1 - Eureka Street

1 - Eureka Street

1 - Eureka Street

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

~ LORETO ~ ,~ , ~~,:: : 11,;: , Hal lOpen DayA r-eal day rn the school. Prep to Year 12.Wednesday November I. 1995 9am - 3.30pmVCE Art ExhibitionOfficral Opening of the VCE Ar-t ExhibitionWednesday November I. 19953.30pm- 4.30pm.Exhrbrtron dates: I, 2 & 3 November· 19959am - 3.30pm in Senror- GymnasrumFR WILLIAM JOHNSTON SJSpend a day w ith well-known Irish j esu it,Fr William j oh nston SJ, lectu rer at SophiaUniversity in Tokyo, author on prayer, andexpert on Christi an-B uddhist dialogue.Melbourne:Sunday 26 November 1995 11 am - 4pm.BYO lun ch. Xav ier Coll ege Kew(enter via Charles <strong>Street</strong>),$10 or donation.Further information: Jim Slattery (03 ) 98822977, Gerard Murnane (05 3) 361793or Nick Galante (03) 9853 2346Sydney:Saturday 9th December 1995 1 0.30am - 4pm.BYO lunch. St Ignatius College Riverview,$10 donation. Further information:(02) 882 8232 CLC Officeor Mark Diggi ns (02 ) 418 639 1Presented by Christian Life Community_PSYCHOLOGYcJPINIFEXBeyond Psychoppression:A Feminist Alternative TherapyBetty McLellanOne of Australia's most highlyrespected feminist therapists examinesthe tense relationship between feminismand psychotherapy.ISBN 1 875559 33 7 pb $24.95Will to Violence:The Politics of Personal BehaviourSusanne KappelerEloquent and passionate. A powerful critique of thestructural forces that control our relationships.ISBN 1 875559 45 0 HB $39.95 • ISBN 1 875559 46 9 pb $24 .95Tel. 03 9329 6088 • Fax 03 9329 9238504 Queensberry St (PO Box 212). North Melbourne. Victoria 30512 EUREKA STREET • O cTOBER 1995

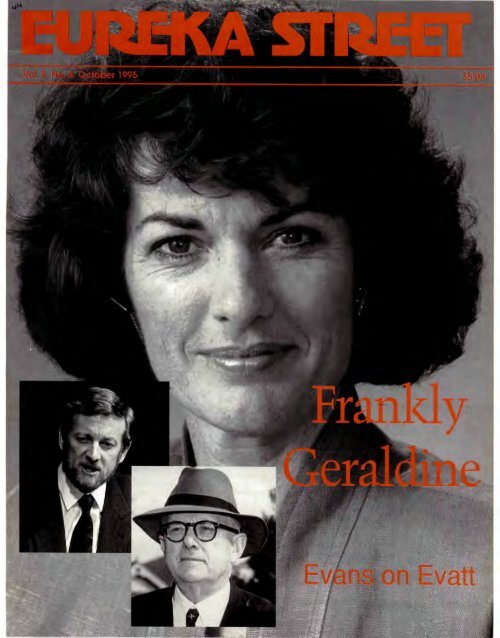

Volume 5 Number 8October 1995A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theologyCover: Geraldine Doogue,Gareth Evans and H.V. Evatt.Graphics pp7, 12, 13, 17, 23, 35-36,42-43, 48-49, 51, 54, 57 bySiobhan jacksonCartoon p6, by Dea n Moore.Cartoon p60, by Peter FraserEurel< o <strong>Street</strong> maga zineJesuit PublicationsPO Box 553Richmond V1C 3 12 1T el (03 )9427 73 11Fax (03)9428 4450CoNTENTS4COMMENT7TAKING LIBERTIESD enis Minns on tolerance.8LETTERS11CAPITAL LETTER12NEITHER A BORROWERNOR A LENDER BEBill Garner on the fate of public libraries.15ARCHIMEDES16HOME TRUTHSMoira Rayner18FRANKLY GERALDINEGeraldine Doogu e gives the Church alecture.23RIGHT ON TRACKPeter Pierce picks them at Rosehill.24REPORTSJim Davidson meets som eindependent thinkers.Jam es Griffin reviews AustralianFilipino relations (p25).26EVANS ON EVATTGareth Evans commemorates H.V. Evatt36STORIESGerard Windsor ponders anti-Semitisismin MTs Laszlo's torte; Trevor Hayrecalls a Ukrainian friendship in SomeDesolate Shade (p42).40NEWMAN IN MANUSCRIPTEdmund Campion reflects on the lifeof John H enry N ewman in the light ofnew manuscript discoveries.48BOOKSPeter Steele reviews two books of discovery,Gm at Southem Landings : AnAnthology of Antipodean Twvel, JanBassett (ed.) and The OxfoTd Book ofExplmation, Robin Hanbury-Tenison(ed.) (p48); Max Charlesworth fossicksin The Modem Catholic Encyclopedia,Richard P. McBrien (eel.) and Encyclopediaof Catholicism, Mich ael Glazierand Monika H ellwig (eds) (p50); JimDavidson reviews N elson Manclela'sau tobiography Long Wall< to FTeedom(p52); Ray Cassin lists the Eleven SavingViTtues, Ross Fitzgerald (ed. ) (p54) .55OPERABruce Williams reviews the CharnberMade Opera production Th e Bunow.57THEATREGeoffrey Milne goes all over theAustralian theatrical shop.59FLASH IN THE PLANReviews of the films: W ateTwmld, Th eSepawtion, That Eye, Th e Shy,D'Artagnan's DaughteT, All Men AmLims, Exotica, Nine Months and TheConfmmist.in the 1995 Daniel Mannix Lecture. 62WATCHING BRIEF34NEW POETRY63Poem s by Peter Porter, Peter Steele SPECIFIC LEVITY(pp39 & 45 ), and Jack Hibberd (p46).V OLUME 5 N UMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 3

C OMMENT: 1A magazine of public affairs, the artsand theologyPublisherMi chael H. Kell y SJEditorMorag FraserConsulting editorMic hael McGirr SJAssistant edito rJon GreenawayProdu ctio n assistants:Paul Fyfe SJ, Juliette Hughes,Catriona Jackson, C hris Jenkins SJ,Paul Ormonde, Tim Stoney,Siobhan Jackson, Dan Disn eyContributing editorsAdelaide: Greg O'Kell y SJBrisbane: Ian Howells SJPerth: Dea n MooreSydney: Edmund Campion, Andrew Riemer,Gerard WindsorEuropea n co rrespondent: Damien SimonisEdi torial boa rdPeter L'Estrange SJ (chair),Marga ret Coady, Marga ret Coffey,Valda M. Ward RSM, Trevor Hales,Marie joyce, Kevin McDonald,Jane Kelly IBVM,Peter Steele SJ, Bill Uren SJBusiness manage r: Sy lva na Sca nnapi egoAdvertising rep resentative: Tim StoneyPatrons<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> gratefully acknowledges thesupport of Colin and Angela C

libraries. Part of the secret is to have a peppering ofbig names. This year the drawcard is Ruth Rendell,whose visit is funded by two publishers, the BritishCouncil and the festival itself. 'She'll fill any hall sowe'll do anything to get her,' ays Clews. Some of thebig nam es, however, are notoriously elusive.'Every year, for many years, we've sent a letterto Susan Sontag saying please come to the nextfestival. She's written back saying she couldn't possiblycome on only twelve m onths' notice. So w e gotclever and invited her to come in two years' time.She tol d us that she couldn't possibly plan so farahead.'Clews has also been keen to attract IsabelAllende.'Apparently she m akes decisions based on herdreams. So her publishers sent her a great delivery ofAustralian fluffy toys, thinking that if she went tosleep with a stuffed koala sh e might dream ofAustralia and com e h ere.'Brisbane's Warana Writers' Week, also held inOctober, is not similarly laced with overseas visitors.According to its director, Wendy Mea d, Warana simplyhasn 't got access to the support that would makethis possible. 'We don't get much h elp from the publishers because they are mostly based in Sydney andMelbourne, ' she says.'There is another side, however. They must beaware down south that most of the young literary prizewinners come from Queensland. Three of the last fourVogel winners are from here. We're proud of our regionalwriters and are quite consciously celebratingthem.'When Mead took over the 1994 program , shebrought to the job 20 years' experience in arts administration.She is aware of a challenge in maintainingthe relaxed atmosphere of Warana while keeping visitingwriters on their m ettle.Australian writers' festivals steer a middle coursebetween the two styles which predominate overseas.At the Toronto festival, apparently, writers wait backstagebefore the curtain rises and they go out to do areading like a singer performing an aria. The readerand writer don' t intersect . But there are otherextrem es: Clews found himself this year at the celebratedHay-on -Wye festival in England and wasastonished at how slap-dash it was.'We sat in badly erected tents which were blowingeverywhere in an English summer ga le. TheWomen's Institute had spelt out "Hay-on-Wye-Literary-Festival"in ivy across the back of the tent.' Clewesmight have added what <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>'s editor learnedwhen sh e visi ted it this year: Hay-on-Wye has a fewproblem s adapting to the literary tourists. The 'foreigners'who descend in their thousands to spend timeand money in this tiny village with its famous bookshopsare treated like carriers of a mild form of BlackDeath, and quarantined, as far as possible, in thewindy tents in the paddocks. Don't bother asking thelocal fo r directions!Australian festivals, by contrast, are amiable,often casual occasions. 'We're trying to bring readersand writers together in a way that makes them bothhappy,' says Wendy Mead.Many people do com e to gawk at their favouritewriters. But there's more. Clews says that people whocome for facile reasons som etimes make importantdiscoveries.He speaks of the difficult but important task thisyear of devising panels that deal with history, withthe responsibility of writers and the interplay betweenfact and fiction. These are issues that continue to burn,both in n ewspapers and in books.•Michael McGirr is Eumka Sueet's consulting editor.C OMMENT: 2D OROTHY L EEMissing the pointIT WAS A WARM wee OMc lot " cold Ftidoy night inwinter. A procession of wom en escorted the Professorin. When she reached the front of the hall, a folk-singersang a welcome and a dancer danced, celebrating women's spiritual and theological awakening-an awakening symbolised in the unassuming figure ofElisabeth Schl.issler Fiorenza, Professor of Divinity atHarvard Divinity School, and author of In memory ofher:A feminist theological reconstruction of clJiistianorigins ( 1984), now a classic of ch ristian feminism.After such a beginning, the lecture itself was ananti-climax: prosaic and hard work. The audience,m ainly women, filling the large lecture theatre of thePharmacy College and spilling upwards to the balcony,listened with grave attention, wending their waythrough long sentences, heaped-up

