may get pinched, which canrupture or tear the ACL. Research shows that neuromuscular training can help reduce ACLinjuries. 19 Essentially, that means when doing jump plyometrics, it is recommended to trainwith good form and to gradually build strength and complexity over time, especially withfemale athletes.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 24

The Most Common <strong>Tennis</strong> Injuries and PreventionDr. Pluim and co-workers 20 conducted a comprehensive study of all research literature ontennis injuries from 1966-2006. They found great variance in the studies due to lack ofmethodology, meaning the studies had different conclusions since they were not consistentwith each other. Problems that typically arise include defining injury severity in terms of timelost, requiring treatment or hospital admission, or costs per injury. On extremes, some studiesinclude blisters and sunburns as injuries, while others only include acute injuries requiringemergency hospital visits. Several studies investigating gender found no significantdifferences between men and women, although some studies indicate there may be amarginally higher rate of injury among men. Some studies found that there is little effect of skilllevel on injuries. That is, a higher level player might be as likely to get injured as a novice whomight be under less stress (e.g., slower balls, slower movement), but is less trained and,therefore, might get hurt despite lower stressors.Most injuries in tennis are microtraumas, often overuse injuries. Microtraumatic injuries aremore common in the upper body and extremities. Acute macrotrauma (i.e., sudden injuriesinvolving a single force) usually occurs in the lower body. A typical macrotrauma might be asprained ankle. Common upper body injuries include lateral epicondylitis (i.e., tennis elbow),medial epicondylitis (golfer’s elbow), rotator cuff tendinitis, muscle strains and stress factures.Among young players, growth plate injuries may also occur.In a review, Kibler and Safran 21 reported that among junior players, the most common area ofinjuries involve lower extremities (39% to 59%), followed by upper extremities (20% to 45%),and finally central core (i.e., head and torso) at 11% to 30%. Studies were fairly consistent inthat order. The two most common lower extremity injuries are the ankle and thigh. In theupper body, shoulder injuries are most frequent, followed by elbow injuries. That order forjunior players is probably reversed for older players given the higher number of one-handedbackhands among adults. Pluim et al reported the most common injury was tennis elbow withan incidence rate of 9% to 35% and prevalence rate of 14% to 41%, depending on the study.Keep in mind, however, that review was from 1966-2006, which includes many years theone-handed backhand was the predominant technique.In addition, juniors might put more stress on the shoulder due to too early learning of kickserves, poor use of legs for upward acceleration, and overuse of the back. Overextending theshoulder and weak shoulder stabilizer muscles can contribute to shoulder injuries, such asimpingement or rotator injuries. It is very important that teaching professionals ensure theirplayers learn the appropriate biomechanics of efficient strokes from a very early age. This notonly helps improve performance, it also reduces the likelihood of injuries.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 25

In an ongoing study at this writing, Kibler 22 also reports mechanical deficiencies in the servingmotion among touring pros, more common among WTA than ATP players. Ideally inacceleration phase, as the racquet swings upward to contact, players should use a pushingmotion from the back leg. Many WTA and some ATP touring pros were deficient in leg driveand cocking (i.e., properly setting the racquet in the backswing before accelerating forward).Rather, they used a pulling motion of the upper body.Avoid Shoulder Problems by Correctly Developing the ServeYoung players under age 10 may not be strong enough in the core or shoulder stabilizers tomaster a kick serve. The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the body, and young playersdon’t have enough muscle strength or stability to avoid injuries at this age. It is better toteach them the flat serve first and then the slice serve.Coaches should teach players to drive from the back leg to initiate the transfer of energy upvia the kinetic chain. Many players don’t engage the legs properly, but use an actionpulling the racquet up over the back to mainly create power. That action can put excessivestrain on the back and shoulders. After driving upward with the legs, a player can practicethe hip over hip and shoulder over shoulder movement. Teach players to rotate with thehips and shoulders, rather than separately rotating the upper arm and elbow backward.Clearly, the serve differs from groundstrokes on which most players spend significant timetraining and practicing. The serve involves greater stress on the shoulders. Kovacs andEllenbecker have developed specific exercises for strengthening the serve. 23,24 Exercisesfor Strengthening the Serve can be found on Pages 62-64.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 26

