Spring 1984 – Issue 31 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

Spring 1984 – Issue 31 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

Spring 1984 – Issue 31 - Stanford Lawyer - Stanford University

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

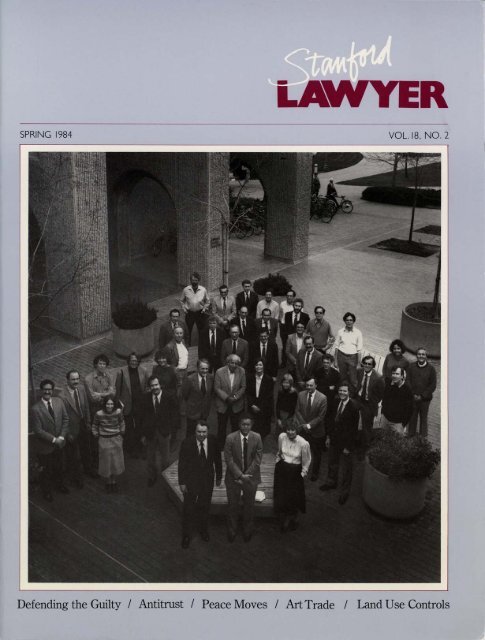

RSPRING <strong>1984</strong>VOL. 18, NO.2Defending the Guilty / Antitrust / Peace Moves / ArtTrade / Land Use Controls

RSPRING <strong>1984</strong>VOL. 18, NO.2Editor: Constance HellyerAssociate Editor:Michele FoyerArt Director:Barbara MendelsohnProduction Artists:Marco Spritzer, Nancy SingerStudent Interns:Emily Brandenfels, LisaHudsonCover photo by Leo HolubOther photo and art credits:page 45.<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> is publishedsemiannually for alumni/aeand friends of <strong>Stanford</strong>Law School. Correspondenceand materials for publicationare welcome and should besent to: Editor, <strong>Stanford</strong><strong>Lawyer</strong>, <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School,Crown Quadrangle, <strong>Stanford</strong>,CA 94305. Copyright <strong>1984</strong> bythe Board of Trustees of theLeland <strong>Stanford</strong> Junior <strong>University</strong>.Reproduction inwhole or in part, without permissionof the publisher, isprohibited.Opinions expressed in bylinedarticles are not necessarilyshared by the editors orby <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School.Page 4FROM THE DEANPage 10FEATURE ARTICLESDefending the GuiltyBarbara A. BabcockA Conversation with William F. Baxterwith Diana DiamondAntitrust in the '80s: The Zealots vs. the WackosThomas J CampbellPage 26AT ISSUEToward an Effective Peace MovementJohn H BartonTrading in Art: Cultural Nationalism vs. InternationalismJohn Henry MerrymanGrowth Controls: Fueling the Mid-PeninsulaHouse Price ExplosionRobert C. EllicksonSCHOOL NEWSFaculty Notes241017222426<strong>31</strong>43ALUMNI/AE NEWSAlumni/ae Weekend 1983Class NotesIn MemoriamAlumni/ae GatheringsComing Events28468486Back CoverLETTERS 88

AJohn Hart Elys you noticed, the current facultygrace this issue's cover(minus a few of us, unfortunately includingthe Dean. That's me above).Instead of boring you with somebrief but repetitive message, Ithought it might be fun to sharewith you-for purposes of comparisonand/or nostalgia - some earlierfaculty group photographs. (CarlSpaeth's deanship was as early aswe were able to go. The facultyphotographs from earlier times thatwe located were of individuals, anddid not picture the faculty as agroup.) Needless to say, we wouldbe interested if anybody has or isaware of any such pictures-as,indeed, we are interested in allpictures reflecting the history of theSchool. D1977Front: Howard R. Williams, ThomasC. Grey, John Henry Merryman,Barbara A. Babcock, J Keith Mann.Middle: J Myron Jacobstein, Wayne G.Barnett, Kenneth E. Scott, David L.Engle.Rear: William F. Baxter, Marc A.Franklin, Byron D. Sher, Charles JMeyers (Dean), Gordon Kendall Scott,Paul Goldstein, and Paul Brest.1974Front row, L to R: Byron D. Sher,Thomas C. Grey, Michael S. Wald,RichardJ Danzig, Mauro Cappelletti,Robert L. RabinSecond row, L to R: Gerald Gunther,Moffatt Hancock, J Myron Jacobstein,Barbara A. Babcock, Kenneth E.Scott, Howard R. Williams, William FBaxter, John Kaplan, William Cohen,Paul Brest, David RosenhanThird row, L to R: William B.Gould, Victor H Li, Robert A. Girard,John H Barton, John Henry Merryman,Jack H Friedenthal, Thomas Ehrlich(Dean), Richard S. Markovits, Marc A.Franklin, Charles J Meyers, J KeithMann, Lawrence M Friedman, WilliamD. Warren1967Front row, L to R: Charles JMeyers, J Myron Jacobstein, Robert A.Girard, Bayless Manning (Dean), JohnHenry Merryman, Howard R. Williams,Joseph T SneedBack row, L to R: Byron D. Sher,Lawrence M Friedman, John Kaplan,Jack H Friedenthal, Douglas R. Ayer,William F Baxter, Gordon KendallScott, John R. McDonough, MoffattHancock, Marc A. Franklin, Dale S.Collinson, Wayne G. Barnett1961Front row, L to R: Harry John Rathbun,Marion Rice Kirkwood, Carl BernhardtSpaeth (Dean), James EmmetBrenner, Joseph Walter BinghamSecond row, L to R: John HenryMerryman, Moffatt Hancock, John R.McDonough, Gordon Kendall Scott, JohnBingham Hurlbut, Lowell Turrentine,Samuel David Thurman, David Freeman(Assistant Dean)Third row, L to R: Edwin M Zimmerman,John H DeMoully, Richard A.Wasserstrom, Robert A. Girard, LawrenceForrest Ebb, Byron D. Sher,Herbert L. Packer, William F Baxter,Philip H Wile2<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> 3

IIIby Barbara Allen BabcockProfessor ofLawBoW can you defend a personyou know is guilty?I have answered that questionhundreds of times, but never tomy inquirer's satisfaction, andtherefore never to my own. Inrecent years, I have more or lessgiven up-abandoning the highflownexplanations of my youth, andresorting to a rather peevish "Well,it's not for everybody. Criminal defensework takes a peculiar mindset,heart-set, soul-set."While I still believe this, the mindset,at least, might be more accessiblethrough a better effort at explanation.My perspective is that of a practitioneras well as an academic.From 1964 to 1972 I was a criminaldefense lawyer, first with the firmof Edward Bennett Williams inWashington, D.C., and then as apublic defender. I regard thoseyears as immensely satisfying.However, this experience alsogave me ample opportunity toobserve the pathology of the system,which I've continued to followas a teacher of criminal procedure.I've also read many dozens of booksby and about criminal d~fenselawyers, which largely mirror myown experiences.With this background - and withmy present security in a good academicjob - I feel able to discuss,without the usual hand wringing orwashing, what it is like to defendthe guilty.4<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

