SWEET HAZARDS - Terre des Hommes

SWEET HAZARDS - Terre des Hommes

SWEET HAZARDS - Terre des Hommes

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

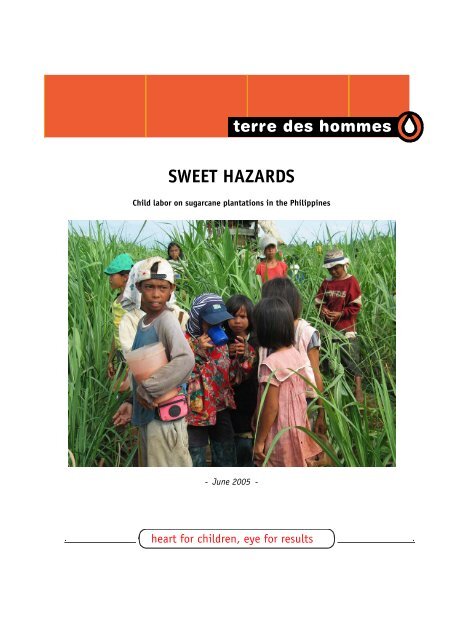

<strong>SWEET</strong> <strong>HAZARDS</strong>Child labor on sugarcane plantations in the Philippines- June 2005 -heart for children, eye for results

<strong>SWEET</strong> <strong>HAZARDS</strong>Child labor on sugarcane plantations in the PhilippinesAuthor: Jennifer de Boer, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands© <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands, 2005All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be madewithout permission from the publisher.<strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> NetherlandsZoutmanstraat 42-442518 GS Den HaagThe NetherlandsTel.: +31 (0) 70 310 5000Fax: +31 (0)70 310 5001E-mail: info@tdh.nlwww.terre<strong>des</strong>hommes.nliii

<strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong><strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands (Earth of Mankind) is a Dutch child focussed developmentorganisation based in The Hague. Founded in 1965 as a non-profit organisation, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong><strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands aims to improve the quality of life of deprived children by ensuringtheir rights.Through partnership with local, non-governmental organisations <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong>Netherlands supports projects and programmes which help to protect children from worstaspects of poverty and to create better and sustainable opportunities for them.The objectives of <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands include the provision of immediate andefficient support to children in need through services, which not only upgrade the generalconditions of the child, but also contribute to the community at large.In addition, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> Netherlands advocates, on national and international level,child rights, as laid down in the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.iv

IndexForewordvii1. Introduction 12. Child labor 33. Child work on sugarcane plantations 74. Responses 155. Conclusion 21Annex 1: Literature 25Annex 2: List of interviews 27Annex 3: Chemical hazards of agricultural child labor 29v

ForewordAs a child rights organization, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> works for and with children. In creating aworld where children can enjoy their rights, we need the support and protection of adults.This research report was set up within that same principle. The research was carried out inthe field by talking to children and by asking them to share their daily realities and theiropinions. Their parents, their employers, their government representatives and their plightbearers all contributed visions and opinions to the research. Together, they form the world ofworking children and together they can change it.I would like to thank ECLIPSE for the partnership, their support and their contributions tothe research; the children and communities of Talisayan, Patag, Sumangga, Masarayao,Valencia, Magsaysay, Luayon and Malalag Cogon; the OHSC, FPA, ILS and DOLE departments;mr. Romeo Quijano for his knowledge on pestici<strong>des</strong>; and all others who contributed to thisresearch. Also, I would like to thank Alex Apit for commenting on the draft report and LizaApit for her assistance in Mindanao. Lastly, I want to thank Telay for her support andorganizing talent.With this report, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> illustrates how different factors and different actors areresponsible for turning child work into intolerable forms of child labour. It’s up to all of us tojoin forces in the struggle against the exploitation of children.Jennifer de BoerChild Rights Policy OfficerTERRE DES HOMMESvii