Preventing <strong>Tennis</strong> ElbowThere is no guaranteed way to prevent tennis elbow, but there are ways to help reduce thechances of getting it. <strong>Tennis</strong> elbow occurs more commonly with one-handed backhands,so one might adopt a two-handed backhand. <strong>Tennis</strong> elbow is much more frequent inrecreational level players than high performance players. It is important to understand thatpoor technique and high volume of training and competition are the two major causes oftennis elbow. However, the major factor is inappropriate technique, and this is somethingthat should be corrected by the teaching professional. It is recommended that coachesteach students to relax the grip, avoiding the tight ‘death grips’.There are two common types of elbow pain,known as lateral epicondylitis and medialepicondylitis. The former (i.e., lateral)occurs on the outside of the elbow. Thelatter occurs on the inside and is alsoknown as golfer’s elbow. <strong>Tennis</strong> elbowcan occur from tennis or golf, but also fromdoing other everyday activities, such aspainting, raking, working on cars, or evencooking.KoSAs with many other injuries, treatment begins with rest and ice. Resting several weeks iscommon. <strong>Tennis</strong> elbow straps have also gained popularity. The concept behind straps, orbraces, is to reduce the magnitude of muscular contraction and therefore, tension in theelbow area. Gradually, the brace should be used less and less.There are several forms of physical therapy, butrecently one exercise method has seenconsiderable success in studies. 25,26 This methodis a series of eccentric movements with an exerciseequipment called a flexbar, which looks like a gianttwisted licorice stick. There are also successful,simple resistance band exercises. Generally, therecent thinking has been to stretch and strengthenthe elbow tendon during eccentric contraction ofthe wrist extensors. For example, if you hold yourhand and arm outward palm down and let the wristflex down, you get eccentric contractions. Theflexbar creates a force that pulls the wristdownward and works the extensors, whichconnect all the way up to your elbow.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 27

Stretching for <strong>Tennis</strong>Stretching is commonly known as holding stretched positions for 20 to 30 seconds. Thisstatic stretching was thought to be good in the warm up, prevent injuries, and prepare thebody for physical activity. Today, however, dynamic stretching is considered moreappropriate in the warm up.In the past few years, this topic has been one of the hottest research areas in sportscience, in part due to the mixed results. 27-37 There are literally hundreds of studies, andsome suggest stretching does not prevent injuries, some are inconclusive, and somesuggest stretching helps prevent injuries. But the studies that show stretching helpsprevent injuries are far fewer. Most quality studies show that stretching does not reduceinjuries. In fact, most injuries are the result of eccentric muscle contractions, usually seenduring deceleration. For example, landing hard on the court after a forehand drive is aneccentric movement in the legs. The legs hit the court and suddenly decelerate, like hittinga wall. That resulting force is very high impact equal to several times more than a person’sweight. Going down a staircase is another example of eccentric muscle contractions in thelegs that places tremendous force on the legs. Going down stairs is harder on the legsthan going up a staircase. Stretching doesn’t eliminate these types of injuries.Instead, a proper dynamic warm up better prepares the body for sport specific movement,and helps reduce injuries. Static stretching is very important for improving range of motionand should be performed by a tennis player, but not immediately before training orcompetition. A dynamic warm up is more sensible and provides greater benefits to theimmediate tennis session.How Stretching Helps PlayersThere are three kinds of stretching: static, dynamic and PNF. Static stretching involvesholding stretches at near maximal range of motion (ROM) at the joints for typically 30seconds. They are important, particularly for certain sports like gymnastics, dancing orfigure skating, where excellent flexibility is necessary for performance.Dynamic stretching involves shorter ROM and does not require holding stretches,although different positions may be held for 2 to 3 seconds. In dynamic stretching,movement is controlled and steady. A more explosive stretching technique, known asballistic stretching, involves more quick, rigorous movements than dynamic stretching, anduses the momentum or weight of the body to assist movement, sometimes beyond itsnormal range and is not recommended for tennis players. Another stretching technique isAIS (Active Isolated Stretching), which involves short holds of 2 to 3 seconds to avoidactivating the stretch reflex, a protective mechanism that pulls back from the stretch.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 28

