Autumn 2007 - British Milers Club

Autumn 2007 - British Milers Club

Autumn 2007 - British Milers Club

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

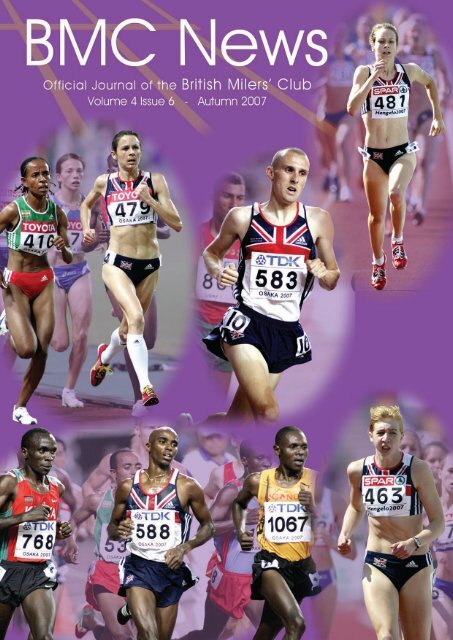

From the pen of the Chairmanby Tim BrennanWelcome to the autumn addition of theBMC news. At this time of the year wealways look back at the season justgone. In the World Championship wesaw some fine runs particularly from JoPavey and Mo Farah, but alas nomedals. However most of those in theendurance team are young andimproving, and missing from the teamwere our two European 800mmedallists from last year. In theEuropean U20 and U23championships we did pick up medalsand further cause for optimism shouldcome from the results of our own BMCGrand Prix. Elsewhere in the magazineyou will find a full statistical summaryand what it shows is a great rise instandard compared to previous GrandPrix seasons. The greatest improvementcan be found in the Women’s eventswhere times close to 2 minutes or 4:10are now common in our 800m and1500m races.At the Streford Grand Prix we hostedthe Emsley Carr mile and also acelebration of the 50th anniversary ofDerek Ibbotson’s world mile record. The3:54 winning time was a great result asbefitted the occasion. At each staging ofthe Emsley Carr mile a book is signedby the athletes competing and it nowincludes most of the all time great ofthe event many of them <strong>British</strong>. TheBMC is not a historic society but byrecognising the achievements of thoseBrits who have led the world it mayhelp today’s runners realise what canbe achieved.Away from the Grand Prix we had ourmost comprehensive ever series ofregional races. At Exeter we have builtup over two years to stage meetingswhich regularly attract over a hundredentrants. Others such as Eltham havealso built up numbers. With a growingmembership and full Grand Prixmeetings the regional races will fulfil anincreasingly important role.This autumn we will be the staging twotraining days for senior athletes atWatford and Trafford organised by LiamCain. We felt that senior athletesoutside of national squads were lackingopportunities to meet, train togetherand gain some coaching advice. TheBMC academy has led the way intraining courses for young athletes andhopefully the senior version will proveequally successful. To check our hunchwe went direct to the athletes in asurvey to gauge interest and receivedstrong backing for the idea.One area where the BMC sometimesreceives criticism is that our pacedraces mean that athletes do not learnhow to employ tactics in their racing.An article elsewhere in this magazineexplains our thinking on this. We canalso help by providing advice on tacticsand David Lowes addresses this inanother article.Although this is now the close season,there is plenty happening with the BMCcross country at Bristol, our academycourses, senior training days, and thenational endurance coachingsymposium. I hope you will enjoy andbenefit from these events.BMC Coach of the Year 2008BMC COACH OF THE YEAR 2008 - ANDY HOBDELLOther Nominations George Gandy, Norman Poole, Trevor Painter and Gavin Pavey.BMC ATHLETE OF THE YEAR 2008 - JO PAVEYOther Nominations Mo Farah, Michael Rimmer, Elizabeth Brathwaite.BMC YOUNG ATHLETE OF THE YEAR 2008 - STEPH TWELLNo other nominations.FRANK HORWILL AWARD FOR OUTSTANDING SERVICE TO BMC - DAVID LOWESBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 1

Hippocrates Answer a QuerybyQuestion: I hear a lot about strengthtraining for runners. What do youthink are the key muscle groups tostrengthen for injury prevention and toenhance performance?Without doubt, the main concern for allrunners is to enhance the power andflexibility of all leg muscles. While corestability has received much publicityover recent years leg injuries outnumberabdominal trauma by about thirty toone. That said a runner should not becontent until sixty straight leg curls canbe done in a minute.With regard to the correlation betweenperformance and leg strength the BMCwere the first to reveal that elite 800metre runners could hop 25 metres in10 hops minus on each leg and couldsquat fully and rise with a barbellloaded to bodyweight. Those who failedthese two tests had significantly poorertwo laps.A fallacy that still echoes today is thatbig mileage is all that is required tostrengthen leg muscles. Dave Bedfordwas an advocate of this belief and sadlyin due course when athletes could keepup with him! He was easily outsprinted in a close race because hislegs possessed no power for sprinting.However, many Kenyans have admittedto doing no specific weight training fortheir legs. It seems that frequent weeklyexcursions of 10k distance which startat 1500 metres above sea level andascent to 5000 metres has providedsufficient overload on leg muscles torender them the perfect runningmachine.This reminds me of an obscure and notwell publicised bit of researchconducted by the French some 25years ago. Six athletes were asked to dospecific leg strengthening exercisesevery other day and six others wereasked to do the same frequencyrunning up and down a 1 in 10 hill for40 minutes. Both groups were testedbefore and after the 12 week trial andthe hill runners improved their legstrength 10% more than the weighttrainers. We can make a fewgeneralisations about all round legstrength:1. Women generally have strongquadriceps and weaker hamstrings.Amadeus2. Men generally have strongerhamstrings and weaker quadriceps.3. Strong quadriceps which supportthe knee prevent cartilage less in theknee.4. If the hamstrings are not 66% asstrong as the quadriceps thehamstrings are prone to injury.5. A diet lacking adequate iron,calcium, vitamin C and the mineralboron will undermine bone densityand increase the possibility of injury.Vitamin C has an affinity forcartilage.6. A diet lacking the vitamin B complexwill undermine muscle status.There are seven danger zones from thepelvis down:The quadriceps from the knee upwards.Osteoarthritis of the hip which is theprogressive wearing of cartilage in thehip and affects mostly older runners.Iliotibial band syndrome which causespain from the outer side of the thigh tothe knee.The hamstrings at the back of the thighcan strain at the origin in the buttock orin the belly halfway down or in theinsertion just behind the knee.Iliopsoas strain can occur from theinside of the pelvis and the front of thelower part of the spine to the front ofthe thigh and is associated with overenthusiastic initial hill running. Gluteusgroup of the upper bum which canaffect the sciatic nerve and down theouter hamstring.The adductor which is the inner thighmuscle can be strained. Most of theabove are caused by lack of strengthand sudden changes in training anddoing too much too soon.4 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Bill Marlowe, former national coachand mentor to Peter Radford who brokethe 200 metres world record 45 yearsago, was a big believer in powerhopping on each leg since it spedrunning action where momentarilybodyweight rested on one leg. Start offby marking out 10 metres on grass ortrack, aim high and long. Repeat twiceon each leg. Extend the distance weeklyby 5 metres a time to 25 metres andthen switch to a gradual gradient. Thisshould be done every other day. STOPIF YOUR KNEES START ACHING. Legup against resistance, other leg downagainst resistance in a back lyingposition. This is a favourite of the oldSoviet coaches. A partner holds theraised leg under the heel at 45 degreesangle and the lower leg is presseddown by the partner’s foot. On thecommand “Go” the athlete exertsmaximum pressure against thepartner’s hand and foot for 10-seconds.Change positions with partner. Theisometric contraction should beincreased by 5-seconds weekly to amaximum of 30 secs and should bedone three times weekly.Research has proved that single legstrengthening work results in greaterstrength gains than two-legged efforts,and the single squat is where to start.Put weight on the bar of a Smithmachine and rest the bar on the backof your shoulders and upper back.Squat down thighs parallel to theground, knees above your ankles. Asyou lift yourself back up, lift one leg offthe ground letting the other leg supportall your weight. Once back, place theraised foot on the ground. Repeat theprocess taking the other leg off theground and repeat 12 times alternatingthe legs. Start with half bodyweight onthe barbell. This can be done without aSmith machine but squat stands will berequired and work with a partner.Repeat three times weekly and increasethe load by 10kg a week to maximum.Use a hamstring curl machine andoperate with one leg at a time curlingyour foot into the buttock. Start with 6repetitions on each leg with acomfortable load. Add 5kg per leg perweek to maximum. In the absence ofthe availability of a machine asubstitute can be to lie face down on atable with knees over-hanging the edge.A partner provides resistance to the curlby applying pressure with the hand tothe heel.The superman exercise involves lying inthe prone position with arms extendedout in front. Arch your lower back sothat your arms and legs come off theground in a flying position. Hold thisposition to a maximum effort and restand repeat. To toughen the exercisemove the legs up and down nottouching the ground.To stretch the hamstrings effectively usethe backside burn which involves lyingon your back with the right foot on thefloor, bend it back so that the knee ispointing up. Cross your left leg on yourright knee and pull your right leg intowards your chest to stretch thehamstring. Hold for 20 seconds andrepeat with the other leg.It should be stressed here that thestrengthening of weak legs is one of themost difficult parameters to improve. Allthe exercises listed should be donethree times a week for 12 weeks, twicea week for 12 weeks and once a weekthroughout the rest of the year.The sarjent jump is a quick way tomeasure leg strength gains. To do thisface a wall with arms raised fullyagainst the wall, make a mark with thefingertips end. Stand sideways anddampen the fingertips of the handnearest the wall. Crouch down and leapup with maximum effort banging themoistened fingertips against the wall.Measure the distance between the twomarks. A distance of 20 inches denotesmoderate leg strength and above 30inches exceptional power. It should benoted that the weight of an athletemust be considered in assessing theresult. A runner of 11 stone who has afigure of 14 inches will have strongerlegs than one of 10 stone with thesame reading.BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 5

