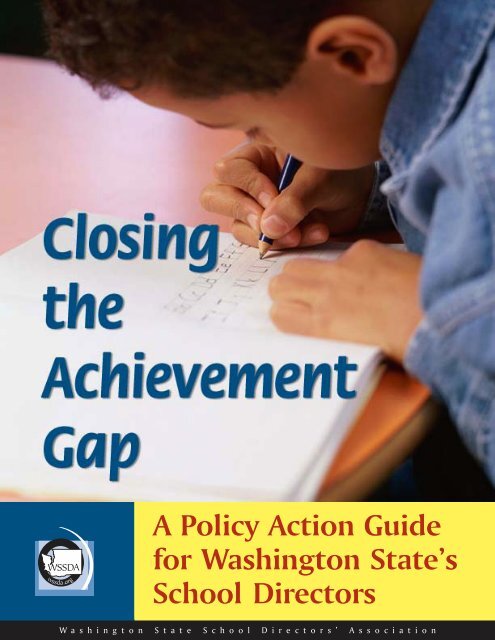

Closing the Achievement Gap - Washington State School Directors ...

Closing the Achievement Gap - Washington State School Directors ...

Closing the Achievement Gap - Washington State School Directors ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Table of ContentsForeword ........................................................................................................... vIntroduction ..................................................................................................... 1The Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task Force ........................................... 1Guiding Principles of <strong>the</strong> Task Force .................................................... 2Overview of <strong>the</strong> Policy Action Guide ............................................................ 5Understanding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>............................................................ 7Definition................................................................................................. 7Evidence of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> ........................................................ 8Understanding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> inEach <strong>School</strong> District ............................................................................. 11All Students Can Learn: Evidence That <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Can Be Closed ............. 13<strong>Closing</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>: Key Policy Issues....................................... 17Allocation and Alignment of Fiscal Resources ................................... 18Quality Teachers and Assignment ofQualified Staff to Low-Achieving Students........................................ 21Teaching and Learning.......................................................................... 24Cultural Competence ............................................................................ 27Time and Opportunity to Learn .......................................................... 30Learning Environment .......................................................................... 34Readiness <strong>Gap</strong> and Early Intervention ............................................... 36Parent Involvement and Community Collaboration ......................... 38Assessment and Accountability ........................................................... 41Conclusions .................................................................................................... 45O<strong>the</strong>r Policy Recommendations ................................................................... 49References ....................................................................................................... 53Presentations Made to <strong>the</strong> Task Force ......................................................... 57WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATIONiii

ForewordAll children can learn. If we teach <strong>the</strong>m at high levels, <strong>the</strong>ywill achieve at high levels. We have evidence that this is truein school after school all across <strong>the</strong> country.There is also ample evidence that what we, as school board members,believe about children’s abilities makes all <strong>the</strong> difference. If we believe thatall children can learn, we will design our school systems to make this possible.We have recognized that children don’t come to our school doors in cookiecutter fashion. They reflect <strong>the</strong>ir homes, communities and cultures. Ourschools need to address <strong>the</strong> uniqueness of each child, celebrating <strong>the</strong>irbackgrounds, gifts and contributions, while providing <strong>the</strong> individualizedinstruction, time and attention each needs to be successful.We have learned that equity does not mean equal in measuring resources.Need should be <strong>the</strong> measure of our allocations. <strong>School</strong> board membersmust ask ourselves if we have aligned our resources so that all children,regardless of <strong>the</strong> learning assets and deficits <strong>the</strong>y bring with <strong>the</strong>m, have aneven chance to meet our standards.All of this requires courageous decision-making on <strong>the</strong> part of schoolboards. While reducing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap that exists among ethnic andincome groups was always a moral obligation, it is now <strong>the</strong> law, too. TheNo Child Left Behind legislation passed by Congress in 2001 holds alldistricts receiving federal dollars accountable for <strong>the</strong> achievement of studentsin each ethnic group, for children living in poverty, for English languagelearners and for children needing special education assistance.This guide presents some of <strong>the</strong> best thinking about <strong>the</strong> difficult and puzzlingwork of improving student achievement. Taken as whole, it gives acomplete picture of what it will take to close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATIONv

My thanks to <strong>the</strong> members of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task Force for <strong>the</strong>irdiligence and thoughtfulness and passion for <strong>the</strong> success of all students.Thanks are also due to <strong>the</strong> WSSDA Board of <strong>Directors</strong> for forming andsupporting <strong>the</strong> Task Force, to <strong>the</strong> WSSDA Diversity-Multicultural AdvocacyTeam (D-MAT) for its advocacy of this project, to <strong>the</strong> WSSDA staffwho supported <strong>the</strong> Task Force, and to Debora Boeck, our skilled consultant.Best wishes to you all in this challenging and critically important workahead of us.CONNIE FLETCHERPresident, <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Directors</strong>’ AssociationChair, WSSDA Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task ForceviCLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

IntroductionEducators in <strong>Washington</strong> state have made significant advancesin improving education for all children. Establishing highstandards and being accountable through performance assessments arecritical beginnings in realizing a vision of world-class education. The goalis, and continues to be, for all children to meet or exceed <strong>the</strong> state’s highacademic standards.As documented in numerous state reports and national studies, not allchildren are reaching higher levels of achievement at <strong>the</strong> same rate. Indistricts across <strong>Washington</strong>, large groups of students are not meeting standards,creating a gap in achievement that is evident by group. Poverty andrace are substantial reasons for this gap.Establishing <strong>the</strong> Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task Force and issuing thisreport mark <strong>the</strong> first steps in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Directors</strong>’Association (WSSDA’s) efforts to close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. Local schoolboard directors must take <strong>the</strong> next steps, through governance and policy, toclose <strong>the</strong> gap so that all children, regardless of race, family income or familybackground, can excel academically. The work of <strong>the</strong> Task Force and thisreport reflect WSSDA’s commitment to work collaboratively with o<strong>the</strong>rorganizations in a concerted and coordinated effort to end <strong>the</strong> disparities inachievement between groups of children.It is <strong>the</strong> paramount duty of<strong>the</strong> state to make ampleprovision for <strong>the</strong> educationof all children residingwithin its borders, withoutdistinction or preference onaccount of race, color, casteor sex.— Article IX, Section 1<strong>Washington</strong> <strong>State</strong>ConstitutionThe Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task ForceThe Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> Task Force was established in January 2001.The Task Force is comprised of <strong>Washington</strong> school board members directedto make recommendations to <strong>the</strong> WSSDA Board of <strong>Directors</strong>, and ultimatelyto all school boards in <strong>Washington</strong>, on <strong>the</strong> actions that would bestassist school boards in closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. The Task Force wascharged to accomplish <strong>the</strong> following:WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION1

