SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

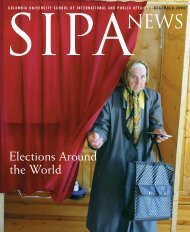

Supporters of Ukrainian<br />

opposition leader Viktor<br />

Yanukovych display his<br />

party flags, with a statue<br />

of Soviet state founder<br />

Vladimir Lenin in the<br />

background, at a campaign<br />

rally in the Crimean capital<br />

Simferopol, Ukraine, in<br />

December 2009.<br />

Post-Soviet Identity and Foreign Policy Formation<br />

in Ukraine, Estonia, and Latvia By Tim Sandole<br />

Ukraine, Estonia, and Latvia have two<br />

geopolitical similarities: each was a<br />

subject of the Soviet Union, and each<br />

shares a border with Russia. Yet despite<br />

their proximities to Russia and their respective<br />

experiences with Communism, the two Baltic states<br />

differ remarkably from Ukraine in their policy of<br />

engagement with Russia and the West. Upon the<br />

Soviet Union’s disintegration, Estonia and Latvia<br />

aggressively looked west and embraced NATO,<br />

while Ukraine looked west and continued looking<br />

east, maintaining ties with its former master while<br />

attempting to create a new relationship with the<br />

United States and Western institutions. Why did<br />

these three countries, which were geographically<br />

similar from the outset of the post-Cold War era, differ<br />

so remarkably in their foreign policy orientation?<br />

Their disparate foreign policies are a direct result of<br />

20 <strong>SIPA</strong> NEWS<br />

their respective national identities, all of which came<br />

to fruition during the Soviet Union’s disintegration.<br />

Ukraine’s “Middle-of-the-Road”<br />

Approach<br />

Ethnic Russians formed the largest minority in<br />

Ukraine, making up 22 percent of the population<br />

according to the 1989 census. Throughout the<br />

Soviet period, it was common for Russians to traverse<br />

various Soviet Socialist Republics because<br />

of favorable opportunities provided to them by<br />

the Communist Party. And even after Ukrainian<br />

independence, ethnic Russians had no reason to<br />

fear for their well-being, because Ukraine took<br />

a “middle ground” approach to policy formulation,<br />

where ethnic Russians and Ukrainians<br />

would be on an equal legal footing. <strong>Columbia</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> professor Alfred Stepan explains that<br />

Ukraine “decided to recognize and institutionally<br />

give support to more than one cultural identity,<br />

even a national identity, in the state.” This<br />

moderate approach stemmed from the makeup<br />

of Ukrainian regional identity. Nationalist and<br />

anti-Russian sentiments have historically characterized<br />

western Ukrainian regions, notably in<br />

Galicia, where the Austrian Hapsburg Empire<br />

once ruled. This left a Western-oriented legacy<br />

in western Ukraine. Pro-Russian political values<br />

have been historically codified in eastern<br />

Ukraine, notably in Donetsk, as a consequence of<br />

many years of Russian Czarist rule. This regional<br />

dichotomy spawned three political ideologies in<br />

the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhvna Rada) at the<br />

outset of Ukrainian independence.<br />

The political left embraced the Soviet idea<br />

of Ukrainian origin belonging to an East Slavic