Are you really clued up onRunning Knowledge?There is a danger when obtaining any qualification by examthat one considers that one has very little more to learn. Oneof the problems in becoming a qualified distance runningcoach over recent years is that emphasis is placed onattending official lecture courses and compulsory reading hasbeen neglected.The official AAA instructional manuals on distance runningstarted around 1954, the first by Jim Alford who was anational coach and former Empire Games gold medallist. Thebooklet described fartlek, paarlaufs, repetition running for alldistances, race tactics and successful steeple chasing. Oneitem of interest in the manual was the fixing of the maximumtime for jogging recovery distances after repetition running,this was not more than 45secs per 110yds or 3mins per440yds.About 15 years later Tony Ward was asked to rewrite themanual. At the time he was employed by the SouthernCounties as an administrator and was formerly SouthWestern Counties coaching secretary. He pioneered sanddune training weekends, the first at Braunton and theremainder at Merthyr Mawr, which were supported byathletes from all parts of the U.K.by Nevern RussellThe next AAA manual had no less than three contributors:Dr. Ray Watson dealt with the physiology of running whichincluded a detailed analysis of blood requirements forsuccessful running. Steve Hollings wrote perhaps the bestsection on steeple chasing yet produced in the UK and HarryWilson comprehensively covered the needs for success from800 to 10,000 metres.The final official distance running handbook came around1984 and had a new title - ENDURANCE RUNNING byNorman Brooks, the then national coach for NorthernIreland. This was universally claimed as a fact-packed workof great quality.Coaches are recommended to obtain all the officialhandbooks listed from established athletics book dealers whoadvertise in AW.Tony Ward also produced an excellent book - MODERNDISTANCE RUNNING around 1964 in which he forecastthat world-class 800 metre runners would have to meetcertain minimum strength standards and advocated strengthtraining for all distance runners.Ward’s book included more physiological data about runningtraining and had some amusing quotes at the beginning ofeach chapter.A year after Bannister’s first sub 4 mile, his adviser, FranzStampfl wrote a book simply calls Franz Stampfl on Running.The best recommendation for this book comes from TerrenceSullivan, a white police inspector in SouthernRhodesia, who, unable to find a coach therebought the book and did precisely everythinglisted and six months later became the first manon the African continent to break 4 minutes forthe mile.The book dispelled the common rumour thatwhen one could do 10 x 440yds with 440ydsjog in 2 minutes averaging 60secs per quarterone was ready to run sub 4. Other sessionsrequired weekly were 5 x 880 yds with 880 jogaveraging 2mins per rep and 1 x three quartersof a mile in 3 minutes minus.Some 20 years later Stampfl reduced therecovery jog to half the distance of allrepetitions. Thus we read that his protégé RalphDoubell of Australia could rattle off 20 x 400 in60secs with 200-jog recovery in one minute.Doubell equalled the 800m-world record and6 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Although the book is primarily about road running withnumerous pocket histories about great distance runners, thephysiological date is vast with a very revealing section onalleged legal aids to performance, which appear to be awaste of money in the main.Finally, there are some books of a biographical andautobiographical nature, which coaches should acquire ofnecessity and athletes are advised to read and these include:THE LEGEND OF LOVELOCK, THE LIZ COLGAN STORY, andTHE STORY OF ZATOPEK published in his county in English,THE 4-MINUTE SMILER, THE KELLY HOLMES STORY.The BMC NEWS is published twice a year and since 1963eighty-eight editions have been issued. These invariablycontain at least two instructional articles per issue and thequizzes are greatly appreciated. It says much for the contentof the journal that twenty-one articles have been reproducedin the Track and Field News manuals LONG DISTANCERUNNING and MIDDLE DISTANCE RUNNING. Bothmanuals are made up from contributions from around theworld. Early editions contain very informative articles fromSoviet coaches.MODERN ATHLETE AND COACH published in Australia hasalso published articles that first appeared in the BMC NEWS.One quiz published in the BMC NEWS 15 years agoconsisting of twenty questions was so comprehensive that aCommonwealth country decided to adopt it wholesale as thetest for what was called the Master Coach Award!So, we can say that to be well read in middle distanceknowledge your bookcase should contain from thirty to fortybooks if a novice and forty to fifty books if experienced and ifa fanatic thirsting for the ultimate answer you will probablyhave over a hundred books allied to the subject of runningfaster.Hippocratic opinionQuestion – Is L-Carnitine taken as a supplement of use toendurance runners?Theoretically it is. It’s synthesized in the body from theamino acids lysine and methionine. Its natural source isfound in avocados, dairy products, lamb, beef and tempeh.The theory is that when glycogen runs out more fat ispushed into the mitochondria by l-carnitine for use as fuel.Research reveals that it only works with athletes who havevery poor blood circulation of the legs. However, Dr. MichaelColgan in OPTIMUM SPORTS NUTRITION asserts that twograms a day significantly increased the use of fat in one trialwith athletes. It also aids loss of weight in the obese. Sinceeven moderate exercise depletes l-carnitine reserves,endurance runners need to have an adequate daily intake.Muscle fatigue and cramps are said to be symptoms of adeficiency.L-carnitine is expensive and in theory might be useful tomarathoners and ultra-marathoners.8 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Publicity OfficerThe BMC are seeking to appoint publicity Officer.We are looking for an enthusiastic supporter of the BMC who can help us make sure our activitiesare well reported across all forms of media including the athletics and national press.Those interested should contact the Chairman at "timbrennan@britishmilersclub.com"“None of you has a clue...”by CassandraThese derisory words came from a UKAthletics employed endurance coachsitting on a panel of coaching “experts”to advise how best to train juniorathletes to Olympic level. The venuewas St.Mary’s College in Twickenhamin late July <strong>2007</strong>. The expertsconsisted of a group of three former GBinternationals one of whom was anOlympic silver medallist, and acoaching administrator plus theaforementioned accuser. Only a dozencoaches attended, the mass ofaudience was made up from juvenilesattending another course at the college.Our BMC observer commented after theseminar, “I did not come away with oneuseful bit of information. I also questionthe make up of the panel, just twopractical coaches and the rest with noknown coaching expertise.”Well, the writer has coached athletesfrom a young age to make theOlympics, CommonwealthGames and World CrossCountry Championships,and here are his views.Type of training through age groups14-16 years - Emphasise importance ofeating moderate sized meals every 4hours and the avoidance of a high fatdiet. Practical physiological testingevery 12 weeks which will revealpossible weaknesses in flexibility, legstrength, general strength, enduranceand speed.Having told the coaches present thatthey were clueless on the subject hedid not give one practical bit of helpfuladvice on how it could be best done!Nor did anyone on the panel produce ahandout to peruse at leisure. A practice,which is routine on BMC seminars.There were no discussion groupsorganised to debate subjects from thepanel, for instance, one group couldhave been given 10 minutes to discussthe frequency of training sessions fromage 14 to 18 years, while anothergroup could have discussed theprogressive volume to be done duringthat age zone.Frequency of training14-16 years - strictlyevery other day16-18 years - two daysconsecutively with thethird off18 years onwards - fourdays consecutively withthe fifth off21 years onwards - twicea day on non tracktraining days, a total ofnine training sessions aweekBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 9