ca tive structures of oppression', the vision n everthelessemerged for the patient Listener: a vision of a communitycommitted to libera ti on a nd radic.:ddemocracy, without hierarchy or priestly caste orstructures of subordination.For Professor Schi.issler Fiorenza, this vision wasgrounded in the notion of a 'discipleship of equals'which, she argued, lies at the heart of the basileia(the kingdom of God) in the teaching of Jesus of Nazareth.As a Jew among Jews, Jesus formed a movementaround him which included women, the poor, and theoutcasts of society. Equ.J lity and inclusiveness werethe key features of the Jesu s-movem ent. Its challenge5A'1- W ~'< D6t-l'-r WE:Po 5oM f. " SUPRE.!V\~s"COVf..Q.S ?'-.:: .'· 0~,~ fv\D ~was directed agai nst the structures and ethos of Romanimperialism, down to and including the patri

feminist theological discourse) and CatherineLaCugna (God for us.: The Trinity and christian life)have presented the same vision of mutuality and liberationin more personal terms. At the centre of theirwritings is a transformed understanding of the classicalchristian doctrine of the Trinity. For them Godrepresents a communion of persons, a profoundly personalinter-relationship without hierarchy or domination.The language these feminist writers have usedto describe this trinitarian God-all of it ultimatelyinadequate-draws on feminine as well as masculineimagery: God as Mother, God as Lady Wisdom, Hostess,Nourisher. In this alternative feminist vision,Jesus of Nazareth is not just the founder of the movement,but also its living heart. In Jesus, God has becomehuman, ga thering the whole creation intowholeness and freedom, into the love and mutualitythat already exists in God. In this interpretation, Jesusis not just one among m any, and his vision is notUtopian. Jesus of Nazareth represents the incarnationof God, the entry of the Creator into creation. Hisdeath and resurrection are the key-stones of the basileia,the means by which God's beneficent reigncomes to birth: through pain and struggle, throughdeath to life.Without such an understanding of divine presencein creation, Schussler Fiorenza's theological vision,however attractive, finally leaves us at astand-still. The 'dangerous m emory' vanishes, becauseits heart has been cut out, that deep centre sustainingpassion and feeding hope. There are more waysthan one to destroy a m emory: totalitarian structuresand hierarchical caste-systems have undeniably hada spectacular success rate. Yet, by letting go the centreand starving ourselves of the rich content, weemploy a less dramatic but equally effective m eansof achieving the sa me thing: enfeebling the memoryuntil it fades into a desert of ideality and wishfulthinking. Patriarchal, kyriarchal, and hierarchicalstructures unquestionably need to be replaced in thechurch by openness, mutuality, and the sharing ofpower. However, only a belief in the humanity of Godrevealed uniquely in Jesus can establish the basileiain mutuality and intimacy. In the end, women [andm en) need a realistic vision and a living movementgrounded in incarnation, paschal mystery and anembodied spirituality.Professor Schussler Fiorenza has no place for theologyin this sense, no time for the rich resources thatspirituality brings to women's struggle for freedomand elf-esteem . The singing and dancing at the beginningof the session, to m y mind, articulated thatlively, poetic incarnate heart of the gospel which, forall its worth, was ultimately lacking in the lectureitself.•Dorothy Lee is Uniting Church Minister and a biblicalscholar.LTal

LettersHate mailFrom Noel TurnbullPaul Ormonde (Septe mbe r) is characteristicallyperceptive in raising theissue of why Oliver Cromwell 'seem sto remain in Irish m emory even morestrongly and bitterly than the famine'.The question of why Cromwell isso hated - partic ularly when comparedwith any numbe r of Englishmonarchs- has been the s ubject ofmuch research by Toby Barnard.A short summary of his work canbe found in Images of OliverCromwell: Essays for and by Roge1Howell fnr, cdi ted by R.C. Richcmison(Manchester University Press 1993).It seem s probable that the uniquelyvenomous view of Cromwell dateslargely from the 19th century andappears to be a product of the uses towhich the works of Prendergast, Leckyand Froudc were put. The Unionistspro jected their own contemporaryagenda on to Cromwell and provokedan unsurprising reaction.Cromwell was only in Ireland from15 Augu st 1649 to 29 May 1650. Withoutjustifying Drogheda one cannothelp but wonder with Barnard whyCromwell- rathe r than Grey, Essex,Sidney, Mountjoy, Schomberg, Ginkel,Duff or Humbcrt-came to personifyEnglish oppression .As I mentioned to Pa ul Ormonderecently, the most hated Cromwelliancontempo rary was probably Ormonde!fames BuLleT, Dul

T his m outh,courtesy of Pengu in Books,the writer of each let ter wepublish w ill receive, w ithn o offence intended,a copy ofThe Idiotby Fyodor Dostoyevsky.Penguin C lassics,RRP $10.95High Court to recognise that decisionsm ade by persons w it h Iris h backgroundshave shaped Australi an society.Henry B. Hi ggins, Irish-born ofpoor non-Catholic parents, altered therelatio ns hip between capi ta l andlabour when he adopted the ethicalcon cpt of the basic wage.His decision as Presid ent of theArb itrati on Court in 1907 in Th e HarvesterCase when he looked to theneeds of a fa m ily in fixing a wagechanged Australi an society.Exa mples are available fro m ourwri ters, teachers, academi cs, journalists,union leaders, social reformersand indeed all professions.As to finan ce, apart fro m thenumerous ban kers and financiers ofIrish origin one ca n easily point to them em bers of p ublic admin is trationsuch a Sir Henry Sheehan, the son ofa railway worker whose parents migratedfrom Cork. He became ccretaryto the T reasury 1932 and Governor ofthe Commonwealth Ba n k 1938.Bu t, perh aps th e greatest influenceof the Irish immigran t was their habitof entering into so-called ' mixed marriages'so lamented by Bishop Carr inhis reports to the Vatican. Despite theCa t ho I ic hierarchy adopting a moresevere approach to the 'la mentableabuse' than that recom mended fro mRome, the practice continued. Scratcha third-generation Austra lian with anEnglish, Scottish, Italian or Germanname and wi th a bit of luck you'll fi ndan Irish grandmother.Vivian HillDrysdale, VICNot my typeFrom fohn W. DoyleM any popular books printed fortyyea rs ago and more are easier to readthan contemporary ones of the samekind from the sa me publishers.Part of the expla nation m ay betypologica l: in the older books lineswere often et more widely apart, withmore even spacing between words anda thin space bet ween pun ctuationmarks and the words they followed. Inrecent publica tions, colons and fu llstops ca n be almost invisible and quot

haves and have nots which make secu rity, o nce an a bstract noun, a hugeindus try toda y. C reed a nd its s hadow,poverty, t hreate n the qua lity of life ofthis a nd future gen e rations whose inheritancewill be a de ple te d e n viron ment, m esses of dangerous waste,deple ted forms of li fe, so that s urvivalw i II need to be sought before the re canbe quality of life.Austra li a n poverty is the problemrecently documented by Bob Gregory'sdi scussio n pa pe r o n the widening gapin Aus tra li a be tween the rich and thepoor: The M acro Economy and 1 heGrowt h of G lw t lOs and Urban Povert yin Aus tralia (A ddress to the NationalPress C lub, April 26 1995).It is worth wondering why the twothoughtful world summits, the Gen e ra l Congrega tion of the Jes u its andt h e United Nations, cam e to diffe rentconclus io n s or didn ' t join forces.Could it be that the social environment of t h e jesuits le d the m to a particulardiagnosis/ T h e more we studypeople

