Education in Emergencies: The Gender Implications - INEE

Education in Emergencies: The Gender Implications - INEE

Education in Emergencies: The Gender Implications - INEE

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

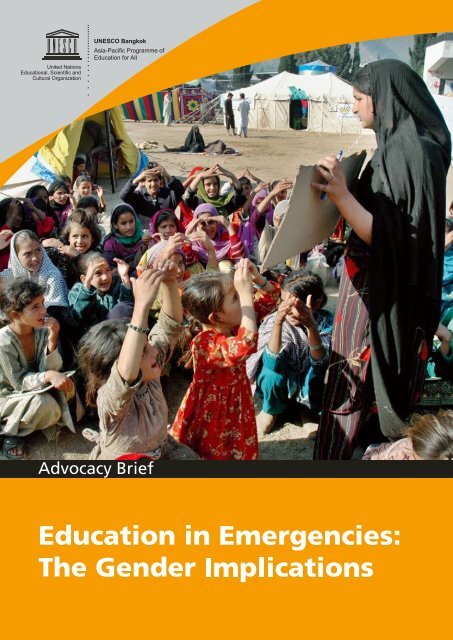

<strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong> - Advocacy Brief.Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok, 2006.12 pp.1. <strong>Education</strong> policy. 2. Natural disasters. 3. Manmade disasters.4. <strong>Gender</strong> roles.ISBN 92-9223-092-1Photo credit: © UNICEF/PAKA01495D/Zaidi© UNESCO 2006Published by theUNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for <strong>Education</strong>920 Sukhumvit Road, PrakanongBangkok 10110, ThailandPr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> Thailand<strong>The</strong> designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the publication do not imply theexpression of any op<strong>in</strong>ion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concern<strong>in</strong>g the legal status of any country,territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>g its frontiers or boundaries.APL/06/ROS/127-250

Advocacy Brief<strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>:<strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>

C o n t e n t sAcknowledgementsiiiIntroduction to <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> 1<strong>Gender</strong> and <strong>Emergencies</strong> 2Emergency Situations: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> 3<strong>Gender</strong>, <strong>Education</strong> and Protection <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> 6General Policy and Programme Development Guidel<strong>in</strong>es, Strategies andApproaches 7Specific Programme Strategies 8Conclusions 10Bibliography/Resource List 11

AcknowledgementsThis advocacy brief, prepared for UNESCO Bangkok by Jackie Kirk, has benefited fromthe review and comments of the Advisory Committee for Advocacy and Policy Briefs. <strong>The</strong>Committee consists of the follow<strong>in</strong>g experts: Sheldon Shaeffer, Lydia Ruprecht, FlorenceMigeon, and Shirley Miske. In addition, valuable <strong>in</strong>puts were received from Hoa PhuongTran, Regional <strong>Education</strong> Advisor, Plan International and Silje Skeie, Associate Expert,UNESCO Bangkok.© UNICEF/J. Esteyiii

© UNICEF/J. Estey

Introduction to <strong>Education</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>‘<strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> emergencies’ refers to a broad range of educational activities – formal andnon-formal – which are life-sav<strong>in</strong>g and life-susta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and, therefore, critical for children,youth and their families <strong>in</strong> times of crisis. Crisis situations <strong>in</strong>clude natural disasters such asearthquakes, tsunamis and floods, as well as man-made conflicts. Emergency educationprogrammes are designed accord<strong>in</strong>g to the particular context of the environment andmay be short-term, temporary solutions such as ‘tent schools’ for when school build<strong>in</strong>gsare destroyed, damaged or <strong>in</strong>accessible. However, education <strong>in</strong> emergencies also refersto longer-term education policy and programme development <strong>in</strong> chronic crisis situations.<strong>The</strong>se <strong>in</strong>clude situations where refugees and <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced persons (IDPs) are uprootedfor many years and have long-term education needs, or where the state is chronically‘fragile’ and unable or unwill<strong>in</strong>g to provide quality education services for the population. Inaddition, education <strong>in</strong> emergencies covers education activities <strong>in</strong> post-emergency recovery,reconstruction and peace-build<strong>in</strong>g periods. <strong>Education</strong> activities evolve over time andgenerally span different phases of the crisis – acute emergency, recovery and reconstruction.Even short-term, improvised education <strong>in</strong>terventions should be planned with an awarenessof the longer-term education needs of the community and of the vision and policies ofrelevant authorities.No clear divid<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>e exists between ‘emergency’ and ‘regular’ education, especially <strong>in</strong>chronic crisis and reconstruction contexts, and much accepted ‘good practice’ appliesequally across both. However, education <strong>in</strong> emergencies does have particular features. Overrecent years, awareness of the importance of education <strong>in</strong> emergencies has grown, andeducation is now <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational disaster relief fund<strong>in</strong>g appeals alongside other‘traditional’ humanitarian sectors such as water and sanitation, health and shelter. <strong>Education</strong>programmes are then supported by <strong>in</strong>ternational and national NGOs and UN agencies. Thisis particularly necessary when the state education system is not fully function<strong>in</strong>g. Whereteachers have been killed, <strong>in</strong>jured, have fled, or are otherwise occupied with fight<strong>in</strong>g orwith their own survival and that of their families, ‘emergency teachers’ may need to berecruited from with<strong>in</strong> the local population. Condensed, rapid tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programmes for new,<strong>in</strong>experienced teachers are a common feature of emergency education programmes. <strong>The</strong>programme content has to be adapted accord<strong>in</strong>g to specific, local needs, but the protectionand promotion of students’ psychosocial well-be<strong>in</strong>g underp<strong>in</strong>s most <strong>in</strong>terventions. In timesof crisis, the restoration of formal and non-formal education programmes as early as possibleis a significant step towards restor<strong>in</strong>g normalcy and provid<strong>in</strong>g reassur<strong>in</strong>g rout<strong>in</strong>e, cont<strong>in</strong>uityand hope for the future of both the children and their communities.Quality, relevant education is a right of all children. Children <strong>in</strong> crisis situations often neednew and different knowledge, skills and learn<strong>in</strong>g experiences <strong>in</strong> order to survive and tothrive <strong>in</strong> changed circumstances. <strong>The</strong>y are particularly vulnerable, fac<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creased risks ofphysical and emotional harm. <strong>Education</strong> content to counter these risks may <strong>in</strong>clude, forexample, land m<strong>in</strong>e education, health and nutrition education, and other life skills suchas HIV/AIDS prevention. Refugees or <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced children may need to learn <strong>in</strong>Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>Psychosocial well-be<strong>in</strong>g refers to the close connection between psychological aspects of experience (thoughts, emotionsand behaviour) and wider social experiences (relationships, traditions and culture). It is broader than concepts such as‘mental health’, which run the risk of ignor<strong>in</strong>g aspects of the social context, and ensures that the importance of familyand community are recognized (PSWG, 2003).

Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>a different language than that of the local, host population and to follow a curriculumthat will allow them to transfer back <strong>in</strong>to the education system when they return home.However, for children and youth displaced over a long period, learn<strong>in</strong>g the language ofthe host community may be important for ensur<strong>in</strong>g future <strong>in</strong>come-generat<strong>in</strong>g possibilities,as well as for build<strong>in</strong>g bridges between communities. Emergency education programmesoften conta<strong>in</strong> elements of disaster prevention, preparedness and mitigation, such as lessonsfor students about how to protect themselves <strong>in</strong> the event of an earthquake or what todo if rebel forces come to their village. In conflict-affected contexts, the <strong>in</strong>clusion of peaceeducation and conflict resolution <strong>in</strong> education programmes for children and youth shouldsupport peace processes at different levels and contribute towards more peaceful futures. Inthis respect, careful attention to revis<strong>in</strong>g traditional curriculum content is required, especially<strong>in</strong> potentially-sensitive subjects such as history and social science. This is particularly the casewhen notions of ethnic, religious or geographical superiority have been emphasized with<strong>in</strong>the curriculum and may actually fuel tensions or conflict between different groups with<strong>in</strong>the population.A number of <strong>in</strong>ternational policy developments have helped to shape an evolv<strong>in</strong>g field ofpractice known as ‘education <strong>in</strong> emergencies’, which is now <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to educationpolicy frameworks of relevant UN agencies (primarily UNICEF, UNHCR and UNESCO) andmultilateral and bilateral donors. <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> emergencies is also ga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ground as a newfield for study and research. Graça Machel’s 1996 report to the UN on children affected byconflict and the follow-up report of 2000 were significant <strong>in</strong> rais<strong>in</strong>g awareness of the extentto which children suffer <strong>in</strong> times of war. <strong>The</strong>se reports also highlighted the importance ofeducation and the fact that many children affected by conflict – most notably girls – do nothave access to school<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> World <strong>Education</strong> Forum, held <strong>in</strong> Dakar, Senegal <strong>in</strong> April 2000,also recognized that the <strong>Education</strong> for All (EFA) targets will not be met unless educationsystems <strong>in</strong> conflict-and disaster-affected contexts are given specific attention. ‘Fragile states’– many of which are crisis or post-conflict states – are now a focus for policy developmentof donors and UN and other agencies. Aware that reach<strong>in</strong>g the Millennium DevelopmentGoals – especially those relat<strong>in</strong>g to education – <strong>in</strong> fragile states is highly challeng<strong>in</strong>g, donorsare develop<strong>in</strong>g policy guidel<strong>in</strong>es for alternative forms and approaches to service delivery <strong>in</strong>such countries.<strong>Gender</strong> and<strong>Emergencies</strong><strong>The</strong>re is now <strong>in</strong>creased awareness of how emergencies such as conflict and natural disastersare experienced differently by men and women, boys and girls. <strong>The</strong> different roles, activities,skills, positions and status of men and women <strong>in</strong> families, communities and <strong>in</strong>stitutionscreate gender-differentiated risks, vulnerabilities and capacities <strong>in</strong> an emergency situation.For example, many more women than men died <strong>in</strong> the 2004 South Asian tsunami because See Machel, 1996, 2000 MDG 2: Achieve universal primary education. (Target 3: Ensure that, by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, willbe able to complete a full course of primary school<strong>in</strong>g.)MDG 3: Promote gender equality and empower women. (Target 4: Elim<strong>in</strong>ate gender disparity <strong>in</strong> primary and secondaryeducation, preferably by 2005, and at all levels of education no later than 2015.)

