Download PDF - Spink

Download PDF - Spink

Download PDF - Spink

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

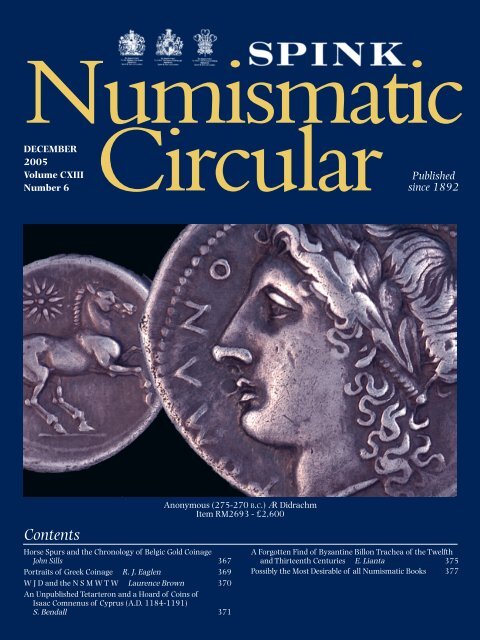

Dec 05 Cover 29/11/05 4:34 pm Page 2NumismaticCircularDECEMBER2005Volume CXIIINumber 6Publishedsince 1892ContentsHorse Spurs and the Chronology of Belgic Gold CoinageJohn Sills 367Portraits of Greek Coinage R. J. Eaglen 369W J D and the N S M W T W Laurence Brown 370An Unpublished Tetarteron and a Hoard of Coins ofIsaac Comnenus of Cyprus (A.D. 1184-1191)S. Bendall 371Anonymous (275-270 B.C.) ¿ DidrachmItem RM2693 - £2,600A Forgotten Find of Byzantine Billon Trachea of the Twelfthand Thirteenth Centuries E. Lianta 375Possibly the Most Desirable of all Numismatic Books 377

Dec 05 Cover 29/11/05 4:34 pm Page 3The Duke of Ormond’s Gold Coinage of 1646, Pistole (S.6552),one of only twelve recorded examples and the finer of the two examples in priveate hands.<strong>Spink</strong> is delighted to announce the sales ofTHE Lucien LaRiviere COLLECTIONSof Irish and Scottish Coins and MedalsLucien has always been an avid collector. His early purchases were United States stamps, but his love ofhistory led him to look at collecting fields beyond the confines of the 19th century, and he was soon a passionatecoin and medal collector. His first numismatic purchases were once again American, but having acquired a1723 Halfpenny and a St. Patrick Coinage Farthing at two U.S. auctions in 1968, he became increasinglyinterested in Irish and Scottish coins. The fruits of nearly 40 years of collecting in these two areas will bepresented in two auctions scheduled for February and March 2006. A selection of highlights from thetwo collections can be seen on pages 378 and 379. Both catalogues will be sent to all subscribers, but individualcopies will of course be available from the coin department approximately four weeks before the auction.

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 367The Numismatic Circular Published since 1892December 2005 Volume CXIII Number 6ContentsHorse Spurs and the Chronology of Belgic Gold CoinageJohn Sills 367Portraits of Greek Coinage R. J. Eaglen 369W J D and the N S M W T W Laurence Brown 370An Unpublished Tetarteron and a Hoard of Coins ofIsaac Comnenus of Cyprus (A.D. 1184-1191)S. Bendall 371A Forgotten Find of Byzantine Billon Trachea of the Twelfthand Thirteenth Centuries E. Lianta 375Possibly the Most Desirable of all Numismatic Books 377Our list of numismatic items and books offered for salefollows on page 380Horse Spurs and the Chronology of BelgicGold CoinageJohn SillsIn class 6, however, they become attached to one of the rearlegs of the horse and a single curved line appears on the otherrear leg, so that the horse appears to have spurs (fig. 3). Duringthe transition from Ca1 to E, the uniface type, one of the lines islost and the horse is left with a single spur on each rear leg (fig. 4).Identical single spurs are seen on classes 1 and 2 of Gallo-Belgic F (fig. 5) and at the start of the closely related anchor type,the prototype for British Qa, which I will define as Gallo-Belgic G(fig 6); as far as I can see they occur on no other major Gaulishseries. Because their evolution can be traced almost die by die atthe very end of Ca1 there can be no doubt that the start of Gallo-Belgic F and G postdates the end of Ca, making it likely that E, Fand G all began at approximately the same time.A seemingly unremarkable feature of Gallo-Belgic A, the largeflan series of Belgic Gaul, is the presence of two curved linesbelow the ‘coffee bean’ motif behind the horse (fig. 1). This coffeebean is the last remnant of the chariot wheel on staters of Philipof Macedon, and the lines may represent a miscopied sectionof the wheel. Be that as it may, they first appear on class 2 ofGallo-Belgic Aa1, the right-facing stater series, and continuelittle changed into class 5 of its direct successor, Gallo-Belgic Ca1(fig. 2).The distinctive eye staters of eastern Gaul (figs 7-8) have manygeneral similarities with Gallo-Belgic F, probably struck by theSuessiones (Scheers, 1977, p.369-373). They are struck to thesame initial standards of weight and fineness, a touch lower thanclass 1 of the uniface series, and both have a prominent eye motifon the obverse. Scheers thought that the eye developed first on F,but this cannot be proved: it appears fully formed soon after thestart of class 1 and is more likely to have been lifted from the eyeseries proper, as Haselgrove suggested (1984, p.84-85, fig. 2). Thesame is true of the arcs around the pellet border on the reverse, arare trait paralleled on the obverse of some class 1 eye staters (fig.8). Several eye staters, however, have a crescent-shaped exergue,sometimes with a flattish top (fig. 7), a feature that develops onclass 6 of Gallo-Belgic Ca (fig. 3); the flat-topped crescent firstappears at the start of E class 1 and is one of its defining elements(fig. 4). Because every stage in the evolution of this feature is seenon Ca and E it appears that the direction of influence is from thebiface and uniface types to the eye series, not vice-versa.Metzler (1995, p.131-134) and Pion (2003, p.390-396) havereassigned classes 1-3 of the eye series from the Treveri to theRemi, leaving the former with classes 4-6. Their arguments fromtypology and distribution are wholly convincing, and from ahistorical viewpoint it makes a great deal of sense if class 1 eyestaters and Gallo-Belgic F were struck by the Remi and Suessionesrespectively, for Caesar tells us that the two groups ‘shared thesame jusisdiction and laws, and also the same government andmagistracies’ (B.G. 2.3).DECEMBER 2005 367

