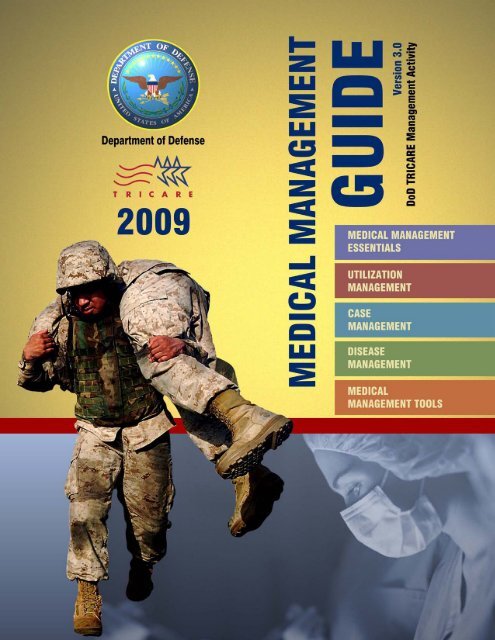

Medical Management Guide, 2009, Version 3.0 - Tricare

Medical Management Guide, 2009, Version 3.0 - Tricare

Medical Management Guide, 2009, Version 3.0 - Tricare

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Instructions:When accessing this <strong>Guide</strong> from the CD-ROM:1. Links to outside websites and CD-ROM Resources will open inthe same browser window as this <strong>Guide</strong>. When accessing theselinks, use your browser’s “Back” button to return to this <strong>Guide</strong>.2. The CD-ROM Resources are saved as browser-viewable AdobeAcrobat PDF files and other native file formats from programs suchas Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint, etc. These programs must beinstalled on your computer for access.A note about hyperlinks to outside websites: Links to outside websites found printedhere are provided only as a convenience to assist you in locating information that may behelpful. You should note that changes may occur since the printing of this <strong>Guide</strong> which mayaffect the accuracy or availability of the referenced link.All contents © <strong>2009</strong> DoD/Office of the Chief <strong>Medical</strong> Officer (OCMO)/TRICARE <strong>Management</strong>Activity (TMA) and the various other organizations whose work is reproduced here.

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong> Executive SummaryPage iiiExecutive SummaryINTRODUCTIONThe Department of Defense (DoD) TRICARE<strong>Management</strong> Activity (TMA) values all staffinvolved in the delivery of high-quality healthcare to DoD beneficiaries — Service members andtheir families. TMA is constantly working to providethe most current information to its partners in thiseffort.The <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> is issued by theOffice of the Assistant Secretary of Defense forHealth Affairs (ASD [HA]) and TMA, Office of theChief <strong>Medical</strong> Officer (OCMO), Population Healthand <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Division (PHMMD).The <strong>Guide</strong> covers the components of a <strong>Medical</strong><strong>Management</strong> (MM) program, including applicableprinciples, implementation concepts, processes, andtools/databases for Utilization <strong>Management</strong> (UM),Case <strong>Management</strong> (CM), and Disease <strong>Management</strong>(DM). It complements the 2001 DoD PopulationHealth Improvement Plan and <strong>Guide</strong> published byTMA and the Government Printing Office (http://www.tricare.mil/ocmo/download/mhs_phi_guide.pdf, and CD-ROM Resource ES-1).The ASD (HA) annually signs a five-year performanceplan for the Defense Health Program (DHP) with theSecretary of Defense, along with Army, Navy, andAir Force Assistant Secretaries for Manpower andReserve Affairs. MM-related measures (i.e., metrics)highlighted in the FY <strong>2009</strong> DHP Plan ( CD-ROMResource ES-2) include:• Beneficiary satisfaction with the health plan.• Inpatient production target (relative weightedproducts [RWP]).• Outpatient production target (relative valueunits [RVUs]).• Primary care productivity (RVUs per primary careprovider per day).• <strong>Medical</strong> cost per member per year.LEGISLATIVE GUIDANCEUnder legislative mandates, the ASD (HA)submits an annual report to Congressregarding healthcare delivery for 9.4 millionMilitary Health System (MHS) beneficiaries. The<strong>2009</strong> report documents the MHS goal of providinghigh-quality care, improving performance throughclinical and process outcomes, and increasingpatients’ confidence in the care they receive.<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong> of the <strong>Guide</strong> draws more specificallyfrom the Report to Congress on the ComprehensivePolicy Improvements to the Care, <strong>Management</strong> and

Page viExecutive Summary<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>CONTACT INFORMATIONAssistant Secretary of Defense, Health Affairs/TRICARE <strong>Management</strong> ActivityOffice of the Chief <strong>Medical</strong> OfficerPopulation Health and <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>Division5111 Leesburg PikeSuite 810Falls Church, VA 22041COMM: (703) 681-0064DSN 761-0064FAX: (703) 681-1242CD-ROM RESOURCESES-1 DoD TMA Population Health ImprovementPlan and <strong>Guide</strong> (2001)ES-2 DoD Defense Health Plan (DHP) <strong>2009</strong>HighlightsES-3 Report to Congress on the ComprehensivePolicy Improvements to the Care,<strong>Management</strong> and Transition of RecoveringService Members (Sept. 16, 2008)ES-4 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA)of 2008, Title XVI, Sections 1611 and 1615ES-5 An Achievable Vision: Report of theDepartment of Defense Task Force onMental Health (2007)ES-6 Rebuilding the Trust: The IndependentReview Group (IRG) on Rehabilitative Careand Administrative Processes at Walter ReedArmy <strong>Medical</strong> Center and National Naval<strong>Medical</strong> Center (2007)ES-7 The Secretary of Veterans Affairs Task Forceon Returning Global War on Terror Heroes(2007)ES-8ES-9ES-10ES-11ES-12Serve, Support, Simplify: The President’sCommission on Care for America’sReturning Wounded Warriors (2007)Veteran’s Disability Benefits Commission,Honoring the Call to Duty: Veterans’Disability Benefits in the 21st Century (2007)The President’s Task Force to Improve HealthCare Delivery for Our Nation's Veterans(2003)The Report of the CongressionalCommission on Service Members andVeterans Transition Assistance (1999)The President’s Commission on Veterans’Pensions (1956)‘