women were more likely to be at home at the time – or <strong>in</strong> the case of a community <strong>in</strong>Sri Lanka, tak<strong>in</strong>g their baths <strong>in</strong> the sea, close to the shore. In many locations, men werefurther out to sea and so were safer. Women were also physically less able to run from theenormous waves and to climb trees. In conflict situations, men and young boys may beat greater risk of recruitment <strong>in</strong>to fight<strong>in</strong>g forces and <strong>in</strong>to potentially-lethal active combat,but women and girls may be forced to serve as sex slaves and cooks, or to take on othernon-combatant roles. <strong>The</strong>y may be targeted for rape and sexual abuse by fight<strong>in</strong>g forces,but may also be subjected to sexual violence by the men of their own community andfamily. Levels of sexual violence and exploitation of women and girls can also <strong>in</strong>crease whennatural disasters strike, as well as <strong>in</strong> the aftermath if displaced families are crowded <strong>in</strong>topoorly-designed camps with few protective features such as good light<strong>in</strong>g and separatetoilet/wash<strong>in</strong>g facilities for females. Unfortunately, the desire to protect women and girlsfrom such risks can also mean that they are prevented from access<strong>in</strong>g education, health andother critical support services.At the same time, emergency situations and the priority to survive mean that both men andwomen often have to take on non-traditional gender roles and activities. In the aftermathof the South Asian earthquake of October 2005, for example, widowed men were cook<strong>in</strong>gfood for their children for the first time <strong>in</strong> their lives. In some circumstances, women affectedby a crisis may also benefit from the ‘w<strong>in</strong>dow of opportunity’ to access new opportunities– for example, to go out to work and control family f<strong>in</strong>ances for the first time. However,these shifts may not be susta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the long term and women may end up carry<strong>in</strong>g adouble burden – that is, cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to do both their traditional activities such as householdchores and childcare and additional tasks that would otherwise be carried out by men. Insome emergency situations, especially conflicts <strong>in</strong> which ethnicity and cultural identity arethreatened, traditional gender differences and patterns of activity become even more rigidlyadhered to, and women and girls are subjected to <strong>in</strong>creased limitations on mobility andparticipation.Emergency Situations:<strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong>Machel’s reports highlighted the disproportionate impact of conflict on girls and, <strong>in</strong>particular, on girls’ access to education. Subsequent studies, reports, programmes and policy<strong>in</strong>terventions have raised awareness of the gender dimensions of emergency situations andof the critical need to ensure that both girls and boys have early and equal access to, andbenefit equally from, relevant education (see bibliography). Although there are exceptions,<strong>in</strong> most emergency situations, girls’ educational opportunities are more limited than boys’.Even under very difficult conditions, however, ‘w<strong>in</strong>dows of opportunity’ may also open up forgirls and women to access education. It is critical to establish gender-responsive emergencyeducation programmes early on as these lay the foundations for <strong>in</strong>creased participation ofwomen and girls <strong>in</strong> recovery/reconstruction activities, as well as <strong>in</strong> community and nationaldevelopment processes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, for example, stand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> newly-democratic elections. Ifwomen and girls are not equally <strong>in</strong>cluded from the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g, then it can be very difficult toencourage them <strong>in</strong>to the system later because of the tendency for emergency arrangementsto set patterns for the future.Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong> See, for example, Oxfam International (2005)

Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>Factors that limit girls’ educational opportunities <strong>in</strong> stable contexts often <strong>in</strong>tensify <strong>in</strong> crises.For example, there may be even greater preference given to sons when family resourcesare limited by collapsed markets and reduced access to <strong>in</strong>come. Boys’ school attendance isprioritized <strong>in</strong> many stable countries, but this can become even more pronounced <strong>in</strong> times ofcrisis when there is usually less money available to pay fees and buy uniforms or supplies.At the same time, emergency situations create particular disadvantages for girls, such asthe often extremely unbalanced demographics with large numbers of women-headedhouseholds. When these women have to take up work outside the home, older daughterscare for sibl<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>in</strong>crease their household chores and, as a result, stay home from school.Sexual violence also affects girls and boys <strong>in</strong> many so-called ‘normal’ situations, but attimes of crisis and <strong>in</strong> conflict situations, the magnitude may be greater and the impact<strong>in</strong>tensified because prevention, referral and support mechanisms collapse. <strong>The</strong> risks of HIV/AIDS and sexually-transmitted disease (STD) <strong>in</strong>fection are also heightened. Conflict createsexaggerated cultures of male dom<strong>in</strong>ation, aggressiveness, violence, and impunity. Girls andwomen <strong>in</strong>evitably suffer. In the ‘abnormal’ world of a refugee camp, sexual violence canbecome normalized. This adversely affects girls’ education <strong>in</strong> different ways. <strong>The</strong> risk ofsexual violence on the way to school, or even <strong>in</strong> and around the school, may conv<strong>in</strong>ceparents to keep their daughters at home. Increased risk is created by, for example, largenumbers of soldiers, rebels, police or even peacekeepers <strong>in</strong> the area, or by hav<strong>in</strong>g to gofurther than normal to f<strong>in</strong>d firewood, food or water. Girls who do go to school may f<strong>in</strong>dthat they are subjected to harassment, exploitation and even rape by male students orteachers, with no one to turn to for protection, response or report<strong>in</strong>g. In an emergencyeducation programme, checks and balances such as professional orientation sessions fornew teachers, codes of conduct and regular supervision for teachers may not be <strong>in</strong> place,and new ‘emergency’ teachers may have far lower levels of professionalism than ‘regular’teachers. Furthermore, large numbers of over-age male students, who are try<strong>in</strong>g to catch upon years of missed school<strong>in</strong>g, often contribute to an uncomfortable classroom environmentfor girls. This is especially true if, as is the case <strong>in</strong> most programmes, there are very fewwomen teachers.Girls drop out of school because of early marriage and pregnancy <strong>in</strong> many non-emergencycontexts, but the pressures to do so may be <strong>in</strong>creased or slightly different <strong>in</strong> emergencies.Dim<strong>in</strong>ished family resources may force families to marry off their daughters earlier thanthey normally would <strong>in</strong> order to obta<strong>in</strong> a dowry payment, for example. Families may also beforced to compromise their daughters to marry <strong>in</strong> order to w<strong>in</strong> favour – and security – fromsoldiers, rebels or others with power and <strong>in</strong>fluence.Even when both girls and boys affected by crises are able to access education, gender<strong>in</strong>equalities with respect to the quality and appropriateness of education may rema<strong>in</strong>.Particularly <strong>in</strong> emergency programmes, the teachers are usually male, and it can be verydifficult to ensure that there are women <strong>in</strong> school who can act as mentors, role models orresource persons for girls. Women teachers – if they are present <strong>in</strong> the school – may be toopreoccupied with their own concerns to provide additional support to girls. F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g otherwomen who have the time, capacity and will<strong>in</strong>gness to work <strong>in</strong> schools may also be difficult.Crash teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g courses may only cover the very basic topics of how to organize andteach a class. Furthermore, teachers more often struggle to manage with basic classroommanagement and <strong>in</strong>struction (especially with large, multi-age classes) dur<strong>in</strong>g crises and thusmay be unable to ensure that the lessons relate to girls’ experiences as well as to boys’.Teach<strong>in</strong>g materials often have to be pulled together quickly from what is available, with littleregard for any gender stereotyp<strong>in</strong>g they may conta<strong>in</strong>.

