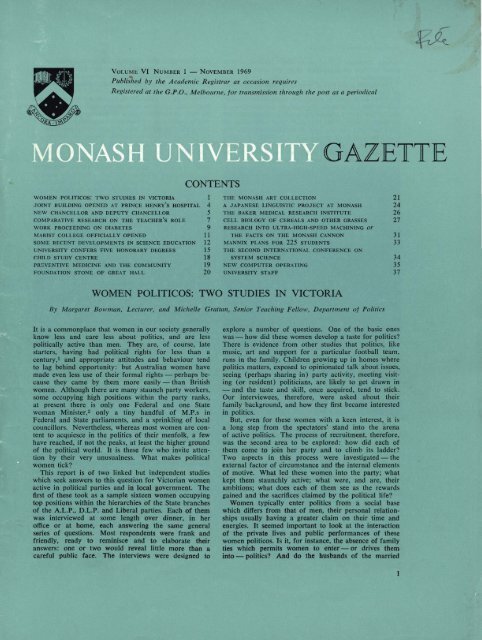

Volume 6 Number 1 - Adm.monash.edu.au - Monash University

Volume 6 Number 1 - Adm.monash.edu.au - Monash University

Volume 6 Number 1 - Adm.monash.edu.au - Monash University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

MONASH UNIVI.RSLTY G·\ZFTTEwomen determine the extent of their political activityeither by their encouragement or by the extent of theiracquiescence in it'?The second study was of women in local government:as there are only forty-two women at present" amongthe 2,500 councillors in Victoria, it was possible to interviewall but one of them (the last was not able to sparetime to see us}. Although the questions asked were notidentical to those of the first study, they were along thesame lines, and a similar form of structured interview wasused. Bec<strong>au</strong>se local government is typically non-party- and at most semi-party (only the A.LP, endorsescandidates) - particular attention Vias given to thecircumstances of recruitment. If at Federal and Statelevel it is the parties which catch, nurture and supportcandidates, what agencies of recruitment serve non-partylocal government'? To explore this question we askedthe councillors how they came to nominate, and wherethey found their support.Also. in order to provide a basis for comparison. wecarried out a survey of men councillors, using writtenquestionnaires posted to the women's council colleagues.Although we would have liked to duplicate the women'sinterviews with a sample of men councillors, a postalsurvey was chosen for its economy. In an effort toensure a good response rate, we wrote to the respectiveTown Clerks requesting that councillors answer questionnaires,and enclosed a copy for their information.Individual questionnaires (anonymous), each in a selfaddressedenvelope, for easy return, were sent in batchesto the Town Clerks for distribution, while the womencouncillors (all but one of whom we had met) willinglyagreed to encourage their colleagues to fill them in.IDS out of 227 sent us completed forms, a responserate of 46 per cent. From these, we have data about themen's ages, occupations, the voluntary associations theybelong to, their length of residence in the municipality,and their comments in reply to this question: 'Do youthink women have a special part to play in localgovernment'!'This latter type of mail survey supplies basic sociologicaldatu. but the harvest, though useful, is meagre. OnMELBOURNE CHANCELLOR LEAVES BEQUESTTO MONASHA former Chancellor of the <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne, thelate Sir Charles Lowe. has left a bequest of $1,000 to<strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong>.The bequest will be used for a prize in a subjectto be determined by <strong>Monash</strong>'s faculty of Law.SECRETARY-GENERAL TO A.V.C.Dr Hugh W. Springer, Assistant Secretary-General(Education) at the Commonwealth Secretariat inLondon, has been appointed Secretary-General of theAssociation of Commonwealth Universities, to succeedthe retiring Secretary-General, Dr John F. Foster, asfrom 1 October 1970.Dr Springer was <strong>edu</strong>cated at Harrison College. Barbados,and Hertford College, Oxford.the other hand, the extended personal interview whichaffords the opportunity for richer exploration intocareer patterns and the personal drives underlying them,also presents its own problems of technique and interpretation.The value of extended interviews for getting at polirices'views and 'style' of politics is very great. One getsthe 'feel' of the participation by hearing the respondent'sown account of it. Moreover, a researcher gleans manyuseful clues about his subject's general approach simplyby listening to how he decribes things, by coming intocontact with his personality, and, most desirably, byseeing him in action.e Documents, speeches. newspaperaccounts, erc., can never give this insight. And the typeof short interview used in the 'mass' surveys (based onmarket research methods) has the limitation for researchon political style and motives of being very brief and,one always fears. of presenting unrepresentative snapshotsof the respondents' political outlooks. Moreover,interviews in these mass surveys are often done by professionalinterviewers and thus the interpreter of thematerial is at the disadvantage of never having comeface to face with his subjects. While such surveys providemuch useful statistical data (e.g., about votinghabits, etc.) they can be of only limited value in assessmentsof motives and style.However, the 'depth' interview approach has itshazards. One which looms for the future will be saturationof the market, for it is the limited number of fulltimeor near full-time political activists to whom thistechnique will be most directed. Our surveys on Victorianpolitical women did not encounter any difficultyof 'overinterviewed' respondents (although there was aminimal overlap between the membership of our twosamples), for this depth interview technique is still notwidely used by Australian political scientists and, moreover,in our project we were dealing in the main withJow-level political figures (and women at that). However.as Australian universities' rapidly flourishingpolitical science and sociology departments continue toincrease the number of those in the 'trade', and as theuse of sociological and psychological techniques spreads,we may find that the limited number of potential'guinea-pigs' among activists at the higher level imposesrestrictions on this type of research. Already there havebeen stories from the United States of congressmen inundatedwith questionnaires, with the result that somesort of restrictions and selection become necessary: asimilar sort of 'rationing out' of politicans and the liketo academic fieldworkers may come to pass in Australia.Another difficulty with this type of research is thatone is probing at a depth and into areas which maymake the active political participant, and especially thepublic figure with a career to consider, reluctant to takepart in such studies. We encountered this to a minorextent with our women: a couple of the respondents inone survey raised objections to publication of thematerial. Moreover, obviously the higher up the politicalladder one goes, the more this problem arises: the toppolitical figures either simply would not submit to thistype of interview, or would maintain a perfectly 'public'face throughout it, or else place severe limitations onthe use of any such material. Thus it is the 'middlelevel'political figure who is most accessible for this typeof research.f And yet it is the tallest poppies whom onewould most like to examine closely and whose politics2