The man behind the curtainA cmiou'fatali'm app

Vi EWPOINTNeither a borrower,nor a lender beBill Garner looks at new regimes for public librariescurious andunfortunate characteristic: T hey arenatural victims. They attract violence.T his has been going on fo r atleast four thousand years. In LlllCertaintimes, libraries try to li e lowand stay very still, but it doesn'twork. They alw

for Mr Kennett to think of postponingthe return of even limiteddem ocracy t o M elbourne C ityCouncil. That it was a notion fromwhich he backed away can give littlecomfort. For him, democracy hasclea rly become sonl.Cthingyou can take orleave.But the libraries issueis especially closelyintertwined with thereform of local govern- - -rJ.--"m ent because it was viathe dem ocratic machineryof municipalgovernment that thefree lending librarieswere introduced in thefirst place. And withoutthat machinery inplace the libraries arel eft undefend edexceptby direct action.Business som etim.es de li versservices effi ciently. But one thingthat business is not efficient at deliveringis democracy. At the Victorianlevel, life under the Commissionershas demonstrated that beyonddoubt. The democratic conceptof 'representation' is rarelyfound in their statements of purpose.In the city of Port Phillip itdoesn't even feature in the new electoralproposals. It just doesn 't fitinto the preferred model of a 'boardof directors' running an enterpriseservicing 'clients'. Commissionersput forward artificially manipulated'consultation' processes as a sop, butthat has now been revealedNfor the charade it is.0 1T H ERE REA LL Y IS a COntradictiOn he re. And yet de m ocra cyremains, at least in lip service, thebasic value system in Australia. Ithas certainly been, until now, anideology to which all parties are com mitted. Has the citizenry voted for achange to this?It has been an axiom of democracythat it requires an informed citizenry.Free access to public lendinglibrari es has become a prime indi catorof a functioning democracy. Theyhave becom e repositories of dem ocratic wi dom and an expr sion ofdemocracy in action.Together with free public ccluca-.iif:7:.=:1!;z,:;r.;,~:~...-...,.;;;~~.. tribute to the developmentof democratic principles' .But, what was obvious in1976 is no longer obvious.The immedia tc question,however, is: will tenderingout the function of librariansenhance cxisti ng libraryservices or will it, by theapplication of commercialcriteria to library operations, inevi tably lead to further privatisation,restrictive managem ent practice, andthe global imposition of user-pa ys?By what right do people questionthe government in this matter ? Theyvoted them in. Democracy issa tisfi ed, at least at the statelevel. At the municipal levelit is, dem onstrably, a withdrawableprivilege. Librariesare publicly owned (which,these cla ys, means owned bythe incumbent government).It is the government's responsibilityto manage them efficiently.Trust us, they say,we know what we're doing.But do they? They haven'tpresented any convincing argumentsthat CCT will bebetter for libraries. People arebeing asked to take it on faith.And anything they do is ignoredif it criticises the propo al.Nor are there any precedents. Evenin the Mecca of priva ti sa ti on, theUK, tendering out of librari es wasrejected in prin ciple.Citizens have a special right tobe concerned about the fate of theirlibraries. They belong to them in acon crete w ay which cannot bewritten off as the sentimentalexpression of an ab tract idea of publicownership. Free local publicI ibraries owe their very existence totion, free publicly-funded librarieshave been generally regarded as themost efficient m eans to achieve aninformed and democratically ablecitizenry. This used to go withoutsaying. In 1976 in the Report of theCommittee into PublicLibraries it was stated: 'N oargument needs to be madefor the criticality of the existenceof public libraries ...and the importance of an informedcitizenry, which understandsand is able to concitizenaction.Public lending libraries arc notsome sort of gift of the state. There isn o legi sla tion whi ch requiresmunicipal authorities to providepublic libraries at all. Indeed, hi storically,many municipalities initiall yresisted the idea. That they exist atall is testimony to the hard work anddetermination of small groups ofcitizens, not of the benevolence ofgovernments, state or local.The story of the St Kilda PublicLibrary is just one example. Thereare many others. In 1947, fed upwith the poor service provided bythe pri va tely run subscription librarieswhich were the only places fromwhich books could be borrowed,citizens lobbied the St Kilcla Councilfor a free public library. The suggestionwas rejected out of hand. In1954 the Council again refused. AsAnne Longmire writes: 'The towncl erk prepared long reports whichshowed that a library would be anunwarranted administrative andfin ancial burden'.Clea rly, providing a library wasnot a 'core business' then, and whow ould b e foolis henough to think, inthe present climate,that it might not be sorega rd ed aga in ? In1961 the idea wasaga in re jected. TheCouncil refused toconduct a poll on theissue. In the end itbecam e a bi-partisa npolitica l issue, but itwas only when councillorsactually beganlosing their seats overthe issue that, in 1967,the proposal finall ygo t the nod and thelibrary was eventually opened in1973. It had been a twenty-year struggle.All of this is within living mem ory. N o wonder people arc angrythat an un elected body should presumeto change the fundamentalstructure of the library service.But this onl y partl y expl ains theintense passion this issue arouses.Politicians should beware: actuallibntry u age is only the tip f theiceberg. Ju st as the benefi ts of librariesaccrue to a much wider ra nge ofV oLUME 5 N uMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 13

AN OPPORTUNITY TO LIVE & WORK INANOTHER CULTUREAustralian Volunteers Abroad (AVAs) work in challengingpositions in developing countries. The work is hard but satisfyingand require s skill, adaptability and cultural sensitivity. Salariesare modest but cover overseas living costs. A VAs work in manyoccupations but at present there is a need for applicants in thefollowing field s:• hea lth• community development• agriculture • computer technology• education • science• economics • administrationIf you have professional or trade qualifications and relevant workexperience in Australia , contact the Oversea s Service Bureau orsend in the coupon below.Applications are also welcome from recent graduates forthe Volunteer Graduate Scheme.Applications are being received now for 1996.V"j) Overseas Service Bureau.-----------------------------1YES, 1/'Ne want to find out more about the AVA program. 1IMr / Ms/Mrs/Miss/Dr:Address:Occ upation:P/ code:1 P.O. Box 350 Fitzroy VIC 3065 Phone: 03 9279 1788 u; 1~----------------------------- ~THE EXPERIENCE OF YOUR LIFEr----------------,~@J'Some countrieshave seen the useof systematicsexual violenceagainst women asa weapon of warto degrade andhumiliate wholepopulations'Dr Boutros Boulro\·Gh.th(UN Secretary General}Arnncsty Inte rnatio nal is actingto o utlaw this "we apo n'- forever.... IOIII '"Itkt• IIW, \ ' .tll"t' "''' .,] !-.\0\t'lllrtlt' lll ....]lt 't'''''' tlll\ l.ulutg to 111\t''ll g o~tt· .uul ptllll'h.dltl't '' In tlwi1 ,Uttwd lnttt'' · .di•H\tllg r.qwto llt't \1"1lltt• lllt·lil..~·• ' \II I HI III II ).: 111 !..\t'liJI · t \tlllll ' 'ol\ h,b !Jcl' ll .Ifill·I I

Wh at has changed such that weshould believe that this will now bereversed? But does any librarian,other than one aspiring to a seniormanagerial position, really think thatthey will be better off in terms ofsa lary and conditionsunder a tendered-outarrangement?If such an arrangementis goingto save money, notto mention enablethe su ccessful tendererto rake off thefee, isn't the onlyway this will bedon e by cuttings taff, employingcasuals, increasingwork loads I That'swhat happensever ywh ere else.Does anyone reallythink it won't happen to publiclibraries?The only place librarians can lookto for support in this matter is fromthe public, their borrowers. We havea deep common interest in this. Inthe absence of democratic machineryat the local level, direct citizenaction is now the only gu aranteethat free public lending libraries haveof their continued existence.The issu e is profound. If youviolate free public libraries, you violatedemocracy. But democra cy, weare now being reminded, is not somethingwe can take for granted. It canatrophy unless it is constantly andvigorously exercised.Wh ether democracy survives atthe local, or any, level is ultimately,up to the citizens. The direct attackson democracy being experienced inVictoria are having the effect of reinvigoratingit. The defence of democracyis just beginning and, as thelibrary issu eshows, it can draw ondeep wells. Business may be a wily,infinitely mutable ph enomenon, butdemocra cy, too, can take a thousandfor ms: if it is pushed in at one placeit wi ll certainly pop out at another. •Bill Garner is a Melbourne playwrightand screen writer. Hi s playsinclude Sunday Lun ch, for theMelbourne T hea tre Company.L AST MONTHSR~~~:

Home truthsL '" "'" MOOCconfirmed cases of children who hadbeen t hrash ed, bashed, starved,raped, abandoned or neglected bytheir parents were reported to Australianwelfare authorities. The reportrate went up by 20 % in thefollowing 12 months, and is beingmaintained this year.The rising tide of child m altreatment,and our unwillingness to admitthat we have di sm ally failed toprotect children, is a national disgrace.We have clone enough ficlcllin gwith the system : it is time to trysom ething radically different.'Child abuse' is a generous andimprecise term, covering everything,from torture to nagging, in a context.Over the last couple of decades ourarm y of child protection experts hasbecome much more aware of thepossible harm to children from certainbehaviours, and much m orewilling to describe it as maltreatment:being exposed to severe violenceaga inst others, for in stance,and 'discipline' which causes pain,humiliation and fear.That knowledge has not, however,been transmitted to parents. Accordingto a recent report commissionedby the National Child ProtectionCouncil, but not released, 80 %of their survey believed that it is notharmful to hit a child with yourhand, half believe that 'it is everyparent's right to discipline childrenin any way they see fit ' and almosthalf that no child could be reallydamaged by anything that a 'loving'parent might do. Yet rnost of themalso believed that child abuse is verywidespread across Australia, affecting20 % of fam ilies.T he experts know very well thatchild abuse is a growing nationalproblem . At the same time, knowingthe possibly damaging effects ofremoving children from their naturalenvironments, and (paradoxically)becau se the child protectionsystem s arc so over-taxed by increasingreferrals, child protection workersare in fact intervening less, andT H'N 20,000certainly less zealously, than wasthe case 10, 20 or 30 years ago. Oneexample, in a Victorian case-trackingstudy in 1994, spells it out.Two boys aged three and one hadparents with severe alcohol and drugproblems. They lived with theirMum w ho lived in fear of Dad'ssevere violence towards her. Shewasn' t copi ng: her doctor wasconcern ed a bout verbal a buse,neglect, inadequate medical care andnutrition and developmenta l delay.He referred them to a hospitalwhich released them when it couldfind no immediate evidence of physical abuse. Hospital social workersand the police were alerted becauseof the grave concerns about theirsafety. Welfare authorities refusedto accept a referral 'possibly becauseof the lack of evidence substantiatingthe case'.So the police handed over thekids to the fath er, a m an with criminalconvictions for ph ysical violence,to alleviate the possibility ofemotional abuse and neglect by hisprimary victim.In other words, even the expertsdraw arbitrary lines. They are afraidthat the law won't va lidateintervention because the situationdoesn't fit the increasingly restrictivedefinitions of ' child protection' Ia ws.They are reluctant t o rep ortsuspected abuse because they do nottrust the appropriateness of theresponse.On present research we knowthat no si ngle strategy will com pletely protect children from furtherharm , n or enhan ce the generalquality of their lives. We would preferto 'prevent' it, but we don't knowhow, because w e ca nnot predictharm, and onl y have experience oflate intervention .There is a grea t deal of woollys upport for 'primary prevention'progra m.s- pa rental and communitye du ca tion throug h m ediacampaigns. They have their place.We do have a National Child AbusePrevention Str ategy, a nd aCommonwealth National C hildProtection Council, whose job thisis. I have been provoked into writingthis article by reviewing the detailsof such a proposal, which will costmillions: a national advertising campaigntelling us that child abuse is acommunity problem .In the U S, natio nal m ediacampaigns did appear to have influencedexplicit a t t itudes andparenting practices, but seriousabuse and fatalities seemed to increase;in Victoria a 1993 ca mpaignincreased people's tendency to blamethe non-offending parent for theabuse; and Gillian Calvert's reportof the effi cacy of the four-year NSWC hild Sexual Assault Program massmedia campaign found there was aslight decrease in public awarenessof the problem - and a dramatic increasein those favo uring capital punishment-at its end.I looked at this during NationalChild Protection Week and shortlyafter reading that NSW, where 19children died of m altrea tment in thepreceding two years, was to cut itsfunding for services to children andfamilies; and aft er seeing publicityover a leaked report from a Victorianchild protection agency about graveproblems in responding to the huge! yincreased volume of reported abuseafter the introduction of"'{ i{ T mandatory reporting.v v HAT A I!E WE DOING ? Wh y ca n'twe prevent child abuse instead ofpicking up bodies? Our governmentshave, I think, become so accustomedto the 19th century response to abuseand neglect- the criminal justicemodel of surveillance and swooping-that they won't put their resourcesinto an y other response. Thisis how state governments ' protect'children: by authority and threat,yet we prevent child m altreatm entif w e support all children in all families.You don't do that by s noopingon the possibl y 'deviant' ones. T hat'show w e jus tified t he notorious' round-ups' of Aboriginal children.16EUREKA STREET • 0 CTORER 1995

The U.N. Convention on theRights of the Child which Au straliasigned in December 1990, is premisedon the assertion that the child's naturalenvironment is the family,where they may be prepared to livean individual life in society 'in anatmosphere of love and understanding.'The trouble is that many fam ili es can't provide it, not becausethey are deviant and uncaring, butbecause they are under stress, homeless,jobless, poor, or damaged bytheir own upbringing, or sick, orisolated, or desperate, or simply uninformed:they don't know what toexpect from their children, and can'tmeet their needs. They need help,not blame.In March 1994 the Minister forFamily Services asked m e to write areport on what the Commonwealth'srole should be in child abuse preven tion, while I was acting Deputy Director[Research) of the AustralianInstitute of Family Studies. My reportwas given to the Minister inDecember 1994. It was released inJun e, 1995, on a busy news day, andthe rest is silence.My recomm endations were thatthe Com monwcalth must acceptthat it has primary responsibility toprevent child abuse because it hasaccepted an international obligation,the UN Convention on the Rights ofthe Child, as well as a moral one.Commonwealth policies and programswhich affect children and theircarers arc scattered across portfolioareas, and none of them is predi catedon children's rights. Child care, forin stance, is seen primarily as theright of women, or associated withlabour market programs. There areeven three, distinct, anti-violenceprograms, each calling for a ' nationallycoordinated approach '. Com m onwealth policies and programareas have different policy ba ses andpriorities, and often operate independentlyof each other.As it has done for services forpeople with disabilities, and for thesa m e e thica l reason s, theommonwealth must develop a coordinatedchildren's policy, acrosspo rtfolio bo undaries. It shouldestablis h a policy co-ordinationunit- either within a major departmentor reporting to the Prime Minister-suchas the Office of MulticulturalAffairs, which can overseeand report upon it to Parliament.The Commonwealth must get itsact together.There is, I said, little value inmaking a symboli c appointment,such as a Commissioner for Children,unless that office possesses realresources and authority. The Commo nwealth should develop astatutory and administrative basis [a'Children's Services Act', perhaps)for planning and negotiating withthe States for their delivery of children'sand family services, predicatedon the human rights of, not platitudesabout, children.Preventing child m altreatmentis not a job for the police. W e areresponsible for the societal conditionswhich are associated with chil dmaltreatment- poverty, homelessness, social inequalities andinjusti ces, all of which are clearlyassociated with the misery ofchildren.This is the responsibility of theCommonwealth, which delivers socialsecurity, housing and other genericcommunity services, none ofwhich is focused a nd coh erentenough to achieve a 'child abuse prevention ' objective, because theCommonwealth doesn ' t have apolicy about children. When we havea non-a busive society you look atmaintaining non-a bu sive communities,and healthy family environments-parental support, education,and other family-specific policies .There are very few of them at aCommonwealth level, and Stateservices are sea ttercd, inconsistcn t,an d inappro pria t ely channelledthrough child-protection laws.Preventing child abuse is not, Ibelieve, the States' task . Theirtraditional responsibility is to interveneat a much later level, wherepreventive program s have failed andchildren are at risk, or damaged.However, the States' and T erritories'eight, distinct, child protectionsystems, arc forced into serviceas 'gateways' to what child and fa mily support system s there may bethrough their different and narrowingdefinitions of 'abuse' or 'risk'.There is not muchpointinintroducingnational definitions or childabuse laws, as many have suggested,unless there are nationally high quality,accessible child and family supportservices which are not coercive,and do not stigmatisc the familiesthat need them.We have failed to prevent ch ildabuse because we have no overview.We arc chained to a 19th centuryresponse which docs not work in2 1st century Australia.If we persist in trea ting children'shuman right to special protectionas some kind of optional 'need',which ca n be addressed whenever astate government has money left overfrom a Casino, or the Olympics, or atoll way, they won't get their entitlementsas human beings. They willbe irreparably damaged and the harmcan never be fully undone. •Moira Rayner is a lawyer and a freelancejournalist.VOLUME 5 NUMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 17