Hence, <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g the gender dimensions of emergency situations, one must exam<strong>in</strong>ethe issue from both supply and demand sides:Supply Factors• When schools are destroyed, and children have to travel long – and possibly dangerous –distances to attend the nearest function<strong>in</strong>g facility, girls are more likely to stay at home.• When schools are damaged or just not ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed and no sanitary facilities exist, girls– and especially adolescent girls – are disproportionately affected; they may have to missschool dur<strong>in</strong>g menstruation.• Boys may be at risk of abduction and forced recruitment by fight<strong>in</strong>g forces at school or ontheir way to and from school, but girls may also be at <strong>in</strong>creased risk of abduction and ofsexual violence and exploitation.• In emergencies, there are usually far fewer women who are able to volunteer as teachers,and girls are disproportionately affected when schools are dom<strong>in</strong>ated by men.Demand Factors• Where parents are unable to pay school fees and buy the necessary supplies, boys may bemore able – and it may be safer for them – to go out and engage <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>come-generat<strong>in</strong>gactivities to pay their own school fees than girls.• For refugees, IDPs and others affected by crises, the symbolic power of education as aforce for change and as a passport to a different and better life is particularly strong;children often want to go to school, whatever the costs. Girls who are desperate to attendschool and to get good grades may have to engage <strong>in</strong> transactional sex with older men– and even teachers – <strong>in</strong> order to pay their fees, cover the costs of supplies and ensuregood grades, thus expos<strong>in</strong>g them to higher risks of STD and HIV/AIDS <strong>in</strong>fection.• Children who are separated from their families and liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> temporary conditions withrelatives or foster families may lack the support and encouragement to cont<strong>in</strong>ue theireducation. This is especially the case for girls who are often expected to do householdchores and have no time to study.• Teenage pregnancy rates are often very high <strong>in</strong> refugee and IDP camps, and girls withtheir own babies may not be able to attend school because of exclusionary policies, socialstigma, no extended family to provide childcare, lack of appropriate facilities, etc.• Girls who are disabled, disfigured or severely mentally affected by the crisis are likely tobe kept at home, possibly even hidden from outsiders, and very unlikely to be able to goto school.It is also important to po<strong>in</strong>t out that <strong>in</strong> emergency situations, such gender <strong>in</strong>equalities existat a time when the political will, resources, and expertise to address these issues are usuallyleast available. Often, the more press<strong>in</strong>g imperative is to occupy boys and young men tokeep them from trouble, <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> gangs, violence and other anti-social behaviour.Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>

