SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANewS - SIPA - Columbia University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Development<br />

through Football:<br />

A Vision for<br />

the Balkans<br />

BY BEHAR XHARRA AND MARTIN WAEHLISCH<br />

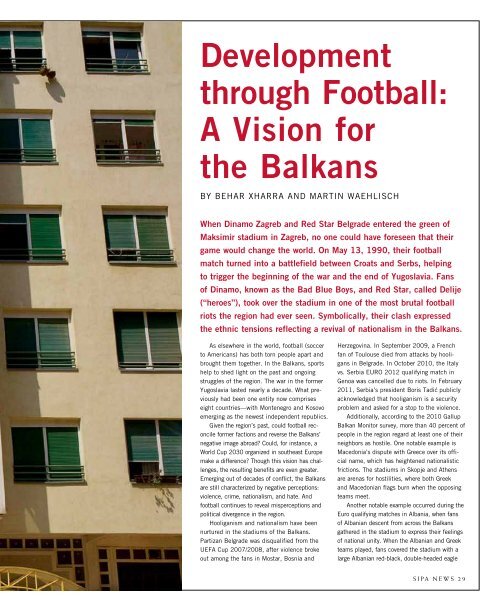

When Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade entered the green of<br />

Maksimir stadium in Zagreb, no one could have foreseen that their<br />

game would change the world. On May 13, 1990, their football<br />

match turned into a battlefield between Croats and Serbs, helping<br />

to trigger the beginning of the war and the end of Yugoslavia. Fans<br />

of Dinamo, known as the Bad Blue Boys, and Red Star, called Delije<br />

(“heroes”), took over the stadium in one of the most brutal football<br />

riots the region had ever seen. Symbolically, their clash expressed<br />

the ethnic tensions reflecting a revival of nationalism in the Balkans.<br />

As elsewhere in the world, football (soccer<br />

to Americans) has both torn people apart and<br />

brought them together. In the Balkans, sports<br />

help to shed light on the past and ongoing<br />

struggles of the region. The war in the former<br />

Yugoslavia lasted nearly a decade. What previously<br />

had been one entity now comprises<br />

eight countries—with Montenegro and Kosovo<br />

emerging as the newest independent republics.<br />

Given the region’s past, could football reconcile<br />

former factions and reverse the Balkans’<br />

negative image abroad? Could, for instance, a<br />

World Cup 2030 organized in southeast Europe<br />

make a difference? Though this vision has challenges,<br />

the resulting benefits are even greater.<br />

Emerging out of decades of conflict, the Balkans<br />

are still characterized by negative perceptions:<br />

violence, crime, nationalism, and hate. And<br />

football continues to reveal misperceptions and<br />

political divergence in the region.<br />

Hooliganism and nationalism have been<br />

nurtured in the stadiums of the Balkans.<br />

Partizan Belgrade was disqualified from the<br />

UEFA Cup 2007/2008, after violence broke<br />

out among the fans in Mostar, Bosnia and<br />

Herzegovina. In September 2009, a French<br />

fan of Toulouse died from attacks by hooligans<br />

in Belgrade. In October 2010, the Italy<br />

vs. Serbia EURO 2012 qualifying match in<br />

Genoa was cancelled due to riots. In February<br />

2011, Serbia’s president Boris Tadić publicly<br />

acknowledged that hooliganism is a security<br />

problem and asked for a stop to the violence.<br />

Additionally, according to the 2010 Gallup<br />

Balkan Monitor survey, more than 40 percent of<br />

people in the region regard at least one of their<br />

neighbors as hostile. One notable example is<br />

Macedonia’s dispute with Greece over its official<br />

name, which has heightened nationalistic<br />

frictions. The stadiums in Skopje and Athens<br />

are arenas for hostilities, where both Greek<br />

and Macedonian flags burn when the opposing<br />

teams meet.<br />

Another notable example occurred during the<br />

Euro qualifying matches in Albania, when fans<br />

of Albanian descent from across the Balkans<br />

gathered in the stadium to express their feelings<br />

of national unity. When the Albanian and Greek<br />

teams played, fans covered the stadium with a<br />

large Albanian red-black, double-headed eagle<br />

<strong>SIPA</strong> NEWS 29