Mechanisation-Alluvial-Artisanal-Diamond-Mining

Mechanisation-Alluvial-Artisanal-Diamond-Mining

Mechanisation-Alluvial-Artisanal-Diamond-Mining

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

About DDI InternationalDDI is an international, nonprofit, charitable organizationthat aims to gather all interested parties into a processthat will address, in a comprehensive way, the political,social and economic challenges facing the artisanaldiamond mining sector, in order to optimise the beneficialdevelopment impact of artisanal diamond mining tominers and their communities within the countries inwhich the diamonds are mined.A major objective is to draw development organizationsand more developmentally sound investment into artisanaldiamond mining areas, to find ways to make developmentprogramming more effective, and to help bring the informaldiamond mining sector into the formal economy.More information on DDI International can be foundat www.ddiglobal.org, and we can be reached atenquiries@ddiglobal.org.www.ddiglobal.orgInternational Executive Offices1 Nicholas StreetSuite 1516AOttawa, ONK1N 7B7DDI International is registered in the United States as aNonprofit 501(c)3 Organization (EIN/tax ID number: 51-0616171© DDI International, 2010ISBN: 978-0-9809798-5-5Research by : Projekt-Consult GmbHBased on country studies by Yves Bertran, Shawn Blore,Nicholas Garett, Marieke Heemskerk, Estelle Levin,Harrison Mitchell, Baudoin Iheta, Geert Trappenier,Babar Turay, and Ghislain Lokonda YausuPhoto Credits: Front Cover and Photo 1: Shawn Blore,Photo 2, 3, 4, and 5: Michel ChapeyrouxFUNDERS OF THE STUDY: Association of <strong>Diamond</strong>Producing Countries of Africa (ADPA); DFID-UK;Government of Belgium.Publication funded by: DFID and USAID.Printed by: Bonanza Printing and Copying CentreDesign by: g33kDESIGNComplete research study in English only, available online.AbbreviationsAADM artisanal alluvial diamond miningAM artisanal mining / minerAPEMIN Apoyo a la Pequeña Minería (ASM support program in Bolivia)ARM-FLO Association for Responsable <strong>Mining</strong> and Fair Trade Labelling OrganisationASM artisanal small-scale miningATPEM Asistance Technique au Petit Exploitant Minier (Madagascar)BGR Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe (Federal Institutefor Geosciences and Natural Resources), GermanyBR BrazilCAR Central African Republicct. Carat (1 ct. = 0,2 g)DDI <strong>Diamond</strong> Development InitiativeDRC Democratic Republic of CongoEC European CommissionEITI Extractive Industries Transparency InitiativeFONEM Fondo Nacional de Exploración Minera, BoliviaGCD Ghana Consolidated <strong>Diamond</strong>sGH GhanaGRATIS Ghana Regional Appropriate Technology Industrial ServiceGTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit GmbHGY GuyanaKP Kimberley ProcessMCDP Mwadui Community <strong>Diamond</strong> ProjectMEDMIN Medio Ambiente y Minería (ASM support program in Bolivia)MSDP Mineral Sector Diversification Programme (Zambia)MSM medium scale miningNGO Non-Governmental OrganisationOSH Occupational Safety and HealthPASMI Projet d’Appui au Secteur MinierPMMC Precious Minerals Marketing CorporationPPP Pequeños Proyectos Productivos (Support program with ASM component in Colombia)PRIDE financial services provider to the personal and smallmicro medium enterprise markets in ZambiaSAESSCAM Small-scale-mining technical assistance and training service, DRCSAM Sustainable <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Mining</strong> (Support Programme in Mongolia)SDC Swiss Agency for Development and CooperationSL Sierra LeoneSSM small-scale miningUAP Unité d’apprentissage et de productionUNDP United Nations Development ProgramUS$ United States DollarUSAID United States Agency for International DevelopmentUV UltravioletWB World BankWGAAP Working Group on <strong>Alluvial</strong> and <strong>Artisanal</strong> Producers