viii

1. IntroductionAs a child rights organization <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong><strong>Hommes</strong>, together with her local partners,fights to eliminate child labor. Followinginternational policy frameworks on childlabor, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> contributes to theelimination of the worst forms of laborperformed by children through programs,advocacy and campaigning. However clear theinternational guidelines may be on childlabor, the daily reality in which children findthemselves often does not fit into the clearframeworks as outlined by policy makers. Thisresearch, a case study on the sugarcaneplantations in the Philippines, takes a closerlook into the reality of working children’slives in order to measure this reality againstthe international policy framework on childlabor. The situation on the sugarcaneplantations is illustrative of the hazardousforms of child labor, which are oftenoverlooked by policy makers and researchers.Furthermore, plantation work illustrates thegrey area between children’s work, child laborand the worst forms of child labor –distinctions that influence the protectionoffered to children.Research methodologyThe aim of the research is to gain moreinsight into the situation of children whowork on the sugarcane plantations in thePhilippines in relation to the (chemical)hazards they encounter and to identifymeasures that will improve their situation.The following questions guide the research:What is the general child labor situation inthe Philippines? Why and how is child labormaintained in the sugarcane production? Towhat extent are children threatened byhazards in this work? And what action isneeded to end the existence of child labor inthis particular form of agriculture?Information was gathered by means offocus group discussions with parents andchildren on the islands of Leyte andMindanao and by interviews with other keyplayers like local government officials, alandowner, medical staff, a toxicologist,representatives from various governmentinstitutions such as the labor inspection andthe fertilizer and pesticide authority and staffmembers from <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong>’ partnerorganization ECLIPSE who are activelyinvolved with working children in thesugarcane fields of Leyte 1 . Most of theinterviews, except for the interviews withgovernment officials, were conducted withthe assistance of an interpreter. 2 Field visitswere made to various sugarcane plantationsin Leyte in order to observe the situation inthe fields. Secondary sources, for exampleresearch reports by other institutions,information materials from governmentbodies and newspaper articles, areincorporated in this study.Scope and limitations of the studyThis report aims to illustrate the hazardouslabor done by children worldwide byhighlighting one particular case. Beingillustrative, the report aims at telling thestories of the children’s daily workingconditions at the sugarcane plantations inLeyte, the Philippines. It does not attempt tobe complete in its account of these workingand living conditions, nor does it pretend tospeak for all children involved in hazardouswork of any kind. However, it is <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong><strong>Hommes</strong>’ conviction that the children fromthe sugarcane plantations around Ormoc faceand voice problems that are of equalimportance to other children in the world.The field research was carried out withina limited time frame. However, the long timeinvolvement of <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> partnerorganization ECLIPSE in this area provi<strong>des</strong> asound basis for the observations and analysis1 ECLIPSE was founded in 1996 in Ormoc. Their name isan acronym for Exodus of Children from Labor Into Play,Socialization and Education. Apart from being anacronym the name was chosen because the children inthe sugarcane plantations wish for the sun not to shinewhile they are at work.2 For a complete list of interviews see Annex 21

of the underlying study. Furthermore, thefield research is complemented by andcrosschecked with the findings of similarstudies conducted by other organizations andgovernment agencies.This report begins with an exploration ofchild labor. By determining what child laboris and which forms it takes, chapter oneprovi<strong>des</strong> the broader context in which theresearch is placed. The report then focuses onthe situation on the sugarcane plantations inthe Philippines. What is the role that childrenfulfill in the production of sugar and why dothey work? Because the acceptability ofchildren’s work is subject to internationalrules and standards, the fourth chapter takesa closer look at the hazards of the work inthe fields. Chapter five explores the responsesof the different stakeholders to child laborand their responsibilities in resolving theissue in the sugarcane plantations of thePhilippines. Finally, conclusions are drawn onthe nature of children’s work on thesugarcane plantations and somerecommendations are given for improving thesituation for these children and futuregenerations.2