What Is the Question?Most people do not mean to questiondefending those accused ofcomputer crime, embezzlement, ortax evasion. Usually the inquirer isasking, How can you defend arobber, a rapist, a murderer?1In its components, the question isfirst, How can you when you knowor suspect that if you are successful,he will be free to commit othermurders, rapes, and robberies?Second, how can you defend aguilty man? You, with your fancylaw degree, your nice clothes, yourpleasing manner.Third, how can you defend- i.e.move to suppress the evidence ofclear guilt found on his person,break down on cross-examinationan honest but confused witness,subject a rape victim to a psychiatricexamination, or reveal that aneyewitness to a crime has a historyof mental illness?What Are the Answers?The garbage collector's reason. Yes, itis dirty work, but someone must doit. We cannot have a functioningadversary system without a partisanfor both sides. The defensecounsel's job is no different and thework no more despicable than thatof the lawyer in a civil case, whoarranges, argues, and even orientsthe facts with only the client's ,interest in mind.This answer may be elegantlyaugmented by a civil libertariandiscussion of the Sixth Amendmentand the ideal of the adversarysystem as our chosen mode for,ascertaining truth.The civil libertarian also tells usthat the criminally accused are therepresentatives of us all. Whentheir rights are eroded, the camel'snose is under and the tent may collapseon anyone. In protecting theconstitutional rights of the accused,we are only protecting ourselves.The legalistic or positivist's reason.Truth cannot be known. Facts areindeterminate, contingent and, incriminal cases, often evanescent. Afinding of guilt is not necessarily thetruth, but rather a legal conclusionarrived at after the role of the defenselawyer has been fully played.The sophist would add that it isnot the duty of the defense lawyerto act as fact finder. Were she tohandle a case according to her ownassessment of guilt or innocence,she would be in the role of judgerather than advocate.Finally, there is a difference betweenlegal and moral guilt: thedefense lawyer should not let hisapprehension of moral guilt interferewith his analysis of legal guilt.The example usually given is of theperson accused of murder who canrespond with self defense. The accusedmay be morally guilty but notlegally culpable.The odds-maker chimes in that itis better that ten guilty people gofree than that one innocent be convicted.The political activist's reason. Mostpeople who commit crimes arethemselves the victims of horribleinjustice. This is true generally becausemost of those accused of rape,robbery, and murder are oppressedminorities. It is often also true in theimmediate case, because the accusedhas been battered and mistreatedin the process of arrest andinvestigation. Moreover, what willhappen to the person accused ofserious crime if he is imprisoned is,in many instances, worse than anythinghe has done. Helping to preventthe imprisonment of the poor,the outcast, and minorities inshameful conditions is good work.The social worker's reason. This isclosely akin to the political activist'sreason, with some difference in emphasis.Those accused of crime, asthe most visible representatives ofthe disadvantaged underclass inAmerica, will actually be helped byhaving a defender, no matter whatthe outcome of their case. Beingtreated as a real person in our society(almost by definition, one whohas a lawyer is a real person) andaccorded the full panoply of rightsand measure of concern a lawyeraffords can enable a step towardrehabilitation. And because theaccused comes from a community,the beneficial effect of giving himhis due will spread to his friends andrelatives, decreasing their angerand alienation.To this might be added thehumanitarian's reason: the criminallyaccused are men and women ingreat need, and it is part of one'sduty to fellow creatures to come totheir aid.The egotist's reason. Defendingcriminal cases is more interestingthan the routine and repetitive workthat most lawyers do, even thoseengaged in what passes in civil practicefor litigation. The heated factsof crimes provide voyeuristic excitement.Actual court appearances,even jury trials, come earlierand more often in one's career thancould be expected in any other areaof the law.And winning-ah, winning-hasgreat significance because the cardsare stacked for the prosecutor. Towin as an underdog, and to winwhen the victory is clear (there is noappeal from a not-guilty verdict) issweet.My Own ReasonMy reason for finding criminaldefense work rewarding is an amalgamin about equal parts of thesocial worker's and the egotist'sreason.I once represented a womanlet'scall her Geraldine-who wasaccused under a draconian federaldrug law of her third offense forpossessing heroin. Under this law(since repealed) the first convictioncarried a mandatory sentence offive years with no possibility ofprobation or parole. The secondconviction carried a penalty of ten6<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

not measurable, I think that Geraldine'sfriends and relatives who testifiedand talked with me wereimpressed by the fact that she had a"real" lawyer provided by thesystem.But in the last analysis, Geraldinewas right. The case became mycase, not hers. And what I likedmost was the unalloyed pleasure ofthe sound of "Not Guilty." There arefew unalloyed joys in life.The lawyer's discipline requires,however, that we do more than respondto the immediate question.We should also consider whether, infact, the right question is beingasked.years with no probation and noparole. The third conviction carrieda sentence of twenty years on thesame terms.She was 42 years old. During thefew years of her adult life when notincarcerated by the state, she hadbeen imprisoned in heroin addictionof the most dreadful sort. She wasblack, poor, and ugly-and therewas no apparent defense to thecharge. But even for one as bereft asshe, the general practice was tomitigate the harshness of the law byallowing a guilty plea to a drugcharge under local law, which didnot carry the mandatory penalties.In this case, however, the prosecutorrefused the usual plea.Casting about for a defense, I senther for a mental examination. Thedoctors at the public hospitalreported that she had a mentaldisease: "inadequate personality."When I inquired about the symptomsof this illness, one said: "Well,she is just the most inadequateperson I've ever seen." But there itwas - at least a defense - a diseaseor defect listed in the diagnosticmanual of that day.At the trial I was fairly chokingwith rage and righteousness. I triedto paint a picture of the impoverishmentand hopelessness of her life,through lay witnesses and the doctors(who were a little on the inadequateside themselves). The prosecutorand I came close to blows. Atone point, he told the judge hecouldn't continue because I hadthreatened him (which I had -withreferral to the disciplinary committeeif he continued what I thoughtwas unfair questioning).Geraldine observed the sevendays of trial with only mild interest,but when after many hours of deliberationthe jury returned a verdictof Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity,she burst into tears. Throwing herarms around me, she said: "I'm sohappy for you."Embodied in the Geraldine story,which has many other parts butwhich is close to true as I've writtenit, are my answers to the question.By direct application of my skills,I saved a woman from spending therest of her adult life in prison. Inconstructing her defense, I becameintimate with a life as different frommy own as could be imagined, and Ilearned from that. In ways that areIs the Question Right?The persistence and insistence ofthe question - How can you defendthe guilty? - is based on the image ofthe defense lawyer using daringcourtroom skills and legal technicalitiesto free a homicidal maniac.Yet this is a fantasy almost neverrealized.The vast majority of thoseaccused of crime plead guilty-insome jurisdictions as many as 90percent of those charged. Nowhereis the guilty plea rate less than 60percent.In one rough sense this may appearto be a fair result, since mostdefendants are guilty of somethingalong the lines of the accusation.Yet many, in some places most, ofthose who plead guilty do so withouttheir lawyers', or anyone else's,thinking very seriously about possibledefenses or extenuating circumstances.Rather than the popular myth ofan adversary system designed toproduce individuated findings ofguilt while protecting preciousrights, we have a bureaucraticguilty-plea mill that grinds all alike.Overburdened defense lawyerswithout investigation or preparationarrange for the going_rates oncases and trade one off against theothers.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>7

The appropriate question formany defense lawyers is, then, Howcan you participate in such aprocess? or even Why don't youdefend the guilty?The realities of a criminal justicesystem in which few are actually defendedseldom surface in print. ButLife magazine once followed anexperienced public defender in hisdaily rounds in New York City. Thedefender entered a crowded cellblock on the day of trial to discuss aproposed deal with a client he hadnever seen before. Highlights of theconversation between Erdmann(the lawyer) and Santiago (the client)were recorded:"If you didn't do anything wrong,"Erdmann says, "then there's nopoint even discussing this. You'll goto trial."Santiago nods desperately. "I ain'tdone nothing! I was asleep! I neverbeen in trouble before." (This is thefirst time, since his initial interviewwith a law student seven monthsago, that he has had a chance to tellhis story to a lawyer, and he isfrantic to get it all out. Erdmanncannot stop the torrent, and now hedoes not try.) "I been here tenmonths. I don't see no lawyer ornothing. I ain't had a shower in twomonths. We locked up 24 hours aday. I got no shave, no hot food. Iain't never been like this before. Ican't stand it. I'm going to kill myself.I got to get out. I ain't - "Now Erdmann interrupts, icilycalm. "Well, it's very simple. Eitheryou're guilty or you're not. If you'reguilty of anything, you can take theplea and they'll give you a year; and,under the circumstances, that's avery good plea, and you ought totake it. If you're not guilty, you haveto go to trial."". . . I'm innocent. I didn't donothing. But I got to get out of here.I got to-""Well, if you did do anything andyou are a little guilty, they'll giveyou time served and you'll walk.""I'll take the plea. But I didn't donothing.""No one's going to let you take theIplea if you aren't guilty.""But I didn't do nothing.""Then you'll have to stay in and goto trial.""When will that be?""In a couple of months. Maybelonger."Santiago has a grip on the bars."You mean if I'm guilty, I get outtoday?""Yes.""But if I'm innocent, I got to stayIn.. ?""That's right."2The wrong question is asked andnobody really cares, because mostof those accused of crime are poorand often are minorities. A"we/they" mentality allows theshameful discontinuity between acriminal justice system describedon paper and reality.Yet unlike other sores on the bodypolitic that arise from fear andprejudice, the breakdown of thecriminal justice system is a tractableproblem -once we resolve tosolve it. There simply should bemore lawyers, both public defendersand the regular litigating bar,doing criminal defense work in thesame way and with the same expenditureof resources as other legalwork.If there were a large base oflawyers willing to represent the accused,the question of how onedefends the guilty would be subsumedin the larger one of whatlawyers' work is about. And this iswhere the question belongs.There is really nothing differentabout the ethical dilemmas or theamoral stance toward society of thelawyer in a civil case representing a"bad" person- even, or especially,in corporate form - than the lawyerrepresenting someone guilty of acrime.It is true that the facts of criminalcases are heated and that the stakesare high, but the very same ethicalpressures exist in civil cases to winby shading the facts, crossing theline in witness preparation, and destroyingor creating evidence.Perhaps we should shift the focusof lawyers' work from its traditionalunmitigated devotion to the client'sinterest. But until that is done, thedefense of the guilty should be regardedin the same way as the representationof the "bad."To inspire more lawyers to enterthe lists, let us finally turn to anexemplary life - in the mode of nineteenthcentury biographies of saintsand statesmen, presented for pedagogiceffect. In all of the writing byand about criminal defense lawyers,8<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

