PDF for Printing - Graduate School of Arts and Sciences - Columbia ...

PDF for Printing - Graduate School of Arts and Sciences - Columbia ...

PDF for Printing - Graduate School of Arts and Sciences - Columbia ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

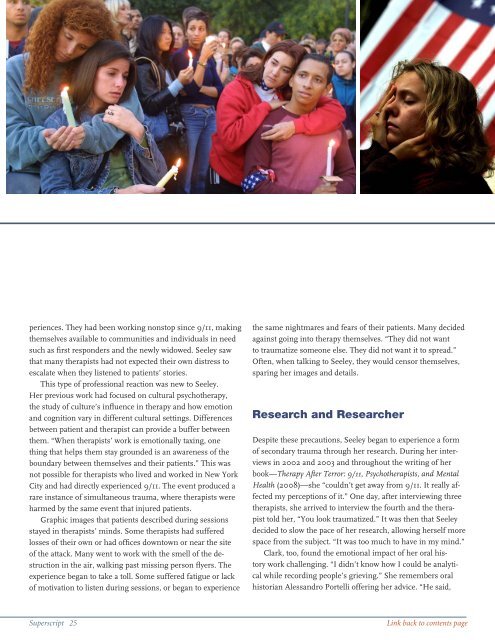

periences. They had been working nonstop since 9/11, makingthemselves available to communities <strong>and</strong> individuals in needsuch as first responders <strong>and</strong> the newly widowed. Seeley sawthat many therapists had not expected their own distress toescalate when they listened to patients’ stories.This type <strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional reaction was new to Seeley.Her previous work had focused on cultural psychotherapy,the study <strong>of</strong> culture’s influence in therapy <strong>and</strong> how emotion<strong>and</strong> cognition vary in different cultural settings. Differencesbetween patient <strong>and</strong> therapist can provide a buffer betweenthem. “When therapists’ work is emotionally taxing, onething that helps them stay grounded is an awareness <strong>of</strong> theboundary between themselves <strong>and</strong> their patients.” This wasnot possible <strong>for</strong> therapists who lived <strong>and</strong> worked in New YorkCity <strong>and</strong> had directly experienced 9/11. The event produced arare instance <strong>of</strong> simultaneous trauma, where therapists wereharmed by the same event that injured patients.Graphic images that patients described during sessionsstayed in therapists’ minds. Some therapists had sufferedlosses <strong>of</strong> their own or had <strong>of</strong>fices downtown or near the site<strong>of</strong> the attack. Many went to work with the smell <strong>of</strong> the destructionin the air, walking past missing person flyers. Theexperience began to take a toll. Some suffered fatigue or lack<strong>of</strong> motivation to listen during sessions, or began to experiencethe same nightmares <strong>and</strong> fears <strong>of</strong> their patients. Many decidedagainst going into therapy themselves. “They did not wantto traumatize someone else. They did not want it to spread.”Often, when talking to Seeley, they would censor themselves,sparing her images <strong>and</strong> details.Research <strong>and</strong> ResearcherDespite these precautions, Seeley began to experience a <strong>for</strong>m<strong>of</strong> secondary trauma through her research. During her interviewsin 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2003 <strong>and</strong> throughout the writing <strong>of</strong> herbook—Therapy After Terror: 9/11, Psychotherapists, <strong>and</strong> MentalHealth (2008)—she “couldn’t get away from 9/11. It really affectedmy perceptions <strong>of</strong> it.” One day, after interviewing threetherapists, she arrived to interview the fourth <strong>and</strong> the therapisttold her, “You look traumatized.” It was then that Seeleydecided to slow the pace <strong>of</strong> her research, allowing herself morespace from the subject. “It was too much to have in my mind.”Clark, too, found the emotional impact <strong>of</strong> her oral historywork challenging. “I didn’t know how I could be analyticalwhile recording people’s grieving.” She remembers oralhistorian Aless<strong>and</strong>ro Portelli <strong>of</strong>fering her advice. “He said,Superscript 25Link back to contents page