Sugar Cane And Indigenous People - Sucre Ethique

Sugar Cane And Indigenous People - Sucre Ethique

Sugar Cane And Indigenous People - Sucre Ethique

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

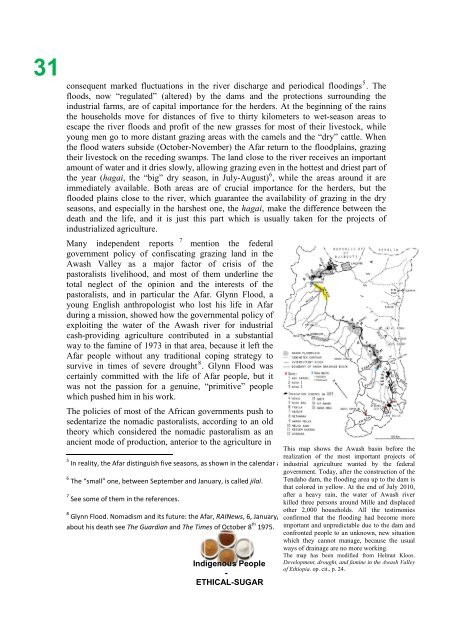

31consequent marked fluctuations in the river discharge and periodical floodings 5 . Thefloods, now “regulated” (altered) by the dams and the protections surrounding theindustrial farms, are of capital importance for the herders. At the beginning of the rainsthe households move for distances of five to thirty kilometers to wet-season areas toescape the river floods and profit of the new grasses for most of their livestock, whileyoung men go to more distant grazing areas with the camels and the “dry” cattle. Whenthe flood waters subside (October-November) the Afar return to the floodplains, grazingtheir livestock on the receding swamps. The land close to the river receives an importantamount of water and it dries slowly, allowing grazing even in the hottest and driest part ofthe year (hagai, the “big” dry season, in July-August) 6 , while the areas around it areimmediately available. Both areas are of crucial importance for the herders, but theflooded plains close to the river, which guarantee the availability of grazing in the dryseasons, and especially in the harshest one, the hagai, make the difference between thedeath and the life, and it is just this part which is usually taken for the projects ofindustrialized agriculture.Many independent reports 7 mention the federalgovernment policy of confiscating grazing land in theAwash Valley as a major factor of crisis of thepastoralists livelihood, and most of them underline thetotal neglect of the opinion and the interests of thepastoralists, and in particular the Afar. Glynn Flood, ayoung English anthropologist who lost his life in Afarduring a mission, showed how the governmental policy ofexploiting the water of the Awash river for industrialcash-providing agriculture contributed in a substantialway to the famine of 1973 in that area, because it left theAfar people without any traditional coping strategy tosurvive in times of severe drought 8 . Glynn Flood wascertainly committed with the life of Afar people, but itwas not the passion for a genuine, “primitive” peoplewhich pushed him in his work.The policies of most of the African governments push tosedentarize the nomadic pastoralists, according to an oldtheory which considered the nomadic pastoralism as anancient mode of production, anterior to the agriculture inThis map shows the Awash basin before therealization of the most important projects of5 In reality, the Afar distinguish five seasons, as shown in the calendar above. industrial agriculture wanted by the federalgovernment. Today, after the construction of the6 The “small” one, between September and January, is called jilal. Tendaho dam, the flooding area up to the dam isthat colored in yellow. At the end of July 2010,7 after a heavy rain, the water of Awash riverSee some of them in the references.killed three persons around Mille and displacedother 2,000 households. All the testimonies8 Glynn Flood. Nomadism and its future: the Afar, RAINews, 6, January/February 1975, pp. 5-9. For detailsabout his death see The Guardian and The Times of October 8 th 1975.Ethicl<strong>Indigenous</strong> <strong>People</strong>-ETHICAL-SUGARconfirmed that the flooding had become moreimportant and unpredictable due to the dam andconfronted people to an unknown, new situationwhich they cannot manage, because the usualways of drainage are no more working.The map has been modified from Helmut Kloos.Development, drought, and famine in the Awash Valleyof Ethiopia. op. cit., p. 24.