1 - Eureka Street

1 - Eureka Street

1 - Eureka Street

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The Vatic-Edmund Campion on the AustraliaWhat price Australiannaway and An r ami Ir fugees, 'illegals'

AUSTRALIANBOOK REVIEWSEPTEMBER:Chris wattace~-GraDorothy Porter,Michael Hofmann,Fay Zwicky,Anthony Lawrence,Anita Heiss,Merlinda Bobis,Tien Hoang Nguyen,Deb Westbury,MTC Cronin,Geoff Goodfellow and many mo reImelbournefestivalHumphrey McQueen onthe Chinese connectionRolling Column by Mark DavisKerryn Goldsworthy on Thea Astley' sDry landsMarilyn Lake on Beryl BeaurepajreMari on Halligan onAndrew Ri emer's new memoirofpoetrySubscribers $55 for ten issues plus a free bookPh (03) 9429 6700 or Fax (03) 9429 2288chapelseptember1999offchapelprahran9522 3382r;"t.,~;:;:;::::;-;;;;;::rn!l:;n~..r.w,,.,;::;;=rr-""""IIPIIOff ChapelinHiativesupportedby ArtsVictoriaArt MonthlyAUSTRALIAIN THE SEPTEMBER ISSUEPeter Hill interYiews Liz Ann Macgregor,new Director of the Museum ofContemporary Art•Daniel Thomas talks about being a curatorArtRage - Mat Gallois onbeing an emerging artist in SydneyThe Immigration Museum and theMillionth Migrant exhibitionOut now _S-1.9.'i, .fimn good boohlwps and ncii'Sagcnls.Or plu111c ()] 62-19 3986 jin· your mbsaiption

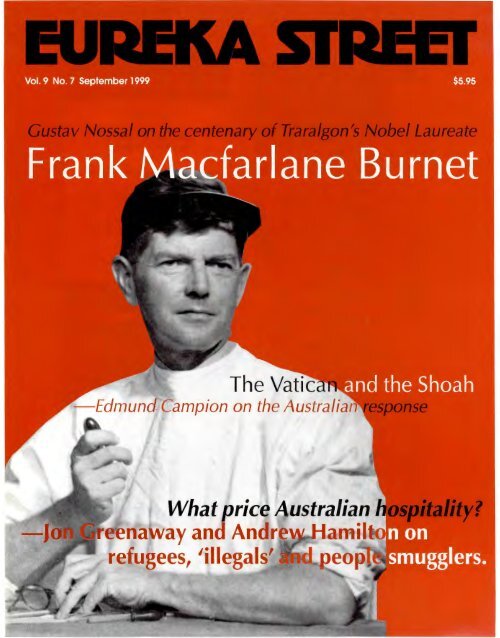

A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theologyVolume 9 Number 7September 1999'He loved tospeculate,sometimes almostdangerously,from everyexperiment heperformed,seeking to derivegeneral n1eaningfrom resultswhich, in the firstinstance at least,are always highlyparticular andspecialised.'- Gustav Nossal onMacfa rl ane Burnet, see p22Cover design by Siobhan Jackson.Photograph of Sir MacfarlaneBurnet courtesy The Wa lter andEliza Hall Institute of MedicalResearch, Melbourne.Graphics pp5, 16, 18, 19, 20, 28,3 1, 43 by Siobhan Jackson.Photographs ppl0- 13 courtesyJon Green away.Photographs pp22- 27 courtesyThe Wa lter and Eliza HallInstitute of Medical Research,Melbourne.Photograph p35 by Barbara Leigh.<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> magazineJesuit PublicationsPO Box 553Ri chmond VIC 3 12 1T el (03)9427 73 11Fax (03)9428 4450CoNTENTS4COMMENTWith Mark McKenna andFrancis Sullivan.7CAPITAL LETTER8LETTERS10TRAFFICKING IN PEOPLEJon Greenaway investigates thesupply side of illegal immigration.Andrew Hamilton questions Australia'sreception of 'illegals' and asylum seekers.16THE MONTH'S TRAFFICWith Edmund Campion, Hugh Dillonand Kathy Laster.17SUMMA THEOLOGIAE19ARCHIMEDESOur man turns the microscope onscientists, sex and boxer shorts.20THE STATE OF VICTORIAAs Victoria heads for elections,Moira Rayner takes stock.22SIR FRANK MACFARLANE BURNETSir Gustav Nossal on the science andcentenary of a distinguished Australian.28BLACK AND OTHER ARTSJim Davidson on what the GrahamstownFestival tells us about the newSouth Africa.3 1OBITUARYLinda McGirr salutesJennifer Paterson.32AFTER THE BIG WAVEPhotographic essay by Peter Davis.34INDONESIAN WITNESSPeter Mares interviews Ibu Sulami,activist, feminist and political survivor.37THE MANY ANXIETIES OFAUSTRALIA AND ASIADavid Walker's Anxious Nation:Australia and the Rise of Asia, 1850-1939shows how complex Australia-Asiarelations have always been, saysPeter Cochrane.40BOOKSPeter Craven reviews William Maxwell'sreissued novel, The Folded Leaf;Peter Pierce makes a m eal of ThomasHarris' Hannibal (p41 ).43THEATREAustralian theatre needsnatural therapy, argues Peter Craven.Geoffrey Milne surveys som e ofAustralia's winter offerings.45POETRY'Tadpoles' and 'Norfolk Island Pine'by Kate Llewellyn.48FLASH IN THE PANReviews of the films Tea With Mussolini;Eyes Wide Shut; Two Hands; My Nameis Joe; Playing by Heart andBedrooms and Hallways.50WATCHING BRIEF51SPECIFIC LEVITYV OLUME 9 NUMBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 3

EURI:-KA srru:-erA magazine of public affairs, the artsand theologyGeneral managerJoseph HooEditorMorag FraserAssistant editorKate MantonGraphic designerSiobhan JacksonPublisherMichael McGirr SJProduction manager: Sylvana ScannapiegoAdministration manager: Mark DowellEditorial and production assistantsJuliette Hughes, Paul Fyfe SJ,Geraldine Battersby, Chris Jenkins SJCon tri bu ting editorsAdelaide: Greg O'Kelly SJ, Perth: Dean MooreSydney: Edmund Campion, Gerard WindsorQueensland: Peter PierceUnited Kingdom correspondentDenis Minns orSouth East Asia correspondentJon GreenawayJesuit Editorial BoardPeter L'Estrange SJ, Andrew Bullen SJ,Andrew Hamilton SJPeter Steele SJ, Bill Uren SJMarketing manager: Rosanne TurnerAdvertising representative: Ken HeadSubscription manager: Wendy MarloweAdministration and distributionLisa Crow, Mrs Irene HunterPatronsEvrelw <strong>Street</strong> gratefully acknowledges thesupport of C. and A. Carter; thetrustees of the estate of Miss M. Condon;W.P. & M.W. Gurry<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> magazine, ISS N 1036-1758,Australia Post Print Post approved pp349181/003 14,is published ten times a yearby <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> Magazine Pty Ltd,300 Victoria <strong>Street</strong>, Richmond, Vi ctoria 3 121T el: 03 942 7 73 11 Fax: 03 9428 4450em ai l: eure ka@jespub.jesuit.org.auhttp://www .openplanet.com.au/eureka/Responsibility for editorial content is accepted byMichael M cGirr SJ, 300 Vi ctoria <strong>Street</strong>, Richmond.Printed by Do ran Printing,46 Industrial Drive, Braeside VIC 3 195.© jesuit Publica ti ons 1999Unsolicited manuscripts, including poetry andfi ction, will be returned only if accompanied bya stamped, self-addressed envelope. Requests forpermission to reprint material from th e magazineshould be addressed in writing to:The editor, Eurelw <strong>Street</strong> magazine,PO Box 553, Ri ch m ond VIC 3 12 1COMMENT: 1M A RK M c KENNARein ember,remeinber the 6thof N oveinberIN MA' 1888, the edi tonal-wdte< of the C andelo and EdenUnion, a small bi-weekly n ewspaper on the far South Coastof NSW, posed the following question to his readers: 'Whenwill the Australian republic come?' His answer was sure andswift.'The Australian republic will come quickly ... As wegrow more important and our population increases we thinkless and less of that old country from which we have come... We like to call ourselves Australian and feel happy thatAustralians can grasp each others' hands in the true bond ofcitizenship ... on the platform of the country's commonwealth.'If it was easy to be optimistic in 1888, it seems muchharder in 1999. Only a lit tle over two m onths out from therepublic referendum on 6 November, the prevailing mood inthe republican camp is hardly one of confidence. After weeksof negotiations in Canberra, it is now clear that Australianswill face two questions in November.The first question will ask voters whether they approveof establishing Australia as a republic 'with the Queen andGovernor-General being replaced by a President appointedby a two-thirds majority' of Federal Parliament. The secondquestion, in the words of John Howard, will present voterswith 'an opportunity to unite the country on an aspirational[sic] issue in a very positive way', by approving the PrimeMinister's revised Constitutional Preamble.The new Preamble is infinitely superior to the PrimeMinister's previous draft, but still fail s on many counts. Thereis an irony in asking the people to approve an 'aspirational'Preamble when the people were not consulted in the processof its drafting. After consulting poet Les Murray, historianG eoffrey Blainey, and others who happened to hold thebalance of power in the Senate at the right time, Mr Howardproduced the final version of his Preamble on 11 August,two days before the legislation was due to be passed byParliament in time for the November referendum. 'ThePreamble can't be changed because w e need to pass thelegislation this week,' said Mr Howard.The Prime Minister's understanding of deliberativedemocracy is novel. When asked why the new Preambleincluded reference to those who defended Australia duringtime of war he replied-'We decided last night to put that in.'The Prime Minister also believes that the Preamble willserve' as a great contribution to reconciliation ' . He describeshis effort as a 'positive, honourable, pro-active, contemporaryreference to indigenous people in our Constitution'. The word' kinship', says Howard, ' doesn ' t carry any particularconnotations of ownership, it speaks of their lands not of4EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