only one is universally recognizedas being exemplary - ClarenceDarrow.Darrow lived from 1857 until1938. Most of the things that defenselawyers dread happened tohim: notably, indictment for obstructionof justice in a case where itwas said that he arranged to bribe apotential juror; public obloquy forand misunderstanding of his representationof Leopold and Loeb; afrequent cloud over all of hisactivities because he representedthe despised.He had the characteristic criminaldefense lawyer's view of defendingthe guilty as exemplified in a conversationwith a friend who askedhim, some years after an acquittal ina famous case, whether the accusedhad actually done it. Darrow said: "Idon't know; I never asked him."3One of his law partners said, "Hewould defend anyone who was introuble. Though his motivationswere different, he sometimes usedthe same methods as cheap criminallawyers."4Yet Darrow comes to us from thepages of the not-so-distant past as amythic figure. This has not happenedsolely because of the amazingoratorical talent that was the markof his practice. The exceedinglykind judgment of history is rather aresult of his ability to convey directlyto juries and judges thehumanist values that compelled himto defend the guilty.In virtually all of his cases, hespoke much more about the societalconditions that had produced thecrime, the defendant as an individual,and the philosophical difficultyof distinguishing right fromwrong, particularly for historicalpurposes, than ever he addressedthe facts of the case or the particularsof the defense.It is interesting that virtually noneof Darrow's famous summationswould be considered proper in anycourtroom today. There is clearlyan appeal to the prejudices, passions,and sympathy of the jury thatviolates codes of professional re-sponsibility, as well as an expressionof personal opinion and beliefthat steps over the line of acceptedpractice.Yet the way Clarence Darrowlooked at defending - always in aperspective larger than the individualand the facts of the crime - isstill with us. We're not allowed tosay the things he said so eloquentlyand explicitly. But the fact finder,be it judge or jury, on a guilty plea ora trial, sees and senses what Darrowsaid when a defense lawyer trulyrepresents his client.Among the defense bar todaythere are hundreds of lesserDarrows, giving partial and impliciteXpression to what he could moreopenly state: that the causes ofcrime are unknown, perhaps unknowable,and that, in the end, weall share a common humanity withthe accused.DFootnotes1. In recent years, however, as whitecollarcrime has increased in both amountand sophistication, liberal critics of thecriminal justice system have begun to raisethe question in the context of rich and powerfuldefendants and the way in which theiralmost unlimited legal resources twistresults.2. Mills, ]. "I have nothing to do withJustice," Life, March 12, 1971, pp. 55-68.3. Stone, 1., Clarence Darrow for theDefense (1941), p. 254.4. Id. at p. 355.5. Darrow, C., The Story ofMy Life (1932),pp.75-6.Art CreditsEngravings by William Hogarth (16971764). Pp. 1-2: The Rake's Progress (SceneVI!), "In the Fleet." P. 5: The Industrious Apprentice,"Alderman of London: Idle OneBrought Before Him & Impeach'd by His Accomplice."P. 6: Cruelty (Third Stage),"Cruelty in Perfection." Reproduced fromheliographs in The Works of William Hogarth,James R. Osgood & Co. (Boston, 1876).Our thanks to the Palo Alto Public Libraryfor the loan of this fine volume.Photograph of Clarence Darrow by NickolasMuray (1892-1965). From the collection ofthe International Museum of Photography atGeorge Eastman House, Rochester, N. Y.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>9

Aonversation withilliam BaxterIt must be a dramatic change to have beeninvolved in Washington, D.C., at what, Imust assume, was a very .hectic pace, andthen come back to <strong>Stanford</strong> Law School, whichcertainly has a different flow to it.Yes, it's an enormous cultural shock.You have been here since the '50s, haven't you?Oh, I've been here forever. I graduated from <strong>Stanford</strong>Law School in 1956, but I began myundergraduate workin 1947. You are right, though- I am still floating on anadrenaline cloud. I find myself waking up at four or fourthirtyin the morning, saying "There must be· some workaround here that needs doing."I have always been involved, though, in an active consultingpractice, along with teaching, and I will do thatagain. That will be my salvation, and I will expend all theadrenaline I need.Why did you decide to go to Washington?Oh, the particular post that they offered me is sort ofthe mecca job of my specialty. It's the job that everybodywho practices antitrust or regulatory law would like tohave. For me, in particular, since for the past twentyyears I had been teaching that they had large parts of itall wrong, there was an unusually strong obligationeither to put up or shut up. I wanted to see how much of itI could change, and I changed a fair amount of it.10<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

Some say you made a contribution that willaffect antitrust law for at least the next twentyyears.It's still very controversial.Any regrets?No major ones. In retrospect you can always see howyou could have done this a little better, or "Oh, I shouldhave said this." But all in all, I am reasonably contentwith the way it played out.Why did you resign?Tired. And because next year is going to be a highlypolitical year. It's hard enough to do things that are rightbut politically unpopular the first three years of anadministration; it may become impossible the fourthyear.Didyou resign as a favor to Reaganoras a favorto yourself?I did it as a favor to myself. I didn't want to be in thatpolitical crossfire all year.Did you feel that some of the decisions youmade-most notably the AT&T decisionwouldhave had some negative impact on theupcoming election?Oh, I don't think so. The reorganization is so complicatedthat only a handful of people really understand it;people who do understand it think it's a very positivestep. There's a certain amount of misunderstandingabout its causing rate increases, which is totally wrong.But I don't think it will be a significant political factor oneway or the other.Did you get a different viewofWashington thanyou had from here?A little. No major change of viewpoint. More confidencein some points of view; more sharpness.Is it easy to accomplish things or did you find itmore difficult than you thought to get a programor proposal across?It depends whether or not accomplishing somethingrequires the cooperation of the Congress. If accomplishingsomething does, then it is extremely difficult to getanything done-virtually impossible. If you don't needthe cooperation of the Congress, then it can be done.Then would you saythat Reagan maybehavingsome problems accomplishing his original programsbecause of the Congress?Oh sure. Congress as an institution is a disaster.What would you do then? We can't change itunless we change the Constitution.Well, that's right. And that's a very serious problem. Itnever really worked well. It worked tolerably well aslong as we had the seniority system and responsibleparty leadership. But with the current destruction ofseniority and total lack of party authority, there are 535little fiefdoms back there. No one has any idea whatanyone else is doing. Everybody looks for his own set ofheadlines-a very bad situation. And I don't see anyobvious solution.There are ways the Constitution could bechanged.We could somehow more closely approximate a parliamentarysystem. We could have the entire House electedonce every four years-the same year as the president.Or we could have the president elected once every sixyears and get the House in the same six-year cycle,similar to the Senate.But what has happened is that they have created a subcommitteefor every member so that every member hasits own little subcommittee and has its own staff. Whenthe hearings go on, more often than not there's only thesubcommittee chairman at the hearings, and no one elsein Congress really cares.What do you plan to do here at <strong>Stanford</strong>?Go back to consulting, teaching, and writing. I'velearned a lot about government institutions and a littlebit more about antitrust law and regulatory functions. Ithink I have some new things I want to write about.I read that one of the reasons you left is because,you said, that although you had beeninvolved with antitrust law in a most intimateway the last three years, you have lost track asa lawyer.Yes. I just didn't have time to read the cases, theeconomic literature, the finance literature. You consumethe human capital with which you go to Washington andhave very little opportunity to restock it while there.Did you enjoy working in and within theReagan administration?Oh sure. I was quite properly regarded as a specialist.No one called me in to ask me what I thought the budgetdeficit should be. On the other hand, I was regarded as aspecialist who had a lot more knowledge and understandingthan most people in the administration onmicroeconomic and regulatory problems. So I did workwith other people on a variety of problems.You probably will be most remembered foryour decisions on the antitrust suit againstIBM and the divestiture of AT&T. Do youregret either decision?Oh heavens, no.12<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

