JULy/AUGUST 1980, No. 23, $3.00 Making ... - MetosExpo - Free

JULy/AUGUST 1980, No. 23, $3.00 Making ... - MetosExpo - Free

JULy/AUGUST 1980, No. 23, $3.00 Making ... - MetosExpo - Free

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

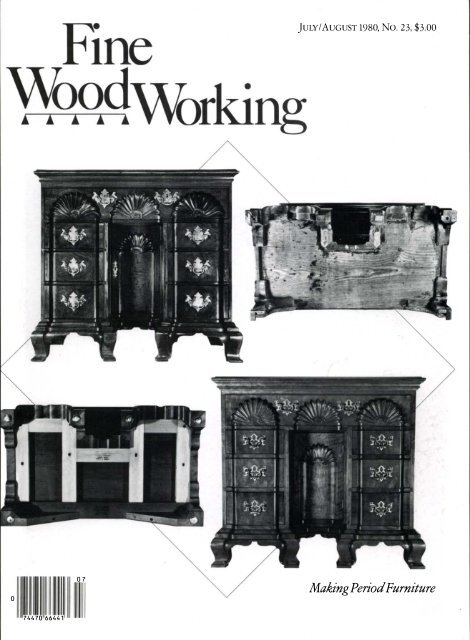

<strong>JULy</strong>/<strong>AUGUST</strong> <strong>1980</strong>, <strong>No</strong>. <strong>23</strong>, <strong>$3.00</strong>o744706644107<strong>Making</strong> Period Furniture

The right info rmationmakes all the difference.Here are three remarkable technical' volumes that approach their shop tasks with the samethoroughness and expertise as Fine Woodworking, but with even more depth. If you want tomake an unusual joint, work green wood or learn a special technique like cutting threads inwood, you'll find these books invaluable._ Joinery:ToolsandTec nlqut"lcN\I to . otmake the unportaA masterwooctworkts-Ifl""""' cran pletestep-bV·stepTage Frid Teaches WoodworkingJoinery: Tools and Techniquesby Tage FridThe dean of American woodworkers-and Fine Woodworking senioreditor-tells what he's learned in 50 years of cabinetmaking. His experiencecan teach you many things in this landmark step-by-stepvolume. 811z"x 11", 224 pages, 900 photographs, 365 drawings.$16 cloth, postpaidMake a Chair from a Tree:An lntrocluction to WorkingGreen Woodby John D. Alexander, Jr.What you need to know in taking wood directly from the tree andshaping it into a chair before it has a chance to dry. A nearly lost artbrought vividly back to life. 9"x9", 128 pages, 175 photographs, 75drawings.$8 paper, postpaidFine\qoQWorking. 180 ods tools and materials forp:ages o f meth , ed the f firstk select romseven iSSues 0 .weTECHNIQUES 11ser ious w ood" fo:.e r s Z,\, o od w orking magazineFine Woodworking Techniques 1A collection of all 50 technical articles from the first seven issues ofFine Woodworking magazine. It's important but hard-to-come-by information,and we want to make sure it stays in the literature. 9"x 12",192 pages, 394 photographs, 180 drawings, index. $15 cloth, postpaidEach of these books is written for the serious woodworker. To order,use the convenient order form bound into the magazine, or write to:11lnmron H:ess 52 Church Hill Road, Box 355, Newtown, CT 06470© <strong>1980</strong> The Taunton Press

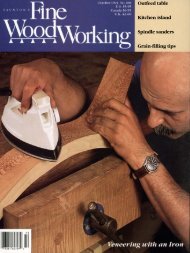

EditorAISociote EditorAllistant EditorCopy EditorEditorial AISistantSenior EditorContnouting EditonCOnlulting EditorlMethodl 0/ WorkCo"elpondentl/ EnglandWeIt CoaltNew EnglandWl1Jhington, D.C.John KelseyRick MastelliJohn LivelyRuth DobsevageMaty Pringle BlaylockTage FridR. Bruce HoadleySimon WacrsGeorge FrankA. W. MarlowLelon TraylorJim RicheyRoger HolmesJohn MakepeaceAlan MarksRosanne SomelSOnRichard StarrStanley N. WellbornFine•WqqQWorJULY / <strong>AUGUST</strong> <strong>1980</strong>, NUMBER <strong>23</strong>Art DirectorAllociote Art DirectorII/ultratorArt AmitantlProduction ManagerAmitant ManagerDarkroomTypelettingMarketing DirectorPromotion ManagerSaleI/Oper. CoordSalel Dept. SecretaryAdvertiling SalelCoordAdvertising AmitantAdvertising COnlultantSublcnption ManagerMat/room ManagerAccounting ManagerSecretary to the PubltiherAlJOciate PublisherPublisherRoger BarnesDeborah FillionBetsy Levine MastelliLee HochgrafKaren PeaseJoAnn MuirCynthia LeeBarbara HannahMary Eileen McCarthyJack F. FriedmanDonald FleetJohn M. GrudzienHenrietta BuchVivian DormanCarole WeckesserGranville M. FillmoreCarole E. AndoGloria CaISOnDorothy DreherKathy Jean FullerMarie JohnsonCathy KachNancy SchochKathy SpringerViney MerrillRobert BruschiIrene ArfarasMadeline ColbyElaine YaminLois BeckJanice A. RomanPaul RomanCover: On first glance Robert Emmett's reproductionof a Newport kneehole bureaulooks like the c. 1780 orig inal, which is theone on top. The views /rom below, however,hint at how differently they are made.Emmett believes tbe old designs can't beimproved, whereas the old constructionsmust be-here he shows how he proportionsdovetails to make a stron g er drawer.More about these two pieces and about howother reproduction cabinetmakers see thequestion of whether to improve or to reproduceprecisely, on p. 32. (Newport bureaucourtesy Yale University Art Gallery, Garvancollection; photo Joseph Kugielsky.)DEPAR TMENTS4 Letters10 Methods of Work18 Questions & Answers24 Books26 Events28 Adventures in Woodworking31 ConnectionsARTIaES32 In Search of Period Furniture Makers by Rick MastelliWhat they do about what the 'old guys' did41 Plans: Newport-style and Boston-style Blockfronts45 The Blockfront by Margaretta M. LovellIts development in Boston, Newport and Connecticut47 Building Blockfronts by E. F. SchultzImproving traditional constructions50 Variations in 18th-Century Casework' by Wallace B. GuslerSome 'old masters' built better than others53 Post-and-Panel Chests byJim RicheyA 19th-century design55 The Frame and Panel by Ian j. KirbyAncient system still offers infinite possibilities59 The Legacy of Harry <strong>No</strong>hrDurable, delicate bowls of native hardwoods60 Turning Thin and Finishing with Epoxy by David Lory61 Tool Rests and Turning Tactics by Bob Gdson62 The Carousel Horse by Roger E. SchroederHollow carcase makes a sturdy beast65 An Abrasive Planer by Michael Horwitz and Michael RancourtAutomatic feed and rigid bed offer exceptional accuracy68 A Disc Sander by Donald C. Bjorkman70 Turning Thin Spindles by Mike DarlowLacemaker's bobbins demand speed and precision72 Carbide-Tipped Circular Saws by Simon WattsAlloy's hardness is its weakness76 Hardwood Plywood by Tage FndModern 'glued-up stuff saves work, money and wood79 French Fitting by John Lively<strong>Making</strong> the presentation case presentable82 The Woodcraft ScenePrescote's London Show by Roger Holmes84 The <strong>No</strong>rthwest WoodsFine Woodworking (ISSNThe Taunton Press, 10e.. Ncwrown. CT 06470, Telephone (203) 426·8171. Mcond-class postage paid at Newtown. CT0361-34)3) is published bimonthly. Janu"l" March, May, July, Septemb

Letters (continued)sharp corners, I cut one end of the spline at a 450 angle and,staning at the middle of the back of the seat, drive the splinedown. If the seat has corners I miter to match the corners. Ilearned this method from a gentleman who had used it forover 20 years. He claims he's never had a seat come back becauseof the installation. I've used it for the past six years andhaven't had one returned yet.Also, many of the press cane seats we see in our shop havebeen glued down. I pour warm vinegar in the groove to softenthe glue and then, using a screwdriver I've filed down to fitthe groove, I can pry the old spline and cane out. Clean thegroove well. Test the vinegar on the finish before using it inthe groove. -Scott McDiarmid, Charlottesvzlle, Va.I recently spent a frustrating day trying to duplicate thedowelmaker described by Trevor Robinson (F WW #8,Fall '77). Although I couldn't make it work, I discovered afar simpler and easier technique with which I turn out dowelsof any size. Proceed as follows: (1) Bore a hole the size of thedesired dowel through a block of hardwood about 2 in. thick.(2) Enlarge one end of the hole conically with a reamer, lathe,rasp, etc. The shape and finish are not imponant because thedowel blank will not touch the core. (3) Slice the top off theblock with a saw or plane until the top of the hole where itjoins the core just shows. (4) Lay a plane blade or similarsharp blade over the hole with the cutting edge just forwardof the conjunction of the hole with the cone, bevel up, andclamp the blade in place. (5) Whittle down the two ends of asquared dowel blank, chuck one end in an electric drill, andrun the blank at high RPM but slow forward speed into thecutter. A bit of experimentation should result in perfectr------------------,FREE SANDING BELTSDIRECT FROM THEMANUFACTURER(Manufactured at 642 <strong>No</strong>rth Eighth Street, Reading, Pa.)WIth your order eX one dozen or more belts. we will send you six FREE. AlI belts are aluminumoxide first quality. Our electronic presses make smooth bump-free splices.Oleck your size and how many dozen.We will ship assorted grits unlessotherwise specifiedD l"x42" -$ 9.75/doz.D l"x44" - 9.75/doz.D 3" x 18" - 10.75/doz.D 3"x21" - 1l.25/doz.D 3" x <strong>23</strong>3/4" - 11.75/doz.D3"x24" - 11.75/doz.D 3"x27" - 12.25/doz.D 4" x 213/." - 13.75/dOz.D 4" x 24" 14.25/doz.D 4" x 36" 17.95/doz.D 6" x 48" - 19.95/1/2 doz.9" X 11" Paper Sheets(100 sheets per package)D 40-0 -$25/pkg.D 50-0 - 22/pkg.D 60-0 - 20/pkg.D 80-0 - 17/pkg.D lOO-C - 15/pkg.D 120-C - 15/pkg.D 15O-C - 15/pkg.D 6OO-A- 19/pkg.(3OtherFREE)size belts on requestPrompt delivery from stock.MONEY-BACK G