General Policy and Programme DevelopmentGuidel<strong>in</strong>es, Strategies and Approaches<strong>The</strong> Inter-Agency Network for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> (<strong>INEE</strong>) has facilitated thedevelopment of the M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>, Chronic Crisesand Early Reconstruction. <strong>The</strong> <strong>INEE</strong> Standards fill a significant gap by provid<strong>in</strong>g consensualprogramm<strong>in</strong>g guidel<strong>in</strong>es for education <strong>in</strong> emergencies. <strong>The</strong>y are a common frameworkaround which quality education <strong>in</strong>terventions can be designed, implemented, monitored andevaluated. Grounded <strong>in</strong> the Dakar Framework for Action, <strong>Education</strong> for All commitments,the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of All Formsof Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Aga<strong>in</strong>st Women (CEDAW) and other <strong>in</strong>ternational and regional rights<strong>in</strong>struments, the M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards also provide a framework for promot<strong>in</strong>g genderequality, ensur<strong>in</strong>g that girls’ and boys’ rights to quality and relevant education are metand that the education provided is gender-responsive and empower<strong>in</strong>g for all. S<strong>in</strong>ce thelaunch of a handbook <strong>in</strong> December 2004, the M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards are be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>toongo<strong>in</strong>g education programmes. <strong>The</strong>y have already been used <strong>in</strong> a number of new crisissituations, most notably the natural disaster emergencies of the December 2004 tsunami,Hurricane Katr<strong>in</strong>a and the Pakistan earthquake.<strong>Gender</strong> equality is a theme that is <strong>in</strong>tegrated across all categories of the M<strong>in</strong>imumStandards. Work<strong>in</strong>g towards fully meet<strong>in</strong>g the Standards necessarily implies attention togender equality and the gender-based needs and aspirations of male and female learners,teachers and community members. Ensur<strong>in</strong>g equal access to education for girls is clearly apriority issue (Access Category, Standard 1), but the Standards convey the need for genderto be considered <strong>in</strong> all components and <strong>in</strong> all dimensions of education provision. Fromthe onset of an emergency, an <strong>in</strong>-depth gender-based analysis of the situation is required,as well as consistently gender-focused monitor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluation processes. Coord<strong>in</strong>ationamongst different actors should ensure that gender equality is a common theme, that itis embedded <strong>in</strong> education policy, and also that gaps <strong>in</strong> programm<strong>in</strong>g can be identified sothat resources are targeted to reach specific groups of marg<strong>in</strong>alized boys and girls, withprogrammes tailored to their specific needs (see M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards category: <strong>Education</strong>Policy and Coord<strong>in</strong>ation). <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> Task Team of the <strong>INEE</strong> has developed some field-leveltools for promot<strong>in</strong>g gender equality <strong>in</strong> education dur<strong>in</strong>g emergencies that complement theM<strong>in</strong>imum Standards (see www.<strong>in</strong>eesite.org/gender).6 See www.<strong>in</strong>eesite.org. <strong>The</strong> <strong>INEE</strong> was formed <strong>in</strong> 2000 and has s<strong>in</strong>ce grown to have a membership of over 100 organizationsand 800 <strong>in</strong>dividuals. Its mandate is to share knowledge and experience, to promote greater donor understand<strong>in</strong>g ofeducation <strong>in</strong> emergencies and advocate for education to be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> emergency response. It also seeks to maketeach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g resources available as widely as possible, to ensure attention to gender issues <strong>in</strong> emergencyeducation <strong>in</strong>itiatives and to document and dissem<strong>in</strong>ate best practices <strong>in</strong> the field. With<strong>in</strong> <strong>INEE</strong>, a <strong>Gender</strong> Task Team worksspecifically on ensur<strong>in</strong>g that gender concerns are <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to education dur<strong>in</strong>g emergencies.7 <strong>The</strong> Sphere standards, widely used to guide humanitarian actions <strong>in</strong> other sectors, do not <strong>in</strong>clude education.See www.sphereproject.orgAdvocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>8 Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women <strong>in</strong> Africa, notably Article 119 <strong>The</strong> categories of the M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards are: Community Participation, Analysis, Access and Learn<strong>in</strong>g Environment,Teach<strong>in</strong>g and Learn<strong>in</strong>g, Teachers and Other <strong>Education</strong> Personnel, <strong>Education</strong> Policy and Coord<strong>in</strong>ation.

Specific ProgrammeStrategiesAdvocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>Increas<strong>in</strong>g Access to <strong>Education</strong>Targeted and gender-responsive measures are required to ensure that girls and boys,particularly adolescent girls and boys, have equal access to education <strong>in</strong> emergency situations.Strategies <strong>in</strong>clude:• Locat<strong>in</strong>g schools and learn<strong>in</strong>g spaces close to the learners’ homes and away from differentk<strong>in</strong>ds of dangers, such as soldiers’ quarters and dense bush• Involv<strong>in</strong>g community members to ensure safe travel to and from school, particularly forgirls• Proactively recruit<strong>in</strong>g women teachers and provid<strong>in</strong>g support for additional professionaldevelopment activities to complete these teachers’ own education• Tim<strong>in</strong>g classes to enable girls and boys with other responsibilities to attend• Provid<strong>in</strong>g childcare facilities for women teachers and girl-mother students• Provid<strong>in</strong>g sanitary materials and facilities for girls and women teachers• Provid<strong>in</strong>g school feed<strong>in</strong>g programmes or take-home rations for girls (and for the babiesof girl mothers) 10• Engag<strong>in</strong>g girls and boys <strong>in</strong> the preparation of a ‘miss<strong>in</strong>g-out map’ – that is, a map of thechildren <strong>in</strong> the community who are currently not <strong>in</strong> school – and <strong>in</strong> the design of genderresponsiveeducation programmes to reach out-of-school children 11Ensur<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>Education</strong> is Empower<strong>in</strong>g and Protective for Girls and BoysAs highlighted earlier, attention is also required to ensure that the curriculum content andteach<strong>in</strong>g methods with<strong>in</strong> emergency education programmes provide physical, cognitive andpsychosocial protection for girls and boys. With <strong>in</strong>put from the community, curricula shouldbe designed with this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, and special topics may need to be developed to addressspecific risks. Quality teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g and ongo<strong>in</strong>g professional support are critical to ensur<strong>in</strong>gthat <strong>in</strong>experienced male and female teachers are able to promote the academic, social andemotional well-be<strong>in</strong>g of students and to create safe and nurtur<strong>in</strong>g learn<strong>in</strong>g environments.Ensur<strong>in</strong>g that girls and boys have equal opportunities to ga<strong>in</strong> essential literacy, numeracyand relevant life skills <strong>in</strong> an environment <strong>in</strong> which they are considered as equals and <strong>in</strong>which their potential for equal participation <strong>in</strong> community and social development is fullyrespected is critical preparation for the future. This is so for the youth themselves, for theirfamilies and communities, and for society as a whole.10 <strong>The</strong> Sphere standards on nutrition highlight the need for mechanisms to target adolescent girls with additional nutritionalsupport (Sphere Project, 2004, p. 142).11 This exercise needs to be adapted for the country <strong>in</strong> which it is be<strong>in</strong>g carried out, and this is especially so for emergencycontexts. <strong>The</strong> focus is on problems of access to education for young children, especially girls. But <strong>in</strong> countries where thesituation is different, it can be on dropp<strong>in</strong>g out or persistent absenteeism, particularly among boys.