would yield the most interesting data under this technique.This trend towards using extended interviews, psychologicaltechniques and the like, in the study ofpolitical motivations and styles (the way in which aperson acts out his political role) is a manifestation ofthe general pushing-out of the boundaries of politicalscience - for so long tied to historical-legal-institutionalapproaches and studies - into the neighbouring areas ofpsychology, sociology and statistics. The developmenthas been evident throughout the postwar period, withthe blossoming of the 'behaviouralist' school, and itseffect has been felt in most aspects of political science(for example, the switch in emphasis from historicaldescriptivestudies to a model-building statistical approachis nowhere more evident than in recent work in internationalrelations). However, extending the frontiersmakes new demands on researchers. Political scientistshave realized the greater depth of analysis made possibleby using techniques from other disciplines, but many ofus (at least in Australia) have to use these techniqueswithout having had full training in the theoretical conceptsof the disciplines from which they derive (forexample, the spread of the methods of psychology amongnon-psychologists). In our own researches, we soonfound ourselves in the 'grey' area between politicalscience and psychology when we started exploring thewomen's motives and drives towards political activity.The fruitfulness of these studies, however, will extendas political science departments increasingly give theirstudents some bases in allied fields - either by courseswithin their own departments or by cross-teaching withother disciplines. A start has been made in a numberof politics departments (including <strong>Monash</strong>) along theselines. Although the problems of such a cross-disciplinaryapproach are great, especially with political science.which is less a discipline in itself than a hotchpotch ofbits and pieces of many disciplines. the advantages faroutweigh them. There is a wealth of gold to be foundby investigating what makes people tick politically. thesources of their attitudes, how they pick up their skills,and why they choose to play a political role: but wemust band together and mine the material as a company,rather than stick to our individual tools.EMBASSY'S GIFT OF2,000 BOOKSA gift of approximately 2,000 books has been receivedby the <strong>University</strong> from the United States Embassy. TheEmbassy's Counsellor for Public Affairs, Mr Charles F.Blackman, acting on behalf of the current United StatesAmbassador, Mr William H. Crook, officially presentedthe gift early in 1969. These books became availableafter the reorganization of the U.S. Information Servicelibrary in Sydney.The Vice-Chancellor, Dr J. A. L. Matheson, acceptedthe books on behalf of the <strong>University</strong>.lWomen got the right to vote and stand for FederalParliament in 1902; in Victoria they became eligible 10vote for State Parliament in 1908, hut it was not until1923 that the hill 11'as passed making H'omen eligible forseats in it.'.2Federal: Dame Annabelle Rankin; Stute. Mrs JoyceSteele (South Australia).»Durtng 1968, including both those 11'110 II'ere defeatedor resigned and those 11'110 first look their seals in A ueustof tlwt year.40ne limitation 0/1 the nseiulness of politicos' personalaccounts of their activity is that unless it is seen in thecontext of their behaviour in their part}' or connell. ittends unduly to highlight the elements of private motiveand thereby r<strong>edu</strong>ce the significance of inter- and intragrouppressures which significantly afjat both opinionsand decisions.'SNote that A Ian Davies' pioneering book in this field;/1 Australia, 'Private Politics', dealt only with. what hecalled 'second drawer' politicos.Dr Matheson examining one of the books with MrRichard Service, Consul-General for Victoria andTasmania, and Mr Charles Blackman, an EmbassyCounsellor tor Public AfjairsPROTEST SYMPOSIUM"The Anatomy of Protest' was the theme for a seriesof public lectures held at <strong>Monash</strong> during July this year.The Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne, Dr F. Woods,began the series with a lecture about protest and religion.He was followed by Associate Professor H. Mayer, fromthe <strong>University</strong> of Sydney, who spoke about protest andpolitics; Professor P. Brett of the Law faculty at the<strong>University</strong> of Melbourne then lectured on 'Protest, theCommunity and the Law'; and Professor A. G. Hammer,<strong>University</strong> of New South Wales, spoke about 'Protests,Motives and Personalities'.3

NEW CHANCELLOR AND DEPUTY CHANCELLORSir Douglas MenziesDr Gordon LennoxSir Robert BlackwoodSir Michael ChamberlinSir Douglas Menzies was installed as second Chancellorof <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> at a ceremony on 11 April 1969in the presence of the Visitor, Sir Rohan Delacombe,and a number of other distinguished guests. A gradualionceremony for the faculty of Arts followed the installation.Sir Douglas graduated as Bachelor of Laws from the<strong>University</strong> of Melbourne and was admitted to the Barin 1930. He has had a distinguished legal career, duringthe course of which he has held official positions on thecommittees of numerous organizations. [0 1957-58 hewas president of the Medico-Legal Society, and in 1958held the position of president of the Victorian Bar. Hewas appointed a Justice of the High Court of Australiain 1958.Sir Douglas is co-<strong>au</strong>thor of a book entitled VictorianCompany Law and Practice.Sir Douglas has an outstanding record in public life,where he has held numerous positions including HonoraryArea Commissioner of Toe H between 1948-58,and president of the Heart Foundation of Australia during1954-57 and 1961-62.In the course of his address to the graduands at theceremony, Sir Douglas said:'This is called an occasional address. You know it isyour occasion not mine, and it would be inappropriatewere I not to use part of it to speak particularly tothose who have graduated today. When you look backit probably doesn't seem very long since you came hereas undergraduates, but when you came as undergraduatesand you looked ahead, this day probably seemeda long way in the future. Both are, of course, linked.When you came to <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> as undergraduatesyou committed yourselves to a life that I will call thestudent life. For a university is essentially a fellowshipof students which embraces the youngest undergraduateand the oldest professor. There is a tie that binds us alltogether. But I would not have you think that becameyou have finished a course and you have ceased to beundergraduates and have become graduates that thestudent life is finished for you. I hope you won't shakethe dust of <strong>Monash</strong> from off your shoes and I hope youwon't say we have finished with university and we nowstart work. If you do, we have failed in the great partof the task to which this <strong>University</strong> is dedicated.'DEPUTY CHANCELLORThe recently-appointed Deputy Chancellor of <strong>Monash</strong><strong>University</strong>, Dr Gordon Lennox, is a Melbourne graduatein biochemistry who, apart from a short period at theLondon School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine workingon fungal enzymes, has spent his entire researchcareer with C.S.I.R.O. The first three years were spentwith the Division of Entomology in Canberra where hewas investigating insect physiology and the mode ofaction of insecticides. but since 1940 he has been inMelbourne leading an ever-expanding team of biochemists,biophysicists, physical chemists and organicchemists studying the structure and chemistry of fibrousproteins, especially those in wool, skin, hide and muscle.Dr Lennox became chief of the C.S.I.R.O. Divisionof Protein Chemistry when it was established in 1958and has been chairman of the C.S.I.R.O. Wool ResearchLaboratories group since (heir formation in 1949.Dr Lennox is a fellow of the Royal Australian ChemicalInstitute and of The Textile Institute and has beenpresident of the Australian Biochemical Society. Apartfrom serving <strong>Monash</strong> he is interested in some otherdevelopments in tertiary <strong>edu</strong>cation through his roles aschairman of the Schools Board for Pharmacy and BiologicalStudies of the Victoria Institute of Colleges andas a member of the faculty of Textiles of the GordonInstitute of Technology at Geelong.In addition to serving on the Council and numerous<strong>University</strong> committees, the Deputy Chancellor is particularlyinterested in <strong>Monash</strong>'s future development. Hewould like to see established in the <strong>University</strong> a newcentre that would provide a means of improving communicationwith, and assistance to, the community outside.Council TributesThe following tributes by the Council were recordedin honour of the retiring Chancellor and Deputy Chancellor.SIR ROBERT Bl.ACK\VOODTo Sir Robert Blackwood, who retired from theChancellorship of the <strong>University</strong> on 9 December 1968,the <strong>University</strong>, the State of Victoria and a great numberof individuals owe a debt which is beyond bothassessment and praise.When the Interim Council was established in April1958 Mr Robert Rutherford Blackwood. as he thenwas, was appointed chairman. Immediately he brought5