Page viiiAcknowledgements<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Air ForceCarol Andrews, Lt Col, NCDeona J. Eickhoff, Lt Col, NCSabrina M. Preston-Leacock, Lt Col, NCMelanie A. Prince, Lt Col, NCBrij B. Sandill, Lt Col, NCTammy R. Tenace, Lt Col, NCIwona E. Blackledge, Maj, NCShawn Dunne, Maj, NCKaryn L. Revelle, Maj, NCPaula M. Winters, Maj, NCSherry A. Herrera, MSN, NE-BC, CPUM, CMACBeverly K. Luce, MHSA, BSN, RN, CCMU. S. Department of Veterans AffairsKaren M. Ott, RN, MSNMilitary Patient Centered <strong>Medical</strong>Home ModelThis model was used with permission from andwas created by the National Naval <strong>Medical</strong> CenterPatient Centered <strong>Medical</strong> Home and by CDR KevinDorrance, USN, MC.Cover PhotoSource: http://www.defenseimagery.mil/Photographer: MSgt Steve Cline‘IndustryTerry Kelley, BSN, RN, CCM — Case <strong>Management</strong>Society of AmericaContractor SupportTechnology, Automation and <strong>Management</strong>(TeAM), Inc.• Charles G. Davis, CEO, Program Manager• Anne F. Cook, Technical Writer/Editor• Keira R. Thrasher, Senior Curriculum Developer• Syreeta M. Collier, Logistics Coordinator• Valerie Thompson, Graphic Designer

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong>Page ixTable Of ContentsClick text listing to viewExecutive Summary..................................................................................................................................... iiiIntroduction............................................................................................................................................................ iiiLegislative Guidance................................................................................................................................................ iiiDescription of <strong>Guide</strong> Contents................................................................................................................................ ivContact Information................................................................................................................................................ viCD-ROM Resources................................................................................................................................................. viAcknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... viiSection I – <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials.......................................................................................... 1Introduction............................................................................................................................................................ 1Definition of <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>.................................................................................................................. 1Primary Care <strong>Management</strong> Team Approach...................................................................................................... 2Policy Requirements for <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> within the Direct Care System................................................... 4<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Goals and Approach...................................................................................................... 5The Link between <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> and Population Health.............................................................................. 7Population Health Elements in Action............................................................................................................... 8TRICARE and Other Benefit Programs..................................................................................................................... 10Working with Managed Care Support Contractors........................................................................................... 10The Link between Clinical and Business Operations................................................................................................. 11Integrating Utilization, Case, and Disease <strong>Management</strong> Functions........................................................................... 12Staffing for Combined Functions...................................................................................................................... 16Essential Considerations for <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Staff.......................................................................................... 18Benefitting from Information Technology.......................................................................................................... 18Privacy and Confidentiality of Patient Information............................................................................................. 19Program Sustainment.............................................................................................................................................. 20Summary................................................................................................................................................................ 21CD-ROM Resources................................................................................................................................................. 21

Page <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Section II – Utilization <strong>Management</strong>...................................................................................................... 25Introduction............................................................................................................................................................ 25Definition, Goals, and Purpose.......................................................................................................................... 26Utilization <strong>Management</strong> Components .................................................................................................................. 26The Seven-Step Quality Improvement Process................................................................................................... 27Identify the Purpose................................................................................................................................... 28Determine What to Measure...................................................................................................................... 28Determine the Gaps................................................................................................................................... 29Attempt to Fix the Problem(s)..................................................................................................................... 29Determine the Effectiveness of the Corrective Action................................................................................. 30Make Additional Attempts to Fix the Problem(s)......................................................................................... 30Learn from the Quality Improvement Process.............................................................................................. 30Utilization Review............................................................................................................................................. 31Types of Review......................................................................................................................................... 32Outcome Measurement and <strong>Management</strong>........................................................................................................ 33McKesson ® InterQual ® ............................................................................................................................... 33Milliman Care <strong>Guide</strong>lines ® .......................................................................................................................... 36Provider Profiling.............................................................................................................................................. 36Referral <strong>Management</strong>....................................................................................................................................... 37Referral <strong>Management</strong> Center..................................................................................................................... 38Active Duty Service Member Referrals........................................................................................................ 39Authorization............................................................................................................................................. 40Episode of Care.......................................................................................................................................... 40The Electronic Referral Process................................................................................................................... 41Utilizing Military Treatment Facility Capability and Right of First Refusal Reports......................................... 43Additional Information............................................................................................................................... 43The Grievance and Appeal Process.................................................................................................................... 44Overview................................................................................................................................................... 44Grievances................................................................................................................................................. 45Appeals..................................................................................................................................................... 46Risk <strong>Management</strong>............................................................................................................................................. 51Utilization <strong>Management</strong> Program Accreditation....................................................................................................... 52The Utilization <strong>Management</strong> Professional................................................................................................................ 52Qualifications................................................................................................................................................... 52Staffing to Support Utilization <strong>Management</strong>..................................................................................................... 53Summary................................................................................................................................................................ 53CD-ROM Resources........................................................................................................................................... 54

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong>Page xiSection III – Case <strong>Management</strong>............................................................................................................ 57Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 57Definition, Goals, and Purpose.......................................................................................................................... 58Philosophy ....................................................................................................................................................... 60The Military Case Manager............................................................................................................................... 60Case <strong>Management</strong> Components ........................................................................................................................... 62Beneficiary Identification/Case Finding.............................................................................................................. 62Triggers for Potential Referral..................................................................................................................... 63Case Screening................................................................................................................................................. 64Case Selection.................................................................................................................................................. 64The Six-Step Case <strong>Management</strong> Process............................................................................................................ 65Assessment................................................................................................................................................ 66Planning..................................................................................................................................................... 66Implementation.......................................................................................................................................... 68Coordination.............................................................................................................................................. 69Monitoring................................................................................................................................................. 69Evaluation.................................................................................................................................................. 70Case Closure.................................................................................................................................................... 70Documentation................................................................................................................................................ 71Outcome Measurement and <strong>Management</strong>........................................................................................................ 71Patient Outcome Evaluation....................................................................................................................... 73Program Outcome Evaluation..................................................................................................................... 73Establishing a Case <strong>Management</strong> Program........................................................................................................... 78Organizational Framework................................................................................................................................ 78Goals................................................................................................................................................................ 78Implementation................................................................................................................................................ 79Quality....................................................................................................................................................... 79Caseload.................................................................................................................................................... 80Discharge Planning..................................................................................................................................... 81Care Coordination...................................................................................................................................... 83Accreditation.................................................................................................................................................... 83Promoting Your Program.................................................................................................................................. 83Legislative Guidance Specific to Integrating Physical and Psychological Rehabilitation........................................... 83Disability Evaluation System.............................................................................................................................. 85<strong>Medical</strong> Evaluation Board........................................................................................................................... 85Physical Evaluation Board........................................................................................................................... 85Other Types of Evaluation ....................................................................................................................................... 86