Assess <strong>the</strong> achievement gap problem.Identify research, initiatives and o<strong>the</strong>r actions being taken by a varietyof agencies and institutions addressing this issue.Based on research, catalog school board policies, initiatives and actionsthat have contributed to ongoing success in reducing or eliminating<strong>the</strong> performance disparity among minorities or children inpoverty.Drawing on <strong>the</strong> Task Force members’ talents and abilities, and suchexternal resources as may be available, develop and report on bestpractices, model policies, or o<strong>the</strong>r school board actions that WSSDAand its members can implement to address <strong>the</strong> achievement gap issue.Over <strong>the</strong> course of 22 months, <strong>the</strong> Task Force listened to numerous presentationsfrom experts in <strong>the</strong> field and from school districts addressing equityand excellence. Task Force members reviewed research reports and articleson <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. These presentations and readings were followed byextensive discussion of policy issues and <strong>the</strong> development of recommendations,all of which are reflected in this report.The goal of <strong>the</strong> Task Force is to arm school board directors with <strong>the</strong> knowledge,understanding and tools to improve student learning for all childrenand close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. In response to this goal, <strong>the</strong> Task Forcedeveloped <strong>the</strong> following guiding principles to serve as a foundation for itsissue analyses and recommendations.Guiding Principles of <strong>the</strong> Task ForceInequities persist in our society and in education, and school boards mustaccept a leadership role in mitigating <strong>the</strong>se inequities and closing <strong>the</strong>achievement gap that exists at all grade levels and in school districts of allsizes and locations in <strong>Washington</strong> state.<strong>Closing</strong> <strong>the</strong> achievement gap is critical to preserving American democracyand providing all students with <strong>the</strong> skills for economic self-sufficiency andopportunities to realize <strong>the</strong>ir potential.District policies should improve student learning and ensure that allstudents meet <strong>the</strong> essential academic learning requirements.Understanding <strong>the</strong> impact of race and poverty on student learning isessential to closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.<strong>School</strong>s cannot close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap alone. The responsibility isshared with schools, parents and larger community.All students can meet high standards when necessary opportunities,resources and support systems are provided.2CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

All schools can close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.The achievement gap can be significantly diminished or eradicated withoutlowering academic standards for any student.Students who have not achieved academic standards must have <strong>the</strong>iracademic progress accelerated to close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION3

Overview of <strong>the</strong> PolicyAction GuideThe <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>State</strong> <strong>School</strong> <strong>Directors</strong>’ Association (WSSDA)is publishing this report from <strong>the</strong> Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>Task Force to bring attention and focus to creating equity and excellence inall schools and classrooms. The report is designed to provide a frameworkfor school board and community dialogue about <strong>the</strong> achievement gap andto assist school boards across <strong>Washington</strong> in taking action to reduce, andultimately eliminate, <strong>the</strong> disparity in achievement among groups of students.This policy action guide begins by providing a definition and overview of<strong>the</strong> achievement gap, giving readers an understanding of what <strong>the</strong> gap is,why it exists and how it is stubbornly chronic in too many schools. Researchis also presented that school boards can use to understand <strong>the</strong>achievement gap and <strong>the</strong> impact of poverty and race on student learning.The intent is that this information helps school board members betterunderstand <strong>the</strong> achievement gap in <strong>the</strong>ir own districts. Research about <strong>the</strong>achievement of students in <strong>Washington</strong> state and nationally is provided tofur<strong>the</strong>r knowledge about <strong>the</strong> gap. Also presented is research that “dispels<strong>the</strong> myth” and gives evidence that poor students and minority students canachieve at high levels when <strong>the</strong>y are taught at high levels.The next section of <strong>the</strong> policy action guide presents what <strong>the</strong> Task Forcehas identified as key policy issues school boards need to address in closing<strong>the</strong> achievement gap. For each policy issue, context and background ispresented, followed by recommendations for action by local school boards.<strong>School</strong> districts throughout <strong>Washington</strong> are actively working to improvestudent achievement and close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap, and examples are citedfor each of <strong>the</strong> policy areas. Finally, general conclusions and policy-levelWASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION5

considerations are offered to o<strong>the</strong>r policy makers interested in addressing<strong>the</strong> achievement gap.<strong>School</strong> boards should use this guide as a foundation in developing anaction plan specific to <strong>the</strong>ir school district and community for closing <strong>the</strong>achievement gap.6CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

Understanding <strong>the</strong><strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>WSSDA’s overriding commitment is to all students meetingstate standards. To close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap, extra attentionmust be given to those students who, because of poverty or ethnicminority status, are not meeting <strong>the</strong> academic standards. This does notdiminish <strong>the</strong> dedication to achieving educational excellence for all students.Programs and strategies that close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap will help all studentslearn at higher levels.DefinitionFor <strong>the</strong> purposes of this report, <strong>the</strong> achievement gap is defined as:The difference in academic achievement between AfricanAmerican, American Indian and Hispanic students and<strong>the</strong>ir white and Asian peers and <strong>the</strong> difference in academicachievement between students, whose families areof low-income, and <strong>the</strong>ir peers from middle and upperincome families. The academic achievement gap is fur<strong>the</strong>rdefined in terms of performance on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Washington</strong>Assessment of Student Learning (WASL) and <strong>the</strong> IowaTest of Basic Skills (ITBS)/Iowa Test of EducationalDevelopment (ITED).This guide does refer, however, to <strong>the</strong> achievement gap on a national leveland <strong>the</strong>refore extends <strong>the</strong> definition to include differences in academicperformance as measured by o<strong>the</strong>r standardized tests. It is also importantto note that <strong>the</strong> Task Force recognized <strong>the</strong> limitations of this definition anduse of ethnic classifications that lump subgroups into one broad group.While, for example, not all Asian groups perform at <strong>the</strong> same achievementlevel, current data has not made it possible to fur<strong>the</strong>r disaggregate data byethnic subgroups.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION7

The Task Force also recognizes that o<strong>the</strong>r factors have significant effects onstudent learning that contribute to <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. One of <strong>the</strong> mostsignificant factors is language. Evidence exists to show that schools withhigher percentages of English language learners (ELL) have lower achievementrates, just as schools with higher percentages of students qualifyingfor free or reduced-price lunch have lower achievement rates. Districtsthroughout <strong>Washington</strong> are working to increase <strong>the</strong> achievement of Englishlanguage learners, and this guide addresses <strong>the</strong> need to improve thoseefforts as part of <strong>the</strong> gap closing strategy.Evidence of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>“The differential achievement of poor and ethnically diverse students iswell documented and spans all grade levels.” (Poverty and Race ResearchAction Council, 2001). The achievement gap exists in school districts andschools across <strong>Washington</strong> and <strong>the</strong> nation and is not restricted to onlythose districts or schools with high percentages of students of color orstudents from low-income families. The data in this section serve to highlightwhat many already know—achievement gaps have existed for a longtime and show no sign of disappearing.According to <strong>the</strong> National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), <strong>the</strong>test scores for <strong>the</strong> nation’s highest performing students have risen by threescale points since 1992, while <strong>the</strong> test scores of <strong>the</strong> nation’s lowest performingstudents have declined by seven scale points, causing <strong>the</strong> achievementgap to widen. According to <strong>the</strong> 2000 NAEP data, overall scores inreading and math increased; however, <strong>the</strong> differences between black andwhite students have increased in every subject area and every agegroup. The data also shows that <strong>the</strong> gap in test scores between whiteand black students persisted even when socio-economic status, levelof parent education and o<strong>the</strong>r factors were controlled.In <strong>Washington</strong>, <strong>the</strong> gap between whites and Asians and o<strong>the</strong>r ethnic groupsexists in most subjects and grades. According to <strong>the</strong> Office of Superintendentof Public Instruction (OSPI) data as presented to <strong>the</strong> Ad Hoc <strong>Achievement</strong><strong>Gap</strong> Task Force by Peter Bylsma, Director of Research and Evaluation:White students have higher performance levels than all minoritygroups except for Asians in 7th grade ma<strong>the</strong>matics.The performance of Asian students is fairly close to whites.Black, Hispanic and American Indian students have made lessprogress than whites or Asians.Whites and Asians have had about <strong>the</strong> same level of reduction in <strong>the</strong>percent of students not meeting standards.Black, Hispanic and American Indian students have made lessprogress in reducing <strong>the</strong> percent of students not meeting standards.8CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