T HE CAROLINE CHISHOLM S ERIES : 9GERALDINE D oocuEFranl

'I have come to bring you life and bring it in abundance': one of the most glorious promiseson offer from Jesus Christ in the gospels. If we really believe that's His legacy to the Church, whydon't we behave as if we do? Why don't we take the risk of jumping in at the deep end, where it'snot comfortable; at the murky area where work-places are evolving; where intimate relationswithin Catholic families are being re-defined; where technology is racing ahead of ethical guidelines;where new trade-offs between development and the environment are being worked out;where wholly different cultures are determining what they share and where they will foreverdiffer?The pace of change, the nature of choice, has overwhelmed me from time to time. I made thedecision to leave a marriage, with my one-year-old child, wrestled with m y conscience, formedfirmly within the Catholic tradition. I set up house and made a n ew family with the man I've nowmarried; put parents and others through a lot; went through a lot m yself. And ten years later, Ihave been profoundly shaped by having stepped outside the rule-book of my Catholic community,which I passionately loved, and still do.I was highly indignant about the degree of change required of m e, and fought like hell. It mayseem odd to you, given that I instigated the major moves, but of course one can n ever plot all thatfollows, when every single arena of life- work, children, parents, one's God even, m aybe especially-seemto becom e quicksand. The God I'd thought would protect m e from confusion seem edstrangely silent, unreachable; certainly not offering refuge. Nothing was safe, not evenmy personal conversa tions with my God.B uT STEP-1\Y-STEP, ING LORIOUSLY, HESITANTLY, I hung on to a tradition and an institution thatmattered to my very bones, and forged som ething new for m yself, at peace with my own conscience.Oddly enough, it was a place where m any of the imageries seem ed rather vague butwhere m y sense of purpose grew. Quite a paradox, but wiser people than I, like Redemptoristmission fathers, sugges t this is a fa miliar pattern, known to people like St Teresa of Avila, amongothers: of less sense of connection with the Di vine, but more sense of activism .I never left the Church, either the formal or informal on e. And while I received considerabl esupport from individual priests, I couldn't say I felt that way abou t the institutional Church. Isimply pressed on regardless. I was conscious that, being in the public eye, I might appear like aclassic Catholic rebel, when in fa ct I felt anything but. I can't rem ember ever h ea ring a sermonwhich proved to me that the priest understood the nature of the titanic internal struggle I fel tm yself to be undergoing. I was just one of m any sitting before him.Which is not to say I haven 't heard some excellent sermons from som e very decent and gam em en, or that I imagine it would be easy for them to m arch, full speed ahead, into some of theseareas. If it was hard for som e of our forebears to talk about politics from that pulpit, just ponderthe challenge posed by fe minism! If Helen Garner is having trouble, pity help yo ur average parishpriest!This brings me to one of my central points: how could an average priest possibly enter debatesthat preoccupy wom en these days, wom en trying to live a life of spi ritual integrity, tryingextrem ely hard to chart their own course and perfect their purpose? Would he even know thelanguage, the nuances, the m omentum that characterises the broad debate am ong wom en ? Howmany modern women would the average priest, or bish op, system atically m eet in the course of aworking m onth ? I m ean meet in the sense of genuinely converse, be exposed to som e of theirdilemmas, 'lock horns', as H . G. [Nelson] would say! Precious few. Are the institutions in place toallow him exposure to m essy debates among his parishi oners? In m y opinion, the answer is no.Of course there are bodies at both parish and diocesan level which m eet regularly. Eachparish is m andated to have a Parish Council or Parish Finance Committee, which often becom esthe proxy Council. There are no figures collected on a widespread basis, but obviously they arcopen to both women and m en and this is always a lay body. Similarly, at the next level, thediocesan bishop is served by a Diocesan Finan ce Committee, almost always m ale, I'm told, whichm eets m onthly. The gender position is usually the exact reverse w ith education committees. Inother words, it reflects roughly the position within the population, of segregated work-a reas. InCardinal Clancy's offi ce, for instance, his Administrator is m ale but his accountant is n ow female, as of fairly recently.Most bishops are peppered with con tant request to 'interact.' So it' not as if they're notexposed to the world of busy-ness. But ironically, it's all done quietly, as if that's an attribute,drawn from humility. I think it's got to be more rather than less obvious.VoLUME 5 NuMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 19

I suspect too that the bishops eta] are mostly exposed to people m ore or less like them selves.It was the very criticism hurled at us in the AB C, eight or ten years ago and still is. We knew wewere working extremely hard, giving of our best, but the allegation was that we'd fa iled to seethat our sphere of influence was sh rinkingi we were not being disturbed enough.Does the Church really speak to the practical ethical problem s people fa ce in their moderncommunities? Rarely, I'd say.A couple of 'for-instances'. Where is the bea utiful language emanating from the C hurch,giving n ew codes or benchmarks by w hich an individual, ccking to be good, ca n measure his orher personal conscience when faced with, say, large-scale retrenchment of staffi bei ng part of ahostile take-over that involves assct-s trippingi when a huge executive saluy is on offer concurrentlywith downsizi ngi when the work culture is palpably hostile to any sense of balance withfa m ilyi when survival of the fittest is peddled as a legitimate response to the latest budget cut'When you know that yo u're going to be all-right-Jack but pity help the others.T h is is the stu ff of everyday li fe for contemporary workers. Yet som ehow, the tried-a nd -truem ora l tests-is this greed or dishonesty or uncharity'-sccm feeble, certainly n ot helpful. N ewmeans of describing these old verities n eed to be found so that they arc useful in helping educa tea contemporary conscience.T he C hurch's vo ice m ay well be clear- nay, strident-on sexual morality. But there's a stunningabyss w hen it com es to the murkier areas of business, politics and science. And it's in thesearenas that we so desperately need to rc-cmphasisc qualities like kindness, tolerance, for bearance,to rehabilitate

demand 'wholesale change'. It's bad enough inside the ABC, let alone the Church!But without it, we avoid asking the really obvious question: do we have the best governm entstructure to m eet current needs as opposed to current system s? Is it the most pro-active structureto seek out new relationships with the community?My personal m otto, as a woman of my times, is to construct a life that resembles the past butdoesn 't n ecessarily reproduce it exactly. My aim is to make decisions about this, not just to drift.That's my version of continuity. I have to be prepared, of course, to see m y own children makethe sam e sort of decision and re-invent things I thought were absolutes. That can be hard.But this is a model I'd like to see the Church adopt. To grasp afresh the m eaning of the Latinverb 'tradire'-to hand over. That has been interpreted in the strictest ideological sense of 'repeating'that which went before. I think it could be seen as enabling life within the next generation.Enabling new ways of saying old things: new ways of saying new things . Enabling new stru cturesto em erge, side-by-side if necessary, with old structures, but designed to position theChurch as a sign rather than a sanctuary.FoR ME,THIS IS T H E CORE OF IT . I want the Church to be the convenor of a bold, energetic, questingconversation within a community . I sense from my work in the m edia and plenty of interactionwith the public, that there's a yearning for som e new discussion about mores and codes. And afterthe discussion will come m ore clarity, m y real hope for the next century.But at the moment, the Church is barely there. Not only is the secular community missingits influence, o are those within the Church: it's loss-loss everywh ere, with priests and religiouscommunities fossilised, grappling with a sense of pointlessness. Because life, in all its m essinessand challenge, is elsewhere.The hunger I described earlier is often filled by half-developed notions, with a bias towardself-indulgence and no outward focus, no emphasis on mature fa ith. Feral spiritu ality, as someoneput it to me on Life Matters.As another colleague of mine, Fr Michael Whelan, suggests, our contribution is as much inexemplifying what it m eans to be an h onest search er as it is in candidly and forthri ghtly sharingthe wisdom of our traditions. The more w e are honest about our own doubts, fears, ambiguities,the more respect flows. Because, he suggests, su ch honesty implies great faith.The mood signalled by the Second Vatican Council might be a good guide: 'Let there be unityin what is necessary, freedom in what is unsettled and charity in any case.' (Gaudium et Spes).So how to be a searcher? How to institutionalise this? I believe there must be six featurespresent in anything that is set up: Conversation; Collegiality; Devolu tion of power; Modern-ness,that is speaking in language intelligible to each generation (Vatican II); Regularity; Respect.I want to overhaul the givens about the nature of dialogue between the hierachy and thelaity; I want to see Church governance transformed, drawing from society's models. I want, therefore, to see the Church run by a Board of Managem ent, set up within each archdiocese and modelledon the best-functioning government departments or authorities.In m y plan, the Archbishop or his delegate would always sit as Executive Chairman, amidsta committee of diverse contributors, drawn from the lay and clerical community. I see this as aBoard of Managem ent of the Church in the Community, with the Archbishop having righ t ofveto- I'm not a complete Utopian, nor a fool!I also see the need for sub-com mittees, just as in any good, modern progressive organisation,which operate on a mutual support basis: information and support drawn from the Church'sscholars and officers back to the communities: they, in turn, would inform Church authorities ofissues contested within their sphere.I recognise that Catholic advisory bodi es do exist, but at the behest of the bishop, and, effectively, no-one knows about them. Which brings me back to visibility.I would su ggest that just as the Governor-General does, every single bishop should be conveningregular gatherings at his table, where he listened, in a spirit of co-operation and curiosity,to the conversation or dialectic underway within society; thus informing himself and acting as aconduit for the passage of ideas between people: of being pro-active on behalf of Christ in a breathtakinglysimple way. And I would urge bishops to be game rather than cautious in their invitationlists. And I would never again have a biennial Bishops' Conference without a parallel meeting ofbroader groups, drawn, I'd suggest, from the various Boards of Management.People would be revitalised. The institution would be bolstered. I'm not about tearing downinstitutions. They're invariably the repositories of surprising resources and talents. The Churchwould put itself in the midst of the people whom it must serve, and not be distrustful of them andVOLUME 5 NUMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 21