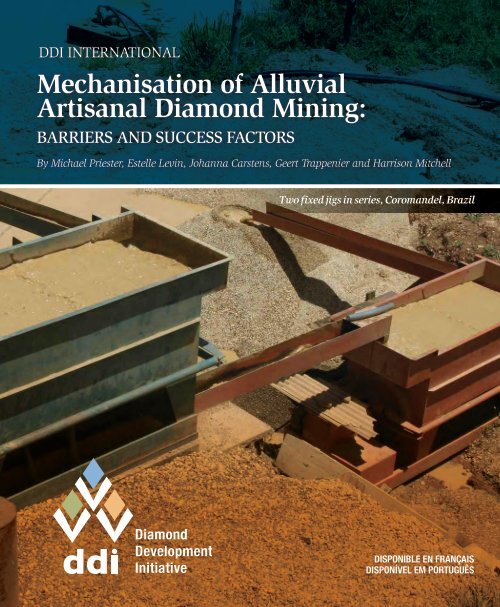

Table of Contents1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21.1 Desired development impacts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21.2 Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Current <strong>Mining</strong> Practices as aStarting Point for <strong>Mechanisation</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42.1 The actors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42.2 <strong>Mining</strong> Techniques. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42.3 Geology and Geography Determine the <strong>Mining</strong> Process . . . . . 42.4 Mechanization Approaches. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73 Key factors influencing the mechanisation process. . . . . . . . 83.1 Drivers for <strong>Mechanisation</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83.2 Key Barriers and Success Factors to <strong>Mechanisation</strong> . . . . . . . . . 83.2.1 Enabling environment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83.2.2 Socio-economic factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93.2.3 Technological factors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103.2.4 Geographical factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103.2.5 Programmatic Design factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103.3 The relation between the factors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114 Socio-economic and environmentalimpacts of mechanisation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125 Socio-economic and environmental impactsof mechanisation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135.1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135.1.1 SAESSCAM, DRC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135.1.2 Cooperating with industrial mines in DRC and Guyana . . . 135.1.3 Lessons learned from MEDMIN, Bolivia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135.2 Access to Finance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155.3 The cost-effectiveness of different typesand levels of mechanisation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155.3.1 Contracting/Rental vs. buying costs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155.3.2 Local wage levels vs. mechanisation cost . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155.3.3 Slow build or fast track . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 155.4 The Potential for Local Manufacture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166 Conclusion and Recommendations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176.1 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176.2 Key elements for a successful <strong>Mechanisation</strong> Programme . 176.2.1 Techniques for Encouraging Adoption andDiffusion of New Technologies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176.3 Proposals for Transversal Aid to the sector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176.3.1 Solving legal impediments to mechanisation . . . . . . . . . . 176.3.2 Guidance on best practice in AADM . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186.3.3 Develop further understanding of barriersand success factors for formalisation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186.3.4 Support formalisation of AADM byintegrating the sector in the EITI process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181. <strong>Artisanal</strong> miner, Coromandel, Brazil6.4 Proposals for pilot projects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186.4.1 Locally improve and adapt existing technologiesfor diamond concentration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 186.4.2 Support to suppliers of locally manufactured equipment . . 196.4.3 Experiment with targeted mechanisation services. . . . . 196.4.4 Support cooperation and cohabitation of ASMwith LSM/MSM enterprises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 Final Thoughts. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20List of FiguresFigure 1 – Process sequence of alluvial diamond mining . . . . 5Figure 2 – The factors grouped according to sphere ofinfluence and level of dynamic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11List of TablesTable 1 – Potential for manual and mechanised artisanalmining for different deposit types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Table 2 – Site of Manufacture for different types ofEquipment used in . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161

government and the diamond sector duringsix days in July 2010. Geert, who successfullymechanised a small scale diamond operation inGuyana, provided a case history of this project.◆◆In Brazil, Shawn Blore drafted previousexperiences from mechanisation of alluvialdiamond mining in the Coromandel area andcompared it to the situation of other AADMcountries (Guyana and Sierra Leone) inJune 2010.◆◆Guinea and Ghana were visited by YvesBertran Alvarez, who spent six days in eachcountry in June 2010 to investigate the issue.◆◆Sierra Leone was covered by Estelle Levin,Babar Turay and Harrison Mitchell. Harrisonconsulted stakeholders in Freetown overone day in June 2010. Babar, a local expert,consulted key stakeholders in the diamondmining areas over six days, also in June 2010.This assessment was completed by a deskcompilation of experiences by Estelle Levin,who has worked since 2004on AADM inSierra Leone.◆◆DRC was covered by Nicholas Garrett,Ghislain Lokonda Yausu and GeertTrappeniers. Nicholas discussed the barriersand success factors for mechanisation withlocal interview partners over two days in June2010. Ghislain, a local expert working withthe Congolese NGO CENADEP, supported thestudy by interviews with key stakeholdersover three days, also in June 2010. Geert,who successfully mechanised a small scalediamond operation in DRC, provided a casehistory of this project.Initially, it was assumed that projects supportingthe mechanisation of the ASM sector had existedin all countries. However, during the course of theresearch it became clear that in most countries,any mechanisation that had occurred was eitherself-driven or initiated by medium-scale miningcompanies cooperating with artisanals. The onlydocumentation on a project made available tothe team was a summary of an unsuccessfulmechanisation project in DRC carried out bySAESSCAM.There are three main reasons whyauthorities and development agenciesmight encourage mechanisation: toincrease productivity and maximizeprofit from a non‐renewableresource; to enable or encouragerationalization of production; andto improve the living and workingconditions of artisanal miners2. Battery of workers washingthe ore with sieves, Ghana3

DepositExploitation ofdiamond placersSituated below or near the groundand surface water levelSituated above the ground andsurface water levelDeviation of the river, drying up of parts of theriver bed, pumping off the ground and surfacewater, construction of dams, drainages or shaftsSoil and overburden removal: frontshovel loader, backhoe, trucks,shovels and wheel barrowsExploitation inthe river (wetexploitation):Pirogues, suctiondredge, dreg lineExploitation in artificial lakes(wet exploitation): Suctiondredge, drag line, backhoefor alimentation of a floatingconcentration plantHydraulicexploitation:“Monitoring” orgravel pumpingDry exploitation:Front shovel loader,backhoe, trucks,shovels and wheelbarrowsSlightly consolidated MaterialDisintegrationWashing sluiceSizing TrommelTransport of rough to the concentration plantLoose materialClassification, Feed hopper, Fixed screen,Shaking screen, Sizing trommelBackfill and renaturation:Front shovel loader, backhoe,trucks, shovels and wheelbarrowsConcentration ofdiamond placersGravity SortingHandpicking, Sluicing, Spiral concentrator, Heavy mediaseparation, Panning, Handjig, Mechanized jig, <strong>Diamond</strong> panSorting using thesurface propertiesGrease tableOptical Sorting withpneumatic separationRefining: HandpickingFinal ProductFigure 1 – Process sequence of alluvial diamond mining5

