Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

Summer 2007: Volume 28, Number 3 - Missouri Prairie Foundation

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

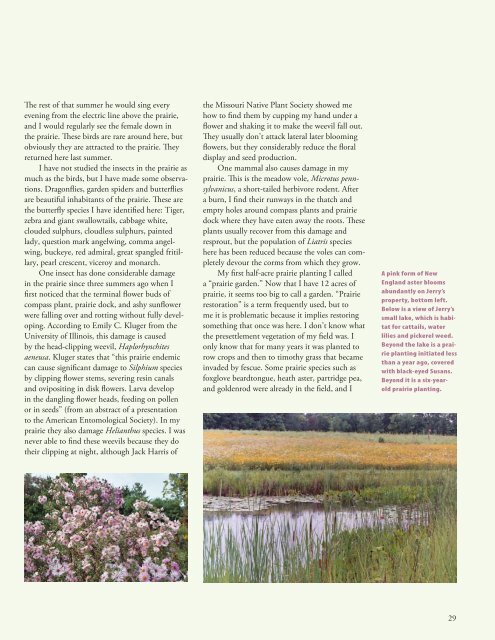

The rest of that summer he would sing everyevening from the electric line above the prairie,and I would regularly see the female down inthe prairie. These birds are rare around here, butobviously they are attracted to the prairie. Theyreturned here last summer.I have not studied the insects in the prairie asmuch as the birds, but I have made some observations.Dragonflies, garden spiders and butterfliesare beautiful inhabitants of the prairie. These arethe butterfly species I have identified here: Tiger,zebra and giant swallowtails, cabbage white,clouded sulphurs, cloudless sulphurs, paintedlady, question mark angelwing, comma angelwing,buckeye, red admiral, great spangled fritillary,pearl crescent, viceroy and monarch.One insect has done considerable damagein the prairie since three summers ago when Ifirst noticed that the terminal flower buds ofcompass plant, prairie dock, and ashy sunflowerwere falling over and rotting without fully developing.According to Emily C. Kluger from theUniversity of Illinois, this damage is causedby the head-clipping weevil, Haplorhynchitesaeneusa. Kluger states that “this prairie endemiccan cause significant damage to Silphium speciesby clipping flower stems, severing resin canalsand ovipositing in disk flowers. Larva developin the dangling flower heads, feeding on pollenor in seeds” (from an abstract of a presentationto the American Entomological Society). In myprairie they also damage Helianthus species. I wasnever able to find these weevils because they dotheir clipping at night, although Jack Harris ofthe <strong>Missouri</strong> Native Plant Society showed mehow to find them by cupping my hand under aflower and shaking it to make the weevil fall out.They usually don’t attack lateral later bloomingflowers, but they considerably reduce the floraldisplay and seed production.One mammal also causes damage in myprairie. This is the meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus,a short-tailed herbivore rodent. Aftera burn, I find their runways in the thatch andempty holes around compass plants and prairiedock where they have eaten away the roots. Theseplants usually recover from this damage andresprout, but the population of Liatris specieshere has been reduced because the voles can completelydevour the corms from which they grow.My first half-acre prairie planting I calleda “prairie garden.” Now that I have 12 acres ofprairie, it seems too big to call a garden. “<strong>Prairie</strong>restoration” is a term frequently used, but tome it is problematic because it implies restoringsomething that once was here. I don’t know whatthe presettlement vegetation of my field was. Ionly know that for many years it was planted torow crops and then to timothy grass that becameinvaded by fescue. Some prairie species such asfoxglove beardtongue, heath aster, partridge pea,and goldenrod were already in the field, and IA pink form of NewEngland aster bloomsabundantly on Jerry’sproperty, bottom left.Below is a view of Jerry’ssmall lake, which is habitatfor cattails, waterlilies and pickerel weed.Beyond the lake is a prairieplanting initiated lessthan a year ago, coveredwith black-eyed Susans.Beyond it is a six-yearoldprairie planting.29