SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

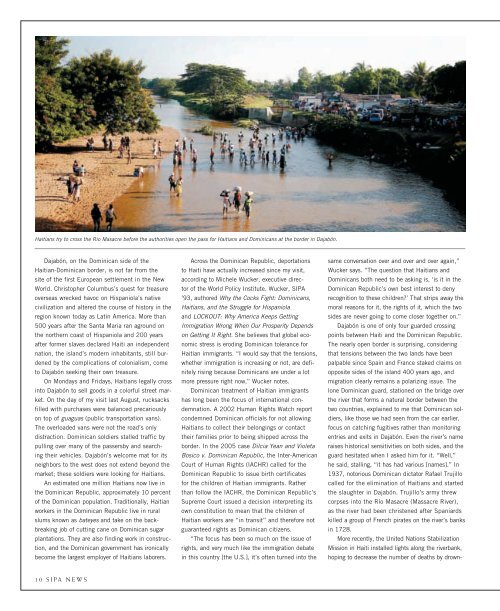

Haitians try to cross the Rio Masacre before the authorities open the pass for Haitians and Dominicans at the border in Dajabón.<br />

Dajabón, on the Dominican side of the<br />

Haitian-Dominican border, is not far from the<br />

site of the first European settlement in the New<br />

World. Christopher Columbus’s quest for treasure<br />

overseas wrecked havoc on Hispaniola’s native<br />

civilization and altered the course of history in the<br />

region known today as Latin America. More than<br />

500 years after the Santa Maria ran aground on<br />

the northern coast of Hispaniola and 200 years<br />

after former slaves declared Haiti an independent<br />

nation, the island’s modern inhabitants, still burdened<br />

by the complications of colonialism, come<br />

to Dajabón seeking their own treasure.<br />

On Mondays and Fridays, Haitians legally cross<br />

into Dajabón to sell goods in a colorful street market.<br />

On the day of my visit last August, rucksacks<br />

filled with purchases were balanced precariously<br />

on top of guaguas (public transportation vans).<br />

The overloaded vans were not the road’s only<br />

distraction. Dominican soldiers stalled traffic by<br />

pulling over many of the passersby and searching<br />

their vehicles. Dajabón’s welcome mat for its<br />

neighbors to the west does not extend beyond the<br />

market; these soldiers were looking for Haitians.<br />

An estimated one million Haitians now live in<br />

the Dominican Republic, approximately 10 percent<br />

of the Dominican population. Traditionally, Haitian<br />

workers in the Dominican Republic live in rural<br />

slums known as bateyes and take on the backbreaking<br />

job of cutting cane on Dominican sugar<br />

plantations. They are also finding work in construction,<br />

and the Dominican government has ironically<br />

become the largest employer of Haitians laborers.<br />

10 <strong>SIPA</strong> NEWS<br />

Across the Dominican Republic, deportations<br />

to Haiti have actually increased since my visit,<br />

according to Michele Wucker, executive director<br />

of the World Policy Institute. Wucker, <strong>SIPA</strong><br />

’93, authored Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans,<br />

Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola<br />

and LOCKOUT: Why America Keeps Getting<br />

Immigration Wrong When Our Prosperity Depends<br />

on Getting It Right. She believes that global economic<br />

stress is eroding Dominican tolerance for<br />

Haitian immigrants. “I would say that the tensions,<br />

whether immigration is increasing or not, are definitely<br />

rising because Dominicans are under a lot<br />

more pressure right now,” Wucker notes.<br />

Dominican treatment of Haitian immigrants<br />

has long been the focus of international condemnation.<br />

A 2002 Human Rights Watch report<br />

condemned Dominican officials for not allowing<br />

Haitians to collect their belongings or contact<br />

their families prior to being shipped across the<br />

border. In the 2005 case Dilcia Yean and Violeta<br />

Bosico v. Dominican Republic, the Inter-American<br />

Court of Human Rights (IACHR) called for the<br />

Dominican Republic to issue birth certificates<br />

for the children of Haitian immigrants. Rather<br />

than follow the IACHR, the Dominican Republic’s<br />

Supreme Court issued a decision interpreting its<br />

own constitution to mean that the children of<br />

Haitian workers are “in transit” and therefore not<br />

guaranteed rights as Dominican citizens.<br />

“The focus has been so much on the issue of<br />

rights, and very much like the immigration debate<br />

in this country [the U.S.], it’s often turned into the<br />

same conversation over and over and over again,”<br />

Wucker says. “The question that Haitians and<br />

Dominicans both need to be asking is, ‘is it in the<br />

Dominican Republic’s own best interest to deny<br />

recognition to these children?’ That strips away the<br />

moral reasons for it, the rights of it, which the two<br />

sides are never going to come closer together on.”<br />

Dajabón is one of only four guarded crossing<br />

points between Haiti and the Dominican Republic.<br />

The nearly open border is surprising, considering<br />

that tensions between the two lands have been<br />

palpable since Spain and France staked claims on<br />

opposite sides of the island 400 years ago, and<br />

migration clearly remains a polarizing issue. The<br />

lone Dominican guard, stationed on the bridge over<br />

the river that forms a natural border between the<br />

two countries, explained to me that Dominican soldiers,<br />

like those we had seen from the car earlier,<br />

focus on catching fugitives rather than monitoring<br />

entries and exits in Dajabón. Even the river’s name<br />

raises historical sensitivities on both sides, and the<br />

guard hesitated when I asked him for it. “Well,”<br />

he said, stalling, “it has had various [names].” In<br />

1937, notorious Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo<br />

called for the elimination of Haitians and started<br />

the slaughter in Dajabón. Trujillo’s army threw<br />

corpses into the Río Masacre (Massacre River),<br />

as the river had been christened after Spaniards<br />

killed a group of French pirates on the river’s banks<br />

in 1728.<br />

More recently, the United Nations Stabilization<br />

Mission in Haiti installed lights along the riverbank,<br />

hoping to decrease the number of deaths by drown-