2. Child laborConcern over children’s well being in relationto the work they perform makes theinternational community determined to tacklechild labor. But what is child labor? Whichkinds of work do we perceive as normal forchildren, and which kinds of work areabsolutely not suitable for minors? Theinternational child labor debate has beengoing on for several deca<strong>des</strong> now, resultingin different definitions and approaches. First,the International Labor Organization (ILO)set minimum ages in its convention 138.Agreement was sought over the age at whichwork can be allowed as a necessary or evenuseful part of young people’s lives. Alleconomic activity performed under theminimum ages is perceived as ‘child labor’ bythe ILO.Choosing a different line of thought, theUN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) defines child labor not so much in strictage-related terms, but more in terms of workthat threatens a child’s development. Itstresses that adults should protect childrenfrom this threat:“State parties recognize the right of thechild to be protected from economicexploitation and from performing any workthat is likely to be hazardous or to interferewith the child’s education, or to be harmfulto the child’s health or physical, mental,spiritual, moral or social development.” 3Child labor is viewed by the UN as work thathinders a child in his or her enjoyment ofchildren’s rights. As the UN CRC is signed andratified by almost all countries in the world 4 ,states are bound to take measures againsteconomic exploitation and other harmfulforms of work. Even though the UN CRC maybe very all-encompassing on the issue ofchildren’s economic exploitation, states needclear definitions on what it is exactly thatthey want to tackle when drawing laws and3 UN CRC article 324 Exceptions are the United States and Somalia.policies to protect children from laborexploitation. By amending the UN CRC withtwo Optional Protocols – one on prostitution,pornography and the sale of children, theother on the use of child soldiers – the UNCRC goes into details on at least two forms ofexploitation that affect children worldwide.Still it is the ILO that provi<strong>des</strong> states withthe most comprehensive series of definitions,drawing lines between child work, child laborand worst forms of child labor. In this respect,the ILO plays a major role in setting theagenda for child labor issues worldwide. Itconsiders child labor to be“work situations where children arecompelled to work on a regular basis to earna living for themselves and their families,and as a result are disadvantagededucationally and socially; where childrenwork in conditions that are exploitative anddamaging to their health and to theirphysical and mental development; wherechildren are separated from their families;often deprived of educational and trainingopportunities; where children are forced tolead prematurely adult lives” 5Other situations where children work – forinstance helping their parents in thehousehold for a few hours every week – arenot considered child labor but merely childwork. In an attempt to give more impetus tothe abolition of child labor the ILO furtherdistinguishes between child labor and the socalled‘worst forms of child labor’ inConvention 182 (1999):a) slavery or practices similar toslavery (such as child traffickingand debt bondage)b) prostitution and pornographyc) illicit activities (like drug trade)d) work which is likely to harm thehealth, safety or morals ofchildren 65 In: Albada et al. (200?)6 ILO C182 Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, 19993

