SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

SIPANEWS - SIPA - Columbia University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

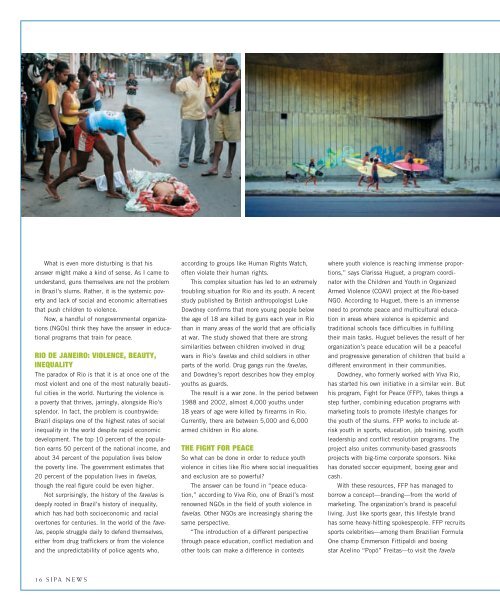

What is even more disturbing is that his<br />

answer might make a kind of sense. As I came to<br />

understand, guns themselves are not the problem<br />

in Brazil’s slums. Rather, it is the systemic poverty<br />

and lack of social and economic alternatives<br />

that push children to violence.<br />

Now, a handful of nongovernmental organizations<br />

(NGOs) think they have the answer in educational<br />

programs that train for peace.<br />

RIO DE JANEIRO: VIOLENCE, BEAUTY,<br />

INEQUALITY<br />

The paradox of Rio is that it is at once one of the<br />

most violent and one of the most naturally beautiful<br />

cities in the world. Nurturing the violence is<br />

a poverty that thrives, jarringly, alongside Rio’s<br />

splendor. In fact, the problem is countrywide:<br />

Brazil displays one of the highest rates of social<br />

inequality in the world despite rapid economic<br />

development. The top 10 percent of the population<br />

earns 50 percent of the national income, and<br />

about 34 percent of the population lives below<br />

the poverty line. The government estimates that<br />

20 percent of the population lives in favelas,<br />

though the real figure could be even higher.<br />

Not surprisingly, the history of the favelas is<br />

deeply rooted in Brazil’s history of inequality,<br />

which has had both socioeconomic and racial<br />

overtones for centuries. In the world of the favelas,<br />

people struggle daily to defend themselves,<br />

either from drug traffickers or from the violence<br />

and the unpredictability of police agents who,<br />

16 <strong>SIPA</strong> NEWS<br />

according to groups like Human Rights Watch,<br />

often violate their human rights.<br />

This complex situation has led to an extremely<br />

troubling situation for Rio and its youth. A recent<br />

study published by British anthropologist Luke<br />

Dowdney confirms that more young people below<br />

the age of 18 are killed by guns each year in Rio<br />

than in many areas of the world that are officially<br />

at war. The study showed that there are strong<br />

similarities between children involved in drug<br />

wars in Rio’s favelas and child soldiers in other<br />

parts of the world. Drug gangs run the favelas,<br />

and Dowdney’s report describes how they employ<br />

youths as guards.<br />

The result is a war zone. In the period between<br />

1988 and 2002, almost 4,000 youths under<br />

18 years of age were killed by firearms in Rio.<br />

Currently, there are between 5,000 and 6,000<br />

armed children in Rio alone.<br />

THE FIGHT FOR PEACE<br />

So what can be done in order to reduce youth<br />

violence in cities like Rio where social inequalities<br />

and exclusion are so powerful?<br />

The answer can be found in “peace education,”<br />

according to Viva Rio, one of Brazil’s most<br />

renowned NGOs in the field of youth violence in<br />

favelas. Other NGOs are increasingly sharing the<br />

same perspective.<br />

“The introduction of a different perspective<br />

through peace education, conflict mediation and<br />

other tools can make a difference in contexts<br />

where youth violence is reaching immense proportions,”<br />

says Clarissa Huguet, a program coordinator<br />

with the Children and Youth in Organized<br />

Armed Violence (COAV) project at the Rio-based<br />

NGO. According to Huguet, there is an immense<br />

need to promote peace and multicultural education<br />

in areas where violence is epidemic and<br />

traditional schools face difficulties in fulfilling<br />

their main tasks. Huguet believes the result of her<br />

organization’s peace education will be a peaceful<br />

and progressive generation of children that build a<br />

different environment in their communities.<br />

Dowdney, who formerly worked with Viva Rio,<br />

has started his own initiative in a similar vein. But<br />

his program, Fight for Peace (FFP), takes things a<br />

step further, combining education programs with<br />

marketing tools to promote lifestyle changes for<br />

the youth of the slums. FFP works to include atrisk<br />

youth in sports, education, job training, youth<br />

leadership and conflict resolution programs. The<br />

project also unites community-based grassroots<br />

projects with big-time corporate sponsors. Nike<br />

has donated soccer equipment, boxing gear and<br />

cash.<br />

With these resources, FFP has managed to<br />

borrow a concept—branding—from the world of<br />

marketing. The organization’s brand is peaceful<br />

living. Just like sports gear, this lifestyle brand<br />

has some heavy-hitting spokespeople. FFP recruits<br />

sports celebrities—among them Brazilian Formula<br />

One champ Emmerson Fittipaldi and boxing<br />

star Acelino “Popó” Freitas—to visit the favela