the landi therefore, by definition it is something thatrelates to land that is owned by indigenous people.'In other words, the white man can relax. Aboriginesdon't own 'the land', they own 'their land'. These arethe words Howard thinks are 'generous'.But where is the generosity in failing to negotiatewith Aboriginal people? The truth is that Mr Howard'sPreamble is, as he says, 'a reference to indigenouspeople' (my emphasis), rather than a document whichbelongs to indigenous people. Does this mean thewhitefella should feel'honourable' simplybecause Mr Howard h as decided tomention indigenous people in a Preamble '. ' ·which is designed to have no legal effect ? .·;,:·_::Perhaps there is a more important 'question to be answered on 6 November:'When will the Australian republiccome?'The outcome of the question on the republic willhinge largely on the ability of republicans who supportthe bipartisan appointment model to convince thosewho are sympathetic to direct election to vote Yes.To win, republicans must find cause for commonground. But there is another, and perhaps even moredifficult, task ahead-a successful defence of theproposed model against scaremongers who willmislead in an effort to defeat the republic.This campaign has already begun. In the interestsof informed debate, those who call for a more'participatory democracy'-Pet er Reith and TedMack-endeavour to frighten the electorate bychanting 'Sixty-nine changes to the Constitution I' andaccusing the Australian Republican Movement of'ethnic cleansing'. Add the old favourites such as'more power to Canberra' and the high fence that isSection 128 (which requires at least four states and anational majority if the referendum is to pass), and itis easy to appreciate the difficulty of the challengewhich faces republicans in November.The referendum will ask voters to continue thetradition of Australia's gradual evolution to independence.The proposed bipartisan appointmentmodel is entirely consistent with themaintenance of our existing politicalinstitutions. It offers no radical break withthe past. The m odel's flaws are all presentin the current system. Australians willeither approve this last conservative step\:7 \J in the process of decolonisation or continuewith the British monarch as their h ead of state.For this writer at least, the thought of voting toretain the monarchy as the symbol of modernAustralian democracy is n either ' positive' nor'honourable'. Nor does it make sense. The 'historicachievem ent'-in-waiting is n ot the insertion of amonarchist's Preamble in our Constitution, butthe declaration of an Australian republic on1 January 2001. •Mark McKenna is a post -doctoral fellow in thePolitical Science Program at the Research School ofthe Social Sciences, Australian National University.C oMMENT: 2F RANCJS SULLIVANThere's nothing surer• • •S TATe AND Tc.moRY mom w•nted 'notion•!health inquiry. The Prime Minister didn't. They gota Senate committee. The inquiry comes as the broaderissue of welfare reform challenges m ost Westerndemocracies.Whether it's in health care, pension support, aged,disability or unemployment services, reform iscomplex. On the one hand, the bleak forecast is forageing populations and diminishing numbers oftaxpayers. The community's capacity to sustainsafety-net services, pension levels and e n~itl ementschem es (like M edicare) becomes questionable. Onthe other hand, the gap between the fortunate andthe rest is gradually widening. Prosperity for manyfamilies is transitory, if not elusive. Many are solelyreliant on safety-n et services, like public health careand income support, just to get by. In this context,universal health cover is a social good-wage supplement and family assistance package rolled into one.The latest income distribution figures are stark.The top 20 per cent of households receive nearly SOper cent of all incom e. Social security dependency hasrisen. Over 60 per cent of sole-parent families havewelfare as their principal source of income. Over 40per cent of single people between 15 and 44 have nowork or are underemployed.The group of Australians existing above theselevels, without any welfare assistance, are likewisevulnerable to the potentially enorm ous financialdamage that sickness and chronic illness can do tohousehold budgets. Their capacity to purchase privateh ealth insurance as a safety n et is limited. Theinflationary rate of h ealth insurance h as averagedaround 8 per cent. Real wage growth has not kept pace.In this context, the economic value of Medicareis that it spreads the financial risk of sickness across theentire community. It ensures that access to essentialcare is not restricted by one's capacity to pay. ThisVOLUME 9 N UMBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 5

system only remains effective if everyone contributes,regardless of their health status, age or income.Medicare's critics label this 'middle- classwelfare'. They contend that the well-off are the mainbeneficiaries of public hospital expenditure and access.Recent research debunks this myth.When the distributional impacts of publichospital funding are measured on income levels, theMedicare system is found to be biased towards theless w ell-off. H o useholds with incomes up to$130,000 receive only 20 per cent of the benefits thathouseholds earning less than $20,000 receive frompublic hospital funding. Also, when actual hospitalisationwas examined, high-income people receivedaround 11 per cent of the public expenditure benefits asopposed to the 17 per cent received by low-incomepeople.Medicare's impact on equity is compelling. Yetthis doesn't dissuade some state premiers from callingfor the introduction of means testing for publichospital patients. Means testing, or user charging, ispromoted as a way to add money to the system andsend 'price signals' to those who use public h ospitals.In other words, its supporters want to stop people fromtaking a 'free ride'.Even a cursory examination reveals the flaws inthis argument. For m eans testing to raise sums of anysignificance, the level at which the test would applyis far too low. On the Prime Minister's own figures,single incom es of $45,000 and family earnings of$75,000 would attract increased charges.Before the reform zealots get too excited, it'simportant to note that a large percentage of publichospital beds are used by people over 65 years of age.Most fall within these income levels. Thus the peoplewho most need the care will carry the greatestfinancial burden. Reputable research demonstratesthat of those in the highest income grouping, only 6 percent are over 55 years old. Of those in the lowes tincome groupings, up to 44 per cent are over 55. Hardlya fair approach for access to an essential service.Moreover, introducing fees for hospital care isalmost m eaningless. These 'price signals' are effectivewhere the consumer has a degree of discretion overpurchasing a commodity. Being obliged to enterhospital under medical advice leaves little discretion.M eans testing merely becomes another form oftaxation on the sick.Undoubtedly, the health system needs moremoney. The efficiency and social equity benefits oftaxation-funded health care are difficult to refute. Justas others call for increased equity contributionsthrough means testing, an increased levy on thebeneficiaries of tax reform would deliver substantiallymore funding without undermining universal access.A m ere one per cent levy increase delivers an extra$2 billion.Furthermore, the Federal Government sold theGST on the grounds that it would help fund hospitals,welfare and aged services. This new growth tax willcome directly from households and should rightly bedirected at bolstering essential public services.The Commonwealth and the states should bepressed to drop ineffective solutions for the healthsystem and demonstrate how the GST monies willbe directed towards improving waiting lists and accessto other essential services.•Francis Sullivan is Executive Director of CatholicHealth Australia.tendering in the community sector, 'Contestingwelfare' (December 1998, see left, withphotograph by Bill Thomas), was highlycommended in the ACP A Best Social Justicecategory.AwardsCongratulations to writer John Honner and<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>'s design and production team,Siobhan Jackson and Kate Manton, for theirsuccess at the recent Australian Catholic PressAssociation and Australasian Religious PressAssociation Awards. <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> won theACP A Best Magazine Layout & Design Awardand was highly commended for design byARPA. John Hanner's article on competitiveWinnersWe are pleased to announce the winners ofthe Jesuit Publications Raffle, drawn on12 July 1999. The first prize-overseas travelfor two from Harvest Pilgrimages-goes to<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> subscriber Marian Devitt fromCasuarina, Northern Territory. Second prizegoes to P. Dalziel!, Randwick, NSW; thirdprize to B. Jensen, Clontarf, NSW; fourth prizeto Josie Osborne, Ryde, N SW; and fifth prizeto Sr Margaret O'Brien, Darlinghurst, NSW.Many thanks to everyone who participated.The raffle continues to be an importantsupport to our publications.6EUREKA STREET • S EPTEMBER 1999