Page xii<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Recovery Coordination Initiatives............................................................................................................................. 87Federal Recovery Coordination Program............................................................................................................ 87Recovery Care Coordinators....................................................................................................................... 87Transition/Coordination of Care............................................................................................................................... 88Transition of Care............................................................................................................................................. 88Service-Specific Care Transition Programs................................................................................................... 89Inter/Intra-Regional Transfer....................................................................................................................... 89Aeromedical Evacuation............................................................................................................................. 90Coordination of Care........................................................................................................................................ 92Coordination from the Military Health System to the Department of Veterans Affairs................................. 92Coordination for Active Duty Service Members in the TRICARE Prime Remote Program.............................. 92Coordination for Exceptional Family Member Program and Special Needs Families...................................... 93Transition/Coordination Challenges................................................................................................................... 95Other Types of Transition/Coordination............................................................................................................. 95Outside the Continental United States and TRICARE Global Remote Overseas Program.............................. 96The Case <strong>Management</strong> Professional........................................................................................................................ 97Qualifications................................................................................................................................................... 97Education and Experience Requirements.................................................................................................... 97Certification............................................................................................................................................... 98Ethical Practice Standards........................................................................................................................... 98Resources for Orienting and Training the New Case Manager........................................................................... 99Summary................................................................................................................................................................ 100CD-ROM Resources................................................................................................................................................. 100Section IV – Disease <strong>Management</strong>.......................................................................................................... 105Introduction............................................................................................................................................................ 105Definition, Goals, and Purpose.......................................................................................................................... 106The Current State of Disease <strong>Management</strong>....................................................................................................... 107Managing Chronic Disease in the Military Health System............................................................................ 107Employer-Funded Health Plans................................................................................................................... 108Cost Savings for Disease <strong>Management</strong>....................................................................................................... 108Disease <strong>Management</strong> Components........................................................................................................................ 109Population Identification Processes................................................................................................................... 109Evidence-Based Clinical Practice <strong>Guide</strong>lines....................................................................................................... 110Fundamentals............................................................................................................................................ 110Department of Defense/Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice <strong>Guide</strong>lines................................... 112National <strong>Guide</strong>line Clearinghouse........................................................................................................... 114

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong>Page xiiiU.S. Preventive Services Task Force............................................................................................................. 114Collaborative Practice Models........................................................................................................................... 115Patient Self-<strong>Management</strong> Education................................................................................................................. 116Process and Outcome Measurement, Evaluation, and <strong>Management</strong>.................................................................. 118Clinical Quality Measures........................................................................................................................... 119Feedback and Reporting................................................................................................................................... 123Stakeholder Reporting................................................................................................................................ 123Establishing a Disease <strong>Management</strong> Program....................................................................................................... 124Implementing a Disease <strong>Management</strong> Plan....................................................................................................... 124Assess the Target Population...................................................................................................................... 125Assemble a Team....................................................................................................................................... 125Adopt <strong>Guide</strong>lines and Protocols................................................................................................................. 126Establish Goals and Target Outcomes......................................................................................................... 126Create a Prioritized Plan and Implement the Plan........................................................................................ 127Collect and Analyze Outcomes Data........................................................................................................... 127Evaluate and Refine the Program................................................................................................................ 127Accreditation............................................................................................................................................. 127The Disease <strong>Management</strong> Professional................................................................................................................. 128Qualifications................................................................................................................................................... 128Certification..................................................................................................................................................... 129Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 129CD-ROM Resources.............................................................................................................................................. 130Section V – <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Tools............................................................................................ 133Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 133Using Information Systems and Data Marts ......................................................................................................... 133Accessing the Data........................................................................................................................................... 133Understanding the Methodology and Limitations............................................................................................. 134Data Quality Concerns...................................................................................................................................... 134Information Systems And Data Marts ................................................................................................................ 134Military Health System-Level Decision Support Tools and Executive Information Systems................................ 134Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application............................................................................... 134Executive Information and Decision Support..................................................................................................... 134Tools for Utilization, Case, and Disease <strong>Management</strong> Collaboration...................................................................... 135TRICARE <strong>Management</strong> Activity Reporting Tools .............................................................................................. 136Health Assessment Review Tool........................................................................................................................ 139MHS Insight...................................................................................................................................................... 140

Page xiv<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Prospective Payment System............................................................................................................................. 140Protected Health Information <strong>Management</strong> Tool............................................................................................... 140Service-Level Information Systems........................................................................................................................... 140Army................................................................................................................................................................ 140Navy................................................................................................................................................................. 141Air Force........................................................................................................................................................... 141Business Planning Tools........................................................................................................................................... 141Tri-Service Business Plans.................................................................................................................................. 141CD-ROM Resources................................................................................................................................................. 144Appendix A – References.......................................................................................................................... 147Appendix B – Acronyms............................................................................................................................. 156Appendix C – Definitions........................................................................................................................... 161Appendix D – Resources............................................................................................................................ 185

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong>Page xvTable Of FiguresClick text listing to viewSection I – <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsFig. 1 – Military <strong>Medical</strong> Home Model................................................................................................................. 3Fig. 2 – MHS <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Model.......................................................................................................... 3Fig. 3 – MHS Population Health Model (2006)..................................................................................................... 7Fig. 4 – Integrated <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Model (IM3)......................................................................................... 14Fig. 5 – Distinctions between UM, CM, and DM.................................................................................................. 15Fig. 6 – Questions to Consider when Creating an Integrated MM Program........................................................... 17Section II – Utilization <strong>Management</strong>Fig. 7 – Utilization <strong>Management</strong> within the MHS Integrated MM Model (IM3)..................................................... 25Fig. 8 – Seven-Step Quality Improvement Process................................................................................................. 27Fig. 9 – Sample UM Data Elements or Measures.................................................................................................. 34Fig. 9 (cont.) – Sample UM Data Elements or Measures ....................................................................................... 35Fig. 10 – TRICARE Referrals/Preauthorizations/Authorizations............................................................................... 42Fig. 11 – MTF Review and Appeal Process: Internal Review................................................................................... 47Fig. 11 (cont.) – MTF Review and Appeal Process: Internal Review/Appeal............................................................ 48Fig. 11 (cont.) – MTF Review and Appeal Process: External Appeal....................................................................... 49Section III – Case <strong>Management</strong>Fig. 12 – Case <strong>Management</strong> within the Integrated MM Model (IM3).................................................................... 57Fig. 13 – Chronic Care <strong>Management</strong> Model......................................................................................................... 59Fig. 14 – Military-Specific Designations, Programs, and Offices............................................................................. 61Fig. 15 – Potential Sources for Case Finding......................................................................................................... 62Fig. 16 – The Six-Step CM Process........................................................................................................................ 65Fig. 17 – Categories of Assessment...................................................................................................................... 67