Stretching can also be defined as active or passive. Active is when the athlete isperforming the stretch. Passive is when the athlete is relaxed in the muscles beingstretched and is being assisted by another person or a machine.PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) stretches involve a series of holds,relaxations and muscle contractions. It is considered effective in increasing static orpassive flexibility. Usually done with an assisting partner, PNF stretches have three typesof routines, all starting with a passive stretch of 10 seconds. Because muscularcontractions occur at near maximal ROM, PNF stretches can improve flexibility andperformance.Static stretching is helpful to improve flexibility, but it is not recommended as a routinebefore serious competition, due to negative effects on power. 37-40 Although studies vary onexactly how long, static stretching is acknowledged to temporarily decrease muscularpower for at least 45 to 60 minutes. Static stretching does not help warm up the body, butdynamic stretching helps increase the muscle temperature, which literally warms up thebody. As the muscles warm up, oxygen supply to muscle fibers increases. Therefore,dynamic stretching is a more practical way to warm up and prepare the body.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 29

Best Practices for the Warm UpA warm up prepares the body for rigorous activity. A practical warm up for a tennis match orteam practice may last about 10 minutes, but 15 to 25 minutes is common among seriousathletes. The effects are an increase in blood flow, oxygen and body temperature by typically(1-2˚C), which allows muscles and tendons to become more flexible. Synovial joint fluidloosens up with movement and warmth, so the range of motion improves. A good warm uphelps reduce chances of injury and involves three phases for tennis: a light aerobic exercise,dynamic stretching and light hitting.1. Jog or do some light aerobic activity for several minutes.2. Add some light dynamic stretch for the legs, such as skipping or butt kicks.3. Continue with increasingly rigorous dynamic stretches and activities for the lowerbody.4. Add dynamic stretches for core, shoulders and upper body.5. End with some higher intensity exercises that involve the whole body or mimic tennisstrokes and movement.6. If playing in a tournament, about 25 to 30 minutes before the match time, go througha light warm up, starting with either jogging or biking, if there is a gym available.About 15 minutes building up to a moderate intensity should be sufficient. Then whenthe player actually gets on court with the hitting warm up, their body is ready to pushharder.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 30

Best Practices for the Cool DownDuring rigorous play or practice, blood pressure and heart rate are elevated. A cool downallows both to return to normal. The more rigorous the exercise, the more essential the cooldown. Static stretching is useful, since it can relax the muscles, which have gone through anumber of significant contractions during exercise. A cool down commences the recoveryphase.1. Slow down and let heart rate come down. Continue moving for a few minutes,especially if the exercise was intense. For example, if the practice ended withsprints or the match ended with a couple long points, walk around for a coupleminutes.2. Do light static stretching holding each stretch 15 to 30 seconds.3. Ice the legs and any body part susceptible to injury or soreness.4. Hydrate and consider having a snack.5. Start the recovery phase.Recovery TipsRecovery is about being fresh and ready for the next match or hard training session. Aftermatches or hard practices, a player needs time to bounce back from fatigue and musclesoreness. However, there are practices that help cut down recovery time, since often athletesneed to play another match in a tournament or for a team. Some practices are scientificallywell documented in aiding recovery, but others are anecdotal and may not have benefits.The hardest part of matches and training is working muscles eccentrically, such as in landingand turning directions after a stretched volley or groundstroke. When the muscles getoverworked, they become damaged and require repair. This overload effect is felt by theathlete and is known as delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which is soreness felt for aslong as 72 hours after a hard workout.Recovery also involves being mentally fresh. Staleness and burnout occur with athletes whoplace too much pressure on themselves, might not have direction or goals, or have negativeinvolvement from parents or others. To help reduce staleness, change court routines byadding some drills or games that are creative and different. Rotating and adding newexercises in training helps mentally, and physically may use the muscles differently.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 31