their experience. The Church would set up a process of listening. For those afraid of the impacton Church as authority-figure, Church as preacher, I say this ca n hardly undermine that: it wouldprobably boost it, by providing it with modern data.And at all times, I would stress the importance of including women as contributors. I did asearch of the Church 's formal bodies and, after considerable effort, found, outside the schools andwelfare organisa tions, no systematic structures to include women. They m ay exist-no-one couldtell me exactly. But it was clear they were at the behest of individual bishops. This won't do. Itmust be much more of a given than that.My own experience of a new structure within the Church is som ething called Spirituality inthe Pub, which I want to briefly discuss. Several of us were dra wn together by john Menadu c, tosee whether there was a need to develop new wa ys of being Catholic.Out of eight m onths of intermittent talking and quite rigo rous debate and mission-statementdiscourse, we came up with a simple, unfussy and modest model of SIP: we wanted Religionin the Pub, but RIP wasn 't quite the image we wanted to send' The idea was to promote a newfo rum, new conversation within the Church, of a kind most of us didn't feel we go t within pari shes.We wanted to talk about issues of relevance to our lives, raw-edged iss ues on which therefrequently was no longer consensus: issues that the Church- in our view- dodged. And sometimesI could quite sec w hy.We foun d that there wa s no short-c ut. There had to be much discussion on them es for theyear. We meet every six weeks or so in a pub in Paddington, and to complete the metaphor, it's inthe Upper Room! It's free . Drinks from the bar. Two speakers: one always representing the institutionalChurch and therefore informed by the tradition; one representing modern dilemmas, ina sense. Our topics have been modern conscience, when is it right to play god-the euthanas iadebate, and consumerism. Our nex t two are the challenge of science, and the ethics of modernwealth creation. We're finishing with the conscience of those arriving from other faiths.It is very convivial, non-Churchy, with a small orga nising committee. Next year, we' ll set anew theme for 1996. Speakers have been extremely willing to p·uticipate, no matter what theirfrantic schedule, bearing out m y view that there arc people of immense goodwill, dying, in fact,for the Church to assume a new sort of leadership ro le in this moral debate and willing to do allthe messy, bureaucratic work of setting this up.It seems to be working and filling a need. It's small, the leaven in the lump, but we're quietlyquite proud of it, and I might add that we've kep t the hierarchy inform ed and have receivedencouragement, notional but significa nt, I believe. It doesn't seck to circumvent or undermineexisting structures. It's an addition, and nails its fla g to the mast: it is Catholic and works withinwhat I'd say are the portals of the Church, whether or not that's on C hurch property.The spirit of Vatican II is alive and well within it. I want to close on som e beautiful wordsfrom The Chmch in the Modem World. You'll have to tolerate the exclusive language/ which is a touch confronting. But the sentiments carry the da y.T IIOUG H MANKIND TODAY IS STRUCK WITH WONDER at its own discoveries and its power, it oftenraises anxious questions about the current trend of the world, about the place and role of man inthe universe, about the m eaning of his individual and collective strivings and about the ultimatedestiny of reality and of humanity. Hence, giving witness and voice to the faith of the wholePeople of God gathered together by Christ, this Council can provide no more eloq uent proof of itssolidarity with the entire human family with which it is bound up, as well as its respect and lovefor that family, than by engaging with it in conversation about these various problems.'For the human person deserves to be preserved; human society deserves to be renewed.Hence, the pivotal point of our total presentation will be man himself, whole and entire, bodyand soul, heart and co nscience, mind and will.'Therefore, this sacred Synod proclaims the highest destiny of man and champions the godlikeseed which has been sown in him. It offers to mankind the honest assistance of the Churchin fos tering that brotherhood of all men which corresponds to this destiny of theirs. Inspired byno ea rthly ambition, the Church seeks but a solitary goal: to carry forward the work of C hristHimself, under the lea d of the befri ending Spirit. And Christ entered this world to give w itness tothe truth, to rescu e and not sit in judgm ent, to serve and not to be served-'•This is an edited text of the Catholic Institute of Sydney's Vecch Lecture for 1995, delivered byGeraldine Doogue at the State Library of N ew South Wales.22EUREKA STREET • O cToBER 199S

SPORTING LIFEPETER PIERCERight on trackI n Sydney, it h•d not mined fnt fotty d'Y' and fmtynights. Rosehill racecourse, where I'd not been for half alife-time, baked in record August heat of 3l.3°C. Trackrecords, besides tempers, were at risk.Before travelling there, we visited the superb newMuseum of Sydney. Soon the treasures of the MaritimeMuseum in London would be packed and the 'Fleeting Encounters'exhibition closed. But we were able to view its'Pictures and Chronicles of the First Fleet', together with acornucopia of remains of the earliest years of Europeansettlement in Australia. Here were sets of ships' cutlery,ceramic dolls, pipe stems, coins, accidental survivals likea puppet found in the Macarthurs' cellar. There were alsodocuments seeking to exude authority-suchas the Standing Ordersfor New South Wales-andothers mocking it: the notebook inwhich Frank the Poet inscribed' Athe exhibition was a view of RoseHill, 'a spit upon rising ground ... ordered to be cleared forthe first habitations' as David Collins wrote in November1788 of the farm on fertile land by the Parramatta River.Just under a century later, a proprietary racetrack openedat Rosehill. Coming under the control of the Sydney TurfClub in 1943, it has since made much of limited naturalassets, as I was shortly to be reminded.First to get there. Forget the train, the helpful PR staffof the STC informed me. Take the River Cat. Thus I boardedthe 'Marlene Mathews' at Circular Quay, thence to passbeneath the Harbour Bridge, stop at renovated Luna Park,skim by yacht harbours, jutting apartments, an Olympicsite-to-be and St Ignatius, Riverview, before container terminals,decaying factories and the RAN arms depot edgeddown to the river. By now the boat had slowed to a walk,not only to let sister vessel 'Shane Gould' get by in thenarrowing stream, but because the momentum of catamaransis eroding muddy banks and stirring residues of heavymetal.In an hour we were hard by Parramatta. The STC hadprovided free transport and racebook. To enter the course,the bus travelled four sides of a square, revealing the giantRosehill Gardens sign that proclaims the track's new, presumablyAmerican-style misnomer. Looking back to thecity, one descries the bridge and skyscrapers in the distance,but in the foreground an ugly cluster of oil refinerybuildings. And the track is cramped, with famous out-ofsightstarts for middle-distance races, endlessly turning1200 metre circuit for its great attraction, the Goldendanexhibitedto the embarrassment of• liiRi= the 'principal' clubs.Nevertheless, at RosehillGardens, there was racing to delightuch local sponsors as theRooty Hill RSL and Lidcombe SydneyMarkets clubs. Unfortunatelythe free bus delivered me in time to back I'm A Freak,which missed the tart and ran ncar last. Two races later,top jockey Mick Dittman's mount was second. Remarkably,he had ridden only one Sydney winner in eighteenmonths. That changed, but not before the Premier's Cupwent to Tom Cruise look-alike, 'born-again' Darren Beadman,on Ardeed. Meanwhile in Melbourne, at once despisedSandown, Grand Baie ran an Australian record for lOOOmand the fine grey Baryshnikov won the Liston Stakes fromthe Hayes-trained Western Red and Jeune. With the thanklesstask of inheriting a famous name and stables from fatherand brother, P.C. Hayes not only has the aforementioned two well forward, but also Manikato place-gettersSeascay and Blevic. Watch for them in the spring, andfor Hawkes' Octagonal.And for Flying Spur, a lovely bay colt, last year's GoldenSlipper winner, who showed staying scope by winningthe Peter Pan Stakes, with Dittman up. Back in the glassedinpublic area, signs pointed distractingly to the Longchampsand Chantilly bars. The STC guesses that tradition,in racing as in much else, is mostly in the brand name.After a peerless day, clouds gathered, but no rain fell. Thisis a lucky club. Ask Moonee Valley, which is still hopingthat a newly-laid track will be ready for racing on 1 Octoberand that it can host the Cox Plate, rather than seeing thenational weight-for-age championship go down the road toFlemington, as the smarties have long predicted. •Peter Pierce is <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>'s turf correspondent.VOLUME 5 NUMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 23