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsSECTIONIINTRODUCTIONDefinition of <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>In the healthcare industry, organizations haveestablished programs or systems to improveclinical outcomes and manage rising healthcarecosts. This is broadly referred to as the field of“<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>” (MM).The 2006 Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI)6025.20, <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> (MM) Programs inthe Direct Care System (DCS) and Remote Areas( CD-ROM Resource MME-1, and http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/pdf/602520p.pdf)defines MM as an “integrated managed care modelthat promotes Utilization <strong>Management</strong> (UM), Case<strong>Management</strong> (CM), and Disease <strong>Management</strong> (DM)programs as a hybrid approach to managing patientcare.” MM includes a shift to evidence-based,outcome-oriented programs that place “a greateremphasis on integrating clinical practice guidelinesinto the MM process, thereby holding the systemaccountable for patient outcomes” (DoDI 6025.20).This guide provides specific, how-to guidance onestablishing MM programs within Military TreatmentFacilities (MTFs) in accordance with the DoDinstruction.The three components of MM are commonlydefined as follows:• Utilization <strong>Management</strong>: An organization-wide,interdisciplinary approach to balancing cost,quality, and risk concerns in the provision ofpatient care. UM is an expansion of traditionalUtilization Review (UR) activities to encompassthe management of all available healthcareresources, including Referral <strong>Management</strong> (RM).• Case <strong>Management</strong>: A collaborative processunder the Population Health continuum thatassesses, plans, implements, coordinates,monitors, and evaluates options and servicesto meet an individual’s health needs throughcommunication and available resources topromote quality, cost-effective outcomes.• Disease <strong>Management</strong>: An organized effort toachieve desired health outcomes in populationswith prevalent, often chronic diseases forwhich care practices may be subject toconsiderable variation. DM programs useevidence-based interventions to direct patientcare. DM programs also equip the patient withinformation and a self-care plan to managehis/her own health and prevent complicationsthat may result from poor control of the diseaseprocess. The term “condition management”includes non-disease states (e.g., pregnancy).See also Appendix C, Definitions.

Page <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Both patients and MTF leadership have been drivingforces for more efficient, effective, and integratedMM programs in the following ways:• In today’s healthcare arena, patients are moreinformed and empowered consumers. Asa result, they demand more choice in theirhealthcare benefits than ever before.• MTF leadership strives to control risinghealthcare costs, demonstrate return oninvestment (ROI), and ensure that patients areprovided with safe, quality care. MTF leadershipis key to providing the organizational structure,appropriate resources, and necessary expertiseto ensure the success of any MM program.Primary Care <strong>Management</strong> Team Approachand continuity of care as well as serving as the pointof first contact when problems or questions arise.MM is an integral part of the PCM model and PCMHteam approach to patient care. Case managers assistthe PCM team in coordinating, communicating,and integrating care. Disease managers assist theteam in consistently implementing evidenced-based,clinical-based guidelines. Utilization managers assistthe team in the optimal allocation of scarce medicalresources within the medical home.The successful application of MM activities withinMTFs is geared toward achieving the primary targetgoals of improving access and quality, managingcost, and optimizing readiness.Primary care in the MHS revolves around the role ofthe Primary Care Manager (PCM) — this PCM modelis built on the documented value of patients, withconsistent access to comprehensive primary care,achieving better health outcomes, improved patientexperience, and more efficient use of resources. Inthis model, each patient has an ongoing relationshipwith a personal primary care provider trained toprovide continuous and comprehensive care.While the MHS primary care system is ultimatelysupervised and led by a PCM, the concept of a teamof healthcare professionals, under the leadershipof the credentialed provider team leader, is widelyaccepted and highly valued as a key component ofthe MHS culture. The PCM model in the MHS hasbeen expanded to include the concept of a Patient-Centered <strong>Medical</strong> Home (PCMH), as illustrated inFig. 1. In the PCMH, patients have a continuousrelationship with a medical home that offers stabilityIn addition to applying to the civilian-basedPurchased Care System (PCS), MM traverses theDirect Care System (DCS), which encompasses Army,Air Force, and Navy facilities in the North, South,and West regions of the United States; and overseasin the designated region Outside of the ContinentalUnited States (OCONUS). MTF staff work closelywith their Contracting Officer’s Representative/Contracting Officer’s Technical Representative (COR/COTR) to help ensure that MTF activities are closelycoordinated to meet patient needs. Fig. 2 depicts theMHS MM model.

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage CONTINUOUS RELATIONSHIPPATIENT-CENTERED CAREAccess to Care• Improve phone and electronic apptscheduling• Open access for acute care• Emphasis on coordination of care• Proactive appointing for chronic andpreventive careAdvanced IT Systems• Secure mode of e-communication• Creation of educational portal• Reminders for preventive care• Easy, efficient tracking of populationdataDecision Support Tools• Evidence-Based Training• Integrated Clinical <strong>Guide</strong>lines• Decision Support Tools at the point ofcareTeam-BasedHealthcare Delivery• Creation of Clinical Micropractices• Appropriate utilization of medicalpersonnel• Improve communication among teammembersMilitary<strong>Medical</strong>HomePatient & PhysicianFeedback• Real-time data• Performance reporting• Patient feedback• Partnership between patients and careteams to improve care deliveryPopulationHealth• Emphasis on preventive care• Form basis of productivity measures• Evidence-based medicine at the pointof carePatient-Centered Care• Empower active patient participation• Seamless communications• Encourage patient participation inprocess improvementRefocused <strong>Medical</strong>Training• Emphasize health team leadership• Incorporate patient-centered care• Focus on quality indicators• Evidence-based practiceWHOLE PERSON ORIENTATIONPERSONAL PHYSICIANSFig. 1 – Military Patient Centered <strong>Medical</strong> Home ModelMilitary Health Services<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> ModelFig. 2 – MHS <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Model

