n - Eureka Street

n - Eureka Street

n - Eureka Street

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

'We are presently in the grip of a powerful, fashionablefetish for economic solutions in education and elsewhere. Inmy view; these need urgently to be balanced by a moredemocratic position. In this, we need to make a clear andfirm restatement of the value that should attach tointellectual independence, academic freedom, institutionalplurality and critical thought. '-Spencer ZifcakSee 'Brave new world', p24

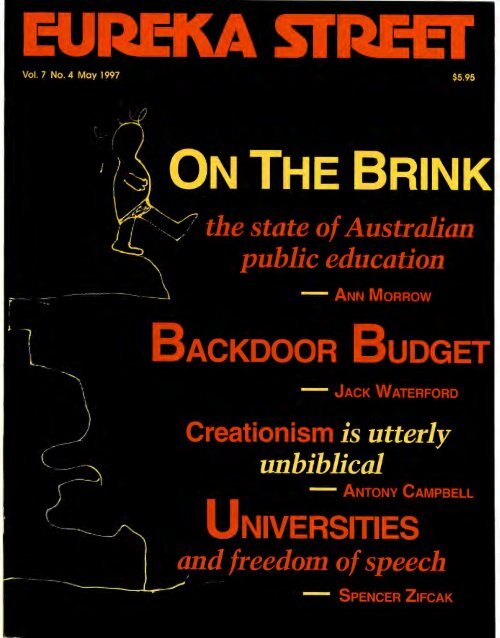

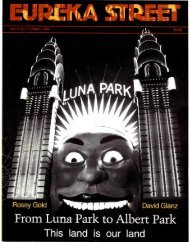

Volume 7 Number 4May 1997A magazine of public affairs, the arts and theologyWhat I object tointensely is any claimby creationists or onbehalf of creationiststhat their viewemerges from a literalunderstanding of theBible. That is mybailiwick andI will defend it.Creationism as aliteral understandingof the Bible is bunk.-Antony CampbellSee 'Creationis1n!CONTENTS4COMMENT7CAPITAL LETTER8LETTERS14THE MONTH'S TRAFFIC18LIFE AND DEATH MATTERSW.J. Uren teases out the knots of theeuthanasia debate as it is being conductedin research surveys.20SCHOOL DAZEWhat is the future of public education?Morag Fraser interviews Ann Morrow,former Chair of the Schools Council.23SUMMA THEOLOGIAEUtterly unbiblical', p30. ;:AVE NEW WORLDCover drawing and drawings pp2,20-22, 24-26, from the fo lio ofSam Thomas, aged 6.Cover design by Siobhan Jackson.Graphics pp9, 10, 18, 23, 28, 30, 38,40 by Siobhan Jackson.Cartoons p 14, 17 by Dean Moore.Cartoon piS by Peter Fraser.Photograph p21, 22 by Bill Thomas.Photograph p45 by Greg Scullin.<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> magazineJesuit PublicationsPO Box 553Richmond VIC 3121Tel (03) 9427 73 11Fax (03) 9428 4450Spencer Zifcak counts the cost of a lossof autonomy in Australian Universities.27INDEFENSIBLE SPENDINGWe're still spooked by the thought ofinvasion, according to Brian Toohey, andpaying big bucks for our paranoia.28ALL A BIT ON THE NOSEPaul Chadwick puts forward a plan for theretention of some diversity in our printm edia. But don't hold your breath ...29ARCHIMEDES30CREATIONISM! UTTERLY UNBIBLICALWhy swap the theological wealth of theBible for the insipid message of creationism,asks Antony Campbell.35POETRYLate Division and Upper East,by Peter Rose.36ENGLAND HER ENGLANDMargaret Drabble talks with MargaretSimons about the country that makesher furious and fuels her novels.38BOOKSAndrew Hamilton reviews Millennium andReformation, Christianity and the World1500-2000 (p38) and Robert Crotty's TheJesus Question (p41 ); Max Teichmann siftsthrough Samuel Hungtington's The Clashof Civilisations (p39); Brian Toohey assessesAgeing and Money (p42); Alan Wearnereviews a quartet of new poetry (p43); andTim Thwaites goes Climbing MountImprobable with Richard Dawkins (p44) .46FOOLS RUSH INGeoffrey Rush had a distinguished stagecareer long before that award, says GeoffreyMilne.48FLASH IN THE PANReviews of the films When We Wem Kings;Blacluocl

I:URI:-KA STRI:-ETA magazine of public affairs, the artsand theologyPublisherMichael Kelly SJEditorMorag FraserConsulting editorMichael McGirr SJAssistant editorJon GreenawayProduction assistantsPaul Fyfe SJ, Juliette Hughes,Chris Jenkins SJ, Siobhan Jackson,Scott HowardContributing editorsMelbourne: Andrew Bullen SJ,Andrew Hamilton SJAdelaide: Greg O'Kelly SJPerth: Dean MooreSydney: Edmund Campion, Gerard WindsorEditorial boardPeter L'Estrange SJ (chair),Margaret Coady, Margaret Coffey,Valda M. Ward RSM, Trevor Hales,Marie Joyce, Kevin McDonald,Jane Kelly IBVM,Peter SteeleS), Bill Uren SJBusiness manager: Sylvana ScannapiegoAdvertising representative: Ken HeadPatrons<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> gratefully acknowledges thesupport of Colin and Angela Carter; thetrustees of the estate of Miss M. Condon;Denis Cullity AO; W.P. & M.W. Gurry;Geoff Hill and Janine Perrett;the Roche family.<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> magazine, ISSN J 036- 1758,Australia Post Pri nt Post approvedpp349181/003 14is published ten times a yearby <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> Magazine Pty Ltd,300 Victoria <strong>Street</strong>, Ri chmond, Vi ctoria 3 121T el: 03 9427 73 11 Fax: 03 9428 4450e- mail: eureka@werple. net.auResponsibili ty for editorial content is accepted byMi chael Kell y, 300 Victoria <strong>Street</strong>, Richmond.Printed by Doran Printing,46 Indust rial Drive, Braeside VIC 3195.© Jesuit Publications 1997.Unsolicited manuscripts, including poetry andfiction, will be returned only if accompani ed by astamped, self-addressed envelope. Requests forpermission to reprint material from the magazineshould be addressed in writing to:The editor, <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> magazine,PO Box 553, Richmond VIC 3 121.C OMMENTJAMES GRIFFINCoup de graceW TC H

order and to curb kleptocrats. There are reasons for this, butcritics of PNG often seem to know more about that countrythan they know of their own. It was always ironic instructingPNG students about 'conflict of interest' when many Australianpremiers had little awareness of it.While identities like Singirok hold out for a political ratherthan a military solution to the Bougainville tragedy, there areothers with faith and heroism toiling away in villages to bringabout 'restorative justice'.Brother Patrick Howley's Peace Foundation Melanesia(formerly, Foundation for Law, Order and Justice) issues amonthly newsletter which is the best record of what ishappening on the ground in Bougainville today. The PFM's logois inscribed 'Peace and Community Empowerment'. BrotherHowley relinquished a distinguished teaching career bothwithin Marist schools and as principal of one of the four nationalupper secondary high schools, to focus on the art of conflictresolution. He has a group of instructors working throughoutthe province.What is surprising is the amount of constructive work beingdone. Obviously most people are sick of war and want peace.This includes even some combatants from among both the BougainvilleRevolutionary Army (BRA) and the pro-governmentResistance. In the North-West of the main island recently, some200 BRA surrendered and handed in their weapons in spite ofthe risk involved, and were seen in Buka town for the first timein years. Along with such hopeful signs, however, are nowanarchic alliances forming when BRA squads fragment. TheyCOMMENT: 2MICHAEL M c GIRR SJcomprise young 'rambos' who were seven or eight when warbegan and are now carrying weapons. They are uneducated-in1988, 90 per cent of Bougainville children were in school-andsusceptible to violent cultism.In the Bana area (population 24,000) on the fringe of theBRA redoubt in central Bougainville, five community schoolsnow cater for most school-age children after having had allschools closed during 1990-96. Adult literacy classes try to copewith those who missed out. Courses in spiritual rehabilitationand reconciliation have been effective, if slow. Brother Howleywrites that 'many people believe the road to peace is for eachvillage to make its own peace, then peace with its neighbours,then with the areas further away until the units are able to joinup into districts'. Bana is moving in this direction. Slow,certainly, but better than being blown away by m ercenary fuelairbombs. Similar community resources are being mobilisedelsewhere with sporadic progress.Bougainville is not yet a black hole. Singirok's decisive andwell-timed action has averted a major disaster, and there i aresourceful quest for peace at village level. The military hasshown it too wants a political solution. It is up to Port Moresbyto provide a framework for this, and that means compromiseover the status of the province.•James Griffin is professor emeritus at the University of PapuaNew Guinea.Brother Howley's work can be encouraged at PO Box 4205,Boroko, N.C.D., Papua New Guinea.Roo QuANTOCK " AM