COMPARATIVE RESEARCH ON THE TEACHER'S ROLEBy B. J. Biddle, Visiting Professor, Faculty of EducationFor the past five years I have been leader of a team ofsocial scientists who were studying what it is like to bea teacher in four (supposedly) English-speaking countries:New Zealand, England, the United States andAustralia. Data for this project were obtained fromLarge and representative samples of teachers in eachcountry and provided information on the hopes, thefears, the conflicts, the activities, and the values andaspirations of teachers in each of these countries. Thisproject has involved social scientists from each of theparticipating countries, for in conducting comparativeresearch it is vital to involve scholars from all settings- not only to facilitate data collection and to chooseimportant issues for research, but also to re-wordquestions so that they are equally meaningful for speakersof each 'local' tongue. In the case of our project,regular meetings of the participants have taken placeevery few months, and all phases of the researchplanning,pre-testing of instruments, data analysis andinterpretation - have been co-operatively engendered.Why is it useful to study the role of the teacher?Three answers may be given to this question, and eachhas played a part in motivating the study. In the firstplace, we have wanted to study the teacher's role bec<strong>au</strong>seteachers playa vital part in <strong>edu</strong>cation and bec<strong>au</strong>sethe proc<strong>edu</strong>res and rationale of <strong>edu</strong>cation differ fromcountry to country. The research literature of <strong>edu</strong>cationis full of studies concerning learners and learning, butwith little research concerning teachers and teaching.One of the reasons for this imbalance lies in thecommon belief that teaching is merely a facet of learning,or the counterpart of it, or inferable from it. Yetlittle is actually known today about the actual classroombehaviours of teachers, or about the beliefs, norms, andvalues held by teachers constraining their classroom performances,This lack of information is truly tragicsincepoliticians and <strong>edu</strong>cational administrators continuallyindulge in decisions aimed at influencing teacherbehaviour, and teachers (for their part) continuallyworry over the degree to which their professional behaviourmeasures up to the standards they have arbitrarilyaccepted for it.Our second reason for the study concerns teachersthemselves. Although the primary tasks of the schoolsconcern pupil <strong>edu</strong>cation, unless teachers are recruited,properly trained, and kept adequately motivated therewill be no <strong>edu</strong>cation. In each of the countries studiedthere is a teacher shortage, Thus, the problems, concerns,beliefs, and professional commitment of teachersare matters of public concern, and to the extent thatthe study throws light on these problems a public servicewill have been performed.Our third reason, however, is the soundest - that ofscientific curiosity. It is well known that most 'findings'in the SOCial sciences have been validated on but limitedpopulations. (In fact, it is conceivable that the bulk ofexperimental social psychology may be merely 'thepsychology of American university sophomores' - anappalling thought.} In the field of role theory, almostnothing is known about the professional roles of personsoccupying similar positions in different societies. Inaddition, comparative research in which strictly comparabledata are collected from several countries isalmost unknown in <strong>edu</strong>cation. (The I.E.A. study ofmathematics achievement is, of course, a notable exceptionto this generalization.) In the case of teacher role,almost no comparable data have ever been collected frommore than one country.So much for why. How, then, was the project conducted?For all practical purposes we can divide theeffort into two phases. The first phase, a pilot study,was designed for exploration and consisted of an intensiveinterview conducted with relatively small samplesof teachers. One hundred and twenty teachers werecontacted in each country including equal numbers ofmen and women, primary and secondary teachers, andteachers from schools of various sizes. A battery ofthree research instruments was developed and administeredto all respondents, including an interview sch<strong>edu</strong>le,a questionnaire, a diary form, and a shorter questionnairethat was filled out by the headmaster of the teacher'sschool. Of these, the most important source of datawas the interview which took approximately 2-2; hoursto complete. These interviews were tape-recorded, andwere later transcribed verbatim.Since it was not possible to use the same personnel toadminister the instruments to respondents in each country,a detailed training programme was designed to besent to all countries for local implementation. Thisprogramme involved a training manual and tape recordingsof sample interviews designed to exemplify all ofthe exigencies likely to occur in the course of interviewing.Research associates at each of the sponsoringuniversities (in Australia, the <strong>University</strong> of Queensland)were responsible for the training of personnel to be usedin collection of data.Data from phase 1 were then subjected to detailedanalyses, and the results then formed the bases fordiscussions among the associates concerning the secondphase of the project. It is difficult to convey the detailand time involved in these discussions, but regularmeetings were held over more than two years attemptingto code and interpret responses, formulate hypothesesconcerning national differences in teachers' roles, anddesign and pre-test instruments for testing these hypotheseswithin larger and more representative samples ofteachers, Some of the problems we encountered had todo with disparities in <strong>edu</strong>cational terminology. Forexample, we found it impossible to establish any reasonabledegree of equivalence between the systems usedfor classifying pupils by grades in the four countries.Instead, teachers were asked to report the age rangesof pupils in their classes. More subtle problems had todo with the implications of words. For instance, instudying career commitment we first attempted to usethe term 'dedicated', Dedication. however, has a ringof fanaticism to British teachers that it does not toAmericans, and so (despite the fact that Americansoccasionally presume 'commitment' to mean incarcerationin an asylum) we decided to ride with the latter term.The second phase of the project was concerned withgathering data from a national sample of teachers ineach of the four countries. In general, this. was. doneby drawing a representative sample of schools, and then7

MONASH UNIVERSITY GAZETTEcontacting the headmasters of those schools and asking spondents' anonymity would be preserved. Each questhemto distribute questionnaires to all of their full-time tionnaire was accompanied by a stamped envelopeteachers. In Australia the sample was drawn for us by addressed to the participating university; consequentlythe Australian Council for Educational Research and was respondents were able to return their questionnairesa random sample of state, independent, and Roman privately so that school officials had no occasion to seeCatholic schools, stratified by state. Approval for the the answers given. Questionnaires carried an identifiesstudywas obtained through personal contact with the tion number telling us which school they came from.Directors of Education in each state capitaL In addition, however, and schools that failed to respond were solirepresentativesof Catholic <strong>edu</strong>cational <strong>au</strong>thorities were cited by additional letters and packets of questionnaires.consulted as were those of the Headmasters' and Head In general, response rates for the study were high.mistresses' Associations and of the teachers' unions and Of those teachers contacted, in New Zealand 76 perprofessional associations in each state capital. Similar cent returned usable questionnaires to us. In Australiasamples, and endless conlact proc<strong>edu</strong>res (!), were car the figure was 62 per cent, in England 56 per cent,ried out in the other three countries.while in the United States 54 per cent participated.Each school in the study received a package contain Although the meaning of these differences may not being: a short questionnaire for the headmaster, sufficient interpreted unambiguously. it is noteworthy that in thosequestionnaires for each full-time teacher, and a two-page countries with centralized control over <strong>edu</strong>cation (Newpersonal letter explaining the purposes and rationale for Zealand and Australia) response rates were higher thanthe study and soliciting the co-operation of the head in those countries characterized by local control (Englandmaster and teachers. The letter also pointed out that and the United States). Altogether, 12,263 questionnairesparticipation in the study was voluntary and that re- were coded and processed - not including some 12018.11 I.Emphasis by teacher on subject matter of thelesso n1Raw ScoresI04)E(4.Adjusted ScoresNZ(405J-1' /\'A(4.1II10(4.13) lIS(4.16)18.2 IEmphasis by teacher on personal relationships withIend ?mong pupilsUS(3.H7) NZ(3.92)Raw ScoresAdjusted ScoresII.,2 25 3 3.5 4 4.5, , , , , ,1LlHle or no 51igh~ Moderate Strong A. gre~t dealemph!lsis emph!lsi< emphasis emphasis of emphasisA(4.19)NZ(4.00)'