Page <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Policy Requirements for <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>within the Direct Care SystemDoDI 6025.20 defines terms for MM, implementspolicies, assigns responsibilities, and specifiescontent for component activities within the MTF.It also codifies support for an interdependent MMsystem between the DCS and Purchased CareSystem (PCS). The instruction outlines the followingminimal requirements:<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> (General)• Designate one individual to be responsible forthe facility’s MM program.• Establish an integrated MM plan and programusing the quality improvement approach.Utilization <strong>Management</strong>• Use systematic, data-driven processes to a)proactively define referral patterns for focusedinterventions and b) identify and improve clinicaland business outcomes.• Incorporate UR activities using the same generallyaccepted standards and criteria for medicalnecessity, appropriateness, and reasonablenesswhen reviewing the quality, completeness, andadequacy of health care provided within theMTF.• Adhere to the established MTF review andappeal process.• Establish a referral and authorization managementprocess for internal and external referralsin accordance with MHS policies.• Establish a solid relationship with the ManagedCare Support Contractor (MCSC) — seeTRICARE and Other Benefit Programs,Working with Managed Care SupportContractors, later in this section.• Establish processes to monitor, manage, andoptimize access to care within the MTF (e.g.,to meet demand and access standards bymaximizing use of template management tools).• Encourage collaboration and communicationamong all MM staff, including clinical and businesspersonnel, to promote efficient, effective,and high-quality care and services.Case <strong>Management</strong>• Use CM to manage the health care of patientswith multiple, complex, chronic, and/orcatastrophic illnesses or known conditions thatmeet CM criteria.• Provide the appropriate level of care (e.g., carecoordination, discharge planning) for individualsrequiring special assistance (e.g., woundedwarriors).• Coordinate the transfer of information withMCSC CMs when patients require CM outsidethe DCS.• Encourage case managers to communicate withall members of the healthcare team, especiallywith other MM personnel.• Use CM to promote a seamless transition fromone duty station to the next for families enrolledin the Exceptional Family Member Program(EFMP) and Special Needs Identification andAssignment Coordination (SNIAC) programs,and who are also enrolled in a CM program.Disease <strong>Management</strong>• Assess the population to determine theneed for specific DM programs by evaluatingMTF Population Health data through variousinformation systems.

Page <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>The MM approach in the health industry hasevolved rapidly in recent years. This evolution can beattributed to several factors, including:• The desire to increase the effectiveness ofpatient-provider relationships and improveclinical outcomes.• Greater demand to contain costs and improvereturn on investment (ROI) (i.e., to demonstratevalue).• The need to improve technology andcommunication to facilitate data collection,analysis, and information sharing (UtilizationReview Accreditation Commission [URAC],2005).• The need to fulfill regulatory and legislativemandates per the Code of Federal Regulations(CFR).MM policy and programs built from high-qualitydata collection, proper analysis, interpretation,dissemination, and outcome measurement ensurebetter clinical outcomes and improved quality ofcare for MHS beneficiaries. Cohen and Cesta (2001)cite three major types of outcome that are measuredin healthcare systems:• High-quality care – Measured by complications,readmission rates, morbidity and mortality, andpatient satisfaction. These quality measures(i.e., metrics) reflect greater accountability onthe part of healthcare providers to patients andother stakeholders.• Decreased or appropriate costs – Includemeasures such as length of hospital admission,avoidable admission days, decrease in EDvisits, and decrease in excessive utilizationof outpatient appointments. In military CM,appropriate costs are also measured by retainingcare in the DCS (i.e., MTFs) if the capability andcapacity exist. This outcome relates directly to aMTF’s business plan.• Improved health status — Often measuredthrough surveys that examine how a patientperceives the impact of health on quality of life.Other measures may include functional healthstatus, reduction or elimination of symptoms,resumption of employment, or improved copingmechanisms.It should be noted that many of the same resourcesused to calculate corporate outcome measures areavailable to MM teams at the MTF level. Further,healthcare teams should be apprised of and alignedwith other quality and outcome measure sets thatfall under the rubric of Quality <strong>Management</strong> (QM).One particular example is quality measures forperinatal care. MTF performance for obstetricalsurgery, complications, post-partum readmissions,and neonatal mortality rates is tracked using theNational Perinatal Information Center (NPIC) datasetfor comparison across both the MHS and civilianfacilities. Other sources for quality measures includethe National Surgical Quality Improvement Program(NSQIP) and the Anesthesia Report and MonitoringPanel (ARMP). Local QM representatives should beable to provide greater detail on which measuresand data sources are tracked at a specific MTF.(Section II, Utilization <strong>Management</strong>; SectionIII, Case <strong>Management</strong>; and Section IV, Disease<strong>Management</strong> each offer detailed discussions ofoutcome measurement.)

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage THE LINK BETWEEN MEDICALMANAGEMENT AND POPULATION HEALTHThe link between MM and Population Healthis an important one, with the trend in recentyears for organizations to incorporate totalPopulation Health techniques as part of their MMprograms. Four Population Health concepts specificto military medical care are:• Maintain a fit and healthy Active Dutypopulation (which affects readiness).• Improve the health status of the enrolledpopulation.• Improve the efficiency and effectiveness of theMTF healthcare delivery system.• Improve the military community populationhealth status.In order to incorporate Population Healthtechniques, MM and Population Health staff needto evaluate the current health practices of MTFenrollees and identify opportunities to improvethe health of that beneficiary population. The keyPopulation Health process elements listed belowrelate directly to MM:1. Population Identification and Assessment2. Demand Forecasting3. Demand <strong>Management</strong>4. Capacity <strong>Management</strong>5. Evidence-based Care and Prevention6. Program Evaluation and FeedbackFig. 3 illustrates the relationship between PopulationHealth elements and environmental influenceswithin the military community.Fig. 3 – MHS Population Health Model (2001)