<strong>The</strong> table below highlights priority gender strategies across emergency educationprogrammes:Area of FocusProgrammeDesignCurriculumContentTeacherDevelopmentTeacherManagementand SupportMonitor<strong>in</strong>gand EvaluationStrategiesM<strong>in</strong>imum StandardReference• <strong>Gender</strong>-focused needs analysis is conducted at the onset of • Analysis,the crisis and regularly updated as the situation evolves Standards 1• Attention is given to assess<strong>in</strong>g the particular vulnerabilities and 3and capacities of boys and girls• Male and female youth and community members are <strong>in</strong>volved • Community<strong>in</strong> needs assessment and programme design; specific efforts Participation,may be needed to reach out to women and girlsStandard 1• Learn<strong>in</strong>g spaces are established <strong>in</strong> safe and accessible • Access andlocations for girls and boys, and adequate sanitary facilities Learn<strong>in</strong>gare providedEnvironment,Standards 1, 2, 3• Curriculum <strong>in</strong>cludes protective content for girls and boys,e.g. life skills, HIV/AIDS prevention, conflict resolution andnutrition• Textbooks and learn<strong>in</strong>g materials conta<strong>in</strong> positive messagesabout the roles and status of men and women, boys and,girls, and <strong>in</strong> particular, their complementary roles <strong>in</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g,reconstruction, nation-build<strong>in</strong>g, etc.• Teachers receive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> child-centred, genderresponsivemethodologies and <strong>in</strong> psychosocial support andprotection for children• Teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cludes sessions on teachers’ roles ascommunity leaders and agents of child protection• Teacher tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cludes positive classroom managementand behaviour management practices as alternatives tocorporal punishment• Male and female teachers are encouraged to act as rolemodels for male and female youth whose parents andelders may be unable to offer the support and advice theywould normally provide• Teachers are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g a code of conductwhich highlights exemplary conduct for child protection• Teachers are actively engaged <strong>in</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g discussions anddecision-mak<strong>in</strong>g to ensure child protection and well-be<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> and out of school• Teachers receive regular professional advice that issupportive and encourag<strong>in</strong>g• <strong>Gender</strong>-responsive psychosocial support or counsell<strong>in</strong>g isavailable for teachers• Indicators are developed to reflect gender equality, studentprotection, and well-be<strong>in</strong>g concerns• Teach<strong>in</strong>g andLearn<strong>in</strong>g,Standard 1• Teach<strong>in</strong>g andLearn<strong>in</strong>g,Standard 2• Teach<strong>in</strong>g andLearn<strong>in</strong>g,Standard 3• Teachers andOther <strong>Education</strong>Personnel,Standard 3• Analysis,Standard 3• Appropriate sex-disaggregated data is collected on aregular basis• As far as possible, male and female community members, • Communityeducation authorities, teachers and learners are <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> Participation,monitor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluationStandard 1• Monitor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluation data feed <strong>in</strong>to ongo<strong>in</strong>g • Analysis,programme review and improvement to ensure that Standard 3differentiated needs are met and capacities developedAdvocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>

ConclusionsAdvocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>10<strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> emergencies is a critical <strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> the promotion of gender equality. Itcan create opportunities for girls and women for cognitive development and <strong>in</strong>dividualempowerment that may not have existed before. Beyond this, education opportunities canhelp to improve the status of women and girls <strong>in</strong> society. Women’s and girls’ participation iscritical <strong>in</strong> post-emergency recovery, reconstruction and peace-build<strong>in</strong>g efforts and genderresponsiveeducation programmes that give girls opportunities to learn new skills and developtheir confidence help to pave the way <strong>in</strong> this process. Strategies outl<strong>in</strong>ed above can help toensure that education programmes – formal or non-formal – established by governments,UN agencies, <strong>in</strong>ternational NGOs or community-based organizations, fulfil their protectivepotential and meet the needs of all learners. <strong>The</strong> M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards represent a significantstep forward and should contribute to <strong>in</strong>creased access and enhanced quality of education.Other complementary tools, aligned with the M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards, are now be<strong>in</strong>g developedto promote gender equality and to ensure the protection of girls and boys <strong>in</strong> and througheducation. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>in</strong>clude guidel<strong>in</strong>es on gender-based violence <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>in</strong> humanitariansett<strong>in</strong>gs and on mental health and psychosocial well-be<strong>in</strong>g. 1212 See www.humanitarian<strong>in</strong>fo.org/iasc/content/products/docs/tfgender_GBVGuidel<strong>in</strong>es2005.pdf andwww.humanitarian<strong>in</strong>fo.org/iasc/mentalhealth_psychosocial_support