REPORTJiM D AVIDSONScholars on the looseAT' T

W,.. '"'CANTHE R EG IONJAMES GRIFFIN1NeighboursYOU "ND A w"' w ho will give youa pedicure with a toothbrush', asked the near-sexagenariansquatter from Johland-rhetorically, one hopes, as Australianshave not been so conspicuous in the fl esh trade outsidethe Phillipines yet.N ot that recruiting w ives, even on that basis, is the worstof it. Many m arriages of con venience work benignly enoughfor the brides, and often for their indigent extended families.Bartered brides are not invariably battered.The pits is, of course, not the arranged marrying or thewhorem ongering but the paedophilia. And that will notcease when Australians are blocked from sleaze holidays.The Filipino male has ultimately to look to that, as PresidentRam os indica ted during his recent visit, the first by anincumbent Philippines head of state.There is not much point in exaggerating the degree ofAustralian infamy as Meredith Burgm ann MLC (NSW) hasdone. N or in dressing up as murdered (by Australian husbands)Filipino brides or even branding Ram os as the Philippines''biggest pimp' as was done by som e at the Universityof Melbourne when Ramos was to be given an honorarydegree. Ju st to show there are no facile nostrums, thepresident warned sex offenders that he will now look atapplying the death penalty for 'heinous crimes' to foreignpaedophiles. The demonstratorsmay not relish a situation,where another Australian prime minister feel he has to callanother Asian government ' barbaric' for executing Australians,as happened with Bob Hawke over our drug pushers.It might be wiser to accept the extension of the FederalCrimes Act to sex tourism and the sending of police officersto help with sex and drug surveillance.N othing is going to be simple in our relations with Asiancultures, and the root causes of the m ost exploitative aspectsof the flesh trade are obviously poverty, overpopulation andobscurantism . No doubt Ramos will welcom e any suggestionsas to how these can be quickly overcom e.It seems incongruous that, when we are trying to ga inacceptance as a compatible neighbour in South-East Asia,there should be a muster at a University to protest at a leaderwho was vital to the overthrow of the Marcos kleptocracy.While being much m ore decisive, Ram os retained the confidenceof Cory Aquino and, although a soldier, has uphelddemocratic forms in a country that provides the sort ofbridgehead into Asia that Australia needs. The Philippineshas a predominantly Christian culture (80 per cent Catholi c,9 per cent Protestant, 5 per cent Muslim, 3 per cent Buddhist )and 5 1 per cent understand English (although only one percent speak it at home) .With the fraying of our separate American alliances,w hich forestalled the need for close bilateral securityarrangem ents, the time has com e for increased defence cooperation.While we have no urgent defence issue at present,Chinese activity at the well-named Mischief Reef in thestrategic Spratlys is unnerving in Manila and, in the longterm , a m atter of concern for Canberra. T he sort of antiinsurgencyaid given in the past, that suggested obsessiveanti-Communism and could be construed as a prop forMarcos, can now be seen serving the Filipino interest ratherthan that of a particular regim e. Moreover, Australian racismsuch as was perceived and bitterly resen ted in theGamboa (1948) and Locsin (1966) entry visa cases, has beendispelled by immigration which increased between 198 1 to199 1 from a total of 15,500 to 74,000 (roughly 2: 1 fem ale tom ale), m aking Filipinos the third largest non-Europeangroup after Vietnamese and Chinese.After the inert years of Aquino's presidency, Ram os hasderegulated the financial system, promoted investment inm anufacture and raised the annual growth rate to 5. 12 percent. This is lower, certainly, than in the so-called dragonand tiger states but still very positive. T here are opportunitiesfor increased trade, very much in Australian favour atthe m om ent (over 3 :1 ), but representing only 0.4 per cent ofour total trade. During the Ram os visit a number of dealswere done, including eleven joint ventures in power andwaste-water infrastructure.In 1971 -2 Foreign Secretary, Carlos Romulo, urged acloser relationship between our two countries and noted thepaucity of Philippine studies here. It is extraordinary that solittle literature is generally available. Only the ANU, Canberra,and, very much to its credit, Jam es Cook University,Townsville, have taken our neighbour of nearly 70million people very seriously.ASIDE FROM ARTICLES IN LEARNED JOURNALS, the Only m onographon Australia- Philippines relations published for decadesthat I can recall was edited by two JCU scholars, ReyIleto and Rodney Sullivan, significantly as DiscoveringAustralasia: Essays on Philippin es-Australia Interactions(Townsville, 1993 ). The bibliography provided by the Universityof Canberra's Mark Turner yields much that isinteresting on the Philippines but little of an Australianbent.However, what these essays reveal is a relationshipwhich goes back to the 1850s. when Australia took a quarterof Philippine exports. By 1900, Australia was the fifth largestsource of imports. There was at the time vigorous Filipinoimmigration to N orthern Australia (including T orres Strait)and Papua.Both American hegem ony in the Philippines and theWhite Australia Policy (1901 ) caused a promising relationshipto lapse precipitously from then on. Discovering Australasiaexplores these early relationships and proceeds to asearching examination of the Gamboa cases, a curiousFouca ultian conflation of the press reportage of the activitiesof Juni Morosi and an earlier Filipino victim of 'patriarchaloppression', and an enlightening analysis of currentPhilippine immigration.Perhaps the Ramos visit will inspire other scholars tofollow up these overdue 'discoveries'.•James Griffin is a freelance critic and historian .VOLUME 5 N UMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 25

Gareth Evans, above,on another occa ion,speal

His father might have ended his days as a countrypublican in the colonies but he had begun them as aschoolboy at Charterhouse, and his father's brother,Sir George Hamilton Evatt, became Surgeon-Generalin the British Army. The Evatts, in fact, wereAnglo-Irish Protestant gentlemen given to producingsoldiers for the crown and parsons for the establishedchurch. Dr Evatt's mother was also of Irish-AngloAustralian Protestant stock and, by all accounts, aformidable lady who demanded much of her sons andgave them a solid grounding in evangelical Anglicanism.A strong streak of puritanism was to mark Evattfor the rest of his life. In his mid-twenties he marriedthe daughter of a wealthy American.Given that background and his own intellectualbrilliance, it is not too surprising that the young Evattdid not lack confidence. This could show itself inunimportant ways: outraging the Rugby Union gentlemenby bringing Rugby League into the university,for example. (He even flirted with proper football,visiting Melbourne in 1910 with a Fort <strong>Street</strong> team toplay what was then called Victorian Rules.) It couldshow itself in more important ways, as in 1927 when,after one term in the State Parliament, he publiclydamned his leader, Jack Lang, stood successfully asan independent and was expelled from the Statebranch of the Labor Party complaining of Communistinfiltration.In a prize-winning undergraduate essay whichwas later published, Evatt argued that in Australiathe party differences were minimal: Whig liberalismhad triumphed completely and rightly. In his view,however, there was a division, and it is worth quotinghis youthful description of it: a division 'correspondingto that of minds conservative by nature andminds progressive by nature'. He continued:In all domains of life and art we find one classdesiring to press forward, to experiment, to find inany change a bettering of present conditions, and asecond which clings with veneration to whatever istraditional and ancient, and which distrusts thedangerous and unnecessary proposals of what appearto it a shallow empiricism.There is not much doubt about the side of thedivide on which h e saw himself, but it remains thathe supported conscription in 1916 and, in his essay,he questioned the Labor pledge and Labor caucus solidarityas inimical to true liberalism. Nor was h emuch taken with the notion of employm entpreference for trade unionists.ITIS ALSO TYPI AL OF EvATT that, apparently not fullyextended by the High Court's demands, he turned tohistory in the 1930s with two pioneering books-onedefending Governor Bligh, till then generally seen asa tyrant properly deposed, and the other a defensivebiography of W.A. Holman, generally seen in the Labormovement as a 'rat'. That other great rat in Laborlore, Hughes, was also admired publicly and privatelyby Evatt.Evatt had a brilliant legal career by any standards.From the University of Sydney, he graduatedwith a BA (triple first), obtained an MA (first) and tooka doctorate in laws (which later became hispath-breaking study of the reserve powers,The King and his Dominion Govemors). In1916 he became Secretary and Associate tothe Chief Justice of NSW, Sir William Cullen.He went to the Bar in 1924 and took silkfive years later. In 1930, at the age of 36-theyoungest-ever appointee, and likely to remainso-he was placed on the High Court by theScullin Government. There he served for thenext decade, before succumbing at the age of46 to the siren song of politics- leaving theCourt younger than the age nearly every otherJustice has arrived.As Commonwealth Attorney-Generalafter 1941 he went back frequently to theHigh Court as an advocate-even arguing forthe Government before the Privy Council inthe Bank Nationalisation Case at the sametime as being President of the UN GeneralAssembly in 1948.On the High Court bench, one of Evatt'smost distinctive qualities as a Judge was hisconcern with social consequences and civilliberties; in his own words, h e 'alwayssearched for the right with a lamp lit by theflame of humanity'. His models were Holmesand Cardozo in the United States and LordWright in Britain.The best known example of this wasprobably his dissenting judgment in Chesterv Waverley Corporation-the 'nervousshock' negligence case in which he eloquentlytook the part of the mother whose childhad been drowned in a Council trench, andin which his statement of the law came soonto prevail. In constitutional cases he camedown on the side of the States, more oftenthan the Commonwealth Labor politicianswho appointed him would have liked, althoughmore for reasons of legislative efficacyrather than any conceptual'States' rights'perspective.That he saw legislation as a medium forsocial reform, and had been a member of areformist State Government when the FederalBruce/Page Government was conservative, mayalso have coloured his views.Certainly no Commonwealth power enthusiastcould quarrel with his interpretation of the externalaffairs power in the Burgess case-which eventuallybecame orthodoxy in the The Tasmanian Dam casein the 1980s.Probably theclosest he cmneto a friendship inthe 1ninistry waswith Ja ck Beasley:it is somehowtypical of Evattthat he shouldcultivate Beasley,who rejoiced inthe nicknmne of'Stabber Jack 'and had beenone of the Langgroup whichbroughtdown theScullin LaborGovernment in1931-another'rat'.VOLUME 5 NUMBER 8 • EUREKA STREET 27