During a tournament, from match to match, considerable energy may be expended. Bloodglucose and glycogen in muscles need to be replenished. In addition, due to soreness anddamage or micro-tears, muscles require repairing. To help repair muscles and replenishenergy, carbohydrates and some protein should be consumed. If done within 45 minutes afterprolonged exercise (e.g., a three set tennis match), muscle repair and glycogen storage in themuscles can be significantly improved at a faster rate. As discussed earlier, high glycemicfoods are digested and processed by the body faster than other foods. Many food productsusing potatoes, corn and white rice have high glycemic indices. Many competitive andprofessional tennis players use low fat chocolate milk (or other drinks with a similarcomposition) as a recovery drink. Studies indicate that low fat chocolate milk has goodconcentration of carbohydrates (both low and high GI) and protein.The USTA produced a couple recent documents on recovery in tennis that are available online.The Recovery Project has a comprehensive review of studies and practices. Coaches,parents and trainers will find this resource valuable. The Recovery Booklet is more practicalfor players and coaches. The two resources can be found athttp://www.usta.com/tennisrecovery/The following are 10 suggested practices for recovery.1. Athletes should listen to their bodies. Ask your players how they feel after matches,and suggest ways to assist recovery and eliminate or modify the practices if matchesor training was particularly hard. Players may keep a journal or log to record theiractivities, nutrition, sleep and emotional states and feelings. Encourage all players totake 1 to 2 days off per week.2. Have an off season. Some juniors love competition and try to play year-round, whichcan hurt their progress, keep them fatigued, and accelerate burnout. Help plan theirtournament and training schedule.3. Be aware of player injuries and where the player stands in rehabilitation. Check whatis allowed or not. If there is an athletic trainer/physical therapist, find out directly,since sometimes athletes might miss information or want to practice despite thetrainer’s advice.4. Vary your drills or training sessions. Keep athletes fresh by adding a fun routine or aroutine that trains the body differently. At times, ask players what they’d like to do forgames.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 32

5. Educate athletes on proper hydration (see Page 17). They should be aware ofthe urine color test (see Page 18). With younger children, parents should also beeducated in what to provide. It is not unusual for juniors to bring inadequate supplyof fluids to camps or tournaments, which needs to be addressed from both thecoach’s and the parents’ perspectives. They should also know water is helpful forshorter matches, but sports drinks or snacks with water can help in longer matches.6. Help educate athletes on post play nutrition, such as eating a light snack (200 to 400calories) with some protein. Mentioned earlier was low fat chocolate milk, which isinexpensive and optimal. Alternatively, cheese and crackers or a small sandwichwith meat/fish or recovery shakes are also good choices.7. During a tournament, at the end of the day, players should eat a reasonably highcarbohydrate, medium protein, low fat dinner. At the end of the tournament,especially if play involved more than two matches, protein should be increased toassist muscle repair over the next few days of recovery.8. If you can, make ice and showers available. Encourage players to get off their feetand ice the legs to reduce tissue inflammation and accelerate healing. Ice anyunusually sore body parts as well.9. Taking a warm shower or bath helps stimulate blood flow, which helps quickenmetabolic activity and healing.10. Teach athletes how to relax and reduce muscle tension. Stretching routines afterplay are helpful. In addition, yoga, relaxation exercises and stretching at the end ofthe day or before bedtime are useful.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 33

Strength TrainingTraditional strength lifting (resistance training) involves heavy weights and movements slowerthan tennis strokes. However, strength, power and muscular endurance gains can besignificantly improved with appropriate strength training. In classic periodization, strengthgains are important in the general preparatory phase, well before the tennis season.Closer to or during the season, tennis specific exercises are more useful. Strengthmaintenance becomes more of a priority. In addition, power training becomes more important.Power combines strength and speed, and therefore, lighter loads are used in training.Because tennis movements require body rotation and relatively quick movements, lightertraining with medicine balls, bands, rubber tubing, combining to form more complexmovements, as on the groundstrokes or serve, become essential. In addition, training thebody to absorb stress, as encountered in changing directions or recovering after a serve, isimportant for injury prevention.Strength training is often seen as free weights or weight machines. However, there are manyways to build strength. Free weights help develop balance and proprioceptive skills better thanmachines. Many free weights are lifted concentrically (e.g., lifting a weight upward on theascent phase, during which muscles contract and shorten) and at slow to moderate speeds.However, eccentric contractions (e.g., lowering a weight on the descent phase, walking down aflight of stairs, during which muscles are lengthening) are very important in tennis, as this iswhat happens when a player decelerates and changes directions. 41 The force on the body inthe decelerative phase is significantly larger than the accelerative phase. In the loading phaseof a forehand groundstroke, the leg muscles, including the gastrocnemius, soleus andquadriceps, all contract eccentrically. Some core muscles also contract eccentrically duringtennis strokes and movement.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 34