Are you proud of them?Sure.Which one was harder to arrive at-eitheranalytically or politically?Well, IBM was much more difficult to do the rightthing from a political standpoint, because it's perfectlyobvious that there was going to be enormous criticism.But I guess what I didn't foresee was that it wouldtouch offa heroic effort to dig up some fanciful conflictof interest or something-that it would acquire the levelof personal character assassination as it did at times. Itwas perfectly obvious that it was going to be intentionallycriticized by some. It also was fairly clear inadvance that AT&T was not going to be subject to agreat deal of criticism, and it wasn't. Indeed, you cameofflooking like a hero. Here you negotiated the biggestdivestiture in history. The litmus-paper loudmouthshad a great deal of difficulty criticizing that because itlooked like the government had won.The difficulty with AT&T was the enormous complexityof the problem and acquiring sufficient confidencethat you were insisting on the right language inthe consent decree. Essentially, are we fracturing thiscompany along the right lines? Was it going to becommercially viable? Those were the difficulties withAT&T-the analytical difficulties, the comprehensiondifficulties; a command of an enormous body ofcomplex technical and industrial data was necessary.IBM involved some of that. A great deal of studywent into reaching the conclusion that the government,in effect, after 13 years of wheel-spinning, had notbegun to prove violation of Section 2 of the ShermanAct-the anti-monopolization section.Now that January 1 has arrived, the effect ofthe AT&T break-up will be felt more keenly.Rumor is that telephone rates will double,triple, all across the country.I think that the reorganization will be totally transparentto 99 percent of the population. About the onlydifference will be that they will have to make a decisionwhether they want to buy the instrument they are nowleasing; and if they want a different type of instrument,they will have to go to the store and buy it - as theywould any other appliance. Apart from those twothings, no one is going to notice.My understanding is that local rates areprobably going to double and that longdistancerates may come down.In the first place, if local rates go up - and we can talkabout that-it will have nothing to do with the divestiture.The divestiture is not going to make any rates goup, down, or sideways. It has no effect whatsoever.Weren't long-distance rates subsidizing localrates?Yes, and they can go right on subsidizing local rates.The divestiture doesn't keep them from subsidizinglocal rates.The fact is that there were a lot of forces at work thatwill continue to be at work. Larger and larger portionsof the telephone industry will become competitive, andcompetition drives cross-subsidies out of the system.We may indeed decide-we should indeed decide-tostop subsidizing local service with a tax on longdistance,.which is what we were doing, but it hasnothing to do with the divestiture as such.Similarly, local rates will go up because historicallythe regulators have insisted that those kinds of equipmentbe treated as having useful lives of 30 years anddepreciated very slowly, although that equipmentshould have been depreciated over a period of 7 to 10years.In a regulated context, that has two consequences.First of all, it keeps today's rates lower, because youdon't have to pay as much depreciation. But secondly,it makes tomorrow's rate base bigger, because whathas not been written offin depreciation goes into tomorrow'srate base.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>13

This is typical political behavior by politicians whohave a time frame that never extends beyond the nextelection. They solve the problem by keeping today'srates low and letting someone else worry about the factthat you are pushing forward in time this enormousbulging rate base. And because the telephone companyhas to be allowed to earn a reasonable rate of return onthis ever-fattening rate base, eventually it has to beamortized.The FCC, under the new leadership, has recognizedthis and has required depreciation rates be made somewhatmore reasonable. And the consequence of that isthat we are going to have to be eating our way into thismountain of unamortized costs that the state regulatorshave pushed out in front of us. And that, too, will makerates tend to rise, although, again, it has nothing to dowith the divestiture.So, in short, I would say something along the followinglines. The costs, as opposed to rates-the costs oftelephone service will fall, and continue to fall in theyears ahead.The divestiture, by greatly intensifying competitionin long-distance services and a number of other services,will tend to cause costs to fall more rapidly thanthey would have fallen otherwise. Certainly the cost 'Ofcustomer premises equipment will fall very dramaticallywith competition. We have every reason to expectthat switching equipment and other kinds of equipmentwill fall similarly.Rates, as opposed to costs, are affected by accountingconventions, involving such things as cross-subsidiesand depreciation. And for some of these accountingreasons, what has been kept artificially low before islikely to move back to a more economically realisticlevel.The primary thing that has been kept artificially lowbefore are local residential rates. So local residentialrates will be subject to two influences: they will besubject to the influence of falling real costs, but theyalso will be subject to the influence of more realisticrate-making. Which of those will dominate is notentirely obvious, although I think that even on aninflation-corrected basis, local rates will probably risefor a few years while we go through these correctiveprocesses, and then, after four, five or six years, theywill probably begin falling in real terms as the cost decreasesbecome the dominant factor.How much will that increase the rates? They are notgoing to double or quadruple or any of the silly thingsthat have been said. They might increase as little as 25or 30 percent. They might increase as much as 50 or 60percent. Those are the realistic numbers.You have said the AT&T divestiture favorsconsumers, but in a sense it's the business consumer,not the residential consumer that isfavored.No. It doesn't do people any good to have their businessespay their phone bills for them. The phonesystem works less efficiently because of these crazypricing features being forced into it. And you pay yourreal phone bill every time you buy a loaf of bread or ablouse at the store. It simply forces up the costs of thebusinesses that sell you the things that you buy.I have mixed reactions as a consumer. We hada .system that in some ways was working verynIcely. I could call almost any place in thecountry, or even the world, in seconds. Mytelephone usually works, the service is good.'Ye have taken something that is very operatIveand reasonably cheap and chaQged it. Andfor the next four to five years there is thatunknown out there.That's right. Every change can be greeted with apprehension.Will it ultimately be better for me-the residentialcustomer?Oh, sure. On average, I haven't the slightest doubtabout it.Everyone's phone costs are going to fall. And, onaverage, rates will follow costs. The problem is buriedin the "on average" statement, because some peoplewill benefit more than others. And because of theseaccounting distortions that we have had in the past,there will have to be, or there will undoubtedly be, acorrection period.On the other hand, we can go right on making thesemistakes if we are determined to do so. Divestituredoesn't make it impossible. Indeed, when I designedthe divestiture decree, I carefully built into the decree amechanism that permitted the regulators to go onmaking all the old mistakes, if they wanted to make theold mistakes. They have to make them somewhat moreout in the open now, but the means for perpetuatingthose mistakes were carefully built into the consentdecree.What has happened is that the regulators have takenadvantage of the fact of the consent decree, a bigpolitical maneuver. They have thrown up their handsand said, this strange, mystical force way off inWashington, D.C., over which we have no control, isgoing to make us correct these mistakes. So they aresort of using it as a screen, a political excuse, behindwhich to hide while they change some of these things.Now, that doesn't particularly bother me. I am delightedto see them changing these things around,because there were economic errors, and it would bebetter offif they changed. I don't much care if they arepointing to the divestiture as the cause of these things.But no one with the slightest comprehension of whatthe system is about should be deceived.14<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

