Fishing capacity management and IUU fishing in Asia - FAO.org

Fishing capacity management and IUU fishing in Asia - FAO.org

Fishing capacity management and IUU fishing in Asia - FAO.org

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong><strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>RAP PUBLICATION 2007/16

RAP PUBLICATION 2007/16<strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>Gary M<strong>org</strong>an, Derek Staples<strong>and</strong>Simon Funge-SmithASIA-PACIFIC FISHERY COMMISSIONFOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONSREGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFICBangkok, 2007i

The designation <strong>and</strong> presentation of material <strong>in</strong> this publication do not imply the expression of any op<strong>in</strong>ionwhatsoever on the part of the Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concern<strong>in</strong>g the legalstatus of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>g the delimitation of its frontiers<strong>and</strong> boundaries.© <strong>FAO</strong> 2007NOTICE OF COPYRIGHTAll rights reserved. Reproduction <strong>and</strong> dissem<strong>in</strong>ation of material <strong>in</strong> this <strong>in</strong>formation product for educational orother non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyrightholders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material <strong>in</strong> this <strong>in</strong>formation product forsale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders.Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Senior Fishery Officer, <strong>FAO</strong> Regional Office for<strong>Asia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Pacific, Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Athit Road, Bangkok 10200, Thail<strong>and</strong>.For copies write to:The Senior Fishery Officer<strong>FAO</strong> Regional Office for <strong>Asia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the PacificMaliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Athit RoadBangkok 10200THAILANDTel: (+66) 2 697 4000Fax: (+66) 2 697 4445E-mail: <strong>FAO</strong>-RAP@fao.<strong>org</strong>ii

ForewordIn response to the recommendations of the 29 th Session of the <strong>Asia</strong>-Pacific Fishery Commission(APFIC) to assist members improve <strong>management</strong> of their <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>, APFIC Secretariatconvened a regional workshop on “Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> illegal, unreported <strong>and</strong>unregulated (<strong>IUU</strong>) <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Asia</strong>n region <strong>in</strong> Phuket, Thail<strong>and</strong>, from 19 to 21 June 2007. Thisreport has been commissioned as a background paper for this workshop to identify the major issuesfaced by APFIC Members.The report provides a regional synthesis based on responses to questionnaires sent to 15 countries <strong>in</strong>the region <strong>in</strong> addition to the previously available <strong>in</strong>formation. These focused on the current statusof the <strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> how countries <strong>in</strong> the region are address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>by both national <strong>and</strong> foreign fleets. The report shows that there were still many <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> over<strong>capacity</strong>issues <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>and</strong> that some progress to address these issues is be<strong>in</strong>g made. This <strong>in</strong>cludedthe formulation of National Plans of Action (NPOAs) on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> attempts to assess<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> implement <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> reduction programme <strong>in</strong> major fisheries, particularlysmall-scale fisheries.At the regional level, <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> both <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>and</strong> small-scale fisheries has cont<strong>in</strong>ued torise <strong>and</strong> production had also decreased <strong>in</strong> the majority of fisheries for which data were provided,<strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that the problem still pervades <strong>in</strong> the region. Identified problems <strong>in</strong>clude lack of policy<strong>and</strong> operational tools as a major constra<strong>in</strong>t to solv<strong>in</strong>g the problem, with only 50 percent of the majorfisheries hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>management</strong> plan. Very weak vessel licens<strong>in</strong>g systems <strong>and</strong> catch <strong>and</strong> effort datasystems <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g, control <strong>and</strong> surveillance (MCS) capabilities further hamper progress. <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> also rema<strong>in</strong>s a major issue <strong>in</strong> the region, with many Members identify<strong>in</strong>g illegal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> byboth national <strong>and</strong> foreign fishers <strong>in</strong> their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) as the ma<strong>in</strong> issues.This background report gives a clear picture of the need for action to address <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Asia</strong> region.He ChangchuiAssistant Director-General <strong>and</strong> Regional Representative<strong>FAO</strong> Regional Office for <strong>Asia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Pacificiii

Table of contentsExecutive summary ................................................................................................................Pagevii1. Introduction..................................................................................................................... 12. Methodology .................................................................................................................... 33. Fisheries <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> <strong>in</strong> APFIC countries................................................... 53.1 Have countries of the region identified <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues that require<strong>management</strong>? ........................................................................................................... 53.2 To what extent have national plans of action to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issuesbeen developed?....................................................................................................... 73.3 For what proportion of fisheries (<strong>in</strong>dustrial, mar<strong>in</strong>e artisanal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>) has<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> been assessed? ............................................................................... 83.4 What are the legislative <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional barriers to address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong><strong>in</strong> the region? ........................................................................................................... 103.5 Do countries of the region have the necessary tools <strong>in</strong> place to assess <strong>and</strong> manage<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> are those tools appropriate to the region? ............................... 133.6 What methods have been most commonly used <strong>in</strong> the region for <strong>capacity</strong>reduction? ................................................................................................................ 163.7 Have previous attempts at <strong>capacity</strong> reduction <strong>in</strong> specific fisheries beensuccessful? ............................................................................................................... 173.8 What progress has been made by countries of the region s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>? ...................................................................................................... 183.9 What plans do member countries have to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues with<strong>in</strong>the next five years? .................................................................................................. 204. <strong>IUU</strong> issues <strong>in</strong> APFIC countries ...................................................................................... 214.1 What are the greatest <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> issues reported by member countries? .............. 214.2 Where are vessels of the region that are engaged <strong>in</strong> foreign <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> operat<strong>in</strong>g? ..... 234.3 Do countries of the region control <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> other countries or on the highseas by their nationals? ............................................................................................ 244.4 To what extent have national plans of action been developed to address <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>? .................................................................................................................... 245. Conclusions...................................................................................................................... 266. References........................................................................................................................ 28v