OPENDRSTeenagePregnancyAbortionSex EducationSexuallyTransmittedDiseasesContraceptionTeenage SuicideCOUNSELLING AND EDU C ATIONAL SERVICES INC.With 100,000 abortions annually in Australia, morethan 1 in 3 teenage girls becoming pregnant, STDsspreading rapidly among young people, teenage suicideat an all time high, it's easy to become despondent.f ilms, TV, Radio, Music and government departments are spendingmillions of dollars promoting lifestyles and programs whichaggravate and even cause related problems cg the "Safe Sex"campaign.What ca n you do?Have faith! And support tltis appeal.Open Doors, is an ecumenical Christian Group involved inresearch, education and counselling in all these issues· and more.Open Doors Counselling and Educational Services• successfully makes educational programs based on traditionalChristian values. We address all these issues, promoting thefamil y, marriage and keeping sex fo r marriage, ancl our programsarc in 4,000 Australian primary and secondary schools.• provide specialist counselling for pregnant women/girls,teenage rs, couples and families on relationship issues· c risispregnancy, marriage, abortion, STDs etc.• publis hes articles in our journal l.ife in Focus which is sentfree to every secondary school and to Australia n media andpoli ticians.• has a special pregnancy loss counselling and researchservice, helping women w ho arc expe riencing grief afterpregnancy loss through abortion, miscarriage or stillbirth.Open Doors has the staff, the programs, the faith and the motiva tion. 13ut we need to raise anextra $500,000 over the next 2 years to main tain existing services ancl to meet increasing demands.-- ---~ ~~ ~~ -~~ l~~~ ~~~ ,-~l~t- ~~- ~~ ~ -C~~ ~: :~C-t~1~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~ :~1 ~:~ ~~~l~~~~~~~ ~~S~ t-C~ ~ -t~~~:~l~:~ :~C~1~: -g~ :: ~~~1~~: ~ :~--Add ress .................TitleChristian NamePlease accept my D Cheque D 13ankcard D Mastercard D Visa Donation for $ ............... .Ca rel NumberD D D D D D D D D D D D D D D DMake cheques payable to Open Doors PO 13ox 610 Ringwood Vic 3134 (Donations arc tax deductible).for information about our counselling ami educational work write or telephone (03) 9870 7044Patrons: Most Reverend G Pell Catholic Archbishop of MelbourneRight Reverend James Grant I3ishop Coadjutor in the Anglican Archdiocese of Melbourne6EUREKA STREET • MAY 1997

l~ How~'' "o~~m:i< ~'~~til~~~~ ~:mon '~'·Tho fU•t mund• of publicstrategy now-a piece of cleverness which service cuts, for example, hit rural regions hard. For many a countryshowed him to be like any cynical old politician.town, the closure of a social security office and the closing down offBut even as the strategy has unravelled, making almost every- a labour market program was just another blow in a cycle that hasone look rather unattractive, Malcolm Colston has been delivering seen those towns lose banks and other private sector servicemore to Howard than the extra vote which makes up a Senate institutions, then population, then teachers and policemen.majority. So intense has been the focus on the affair that the Budget In some states this has been compounded by simultaneousprocess has been able to go without any public attention, hardly a assaults at all levels of government. Rural and provincial politisingleleak and not a little Liberal and National Party discipline. cians have had a hard time explaining to their voters that it's all forJust whether, however, this is a good thing depends on how long the greater good.term John Howard's strategies are.Yet many of the economic zealots within government are stillThe first Howard-Costello Budget was a much more public keen to have unilateral tariff cuts, which will have further andprocess, which suited the Government well, even if it did not immediate sectional impacts. Public sector job and program cutsappreciate the amount ofleaking by a public service being set up for are still being planned, without much sign of increased privateserious cuts. First, the cuts could all be Paul Keating's fault, sector activity to pick up the slack or any job creation as privatebecause of the famous black hole: all that Peter Costello had to do, enterprise performs functions hitherto carried out by government.as he gleefully flung away the election sheep's clothing, was to It's within this context that the recent Defence Efficiencypretend that these were austerities forced as reluctant duty upon Review was somewhat bemusing. Its proposed defence efficiencieshim by Labor profligacy and dishonesty.involve the centralisation of a host of defence facilities, with a littleThe leaks, even the unexpected ones, meant that by Budget day base here, a piece of the Army's support services there, a bit of thethe public was well prepared for the bad news and prepared to focus Air Force's infrastructure over there all marked down for closure.on the compensations. Moreover, the Budget was based on doling In those communities, the defence presence meant jobs notout nearly all of the nasty medicine early in the political term, in only forthe servicemen and women butfor a wider community. Yetthe expectation that both the economic and the political cycle the rationales for the cuts were pretty sketchy, not least in a timewould permit successor budgets that proved th e efficacy of the when transport and communications infrastructure are such thatmedicine and delivered some payback for the voters just before alocation doesn't matter much at all. But it was endorsedtriumphal re-election.0by Government without the blink of an eye.Alas, Costello's advisers got some of their own revenue sumswrong and the Government now has its own black hole.NCE UPON A TIME, OF coURSE, the process of locating suchWith so much dogma and credibility focused on balanced or facilities involved some conscious pork-barrelling, just as thesurplus budgets, Costello has another year of tightening, making location of social security offices or community services did.the political equation a closer-run thing. This is the more so given Politicians lobbied hard to do something for their electors. An areathat the source of his shortfall comes from the patchy nature of feeling the pinch, say because of drought, structural change or theeconomic growth and the uneven way it is distributed.collapse of a financial institution, might be given some majorSectors which h ave traditionally fueled business and consumer government project as a piece of conscious Keynesian pumpconfidence,and which traditionally provided jobs growth, have priming and levelling out. Now, it seems, government is consciouslybeen visibly lagging. The retail and the housing sectors are doing stripping itself of just uch powers of intervention. The furtherbadly. The global economy, which the bipartisan architects of the changes to the financial sector recommended by the Walliseconomic market reforms have made so crucial to Australia' committee will take away even more.prosperity, is not looking as well as it did.The zealots would say that the capacity of government toAnd, in part because of the government changes to industrial achieve outcomes by the old levers is now much reduced, becauserelations, job insecurity is inhibiting consumer spending, which is of our vulnerability to international competition, and that marketin turn impairing business confidence. This then threatens that solutions are often better ones than well-intentioned but clumsyresurgence of private sector activity which thefantasists of modern interventions by government. To an extent they are right, but someeconomic theory think will flow automatically once the public of Government's impotence derives from their own strategies.sector is taken off its back.What has this to do with the budget and Malcolm Colston?After the ritual spending slashes of health, welfare and educa- First, the Government is taking a great risk if it thinks that sometion, and with defence still apparently quarantined from any cuts, Budget-day prestidigitation will amaze, delight and persuade evethemost obvious way of making up budget deficits is by attacking ryone. We've had that from Paul Keating and he could not delivertaxation expenditure-the myriad of concessions and deductions either. The more open the Budget process and the more time andavailable for business and families. But many of these are difficult attention given to expectations, the more likely a Budget strategyto justify on equity grounds and the revenue they promise has a will be accepted.great capacity to evaporate. Allow tax concessions for personal And this is even more the case when the electorate is cynical notsuperannuation, for example, and the punters will put their money only about the capacity of politicians to deliver outcomes, butthere; take it away and they will switch it elsewhere, probably suspicious and cynical about the character of the politicians themfasterthan the tax man can catch it. selves. The higher they are, the lower they fall. •It's a difficult juggle, the more so when it is orchestrated aroundthe electoral cycle. But so cocky are some of the players that dogma Jack Waterford is editor of the Canberra Times.VOLUME 7 NUMBER 4 • EUREKA STREET 7