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 368Scheers suggested in 1972 that correlations in typology,weight and fineness between Gallo- Belgic E, F, the eye series andother late small flan issues of Belgic Gaul show that they allpostdate Gallo-Belgic Ca and are contemporaneous; sheconcluded from this that they are wartime coinages struck inresponse to Caesar’s invasions of Belgic Gaul and therefore date toc.57-51 BC (p.1-6). The present author has completed a die studyof Gallo-Belgic E that further accentuates the difference involume between it and previous series, and agrees that the GallicWars offer the only rational explanation for the striking of such ahuge volume of gold (Sills, 2005, p.2-6). At the other end of thespectrum Haselgrove’s modification to Scheers’ système belge, inwhich the eye issues are derived independently of Ca and F (1984,p.84-85, fig. 2), has allowed that author and Pion to argue fromarchaeological evidence that the eye series could have begun inthe late 2nd century BC, and was certainly in existence well beforethe Gallic Wars (Haselgrove, 1999, p.137-138; Pion, 2003,p.397). Both explicitly reject Scheers’ idea of a raft of wartimeissues dated to a very narrow horizon, and opt for a range of halfa century or more for what she compressed into less than adecade.The study of Belgic coinage has therefore become polarizedinto historical and archaeological explanations, the formerlinking gold coinage to political and especially military events andthe latter relating it to broader, more gradual social developments.The typological links outlined here bring this crisis to a head, forthey show that Scheers’ idea of a single raft of high-volumecoinage is essentially correct. It is no longer possible to argue,for example, that Gallo-Belgic E is a wartime coinage but thatGallo-Belgic F, G and the eye series began earlier: Scheers’hypothesis must stand or fall in its entirety.Haselgrove has summarized archaeological data from severalsites that seems to show that the inception of the two eye series,the related aux segments de cercles quarters (Scheers series 152)and possibly Gallo-Belgic E itself predate the Gallic Wars (1999,p.137-140). The evidence is not as clear-cut as it appears,though. The absolute chronology he prefers for the late La Tèneperiod gives earlier dates than other versions but is presentedwithout discussion of the alternatives (ibid, p.116; Colin, 1998,p.20-24). He cites the presence of class 1 eye staters at St.-Thomas, Aisne, abandoned around the La Tène D2a/D2btransition (La Tène D2a is dated by him to c.90-60 BC and D2b toc.60-20), to argue that the series began before the Gallic Wars.However, as he notes (p.137, n.119), St.-Thomas is probably theRemic oppidum of Bibrax besieged by a Belgic army in 57 BC andsubsequently relieved by Caesar (B.G. 2.6), so there is no reasonwhy the early eye staters from the site could not have been struckin 58/7 and buried in 57 in response to these events:archaeological dating is simply not precise enough in this case todistinguish between a coin buried in, say, 80 BC and one buried inthe early 50s. The same arguments apply to a silver series thatcopies eye class 1 and was probably struck in parallel with itfrom a La Tène D2a context at Villeneuve-St.-Germain, Aisne(p.137-13 8, n.120). This leaves a single class 1 stater from thefilling of a pit at Condé-sur-Suippe, Aisne, dated to La Tène D1b(c. 120-90 BC) as the only seemingly clear evidence of pre-GallicWar date; even here, though, Haselgrove acknowledges that thereare no precise details of where the coin was found within the pitand urges an open mind in case the coin is intrusive (p.137,n.118). Given the incompatability between it and the St.-Thomasfinds, the problems of residuality and the subsequent, oftenunobserved disturbance of early features on all complexarchaeological sites, it would seem unwise to rest any chronologyon this slender thread.Haselgrove also suggests that the other small flan coinages ofcentral and eastern Belgic Gaul, principally eye class 4, theepsilon staters of the Nervii and the triskeles staters of theEburones, were also introduced well before the end of La TèneD2a (1999, p.141-142). Nico Roymans, however, has recentlylooked again at the dating evidence for the triskeles type from bothan archaeological and a numismatic perspective and hasconcluded that Scheers’ linking of the series to the defeat of theEburones in 53 BC is probably correct (2004, p.38- 44). Epsilonand triskeles staters have been found together in two Belgianhoards, Fraire-2 and Heers; the latter contained a Pottina stater(eye class 5), unquestionably struck well into the Gallic Wars, andthere can be little doubt that all the coins in the hoard are broadlycontemporary (ibid, p.44, fig. 4.8). There are no grounds forthinking that any of these series began before the Wars, andHaselgrove’s assertion that new varieties of early epsilon staterfrom the Thuin, Belgium hoard imply an earlier start for the seriesis not valid (1999, p.141, n.141): there are no varieties that donot fit into Scheers’ existing classification, and what he takes tobe differential circulation wear between types is mainly die wear(Van Heesch, 1991, fig. p.6; Frébutte et al, 1992, fig. p.25). TheOdenbach, Rheinland-Pfalz hoard contained at least five (andprobably many more) class 1 staters alongside examples of classes2, 4 and 5, and, once again, the presence of Pottina staters andthe lightly worn state of the class 1 staters indicates a shortrather than long chronology (Scheers, 1977, p,891-892, hoard60).Pion has argued that the attribution of class 1-3 eye staters tothe Remi is another nail in the coffin of the système belge, as thetribe were allies of Rome from the start and could not have beenpart of a supposed Belgic currency block (2003, p.397). In factthis modification brings the numismatic and historical evidencemore closely into line. The division of Scheers series 30 into twomore or less parallel coinages, each with one uninscribed and twoinscribed classes, makes a short chronology easier to accept. Theassignment of the heavy and typologically early class 1 eye statersto the Treveri has always been a problem, for the tribe appealed toCaesar for help in 58 BC, supplied him with cavalry the followingyear and only became hostile in 56 (B.G. 1.37; 2.24; 3.11). It issignificant that a large proportion of the provenanced class 1staters are from Treveran territory (which is partly why Scheersassigned them to the tribe), and one of the reasons that the Remistruck them may have been to pay Treveran auxiliaries in gold onCaesar’s behalf. It must not be forgotten, also, that the Remithemselves came under attack from the Belgic coalition in 57 andmay have needed to finance their own defence (B.G. 2.6-7). Arecent hoard of class 1 staters dispersed in trade shows that theprincipal varieties, 1a-c and e, were probably struck in rapidsuccession; when Scheers’ die study is updated it becomes clear inaddition that class 1 was a huge coinage, comparable in scale toclass 1 of Gallo-Belgic E, and as with the latter it seems unlikelythat any event or set of circumstances outside the Gallic Wars canfully account for this.An unusual feature of Gallo-Belgic F and the class 1 eye statersis their mutually exclusive distribution (Pion, 2003, p.395, fig. 5).Other Belgic series usually show a substantial overlap: Gallo-Belgic E and the epsilon staters of the Nervii, for example, andGallo-Belgic F and G. Given the intimate relationship between theRemi and Suessiones before the Gallic Wars the most likelyexplanation is that this separation reflects the split that occurredat the start of the Wars, which would also explain the ‘similar butdifferent’ typology of their respective coinages.I have tried to show in this brief piece that the proposition thatclosely related Belgic small flan coinages were struck in differentarchaeological periods fails on numismatic grounds, and thatrecent modifications to Scheers’ 1972 and 1977 classificationshave strengthened rather than weakened the arguments infavour of them being Gallic War issues. The time is coming whenarchaeologists may need to re-examine and publish in greaterdetail the evidence that purports to show otherwise.BibliographyColin, A. 1998: Chronologie des oppida de la Gaule non méditerranéenne (Paris,Documents d’Archéologie Française 71).Frébutte, C., Vandeur, M. and Horemans, J.-M. 1992: Les Celtes et la Thudinie.Autour du trésor monétaire nervien de Thuin (Thuin).368 NUMISMATIC CIRCULAR