Executive summaryThe <strong>Asia</strong>n region accounts for about 50 percent of global wild capture fisheries production <strong>and</strong>about 90 percent of aquaculture production. The susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong>management</strong> of these fisheriesresources, therefore, is an activity of global importance as well as be<strong>in</strong>g critical to countries of theregion. However, the history of exploitation of wild fish stocks of the region has been one ofsequential overexploitation, open access fisheries <strong>and</strong> low profitability. Despite this history, therehas been a grow<strong>in</strong>g recognition <strong>in</strong> recent years of the need to manage fish stocks for long-termsusta<strong>in</strong>ability. This regional synthesis summarizes <strong>in</strong>formation, based on responses to questionnairessent to 15 countries of the region <strong>and</strong> previously available <strong>in</strong>formation, on the current status of the<strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> how countries of the region are address<strong>in</strong>g illegal, unregulated<strong>and</strong> unreported (<strong>IUU</strong>) <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> by both national <strong>and</strong> foreign fleets.National Plans of Action (NPOAs) on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> the region are now more common than <strong>in</strong>2002 <strong>and</strong> some progress has been reported <strong>in</strong> attempt<strong>in</strong>g to assess <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> major fisheries,particularly small-scale fisheries. In addition, the number of specific <strong>capacity</strong> reduction programmesundertaken <strong>in</strong> the region has <strong>in</strong>creased s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002, aga<strong>in</strong> with the emphasis on small-scale fisheries.However, the effectiveness, on a regional scale, of these <strong>in</strong>itiatives is not yet apparent s<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> both <strong>in</strong>dustrial scale <strong>and</strong> small-scale fisheries has cont<strong>in</strong>ued to rise <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>and</strong> isnow, on average, 12.5 percent above 2002 levels. Production has also decreased <strong>in</strong> the majority offisheries for which data were provided. A lack of policy <strong>and</strong> operational tools <strong>in</strong> the region washighlighted by many countries, with only 50 percent of the major fisheries hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>management</strong>plans. Methods for measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>, such as vessel licens<strong>in</strong>g systems or census data, <strong>and</strong>catch <strong>and</strong> effort data systems are often be<strong>in</strong>g poorly developed <strong>and</strong> monitor<strong>in</strong>g, control <strong>and</strong>surveillance (MCS) capabilities generally <strong>in</strong>adequate. <strong>IUU</strong> rema<strong>in</strong>s a major issue to be addressedalthough the recent <strong>Asia</strong>-Pacific Fisheries Commission (APFIC) “call for action” <strong>and</strong> the RegionalPlan of Action for Responsible Fisheries, signed by 11 countries, may provide a template forregional action <strong>and</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ation on this.vii

1. Introduction<strong>Asia</strong> is the world’s largest producer of seafood, account<strong>in</strong>g for over 50 percent of global productionfrom wild capture fisheries as well as around 90 percent of global aquaculture production. As such,the <strong>management</strong> of wild capture fisheries <strong>in</strong> the region for long-term susta<strong>in</strong>ability is of globalsignificance as well as be<strong>in</strong>g of vital national <strong>in</strong>terest to the countries of the region because <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>activities account, <strong>in</strong> many countries, for a significant proportion of GDP <strong>and</strong> are often important <strong>in</strong>support<strong>in</strong>g large rural populations. Despite this importance, the history of exploitation <strong>and</strong><strong>management</strong> of wild fish resources <strong>in</strong> the region has generally not been good with stocks oftenbe<strong>in</strong>g overexploited both historically <strong>and</strong> also <strong>in</strong> recent times (for example, see Butcher, 2004 fora review of the history of sequential overexploitation <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dustrial mar<strong>in</strong>e fisheries of Southeast<strong>Asia</strong> <strong>and</strong> Sugiyama, Staples <strong>and</strong> Funge-Smith, 2004 for a review of the status of regional fisheries),fisheries that are usually characterized by open access <strong>and</strong> hence over<strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> low profitability<strong>and</strong> weak enforcement of fisheries regulations (see Box 1 for the benefits of better <strong>management</strong> offisheries).However, there has been a grow<strong>in</strong>g recognition with<strong>in</strong> the region that the rapid decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> fisheryresources over the past thirty to forty years must be curtailed <strong>and</strong> that there is a need to manage wildfisheries resources for long term susta<strong>in</strong>ability (see, for example, M<strong>org</strong>an, 2006). This is be<strong>in</strong>greflected <strong>in</strong> many countries by an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g emphasis on measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong><strong>and</strong> on controll<strong>in</strong>g illegal, unreported <strong>and</strong> unregulated (<strong>IUU</strong>) <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, both by nationals of coastalstates <strong>and</strong> also by foreign <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> fleets.The extent to which progress has been made by countries of the region <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g the key issuesof over<strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> was exam<strong>in</strong>ed as part of a workshop, <strong>org</strong>anized by the <strong>Asia</strong>-PacificFisheries Commission (APFIC) <strong>and</strong> held <strong>in</strong> Phuket, Thail<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> June 2007. As a background paperto this workshop, this regional synthesis has been prepared to provide <strong>in</strong>formation on progress <strong>and</strong>trends <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>in</strong> identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g actions on the major issues of over<strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> to provide an assessment of the effectiveness of these actions. This synthesis relieson <strong>in</strong>formation provided directly by the APFIC countries, which was requested from all countrydelegates as part of the prelim<strong>in</strong>ary work undertaken for the workshop. The <strong>in</strong>formation is thereforecurrent <strong>and</strong> provides a snapshot of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> issues which has not previously beenavailable.It is anticipated that the <strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this regional synthesis will provide the necessarybackground for identify<strong>in</strong>g the major issues related to <strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> for develop<strong>in</strong>g specific action plans at both national <strong>and</strong> regional level.1