PlyometricsPlyometrics exercises involve explosive, powerful movements. A plyometric exercise uses aninitial pre-stretch or countermove, which involves the stretch shortening cycle. There are threestages: a pre-stretch, a pause, and a shortening phase that releases the power. For example,to do a vertical jump, an athlete would first bend at the knees and hips, pause for a splitsecond, and finally jump.Plyometrics exercises are very specific to tennis, if performed correctly. They are useful indeveloping power and strengthening the body for the accelerative and decelerative forcesneeded in tennis movement. They help train stability and proprioception.Plyometrics is one particular training regiment in which one should carefully observe theprinciples of progression and overload. Bounding and depth jumps can exert significantforces on the body and should be developed gradually. Although some plyometric exercisesare demanding, light plyometrics should be in every tennis player’s regimen. For example,wheelchair athletes can use medicine balls to train the upper body.Is Plyometrics Safe for Kids?Original plyometrics from Eastern Europe were advanced explosive exercises incorporatingdepth box jumps and heavy medicine balls. Such high intensity plyometrics are notsuitable for children and depend on developmental and training age (i.e., experience withtraining routines). Children at play often do light to moderate forms of plyometrics ingaining coordination skills, including jumping jacks, leap frogs, hop scotch, skipping andhopping. Plyometrics for young children 42 are safe, provided they involve fun exercises oflow to medium intensity, including double hops over mini-cones or tennis court lines.Medicine balls for 10 year olds should weigh 4 pounds or less.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 35

Deliberate PracticeIn the early 1970s, H. Simon conceptualized the idea of ‘chunking’ (i.e., mentally grouping andassociating) information and the development of expertise as taking 10 years. 43 This concepteventually became the 10,000 Hour Rule, which states that it takes 10,000 hours of deliberatepractice to achieve expertise. In studying expertise in a multitude of activities, K.A. Ericssondeveloped the conceptual role of deliberate practice in the development of expertise. 44Because sports are governed by standardized rules and have quantifiable records, theyrepresent an excellent area for study. Essentially, there are three areas in which one canspend time on a sport like tennis: work, play and deliberate practice.The three are actually defined by the goals. For work, the goal is reward, such as earningmoney, ranking or making the team. Often, competition does not allow the tennis player tospend time on weaker technical and tactical aspects, since energy is focused on winning andusing strengths. For a touring pro, high school or college player, work might also be playing amatch. That sounds like play, but because there are rewards, such as money or getting ateam win and ranking, the motivational levels often differs from pure play. Work has benefits,since a tennis player can learn to compete better and feel something was achieved.Play (or playful interaction) has no goal system other than intrinsic value. Fun play isself-motivating and is inherently enjoyable, leading to the flow state, where a tennis playerbecomes immersed in the activity. Flow isn’t necessarily a competitive mental skill, but it canlead to ideal performance state, which is the optimal level of performance under stress. Thatimmersion is essential for commitment to the sport. It may help develop competitive mentalskills and better management of tactics and strategies. Often play, however, leavesrecognition and development of skills up to the student. Some students may not learn fromplay, and those students with better awareness and attention skills improve faster. However,play allows the athlete to become more inherently motivated without burnout.The third, deliberate practice, has the goals of improving performance. Deliberate practice ishighly structured, monitors progress, and includes tasks to overcome weaknesses. Unlikeplay, it is not inherently enjoyable, but instead requires focus and effort. Other thanimprovement, there are no rewards.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 36