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 369Haselgrove, C. 1984: Warfare and its aftermath as reflected in the preciousmetal coinage of Belgic Gaul. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 3, p.81-105.1999: The development of Iron Age coinage in Belgic Gaul. NC 159,p.111-168.Metzler, J. 1995: Das treverische Oppidum auf dem Titelberg (G.-H. Luxemburg)(Luxembourg).Pion, P. 2003: L’or des Rèmes. In Plouin, S. and Jud, P. (eds). Habitats, mobilierset groupes régionaux à l’âge du fer. Actes du XXe colloque de l’A.F.E.A.F.,Colmar-Mittelwihr, 16-19 mai 1996 (Vesoul), p.387-401.Roymans, N. 2004: Ethnic identity and imperial power. The Batavians in the earlyRoman empire (Amsterdam).Scheers, S. 1972: Coinage and currency of the Belgic tribes during the GallicWar. BNJ 41, p.1-6.1977: Traité de numismatique II. La Gaule belgique (Paris).Sills, J.A. 2003: Gaulish and early British gold coinage (London).2005: Identifying Gallic War uniface staters. Chris Rudd 83, p.2-6.Van Heesch, J. 1991: Le trésor gaulois de Thuin/De gallische schat van Thuin(Brussels).Portraits of Greek CoinageR. J. Eaglen7 – MessanaObverseReverse¿ Tetradrachm c. 430 BCObv. Charioteer wearing a long tunic (χιτών) and driving abiga of mules slowly r., holding reins in both hands and a rod orgoad (κέντρον) in right. Above, Nike flying r. with fillet (?) in l. andcrown of olive leaves in r. hand, held over mules’ heads. Inexergue, an olive leaf and fruit.Rev. Hare bounding r., above dolphin r. ΜΕΣΣΑΝΙΟΝ around.17.12g (25mm diameter).Author’s collection. Ex Baldwin, 2005.Messana lay in the north-eastern corner of Sicily, by the narrowstraits separating the island from the toe of Italy. The city wasknown as Zancle when Anaxilas, tyrant of Rhegium on the otherside of the straits seized it in about 489 BC, but shortly after it wasrenamed Messana 1 . After Anaxilas’ death his sons ruled over bothcities until they were ousted in 461 BC 2 .Anaxilas introduced the biga of mules and hare type inRhegium and in Messana 3 . The obverse design alluded, on theauthority of Aristotle 4 , to the victory of Anaxilas’ biga in theOlympian games of 484 BC or, more probably, 480 BC 5 . Althoughthe glory was his, doubtless the achievement was that of hischarioteer 6 . In the classical period, the games lasted for five days 7 ,with chariot racing on the second morning 8 . It is hard to imagine,however, that mule biga racing enjoyed the same standing inspeed or panache - not to say thrills and spills 9 - as the races withtwo and four-horse chariots. The event is believed to have beenintroduced, in 500 BC, at the instigation of the Sicilian Greekswho were famed for their mules, but was discontinued after thegames of 444 BC 10 .At Rhegium, the biga type had been superceded before theoverthrow of the tyrants 11 , but at Messana it survived withvarious changes in treatment until the city was destroyed by theCarthaginians in 396 BC 12 . Initially, the charioteer was portrayedbearded, crouched on a mule cart with a box seat, but later diesshow a clean-shaven charioteer with full-length tunic, standingin profile in a vehicle of similar design to that used for horsechariot racing. From about 430 BC 13 dies are encountered wherethe charioteer has been identified as the city goddess, Messana,because her name appears in the obverse field 14 . However, longhair and tunic, and lack of a beard, were not exclusively femaleattributes. Moreover, if the coin type was rooted in an Olympianvictory, a female charioteer would not be expected, especiallywhen, on other dies, the name is absent and Nike appears instead,bearing a victory wreath. At the games only one event, ashortened foot-race (στάδιον) 15 , was open to women, althoughwomen and even states were known to have sponsored chariotteams 16 . It is thus conceivable that the name Messana wasengraved on obverse dies to celebrate victory by a civic chariot,entered in honour of the city’s goddess. Examples arenevertheless encountered at the end of the fifth century BC offemale charioteers on coins from Syracuse 17 and probably on diesfrom Messana, showing the biga being driven left by a threequarterfacing, distinctly bosomy charioteer 18 .Kraay, in Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, suggested that Nikehad been added only from about 460 BC, either to emulate theprestigious obverses issued by Syracuse, or to celebrate an actualvictory by a citizen of Messana 19 . Another possibility is that Nikewas added to commemorate victory over the tyrants rather thana sporting triumph. On the coin illustrated Nike is flying right, buton others she balances upright on the charioteer’s reins 20 . Thisconceit is less aesthetically satisfying because it fails to soften thepredominantly vertical symmetry of the overall design.For most of the issue the reverse shows the hare bounding orleaping right, with various symbols beneath its belly. Of these,the dolphin is most commonly met. The earliest coins of Zanclealso bore a dolphin on the obverse, pointing to an emblematiclineage 21 . Dolphins clearly gave rise to the same fascination andaffection in the ancient world as they do today. This is reflected inthe story of Arion, who evaded death in the clutches of amurderous ship’s crew by being borne to safety on a dolphin’sback 22 .Aristotle also gave an explanation for the hare, intimating thatAnaxilas had introduced the species to Sicily. It would perhaps bemore plausible if such ‘hares’ could be taken to refer to the cointype rather that the animal itself 23 . The hare is usually associatedwith Pan, for whom it was a quarry 24 . On the coins of Messana,however, they are carefree creatures. As if to emphasise this, onereverse design shows Pan petting a hare poised before him on itshind legs 25 . The hare’s face is often executed amusingly, as on thecoin illustrated, a touch that would have made even Walt Disneyproud.Footnotes:1. The Oxford Classical Dictionary (OCD), edited by Simon Hornblower andAnthony Spawforth, 3rd edn revised (Oxford, 2003), p.963. N. G. L.Hammond, A History of Greece to 322 BC, 3rd edn (Oxford, 1986) followsThucydides, 6.4.6, in linking the change of name to expulsion of theSamians.2. Barclay V. Head, Historia Nummorum, (Oxford, 1911), p.153.3. David R. Sear, Greek Coins and their Values, I (London, 1978), No. 496(p.54) and 842 (p.88).4. Aristotle, fr. 578 R.5. Colin M. Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins (London, 1976), p.214.6. OCD, p.727; Judith Swaddling, The Ancient Olympic Games, 3rd edn(London, 2004), p.87.7. OCD, p.1066.8. Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins, Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece(Oxford, 1997), p.420; The Ancient Olympic Games, p.53.9. In one such race only one of the forty (The Ancient Olympic Games, p.37)or forty-one chariots finished (Life in Ancient Greece, p.420).10. The Ancient Olympic Games, p.87.11. Sear, I, No. 498 (p.55).12. Ibid., Nos. 846 - 852, pp.88-89; OCD, p.963.13. Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, p.219.14. C. M. Kraay and Max Hirmer, Greek Coins (London, 1963), Plate 18, 56.15. OCD, p.207.16. The Ancient Olympic Games, pp.41, 97.17. Greek Coins, Plate 38, 109 (c.410 - 400 BC).18. Ibid., Plate 18, 58 and 19, 60-61 (c.410 - 400 BC).19. Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, p.219.20. Sear, I, No. 851 (p.89).21. Ibid., Nos. 721- 722 (p.76).22. Heroditus, The Histories, 1, 23 -24.23. Kraay, Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, p.214.24. OCD, p.1103.25. Kraay and Hirmer, Greek Coins, Plate 16, 57 (reverse).DECEMBER 2005 369

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 370W J D and the N S M W T WLaurence BrownThe laudatory medal of William John Davis (1848-1934),eminent trades unionist and noted numismatist, was one of themany medals listed by Colonel M. H. Grant in an addenda to hisCatalogue of British Medals Since 1760, (BNJ vol.XXIII, 1940-41,p. 478). It is also described in detail in British Historical Medals,1760-1960, vol. III No. 3869 (gilt copper) wherein it is noted thatthe author had been unable to decide on what occasion the piecehad been issued, but presumably on behalf of the AmalgamatedMetal Wire and Tube Makers, of whom no record had been found.The illustration at the head of this present note is of a specimen ofthe medal in white metal in the author’s possession.Recent research at the Trades Union Congress library has shedmore light on the subject. The correct name of the Union appearsto have been The National Society of Metal Wire and TubeWorkers and it was, indeed, founded in 1896 as shown on themedal. The Union was established with a membership of 1,500and briefly grew to 1,645 members in 1899 but then fluctuatedwidely over the succeeding years until, in 1949, the membershiptotalled just 100.The authors of the Historical Directory of Trade Unions note‘It appears to have gone out of existence in 1950, there being nonotice given of an amalgamation with any other union 1 .’ Forthe whole of its life the registered head office of the Society was at22 Summer Row, Birmingham.No firm evidence has been discovered among the few survivingdocuments of the Society in the T.U.C. Library as to why the date1902 was chosen for the medal and in the papers examined Davis’name does not feature among the officers of the Society. However,Davis was of considerable importance in the trades unionmovement and served as a member of the parliamentarycommittee from 1896 until 1915 with a break in 1902,apparently caused by his attitude to the Boer War, being ‘opposedto the view that Congress should speak out against the War,opining that it should be carried though to a finish in the interestsof the worker in South Africa 2 ’. In 1902 Davis was chairman ofthe Labour Representation Committee (in 1906 it became theLabour Party) and was in the chair at the LRC Conference atBirmingham in that year 3 .It may have been as a result of his being Chairman at thatconference that the NSMWTW chose to feature Davis soprominently on the obverse of the medal. The effigy of Davis bearsresemblance to a photograph of him reproduced in the BritishNumismatic Journal 2003 Centenary volume, pl.13 (a). This alsoappears in a history of the National Society of Metal Mechanics 4 .Here, the author notes that it is ‘From a photograph by Lafayette’.This can probably be attributed to the photographic studiofounded by James Lafayette which traded as Lafayette Ltd at 178-9 New Bond Street, London, W1, c. 1897-1908The reverse of the medal depicts a winged standing femalefigure, presumably Liberty, holding a staff topped with a Phrygianbonnet, frequently called a cap of Liberty, and an inverted fasces,the latter being a bundle of elm or possibly birch rods enclosing anaxe and bound with red thongs, the emblem of the superiorRoman magistrates. It is also a symbol of unity; but does not,however, appear to have been an attribute of Liberty 5 . Theseemblems carried by the Lictors of Rome were held over theirshoulders with the axe head toward the top of the bundle. Thefasces is also occasionally depicted with other emblems onthe coinage of the Roman Republic and on that issued byC. Norbanus, c. 83 BC, for example, it is shown inverted (Crawford357/1) 6 : perhaps there is some significance in the fact that on theNSMWTW medal Liberty is holding an inverted fasces.P. Valerius Publicola (Consul, 506 and 505 BC, died 504 BC) achampion of popular rights, established the custom that thefasces were to be lowered before the people since Publicolabelieved that their power was superior to that of the Consuls (Livyii,7, Florus i, 9).Even though Davis had apparently lacked a formal education,as a trades unionist and a numismatist of wide interests, it ispossible that he was aware of the importance of this act and ifconsulted by the union on the design of the medal requested thatthe engraver depict in a pictorial form how the power of thepeople should be regarded from henceforth. It seems likely thoughthat the significance of this would have been lost on those tradesunionists who were not as well read as Davis.Alternatively, if Davis had had little to do with the issue of themedal, but simply agreed to his portrait being depicted on theobverse, the reverse design being left to the medallist, the invertedfasces may simply be a happy coincidence. The carelessness in thename of the union is not, however, so fortunate.The medal is signed ‘R’ to the left of Liberty’s staff and itwould not be unreasonable to think that this is the signature ofJ. A. Restall (fl. 1873-1914), a Birmingham jeweller, silversmith,die-sinker and medallist who, among his other medallic work, cutdies for personal new year tokens (Tickets and Passes, 342/9-12,343/19-43) for W. J. Davis and S. H. Hamer 7 .Footnotes:1. Historical Directory of Trades Unions, Arthur Marsh and Victoria Ryanvol. 2. Gower Publishing 1984, p.172.2. The Life Story of W. J. Davis, J.P. The Industrial Problem. Achievements andTriumphs of Conciliation, W. A. Dalley, Birmingham 1914.3. Dictionary of Labour Biography, Ed. Joyce M. Bellamy and John Saville vol.VI, Macmillan, 1992, p.94.4. Founded in Brass, The First hundred Years of the National Society of MetalMechanics, from Chandeliers to Concorde, Malcom Totten, 1972, p.11.5. Dictionary of Subject and Symbols in Art, James Hall, John Murray, revisededn. 1996, p.119.6. Roman Republican Coinage, M. Crawford, Cambridge University Press,1974.7. A Dictionary of Makers of British metallic tickets, checks, medalets, tallies andcounters, 1788-1810, R. N. P. Hawkins, ed. Edward Baldwin, p.424For New Milled Copper and Bronze coinsplease see the latest updates to our websitewww.spink.comAlternatively come and see our extensivestock at our officesMonday to Friday – 9.30 am to 5.30pm370 NUMISMATIC CIRCULAR