Box 1: A required paradigm shift – the benefits of improved <strong>management</strong> of mar<strong>in</strong>ecapture fisheries1. Poor <strong>management</strong> of fisheries is currently result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>:● Harvest<strong>in</strong>g overcapacities● Decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g catch per unit of effort● Change <strong>in</strong> catch composition towards short-lived low-value species● Non-selective <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> gear types becom<strong>in</strong>g advantageous relative to selective <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> gear● A grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tensity of the “race for fish”● A proliferation of <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>● Technological progress that is targeted on <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g catch <strong>in</strong> quantity rather than <strong>in</strong> value● Fishers who operate under economically marg<strong>in</strong>al conditions● Low-value fish that becomes a critical share of revenue to make ends meet● Post-harvest value addition severely impaired2. Management that is focused on maximiz<strong>in</strong>g the economic potential of capture fisheries would result<strong>in</strong>:● Reduced growth <strong>and</strong> recruitment over<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>and</strong> lowered ecosystem impacts● Restored species diversity● Better quality <strong>and</strong> higher value of catch● Reduced <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> costs● Greater net benefits to society at large● Potential to redistribute fishery benefits to meet social objectives● Greater value addition <strong>in</strong> post-harvest sector3. A Global Rent Dra<strong>in</strong> study be<strong>in</strong>g undertaken by <strong>FAO</strong> has shown that, by reduc<strong>in</strong>g global <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>effort from the present 13.9 m GRT to 7.3 m GRT, the follow<strong>in</strong>g would be achieved:● Increase <strong>in</strong> harvest from 85 to 93 million tonnes● Increase <strong>in</strong> fish biomass from 123 to 254 million tonnes● Increases <strong>in</strong> operational profits from the present loss of US$5.3 billion to a profit ofUS$41.6 billion● Increase <strong>in</strong> rents generated from the present zero US$50.8 billion4. To achieve this paradigm shift of mov<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>management</strong> which maximises benefits rather thanl<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, there is a need to:● Invest more <strong>in</strong> fisheries <strong>management</strong> <strong>in</strong> order to capture the benefits● Change the focus of debate form quantity to value● Establish basel<strong>in</strong>es for measur<strong>in</strong>g the economic health of the world’s fisheries● Raise awareness through target<strong>in</strong>g a broader set of national policy-makers <strong>and</strong> deliver<strong>in</strong>g thebenefits of the change to major global <strong>and</strong> regional fora5. The practical issues that need to be addressed <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g this paradigm shift <strong>in</strong> fisheries<strong>management</strong> are:● High upfront economic <strong>and</strong> political costs versus long-run benefits● Low activity <strong>and</strong> marg<strong>in</strong>al vessels easiest to encourage to exit the fishery● Where fishery access cannot be made exclusive through rights-based <strong>management</strong> regimes, highrisk of re-<strong>in</strong>vestments● Concepts of cost-recovery <strong>and</strong> payment of resource rentals are hard to sellSource: Adapted from “Economic considerations <strong>in</strong> the <strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>”, presentation by Rolf Willmannat the APFIC Regional consultative workshop on Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Capacity <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, Phuket, June 2007.2

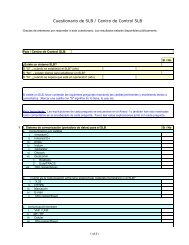

2. MethodologyUp to date <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> is notoriously difficult to access becausemuch of the <strong>in</strong>formation is held with<strong>in</strong> country M<strong>in</strong>istries <strong>and</strong> is not often published <strong>in</strong> media thatis widely available. The approach that has been used for this synthesis has been to developa questionnaire that was sent to each of the APFIC member countries prior to the June 2007workshop request<strong>in</strong>g current <strong>in</strong>formation on issues related to <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, <strong>and</strong> how the various countries were deal<strong>in</strong>g with these issues. The questionnaire that wasdistributed was designed to build on <strong>in</strong>formation that was already available, particularly that fromprevious surveys by <strong>FAO</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2003 (De Young, 2006) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation collected from selectedcountries by the University of British Columbia, Canada, <strong>in</strong> 2006 (Pitcher, Kalikoski <strong>and</strong>Ganapathiraju, 2006). To ensure this connection with previous work, the questionnaires requested<strong>in</strong>formation on specific fisheries for each country, which were the three largest, by quantity, <strong>in</strong>dustrialscale fisheries <strong>and</strong> the three largest artisanal fisheries. These fisheries were, <strong>in</strong> most cases, the samefisheries for which countries reported to <strong>FAO</strong> <strong>in</strong> 2003 <strong>and</strong> therefore updated <strong>in</strong>formation wasgathered on what progress had been made <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> issues s<strong>in</strong>ce thattime. While recogniz<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> had beentaken <strong>in</strong> a number of countries for a large number of fisheries, the questionnaire’s concentration onthe three largest <strong>in</strong>dustrial-scale <strong>and</strong> artisanal fisheries <strong>in</strong> each country ensured that the overall scale<strong>and</strong> impact of actions that had been taken by countries to address these issues were fully taken <strong>in</strong>toaccount.The questions with<strong>in</strong> the questionnaire were also specifically designed to gather quantitative dataon the extent of fisheries over<strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> each country with a clear separationbetween fisheries <strong>in</strong> which nationals of the country were the ma<strong>in</strong> producers <strong>and</strong> fisheries that wereprimarily undertaken by foreign vessels. Questionnaires were sent to 15 member countries ofAPFIC (ten countries submitted responses). Data from the ten responses has, therefore, been usedto develop a regional picture of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> issues, while recogniz<strong>in</strong>g that the pictureis <strong>in</strong>complete because of the miss<strong>in</strong>g (five countries) responses. As such this review can beconsidered an ongo<strong>in</strong>g review <strong>and</strong> a contribution to our overall underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues <strong>in</strong> the region.In addition to some countries not be<strong>in</strong>g able to provide <strong>in</strong>formation, a further note of caution shouldbe added <strong>in</strong> us<strong>in</strong>g the available questionnaire responses for any def<strong>in</strong>itive <strong>in</strong>ter-country comparisonsregard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> issues. Inevitably, questionnaires responses may becompiled by different personnel <strong>in</strong> different Government agencies, each with their own <strong>in</strong>dividual,<strong>and</strong> sometimes limited, perspective on the issues be<strong>in</strong>g addressed. As such the responses mayreflect these <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>and</strong>/or agency perspectives rather than provide a broader view. This is nota criticism of the diligence with which <strong>in</strong>dividuals have provided <strong>in</strong>formation for this work butrather an observation that <strong>in</strong>evitably limits the value of questionnaire responses, no matter where orby whom they are collected.Analysis of the responses to the questionnaire was, however, undertaken so as to address a numberof key questions related to <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the region. These questions were:A. Management <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>●●●Have countries of the region identified <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues that require <strong>management</strong>?To what extent have national plans of action to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues beendeveloped?For what parts of the national fishery sector (<strong>in</strong>dustrial, mar<strong>in</strong>e artisanal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>) has<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> been assessed?3

●●●●●●What are the legislative <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional barriers to address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>?Do countries of the region have the necessary tools <strong>in</strong> place to assess <strong>and</strong> manage <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> are the tools be<strong>in</strong>g used relevant to the issues <strong>in</strong> the region?What methods have been most commonly used <strong>in</strong> the region to date for <strong>capacity</strong>reduction?Have previous attempts at <strong>capacity</strong> reduction been successful?What progress has been made by countries of the region s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 <strong>in</strong> implant<strong>in</strong>gspecific actions to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues?What plans do member countries have to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues with<strong>in</strong> the nextfive years?B. Address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>IUU</strong> issues●●●●What is the extent of <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>and</strong> what changes have occurred s<strong>in</strong>ce2002? What are the ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> issues reported by member countries?Where are the region’s foreign <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> fleets <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>? In other EEZs or on the high seas?Do countries of the region control <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> other countries or on the high seas bytheir nationals?To what extent have national plans of action been developed to address <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>?4