Turning to another area, you took a fairlystrong position that manufacturers can forbidtheir distributors to have any price competition.How do you feel about that?The position I have taken is that manufacturersshould be able to reach agreement with their distributorsas to how those products should be distributed.The U.S. Supreme Court holds a totally differentview.It did in 1962, which I guess was the last time theyspoke about it .. So maybe we will find out. I just argueda case before the U.S. Supreme Court that may causethem to address themselves to that issue again.It is perfectly clear a manufacturer cannot go to aretail store and say, "Here is my product, I insist thatyou buy it. And I insist that you market it the way I wantyou to market it." The manufacturer can proceed onlyby seeking out retailers or wholesalers, dependingupon the configuration of the distribution system, andreaching agreement with them- offering them a satisfactoryprice for the merchandise and entering intoessentially a consensual relationship.But the retailer's situation is quite different. At thepresent time, the retailer can tell the manufacturer,whether the manufacturer likes it or not, that he isgoing to distribute goods the way he wants to. Andthere's no particular reason to think that that's asensible way to run a world; indeed, it's fairly clear, Ithink, that with respect to some kinds of products atleast, unless the manufacturer can control the characteristicsof his distribution system, that the productcan't successfully be developed and marketed. This isespecially true with respect to technically complexconsumer goods, usually relatively new products.Like Apple Computer?Like Apple Computer. Photographic equipment. Ordigital turntables.No one is going to spend two-thousand dollars on adigital turntable unless there is someone at the storewho can explain exactly why it works the way it works,why it is superior to other turntables. And that requiresa retailer to invest a lot of money in inventory to keep allthis expensive stuff around - and that he have technicallytrained salespeople there on the floor who will bestanding around on one foot or the other most of theday, but who will be there to answer questions whenpeople come in.But if people can go into the store, take advantage ofthe display inventory, cross-examine the technicallytrained salespeople for an hour-and-a-half, and then,when they finally understand what this equipment cando for them, walk out, say, "Thank you very much, andI am going to get it from the discount store" -why, youcannot sustain the distribution system under those circumstances.You never find a discount store wanting to market abrand-new product. They are only interested in aproduct after someone else has built a reputationaround it.What's wrong with that?No one will invest in building a reputation for aproduct if the product is going to be rendered unprofitablethe day they complete the process. So the incentiveto develop and attempt to market complex new productsof that kind will be greatly weakened under thosecircumstances.Well, I can see that argument in some ways. Itprotects Apple or whoever is manufacturing aproduct. But it disallows the consumer tosomehow enjoy the competition that occursbetween distributors.No. The consumer enjoys the competition betweenApple and IBM, between Apple and DEC, betweenApple and Control Data, Apple and Adam-there's allthe competition in the world out there. The only competitionthat is eliminated is the competition betweentwo different retailers selling Apple. And even there itis not eliminated unless the manufacturer wants toeliminate it.And why would the manufacturer want to eliminatecompetition between two different retailers? By andlarge, he would like his product sold by his retailers atthe lowest possible cost. The manufacturer has everyincentive in the world to do business with discounters.The notion that discounters would somehow be cut off<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>15

en masse is, again, a very simple, childish piece ofpolitical nonsense.There is only one circumstance in which a manufacturerwants to suppress price competition between hisdealers. That is where one of the dealers is providingthe kind of sales and service that he thinks is essentialto the success of his product, and where the other isrendering that activity unprofitable for the first dealerby not incurring the expenses of providing the servicesand by charging the low prices that go along with notproviding those services. Now he is destabilizing thesystem, and that the manufacturer wants to stop.Some have said that you singularly favor business;others label you "too soft on business."Are these accurate?They don't mean anything. How do I know what theyare talking about?Well, I presume they mean whatthe consumergroups calla "let-the-consumer-be-damned"attitude.There are a lot of things where there is not a worldmarket. Local motion picture exhibition: a theater inNew York City is not in competition with, say, the NewVarsity Theater in Palo Alto. So the geographic scopeof markets varies enormously depending upon theproduct or service you are talking about.Why is the perception so different?Because people don't understand what they are talkingabout.Give me an example where people are wrong.The consumer groups-the Consumer Federation ofAmerica, for example - came out with a big bla~t aboutresale price maintenance that was obviously wrItten bysomeone who had never taken Econ 101, and it was justabsolute political gibberish.If you have been accused of being too soft onbusiness, you also have been complimentedonhavingthe U.S. assumeaninternationalglobalapproach to the marketplace. Isthataccurate?Well, not terribly accurate.In some products there is a world market. Certainlyin specialty steel, computer software, robotics andunrefined petroleum. And where there is a world market,of course you have to recognize that there's a worldmarket.There are a lot of things where there is not a worldmarket. Local motion picture exhibition: a theater atNew York City is not in competition with, say, the NewVarsity Theater in Palo Alto. So the geographic scopeof markets varies enormously depending upon theproduct or service you are talking about.Where do automobiles fit into your marketclassification?Well, there would be a world market in automobiles ifthe government hadn't screwed the market up bypounding on the Japanese. For example, we got theJapanese to restrict their shipments of automobiles tothe United States, so that, as an economic matter, theJapanese are no longer in the market. Notwithstanding,they still have a 20 percent market share.I realize that's a statement you will find puzzling. Butthe critical question one is asking when one asks if theyare really in the market is whether they can expandtheir supply in response to the price increase. And sincethe number of Japanese automobiles is fixed, theJapanese cannot expand their supply of automobiles inresponse to a price increase, and therefore theyexercise no disciplinary influence whatsoever on theprice of American automobiles. We have taken themcompletely out of the marketplace.Similarly in carbon steel, we have taken most of theEuropean suppliers completely out of the marketplace.And there are other respects in which we and manyother countries have closed their markets.So the question as to whether something is a localmarket or a national or international market is simply aquestion of fact that varies from case to case.Now, I said that loud and long-perhaps in ways thatsome people understood for the first time in their lives.On the other hand, there was nothing radical about thatproposition. Anyone who is semiliterate in economicswould have made that statement fifty years ago. Somegave me much too much credit on that particular point.Perhaps it was saying the right thing at theright time in the right place.Okay, maybe all those things.There is one more thing I would like to say. AlthoughI am pleased with the disposition of the two big cases, Idon't regard those cases as the most important thing Iwas able to accomplish, to the extent I was able toaccomplish anything.But probably the most important and the most longlastingthing is that I think that I really got most of the400 lawyers in the Antitrust Division to realize in amuch more focused and articulate way that the onlydisciplined context for thinking about or talking aboutthe public interest is in terms of consumer welfare andeconomic analysis.They didn't all agree with the answers that I got whenI employed those devices, but that's okay. That's notnearly as important as the fact that, by and large, Iconvinced them that those are the tools to be used in thefinal analysis.And if I am right in thinking that I brought about thatkind of mental process change, well, that is going to bearound for a long time to come.D16<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

nThe Zealots vs. the Wackoss:by Thomas]. CampbellAssociate Professor ofLawT'he Reagan administration'sapproach to antitrust enforcementhas stirred up a controversyover the ends and means oftrust-busting.Some of the issues involved wereraised in the brief opposing certiorariof Monsanto v. Sprayright, aresale price maintenance case setfor argument this December beforethe U.S. Supreme Court. The plaintiffwon at trial, and on appeal. Allwas going well for the plaintiff, evenafter a petition for certiorari wasfiled, until the Justice Departmentfiled a brief urging certiorari begranted and the case reversed.The respondent argued that thegovernment's brief was a treatise onwhat the law should be, and bore norelation to what the law was, or towhat the facts of this case were. Ifthe "zealots" in the antitrust divisionare intent on changing the law, thebrief continued, they should bringtheir theories to the Congress, andstay out of cases such as this.These respondents were relying,of course, on 72 years of SupremeCourt decision law dealing with verticalprice agreements. AssistantAttorney General William Baxter,who heads the Antitrust Divisionand holds a chair at <strong>Stanford</strong> LawSchool, * has a description for theSupreme Court decisions uponwhich the Sprayrite attorneys sodiligently rely: "esoteric, baseless,simply made up, wacko." Hence,the subtitle of this article, "TheZealots vs. the Wackos."<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> 17