I 1! I 1Defence losing itsr~uARY Mi~ THffi Ym, the•~ ~u~~~~n~yg

Taxing the truthFrom Evan WhittonMoira Rayner rightly complains that'lawyers don't learn legal history anymore' ('What Lawyers Don' t Read',<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>, November 1998). Theywill find, if I may say so, my littlebook, The Cartel: Lawyers and Th eirNine Magic Tri cks, a useful introduction.I don't know where yourproprietors stand on Lotario di Segni,Pope (as he became in 1198) InnocentIII. Perhaps he was too militant evenfor the Jesuits but, as the man whoinvented a legal system based onrational investigation of the truth, heis, or should be, the hero of all whobelieve in justice.Our system, by contrast, derivesfrom a medieval craft guild, or cartel,whose product unfortunately happenedto be law. Its major aim was (andis) to enrich senior lawyers and theirdescendants. Having made their pile,they can retire to the status andunutterable boredom of an untrainedjudiciary; Lord Thankerton knitted onthe bench. After November 1215, a fewlawyers and judges in London'sembryo guild rejected Innocent'ssystem, partly on the time-honouredground that wags begin at Calais. Oursystem was thus able to develop intowhat it is today: a lucrative game basedon a lie: that truth does not matter.Ms Rayner says sh e is a lawyer andfreelance journalist. This must get abit tricky; the press has traditionalobligations to seek the truth, tointerest and amuse the customers, andto serve the community by exposingwrongdoing, particularly that whichsubverts democracy, e.g. corruption,organised crime and the legal system.She says I wrote 'a diatribe againstdemocracy, based on lawyers' "takeover"of lawmaking-and perversionof parliament' in Th e Australianbefore last year's election. It is truethat I noted that lawyers got controlof parliament in the 14th century andthat the common law world still hasgovernment of the lawyers, by thelawyers and for the lawyers. But thepiece, a short history of censorshipfrom Pope Alexander VI to JohnHoward, was surely in favour ofdemocracy, not against it.In Dangerous Estate, FrancisWilliams says the press is 'the oneindispensable piece of ordnance in thearmoury of democracy'. When Defoeinvented modern journalism at thebeginning of the brazenly corrupt 18thcentury, guildsmen on the ben ch andin parliament instantly perceived it tobe a threat to their power andcorruption. To silence the press, judgesdefined seditious libel as 'writtencensure upon any public man whateverfor any conduct whatever or uponany law or institution whatever', andin 1 712, politicians put a tax onnewspapers. It immediately wiped outseveral London journals, includingAddison and Steele's Th e Spectator.The tax on information was liftedin 1855; in 1998, Prime MinisterHoward threatened to reimpose it.I wrote: 'Howard's motive may not bethat of the corrupt Whig oligarchs, butthe effect is the same. Welcome to1712.' Courtesy of some Democrats,Australia will shortly regress to thatinglorious year; we may hope youradmirable journal of ideas does not gothe same way as The Spectator.Evan WhittonGlebe, NSWA shot in the armFrom Ken O'HaraWhat should be done to overcome thehospital crisis quickly and for sure?It seems there's a need to changetrack fundamentally, and start budgetingfor each hospital's actual needs,from the bottom up, rather thancontinuing the current practice ofgovernments allocating a neversufficientamount from top centralfunds, trickling slowly down.This way, the amount actuallyneeded for maximum hospitalefficiency will be clear, with thegovernment then acting to get it.And with the existing MedicareLevy only providing 10 per cent of totalhealth costs, expanded revenue is vital.So the ball is now in the court ofthe politicians and their top h ealthadministrators to overcome thisdeficiency quickly, or our hospitalwill surely be continuing to limp alongas if on crutches.Ken O'HaraGerringong, NSWTo advertise in Eurek

H """" -"'""' " tho mouth of 'side-alley that juts out of 'Little Arabia', arabbit-warren-like collection of bars andcafes that cater to Bangkok's substantialMiddle Eastern community. Somehow hehad walked down the narrow lane withoutmy noticing, as he had the first time we meta week earlier, when he appeared in front ofa Bangladeshi restaurant a few hundredm etres away, begging for help. He is wearingthe same rough cotton T-shirt and fadedblue jeans.Agitated, he hops from foot to foot as heagain explains thatheisin trouble. He reachesinto his money belt and pulls out the identitycard that proves he deserted SaddamHussein's army. 'If I step one metre out ofmy country, they will kill me/ h e says,chopping down with his hand like an axe.Nonetheless, Hussein is still alive. InPakistan three years ago, he paid agents(whose trade is to smuggle people acrossborders) to take him to Australia by boat.Three weeks later, after a detour via China,he was caught in Malaysia when the boatran aground, and was taken to an immigrationdetention centre outside of KualaLumpur. There he spent the next two yearsof his life, selling cigarettes and soft drinksto other detainees for profit after buyingthem himself from the guards for an alreadyinflated price. He made enough money tobribe someone in Malaysian immigrationto drop him across the border into Thailand.He had no passport- that was takenfrom him when he was arrested, along withUS$3000 he had with him to pay the pricesasked by smugglers- so he went to theoffice of the United Nations High Commissionerfor Refugees in Bangkok. Theyrej ected his claim for 'Person of Concern'status and rejected it again on appeal. Bothtimes he received the pro forma UNHCRletter that states, in an English clipped ofemotion, that he docs not qualify as arefugee. No reasons are given, no suggestionsoffered.Hussein is not alone. Ask a few questionsof any of the people smoking hookahs anddrinking sweet, grainy coffee on the side ofthe streets behind where Hussein standsand you will hear similar stories. Some arefleeing persecution in Iraq, others are drawnby the prospect of a better life in Australia,free of economic sanctions and militarism.Eith er way, m ost of them are caught inBangkok. They have paid smugglersthousands of US dollars for safe passage toAustralia and been clumped in Thailand,the easiest part of the route. They havemanaged to get out of Iraq via Jordan orSyria and are waiting to buy, from asmuggler, a passport that will get them onto a plane bound for Sydney or Perth. Theyhave applied to UNHCR, waited severalmonths for the decision, or, if they havealready been granted refugee status, theyhave waited up to two years for embassyofficials to decide whether they should beresettled in Australia.These are the people who have scaredthe Australian government into spending$124 million beefing up our coastalsurveillance operations and Department ofImmigration and Multicultural Affairspresence at key points of departure aroundthe world. In announcing these initiatives,plus the tougher penalties for smugglersand increased fines on airlines which bring'illegals' to Australia, Immigration Minister,Philip Ruddock, stressed that each 'illegal'costs Australian taxpayers about $50,000on average.Alarm at the idea of Australia's beinginvaded by boat-people carried to its shoresby an armada of leaky tubs was raised againwith the discovery of a new route down10 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