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 371An Unpublished Tetarteron and a Hoardof Coins of Isaac Comnenus of Cyprus(A.D. 1184-1191)S. Bendallwritten in full. The I is surmounted by two pellets, a form of theletter that does not reappear on the coinage until it was usedninety years and more later in sigla on the hyperpyra ofAndronicus II and of Andronicus II and Michael IX. The onlyprevious tetarteron bearing a monogram had been that ofManuel I (DOC IV, 20) which Hendy dated to c. 1143-1152. Onthis the letters of the monogram, ΜΛΔΠΚ(Manuel, Despot andKomnenos), are arranged in the order used in making the sign ofthe cross in the Orthodox church but this is certainly not the casewith the monogram on this new coin.In February and May 1989 the writer published a new type ofelectrum trachy of Isaac of Cyprus and discussed briefly the entirecoinage of this emperor 4 . In 1969 Hendy had listed seven typesfor Isaac attributing two issues to the main mint, possibly Nicosia,and a single issue to a secondary mint which he suggested mightbe Limassol or Famagusta 5 . There now appear to be possibly 16different types for the reign of which Hendy listed 13 in DOC IV 6as did the writer in both his 1989 articles.Byzantine Cyprus had previously had only a single mint underHeraclius 7 but Isaac had two mints as the Lusignans did later, butpossibly not the same two mints. In DOC IV Hendy attributedthree issues to the main mint, possibly Nicosia, and the singlesecondary mint, possibly Limassol or Famagusta, striking twoissues which can be deduced from the fact that tetartera ofHendy’s original secondary mint A are found overstruck ontetartera which he had listed as uncertain issues in 1969 (DO 9over 10). It is obvious that they are successive issues from a singlesecondary mint 8 , but what mint this might have been isuncertain.In 2002 the writer discussed a rare coin with a monogram on thereverse, attributing it to Richard I Lion-heart, suggesting that itwas issued in Cyprus while Richard ruled there briefly in mid-1191 1 . In the addendum of that article the writer mentioned thatthere existed what he thought was a unique tetarteron of Isaac ofCyprus with a monogrammatic reverse in a Cypriot collection. Atthat time the writer had only a very dark photocopy of aphotograph of this coin which was too poor to publish 2 .Another specimen of this rare tetarteron has recently appeared(fig. 1) and the writer has been able to copy the originalphotograph of the earlier specimen (fig. 2). Both coins are in goodcondition and struck from different dies and illustrated hereslightly larger than twice actual size 3 .Obv. [ ] BOH - Θ H.Rev. Monogram as fig. 3.Die axes. 6 o’clock; Wt. (fig 1) 1.91 gm.The obverse legend is most unusual and is surely an abbreviationof ‘Kyrie Boethei’, ‘Lord protect’. The first H appears to the right ofthe top of Isaac’s sceptre and to the left of his head. Before BOthere appears to be room for only two letters, presumably KE, acommon abbreviation of ‘Kyrie’. With this form of obverse legendthe monogram should be composed of the letters that form thename and title of Isaac. The letters Δ (at the mid-point of thelower part of the vertical line), Π and Τ, abbreviating the title‘Despot’, are clear as are the I and K of ‘Isaakios’. It is possible thatthe letter above the left side of the horizantal line could be an Abut what the semicircle beside it to the left but below the linemight be is uncertain. It is possible but unlikely that it representsa simplified ω, since this letter is not used in the spelling of eitherIsaac’s name or title. It can hardly represent the greek S, writtenas C, which would appear four times in Isaac’s name and title ifFigure 4Mints.Cyprus was predominantly rural with few urban centres, noneof which were walled before the Lusignan period 9 . In 1196 theLatin Church was established with the archbishopric at Nicosiaand suffragans at Paphos, Limassol and Famagusta 10 , one ofwhich was presumably the secondary Lusignan mint. Distancesare comparatively short. Limassol is only slightly more than 40miles from Nicosia as the crow flies, Famagusta slightly less whileKyrenia is only 16 miles to the north of Nicosia. Paphos has alsobeen suggested. (see map, figure 4).Nicosia appears to have been the capital at the time and everyauthority has suggested it as the likely primary mint. It certainlyappears to have been so in the Lusignan period although GeorgeJeffery seems to have considered the place of little importanceunder Isaac 11 although the emperor retreated to the castle atNicosia after his initial defeat by Richard I.Limassol or Amathos. Limassol, today Lemessos and possiblyNeapolis/Theodosias in the Roman/early Byzantine period isdescribed as being one of several new cities founded in the 11th -12th centuries near deserted sites of antiquity (in this caseAmathos) 12 . It only seems to have been of modest importanceuntil the fall of the Crusader state, being possibly only a largevillage in the Byzantine period although the site of a fort. It was,however, a Latin bishopric from 1196.DECEMBER 2005 371