The use of relays with large groups overvarying distances, for instance, two atbase and one at the 200m mark for 15minutes, and a 5-man team with twoat base and one other every 100metres. Five minutes duration.16-18 years - Planning a race programme.Discuss racing tactics. Continue testingprocedures to discover weaknesses.Steady runs not less than 25 minutesduration and not more than 70 minutes.18-21 years - Deciding best event.Correction of weaknesses revealed bytesting. Summer volume - 45mpw.Winter - 60mpw.21 years on wards - Emphasiseimportance of training at differentpercentages of the VO2 max. Includechange of pace sessions. Always givepure sprint sessions. Keep testing.Summer volume - 50mpw. Winter -70mpw.Richard Amery, a well known athleticscoach and writer from Australiabelieves, as did the late Harry Wilson,that young athletes should be taughtgood running technique at full speedand during steady running. The keyword being relaxation and no bodymovements hindering forwardpropulsion. He also advocates a widerange of different activities to avoidboredom in the young.Practical TestingEndurance - How far can the athleterun in 15 minutes? The target formales is to run 5k distance as soon aspossible. For females - 4,400 metres.Speed - Sprint 40yds or 36.6 metres inunder 5secs males, 6secs females.Elastic leg strength - Hop 25 metres oneach leg. The target is 9 hops formales and 10 for females. A poorhopper is ALWAYS a poor sprinter. Aweaker leg MUST be corrected.MUSCULAR ENDURANCE - Press-ups,straight leg abdominals, squat thrusts.The target is 60 of each in one minute.Height/weight ratio - a 5ft.6ins/1.676mathlete should not weigh more than117 pounts/53k female and 129pounts/58kg, male.Other useful tests include squat andrise with bodyweight on a barbell for legstrength and a vertical leap of over 20inches measured from extended armand fingertips facing a wall andmarked, turn sideways and leap upmaking a further mark. Measure thedistance between marks.Note that improving leg strength is amost difficult process requiringdedicated every other day workouts forseveral months. Lack of leg strength isALWAYS associated with poor sprintspeed. An interesting observation byEast German coaches is that if a boy of14 years ran for 35 minutes daily fivetimes a week for 4 years, his 1500metres time would improve by 10seconds a year without any specialisedtraining. Why? Because during thattime he is growing and getting stronger.Makes you think doesn’t it?10 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Talking pointsUnfortunately, AW does not alwayspublish letters, which seek to redresswrong information, and in this articlesome highly questionable statement bycorrespondents are challenged.An anti-distance running coach articlesuggested that Dave Bedford who brokethe 10k world record and won majorcross-country titles was self-coached.Dave was coached by BOB PARKER ofParkside AC from the age of 14 and inthe last two years of his career by JohnAnderson and Bob mutually.An interview with a former female UKrecord holder from 800 and 1500metres gave the impression that the lateHarry Wilson was entirely responsiblefor her success. In fact, this athletereached international selection yearsbefore Harry’s appearance on the sceneunder the guidance of ANNE HILL anoted Welsh coach. Anne also had twoGB international sisters who were takenover by Harry who at the time was anational coach. ANNE HILL alsocoached a European juniorsteeplechase medallist in spite ofsuffering from a chronic healthproblem.An editorial observation in AWsuggested that the Balke Testmentioned in an article was not asaccurate as stated. The Balke Test is a15-minute run around the track andthe distance covered predicts the VO2max with 95% accuracy. Dill of theAmerican College of Sports Medicinetested six athletes on sophisticatedtreadmill equipment and a week lateron the Balke Test and found not morethan 5% difference overall. FrankHorwill compiled a handy graph to usefor this test, you simply looked at thedistance run, went up vertically to aline and then horizontally across to theVO2 max predication. Here is a table:Distance Run Predicted VO2 max4,000m 56.5mls. kg. Min4,400m 61mls4,800m 65.5mls – Elite female5,200m 70mls – Elite maleAn article in AW by two doctorsstressed the importance “… of havingenough fuel in the tank…” and warnedby Izak Van Nierkerkcoaches not to tell athletes to loseweight even if they needed to. Theinference being that most athletes arehalf-wits and would start going withoutfood. However, let us not beat aboutthe bush, the key factor in distancerunning is weight relative to height.The Dr.Stillman table is highly regardedby U.S. coaches and coaches andathletes here should get wellacquainted with it. This is how to useit:1. Find out the HEALTHY weight foryour height with this formula:Females – Allocate 100 pounds forthe first 5 feet in height and 5pounds for every inch thereafter.So, if you are 5ft 6ins tall aHEALTHY weight would be not morethan 176 pounds. Your racingweight should be LESS than this.Males – Allocate 110 pounds forthe first 5 feet in height and 5.5pounds for every inch thereafter. Ifyou are 6 feet tall a HEALTHYweight would be not more than 176pounds. Your racing weight shouldbe LESS than this.2. Don’t start missing meals if you arenot of a healthy weight, if you arerunning for 1 hour daily you willneed 1,000 calories for that andanother 2,500 calories to maintainbone and muscle health. Thismeans moderate sized meals every4 hours containing fruit, vegetablesand whole grains, fish and somemeat.3. Train more in the morning. This willelevate the metabolic rate for severalhours afterwards.4. Don’t snack between meals.5. Obtain OPTIMUM SPORTSNUTRITION by Dr. Michael Colgan,which gives expert advice on how toBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 11

avoid “ugly fats”. Females in severetraining often do not menstruatewhich leads to loss of bone densityand prone to fractures. This occurswhen a female’s healthy weight fallsmore than 10% below Slillman’sspecifications. The simple answeris to look at the latest scientificfindings on prevention, whichinvolve the BIG THREE – 1 –1,000mg vitamin C daily. 2 –1,000mg calcium daily. 3 – Boronmineral tablets as prescribed bychemists or health food shops.Boron research is truly amazing inpreventing osteoporosis.6. Don’t eat the same food two daysconsecutively.The great thing about THE COACHmagazine issued quarterly under theauspices of AW is that our BMC man,Dave Lowes, is a regular writer withclarity and logic. Now, there are atleast a hundred runners to every fieldeventathlete and according to the lawof averages the journal’s content shouldreflect this. We can also back up thatfact with estimation that there are twohundred running coaches for everyfield-event trainer. However, the editorseems to have a bias for non-practicalarticles of a highly theoretical bent oneverything bar running. One articlewas followed by nearly four pages ofreferences! What a waste of space!This is a magazine for coaches, notscientists.The first editor realised that letters fromreaders were an important item ofdebate; the second editor chose toignore readers’ views.One regular contributor is a noted anti-BMC crank who has attached the clubvia various media outlets. It is amazingthat the owner of this journal, who is aBMC Vice President, should permit thisman space for his banal meanderings.He is currently writing on anatomy andphysiology, which can be read in FrankDick’s book of 20 years standing.Each issue should include interviewswith some of the BMC’s finest coaches,Poole, Gandy, Cain, Thompson, Coeand Turnball. A little tip if you wantsomething published, if you use atypewriter no matter how good thecontent, it won’t get published. It hasto be on a word processor, too muchbother to get it done again on a wordprocessor. This didn’t seem to botherthe first editor, let us hope it doesn’tworry the third editor just appointed.There may be a case for two differenttypes of COACH magazine, one for fieldevents and one for all aspects ofrunning. We hear that a stuff-shirtSenior Coach complained to the BMCAdministrator over the content of FrankHorwill’s column in the last issue.Frank took to task the arrogant conductof a paid UK Athletics coach at twomeetings and his slimy tittle tattle to hisimmediate endurance boss. Strange tosay, many thought it was somethingthat should be aired andcongratulations were forthcoming. Theidentity of the complaining coach hasnot been revealed but it seems he isthe type who would have grovelled tothe governing body in the past whenfaced with unfair criticism. Can anational coach serve two masters? Wehear that a national coach for a runningevent for which he is paid a salary hasalso been appointed the endurancecoach for a university and appears ontheir track three days a week. Onehopes that the other days of the weekare devoted to lectures, seminars andtraining days for the event for which hewas appointed. Alas, his particularevent is the weakest of all theendurance events. Perhaps UK Athleticsshould ask all national event coachesfor a detailed report every month onhow they have earned their salary.Golden timessub 1:45.0 marks.sub 3:34.0 marks.sub 3:53.0 (mile)Coe 23Elliott 15McKean 18Cram 18Ovett 12Elliott 9Cram 16Coe 11Ovett 12Cram 16Elliott 8Coe 5N.B. Johnny Gray 65!!!N.B. Walker 24, Scott 25,Maree 1612 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Letter to the editorDear Pat, Tim, Leslie and JohnI read with interest the UKa report ‘A future vision for track and field athletic competition’ and in particular the keyrecommendations for competition change. The recommendations that particularly caught my eye were:• More open meetings in evenings and in short formats.• More event specific competition for athletes based on ability not age.I immediately thought of the meetings organised by the BMC and in particular the regional meeting at Exeter. I coach agroup of 20 athletes aged 12 to 18 who run 400/800/1500/3000 metes. We are based in Bristol. On 30 May 2006, 10 ofmy athletes accompanied me to the BMC Regional meeting at Exeter where a series of 1500mtr races awaiting. Most werefirst season athletes, for all bar one this was a new experience. At the end of that evening, 5 had run a PB, 4 had competedin their first 1500 race and 1 had had an off night. All agreed it had been agreat evening, well organised, good competition and a fun time.We have continued to support this particular BMC meeting since that evening,all my athletes have competed, it forms a key plank in my group’s competitiondiary.The itinery for that and subsequent evenings is as follows.5pmleave Bristol6.45pmarrive at track6.30pm to 8pm register, socialise and warm up8pm to 8.45pm compete and/or cheer fellow group athletes on9pmcollect official results9pmleave track10.45pm arrive homeSo why do on average 15 athletes, parents and 2 coaches give up an eveningfor 45 minutes of action?The meeting is well organised, it starts on time, it has an appropriate number of officials. The venue is spacious, clean, hasgood parking and spectator facilities and serves refreshments. There is first class competition based on ability. Competingbenefits an individual athlete, (gain experience of hard racing in an environment that rewards effort). Competing benefits thegroup (teambuilding, travel and leave together, support each other on and off the track, shared experience to talk about infuture)To date my athletes have competed 120 times and recorded 64 PB’s (53%) at this meeting. (The group average is 41% PBperformances in all competitions). The confidence they gain through competing in a BMC environment stays with themwhen they subsequently compete for the club. Their new PB times become their new standard competition times; theybecome faster more confident athletes. Some of those who competed at the first BMC meeting I mentioned have graduatedto national competition. Just as important, no-one has become traumatised or left the group because they didn’t run a PB ata BMC meeting, they just put their heads down, train hard and get one the next time.I hope that the BMC meeting model has influenced the UKa report, it should, it works.RegardsAlan ThomasLevel 3 coach, BMC member - Yate and District Athletic <strong>Club</strong>BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 13