Data also show a clear pattern of achievement based on socio-economicstatus. For example:<strong>School</strong>s with higher levels of students from poor families have lowerscores and have shown less improvement.Clear patterns of achievement exist according to socio-economicstatus, regardless of subject matter or type of test.A stronger relationship exists between socio-economic status and mathand seventh grade achievement than between socio-economic statusand reading and fourth grade achievement.In <strong>the</strong> following table and graph, <strong>the</strong> relationship of socio-economic statusand achievement for <strong>the</strong> elementary grades is presented. The table andgraph clearly show that <strong>the</strong> higher <strong>the</strong> percentage of students qualifying forfree or reduced-price lunch in a school, <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>the</strong> overall achievementof <strong>the</strong> student population.Pattern of <strong>Achievement</strong> on ITBS and WASL TestsRelated to Families' Socio-Economic StatusLess than10–19.9%20–29.9%30–39.9%40–49.9%50–59.9%60% +10% F & RF & RF & RF & RF & RF & RF & RITBS Math2-year Avg.ITBS Math2000ITBS Reading2-year Avg.ITBS Reading2000WASL Math3-year Avg.WASL Math2000WASL Reading3-Year Avg.WASL Reading2000Avg. %Low Income76.669.5 64.1 61.9 57.9 54.5 43. 978.170.7 65.6 63.1 59.7 56.4 44. 669.263.4 59.0 55.8 52.1 48.6 37. 369.863.5 59.7 56.4 53.1 49.8 37. 758.046.7 39.3 37.0 32.0 26.8 20. 262.953.3 45.5 42.3 36.1 32.4 23. 879.370.3 64.8 61.3 56.6 51.3 40. 482.876.3 70.5 67.7 62.6 57.5 46. 65 .6% 15.3%25.3%34.5%44.6%54.9%74.5%WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION9

Pattern of <strong>Achievement</strong> on ITBS and WASL TestsRelated to Families’ Socio-Economic Status60% or more F & R“While our state’s WASLscores are rising across allgeographical communities,all ethnic groups and allincome levels, <strong>the</strong>re remainsan achievement gap.Students of color and thoseliving in poverty generallymeet our new standards ata lower rate than do o<strong>the</strong>rstudents. Similar resultsare observed in o<strong>the</strong>rstudent assessments, aswell. This is unacceptable.”— Bill WilliamsWSSDA Past President50 – 59.9 F & R40 – 49.9% F & R30 – 39.9% F & R20 - 29.9% F & R10 - 19.9% F & RLess than 10% F & R0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90ITBS Math 2 year Avg. ITBS Math 2000 ITBS Reading 2 year Avg.ITBS Reading 2000 WASL Math 3 year Avg. WASL Math 2000WASL Reading 3 Year Avg. WASL Reading 2000 Avg. % Low IncomeThe achievement gap is present in schools and districts throughout <strong>Washington</strong>.In its report to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>State</strong> Legislature, <strong>the</strong> Academic<strong>Achievement</strong> and Accountability Commission (<strong>the</strong> A+ Commission) reportedthat students of color, excluding Asian/Pacific Islander students,tended to be in schools that did not meet <strong>the</strong>ir fourth grade reading goalsmore often than in schools that did.The A+ Commission also found that, unlike special education and highlycapable students who are evenly distributed between schools that met <strong>the</strong>irfourth grade reading goals and those that did not, limited English profi10CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

cient (LEP) students were disproportionately represented in schools thathad not met <strong>the</strong>ir reading goals.The data are similar for different socio-economic groups. The A+ Commissionfound schools that met <strong>the</strong>ir fourth grade reading goals had lowerpercentages of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch. In fact, <strong>the</strong>percentage of schools meeting <strong>the</strong>ir goals decreases as <strong>the</strong> percentage ofstudents receiving free or reduced-price lunches increases.Understanding <strong>the</strong> <strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> in Each <strong>School</strong> DistrictTo provide leadership and policy guidance at <strong>the</strong> local level, school boardsneed to have a thorough understanding of <strong>the</strong> achievement gap in <strong>the</strong>irown school district. This means having a working knowledge of <strong>the</strong>district’s assessment results from <strong>the</strong> ITBS/ITED and WASL and knowing<strong>the</strong> right questions to ask regarding <strong>the</strong> test scores to determine <strong>the</strong> degreeto which some students are achieving and o<strong>the</strong>rs are not.With knowledge and understanding of what <strong>the</strong> achievement gap looks likein <strong>the</strong>ir schools, board members can engage staff and <strong>the</strong> community inmeaningful dialogue about why a gap exists and specific actions to take toclose <strong>the</strong> gap.The following questions can help guide <strong>the</strong> discussion about studentachievement to determine <strong>the</strong> extent to which <strong>the</strong> achievement gap existsin each school district.1. Based on <strong>the</strong> scores from <strong>the</strong> ITBS/ITED and WASL, what are <strong>the</strong>achievement rates for all students in <strong>the</strong> district at each grade leveltested? What has been <strong>the</strong> three-year trend of <strong>the</strong>se test scores?2. To what degree is <strong>the</strong>re a difference in <strong>the</strong> test scores of studentsacross socio-economic groups? To what degree is <strong>the</strong>re a difference in<strong>the</strong> test scores of students across ethnic groups?3. Do <strong>the</strong> scores over <strong>the</strong> past three years show any trend? Is <strong>the</strong> differencein <strong>the</strong> test scores across groups increasing or decreasing?4. What o<strong>the</strong>r patterns or trends exist in <strong>the</strong> achievement rates of ethnicminority and low-income students?5. Are <strong>the</strong>re patterns of achievement between groups across schools?What are <strong>the</strong> characteristics of schools with lower achievement? Whatdoes <strong>the</strong> Just For Kids data 1 show?6. What conclusions about student achievement can be drawn from <strong>the</strong>data, and what limitations are <strong>the</strong>re?1The <strong>Washington</strong> Just for <strong>the</strong> Kids is a Web-based data analysis and school performance and accountabilitysystem based on a very successful and highly acclaimed methodology developed by <strong>the</strong> Just for <strong>the</strong>Kids organization in Austin, Texas. The methodology takes into account a school’s socio-economicstatus, bilingual services, size, student mobility rate and o<strong>the</strong>r factors to identify high performingschools based on WASL and ITBS/ITED data. The Web site is www.spu.edu/orgs/research/justkids.asp.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION11

7. What o<strong>the</strong>r assessment data exist at <strong>the</strong> school and classroom levelsto demonstrate student achievement trends in <strong>the</strong> district?The achievement gap plays out in a myriad of ways in addition to testscores. While investigating <strong>the</strong> gap in districts, it is important to consider<strong>the</strong> following:Dropout and College Rates. The report Postsecondary Opportunity and<strong>Achievement</strong> in <strong>Washington</strong> presents research showing that AfricanAmerican, Hispanic and Native American students in <strong>Washington</strong> aremore likely to drop out of high school and less likely to go directly toa four-year college from high school. According to <strong>the</strong> report, about 17percent of high school students drop out; however <strong>the</strong> rate for black,Native American and Hispanic students is between 27 percent and 36percent.Over-representation in Special Education. The A+ Commissionreported that American Indian and black students are over-representedin special education compared to <strong>the</strong>ir presence in <strong>the</strong> nonspecialeducation population. Data show that while four percent ofAmerican Indians are in special education, <strong>the</strong>y make up only 2.5percent of <strong>the</strong> non-special education population. Blacks make up 8.1percent of <strong>the</strong> special education population and only 5.5 percent of<strong>the</strong> non-special education population. Whites and Hispanics are eachequally represented in <strong>the</strong> special education and general educationpopulations, and Asians are under-represented.Under-representation in Gifted/Talented Programs and AdvancedPlacement Classes. Low expectations for students of color and thosewho are poor have a significant impact on achievement. Low expectationsfor students may be one reason that students of color and thosefrom poverty are under-represented in Advanced Placement (AP)classes and gifted and talented programs. In <strong>Washington</strong>, for example,only 661 American Indian, black and Hispanic students out of 11,447were enrolled in AP classes in 2001. Research shows that studentswith opportunities to learn at high levels have a much higher probabilityof completing a college degree.Discipline. Uneven administration of discipline results in students ofcolor being suspended and expelled more often than o<strong>the</strong>r students.Studies have shown this disparity in discipline based on race cannotbe explained just on socio-economic factors or <strong>the</strong> home lives ofchildren. A greater understanding of students from different culturesis needed by teachers and principals in applying fair and consistentdiscipline practices. As reported in <strong>the</strong> Seattle Post-Intelligencer, a SanFrancisco school has implemented a successful program to reduce <strong>the</strong>discipline gap by focusing on what adults can do to manage studentbehavior, ra<strong>the</strong>r than what students can do.12CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