I hope that my topic will have interestbeyond antitrust, for I believethe antitrust area is an example oftwo trends with more general applicationin this administration: theuse of economic doctrine in the faceof sometimes noneconomic statutes;and the heavy reliance on therule of prosecutorial discretion contraryto congressional direction.I do not necessarily find these approacheswrong. Nor are they uniqueto this administration. The Departmentof Justice has not enforced theRobinson-Patman Act for manyyears, relying on economic grounds.And as for pronouncements aboutthe antitrust laws, Justice OliverWendell Holmes opined that the entireSherman Act was a "humbugborn of economic ignorance and incompetence."That, I believe, is thenineteenth century translation of"wacko."Turning to the first point - economics-thisadministration's antitrustenforcement approach hasbeen a conscious, painstaking effortto establish one overriding principleas the goal of antitrust: economicefficiency. This term translatesroughly to producing the amount ofproducts that consumers demand asclosely as possible to the priority inwhich they are demanded, and at theleast cost.That sounds like a worthy goal.What is missing? Explicit concern forwho pays for the product-the consumer.Explicit concern for whomakes the product-the nation ofshopkeepers, worthy competitors,the noble small businessmen, thosewhom Justice Peckham called "smalldealers and worthy men." And explicitconcern about who accumulatesthe wealth- a diverse group ofconsumers, or a wealthy, bloated,octopus-like trust? Itis fruitless to tryto claim that these interests play nopart in the genesis of the antitrustlaws. Quite the contrary-the pagesof legislative history and early caselaw virtually drip with unctuous solicitudefor these goals.The great Senator Sherman himselfspoke in these words of the evilof trusts: "among them all, none ismore threatening than the inequalityof condition, of wealth, and opportunity...."He observed that "[some]combinations [might be able to] reduceprices by bettermethods of production."But this was a Faustianbargain to be rejected, since "[the]saving of cost goes to the pockets ofthe producers."Another member of Congressspeaking on the Sherman Act rose inagreement:Even ifthe price ofoil is reduced to onecent a barrel, it would not right thewrong done to the people by the trustswhich have destroyed legitimate competitionand driven honest men fromlegitimate businesses.And Judge Learned Hand authoredwhat many consider the conclusiveword on this subject, in the Alcoacase, with language that was subsequentlyembraced by the SupremeCourt itself:Congress . . . did not condone '[{oodtrusts" and condemn ((bad" ones: itforbade all. Moreover, in so doing itwas not ·necessarily actuated by economicmotives alone. It is possible,because of its indirect social or moraleffect, to prefer a system of smallproducers, each dependent for hissuccess upon his own skill and character,to one in which the great mass ofthose engaged mustaccept the directionofafew.But the current administrationdoes not favor these noneconomicgoals. We have new merger guidelines,allowing higher levels of industryconcentration. Before, a smallproducer could sue to prevent evenso small a concentration as sevenpercent of the market. We have reducedenforcement actions against18 <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

vertical price-setting through resaleprice maintenance. As the administration'scritics would describe it: abig, powerful, overreaching conglomerateis allowed to tell maand padrugstores on the corner exactlyhowmuch they must charge for toothpaste,and consumers must pay thatprice. A dominant firm twice or tentimes the size of a small companytrying to enter the market, and withcost advantages over a smallerfirm can drop its price so low that the newplayer can't earn a profit and has todrop out, after which the dominantfirm can lift its price again.Thurman Arnold, the antitrustchief in the Franklin Roosevelt administration,used to say that bringingan antitrust case was much like aPlains Indian hunting buffalo - allyou had to do was shoot an arrow intothe herd and you'd be sure to hitsomething. These days, criticswould say the Indians are spendingall their time contemplating their arrows,asking whether it is efficient touse them, since, if you wait longenough, a buffalo is likely to dropdead of its own accord.What defense can be made for thisenforcement approach? First is tolook at some other types of antitrustenforcement that are going on, specificallyin the horizontal area: agreementsamong competitors. When Iwas director of the Bureauof Competitionat the Federal Trade Commission,I authorized complaints againstthe second and third largest mergersin history-Mobil's attempted acquisitionof Marathon, and Gulfs attemptedq.cquisition of Cities Service.Both mergers were stopped.Bill Baxter has put 127 businessmenin jail, and has collected over$47 million in fines for bid-rigging onhighway construction, a record unparalleledin Antitrust Division history.He has stretched the ShermanAct §2 past the breaking point, tocharge the president of AmericanAirlines with conspiracy to attemptto agree to fix prices, even though theother party to the potential conspiracywas far from agreeing; hewas calmly tape-recording the wholeconversation!And the FTC chairman, far fromrolling over in the face of the mostpowerful professional trade associationin the United States because itbears the prestigious name AmericanMedical Association, pressed theantitrust suit and brought the nationalorganization and many localsunder FTC order. So aggressive didhe become in his endeavors that theAmerican Bar Association wasmoved to endorse a resolution at its1983 annual meeting in Atlanta urgingan exemption from the FTC Actfor all professionals. One delegatelikened the FTC to an 800-poundgorilla with bad breath.And I personally testified beforeCongress, in opposition to a bill toallow United States shipping lines toagree among themselves on pricesand routes, because such agreementswould result in higher pricesfor every consumer item that had tobe shipped.The first response is this: economicscuts both ways. Once youhave decided to make it your goal,and disregard the other suggestedgoals of antitrust, a whole vista ofenforcement actions opens up.Most obvious as targets are thosepeople, whether professional menand women or local governmentagencies, who see their higher callingas justification for some "rationalizationof the market."The Supreme Court had an answerfor such assertions, in the NationalSociety of Professional Engineersand the City of Boulder cases: nonoble purpose that reduces economicefficiency is adequate to excuse anantitrust violation. And this administrationhas pushed that principlewithout stinting-so much so thatyour phones may no longer work, but<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> 19

you have the comfort of knowing, asyou sit there listening to static on along-distance call, that you are notpaying to subsidize some ten-centlocal call from a pay phone!There is another answer as well. Itrequires the realization that the othergoals of antitrust- protecting smallbusinesses, lowering prices to consumers,allowing room for the littleguy in every market-are not free ofcost, although the lore is to the contrary.In the Northern Pacific case,the Supreme Court held:The Sherman Act . . . rests on thepremise that the unrestrained interactionofcompetitive forces will yield thebest allocation of our economic resources,the lowest prices, the highestquality, and the greatest materialprogress, while at the same timeprovidingan environment conducive tothe preservation of our political andsocial institutions.But these worthy goals are simplynot all achievable at the same time.Many mergers will lower averagecosts in an industry, but necessarilyleave less room for the small producer.Agreeing to guarantee a retailprice for your own product is oftenthe only way to obtain a spot in aprestigious retail store, yet it doesleave less freedom for the discounters.Allowing a larger firm withlower costs to undercut a new entrant'sprice will deter such entry, butto allow the entry would increase theoverall cost levels of that industry.As an enforcement matter, wherethere was no plausible economicefficiency reason to hesitate or evenwhere the record was uncertain, Iwould not fail to bring a case. But inthe face of higher costs, I would hesitate.This was for two reasons.First is that the United States, in acompetitive world economy, simplycannot afford to increase its costs.Many goals that might have beenaffordable' when the United Stateswas the dominant producer of almostall manufactured goods are luxuriesto pursue in today's environment.Chief Justice White noted in the veryfirst Standard Oil case that the anti-trust laws, which were written in thebroadest possible terms, would be informedby and would change witheconomic circumstances. To acceptless efficient means of production issuicide for American industry in thecircumstances of these times.My second response meets the"other" social goals argument headon. Assume for a moment that sidingwith the efficient course in an antitrustcontext means allowing a large,entrenched companyto receive moremoney than it otherwise would, and asmaller company to receive less. Butif the advantage were given to thesmaller company, the cost of productionwould rise. Who pays for thathigher cost of production? The large,dominant firm? Only in part. Theconsumers of the product? Only inpart. The real victims are producersand purchasers of other goods, perhapstotally unrelated, who cannotobtain the resources to producethose other goods, or have to pay ahigher price to obtain them becausemore resources are being consumedin the first industry than are necessaryto produce those goods.So exactly whom are we helpingand whom are we hurting? We arehelping a less efficient producer; andwe are hurting hundreds of otherproducers and consumers in industrieswe cannot begin to trace. Andeven if we hurt the dominant firm alittle-call it the Octopus Corporation- the days are long past when arobber baron would be deprived ofhis greedily acquired loot. Rather,the shareholders of the dominantfirm will be hurt. I, for one, have noway of estimating whether thoseshareholders are more or less worthythan the shareholders of the smallerfirm -or the consumers themselves.All three groups are likely to includepension funds, insurance companies,and well-meaning universitieswhich, deprived of lucrative investmentopportunities, will have to askmore from their alumni/ae.There still remains, at least to me,something that is unsettling. Andthis introduces my last main point.To review: the antitrust laws havemany purposes-that must begranted. We should try to vindicatethose purposes. But it is appropriatewhen the goals are at cross-purposesto champion economic efficiencythatwhich will lower costs becausesuch a course eventually redounds tothe entire economy's benefit.Still, what do you do when the lawsays to ignore efficiency?Sure, there'splenty of room for elbowing around.The Sherman Act requires proofthattrade has been restrained; the ClaytonAct requires proof that competitionhas been injured. These prerequisitescan be used to defend aneconomic choice most of the time.20<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