Whenyouwork=youneedThe Woodworkers'_ ,:---::::,, "" _::-:: _:--::-___.We carry the fin-Store catalog . ".:::-""-=7:-':--:_::-7'I.est selection of veneers, hardwoods,inlays, mouldings, specialty hardcarvingtools, finishing materials,caning supplies,and an informativeselection of booksand plans for everyproject.This year we arecelebrating 25years of serviceto over100,000satisfiedcustomers.They havefound areliablesource ofwoodworkingsuppliesalong with the speed and service ofcatalog mail order.And when it comesto catalogs, our all 25new catalog/manual is the mostinformative and-yearseasyto understand supply bookavailable. Throughout its 112 pagesyou'll find colorful photographsand illustrations showing over 3,000carefullychosen productswith easyto understandhow-to information.To receiveyour copy of$1.00 to:the catalog/manual, sendDept. 816S-m __ nrJiTheGWood workers' St ore21801 Industrial BoulevardRogers, Mi nnesota 55374IPRESIDENT'SSUMMER SALEIt's a 10" table sawIt's a 34" lat hee It's a horizontalboring machinee It's a 16V,' variablespeed drill presselt'saI2"discsanderAll in 1 tool.Here's a wonderful opportunityfor you to get America'smost-wanted power tool at thebiggest savings of the year.As President of Shopsmith, Inc., I cordially invite you to take advantageof our special once-a-year President's Summer Sale. Mail the couponbelow and you're entitled to the biggest savings of the year, $100.00toward a purchase of the Shopsmith MARK V -the 5-in-1 power toolthat's a complete home workshop!You are probably already familiar with the MARK V from our tv and-at the biggest savings of themagazine ads, our demonstrations, or perhaps from someone you knowwho has one. ow, you can own one yourselfyear! You'll find out why thousands of satisfied customers call it "the toolto start with, the system you grow with."It's the woodworking system that's rightfor you whether you're a beginner oran expert.If you're already on our mailing list,you'll be receiving all the information onthis spectacular sale soon. But if you'renot, be sure you mail this coupon today!A savings of $100.00 is waiting for you!Sale ends August 31, <strong>1980</strong>. Mail thecoupon today! You're under no obligation. PRESIDENTSHOPSMITH, INC.----------.---Mail to:e) Shopsmith Inc.IThe Woodworking CompanyDept. 2532750 Center Drive, Vandalia, Ohio 45377o YES. please send me more information about the Shopsmith MARK V and tell mehow I can enjoy the best savings of the year with this coupon during the once-a-yearPresident's Summer Sale' I understand I am under no obligation.o I have inquired about the Shopsmith MARK V before, but want to make sure Ireceive John's $100.00 savings offer.NameAddressI City State ZiP .Ja..------______ _I7

Letters (continued)(which can be covered when the sliding feature isn't wanted)and a sturdy, accurate rip guide. I found it for $200, andagain I had to rebuild the blade guides. It's too much saw formost of the bandsawing I do, and the table doesn't tilt, butfor resawing it works fine. There are many of these old sawsaround because thousands of small butcher shops have closedin the past 10 years. I also bought a meat-cutting blade, andfind it works fine for its original purpose, too.- George Pzlling, Springvtlle, CaltfLike Ted Sittler (FWW #2 1, March 'SO, p. 6) , the first bandsaw I ever owned was an IS-in. model I built from the Gilliomkit. I had some of the same problems . .. and I have gained agood deal of experience since, so here are my suggestions.Gilliom's design can be beefed up a bit in several ways. Iadded an extra 2x4 to the left support column and used glueblocks in strategic places throughout the body of the saw. Ialso used nails and glue, and extra screws and bolts. I builtmy saw from lk-in. construction plywood and yellow pine. IfIwere to build another, I would use rock maple and veneercorebirch plywood. Perhaps some angle iron, also.There are several possible causes for the blade to belly outon thicker cuts. The main reason I found was that the upperframe, being wood, did not have the necessary rigidity.Therefore the blade could not maintain its tension. My solutionwas to add a detachable support column at the right ofthe blade-from the upper frame to the lower body of themachine. For most resawing it did not get in the way, and forcurve and panel cutting it could be removed. I had to modifythe table, however, making a part of the right-hand sectionremovable to allow for the extra piece. Most important, I hadSdo dozensof jobs betterwith amazing ForedomMiniature Power Tools• Hangup and bench • Variable speedsmodels• Hundreds of cutters,• Powerful motorpOints. abrasives,• Rugged flexible shaft special toolsforENGRAVING---....,SANDING ••••••••••••••••••••••••••O!!: ERDRllll1POLISHINGGRINDINGROUTINGDEBURRING BUFFING • SAWINGand many moreCraftsmen, model makers, hobbyistsknow Fored om's pr ofessional qualityproduces professional results. Lightweight,easy-to-hold handpieces Idealfor fast, super-precise drilling, carving,sanding, grinding, buffing and dozens ofother operations on wood, metals, plastics,ceramics, minerals.See your dealer or send now ...Special offer on machines, hand pieces,speed controls, tools described in FREECatalog File <strong>No</strong>. 280A2.\FlFOREDOM®• _ THE Bethel, FOFlEDOM CT 06801 ELECTRIC 203-792-8622 COMPANYto add a strong spring to the blade-tensioning mechanism tokeep the blade from breaking. An old automotive valvespring worked very nicely ....If the saw is built fairly well, the speed can safely be increased.I ran mine at 3,600 blade feet per minute instead ofthe 2,000 specified. Three thousand would be optimum andprobably easier on the wood frame, especially if the tires or. wheels haven't been dressed true. I simply substituted aslightly smaller motor pulley . ...Resawing takes a bit of patience and skill. Use a slow, firm,even feed speed. Let the machine do the work. Make sure thefence and the blade guides are adjusted properly and that thetires are in good shape and clean. Use enough tension. Itdoesn't go as fast as you might think, but it's still faster thana lO-in. table saw and infinitely less nerve-wracking.-James L. Wheeler, Houston, Tex.William Woodcock mentioned using propane to reduce thegelling of polyurethane varnish (Letters, FWW #22, May 'SO,p. 4). I have an easier technique. I simply cut a circle of SaranWrap the size of the inside of the can, then spread the cutcircle atop the remaining varnish and reset the can lid.-Henry Turner, Sterling, Colo.Propane gas is highly flammable in the presence of air. Even aspark, as might occur when prying open a can with a screwdriver,might set off an explosion. Propane is best left totorches and gas stoves. -Michael McCann, New York, N. Y.We very much appreciated the recent article about Japanesesaws (F WW #2 1, March 'SO). However, the editor's note im-•••••••••••••••••••••••••••You r best source for •a choice selection =of the very finest I•furniture hardware!I THE DECORATIVEJI HARDWARE STUDIO160 KING STREET, CHAPPAOUA, NEW YORK 10514Call (914) <strong>23</strong>8-5251 orwri1e for$2.00 CATALOG. Refund with first orderHINGES. SABOTS. CHUTES. CONSOLESKNOBS. PULLS. DROP RINGS. GALLERIESROSETTES. MOULDINGS. CAMPAIGNCABINET LOCKS AND MORE - HUNDREDS OFSTYLES IN SOLID BRASS, SPECIALTY FINISHES,LUCITE, LIMOGES PORCELAINDOMESTIC & FOREIGNHARDWOODSQuality stock forCabinet WorkMost all sizes from1" up to 4" in thicknessHARDWOODSASH -BASSWOODBIRCH-BUTTERNUTCHERRY -CHESTNUTEBONY -MAPLE-OAKPOPLAR-ROSEWOODTEAK -WALNUTAlso hardwood plywoodsSOFTWOODSSUGAR PINE-CYPRESSCEDAR-SPRUCEDOUGLAS FIR etc.MAURICE L. CONDON CO., INC.White248Plains,Ferris Avenue914-946-4111.y, 10603Open Saturdays 8 AM until 2 PM