A responsibility of team coaches is to direct the practice to developing skills and tactics that arebeneficial to the players. An athlete can choose to work on many things, but coaches shouldconsider how time should be spent to maximize benefits to the player. In other words, considerwhat is essential. If a coach normally has practice 3 hours per day and had to reduce it to 1.5hours, what would be kept and what would be dropped?Second, in developing technical or tactical skills, consider how specific the environment shouldbe to optimize learning. That is, if a coach wanted to improve the backhand, consider thepossible options: let the player rally backhand primarily; play a groundstroke game wherebackhands count extra; rally only crosscourt backhands; only feed the player short, high ballsto the backhand; or have the player mix backhand spin and direction.Third, consider what is being communicated to the player, as well as the player’s learningobjectives. The player might be improving footwork, learning a new grip, trying to play moreaggressively, or practicing a slice backhand.Last, consider what a player is learning and provide feedback on how much progress wasmade and when the skill is game ready.Sometimes team practices are hard work, where players run hard and hit manygroundstrokes. That type of session might feel inherently good to the players who felt theytrained hard, but it may not constitute deliberate practice. For example, many team playersprefer to hit groundstrokes, since they are comfortable with them, but if work is primarilyneeded on serving and doubles play, it is not an optimal practice. Research showssuccessful players spend more practice time improving weaknesses or areas that producegreater benefits.Additional Literature and ResourcesBesides PTR publications, there are several excellent resources for coaches. Recentpublications include ITF Strength and Conditioning for Coaches (edited by M. Reid,A. Quinn & M. Crespo, 2003), <strong>Tennis</strong> Training (M. Kovacs, W.B. Chandler, T.J Chandler 2007)<strong>Tennis</strong> Anatomy (E.P Roetert & M. Kovacs, 2011), Complete Conditioning for <strong>Tennis</strong> (Roetert,EP and Ellenbecker TS, 2007)Organizations that have resources include the National Strength and ConditioningAssociation (NSCA), American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), and International<strong>Tennis</strong> Performance Association (iTPA).www.nsca.comwww.acsm.orgwww.itpa-tennis.orgPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 37

PART IIThe information provided in this section has been provided by the International <strong>Tennis</strong>Performance Association (iTPA) and Pat Etcheberry.www.itpa-tennis.orgwww.etcheberryexperience.comDynamic Warm Up ExercisesThere are dozens of exercises and this short list is not to give a complete routine, but toprovide some of the more interesting and helpful exercises.Rotational Walking LungesStand upright with shoulders back, head straight, core and glutes contracted, and withhands together straight in front of the body at shoulder level. From this starting position,step forward with the right foot and bend the back (left) leg until the knee is approximately1 to 3 inches from the ground, directly under the left hip. At the same time, the right kneewill also bend 90˚, so the knee is directly over the right ankle. During the descent of thismovement, the hips turn toward the right so that the arms will aim 90° from the startingposition. Pushing with the back (left) leg will bring the left leg through, and then repeat thelunge movement by stepping forward with the left foot. Using a controlled tempo for eachmovement, repeat 10 to 15 times, alternating legs.Variation: use crossed arm stretch to assist shoulder turn.© iTPAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 38

Hamstring Walk - InchwormStart in a push up position with hands out in front of the body and legs straight. Keepshoulders back and head straight (head neutral position). Slowly walk toward the hands asfar as possible without allowing the knees to bend. Once the feet have reached as closeas possible to the hands and heels are pushed into the ground, slowly walk the hands outforward to create a new starting push up position. Complete multiple repetitions (5 to 10) ofthis movement.© iTPA © iTPASpiderman CrawlStand upright, then bend the knees and flex forward at the waist into a crawl. Keepshoulders and head straight(head neutral position). Take a small step with the left leg 45°forward/lateral. The hands are walked forward toward the left foot/knee. From thisposition, slowly bring the right hip around and crawl the right foot forward, and follow thesame process with the opposing leg. Keep butt and center of gravity as low as possible,while maintaining good posture and keeping head straight. Repeat this movement 10 to 15times for each leg.© iTPA © iTPAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 39