Dan Robinson ProfileBackground and Introduction toRunning1998, living in Wimbledon, joined agym in Putney; went 4 times a week,ran 10k in 37 mins each time, wasfootball training on Tuesday eveningsand playing a match Sat afternoons.Entered a few races, 1998 Wimbledonhalf- 1.23. Stroud, Wokingham,Camberly 1.16 - 1.14, after playingfootie the day before. Breakthrough ata 10k in Cheltenham; was narrowly2nd in around 32 minutes. (<strong>Autumn</strong>1998). On the same training ran 2.38in 1999 London Marathon, butprogressed at shorter distances and ran66.50 at GNR in 1999. (was running6 times a week all on treadmill, 45mins as fast as I could ( prob startingat 5.30 min miling & finishing at5.05). At this time was working asDuty Manager at health and Fitness<strong>Club</strong> in Henley on Thames. 2000london Marathon, ran 2.24. End of2000, moved back to Gloucestershire,and I linked up with Chris Frapwell.Dec 2000 broke 30 mins for 10k for1st time at Leeds. 2001, ran forEngland at a half in Enschede, 64.40,then ran Half trial in Glasgow, 2nd brit,64.27. World half, 52nd in 64.23.October 2001 ran 2.16.51 in FrankfurtMarathon.Work, Lifestyle and Support Set UpCurrently I work part time at a localschool, Beaudesert Park. 4 afternoons aweek as a games teacher asssistant.Also work for family propertydevelopment company based inNailsworth - mornings, Monday toFriday.Have some support from UKA; up to£3k per annum, to cover medicalinsurance, travel, training trips etc(haven't used all of it though).Supported by Stroud and Districtathletic <strong>Club</strong> and 1 or 2 localcompanies, Stag Developments andGriffiths Marshall accountants.Presentations at the club, photographs,Xmas party, AGM, mentions in localpress. Fitness Mill Gym have supportedme too, comp use of treadmill. Kitsponsorship with Adidas.Try to eat healthily. Don't worry toomuch about it when running 120 milesa week; just eat a lot, plenty of carbsand not much rubbish. Breakfast at8.30 after morning run. Lunch 12,baked pot or beans on toast + yog,fruit, energy bar. Bowl or cereal 4ishand supper around 7.30. Don't reallydrink alcohol when training hard,occasional beer or glass wine. Quite alot more in down time after marathon.No strength/conditioning/core (don'tknow what it is!) or stretching.I try to be in bed by 10 and also haveat least an hour kip in the day. Weeklymassage and monthly chiropractorduring marathon build upChris Frapwell is solely my coach now.Also receive input from Bud Baldarowho has been brilliant and verysupportive for a number of years.Chris has evolved my training quitegradually so that I can now cope with2x runs of more than an hour so thatafter 2 or 3 weeks i don't break downor get ill. Now I can do this and stillget some quality in my sessions (maybenot enough with my 10k and half pb's),and do a long run which some weeks isdone as a fartlek session, or with thelast 30 mins at a big effort.A big reason for my 'success' is thesupport of Chris and Jess. I speak toChris most days and see him at the<strong>Club</strong> as well as socially. Jess (my wife)has been the main bread winner since2001. Think it is my settled lifestyle,that has allowed me to get on withrunning, and all the other things thatyou need to do (eat right/get enoughrest etc) that has been a big factor.Jon Brown InsightsLearnt a lot from Jon B in Cyprus in thebuild up to Olympics. The importanceof recovery runs being a big thing. Atthat stage I don't think I quiteunderstood this. He would runincredibly easy on non session days,and be able to produce fantasticsessions when he needed to. (Whenhe did a measured 15 mile tempogoing thru 13.1 in 63 odd I knew hewas in great shape!). The ability toprepare very very well and produce aworld class performance when itmattered was inspiring. Veryprofessional, focused and confident inhis training. You could see it a bit thisautumn: 3 weeks from a 64.16 half inGNR he improved dramatically in 3weeks to 47.16 at Great South on afilthy day. Before GNR he knew itwould be a bit of a struggle but didn'texpect too much and big improvementscame quite quickly.Sample Training WeeksTraining Nov 2006(General endurance period)Monday:am - 45 mins easy/steady.pm - 50-60 mins easy/steady.Tuesday:am - 45 mins e/spm - 8/10 x 3 mins w/ 60 sec recovs.(on cycle track) plus w/up and down)or 6x5 mins w 90-2min recovs (recovsjogging slowly)Wednesday:am - 45 mins e/spm - 60 mins e/sby David Chalfen14 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Thursday:am - 45 mins e/spm - 70 mins e/s(Stroud AC club run)Friday:by Tim Brennanam - 45 mins e/spm - 15-22 x 1 min w/30-60 secrecovsSaturday:am - 40 mins v v easypm - rest or 40 mins v v easySunday:am - 90 -120mins e/sAPPROX 105 MILESTraining July 2006(Peak of build up for EuropeanChamps in August)Monday:am - 60 mins e/spm - 65 mins e/sTuesday:am - 45 mins e/spm - 8-12 x 3 mins w/60 sec recovs or6-8 x 5 mins w 90-2min recovsWednesday:am - 60 mins e/spm - 65 mins e/sThursday:am - 60 mins e/spm - 70 mins e/s(Stroud AC club run)Friday:am - 45 mins e/spm - Out and back session - out for 50mins back with 25x 60 secs, so 1hr 40of running. Or tempo run - 8 -16miles starting at just under marathon'effort' and trying to finish strongly (onun metalled surface, bike track/ canaltow path) - Occasionally on treadmill,though when I became <strong>British</strong> recordholder [treadmill only – he’s not THATgood yet – DC] for 10k. half marathonand 20 miles I went by time and notdistance covered!)Saturday:am - 40 mins v v easypm - 40 mins v v easySunday:am - 2 - 2.5 hrs e/s.pm - Go harder or easier depending onsession done on FridayAPPROX 130/135 MILESI train at 7.45am and again afterschool, depending on winter/summertimetable but usually around 4-5pmEasy runs can be slower than 7minmiling or quicker than 6, justdependent on how I feel that day.Training mainly done on canal towpaths and cycle track (60%+) roadand some runs on grass. Still someoccasional trips to the treadmillThe FutureNot really thought about Osaka yet,focussed on London. As it's my firstchance since 2004 to run a fast citymarathon course am quite intrigued tosee how a couple of 2.14Championship performances translate.It's easy to say it must be worth2.11/12 but obviously anotherchallenge to actually do it!I am unlikely to be around for 2012,will be 37 then, a big ask I think.Coming to sport late I may peak a bitlater than some though. 2008 inBeijing is my major target. I want tomake the team and produce ascompetitive a performance as possible.Think I should have run quicker for halfmarathon. I haven't really targetedmany whilst not in marathon trainingmay be one reason. Managed to dipunder 64 recently but really feel there isquite a lot more to come. I think that ifI am to get anywhere near 2.10 I needto be able to run 63 low 'comfortably'.I think it is possible but realise I am stilla bit away from that at the moment.No real aspirations for the track. Itwould be nice to have a 5/10k tracktime to be proud of, but hasn't seemedto fit in. Running Champ marathons inAugust seems to prevent any sort oftrack season. Think that having a go torun a decent 10k (sub 29) would bebeneficial to my marathon aspirations.Self AssesmentBeing small and light is physically wellsuited. Starting the sport late may havebeen helpful in bringing the mentalskills to handle the event’s uniquenature. Motivationally, current standardswhereby a 2.14 will usually ensureUKA selection to any majorchampionships is a big spur to keepworking intensely towards goals.Ed’s CommentMany thanks to Dan for providing theinsights on all the points I raised withhim. Since this profile he has run twofurther marathons, placing 9th inLondon in 2.14.11 having run the last20 miles in almost total isolation. Thenin late August he excelled to place 11th(and 3rd European) in the WorldChampionships in Osaka, in 2.20,running his usual patient style andpicking off numerous men with muchfaster PBs who had not adapted so wellto the very high heat and humidity.Having had the not too wretched taskof ‘managing’ him at a couple of ½marathons in Spain, he’s a greatexample of being highly driven whilstremaining a really affable andcourteous guy.He’s a lucky boy to get this far withoutany S+C or stretching, must be thecross-sport benefits of football!BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 15