Letters (continued)plies that the fIrms mentioned all offer the same Japanese sawat different prices. As you are aware, there is a wide range inprices of Japanese tools. We currently offer ryoba saws rangingin price from $13.50 to $48.10. As an indicator of quality,the following note was received from Thomas Hucker, a studentin the program in artisanry at Boston University: "I metsome Japanese carpenters doing restoration work in the BostonMuseum a few weeks ago, and with the help of an interpreter,we showed them your tools and their response was notonly were they very good tools, but the same brand that theythemselves use."-Fred Damsen, PresidentWoodlinelThe Japan Woodworker1004 Central Ave., Alameda, Calt! 94501Re T. R. Warbey's sander (FWW #21, March '80, p. 50), thefollowing suggestions: Replace the pillow blocks with selfaligningball bearings. Replace the hex-nuts of the left-handside hold-down bolts with wing nuts, and replace, if possible,the wooden drum with a steelone that has the same outsidediameter as the inside diameterofstandard PVC 6-in. gasor drainage or sewer pipe withwalls about Y4 in. thick. Cut \\ 1\\,three or four slots about Yz. in.· ... ·:-ii·.-.. _iljj:.1••• 'long and % in. wide in the right-hand end of the tube, sothey will fIt over keys mounted on the drum, for example,two wood screws side by side in a wooden drum or some Y4-in.key bar welded or bolted to a steel drum. Various sleeves ofPVC tube can be kept with different grits glued to them.I might add that I don't use wood in machine tools. Thepillow blocks in the low-tech thickness sander are presumablyfIxed with wood screws in end grain. As the drum is notdynamically balanced, sooner or later Warbey will have aclose encounter of the unpleasant kind with it. The cost of asmall electric welder and the little effort necessary to acquiresome skills are quickly repaid by the tools and structures thatcan be made for a song out of scrap iron and discardedmachine partS.-H. 1. Gosses, Leiden, The NetherlandsIn reply to Peter Kemmer's letter (F WW #20, Jan. '80) onhand work vs. machine work, I would like to make the followingobservations. I am a clinical psychologist and a sometimewoodworker bent on rapidly increasing both skills. I do notbelieve it is possible to become too philosophical about ourcrafts, nor do I believe that sanitizing emotionality out of thepractice of our crafts will improve the product.First, there is the fact that most of our time is spent in exercisingthe process. If the process is subordinated to the product,we run the danger of becoming bored with the activitiesthat occupy our time. The product occupies no time at all;only the process consumes time. Boredom will most certainlylead to a degradation of the quality of the product, and thatwill be noticed by the consumer. The issue isn't whether weshould work by hand or by machine. Do whatever turns youon. But to attempt to desensitize yourselves to any of thepleasures involved in exercising our crafts will, as surely asnight follows day, produce pieces that lack sensitivity, graceand craftsmanship ....In short, the beauty that Kemmer seeks is the end result ofa process. Ignoring that process cannot but detract from theproduct.-Harry]. Coffey, Lewisburg, W. Va.tau.cA IIWood Finishes and related items. Lacquers,sealers, fillers, strippers, veneer,reproduction hardware, clock movements.Many hard to find items.Send $1.25 for catalog. Estab. 1942.Shipped in Continental United States only.GASTON WOODDept.FINISHES,FWINC.3630 E. 10th St., P.O. Box 1246Bloomington, Indiana 47402II01you work in hardwood. this bit is one tool youmust have! Unlike other bits. the Forstner isguided by its circular rim instead the center.Bore any arc or circle and you leave a truepolished surface. Guide it in any direction, it cutssmoothly through cross-grain or knots!$11.95AVAILABLE IN THESE SIZESPRICE EA.I". 12.95 13.951/4".5/16".3/8".7116".1/2"9/16". 5/8",17/16".314".13116"I &13/16".718".15/16". 1·1/16"Add 51.50 Postage HandlingFRANK Impo,.,.". MITTERMEIER. 01 Quail' y Tool. INC. Sinc. (Eat. 1936111311)Write lor our FREECATALOG3577 E. Tremont Bronll N.Y.POWERMATIC8" JOINTERThe Model 60 8" Jointer is one ofthe many new Powermatics now instock. We also offer the completeline of Rockwell and PowermaticShaper Cutters (including Carbide),as well as Carborundum Abrasives."!UOO DS::a:O:F'S:F'ECJ:ALTJ:ESP.O. Box 1013East Middlebury, Vt. 05740802-388-7969FINE HAND TOOLSINCA POWER TOOLSEXOTIC HARDWOODSWOODCRAFT CLASSES• BOOKS & MAGAZIN ES"WOODCRAFTER'SDREAM STORE!"1#1-Sunset Magazinet::HE CUCCING EDGEBEVERLY HILLS. CALIFORNIA295 South Robe rtson Boulevardlbetween Wilshire & Olympic)213/652-6133 HOURS: Mon.·Sat. 1Oam-6pmBERKELEY. CALIFORNIA1 836 Fourth Street 415/548-6011HOURS: Mon.·Sat. 10ampmMILL YOUR WOOD WHERE IT FALLSFour precision built, lightweight models singleor double chain saw engines. Capable of millinglogs on site up to 50" wide, 3/8" to 15" thick andany length.Described in: Popular Science. June. 1978.James Krenov .. Fine Art of Cabinet <strong>Making</strong>.FOR FREE BROCHURE AND PRICES WRITE TO: SPERBER TOOL WORKS INC.BOX 1224 • WEST CALDWELL. NEW JERSEY. 07006C201l744-BllO9

Methods of WorkCut-downlid supportsCUSTOM MOULDINGSFor Every PurposeSpecializing in Victorian TypesGrindingwheelAdjustable tool restHere is an adjustable bench-grinder tool rest that's accurate,easy to use and cheap to build. Cut a 1 Ifl-in. thick pine hingeblockat the angles shown and mount it to the base withscrews from underneath. Cut down two Stanley 10-in. lidsupports to make the table-adjusting hardware. Drill out thecenter rivets and replace with screws into the 1x1 hardwoodblock. Pin the %-in. threaded rod in a mortise in the pinehinge-block. <strong>No</strong>w mount the plywood or Formica-covered,composition-board table as close to the grinding wheel as possible.Recess the hinge into the bottom of the table ifnecessary.-Mike Pern'n, Knoxvtlle, Te nn.Sanding block for lathe workFor years my woodworking students invariably burned theirfingers sanding bowls and other lathe work. Then I hit uponthe solution-sanding blocks cut from sheets of lJ2-in. thickrubbing felt. The felt sanding block shapes itself to shallowcurves and can be deliberately shaped to match any contourof a compound curve.Rubbing felt is available in I-ft. squares from H. Behlen &Bros. (Box 698, Amsterdam , N.Y. 12110) and other suppliers.A similar material, used for typewriter cushions, isavailable from office-machine suppliers. Cut the pad with arazor knife and rule. One block lasts indefinitely.-Russell Anderson, To rrington, Conn.<strong>Making</strong> little wooden ballsFaced with having to reproduce a number of Ih-in. diameterwooden balls (to replace missing ornamentation on an oldfireplace) , I discovered a virtually painless procedure using alarge belt sander. Build a box frame, open on the bottom,and clamp it to the stationary part of the sander so it sits justoff the belt. For Ifl-in. diameter balls, cut Ifl-in. cubes and tossthem in the box frame. Put a cover on the box (Plexiglas isbest) and turn on the sander. The sanding belt will throw thecubes around in the frame like dice on a game table, knockingoff their corners and edges until they're perfect spheres.If the cubes don't tumble about but rather line up neatlyagainst the far wall of the frame, glue a wedge there. If thisdoesn't work, you could vary the number of cubes, presandFurniture - MantelBeds/Coves - BaseChair Rails - Door & WindowCasings - Quarter & Half RoundsCherry -Oak - MapleBasswood - Birch - PoplarFor Information WriteRESTORATION BUILDERS, INC.189 UNION STREET, MONTCLAIR, N.J. 07042201-744-3496We also manufacture hand hewn beamsand wainscotting"MUsicalGJns'llbodSuppliesccessoriesOf The CJiinest Quality8Jew Catalogue For 1979Gurian GuitarsBox 595West Swanzey, N.H. 03469Catalogue $1.00Surprising How Much HandSanding can be Saved with aSAND-O-FLEX®CONTOUR SANDER14,000 "Sanding Fingers"per minute, eliminatestedious hand sanding.brushesFirm cushioningforce slashedgentlysive stri ps overabrashape and will notanyfineharmdetailor gougeor veneers.J iCompton, California 90224r R h:d:: : i ! Io SANDE R KIT<strong>No</strong>.4S"S brush 6"x1" wheel and 3abra· , drill csf i :f;u3::ra;1 $2495 FW I carrying and storage case. Includes postage & handling. .,-------------'BUTTERNUT, WALNUT,PINE,ROS EWOOD,CHERRY, BUCKEYE and about adozen other woods, in boards, slabs andfreeform cut ovals. Pieces up to 6" thick,3' wide and 16' long in some species. Wespecialize in coffee tables, benches, bars,carving stock, clock ovals and movements,accurately cut for you to finish. We sell bymail an d from our fantastic wood"museum," 9-5 except Sunday. Send $.25for brochure.WEIRD WOOD, Box 190FWChester, Vt. 05143, 802-875-3535Delmhorst ModeWood MoistureDetectorSOLID STATECOMPACTLIGHT WEIGHTDIRECT READING6% TO 30% WOODMOISTURE RANGEThis is an excellent instrument for thecraftsman. Moisture content is read immediatelyand directly on the meter dial.This is of great assistance in the dryingand/or purchasing of lumber as well as incontrolling wood moisture content at anystep of production. A complete line of electrodesincreases the accuracy and usefulnessof the instrument.Delmhorst Instrument Company____ 11201 /334-2557 ____ _908 Cedar Street, Boonton. New Jersey 0700510

Methods of Work (continued)Clamp frameto sanderjust above beltrtlllJ'III'lV"