Bibliography/Resource ListHowgego, C. M. (2004) “<strong>Gender</strong> Imbalance <strong>in</strong> Secondary Schools” <strong>in</strong> Forced Migration Review,Vol 22, January 2005, p. 32-33. Available from http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR22/FMR2216.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Inter-Agency Network for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>. (2004) M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>Emergencies</strong>, Chronic Crises and Early Reconstruction. London: <strong>INEE</strong>.Inter-Agency Network for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>. (2006) Good Practice Guide: Girls’ and Women’s<strong>Education</strong> [onl<strong>in</strong>e]. Available from http://www.<strong>in</strong>eesite.org. Accessed 04/10/06.Inter-Agency Network for <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>, International Rescue Committee & Women’sCommission. (2006) Ensur<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>Gender</strong> Perspective <strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> [onl<strong>in</strong>e]. Availablefrom http://www.womenscommission.org/pdf/Ed<strong>Gender</strong>Tool.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Inter-Agency Stand<strong>in</strong>g Committee. (2005) IASC Guidel<strong>in</strong>es for <strong>Gender</strong>-based Violence Interventions<strong>in</strong> Humanitarian Sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Focus<strong>in</strong>g on Prevention of and Response to Sexual Violence <strong>in</strong><strong>Emergencies</strong>. Geneva: Inter-Agency Stand<strong>in</strong>g Committee Task Force on <strong>Gender</strong> and HumanitarianAssistance. Available from http://www.humanitarian<strong>in</strong>fo.org/iasc/content/products/docs/tfgender_GBVGuidel<strong>in</strong>es2005.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Inter-Agency Stand<strong>in</strong>g Committee. (forthcom<strong>in</strong>g) IASC Guidel<strong>in</strong>es on Mental Health and PsychosocialSupport <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> (<strong>Education</strong> Action Sheets). Geneva: Inter-Agency Stand<strong>in</strong>g Committee.Available from http://www.humanitarian<strong>in</strong>fo.org/iasc/mentalhealth_psychosocial_support. Accessed04/10/06.Kirk, J. (2005) “<strong>Gender</strong>, <strong>Education</strong> and Peace <strong>in</strong> southern Sudan” <strong>in</strong> Forced Migration Review, No.24, November 2005, p. 55-6. Available from http://www.fmreview.org/FMRpdfs/FMR24/FMR2430.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Kirk, J. and W<strong>in</strong>throp, R. (2005) “Address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Gender</strong>-Based Exclusion <strong>in</strong> Afghanistan: Home-Based School<strong>in</strong>g for Girls” <strong>in</strong> Critical Half special issue on gender-based exclusion <strong>in</strong> post-conflictreconstruction, Women for Women International, Fall, 2005, Vol III, No 2, p. 26-31. Available fromhttp://www.womenforwomen.org/repubbiannual.htm. Accessed 04/10/06.Kirk, J. (2004) “Promot<strong>in</strong>g a <strong>Gender</strong>-Just Peace: <strong>The</strong> Roles of Women Teachers <strong>in</strong> Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g andReconstruction” <strong>in</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> and Development, November 2004, p. 50-59. Available from http://www.oxfam.org.uk/what_we_do/resources/downloads/gender_peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g_and_reconstruction_kirk.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Kirk, J. (2004) “Teachers Creat<strong>in</strong>g Change: Work<strong>in</strong>g for Girls’ <strong>Education</strong> and <strong>Gender</strong> Equity <strong>in</strong>South Sudan” EQUALS, Beyond Access: <strong>Gender</strong>, <strong>Education</strong> and Development, No. 9, November/December 2004, p. 4-5. Available from http://k1.ioe.ac.uk/schools/efps/<strong>Gender</strong>EducDev/IOE%20EQUALS%20NO.9.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Kirk, J. and Taylor, S. (2004) <strong>Gender</strong>, Peace and Security Agendas: Where are Girls and Young Women?Ottawa: <strong>Gender</strong> and Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Work<strong>in</strong>g Group of the Canadian Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>gCommittee [onl<strong>in</strong>e] Available from http://action.web.ca/home/cpcc/en_resources.shtml?x=73620.Accessed 04/10/06.11Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>Kirk, J. (2003) Women <strong>in</strong> Contexts of Crisis: <strong>Gender</strong> and Conflict. Background Paper for UNESCOGlobal Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Report. Paris: UNESCO [onl<strong>in</strong>e]. Available from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.php-URL_ID=25755&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Accessed 04/10/06.