LEITERSNo excuseFrom John EastMichael McGirr's article on sexualabuse within the Catholic educationsystem (<strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong>, April 199 7) is,I think, a generally fair and compassionateattempt to view this verypainful issue from all sides, and he isnot sparing in his criticism of thoseinstitutional flaws within the Churchthat made exual ab use not only possible but inevitabl e.I was however very disappointedthat one paragraph-something of anapologia for the Catholic educa tionsystem in this country-was highlightedon the inside front cover of thatissue. There were in my opinion otherparagraphs in that article which betterdeserved such prominence. Moreimportantly, I disagree with McGirr'sattempt, in the final sentence of thatparagraph, to blame the whole countryfor the prevalence of sexual abusein the Catholic educa tion system. Thesentence in question runs thus: 'If ali fe of personal privation forced someindividuals into distorted behaviour,then th e whole country is s ubtlycomplicit.'Thi i , I believe, quite unfair, as theproblem lay very much within theinstitutions of the atholic Church, andnot in Australian society as a whole. Ifwe look at the issue from the point ofview of the abuser, then the mainconsideration which kept him (or her)within their life of 'personal privation'was the knowledge of the ostracism bytheir Catholic family, friends andcolleagues which would be their lotupon leaving the order, to say nothingof the threat of ecclesiastical sanctionsif perpetual vows were broken.From the point of view of thevictim, the only adults in whom anabused child could confide-teacher ,parents, parish pri est, family doctorwouldprobably all have been Catholicswho had been thoroughlybrain-washed into believing that theirChurc h and their clergy wereincapable of error. And had one ofthose adults dared to complain to theecclesiastical authorities, they wouldprobably, at best, have been fobbed offwith bl and assurances, or, at worst,have been threatened with loss of livelihoodor denial of the sacraments ifthey did not hold their tongue.McGirr's suggestion tha t thecountry as a whole was guilty of theEurelw <strong>Street</strong> welcomes lettersfrom its readers. Short letters aremore likely to be published, andall letters may be edited. Lettersmust be signed, and shouldinclude a contact phone number

This month,the writer of eachletter we publishwill receivea <strong>Eureka</strong> <strong>Street</strong> T -shirt.Marlon Branda couldn'tmake it look any better.any he lpful, though invented "act"could be justifiably workedaccordingto their cultured and literaryconventions.'Barrett concludes: 'Crossan and hismates are only clearing the ground offundamentalist claims; they need to gobeyond the trifling impedimenta andconsider why all the impedimenta arethere in the first pl ace . ... they are verymuch more than a tiny amoun t of factwith en ormou s dollops of faith.'Barrett does not say where the faithreally fits into the story.The irony for m e is that Barrettmakes h imself fit Adams' criteriaperfectly. H e h as described a view ofgospel form a tion whic h canno treasonably form the ground of faith,except the faith that Barrett claimsfor him self, th at ' this Jesus couldcope with life and its problem s; wenever knew anyone who could copebetter. 'I wonder whether the world is notbetter served by Adams' ' torturedm ind' and 'certain longing' than byBarrett's reduction of Jesus to the goodexample who 'could cope with li fe andits problems.' M y suspicion is thatm ost people would relate better toAdam s than to the Jesu s given inBarrett's analysis.A further irony for m e is that m ydoctorate is in certain aspects ofpsychology and religious symbolism .I rea d fo r this in the theology department of Exeter University, UK, underthe professorship of David Catchpole,one of the current stream of thoseinterested in ' the search for thehistorical Jesu s'. In 'deference' toCatchpole I called one chapter of m ythesis, 'The Search For the NonHistorical Jesus'. One da y the realJesus will stand up as asked.Kim MillerWagga Wagga NSWNo nonsenseFrom fohn DoyleFor some time now I have been tryingto get action about defective signs. Iwant signs that are easy to see and easyto recognise.Signs of th at kind make even ashort journey safe and comfortable.N ow, punctuation m arks and whitespaces are the reader's road signs. Ofrecent years they have increasinglybecom e obscured by the letters aroundthem and increasingly hard to recognisewhen they are sighted. The veryphysical process of reading has becometedious and laborious, even for eyesthat are neither tired nor lazy.Concern for the Republic of Letterssuggests a campaign to h ave allpunctuation marks separated by an enspaceand sentences by an em -space.This simple return to an older, hotmetaltradition would greatly relievestrain and stress, and fit well w ith thewider pitch and wider spacing that ibecoming m ore common in goodbooks and m agazines.John W. DoyleKew, VICNo problemFrom Warren HortonDirector General, National Library ofA ustraliaRobert Barnes' article 'The N ationalLibrary of Au tralia: From Big Bang toBlack Hole' (Eu reka <strong>Street</strong>, March1997) continues his ca mpaign againstour strategic policy directions. He hasn ow publish ed over 25 articles orletters in the m edia on these issues.Barnes lam ents that h e hasreceived little support in thiscampaign, saying 'equally tragic hasbeen the almost complete silence ofscholarly institutions elsewhere in thecountry. N o academy, learned society,university or library association hasm ade any public statem ent on theN ational Library's collections or electronicpolicies.'There has indeed been little com ment. N ot one academic in Australia,for example, subsequently commentedon the lea d article about our collection/accesspolicies in the importantCampus Review weekly issu e of 15May, 1996. The 'controversy' concerningthe National Library about whichBarnes constantly fulminates seemslargely confined to him and a smallgroup of other Canberra users.The Library in its 1993 StrategicPlan Service to the Nation: Access tothe Globe said its role was changing,with a stronger emphasis on collectingmaterial relating to Australia andAustralians, o ur prime collectingresponsibility, w hile continuing tobuild the resource sharing infrastructurefor the Australian library system.The time has passed for us to aspire toa coll ection from all over the world.The growth of the higher educationlibrary system over recent decadesencourages shared collection building,and technology increasingly allows usto acquire m aterial, especially journals,from elsewhere. But we stillspend heavily on m aterial from overseas,including world class Asian andPacific collections. And we cherish oursplendid printed collections.Libraries are changing profoundly.The recent major review of the ANULibra ry commented on the greatgrowth since the 1982 review in thera te a t which knowledge is beinggenerated. While no research library,no m atter how well resourced, nowm eets all its own information needs,technologies are em erging whichpromise greater access to informationirrespective of its physical location.T he review said 'This has impactedon university libraries world wide andh as even led na tiona! libraries toreassess their goals .. . Many, like theNLA, have had to focus more closelyon their primary goal which is to collecton matters directly related to theirown country w ithin a set of fairlyclosely defined interests'.The main thrust of Barnes' arguments is that the National Library hasnarrowed its collecting ambitions overrecen t decades. We w ould describewhat has happened as sensible policychanges refl ecting the opportunitiesand constraints outlined above.LETTING GOAND MOVING ONIndividual or groupcounselling for peopleexperiencing painfullife changesWinsome ThomasB.A . (Psych), Grad. Dip. App. PsychPhone (03) 9827 8785Fax (03) 9690 7904V OLUME 7 N UMBER 4 • EUREKA STREET 9