Page <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Because many of the process steps are similar,Population Health and MM staff often collaborateon developing, reviewing, and meeting programgoals.For example:• UM activities focus on the four PopulationHealth principles of defining the population,applying epidemiological methods to describethe population and its risks, identifying andemploying evidence-based interventions, andmanaging information — all in the interest ofsupporting ongoing assessment, planning, andperformance monitoring/improvement.• Population-based CM coordinates care andservices for groups with similar characteristics.Case managers are responsible for “managinghealth, illness, prevention, and coordinationof care and services, including during acuteepisodes or hospitalization.” The casemanager’s role is to “develop and manage acomprehensive plan of care throughout thecontinuum in a way that takes advantage of allthe resources an integrated system has to offer”(Qudah, Brannon, 1998).• Population Health looks at the broaderpopulation in a larger context, while DM focuseson a particular segment of the population witha specific set of co-morbidities. DM activitiesare directly linked to population identification,evidence-based care and prevention, andprogram evaluation and feedback.Population Health Elements in ActionPopulation identification and assessment involvesstudying and understanding the population, whichmay consist entirely of beneficiaries within the MTFor represent a subset of that group. Regardless ofthe actual size of the population, you should be ableto identify sub-populations that may benefit fromspecific programs. Knowing your population allowsyou to extract information on age, gender, anddisease burden in the interest of planning healthcareservices that best meet beneficiary needs.Demand forecasting involves making an estimateof the volume of care required by a population orpopulation subset. This requires not only accuratedemographic and disease information, but alsopopulation-specific knowledge of healthcare needs,established clinical practice standards (chronicand preventive), and system- or Service-specificdemands (e.g., pre-deployment exams). Populationidentification and assessment activities allow MMstaff to anticipate, or “forecast,” the healthcareneeds of the relevant population or sub-population.Demand is typically measured by aspects suchas workload units by provider type, number ofspecific treatments, and pharmacy demand. Byunderstanding the demand forecast for an MTF,the healthcare team can determine staffing andbudgetary requirements and prioritize programs tosupport health promotion, prevention, and chroniccare services.Demand management involves proactiveintervention to reduce the rate of unnecessaryhealthcare resource utilization while encouraging

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong><strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage patients to use healthcare resources appropriately.Related activities include:• Evaluating primary care manager (PCM)assignments to address the right patient mix forthe provider role and to generate even patientdistribution among providers.• Optimizing the activities of all healthcare teammembers during patient visits.• Utilizing functions such as nurse triage, groupappointments, etc.• Promoting the enrollment of beneficiaries toproviders at the MTF when sufficient MTFresources are available.• Educating beneficiaries about primary caretriage systems and self-care programs (e.g.,advice lines, Web-based materials).Capacity management involves matching the needsof the population served (as identified duringdemand forecasting) with the quantity and qualityof services available at the MTF. Related activitiesinclude:• Implementing proactive strategies to meetforecasted demand.• Managing clinical processes.• Clarifying staff roles and responsibilities.• Controlling leakage to the network.To accomplish these endeavors, it is important tooptimize the supply of healthcare resources to alignwith beneficiary needs or demand. This may include:• Identifying actions that will reduce excesshealthcare demand.• Improving processes to increase system“throughput” (amount of work completedwithin a given period of time).• Using evidence-based practices to perform theright actions at the right time.In terms of patient demand, the Capacity<strong>Management</strong> element is affected by bothactual healthcare needs and military readinessrequirements. From the healthcare team perspective,it is affected by factors such as provider, supportstaff, and ancillary staff availability; physical space;equipment needs; and appointment processes.Evidence-based care and prevention involves using asystematically developed, research-based approachto health care. This approach increases the qualityof care delivered, reduces variation, and decreasescost. When evidence-based care is practiced,patients will typically experience an enhancedquality of life as a result of higher functional status,greater ability to self-manage, and less frequenthospitalizations. Evidence-based care is informedby research rather than provider consensus. It relieson an interdisciplinary team to manage care andprovide referral to health promotion and educationresources.Program evaluation and feedback rests on theassumption that Population Health programsand their respective outcomes (as with any otheraspect of health care) should be evaluated todetermine performance and progress. This elementincorporates a range of tools and programs to a)identify and address barriers to achieving desiredoutcomes, and b) make changes, as needed, toimprove healthcare delivery processes.

Page 10 <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>TRICARE AND OTHER BENEFIT PROGRAMSMTF Commanders are responsible for all healthcare provided or purchased within their catchment/market area. As such, they have direct control overappointment and referral services as well as overMM programs for their TRICARE Prime enrollees.The TRICARE healthcare program (http://tricare.mil) serves Active Duty Service members (ADSMs),National Guard and Reserve members, retirees,their families, survivors, and certain former spousesworldwide. TRICARE contracts augment MTFservices. Each MTF, Multi-Service Market Office(MSMO), and TRICARE Regional Office (TRO) mustwork with its regional contractor (see Workingwith Managed Care Support Contractors, laterin this section) to develop individual memoranda ofunderstanding (MOUs) that establish programs andactivities specific to that particular facility. Contractimplementation may vary based on how each facilityinterprets an MOU. For additional information onTRICARE, contact your local TRICARE Service Center(TSC) and/or Benefits Counseling and AssistanceCoordinator (BCAC).TRICARE offers special programs, including theExtended Care Health Option (ECHO), ContinuedHealth Care Benefits Program (CHCBP), andComputer/Electronic Accommodation Program(CAP). For more information, go to http://tricare.mil/mybenefit/home/overview/SpecialPrograms.Most beneficiaries will have TRICARE as theirprimary provider or payor. But MM staff, specificallyUM and CM personnel, also need to have a basicunderstanding of other programs beneficiaries maybe enrolled in, such as:• Medicare, Medicaid: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/• Supplemental Security Income (SSI):http://www.ssa.gov/ssi/• Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI):http://www.ssa.gov/disability/• U.S. Family Health Plan: http://www.usfhp.com/• U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA):http://www.va.gov/See Appendix C, Definitions; and Appendix D,Resources for more information.Working with Managed Care SupportContractorsThe United States are divided into three TRICAREregions. Each of the regions has a regionalcontractor that helps administer the TRICAREbenefit plan. This role is defined as the ManagedCare Support Contractor (MCSC). MCSCs provide avariety of functions, including:• Establishing TRICARE provider networks.• Operating TRICARE service centers.• Operating customer service call centers.• Providing administrative support, such asenrollment, care authorization, and claimsprocessing.• Communicating and distributing educationalinformation to beneficiaries and providers.MCSCs work with their TRO to manage the benefitat the local level, and receive overall guidance fromTMA headquarters (TRICARE Fact Sheets, TRICARERegional Contractors for the United States, 2006).(See also Appendix C, Definitions.)