Andy Norman Rememberedby Frank HorwillAndy became an Associate member of the BMC in 1969 and as the then secretary of the Met Police AC asked the BMC toorganise the Dave Prior Memorial Mile for five years when it was withdrawn at the request of Dave’s widow who hadremarried. Andy also invited the BMC to stage an invitation mile race in the Met Police AC championships.As a promoter in South Africa I heard, just before the Commonwealth Games, that he had organised a class 800 in CapeTown. I rang him up to get BMC member Matt Shone into the race. He observed, “He’s Welsh isn’t he?” I replied that hewas and wanted to get a qualifying time to run for Wales. Matt, who was staying with me in South Africa, ran a personalbest of 1:46.6 to make the Welsh team. From 1969 to 1986 I often rang Andy to get my athletes into major races at homeand abroad, he always obliged and they were treated generously.Andy became manager to the <strong>British</strong> national police team which competed abroad frequently. Every Wednesday, at CrystalPalace, the Met team trained under his supervision for several years.I would visit him every Friday afternoon at Chelsea police station where he was a station sergeant. Our conversations werefrequently interrupted with a constable coming in and announcing, “Andy, a phone call from Sweden” or “a phone call fromNorway”. I deduced from this that he was acting as an agent for athletes and also assisting in the promotion of majormeetings. This was brought to the attention of the Commissioner who asked for his resignation. He later became promotionsofficer to the BAF as well as agent to numerous world-class athletes. An unfortunate taped telephone conversation with asports columnist which was highly publicised led to his exitfrom the BAF, it later went bankrupt.He was a promoter in South Africa for ten years and then leftfor Jamaica to do a similar job.I am greatly indebted to Andy for getting me off a charge! Ihad been attacked in the Portobello Market one eveningwhilst putting a bag of money into a night deposit safe. I wasknocked to the floor, but got up and caught my assailant,who was charged. I then decided that I would, thereafter,carry a police truncheon in my car. Carelessly I left it in mycar outside my Hampstead flat. It was spotted by anobservant police sergeant who charged me with having anoffensive weapon. I phoned Andy for advice, he contacted theprocessing Inspector, who happened to be a leading fieldeventscoach, and the papers were destroyed.Andy did not suffer fools lightly and he did not like greedyathletes and once on the wrong side of him he did not forget.His legacy is that he was the first athlete agent when such aposition was unheard of. He was a self-made promoter to thepoint where no major meeting on the Continent couldmanage without his services.Many who plotted his downfall with the BAF thought his exitwould cleanse the sport. It did not. Others, less capable, wereto replace him. There are many pocket Andy Normanimitators in UK athletics.16 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Are tacticts important for middleand long distance athletes?Well thought out competition strategieswin races. Good physical and mentalconditioning will give you the edge overother competitors but without anexcellent tactical brain, success rateswill fluctuate immensely.Athletes can be extremely well preparedfor an event through hard work and behighly confident of success, but ifthe effort isn’t produced at theright time, physical and mentalattributes can be undermined.Good tactics can be onlysuccessful if fitness levels are highand self-belief matches them.Tactics are therefore vital tosuccess and are part of thetriumvirate that is needed for theperfect performance.There is a lot more to successthan good tactics in a race and insome cases these can be preemptedbefore a race, but moreabout that later!Tactics are defined as: ‘Anexpedient for achieving a goal’; ‘Amanoeuvre’ and also ‘A techniquefor securing an objective’.Therefore training and mindsetsmust be fine-tuned to cope withpersonal tactics and tactics thatthe opposition may enact.Some say you should go into a racewith Plan A and Plan B so that you areprepared in case it is not run the wayyou had premeditated. But in reality,perhaps if you have Plan C and Plan Das back-ups it may be helpful so thatnothing will upset the rhythm anddelivery towards a positive result.Although nowadays athletes areunfortunately judged by how fast theyrun by the media, with slow timesbeing given negativity even if theathlete has won his or her race, the artof tactics has lost some of its credibility.World records may be the icing on thetop of the cake, but tactics andwinning championships are the mainingredients and the essential mix forrunning faster than the opposition.Even if an athlete goes into a racewithout a preconceived plan, theirsuccess or failure will centre on notonly physical attributes, but how theydistribute their effort over the distanceof the competition.In this article, I will look at possibletactics and scenarios encountered at800m, 1500m, 5000m/10000m,marathon and cross country events plusindoor running.Tactics are rarely practised in trainingsessions and the more instances ofdiffering paces and positionalawareness the better. There are manyimponderables that dictate what tacticsshould be employed and these include:athlete capability, opposition capability,weather conditions, course layout andgeographical location, underfootconditions, number of competitors inrace, qualifying round or final plusqualifying times.In an ideal world an athlete shouldbe running their race feelingrelaxed, balanced and in controland ready to respond to anymanoeuvre or change in pace.Because of this the athlete shouldbe in a position to go with anincrease in pace from the front orfurther down the field. An instancewhere athletes get caught out iswhen running behind the leaderand someone goes past quicklyand the rest of the field follows.From being in a good position theathlete can end up at the backand boxed in whilst the newleaders take off and usually it israce over due to the loss ofmomentum. This is particularlyrelevant at the shorter distanceswhen response time is minimal.One of the biggest sins an athletecan commit is to either leavespace on their inside or move out intolane two when it is not necessary in thefinal 100m and allowing a rival to steala march with no effort or extra distancecovered on their part. This usuallydemoralises an athlete especially whenanother athlete goes past on the outsideat the same time and any impetus theyhad is lost.Athlete capabilityThis is not necessarily the ultimatepotential of the athlete but what shapethe athlete is in at the time of aBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 17