Table 1 – Potential for manual and mechanised artisanal mining for different deposit typesDeposit Type Manual artisanal mining process Mechanised artisanal mining process<strong>Alluvial</strong>, eluvialor colluvial depositon dry landPalaeoplacer,old terraces,placer with thickcoverage of sterileoverburden ondry land<strong>Alluvial</strong> depositsin rivers<strong>Alluvial</strong> depositsin riversOpen pits: <strong>Artisanal</strong> miners dig wells that can be 20 meters deep.They use picks and spades to dig and load the minerals, bucketsand bags to transport them, small pumps to evacuate the water,sieves to separate the gravel, and hand-picking to select minerals.This method is the most productive and least dangerous, but stillpresents some risks such as rock falls and injuries with picksand spades.Features for ASM: minimal investment required so low prefinancing(limited leadtime to reach the pay gravel dependingon the depth 1 ), operation in very small gangs possible, higherproductivity in deposits with shallow overburden, continuousoperation possibleUnderground galleries: <strong>Artisanal</strong> miners dig circular holes ofapproximately 90 centimeters diameter and typically up to 35meters deep (depending on the depth of the gravel). The gravelis charged in bags or buckets at the bottom of the gallery, thenevacuated with the help of a rope by a winch or pulley system,controlled by miners at the surface of the gallery. This methodpresents many dangers such as the lack of oxygen in the gallery,and the risk of rock falls and tunnel collapse.Features for ASM: rather limited investment required, low prefinancing(relatively short leadtime to reach the pay gravel),operation in very small gangs possible, relatively low productivity,problems with occupational safety, low recovery of the depositDiving: <strong>Artisanal</strong> miners dive in rivers, often without any divingsuits or breathing apparatus, and extract the gravel in buckets orbags. This is hauled to a pirogue that stays still at the surface withthe help of a bag of sand thrown in the water. After prospection,the miners pan manually separate gravel from minerals found atthe bottom of the river.Features for ASM: Difficult to perform, limited investmentrequired, low pre-financing (limited leadtime to reach the paygravel), operation in pairs possible, relatively low productivity,potentially huge problems with occupational health and safetywith drowning common, dependant on water level, currents andvelocity (seasonal activity)Dams and dykes: In the absence of dredges, artisanal minerssometimes build dykes with sand bags in the middle of rivers (i.e.in DRC, CAR, Sierra Leone etc.) to divert the water and extractdiamonds from the dry and isolated side. This method is dangerousas many miners have drowned as a result of dam breaks.Features for ASM: high investment required, large pre-financing(longer leadtime to reach the pay gravel), operation only inlarge gangs possible, relatively low productivity, problemswith occupational safety, extremely dependant on waterlevel (seasonal activity)1May take up to three weeks to reach pay gravelMechanised operation possible with a similarexploitation process (removal of overburden,exploitation of gravel by machinery, mechanisedtransport, concentration in mechanised washing plants)Mechanised operations require larger areas to befinancially viable, but facilitate higher recovery ofthe deposit and systematic mining processes withbackfilling, rehabilitation being more possible etc.With enough water available high (water)pressure monitoring and hydraulic transportis an option.Mechanised operation requires a completely differentmining process with open pit mining similar to theabove mentioned solution.The mechanised operation is characterised bymassive ground movement leading to higher costs foroverburden removal and higher environmental impacts.Miners use motor-pumps and hoses to evacuate pitsand galleries of water to enable continued accessin the rainy season.Dredging with suction dredges or elevator dredges;use of mechanical breathing apparatus and wet-suitsMechanised operations require a different miningprocess with dredging in the river similar to the abovementioned solution.Complex bedrock may require divers to maximisethe recovery of the diamond bearing gravel.6

83 Key factorsinfluencing themechanisation ProcessThe factors which determine mechanisation can bebroadly organised into the drivers, i.e. what makesit desirable, and the barriers and success factors,i.e. what makes it possible, or not.3.1 Drivers for <strong>Mechanisation</strong>The principal drivers for mechanisation arecommercial, socio-cultural and environmentalreasons. With the view to economics the minersexpect higher returns due to the faster exploitation,less effort, higher recovery and security as well asa safety gain. This is combined with a higher socialreputation and social status as a consequenceof the mechanisation. Finally, miners expectto overcome seasonal limitations to artisanalmining and get access to deeper deposits. Eitheralone or in combination, the commercial driversincrease the likelihood and potential size of profit,so helping miners achieve greater financial gainand independence. With so much to gain, the keyquestions then are: what are the barriers preventingartisanal miners from mechanizing? And what arethe factors ensuring success when someone doesattempt to mechanise?3.2 Key Barriers and Success Factorsto <strong>Mechanisation</strong>Whilst there are indeed technical reasons whymechanisation is sometimes not possible,desirable or successful, other factors can be evenmore important. These include the existenceor non-existence of certain political, legal,financial, cultural, organisational, or demographicconditions, or the inability of miners to accessthese conditions even if they do exist.3.2.1 – Enabling environment 3The political order in the country and the miningregions influences the potential for mechanisationby affecting the investment climate and theoutlook for success of mechanisation projects (i.e.conflict or post-conflict situation vs. stable politicalenvironment with effective institutions).The administrative requirements forformalisation potentially pose many traps formechanisation projects. In many systems thereare numerous incentives for miners to remaininformal. Getting a digging operation licensed canbe enormously time consuming and expensive.The legal framework of licensing in somecountries (e.g. Sierra Leone, Guinea) prohibitsmechanisation for ASM licenses directly ordiscourages it indirectly. There are legal barriersor a complete lack of mechanisms to evolve fromlegalised ASM to mechanised operations. On theother hand, a legal system allowing “tributor”agreements between a title holder and ASM (suchas in Ghana between GCD and the diamondmining groups) poses favourable conditions formechanisation.The capacity and will of local or nationalauthorities to enforce the law influences thepotential for mechanisation by affecting theinvestment climate. The requirement of registeringequipment, excessive or informal taxation on thoseusing machines, and corruption relating to theaccess or use of machines can all disincentivisemechanisation. In countries with fragile governancestructures (i.e. Guinea and DRC) the mechanisationof ASM has tended to proceed very slowly, whilein countries with a stable political economy andimplementation of the legal framework (i.e. Braziland Guyana) the modernisation of exploitationis quite advanced.3This covers the political environment, legal, institutional andcommercial issues setting the frame for mining activities in a country