Speaking in 1965 of Dr Evatt's term on the HighCourt, the then Chief Justice, Sir Garfield Barwick,said this:To the decision of such of these cases in which heparticipated, Herbert Vere Evatt made great contributions.His judge ments in many of them provideforceful and lucid expositions and applications ofthe law. Many of such judgem ents examine andrelate to each other in a masterly fashion theprecedents of the past with which he made himselfso precisely conversant as he applied himself sounstintingly to the pursuit of the answer to theproblem which each case in its turn posed fordecision. They disclose extensive and penetratingscholarly research which illumines the aspects ofthe law with which they deal. These judgem entswill long be used by students and teachers of thelaw, by practitioners and by courts of law ... I they)expressed views of the law which were well inadva nce of his Honour's time and received acclaimfrom lawyers throughout the British Commonwealthincluding the Privy Council.This was a very gracious tribute from Barwick,given not only all their obvious differences of outlook,but also their person al history. David Man'sbiography of Barwick retails a story from their da ysat the Sydney Bar together which says much abouttheir respccti vc personalities. Evatt believed that logicwould carry the weight of his argument, and neverworried much about whom he was appearing before.Barwick, by contrast, believed in working the man,and urged Evatt to study a particular earlier decisionof the judge in question about which- whatever itsm erits- the judge was inordinately fond. Evatt ignoredBarwick's suggestion. Inevitably the judge asked hirnwhy h e was not relying on his earlier decision. Evattreplied that his junior had not drawn his attention tothe case. At that point, Barwick said 'Go tobuggery' and left the court.STORIES LIKE TH IS, OF WHIC H THERE ARE MANY, are perhapsthe reason why Evatt found himself som ethingof a political loner when, after stepping down fromthe High Court bench and entering Federal parliamentin 1940, he becam e a member of John Curtin's Governmentin 1941. While he had made some friends inthe lcftish artistic and literary worlds of the time,mainly through his wife, Mary Alice, he was too highlystrung, abrasive and egotistical for much in the wayof political fri endships. Probably the closest h e cameto a friends hip in the ministry was with Jack Beasley:it is som ehow typical of Evatt that he should cultivateBeasley, who rejoiced in the nickname of 'StabberJack' and had been one of the Lang group whichbrought clown the Scullin Labor Government in193 1- another 'rat'. Despite courting m en as diverseas John Wren in Melbourne and Clarrie Fallon in Bris-bane, he did not have a personal power base in theparty when he arrived in the Federal Parliament, andnever subsequently acquired one.Evatt entered the NSW Parliament as the memberfor Balmain in the 1925 election when the LangGovernment took power on a platform of extensivesocial and labour market reform. He managed thepreselection hurdle partly by relying on the thenmulti-member character of constituencies, whichmade it rather easier; and secondly by making a successfulpitch for trade union support by writing a seriesof influential articles about the victimisation ofworkers after the 1917 railway strike. He immediatelyearned Lang's displeasure by defying the party's conventionson seniority and nominating himself forAttorney-General- he obtained two votes in caucus.He was, nonetheless, an energetic contributor to theLang Government's pioneering social legislation. Thiswas the first government in the world to provide pensionsfor widows on a non-contributory basis, throughthe 1925 Widows' Pension Bill which the Oppositiondescribed as 'the most soul-destroying, poisonous bill'.Seventeen years later the Commonwealth introducedsimilar national legislation. Evatt played a large partin framing both bills. His drafting skills were alsoapplied to the 1926 Workers Compensation Bill whichhe piloted through the NSW Assembly and the 1927Family (Child) Endowment Bill, the model for Com m onwealth legislation in 1942.Evatt returned to politics, becoming the Federalm ember for Barton in August 1940, with the help ofan invitation from the ALP's National Executive, andhis willingness to contest a UAP-hclcl seat wh en noone in a safer seat would withdraw for him. WhenCurtin formed a government in October 1941, Evattbecame both Attorney-General and Minister for ExternalAffairs.Even with the preoccupations of the war, whichsaw Evatt work to a schedule that even modern ministerswould regard as extraordinary, he retained hiscommitment to social reform through legislation. Thedefence power allowed the Commonwealth the latitudeduring the war to manage the economy in areaslike labour m arket regulation and prices policy. Evatt,keen to build on these gains, led the efforts of successiveLabor governments to extend the Commonwealth'speacetime powers. Ever the legalist, he sawconstitutional reform as the m eans fo r this: between1944 and 1948 he proposed and supported five m easuresfor amendment of the Constitution, only one ofwhich, on social services in 1946, was su ccessful. Themotif of most of the proposals was post-War recon struction, retaining or building on powers which Canberrahad exercised in wartime, although Evatt alsoadded to the wide-ranging reform proposals of the 1944referendum a proposal for constitutional guaranteesfor freedom of speech, expression and religion.Evatt's passion for civil liberties was actuallynever more fin ely demonstrated than in the battle he28EUREKA STREET • O c TOBER 1995

led not in favour of a constitutional amendment butagainst one-the 1950 referendum on the abolitionof the Communist Party. It is worth mentioning thisachievem ent-which I would regard as the finest ofEvatt's political career- at this point, although to doso is to jump forward in time to his period in Opposition. When the Menzies-Fadden Governm ent waselected in 1949, it was against the backdrop of fearsof a world communist revolutionary m ovem ent, andthe new Government's first m ajor legislative initiativewas the 1950 Communist Party Dissolution billwhich, once passed, was immediately subject to aHigh Court challenge. Under fire from conservativesand some in the ALP, Evatt accepted the brief for theWaterside Workers Federation, one of the plaintiffsm ounting the case alongside the Communist Party.The High Court held the act was ultra vires the CommonwealthParliament. Menzies then called a doubledissolution, was re-elected, secured control of theSenate, and announced a constitutional referendumto overcome the High Court decision. Throughout anintense and bitter campaign, Evatt brilliantly, tirelessly-andalmost single-handedly-dwelt on the potentialfor abuse if government could ban a politicalideology, condemning resort to totalitarian m ethodsto fight totalitarianism . His argument eventually wonthe day in enough States to defeat the referendum. Itwas a wonderful victory for Evatt, but it came at ahuge political cost: the m antle 'defender of communism', reinforced when he leapt hea dlong into thePetrov affair three years later, was to hurt Evatt badly,in subsequent polls and in the internal politics ofthe Labor Party. But as Justice Michael Kirby has written,this 'libertarian warrior's ... leadership in the defeatof the referendum campaign, against all odds, wasa wonderful and lasting contribution to the politicalethos of this country'.If the referendum campaign was Evatt's finestdomestic political achievement, it was as foreign ministerthat he made his most enduring contribution tothe course of Australian history, and to Australia'splace in the world. I think it is accurate to describehim as Australia's first genuine internationalist. AlthoughJohn Latham and Stanley Melbourne Brucewere both seen in Geneva as fri ends of the Leagu e ofNations, there were no Australian political leadersbefore Evatt, and have been very few since, with anythinglike his commitment to the building of cooperativemultilateral institutions and processes toaddress both security and developmentobjectives.F O REIG N MINISTERS HAVE T O DEAL with governments,personalities, circumstances and policies in constantflu x, and their lasting monuments tend to be few.Evatt's successor, Percy Spender, was a lucky exception,leaving behind him after only two years in thejob both the Colombo Plan and the ANZUS treaty. InEvatt's own eight years in office, there are really onlytwo lasting monuments that really stand out, but whatsignificant landmarks they were! The first was toswing Australia behind the Indonesian Republic andcontribute significantly to its effective independencefrom the N etherlands. And the other was his contributionto the founding of the United Nations. Evatt'scontribution to the San Francisco onJerence of 1945was the stuff of which legends are made-especiallyin his fight for the rights of the smallerpowers against the grea ter in the roles ofthe General Assembly and the SecurityCouncil, and in his faith in the UN as anagent for social and economic reform andas a protector for human rights.The Big Three- the US, the SovietUnion and the UK-were interested in asuccessor to the League of Nations as aninternational peace-keeper only if it mettheir needs, was their creature and threa tened them with no embarrassm ent. It wasthe Big Three-supplem ented by this timeby China-wh o drafted a charter fo r aUnited Nations. It was the Big Five-bythis time with France included- who invitedthe other forty-five states then comprisinginternational political society todiscuss their draft at San Francisco. If asmall power like Australia wanted to seechanges made to that draft charter, itwould clearly have to force those changeson very reluctant, not to say intransigent,grea t powers. And the grea t powers o organised the conference as to stack the oddsagainst small power impertinence. Theconference lasted for three m onths- andit comprised some four commissions,twelve technical committees of the whole,a steering committee of the whole, an executivecommittee and a host of sub-committees!It was in that maelstrom that Evattmade his marl