questionnaires which were not usable for one reason oranother. Completed questionnaires were returned tothe participating university in each of the four countries.After being checked they were then forwarded to acentral location for coding and analysis, the latter beingaccomplished using computers.So much for why and how. What, then, was studied,and what have we discovered? Insufficient space isavailable here to provide more than a brief overview ofcoverage. The questionnaire used in phase 2 of thestudy, for example, dealt with personal and professionalbackgrounds of teachers, classroom teaching style, perceptionsof professional role and role conflict for theteacher, norms concerning in- and out-of-school professionalbehaviour, history and attitudes towards professionalinvolvement, questions indicating teacher morale,and values regarding a number of controversial <strong>edu</strong>cationmatters such as the use of corporal punishment and<strong>edu</strong>cational grouping.Fig. 1 illustrates national findings for six questionsselected from those dealing with classroom practices.Respondents were asked to indicate how much theyemphasized 'subject matter', 'personal relations'. 'discipline','performance', 'facts', and 'understanding' intheir classroom instruction. National averages (means)for respondents from each country are given in Fig. I.Two sets of figures are presented. Those above the lineconstitute the 'raw' averages from each country. However,in looking over responses to all items, it quicklybecame apparent that respondents from different countriesdiffered in the degree to which they 'emphasized'things. Thus, Americans said they gave 'more emphasis'.followed by Australians, New Zealanders. and Englishmenin that order. In addition to confirming some internationalstereotypes, these effects generated 'response bias',to compensate which, scores from all countries wereweighted to equalize averages. Weighted averages aregiven by scores appearing below each line of the figure.As will be seen in Fig, 1 respondents from all fourcountries tended to answer each of the six questionsdisplayed in similar fashion - that is, all said theytended to emphasize 'understanding', and all gave somewhatless emphasis to 'performance' and even less to'facts'. However, substantial differences abo appearedamong the four countries in terms of emphasis revealedfor these items. Australian teachers, for example, saidthey gave more emphasis to 'subject matter' and 'performance'.and less emphasis to 'personal relations' thandid teachers from the other three countries, suggestinga somewhat traditional classroom. Interestingly, Americanteachers said they gave less emphasis to 'performance','facts', and 'understanding' than teachers fromthe other countries -leaving one to speculate as toexactly why they conducted their classrooms in the firstplace! Other findings may easily be seen in the figure.My appointment to <strong>Monash</strong> as a visiting staff memberis allowing me time to complete this study - to concludedataanalyses and to write up findings in article and bookform. Some of our findings support, but other challenge,widely-held stereotypes concerning <strong>edu</strong>cation inthe English-speaking world. However, comparative revsearch of substance is impossible to conduct withoutopportunities for co-operation among academics ofvarious nationalities, and <strong>Monash</strong> is to be commendedfor its programme of staff visitors that facilitates projectssuch as this study.WORK PROCEEDINGON DIABETESConsiderable interest has been aroused by theannouncement early this year of a new approach to theclinical treatment of diabetes by a team headed byProfessor Joseph Bornstein of the department of Biochemistry.Tn a comment on the results. which were published inthe British Medical Journal, Professor Bornstein saidthey followed upon twenty years' research into mechanismscontrolling the me of glucose and fats in mammaliantissues. He emphasized that no new treatmentexisted. What did now exist was a finding that hadtherapeutic potential.Professor Bornstein added:'Work in this field was begun in 1948, initially inan endeavour to determine the c<strong>au</strong>se of anomalies ininsulin dosage observed in the treatment of diabetes.Initial work proved that a sizeable proportion of diabeticsdid in fact secrete insulin often in amountsgreater than normal but that this was inadequate to theirneeds.'The clear conclusion was that some anti-insulin substancewas operating in such patients, Research was thenProfessor J. Bornstein (left) with Dr F, M. Ngswitched into an endeavour to isolate and characterizethis substance.'At about the same time it was shown by workersin the Argentine and England that the injection ofpituitary growth hormone into animals produced over aperiod of time, first, insulin resistance, then temporarydiabetes, and finally permanent diabetes. Other workersin the U.s.A. noted that prior to the development ofinsulin resistance, there was a sharp fall in the hloodsugar of the injected animals.'My work proceeded in England, the U.S.A. andAustralia on mechanisms related to the growth hormoneinduced resistance, and the first glimmerings arose whenDr C. W. Baird and I were able to show that a certainmethod of extraction of plasma from diabetic patientsyielded a very crude material which opposed the actionof insulin in experimental systems. Then with Dr9

MONASH UNIVERSITY GAZETTEMargaret Sanders, Miss D. Hyde, and Dr F. I. R. Martinwe demonstrated that the presence of this material wasdependent on a functional pituitary gland. Research wasthen switched to the pituitary and we were able todemonstrate that the material was derived from pituitarygrowth hormone and was of small molecular weight.Laboratory studies with partially purified insulin antagonistfrom growth hormone, however, at times producedanomalous results. Statistical studies of these indicatedthat the insulin antagonist was contaminated by a similar-sizedmolecule with diametrically opposed action.These were separated in micro quantities and studiesbegan at <strong>Monash</strong> into two aspects of the problem.'The first was obviously into methods of preparationand purification and the second into the mechanism ofaction of these fractions.'Although these studies are still proceeding, sufficientdata had been obtained by the beginning of 1968 toindicate clearly that the insulin antagonist operated byspecifically inhibiting three enzymes involved in glucoseuse and fat synthesis and by virtue of these actions indirectlystimulated the use of fat. The other fraction (codenamed ACG) reversed these four actions by competitiveaction on the three enzymes involved.'Study of the model systems thus derived enabled anhypothesis as to the c<strong>au</strong>se of diabetes mellitus in thepresence of insulin to be made.'In order to test this hypothesis, a group of volunteerpatients, all known to be capable of secreting insulin,were injected with ACG and their blood sugar levelsfollowed. In all cases there was a highly significant fallin blood sugar, thus suggesting that the hypothesis wastenable and bringing up the possibility of a new methodof treatment of a condition affecting over 2 per cent ofany high living standard community.'From this point research has to follow two lines.Firstly we will continue to investigate the systems involvedin these actions, to elucidate completely thestructure of the two polypeptides and to synthesize them.'Secondly, an investigation into the possible role ofACG in the treatment of diabetes mellitus has alreadycommenced in association with the Alfred Hospital'sMetabolic Unit headed by Dr H. P. Taft. It must berealized that at this time we do not even know thecorrect dosage of ACG, the time relations of administrationor indeed whether it has any advantages overorthodox methods of treatment.'Such an investigation is necessarily prolonged andits cost on a scale capable of yielding results in areasonable period of time far beyond the resources ofthe <strong>University</strong> or our hospitals. Thus the scale of theundertaking is beyond our control.'Professor Bornstein concluded by saying he wishedto thank all members of the research group, notablyDr J. Me D. Armstrong, Dr F. M. Ng, Dr H. P. Taft,Dr M. Gould. Professor M. E. Krahl, Mrs L B. Marshalland our graduate scholars, for their contributionsin taking the problem to this point.MONASH STUDENTS SET RECORD IN BLOODDONATION<strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> students donated 345 pints of bloodduring a four-day visit to the campus by the Red CrossBlood Bank in October 1969. This figure is the highestever reached at the <strong>University</strong>.Miss Mona Lai, sociology student, shown in the potteryclass conducted by the Fine Arts clubEXTRA-CURRICULAR COURSES PROVIDED BYTHE UNION AND STUDENT CLUBSTn 1969 the <strong>University</strong> Union and student clubs andsocieties offered courses of extra-curricular tuition insubjects ranging from handcrafts to languages. Over1,000 students and members of staff participated inthese classes, some of which were organized by theUnion staff, and others by student clubs. In many casesprofessional people from outside the <strong>University</strong> werehired to take classes on the campus.Although most tuition was given on a small classbasis, seventy people received individual tuition in theplaying of musical instruments and singing.Among: the wide range of subjects offered there werecourses in Italian. Esperanto, Hebrew, various forms ofdancing and music, the fine arts and effective speaking.Many of these activities are to be included in theprospectus for a <strong>Monash</strong> Summer School which has beenarranged by the Union for January and February 1970.FOURTH HALL OF RESIDENCE NAMED<strong>Monash</strong>'s fourth hall of residence, the building ofwhich will commence early in 1970, has been named'Roberts Hall' after the Australian artist, Tom Roberts(1869-1931), a prominent member of the Heidelbergschool of painting.The decision that the hall would be so named is inkeeping with the plan to name the halls of residence afterdistinguished Australians.A planned fifth residential hall will bear the name'Richardson Hall', after the novelist Henry HandelRichardson (1870-1940), the <strong>au</strong>thor of The Fortunes ofRichard Mahony.The three existing halls are named Deakin, Farrer andHowitt Halls.10