All Students Can Learn:Evidence That <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gap</strong> CanBe ClosedResearch has shown that schools, including those with highpercentages of children from poverty, those with high racialminority enrollments, and those with high percentages of English languagelearners are successfully closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. In 2002, <strong>the</strong> EducationTrust (www.edtrust.org) based in <strong>Washington</strong>, D.C. released <strong>the</strong> resultsof a comprehensive study of school-level test scores in 47 states and <strong>the</strong>District of Columbia from <strong>the</strong> year 2000. The report identified schools ineach state with math and/or reading achievement levels in <strong>the</strong> top one-thirdof all schools that also ranked in <strong>the</strong> top one-third of <strong>the</strong> state for povertylevels and/or African American and Latino enrollments. The study identified:3,592 high-performing, high-poverty schools2,305 high-performing, high-minority schools1,320 high-performing, high-poverty and high-minority schoolsNearly 50 percent of <strong>the</strong> schools identified above scored in <strong>the</strong> top onethirdin <strong>the</strong>ir states in both math and reading or language arts.In <strong>Washington</strong>, schools have made significant gains in <strong>the</strong> achievement of<strong>the</strong>ir students as measured by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Washington</strong> Assessment of StudentLearning. In 2000, <strong>the</strong> Partnership for Learning sponsored a University of<strong>Washington</strong> study that looked at schools that had been performing wellbelow state averages. Based on a comparison of <strong>the</strong>ir past and currentperformance, a number of schools with high percentages of students eligiblefor free or reduced-price lunch made significant gains on <strong>the</strong> WASL readingand math tests. A total of 33 elementary schools and 32 middle schoolswere included in <strong>the</strong> study and had, despite <strong>the</strong>ir demographics, madesignificant gains to surpass state averages.Dispelling <strong>the</strong> MythRevisited, <strong>the</strong> report issuedby The Education Trust,“provides persuasiveevidence that poor andminority children canachieve at high levels when<strong>the</strong>y are taught at highlevels.”— Kati Haycock, DirectorThe Education TrustWASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION13

The <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>School</strong> Research Center’s Bridging <strong>the</strong> Opportunity <strong>Gap</strong>report of March 2002 identified 16 schools that demonstrated higherstudent achievement as measured by fourth grade WASL scores thanschools with similar demographics. Among <strong>the</strong> sixteen schools in <strong>the</strong> study,eight had 50 percent or more of <strong>the</strong>ir students qualifying for free or reduced-pricelunch and <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r eight had 25-49 percent of <strong>the</strong>ir studentsqualifying for free or reduced-price lunch. These schools had as many as89 percent of <strong>the</strong>ir students meeting reading, writing and ma<strong>the</strong>maticsstandards.Whitney Elementary, in <strong>the</strong> Yakima <strong>School</strong> District (www.ysd.wednet.edu),for example, has 73 percent of its students on free or reduced-price lunch.In 1999, only 26 percent of <strong>the</strong> fourth grade students met standard on <strong>the</strong>WASL reading, math and writing. In 2000 that increased to 42 percent,and in 2001, 63 percent of <strong>the</strong> fourth graders met standard in <strong>the</strong>se threeareas.100%90%80%70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%Larrabee Elementary in <strong>the</strong> Bellingham <strong>School</strong> District(www.bham.wednet.edu) is ano<strong>the</strong>r example. With 31 percent free orreduced-price lunch, <strong>the</strong>y were able to increase <strong>the</strong> percent of fourth gradersmeeting math, reading and writing standards from 56 percent in 1999to 81 percent in 2001. The average in 2001 for schools with 25-49 percentfree or reduced-price lunch was 51 percent of <strong>the</strong> students meeting <strong>the</strong>sestandards.14CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

The two building graphs are from <strong>Washington</strong> <strong>School</strong> ResearchCenter, Bridging <strong>the</strong> Opportunity <strong>Gap</strong> report, 2002.Researchers interviewed teachers, principals, school leaders and a districtrepresentative in each of <strong>the</strong> highly successful schools. Based on <strong>the</strong> interviews,<strong>the</strong> following four factors were essential to <strong>the</strong>se effective schools:A caring and collaborative professional environmentStrong leadershipFocused and intentional instructionUse of assessment to inform instructionO<strong>the</strong>r factors identified by <strong>the</strong> educators as important but not necessarilypresent in every school were:Small school sizeDistrict supportLack of student and staff mobilityParent and community involvementProfessional developmentBridging <strong>the</strong> Opportunity <strong>Gap</strong> can be found at www.spu.edu/wsrc.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION15

<strong>Closing</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Achievement</strong> <strong>Gap</strong>:Key Policy IssuesThe goal is to close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. Economic status, raceand culture should not be predictors of academic achievement.To close <strong>the</strong> gap, school districts must direct resources to those with <strong>the</strong>greatest need and implement strategies to accelerate <strong>the</strong> learning of studentswho are underachieving. <strong>Closing</strong> <strong>the</strong> gap requires finding ways toclose <strong>the</strong> readiness gap so that no children enter kindergarten significantlybehind <strong>the</strong>ir peers. Serious attention must be given to creating learningenvironments that are intolerant of racism and exclusion and in which highexpectations are held for all students. All students, especially low-achievingand disadvantaged students, must be taught by highly qualified staff inpersonalized learning environments. Curriculum and teaching practicesmust recognize differences in ethnicity, language and culture and teachersmust be skilled in teaching students unlike <strong>the</strong>mselves. An emphasis mustbe placed on literacy and ma<strong>the</strong>matics. And, finally, reaching out to andempowering parents will be essential—schools cannot close <strong>the</strong>se gapsalone.The role of <strong>the</strong> school board is to work at <strong>the</strong> governance level to create <strong>the</strong>structure and policies for <strong>the</strong>se reforms to occur systemically. In <strong>the</strong> followingsection, <strong>the</strong> key policy issues, guidelines for discussing <strong>the</strong>se issues at<strong>the</strong> local board level, and recommendations for policy implementation arepresented. Examples of what some school districts are doing to address eachpolicy area are also presented.The Task Force did not prioritize <strong>the</strong>se policy issues. Each of <strong>the</strong> policyissues must be addressed to implement a comprehensive gap closing strategy.<strong>School</strong> boards are encouraged to review <strong>the</strong>ir current policies andpractices to determine which of <strong>the</strong>se policy issues should be prioritieswithin <strong>the</strong>ir own district.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION17