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 373Addendum ISuggested arrangement of issuesMain Mint1st issueEl. trachy. DO 1; S. 1990.Bill. trachy DO 2; S. 1991.Æ Tetarteron DO 6; S. 1993.Æ Half tetarteron DO 11; S. ——.2nd issueBill. trachy DO 3; S. 1992.Æ Tetarteron DO 7; S. 1994.3rd issueEl trachy DO (1 bis); S. —-; NCirc., May 1989 22 .Bill. trachy DO ——; S. —-; NCirc., Oct. 2001 23 .Æ tetarteron. DO 8; S. —-.Uncertain issuesÆ tetarteron The new type published in this article.Æ tetarteron Unpublished type (fig. 5 ) 24 .Secondary Mint1st issueBill. trachy DO 5; S. 1997.Æ tetarteron DO 10; S.1998.2nd issueBill. trachy DO 4; S. 1995.Æ Tetarteron DO 9; S. 1996.Uncertain issueÆ tetarteron Bust of St. George/Bust of Isaac. DO (8 bis)and Hendy 1985, pl 31, 13 and footnote 18.Addendum IIIn the addendum to his 2002 article (see footnote 1) the writermentioned metal analyses of ‘billon’ trachea and ‘copper’tetartera of Isaac from a hoard that the writer stated, incorrectly,that he had acquired in the summer of 1990. These analysesindicated that both the ‘billon’ trachea (DO 2) and the ‘copper’tetartera (DO 8) contained a similar small amount of silver 25 . Thewriter is ashamed to confess that he never made a record of thehoard but he has recently discovered a certain amount ofinformation about it in a folder found at the back of a filingcabinet which contained the draft of an article printed out on the12 May 1989 at a time when the writer was employed byNumismatic Fine Arts in Los Angeles.By the 12th May the writer had obviously learned of theexistence of a hoard of copper coins of Isaac of Cyprus andnoted that it had contained c. 50 trachea of DO 2 26 , 12 tetarteraof DO 8, three previously unknown trachea of a similar design,the type published by the writer in 2001 (footnote 23) andapparently a single tetarteron of DO 10 and that he had been ableto examine 21 of these coins but without giving any details exceptthat this group did not contain the tetarteron of DO 10. He alsostated that the entire hoard had been acquired by a Cypriotcollector although two other local collectors had each been able toacquire a few coins of the hoard from the purchaser. The writerwould certainly not have seen these 21 coins in America butpossibly in London on a business trip. He has a letter from aLondon dealer dating to the following month saying that thedealer had been pleased to see the writer ‘recently’.The writer must have written immediately to a Cypriot contactin Nicosia (collector A) since his file contains a letter from him,dated 12 May 1989 which arrived in Los Angeles on the 23rd, inwhich the collector stated that there had been such a hoard foundrecently in Cyprus, giving the following information. The hoardhad been ‘dispersed’ before any record could be made but that hehad been shown 23 trachea of DO 2 and 4 tetartera of DO 8. Therarity of DO 8 can be judged by the fact that the collector had notknown of the existence of this type of tetarteron until theappearance of this hoard. Collector A was unable to photographthese coins but the owner promised to sell him specimens ofwhich collector A would send the writer photographs which henever received.The writer, in fact, purchased what must have been the bulk ofthe hoard at the British Numismatic Trade Association coin fair inLondon in October 1989 from a Greek Cypriot (collector B) wholived in Limassol. Although the writer made no list of these coins,he does have a note of the total cost of the hoard and the prices hereceived for several of the coins which which leads him to thinkthat he purchased about 50 specimens of DO 2, several tetarteraof DO 8 and three of the previously unknown billon trachea, oneof which he sold to the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, one to anAmerican collector, keeping one which he later published in2001. However, it appears that collector B had previously offeredthis hoard to Baldwins at the time of the BNTA coin show beforehe sold it to the writer since Baldwin’s consultant on Byzantinecoins made a note of the hoard at that time with a breakdown ofthe individual prices. According to these notes there were 48trachea of DO 2, several with retrograde legends, five tetartera ofDO 8, three of the ‘new’ trachea and a single trachy of DO 5 27 .Baldwins did not purchase the hoard and in fact the writer paid£1000 less than they had been asked.It would not surprise the writer if it had been collector B whohad shown collector A a selection of the hoard, but not any of thenew trachea (see footnote 23) and he may well have sold a fewcoins to fellow collectors but kept some of the better specimens forhimself, presumably including the best of the new type of billontrachy. It does not come as a surprise that collector B sold the bulkof the hoard in London (including the three remaining newtrachea) since he would have certainly made more money than byselling them to fellow collectors in Cyprus judging by the pricesthe writer had to pay for this hoard and other individual coinspurchased over the previous 25 years 28 .It is difficult to judge the composition of this hoard but itprobably did not exceed more than about 70 coins of which themajority were trachea of DO 2 with perhaps a dozen tetartera ofDO 8 and possibly only four specimens of the previoulyunpublished trachy published by the writer in 2001. The writerhas no recollection of acquiring any coins other than those ofthese three types but in his draft article of May 1989 he did notea single tetarteron of DO 10 but only by report. Baldwin’s notesdo not mention this coin but listed a trachy of DO 5. Both coinshave the same obverse of Christ seated on a throne and it ispossible that there was only one coin of the secondary mint’s firstissue in the hoard and this is more likely to have been a trachythan a tetarteron since Baldwins made a note of the compositionof the hoard. That there were no more coins might be confirmedby the fact that no coins of these types, or any others, seem tohave appeared on the market in the next two or three years otherthan those sold by the writer which surely indicates that thosecoins that he did not purchase were acquired by Cypriotcollectors.It would be of some interest to know the provenance of thishoard but, as noted, distances are not great in Cyprus. That thishoard was acquired by a resident of Limassol does not mean thatit was found in the vicinity of that city. If Cyprus is anything likeGreece, collectors establish a widespread network of personalsuppliers and distances in Cyprus are not as great those in Greece.Wherever this hoard was found, presumably outside Turkishoccupied Cyprus 29 , it is unlikely that it was found near theDECEMBER 2005 373

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 374secondary mint, wherever that might have been, otherwise itshould have contained a few coins of the last issue of thesecondary mint unless, of course, the two issues of the secondarymint were contemporary with the first two issues of the mainmint and the secondary mint had closed before the end of Isaac’sreign after which the only coins commonly available wouldpossibly only have been billon trachea of the first issue 30 and thetrachea and tetartera of the third issue of the main mint whichmight account for the fact that there was only a single coin of thefirst issue of the secondary mint and no coins of the second issueof the main mint in the hoard since all coins of Isaac except forDO 2 are very rare.The writer would like to thank Dr. D. M. Metcalf, Dr. W. Schultze,Dr. I. Touratsoglou, Ms. Yorka Nicolaou and Mr. T. Eden for theirhelp. The suggestions put forward here are entirely those of thewriter.Footnotes:1. ‘A Cypriot Coin of Richard Lion-heart’, NCirc., April 2002, vol. CX, no. 2.2. It is possible that this coin is in the Nicosia Museum.3. A correspondent has recently told the writer that he was shown twospecimens of this type in Larnaca which seems to indicate the existanceof at least four specimens of this type.4. “A New Type of Electrum Trachy of Isaac Comnenus of Cyprus (AD1184-1191)’, NCirc. May 1989, vol. XCVII, no.4. The writer hadproduced a more ‘popular’ version of this article entitled ‘IsaacComnenus: just a little empire on Cyprus’ in the Celator, vol. 3, no. 2,February 1989 and at that time he obviously did not know of the hoarddiscussed in addendum II. All coins illustrated in the NCirc article withexception of no. 1 were in the writer’s collection and, with the exceptioneither no. 3 or 6, were stolen in Los Angeles in late 1989. If any reappearon the market the writer would like to be informed.5. M. F. Hendy, ‘Coinage and Money in the Byzantine Empire, 1081-1261’,Dumbarton Oaks Studies XII, Washington 1969, pp. 136-142. Hendyalso listed a trachy (DO 5) and a tetarteron (DO 10) as ‘uncertainattribution’ (pl. 21, nos. 12-14.).6. M.F. Hendy, ‘Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in Dumbarton OaksCollection and in the Whittemore Collection’, vol. IV, Washington 1999,pp. 354-364.7. There appears to be some evidence that those coins of Heraclius depictingthree standing figure with a Cyprus mint mark may not have been struckin Cyprus since none seem to have been found on the island. P. Pavlougave a paper (unpublished) to the Oriental Numismatic Society severalyears ago which touched upon this matter. In addition, when Cypriotcollectors come to London they tend to buy all the three standing figureCyprus folles they can find which might confirm that these coins are notfound in the island, although since writing this, I now understand theyare.8. In the catalogue and plates in DOC IV these two issues are in the wrongorder since these parts of the catalogue had been completed some yearsbefore the writer published these overstrikes in 1989 (see footnote 4). Inhis late completion of the catalogue Hendy did note this overstrike in thetext.(DOC IV, vol. I, p. 357).9. ‘The Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades, 1191-1374’, Peter W.Edbury, CUP 1991. The first two chapters touch upon the backgroundand earliest years of Lusignan rule.10. Edbury, op. cit., p.29.11. G. Jeffery, ‘Cyprus under an English King in the Twelfth Century’, CyprusGovernment printer, 1926.12. ‘Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium’, vol. I, OUP 1991, p.567.13. D.M. Metcalf, ‘Byzantine Lead Seals from Cyprus’, Cyprus ResearchCentre, Texts and Studies of the History of Cyprus XLVII, Nicosia 2004,p. 37.14. ‘Byzantine Mediaeval Cyprus’, Bank of Cyprus Cultural Foundation,Nicosia, 1998.15. D. M. Metcalf, ‘The White Bezants and Deniers of Cyprus 1192 - 1285’,Texts and Studies of the History of Cyprus XXX, Cyprus Reseach Centre,Nicosia 1998, pp. 11 - 13.16. Edbury, op. cit., pp. 8 and 13.17. The writer acquired the two electrum trachea that he published in 1989in August 1988 from an American Armenian dealer who made frequenttrips to Istanbul. The specimen sold through Baldwins in 1995 wasbought in 1989 in a German auction (often a sign of a Turkish source)while the two most recent electrum trachea, one of each type, sold in theGemini I auction (see footnote 21) also came from a Turkish dealer inMunich.Perhaps we should consider the provenance of the first threespecimens of the first type of electrum trachy (DO 1). The specimen in theBibliotheque in Paris came from the Lambros collection and was acquiredin Cyprus. The pierced specimen in the Goodacre collection (Christiesauction, 24 April 1986, lot 324), was bought by Goodacre from Seaby’s17. in 1942 for 15/- (75 p) and is now in DO. The third specimen, from theWhitting collection, is in Barber Institute in Birmingham. Whittingpurchased it from Baldwins on 23 April 1969. It must have been sold tohim by the writer who has no recollection of doing so and possibly misidentifiedit. The writer may have purchased it at the time or found in oldstock. Since Goodacre bought most of his coins in London it seems likelythat both his and Whittings specimens of DO 1 came from Cyprus whichwas ruled by the British at that time - but did these these coins come fromwhat is now Turkish occupied northern Cyprus?18. M. F. Hendy, ‘Studies in the Byzantine Economy, c. 300-1450, CUP 1985,pl.31, no.13 (unmentioned in the text) and catalogued but not illustratedas DOC IV (8 bis).This coin belonged to the late John J. Slocum of Newport, RhodeIsland, whose coins of Isaac of Cyprus were sold through Sothebys inauction LO 9447 of 14th Oct. 1999, lots 179-186 although this uniquetetarteron was missing. Only its ticket arrived with the collection whichindicated that it had been purchased from <strong>Spink</strong> and Son. It was onlywhen Sothebys received the collection from Slocum’s heirs that it wasdiscovered that a number of coins had been stolen by a domestic servant.The writer thinks it unlikely that Hendy and Slocum were in contact andit may be that the reason that the writer ‘mislaid’ his photograph of thecoin and was unable to illustrate it in either of his 1989 articles whileHendy was able to illustrate it in 1985 was because the writer had sentthe photograph to Hendy by 1985. In the 1970’s and 1980’s the writersent photographs of most of his ‘discoveries’ to Hendy. About 40 coinsillustrated in DOC IV belonged to the writer and are now in theAshmolean Museum. That this particular coin is not illustrated in DOC IVis because the plates were in proof by c. 1980 and any new coinsdiscovered after that date could not be illustrated.19. Hendy suggested that Isaac did not begin to strike coins until he hadrepulsed Isaac II’s attempt to recapture Cyprus in 1187 and that he hadceased issuing coins even before the arrival of Richard I (DOC IV, p. 357).It seems unlikely that so many different types would have been struck inonly four years but if this was the case then Isaac preceded the post-1204Byzantine emperors in changing the design of his coinage annually.20. Four electrum trachea, possibly only four billon trachea and possibly adozen tetartera although it seems possible that more trachea andtetartera from the hoard noted in addendum II might exist in Cypriotcollections. A specimen of DO 8 fetched $1420 as lot 1355 in the wintermail bid sale of NFA of 14 December 1989. This coin is unlikely to havecome from the hoard listed in addendum II and its extremely high pricereflected its rarity at that time when it was obviously considered unique.21. Isaac does not appear personally on his imperial seals which depict St.Theodore (Metcalf, op. cit. pp. 338-339). What significance St. Georgehad for Isaac is uncertain although the saint also appears on thecommonest and apparently earliest of Isaac’s billon trachea (DO 2).22. Two other specimens have appeared in auctions - A.H.Baldwin auction 5,11 Oct. 1995, lot 273 (acquired from a German auction in 1989) andGemini I, 11-12 Jan 2005, lot 516. Gemini was a joint auction ofFreeman and Sear and Harlan J. Berk held at the New York NumismaticConvention. Lot 515 of the Gemini I sale was a specimen of DO 1, bothcoins coming from Turkey.23. ‘Two Rare Byzantine Coins of the Comnenian Dynasty’, NCirc., vol CIX,no. 5, Oct. 2001, no. 2.24. Just as he had completed this article the writer received a photo of yetanother tetarteron which is illustrated as fig. 5 by kind permission of theowner. This coin (illustrated c. x 1.5 actual size) is the same as DO 7except that Christ appears not as a bust but as a half-length figure withright hand raised in benediction and holding the Gospels. Hendy wasunable to tell what Isaac was holding in his left hand from the specimenhe illustrated in DOC IV but other coins indicate that he holds an akakia.It is difficult to tell whether this new coin is merely a variant of DO 7struck from a single die where the engraver had mistaken hisinstructions. A second specimen might solve the problem. If anotherspecimen is struck from different dies or if Isaac holds a globus instead ofan akakia this type must be a separate issue. Although Isaac’s title is notvisible, the fact that the the emperor has looped pendilia should indicatethat this too is an issue of the primary mint.25. These analyses were carried out at Durham University but unfortunatelythe equipment was so new that it not been calibrated and it was notpossible to give exact figures except to say that there were similar smallamounts of silver in both the trachea and tetartera.26. The writer noted that seven specimens of DOC 2 had retrograde legendsand pendilia with single drops. This information certainly came from thewriter’s first informant, since these were features the writer failed to notewhen he acquired the hoard. However, when this article was almostcomplete, the writer found that he still had two trachea of DO 2 and onetetarteron of DO 8 left from the hoard. One of the trachea seems to be oneof these retrograde coins referred to. Both pendilia end in single pellets,the left hand one possibly having a side loop and the right hand one plain.Isaac’s name is not visible but, on the right, the name of St. George isengraved in retrograde letters. The note of a retrograde legend seems torefer only to the letters and does not mean that the names weretransposed.374 NUMISMATIC CIRCULAR