The world we now operate in is quitedifferent to those few years in the late 1960searly 1970s when the Library acquired theSperos Vryonis and some other form ed overseascollections. We have made no similarpurchases for 25 years, and are unlikely to everdo so again, and nor has any other Australianlibrary. This is simply a reflection of reality,and our primary interest has to be Australianspecial materials including manuscripts,pictures and oral history. Acquiring andservicing this m aterial is also a verylabour-intensive activity. Barnes himself says'In retrospect, it could well be argued that thelibrary took on too many responsibilities forits funds to support.'We steadil y cu t back purchasing ofoverseas print material throughout the 1980s,beca use we operate under the same costpressures and economic restraint affectingall other Australian libraries andCommon wealth-funded institutions.The Library has no m ore chance ofavoiding them than any university orother public institution, and to arguewe have failed to convince the Government'we were worth supporting fully'is just fanciful. And we are alrea dy thesecond highest revenue earner for anynational library in the world. We nowhave 500 staff as opposed to 650 in 1985,who by their ingen uity and goodm anagement practices have met grea tlyincreased demands on all our servicesover those years. But we could not goon like this.T he 1993 Strategic Plan reflects verycareful thought about what theLibrary's key strategic priorities should be inthese circumstances. In the case of collectionand electronic access policies, where theissues are far more complex than in past bettereconomi c times and with only print materialto consider, the title accurately refl ects oura mbitions. We still aim to collect printexhaustively for the Australian and worldclassAsian/ Pacific collections, and judiciouslyfrom elsewhere in the world againstthe objective of being 'the world's leadingdocumentary resource for learning about andunderstanding Australia and Australians,linking closely with other sources ofinformation throughout the nation'.The last phrase is important, beca use itreflects the fact that we work in a highly coordinatedenvironment. Australia is extraordinarilywell served now in terms of researchlibrary collections compared to two decadesago, reflecting the great growth in the highereduca tion library system . We spend one inevery 20 of the dollars now spent onAustralian research library collections, ascompared to one in every four 30 years ago,and there is loca tion information for over 20million volumes in over 2,000 libraries in ourABN system. Concentrating on our primecollecting responsibilities in a nationalresource-sharing environment where everyonehas funding problems, rather than anyfoolish pretence we are the only library in theworld apart from the US Library of Congressbuilding a world collection of print materials,is obvious] y sensible.This policy has meant significant cancellationsof overseas print materials. In the caseof seria ls we have in the last two yearscancelled some 13,000 overseas subscriptions,although we still subscribe to som e 13,000titles and acquire another 13,000 by gift andexchange and other methods. We would withstaff decreases probably find it impossible tonow ph y ically process that material anyway,but the decision has to be seen in the contextof electronic developments includingfacsimile and the Internet, and establishmentof dedicated document delivery services. TheAmerican CARL UnCover service alone, towhich we add Australian content, offers 24hour full text access to over 20,000 titles.While it is a minor issue, our subscriptionto Antiquity (w hich is also held in the ANULibrary in Canberra) was not 'discreetly reinstated,aft er protests in the national Press'. Itwas cancelled in error on 27 july 1995 andreinstated on 16 August 1995 . Barnes' letterin the Canberra Times complaining we didnot ubscribe to it was published on 24September 1996. I accept he did not thencompreh end the reinstatement from ourcatalogue entry, but he certainly does now.Barnes says that the user has to meet thecosts, and that such developments are ' noadequate substitute for the traditional library,where the researcher can browse freely in awide range of journals'. We still of course takea huge number of journals, but this is a veryCanberra-based argument. The small group ofCanberra residents vigorously opposing thesechanges, who can of course visit the Library,have never commented on the fact that allinter-library loan use since 1987 has attractedsubstantial charges. We are still exploringways to carry these costs for our prime clientgroup of the serious researcher needing accessto the National Library. However universitylibraries have the prime responsibility ofm eeting the libra ry needs of thei rcommunities.We believe there is a problem in theoverall in take of overseas monographs inAustralian research libraries, although ourpolicies have not caused it. We have beentalking to the academies, university librariesand other interested parties about how thismight be explored.We do strongly support the concept of theDistributed N ational Coll ection, unanimouslyendorsed when first articulated at the Au tralianLibraries Summit of 1988, and since alsotaken up by the Commonwealth Governmentand cultural communities. In the simplest terms this concept argues librariesshould think of the nation's libraryresources as one co llection, comprehensivelyin the case of Australian materialand selectively in relation to therest of the world, and while acceptingevery library has its own prime clientgroup, develop coll aborative resourcesharingpolicies in the national interest.We have been disappointed thatthere have been few contractual collectingagreements to date under thatpolicy, although the informal agreements,as in the health sciences subjectarea for instance, should not beunderestimated.But the DNC concept is far widerthan just co llecting agreements. Itincludes the National Bibliographica l Databaseoperating through ABN of Australian libraryholdings, Conspectus description of coll ections,national preservation strategies, national access,electronic and inter-library loan protocols,and a raft of other collaborative activities wherethere has been notable achievement. It is pleasingthat the N ational Scholarly CommunicationsFomm, whose m embership includes thelearned academies, libraries and other relevantparties, is soon to hold a major forum to furtherinvigorate the concept.It is said that our 'total spending on allprinted material (even including theAustralian collection) has fallen to about $5million a year, or only 9 per cent of theLibrary's budget'. Almost all Australianprinted m aterial is of course acquired freeunder far-sighted legal deposit laws. Wh enthis, overseas free material and TaxationIncentive acquisitions are notionally castedin, our collections budget is the largest inAustralia. And we are a totally self-containedorganisation, with a range of responsibilitiesfar wider than any other Australian library.This is 9 per cent of a 1995/96 budgetincluding $24m for 500 staff, $2m on running10 EUREKA STREET • MAY 1997

our building, about $6m for asbestos removalfrom the building, $8m paid by other librariesfor ABN, and funding for many other activitiess uch as the National Portrait Gallery,publications and so on.Your rea ders may find it useful to have abrea kdown of our collections expenditurefrom 199 1/92 to 1995/96. This shows a 47.6per cent cut in o verseas expenditure(excluding Asian), a 9.65 per cent increase inAsian expenditure, a 17. 1 per cent increasein Australian printed material (m ost comingfree through legal deposit), and a 42. 1 per centincrease in Australian special materials(manuscripts, oral history, pictorial, m apsetc.) expenditure.There is little point in comparisons overwho spends what on library collections,unless the libraries and their responsibilitiesare broadly similar. The Library of Congressspends less than 9 per cent of its budget oncoll ection s, whi le the Bayeri sche Staatsbibliothek(the Bavarian State Library) haslittle resemblance to us. It does not forexample run any service like ABN, and itcounts its collections intake differently.Barnes in his article and elsewhere hascomplained about our consultative process in1992 for the Strategic Plan, saying we ignoredcriticism then and hid ou r true intentionsabout the collection policies. It is impossibleto refute this beyond saying I do not beli eveeither allegation to be true. We can always dobetter in consulting, but it should be notedthat the December 1993 issue of our NationalLibrary of Australia News, 7,000 copies ofwhich were distributed around Australia,focu sed on th e Strategic Plan includingreprinting the strategic priorities.We are not able for legal reasons tocomment on the WORLD 1 project, includingpossible funding outcomes, during thepresent termination negotiations. But we didnot divert collection funds to it. We arecommitted to full support of the AustralianBibliographical N etwork (ABN) whichsupports over 2,000 Australian libraries, untilthe replacem ent Networked Services Project,which has been strongly supported by theCounsellingIf you or someone you know couldbenefit from professional counselling,please phone MartinPrescott, BSW, MSW, MAASW,clinical member of theAssociation of Catholic Psychotherapists.Individuals, couplesand families catered for:Bentleigh (03) 9557 2595library community, is implem ented. Thiswent to tender in March.T he Council is responsible fo r Librarypolicies, and has not 'been almost totallysilent', since I am its executive member andspea k publicly on its behalf. Recent membershave included people of the calibre of SirNinian Stephen, Sir Anthony Mason,Professor Stuart Macintyre, Rodney Cavalier,Julia Kin g and Geraldine Paton, with am e mber e lected from each house of th eParliament. They hardly match the comment'one wonders whether the Council is anythingmore than a rubber-stamp for decisions madeby the Library's administration'.The Library is very publicly accountable,including to th e Parliament. Most of therelevant material can be found on our homepage at http://www.nla.gov.au and is alsorea dily available in print form.What is depressing in this particulararticle is the denigration by Barnes of theprofessionalism of the many Library staffinvolved in developing the collection, accessand electronic m aterials policies of the lastdecade. Most have le ngthy professionalexperience in the National Library or otherlarge Australian research libraries, and allbring integrity to their work. The Library hascategorically denied the assertion that theyshaped the collection policies to reflect theprevious Government's Asian strategies, butBarnes s till says ' this disclaimer isdi singenuous'. He al so says that 'The Library'scollection and electronic policies have asuperficial plausibility, but they are thedecisions of bureaucrats, not scholars andresearchers.' Our staff are proud to be part ofthe Commonwealth bureaucracy, while alsodriven by professional values . They developpolicy recommendations for the Council inan environment demanding constant change,difficult decisions in h ard economic times,intellectual rigour and the courage to takesignificant risks with technology.The world has changed dramatically in thelast decade. Our values and culture are builton print, but we recognise that technology,including the extraordinary rise of theInternet, gives us undreamt of opportunitiesfor access to the world's information.We must now concentrate on our primarytasks set out in our Strategic Plan, includingthe h eavy responsibility of building theAustralian collections of both print andelectronic materials.The reason that Barnes may have attractedlittle support is that those interested inAustralian libraries understand this turbulentand changing environment. They m ay not anymore than us have all the answers, but theysee little profit in just looking back to thevanished world of a gen eration ago.Warren HortonCanberra, ACTMELBOURNEUNIVERSITYPRESSIn the Midst of LifeThe Australian Respons e to DeathRevised Editi onGRAEME M . GRIFFIN ANDDES TOBINA useful, well-informed compassionatebook on a taboo subject, forprofessional and general readers.From lively stories of colonialburials, mourning etiquette andgravestone epitaphs-to thornyco ntemporary questions. How todeal with grief? What are the practicalities when a relative dies? Doyesterday's rituals meet today'sneeds? Paperba ck $29.95Manning Clark'sHistory of AustraliaTenth Anniversary Limited EditionABRIDGED BYMICHAEL CATHCARTThi s is a limited collectors' edition ofthe abridgement of Clark's sixvolumeclassic. As the narrativeranges from 1788 to the thresho ldof World War II , Michael Cathcartnever loses sight of Clark's sympathiesand understanding. All themagnificence of the original isretained.Hardback in slipcase, $85.0075 YEARS~~MUP1922 1997268 Drummond <strong>Street</strong>Carlton South 3053Tel 9347 3455Fax 9349 2527V OLUME 7 N UMBER 4 • EUREKA STREET 11