Apart from defining the most intolerableforms of work that children can be trappedinto, the convention sets policies for theelimination of these types of work. It placespriority on the abolition of the abovementionedwork for children. Theinternational community, faced with anenormous amount of working children andnot enough capacity to resolve the childlabor issue all at once, agrees on the urgencyof eliminating at least the most detrimentalforms of child labor. 7 ILO convention 182offers the necessary definitions and draws thelines on what governments should prioritize,requiring a set series of measures fromgovernments for each type of labor: worstforms are to be eliminated immediately, otherforms should be restricted in time byestablishing minimum age laws and otherlegal frameworks that protect children fromexploitation.Without denying the value of ILO’sconventions in the battle against child labor,it can be argued that dividing child labor intoworst forms and other forms leads tojustification of persisting child laborpractices. The prioritization for eliminatingthe worst forms might be used as an excusefor not working on the abolition of otherforms of child labor. Or it leads to strategiesof improving children’s working conditionswhen not engaged in one of the worst forms.This, as some organizations and academicsargue, will even make working moreattractive to children and will send out themessage that child labor is tolerable. 8Theory and realityAnother problem with the strict demarcationsin ILO’s definitions and subsequently innational laws and policies is that these arechallenged by the realities of workingchildren’s lives, as children are not bound toone category of work per se. Sociologist BenWhite presents a view where child workshould be seen as a continuum. On one endof this continuum we find acceptable formsof work, situations where children help theirparents but still go to school for instance. On7 Myers 20018 See for example Lieten 2003this side, work can be even considered to bea valuable part of the child’s upbringing:learning discipline and responsibility. But thecontinuum flows from there through lessacceptable and unacceptable forms of work tosituations where children’s work cannot beaccepted under any circumstance. Somewhereon the continuum the valuable contributionsthat working can bring to children’sdevelopment do not outweigh the negativeconsequences anymore.This view offers a wide range of policyoptions and program interventions toorganizations working with economicallyactive children. TdH uses this spectrum ofinterventions in its fight against childexploitation. Recognizing that the ultimategoal of all anti-child labor efforts may be toestablish a world in which no child has towork, <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> takes the eliminationof child labor in its worst forms as a startingpoint, in correspondence with ILO convention182. However, the organization further workson improving the working and livingconditions of working children who are notengaged in worst forms of child labor. InTdH’s experience children sometimes do notobject to working as such, but they doexpress the wish for better workingsituations. Taking the best interest of thechild as a basis for action, TdH is convincedthat improving the work environment ofchildren can contribute positively to theirdevelopment. Of course, these interventionsare highly dependent on the specific contextand are not applicable to every work situationin which children are involved. Also it mustbe noted that the choice to support childrenin their wish for better working conditionsdoes not hinder most of TdH’s partnerorganizations to work towards theelimination of certain types of work.Improving children’s working conditions is astep in the process towards better chancesfor development for all children.In practice, labeling certain types of workdone by children as the ‘ worst forms’ andothers as plain ‘child labor’ is not as easy asit sounds. When encountering children whowork as prostitutes or who are sold andtrafficked as commodities, it is obvious thatthese violations of their rights should be put4

to an end immediately. However, when it isnot the job per se but the circumstancesunder which the work is carried out that posea threat to the child’s well being, the picturebecomes more vague. It becomes difficult todraw the line between tolerable work andharmful practices when children move fromone end of the continuum to the other,depending on the season or on other factorsthat provide an ad-hoc need for additionallabor performed by children. Children’s workon the sugarcane plantations in thePhilippines illustrates the practicaldifficulties of labeling and tackling children’swork within the international policyframework. As the next chapter will show,children’s work on the plantations is highlyflexible and children can move in and out ofthe ‘ worst forms of child labor’, so to speak.Because of the policy implications of thismovement, children’s work on the sugar caneplantations presents an interesting case forboth governments and NGOs.5