PORTRAIT OF THEVICE-CHANCELLORMiss Christine Backhouse and the Vice-Chancellor withhis portraitThe <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> Parents' Group presented theVice-Chancellor with a portrait of himself at a ceremonyin the Alexander Theatre on Wednesday 24 September.This oil painting, which is the work of anEnglish-born artist, Christine Backhouse, was presentedby the president of the Parents' Group, Mrs Pat Hutson.It is intended to hang the portrait in the RobertBlackwood Hall.DR MATHESON VISITS OVERSEASUNIVERSITIESIn the early part of 1969, from March to June,Dr J. A. L. Matheson made a tour of numerous Americanand Canadian universities. On his return trip hevisited three universities in Britain.There were two major questions which Dr Mathesoninvestigated during his visit, namely, the effects of recentdevelopments, including student activities, on the universities,and also the methods of government, thebudgeting techniques and the effects of year-roundacademic operation in North American universities.The tour was financed by a grant from the CarnegieCorporation of New York.ALEXANDER THEATREDuring 1969 fourteen major productions were held inthe <strong>University</strong>'s Alexander Theatre, as well as numerousone-night performances. Of these productions five wereby <strong>Monash</strong> groups.The <strong>Monash</strong> productions were: Alan Seymour's 'OneDay of the Year'; 'Lysistrata'; 'Zoob', a collection offour contemporary plays; Lorca's 'Blood Wedding'; andthe musical 'Kiss Me Kate'. The Melbourne YouthTheatre was the outside group which used the AlexanderTheatre most frequently. It performed three plays->'Macbeth', 'Three Sisters', and Genet's 'The Balcony'and sponsored the Sydney Company, The Margaret BarrDance Drama Company.MARIST COLLEGEOFFICIALLY OPENEDAt 3 p.m. on Friday 7 November 1969 the Marist College,a residential college for male students of <strong>Monash</strong>,was officially opened. His Grace, Archbishop J. R.Knox, gave the blessing. The college was officiallyopened by the Minister for Immigration, Mr B. M.Snedden.Marist College, affiliated with <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong>,consists, in the first stage, of two three-storey brick residentialblocks, lined by a covered walk to a single-storeyrefectory building.The designers have produced a plan that combinestraditional university college functions with an enclosedmonastic concept which includes a cloistered quadrangle,'family' grouping of students' bedrooms and tutors' suitesand areas designed to foster organized or impromtudiscussion.Marist College is under the direction of the MaristBrothers, a religious order which has been involved inAustralian <strong>edu</strong>cation for the past one hundred years.The college owes its origin to the need of the Order toqualify its future teaching members as university graduates.Hence, the Marist Brothers purchased the presentproperty on Normanby Road at a time when <strong>Monash</strong>was first projected.The building of a residential college at <strong>Monash</strong> byMaris! Collegethe Marist Brothers was done primarily in the interestsof their own trainees. However, there will be a balanceof accommodation at the disposal of other studentswishing to benefit from the facilities of the college.Commonwealth and State Governments have consequentlyshared with the Brothers the cost of construction.The present stage caters for a total of ninety students,seventeen tutors and administrative staff. Final capacitywill be two hundred. It is anticipated that about onequarter of the 1970 intake will be Marist trainees. Theiruniversity courses are geared to secondary teaching needsand the range of tutorials offered at first is likely toreflect this bias towards science and arts.GANDHI CENTENARYThe centenary year of Mahatma Gandhi-1969-wascelebrated by members of <strong>Monash</strong> with a ceremony inthe Religious Centre.The commemoration took the form of readings fromthe Gita, the Bible and the Koran. Professor A. BoyceGibson, formerly professor of Philosophy at the <strong>University</strong>of Melbourne, delivered a short address.11

MONASH UNIVERSITY GAZETTESOME RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN SCIENCE EDUCATIONBy P. J. Fensham, Professor, Faculty of EducationLate in 1968 the Commonwealth Minister of Educationand Science announced that the Government was preparedto make a substantial contribution towards aninterstate venture to produce a new science curriculumfor the first four years of secondary schooL Over a fiveyearperiod the budget for this project will amount tomore than $1,000,000. This announcement marked theentry of Australia into the ranks of large money-spenderson courses for science <strong>edu</strong>cation, such as the NuffieldScience Projects in England, and a variety of agencies inthe U.S.A. which have spent large sums in recent yearsdeveloping material for various science courses at alllevels of schooling, from elementary to senior secondary.The Federal Government had, five years earlier, announceda programme of special grants for buildingand equipping science laboratories in all types of schools.Indeed. science <strong>edu</strong>cation was singled out as havingsuch peculiar priorities that it was a suitable case tojustify the double precedent of Commonwealth entryunilaterally into secondary <strong>edu</strong>cation and of makingpublic money directly available to non-governmentschooTs.These events in Australia have had their counterpartsin many countries of the world. and the l<strong>au</strong>nching ofthe Russian Sputnik in 1957 is a convenient event whichis usually taken as the harbinger of a new era in science<strong>edu</strong>cation. However, the technological demands of anationalistic race for space supremacy, while substantial,are only one of many pressures that have produceda ferment in science <strong>edu</strong>cation that is rapidly spreadingto aU parts of the world. The pressures may be differentdepending on the stage of national development. Inan undeveloped nation there is the need for skilledscientists and technologists to take up particular featuresof the struggle for modernization. But there is equallythe task of making a scientific way of thinking sufficientlyindigenous to the population at large that scientific andtechnological potential for progress can be realized andaccepted.At the other end of the scale. in the more developed,and hence more technologically-dependent nations, thereis a growing need to produce a higher and higher proportionof the work force with a high level of scientificand technical <strong>edu</strong>cation. In these countries, this proportionis already so large that the need can only be metby including science more and more as part of thegeneral <strong>edu</strong>cation of the whole population, so that thebase from which specialists can be selected remains aslarge as possible. This follows from the usual assumptionthat science itself is sequential, so that there canonly be 'dropout' for the study of science; no realattempt is made to resume science after they haveabandoned it for years.These aspects of human resource development, whichcall for more and better science <strong>edu</strong>cation. are inextricablymixed with a growing awareness of the contributionthat science has to offer to <strong>edu</strong>cation in its moregeneral sense of developing individuals and groups.An illustration of the way that these 'pure' and 'applied'aspects of <strong>edu</strong>cation become one is the followingcomment: 'Creating in students the ability to cope withnew and unexpected findings is a central objective of theinnovators who have been experimenting with <strong>edu</strong>cationalprogrammes in the last fifteen years.'Despite the different reasons for improving and extendingscience <strong>edu</strong>cation, all countries are experiencingthe same problems of an acute shortage of qualified andcapable science teachers, of an urgent need for newscience curricula with supporting teaching aids andmaterials. and of expanding laboratory facilities andequipment for the teaching of science. Universities haveimportant contributions to make to the solution of theseproblems, especially to the training of teachers and tothe basic research upon which the development of curriculaand instructional materials depends.However, it has only been in the last three yearsin Britain and Australia that the first appointments havebeen made in universities of professors of <strong>edu</strong>cation withparticular reference to science. It is new universitiesin both countries that have taken this step. The <strong>University</strong>of East Anglia has a chair of chemical <strong>edu</strong>cationwithin its school of chemical science. The <strong>University</strong> ofSurrey has a professor of physics who also holds a chairof science <strong>edu</strong>cation, and the <strong>University</strong> of Stirling hasa professor of <strong>edu</strong>cation who has a biology backgroundand who has introduced special courses for biologyteachers. The two universities in Australia with specialwork in science <strong>edu</strong>cation are Macquarie and <strong>Monash</strong>,with a director of teaching (with special reference toscience) at the former, and a chair in science <strong>edu</strong>cationat the latter.In all of these cases there is a strong emphasis on thelink between the science departments of the universityand the <strong>edu</strong>cation departments or faculties. This linkis also strongly evident now in the U.S.A. where science<strong>edu</strong>cation departments have existed for a number ofyears, but were. previously, usually rather isolated fromcontacts with practising scientists.Development of New Science CurriculaThe formation of new curricula and the developmentof associated instructional material has been the area ofscience <strong>edu</strong>cation in which the most striking progress hasbeen made since the Sputnik dateline. These projects.whatever their emphasis, have shared certain commonclements. They have been initiated by distinguishedscientific scholars who have worked side by side withteachers and <strong>edu</strong>cational psychologists. They have drawnon all the light that contemporary psychology and relateddisciplines can provide. They have been conductedoutside the <strong>edu</strong>cational establishment of statedepartments of <strong>edu</strong>cation and have usually been associatedwith a university centre, so that the link with workingscientists is maintained. Examples of these are therelations between the Massechusetts Institute of Technologyand the Physical Sciences Study Course (now usedin fifth and sixth forms in Victoria and Queensland),the <strong>University</strong> of Colorado and the Biological ScienceCurricula Study, Chelsea College. London, and the NuffieldScience Projects, and the U.N.RS.C.O. ChemistryProject and the <strong>University</strong> of Chulalongkorn, Thailand.In the new look at the place of science in the <strong>edu</strong>cationalprogramme of schools, these curricula constantlystress the need to teach the particular science as a12