FroggersStand upright with shoulders back and headstraight. Extend arms straight out to the sides atshoulder height. Flexing the left hip, externallyrotate it to bring the knee up toward the armpit,and then immediately lower the leg to the ground.As the left leg moves downward, the samemovement is performed using the other (right) legand other side of the body. Maintain good bodyposition by keeping shoulders back and headstraight, as well as core and glutes contractedthroughout the entire movement. Repeat 10 to 20times on each leg while walking.Variation: may be done side skipping.© iTPAScorpion StretchLie prone face down on the ground with legs straight and arms straight out to side. Slowlyrotate the left hip toward the right while slowly bending the left knee, with the goal ofreaching the left foot toward the right elbow. Hold the end position for 1 to 5 seconds, thenreturn to the starting position. Repeat this movement using the opposite side of the body.Keep both shoulders on the ground. Do 16 to 20 turns or reps.© iTPAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 40

Trunk Twists with Rotational Lunge - HelicoptersStand with a wide base, feet more than shoulder width apart, with arms straight out to thesides. Turn to the right, bend the knees, and lower the body as if hitting a groundstroke.The feet may turn slightly. Arms will swing low and around the body. Keep arms fairlystraight. Turn back and straighten up at the same time to original position. Turn to left andrepeat the movement on that side. Turn back and straighten up to the original position.Start with a slow, controlled tempo with slight knee bend. Complete about 12 to 16 reps.The last few can be faster and with deeper knee bend.Rapid Response Base RotationsStart in a ready position with feet shoulder width apart, knees slightly bent, and armsslightly out to sides. Quickly hop and, while airborne, turn the feet about 30° to 45˚ to theright. Quickly rotate 60° to 90˚ back to the left (should be turned 30° to 45˚ to left). Quicklyhop back to the right. Turn over of the feet and contact time with the ground should be veryquick. Small arm swings and torso turn should be in the opposite direction of the feet turn.Do for about 15 to 20 seconds, then repeat.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 41

Arm HugsStand upright with shoulders back, head straight, core andglutes contracted. Hold arms straight out to the sides in linewith shoulders as if making a T shape with the arms and body.Palms should face forward. From this starting position, thearms are wrapped around the body with the aim of graspingthe back of the opposing shoulder (i.e., the left hand to theback of the right shoulder and vice versa). From this position,reverse the movement by opening the chest while taking thearms back and squeezing the shoulder blades together.Repeat this movement 10 to 15 times using a controlledtempo.© iTPAWipersStand upright with shoulders back, head straight, and arms out in front of the body. Slowlyraise the left arm, while simultaneously lowering the right arm. Change the direction of thearm movement and repeat in the opposite direction. Using a controlled tempo, repeat thismovement 10 to 15 times.© iTPA © iTPAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 42

CheerleadersStand upright with shoulders back, head straight, and hands down by the sides. Raisearms slowly out to the side and straight above the head with both palms touching at the topof the movement. From the top of the position, reverse the movement by bringing the armsout to the sides and then down in a circular arch. This movement should be repeated atvarying speeds and utilizing both supination and pronation of the arms. Repeat thismovement 10 to 15 times at a controlled tempo.Variation: can be done concurrently with lower body dynamic warm up exercises(e.g., jumping jacks).© iTPA © iTPAPTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 43

Essential Cool Down StretchesThere are hundreds of stretches and it’s quite simple to find them. Only a few are presentedhere, but they are among the best. Stretches here and on the next two pages tend to be morestatic.• Focus on slow, smooth movement and coordinated deep breathing• Inhale deeply → Exhale as stretching → Ease back slightly• Hold the stretch position for 15 to 30 seconds, while breathing normally• Stretch larger muscle groups first• Stretch the tight side first• Stretch within safe limits• Do not lock joints or bounceCalf StretchStart in a pike position, with the hands and feet onthe ground and the heels off the ground. Keepingthe lower back straight and legs straight, use gravityand body weight to press the heels slowly towardthe ground. Hold and repeat.Variation: may bend knees to stretch the soleus(straight legs stretch the gastrocnemius).© iTPALying Hamstring StretchLie supine and loop a towel, rope or stretchingstrap around the right foot. Bring the thigh closerto the body by pulling on the strap. Keep legstraight and both the back and left leg flat on thefloor. Hold and repeat.Variation: bend the knee to stretch the belly ofthe hamstring.PTR Practical On Court Applications for Sport Science 44