3. Fisheries <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> <strong>in</strong> APFIC countries3.1 Have countries of the region identified <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues that require<strong>management</strong>?Of the ten responses received, n<strong>in</strong>e countries reported that they had identified <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>issues that required <strong>management</strong> (Table 1) 1 . All of the identified <strong>capacity</strong> issues related toover<strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> some form or other <strong>in</strong> specific fisheries (see Box 2 for further <strong>in</strong>formation onoptimal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>) <strong>and</strong> were usually a legacy of open-access arrangements.Table 1: The current situation <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>in</strong> recogniz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> tak<strong>in</strong>g action on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> issuesNPOA on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>Percentage of fisheriesCapacity developed? Date? If No, Steps already taken where <strong>capacity</strong> has beenissues are there plans to develop to reduce <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> assessed (a) large-scaleidentified? an NPOA with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>capacity</strong>? <strong>in</strong>dustrial (b) artisanalnext 5 years?mar<strong>in</strong>e (c) <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>Australia Y Y – 2001 Y (a) 75-100 percent(b) 75-100 percent(c) n/aBangladesh Y Y – 2006 Y (a) 75-100 percent(b) 25-50 percent(c) 0-25 percentCambodia Y Y – 2005/08 N (a) 0-25 percent(b) 50-75 percent(c) 50-75 percentIndonesia Y Y – 2006 Y No dataMalaysia Y Y – to be completed Y No data<strong>in</strong> 2007Pakistan Y N – plan to develop Y (a) 50-75 percentNPOA with<strong>in</strong> 5 years (b) 50-75 percent(c) 50-75 percentPhilipp<strong>in</strong>es Y N – plan to develop Y (moratorium on the (a) 50-75 percentNPOA with<strong>in</strong> 5 years issue of new licenses – (b) 25-50 percentreduction by attrition) (c) 25-50 percentSri Lanka N N – no plans to develop N (d) n/aan NPOA with<strong>in</strong> the (e) 50-75 percentnext 5 years (f) 25-50 percentThail<strong>and</strong> Y Y – ongo<strong>in</strong>g Y, <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>and</strong> (a) 50-75 percentartisanal fisheries but (b) 25-50 percentnot <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> (c) 0-25 percentViet Nam Y N – plan to develop N (a) n/aNPOA with<strong>in</strong> 5 years (b) 50-75 percent(c) 0-25 percentIn three <strong>in</strong>dustrial-scale fisheries, the identified <strong>capacity</strong> issues were related to changes <strong>in</strong> theefficiency of <strong>in</strong>dustrial vessels over time, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>in</strong>teractions with small-scale fisheries whoshared the same stock, rather than significant changes <strong>in</strong> the number of vessels.1In addition, Ch<strong>in</strong>a has reported (this workshop) that it has identified <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues <strong>and</strong> is manag<strong>in</strong>g them.5

Box 2: What is ‘Optimal <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Capacity’?1. The ‘optimal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>’ depends on the <strong>management</strong> objectives. These can be:● Biological/ecological, such as maximum susta<strong>in</strong>able yield● Social such as provid<strong>in</strong>g a social safety net or maximiz<strong>in</strong>g employment● Economic such as maximum profits, perhaps from non-consumptive uses such as Ecotourism.2. However, these three objectives are not <strong>in</strong>dependent. For example, economic objectives (such asimprov<strong>in</strong>g profitability) can significantly impact on social objectives (such as poverty alleviation)<strong>and</strong> vice versa.3. In practice, ‘optimal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>’ will be that <strong>capacity</strong> that takes <strong>in</strong>to account all of theseobjectives. There is therefore no “ideal” <strong>capacity</strong> that can be applied to all situations – each fisheryshould def<strong>in</strong>e its own objectives <strong>and</strong> the appropriate <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> to achieve those objectives.4. Biological objectives are critical s<strong>in</strong>ce the resource on which the fishery is based is the foundationfor other objectives. These biological objectives should be orientated towards ensur<strong>in</strong>g a susta<strong>in</strong>ablefish resource <strong>in</strong> the longer term. To ensure such susta<strong>in</strong>ability, the biological objectives may need to<strong>in</strong>clude ecosystem <strong>management</strong> issues to ensure that the mar<strong>in</strong>e ecosystem upon which the fishresource depends is also protected.5. Economic objectives are important if the exploitation of the fish resource is to be done <strong>in</strong> a way thatgenerates profits <strong>and</strong> economic rent. In unmanaged, open-access fisheries, economic rent is usuallynear zero <strong>and</strong> profits from <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imal. In such fisheries, particularly if they are small scale,this low profitability can often contribute significantly to poverty.6. The <strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> also needs to take <strong>in</strong>to account social issues, both <strong>in</strong> terms ofspecific social objectives (such as employment or poverty alleviation) <strong>and</strong> also the social impacts<strong>and</strong> appropriateness of implement<strong>in</strong>g <strong>management</strong> changes.7. In <strong>Asia</strong>, def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the objectives of <strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong> of optimal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> is vital, given thegeneral state of fisheries of be<strong>in</strong>g overexploited <strong>and</strong> with low profitability.8. The scale of the problem is also significant <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>. Nearly 88 percent of an estimated 41 m people(or 36.28 m) work<strong>in</strong>g full-time or otherwise as fishers <strong>in</strong> the world are <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong> (<strong>FAO</strong> 2007). Most ofthese are employed <strong>in</strong> small-scale or artisanal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>.9. Therefore, solutions to def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>management</strong> objectives (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g optimal <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>) <strong>and</strong>implement<strong>in</strong>g actions to achieve those objectives should consider the social context <strong>in</strong> which theyare operat<strong>in</strong>g. For example, it may not be appropriate to implement <strong>management</strong> arrangements thatstress <strong>in</strong>dividual rights <strong>and</strong> do not fit the collective <strong>and</strong> cultural ethos of <strong>Asia</strong>n countries.Source: Adapted from “Scientific evidence – status of resources <strong>and</strong> optimal <strong>capacity</strong>” by Derek Staples <strong>and</strong>presentation “Social implications of <strong>capacity</strong> reduction” presentation by Ch<strong>and</strong>rika Sharma at the APFIC Regionalconsultative workshop on Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Capacity <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, Phuket, June 2007.In essence, therefore, the <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues that countries have identified relate to the significantproblems associated with mov<strong>in</strong>g from essentially open-access fisheries (which have been the mostcommon form of fisheries <strong>in</strong> the region) to some type of limited or restricted entry. However, thefirst pre-requisites for effective limitation of entry <strong>and</strong> control of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> of (1) a method,such as a vessel registration <strong>and</strong> licens<strong>in</strong>g system or vessel census data, for measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> all fisheries with associated enforcement <strong>and</strong> (2) reliable catch <strong>and</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> effort<strong>in</strong>formation, have often not been met <strong>in</strong> many countries, particularly for small scale fisheries(see Table 3).6