Access to land and land rights (security of rights)are again important for the security of investment.Access to finance is a key determinant for thepossibility of mechanisation 4 .Access to existing support measures maybe a determinant for mechanisation. Existingprogrammes to support the ASM sector, such asPMMC (buying the ASM product), GCD (providingtributor agreements to artisanal miners) 5 orGRATIS (providing equipment) in Ghana, havealready established relationships of trust with theminers and may draw on their local experience aswell as on their networks.Existence of formal companies with a positiveattitude towards artisanal miners has proven tobe the most efficient element to enhance technicaldevelopment of ASM.3.2.2 Socio-economic factorsThe legal status of the ASM operation has to beconsidered before mechanisation. 6 <strong>Artisanal</strong> minershave their own perspective on formalisation andfrequently see a lot of advantages in the informal status.Attempting to use mechanisation as a lure for artisanaldiamond miners to formalise requires additionalsensitisation interventions. The internal organisationof the artisanal miners and their socio-economicdependencies play a key role. In African countries,particularly those recovering from conflict, the level oforganisation tends to be lower than in Latin Americawhere a culture of associations and cooperatives existsand ASM societies have more stable organisational4Awareness must be created that, even though the lack of finance isperceived as a crucial constraint, this is often the consequence of otherconstraints of the business or person, such as a lack of managementskills or lack of capitalisation due to traditional repartition schemes forthe revenues (Priester 2005).5Yves Bertran, verbal communication: this tributor system helpedthe ASM in Ghana a lot in getting fair payment, access tofinance and having investment security . Also, from this agreement,there was considerable technical know-how transfer from thecompany to the tributors, which supported the mechanisation.6Governments tend to see mechanisation as a tool to promoteformalisation. This view is not shared by the artisanal miners.relations. 7 The dependence of artisanal miners onfinanciers also impedes their ability to benefit from thefinancial gains that mechanisation can bring becausethe financiers might capture the difference.The role of ASM within the individual or householdlivelihood strategy: Miners who regard mining as theirprofession and main livelihood are more likely to investin machines; those who use it as a supplementary orseasonal activity around their other, principal livelihood(especially in the agriculture sector) are less likely tomechanise.The level of mobility of ASM influences themechanisation process. In some countries with a higherdegree of mechanisation, mobile equipment adapted tothe realities of local ASM operations has been observed.The trading chain is an important factor to beconsidered for a mechanisation intervention. Buyers/traders usually have strong links with artisanal miners,often being in a superior position to them and havingdecisive roles in the selection of the mining processesand equipment because they pre-finance the diggersor provide them directly with equipment. Lackingmarketing and diamond evaluation skills furthercement these dependencies.The cost of labour is an important factor for theeconomics of mechanisation. Research comparing thecost of labour (Blore 2008) in different countries (Brazil,Guyana and Sierra Leone) and putting it in relation tothe level of mechanisation confirms the considerableimpact wage levels have on mechanisation. Low costof manual labour discourages mechanisation as thecheaper the labour, the less economic it is to mechaniseReal and perceived benefits or losses for keystakeholders can incentivise or disincentivisemechanisation. Especially those influenced by miners’perceptions might not be very obvious and thereforehave to be investigated carefully.7See country study Brazil, particularly on the duration of commercialrelationships of miners and financers, and country study DRC,particularly on the presence of vested interests, unpaid securitygroups, military elites etc. benefiting from the status quo and thushindering miners to become organised in cooperatives.9

10General education levels and knowledge ofmining specific information (i.e. legislation, bestpractice etc.) may influence willingness andcapacity to achieve a higher level of mechanisation.Especially where mining skills have been acquiredon the job in traditional artisanal operations theattidude to innovation is generally negative. 8Customs and traditions can have a strong influenceon the mechanisation process. Interventions at thisstage must aim at changing behaviour and have tobe given adequate time to have an effect.3.2.3 – Technological factorsAccess to appropriate technology is paramount:proximity of manufacture, supply, maintenanceand support services, the quality of the equipment,and the adaptation of the technology to regionalconditions and traditional practices determine theacceptance by the miners. In Brazil and Guyana,for instance, both countries where mechanisationis advanced, there are clearly distinguished nationaltechnology solutions developed and provided locally.Trust in the new technology is important forminers to adopt it. With an unknown technologythe artisanal miners often fear that material can bestolen or may disappear during processing. 9 At thesame time, artisanal miners do not want to wastetime testing new equipment that might turn out tobe useless for them. International experience fromartisanal mining of various minerals shows that“Lighthouse projects” with positive experiencesor proven successes of the innovation 10 play animportant role in the successful dissemination of anew technology.Knowledge about the parameters of the miningoperation is important before starting mechanisationin order to avoid unpleasant surprises.8There is a strong link between the disposition to innovate and addresstechnical challenges on the one hand and the ability to lead or acceptmechanisation on the other.9See experiences from Latin American ASM projects on gold inWotruba et al. (2005)10Many projects fail to develop trust in new technologies byexperimenting prematurely with non-proven technologies.The level of training and know-how in how tomanage, use, and maintain the new technologydetermines how easily it will be adopted andhow sustainable the introduction of the newequipment is.Security considerations are also importantwhen attempting to increase mechanisation ofan operation. Due to increased mechanisation ahigher concentration of value occurs and thereforethe operations may be more prone to theft if accessto machines is not sufficiently restricted, especiallyat the point of accessing the pay gravel. On theother hand, using machines for concentratingdiamonds limits the number of people who handlethem, and thus may also minimise opportunitiesfor theft by workers. 11 Here again the cooperationwith formal enterprises provides extra security.3.2.4 – Geographical factorsThe geological, geomorphologic and hydrauliccharacteristics of the deposit influence theviability of mechanisation. These factors cannotbe altered by a project. But diamond grade, size,quantity and quality, the parameters of the gravel(particle size and composition), the thickness andcharacter of overburden, the groundwater table,the availability of surface water, the level of waterduring rainy and dry seasons are all enormouslyimportant in determining which mining processis optimal.The remoteness of the ASM operation also affectsthe chances of mechanisation.3.2.5 – Programmatic Design factorsExperience suggests that projects have a greaterchance of success where the community is coowneras well as beneficiary. This means that theminers also participate in project development,execution, and monitoring. If mechanisation isself-organised and community-driven it is morelikely to succeed, and also has significant positive11This is why many people use the Plant in Sierra Leone as theirmachine, because diamond theft occurs most at the washing stage.