through the Pacific islands. Landings onthe east coast where most Australians liveprompted the government's response.Howeve r, while the debate over'illegals' is driven by this issue, theDepartment of Immigration and MulticulturalAffairs estimates thataround 70 to 80 per cent of thoseresiding in Australia illegallyarrived on a Boeing rather than aboat, and of those, most wouldhave passed through Bangkok atsome point. Thailand's relativelyeasy visa requirements (designedfor its tourism industry), its largeinternational airport, and itsability to absorb over one million'illegals', have made it a majorstaging point for the traffickingof people to Australia, Europeand North America. Whatevertheir reasons for leaving theircountry, n early all will havecontact with a smuggler at som estage. Smuggling is veryn big business.L oFESSOR Ron Skeleton is amigration specialist, h avingtaught at the University of HongKong's Geography Department form any years before m oving toBangkok. His position there gavehim a good view of the exodusfrom China in the early 1990s.The liberalising of the economygave Chinese people both expectationsbeyond life in the village,and the money to pay' snakeheads'to smuggle them into the US,which all this decade has beenable to absorb illegals into theworkforce. He says that migrationfollows a pattern that smugglersthem selves foster and exploit.'Migration, in whatever form,comes with n etworks: peoplecome from one province, town oreven village and when they havemoved they send informationba ck which allows friends and relatives tocome across. It is a sort of multiplier effect.'Over the last decade, Australia hasbecome established as a priority destinationfor Assyrians, Kurds, other minority groupsand political dissidents leaving Iraq. Theyare the largest group-apart from theBurmese-looking to be resettled fromBangkok, and at the moment are causingthe D epartment of Immigration andMulticultural Affairs most concern.'Alan' is a Kurdish doctor who workedwith a non-government organisation in Iraqbefore he fled earlier this year. He says heleft Iraq because NGOs are looked on bySaddam Hussein's regime as part of theinternational conspiracy against his rule.Australian govermillion beefing upoperations and Deand Multicultural Apoints of departure aThey have been the subject of attack as aconsequence of internecine fighting amongKurdish groups in Northern Iraq.Alan has been interviewed by UNHCRand is waiting for their decision. He knowsthat, had he managed to get to Australia, hewould have stood a better chance of asylum,as only a few of the 10-20 Iraqi casescurrently adjudicated by UNHCR inBangkok each month are recognised. Forhis own reasons, he preferred to try to getthere through more legitimate means. Hehas quickly discovered that the system isfar from perfect.'I know many people here who do notbother to apply with UNHCR because theythink it is useless,' he explains.'I know it is difficult for them because,with so many people applying, how do youknow who is genuine? But if they recognisedmore people, and resettlem ent to Australiadid not take so long, not so many peoplewould try to get there illegally.'Some of them pay $7000 US, m aybe$8000, for a passport or to be trafficked.Wouldn't it be better if this m oney wasspent in Australia ?'UNHCR in Bangkok is often criticisedfor not doing enough to fulfil its mandate toprotect refugees. In recent m onths it hasbeen conducting a review of the refugeestatus of Cambodians who fl ed the July199 7 violence. According t o JaneWilliamson, the termination of the refugeestatus of som e of these people who remainin Bangkok i too hasty, even going byUNHCRguidelines, and is based on a flawedanalysis of the p ermanence of theCambodian peace. Williamson is workingwith other lawyers for the Jesuit RefugeeService in Bangkok in appealing thesedecisions and can see that this is part of abigger trend in the UN's refugee agency.'There is a shift going on within UNHCRaway from permanent protection towardstemporary protection of refugees. Currentthinking is that it is better to keep peoplecloser to home in the hope that they canreturn when peace com es.'Williamson can see the benefits of thisapproach. It is part of a more durableV OLUME 9 N UMBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 11

esolution to the conflicts that producemass exodus, rather than m erely copingwith refugee problems as they arise. Shefeels the downside is that it works againstthose w ho come to Thailand in search ofasylum in a third country. She can also see,however, that UNHCR is under pressurefor tight interpretations of the RefugeeConvention.'UNHCR does not want to annoyWestern embassies in Bangkok by producinga constant stream of persons of concernwho then have to be considered forresettlement. Nor do they want to get theThai Government offside by turningBangkok into an even greater hub forillegals through a higher rate of~ recognition.'.1. HE ABILITY smugglers have to get theirhuman cargo past immigration and check-inat Bangkok's Don Muang airport has led toa colla boration between immigrationofficers from the US, Canadian, UK, N ewZealand and Australian embassies. Sincethe beginning of May they have beenworking in shifts out at the airport,collaborating with airline staff, who refersuspicious cases to them. From 6am to lamevery day, there is a compliance officer onhand to intercept illcgals travelling to anyof th ese countries. In the first two monthsthat the roster was in place, 450 illegalswere stopped. The Canadian embassyestimates that around 150 got through .'A good smuggler knows everything,'says a Sri Lankan refugee who prefers not tobe named. 'If you don't have a visa, they canorganise for Thai Tm migration to give you astamp and they also have contacts workingfor the airlines as well who will issue aboarding pass, maybe for $2000-3000.'He has lived in Thailand for eight yearswithout official status because Thailand isnot a signatory to the 1951 Conventiongoverning refugees. His applications forresettlement to anum ber of embassies havebeen rejected as attitudes towards Tamilasylum seek ers have h arden ed. In· cated by'cials from peopleard flights toers, sometimes itdesperation, he tried to get to N ew Zealandby buying a duplicate Belgian passport andarranging a boa rding-card swap with alegitimate Belgian passport holder.'What happens is he has a ticket for N ewZealand, I have one for Singapore whereI don' t n eed a visa,' he explains. 'Ourpassports are the same except for the photoevenhis initial was the sam e as mine.'Once we get through we swap boardingcards and tickets. He goes to Singapore andI go to N ew Zealand.'He go t as far as buying the fake passportfor US$500 before the holder of the originalpassport pulled out.To the naked eye, fake pa ssportsconfiscated by embassy officials from peopletrying to board flights to Australia looknear to perfect. Produced with the use ofscanners, sometimes it is only the paperquality that gives them away as fakes.Embassies organise training of airline staffto help them detect bogus passports, butdespite this, and the risk of punitivedamages, it is easy for busy check-in staff tomiss picking up a good fake.The Department of Immigration admitsthat it is impossible to stop everybody tryingt o get to Australia by illegal m ean s,particularly as the smugglers seek out thepaints of least resistance. Already theDepartment suspects that the improvementin surveillance at Don Muang airport isshifting traffic to regional ports not watchedas closely as Bangkok's. 'Ill ega ls' fly fromBangkok to Seoul, Taipei or Singapore, forexample, before heading to Australia.And n ew routes into Australia areconstantly being found. In the last week ofJuly, two undocumented Iraqis arrived inPerth on a Thai airways flight that departsfrom Don Muang but stops in Phuket onthe way.An Australian journalist, based inBangkok for many years, says that he wasapproached late at night in a hostess bar inBangkok's Patpong by two men claiming tobe Sri La nkan.'They asked if I was Australian and thenwanted to know ifl was in teres ted in makingsom e money. Naturally I was interested, soI asked what they had in mind.'They told m e that I would have a ticketfor Perth bought in m y name while anotherperson wanting to go to Australia wouldhave a ticket for Phuket on the same flight.After boarding the flight in Bangkok, wewould som ehow swap boarding cards andI would leave the pl ane in Phuket as adomestic passenger w hile the other guywould head on to Perth.'They assured m e that they had a contactin Thai immigration who would stamp meback into the country a couple of clays late r.For that they said they would pay US$300plus $100 to live on in Phuket while waitingto get the stamp.'I asked if the other guy was some sort ofcriminal, but they assured me he was agenuine refugee.'The name of an Australian passportholder appeared on the fli ght list on bothdays the illegal Iraqis arrived.A highly placed official in the ThaiImmigra tion Department recognises thatpeople will always get through. Don Muangairport hosts 20,000 passengers every clayand it is difficult, he argues, to ask Thailandto control the outflow to Australia whenAustralia cannot control its own border .So much money is made by the smugglersthat it is natural to presume, he suggests,that immigration officials who might earnthe equivalent of A$600 a month would betempted by bribes. In the last two yearsThai authorities have broken two counterfeitrings, only a fraction of those involved,according to diplomatic sources.While all the parties concerned in thetraffic of illega l migran ts acknowledge thepresence of Bangk ok-based smuggli ngoperations, it is difficult to find people who12 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

