SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

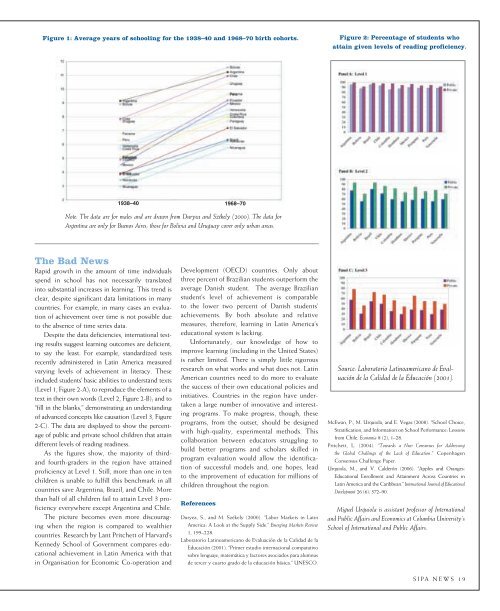

Figure 1: Average years of schooling for the 1938–40 and 1968–70 birth cohorts.<br />

The Bad News<br />

Rapid growth in the amount of time individuals<br />

spend in school has not necessarily translated<br />

into substantial increases in learning. This trend is<br />

clear, despite significant data limitations in many<br />

countries. For example, in many cases an evaluation<br />

of achievement over time is not possible due<br />

to the absence of time series data.<br />

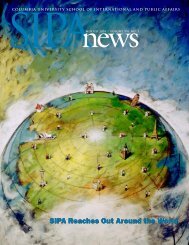

Despite the data deficiencies, international testing<br />

results suggest learning outcomes are deficient,<br />

to say the least. For example, standardized tests<br />

recently administered in Latin America measured<br />

varying levels of achievement in literacy. These<br />

included students’ basic abilities to understand texts<br />

(Level 1, Figure 2-A); to reproduce the elements of a<br />

text in their own words (Level 2, Figure 2-B); and to<br />

“fill in the blanks,” demonstrating an understanding<br />

of advanced concepts like causation (Level 3, Figure<br />

2-C). The data are displayed to show the percentage<br />

of public and private school children that attain<br />

different levels of reading readiness.<br />

As the figures show, the majority of third-<br />

and fourth-graders in the region have attained<br />

proficiency at Level 1. Still, more than one in ten<br />

children is unable to fulfill this benchmark in all<br />

countries save Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. More<br />

than half of all children fail to attain Level 3 proficiency<br />

everywhere except Argentina and Chile.<br />

The picture becomes even more discouraging<br />

when the region is compared to wealthier<br />

countries. Research by Lant Pritchett of Harvard’s<br />

Kennedy School of Government compares educational<br />

achievement in Latin America with that<br />

in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and<br />

1938–40 1968–70<br />

Note: The data are for males and are drawn from Duryea and Székely (2000). The data for<br />

Argentina are only for Buenos Aires; those for Bolivia and Uruguay cover only urban areas.<br />

Development (OECD) countries. Only about<br />

three percent of Brazilian students outperform the<br />

average Danish student. The average Brazilian<br />

student’s level of achievement is comparable<br />

to the lower two percent of Danish students’<br />

achievements. By both absolute and relative<br />

measures, therefore, learning in Latin America’s<br />

educational system is lacking.<br />

Unfortunately, our knowledge of how to<br />

improve learning (including in the United States)<br />

is rather limited. There is simply little rigorous<br />

research on what works and what does not. Latin<br />

American countries need to do more to evaluate<br />

the success of their own educational policies and<br />

initiatives. Countries in the region have undertaken<br />

a large number of innovative and interesting<br />

programs. To make progress, though, these<br />

programs, from the outset, should be designed<br />

with high-quality, experimental methods. This<br />

collaboration between educators struggling to<br />

build better programs and scholars skilled in<br />

program evaluation would allow the identification<br />

of successful models and, one hopes, lead<br />

to the improvement of education for millions of<br />

children throughout the region.<br />

References<br />

Duryea, S., and M. Székely (2000). “Labor Markets in Latin<br />

America: A Look at the Supply Side.” Emerging Markets Review<br />

1, 199–228.<br />

Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la<br />

Educación (2001). “Primer estudio internacional comparativo<br />

sobre lenguaje, matemática y factores asociados para alumnus<br />

de tercer y cuarto grado de la educación básica.” UNESCO.<br />

Figure 2: Percentage of students who<br />

attain given levels of reading proficiency.<br />

Source: Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación<br />

de la Calidad de la Educación (2001).<br />

McEwan, P., M. Urquiola, and E. Vegas (2008). “School Choice,<br />

Stratification, and Information on School Performance: Lessons<br />

from Chile. Economia 8 (2), 1–28.<br />

Pritchett, L. (2004). “Towards a New Consensus for Addressing<br />

the Global Challenge of the Lack of Education.” Copenhagen<br />

Consensus Challenge Paper.<br />

Urquiola, M., and V. Calderón (2006). “Apples and Oranges:<br />

Educational Enrollment and Attainment Across Countries in<br />

Latin America and the Caribbean.” International Journal of Educational<br />

Development 26 (6): 572–90.<br />

Miguel Urquiola is assistant professor of International<br />

and Public Affairs and Economics at <strong>Columbia</strong> <strong>University</strong>’s<br />

School of International and Public Affairs.<br />

<strong>SIPA</strong> NEWS 19