I WANT TO INVEST WITH CONFIDENCEAUSTRALIANe-thicalAgribusiness orreafforestation.Mining or recycling.Exploitation orsustainability.Greenhouse gasesor solar energy.Armaments orcommunityenterprise.TRUSTSInvestorscan chooseThrough the AE Trusts youcan invest your savingsand superannuation inover 70 differentente rprises, each expertlyselected for its uniquecombination of earni ng s,environmentalsustainability and socialresponsibility, and earn acompetitive financialreturn. For full detailsmake a free call to1800021227lnl'estments in the .\ustralia 11 l:'thical trusts canonll' be made thruuuh the cu rreJII pros{Jeelusregislered ll'ilh the .\uslraliall SecuritiesCo mmission and tll'ailableji·omAustralian Ethicalllwestment Ltdl 'uil 66. Ca nberro Busines.\ CentreBradfield St. IJ0/1'1/er .-\CT lWlAustralianBook Reviewtlze essential magazinefor Australian booksin the May issue:Marilyn Lake on Icons, Saints & DivasIvor Indyk reviews Brian Castro's StepperDon Anderson reviewsRichard Lunn's Feast of All SoulsRobert Adamson onGeoffrey Lehmann's poetryJohn Tranter on Kenneth SlessorNew Subscribers $44 for 10 issuesplus a free bookPh (03) 9663 8657 Fax (03) 9663 8658No confidenceFrom Don LinforthIn the article by Margaret Simons onSenator Cheryl Kernot (<strong>Eureka</strong> SLreel,March 19971 the Senator is reported assaying that a joint sitting of the Senateand House of Representativesfollowing a double dissolution 'wouldhave the numbers to push througheverything that has been on the tableand hasn't been passed by the Senatebeforehand'.In my reading of Section 57 of theConstitution, the only measures that ajoint sitting can di scuss arc those whichhave been passed twice by the Houseof Representatives and twice rejected (orunacceptably amended or not passed) bythe Senate, with three months' intervalbetween the two presentations tothe Senate. I think these measures haveto be enumerated in the documentationfor the double dissolution.Furthermore, a double dissolutioncannot take place less than six monthsbefore the expiry of a House of Representatives,that means Mr. Howardcannot call one later than October 1998.Don LinforthHampton, VICNo standingFrom H.f. GrantSuccessive Federal Governments fromthe '80s including the present cannotescape the odium attached to th eall eged rorting of pari iamcntary travelall owances especially by Senator MalColston. This is compounded by thedifficulty that the Labor Party is experiencingin regaining its social soul andthe Coalition in trying to find it.T he Language used on the subjectby the Prime Minister, the Leader ofthe Labor party and their coll eagueswas aptly described by George Orwell( 1903-19501, English satirical novelist,essayist and critic in these words:'Po litical language-and withvariations this is true of all politicalparties from Conscrva ti ves to Anarchists-is designed to m ake liessound truthful and murder respectable,and to give appearance of solidityto pure wind.'Equally the late US PresidentHarry Truman who knew andrespected what the public expected ofpoliticians was wont to quote HoraceGreeley ( 181 1-18721, founder editor ofthe New York Times: 'fame is a vapor,popularity an accident, riches takewings, those who cheer today maycurse tomorrow, only one thingendures: character.'Belatedly the Prime Minister hasnow announced that Governmentwould introduce reforms to the systemfor vetting pa rl iamentary travel all owances.Reforms to be effective, however,should be complete and wide rangingand include arrangements outside theParliament or Government that all owan independent committee or tribunalto initiate, investigate and decide oninstances of malpractice relating to allparliamentary allowances andprivileges.Action of this nature would be am ea ns of re-affirming the high principlesand practices which politicians,commonly profess to subscribe onelection to office as well as helping torestore Parliament's standing and theGovernment's credibility.The latter is under siege given the'pain with ga in ' measures in place andin prospect for the thousands of agedand deprived, unemployed, underemployedand low wage earners withoutallowances or superannuation.H.J. GrantCampbell, ACTN o illusionsFrom fohn KerschJust prior to the col lapse of the former,corruption -riddl ed National PartyGovernment of Queensland, legislationwas enacted to grant holders ofPastoral Leases automatic 20-yearextensions.Several people, including myself,strongly rcsi ted its application toleases deemed to be ' multi-livingarea' in size. On ex piry these werethe heritage of many young ruralAustralians to have the opportunityto draw a o ne living-a rea bal lotblock. The enthusiasm for this processwas demonstrated by the 3,000applicants for the best of such blocks,in the Injune area.We were assured by the Partyheavies that the extension would applyonly to aggregations under threeliving-areas. In the finish, aggregationsof up to even seven living-a reassecured the extension (for exampleChatsworth Sth in the Cloncurryregion, Far North Queensland I.The major beneficiary of thisgolden-handshake was the McDonaldfamily with aggregations possibly in12EUREKA STREET • MAY 1997

excess of 40 living-areas. It is likelythat the next major beneficiary was theA. A. Company.Can I therefore ask the followingquestions?As the then Vice-President of theQueensland National Party, Directoron the board of A. A. Company andprincipal of the McDo n ald familycompany, did Don McDonald in factdraft the extension legislation ?Now the Federal President of theNational Party, is h e using the currentWik confusion to secure freehold overthis country, as I heard him suggeston an ABC radio interview on April8?Thus completing the rape of theaspirations of many potential younglandholders.John KershMaxwelton, QLDNo can doFrom Fr JM GeorgeFr J Honner (ES, March, 97) recommendedMichael Winter's article, 'ANew Twist to the Celibacy Debate'.Winter reduces early church motivationfor celibacy to 'morbid attitudesto sex' and 'primitive taboo'. Hisviews are not 'new' but are found inold celibacy studies by J.&. A. Theiner(1828), H. Lea (1867), F.X. Funk (1897),etc.French Jesuit historian, ChristianCochini and oth ers, today, wouldreject Winter's reduction in the lightof mainstream celibacy-doctrine andpraxis within the early church.Many early church married laity aswell as married clerics abstained frommarital acts in penitential preparationfor Eucharist. Moreover, just as abstinencefrom food did not imply thateating was m orbidly dishonourable orprimitive taboo, neither did pre-Eucharisticmarital abstinence imply negativitytowards the conjugal act.Indeed the wider church hadreject ed Manichean , Gnostic,Montanist and Encratite h eresies fordenigrating marriage. True! among the85 eastern and western Church Fatherswere some with negative attitudes tomarriage. However those limitedviews did n ot impact upon the abovementioned motivations for abstinence.The early church regarded marriedlay and clerical pre-eucharistic abstinencefrom food, wine and conjugalacts (totally good in themselves) asincreasing the efficacy of liturgicalprayer ('by penance'). Unlike strictrules of fasting, conjugal pre-eucharisticabstinence was merely a 'counsel'for married laity-a matter of personaldecision.'Efficacy-motivation' stood behindpermanent clerical celibacy. The earlychurch understood priests as incontinual mediation for the people.This 'mediation' was seen as more efficaciouswith permanent celibacy. Later,other motives were underlined, forexample, sacerdotal configuration to thecelibate Christ, 'Apostolic origins', etc.Cochini in his OriginesApostoliques du Celibat Sacerdotal,discusses wider issu es, such as thecontroversial Trillion Canon 13 mentionedby Fr Honner. Cochini exposesthe fictitious 'Paphnutius intervention'at Nicaea (uncritically acceptedby Winter). He distinguishes two categoriesof early celibate priests. He alsoclarifies 'Ritual-purity' terminology inits use for old Levitical priesthood andNew Testament presbyterate.The former professor at InstitutCath olique de Paris, the late Jean CardinalDanielou described Cochini['sinitial research as 'a true service to thechurch'. Henri Cardinal de Lubac,another outstanding scholar, describedthis 'serious and extensive research ...as of the first importance'. (Winter'sviews- popular today in scholarlycircles-need to be challen~ed 1 ).John M GeorgeWaverley, NSWNoWikFrom Michael PolyaFrank Brennan's article on Wik{E ureka <strong>Street</strong>, April1997) is misleading.Even if Aborigines could claim thevalue of the land in compensation inthe event of Native Title being extinguished,the value of the land wouldnot be too great, partly because itwould be generally unsaleable, or onlyto other Aborigines and thereforecould n ot be used as security for a loanand in any case the value would bediminished by the value of compensationthat would be payable to lesseesfor improvements, which in manyinstances would greatly exceed thevalue of the land itself.Native title does create a system ofland tenure akin to that of entailedestates in Europe, which only benefitsthe m ost parasitic and useless strata ofsociety, to wit the hereditary nobility.Michael PolyaWatson, ACTAustralian Options * *Journal of left discussions fo r * *social justice and political change.Issues I-8 have included themes: Unemployment,Privatisation Plunders, Future of Unions, ElectionQuestions, Green. Issues in a Brown. Land,Rich vs Poor, ABC.With writers: Pat Dodson, Belinda Probert, Mary Kalantzis,Hugh Stretton, Ted Trainer, John Langmore, Eva Cox. JackMundey, Ken Davidson, Meredith Burgmann;Next Issue: The Attack on YouthSubscribe NowName/ : ......................... ........ .. .. .... .... .. ... ............................... .Address: .. .............................................................................. ................................................ State!Postcode: ................. .. .. ..Phone: (H) ................................. (W) .................................. ..Email: ... .. .. .. .......................................................................... .I enclose $15 ($10 cone.) for subscription for one year (four issues p.a.)Cash 0 Cheque 0 Credit Card 0Payment by credit card:Please charge my (circle one). Bankcard Visa MastercardNo.: DODO DODO DODO DODOExpiry date: .................. ............. Amount: $ ..........................Signature: ....................................... .................. .Return to: Australian Options, PO Box 431, Good wood SA 5034,L------------- ----------------------------------------------------------------~§jThe Halifax-Portal LecturesThe Second Series of Ecwnenical LecturesSponsored by the Catholic and Anglican Bishops of NSW6th May 199713th May 199720th May 199727th May 1997"The Orthodox Churchesin Australia in 1997"ARCHBISHOP AGHAN BALI OZIAN,Armenian Apostolic Church"The Anglican Communion onthe Eve of Lambeth"(World Wide Ang li can Communion)REv DR BR UCE KAYEGeneral Sem:tary, the General Synod of Australia''The Uniting Church in Australia in 1997''REv DoROTHY McRAE-McMAHONDirector for Mi ssion for the Uniting Church inAustralia"The Legacy of Halifax and Portal"Ms DENISE SULLI VANSecretary of the Bishops' Committee forEcumeni cal and Interfaith RelationsThesday Nights at 7.30 pm-FREE ENTRYSanta Maria Del Monte School Hall, Strathlield, NSW(cnr Carrington Ave and The Boulevarde)Refreshments served at 7.15 pmAnglicru1 Viscount Charles Halifax ( 1839-1934) was involved in mosl questions facingthe Anglican Church of his day. Abbe Etienne Ponal ( 1855- 1926), a French Yincentian,met !he Viscount in 1889. Their friendship led to dialogue about Church reu nion. TI1eMalines Conversations ( 192 1-1926) between Catholics and Anglicans hosted byCardi nal Mercier was their most notable success. TI1ese two men express the spiritthai these current lectures seek to foster.FOR FliRTH ER INFORMATION CONTACT: SR PATRICIA MADI GAN OP,LI AISON OFFICER FOR I':CUMEN lSM. I' OLOlN(; HO USE