Methods of Work (continued)ial by cutting crossgrain, repeat passes along the grain, thencarve out the corners by hand. Finish the surface by scrapingand sanding. -Pendleton To mpkins, San Mateo, Calt!Deep-throat clampIf you need a deep-throat clamp and none is available, substitutea conventional C-clamp and two blocks of wood arrangedas in the sketch below. Though direct pressure is less thanwith expensive specialty clamps, the system works fine forgluing inlays, guitar bridges and other simple joints.-Bob Osbahr, Tucson, Anz.Tighten clampsto applyeven pressureacross boardClamping wide boardsIn bookcase construction and other large-carcase work, It ISoften necessary to join wide boards in an H. Without specialclamps, it is difficult to achieve the necessary clampingpressure. This simple crowned caul, used with ordinary barclamps, solves the problem.To make the caul select a I-in. thick, 2-in. wide block aslong as your lumber is wide. Plane a crown on one edge, leavingthe center high and each end about a degree lower. <strong>No</strong>wlay the caul, crown edge down, across the width of the boardto be clamped. As you apply pressure to each end with barclamps, the end-gaps will close, resulting in even pressureacross the joint.-David Shaffer, Stlvercliff, Colo.Square cutsMost table-saw and radial-arm-saw blades that I've workedwith have a tendency to climb and squirm when crosscutting.The result is an out-of-square cut. I've found, quite by accident,that if the crosscut is very thin, say one half the kerf, thesaw cuts amazingly true. This approach does require that youClamp complicated or simple shapes withthis durable Ingenious tensioning tool.Starter kit contains hi-test strapping,buckles, tool and Instructlon-,..usable.Order <strong>No</strong>w!•$15 95 PlusDealer Mass. Residents Inquiries51.50 add WelcomedPOSTAGE 5% lax.HOT TooLs.SENDInc. 9 HawkesTODAYStreet.FORMarblehead,BROCHUREMass. 01945DO-ITYOURSELFFINE GRANDFATHER CLOCK KITSSTARTING UNDER$225(including movementand dial)Factory directprices• Heirloom quality• Solid %" hardwoods:black walnut,cherry, mahogany,oakEasy to assemble,parts pre-cut• Solid brass WestGerman chimingmovementsMoney backguarantee• Prompt shipmentMASTER CHARGE and BANKAMERICARDNISAACCEPTEDWrite for FREE color catalogEMPEROR®CLOCK COMPANYWORLD'S LARGEST MANUFACTUREROF GRANDFATHER CLOCKSDept. 540 Emperor Industrial ParkFairhope, Alabama 36532THE WISNER PLANEEdge Trimming BlockAn improvod Stanley #95 with fonco and shoar bladofor preciso square cutting. Hoirloom-qualityBronze-$83.50 plus $2.50 shil'ping. This tool ishandcrafted to an extraordinanly hlgh standard inlimited production. Send for details to:Wisner Tools, 259 Whaley St., <strong>Free</strong>port, NY 11520r----------------I &HARDWOODLUMBER CATALOGVENEERSI 98 Varietiesworld's rarest veneers and___lumbel' at reasonable prices. Simplifiedveneering Instructions plus full colorwood selector Included. Send for freee : o,t:.as C Ve5 !70 rry!I BOB MORGAN WOOD, Dept. F04K24l JPROFESSIONAL TURNING roOLSFittings and accessoriesSend one dollar for catalogPETER CHILDThe Old Hyde, Little Yeldham,Halstead, Essex, England.NOW' Brand yoL!r own namepermanently on wood and leatherhandcrafts' Simple to use. LongBrands full name. Guaranteed.lasting. U/L approved electric handle.FREE ILLUSTRATEDLITERATURE!I12

THE HISTORY OF CUT NAILSIN AMERICAIl' lit'll,,! ,! lth,1 ,If 1 , 1 T t,' J T \'1 1'1!11 11111-,.'_" ,,,n.l."7:",""I"" "o'U lI t'" n ••-.. t - ' : ' r J ._:'.. JCUT NAIL KITA unique collection of Tremont OldFashioned nails containing 20 varietiesand a history of Cut Nail <strong>Making</strong> inAmerica. Cut nails areideal for most nailingprojects. Nail headpatterns for decorativeSAMPLESETeffects are shown in $3.50 ppd.our Sample Set and U. S. funds onlycatalog.Mass. residents add 5 % Sales TaxSEND FOR FREE CATALOGTREMONT NAIL CO.P.O. Box III Dept. FW60Wareham, Mass. 02571AMERIC(S 7 BESTPOWER TOOL1B6" tillarbor sawcrosscuts. rips, mitres. cuts compoundangles. dadoes, coves, moldings,Less blade. motor. Rip fencefor easy alignment $6.50 addt Sailbearing model $9. 75 add'i. Takes1/3 h.p. motor or larger, standard a : s , fa t c a 7t'.!: 544.60SPrecision heavy duty sander includesa 4" x 36" sanding belt.Uses 1/3 h.p. or larger motor.V-pulley drive and multi-purposedrive spindle. Disc sander accessory,$14.50 add'i. Mitre guage,n 5 ta6 IbS.544.504 FOOT WOOD LATHE LONG BED WOOD LATHE JOINTER -PLANER•Does the job of $150 unit. Tubularsteel bed rails, screw action tailstock. Use any size motor. 4" faceplate, $2,90. 30559Ibs. f.o.b. factory.00DELUXE HEAVY DUTY LATHEDouble shielded, lubricated for life' b"rin;;' f o toO571.006.55" version of the deluxe heavyduty lathe. has ball bearing livecenter in tail stock and extra heavy?dbta 40 Ibs.ry587.50RADIAL 32"PRESSDRILLPrecision 32" radial unit has standardfeatures and many extras.Depth of throat up to 16", Head tiltsand table stays level Drills to centerof a 32" circle. Cast iron and.steel. Less motor. belt and pul-i o; I bs. I . o . 579.90b.These power tools have no chrome, embossed nameplatesor any other useless extras . . but they do the same job astools costing 2 to 3 times the price! And their performancehas been proven in the shops of literally millions of professionalsand serious amateurs.Don't be misled by AMT's low prices; these are qualitytools. They are full scale, full speed and offer top performanceand precision. There are good reasons why we areable to offer such values. Here is how we do it: 'VEngineered for simplicity: After years of engineeringrefinements. virtually all the frills have been eliminated inorder to save you money. Faster machining: Speciallydesigned automatic machining equipment cuts costs bycutting production time. Standard parts: Ordinary hardwareitems replace custom parts for enormous savings.Volume: Our own foundry. our huge massproduction facilities and our large buyingpower-all keep costs down. Direct factorypurchase: You pocket the savings but we stillv offer our two terrific guarantees!POWER SAW: Our titt arbor saw comes completelyassembled with ground cast irontable. safety guard, splitter and mitre guage.r - - -74" x 22". Cast iron and steel, precisionground adjustable tables.For planing. joints. bevels. Cuts to1/6" depth, Fence adjusts from 0"to 50° . Steel knives and dualguards .Use any motor. Precisionball bearing industrial model.n 4 b6 :y 19IbS . 554.85WOODSHAPERKIT•Makes beads. coves. moldings.tongue-and-groove joints. Accurateat high speeds. Sealed andgreased for lif ball bearings. Lesswood. Takes '/ h.p. motor or larger.standard cutters. Optl., hold downassem ., $4.50 add ' i.9 Ibs. f.o.b. factory. 53490I n addition you get a free set of cabInet base plans thatshow you how. with one sheet of 3/4" plywood. you canconvert this saw into a floor model with a big 27" x 24" top.Cabinet rip fence only $7.50 additional. And you can useyour new saw to cut out the cabinet base!BRAND NEW. ELECTRIC MOTORDevelops a full 1 h.p. (purchased separately• $44,65) 17 Ibs, I.o.b factory $39.80,AMT OFFERS TWO GUARANTEES:OUR lG-DAY MONEY BACK GUARANTEETry any of these power tools and compare it with anysimilar machine at any price. If not satisfied return it forprompt no questions asked refund! We pay the returnshipping charges.lG-YEAR•FULL SERVICE GUARANTEEAny part or parts of these AMT power tools (except motorwhich carries a one year gaurantee) which becomes inoperativefor any reason within 10 years after purchasedate will be repaired or replaced by the factory with nocharge to the purchaser other than postage.Fourth & Spring Sts .. Royersford. Pa. 19468or $5 deposit each I0 Optional hold down kit, $4 50fGeneral Electric Motors$39.80 (with other item)$44,65 (purchased separately)I___AMERICAN MACHINE & TOOL CO., 4TH AND SPRING STS., ROYERSFORD, PENNSYLVANIA 19468BUY DIRECT . . . USE THIS HANDY ORDER COUPON TODAY -American Machine &- - .,Tool Co .. Dept, FW70I , .. ., .. Please send me the units checked. Payment in full enclosed $= 'v4 .' itemStandardo LongI -.- _.- - ...enclosed, balance C,O,D, I must be fully satisfied or will return unit within 10 days forfull refund. <strong>No</strong> questions asked.III I 4 7 0 8" tilt arbor saw, $44.60 0 Long bed wood lathe, $67.50 0 Wood shaper kit, $34,90 0 rip fence, $6.50Icabinet rip fence. $7.50. '2 Set of 3, $6.50Belt sander, $44,50o 0 0Set of 6Disc sander attachment, $14.50 , $<strong>23</strong>.000 Mitre guage for sander, $2.95I 3 5 0 Jointer-planer, $54.65Visil our Royersford factory show·I I I0 12" swing , 4 ' lathe. $59.00 0 Ball bearing spindle. $14.65 room for tese same low pric .0 Deluxe bali bearing lathe,$71.00I 6tilting head, $79,90on weekdays and 9 to 12 on Sat.I0 Face plate, $2 90I 0 Ball bearing spindle. 5 9.75Turning chisels or any lathe0I NAME- - - - - - - - - - - - - -- ---- - - - - - - -o Face plate, $2.90I ADDRESS0 32" radial drill press with 4th and Sprong Sts, From 9 '0 4,30L CITY STATE ZIPIIIJ13

Methods of Work (continued)make two cuts-one to rough length (leaving a half-kerf extra)and the second to final length. Of course if the machineis out of square to begin with, all bets are off.-Pat Warner, Escondido, Calt!ASK FOR FREE CATALOGSOLD THROUGH LEADING DISTRIBUTORSWETZLER CLAMP CO., Inc.43·13 11TH STREETLON G ISLAND CITY . N.Y. 11101TE L. 212'784'2874An intensive full-time learningsituation emphasizing traditionaltechnique as well asmodern methods of woodworking.Individual level instruction.ample work areas and an industriallyfurnished machine roomprovide a stimulating and efficient learning situation for the seriouswoodworking student of limited experience. Bench spaces availablePRIMROSE CENTERforFine Woodworking and Furniture Design401 West Railroad SL Missoula, Montana 59801Phone - (406) 728-5911for September <strong>1980</strong>. For further inrormation write or call:••*•••Lumbers, Plywoods & VeneersOver 80 species available•"woodAccess to millions of board feetKILN DRIEDz ... .... envtishY_ Ro.ewoodM.p". . i • Premium 111 finest quality only..... ... 1'Ii"'1§EXOTICHARDWOOD&. HARDWOOD CREATIONS<strong>23</strong>3 N. FEDERAL HIGHWAYDANIA, FL 33004(305) 922·WOODSItu, Cocobolo ""-pie Curly EcuadorIr