Allocation and Alignment of Fiscal ResourcesIn <strong>Washington</strong> state, school districts are expected, for <strong>the</strong> mostpart, to improve student learning with existing resources. Given thisreality, districts must make new, critical choices about <strong>the</strong> use of<strong>the</strong>ir resources and target those limited dollars where <strong>the</strong>y will have <strong>the</strong>greatest impact.According to Odden and Archibald (2001), several commonalities exist in<strong>the</strong> resource allocation practices of schools engaged in successful reform.These commonalities include:<strong>School</strong>s allocate resources to where <strong>the</strong>y are most needed and have <strong>the</strong>greatest impact on student achievement.<strong>School</strong>s dramatically reduce or eliminate classroom pull-out strategiesand implement o<strong>the</strong>r practices, such as one-to-one tutoring throughextended day programs and instruction in small classes.Strategies implemented for low-achieving students, struggling studentsfrom low-income families, English language learners and those withmild learning disabilities are very similar and are delivered withpooled funds.An increasing number of districts eliminate or greatly reduce instructionalaide positions and use resources to implement o<strong>the</strong>r teacherprovidedinstructional strategies to accelerate <strong>the</strong> achievement ofstruggling students.Additional resources can also have a significant impact on student achievementwhen properly targeted. According to an NAEP study, resources mustbe allocated to specific programs, schools and/or grade levels and towardspecific students to be most effective (Improving Student <strong>Achievement</strong>: What<strong>State</strong> NAEP Test Scores Tell Us, 2000). Targeted class size reductions (forexample, smaller class sizes only for schools with a high percentage ofstudents eligible for free or reduced-price lunch or smaller class sizes onlyat primary grades) are policies for boards to consider.Equal does not necessarily mean equitable. Resources must be directedbased on need. Weighted student formulas acknowledge thatresources cannot be equally distributed if <strong>the</strong> needs of all students are to bemet. Many districts allocate resources to schools in such a way that morefunding per student goes to those schools with students with above averageneeds. For example, in Seattle Public <strong>School</strong>s (www.seattleschools.org),about 60 percent of <strong>the</strong> district’s state and local funding is allocated toschools on a weighted student formula, sending more money per studentfor special education, English language learners or students eligible for freeor reduced-price meals. Weighted student formulas can be used to addressdisproportional needs.18CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

Questions to Guide <strong>the</strong> Policy Discussion1. To what degree are existing resources used to achieve <strong>the</strong> greatestimpact on student achievement? Are existing resources used to supportresearch-based, best practices for closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap?2. How are resources allocated to different schools within <strong>the</strong> district?Do <strong>the</strong> schools with <strong>the</strong> most disadvantaged students have <strong>the</strong> level ofresources <strong>the</strong>y need to help close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap?3. What board policies currently exist that perpetuate resource inequities?What board policies currently exist that create barriers to directingresources to students with <strong>the</strong> greatest need?4. What are innovative models that o<strong>the</strong>r districts are using for aligningresources with <strong>the</strong> greatest needs?5. How can <strong>the</strong> school district’s allocation decisions be better aligned toimprove student learning and close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap?Policy Recommendations1. Create a district and community culture that reinforces <strong>the</strong> commitmentand belief that all district staff and <strong>the</strong> community members are responsibleto, and accountable for, <strong>the</strong> education of all students at every schoolin <strong>the</strong> district. From this philosophical foundation, work with staff and<strong>the</strong> community in evaluating <strong>the</strong> use of existing resources and <strong>the</strong> degreeto which resources are meeting <strong>the</strong> needs of students who must have<strong>the</strong>ir achievement accelerated to close <strong>the</strong> gap.2. Complete an evaluation of current policies and programs intended toaddress needs of underachieving students and determine whe<strong>the</strong>r currentresources are producing <strong>the</strong> desired benefits. Develop resource realignmentpolicies that support programs based on valid research and results,and implement program evaluation methods and timelines for reportingback to <strong>the</strong> board on program effectiveness.3. Investigate successful weighted student formulas used by o<strong>the</strong>r districtsand determine <strong>the</strong>ir appropriateness in helping <strong>the</strong> district meet its gapclosing goals.4. Base resource allocation decisions on a well thought out strategic plan forclosing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap, and target resources to meet <strong>the</strong> specificgap closing goals of <strong>the</strong> plan.5. Review and evaluate <strong>the</strong> use of new funding sources, such as I-728 andTitle I funding in terms of <strong>the</strong> alignment of <strong>the</strong>se resources with <strong>the</strong>greatest needs. Consider allocation decisions o<strong>the</strong>r than per-student todirect and concentrate <strong>the</strong>se resources where <strong>the</strong>y will have <strong>the</strong> maximumimpact on reducing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION19

What <strong>School</strong> Districts Are DoingIn <strong>the</strong> Federal Way <strong>School</strong> District (www.fwsd.wednet.edu), staff has createda way to reliably identify schools that are struggling to meet state anddistrict goals for student achievement and are in need of extra support,assistance or intervention. Staff created a rubric, or scoring guide, thatplaces schools along a three-point continuum. <strong>School</strong>s are rated usingachievement targets from <strong>the</strong> district’s strategic plan, and a school’s ratingis used in allocating both fiscal and human resources. Strategic plan goalsused for evaluation are:<strong>School</strong> meets or exceeds goals for WASL reading.80 percent of <strong>the</strong> school’s third grade students are reading at gradelevel as measured by <strong>the</strong> ITBS.<strong>School</strong> demonstrates continuous increase in student performance asmeasured by a 3-year rolling average on <strong>the</strong> WASL and ITBS/ITED.<strong>School</strong> increases <strong>the</strong> number of students meeting standard on STARscores from fall to spring.<strong>School</strong> has an “opportunity gap” under ten percent of students achievingbelow <strong>the</strong> average of <strong>the</strong> top-ten comparable schools.For schools identified as “intervention schools,” increased staff is allocatedto focus on increasing skills and reducing student-teacher ratios in gradesK-2. In addition, an Instructional Team Member is allotted at least a fulldayeach week to <strong>the</strong> school to work with teachers, and <strong>the</strong> school mayalso receive additional funds depending on achievement needs.The Edmonds <strong>School</strong> District (www.edmonds.wednet.edu) has used aweighted student formula to allocate funding to schools for many years.The formula was first developed to provide a differentiated level of learningsupport to individual schools. The formula is used to allocate a portion of<strong>the</strong> resources to schools and includes funding for Title I, LAP and specialeducation as well as <strong>the</strong> basic education dollars generated by special educationstudents. Under <strong>the</strong> formula, all schools receive some level of support,but <strong>the</strong> level of support is determined by a needs assessment. Criteria for<strong>the</strong> elementary school needs assessment includes <strong>the</strong> following:Student enrollmentPercentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunchNumber of students scoring below <strong>the</strong> 25th percentile on districtdeveloped reading and math achievement testsPercentage of students not meeting standard in reading and math on4th grade WASLNumber of students with individual education plans (IEPs)Number of “ins and outs” to measure mobility20CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

Percentage of students who were enrolled at <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> yearand are still enrolled at <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> yearPercentage of limited English proficient students eligible for ESLPercentage of students living in non-two-parent familiesBased on <strong>the</strong>se criteria, schools are rank ordered using a formula to determinea composite score. The higher <strong>the</strong> actual score, <strong>the</strong> higher <strong>the</strong> need,and funds are allocated accordingly.Quality Teachers and Assignment of QualifiedStaff to Low-Achieving StudentsQuality teachers are paramount to closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.<strong>School</strong> boards must ensure that all students have access to <strong>the</strong> mostbasic learning resource – quality teaching. According to Haycock(1998), <strong>the</strong> most important educational investment a state can make is inhighly qualified teachers.Extensive research from <strong>the</strong> Value-Added Research and Assessment Centerat <strong>the</strong> University of Tennessee demonstrates that,Groups of students with comparable abilities and initial achievement levelsmay have vastly different academic outcomes as a result of <strong>the</strong> sequence ofteachers to which <strong>the</strong>y are assigned. Based on <strong>the</strong>se results, students benefitingfrom regular yearly assignment to more effective teachers (even by chance)have an extreme advantage in terms of attaining higher levels of achievement.(Sanders and Rivers, 1996, p.6.)The study also demonstrated that lower achieving students benefited <strong>the</strong>most, average students next, and above average students <strong>the</strong> least fromincreased teacher effectiveness. Effective teachers produced significantlyhigher gains in student achievement among low achieving students thandid less effective teachers. Similar results were found in research conductedin <strong>the</strong> Boston Public <strong>School</strong>s and in <strong>the</strong> Dallas <strong>School</strong> District.Placing highly qualified teachers with students who are underachievingwill have <strong>the</strong> greatest impact on closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap.Districts must consider how teachers are assigned. This includes how <strong>the</strong>yare assigned to schools in low-income neighborhoods versus moreadvantaged communities and how <strong>the</strong>y are assigned to classrooms andprograms that serve disadvantaged students versus those that serve achievingand highly achieving students.<strong>School</strong> boards and administrators can improve student achievementthrough <strong>the</strong> professional development of teachers. Improving teacher qualitymust be addressed in policies that provide for on-going professionaldevelopment. This includes teachers knowing how to use student academicperformance data to improve <strong>the</strong> teaching and learning.“In <strong>the</strong> hands of our bestteachers, <strong>the</strong> effects ofpoverty and institutionalracism melt away, allowing<strong>the</strong>se students to soar to <strong>the</strong>same heights as youngAmericans from moreadvantaged homes.”— Kati Haycock, DirectorThe Education Trust1998WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION21