spin-off effects for the self-empowerment of thepeople involved, so helping communities takecharge of their own development agenda.3.3 The relation between the factorsThe key factors influencing the mechanisationprocess have been sorted into external and internalas well as static and dynamic factors in an attemptto advise possible interventions. The externalfactors are those that are beyond the influenceof the artisanal miners. An intervention tacklingthese factors must be addressed by other parties,such as the government, NGOs etc. Internal factorsare those which are directly within the sphere ofinfluence of the artisanal miners. Static factorswill be more difficult and require more time to bechanged while dynamic factors can be changedmore easily.Figure 5 below attempts to group the factorsaccording to who has influence over the factor andhow dynamic the factor is.geology/geographicposition ofdepositpoliticalorderlandrightsadministrativerequirements forformalisationlicenseprovisionsaccess tofinanceExternallawenforcementcapacitytradechainaccess tosupportmeasuresexistence &attitude ofcompaniesaccess totechnologysecurityconsiderationsquality oftechnologyStaticgeneraleducationlevels andknowledgelack of positiveexperience withtechnologylabourcostDynamicremoteness ofoperationlevel oftraining oflabour forcecustoms&traditionsASM asprofessionor add-oncashlegalstatusmobilityof ASMASMcommunityparticipationin projectinternalorganisation &socio-economicdependenciesbenefits &losses ofmechanisationtrust in newtechnologyknowledgeon parametersof miningoperationInternalFigure 2 The factors grouped according to sphere of influence and level of dynamic11

4 Socio-economiC andenvironmental iMPactsof <strong>Mechanisation</strong>Just as social, economic and environmental issuescan determine the feasibility of mechanisation, somechanisation has impacts on these dimensions.These can work with or against the objectivethat mechanisation contributes to developmentthrough formalisation of artisanal diamond mining.The section thus considers the socio-economic andenvironmental impacts of mechanisation.Socio-economic impactsEnvironmental impactsPositive impactsFor miners• Improvement in the working conditions of people involved in mining(including women).• Minimisation of child labour in mining due to higher skilled labour.• Decrease in mining-related accidents due to better mine planningand the substitution of underground mining through open castoperations.• Greatly increased technical skills among young communitymembers.• Diversification and improvement of livelihood strategies• Increased human capital among artisanal miners is generatedthrough training programmes and new equipment.• <strong>Mechanisation</strong> can have a positive effect on OSH.• For mining communities• Sustainable increase in the income of rural community members..• Improvement in the provision of public facilities and servicesin participating communities (including education, health, power,local roads).• Decrease in intra and inter community tensions and conflictthrough strengthened mechanisms of dialogue, negotiation andconsensus-building within participating communities, wheremechanisation programmes attempt an integrated approach.• Increased social capital in participating communitiesas a consequence of all the above.• Reducing the long term footprint of mining:• Higher recovery of the deposit.• This improves the case for reclamation and rehabilitation, andwhere rehabilitation happens, provides the community with land thatcan be useful and productive through other social or economic uses,rather than a hazard.• Making reclamation easier.• Introduction of environmental management systems.4. Final hand-picking of diamondsdone by women, GhanaAdverse impactsFor miners• Increased seriousness of accidents where machines are not properlyused or maintained.• Risk of loosing machinery and collaterals from credits in the case ofhaving lower revenues than expected with the mechanised operation.• Loss of jobs due to the replacement of muscular withmechanical power.• Masculinisation of the workforce and marginalisation of women.• Increased conflict with local communities and authorities i.e. overthe environmental impacts of mechanised mining• Increased environmental impact unless the mechanisationis accompanied by sensitisation measures.• Greater areas of land can be exploited in a set time-frame.• Increased use of fuel increases the risk and likelihood of fuel spillage,leakage and pollution, and increases air pollution.• Lack of options for disposing broken or worn-out equipment(littering the landscape, creating a hazard for people and animals).• Higher rates of production mean greater volumes of waste materials• Increased downstream turbidity of rivers esp. in the case ofhydraulicking (monitoring), of dredges as well as the use oflarger washing plants12

14◆◆When making technological changes itis imperative to execute in situ inductionsessions guided by well-trained technicians,mechanics and engineers.◆◆Dissemination of the results of successfultechnological changes is the most effectivemeans for pilot operations to be replicated.◆◆Miners must pay for their project: “It cost me,I use it and I take care of it.”5.2 Access to FinanceAccess to finance is a common struggle for artisanalminers, and especially in diamond mining wherethe level of production is less predictable than,say, for gold. Generally, commercial banks are notinterested in artisanal miners as clients becausethe amount of money in question is normally toosmall to justify the administrative costs, and ASMtend to lack any collateral 12 . Furthermore, bankstend not to have sufficient expertise in ASM sothey are not able to successfully assess the risksand potential rewards.Alternative sources of finance for the mechanisationof artisanal mines include: small and mediumscalecompanies, machine owners and equipmentsellers, and local diamond buyers and ‘investors’.The latter are often a source of finance for artisanalminers, however, borrowing from them oftencarries the risk of the miner becoming financiallydependent, and the mechanisation being limitedbecause the financiers keep large parts of theprofits on the basis of the risks involved.Small and medium size investment by ASM/MSMcooperation proved feasible in case studies fromDRC and Guyana.In cases where ASM activities are pre-financed byprivate individuals such as dealers, brokers or other12However, in Guyana, in the wake of the high gold price, banks are“waking up” and more willing to extend loans to small- and mediumscaleminers (see Country study Guyana).financiers, as is common in Guinea, Sierra Leone,DRC and more recently in Ghana, mechanisationoften relies on the miner’s ability to convince thefinancier of the positive impact of this type ofinvestment on production. The relative influenceof the miner depends on whether s/he is viewed bythe financier as a borrower or a business partner.Moreover, where financiers simply view the minesas a mere investment with no other interest in orknowledge of the process, it is much harder for theminer to make the case for mechanisation.In a different system, which is typical for Brazil,a percentage of the final production is promisedto owners of respective equipment for mechanicalor technical services. A “backer” (financer) paysthe miner a minimum wage and in return receives50% of the miner’s production. In the same way,the miner can pay for services he needs (pumpingwater or digging out ore) by giving the owner ofthe equipment a percentage of his production.This way, mechanisation is possible withouthaving large amounts of upfront capital; it alsospreads the risk amongst a number of participants.The system obviously only works if productionis honestly declared (reasonable level of socialcohesion and trust).Other financial options in Guyana include:◆◆direct ownership supported by credit schemesfor the purchase of equipment by miners,◆◆cooperation between fellow miners.◆◆While research in this area is somewhatlimited, it appears that payback periods tend tobe long and at extremely high rates of interest,which also disincentivises miners from thelong term investments necessary for successfulmechanisation. Despite this, there have beenexamples of mutual funding whereby theinvestor also makes a considerable financialcontribution. 13 Another key issue is the loanguarantee which is difficult for artisanal13e.g.. for primary gemstone pegmatite miners in rural communities ofMadagascar, ATPEM project