Methods of Work (continued)WorkPlywood fenceMiter gaugeBraceRipfenceTwo sawbladestenon, for example, simply requires mounting the two bladeswith a Y4 -in. and a %6-in. spacer between. My set of custommachinedspacers are 2Yz-in. discs drilled to slip over the sawarbor. Spacer thicknesses range from % in. to 0.005 in. Topass the work through the blades, I use a standard mitergauge tracked in a plywood fence as shown above. This approacheliminates vertical rocking and thus is safer and moreaccurate than other methods.-Mac Campbell, Harvey Station, N. B. , CanadaSharpening jointer knivesHere is a jointer-knife sharpening jig that saves money, eliminatesfrustrating at-the-sharpening-shop delays and gives thewoodworker a bit more independence. The jig, used with adrill press and cup stone, consists of a %-in. plywood orparticle-board base and a sliding knife-holder. The holder,slotted to accept the jointer knife at the right sharpeningangle, slides in an accurately sized channel in the base. Severalthumbscrews, tightened in threaded holes, threaded in-.serts or T-nuts, lock the knife in the holder slot during grinding.(To tap wood, drill pilot holes, use a tapered tap andback the tap out often; maple and other hardwoods tap aboutlike hard brass and hold as well.)To use the fixture, chuck a medium-grit 1 Yz-in. cup stone(contact <strong>No</strong>rton Co., 1 New Bond St., Worcester, Mass.01606 for distributors) in the drill press. True the stone ifnecessary (I use an old masonry blade) . Then clamp the basein position on the drill-press table so the knife and stone arealigned as shown in the sketch. Lower the quill until the stonebarely touches the knife, lock the quill and grind the knife bysliding the holder under the stone. Lower the quill a bit andgrind again. Repeat this operation until all nicks have disappeared.When the final depth is reached on the first knife,set the drill-press stop to preserve the setting for sharpeningthe second and third knives.To avoid warping the knife by heating unevenly, take lightcuts, move the holder smoothly and use plenty of thumb-Slidingknife-holder1 Hardwoods: We carry over 30 species ofAmerican and imported hardwoods, many ofthem rare and exotic; air and kiln dried; customdimensioned and thicknessed from 1/2"through 4". We also carry "Architectural Grade"veneer core -and high density fibre -core plywoodin American and imported woods, good 1 and 2sides. For hardwood lumbers and plywoods ...we are the source.2 MaIdta Portable Power Too": Consistenthigh quality, dependable, powerful. .Routers, circular saws, planers, jointers, drills;disc, belt , finishing and polishing sanders;screwdrivers, drywall drivers; chain and mitersaws. These tools have the most compact, best builtand most powerful motors for small power tools inthe world. Designed for comfort and durability. Forprofessional portable power tools ... we are thesource. Send $1 for your Makita catalog.3 Poweraaatic Power Too": Designed bythe industry for the industry. Nationally recognizedas the leader in the manufacture of stationarywoodworking machinery. Tilt arbor tablesaws, band saws, scroll saws, jointers, planers, drillpresses, belt & disc sanders, spindle shapers,lathes. These are fine-tuned machines withsensitive and accurate adjustments you candepend on for the most subtle detail. Sensible inprice, solid in design and superb in action, thesemachines are acclaimed for strength andperformance right down the line. For stationarypower tools ... we are the source. Send $1 for yourPowermatic catalog.4Greenlee Hand &: Bench Too": Famousamong professional woodworkers fornearly 100 years. Highest quality tools and accessories:Carving and sculpturing sets; mortise,firmer, bevel-edge and paring chisels; straight,tapered, Multi-spur and auger bits; twist gimlets,screwdrivers, plug cutters, countersinks, and manyspecialty tools. For premium quality hand andbench tools and accessories ... we are the source.Send $1 for your Greenlee catalog.5Accessori- &: SuppH_: A wide assortmentof all those supplies and accessories youneed to be the best craftsman you want to be.Router and milling bits, carbide-tipped saw blades,sanding belts and papers, glues, clamps, specialtytools and supplies for particular needs. Custommaderouter bits and shaper bits; and custommademouldings in any of our species. Forprofessional accessories and supplies, and forcustom-made cutting tools and mouldings ... we arethe source.The CatalI og: An all-inclusive, complete catalog containing ourextensive selection of lumber and plywoods; profeSSionalwoodworking tools; accessories and supplies that are all shoptested on the job and quality proven by John Harra, cabinetmaker.Send $2.50 for yourCatalog and supplements<strong>1980</strong>-81... the source.John Harra Wood & Supply Co.JohnHarraWood f1 Supply Co.39 West 19th Street, New York, NY 10011 212-741-029015

Methods of Work (continued)screws to lock the knife in the holder. Long knives areespecially prone to warping, so mist them or let them coolbetween passes. -James E. Gier, Mesa, Ariz. FaceplateWorkpieceDecorating turned goodsTo produce decorative black rings on tool handles and otherlathe work, twist a dowel peg handle on each end of a 12-in.long piece of soft iron wire. Any medium-gauge wire will do.To use, scribe a shallow starting groove in the work with thepoint of a skew. Then press the wire against the startinggroove. In five or ten seconds friction will generate enoughheat to scorch the groove. The resulting fine black ring, sparinglyused, gives a tasteful decorative effect.1. Scoregroove-Larry Joseph, Alva, Okla.2. Scorchwith wireTurning ringed objectsAn effective mandrel for turning napkin rings and other annularobjects can be made as follows. Choose a suitable hardwood(such as hard maple) and mount the wood to the face-MELVIN LINDQU ISTMARK LINDQUIST16WEEKEND WORKSHOPSIntensive.ind iv idualized instruction atall levels (limited to 10 persons) in theartists' studio located in the verduredhills of New Hampshire.<strong>AUGUST</strong> WORKSHOPSAug. 1-3Aug. 8-10Turning Spalted WoodThe Art of the VaseAug. 15-17 Carbide Tipped Tool <strong>Making</strong>Aug. 22-24 Turning and Sculpting Burlsand Found WoodFor further information & schedule ofFall & Winter Woodworking & PhotographyWorkshops send for free brochure to:Lindquist Studios, Henniker, NH 03242BEAUTIFULWOOD FINISHESWatco Danish Oils provide an elegant,extremely durable penetrating finish INthe wood, not ON it! Primes, seals,hardens, protects and beautifies in onefast, easy application.Pipe plugplate with the grain oriented perpendicular to the axis. Turndown the end of the mandrel to give a slip fit with the workpiece,leaving a larger-diameter locating shoulder on the baseas shown in the sketch. Next, drill and tap the end of themandrel for a tapered pipe plug of suitable size. First selectthe recommended tap drill size for the pipe thread and drillinto the end of the mandrel 0/4 in. or so deeper than the locatingshoulder. Then tap the hole so that a pipe plug willthread in halfway. The resulting threads, though rough in appearance,are quite strong if the grain is oriented as suggested.To complete the mandrel, cut two crossed saw kerfs tothe same depth as the hole.To use, slide on the workpiece and screw the pipe plug inthe hole. The plug will expand the mandrel, gripping theworkpiece firmly. -Edward F. Grah, Napervtlle, III.and Charles E. Cohn, Clarendon Htlls, III.Methods o/ Wo rk buys readers ' tips, Jigs and tricks. Send detatls,sketches (we '/I redraw them) and photos to Methods,Fine Woodworking, Box 355, Newtown, Conn. 06470.Natural and Medium,Dark and Black Walnutcolors for all woods.WriteWatco-DennisCorp., 1756·22nd St.,Santa Monica, Calif.90404, Dept. FW-70Build a quality Grandfather Clock byKuempel that can be a true heirloomin your family for years and years.Available in easy-to-follow plans orcomplete semi-assembled handcraftedks with illustrated instructions.We'll show you how to assembleyour own at less than halfthe cost. Write for <strong>Free</strong> descriptiveliterature.KUEMPELOept. 103 -21195 Minnetonka Blvd.Excelsior, Minnesota 55331CHIME & CLOCK WORKSEXOTIC ANDPRECIIUSWOODSROSEWOODSEBONIEScoco BO LOZEBRABUBINGAPADAUKLogs, lumber, sawn veneer andmusical instrument components.Wholesale inquires only.For more information, call or write:Nazareth, Pennsylvania 18064215-759-2837