3. Child work on sugarcane plantationsFilipino children grow up in a country thatcomprises more than seven thousand islands.80 million people inhabit these islands. Atfirst sight, the Philippines are doing well. TheGNP is over a thousand dollars per year and aFilipino can expect to live for seventy years.The national economy survived the crisis thathit the region in the late 90’s and thecountry’s main worry at the moment is theunrest on the southern islands of thearchipelago. But the good statistics andfigures do not guarantee a joyful youth forFilipino children. Five million households livebelow the poverty line of 1 dollar a day perperson, surviving on 5000 pesos (74 euro) permonth to feed and cloth an average of sixfamily members. Education is free, yetadditional costs make education anunreachable dream for too many Filipinochildren.Children’s rights are being violated dailyin the Philippines. One of the ways in whichthis happens is through child labor. Eventhough the government signed and ratifiedimportant international agreements on theelimination of child labor, an estimated fourmillion Filipino children work. Some of themhelp out a few hours per week; others areexploited through one of the worst forms ofchild labor as defined by the ILO. Yet it isclear that most of the children do not workfor extra pocket money since three millionout of four million economically activechildren give at least part of their earnings totheir families. While younger children give allof their earnings, older children have somemoney for themselves, which is mostly usedto pay their own education costs. Working isa necessity for them.At a time when much attention goes tothe horrors of child prostitution andtrafficking of children in the Philippines, thesector where by far most children work,agriculture, is often forgotten. It isestimated that 2.3 million children areeconomically active in this sector. Agricultureis traditionally a very important source ofincome for the Philippines. According to theDepartment of Agriculture, the sectorcontributed 23% to the gross domesticproduct in 1995 and has continued to grow.The crops are cultivated on about 47% of thecountry’s land area with the labor of one-halfof the Filipino labor force. In order to keepproviding income for the growing ruralpopulation and to sustain the expansion ofthe national economy, the government islooking for ways to increase the productivityin this sector.Since the agricultural sector is oftenmistakenly understood to mean working onthe family farm, it tends to be overlooked asan area in which exploitation of childrentakes place. In reality, the agricultural sectorhas its exploitative variants in commercialfarm work and bonded labor, and poses manythreats to children. A national survey on thesituation of Filipino children conducted in2001 does not distinguish between childrenworking on their family’s farm or childrenworking in commercial agriculturalundertakings like plantations, while both ofthese forms of ‘working in agriculture’ havedifferent consequences on children. Thesurvey report states that most children areworking in the agricultural sector and thatsixty percent of the working children areunpaid workers in household-operated farmsor businesses. 9 These findings present a viewof children’s work in the agricultural sector as‘helping out their parents on the family farm’where rice, corn, vegetables and fruits aregrown. In fact, the view of children’sagricultural work as helping out – which isconsidered to be non-hazardous for children -is shared by sectors of the Filipinogovernment. But this means that thethousands of children working in commercialfarms are overlooked. Commercial farms andplantations in the Philippines grow coconut,banana, pineapple, tobacco and sugarcane.These commercial crops are sold at the9 National Statistics Office 20037

domestic market, as well as on the exportmarket. Children working on large scaleplantations are in much greater risk ofexploitation due to the profit-orientedapproach of the commercial undertakings.Also, by assuming that agricultural work isdone by children under the supervision oftheir parents, one assumes that children areprotected from the hazards of farm work.Thus seen as non-threatening family work,agricultural work as a category is notprioritized as a form of child labor that needsto be eliminated immediately.In reality however, exposure to hazards inagriculture is tremendous. Sixty percent ofthe Filipino children in this sector strugglewith health problems as a result of the workthey perform. Figures from the NationalStatistics Office reveal that 61% of thechildren working in agriculture, forestry andhunting are exposed to physical hazards.Among these hazards are temperature andhumidity. Chemical hazards were reported tothreaten 53,000 children in agriculture. 10Sugarcane plantationsThe island Leyte, part of the Visayas, lies inthe middle of the Philippines. The land isfertile and Leytes villages and cities aresituated amidst green fields and coconuttrees. Nevertheless, the inhabitants of thebarangays (neighborhoods) are among thepoorest of the Philippines. Most of them areworking on other people’s land, surviving ondaily wage labor with earnings that lie belowminimum wage. Many families live and workon the island’s eleven big sugar caneplantations. It is estimated that more than5000 children work there too. Leyte provi<strong>des</strong>an opportunity to understand the dynamicsof child work in the Filipino sugarcaneplantations.Sugarcane is traditionally an importantcommercial crop for the Philippines. The totalproduction in the Philippines came to 2.3million tons of sugar in 2004. Most of it isused for the domestic market, but ten percentis exported to other markets like the UnitedStates, South Korea, Japan and China. In1997 the sugar industry contributed 3010 National Statistics Office 2003billion pesos to the national economy 11 ,which is about 2.5% of the GNP. The SugarRegulatory Authority (SRA) of the Philippinegovernment estimates that some 5 millionFilipinos depend on the sugarcaneproduction, among which children who workin the fields. The presence of children in thesugarcane labor force has been recorded since1909. 12 Although several plantations todaystrictly follow the laws on child labor and donot allow children to work in their fields 13 ,the Department of Labor and Employment(DOLE) estimates that 60,000 children workon Philippine sugarcane plantations.However, Apit (2002) estimates the numberat 200,000 basing his calculation on reportsfrom sugarcane workers.Inhabitants of some Philippine islandsalready grew sugarcane as a food crop whenthe Spaniards arrived in the 16 th century. Assoon as the colonial powers discovered theinternational market for the sweetener, theybegan to grow sugarcane on plantations,particularly on the island of Negros. By thebeginning of the 20 th century America tookover the power from the Spaniards in thePhilippines. The US created a steady marketfor the Filipino sugar, thus supporting itsproduction. Rich families expanded the sugarcane plantations to other islands outsideNegros, such as Leyte. Many small farmerssold their lands to the bigger landowners andtried to find a job as ‘hornals’ (agriculturaldaily wage workers) on the sugarcanehaciendas. They were offered the chance tolive on the hacienda and remained theregeneration after generation. The hacienderos- rich Spanish families - took care of theirworkers, providing them medical care andloans creating a mutual dependency betweenthe hacienderos and the workers.The guaranteed market created by theoccupying United States in the first half ofthe 20 th century contributed to the wealth ofthe hacienderos, but when the United Statesleft, they took their trade-privileges withthem. Gradually, the amount of sugarimported by the US decreased. Opening the11 Rollolazo&Logan, 200?12 Apit 200213 Rollolazo&Logan, 200?8