will talk about who they are and where theyoperate. Alan says it is wrong to think ofthese people as having a barber-shop shingleout the front and a fake passport factory outthe back.'They do not work out of any one place.Maybe they will meet in a hotel lobby or ina coffee shop and then they will go elsewhereto organise their business.'They might show off their wealth butthey do not want to show off how theymake it.'Not only do Middle Eastern operatorswork out of Sukhumvit Soi 3 (LittleArabia), but reportedly out of the GraceHotel that fronts it-Thai immigrationdescribes it as the centre of most of thisactivity. Other areas exist as well, such as'Soi Karachi' near the GPO, where Pakistanigroups organise passage to JapanK andtheUS.HAO SAN RoAD, the street famed forbeing patronised by backpackers, is also aplace where passports and visas can bebought, according to 'Andy', another Iraqiexile. Andy worked in Jordan as a mechanicfor three-and-a-half years to raise the moneyto buy an original Maltese passport that gothim to Bangkok. He has been here for sixmonths and is now working for traffickersas a courier.'I pick up the passport here and thenI take it there and collect the money, 200baht (A$8) for the taxi and 300 baht (A$12)for me. I am illegal so this is what I have todo to live.'Andy has worked for Iranians, Pakistanisand Palestinians. Som etimes he meets themat the Grace Hotel, sometimes Khao San.He believes they can organise anything,because they have the money.'In Bangkok all of us are poor, or aresaving our money, but they have so muchmoney. Everything is money and you can'tstop them.'Andy also suggests that their anonymityis protected by fear.'Everybody knows everybody in thisplace,' he says, pointing towards the line ofrestaurants, 'but not so well they can trusteach other. These men are very bad ...very bad.'The smuggler for whom Andy workshas an original Dominican Republicpassport with an Arabic name on it. Andy isthinking he might be able to buy it forunder US$1000 and, with a scalpel,substitute his photo for the original. Thenhe will fly to China and then from there tothe Dominican Republic before going overlandinto the US. He shows me the passportand asks me to translate the personal detailsfrom the Spanish. He will go in the hopethat no-one bothers to question him.'People trust the smugglers because theyare desperate, they are on the run, they arescared, and they come here with all theirmoney ready to spend,' Alan observes. 'Afriend of mine is here. He does not knowwhere his wife and children are. He didn'tknow anybody in Bangkok.'A Pakistani who knew some Arabicoverheard him talking on the phone oneday and promised to helphim get to Australia. Hehanded over US$4000 andhis passport and that wasthe last he saw of him.'Those in search of abetter life are ripe pickingsfor gifted con men.Twelve months ago,Thailand changed visaregulations for arrivalsfrom the People's Republicof China. The requirementthat a visa had to beobtained prior to arrivalwas repealed and nowPRC Chinese are givenvisas on arrival. This wasdesigned to bring in moretourists to boost the cashstrappedThai economy.It has, however, started aflow from China of peoplewishing to settle andwork in Thailand's extensive Chinesecommunity.When an ethnic Chinese with anAustralian passport was apprehended inBangkok in mid July for falsely advertisingworking visas for the Olympics, it wassuspected that recent PRC Chinese arrivalswere his target. He ran an advertisement forthe first two weeks of June in a Chineselanguagenewspaper published in Bangkok.The ad called for applicants to work infields as varied as broadcast media and foodpreparation. It also asked for US$2600 for avisa and intensive English training.When police arrested him h e hadUS$3500 in his possession and around 200names on his books. He has since beencharged with misrepresentation, whichcarries a maximum penalty of five yearsimprisonment and/or a 10,000-baht fine.Once they get on to a flight to Australiapeople with false documents most often ripup and dispose of what they have so as notto be sent back to their last port of call forhaving improper documentation. If theyclaim asylum yet do not have any papers,the Department of Immigration must firstprove that they are not refugees beforeturning them around. But even with thistactic in operation, the Department hasfound cause to send some back within twodays of their arrival. After spending theirlife's savings and dodging and weavingtheir way on to a plane bound for Australia,they end up in a holding cell at an Asianairport. Without any papers, they have noway forward or back. Currently anunknown number of Iraqis sent back fromAustralia are being held at Don Muangairport with no clarification of their status.One is reported to have been therefor six months.ITIS NOT ONLY IN AU STRALIA that the wallsare going up. Every Western country ismaking it more difficult for 'illegals' toarrive. But the more that barriers are erected,the more the opportunities for humantraffickers.Ron Skeldon is doubtful that thegovernment's recent initiatives will havetheir desired effect.'Illegal migration is in fact a function ofinadequate legal channels available forpeople to migrate. You are never going tostop the movement of people. We are nowmore mobile than we have ever been before,'he says.'One would expect that Australia willsee more illegal arrivals rather than less.What is more sensible is to allow the flowVOLUME 9 NU MBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 13

of migration but to control it with shorttermvisas and the like.'If the migration is legal then it can bemonitored; it is visible. If it is illegal thenthey are invisible-they just disappear.'A decision by Britain's High Court inearly August recognised that asylum seekerswere being dealt with unfairly underm easures designed to stop illegal entries.The ruling on three test cases decided thatthe UK governmen t, in jailing somewherebetween 500 and 1000 asylum seekers forusing forged docum ents since 1994, was incontravention of article 31 of the RefugeeConvention. T his article states that noasylum seeker should be penalised forentering a country illegally.In the crackdown on illegal migration(on asylum seekers, in particular), the urbanrefugee-who is not part of a mass movementof people such as that witnessed outof Kosovo-is becoming unwelcome byassociation. And they are trying to com e toa country that is both scared and angry.Scared by a new influx of boat-people andan gered by spurious appeal s in theAustralian courts by people trying to delayeviction. In this clima te the government ismore and more viewing asylum seekers asonly illegal entrants and overstayers.But a world away from the argumentabout na tiona! integrity versus in terna tiona!obligations, are people like Hussein, Alanand Andy. Three very different m en withdifferent pasts, yet all caught between somewhere and somewhere else.I asked Alan what he would do if hiscase was rejected by UNHCR. 'Som ethingillegal,' he said with a shrug.•Jon Greenaway is <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>'s SouthEast Asia correspondent.What price hospitality?L TWO me Au"'"li'n ""d" 'boutrefugees this year have been the arrival ofKosovo refugees and the coming of people byboat to populated regions of Australia.T h e governm ent had originallyannounced that it would not be givingsh elter in Australia to Kosovo refugees, butwas immediately forced, by a massive publicreaction, to offer them temporary residence.During their stay, they have been welcomedby the Australian public and particularly bythe communities surrounding the facilitieswhere they have been housed. Apart fromoccasional official defensiven ess in the faceof complaints abo ut conditions, orsuggestions that they might be allowedpermanent residence, the response to themhas been unfailingly warm.In the first half of this year, boa ts for thefirst time brought people seeking residencein Australia to the populated eastern coastof Australia. Public response has beenhostile to these people, who are perceivedas invaders breaching Australian territorialintegrity. Com menta tors have not discussedthe conditions in the nations they left, norany need they may have for asyl um; theyhave focused o n the commercial andcriminal involvement in their travel. Theboats have been said to have been charteredby criminal gangs, and the people to havebeen drawn by fra udulent advertising.T he very different response perhapsindicates that in the public mind, refugeesare not defined by their danger or theirneed, but by whether they have been invitedto come to Australia.If that is the case, Australian attitudesto refugees and im.migrants are notunrepresentative. Australia, indeed, is oneof the few nations that accepts immigrants.Most nations admit people only on working,tourist or other temporary visas. But theattitude of the present government toimmigration has been unenthusiastic; ithas been criticised for its narrowness byboth state governments and by businessgroups. Immigration is seen as undesirableboth for its short-term economic costs andfor the social pressures which it is perceivedto entail at a time of relatively highunemployment.Accordingly, the number of immigrantsadmitted to Australia is low. Theemphasis on economic factors, too, has ledto an increased emphasis on businessmigrants, and to a smaller quota of familymembers. In personal terms, this m eansthat immigrants wait longer before theycan be reunited with their spouses orparents.As is the case elsewhere, the emphasisof the Department of Immigration andMulticultural Affairs in Australia hasshifted from welcoming immigrants toexcluding unwelcome residents. Whenissuing visas, the Department takes intoaccount the likelihood that people willoverstay their visas or apply for permanentresidence. Given that these categories willinclude many people from poor or troublednations, applicants from these parts areoften refused visas. Those who do overstayvisas are s ubj ect t o detention and topenalties which will make it m ore difficultfor them to return to Australia.The human consequences of this policysurface only occasionally at times of publiccontroversy about the face w hich Australiapresents to the world. Many Third Worlddelegates to a conference for the deaf, forexample, were recently refused admissionto Australia.When v isitors and applicants forresidence are evaluated on the economicbenefits they bring and by their readiness toreturn without trouble, on-shore asylumseekers will be strongly discouraged and alllegitimate administrative m eans will beused to exclude and deter them. They willeffectively, if not legally, be regarded aslawbreakers. The initial popular reactionto the detention of asylum seekers is often,'They broke the law, and so theydeserve to be in jail. 'EOR ASYLUM SEEKERS in Australia, the arrivalof the Kosovo refugees has been a mixedblessing. The efforts to make them feelwelcome, particularly by local communitygroups, have been exemplary, and havedrawn attention t o Australia's oftenneglectedaltruistic urge. But the Kosovorefugees have also drawn attention andresources away from oth er needy groups.Indeed, the argument behind the government'sinitial decision not to receive Kosovorefugees had some validity. To offer shelterat such distance is massively expensive,and, in principle, resources would be moreeffectively spent closer to Kosovo.14 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