Unless these pre-requisites are addressed, <strong>in</strong>itiatives to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues may not besuccessful. Only five countries of eight who reported (63 percent) stated that more than 90 percentof <strong>in</strong>dustrial vessels were actually registered while only two countries of n<strong>in</strong>e (22 percent) reportedthat more than 90 percent of small-scale, artisanal vessels were registered 2 . Vessel registrationsystems <strong>in</strong> the region therefore appear generally <strong>in</strong>effective <strong>and</strong> therefore may not be useful tool forthe essential measurement of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>. To implement <strong>and</strong> measure the impact of any<strong>capacity</strong> limitation <strong>in</strong>itiative under these circumstances will be extremely difficult, unless eitherthe vessel registration systems are made more robust or alternative measures of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>(e.g. a regular census of vessels) are adopted. It is likely that the most appropriate tool formeasurement of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> the region will be different for large-scale, <strong>in</strong>dustrial vessels(where vessels registration systems are already reasonably well developed) than for small-scalefisheries where other methods such as vessel census may be more appropriate.One approach to manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>capacity</strong> reported by some countries was the imposition of a ban on theissue of new vessel licenses <strong>and</strong> to reliance on attrition to reduce the numbers of vessels <strong>in</strong> a fishery.However, unless this is accompanied, at least, by a robust vessel registration process <strong>and</strong> goodcontrol <strong>and</strong> surveillance (both of which are often lack<strong>in</strong>g), such an approach is unlikely to beeffective <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>, s<strong>in</strong>ce the most likely result would simply be an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> thenumber of unregistered vessels.Conclusion: The vast majority of countries of the region have now recognized <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> asan issue that requires <strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong> that there is a need to move from open access fisheries tosome type of restricted or controlled entry. However, the essential pre-requisites for restrict<strong>in</strong>g orcontroll<strong>in</strong>g entry (particularly <strong>in</strong> small-scale, artisanal fisheries) of enforceable vessel <strong>and</strong> fisherregistration systems <strong>and</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> effort data collection systems are not yet <strong>in</strong> place <strong>in</strong> many countries<strong>and</strong> therefore it is likely that <strong>in</strong>itiatives to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues will not be successful.Moreover, the common absence of these registration <strong>and</strong> data collection systems may also meanthat measur<strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness (if any) of <strong>capacity</strong>-reduction <strong>in</strong>itiatives will be extremely difficult.3.2 To what extent have national plans of action to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issuesbeen developed?Of the ten responses received, six countries have already developed NPOAs to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> with a further three countries plann<strong>in</strong>g to develop these with<strong>in</strong> the next five years (Table 1).Several of these NPOAs have been developed with<strong>in</strong> the last few years (Table 2). Unfortunately,copies have not been provided to <strong>FAO</strong>, <strong>and</strong> casts some doubt on the accuracy of report<strong>in</strong>g on thisitem. It suggests that the questionnaire approach <strong>and</strong> differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation of what constitutesan NPOA may over state the extent to which NPOAs have actually been developed. An example ofthis is a country response to a questionnaire <strong>in</strong> 2003 that an NPOA had been developed, but a morerecent response <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that it now has no NPOA <strong>and</strong> has no plans to develop one.Table 2 provides <strong>in</strong>formation, based on responses from the questionnaires, as to how activity <strong>in</strong> thedevelopment of NPOAs on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> has changed s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002. In the current survey,66 percent of countries stated that they had already developed an NPOA on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>, witha further 25 percent stat<strong>in</strong>g they were plann<strong>in</strong>g to develop one with<strong>in</strong> the next five years. This isa marked improvement over the situation <strong>in</strong> 2002 where only 40 percent of countries stated thatthey would meet a 2005 deadl<strong>in</strong>e for hav<strong>in</strong>g an NPOA on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> place. Table 2 also2The measurement of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> small-scale fisheries is a particular problem <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>, given the large number ofvessels <strong>and</strong> their wide distribution. The methods used to measure <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> such fisheries (for example, by regularcensus methods) may be quite different from that used to measure <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries, such as robust <strong>and</strong>enforceable vessel licens<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> registration systems.7