modern growing: subject, to give pupils a lasting sense ofits nature as a structure of knowledge and to engenderproper attitudes to science and its social significance.There is usually a strong emphasis on the place of experimentaL work in the learning process. The nature ofthis practical experience varies, depending on howstrongly oriented the particular course is towards a'discovery' approach. A typical description of one ofthese secondary level courses is the following N uffieldone:'In the early stages - forms I and 2 - the pupils willbe making acquaintance with phenomena in the physicalPrimary school children observing the phenomenon 0/dissolvingworld. a stage of seeing and doing, without formal notetakingand without expressing the results in formal statements.Then, in forms 3 and 4, there should be a stageof more organized investigation and learning, with intriguingquestions to provoke thinking. Towards the endof the course, in form 5, the part played by theory inmaking a grand scheme of knowledge can be exploredovertly and shown to be a proper part of scientific work.'Where science courses in the past tended to emphasizefacts, and some specific laboratory skills, the new coursesemphasize understanding. Studying a science subject isto become an interesting business of finding out facts,concepts and principles, of doing one's own experiment')and of arguing from one's own thinking, as well aslearning what the teacher says,Some of the most exciting developments of newcourses arc occurring at the primary level of schooling,where science has traditionally been absent. except forthe rather arid equivalents of the nature study familiarto many who have known Victorian <strong>edu</strong>cation at anystage in the last fifty years. At this primary level it ismuch easier to relate the teaching of science to estabfishedknowledge about the intellectual development ofchildren, and the work of psychologists like Piaget.Bruner, Skinner and Vigotsky has been particularly importantin these courses. However, it is again customaryto find highly-trained scientists side by side with teachersand <strong>edu</strong>cational psychologists in the project teams. Theemphasis given to the three elements of a science course- phenomena, concepts and processes - again variesfrom course to course. Greater extremes of emphasisoccur at this level, as these courses are freed (unlikescience at secondary level) from all the pressure to bethe direct groundwork on to which are built the tertiarycourses for scientists and technologists,At one extreme are courses like the Nuffie1d PrimaryScience in England and the Elementary Science Studyin America. which stress the child's involvement withnatural phenomena and which leave concepts and processesimplicit and an unstructured part of the involvement.At the other extreme, the American Associationfor the Advancement of Science Courses stresses thechild's practice with processes and uses the phenomenaonly as vehicles and the concepts as tools. In betweenlie the others such as the new Victorian Primary ScienceCourse, which is closer to the former, and the ScienceCurriculum Improvement Study centred at Berkeleyunder Professor Karplus -- a physicist - stilt stressingphenomena but making concepts very explicit.The Education of Science TeachersTwo substantial reports appeared in Britain in 1968.The committee under Professor Dainton reported on thedrift of students away from science in the upper levelsof secondary school, and its subsequent impact on thenumber of science students at the tertiary level. Amongthe large number of recommendations in the report areseveral related to science teachers and the teaching ofscience. Hard on the heels of the Dainton Report camethe Swann Report, which deals with the flow of personsinto science and technology. The two major areas ofemployment which are not, at the moment, receivinganything like the right proportion of trained scientists andtechnologists are industry and school teaching. Calculationssuggest that somewhere between one-quarter andone-third of the tertiary graduates need to return to thetraining process if a stable situation with quite modest<strong>edu</strong>cational conditions is 10 he maintained. The SwannCommittee regarded the problem of adequate suppliesof qualified science teachers as so acute that they madea number of recommendations about it, including one¥ • .. .. $ ...."'" 11 ..Primary school children being introduced to the processof categorizing by sorting nuts and washers13

MONASH UNlVERSlTY GAZETTEwhich suggests differential salaries and conditions forscience teachers.At the moment, in Australia, there are somewhatconflicting indications about the existence of a drift fromscience. It is certainly not as clear as in Britain, butthere is no doubt that Australia suffers even more acutelythan Britain from a shortage of well-trained scienceteachers, and exhibits an alarming inability to hold asteachers those who do begin a career in the classroom.Several experiments in the further <strong>edu</strong>cation of scienceteachers have sprung up in England. Some are full-timefor a term, while most are part-time of varying lengths,but none yet approach the thoroughness of the Japaneseprogramme which requires six months full-time refresherstudy every five years for all science teachers.Macquarie and <strong>Monash</strong> now both offer courses forthe further <strong>edu</strong>cation of science teachers, but these are,at this stage, optional and touch only a tiny proportionof the teachers. New pre-service courses to train scienceteachers have been slower to emerge, although both thetraditional undergraduate science course and the year ofprofessional teacher training have unsatisfactory features.The new demands on science teachers to make sciencemore attractive, to teach it as part of general <strong>edu</strong>cationand to make its nature and social significance explicit,underline the need for changes.At Chelsea College, within the <strong>University</strong> of London,a new one-year course for science graduates leads to aDiploma of Education. There is a minimurn core offormal lectures and for the rest of the year the studentsand staff work together in small seminar groups, integratingas much as possible the experiences of teachingpractice and the findings of the academic study of <strong>edu</strong>cation.The association of the Nuffield science curriculumprojects with this unit at Chelsea makes possiblethe easy familiarization of the students with the mostrecent materials and curricula ideas. A similar approachto preparing science graduates for teaching occurs atthe very strong centre for science <strong>edu</strong>cation of OhioState <strong>University</strong>. Once again, the integration of teachingexperience with academic findings is stressed and thesignificance of cultural and sociological context forteaching methods in science is a major emphasis. Inboth these courses full advantage is taken of the homogeneousbackground of the students as science graduates.As yet, there appear to be no such courses in Australia,although a radical revision along these lines is plannedfor science graduates at <strong>Monash</strong>.The training of teachers is only one aspect of theteacher problem; the more major one is the essentiallypolitical problem of retaining them in <strong>edu</strong>cation as acareer. when they. above all other teachers, have a basictraining which makes them highly marketable persons ina society essentially shorl of technically trained persons.JAPANESE CONSUL-GENERALPRESENTS BOOKSSeventy-two valuable Japanese books were presented to<strong>Monash</strong> on 24 March by the Japanese Consul-Generalin Melbourne, Mr N. Imajo, on behalf of the JapaneseGovernment.The Acting Vice-Chancellor, Professor K. C. Westfold,formally accepted the gift. The books, which areabout contemporary Japan, were then given to the <strong>University</strong>'sdepartment of Japanese.MR R. OSBORN APPOINTED AIDE-DE-CAMPTO THE QUEENMr Richard Osborn, a senior administrative officer onthe staff of the Academic Registrar, and secretary tothe faculty of Medicine from 1964 until the recentrotation of faculty secretaries,has been honouredby Her Majesty The Queenin being chosen as anAide - de - Camp to theQueen. The appointmentis for a term of two yearsexpiring in August 1971.Mr Osborn's appointmentstems from the occasionswhen he 'wears anotherhat'-in this instance the'hat' of Commandant ofthe Victoria <strong>University</strong>Squadron. an office he hasheld for the past ten years,commencing in the daysMr R. Osborn when there was only oneuniversity in Victoria andthis unit was then calledthe Melbourne <strong>University</strong> Squadron. The office ofCommandant is distinct from that of CommandingOfficer, and the role of the Commandant is primarilyone of liaison between t.he universities and the Air Forcein the interests of the Squadron and its undergraduatemembers, as well as 'showing the flag' at BirthdayLevees and other similar ceremonial occasions.Mr Osborn served as a night bom.ber pilot in theR.A.F. in England throughout the second world war,and was awarded the D.S.O. and D.F.C. in this capacity.He was twice wounded in action, and also spent nearlytwo years as a prisoner of war in Germany. As Commandantof the Victoria <strong>University</strong> Squadron he holdsthe rank of Wing Commander in the RA.A.F. Reserve,and it is in this capacity that he has now been appointedA.D.C. to the Queen.An A.D.C. is called upon to escort and assist theMonarch as occasions require - with the forthcomingroyal visit in 1970, Mr Osborn anticipates some measureof direct involvement in the tour but as yet no detailshave been notified to him.MEDICAL FACULTY AWARDSSECOND DOCTORATEDr D. M. de Kretser, from the department of Anatomy,has been awarded the degree of Doctor of Medicine.This is the second doctorate in Medicine to be awardedby <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> and the first in the basic medicalsciences.Dr de Kretser's thesis Studies on the Structure andFunction of the Human Testis is concerned with thestructural bases of male fertility and infertility. Dr deKreiser is a member of an advisory group at the EndocrineClinic of the Royal Women's Hospital and he hasbeen able to provide an electron microscopic assessmentof various forms of therapy used. He is at present onleave at the <strong>University</strong> of Washington in Seattle wherehe is continuing his studies on the mechanisms of hormonalcontrol of gonadal activity.14

