Warren Adams combines conservation and ... - Patagonia Sur

Warren Adams combines conservation and ... - Patagonia Sur

Warren Adams combines conservation and ... - Patagonia Sur

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

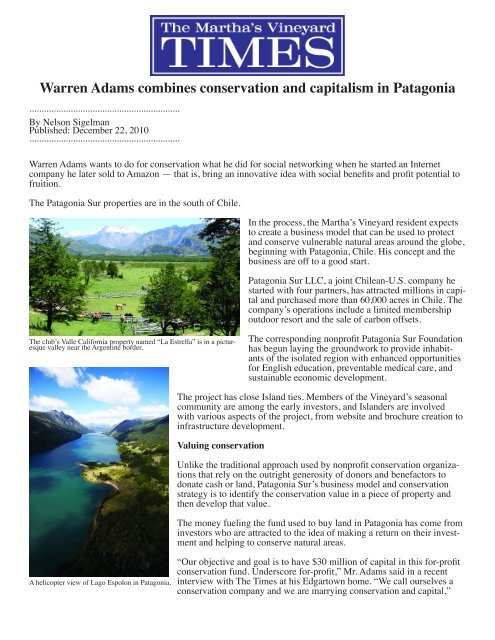

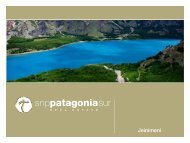

<strong>Warren</strong> <strong>Adams</strong> <strong>combines</strong> <strong>conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> capitalism in <strong>Patagonia</strong>..............................................................By Nelson SigelmanPublished: December 22, 2010..............................................................<strong>Warren</strong> <strong>Adams</strong> wants to do for <strong>conservation</strong> what he did for social networking when he started an Internetcompany he later sold to Amazon — that is, bring an innovative idea with social benefits <strong>and</strong> profit potential tofruition.The <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> properties are in the south of Chile.In the process, the Martha’s Vineyard resident expectsto create a business model that can be used to protect<strong>and</strong> conserve vulnerable natural areas around the globe,beginning with <strong>Patagonia</strong>, Chile. His concept <strong>and</strong> thebusiness are off to a good start.<strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> LLC, a joint Chilean-U.S. company hestarted with four partners, has attracted millions in capital<strong>and</strong> purchased more than 60,000 acres in Chile. Thecompany’s operations include a limited membershipoutdoor resort <strong>and</strong> the sale of carbon offsets.The club’s Valle California property named “La Estrella” is in a picturesquevalley near the Argentine border.The corresponding nonprofit <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> Foundationhas begun laying the groundwork to provide inhabitantsof the isolated region with enhanced opportunitiesfor English education, preventable medical care, <strong>and</strong>sustainable economic development.The project has close Isl<strong>and</strong> ties. Members of the Vineyard’s seasonalcommunity are among the early investors, <strong>and</strong> Isl<strong>and</strong>ers are involvedwith various aspects of the project, from website <strong>and</strong> brochure creation toinfrastructure development.Valuing <strong>conservation</strong>Unlike the traditional approach used by nonprofit <strong>conservation</strong> organizationsthat rely on the outright generosity of donors <strong>and</strong> benefactors todonate cash or l<strong>and</strong>, <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong>’s business model <strong>and</strong> <strong>conservation</strong>strategy is to identify the <strong>conservation</strong> value in a piece of property <strong>and</strong>then develop that value.The money fueling the fund used to buy l<strong>and</strong> in <strong>Patagonia</strong> has come frominvestors who are attracted to the idea of making a return on their investment<strong>and</strong> helping to conserve natural areas.A helicopter view of Lago Espolon in <strong>Patagonia</strong>.“Our objective <strong>and</strong> goal is to have $30 million of capital in this for-profit<strong>conservation</strong> fund. Underscore for-profit,” Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said in a recentinterview with The Times at his Edgartown home. “We call ourselves a<strong>conservation</strong> company <strong>and</strong> we are marrying <strong>conservation</strong> <strong>and</strong> capital,”

Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> is not the first person to see profits in l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>conservation</strong>. His said his company is unique in itsscope.Where others may sell a <strong>conservation</strong> restriction or carbon offsets, his plan is to utilize all the <strong>conservation</strong> attributesthe l<strong>and</strong> has to offer. “We are a sustainable l<strong>and</strong> management company <strong>and</strong> we look at as many of thosethings as make sense,” he said.At present that includes recreation, eco-brokerage, “ecologically-friendly” aquaculture, agriculture; <strong>and</strong> the saleof carbon offsets.“We think it’s an innovative model for <strong>conservation</strong>,” he said. “Compared with most <strong>conservation</strong> projectswhere people donate money <strong>and</strong> the organization uses that to buy <strong>and</strong> protect l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> people get a tax break— <strong>and</strong> those are all good — we think our model uses capital more efficiently. We are able to attract capital frompeople because we say, ‘invest a million dollars with us instead of donate.”Still dreamingBy his own admission, Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> thinks big. In 1996 the Harvard Business School graduate was living <strong>and</strong>working in Cambridge on a startup company, PlanetAll, generally regarded as the first social networking site onthe Internet. In 1998, the 33-year-old sold his company to Amazon.com for $100 million in Amazon stock.In a recent conversation with The Times, Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> described what led him to Chile <strong>and</strong> his new company.“Entrepreneurs can’t stop dreaming,” he said.Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> worked for Amazon for a few years after he sold his company. In2000, <strong>and</strong> before he <strong>and</strong> his wife Megan, also a Harvard graduate, had children,they set off to travel the world.“And that’s when we fell in love with <strong>Patagonia</strong>,” he said. L<strong>and</strong> was $100 anacre in one of the most undeveloped <strong>and</strong> beautiful parts of the world. In thenext seven years Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> was involved with nurturing other start up companiesbut he could not shake the idea of doing something in <strong>Patagonia</strong>.“There is just something about your own baby even though I was working25 hours a week then, <strong>and</strong> I am working 70 hours a week now, I am so muchhappier professionally,” he said. “And when you can marry profession <strong>and</strong>hobby like I did with social networking: I loved to stay in touch with people.How do you make a business out of it? I love nature. How do you make abusiness out of that?”Ultimately, his business skills, imagination, <strong>and</strong> love of <strong>Patagonia</strong> led him toa new venture, <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong>. “I’d say three years in, we are halfway there.”Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> <strong>and</strong> his wife Megan live with their three young children in an expansivehome complete with alpacas in the Oyster-Watcha section of Edgartown,a limited development subdivision with large <strong>conservation</strong> areas thatprovided some of the inspiration for his current project.<strong>Warren</strong> <strong>Adams</strong> <strong>and</strong> his three children in<strong>Patagonia</strong>.The <strong>Adams</strong> family spend several months in <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>and</strong> Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> travels there frequently.Capitalism is okayThe term <strong>conservation</strong>ist generally evokes an image of an individual in a plaid shirt, not a three-piece suit. Mr.<strong>Adams</strong> acknowledges that within some <strong>conservation</strong> groups, capitalism is a dirty word.“That is what h<strong>and</strong>cuffs them <strong>and</strong> initially made it harder for us to work with some organizations,” Mr. <strong>Adams</strong>said. “But three years in they have seen what we have been able to accomplish in terms of l<strong>and</strong> protected, whatwe are doing with the l<strong>and</strong> management <strong>and</strong> we are now very much collaborating with <strong>conservation</strong> groups.”

Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said they were not so much suspicious of his financial motives as they were of his concept <strong>and</strong> abilityto make it happen. “I think they thought these guys don’t know what they are doing. But that is what peoplesaid when I invented social networking 15 years ago. What is this, you don’t know technology,” he said. “AndI think there are lot of analogies with that <strong>and</strong> this. Because it’s a new model, first of all we had to convinceinvestors that we were going to make money.”Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said he sees a symbiotic relationship between capitalism <strong>and</strong> <strong>conservation</strong>. For example, his companycould partner with a <strong>conservation</strong> organization to conserve l<strong>and</strong> that might be financially out of reach werethey to try <strong>and</strong> go it alone.“We put in 50 cents on the dollar <strong>and</strong> they put in 50 cents on the dollar. They are able to protect twice as muchas they would have otherwise. We are able to protect <strong>and</strong> manage twice as much as we would have otherwise<strong>and</strong> we go in with an agreed set of covenants that we are thrilled with <strong>and</strong> they are thrilled with.”That could include an agreement that allows the company to generate profits through sustainable forestry or theplanting of native species in order to sell carbon offsets.Join, Protect, ExploreThe plan for <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> envisions nine profit centersof which four are up <strong>and</strong> running. The most visible isthe 100-member <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> Nature Reserve MembershipClub, which invites members <strong>and</strong> their gueststo “join, protect, <strong>and</strong> explore” more than 100,000 acresof some of the most undeveloped <strong>and</strong> scenic areas ofChile, while enjoying access to first-class amenities <strong>and</strong>accommodations.Fred Khedouri of Chilmark, an investor <strong>and</strong> club member, holds up atrout he caught during a visit.White water rafting, kayaking, fishing, horse back riding,hiking are among the activities offered. Mr. <strong>Adams</strong>likens it to the “legacy” clubs of the Adirondacks in the19th century.The membership price of $40,000 reflects the exclusivity. Almost half of the memberships have been sold. Clubmembers can sell their memberships <strong>and</strong> enjoy any profit the exclusivity might generate in the future.The price of a vacation stay is relatively reasonable when compared to similar vacation packages at far moredeveloped resorts. The daily rate for meals, lodging, beverages <strong>and</strong> guided activities for a couple is $300 perperson, $375 for guests, exclusive of airfare.The company is also selling carbon offsets. In the era of “cap-<strong>and</strong>-trade,” capping emissions <strong>and</strong> trading credits,there is money to be made.In the past, vast swaths of <strong>Patagonia</strong>’s forests were burned to create pastures for cows. Those pastures will bereplanted with trees <strong>and</strong> generate a commodity, carbon offsets, that can be sold around the world to companies<strong>and</strong> individuals.That is not a lot of hot air. The company recently signed a contract to sell carbon offsets to a major universityfor all their reunions. Attendees pay $20. <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> plants four trees <strong>and</strong> agrees to take care of them for 50years.Collectively, Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said, the university will one day be responsible for creating a forest with more than20,000 trees. A printing company recently bought 1,000 tons of carbon offsets for $15,000.Ultimately, he said the purchase of carbon offsets spurs companies to conserve if for no other reason than toreduce costs, he said.Patient strategy