more remarkable was that during their staythe verdict acquitting the police officerscharged with the bashing of Rodney Kingsparked the LA riots. Naturally the restaurantwas packed when the evening newsbroadcast came on the TV. The hum gaveway to an uncomfortable silence as footagewas shown of people wandering the streets,randomly firing guns, and of the near-fatalassault of a truck driver pulled from his rig.It wa hard, then, not to notice that thegroups of sailors were split into racial groupsm ore often than not. Half an hour later theunease was gone and joviality returned. Butthe ghost of som ething past was there.The American military make it clear totheir charges that when at rest in a foreignport they are being watched and thereforemust be on their best behaviour. At leastthis is what Michael told me, a 20-year-oldfrom Milwaukee with whom a m ate and Iplayed pool in a Bondi bar. His friendsdrinking in the corner joined in and we talkedabout Vegemite and topless bathing and thedifficulties of speaking English in Japan.Michael was a terrible player, but that'sunderstandable when you consider that poolis not the ideal hobby for a sailor. He spentm ost of the time inspecting the pockets foran invisible plastic coating. Somehow theconversation turned to poverty and crimein American cities. H e shrugged at som ewell-intended but naive remark of mineand said that a young black man in theinner city feels taunted by the constant andvisible police presence. 'They think you'vedone somethin' ', he said, 'so you m ay aswell go ahead and do it'.On the Tuesday after Easter the USSIndependence pulled out of port. At thetime, Prime Minister H oward was inBeijing meeting with Li Peng and otherdignitaries. N ewsreports that evening ofthe concerns the Chinese leadership hasover our defence ties with the US weremarried with images of the aircraft carrierleaving Sydney Harbour.There is a black American rap groupcalled Public Enemy and they have an albumentitled 'It takes a nation of millions tohold us back'. -Jon GreenawayMoclz worlzIs there anyone among you who wouldhand bis child a stone when heasked for bread! Wlw would hand hischild a scorpion when sheasked for fish !Since the Prime Minister's announcement in February of compulsory work forthe dole, few details h ave em erged that tellus what the cheme will entail for jobseekers. Lack of detail on the program'sdesign and funding has resultedin delay of the proposed legislationin the Senate and its referralto a committee for review .What does this kind ofmake-work have to offer unemployedand young unemployedAustralians? Similar schemeshave been propose d andknocked back since the mid '80swhen the Hawke Governmentput up its 'CommunityVolunteers Progran1' for unem ployed youth. As political diversionsor vote winners, these schem espromise the low-cost political quick fix . Asa solution to the problem of unemployment in disadvantaged regions of Australiathey are little more than popularist strategiesfeigning a lasting commitment to themost vulnerable m embers of the community.In its m ost positive light, work for thedole could provide som e minimal benefitsto 'clients' and their local communities.Voluntary work undertaken freely andwillingly by individuals can serve to relievework tests for short periods in regions wherejobs are just not available. It can addressmotiva tiona! needs and help people participatemore fully in local life. It could evensecure a small number of jobs over them edium term. Typically, however, this kindof schem e has an extrem ely low capacity togenerate employm ent. Worse, it risks dam aging the employ m ent prospects ofindividuals by failing to provide thenecessary level of training and support towin secure and gainful employment at thesame time as exacerbating an image of thelong-term unemployed as being work-shy.Talking PointsStar trek theologyT he June 1997 edition of Pacifica, entitledFeminist theology: the next stage, is bein g guestedited by Dorothy Lee and Muriel Porter, andfeatures the works of a number of promjnentinternational theologians-some of them men.H ere is the list: Elaine Wainwright, PatJi ciaMoss, Dorothy A. Lee, D eni s Edwards,Graeme Garrett, Elisabeth Schi.i ssler Fiorenzaand Maryanne Confoy.Between them they tackle subj ects ran gingfrom the 01igins of women's asceticism throughevolution to a study of' the Procrustea n bed ofwomen's spirituality'.You can orderthe June volume by writingto The Manager, Pacifica, PO Box 271 ,Brunswi ck East, VI C 3057. T he cost is $20.AspiringSt Paoick's Cathedral in Melbourne is cutTentlythe focus for centenary celebrations that includea number of splendidly curated exhibitionsand a seri es of lectures. Professor Marga retM anion wiJJ be giving one of the Centenarylectures on Tuesday May 20 at Spm. On June17 it will be the turn of Gerard O 'Collins SJ.Michael McGirr SJ desc ribes the WilJjamWardell exhibition tlus month (see p5).Wardell, architect of the Cathedral, is also partof the focus of a new Life of the Cathedral,wtitten by biographer Thomas Boland.Fr Boland maintains th at the great neoGothic building does indeed have enough lifein its stones to justify the title. T he photographfrom the book, reproduced above, givesyou some idea of th e extent, and daring, of therestoration enterprise.If you are in Melboume do drop into theCathedral and see the res toratio ns andexhibitions for yourself. They are spectacular.V oLUME 7 N uMBER 4 • EUREKA STREET 15