UNIVERSITY CONFERS FIVE HONORARY DEGREESSince publication of the last issue of the Gazette fivefurther honorary degrees have been conferred by the<strong>University</strong>.Citation delivered by Professor R. R. Andrew on theoccasion of the conferring of the degree of Doctor ofScience honoris c<strong>au</strong>sa upon Sir Macfarlane Burnet:] present to you Frank Macfarlane Burnet, KnightBachelor, Member of the Order of Merit, Doctor ofScience, Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Laws, Fellowof the Royal College of Physicians,Fellow of the RoyalAustralasian College of Physicians,Fellow of the AmericanCollege of Physicians,President of the AustralianAcademy, Fellow of the RoyalSociety, Emeritus Professorof Experimental Medicine atthe <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne,Nobel L<strong>au</strong>reate.It is surely appropriate thatthis <strong>University</strong> should todayconfer a Doctorate of Scienceon this notable scientist whograduated in medicine at the<strong>University</strong> of Melbourne inSir Macfarlane Burnet1922 and whose research hasbeen crowned by such success,OUf new <strong>University</strong> and its medical school haveleaned heavily on the <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne both forstaff and the inspiration of many of its graduates. Fromthe foundation of <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong>, Sir Macfarlane,a dyed-in-the-wool Melbourne man, has been a memberof our faculty of Medicine, and his advice on importantmatters has been sought not infrequently and never withoutadvantage to ourselves, For this we are indeedgrateful.There is probably no contemporary Australian betterknown both here and abroad, nor any who has so welldeserved the many honours he has earned. I shall notattempt to describe his achievements which he haswritten about so objectively in his recent <strong>au</strong>tobiography.And it is impossible in a few words adequately to conveythe essence of such a world figure, or the ultimate valueof his work to science and medicine and thus to thecommunity. But I feel obliged, nonetheless, Sir, inpresenting to you this illustrious man, to try and singleout some characteristic which may exemplify his importanceto all who would work in the broad fields in whichhe has laboured with such remarkable success.While his intellect is clearly of the highest order, itis not so widely known that as an experimenter he hadfew rivals. His colleagues talk of the be<strong>au</strong>ty of hislaboratory technique, the excellence of his planning,and the inevitability of his success. He has published248 scientific papers, 158 reviews and he has writteneight books. It has been a source of wonder to manyfamous overseas workers how he has been able to accomplishsuch a vast and influential output of suchhigh quality. The probable answer lies in his logicalapproach to problems, the virtuosity of his bench work:it has always been done. and been done well and truly,once and for all time. And so he has sailed serenelythrough perilous scientific seas on a journey that onefeels can have no ending. Whatever his own beliefs,or ours, about the ultimate mysteries, I would suggestthat his work has in a sense earned him a form ofimmortality. As the result of his researches and theirfundamental effect on medicine and the biologicalsciences. all who work in these fields (and this includesgraduates of medicine) will have embedded somewherein their thinking or being, a bit of Burnet. and will bethe better for it.He is, indeed, one of our greatest living citizens andscientists.Citation delivered by the Acting Vice-Chancellor.Professor K. C. Westiold, on the occasion of the con[ering of the degree of Doctor of Laws honoris c<strong>au</strong>s<strong>au</strong>pon Sir Michael Chamberlin:Members and friends of <strong>Monash</strong> <strong>University</strong> will beaware of the subtle change that took place in our statusduring 1968. In that year we celebrated the tenth anniversaryof our foundation by an Act of Parliament ofthe sovereign State of Victoria. Those of us who havebeen at <strong>Monash</strong> since its beginning and are consciousof what has been achieved in this short span - ourstudent population has increased from zero to virtuallythe number attending the <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne atthe time of our foundation - would regard this year asan epoch marking the end of our first era - a corningof age. To us it seems right that the <strong>University</strong> shouldat this time recognize in a fitting manner one who hasrendered it outstanding service from the beginning andwho has now laid aside the burdens of office.Michael Chamberlin was a member of the originalInterim Council, formed in 1958 and consisting oftwenty-seven members, chosen to cover the wholespectrum of interests and abilities required to set thisgreat enterprise going. When the first permanent Councilwas established in ] 961 he was appointed by theGovernor-in-Council as one of the two members representingindustrial and commercial interests. Throughoutthe life of the Interim Council he had given to the<strong>University</strong> the benefit of his long experience in commerceand other fields, and Council recognized his greatcontribution when it elected him as its first DeputyChancellor, a position he continued to occupy until hisretirement last year.At a time when critical attention is being paid to theworking of a university I am glad to have this opportunityto pay tribute to the generous service to <strong>Monash</strong><strong>University</strong> freely undertaken by members of our Council,particularly in its committees. Here the special expertiseof those who have had fruitful experience in theworld outside the <strong>University</strong> is available to assist the<strong>University</strong> in its multifarious non-academic functions,without which the essential academic activities would beseriously inhibited. Of these Michael Chamberlin canfairly be sure to have shouldered an ample share.In 1964 his services to the community were recognizedby the award of a Knighthood by Her MajestyThe Queen. Together with the establishment of <strong>Monash</strong><strong>University</strong> on a firm foundation, it must have affordedhim further deep personal satisfaction to see his laboursto found the <strong>University</strong>'S first affiliated college, MannixIS

MONASH UNIVERSITY GAZETTECollege, brought to fruition with its opening at thebeginning of the 1969 academic year. This satisfactionhas been compounded by the more recent recognitionof his long record of service to the Roman CatholicChurch and to <strong>edu</strong>cation by His Holiness Pope P<strong>au</strong>l VIin creating him a Knight Commander of the Order ofPius.Citation delivered hy Proi essor B. W. Holloway onthe occasion oj the canierring of the degree of Doctorof Science honoris c<strong>au</strong>sa upon Sir Frederick White:Today we are here to honour an eminent Australianscientist. It is therefore proper on this occasion notonly to record those aspects of his career by which hehas attained his position ofdistinction, but also how wecome to recognize such highability and achievement.In science, Mr Chancellor,we can precisely measure andevaluate many aspects of thephysical and biological world.Yet, by contrast, we have nosuch absolute standards forrecognizing scientific talentand acumen. To overcomethis problem, scientists relyon various collective processesof evaluation by theirpeers, surely always the mostSir Frederick White critical of <strong>au</strong>diences.It is by these high standardsof assessment that Sir Frederick White emerges as thescientist's scientist - and his achievements are the evidencefor the high value placed on him, not only byhis fellow scientists, bUI also by governments andinstitutions.At the age of thirty-two, he was appointed professorof Physics at Canterbury <strong>University</strong> College. At thirtyseven,he became chief of the Division of Radiophysics,C.S.tR.O. Four years later, he was appointed to theexecutive committee of that organization, where he hasremained to become chairman of the executive ofC.S.J.R.O.Not only during this period has he actively championedthe expanded role of C.S,tR,O. in Australian and internationalscience, but, through his personal scientificdistinction, he has continued to receive those honourswhich can only be bestowed through the confidence ofhis fellow scientists-Fellow of the Australian Academyof Science, Fellow of the Royal Society. Fellow of theInstitute of Physics, President of the Australian andNew Zealand Association for the Advancement ofScience. An even wider recognition of his service camein 1962 when he was made Knight Commander of theOrder of the British Empire.He has displayed excellence not only as a scientificadministrator, but also as an experimental scientist, forin his early years he was one of Appleton's colleaguesat King's College, London, at the time when this laboratorywas one of the world leaders in experimentalphysics.His life has not been restricted to either the laboratorybench or the office desk. He has travelled extensivelyoverseas to establish those personal contacts withscientists and other notable personalities which are soessential to an isolated country like Australia. His specialrole in the financing of Australian research has broughthim in contact with many trade and industrial researchassociations.He has a special feeling for the outdoor life. Theproximity of Canberra to the trout streams of the SnowyMountains has not escaped his notice and he is an excellentexample of one who is both the compleat anglerand the complete scientist.His outdoor interests and, I feel sure, the continuedsuccess of all his professional activities, have been aidedby his wife, Lady Elizabeth White, herself a person ofconsiderable distinction and achievement and possiblyone of the few Australian housewives who has practisedmountaineering in the Himalayas.Despite all these activities, Sir Frederick has foundtime to help us here at <strong>Monash</strong>, and he was one of thefirst members of the Council of this <strong>University</strong>. Hisadvice during the early period of this <strong>University</strong> hasbeen much valued.Citation delivered by Professor P. L. Waller all theoccasion of the conferring oj the degree of Doctor ofLaws honoris c<strong>au</strong>sa upon The Honourable Mr JusticeThomas Weetman Smith:It used to be said that the common law of Englandresided in the breasts of Her Majesty's judges. MrJ ustice Darling once said that to Counsel, who replied,'a very happy residence',which in its turn led thejudge to say, 'that does notjustify what are called exploratoryoperations'. A betterknowledge of legal physiologyand judicial anatomy leads ustoday to conclude that it iswhat is in the minds of thejudges that is of the greatestimportance in the expositionand development of the livinglaw.It is unnecessary here, MrChancellor, to speak at lengthMr Justice Thomas Smith about the modern judges' rolein law-making. It is enoughto state that that role is a leading and vital one in ourlegal system. The Honourable Thomas Weetman Smithhas been one of the Justices of the Supreme Court ofVictoria since 10 February 1950. In almost two decadesof judicial service he has shown himself completelyfitted for the part of judicial law-maker, as a memberof a court whose judgments attract keen attention andreceive generous approval not only in Victoria but alsoin the rest of the common law world.His many judgments, at first instance, on review ofdecisions in magistrates' courts, and as a member of theFull Court hearing appeals from all Victorian courts.have included a very large number which are regardedby all legal scholars (which term is meant to be allembracing)as statements of legal principle and doctrineof the first rank. They are marked by the characteristicsof order and clear expression, and informed always bya concern for justice and true human understanding.He is no aloof spokesman 'from the chill and distantheights', which Cardozo warned his judicial brethren notto occupy, but is conscious of 'the great tides and cur16