different and some may be flat, somemay be hilly and others will incorporateboth. Add to this twists and turns,single and multiple laps and varyingunderfoot conditions for cross countryand tactics probably play an integralpart as much as physical attributes.Races at altitude for sea-level athletesare very difficult indeed and althoughaltitude acclimatisation is essential,those that are born and live there havean underlying advantage. 5000m and10000m races in particular are verydifficult for sea level athletes thoughraces at the marathon at mediumaltitudes are not so difficult due to theaerobic requirements of the event.particular race. If the athlete is not asfit as they could be due to a previousillness or injury they may have toconsider running a much different raceto their normal plan to get as good aresult as possible.Opposition capabilityHow any one applies themselves in arace is down to the quality of theopposition and what tactics they mayemploy. Although some athletes areself-confessed ‘kickers’ preferring tofollow the pace and sprint for homeusing their superior speed,no one should ever expect any race tobe run one dimensionally. Alwaysexpect the unexpected is the best wayto approach tactics and don’t enter anyrace with only one plan, unless you area Bekele or Dibaba, and even theyprepare themselves for anything theopposition may throw at them.Weather conditionsClimatic conditions can affectindividuals dramatically and change theoutcome of races significantly. Runningin hot and humid conditions doesn’tsuit anyone, but some cope muchbetter than others and those that live inthose environments have a distinctadvantage. So if you are aninternational running in a major gamesin those type of conditions some sort ofacclimatisation will be needed to offsetthis disadvantage. Adverse temperatureisn’t always heat related and extremesof cold can be encountered in a winterseason, this usually affects athletes theleast, although some find it difficult tooperate efficiently. Rain very rarelyhinders athletes though if it is freezingcold as well then improperly attiredathletes will suffer. Wind is probably anathlete’s worst natural enemy and if thetactic is to run from the front then thestrength will be drained from them ifthe wind is particularly strong bybattling two elements, the field and theresistance of the wind. Obviously all ofthese things are exacerbated by thelonger the racing distance, heat inparticular will affect an 800m athletemuch less than an athlete competing ina marathon. Those running indoorsmay find the smaller running area andsloping bends problematic but oneadvantage is that the temperature isconstant and there is no problem withthe wind, so front running is a mucheasier option and indeed many do thisas they can control and dictate the paceto their satisfaction.Course layout andgeographical locationAll cross country and road courses areUnderfoot conditionsJust like racehorses some athletes runwell in heavy conditions whilst othersonly perform well on firm ground andthe lucky ones are adept on either.Deciding where to make a break orincrease the pace in such conditionsmust be given a lot of thought so thatmaximum impact can be made andmaintained.Number of competitors in raceAlthough not usually a problem for theelite athlete, mass fields in crosscountry and road races can hinderprogress and pace judgement. Howeverin track events the number ofcompetitors especially in 800m and1500m races dictates where the athleteneeds to be to strike for home. Inindoor races this requires even greaterattention due to the smaller and moredifficult running circuit and intelligentpositioning is almost as important forsuccess as physical prowess. Elbowsare pointed and arms bend at rightangles for a reason! They preventcompetitors running too closely andmake them run wide around bendsespecially in an indoor competition.Qualification raceTrack championships usually involve aminimum of heats and a final andqualifying is an essentiality and more18 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

often than not heats are run erraticallyand this can cause problems withbumping and in some cases accidentaltripping due to the uncertainty of thepace with athletes only wanting to doenough to qualify. It must beremembered that in track races athletesrun very closely together with minimumgaps between the athlete in front andeveryone is trying to occupy the insidelane so some sort of body contact isinevitable. Some races which athletesrun in are a last chance to reach aqualifying time and the pace neededmust be exactly what is required so thatthe athlete can maintain a strong paceright to the tape.800m TacticsStandard championship two lap raceshave eight competitors whilst somegrand prix races may have 10 on thestart line. As the first 200m is often thefastest, this is where jostling for positionand settling in occurs and where mostdanger of accidental heel clipping canhappen due to the speed of the athletesand no one wanting to give any quarter.After breaking from the lane draws theathletes should aim to reach the 200mdistance in lane one or two in asstraight a line as possible. Manyyoungsters tend to break almost at rightangles which has two effects: extradistance covered and dangerous inrespect of impeding other athletes.The 800m is probably one of the mostdifficult races to run tactically withpositional awareness vital for success. Itis one race where it would be rare in achampionship if anyone actually ranexactly 800m due to the manoeuvringto gain the position the athlete requires.To run the perfect race requires asmooth passage with little or noslowing down or sudden increases inpace and no radical re-positioning. Asthe race is often termed an ‘extendedsprint’ any tactical errors will thereforebe costly.Championships can involve at leastheat, semi and final and planning howto qualify safely without too muchenergy loss can be a problem. Slowtactical races can present majordifficulties and qualifying takes on asmuch importance as winning a medalin the final. Some qualifying standardscan be tough with only the first orsecond to go forward to the next roundwith a large amount of fastest losersalso qualifying. Those in the first roundheats will have no idea how fast theremaining heats are going to be run, sodecisions will have to be made ifautomatic qualifying is going to bedifficult.Many close run races usuallynecessitate athletes finishing in lanes 2,3 or 4 to gain a clear run to the tape.In world record attempts the athletemay run much nearer 800m indistance due to simply following apacemaker. It is a fallacy that an athletemust hug the kerb to save energy andnot run over distance in the two laprace, positioning is always moreimportant than getting boxed in with nochance of getting out of that box.Obviously in 5000m and 10000mraces running wide for long periods willincur much extra distance and energywastage. An 800m athlete must bestrong, fast, positive, intelligent andaggressive, without those qualitiessuccess will be difficult.Depending on an athlete’s strengths:front runner, breaks with 200m to go orsomeone who waits until the final100m, being in the position that allowsthose things to happen is crucial. Asthe race is only over 800m any majortactical faux pas usually results in anegative outcome. A 3 or 4 metre gapmay be nothing over 1500m and abovebut at this distance it can feel like theproverbial mile. Running on the leader’sright shoulder is a wise move andallows an easy vantage point to movepast when ready and also allows aposition to cover any breaks frombehind. Most male races involve muchfaster first laps than last laps with thefirst 200m usually run far too quickly.Most females tend to run moreeconomically, although there are alwaysexceptions.If you study various races and athletesas examples you will notice extremes oftactics but all with the same outcome -victory. In the Athens Olympics KellyHolmes ran from the rear of the fieldand ran at her pace which was virtuallythe same for each 200m split andfinished faster than anyone else.This was a supremely confidentperformance and needed great mentalstrength to be successful.Yuri Borzakovsky is a profound run atthe back athlete and a notoriously fastfinisher, it works sometimes andsometimes it doesn’t, it worked at the2004 Athens Olympics though!The 1980 Moscow Olympics wasinfamous for two reasons: the favouriteSeb Coe ran a totally inept tactical racewhilst Steve Ovett bossed the race andreigned supreme. Indeed, Ovett in hisearlier days ran only to win and burstpast his rivals at 200m with suchspeed and power that he opened upinsurmountable gaps before theopposition could respond.At the top level, male races can be ranat 49-50 seconds for the first lap whichwill stretch the field out with theathletes working hard, but slower53-54 second paces will have the fieldmuch closer together with the athletesrunning in lane one and two at the bellready for any early strike for home.Indoor 800m races need even moretactical awareness with fewer passingopportunities due to the smaller arena.A good tip for running the distanceindoors is to never be out of the top twoplaces to cover any breaks or mishaps.Getting boxed in usually means disasterno matter what the ability of the athleteand those that can lead around thefinal bend and finish strongly willBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 19

usually be successful. Accidentalbumping and tripping are part andparcel of indoor running anddisqualifications are not uncommon.1500m TacticsAs you will see as I go through thetactical scenarios of each event that thelonger the distance competed over, theimportance of being in immediatecontact with the leaders has lesserimportance, but tactical awareness isvital to success no matter what distanceis run.As the 1500m is the first middledistance event to start on a curved line,close contact is inevitable in the first100m of the race. Many athletes willinvariably target the inside lane asquickly as possible, but in a fast race inparticular, athletes would be betteradvised to run the shortest distancepossible to the first bend and thensettle into the position that isappropriate to their plan.Energy conservation is important in the1500m and those that have adequateenergy supplies left for the last lapusually have a good chance of attainingtheir goals.Concentration is important in the1500m and the number of competitorsin a race will usually be 12, althoughsome invitational events will fit in manymore. If the field is strung out, thedistance between first and last can bemuch larger than in an 800m race andalthough the pace is generally slower,the gap cannot be allowed to get toobig if a strike for home is planned withmuch ‘traffic’ to negotiate to hit thefront.Some races over the years such as theEuropa Cup have producedunbelievably slow paces for three lapsbefore ending up as a 400m sprint.Other races like the 1974Commonwealth Games where FilbertBayi set an incredible pace over thefirst two laps which hadn’t been seenbefore seemed foolish, but he prevailedand with a world record! Athletes likeSteve Cram regularly upped the pacesignificantly over the final 500m-600mwith great success. Current worldrecord holder Hicham El Guerrouj hasthe innate ability to subtly increase thepace over the final 600m-800m in away that is energy efficient but alsodamaging to his opponents. KellyHolmes’ Athens Olympic winning runreplicated her 800m tactics, staying atthe back and covering any moves whennecessary, what it did allow her to dowas conserve energy for her final surgeover the final 150m. Athletes like RiuSilva and Fermin Cacho are noted‘kickers’ and like to follow and finishvery quickly and have been verysuccessful with those tactics at thehighest levels.In the 800m you probably aren’tallowed any tactical errors with so littletime to respond, but perhaps the1500m allows for some minorindiscretions with more time to react tothese providing the athlete has thephysical attributes to react to thesituation at the time. Most situationsrequire a ‘cool-head’ and those thatpanic usually end up at the back of thefield and theonly way oflearning how tohandle these isthrough practiceand experience.Pace distributionis thereforecrucial to theexecution of anyrace andunnecessaryincreases intempo early ormid-race willhave adverseeffects withanaerobicdeficiencies andlactateaccumulation which needs to bereserved for the end of the race.Indoor races over 7½ laps need muchconcentration and a fixation on wherethe athlete wants and needs to be inthe competition. If most of the fieldtends to pick up the pace outdoors with400m remaining then indoors this willbe with 2 laps to go and this can bepsychologically difficult with thejudgement of effort different as therewill be 4 straights and 4 bends tonegotiate. Pace distribution should beeasier however with times being givenevery 200m as opposed to 400moutdoors.5000m/10000mThese events are now becoming someof the hardest to be successful at due tothe awesome performances of theAfrican athletes at the highest level.They are almost turning out to be 11½and 24 laps of hard running and then a400m at break-neck speed and thatgoes for both male and female races.These races require great concentrationlevels no matter what level the athleteis at. It is amazing how many athletescan run good 5k and 10k races atcross country and on the roads but20 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