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 37527. The Baldwin list noted five tetarteron of DO 8. The writer had presumedthat he had acquired more since they are so rare that five would havebeen easily saleable and if he did not have more than five why does he stillpossess one? The reason is possibly because this tetarteron and the twocoins of DO 2 which the writer recently found were the coins he sent formetal analysis and mislaid when they were returned. Since Baldwinsmade a note of the hoard and noted a copper trachy (DO 5) rather than atetarteron (DO 10) it seems likely that there was only a single coin of thefirst issue of the secondary mint in the hoard and that it was a trachy.28. In all the years that the writer was a dealer, all the coins of Isaac ofCyprus appearing in London were duplicates sold by Cypriot collectors ontheir visits to the U.K. There was no other original source since thesecoins do not appear to be found outside Cyprus.29. The Turks occupied the north of Cyprus in 1974 and Greek Cypriotcollectors have not been able to acquire coins from this region ever since.A collector who recently visited the north of Cyprus and discreetly askedafter ancient coins found the laws extremely stringent. Does this meanthat the five electrum trachea found since 1988 were found in Turkey?This seems unlikely since there was little contact between the Byzantineempire and Cyprus during Isaac’s reign.30. In the draft of his May 1989 article the writer mentioned another hoardof coins of Isaac which consisted of 75 trachea of DO 2. This hoard wasowned by Mr. J. Slocum, although these coins did not appear in theauction of his collection. They might have been amongst those stolenwhich included his important collection of Urtukid and Danishmendidcoins.A Forgotten Find of Byzantine BillonTrachea of the Twelfth and ThirteenthCenturiesDr. E. LiantaThe writer was recently given the opportunity to examine a hoard of374 Byzantine billon trachea acquired in the London numismatictrade in the 1960’s, and retained since then 1 . Nothing is known,unfortunately, about the coins’ specific geographical provenance. It ispossible, though, that the hoard was discovered in Turkey, sincenothing came out from Bulgaria until the fall of communism in1990. The hoard appears to have been deposited in the 1210’s, andcomprises eleven coin types, all of which have been previouslypublished. Nevertheless, the hoard places new find-evidence onrecord, and adds to our knowledge of the range of coinages that werein circulation in the first quarter of the thirteenth century.The contents of the hoard may be summarized as follows:Bulgarian Imitations (= Direct Copies)1-8. TYPE A (DOC 4, pl. XXVI, no. 1) 8 sp.(3.21g, 2.54g, 2.33g, 2.30g, 2.22g, 2.08g, 1.91g, 1.72g)9-19. TYPE B (DOC 4, pl. XXVI, no. 2) 11 sp.(3.73g, 3.70g, 3.01g, 2.75g, 2.68g, 2.61g, 2.50g, 2.20g, 1.92g,1.76g, 1.42g)20-156. TYPE C (DOC 4, pl. XXVI, no. 3) 137 sp.(5.33g, 4.06g, 4.02g, 3.95g, 3.91g, 3.80g, 3.56 (2)g, 3.54g, 3.52g,3.44g, 3.34 (2)g, 3.32g, 3.31g, 3.30g, 3.24g, 3.23g, 3.19g, 3.18g,3.17g, 3.12g, 3.10g, 3.07g, 3.04g, 3.02g, 2.99g, 2.96g, 2.95g, 2.94g,2.93g, 2.90g, 2.85 (2)g, 2.82g, 2.81g, 2.79g, 2.78 (2)g, 2.77g, 2.75(2)g, 2.73 (2)g, 2.72 (4)g, 2.70 (4)g, 2.69 (2)g, 2.68 (2)g, 2.67 (2)g,2.66 (2)g, 2.65g, 2.64g, 2.61 (3)g, 2.55g, 2.54g, 2.51 (2)g, 2.50g,2.47 (3)g, 2.46 (2)g, 2.43g, 2.42g, 2.41g, 2.38g, 2.37 (2)g, 2.36 (2)g,2.32g, 2.31g, 2.30g, 2.29 (2)g, 2.28 (2)g, 2.26g, 2.25g, 2.24 (3)g,2.22g, 2.19g, 2.18g, 2.17 (3)g, 2.13g, 2.12g, 2.11g, 2.04g, 2.03 (3)g,1.99g, 1.98g, 1.96g, 1.95 (3)g, 1.94g, 1.93 (3)g, 1.91g, 1.90g, 1.88g,1.85g, 1.82g, 1.81 (2)g, 1.73g, 1.72g, 1.71g, 1.70g, 1.68g, 1.63g,1.62 (2)g, 1.53g, 1.44g, 1.36g, 1.23g)Latin Imitations (1204-1261)157-158. CON. LARGE TYPE A(DOC 4, pl. XLVIII, no. 1; S. 2021)2 sp.(2.72g, 2.26g)159-160. CON. LARGE TYPE B(DOC 4, pl. XLIX, no. 2; S. 2022)2 sp.(2.62g, 1.72g)159-161. CON. LARGE TYPE C(DOC 4, pl. XLIX, no. 3; S. 2023)1 sp.(2.19g)162. CON. LARGE TYPE E(DOC 4, pl. XLIX, no. 5; S. 2025)1 sp.(2.47g)163-165. SMALL TYPE A(DOC 4, pl. LII, no. 30; S. 2044)3 sp.(1.73g, 1.54g, 1.44g)116-203. SMALL TYPE G(DOC 4, pl. LIII, no. 36; S. 2050)38 sp.(2.16 (2)g, 2.10g, 2.08g, 2.03g, 1.96g, 1.92 (3)g, 1.88g, 1.87g, 1.82g,1.78g, 1.73g, 1.63 (2)g, 1.61g, 1.60g, 1.58g, 1.55g, 1.51g, 1.47g,1.37g, 1.30 (2)g, 1.27 (2)g, 1.25 (2)g, 1.19 (2)g, 1.16 (2)g, 1.15g,1.10g, 0.92g, 0.82g, 0.78g)Theodore I (1204/5-1222)204-224. NICAEAN TYPE A(DOC 4, pl. XXVII, no. 5; S. 2061)21 sp.(3.52g, 3.22g, 3.17g, 3.06g, 2.83g, 2.81g, 2.79g, 2.74g, 2.41g,2.34g, 2.30g, 2.22g, 2.17g, 2.13g, 2.11g, 2.10g, 1.85g, 1.64g, 1.58g,1.17g, 1.14g)225-267. NICAEAN TYPE B(DOC 4, pl. XXVIII, no. 6; S. 2062)43 sp.(4.15g, 4.01g, 4.00g, 3.97g, 3.75g, 3.73g, 3.60g, 3.52g, 3.50g,3.40g, 3.38g, 3.34g, 3.32g, 3.29g, 3.26g, 3.18g, 3.17g, 3.09g, 3.03g,3.01g, 2.98g, 2.95g, 2.93g, 2.88 (2)g, 2.86g, 2.83 (3)g, 2.81g, 2.79g,2.72g, 2.71g, 2.64g, 2.60 (2)g, 2.56 (2)g, 2.46g, 2.42g, 2.23g, 2.16g,2.10g)Unclean and worn268-374. 107 sp.Other known hoards, which are similar in their range of contentsto this new ‘London 1966’ hoard and likewise terminate withNicaean billon trachea of Theodore I, are the Bulgarian hoards foundin Gurkovo 2 and Ustra 3 , and the Greek hoard discovered in Veroia 4 .As seen from Table 1 (overleaf), the London 1966 hoard containsfar greater quantities of Bulgarian Imitations 5 , which account for156 coins, or 41.71 per cent of the total, than the other comparablehoards. The London 1966 hoard is particularly striking for thenumerical predominance of Bulgarian Imitation Type C, which is thelargest single component of the hoard comprising 137 specimens, or36.63 per cent of the total. Of the identifiable coins, despite theirincomplete striking, five varieties (Var.) of the designs of the loroswaistswere observed (see Fig. 1) 6 .DECEMBER 2005 375