Philippines to the global sugar market in1974 worsened the situation because theprices of locally produced sugar could - andstill can - not compete with the globalmarket. 14 “There was a time when the sugarwas sweeter” say some Filipinos whenspeaking of the declining income in the sugarindustry. Presently, even with thegovernment subsidies, the price of Filipinosugar is higher than that of other sugarproducing countries, like Brazil. One factorcontributing to the present uncompetitiveposition of the Filipino sugar is the lack ofmodernization. For deca<strong>des</strong> there has been noincentive for modernization, since the sugarwas bought by the US for a set price. Onlyrecently has the government recognized thatreform of the production processes in theagricultural sector is necessary for thecountry’s economic development.Living conditions of the sugarcane workersThe biggest losses of the current situation arefelt in the households of the workers, thehornals. Some families have lived there forgenerations; others have arrived recentlyfrom the mountainous areas looking for work:sugarcane needs to be planted yearly in thePhilippines. There is weeding to be done –manually. Applying fertilizers and controllingpests is necessary during the planting andgrowing season. And of course there is thestrenuous harvest at the end of the season.The workers get paid 60 to 80 pesos per day,which is far below the minimum of 153 pesosper day 15 that is prescribed by thegovernment.Most plantation owners offer theirworkers a house on the plantation itself.These barracks are built on the haciendas outof bamboo, cane and palm leaves. Drinkingwater is mostly obtained from pump wells, asthere are no sanitation facilities near thehouses. The houses stand closely togetherand are overpopulated with average familysizes of eight to ten people. They are dividedinto two or three small spaces and areaccommodating families up to twelve or14 Garcia-Dungo, 199415 As stipulated in Per Wage Order No. RB VIII-10a(effective January 18, 2002)thirteen people. Most families on thehaciendas are big, since birth control is notvery propagated in the catholic Philippines.Not all farm workers live on theplantation itself. Those who don’t are a littlebit more independent then the workers wholive on the owner’s land. On the other hand,the hornals (sugarcane workers) who live onthe hacienda are more likely to have workthan ‘outsiders’. The hacienda is a communitywithin a community, with it’s ownorganization and hierarchy. 16 This provi<strong>des</strong>the government with some problems indetermining the extent of their interferencein the hacienda’s business. Since the land isprivately owned, the government is limited inthe construction of roads and otherinfrastructure. This makes the livingconditions on some haciendas worse than innormal villages.The power that landowners have over thehornals is big. Especially the hornals living onthe hacienda are too dependent on thelandowner to question his decisions, sinceboth their jobs and their housing depends onthe hacienderos. As one man claimed: “Theregulation is that to live here you have towork on the plantation. The landowner ownsthe houses, it is his land. So I am not surewhat would happen if my sons would notwork as hornals anymore. I think we would beevicted from our house. The hacienderos donot like it if their people work for othercompanies, they throw you out. There is oneinspector here that even threatens to beatyou up if you do not work for the landowner.If you live here, you are forced to work in theplantation.” Even though it is reasonable thatonly people who work on the plantation areoffered accommodation there, the lack offinancial means to buy other houses force thehornals to stay in the hacienda and acceptthe negative aspects of plantation work.Due to low wages and big families,poverty is wi<strong>des</strong>pread among the sugarcaneworkers’ families. Parents have difficulties infeeding all their children. Even though theland where the families live is fertile, theyare in many instances not allowed to usesmall plots to grow their own food. From this16 Rollolazo&Logan 200?9