But this is not always so. TheRobinson-Patman Act is one suchexample. It was passed explicitly tohelp small business by requiringmanufacturers to charge the sameprice to all similarly situated retailers.It also outlaws any discrepancyin the amount of money for promotionsor advertising paid by manufacturersto retailers. The ban is absolute.No finding of economic harm orbenefit is required.Frequently, however, price andpromotional discrepancies of thiskind are verydesirable. Consider oneexample: a tacit cartel among producersto charge the same price, acartel that can be broken down byquiet price concessions in the form ofadvertising allowances from a manufacturerto some distributors. Yet theRobinson-Patman Act makes thoseillegal. It essentially promotes thecartel's operation and inhibits thecartel's demise. It's the policemanguarding the door while the pokergame goes on inside.What should a law enforcementagency do? Enforcing the law in thiscontext is a transfer of money thatthe Congress has legislated, presumablyknowing its costs. Why shouldthat surprise us? After all, every yearthe tax laws collect money, and theappropriation bills distribute it. Congresshas simply found one more wayto tax and spend. We can point thisout. We can measure its costs to theeconomy. We can complain. But wecannot ignore the law.This issue has received someprominence recently in the areaofresaleprice maintenance or verticalprice setting. In my view, there aremany instances where retail pricesetting by a manufacturer has goodeconomic justification, and to preventthe practice would harm theeconomy. But there are also many instanceswhere, as far as one can tell,resale price maintenance is not economicallyhelpful. The evidence justisn't there in every case that guaranteeinga resale price will ensure amarket niche, or make certain theamount of salesmanship by the retailerthat the manufacturer con-siders necessary. In these cases, wesimply cannot prove that the practicepersists for economic reasons.The Administration's spokesmenwould, I believe, rely on a presumptionthat if a practice is beingfollowed and is not demonstrablyanticompetitive, it must be for anefficient reason. The presumption Iwould defend is that the law is meantto be enforced - unless it would domore harm than good to do so. Butthose who hold the first view wouldsay that such prosecution is unnecessary.If the practice were inefficient,sooner or later the market wouldweed it out. The firm would sufferagainst its more efficient rivals andwould drop the practice or perish.It is for this reason that it takeszero Chicago school economists tochange a light bulb. The bulb willchange itself.More deeply, the problem with relyingon the presumption which, Ibelieve, is true in the long run, is thatthe law compels a different presumption.This particular law does notcontemplate a longer run; it seeks atransfer of wealth now, not an efficiencynirvana eventually.In failing to respect this aspect ofantitrust law, the apologists for noninterventionare making a seriouslong-run mistake of their own. Thelaws are made by Congress and interpretedby the courts. To fail to enforceany of those laws as a generalpolicy is to stymie the governmentalsystem. No one would disagree thatscarceenforcementresources shouldbe spent where they can do the mostgood. No one would quarrel with aprosecutor's discretion not to chargean offense when such a charge woulddo more harm than good in any givencase.But that is not what is being saidhere. In relying on the general presumptionof economic efficiency, thenoninterventionists are directly contestingthe congressional determinationthat, whether efficient or not ingeneral, certain conduct is not to bepermitted.This policy, I believe, is wrong as amatter of the separation of powersdoctrine. But, perhaps more tellinglyto the audience I need to convince, itis not efficient. Thelikely response ofthe Congress to such continued behavioris to draft much more specificstatutes, making concrete particularpractices it wants prosecuted, eliminatingprosecutor's discretion asmuch as possible, and requiring theexpenditure of scarce resources toinvestigations of such behavior andnot other kinds of behavior.This has already come to pass.This spring, for the first time, theFTCbudget has a line item for prosecutionsof resale price maintenanceviolations. Whether the Congresscould go one step further and compelactual expenditure for prosecutionsis a constitutional issue I must leaveto my teacher of constitutional law,Dean Ely. I would have great reservationsabout any such attempt,though some claim could be made tocompel the Federal Trade Commission,if not the Justice Department,to do just this, since the FTC sitsoutside of the executive branch.And on the part of the courts, I fearthe likely response to this attitudewill be a general lowering of tolerancefor the fundamentally correcteconomic contributions that this approachotherwise has to offer.So you have the zealots versus thewackos. Over the last ninety years,<strong>Stanford</strong> Law School has producedsome of each. This Administrationhas given unparalleled opportunityfor both schools to be heard fromsomevoices resounding from within,others crying in the wilderness. Tosome degree both are being heard onthe Farm.Whether ultimately proven rightor wrong, it does not surprise me that<strong>Stanford</strong> people are in the thick ofthis development. The intellectualvortex has moved away from the<strong>Stanford</strong> of the East and the <strong>Stanford</strong>of the Midwest and has returned towhere it belongs, to <strong>Stanford</strong>-youralma mater and my new home. D*Professor Baxter, who has since returned to<strong>Stanford</strong>, discusses his antitrust policies inthe preceding interview (pp. 10-16). - En.<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>21

AtISSUETOViardAnEffective Peace Movementby John H. BartonProfessor ofLawIn 1964, Supreme Court JusticeDouglas wrote:... time is shorter than people think;the areas of friction that can easilytrigger the nuclear holocaust arespreading; military solutions arenow the only impossible solutions.Across the world, men have somehowgot the message ofON THE BEACHby Neville Shute and FAIL-SAFE byBurdick and Wheeler. Men are filledwith fear ofwhat the bomb can do andare becoming more aware ofthe needfor a Rule of Law that will take theplace ofthe Armed Forces. *Except that the books and movieshave changed, Douglas might havebeen writing today. The fear andawareness of which he was speakinghelped achieve several armscontrol agreements in the 1960s andcontributed to SALT in the early1970s. Yet, that force was politicallyspent by the mid 1970s, and thoseearlier arms control agreementshave brought only a limited benefit.Is today's interest in nuclearweapons control likely to be moresuccessful?The political thrusts of the twotimes differ in two important ways.First, today's movement is muchmore broadly supported than wasthat of the 1960s, which was in largepart one of intellectuals and scientistsarguing that arms controlstrictly served the national interest.When the executive responded tothis argument, it faced a reluctantCongress and only rarely expectedto gain much public support.Today's movement is different. Itis perhaps in large part a reaction tospecific Western deployments andto specific United States administrationstatements and may fade asthese issues disappear. Nevertheless,it is stronger in Congress andthe public than in the executive andit reaches well beyond the diplomatsand scientists traditionally interestedin defense issues.The new movement, however,brings a much less well elaboratedinternational strategy. Its centerpiece-thenuclear freeze-is almostuniformly regarded by armscontrollers as a poor idea, save tothe extent that it might open theway to later reductions. In contrastto the discussions of the 1960s, themilitary aspects of security and thepolitics of international organizationare nearly forgotten.This is partly because those in the1960s failed to educate the publicabout security issues, and thought22<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>