Table 2: Reported progress <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g National Plans of Actions on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong>reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>Three largest <strong>in</strong>dustrialThree largest artisanalNPOA on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>? fisheries – steps taken to reduce fisheries – steps taken to reduce<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>? <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>?2003 40 percent of countries 31 percent of fisheries 16 percent of fisheries2007 66 percent of countries have 36 percent of fisheries 33 percent of fisheriesdeveloped NPOAs. A further25 percent have plans todevelop NPOA with<strong>in</strong> 5 yearsdemonstrates that practical implementation of <strong>capacity</strong> reduction measures has been undertaken <strong>in</strong>33 percent of small-scale fisheries (see Box 3 for a summary of small-scale fishers views on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> issues), compared with only 16 percent <strong>in</strong> 2002, although the proportion of large<strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries that have been the subject of <strong>capacity</strong> reduction <strong>in</strong>itiatives has rema<strong>in</strong>ed aboutthe same. In addition to the progress on NPOAs reported, Ch<strong>in</strong>a has also developed a NPOA onreduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> through vessel buy-back schemes (Pitcher, Kalikoski <strong>and</strong> Ganapathiraju,2006).Conclusion: Significant progress has been made <strong>in</strong> the region s<strong>in</strong>ce 2003 <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g nationalapproaches to the <strong>management</strong> of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>. This has <strong>in</strong>cluded actual implementation of<strong>capacity</strong> reduction programmes, particularly <strong>in</strong> small-scale fisheries. The effectiveness of these<strong>capacity</strong> reduction programmes will be further exam<strong>in</strong>ed below. However, <strong>in</strong> some countries thererema<strong>in</strong>s the question of what has actually been done <strong>in</strong> support of implementation of the NPOA <strong>and</strong>whether such NPOAs are seen as just paper documents or are used to guide <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>itiate concreteactions to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>.3.3 For what proportion of fisheries (<strong>in</strong>dustrial, mar<strong>in</strong>e artisanal <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>) has<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> been assessed?Of ten countries that responded, eight were able to give estimates of the proportion of their fisheriesthat had been the subject of <strong>capacity</strong> assessment. The results are shown <strong>in</strong> Table 1 <strong>and</strong> Figure 1.From these limited figures, it appears that attention has generally been paid to the assessment of<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries (where they exist) with <strong>capacity</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g been assessed <strong>in</strong> anaverage of 62.5 percent of major <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries <strong>in</strong> the respondent’s countries. Although progresshas generally been made s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 (see above), artisanal fisheries have received the most attention<strong>in</strong> recent years (see below), although <strong>capacity</strong> has still been assessed <strong>in</strong> only 54.7 percent of majorartisanal fisheries. Inl<strong>and</strong> fisheries have not received very much attention at all with <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> hav<strong>in</strong>g been assessed <strong>in</strong> only 33.1 percent of major <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries. In 2002, countries 3reported that they had a process for measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> 71 percent of their three largest<strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries although <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> was measured <strong>in</strong> only 33 percent of the three largestsmall-scale artisanal fisheries. While there was no data collected for <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries dur<strong>in</strong>g the2002 survey, <strong>capacity</strong> measurement may be difficult <strong>in</strong> many <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries of the region 4 .Conclusion: The assessment of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> appears to have been given some attention s<strong>in</strong>ce2003 with most countries report<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> has been assessed <strong>in</strong> the majority of<strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries <strong>and</strong> about half of small-scale, artisanal fisheries. However, little attention has3A larger sample of countries, consist<strong>in</strong>g of all APFIC members.4Also, there are relatively few examples of <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries so that most <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries <strong>in</strong> the region are artisanal<strong>in</strong> nature which, generally, have not been addressed so far as <strong>capacity</strong> measurement is concerned.8

Box 3: What the fishers are say<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> Southeast<strong>Asia</strong>1. The fisheries of Southeast <strong>Asia</strong> are characterized by:● Complex coastal development <strong>and</strong> <strong>management</strong>● Conflicts among various aquatic resource users● A wide range of projects/<strong>in</strong>itiatives <strong>and</strong> cooperation on fisheries at various levels● Well recognized signs <strong>and</strong> different extent of over<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, decl<strong>in</strong>ed fishery resources,over<strong>capacity</strong>, destructive <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>2. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to a study by SEAFDEC (this workshop), the fishers op<strong>in</strong>ions are that:● There is unfair competition between large-scale <strong>and</strong> small-scale fishers● Fisheries conflict is a symptom but not a root cause of poor <strong>management</strong> – over<strong>capacity</strong> & <strong>IUU</strong><strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> has resulted from <strong>in</strong>effective <strong>management</strong> framework● Laws, regulations <strong>and</strong> rules are complicated <strong>and</strong> their enforcement is poor● There is a lack of an access regulatory system to provide certa<strong>in</strong>ty of access● Institutional arrangement are poor – there are too many agencies chas<strong>in</strong>g fishers● There is a lack of clear <strong>management</strong> policies <strong>and</strong> frameworks that are clear, coherent, areupdated regularly <strong>and</strong> have cont<strong>in</strong>uity.3. As a result, there has been:● A “Back Fire” of <strong>management</strong> as a result of shift<strong>in</strong>g problems from long-term objectives toachiev<strong>in</strong>g short-term ga<strong>in</strong>s● Offshore fisheries development● A failure to identify acceptable alternative livelihoods for displaced fishers who are will<strong>in</strong>g toleave a fishery● An underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of social structures by <strong>management</strong> attempts although the community role <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>volvement is usually well recognized● Some good <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>itiatives but there is a lack of cont<strong>in</strong>uity <strong>and</strong> scal<strong>in</strong>g up4. The key regional directions that are therefore required are:● “Indicators” – a better tool for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of <strong>and</strong> communication about the status <strong>and</strong> trendsof tropical fisheries● Co-<strong>management</strong> <strong>and</strong> rights-based fisheries (<strong>in</strong>troduction of group-user rights <strong>and</strong> improvementof licens<strong>in</strong>g systems)● “Freez<strong>in</strong>g” <strong>and</strong> control number of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> vessels● Strengthen<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g regional collaborative framework to support national <strong>management</strong>,perhaps by the establishment of a Regional Scientific Advisory Committee for FisheriesManagement <strong>in</strong> Southeast <strong>Asia</strong>.● Such a body could coord<strong>in</strong>ate data <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation, undertake <strong>and</strong> commission regional strategicresearch <strong>and</strong> package recommendations <strong>in</strong> the form of policy brief <strong>and</strong> guidel<strong>in</strong>es5. The role of SEAFDEC <strong>and</strong> APFIC would need to be def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> contribut<strong>in</strong>g to these <strong>in</strong>itiatives.Source: Adapted from “Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Asia</strong>” presentation by Suriyan Vichithekarn atthe APFIC Regional consultative workshop on Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Capacity <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, Phuket, June 2007.9