cannot run well once on a track. Everystep is the same on the track and theathlete knows exactly where they areand how far they have done and haveto go and this can be very daunting formany. Pace judgement is extremelyimportant for these events and too fasta pace in the early stages may prove tobe unwise later on. It is rare thatathlete’s come back from running toofast and they will suffer greatly with laptimes reflecting that.These events will have around 18athletes or more in them and it is nowcommon to see ‘double start lines’ toavoid congestion in the first 100m. Dueto the extra laps to be negotiated it isimportant to run as efficiently aspossible with lap times being mirroredas much as possible until the bell lap.Being in a comfortable position,covering the leaders is vital and asmooth run is the best way to saveenergy for the final 400m. However,mid-race bursts, surges and breaks with1000m or so remaining must beexpected, so positional and raceawareness is vital as in any other race.There are some athletes who will staynear the front for the entirety of the racebut never take the lead until the finallap. Their sole aim is damage limitationto their own energy reserves and savingtheir ‘kicks’ for maximum effect. One ofthe greatest at this type of tactic wasthe incredible Miruts Yifter who ranunbelievable speeds over the last 300mand Deratu Tulu also used similartactics in her great races.Looking at some past races illustrateswhat ammunition a top athlete needs tobe successful at these events which arenot only endurance events but onesthat require great speed and mentaltoughness. My all-time favourite race isthe 1976 Olympic 5000m final withLasse Viren running the last four lapsclose to 4 minutes and ‘outlasting’ anddemoralising the 1500m specialistswho were queuing up behind him with100m remaining and it was he whofinished the strongest and also thefastest in the sprint for the line running55 seconds for the final 400m and 13seconds for the last 100m. BrendanFoster liked to incorporate mid-racesurges of fast 400m efforts or longer tototally take the field apart, a tacticwhich was necessary due to his poorbasic speed. Eamonn Coghlan’s WorldChampionship victory in 1973 wasspecial in that he not only won, butwith 150m to go he started to celebratewhilst in second place due to hisabsolute confidence of winning! Amodern day great like Kenenisa Bekelecan run the race anyway that isnecessary, world record pace, mid racesurges or a blistering finish and that iswhy, at the moment, he is virtuallyunbeatable.The 5000m is not a championshipevent indoors but the 3000m is andthe 15 laps requires an unfluctuatingpace and being in close contact withthe leaders to cover any suddenincrease in pace. So total concentrationis vital with a constant focus on thefront of the field to anticipate anychange in tempo or personnel. A strongfinal 4 laps is necessary to get a goodresult along with a flat out last 200m.MarathonThe classic road distance of 26 miles385 yards is one where many top classathletes over the half marathon distancehave failed miserably. Endurance isneeded in abundance, butconcentration, patience and mentaltoughness are three other vitalingredients in this event. As pacejudgement is more important than inany other event to prevent energy levelsrunning out before the finish, carefullyplanned race strategies are vital. This isnot easy when the athlete is feelingfresh in the early stages and holdingback is imperative. It is the one eventwhere an athlete can be looking andfeeling great at 22 miles for example,and be totally exhausted at 23 miles.The mindset of a marathoner must betotally focussed on where they are inthe race and looking and thinkingahead too far can be disastrous.Although most will have pre-set pacetargets for each mile, the problem formany is deciding and knowing what todo when someone goes off muchquicker or breaks away at some pointin the race. Can the athlete be sure thatthe breakaway athlete will come backto them? This is where experience andpatience come to play a major role.For many marathoners the first 13miles is purely a settling in phase forthem, making sure they get to thatpoint as fresh as possible and then reevaluatingtheir plans. Their nextobjective may be to get to 18 miles in asimilar state and then start thinkingabout where or when they can make apush to win the race.As rhythm and pace judgement isparamount to success, even a slightincrease in pace at certain times in arace can be counter-productive. In a bigcity marathon it can be quite easy toget caught up in the atmosphere withan adrenalin rush once the spectatorsstart cheering you on and before yourealise it you have picked up the pacetoo quickly and begin to suffer soonafterwards.Marathon’s can have close finishes sospeed is also needed to ensure victory.Probably the most famous close finishwas the 2003 London marathon wherefive athletes entered the Mall togetherand at the finish only 14 secondsseparated the first seven, with only 1second between first and third.The 2005 New York marathon requireda sprint finish with a dip on the line toensure victory for Paul Tergat overHendrik Ramala. The present worldbest of 2-04.55 by Paul Tergat was setin Berlin in 2003 and he only won by1 second from compatriot Sammy Korir.Paula Radcliffe, the 2004 Athen’sBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 21