•Sterling Pond Hardwoods, Ltd."Quality Lumber-Friendly Service"Ash, Basswood, Birch, Bubinga, Butternut,Che rry, Cocobolo , Cotto nwood, Ebo ny,Curly & Bird's-Eye Maple , Red & White Oak,Pines, Poplar, Purpleheart, Walnut, Mahoganies,lroko, Teak, Rosewoods, Kingwood,Tulipwood, Pearwood, Pado uk, Ze brawood.Many thicknesses 4/4-16/4 in stock.Wood fo r furniture, flooring, paneling,carving, turning.Send S.A. S. E. for pricelist-free estimates.Visit our warehouse and showroom of finewood products representing over 70professional woodworkers .412 Pine StreetBurlington,802-863-5820 VT 05401HORTON BRASSES<strong>No</strong>oks Hill Road, P.O. Box 95FCromwell, CT 06416Tele: (203) 635-4400Mfrs. of Cabinet and FurnitureHardware for Homes and AntiquesSend $1.50 for a CatalogueEnjoygooddesignQueen Anne Highboycirca 1760The ultimate example of theCabinetmakers Art . . .Choose Cherry, Mahogany,or Walnut.Catalogue One of Seventeen$1.00 KITSoffered by•. _ I E2!P"'.,..-.-0 Dept. 161, Box 404. Grayslake. IL IlCXnJ312/2<strong>23</strong>-7655Design Book Two contains the best work in wood by 1,000 present-day woodworkers-I, 150 photos of different works, from tools and musical instrumentsto chairs, beds, tables, desks, cabinets, houses, sculpture, carving and marquetry.There are even a couple of impressive canoes. Each photograph is accompaniedby the dimensions of the work, as well as a list of the woods andprincipal techniques used. And the craftsmen themselves add useful remarkson how they work and why. There's also a directory of woodworkers, givingthe shop name, address and specialties of the professionals represented.The Biennial Design Book is already a classic, with 65,000 copies sold to date. Itincludes 600 photographs of beautiful things in wood-from the chaste eleganceof a pearwood side chair to the whimsy of a kinetic sculpture. Every workin this book, whether traditional or contemporary, is an example of the newhigher levels of craftsmanship being reached in America today. From antiqueinterpretations to ultramodern fantasies, the Biennial Design Book shows whatamazing things can be done with wood.Design Book Two:Biennial Design Book:9"xI2", 288 pages. 9"x12", 176 pages,Postpaid price: $10, paper.Postpaid price: $12, paper;$16, cloth.TO ORDER: Use the convenient order form and postage-paid envelope in the back of this magazine orsend your order with payment to: (Connecticut residents, add 7'1z% sales tax).52 Church Hill Rd., Box 355, Newtown, CT 06470© <strong>1980</strong> The Taunton PressMORESAVINGSFROMBrassWood ScrewsFinest QualitySlotted Flat or Roundheadlindicate type )II Lth Per 1000 4 $1.90 8 lJ7 $740 10 1 $6 900 195 8 1 8.70 10 11, 8301 Yo 190 8 2 97·0 10 II, 9401 }" 1.95 8 2Yo 11.55 10 1 3/.1 10951I, 2.20 8 21 , 12.50 10 2 12052 Yo 1.80 8 2r. 15.65 10 21.1 15502 195 8 3 1805 10 21 , 18552 "2 2.20 9 , 4.55 10 2, 20.802 225 9 4.50 10 3 <strong>23</strong>.052 2.55 9 4.90 10 3', 29.053 Y. 225 9 % 5.55 10 4 43 553 2.20 9 1 6.00 12 17 7703 J7 2.40 9 lY. 7.05 12 "t. 7 953 2.55 9 1 \7 8.30 12 8.753 2.80 9 1 9.50 12 '8 9.703 % 3.30 9 2 10.50 12 1 10.303 1 3.55 9 2Y. 13.15 12 lY. 10.954 Y. 1.90 9 2\7 16.05 12 1\7 12.654 2.05 9 2:r. 17.75 12 1 14.304 \7 2.25 9 3 21.15 12 2 16.054 2.45 10 \7 5. 15 12 2Y. 21.054 :r. 2.75 10 5.30 12 2\7 22.654 % 3. 15 10 5.65 12 2 27.454 1 3.30 10 % 6.20 12 3 28 .904 lY. 4.55Sandpaper4 1)1 5.305 2.55 <strong>No</strong>rton/Carborundum5 2.80Garnet or Aluminum Oxide5 3. 155 % 3.45 (indicate type)5 1 3.80 9" x 11" Sheets-Open Coat5 lY. 4.40 10 1005 1\7 5.80 Sheets25 50 Sheets6 \7 2.806 3. 156 3.306 3.806 16 lY. 5.006 1\7 6.006 1:r. 7.956 2 8.507 \7 3.204.15 3.407 3.80 4.307 1lY. 5.701 \7 6.707 1 8.757 2 9.704.75280A $1.70 $3.50 $6.55 $12.70240A 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.70220A 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.70180A 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.70150A 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.70120A 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.70looA 1.70 3.50 6.55 12.7080A 1.90 3.95 7.35 14.15150C 2.35 5.30 10.10 19.45120C 2.35 5.30 10.10 19.45looC 2.35 5.30 10.10 19.45800 2.70 5.90 11.35 21.70600 3.00 6.75 12.95 25.10500 3.45 7.75 1 4.80 28.70Aluminum Oxide-<strong>No</strong>n filling9" x 11" Sheets-Open Coat8 \7 3.45 280A 205 4.80 9.10 17.25'8 3.95 220A 2.05 4.80 9.10 17.258 4.40 180A 205 4.80 9.10 17.258 4.90 150A 2.05 4.80 9. 10 17.258 1 5.30 120A 2.05 4.80 9. 10 17.258 lY. 6.45 100A 2.05 4.80 9. 10 17.25Shipping charges, add(minimum $10 in merchandise)orders up to $ 20 -add $ 2.50$20.0 1 to $50-..<strong>$3.00</strong>$50.0 1 to $100-..$3.75Over $100-..$4.75We also accept Ma ster Charge and Visaon orders of $20 or more$1 for complete tool catalogfeaturing:DISSTONGREENLEECOLUMBIAN VISESThe To ol Works76 9th AvenueWETZLER CLAMPSand much more NY, NY 1001117

Q & AONOVERMACHINERYAddsOUfPowerto Your WoodworkingYou may know us for our line of fine hand tools.many 01 which we produce in workshop here inrural Parkman. Ohio.What many do no! know is thai we have a line of fine"honest buill" machinery, manufactured in Taiwan toour specifications. OUf machinery is of very heavy castiron construction. compelively priced, and well suitedto the small shop owner or the serious amateur.Send for our 20 page catalog which has 5 pagesdevoted to our machinery, giving complete details andspecifications.Or beller yet - stop in our show room and see all ofthe itclll in our catalog for yourselt. Our store alsostocks many other interesting items such as books ami_____________ antique tools.Dear Conover:Enclosed is 51.00 for your latest 20 _page catalog ofhanu maUL' tools and machinery.NameAddressCity __ St.t.ZipConover Woodcraft Specialities, Inc.18]25 Madison Rd. Parkman, OH 44080(216) 548·5591WOODTURNING SCHOOLBeginners and experienced turners are invited fortwo·day workshops offered throughout the year. With amaximum of two students. learn and practice bowl andspindle turning-· emphasis on cutting techniques.I do a lot of kitchen cabinets and have tn'ed various finishes-inparticular, polyurethane, lacquer thinned 50150and Watco ozl followed by wax. I Itke both the look and theworking properties of the lacquer and the ozl finishes betterthan the polyurethane, but when I'm asked about which finishis most durable, I don't know what to say. Is there any informationavazlable on the comparative durabzlity of thesefinishes? - Claire 0 'Meara, Washington, D. C.To the best of my knowledge, there's nothing in print thatdeals with the kind of durability comparison you're lookingfor. Theoretically, a good polyurethane should be the mostdurable and wear-resistant because it leaves behind a thickfilm upon drying. Polyurethanes have a higher solids contentthan either lacquer or Watco oil, which means that more materialis left on the surface when the solvent evaporates. However,polyurethane wouldn't be my first choice since youoften run into problems of poor adhesion when refinishingwith it (if refinishing is a consideration) .Lacquer (Deft) thinned 50/50 as you use it produces extremelythin coatings. I wouldn't thin it. Try using it straightfrom the can, brushing it so that laps and bristle marks don'tshow. A little thinning might be necessary, but 50/50 is waytoo much. Lacquer produces a good, wear-resistant finish,but you need two or three coats to build up a decent thickness.This will probably stand up as well for your purpose aspolyurethane, without recoating problems if you ever have torefinish the cabinets or touch them up.Watco oil penetrates more deeply than either polyurethaneor lacquer, and builds up a protective coating in the woodrather than on the surface only. Because it helps toughenand stabilize the wood, it also delivers excellent wear res istance.1'd use at least two coats, with a couple of days dryingtime between. Using wax as a final treatment over Watco is agood way to give you the luster you want, though it will eventuallysoften and pick up fingerprints and dirt and will requirecleaning and rewaxing at intervals. -Don NewellRecently I tn'ed veneen'ng and came upon an unexpectedproblem-separation and splitting of the veneer sectionsshortly after gluing. I used Elmer's Professional Acrylic ContactCement and fo llowed the instructions in gluing a fo ursectionwalnut veneer to a sheet of 1 "Is-in. particle-board(<strong>No</strong>vaply) core backed with a "Is-in. three-ply doorskin. Iscraped off the paper veneer tape about an hour after I rolleddown the veneer. About an hour later the onginally tzghtjoints began to separate as much as Y32 in., and cracks developedalong the grain.What went wrong? DidI use the wrong kind ofglue? DidIremove the tape too soon? The veneer was slzghtly lumpy before gluing. Should it have been steamed and pressed flat?-Richard E. DeSimone, Lisle, III.Because <strong>No</strong>vaply is quite stable, your problem is probably theresult of the veneer shrinking rather than the substratum expanding.To solve the problem, figure out why the veneer islosing so much moisture during the first several hours followingassembly. The veneer might have a fairly high moisturecontent in an extremely dry workshop. Was your veneerstored in a damp place such as a garage or basement?Another source of moisture could be the adhesive itself.1'm not acquainted with the particular brand of glue youused, but it sounds like a water-base emulsion. Did theveneer tend to curl (convex to the spread side) when the adhe-INthe While Myford here lathe you will which usewe and import stock from for sale. England45c RUSS ZIMMERMAN STAMPS FOR fUll O(TAllSPUTNEY. RfO 3. BOX VERMONT 57A 05346IIIFull-Size FURNITURE PLAN18th Century PINE CRADLE-'"1lll =-- w 36" z placeAuthentic 18th century design. Alljoints hand·pegged like the original'ong, 291A· high. Perfect for fire·wood. masazines. Baby, too!woodworker's delight. Plan 1120ACATALOG150 diff full·slze S 1'" only $5.00.refunded with ht order. H25 Sherman Avenue. Evanston, III.prof. ptas-$1.00 FURNITURE DESIGNS,DepI.KP-7060201NEW! THE AMAZINGf!mReproduces 3-d imensional objects inwood as easy as a key maker makingkeys. But best of all, the Dupli·Carverallows you to make extra money!Here's what it can do for youPicture These:...A 'hand carved' scroll on aGrandfather's clock•Carved oval picture framesRestored antique partsOmate claw table legsA lion's head projecting from yourfireplace mantelCustom signsA beautiful statue of theAmerican EagleA black powder gunstockExpand your workshop horizons todaywith this versatile machine. YourDupli·Carver can pay for itself with thefirst few objects carved.DUPlI·CARVERTMWrite or call todayfor more information4004 West 10th SI.Indianapolis, IN46222(317) 243·756518