the high amounts of finance needed and the highrisk of failure make this approach less attractive ifnot substantial investment is made in ensuring theconditions for success pre-exist.In contrast to the “fast track” approach tomechanisation, Nick Hunter 15 distinguishes the“slow build” approach, working from the basis thattime and money are directly related. For example,a lack of funds slows development down. Yet, theevidence Hunter presents suggests that even withrestricted funds artisanal miners can mechanisevery successfully – and perhaps more successfully- in the slow lane. If artisanal miners mechaniseon a step-by-step basis, they can capitalise ontheir gradually increasing returns more effectivelyby re-investing their proceeds into continualtechnical and mechanical improvements. Errorsmade along the way are low-cost and can thuscontribute to a gradual learning process instead ofjeopardising the whole process. In contrast to “fasttrack” mechanisation the “slow build” approachcan therefore produce more sustainable results,based on a gradual process of trial and error whichmeans miners can afford to make low-cost errors.It also facilitates deeper learning about morecomplex mining with regard to the operation ofthe new equipment, and, moreover, improvementsin understanding and managing business finance,markets, buying and selling, costing and pricing,budgeting and planning, maintenance, security15Hunter, 1993.and safety etc. These important soft-skills do notcome hand-in-hand with up-front investment(though they are pre-requisites for success), andare generated from operational experience.Should this approach be taken, mechanisationwould start with one aspect of the miningsequence (e.g. concentration), and then extendstep-by-step to the mechanisation of other stagesof production with a new step only being takenonce the previous step has been completed andrepaid. This is the optimal strategy for ensuringsuccessful mechanisation.5.4 The Potential for LocalManufactureSuccessful mechanisation depends on theproximity of supply, manufacture, maintenance,service and repair as well as spare part supplyfor the equipment used. The country studiesunderline that in those countries where a certaintechnology is widespread there is an establishedlocal manufacture for these tools. Studiesunderline that the technical barriers for local orregional manufacture of mechanical tools arelow 16 . High tech, such as hydraulic, electronicand power tools will generally be sourced frominternational companies.16See Priester et al. Tools for <strong>Mining</strong>, GTZ, 1994Equipment for local manufactureEquipment to be importedPre-mechNon-motorised mechPost-mechScreen/sieve, shovel/spade, bag, bucket, rope, winch,macheteHand jig, rockerGravel pump, suction dredge, dredge with airlift, trommel,jigs, feed hopper, sorting table, wheelbarrowGenerator, water pump (motor or electrical), backhoe, 4X4 truck, caterpillar, excavator, front end/back end loadersTable 2 – Site of Manufacture for different types of Equipment used in16

6.3.2 – Guidance on best practice in AADMRegardless of the nature of the pilot projector promotional measures for artisanal alluvialdiamond mining, it is highly advisable to base thisupon a concept of best practice. <strong>Mechanisation</strong>will change the mining processes applied andwill lead to new risks related to the environment,compliance with national legal and fiscalrequirements, occupational health & safety, andsocial well-being. Therefore, it is indispensableto have miners, officials, and other relevantstakeholders mutually agree on a clear conceptof responsible mining, integrating environmental,social and economic principles. Both, governmentalagencies as well as ASM operators, shouldcommit themselves to this voluntary code aimedat responsible mining practices and sustainabledevelopment. These voluntary codes are animportant element complementing the existingbinding legal framework.6.3.3 – Develop further understanding ofbarriers and success factors for formalisationGiven the importance of formalisation for the KPmember countries as well as for the mechanisationof AADM further research into barriers and successfactors for formalisation would be prudent to ensurethat mechanisation would indeed be the optimalavenue for achieving this other goal. In a firststep, it would be highly valuable to systematicallyassess the situation in other countries.6.3.4 – Support formalisation of AADM byintegrating the sector in the EITI processIn DRC, Ghana and Sierra Leone attempts aremade to achieve certification under the ExtractiveIndustries Transparency Initiative (EITI), whichgenerally focuses on the formal mining sector.Nevertheless, an inclusion of the artisanal sectorcan contribute to an optimised dialogue betweenthe key stakeholders, thereby enhancing theenvironment for formalisation.6.4 Proposals for pilot projectsIn order to support the mechanisation of AADMwithin the KP member countries pilot measuresare desirable. Given the informality of the AADMsector, it is highly recommended that if programmesare to engage these informal actors, the proposedassistance should be given in a legally shelteredarea. This means the governments would be part ofthe pilot project agreements and would guaranteethat the pilot projects operate under a specialregime on the understanding that they are beingused to generate experiences for more successfulsector development.6.4.1 – Locally improve and adapt existingtechnologies for diamond concentrationAs a consequence of the analysis of barriers andsuccess factors for the technology transfer partof a pilot project, the techniques to be appliedshould not be selected only for their technicalmerits. Specifically, the socio-economic and socioculturalbackgrounds of the miners, and the localand regional infrastructure of the zone, shouldbe integrated into the planning. This particularlyincludes the possibilities of local equipmentmanufacture. The majority of the equipmentrequired for alluvial diamond gravel concentrationshould and can be produced in national, regionaland local factories. The focus shall rather be onoptimising a known technique and improve itsoperation than to introduce a new one. Especiallyfor the African AADM countries the developmentand dissemination of an appropriate packageof trommel, jig, pumps and energy generatingsystem is required, as well as the development ofsimple dredges in combination with concentrationequipment. Locally manufactured tools fromGuyana could serve as masters for adaptation andlocal manufacture in the African target countries.18