Perhaps the group mostforgotten are the East Timoreseasylum seekers, m any of whomhave been waiting for certaintyabout their status for six years.While they are no longer anirritant in Australian relationshipswith Indonesia, the chan gein Indonesia and in East Timor,together with the focus on Kosovorefugees, has taken them out ofthe public spotlight. But theyrem ain no less needy or anxious,and their claim for residence isno less pressing than before.The arrival of Kosovorefugees also led the government hurriedly to introducelegislation allowing temporaryresiden ce for refu gees. Thelegisl a tion , w hich did n o treceive the ben efit of communitycon sultation , m ayadversely affect future asylumseekers. While the legislationwas occasioned by the Kosovocrisis, it refl ects a growingin t ern a tiona l inter est inrestricting refugees' access top erman ent residence. Thehuman consequences of suchlegislation lie in the anxiety andlack of motivation that breedwhen people cannot plan fo rtheir future because they maybe sent back to their own landswhen the situation is deem edto have changed. The legislationis therefore of concern.T h e situation of m ostasylum seekers in Australiaremains precarious. Detentionis entrenched, despite its m ani-fest destructiveness. After a few m onths indetention, m ost asylum seekers complainof depression and difficulty in sleeping.This is inevitable when people dealing withloss are deprived of freedom and of thenormal interchanges that ordinarily distractu s from our problem s. In the last twom onths, incidents at Port Hedland andMelbourne have received publicity. In bothcases, the pressures caused by prolongeddetention were a significant factor in theincidents. T he response-transferring thoseresponsible to prison- treats the symptomand not the cause. It also further confirmsthe assumption that asylum seekers arecriminals who have broken laws by comingto Australia and have only to return to theirown lands to be free of their hardship.Inside informationThe following is an extract from a letter by refugee claimants at the MaribyrnongDetention Centre. in which they describe their situation:'The Australian Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs maintains a policywherein those requesting refugee status and asylum seekers arc placed in mandatorydetention. If this policy implied an initial period (e .g. three months), during whichthe Department began or completed the process of determination of each case then,we believe, this period of waiting could be sustained by most without psychologicaldamage. However, for the majority of detainees, the waiting time is much, muchlonger. For some, it extends more than two years and the outcome of such confinementis clearly destructive. Those who formulate these policies rarely, if ever, comeinto contact with any of the people living undcrthcsc conditions. As you know, refugeeshave experienced tragedy, trauma and dispossession of family, friends and country.Consequently, detention places enormous stress on each person with the imposedinactivity, with the outbursts (at times violent) which occur from built-up tensionand with 'flashbacks', reminders from past trauma.'We came to Australia with healthy minds, aware of the upheavals and injusticesin our native countries. We came desperate to find hope for our future. Yet we see thatthe Australian Department of Immigration policy brings about the gradual destructionof our hope. Our world is very much aware of what unemployment can do to peopleof working age. Our question: "Is the Immigration Department aware of whatinactivity in confinement can do to a person?"'The detrimental effects of detention can be verified by officers, doctors, nurses,lawyers, visitors and others who have contact with detainees. The common symptomsarc stress, migraine, depression, insomnia, loss of appetite, inability to concentrate.These arc usually treated with medication and some residents arc sedated, but themajority of detainees refuse to resort to this. While we get medical treatment, theenclosure of the detention centre can only increase the pain and suffering.'A major concern for us is the children. Women have given birth while here andyoung children spend their lives confined within barbed wire fences. We have askedourselves again and again, "Is this the democratic country we thought we werecoming to? " or "Is this a country where the abuse of human rights and the rights of thechild is ignored?" The Department seems to have no understanding of the suffering theycontinue to inflict upon us who arc in fact seeking sanctuary.' -4 August 1999Criminals, how ever, are senten cedbefore they are detained and can lookforward to a defin ed day of release.Meanwhile, the government continues topropose legislation that would limit asylumseekers' access to the courts, a proposalthat has n ot so far won the support of theOpposition .Where asylum seekers are regarded asobjects of control rather than as subjects ofrights, it is to be expected that they will betreated in inhumane ways. The deportationto China of a pregnant wom an who facedforcible abortion on return was the m ostpublicised recent case. Sedation, forcedfeeding, rem oval without warning, and theuse of private security firms to get detaineesback to their country of origin, are som e ofthe other practices that the government hasdefended. Su ch practices have understandablybeen m ade the subject of awide-reaching Senate Inquiry.To com e close to people affected byAustralian refugee policy is often to bedistressed on their behalf. But refugees arethe symptom of the lack of an effectivewill to en sure the equitable distribu tion ofthe world's resources. Refugees normallycome from nations whose share of thew orld's wealth i s diminishing. Theharshness of their reception in developedcountries reflects the desire to protectprivilege.•Andrew Hamilton SJ teaches at the UnitedFaculty of Theology, Melbourne.V OLUME 9 N UMBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 15

negotiate with Sinn Fein over power-sharingarrangements. And, on the proviso that theIrish Constitution was amended to abolisha (symbolic) territorial claim over the sixcounties, they agreed to the Irish Government'staking on a limited role in relationto the province's affairs.All this was done on the premise thatthere would be som e concrete evidencethat, as far as the IRA was concerned, thewar was over. The evidence in that regard ismixed.The British Weekly Telegraph newspaperreported on 7 July that significantIRA members are defecting to splintergroups committed to hiding their weaponsand continuing the violent struggle. TheTelegraph stated that British and Irishsecurity forces (Special Branch, MIS and theIrish Gardai) had intelligence that the IRAhas enough weapons to conduct a full-scalewar for about six months. On 4 August, itreported the seizure of eight consignmentsof gu ns from the US to Ireland, apparentlyheaded for the Northern Irish republicans.Retired Canadian General, John deChastelain, has been appointed to head thedecommissioning body, but in early July hewas able to report to negotiators at StormontCastle that the only paramilitaryorganisation willing to commit itself todisarmament was a splinter Loyalist group.Little if any progress has been made sincethat time. But there has been no reversionto terrorist campaigns by para militaries ofeither side (despite the odd, aberrant acts bybreakaway die-hards).In an attempt to break the deadlockbetween the Unionists and Sinn Fein/IRA,British and Irish PMs, Blair and Ahern,drew up a blueprint, 'The Way Forward', forthe implementation of the Good FridayAgreement. Sinn Fein was to be allowed tojoin the government on 15 July; the IRAwas to commence disarming within weeksand to complete that process by May 2000;the Internati onal Commission onDecommissioning was to set a timetablefor and confirm the commencement ofdecommissioning; and, most significantly,the new government and assembly were tobe suspended by the UK Government ifdecommissioning was not carried outsatisfactorily.There are obvious problems with thisplan. First, it ransoms the future of NorthernIrish elf-government and power-sharing tothe IRA. Second, even if the IRA gi ves anunequivocal pledge to disarm, the dissidentsand splinter groups are not parties to theagreement. Third, there is no fail-safeW .Seeking a way•1 a eALL HAVE DOG-DAYS WHEN, even if we do not go so far as longing to be delivered fromthis body of death, we at least dream of other forms of employment. Accordingly, my hopeswere temporarily raised recently by an article by Gerald Bray in Themelios, a solidperiodical from the Conservative Evangelical school. It was entitled 'Rescuing Theologyfrom the Theologians'. If the prisoner is set free, I mused, its kidnappers might also be freeto do something more interesting.It was an enjoyable read: Bray echoed my prejudices. He wants theologically informedpreaching that decently conceals its academic plumbing: 'I have a personal rule aboutthis-if a preacher refers to the "meaning of the Greek" during the sermon, there is troubleahead.' His main concern, however, was to insist that the task of theology is to articulatethe faith of the church, and not to present a smorgasbord from it or to make compost outof it for a secular flower bed.So far, so good. The difficulty comes, however, when we try to say with any precisionhow theologians will serve the church properly with their work. Recent periodicals, whichdisplay multifarious ways of doing theology, underline the difficulty.Some theologians, for example, are concerned to speak out of the Gospel to theirculture. The most recent copy of Interpretation (April 1999), with the resounding title'Apocalypse 2000' takes up the way in which the structure and imagery of the Book of theApocalypse has helped shape cultural expectations and political rhetoric in the UnitedStates. It has provided a language and imagery for reflecting on the social hopes anddiscontents of different ages. The article shows, incidentally, how malign can be the resultswhen churches assume that they have access to the meaning of Biblical texts withoutrecourse to critical enquiry.In contrast to this work of exposition, the notable Croatian-born theologian MiroslavVol£ reflects from a Christian perspective on the formative metaphors of social life(Concilium 1999/2). In his work, Volf has built a theology around the great them es ofreconciliation and inclusion. In this article he examines the metaphor of the contract, onewhich emphasises freedom of individual choice. But it also encourages a view of ocialrelationship as shallow and impermanent. Vol£ is more enthusiastic about the recent useof covenant as a central metaphor, but points out that in Christian terms covenant isinseparably linked to sacrifice and costly love. These extend beyond inclusion to embrace.Other theologians reflect on life within the churches. They meet the paradox that tobuild and understand life within a tradition, you need to go outside it. In Studio Liturgica(1999/lL for example, Eugene Brand discusses Lutheran liturgical reform in the UnitedStates. He makes the obvious but easily missed point that in developing liturgy in English,the Lutherans inevitably had to draw on the experience, ritual and language of otherchurches. He shows, too, how more recent liturgical reform in the Catholic Church hasnecessarily been done ecumenically.Nevertheless, theologians properly reflect on the practice of their own churche . In theNew Theology Review (May 1999), Michael Lawler presents ten theses on divorce andremarriage. He is concerned with the sad exclusion from communion of so many divorcedand remarried Catholics. Since Luther's time, theses, whether nailed to doors or not, havehad a combative and controversial edge. These are no exception, for Lawler addresses headonthe theological justifications for exclusion. These include the arguments that the handsof the church are tied because Jesus forbade divorce and remarriage, that the practice of thechurch has always excluded it, and that the risk of scandal forbids the divorced and remarriedfrom being admitted to communion. Lawler argues that in the N ew Te tament there arediverse teachings about marriage and divorce, that early church practice shows no sign ofhands being tied, and that the current Catholic attitudes have developed through historicalcontingency, and sometimes inconsistently. On this base, he argues for pastoral flexibility.I would argue that in his theses Lawler perhaps overplays his historical hand. But hisarticle provides an example of a theologian properly at work articulating the faith of thechurch. The evils caused by exclusion from the sacraments are so great that conventionalwisdom needs to be sifted in robust discussion.•Andrew Hamilton SJ teaches at the United Faculty of Theology, Melbourne.V oLUME 9 NuMBER 7 • EUREKA STREET 17