Percent1009080706050403020100Australia Bangladesh Cambodia Pakistan Philipp<strong>in</strong>es Sri Lanka Thail<strong>and</strong> Viet NamIndustrialSmall-scaleInl<strong>and</strong>Figure 1: The percentage of the three largest <strong>in</strong>dustrial, small-scale <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries <strong>in</strong>each country where <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> has been reported to have been assessedbeen paid to the assessment of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries. Therefore, the situation withregard measur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries does not seem to have changed significantlys<strong>in</strong>ce 2002, although there seems to have been <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the number of small-scale fisherieswhere <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> is be<strong>in</strong>g measured 5 . The proportion of small-scale fisheries for which <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> has been assessed is, however, still only about 50 percent, compared with about 62 percentfor <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries but only 33 percent for <strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong> fisheries.3.4 What are the legislative <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>stitutional barriers to address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong>the region?A review of fisheries legislation <strong>in</strong> the region <strong>in</strong> 2006 (M<strong>org</strong>an, 2006) showed that 56 percent ofcountries of the region did not have the legislative ability with<strong>in</strong> their national fisheries laws to limitthe number of licenses issued to fishers <strong>and</strong>/or vessels. However, of the ten countries that respondedto the current questionnaire, only two responded that they did not have such legislative powers forboth <strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>and</strong> small-scale, artisanal fisheries (Table 3a <strong>and</strong> 3b). This discrepancy may be dueto the extent of adm<strong>in</strong>istrative powers with<strong>in</strong> national legislation 6 . The ability to limit licenses iscritical to address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>capacity</strong> issues <strong>and</strong> countries that do not have these powers should beencouraged to review their relevant legislation.Management plans, which often have a formal legal status 7 , (see below), are becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>glycommon <strong>in</strong> most countries. Of the ten respondents, eight reported that they had developed<strong>management</strong> plans for their major <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries (Table 3a). However, <strong>management</strong> plans aremuch less common for small-scale fisheries (Table 3b) with only four countries report<strong>in</strong>g that theyhave these <strong>in</strong> place for their largest small-scale, artisanal fisheries. This contrasts with responses <strong>in</strong>2003, when only two countries reported that they had developed <strong>management</strong> plans for any fishery.It is, however, important that <strong>management</strong> plans for any fishery <strong>in</strong> the region are actually used toguide implementation of <strong>management</strong> measures <strong>and</strong> are widely dissem<strong>in</strong>ated. In this regard, it isencourag<strong>in</strong>g that, of the fisheries that were reported as hav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>management</strong> plans, 86 percent ofthese <strong>management</strong> plans were reported as hav<strong>in</strong>g a formal legal status although <strong>in</strong> 35 percent of5Although this is based on a limited sample of countries.6Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> India also reported at the workshop that they have the power, at either national or state (prov<strong>in</strong>cial) level to limitlicence numbers <strong>and</strong> have used these powers <strong>in</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> programmes.7S<strong>in</strong>ce some countries are still us<strong>in</strong>g fisheries legislation which dates back more than thirty years, revis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> reform<strong>in</strong>g thelegislation is an essential accompany<strong>in</strong>g activity to <strong>in</strong>troduction of <strong>management</strong> measures.10

Table 3: A summary of tools available to address <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> issues11(a) In the three largest <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries:National or Vessels Fishermen <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> gear Catch <strong>and</strong> effort Management Laws allow licenseforeign vessels? registered? registered? licensed? statistics collected? plans <strong>in</strong> place? limitation?Australia 100 percent national >90 percent >90 percent Y Y Y Yregistered registeredBangladesh (1) 70–90 percent national >90 percent >90 percent (1) N Y Y Y for both fishers(2) 100 percent national registered registered (2) Y <strong>and</strong> boatsCambodia 100 percent national (1) 30–50 percent (1) 30–50 percent 30–50 percent Y Y Y for both fishersregistered registered licensed <strong>and</strong> boats(2) 50–70 percent (2) 50–70 percentregistered registered(<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>)(<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>)Indonesia (1) 100 percent national >90 percent >90 percent >90 percent Y (1) Y Y for both fishers(2) 100 percent national registered registered licensed (2) be<strong>in</strong>g drafted <strong>and</strong> boats(3) >90 percent national (3) <strong>in</strong> draftMalaysia 100 percent national >90 percent 70–90 percent >90 percent Y N Y for both fishersregistered registered licensed <strong>and</strong> boatsPakistan (1) 100 percent national >90 percent Not fisheries N Y N N for both fishers(2) >90 percent national registered specific <strong>and</strong> boats(3) 100 percent nationalPhilipp<strong>in</strong>es (1) 100 percent national 70–90 percent 70–90 percent 70–90 percent (1) Y (1) N Y for both fishers(2) 100 percent national registered registered but not licensed (2) N (2) Y <strong>and</strong> boats(3) 100 percent national fisheries specific (3) Y (3) YThail<strong>and</strong> 100 percent national 70–90 percent Not fisheries (1) 70–90 percent Y Y N for fishers,registered specific licensed Y for boats(2) >90 percentlicensed

12(b) In the three largest artisanal fisheries:National or Vessels Fishermen <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> gear Catch <strong>and</strong> effort Management plans Laws allow licenseforeign vessels? registered? registered? licensed? statistics collected? <strong>in</strong> place? limitation?Bangladesh 100 percent 10–30 percent Not fisheries N N N Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered specific boatsCambodia 100 percent 30–50 percent 30–50 percent 30–50 percent Y Y Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered registered registered boatsIndonesia 100 percent >90 percent Y Y Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered boatsMalaysia 100 percent 70–90 percent 70–90 percent 70–90 percent Y N Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered registered licensed boatsPakistan 100 percent >90 percent Not fisheries N N N N for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered specific boatsPhilipp<strong>in</strong>es 100 percent 50–70 percent Not fisheries (1) 30–50 percent Y (1) Y Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered specific licensed (2) N boats(2) & (3) not (3) Yfisheries specificSri Lanka 100 percent 70–90 percent Y 70–90 percent N N Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered licensed boatsThail<strong>and</strong> 100 percent (1) 70–90 percent Not fisheries (1) 70–90 percent Y Y N for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered specific licensed boats(2) N (<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>) (2) 50–70 percentlicensed (<strong>in</strong>l<strong>and</strong>)Viet Nam 100 percent 50–70 percent 30–50 percent 50–70 percent Y N Y for both fishers <strong>and</strong>national registered registered licensed boats