6.4.2 – Support to suppliers of locallymanufactured equipmentInstead of supporting the mining sector directly,an alternative or complementary approach is tosupport the local equipment manufacturing andsupply industry. Developing and upgrading localmanufacturing industries so that they are best ableto produce appropriate tools and equipment can domuch to encourage local mechanisation. Specificactions include the provision of design mastersof machinery for local adaptation, organisation offield tests, training for metal mechanics, qualitycontrol and promotion campaigns. This should bedone with existing local or regional workshops.This approach uses the own interest of thecompanies to sell the product as a driving forcefor dissemination. Excellent experiences have alsobeen made with the cooperation with technicalcolleges.6.4.3 – Experiment with targetedmechanisation servicesOne country case study clearly indicates that hiringmechanised equipment becomes more expensivethe closer one gets to the final product (diamonds).This suggests that in that country especially, anintervention aimed at mechanisation through selfownedequipment should tackle the processingstage first as the equipment for the other stagesof the mining sequence can be hired more easily.It is recommended to implement a pilotproject supporting artisanal miners to combinemechanisation with own processing equipmentby means of contracting commercial services toremove the overburden. This requires backing upthe pilot project with advisory services (technicaland operational planning, environmentalconsiderations), management support (financialplanning, tendering, contracting, monitoring andquality control), empowerment of the AADMorganisation and skills development.6.4.4 – Support cooperation and cohabitationof ASM with LSM/MSM enterprisesA large number of barriers can be overcomeby promoting mechanisation of ASM throughcooperation between artisanal miners and mediumtolarge-scale mining companies. Inspiration canbe taken from a number of examples from bothwithin the diamond sector (e.g. from the casestudies from Guyana and DRC, from the MwaduiCommunity <strong>Diamond</strong> Partnership in Tanzania)and outside of it (e.g. Gold Fields “Live and LetLive” project in Ghana). Each project would haveto be individually evaluated, but in general, themost efficient cooperation can be achieved whenthe larger, legal companies provide equipmentand personnel for washing and concentrating thediamond bearing gravels and the artisanal minersconcentrate on digging. The mining companywould have the right to buy the stones producedby their equipment and mined in their concession.It would be the task of the pilot project to provideappropriate master contracts between the miningpartners based on existing best practice experiences.All involved parties have to play a role in this setup:the government and local authorities, the legalmedium/large scale mining company, the ASMand the traditional authorities. The pilot projectshould promote an attitude towards successfulcooperation and provide the required assistance. Ifeach of them adapts to a new way of doing things,win-win-projects can be created as well as newfunding and support models, capacity building, andimproved understanding between the large scale,legal operations and the ASM. The experiences ofthe pilot project should be disseminated as bestpractice examples.19

7 FinAL ThouGHTSThere are examples from around the world whereartisanal miners have brought themselves from themost basic of operations to running proper smalloreven medium-scale mines in their countriesof origin. These examples, however, are rare.Countries rarely create an enabling environmentfor artisanal miners and, instead of nurturingtheir indigenous sector through targeted effortsto professionalise their artisanal miners intoproper corporate miners, they prefer to ratherfacilitate investment and mine development byforeign actors. This may be cheaper and easier,and bringing more immediate gains, especiallyfor the state. But emphasising a nation’s artisanalsector can bring more sustainable developmentand larger gains in the longer-term for the peopleand eventually the state (Tibbett 2009). Helpingartisanal miners mechanise their operations aspart of an integrated approach to formalisationcould help create a culture of professionalisation,which would nurture more sustainable localand national development. As this study hasshown, mechanisation (or formalisation) alone,however, cannot achieve these development gains.An integrated approach is required, incorporatinginvestment in the addressing of other barriers todevelopment in ASM.5. Front hoe extracting the gravelsand at the bottom of a trench, GhanaAlthough facilitating investmentand mine development by foreignactors may be cheaper, easier andbrings more immediate gains forthe state, advancing the nation’sartisanal sector can bring moresustainable development and largegains in the longer-term for thepeople, and eventually the state.20