The No Child Left Behind Act (www.nochildleftbehind.gov) requires thatall teachers in core academic subjects be highly qualified by <strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong>2005-6 school years. The new law defines highly qualified teachers as thosewho not only possess full state certification but also have a solid contentknowledge of <strong>the</strong> subjects <strong>the</strong>y teach. High quality teachers must employeffective instructional and assessment strategies and methods in preparingstudents to meet state standards. Teachers must be able to do this for all<strong>the</strong> children <strong>the</strong>y teach.In providing professional development, key areas including pedagogy,content knowledge of subjects taught, use of assessment data to driveinstructional decisions and understanding <strong>the</strong> needs of a diverse studentpopulation are paramount. An ongoing policy issue centers on providingteachers with sufficient time to develop <strong>the</strong>se critical skills and knowledge.The assignment of teachers and instructional aides is also a critical factorin closing <strong>the</strong> achievement gap. Project STAR in <strong>the</strong> state of Tennessee wasa large-scale, randomized within-school research study focused primarily ondetermining <strong>the</strong> effects of class size. Secondary analysis addressed <strong>the</strong> useof instructional aides and <strong>the</strong> benefits of using assistants to improve studentachievement. The results from STAR, as well as from o<strong>the</strong>r researchstudies, have found that, in general, instructional aides are not effective inimproving <strong>the</strong> academic performance of students. Project STAR found nosignificant difference in student achievement between students in classeswith instructional aides and full-size classes without assistants.Questions to Guide <strong>the</strong> Discussion1. Do schools with <strong>the</strong> most needy students have <strong>the</strong> least experiencedteachers? Are Title I/LAP and o<strong>the</strong>r programs for disadvantaged orstruggling students staffed primarily with instructional aides providinglearning support?2. What practices are in place to recruit and retain qualified teachers?What is <strong>the</strong> district’s teacher turnover rate, and how is this affecting<strong>the</strong> district’s ability to meet <strong>the</strong> needs of low-achieving students andto have <strong>the</strong>m served by <strong>the</strong> most qualified teachers?3. What types of professional development do teachers need to help<strong>the</strong>m be more culturally competent? For example, does professionaldevelopment give teachers and o<strong>the</strong>r staff members opportunities totalk and learn about race and culture and <strong>the</strong> perceptions and biases<strong>the</strong>y may have encountered growing up? Does professional developmentprovide opportunities for staff to talk and learn about how race,poverty and culture affect teaching and learning?4. Is professional development for implementing strategies to close <strong>the</strong>achievement gap on-going, supportive and effective? Do teachers feelempowered in planning and conducting <strong>the</strong>ir professional develop-22CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

ment? As a result of training, are new strategies really being implemented?5. Is <strong>the</strong>re collaboration with <strong>the</strong> teachers’ association to place <strong>the</strong> mostqualified teachers with students who need to accelerate <strong>the</strong>ir academicperformance and/or in schools with <strong>the</strong> highest percentage of childrenfrom low-income families or children of color?6. What is <strong>the</strong> district’s policy or practice for <strong>the</strong> use of instructionalaides? What evaluation data is <strong>the</strong>re that would inform decisionsabout <strong>the</strong> district’s use of instructional aides for improving studentachievement?Policy Recommendations1. Negotiate with <strong>the</strong> local teachers’ association on assignment and transferof teaching staff to maximize effective teaching where <strong>the</strong>re is most need.Make sure that schools have an equitable distribution of highly skilledteachers.2. Implement policies directing <strong>the</strong> superintendent to develop plans thatmove teachers to positions so <strong>the</strong>y are teaching in <strong>the</strong>ir areas of endorsementor areas of expertise. Assist teachers in acquiring endorsements andtraining for assignments where <strong>the</strong>y are needed.3. Develop recruitment programs that include specific and concerted effortsto attract and place highly qualified minority teachers.4. Investigate <strong>the</strong> district’s current use of instructional aides to provideadditional learning opportunities and/or remediation to struggling students.Give consideration to limiting or redirecting <strong>the</strong> role of aides inlight of <strong>the</strong> research. Students who are not achieving benefit most withinstruction from qualified teachers.5. Review professional development programs to ensure that <strong>the</strong>y addresscultural competence. Require multi-cultural education training for teachersand administrators.6. Create opportunities for teacher release time to be used for specifictraining in literacy and ma<strong>the</strong>matics and in <strong>the</strong> development of teachingskills in how to make learning effective, individual and long lasting.7. Develop policies and budget priorities for staff development that arealigned with <strong>the</strong> district’s student achievement goals and objectives.8. Develop policies and practices that support ongoing professional developmentfor all staff and especially mentoring and coaching for new andstruggling teachers.WASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION23

What <strong>School</strong> Districts Are DoingThe Tacoma Public <strong>School</strong>s (www.tacoma.k12.wa.us) operates “ProjectQuality,” a partnership between <strong>the</strong> school district and <strong>the</strong> Tacoma EducationAssociation to develop and support accomplished teaching standardsthat reflect high expectations for teaching and learning in every classroom.They also shape <strong>the</strong> district’s recruitment, mentoring, professional developmentand evaluation activities.This past year, <strong>the</strong> Mukilteo <strong>School</strong> District (www.mukilteo.wednet.edu)completed a comprehensive review of its learning support program thatrelied heavily on <strong>the</strong> use of instructional aides in <strong>the</strong> delivery of instructionalsupport to struggling students and English language learners (ELL).With an increasing number of students, including ELL students, studentsfrom low-income families and students with special needs, <strong>the</strong> program wasserving a greater percentage of students. In some schools, <strong>the</strong> percentage ofstudents served exceeded 30 percent of <strong>the</strong> school’s student population.Program changes that will be implemented based on <strong>the</strong> review included(1) increasing reliance on <strong>the</strong> use of certificated teachers in <strong>the</strong> delivery ofinstruction to students so that <strong>the</strong> most qualified staff are serving <strong>the</strong>students in <strong>the</strong> learning support program who are <strong>the</strong> lowest achieving; and(2) reducing <strong>the</strong> number of instructional aides in <strong>the</strong> learning supportprogram and ensuring that existing instructional aides implementing instructiondo so under <strong>the</strong> direction of a certificated teacher with clearguidelines that clarify <strong>the</strong> role and responsibilities of instructional aides,classroom teachers, and learning support program personnel.Teaching and LearningNew conceptions of teaching and learning exist in <strong>the</strong> current visionof schooling with its emphasis on high standards, principles ofequity, and accountability. Teachers must teach to standards, usecurriculum aligned to standards, provide clear and focused instruction, andassess student performance toward meeting standards.Teaching and learning must give all students <strong>the</strong> opportunity to learn athigh levels. Academic rigor plays a significant role. Rigorous academiccoursework can mitigate <strong>the</strong> influence of <strong>the</strong> family’s socio-economic statusin a student’s life. High expectations for all students means providingopportunities to interact with peers who share high academic goals. Accessto all programs without educational segregation are methods to ensureopportunities for all students to learn at high levels. NAEP results clearlyshow that tracking or educational segregation, for example, has a negativeimpact on achievement. Those students who take more vocational classeshave lower standardized test results than students who enroll in academicorientedclasses.The Spokane <strong>School</strong> District (www.spokaneschools.org) conducted seniorexit interviews this past year, and students in Advanced Placement and24CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