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage 11The MHS necessitates close collaboration betweenMM staff located in the DCS, embodied by the MTF— an Active Duty setting; and the PCS, embodiedby the MCSC — in a civilian setting. Patientsbenefit when their healthcare services are smoothlycoordinated between the DCS and PCS. This “handoff,”or patient transition, is the act of transferringMM functions from one responsible entity toanother. Patients may frequently transition betweenthe MTF and the network, or between individualMTFs.By contract, the MCSC runs programs that managethe health care of individuals with high-costconditions or with specific diseases addressedby proven clinical management programs; thisresponsibility extends to providing MM servicesfor beneficiaries enrolled in ECHO. The MCSC alsoassumes responsibility for enrolled beneficiaries withcatastrophic, high-risk, high-cost situations whosecare occurs (or is projected to occur), in whole orin part, in the civilian sector. Program specificationsvary by region and are governed by specific MTFMOUs with the MCSC.THE LINK BETWEEN CLINICAL ANDBUSINESS OPERATIONSThe fundamental concepts in determiningappropriate MM measures within the MTFare a) integration with the Command’smeasures and b) alignment with the local MTF’sstrategic vision and business plan.Business planning “encompasses all strategic goalsand activities needed to ensure an organization’ssurvival and growth,” with the outcome of thebusiness planning cycle being “a consolidated MHSbusiness plan that serves as a primary input to theProspective Payment System (PPS).” In this regard,Tri-Service business plans provide “a commonframework across the MHS for improving andmeasuring performance” in the DCS (FY 2010-2012Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery [BUMED]Business Planning Supplemental Guidance,CD-ROM Resource MME-2).According to the DoD’s Defense Health Program(DHP) FY <strong>2009</strong> budget estimates, the DoD’s totalhealth costs more than doubled between 2001 and2006, from $19 billion to $38 billion — an increaserepresenting 8 percent of the DoD budget. Thisincrease was attributed to a combination of benefitenhancements, increased beneficiary use, stablecost shares, and high healthcare inflation. Thosecosts were projected through trend analysis to reach$64 billion, or 11.3 percent of the DoD budget, byFY 2015 (refer to CD-ROM Resource ES-2, DoDDefense Health Plan (DHP) <strong>2009</strong> Highlights).The business plan is the MTF’s roadmap for financialsuccess, but clinical operations, in collaborationwith Resource <strong>Management</strong> staff, are crucial indetermining that road map. It is therefore essentialfor clinical staff to actively engage in the businessplanning process. Their knowledge gives them theability to validate baseline historical data such asenrollment, outpatient/inpatient workload, and outpatient/inpatientutilization.The staff primarily involved in producing workload,documentation, and coding should be consultedwhen the MTF is determining a particulardepartment’s productivity targets or goals (e.g.,

Page 12 <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>number of relative value units [RVUs]). Clinicalprofessionals will also be involved in implementingsome of the critical initiatives identified within thebusiness plan, such as RM and evidence-basedhealth care (i.e., DM). (See also IntegratingUtilization, Case, and Disease <strong>Management</strong>Functions; Staffing for Combined Functions,later in this section.)Eight critical initiatives frame business planning inthe MTF:1. Improve Access to Care2. Improve Provider Productivity3. Manage Referrals4. Labor Reporting (performed through the<strong>Medical</strong> Expense & Performance ReportingSystem, or MEPRS: http://www.meprs.info/— see also Section V, <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong>Tools)5. Improve Documented Value of Care (Coding)6. Evidence-based Health Care7. Manage Pharmacy Expenses8. Expeditionary Planning (Readiness)To help MTF Commanders execute their localbusiness plans, the MHS has established MM as partof both its clinical and business operations. Businessplanning offers the opportunity for annual strategicmanagement by creating a defined relationshipbetween current performance and the criticalrequirements needed to reach market goals. Asa new resource allocation methodology, businessplanning forecasts healthcare needs within the DCSand PCS with budgets focused on outputs ratherthan inputs. MM measures are calculated at variouslevels within the MHS, with a number of sourcesthat centrally calculate and display measures fromService-level aggregate to provider-level detail.(See Section V, <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Tools,for information and resources related to Tri-Servicebusiness planning.)INTEGRATING UTILIZATION, CASE, ANDDISEASE MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONSIntegrating MM components not only improvesclinical outcomes; it improves organizationalefficiency and effectiveness. For example, whilemore CM and DM personnel are used to implementcomprehensive and integrated MM programs,staffing needs shift as fewer direct UM-relatedauthorizations are needed.Integrating UM, CM, and DM functions in the MTFfacilitates transitions of care and stewardship ofresources. The National Transitions of Care Coalition(http://www.ntocc.org/) advocates for and hasdeveloped tools to support transitioning patients.Historically, MTFs placed UM within their BusinessOperations or Resource <strong>Management</strong> department,while CM and DM were placed within the Nursingdepartment. This produced significant fragmentationof services, higher staffing requirements, andincreased costs. It also generated the view,particularly among providers, that the priority of UMstaff was to save money for the institution ratherthan to provide safe and quality health care topatients.Current trends focus on co-locating UM and CMresources to maximize and balance both clinicaland business outcomes. Fully integrating UM andCM staff has helped improve the overall quality of