BIBLIOGRAPHY1. Blore, Shawn, 2006. Triple Jeopardy: Triplicate Forms and Triple Borders:Controlling <strong>Diamond</strong> Exports from Guyana, PAC occ. Paper # 14, 2006.2. Blore, Shawn, 2007, ‘Land Grabbing and Land Reform: <strong>Diamond</strong>s, Rubberand Forests in the New Liberia’, The diamonds and Human Security Project,Partnership Africa Canada, Occasional Paper # 17.3. Blore, Shawn, 2008, ‘The misery and the mark-up: Miners‘ wages anddiamond value chains in Africa and South america‘, in: Koen Vlassenrootand Steven Van Bockstael (Eds.), 2008, <strong>Artisanal</strong> diamond mining.Perspectives and challenges. Egmont. Gent: Academia Press. 66‐92.4. DDI International, 2008, ‘Standards &Guidelines for Sierra Leone’s <strong>Artisanal</strong><strong>Diamond</strong> Sector’.5. D’Souza, Kevin, 2007, ‘Briefing Note: <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Mining</strong> in the DemocraticRepublic of Congo’, CASM, DFID, WB.6. <strong>Diamond</strong>s and Human Security ANNUAL REVIEW, 2009, PAC,ISBN: 1-897320‐11‐6, http://www.pdfdownload.org/pdf2html/view_online.php?url=http://www.pacweb.org%2FDocuments%2Fannual-reviewsdiamonds%2FAR_diamonds_2009_eng.pdf7. Eisenstein, Alisha & Paul Temple (2008) Sierra Leone Integrated <strong>Diamond</strong>Management Program: Final Program Report, April 2008. MSIA:Washington, D.C.8. FESS (2007a) Consultative Workshop on Land Reclamation and AlternativeUse, Sierra Leone. Tongo Fields, Kenema District. February 2007.Washington D.C.: FESS.9. FESS (2007b) Consultative Workshop on Land Reclamation andAlternative Use, Sierra Leone. Koidu, Kono District. February 2007.Washington D.C.: FESS.10. FESS (2007c) Reclaiming the Land After <strong>Mining</strong>: Improving EnvironmentalManagement and Mitigating Land-Use Conflicts in <strong>Alluvial</strong> <strong>Diamond</strong> Fieldsin Sierra Leone. July, 2007. Washington D.C.: FESS.11. Global Witness, Partnership Africa Canada, 2004, ‘Rich Man, Poor Man.Development <strong>Diamond</strong>s and Poverty <strong>Diamond</strong>s: The Potential for Change inthe <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Alluvial</strong> <strong>Diamond</strong> Fields of Africa.12. Government of Tanzania, De Beers and Petra <strong>Diamond</strong>s (2008). MediaRelease, 9th September 2008.13. Hayes, Karen and Veerle van Wauwe (2009) “Microfinance in <strong>Artisanal</strong>and Small-scale <strong>Mining</strong>” inc CASM 2009 Mozambique: BackgroundPapers, presented at the 9th Annual CASM Conference at http://www.artisanalmining.org/userfiles/file/9th%20ACC/background_papers.pdf.14. Hentschel, Thomas, Hruschka, Felix, & Michael Priester (2003).<strong>Artisanal</strong> and Small Scale <strong>Mining</strong>: Challenges and Opportunities. London:IIED & WBCSD.15. Hunter, Nick† (1993) ‘Small/medium-scale mining as a business: slow buildor fast track?’ Presentation at the United Nations International Seminaron Guidelines for the Development of Small/Medium-Scale <strong>Mining</strong>, 1993,Harare, Zimbabwe.16. Levin, Estelle (2005) From Poverty and War to Prosperity and Peace?Sustainable Livelihoods and Innovation in Governance of <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Diamond</strong><strong>Mining</strong> in Kono District, Sierra Leone. University of British Columbia,Vancouver.17. Levin, Estelle (2006) “Reflections on the Political Economy of <strong>Artisanal</strong><strong>Diamond</strong> <strong>Mining</strong> in Sierra Leone” in Gavin Hilson (editor) Small Scale<strong>Mining</strong>, Rural Subsistence, and Poverty in West Africa. Experiences fromthe Small-scale <strong>Mining</strong> Sector. Intermediate Technology DevelopmentGroup Publishing.18. Levin, Estelle (2008) Scoping Study for Fairtrade <strong>Artisanal</strong> Gold:Tanzania.20th February 2008 Unpublished report. Medellin: Associationfor Responsible <strong>Mining</strong>.19. Levin, Estelle, Mitchell, Harrison, and Magnus Macfarlane (2008) FeasibilityStudy for the Development of a Fair Trade <strong>Diamond</strong> Standard andCertification System. Unpublished report. Transfair USA.20. Partnership Africa Canada, 2006, ‘ Triple Jeopardy. Triplicate Forms andTriple Borders: Controlling <strong>Diamond</strong> Exports from Guyana’, The diamondsand Human Security Project, Partnership Africa Canada, OccasionalPaper #14.21. Priester, Michael, Wiemer, Hans-Jürgen. 1992. Kleinbergbauberatung in derZentralafrikanischen Republik Mission report to GTZ, unpublished22. Priester, Michael/Hentschel, Thomas/Benthin, Bernd: Tools for <strong>Mining</strong>.Techniques and Processes for Small Scale <strong>Mining</strong>. Vieweg-VerlagBraunschweig 1993, ISBN 3-528-02077-623. Priester, Michael, 2005, ‘Small-Scale <strong>Mining</strong> Assistance in DevelopingCountries. Evaluation of general Development Policy Focus and the CoreElements for its Successful Implementation’, CASM.24. Temple, P. (2009) “<strong>Diamond</strong> Sector Reform in Sierra Leone : A programperspective” in <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Diamond</strong> <strong>Mining</strong>: Perspectives and Challenges,edited by Koen Vlassenroot & Steven Van Bockstael. Gent: Egmont.25. Tibbett, Steve (2009) A Golden Opportunity: Recasting the Debate on theEconomic and Development Benefits of Small-scale and <strong>Artisanal</strong> Gold<strong>Mining</strong>. December 2009. UK: CRED Foundation.26. USAID, PROPERTY RIGHTS AND ARTISANAL DIAMOND DEVELOPMENT(PRADD) PILOT PROJECT, project leaflet27. Vlassenroot, Koen and Steven van Bockstael (Eds.), 2008, <strong>Artisanal</strong>diamond mining. Perspectives and challenges. Egmont. Gent:academia Press.28. Wetzenstein, Wolfgang, 2005, „Wirkungsanalyse von Maßnahmenim Bereich Bergbau: Wirkungen des Bergbaus in Entwicklungs- undSchwellenländern; Ausgewählte Projektbeispiele von BGR-TZ-Aktivitätenim Bergbausektor“29. Wotruba, Hermann, Thomas Hentschel, Karen Livan, Felix Hruschka andMichael Priester (2005), Environmental Management in Small-Scale<strong>Mining</strong>. MEDMIN, CASM, COSUDE.21

© DDI International, 2010 – <strong>Mechanisation</strong> of <strong>Alluvial</strong> <strong>Artisanal</strong> <strong>Diamond</strong> <strong>Mining</strong>: Barriers and Success Factors