honors classes stated that <strong>the</strong>y felt prepared for <strong>the</strong>ir future, not because of<strong>the</strong> material covered but because of <strong>the</strong> “life lessons” of meeting deadlines,independent work and real-life applications used in learning, while moststudents in regular classes felt unprepared and asked for less busy work andmemorization and more application-based learning.Technology is <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r key factor in <strong>the</strong> current teaching and learningframework. Recent ITBS scores showed that sixth graders who had a homecomputer scored 26 percentile points higher than those students without.Those with access to <strong>the</strong> Internet and/or e-mail scored 23 percentile pointshigher. Providing access to technology and integrating technology across<strong>the</strong> curriculum must be part of <strong>the</strong> teaching and learning framework at allgrade levels.Connecting students to learning through <strong>the</strong>ir passions and strengths isalso critical to student achievement. Rigorous curriculum and academicfocus does not mean a limited academic focus. The arts have an importantrole to play in a rigorous curriculum, and many districts are successfullyintegrating <strong>the</strong> arts across <strong>the</strong> curriculum. “The arts make sense to studentsbecause <strong>the</strong> arts allow <strong>the</strong>m to connect with topics, issues, ideas on agreater level of understanding. The arts help students internalize andprocess <strong>the</strong>ir world.” (Cynthia Chesak, Tukwila <strong>School</strong> District.)Teaching English Language Learners. Instructional methods must alsotake into account students’ first language. <strong>Closing</strong> <strong>the</strong> gap for Englishlanguage learners (ELL) is a challenge faced by many districts. The researchon English language learning is clear about what works. According to <strong>the</strong>Center for Research on Education, Diversity and Excellence (CREDE), allstudents benefit from academic instruction conducted in <strong>the</strong>ir first language.Those English language learners who are taught in <strong>the</strong>ir first languageend up being more successful in English-based instruction whencompared to ELL who are not taught academically in <strong>the</strong>ir first language.CREDE also found that instruction for English language learners needs tobe provided for at least four years and up to seven years for ELL learners tobe at <strong>the</strong> same level as those students who are native English speakers.Eighty percent of school districts in <strong>Washington</strong> state use ESL (English-asa-second-language)pull-out for English language learners, but it is <strong>the</strong> leasteffective and most expensive program to implement. Pull-out programstend to shift <strong>the</strong> responsibility for student learning to instructional aidesand o<strong>the</strong>rs. The most effective programs (in order of effectiveness) are:Two-way bilingual, dual languageLate exit bilingual and content ESLEarly exit bilingual and content ESLEarly exit bilingual and traditional ESLESL through academic contentESL pull-outWASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION25

Questions to Guide <strong>the</strong> Discussion1. Has <strong>the</strong> district developed a teaching and learning framework forsupporting standards-based education? Is <strong>the</strong> curriculum aligned to<strong>the</strong> standards and do teachers use classroom-based assessments tosteer <strong>the</strong>ir instruction?2. Is <strong>the</strong> learning framework focused on providing all students withopportunities to learn at high levels? Is <strong>the</strong> curriculum based onchallenging content that requires application and demonstration oflearning?3. What policies and practices are in place that encourage and supportminority and low-income students’ access to, and success in, challengingcourses, such as Advanced Placement, honors or InternationalBaccalaureate classes?4. To what degree do teachers’ expectations for students in poverty,students of color or English language learners affect decisions aboutstudent placement or <strong>the</strong> tracking of students?5. What is <strong>the</strong> instructional program model for English language learners?To what degree is ESL pull-out used as a program option? Do <strong>the</strong>schools provide English language learners with sufficient support forlearning academic subjects?6. How is technology used across <strong>the</strong> curriculum? What is being done toincrease access to technology for all students?7. To what degree does <strong>the</strong> district use programs like <strong>the</strong> arts to engagestudents and provide <strong>the</strong>m vehicles for applying academic learning?Policy Recommendations1. Develop a board philosophy and set of principles guiding <strong>the</strong> implementationof standards-based instruction, curriculum aligned to standards and<strong>the</strong> use of best practices in classrooms.2. Review current curriculum development and adoption policies and reviseas needed to ensure that curriculum decisions are made to supportstandards and current trends in educational reform. Use equity checklistsor rubrics in <strong>the</strong> review of all curriculum.3. Implement policies that provide for a rigorous curriculum for all students.Ensure that all students have opportunities to enroll in honors, AdvancedPlacement and International Baccalaureate programs.4. Review <strong>the</strong> district’s program structure and staffing for English languagelearners to determine its alignment with best practices and implementneeded program changes with a focus on reducing ESL pull-out as <strong>the</strong>model for instruction.26CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

What Districts Are DoingBellevue <strong>School</strong> District (www.belnet.bellevue.k12.wa.us) is working toraise standards for all students and lower <strong>the</strong> dropout rate by using AdvancedPlacement (AP) as an anchor for <strong>the</strong> overall improvement of studentachievement. In six years, <strong>the</strong> district has gone from scattered APcourse offerings to a district where all high schools offer a full AP or InternationalBaccalaureate program and district curriculum development is tiedat all levels with AP curriculum and tests. More than 70 percent of <strong>the</strong>district’s current senior class has taken at least one Advanced Placementcourse.Technology can be a great equalizer for students. The Bridgeport <strong>School</strong>District (www.bridgeport.wednet.edu) is a model for using technology toreduce <strong>the</strong> differences among students. Bridgeport went from 80 percentwhite in <strong>the</strong> mid-nineties to 86 percent Hispanic and at <strong>the</strong> same timeexperienced enrollment and funding declines. The district addressed <strong>the</strong>sechanges by retooling its schools with technology. Bridgeport began bygetting donated computers to families and <strong>the</strong>n working with AmeriCorpsand Wilderness Technology to promote a “make it and take it” program inwhich students build a computer for <strong>the</strong>mselves and take it home. With afederal grant, <strong>the</strong> district is connecting <strong>the</strong> school and homes to <strong>the</strong>Internet.The Manson <strong>School</strong> District (www.manson.org) operates a successful duallanguage program at <strong>the</strong> elementary level. The program merges <strong>the</strong> mostsuccessful aspects of second language learning with a challenging academicprogram. Students will learn to read and write first in <strong>the</strong>ir dominantlanguage and be part of <strong>the</strong> Manson Elementary Language Leveling program.They will learn about o<strong>the</strong>r subjects in English and Spanish. Instructionwill be divided so that <strong>the</strong>y will learn about half <strong>the</strong> time in eachlanguage. Lessons will not be repeated in each language but will build onone ano<strong>the</strong>r.Cultural CompetenceRace and class inequities are deeply embedded in society’s institutions.Institutions, just as <strong>the</strong> people in <strong>the</strong>m, must be culturallycompetent. This means that schools and school districts reflectpolicies, practices and structures that promote equity and respect for diversity.It also means that educators must understand <strong>the</strong> culture of poverty.As explained by Ruby Payne, in A Framework for Understanding Poverty,children bring with <strong>the</strong>m “hidden rules” and patterns of thought, socialinteraction, cognitive strategies and o<strong>the</strong>r patterns of <strong>the</strong> class in which<strong>the</strong>y were raised, and many are very different than those operating inschools driven by middle class patterns and rules.To close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap, <strong>the</strong>re must be understanding of <strong>the</strong> impact oflanguage, culture, race and poverty on student achievement. Students fromWASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION27