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage 13care through a highly synergistic effect, with thefollowing results:• Significant decrease in the duplication of effortand redundancy.• Decrease in negative outcomes from improperor poor handoffs.• Improvement of overall workload management.• Improvement in the appropriate patient use ofbenefits.UM, CM, and DM have many similarities in termsof goals, concepts, and tasks. The key to successis establishing links of communication betweenprograms or departments. In this regard, it is helpfulto consider these three MM components within thecontext of a healthcare continuum as described inthe 2001 DoD Population Health Improvement Planand <strong>Guide</strong> (next iteration due to be published in2011). The <strong>Guide</strong> is available at http://www.tricare.mil/ocmo/download/mhs_phi_guide.pdf (see alsoExecutive Summary, CD-ROM ResourceES-1).Continuum is defined as an uninterrupted period,referring to the various stages of health andapplications of the CM process. It may be seenas running parallel to a "preventive model" thatmeasures cause and effect in MM interventions.This model comprises three phases, as describedin part by Wilson, Carneal, and Newman (2008)(see CD-ROM Resource MME-12 for fullarticle):• Primary prevention is about preventing theonset, or incidence, of disease (e.g., throughvaccinations).• Secondary prevention is about detection ofdisease.• Tertiary prevention is about the prevention offurther suffering among end-stage prevalentcases (e.g., through ameliorating pain andproviding psychosocial comfort).Based on this model, success (achievement ofoutcomes) can be understood in one of two ways:• Slowing, halting, or reversing advancementwithin the same phase.• Slowing, halting, or reversing transition to thenext phase.Fig. 4 illustrates how UM, CM, and DM functionsinteract within the MHS in the context of thePopulation Health continuum and in keeping withthe three levels of prevention.While the end goal is to integrate the componentsof MM, MTFs may first need to developtheir individual UM, CM, and DM programs. Fig. 5compares and contrasts each component.Some challenges may prevent successfulintegration. For example, each Service — from theheadquarters to the local MTF level — organizesits medical services and departments differently,using a variety of titles, terms, and personnelresources. Additionally, there continues to be alack of process standardization within the Servicesthemselves. Identification of poor clinical outcomesor other red flags (e.g., an inability to meet accessstandards, longer lengths of stay, or outliers ofany performance measure) may indicate system ororganizational issues rather than a clinical problem.

Page 14 <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Essentials<strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>Integrated <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Model (IM3)The Integrated <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> (MM) Model (IM3) is a pictorial representation of the clinical approach topatient management (i.e., MM) along the healthcare continuum. The components of the model are as follows:• The curved arc depicts how MM falls within the spectrum of Population Health. The clinical activities ofUtilization <strong>Management</strong> (UM), Case <strong>Management</strong> (CM), and Disease <strong>Management</strong> (DM) are geared towardachieving healthy populations.• The vertical arrows indicate the integration of Population Health and MM functions.• The large horizontal arrow depicts the healthcare continuum, illustrating the correlation between health, risk,disease, and impairment states and their alignment with primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention efforts. Apatient may move anywhere along the healthcare continuum.• The red bar represents UM activities and functions along the entire healthcare continuum. UM functionsinclude collecting and analyzing data that assist CM and DM in identifying populations or individuals who maybenefit from services.• The green triangle highlights DM activities and functions. DM typically intervenes on the left side of thehealthcare continuum with populations who benefit from DM, using primary and secondary preventionactivities.• The blue triangle highlights CM activities and functions. CM typically intervenes on the right side of thehealthcare continuum with individuals who benefit from CM, using secondary and tertiary prevention activities.• The middle triangle is the area where clinical interventions may fall in both DM and CM. These are patientswho need assistance with care coordination but do not require either extensive DM or long-term CM services.• The purple bar indicates the MM requirement to link UM, CM, and DM activities to outcomes of readiness,quality, cost, and access. Outcomes are the foundation of MM activities in the Military Healthcare System(MHS).Source: 2001 DoD Population Health Improvement Plan and <strong>Guide</strong> (see Executive Summary, CD-ROM Resource ES-1)Fig. 4 – Integrated <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Model (IM3)

<strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> <strong>Version</strong> <strong>3.0</strong><strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Management</strong> EssentialsPage 15Distinctions between UM, CM, and DMUtilization <strong>Management</strong> Case <strong>Management</strong> Disease <strong>Management</strong>Characteristics of Target Population• Cost-based approach• Most expensive patients, providers, andprocedures• Patients who may not be at the appropriatelevel of care• Patients not medically authorized for hospitaladmission and specific procedures• Patients who underutilize or overutilizeservices• Tracks over/underutilization of services andcosts• Reviews provider prescription patterns forhigh-cost brand versus low-cost genericmedications• Evaluates compliance with CPG requirementsor Drug Utilization Evaluations (DUEs) withinthe MTF• Individual approach• At high-risk for costly, adverse medicalevents and poor health outcomes• <strong>Medical</strong>ly, socially, and/or financiallyvulnerableMethods for Identifying PatientsAnalysis of Encounter or Claims Data• Searches for patients with patterns ofrepeated hospitalizations or ED visitsAnalysis of Pharmacy Data• Reviews medication profiles for variousindividuals or populations (medicationmisuse, elder non-adherence)Referrals• Population-based approach• Diagnosed with specific disease orcondition• Searches for patients with selectedICD-9 diagnosis codes• Searches for prescriptionscommonly used for specificdiseases (i.e., Albuterol forasthmatics)• Aggregate data in terms of practice patternsfor referrals• Prospective review of referrals• Referrals meet Severity of Illness and Intensityof Service criteria (InterQual ® )• Identifies patients in need of more intensiveinterventions whose length of stay might belong and resource utilization high• Provides opportunity to coordinate with casemanagement• Tracks appropriateness of care• Providers who identify patients as “highrisk” or “vulnerable”• Self/family referrals• Specific beneficiary screening criteriaPreadmission/Concurrent Review• Identifies expensive, complex cases (redflags) prior to/during admission• Identifies organizational processes thatneed to be streamlined to better addresspatient needs and increase efficiencyPatient Education• Providers who identify patientswith a particular diagnosis orcondition• Identifies patients with specificdiseases/conditions who couldbenefit from an outpatientdisease management program formonitoring and reinforcement ofpatient/family education• Generally no formal education; however,patients should be informed of the differentlevels of care and the appeal process• Providers are educated on recurring initiativesand roles in process improvement• Not applicable (uses InterQual ® and MillimanAmbulatory Care <strong>Guide</strong>lines TM criteria, whichare based on best practices during utilizationreviews)• Moving toward better use of information inclinical practices, identification of needs andreferrals to targeted support services; andgreater use and more consistent delivery ofevidence-based practices• Generally no classes developed by theprogram itself, although may refer toexternal classes• Generally no standardized curriculum• Generally no standardized educationalmaterials; individual-specificRelative Reliance on National, Evidence-based, Disease-specific <strong>Guide</strong>lines• ModerateRelative Reliance on Protocols and Standardization• Moving toward better use of informationin clinical practices (i.e., critical pathways),identification of needs and referrals totargeted support services; and greater useand more consistent delivery of evidencebasedpractices• Program may have developed itsown classes• Standard curriculum• Standardized educational materials• Tailored to individual situation• Extremely high• HighSource: Chen, A., et al., (2001, March). Best Practices in Coordinated Care. Mathematica Policy Research Institute, Inc.Fig. 5 – Distinctions between UM, CM, and DM