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 376TABLE 1FIGURE 1Over the last thirty years, a number of scholars have debated thedating of the Bulgarian Imitations, and particularly the question ofwhether they were introduced before or after 1204 7 . FollowingTouratsoglou’s original suggestion 8 , the most recent arguments infavour of a post-1204 date were presented by Bendall 9 , andHristovska 10 at the symposium “Coinage in the Balkans, ninth tofourteenth centuries – Forty Years on” held in honour of Prof. D.M.Metcalf in Oxford (1-3 September 2005).GRAPH 1The geographical provenance and composition of the London1966 hoard supports the arguments of Bendall and Hristovska.While 107 specimens remain unidentified, for they were uncleanedand worn, the main body of the London 1966 hoard provides a usefulsample that fixes the date of the Bulgarian Imitations by reference tothe Latin Imitations and the issues of Theodore I. Graph 1 confirmsthe different relative proportions of the Bulgarian Types A, B and C 11 ,which are on weight-standards ranging between c. 2.3g and c. 2.6g.Moreover, it shows that Type C persisted in circulation longer thanthe other Bulgarian imitative types.The age-profile of the London 1966 hoard is thus highlyinteresting. Nevertheless, more finds are still required in order tobring corroboration of the interpretation and dating of the BulgarianImitatives proposed by Touratsoglou and his followers.Footnotes:1. Mr. Simon Bendall recalls seeing and cleaning the majority of the coins in1966.The writer would like to thank Mr. Massimiliano Tursi, who kindly madethe group of coins available for study enabling a record of the contents tobe made.2. Gurkovo hoard, Stara Zagora region. See I. Ǐordanov, Moneti i monetnoobrǔshtenie v srednovekovna Bǔlgariia 1081-1261 (Sofia, 1984), p. 158,no. 56.3. Ustra hoard, 1972, excavations in Ustra fortress. See I. Ǐordanov, Monetii monetno obrǔshtenie v srednovekovna Bǔlgariia 1081-1261 (Sofia, 1984),p. 221, no. 189; CH, 4 (1978), p. 63, no. 197; Ǐ. Iurukova, ‘Monetnitenakhodki, otkriti v Bǔlgariia prez 1971 i 1972 g.’, Archaeologia, 19.1(1977), p. 72.4. Veroia hoard, 1963. See T. Hackens, ‘Un trésor byzantin à São Paulo(monnaies scyphates en bronze provenant de Béroia, Macédoine)’,Dedalo, 1.2 (1965), pp. 13-25; M. Galani-Krikou – Y. Nikolaou –M. Caramessini-Oikonomidou – V. Penna – I. Touratsoglou – I. Tsourti,Corpus of Byzantine Coin Hoards in the Numismatic Museum (Athens,2002), p. 123, no. 116; D.M. Metcalf, Coinage of the Crusades and the LatinEast in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (London, 1995), p. 335, no. 128; I.Touratsoglou, ‘Unpublished Byzantine Hoards of Billon Tracheafrom Greek Macedonia and Thrace’, BSt, 14 (1973), p. 134, n. 2;idem, ‘“Θησαυρόs” άσπρων τραχέων/1983 από την ‘Αρτα’, Αρχ.Δελτ., 36 (1981), pp. 219, 224; C. Morrisson, ‘The Emperor, the Saint,and the City: Coinage and Money in Thessalonike from the Thirteenth tothe Fifteenth Century’, DOP, 57 (2003), p. 197; I. Ǐordanov, Moneti imonetno obrǔshtenie v srednovekovna Bǔlgariia 1081-1261 (Sofia, 1984),p. 152, no. 40.5. This imitative series comprises three types of trachea, which copy thedesigns of the billon coinage of Manuel I’s Fourth Type – Var. C (DOC 4,pl. XV, nos. 13f-h), Isaac II’s Var. A (DOC 4, pl. XXI, nos. 3a-b), andAlexius III’s Var. A (ii) (DOC 4, pl. XXIII, nos. 3b-c) respectively.6. The special fonts used for the loros were first created by the late Prof.Nicholas Oikonomides in 1986, and were subsequently enriched by thelate Glen Rubby and the Publication Department of Dumbarton Oaks(Washington, D.C.). Var. D adds to the varieties from the Peter and Paulhoard published by Metcalf (‘The Peter and Paul Hoard: Bulgarian andLatin Imitative Trachea in the Time of Ivan Asen II’, NC, 13 (1973),pp. 160-161, fig. 2).7. See D.M. Metcalf, Review of: ‘Michael F. Hendy, Catalogue of the ByzantineCoins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection,volume 4, Alexius I to Michael VIII, 1081-1261, parts 1 and 2(Dumbarton Oaks Catalogues, Washington D.C., 1999, pp. xii + 736, 54plates)’, NC, 160 (2000), pp. 398-399; M.F. Hendy, Catalogue of theByzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the WhittemoreCollection, vol. 4 (Washington D.C., 1999), pp. 66-80, 435-443, pl. 26;P. Grierson, Byzantine Coins (London, 1982), pp. 237-238; I. Ǐordanov,‘Bǔlgarsko imitativno monetosechene ot nachaloto na XIII v.’,Numizmatika, 12.3 (1978), pp. 3-18; D.M. Metcalf, ‘The Peter and PaulHoard: Bulgarian and Latin Imitative Trachea in the Time of Ivan AsenII’, NC, 13 (1973), p. 147; idem, ‘Byzantinobulgarica: The SecondBulgarian Empire and the Problem of “Bulgarian Imitative” Tracheabefore and after 1204’, NCirc, 81 (1973), pp. 418-421; idem, ‘The Valueof the Amorgos and Thira Hoards as a Test Case for the Interpretation ofSub-Byzantine Trachea in the Years around 1204’, ΝομισματικάΧρονικά, 8 (1989), pp. 49-54; I. Touratsoglou, ‘The Edessa/1968 Hoardof Billon Trachea’, Αρχ. Δελτ., 28 (1973), pp. 67-69; idem, ‘UnpublishedByzantine Hoards of Billon Trachea from Greece, Macedonia andThrace’, BSt, 14 (1973), p. 140, n. 3; idem, ‘“Θησαuρόs” άσπρωντραχέων/1983 από την ‘Αρτα’, Αρχ. Δελτ., 36 (1981), pp. 222-223, n.32, 33; M. Caramessini-Oikonomidou, ‘Contribution à l’étude de lacirculation des monnaies Byzantines en Grèce au XIII siècle’, in Actes duXVe Congrès international d’études Byzantines, Athènes, Septembre 1976,vol. II, Art et Archéologie (Athens, 1981), pp. 123-124; D. Gaj-Popović,‘Les trésors de monnaies concaves Byzantines en cuivre de la collectiondu Musée National de Beograd’, in Actes du 9ème Congrès International deNumismatique, Berne, Septembre 1979, vol. II, Numismatique du MoyenAge et les Temps Modernes, IAPN, Publication 6 (Louvain-la-Neuve/Luxembourg, 1982), pp. 865-866; V. Penna, ‘Βυζαντινόνόμισμα και λατινικέs απομιμήσεis’, in Πρακτικά ΗμερίδαsΤεχνογνωσία στη λατινοκρατουμενη Ελλάδα, ΓεννάδειοsΒιβλιοθη´κη, Αθήνα, 8 Φεβρουαρίου 1997, (Athens, 1997), pp. 16-17.The writer does not pursue in this short article the controversies that theattribution of the Bulgarian Imitations has raised.8. I. Touratsoglou, ‘The Edessa/1968 Hoard of Billon Trachea’, Αρχ. Δελτ.,28 (1973), pp. 68-69: “…it would be quite reasonable to consider the“Bulgarian” imitatives as the first phase of the newly established Latinempire’s coin production, immediately after 1204.”9. S. Bendall, ‘Some Comments on the “Bulgarian Imitative” Coinage in theLight of a Recent Hoard’ (forthcoming in a special volume devoted to theOxford conference).10. K. Hristovska, ‘“Bulgarian” Imitative Coinage in the Context of Findsfrom the Republic of Macedonia’ (forthcoming in a special volumedevoted to the Oxford conference).11. See also D.M. Metcalf, ‘The Value of the Amorgos and Thira Hoards as aTest Case for the Interpretation of Sub-Byzantine Trachea in the Yearsaround 1204’, Νομισματικά Χρονικά, 8 (1989), p. 53.376 NUMISMATIC CIRCULAR