economically disadvantaged families and communities often have differentbasic values and needs, and it is <strong>the</strong>se differences that often create conflictat school. Behaviors of students from cultures different from those of <strong>the</strong>teacher are often not understood and can be misinterpreted by school staffwho have had very different life experiences.The vast majority of teachers in <strong>Washington</strong> state are mono-cultural andmonolingual while student bodies are increasingly culturally diverse, bilingual,and English language learners.Students of color and students from poverty often bring experiences and anunderstanding of history and knowledge that <strong>the</strong>y do not see representedin <strong>the</strong> teaching and learning taking place in <strong>the</strong> classroom. For example,relevancy of curriculum for American Indian students is questioned when<strong>the</strong>y do not see <strong>the</strong>ir culture and languages represented in <strong>the</strong> curriculum.All staff must be trained in how <strong>the</strong>ir own culture and behavior affectsculturally and linguistically different students. These behaviors and culturaldifferences include how families perceive schooling, values and expectationsof <strong>the</strong> culture and simple things, like gestures and mannerisms.Staff need <strong>the</strong> skills to teach children to be “bi-cultural,” to succeed inschool and <strong>the</strong> workplace while remaining culturally proficient in <strong>the</strong>irhomes and neighborhoods.Attitude plays a key role in how individuals interact with each o<strong>the</strong>r. Biasedattitudes of particular cultural and socio-economic groups significantly altera school’s learning environment. A negative attitude breeds a negativeschool climate, and positive attitudes send clear messages that all are valued.Care must be taken to not let biased attitudes establish differentachievement expectations for students from different backgrounds.Questions to Guide <strong>the</strong> Discussion1. What dialogue on education and race have been held in <strong>the</strong> schoolsand communities? Do staff understand <strong>the</strong> impact of culture and raceon learning? Have <strong>the</strong>y been educated about <strong>the</strong> culture of povertyand its effects on learning?2. What false assumptions are held about English language learners,children and families in poverty, and students who are culturallydifferent? What false assumptions operate about parent’s willingnessto be involved in <strong>the</strong>ir children’s education? What unresolved issuesabout race and class exist that are known to influence education?3. How culturally competent is <strong>the</strong> educational system, board and staff?What can be done to be more culturally responsive?28CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE

Policy Recommendations1. Develop and adopt policies that express <strong>the</strong> board’s philosophy aboutequity and cultural competence. Affirm <strong>the</strong> board’s philosophy aboutequity and excellence through a statement of core beliefs that is posted inall schools. Be explicit in <strong>the</strong> policy about undoing racism.2. Join leaders in <strong>the</strong> community, including <strong>the</strong> faith-based community, tocall for a dialogue on race and <strong>the</strong> culture of poverty. Form communitystudy circles and book clubs to educate staff and o<strong>the</strong>rs on differentcultures and race issues.3. Provide for and support ongoing professional development to ensure thatstaff are culturally competent and hold high expectations for all students.4. As a board, meet with students on a regular basis to hear <strong>the</strong>ir voices andengage <strong>the</strong>m in helping to create a learning environment free of racism.What <strong>School</strong> Districts Are Doing<strong>School</strong> boards can adopt aggressive policies about eliminating racism. TheTukwila <strong>School</strong> Board (www.tukwila.wednet.edu) recognized <strong>the</strong> increasingcomplexity of assuring equity and excellence and <strong>the</strong> destructive nature ofracism by individuals and institutions, and sought to undo racism through<strong>the</strong> adoption of a school board policy. The board adopted five principlesthat commit <strong>the</strong> district to:Undoing racism and eliminating prejudice, bigotry and discriminationin schoolsEliminating disparities in achievement and in <strong>the</strong> administration ofdisciplineProviding educational experiences that reflect racial, cultural, andlinguistic diversityProviding comprehensive training to staff to respond to diversityEnsuring a supportive school environment in which each student hasan advocateThe Federal Way <strong>School</strong> District (www.fwsd.wednet.edu) created a taskforce that spent a full summer developing action plans to address its persistentacademic achievement gap between black, Hispanic, American Indianand <strong>the</strong>ir white and Asian peers. An Office of Equity and <strong>Achievement</strong> wascreated and specific goals for closing <strong>the</strong> gap were developed.Seattle Public <strong>School</strong>s (www.seattleschools.org) developed <strong>the</strong> DistrictAction Plan to Eliminate Disproportionality following recommendationsfrom a district Action Committee on Disproportionality. The committeewas formed in response to data showing African American students beingsuspended or expelled twice as often as white high school students andWASHINGTON STATE SCHOOL DIRECTORS’ ASSOCIATION29

“We need to look inside ourdistrict. What’s important isthat we do not makeassumptions about anychild.”— Diane TurnerFederal Way <strong>School</strong> Districtthree times as often as white students in middle school; significantly higherdropout rates for students of color; and much higher percentages of studentsof color scoring below <strong>the</strong> 25th percentile on <strong>the</strong> ITBS.Throughout <strong>the</strong> entire school year, conversations on race will occur thatbegan with an August symposium focused on <strong>the</strong> elimination ofdisproportionality. The district’s action plan also addressed <strong>the</strong> need toimplement strategies to address and eliminate stereotyping and o<strong>the</strong>r biasesin special programs. The bilingual, highly capable and special educationprograms have been or will be reviewed.Time and Opportunity to LearnTime is a resource. A strong correlation exists between time on taskand improved academic performance. On a national level, <strong>the</strong>Commission on Time and Learning has found that—Ensuring that all students learn to high standards will require flexibilityand innovation in <strong>the</strong> use of common core learning time, as well as<strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> time students spend both during and beyond <strong>the</strong> schooldayIncreasing <strong>the</strong> amount and duration of intensive, engaging and challenginglearning activities geared to high standards can increase studentmotivation and achievementThe benefits of extending learning time, including common coreinstructional time, can be maximized by concurrent changes in curriculumand instruction, such as accelerated learning, and engaging,interactive instruction based on challenging contentTo close <strong>the</strong> achievement gap, those students who are <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>st behindmust have increased opportunity to learn to “catch up” and close <strong>the</strong> gap.The table below illustrates that if opportunity to learn in reading is heldconstant to meet <strong>the</strong> three-year 25 percent reduction goal in <strong>the</strong> number ofstudents not meeting standard, most American Indian, black and Hispanicstudents will not meet standard until well past 2008.Trend Needed to Meet 25% Improvement Goal — Grade 4 Reading2000200120022003200420052006200720082009201020112012AmericanIndianAsian/PacificIslanderBlack/AfricanAmericanHispanicWhite46.951.8 56.2 60.2 63.8 67.1 70.1 72.9 75.4 77.6 79.7 81.5 83. 266.769.7 72.5 75.0 77.3 79.4 81.3 83.0 84.5 86.0 87.2 88.4 89. 547.752.5 56.8 60.8 64.4 67.6 70.6 73.3 75.7 77.9 80.0 81.8 83. 539.444.9 50.0 54.6 58.7 62.5 65.9 69.0 71.9 74.4 76.8 78.9 80. 871.874.4 76.7 78.9 80.8 82.5 84.1 85.6 86.9 88.1 89.2 90.2 91. 1Source: OSPI, Research & Evaluation30CLOSING THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP: A POLICY ACTION GUIDE