fisheries with <strong>management</strong> plans, there were no actual published regulations 8 . This would thereforesuggest, at least <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances, that <strong>management</strong> plans are be<strong>in</strong>g seen as policy statements of<strong>in</strong>tent rather than <strong>management</strong> tools.A further trend <strong>in</strong> the region seems to be the move towards clarification of national policy onfisheries <strong>management</strong> generally <strong>and</strong> limitation of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>in</strong> particular. Althoughimplementation of such <strong>management</strong> policy is often carried out at regional or prov<strong>in</strong>cial level, therehas been reported an improved coord<strong>in</strong>ation between national policy-sett<strong>in</strong>g agencies <strong>and</strong> localimplementation agencies. Such trends enable greater consistency <strong>in</strong> the application of fisheriespolicy. Most countries (78 percent) reported that they had formal coord<strong>in</strong>ation mechanisms <strong>in</strong> placebetween national <strong>and</strong> regional authorities to implement fisheries regulations <strong>and</strong> provide monitor<strong>in</strong>g,control <strong>and</strong> surveillance activities.Conclusion: Most countries have reported or demonstrated that they have the legislative powers tolimit <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>. Management Plans for specific fisheries (which should provide guidance on<strong>capacity</strong> issues) are becom<strong>in</strong>g more common <strong>in</strong> the region for <strong>in</strong>dustrial fisheries although they arestill not commonly used for small-scale, artisanal fisheries. Appropriate legislative powers <strong>and</strong>support<strong>in</strong>g Management Plans for specific fisheries are critical <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong>provid<strong>in</strong>g a strategic context for long-term <strong>management</strong>. Therefore, those countries that do nothave the legislative powers or specific fisheries Management Plans should be encouraged to reviewtheir legislation <strong>and</strong> to develop Management Plans.3.5 Do countries of the region have the necessary tools <strong>in</strong> place to assess <strong>and</strong> manage<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> are those tools appropriate to the region?To develop appropriate policy <strong>and</strong> to implement, where necessary, <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> or <strong>capacity</strong>reduction programmes, there is a range of tools that are necessary. For policy formulation <strong>and</strong>implementation on <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> with<strong>in</strong> any fishery, these tools are essentially (a) robust data oncurrent production <strong>and</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> measurement with<strong>in</strong> the fishery (b) clear <strong>capacity</strong> targets <strong>and</strong> anunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g, usually from research programmes, of the biological, economic <strong>and</strong> social impactsof those targets (c) a data collection system that allows the collection of relevant data on the fisheryso that the progress <strong>and</strong> impact of <strong>capacity</strong> changes can be measured <strong>and</strong> monitored over time (d) aneffective monitor<strong>in</strong>g, control <strong>and</strong> surveillance capability to ensure the policy rules are followed <strong>and</strong>(e) political <strong>and</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istrative support to carry the implementation through to completion.Ten respondents to date have provided <strong>in</strong>formation on to what extent these policy tools are availablewith<strong>in</strong> the region <strong>and</strong> Table 3 provides a summary of this <strong>in</strong>formation.As noted above, there has been significant progress <strong>in</strong> the development of <strong>management</strong> plans for<strong>in</strong>dustrial <strong>and</strong> artisanal fisheries of the region, although there rema<strong>in</strong>s a question of whether suchplans are actually be<strong>in</strong>g used <strong>in</strong> all countries as a <strong>management</strong> tool to guide long-term strategicdirections for fisheries <strong>management</strong>. In two countries, <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>management</strong> was legislativelyextremely difficult because national legislation did not allow the limitation of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> licenses.Although some type of vessel <strong>and</strong> fisher registration system is reported to be <strong>in</strong> place <strong>and</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>effort statistics were be<strong>in</strong>g collected for most of these major fisheries, the accuracy of some of thesestatistics must be questioned because a number of countries reported that up to 80 percent of vessels<strong>and</strong> the fishers that were <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> were unregistered. The <strong>in</strong>effectiveness of licens<strong>in</strong>g systems(<strong>and</strong> data collection on l<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>) was most acute <strong>in</strong> small-scale fisheries, whichare the fisheries where most <strong>capacity</strong> reduction programmes have been implemented <strong>in</strong> recent years8Although <strong>in</strong> one <strong>in</strong>stance, it was reported that regulations were <strong>in</strong> the process of be<strong>in</strong>g developed, based on the ManagementPlan.13

(see below). Boxes 4 <strong>and</strong> 5 provide an assessment of the policy tools that have been shown to work<strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> <strong>and</strong> those that do not.Conclusion: While there has been progress <strong>in</strong> the region s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g appropriatepolicy <strong>in</strong>struments (ma<strong>in</strong>ly fisheries-specific Management Plans) for long-term strategic <strong>management</strong>of <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>capacity</strong>, there appears to be a major issue with<strong>in</strong> the region of a lack of appropriate toolsfor policy implementation. The tools that are lack<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>clude methods, such as regular census orBox 4: Capacity <strong>management</strong> tools – what does workTools that do work Immediate Effect(s) Longer-term Effect(s)Individual effort quotas (IEQs)denom<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> trawl time,gear use, time away from port,<strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> days, etc.Group <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> rightsCommunity DevelopmentQuotas (CDQs)Territorial Use Rights (TURFs)Management <strong>and</strong> ExploitationAreas for Benthic Resources(MEABRs)Limited Access PrivilegePrograms (LAPPs)Designated Access PrivilegePrograms (DAPPs)Individual <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> rights (IFQs)Individual transferable quotas(ITQs)Taxes <strong>and</strong> royalties●●●●●●●●enforcement difficultadditional regulations requiredto control <strong>in</strong>putsubstitutionreallocation of the fisheryto the recipient communityreallocation of the fisheryto the recipient communitymarket forces drive outover<strong>capacity</strong>consolidation occurs ifovercapitalizedmarket forces drive outover<strong>capacity</strong>consolidation if overcapitalizedSource: Adapted from “Management tools – what does not work <strong>and</strong> what does” presentation by Rebecca Metzner atthe APFIC Regional consultative workshop on Manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Capacity <strong>and</strong> <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>Fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>, Phuket, June 2007.●●●●●●●●●●●●capital stuff<strong>in</strong>g – where a vessel’shorsepower, length, breadth, <strong>and</strong>tonnage are <strong>in</strong>creased – frequentlyoccursrequires regulations to ensuretraceability <strong>and</strong> to control transshipmentcreate motives for <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong><strong>capacity</strong> will <strong>in</strong>creaserequires group underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ofasset value of user rights, capabilityto managereduction of over<strong>capacity</strong> or <strong>capacity</strong>conta<strong>in</strong>ment depends on subsequent<strong>management</strong>requires group underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g ofasset value of user rights, capabilityto managereduction of over<strong>capacity</strong> or conta<strong>in</strong>mentof <strong>capacity</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ked to subsequent<strong>management</strong><strong>capacity</strong> managed automatically,over<strong>capacity</strong> does not occur/recurcompliance concerns <strong>in</strong>ternalizedby fishers to protect asset (rallyaga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>IUU</strong> <strong>fish<strong>in</strong>g</strong>) supplementaryregulations helpful to re<strong>in</strong>forceconservationadm<strong>in</strong>istratively <strong>in</strong>tensive: requireconstant adjustment of tax levels toma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>capacity</strong> at desired levelpolitically difficult to impose, easierto resc<strong>in</strong>d14