system of accounting for the IRA'sweaponry, so that there can be no realconfidence in the disarmament processunless large amounts of ordnan ce arepublicly exposed and 'decommissioned'.The plan was rejected by the Unionists.But to focus on the problems is to denythe reality that for two years the IRA/SinnFein position on cease£ ire has demonstrablybeen that they are committed to thecons ti tu tiona! process-all republicanterrorism since the ceasefire was announcedhas apparently been committed bybreakaway groups.It is too much to expect that loyalistsand republicans will embrace each other, atleast for the foreseeable future. But, as thepeople of Northern Ireland become used topeace, they will surely demand constitutional,democratic solutions to theirproblems, rather than a resumption oflow-grade civil war. The benefits of peaceare already being experienced. There is nofuture in armed struggle. It is hard to trustand compromise with an armed enemytheIRA should take the high moral groundand begin to disarm. -Hugh DillonCold comfortL ERE WAS AN AIR of expectancy on the daythe first Kosovo refugees were due to arrivein Australia. The hourly radio news serviceupdated their progress through the skiesfrom the other side of the globe. Sensitiveto the health needs and cultural beliefs ofour gu ests, Qantas served no fruit juice oralcohol on the trip. The movies shown onboard were carefully selected to be light andfunny- no drama or war scenes.Preparations on the ground seemed noless considerate. The reception was thoughtfullylow key-a short informal welcome atthe airport by the Prime Minister and hiswife, without intrusion from the press.Local communities were briefed abouttheir new neighbours. Halal m eat wasarranged. Community interpreters wererecruited and trauma counsellors provided,not only for the refugees but also to debriefthe interpreters coping with too many talesof human misery. Australia might be faraway, but could be relied upon to hostpeople deserving of the world's care andsupport.But then radio news bulletins began toreport on negotiations with Kosovo'protesters' refusing to leave the buses whichhad transported them to the Singletonbarracks in NSW. Their unequivocaldegree winter temperaturesof 'sunny Australia'. And topeople from Kosovo with awell-founded fear of perilouscold, the heating arrangementsseemed remarkablycasual. Then there was theproblem of privacy-paperthinwalls made a nightcough a shared event and thecommunal shower blocksoffended reasonable requirementsof modesty.A cynical interpretationof these makeshift arrangementswould be that itcommunicated the nonetoo-subtlemessage thatAustralia was a 'temporarydemand was to return to the more congenialSydney reception centre. For a nation whichhad recognised and defended the right tostrike as a legitimate form of political action,our response was remarkably punitive. The'rebels' were refused food and water whilethey stayed on the buses. After a torrid 31hours, only a small family of three, includinga frail 74-year-old grandm other, remainedsteadfast, refusing to budge.The list of grievances about conditionsat the Singleton camp were, by any objectivecriteria, reasonable. The army had longceased housing its robust young 18- 21-yearoldrecruits there except for weekendbivouacs-the living conditions were tooprimitive. The toilet and shower blockswere some 100 metres from the barracks,too far for the elderly, young and sick totrek, especially at night-time in the tworeciprocityhere preserve the form, but notthe spirit, of hospitali ty-you 'shout' around of drinks in the expectation that yourmates will do likewise imm ediately. Theunderstanding is that you might 'bring aplate', but always 'grog', if invited to dinner.Such rigid co-obligations are surprising forso affluent a society where there is littlerisk of eating (or drinking) your hosts 'out ofhouse and h ome'.Australians are not deliberately coldhearted.But we set cultural store by puttingup with hardship. Floods, fire and droughtare meant to be borne with stoicforbearance.With obvious machismo, Senator JohnTierney rushed to the Singleton army base,bounced up and down on the beds anddeclared that he found the room so hot hehad to turn the heating down. 'The showersare outside, all right,' he chuckled. 'It's a bitlike a caravan park.' TheAustralian standard is theable-bodied bloke, not the--~~t Q h .~rtilhaven', not a comfortable permanent'hom e'. The government's generosity wasalso politically cautious-the refu geesshould not be seen to be queue-jumping forresources inadequately provided to disadvantagednationals. There was a 'budget'for this humanitarian venture. Dollars, notthe needs of people, determined the qualityof services and facilities.How do we make sense of this publicmean-spiritedness in a culture which pridesitself on its friendliness and willingness tohelp others? An anthropologist, for example,might conclude that, judged by worldstandards, Australian culture is notparticularly hospitable. In many societies,the obligation of the 'host' is to provide thevery best to a 'guest', even at considerablepersonal sacrifice. The honour of the host,the family and 'tribe' depends upon it. Bycontrast, Australians have cultivatedindividualist self-sufficiency. The rules ofweak and vulnerable.Some of these dominantcultural ideals might havebeen functional in a harshnew environment. Othersmay even be understandableas part of the value system ofa former (and predominantlymale) penal colony. Thepersistence of such normsdespite massive immigration,however, says much aboutthe superficiality of ourmuch-lauded cultural fl exibility.Positive values suchas the long-standing Australian concerns with social justice and equityare imperilled if our generosity is arbitrarilyconfined to helping those we define as'mates' because they share our own values.There was som ething shameful and uglyin our unsympathetic response towardpeople forced into the unenviable role ofreluctant gu ests. We have cause to beembarrassed. But there is a positive in allthis: as our multicultural experiencerepeatedly demonstrates, encounters withother ways of seeing the world provideuseful opportunities to learn a little moreabout ourselves.-Kathy LasterThis month's contributors: Edm undCampion is an emeritus professor of theCatholic Institute of Sydney; Hugh Dillon'spaternal grandfather claimed to be an IRAvolunteer in the 1920s; Kathy Laster teacheslaw and legal studies at LaTrobe University.18 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