ents which engulf the rest of men'. It was a formerMinister of State, himself a lawyer, who expressed ageneral view of the graduand when he said in Parliament:'There will never be a better lawyer in theSupreme Court than Mr Justice Smith.' In a happydisplay of bi-partisan and bi-cameral unanimity, aMember of the Legistlative Council complemented thattribute by saying: 'He is a great lawyer and this Stateis deeply indebted to him.'It should not be forgotten that Mr Justice Smith, likeevery judge, discharges day-by-day the demanding andoften, I am sure, nerve-racking responsibilty of decidingparticular cases between particular litigants. This isthe business of the judge. He has presided over scoreupon score of cases, civil and criminal, since his elevationto the bench. His work is recorded, then, not only inthe pages of the Victorian Reports, but also in the livesof many thousands of the citizens in this community.It is with this in mind that what has already been saidabout his contributions to the exposition, elucidation anddevelopment of the law in this State takes its full colour.Aware, in all detail, of what the law is, Mr JusticeSmith has made important suggestions for what it oughtto be. He has been a witness before the Statute LawRevision Committee of the Parliament of Victoria, andthere received high commendation for the assistance heprovided. Since April 1962, he has been chairman ofthe Chief Justice's Law Reform Committee, which bringstogether judges, barristers, solicitors and law teachers,to consider specific criticisms of our legal system and togive form, on occasion, to specific proposals for change.It is the only standing law reform committee in thisState and its hands are not left idle. As its chairman,Mr Justice Smith has presided over its meetings in sucha way as to bring the best talents available to the considerationof the questions referred by government, theprofessional bodies or individual legal practitioners.Mr Justice Smith has not confined his contributions tolegal scholarship to those he has made, and continuesto make, in the office of judge. The law, perhaps morethan any other of the great professions, has alwaystaken a corporate interest in, and responsibility for, the<strong>edu</strong>cation and training of those who seek to join it.Today, in this <strong>University</strong>'s law school, now firmly establishedwith its large faculty of full-time teachers of law,there is still maintained a strong connection between theschool and the legal profession; and members of theprofession continue to play a much more than formalrole in the on-going <strong>edu</strong>cation of law students. In thedays before the second world war, and for some yearsthereafter, a very large part of the formal teaching inlaw in our sister school in the <strong>University</strong> of Melbournewas provided by independent lecturers in law, appointedLE TRETEAU DE PARIS VISITS MONASHThe Parisian theatrical group, Le Trete<strong>au</strong> de Paris, madeits third visit to Australia in 1969 and, for the first time,gave performances at <strong>Monash</strong> earlier this year. Thecompany presented two plays - Moliere's TartufJe andSamuel Beckett's En Attendant Godot.The tour was sponsored in Australia by the AustralianElizabethan Theatre Trust under the <strong>au</strong>spices ofL'Association Francaise d'Action Artistique of the FrenchGovernment, with the assistance and patronage of theAustralian Council for the Arts.from the ablest of the practising profession. You, MrChancellor, will know something of this yourself. TomSmith was lecturer in the Law of Contract and PersonalProperty in the <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne from 1933 to1941, and lecturer in the Law of Contract (a change oftitle following a change in syllabus) from 1941 to 1946,when he was compelled by the pressure of professionalduties to resign his post. It can be seen, then, that itwas for no insignificant period that he discharged, withsignal success, the duty of bringing students to an understandingof a most important branch of their legalstudies. For very many of them, now practising lawin Victoria, and, in a number of cases, occupying judicialoffice, their grounding in Contract is forever associatednot just with Anson's classic text but with Tom Smith'sexposition and commentary.And he has not forgotten legal <strong>edu</strong>cation, or withdrawnfrom real participation in it, in the face of thedemands of his office. In 1962 the Council of LegalEducation determined to institute teaching in law forthose law students unable to gain entry, bec<strong>au</strong>se of quotarestrictions, to the <strong>University</strong> of Melbourne's law school.It was Mr Justice Smith who accepted the office ofchairman of the Legal Education Committee of thatcouncil, to which committee was entrusted the responsibilityfor the institution of those courses in law, theirdevelopment and their overall superintendence. In theeight years since that step was taken the graduand hasspent much time and a great deal of effort to makesure that the courses offered were of the same standardsas those set in the universities. He has taken the keenestinterest in the selection of lecturers and tutors, andshown the same interest and concern in the regularprogress of the students. He has had the satisfaction ofseeing students who have successfully completed thecouncil's course, in conjunction with service underArticles of Clerkship, gain admission as barristers andsolicitors of the Supreme Court of Victoria.We in this <strong>University</strong> know, and today acknowledge,how much counsel and assistance Me Justice Smithhas given to this law school. He accepted an invitationto become a member of the Advisory Committee forthe to-be-established faculty of Law, instituted by theProfessorial Board in 1963; he served on that committeeuntil the faculty of Law came into being on 28September 1965. He became a member of the facultyof Law and of its faculty board, representing the judgesof the Supreme Court of Victoria, when it was formallyestablished. He is a member today.This <strong>University</strong> honours itself on this day when itbrings Mr Justice Smith into its membership as anhonorary graduate. He is a great judge and a greatjurist who has made splendid contributions to legalscholarship and who, at the same time, has taken amost important part in the planning and developmentof the <strong>edu</strong>cation of the lawyers of tomorrow.Citation delivered by Dr J. A. L. Matheson on theoccasion of the conferring of the degree of Doctor ofScience honoris c<strong>au</strong>sa upon Sir Linder Brown:Speaking as a former Whitworth observer I commendto you another former Whitworth observer for admissionto an honorary degree.Sir Lindor Brown and I have at least three thingsin common - we are both graduates of Manchester<strong>University</strong>; we both, as postgraduate students, earned a17