Dec 05 Editorial 29/11/05 4:27 pm Page 377POSSIBLY THE MOST DESIRABLE OF ALL NUMISMATIC BOOKSFrom the library of Jean Grolier,“The Prince of Bibliophiles”Johann Huttich (c.1480-1544), Imperatorum romanorumlibellus. Una cum imaginibus, ad vivam effigiem expressis.Strasbourg (Wolfgang Köpfel) 1526. In-16 collated as (16 pages),82 leaves, 6 pagesWhile Guillaume Budé’s De asse et partibus eius (Paris 1514) isconsidered to be the first numismatic book, Andrea Fulvio’sIllustrium Imagines (Rome 1517) is the first illustratednumismatic book (probably engraved by Ugo da Carpi). Widelysuccessful, it started a fashion for portrait-books, this one byHuttich (a brief illustrated biography of the Roman emperors)being probably the most famous, and also, possibly, the mostimportant of all. Johann Huttich (c. 1480-1544), a Mainz-bornscholar, archaeologist and numismatist, was also a friend and correspondent of Erasmus. The first edition, also by Köpfel ofStrasbourg, was published in 1525. Its woodcut medallions are often inspired by those of Fulvio, some even copied from him,but in a stronger and more Gothic style. It also improves on Fulvio by continuing the series of Roman rulers up to the thencurrent Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, a meaningful statement during the Protestant Reformation, and probably reflecting agrowing attachment to the nation and separation from the Pope. A new edition was published in 1534 (the first book to attemptillustration of a series of Republican coins), and again in 1550 and 1554 and 1564; although it was translated into German in1526, into Italian and into French, in 1552, the 1525-1526 editions are nevertheless the most famous for “the Huttich”.This book, printed throughout in a fine italic font, contains 263 medallions, 185 of which display portraits, 78 of whichremain blank. These engraved portraits of emperors and their wives are superbly displayed in white on a black background,some of them being attributed to Hans Weiditz (“the Petrarch Master”, c. 1495-1536).This rare second edition is listed in Dekesel, Bibliotheca Nummaria. Bibliography of 16th Century Numismatic Books, London(<strong>Spink</strong>) 1997, # H39 (21 copies listed).This book comes from the library of humanist Jean Grolier (c. 1489-1565), who is renowned as the “Prince of Bibliophiles”,a library that De Thou compared to the one of Gaius Asinius Pollio (i.e. the oldest one in Rome). Born into a wealthy merchantfamily from Lyon, involved in the publication of Budé’s De Asse in 1522 by the printing house of Aldus Manutius in Venice,Grolier purchased in 1532 the office of Treasurer of France, but he was soon to be fined a huge amount, and spent four yearsin prison. Immediately after his release, in 1538, Grolier bought two copies of this book, probably from his binder. His libraryhaving been forcibly sold in 1536, buying books was indeed something he started immediately after being freed, even thoughhe owned just 300 or 400 volumes at his death. In 1884, Charlotte Adams commented that “only such books were included init as were remarkable for their intrinsic literary value and their beauty of form”. After Grolier’s death, his bronze coins (the mostvaluable in the collection) left Paris for Provence, and were about to leave France to be sold in Italy, but King Charles IX heard ofit, blocked them, and purchased them for his collection; they were then pillaged during the League, and were lost to the Nation.The gold and silver coins were not sold until 1675 when they were purchased by the Abbé de Rothelin, whose collection of7,290 coins was then purchased in 1746 by Spanish King Ferdinand VI for 360,000 reales; they are now in Madrid’s MuseoArqueológico Nacional. The books were also kept until 1675. Grolier’s modern fame is especially due to his bibliophilism: hisbooks and leather coin-trays were marked [Io.] Grolierii et Amicorum, i.e. “property of [Jean] Grolier and his friends” - exemplaryproof of the true humanist spirit.This small book (165 x 101 mm) was bound in calf circa 1540 by one of Grolier’s regular binders, the so-called “Fleur de Lisbinder”, with many gilt ornaments, and the inscriptions Ro. Impp. Imagines (“portraits of the Roman emperors”) and Grolierii etAmicorum (“property of Grolier and his friends”). A few other books were bound similarly, such as a 1521 Cicero and a 1521Polybius. As required by Grolier from his bindings, the vellum and paper endleaves were retained. It then became part of thelibraries of Grolier’s contemporary Jean Colin, of Jacques Dorat (ex libris dated 1627),and of Louis Guibert (in the 19th century).This exceptional copy of Huttich, undoubtedly one of the most desirable numismaticbooks ever on the market, is referred to in several books:– Kagan, Cunally & Scher, Numismatics in the age of Grolier. An exhibition at The GrolierClub, New York 2001, pp. 25 & 49– Hobson & Culot, Italian and French 16th century bookbindings, Brussels 1991, # 30– Anthony Hobson, Renaissance Book collecting, Cambridge 1999, pp. 58-59– Austin, “The library of Jean Grolier, a few additions, Festschrift Otto Schäfer, Stuttgart1987, 237-1– Musea nostra, 29DECEMBER 2005 377

Dec 05 Cover 29/11/05 4:34 pm Page 4GK1744GK1754GK1743GK1741GK1758GK1769RM2734GK1770

Dec 05 Cover 29/11/05 4:34 pm Page 1HS2242HS2250MG1542MG1544MG1563MG1576HS2214 HS2217 HS2218 HS2253HS2249HS2259MS6788MS6802 MS6808 MS6830 MS6843MS6846MS6864MS6877MS6886MS6901MS6909MS6913MS6933 MS6938 MS6941 - MS6945-I0208 I0216 I0218 I0238 I0234I0244