Olympics apart, has dominated herraces by huge margins and has run herown race plans and set gruelling pacesthat no one else could match whichshows how confident she is in her ownphysical and mental strengths.Cross CountryThis discipline is different to trackevents and usually there are no ‘cat andmouse’ tactics with races mostly run atan ‘honest’ pace. Invariably crosscountry races start off fast and the frontrunners pursue a hard pace throughouttrying to drop the opposition throughbetter strength levels or breaking awayon an uphill or downhill section of thecourse. However, pace judgement isimperative for success with racingdistances much longer for the 800mand 1500m specialists. Those in theleading pack especially will use somekind of ‘sit and wait’ tactics, decidingwhether to wait until the final 100m -400m or make a break with 800m ormore to go. A common way of breakingaway from the pack is to keep an eyeon the opposition’s body language, arethey suddenly breathing hard, are theyslowing down dramatically on a hill forexample?Whereas breaks from the opposition onthe track are usually positive, decisivemoves, on the country these breaks canbe subtle and more of a ‘wearing down’of the opposition and also demoralisingthem on a certain section of the course.Obviously the size of the entrants forcross country events can vary fromaround 50 to 3000 competitors andbecause of this and the nature of thecourse, getting into a reasonableposition after the start is very importantfor a positive result. The pace in crosscountry varies immensely with uphills,downhills, turns and underfootconditions and because of this asmooth steady run cannot be expectedand an athlete could be running at 4-20 mile pace at some stage and 6-20mile pace at others!A useful tactic in cross country races isto try and get 15m-20m on a rivalgoing up a hill and make a huge effortoff the top of the hill and try to keep itgoing for at least another 400m andthe 15m-20m can quite easily grow to50m or more due to the rival gettingdisheartened. In track races once thefield has settled everyone is running inthe confined space of one lane, but incross country the leading bunch can bespread over a much wider area andconcentration may be even moreimportant with a fixation on the leadersand also the course geography.Finishing speed is just as important asin track events and even after 12k itmay come down to the final 50m todecide the medals. Most cross countryspecialists are usually successful 5kand 10k track specialists and both thewinter and summer disciplines cancompliment each other. The pace thetop athletes run over firm, muddy, flator hilly courses is phenomenal and thespeed over the closing stages can bebrutal and to watch someone likeBekele is an education in itself. Ialways tell athletes and coaches alike towatch him at his best from the hipsdown and you would swear he wasrunning on a track and not strengthsapping grass and mud.OverviewGoing back to the start of this articleand summing up tactics as a means ofachieving an objective and a plan orskill to trick your competitors, it is clearthat a race is akin to a game of chesswith the moves to win similar, but howthey unfold depends on the oppositionand how you approach the event.Pre-race tactics or in some cases‘gamesmanship’ by fair means can beused to fool the opposition into a falsesense of superiority and these can bethe tricks in an athletes repertoire.Dialogues with other athletes conningthem into believing that you’ve beeninjured or ill and haven’t trained candupe them into believing that they willhave no problems in beating you. I’msure sprinters deliberately false start toupset certain competitors and haveplanned those manoeuvres weeksbefore to unsettle their rivals. Throwersmay intentionally throw a big practicethrow or a poor throw before thecompetition starts to mislead theentrants of the actual outcome. Someathletes warm-up in a different place towhere the opposition are and only getto the start line when necessary, thiscan elate or deflate the opposition andput their tactical plans in tatters. Otherathletes will appear arrogant, nontalkative,unfriendly in the warm-upzone, so the athlete must learn how todispel any negativity from thesemannerisms. It’s all kidology of course,but as long as it’s fair, it is part andparcel of tactical psychology. Athleteshave to be one step ahead of theopposition physically and mentally andit is often said that a race is won andlost in the warm-up area.Whatever race distance you run, if youare leading entering the home straight,stick to the inside lane and don’t movefrom it! It is amazing how manyathletes drift into the second lane andallow a hopelessly boxed in athlete afree run to the tape.Train hard and get in fantastic physicalshape but think long and hard how youwill get the best out of yourself andhow you will react to different situationsin competitions, in other words beready for anything!22 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Energy sources training prescriptionby Fox and Matthewsby Anton TimoshenkoEVENT ATP_PC and LA LA-O2 O2800 30% 65% 51500 20% 55% 253k 20% 40% 405k 10% 20% 7010k 5% 15% 80Specimen SessionsATP-PC and LA16x200 in sets of 4 with three times the time of rel as rest.Lap jog after a set. 8x 400 in sets of 4with twice the timeof rep as rest. Lap jog after set.Day 4 - O2-2x5k jog 2500m after each repDay 5 - O2-8x1200 jog 600Day 6 - RestDay 7 - LA-O2-8x400 in sets of 4x400In another section of their work, they suggest an alternativerecovery system after each repetition, when the pulse dropsto 130 beats a minute start another rep.Athletes and coaches should not follow the stated schedulestoo literally but use their own interpretation on how energysystems are best utilised.LA-O25x600 with twice the time of rep as rest. 4x800 insets of 2with the same time as rep as rest. Lap jog after each set.O23x1000 with half the time of rep as rest. 3x1200 with halfthe time of rel as restExamples800m Day 1 - LA-O2 -4x800 in sets of 2.Day 2 - LA-O2 -5x600Day 3 - ATP-PC-LA -16x299 in sets of 4.Day 4 - LA-O2-Repeat Day 1.Day 5 - LA-O2- Repeat Day 2Day 6 - RestDay 7 - O2-3x12001600m5000mDay 1 - LA-O2-4x800 in sets of 2x800Day 2 - LA-O2-5x600Day 3 - O2-3x1200Day 4 - LA-O2-As for Day 1Day 5 - ATP-PC and LA -8x400 in sets of 4x400Day 6 - RestDay 7 - O2-3x1000Day 1 - O2-6x1200Day 2 - O2-5x1000Day 3 - LA-O2-4x800 in sets of 2x800Day 4 - O2-As for Day 1.Day 5 - O2-As for Day2.Day 6 - RestDay 7 - ATP-PC and LA-16x200 in sets of 4x20010000m Day 1 - O2-6x1600 jog 800 after each repDay 2 - O2-10x1k jog 500 after each repDay 3 - O2-4x3k jog 1500m after each repBMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 23

Training sessions800 metresWeek 116 x 100 with 100 jog (45secs) or 2 x8 x 100 with 20secs rest and 5minsrest after first set.Week 28 x 200 with 200 jog(90secs) or 2 x 4x 200 with 100 jog(45secs) with5mins rest after first set.Week 36 x 267m (one-third of 800, 33mahead of 1500 start) with 3mins rest or2 x 3 x 267m with 90secs rest and5mins rest after first set.Week 44 x 4 x 200 as follows:- 15secs restafter 200 for the first set, 5mins rest.30secs rest after 200 for the secondset, 5mins rest. 45secs rest after 200for third set, 5mins rest. 560secs restafter 200 for final set.Week 54 x 534m(two-thirds of 800, finish34m in front of 1500m start). Cruiseto 400m and ACCELERATE over last134m. 5mins rest after each rep.Week 61 x 60-0 full out, 2mins rest, 1 x 200full out. 5 mins rest. 4 x 300 60 secsrest. 5mins rest. 4 x 150 60secs rest.Week 73 x 1,000 ACCELERATION RUNS, 1st200 – 64secs 2nd 200 – 62secs; 3rd200 – 60secs; 4th 200 –58secs; final200 – 56secs. Aim to start at 62secsand end with 52 secs; 5mins rest aftereach 1kWeek 84 sets of 2 x 300 + 1 x 200. 30secsrest after 300s and 5mins rest aftereach set.1500m/MileWeek 132 x 100 with 50m jog (20secs) or 2 x16 x 100 with 10secs stationary restand 3mins rest after first set.Week 216 x 200 with 100m jog (45secs) or 2x 8 x 200 with 50m jog and 3mins restafter first set.Week 310 x 300 with 60secs rest or 2 x 5 x300 with 30secs rest and 3mins restafter first set.Week 48 x 400 with 60secs rest or 2 x 4 x400 with 100 jog(30secs) and 3minsrest between sets.Week 56 x 500 with 100 walk(75secs) or 2 x3 x 500 with 30secs rest and 4minsrest AND 4mins rest between sets.Week 65 x 600 with 200 jog(75secs) or 2 x 3x 600 with 30secs rest and 5minsbetween sets.Week 74 x 800 with 200 jog(90secs) or 2 x 2x 800 with 100 jog(45secs) and 5minsbetween sets.Week 81 x 1200, 600 jog(4.5), 8 x 150 with30secs rest, or 2 x 2 x 1,000 with 200jog(90secs) and 5mins between sets.Week 92 x 2k acceleration runs as follows:-1st lap – 80secs; 2nd lap – 76secs;3rd lap – 72secs; 4th lap – 68secs;5th lap – 64secs. 5mins rest after first2k. Aim to start 2k in 68secs andfinish in 52secs.3,000 metresWeek 116 X 400, 200 Jog(45secs).Week 212 X 500, 100 walk (60secs).Week 310 X 600, 100 walk(75secs).Week 48 x 800, 200 jog(90secs).24 BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong>

Week 56 x 1,000, 200 walk(2mins).Week 65 x 1200, 300 jog(2mins.15secs)Week 74 x 1500, 400 jog(3mins).Week 83 x 2,000, 500 jog(4mins).Week 91 x 800 + 1 x 2000 + 1 x 200, jog200 after 800, jog 500 after 800, jog5mins after 200 and repeat. Halve therecovery time in due course when timeachieved totals BETTER than currentbest 3k time. For instance, if 1 x 800is done in 2:16 and 1 x 2k is done in5:40 and 1 x 200 in 34 secs TWICE,and your best 3k is 8:45(70/400).Half the rest time.Week 101 x 400, jog 100, 2 x 800, jog 200, 3x 1k, jog 300.1 x 3200, jog 400, 1 x 400.Week 95 x 1200, walk 100(60secs).Week 1020 x 400 with decreasing recoverystarting with 90secs rest anddecreasing by 15secs per lap (90-75-60-45-30-15) and then start therecovery system again with 90-75-60,etc. N.B. Tim Hutchings who placed4th in the 1985 Los Angeles Olympic5k in a PB of 13:11, rattled off 20 x400 in an average of 61.5secs at WestLondon stadium 14 days before hisdeparture to the Games. That’s sub12mins/5k pace.10,000 metresWeek 125 x 400, 10secs rest.Week 213 x 800, 20secs rest.Week 37 x 1600, 100 jog(45secs).Week 43 x 3,200, 200 jog(90secs).Week 510 x 1k, 30secs rest.Week 69 x 1200, 40secs rest.Week 725 x 400 as follows: one lap in67secs, next lap in 75secs, repeatedthroughout. This will give anaccumulated time of 29:34. Whenachieved, go for 67secs 400m followedby 70secs which will give a total timeof 28:32. Finally, go for a 65 lapfollowed by a 70secs one which willtotal 28:07.NB – sub 27mins is 25 x 64secs per400m. Better get used to it or take upgolf!5,000 metresWeek 112 x 500, 20secs rest.Week 210 x 600, 100 jog.Week 37 x 800, 100 jog.Week 46 x 1,000, 75secs restWeek 54 X 1600, jog 200.Week 63 x 2k, jog 300.Week 71 x 2,500, jog 300, 2 x 1200, jog200, 1 x 3200, jog 400, 1 x 400.Week 81 x 800, jog 100, 1 x 1600, jog 200,BMC News : <strong>Autumn</strong> <strong>2007</strong> 25