The CambridgeCompanion tothe BibleHOWARD CLARK KEEBoston UniversityERIC M. MEYERSDuke University, NorthCarolinaJOHN ROGERSONUniversity of Sheffieldand ANTHONY J. SALDARINIBoston CollegeThe Cambridge Companion to theBible is unique in that it provides,in a single volume, in-depth informationabout the changing historical,social and cultural contexts inwhich the biblical writers and theiroriginal readers lived. The authorsof the Companion were chosen fortheir internationally recognisedexpertise in their respective fields:the history and literature of Israel;post-biblical Judaism; biblicalarchaeology; and the origins andearly literature of Christianity. TheCompanion deals not only with thecanonical writings, bur also withthe apocryphal works produced byJewish and Christian writers. Thehistorical setting for the entirerange of these biblical writings isdepicted and analysed in this volume,with abundant illustrationsand maps to assist the reader invisual ising the world of the Bible.253 x 177 mm c. 624 pp. 14 linediagrams 148 half-tones 14 maps0 521 34369 0 Hb $75 00~CAMBRIDGE~ UN!VloRSITY !'HESSIn the most likely of circumstances,this proposal will breach the Government'scommitm ent to place job seekers in realjobs. The looming perils of work for thedole make a sizeable litany for the disadvantagedjob-seekers and for the depressedregions towards which this scheme is targeted.The compulsion of a significantnumber of people into the scheme wouldundermine any positive features of truevoluntary work by deploying unemployedpeople as cheap labour, by reducing incomesupport entitlements to earned 'handouts',and by destroying any notion of a mutualobligation which underpins our society'scompensation for unemployment throughthe income support system.In addition, the scheme could easily beused to exclude people from active supportin the form of employment assistance andaccredited education and training whichare essential for accessing real jobs. It risksundercutting and replacing volunteers (thatis voluntary volunteers) and low skilledworkers in local communities and couldeasily spark industrial unrest and act tofurther vilify the unemployed. And thescheme will do absolutely nothing toenhance the skills base of depressed regionaleconomies if it is not supplemented bysubstantial, accredited, competency-basedtraining and integrated with robust industryand regional development strategies.Finally, the enforced involvement ofsocially marginalised and possibly disgruntledunemployed young people on 'touristwelcoming committees', m eals on wheelsservices, or in military training could causedamage to the young person, the industryconcerned and to the recipients of services.The destructive potential of such programsshould be obvious.The work for the dole proposal mayindicate the Government's difficulty indelivering on its promise of real jobs. Thereis still no sign that large corporations willstop retrenching or that small business willemploy greater numbers.Is the Government now sending themessage that it is short of an innovativestrategy to tackle 'the greatest single issuefacing Australia'?It is a real concern that the divisivemessage, inadvertently communicatedthrough this proposal as a policy positionon youth unemployment, is that thisGovernment is getting tough on' dole cheats'on behalf of the 'honest tax paying citizens'of Australia. This at a time when securejobs providing adequate pay and conditionsare most needed. - John FergusonTimorouson TimorPortugal cannot pretend that the events of1975 did not occur and that it is in effect inthe position of seeking to protect rightsover resources to which it has a legitimateclaim. It clearly is not: it is a displacedcolonial power. Nothing more- Oral submissions to t he InternationalCourt of Ju stice by the Australian Governmentrepresentative 1995 .Timorese people have Portuguesecitizenship so they have no refugee status:we can't have a phoney campaign aboutrefugee status from people who enjoy thecitizenship of Portugal-Paul Keating, 10 October 1995.I believe the position of the cuuent(Labor) Government in claiming that someEast Timorese asylum seekers are Portugueseis simply absurd and hypocritical.-Alexander Downer, March 1996.L EAsT TIMORESE, like Banquo's ghost,manage to return at inconvenient momentsin Australian Foreign Affairs. To the layobserver there may be little to question instating that someone from East Timor canbe a refugee. What about the Dili massacre,human rights reports and other evidence?Of course they can be refugees. However,for the Government, the question posessome difficult issues of refu gee law. Theris a case before the Federal Court nowworking through this complex matter.To qualify as a refugee, you mustestablish certain criteria. The definition isfrom the 1951 Convention Relating to theStatus of Refugees and it states that a refugeeis a person who:Owing to a well-founded fea r of beingpersecuted for reasons of race, religion,nationality membership of a particularsocial group or political opinion, is outsidethe country of his nationality and is unabl eor, owing to such fear, unwilling to availhimself of the protection of that country.So why is there a problem for theTimorese? The issue is one of nationality.The Refugee Convention is about protectingthose people who are not protected by theirown country. The theory is that a countryhas the duty of protecting its own citizens,so if it fails to do so, then other countriesinherit that duty. If a person has more thanone citizenship, then they ought to seek the16 EUREKA STREET • MAY 1997

protection of each country for which theyhave citizenship before seeking protectionfrom elsewhere. This is where the Timoreseare caught, as the Australian Governmenthas formed the view that the Timorese areentitled to citizenship from the former colonialpower Portugal.Indonesia invaded the Portuguese colonyin November 1975 and Australia was one ofthe first countries to recognise de factoIndonesian sovereignty over East Timor on20 January 1978. Australia then recognisedde jure sovereignty by Indonesia in February1979. However, the UN has not officiallyrecognised Indonesian sovereignty and Portugalremains the responsible authority inthe UN. Portugal claims it is still the dejure authority and that Indonesian rule isillegal. This claim may be legally interestingbut in reality, there is no doubt who isin charge in East Timor: there are manyIndonesian troops asserting who rules.Portuguese law on citizenship is quitecomplex, just to add a further confusion. In1974, the left-wing government in Portugaleffectively abandoned the colonies in Africaand Asia. After a brief civil war in EastTimor, the invasion by Indonesian troopssettled who was in charge on the island.Depending on the interpretation of Portuguesecitizenship law, some Timorese bornduring the time of colonial rule may beeligible for a Portuguese passport. Somehave taken this option and gone to live inPortugal. Until recently, Australia had ahumanitarian resettlement program whichhelped resettle in Australia Timorese whohad fled to Portugal. This year sees the endof that humanitarian program.The matter is further muddied by a casein the International Court of Justice.Australia and Indonesia signed a treaty todistribute rights for exploration in thepotentially oil-rich Timor Gulf. Portugalsued Australia in the International Courton the grounds that Australia should haveincluded Portugal in the treaty discussions.The Court is a means for nations to resolveissues without resorting to the military,however countries can decide not to acceptthe jurisdiction of the court and also ignoreits rulings. Australia accepted thejurisdiction of the Court but Indonesia didnot, so the case which affected the Timoresewas between Australia and Portugal.In the case, Australia argued that Portugalhad no legal or other right to claimsovereignty or rule over the territory asIndonesia had been in charge since late1975. Portugal had no authority to claim torepresent the people of the Island. TheAustralian position was clear: Indonesia isin charge in every t est of sovereignty.However when it came to determiningwhether East Timorese were refugees, theAustralian Government said that the peoplewere entitled to Portuguese citizenship, sothey should seek asylum in Portugal, notAustralia. Obviously we are interested inprotecting rights of mining companiesrather than rights of people.An interesting factor is that Australia isseeking to rely on a former colonial power inan era when European colonialismis nearly finished. AfterHong Kong returns to Chinain July, Macau remains as thelast place of European Colonialismin Asia. It is curiousthat in this post-colonial era,Australia is arguing that aformer colonial power shouldbe allowed to extend citizenshipto its former subjects,without consulting the people.The Timorese have neverhad the chance of self-determination,and given thechoice, one wonders if theywould elect to be a Portuguesecolony. Nevertheless,Australia, itself a formercolony and colonial power, isprepared to rely on the outdatedconcept of colonial ruleto avoid a difficult diplomaticincident.Currently around 1800 East Timoreseare awaiting the ruling of the Federal Courton this vexed issue. Whatever the decision,it is likely that the loser will appeal to theHigh Court for a final ruling. Such a decisioncould be at least a year or more away,if the High Court agrees to hear the case.Already the people have been waiting for adecision since late 1995, in legal limbo. TheTimorese community is not a large or richcommunity. More than 7000Timoresehavesettled in Australia.Since 1975 it is estimated that 200,000Timorese, a third of the population, havedied because of Indonesian rule. Theremainder have been heavily traumatisedby a long war and numerous incidents ofhuman rights abuses. Torture of suspectedindependence m ovem ent supporters iscommon practice, as are instances of extrajudicialkillings. Psychologists who haveexamined Timorese people report high instancesof trauma. We are now adding tothis trauma by forcing them to wait longer.If the Timorese are excluded on thebasis of nationality, then we will not evenneed to consider their claims of torture andpersecution by the Indonesian authorities.This will be convenient for Australia'sdiplomatic links with Indonesia, but atragedy for these people.There are also historical links betweenAustralians and East Timorese. During theSecond World War, East Timorese peoplevaliantly hid Australian service personnelfrom the Japanese. Many Timorese diedrather than give up the Australian soldiers.1~15 IS M'( SECOND t;.XIOCU·not-l-1HE: rll