Of fertility, Inotility and abilityA NY UNG,

The state of VictoriaIVictoriaAmid football fina ls, the spring racing carnival and the opening of the new tollway system,is heading for elections. Moira Rayner looks at the condition of democracy andcivil liberties in Premier Jeffrey Kennett's 'Victoria on the Move'.FF KENNETT's popularity has never been of the Bolte years, and the small '1', social- cosying, though critics are quickly labelledhigher, especially among young voters and democratic liberalism of Hamer and Cain. disloyal, selfish and un-Victorian, andyoung males in particular, in the newer Victoria was the cradle of a liberalism which dismissed. His government's willingnessouter suburbs of Melbourne. His has been a used state intervention to achieve equality to seek out major events, such as the Grandremarkable metamorphosis. Even as he led of opportunity, so important to liberal Prix, and create new projects, such as thethe coalition to its massive landslide into philosophers such as John Stuart Mill. Since Docklands stadium, City Link and Crowngovernment in 1992, Kennett was widely 1992 that public infrastructure, established Casino, has invigorated business (and aseen as a clumsy, impulsive politician, pronecertain chauvinism). The Victorian premierto gaffes, personal abuse and intemperatehas also embraced multiculturalism (one ofgestures. (He would rather we forget hishis most attractive acts was his genuineinfamous mobile phone conversation withrejection of One Nation policies), supportedAndrew Peacock in which he described hismoves to liberalise laws to allow the termipoliticalcolleague, John Howard, in four-nally ill to die with dignity, and (off and on)letter words, and his repeated interjectionsadvocated drug law reform. He is,when Joan Kirner, then Minister, spoke inT of course, a minimalist republican.the Victorian parliament, that she was a'stupid woman'.) Even as her LaborEMOSTPROFOuNoeffectsofthe Kennettadministration was definitively rejected byreign, however, strike at the heart of goodthe people, in 1992 Joan Kirner was still bygovernance. These transformations arefar the people's preferred premier.complete and probably cannot be undone.Now, as the celebrity premier, with hisIn the name of small government, freecarefullycrafted 'rough-diamond' mediamarket policies, and individual choice, noimage, heads into his third electoral contest,area-not even justice-h as been leftand an undoubted third win, it is hard tountouched. Paradoxically, the effect has beenrecall (and younger voters simply don't)an increase in central government controlthat this was the man dismissed as aand regulation, largely under the personal'boofhead' in the '80s and a buffoon in thecontrol of the premier himself. Even the'90s. The Teflon premier personifies hisheads of the departments report not to theirgovernment, thriving despite scandals,ministers, but to the premier, personally.professional opposition and popular protestThe greatest changes came quickly, asat the wholesale changes wrought, in justthe new administration cashed in on theseven years, in the structures of govern-atmosphere of 'crisis' which it could blameance. He has effectively silenced his critics, over 150 years of conservative administra- on Labor. But benefits-such as theboth within and outside his government tors (Labor governed for just 19 years in all) minimisation of state debt through publicandhisparty.Hehasnoheirapparent:there has been dismantled. The 'conservative' asset sales and the efficiencies ofis no sign that he has any plans, or another social and political culture which saw privatisation, corporatisation and restrucplace,to go . Jeff Kennett's face is an icon, as Melbourne described as 'grim city', the turing of the public sector-have come atNicholas Economou and Brian Costar home of Protestant wowsers and a bastion the cost of accountability.remark in their introduction to The Kennett of social conservatism, has gone with it. The changes to the public sector and toRevolution (UNSW Press, 1999), of 'the It is timely to review what Kennett has industrial relations have been immense. Inmost robust example of the way the Liberal wrought. reframing the employment market, forParty of Australia's approach to govern- The most obvious change is the example, Victoria abolished the old awardment and politics altered under the personification of government in one man. system and Industrial Relations Commisinfluenceof neo-classical liberalism'. Victoria has a new verb: to be ' jeffed'. Jeff's sion in 1993, then simply handed over itsAs Costar and Economou write, the foibles, now he is so powerful, seem amusing, own new system to the Commonwealth inVictoria of 1999 has thoroughly cast off reportable, and almost endearing. The 1997. In the process, it abolished its owntraditionalliberalism, both the paternalism bullying tone has softened into cajoling and (not particu lar! y tame) creature, the20 EUREKA STREET • SEPTEMBER 1999

Employee Relations Commission, anddismissed its Commissioners, for a secondtime. ERC President, Susan Zeitz, was notappointed to the federal body-a breach ofthe doctrine which requires judicial officersto be appointed to equivalen t office in orderto maintain tenure and the public interestin judicial independence. But th e Kennettgovernment has been characterised by awillingness to eliminate statutory andjudicial watchdogs on its activities.The government has dealt with 'justice'with the same policies it has used in all itsother reform s. It has abolished independentoffices, such as the Law Reform Commission,and removed the inconvenien t powers(and sometimes the incumbents) of officessuch as the Director of Public Prosecutions.It has privatised 'justice' m echanisms, suchas prisons (leading to a 1999 coronia! inqueston excessive deaths in custody in the PortPhilip prison), chipped away the jurisdictionof the Suprem e Court (and cut out access tojudicial review entirely, in some notoriouscases), and in creased access costs andobstacles to administrative tribunals.But the greatest change is to Victoriansociety. The introduction of a gamblingculture has had a detrimental effect both onthe econom y (now reliant on its gamblingrevenue) and on social well-being, as therecent Productivity Commission Report hasrevealed. The restructuring of local government, and ch anges in the n ature andavailability of community services-healthcare and state education, particularlychan ged the r ole of n on-governmentorganisations and their capacity to advocatethe interests of the disadvantaged.This has all been possible because of the1992 election, which handed over controlof both houses of parliam ent to the executive.Without an effective opposition, withlimitation s on freedom of info rmation andthe right to seek judicial review of administrativeaction, with the growing use of'commercial-in-confidence' exemptions tothe duty to disclose public expenditure, andwith the gutting of the office of AuditorGeneral, there is now virtually no check onexecutive power in Victoria. This isunhealthy for representative dem ocracy,and is certain, over time, to lead to abuse.One of the greatest casu alties of the lastseven years has been the status and influenceof t h e m edia. Politician s m ust b eaccountable and not just through elections.Since the Victorian parliam ent no longerprovides a check on administration, the'watchdog' role of the m edia, scrutinisinggovernment's daily activities and thepolitical process, b ecomes far moreimportant. But in this, Victoria's mediah ave been remarkably ineffectual. Them assaging of th e message through publicrelations, entertainment and the advertisingfocus of the administration-the premierused to be in advertising-has been brilliant.As the new premier, Jeff Kennett justrefused to deal with journalists he regardedas not on side. In one 1994 ABC televisionreport, ABC journalist Ian Campbell shotfootage of a sad little group of reportersreduced, in their search for comment onm atters of the day, to h anging out in th eanteroom of commercial radio station3AW, scribbling notes as a loudspeakertransmitted a Kennett interview withthat station's N eil Mitchell-a scenereminiscent of Queensland premier JohBjelke-Petersen's 'chooks' scrabbling for afew grains of news. T h e media's impotencewas perhaps sym bolised by the very publiccollapse on Channel 7 by an upset anchorwoman,Jill Singer, imm ediately after sheannounced that a profiled story on MrKennett's share-dealings had been pulledm om ents before she went on air. She latergave sworn evidence that this was afterdirect intervention from the premier withstation m anagem ent.Both the m ajor Melbourne daily papershave broken stori es which, if the peoplehad reacted, could have destroyed theKennett government. Each has revealedscandals at the h eart of governmentprobity-the tendering process fo r thecasino, the detrimental effects of the newgambling culture, child protection scandals,ministerial m isuse of government creditcards, extraordinary share-dealings, andeven gross, person al ministerial m isbehaviour.Yet whatever they reported, thepublic either wasn't listening, or couldn'tbe influenced.This was a true achievem ent, within sosh ort a time. It h as been t emporallyassociated, perhaps coincidentally, withchanges in The Age, once a quality broadsheetwhich has seen several changes ineditorial direction and today has a ' tabloid'feel, a 'lifes tyle' em phasis, and a sinkingcirculation .What are we left with? A can -do,ideologically driven, undoubtedly efficien t,cen tralised, authoritarian an d, for th em om ent, unchallengeable executive whoseethos is wrapped up in the personalitypackaging of just one m an .•Moira Rayner is a lawyer and freelancejournalist.+The Inaugurallgnatian Forumconducted byJ esuit Social ServicesMelbourne's Drug Dilemma:Harm Minimisation orControl?The Lord Mayor of MelbourneThe Rt. Hon. P e t e r CostiganandBernie GearyJ esuit Social Services Program DirectorPremier's Drug Advisory Council MemberArchbishop Pel/'s Drug PolicyCommittee MemberThursday, 16 September 19997.30 pm-9.30 pmSt Ignatius School Hall326 Church <strong>Street</strong>, Richmond(Parking available behind church)Entr ance by donation:$10 adult, $5 concession/studentFor furth er infor mation, contact:John AllenDevelopmen t ManagerJ esuit Social ServicesTel: (03) 9427 7388The Centre for ChristianSpiritualityPrincipal: Bishop David WalkerAssociate Member institute of the SydneyCollege of DivinityDistance Education Programs inTheology and Spiritualityincluding:Certificate in Theology (SCD)Bachelor of Theology (SCD)Gradu ate Diploma in Chri sti anSpirituali ty (SCD)Master of Arts in Theological Studies(SCD)The Centre also offers casual Bed/Breakfast accommodati on and confere ncefac ilities in the heart of Randwick.Further Information:The AdmjnistratorPO Box 20 1,Rand wick, 203 1Ph: (02)939822 1 I,Fax: (02)93995228Email : centre@ intern et-australi a.comVoLUME 9 NuMB ER 7 • EUREKA STREET 21

C ENTENARYSir Franl