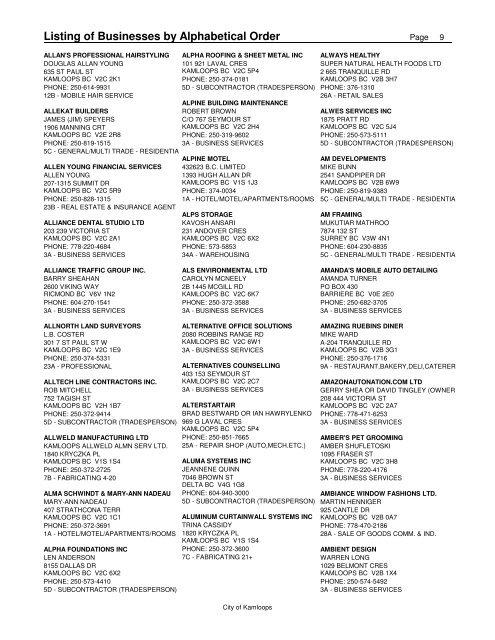

Listing of Businesses by Alphabetical Order - City of Kamloops

Listing of Businesses by Alphabetical Order - City of Kamloops

Listing of Businesses by Alphabetical Order - City of Kamloops

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

H. Whitehead, P.J. Richerson / Evolution and Human Behavior 30 (2009) 261–273269low-frequency environmental change may reduce meanfitness and lead to population decline.The model does not include a prominent element <strong>of</strong> bothhistorical collapses in human societies, and our currentpredicament: the influence <strong>of</strong> humans and our cultures onenvironmental change. These can exacerbate the modelscenario in two related modes. First, cultural behavior can,and <strong>of</strong>ten does, stabilize environmental variation throughniche construction (Laland, Odling-Smee, & Feldman,2000). Humans do this in many ways including the storageand transport <strong>of</strong> food and other resources. This artificialenvironmental stabilization, while it works, reduces theadvantages <strong>of</strong> individual learning and makes it more likelythat social learning, and cultural conformism, will becomevery common or fixed in the population. The command andcontrol institutions necessary to make complex nicheconstructions work may restrict the capacity for innovationto a small elite who are overwhelmed <strong>by</strong> red noise events.Even the most sophisticated niche constructions are bound tobe challenged <strong>by</strong> red environmental events, and when theyfail, the environment may change very rapidly indeedbecause <strong>of</strong> human influence (Diamond, 2005), a situationpotentially disastrous for a population <strong>of</strong> largely conformistsocial learners. Currently, successful methods <strong>of</strong> stabilizingthe local environments <strong>of</strong> individual humans throughheating, air-conditioning, transport and other systemswhich use fossil fuels are simultaneously destabilizing theglobal environment. Climatologists warn that anthropogenicclimate change will inevitably lead to surprises (NationalResearch Council, 2002).Richerson and Boyd (2005) suggest that the capacity forcomplex social learning and culture arose in humans duringthe highly variable Pleistocene climate. Such an environment,with high variation over many time scales, may haveparticularly favored a contingent individual/social learningstrategy. However, during the more recent Holocene, climatehas been much less variable (Ditlevsen et al., 1996),potentially providing an environment favoring pure sociallearning strategies which could invade, become verycommon or fixed, and lead to societal collapse. The variance<strong>of</strong> the Holocene climate, while much smaller than that <strong>of</strong> thelate Pleistocene, is dominated <strong>by</strong> abrupt low-frequencyevents (Mayewski et al., 2004); the spectrum remains redeven if the intensity <strong>of</strong> variation was decreased across thespectrum. Some evidence suggests that the Holocene mighthave had this effect. Human encephalization (brain sizerelative to body size) declined slightly in the Holocenerelative to the Late Pleistocene (Ruff, Trinkhaus, & Holliday,1997), while the size <strong>of</strong> the cerebellum relative to thecerebral hemispheres increased (Weaver, 2006). Weaver(2006) suggests that the functional significance <strong>of</strong> thischange has to do with better processing <strong>of</strong> rule-based culturalinformation. Guthrie's (2005) analysis <strong>of</strong> Upper Paleolithicart suggests that the people who lived under highlyfluctuating climates were highly naturalistic. Supernaturalthemes were scarce in their art compared to that <strong>of</strong> Holocenehunter-gatherers. Rappaport (1979: p. 100) argued thatreligion functions “to drape nature in supernatural veils… toprovide her with some protection against human folly andexcess.” That is, supernatural beliefs may protect culturaladaptations from skeptical empirical examination. AsRappaport suggested, this may be highly adaptive to protecta complex fine-tuned cultural adaptation from excessivetinkering <strong>by</strong> inevitably error prone individual learning andcollective innovation. But when the inevitable challengecomes, supernatural veils may defeat attempts to learn,innovate and borrow solutions to the new problem. Somecombination <strong>of</strong> genetic and cultural changes might well havedecreased individual learning relative to social learning inthe Holocene, leading to a risk <strong>of</strong> collapse in the face <strong>of</strong> rarered noise events.While the population sizes considered during the modelruns (500, 1500 and 5000 breeding individuals) are withinthe ranges <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the archetypal collapsed societies (theGreenland Norse for example), they are much smaller thanothers (such as the Maya) and minuscule in comparison withtoday's interconnected global human community. Hardwarelimitations mean that individual-based models <strong>of</strong> thisphenomenon cannot be run with populations <strong>of</strong> more thansome thousand individuals. Can we reasonably extrapolatethe results <strong>of</strong> such model runs upwards to scales <strong>of</strong> millions(the Maya) or billions (the current human population)? Theresults <strong>of</strong> the model runs indicate that increased populationsize reduces the likelihood <strong>of</strong> fixation <strong>of</strong> social learning andthus extirpation (Table 1). Additionally, with very largepopulation size, mutant or innovative (in the case <strong>of</strong>culturally determined learning strategies) individuals whomight realign behavior in more environmentally appropriateways are more likely to arise, although their impact onpopulation behavior will be correspondingly smaller. Thus,extrapolation to much larger population sizes is moot,although the case <strong>of</strong> the Maya collapse (Webster, 2002)seems to fit many aspects <strong>of</strong> the model. We speculate thatlarge populations will mitigate the chances <strong>of</strong> extirpation andthe severity <strong>of</strong> collapses short <strong>of</strong> extirpation. Largepopulations, all else equal, will tend to have at least a fewinnovators who can introduce new adaptations. Henrich(2004) modeled the equilibrium toolkit complexity <strong>of</strong> asociety as a function <strong>of</strong> population size. His modelessentially depends upon uncommon reinvention <strong>of</strong> complexartifacts whose complexity is degraded in everyday transmissionevents. The same reinvention process should furnishadaptive novelties in a changing environment.The time scales <strong>of</strong> the collapses in the model, about 2600time units or 65 generations from fixation (Table 1), arereassuringly long in historical terms. However, as notedabove, if the inheritance <strong>of</strong> learning strategy is throughconformist culture or if culture affects environmentalchange, the speed <strong>of</strong> the process may greatly increase. Insuch cases, collapse could occur much more quickly thansuggested <strong>by</strong> the results in Table 1. Turchin's (2003) review<strong>of</strong> the rise and collapse <strong>of</strong> agrarian states suggests that typical