0 NM"c" 25, 1997 the membm olthe Commonwealth Senate voted, 38 to 33,to confirm the resolution of their colleaguesin the House of Representatives that thePrivate Member's Euthanasia Bill shouldbecome law.The Bill, introduced into the LowerHouse six months previously by Liberalback-bencher Kevin Andrews, had been approvedby 88 votes to 35 in the House ofRepresentatives.The effect of the Senate vote was tooverturn the Northern Territoryvoluntary euthanasia legislation, TheRights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995,which had been approved with a narrowmajority by the Territory's parliamentarianson May 25th, 1995.The debate which attended the passingof the Andrews' Bill, in both theLower and Upper Houses was complicatedby the following factors:• the support given to the Bill by boththe Prime Minister and the Leader ofthe Opposition;• the whole question of States' andTerritories' rights,• the inadequacies of the NorthernT erritory legislative drafting;• the wider implications that the TerritoryAct might have for the continuingaccess of the Aboriginal community tohealth care;•the distinction between private moralityand public legislation;• the posturings of some of the proponentson both sides.T he way in which variou s responseswere represented in the media confused theissue even further. But those who listenedto the parliamentary hearings and thediscussion in both Houses were on thew hole impressed by the qu ality of thedebate. The manner of our dying, especiallyin this age of m edico-scientific technology,is obviously a matter that concerns usgreatly. The fact that there were over 12,000submissions to the Senate Committee isabundant evidence of this.At the height of the debate on February17th, 1997, three of the m ost outspokensupporters of the N orthern Territory legislationand of active voluntary euthanasiapublished a research study on 'End-of-lifeETHICSW.J. U RENLife and death mattersDecisions in Australian Medical Practice'in the Medical Journal of Australia. T heywere Dr Helga Kuhse and Professor PeterSinger, from the Monash University Centreof Human Bioethics, and Professor PeterBaume, from the School of Community Medicineat the University of New South Wales.They based their study on the 24 itemsof a questionnaire which replicated onecirculated origina lly to medicalpractitioners in the Netherlands by theRemmelink Commission in 1990 and 1995.Questionnaires were mailed to 3000Australian doctors who might possibly beinvolved in m aking end-of-life m edicaldecisions. There were 1918 responses ( 64percent) of whom 1361 hadattendedanonacutedeath within the last 12 months. Thisfield was further narrowed 'by excludingdoctors who in respect of that death had nocontact with the patient until after thatdeath or where the death had been suddenand totally unexpected'. Of the remaining111 2 doctors, 800 doctors reported m akinga decision either intended to shorten life orforeseen as probably or certainly shorteninglife. The other 3 12 doctors did not makesuch a decision .In analysing the responses from these1112 doctors the authors of the researchdrew as a 'main finding' that 30 per cent(±3.3 per cent) of all Australian deaths werepreceded by a m edical decision explicitlyintended to hasten the patient's dea th:doctors prescribed, supplied or administereddrugs with the explicit intention ofending the patient's li fe in 5.3 per cent(±lper cent) of these deaths, and withdrewor withheld life-prolonging treatment withthe explicit intention of not prolonging lifeor of hastening death in 24.7 per cent (±3 .1 percent) of these deaths.Further, 'in 22.5 per cent ('3. 1per cent)of all Australian deaths, doctors withheldor withdrew treatment from patients withoutthe patient's explicit request, with theexplicit intention of ending life' (M[A,17 February 1997, p195) . TheseAustralian figures, it was furthermaintained, are in the range of 50per cent higher than the figures forcorresponding categories"""J"'"' in the Netherlands..1. HE CONCLUSION DRAWN by the authorsof the study from their analysis of thesurvey was that one of the reasons whysome Australian doctors may be choosingintentionally to end the li ves of theirpatients without consulting the patientsthemselves, was that existing Australianlaws prohibiting euthanasia maymake doctors 'reluctant to discussm edical end-of-life decisions with theirpatients lest these decisions be construedas collaboration in euthanasia or in theintentional termination of life'.The authors are then, in effect, arguingfor a relaxation of the existing laws topermit active voluntary euthanasia. This,they say, will ensure that patients would beconsulted by their doctors, where possible(i.e. if they are competen t) both before lifeprolongingtreatment is withdrawn or withheldwith a lethal intention, and beforeanalgesic drugs were administered in suchquantities that the hastening of death wasnot only intended but virtually inevitable.This line of argument may well seem tobe more than a little paradoxical. One isinclined to subsume: if this is what ishappening when there is no legislationcondoning active voluntary euthanasia, willnot the practice of all forms of euthanasiabecome even more prevalent if it is legalised?The authors of the study argue to thecontrary. Not only will such legislation,they say, promote the autonom y of those18 EUREKA STREET • MAY 1997

patients who spontaneously and explicitlyrequest euthanasia (active voluntaryeuthanasia), but it will also reduce the incidenceof non-voluntary and involuntaryeuthanasia, that is, euthanasia without, oragainst, the explicit wishes of the patient.For doctors will then not fear to bring up thesubject of euthanasia with their patients,the authors claim, and so patients will beconsulted rather than bypassed when thesedeath-dealing decisions are taken . Nonvoluntaryand involuntary euthanasia willthus either be eliminated or become voluntaryand full autonomy will be maintained.Which of these two arguments houldwe accept?If we look to the study, we find thatthere were 234 doctors who decided not totrea t their patients either by withholding orby withdrawing treatment and in each casewith the explicit intention of hasteningdeath. When asked in item 15 of the questionnaire,'Why was the (possible) hasteningof the end of the patient's life by the lastm entioned act or omission not discussedwith the patient?', two replied that thepatient was too young, 55 said that thepatient was unconscious, and 28 said thatthe patient was demented, mentally handicapped,or suffering from a psychiatric disorders(i.e. 85 or 36 per cent were in effectnon-competent). In29 of the remaining 149cases the doctors replied that 'the actionwas clearly the best for the patient or thediscussion would have done more harmthan good'. Even more significantly, in 109cases (47 per cent) the doctors 'didnot answer the question'.HOW FROM THESE FIGURES did the authorsof the study conclude that, if euthanasiahad been legal, the doctors who did not as amatter of fact discuss their lethal intentionswith their patients, would then havediscus ed the matter with their patients?It is, to say the least, a very moot point.It seems to assume that the 47 per cent whodid not provide an answer to the foregoingquestion were unwilling to disclose to theMonash Cen tre for Human Bioethics, aknown supporter of the active voluntaryeuthanasia legislation, the real reason fornot discussing with their patients theirlethal intentions in withdrawing or withholdingtreatment, and that the real reasonwas th e fear of th eir decision beingconstrued as 'collaboration in euthanasiaor in the in tentional termination of life.'T his seem s very coy on the part of thesedoctors, and especially so when apparentlythey had no hesitation in admitting quiteopenly to the explicit intention to hastendeath. This coyness can only cast gravedoubts on the conclusion drawn by theauthors from the survey.Nor is the conclusion any more cogentlyvalidated when the survey addresses thecohort of 99 doctors who admitted toadministering large doses of opioids with atleast a partial intention of hastening death.In 22 of these cases the doctors reportedthat the patient was non-competent (young/unconscious/demented). In 20 cases theaction was said (by the doctor) to be clearlythe best for the patient, or discussion wouldhave done more harm than good. But onceagain the 'did not answer the question'cohort constitutes about half the responses(51 :52 per cent). If euthanasia had beenlegal, the authors conclude, then these doctorswho did not, as a matter of fact, discusstheir intentions withtheir patients wouldthen have discussed their intentions withtheir patients. How they feel authorised toconclude this is a mysteryWhat the survey does show, however,(and I leave to one side here the criticismsthat have been made of both the originalRemmelin k and more recent Monash questionnairethat they conflate 'intending tokill' with 'foresight of death' and 'hasteningdeath' with 'not prolonging life') is thatactive voluntary euthanasia and physicianassisted suicide (that is with the explicitrequest from the patient) in Australia as inthe Netherlands, is accompanied by at leasteight times the incidence of non-voluntaryor involuntary euthanasia.Perhaps, this is because we do not have alaw clearly legalising active voluntaryeuthanasia to the exclusion of all other fom1s.Perhaps, the reason why the incidenceof non-voluntary and involuntaryeuthanasia in the Netherlands is significantlyless than it is in Australia is becausethey do have some form of legal condonationwhile we have none.Bu t the survey, at least as published in theMedical fomnal of Australia, does not supportthe authors' stated conclusion that if euthanasiawere legalised in its active voluntaryfonn, the incidence of non-voluntary andinvoluntary euthanasia would be reduced.All the figures seem to show is thatgranting autonomy to some in activevoluntary euthanasia is accompanied by alarge denial of autonomy to others in nonvoluntaryand involuntary euthanasia. •W.J. Uren SJ is a bioethicist and lectures inm oral philosophy at the United Faculty ofTheology, Melbourne.AUGUSTINIANSSharing life and ministry togetherin .friendship and in communityas religious brothers and priests.'You and I are nothing but the Church ... Itis by love that we belong to the Church.'St AugustinePlease send me information aboutthe Order of St AugustineNAME ........................................................... .AGE ........... PHO E ................................. ...ADDRESS ..................................................... ..................................... P/CODE .................. .The Augustinians Tel: (02) 9938 3782PO Box 679 Brookvale 2100 Fax: (02) 9905 7864V oLUME 7 NuMBER 4 • EUREKA STREET 19