ZipQ & A (continued)sive was applied? Since contact cements aren't very rigid, theshrinking of the swollen veneer as the moisture graduallydissipates could cause the glue line to creep and result in openjoints. I suggest rereading the instructions carefully to see ifthe glue is intended for solid-wood parts only. Also, tryanother type of adhesive and see if the trouble disappears.-R. Bruce HoadleyI do custom inlays and marquetry and want to know x/ there isa solvent-base glue fo r wood I have no trouble with the marquetrywhen using Titebond (aliphatic-resin glue) , but whenI inlay designs in solid wood, the glue expands the veneerenough to cause buckles, even though I use a veneer press. Iprefer not to use contact cement because it has no gap-fillingproperties. If epoxy glue is my only alternative, where can 1buy it in quarts or gallons? Also, what is Scotch glue? I'veread about it in marquetry books but have no idea what it is.-Mike C. Durbahn, Mankato, Minn.Many marquetarians and inlay craftsmen use epoxy (some formulasdissolve with lacquer thinner or acetone) , and you canget large quantities from marine suppliers, or you can order itfrom Chem-Tech, 4669 Lander Road, Chagrin Falls, Ohio44022. If you decide to use epoxy in your marquetry, it willfill gaps quite well and can be colored with aniline dyes tomatch the wood. Many woodworkers grind up some scraps ofthe wood they're using to get dust of the right color and mixit with the glue.Elmer's Carpenter's Wood Glue seems different enoughfrom Titebond to make it worth a shot. Or, if your shop iscold, rig up a tent over the work with light bulbs inside to keepthe work warm enough for plastic-resin glue (cascamite). YourHARD TO FINDWOODWORKING TOOLSCATALOGSend $1.00 for our BIG complete catalog ofhand woodworking tools and books. Youwill find our large selection of fine traditionaltools a joy to behold. It is truly thecraftsman's bible.Send for free informationon the Myford ML8lathe. It's quality throughout.FROG TOOL CO. LTD.700W. Jackson Btvd. Dept. SE Chicago ll, 60606CURLYWALNUT.& BIRDSEYEBUTTERNUT.MAPLECHERRYMost other Domestic WoodsEXTRA WIDE/EXTRA THICK STOCKSPAL TED WOODSTURNING & SCULPTING BLOCKS• SOLID SQUARESCabinet & Economy Grade LumberStock for Woodwork Flooring. PanelingNO DETAILED MINIMUM-MAIL. LISTING IIO FREIGHT {71111 SHIPMENT 942-l1li31D.A. BUCKLEY, R1, W. VALLEY, N.Y. 14171SHARP TOOLS FOR SHARP PEOPLE -Difficult applications graphically illus·trated ; money·saving hints and safetyfeatured: send $2 for BIMEX's 48·pagecatalog or Makila's 40·page catalog (or$3 for bOlh) and start selectingtools wisety.jj) , Allanta. GA 30324 BIMEX INC. 487 Armour Circle. N.E.problem might be compounded by winter dryness, makingthe wa.ter added by the glue an important factor.Scotch glue is hot hide glue. It's the traditional choice, butit's water-soluble. Tage Frid writes about hide glue in his articleon hammer veneering (FWW #10, Spring '78, p. 52).You can get some feel for its characteristics without having tobuy a glue pot by trying Franklin's liquid hide glue, althoughit's not really the same. You are wise to avoid contact cement.1 have an 8-in. jointer and am having difficulty setting theoutfeed table at the proper height in relation to the knives. 1try to set it so that it 's in exactly the same plane as the top ofthe cutting arc. But sometimes the jointed edges of myboards are concave, and sometimes they 're convex. Very seldomdo 1 get a perfectly straight edge, especially on longboards. Obviously I'm doing something wrong. What is it?-Larry Green, Bethel, Conn.To joint a perfectly straight edge on a long board requiresmore than a properly adjusted machine; it demands correcttechnique as well. You're right about the outfeed table beingthe same height as the knives at the top of their cut, but thisadjustment can be tricky, and the slightest variation will producea difference in the jointed surface. If the outfeed table islower than the knives, you'll get a concave surface (a sprungjoint); if the outfeed table is higher than the knives, the oppositewill happen. And, even if the outfeed table is set exactlyat the height of the knives, you'll get a sprung joint ifthe table, not locked firmly in its ways, angles down slightlyfrom the cutterhead. In fact, one way to produce a sprungjoint is to loosen the lock screw that bears against the gibs.This lets the outfeed table droop. Also, putting the properr--------------,Time to: test your skill.I<strong>No</strong>w you can build yourown Mason & Sullivanheirloom quality,.antiquereproduction clock.Over 20 different modelsavailable In dO·lt-yourself.pre-cut or semi-assembledform for all levels of skill.Grandfather. Grandmolher.wall, desk. mantle and morehand·matchedAll solid 3;""kiln-dried hardwood In walnut.oak, cherry or Hondurasmahogany. Imported preciSion movements and chimes.Solid brass dials. Clocksyou'll find challenging tomake and at a savings youcan appreciate. So, If you'relooking for the finest clocksaround don'l wasteanother minute BUild aMason & Sullivan It's wellworth Ihe effortSend for ournew catalog 32 page______________________today.o Please send me your new colorcalalog of lOP quality antique reproductIonclocks I can bUIldo I enclose $1.00___ __ ___for catalog.NameAddressCity/StateMason & Sullivan Co.Dept. 2112, Osterville, MA'-----------------' 0265519

Objective: Rockwell maKes jipolsthat have versati lit4 andrcapacJ!

Q & A (continued)and expensive. The finer households, whose furniture waswhat mos't was modeled after, often contained matchingpieces of clothing, jewelry and arms, difficult to replace.Since houses as a whole were not so secure as today's, the furniturehad to have locks. Often the keys to drawers, closets,larder and wine cellar would be kept in one drawer, and thekey to that carried by the master of the house, to be passed onto servants or guests when necessary. The need for secure casefurniture is one reason for dustboards; they prevented accessto other drawers by forcing open only one.I read an article in a British journal where a cabinetmakerstates that a hollow grind on a mortise chisel is wrong andrenders it useless. He claims that a correctly sharpened mortisechisel has a convex profile. Could you comment?-Barry Schwartzberg, Forest Htlls, N. Y.The profile of a monise chisel can be convex, concave orstraight. In any case, the angle of grinding can vary considerably,and this is of as much consequence as the profile. Thegrinding angle and profile, like so many decisions in workingwood, will depend on the wood that's being cut, its densityand the amount of waste to be removed. With a convex profile,the blade will be pushed away from the tissue. In cuttingMore scoop) Less scoop+large joints, such as those used in timber framing, there is aplace for this profile. Likewise, if you want to take large bitsout of the monise with each move, then the scooping actionwill be assisted by the convex profile. Under either of theseconditions, a hollow-ground blade is liable to break or wouldbe less effective in its scooping action.<strong>No</strong>w consider a Y4 -in. wide, through monise in a piece ofcherry that's "'h. in. thick. The hollow-ground chisel would beperfectly good for this. The chisel with the convex profilewould be clumsy. In either case, a straight-ground chiselwould perform well.-Ian Kirbyexcellence In wooOwoRklnqThe first professional/public show of its kind:to exhibit and sell products of fine woodworkingTrade Show Exhibits: Marketplace Exhibits: Seminars:Precision machinery, Chairs/Tables/Desks. Lectures, demonstrations,• hand and power.•Cabinetry.questions and answersSpecial-purpose tools Special-use furniture. on a variety of timelyand equipment.Decorative pieces. woodworking topics.Hand tools, all kinds. Reproductions.Conducted by well-knownWorkshop accessories, Carvings/Turnings. instructors in woodworking :workbenches, clamps. Musical instruments. including TAGE FRIO,Abrasives/ Adhesives/Sculptures.Renowned Woodworker.Finishes.Plaques.SAM MALOOF,Woods and veneers. Carved doors. Master Craftsman.Schools/Publications. Toys. ROBERT STOCKSDALE,Dean of Woodturners.__October 2-5, <strong>1980</strong> Hyatt Regency Downtown, ChicagoDon't miss this opportunity . Exhibit spaces still available:Phone or write: Marvin Park & Associates 600 Talcott Road Park Ridge IL 60068Phone: (31 2) 8<strong>23</strong> - 21 51Don't Just buy a woodworking machineBUY what the machine can really doINCA-PRECISION SWISS STATIONARYPOWER TOOLS8%" wide jointer/planer (illustration}-12, OOO vibration free cuts per minute.Will handle hardest teaks to balsa w oods to glass clean finish.Optional thicknessing attachment permits board thicknessing from 2'M1"max. to '/.0" min. to absolute perfection. Five other indusfrial qualitymachines, designed for precision production and ced for the per1ectionistcraftsman, hobbyist and cabinetmaker.If the grind is too hollow, the chisel tip may break off.-Frank KlauszI'm trying to find a tool called a gn·nder-honer. It has interchangeablestones and a special honing speed of about78 RPM. I've seen some cheap, junky models of this machine,but I want one that 's heavy, steady and produces little vibration.I need to hone and polish tiny tools to precise angles..-Stephen Litchgaren, Austin, Tex.Oliver Machinery Co. makes a machine called an oilstonegrinder. It has three speeds-1800 RPM, 700 RPM and10V." combination JOinter/planer with automatic feed thicknea_. 10" bandsawfor wood, non-ferrous metals, pla8tic. 9 blade selectlon8, 6V." depth of cut. 10"circular saw 3" depth of cut. Attachments to perform 15 addHlonal o pe ratlons.T' circular 8aw 2'/>2" depth of cut. Same attachment8 a8 10" 8aw. VERTICAL SPINDLE SHAPER, 3 8peed.See your local Home Improvement Cenler, Hardware or machinery dealer or wrileAnson Industries Inc. for information of an INCA dealer nearest you.ANSON INDUSTRIES INC.Dept. MO 4115__ __San Fernando Road, Glendale. CA 91204_Please send me the INCA precision stationary power tool catalog and price sheel. Ienclose $1.00 for first class postage and handling.NameCity________ Address__ 51. ZipDealer Information Upon Request21