Machel, G. (1996) <strong>The</strong> Impact of Armed Conflict on Children. New York: Secretary General, UnitedNations. Available from www.waraffectedchildren.com/machel-e.asp. Accessed 04/10/06.Machel, G. (2000) <strong>The</strong> Impact of Armed Conflict on Children. A Critical Review of Progress Madeand Obstacles Encountered <strong>in</strong> Increas<strong>in</strong>g Protection for War-affected Children. W<strong>in</strong>nipeg, Manitoba:International Conference on War Affected Children.Advocacy Brief <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>: <strong>The</strong> <strong>Gender</strong> <strong>Implications</strong>12Nicolai, S. and Triplehorn, C. (2003) <strong>The</strong> Role of <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> Protect<strong>in</strong>g Children <strong>in</strong> Conflict.Humanitarian Practice Network paper. London: Overseas Development Institute. Available fromhttp://www.savethechildren.org/publications/ODI<strong>Education</strong>Protection.pdf#search=%22<strong>The</strong>%20role%20of%20education%20<strong>in</strong>%20protect<strong>in</strong>g%20children%20<strong>in</strong>%20conflict.%20Humanitarian%20Practice%20Network%20paper%22. Accessed 04/10/06.Oxfam International. (2005) <strong>Gender</strong> and the Tsunami. Oxford: Oxfam International. Availablefrom http://www.oxfamamerica.org/newsandpublications/publications/brief<strong>in</strong>g_papers/brief<strong>in</strong>g_note.2005-03-30.6547801151. Accessed 04/10/06.Psychosocial Work<strong>in</strong>g Group (PWG) (2003) Psychosocial Intervention <strong>in</strong> Complex <strong>Emergencies</strong>: AFramework for Practice. Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh/Oxford: <strong>The</strong> Psychosocial Work<strong>in</strong>g Group. Available from http://www.forcedmigration.org/psychosocial/papers/A%20Framework%20for%20Practice.pdf. Accessed06/10/06.Reardon, B. A. (2001) <strong>Education</strong> for a Culture of Peace <strong>in</strong> a <strong>Gender</strong> Perspective. Paris: UNESCOPublish<strong>in</strong>g.Rehn, E. and Johnson Sirleaf, E. (2002) “Women, War and Peace. <strong>The</strong> Independent Experts’ Assessmenton the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role <strong>in</strong> Peace-build<strong>in</strong>g” <strong>in</strong> Progress of theWorld’s Women 2002; Volume 1. New York: UNIFEM.Rhodes, R.; Walker, D.; Martor, N. (1998) Where Do All Our Girls Go? Female Dropout <strong>in</strong> the IRCGu<strong>in</strong>ea Primary Schools. New York: International Rescue Committee.S<strong>in</strong>clair, M. (2002) Plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> and after <strong>Emergencies</strong>. Paris: UNESCO Publish<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>The</strong> Sphere Project (2004) Sphere Humanitarian Charter and M<strong>in</strong>imum Standards <strong>in</strong> Disaster Response(Sphere Handbook). Geneva: <strong>The</strong> Sphere Project.UNESCO International Institute for <strong>Education</strong>al Plann<strong>in</strong>g. (forthcom<strong>in</strong>g) <strong>The</strong> Guidebook for Plann<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> and Reconstruction (Chapter on <strong>Gender</strong>). Will be available at: http://www.unesco.org/iiep/eng/focus/emergency/emergency_1.htm/UNICEF and UNGEI (2006) Differentiated Needs and Responses <strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong>. Reach<strong>in</strong>g the Girls <strong>in</strong>South Asia. Katmandu: UNICEF & UNGEI.Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children (2006) Displaced Women and Girls atRisk: Risk Factors, Protection Solutions and Resource Tools. New York: Women’s Commission forRefugee Women and Children. Available from http://www.womenscommission.org/pdf/WomRisk.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Women’s Commission & <strong>Gender</strong> and Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Work<strong>in</strong>g Group of the Canadian Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>gCoord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g Committee. (2006) ‘Adolescent Girls affected by Violent Conflict: Why Should weCare?’ New York & Ottawa: Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children & <strong>Gender</strong>and Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Work<strong>in</strong>g Group of the Canadian Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Coord<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g Committee [onl<strong>in</strong>e].Available from http://www.womenscommission.org/pdf/AdolGirls.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. (2005) Don’t Forget About Us: <strong>The</strong><strong>Education</strong> and <strong>Gender</strong>-Based Violence Protection Needs of Adolescent Girls from Darfur <strong>in</strong> Chad.New York: Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Available from http://www.womenscommission.org/pdf/Td_ed2.pdf. Accessed 04/10/06.

AuthorJackie Kirk is a technical specialist on gender and education,focused on emergency, conflict and post-conflict contexts. Sheworks as an advisor to the International Rescue Committee (IRC)on education and child protection, and is a Research Associateat the McGill Centre for Teach<strong>in</strong>g and Research on Women,Montreal, Canada. Prior to this, she studied under a post-doctoralresearch fellowship at the UNESCO Centre, University of Ulsteron gender, education and conflict and has written extensively onthese topics. She has extensive field work experience from SouthSudan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Gu<strong>in</strong>ea and Sierra Leone and iscurrently lead<strong>in</strong>g an IRC action research project (a part of theHeal<strong>in</strong>g Classrooms Initiative) on teachers, classroom assistantsand sexual exploitation/abuse of girls and women <strong>in</strong> schools. Sheis also very <strong>in</strong>volved with the Inter-Agency Network on <strong>Education</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Emergencies</strong> as a resource person, tra<strong>in</strong>er and convener of the<strong>Gender</strong> Task Team.Also available are the follow<strong>in</strong>g advocacy/policy briefs:• Gett<strong>in</strong>g Girls Out of Work and Into School• Impact of Women Teachers on Girls’ <strong>Education</strong>• Mother Tongue-based Teach<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>Education</strong> for Girls• Provid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Education</strong> to Girls from Remote and Rural Areas• Impact of Incentives to Increase Girls’ Access to andRetention <strong>in</strong> Basic <strong>Education</strong>• Role of Men and Boys <strong>in</strong> Promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Gender</strong> Equality• A Scorecard on <strong>Gender</strong> Equality and Girls’ <strong>Education</strong> <strong>in</strong> Asia,1990-2000For more <strong>in</strong>formation, please visit UNESCO Bangkok’s <strong>Gender</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Education</strong> website at www.unescobkk.org/gender or writeto gender@unescobkk.org