they could succeed by dealing onlywith their allies in the government.It is partly a result of American emphasison technological solutionsover political solutions. Primarily,however, it reflects the fact that thenew movement is much more a desperateprotest and a reaction to thehorror of nuclear war.The current movement does havea sophisticated domestic strategy:political action to achieve congressionalresolutions, encourage presidentialaction, and elect a sympatheticpresident and Congress.But this sophistication may bewasted. Without political leadershipfor a more precise and workableagreement concept, efforts tonegotiate a freeze are likely to leadback to a package similar to theSALT II package that failed beforeCongress.More important, history suggestsgrave doubt whether a first agreementwould bring the predictedmomentum for reductions. In 1972,SALT I called for a SALT II in fiveyears, but SALT II has not yetcome. The sequence of weaker andweaker naval treaties during the1920s and '30s similarly argues thatsecond agreements are muchharder to reach than their predecessors.In short, the current antinuclearmovement may have little effectunless there evolves a workableglobal strategy within which itsarms control goals can be placed. Iwould suggest three central postulatesfor that strategy.First, the strategy should paymuch more attention to the developingworld than to the Soviet Union.East-West stress focuses attentionon strategic arms control-and alsomakes that arms control difficult tonegotiate. In contrast, there arenow many opportunities for makingpeace in the developing world, anarea which is the scene of war andwhose conflicts are the most likelysource of nuclear war.We should now be seeking arrangementsthat might help providepeace in Central America, thatmight reduce our incentives andEurope's incentives to export arms,or that might forestall future conflictsover the flow of refugees fromrapidly growing developing nationsto slowly growing developednations.Some of these arrangements mayrequire international agreement;others may be achievable throughlegislation in the tradition of theWar Powers Act or the NuclearNon-Proliferation Act. We mayhave to wait to deal with the SovietUnion; there is no value in paralysisin the meantime.Second, the strategy must focuson the reform of international organization.Arms control has seemedpopular and feasible; internationalorganization unpopular and infeasible.Yet, serious analysis has alwayscoupled the two. The statementby Justice Douglas quotedabove was taken from a preface to acollection of actual disarmamentproposals, the most important ofwhich-that of Grenville Clark andLouis Sohn-sought major reformof international organization as partof disarmament. Woodrow Wilsonmade the same point in working forpeaceful settlement procedures andfor the League of Nations.We must move on with this task,both to prepare for actual armscontrol and to respond to today'stensions. We may not yet be able toreform the United Nations, nor cannew international organization yethelp in our relations with the USSR.Nevertheless, we can improve organizationsdealing with economicand monetary questions, with disputesettlement, and with regionalsecurity in the rest of the world.Moreover, we can build new organizations- particularly those, like thedirectly elected European Parliament,that give individual citizensan opportunity to participate andgive political parties a chance totranscend national boundaries.Third, in building these organizations,it is essential to seek politicalallies from a broad front. The 1960santinuclear movement sought tobe technical and nonpolitical, andtherefore lacked staying power.The 1980s movement, when itexpands its constituency at all,tends to look to traditional liberalissues such as nuclear power andthe environment. On a global level-and perhaps within the UnitedStates as well-these are middleclassissues, unlikely to generatethe sustained political thrustneeded to build international order.It is rather movements built firstaround economics and political freedomthat will create the internationalorganization later able to controlweapons. The alliances neededare not just among traditional liberalnonprofits; they are also withinternational business and withnational labor groups and even, aswith the Socialist and ChristianDemocratic parties in Europe, politicalparties in different nations.We will have many disagreementsabout these economic andpolitical issues - but that is a reasonfor alliances that reach such issues,and for organizations that bring ustogether as disagreeing and thinkingindividuals. The most importantrole for international organization isto give us a way to face and discuss,to resolve, or to live with those disagreementswithout war- and thatis what we will have to do to makedeep arms control possible.We can begin with our disputes inthe free world over the magnitudesof economic deficits, the behavior ofmultinational corporations, or thetreatment of linguistic minorities.If we succeed at all, we will attractSoviet participation long beforewe have to seek it. D*Foreword, Current Disarmament Proposalsas ofMarch 1, 1964, p. xix (World Law Fund,1964).Professor Barton, a member of the<strong>Stanford</strong> Law Class of 1968, joinedthe faculty in 1969. His publicationsinclude The Politics of Peace: AnEvaluation of Arms Control (<strong>Stanford</strong><strong>University</strong> Press, 1981).<strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong> <strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong>23

AtISSUETrading in Art:Cultural Nationalism vs.Internationalismby John Henry MerrymanNelson Bowman Sweitzerand Marie B. SweitzerProfessor ofLawwork of art is a piece of the culture.Paintings and sculpture,Alike music and literature, define usto ourselves, give us cultural identity,enrich our lives and extend ourexperience. They develop the otherhalf of our brain, the half that caneasily wither in the rationalist atmosphereof law school and lawoffice.Paintings and sculpture are fragilein a way that does not affectworks of music or literature. If theoriginal manuscript of Schubert'sQuintet in C were destroyed, thework would live on. Editions, copies,"reproductions" of the Quintetwould survive in music librariesthroughout the world and would,for most purposes, be perfectly satisfactorysubstitutes. Loss of themanuscript would be a tragedy, buta minor tragedy.But if a great painting or sculptureis destroyed - even one that hasbeen widely reproduced-the tragedyis of a different order. The workof art is somehow embodied in theobject. Rightly or wrongly, we wantto look at the real thing. Just asfakes and forgeries falsify the culture,so reproductions seem inadequateto represent it.Without that kind of insistence onthe real thing, so that even the bestreproduction is a poor second best,the raison d'etre of art museumswould disappear. Authentic piecesof the culture are what museumswant to preserve and display andcollectors to collect. This peculiarityof works of visual art, whichapplies to ethnographic and archaeologicalobjects as well, has importantpractical consequences.Most nations (Switzerland andthe United States are major exceptions)have enacted laws limitingthe export of cultural objects.Nations attempt to keep such objectsfrom leaving their boundariesfor a variety of reasons. Some oftheir restrictions seem completelyreasonable and deserve internationalsupport.An example is Mexico's intentionto retain the Aztec Calendar Stonein the collection of the NationalMuseum of Archeology in MexicoCity. It is a unique monument of anindigenous culture; the governmentof Mexico owns it; it is adequatelyhoused and protected; and it is publiclydisplayed.Other examples of retention are,however, completely unpersuasive- for example, the insistence ofMexico and other Latin Americannations on hoarding and prohibitingthe export of multiple examples ofpre-Columbian sculpture and ceramicsthat may never be displayed,studied or documented at home, butwould be welcomed in foreignmuseums and collections. Or the notionthat a private~y owned paintingby Matisse, a French artist, shouldnot be exported from Italy.It is undeniably within the powerof nations to enact and attempt toenforce such laws, no matter howunreasonable they seem. However,it is not only foolish, but actually destructive,for any nation with a largestock of undocumented, unhoused,unprotected, often undiscoveredantiquities to prohibit their export.If there is an international marketfor these objects, such restrictionsguarantee that:• excavation and export will be carriedon covertly, callously, andanonymously, with no resulting documentation,with irretrievable lossof archaeological and ethnographicinformation, and with irreparabledamage to sites and objects;• the income from trade in such objectswill go to the wrong people;• any opportunity to pursue a rationalpolicy for systematicallyrepresenting the national culture inforeign museums and collections isforegone;• national scholars, museum personnel,police, and customs officialswill be frustrated, demoralizedand corrupted; and• the most valuable works will bethe most likely to leave the country.In short, nationalistic measurespurporting to retain and protect culturalproperty may in practice contributeto their loss and destruction.Blind cultural nationalism is a selfdefeatingpolicy.A more cosmopolitan attitude, expressedin the Hague Convention of1954, is that "cultural property be-24<strong>Stanford</strong> <strong>Lawyer</strong> <strong>Spring</strong> <strong>1984</strong>