Q & A (continued)300 RPM-and can do conventional grinding as well as honing.It's also equipped with a leather stropping wheel and aspecial tool holder. It costs about $1,900. The address is 445Sixth St. N.W., Grand Rapids, Mich. 49502 .-Le/on TraylorWhat's the best way to Jam chair razls to round, slightlytapered legs? My main concern is how to use a mortise-andtenonjoint and sttll get a precise fit where the shoulders 0/ therazl meet the leg. -Fredrick Lehman, Cedar Rapids, IowaThe easiest way to make a tight mortise-and-tenon joint in aturned chair leg is to cut the cheeks of the tenon in the regularway and then to cut the outer edge of the shoulders in atan angle that's a little steeper than the one made by the arc ofthe circumference of the leg. Usually the length of leg that'sinvolved in the joint is left untapered; otherwise, theshoulders of the tenon must be contoured appropriately.When pulled up in a clamp, the edges of the shoulders willcut into the leg. The best glue for this joint is epoxy because itwill fill the small gaps left berween the shoulder and the leg.-Tage FridFollow-upRe nontoxic bowl finishes (FWW #22, May 'SO, p. 24):Thank you for the recent advice on finishes for bowls. Shortlyafter writing you, I wrote to United Gilsonite Laboratories inScranton, Pa., the makers ofZAR polyurethanes. I was happyto hear that ZAR is nontoxic and suitable for bowls and otherfood utensils.- Thomas A. Laser, Springfield, Va.In reference to Frank S. Bowman's question (FWW #2 1,March 'SO, p. 24) about single-end tenoners: These machinesare a waste of money. They are designed to perform only avery specific function in connection with the mass productionof windows and doors. If you have enough quantity runs toafford the required setup time for a single-end tenoner, thenyou might as well buy a double-end tenoner, which will performmany more tasks much more economically. If not, stickto your table saws and shapers.-Walter Rich, Philadelphia, Pa.USE ON:Drill pressSmall motorLatheShopsmilhRockwellMonlgomery WardCraftsman\I," Elec. drillSIMPLEAS1•2•Sectionthrough legaciapt(-'rwill suhstitutea \4"Sleeveless DRUM SANDERNO PRE-MAOE SLEEVES TO BUYECONOMICAL·Simply ('ut sandpaperfrom standard size sheets. UNIQUE wayof holding paper to drum. Twist of keyand I"'pe, is light. SPONGE RUBBERW('ha(·king insures long wear of paper.Ilubs Ih:" bore, Price indudcs Y.z"but upon requestadapledor:l\small d'ills. ADD $2.25 PERORDR FO .!'l HANDLING.-] x 3 long . 1 $12. -2" x 3" long..$13.75-21h" x 3" long$14.40-3" x 3" long ........ .. " $15. 70ABOVE 4 DRUM' $51.202"''' x 4"''' . . ....... . .. $19.903" x 4"'" ...... . ... . ..... $21 .25Ahm (. sin's (without adapters/ alsoailablt' with 'hot 20 H.II. T Head(St.'ars. \\'ard).%H OAK-WALNUT-BIRCHbore (Shopsmith) exccpt 2nx3HSend Check or Money OrderMONEY BACK GUARANTEE•• SINGLEY SPECIAL TV CO INC.P.O. Box 771 ·FHendersonville, N.C. 28793Dust-proofWood FinishingBeauty, depth and luster of a handrubbed finish without specialequipment or tech niques .Acclaimed by craftsmen for over50 years.Write for free guide to wood finish ing .17TH CENTURY CRADLEcopied from an originalFulI·Size PlansFull·size, traceable pattern • Materials• ItOe"tailed instructions • Kit ao available.• A treasure to hand down generalions • Write for detaiPlans:JOHN GRAVES$5.95 C8lifornia•resldenrs add til' wes faxP. O. Box 3072. Olive. CA 92665• DOWELSRe George Frank's reply to Michael McCann (FWW#22, May'SO, p. 21), I congratulate Mr. Frank on his ability to developstatistics on the relative risks of being poisoned by driers andbeing hit by a construction crane at home. I don't know ofany other source for such remarkable risk estimates. Moreseriously, being hit accidentally by a crane is something overC{j'wfEt QU EN ANNECabriole LegsWalnutHondurasMahoganyPenn. Cherryfrom solid3" stock,only the "ears"are glued on.Send 25< - Catalog Wo od PartsWOODWORKS Saginaw. TX 76179ISHEScORPBox 79<strong>23</strong>8RollingswoodOutstanding new book onwood identificationWritten by an expert foreveryone who wants apractical yet scientificway to identify the majorwoods of the Eastern U.S.The manual is well illustratedand has a valuable and usefulwood identification key.Order your copy now from:Colonial Hardwoods, Inc.212 N. West StreetFalls Church, Va. 22046Choosefrom sizesranging from7'14' slipper to29" table leg ...on (refundable purchase)Send $1.00for brochure.Box 404 Dept. FW4 Grays lake. IL. 60030WoodIdentificationComHandbool>men:: iald the Eastern United \\bods States,, t"Mar$hans.Whill"Only $5.95 plus $1.50 postage and handling.Master Charge and Visa accepted.Include number and expiration date.22

Q & A (continued)which one has little control. Being poisoned by a possibletoxic drier in a salad-bowl finish, however, is completely preventable.Further, I'm not the only one concerned about thematter. A distributor of these driers also advises against usingthem with items in which food or drink may be served .-Michael McCann, Center for Occupational Hazards,5 Beekman St. , New York, N. Y. 10038Several readers have responded to the request for informationabout finding parts and an owner's manual for a Walker-Turnerlathe, and we will send a fuzzy zerox to readers who askfor one. Rockwell Manufacturing Co. bought Walker-Turnerback in the early 1950s. Some parts for Walker-Turner machinesare still available; for specific information, writeRockwell Manufacturing Co. , Power Tool Div., 400 <strong>No</strong>rthLexington Ave. , Pittsburgh, Pa. 15208.Readers want to know:Henley Optical Co. , Reading, England, makes custom metalbodiedplanes. These tools COSt between $500 and $1,000. Doyou know of anyone who has a set of these planes or who hastested them and can comment on their performance? Anyphine that costs on the order of $1 ,000 must be a godsend tothose working with wild-grained wood.-Steven Goddard, West Grove, Pa.Supplies :-Casters and hardware for rolling library ladders: PutnamRolling Ladder Co., 32 Howard St., New York, N.Y. 10013.-Musical movements for over 800 melodies plus any tune forwhich you provide score. Special-order movements cost aboutIntroducingQuality Heirlooms12"x 12"x 41'."" HighByALONZIFURNITURECOM PANY• Easy toAssemble• ImportedCremo ItalianMarble• Ageless Classic Designs• Detailed Wood Carving• Completely Different& UniqueCatalogue-$ 1.00Refundable on first order.ALONZI FurnitureDept. CBixby, 0 K 74008$75. Write for catalog: World of Music Boxes, 412 Main St.,Avon, N.]. 07719.-Custom brass castings and furniture hardware: BergenPoint Brass Foundry, 179 W. 5th St., Bayonne, N.]. 07002.-Another source for Japanese hand tools: Anzen Hardwareand Supply, 220 E. 1st St., Los Angeles, Calif. 90012.-Antique icebox hardware: The Renovator's Supply, 71<strong>No</strong>rthfield Rd., Millers Falls, Mass. 01349.Readers can't find:I'm looking for a leather embossing tool that consists of along wooden handle and an electrically heated roller with thepattern engraved on it. I used one once that also had a dispenserfor the optional use of gold-backed tape for gildedembossing. -King Young, Highland, N. C.. . measured drawings or full-size plans for a cylinder desksimilar to the ones pictured in the <strong>No</strong>v. '78 issue of FineWoodworking.- Colon McNease, Jackson, Miss.·. . die-stamped steel or brass hardware for old-time steamertrunks.-John H. Mitchell, Memphis, Te nn... decorative copper hinges that extend about 10 in. overthe lid of a chest.-Richard Riddle, Ute, Iowa. . the hardware and mechanism for a desk typewriter lift.-Lyle Pelissier, Lafayette, La.· .. copper hinges and other hardware items for old kitchencupboards.-Phzl Regier, <strong>No</strong>rth Newton, Kan.Send quen'es, comments and sources of supply to Q&A, FineWoodworking, Box 355, Newtown, Conn. 06470.If you thought "Swiss-Precision" could only befound in watchmaking, then you don't knowabout our power tools. Only you know how good your tools haveto be. When it comes to woodworkingmachinery, they should be better than you areevenif you're already on accomplishedcraftsman. Therefore, you owe it to yourself tolearn more about our Swiss-made line of INCAstationary power tools which we sell throughoutthese 50 states.Ta ke the 10" Cabinetmaker's Saw, forexample. It has a 20mm (25/32") arbor at theblade for strength and rigidity where it counts .The table castings are toug h, prec ision milledalloys and the guide ra ils are aircraft qualityextrusions. All ,he major rotating parts aredynamically balanced. The battom line is amachine that takes hig her loadings and givesyau less vibration with a truer running sowblade.If fact, every one of our INCA saws, jointers,planers and shapers are built to qualitystandards which are becoming increasingly••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••hard to find in this country. That's because they'remade with the some pride of workmanshipas the Swiss put into their watches'l_raOur catalog is agood place to beg inyour comparisons.We want you to beas good as you ."can get.iii!Garrett161Wade Company, Dept. FW-7-80Ave. of Americas. New York. N.Y. 10013________________________(National Sales)Gentlemen,Send me your INCA catalog. Enclosed is $1.o Here's another $1 lor your lOB-page cotolog01__ _ __quality hand tools.Name'Address,City__ State__Zip<strong>23</strong>