The economic crisis that circled the world one year after <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> was launched, slowed but did not derailthe company’s plans. Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said his company has no debt <strong>and</strong> takes a long haul approach.“Our investors are patient capital,” he said. “They do this because they expect a competitive market return. Wetarget 15 percent or more of a return <strong>and</strong> so we sailed through the crisis in terms of operating our business. Raisingcapital was frozen for a while.”The company has raised $20 million from individual investors in Chile, the Unites States <strong>and</strong> around the worldof a $30 million target in the first phase. The amounts range from $125,000 to $2 million. Of the approximately45 investors, ten are seasonal or year-round Isl<strong>and</strong> residents.The business side supports the foundation. Investors must contribute going in <strong>and</strong> coming out. The currentbusiness plan would generate approximately $25 million for the foundation. “It is all very synergistic with thefor-profit side,” Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said.Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> stresses that the company is firmly rooted in Chile. He said a third of the club members <strong>and</strong> a thirdof the investors are Chilean as are two of the five principals.The investors share a confidence in Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> <strong>and</strong> the concept. “They see this as a chance for a good return oninvestment. It’s an asset-backed investment. There’s l<strong>and</strong> behind the value. It is not like it’s a software companythat does not really have a hard asset. And that helped us through the crisis because if you are worried aboutthings that disappear, l<strong>and</strong> doesn’t, <strong>and</strong> we’re buying it at $150 an acre <strong>and</strong> you can compare that with l<strong>and</strong> onMartha’s Vineyard.”The next step will be to raise $100 million at which point the company would be relying on institutional investors,Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> said. Further down the road, his dream is to go public.“The third <strong>and</strong> real dream is why don’twe IPO <strong>conservation</strong>?” he said. “Becauseif we can get $15 from someone buyinga share <strong>and</strong> you get millions of peoplethat want to buy one share of this becausewe’ve proven that it is going to havea nice return, whether it’s a dividendstream or stock going up, wouldn’t thatbe a great way to draw billions of dollarsinto <strong>conservation</strong>?”Melimoyu, one of the club’s properties, in a bay of the Gulf of Corcovado, featuresdiverse marine life.For now, Mr. <strong>Adams</strong> is focused on thecurrent plan but with his eyes on the horizon.“My specialty is to keep focused butdream big. You always have to be thinkingnext, but blocking <strong>and</strong> tacking to getthe first part right.”Right personThat first part relies on investors who believe that the company will be able to add value to the l<strong>and</strong> that protectstheir investment <strong>and</strong> makes it grow. Fred Khedouri of Chilmark, an investment banker, is one of those investors.In a telephone call from London, Engl<strong>and</strong> where he is working, Mr. Khedouri said he approached Mr. <strong>Adams</strong>.He points to Chilmark as an example of how value can be developed. Real estate in Chilmark is more valuableon a relative basis than the rest of the Isl<strong>and</strong> he said because it has relatively strict zoning <strong>and</strong> large lot sizes.In the case of <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong>, protecting the majority of the l<strong>and</strong> makes the rest more valuable. “It is not by anymeans a traditional approach to development, which is to extract the greatest possible profit,” Mr. Khedourisaid. “That is not happening, <strong>and</strong> all the investors I think underst<strong>and</strong> that is not happening <strong>and</strong> they are all fine

with it because they don’t want to be extracting the most value, because then the <strong>conservation</strong> part would not beas large as it might be.“And that is why to me it is quite appealing, <strong>and</strong> I know some of the others investors have the same view. It is infact a good balance.”Mr. Khedouri <strong>and</strong> his wife visited two of the club properties last February with two friends. “It was terrific,” hesaid.“I seem to spend my life being places where a lot of times I wish I had been there 30 years ago, or I was there30 years ago, <strong>and</strong> it is no longer the same. We certainly have that experience (on the Vineyard).” <strong>Patagonia</strong> isthat place 30 years ago.“It just struck me as a really good idea. And something that should be encouraged, <strong>and</strong> I thought that <strong>Warren</strong>was the kind of person whose involvement would be making it a success.”Mr. Khedouri said he contributes to <strong>conservation</strong> causes. This he views as an investment.<strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> boasts an impressive list of board members <strong>and</strong> advisors that includes academic <strong>and</strong> <strong>conservation</strong>leaders. Mr. Khedouri said board members only provide one indicator of an organization’s merit.“What really matters is who is really involved,” he said. “With <strong>Warren</strong>, he really is involved. You are getting<strong>Warren</strong>, <strong>and</strong> to me that is worth more.”The <strong>Patagonia</strong> <strong>Sur</strong> properties are in the south of Chile.All Photography Courtesy of <strong>Warren</strong> <strong>Adams</strong>.