perspective the people on the haciendas areworse off then other rural families, who atleast have a backyard where they grow somefruits and vegetables for own consumption orraise pigs. Often, children growing up in theworkers’ families are malnourished as a result.They are susceptible to diseases due to theirbodies’ low resistance. The local health centerin Ormoc knows about the situation.“Malnutrition, pneumonia, coughs; we seethat a lot in children” says Dr. Lampong. “Itis caused by a lack of food but also by lack ofknowledge concerning a balanced diet.People here tend to buy food by quantity, notby quality. Also the immunization levels arelow – the mothers have no time to come tothe hospital to immunize their children.”The people in barangay Sumangga, in theOrmoc district, calculate that the low wagesare by far not enough to make ends meet. Anaverage family of eight persons needs 400pesos a day for basic needs and essentialhousehold items. So they count: “If oneperson earns a salary of 60 pesos per day andfive family members are working, you are still100 pesos short! How do we cope? We borrowfrom the local store, or we don’t eat fishanymore. But when it comes to payingeducation costs or buying new clothes for thechildren, the children need to work for itthemselves. The situation has worsenedduring the years. Under Magsaysay in the1950’s we were better off. Even under Marcoswe were better off because the food priceswere lower!” In an in-depth study of theliving conditions of sugarcane child laborers,the researchers found that a household earnsan average of 3,290 pesos per month, whilethe poverty threshold in that particularregion lies at 10,800 pesos per month. 17 Ingeneral, sugarcane workers do not enjoy anybenefits or pension, which makes elderlypeople dependent on either their own laboror their children’s income.Working childrenAs stated before 60,000 to 200,000 childrenwork in the sugarcane plantations. They areboth pushed and pulled into this work.Looking at the circumstances that push17 Rollolazo&Logan 200?children towards work, some people claimthat parents are lazy and push the children towork to provide income for them. Claims areeven made that people start big familiesbecause of the income that the children canprovide: “The parents allow the children towork for the extra income they provide. Thisis a family planning-issue. The families wantto have many children for the money thatthey earn. They don’t want their familiesplanned!” says a local doctor.Many children themselves however say itis the absolute need for additional familyincome that pushes them into the fields.With their parents’ wages lying far below theprescribed minimum, families cannot makeends meet. Children are aware of the needs oftheir families. When asked why they work,their answers indicate financial reasons first.“I work to buy rice,” said one young worker.Another one told that he was thebreadwinner of the family. “The new schoolyear will start in June so we need new booksand materials. That is why we are workingnow, to be able to pay the education costs”,explained a 12-year old girl who works duringthe holidays, together with her youngersister. The children are aware that theirparents’ income is not enough to provide forthe whole family, and they feel compelled tohelp. Especially boys are expected to helpout. One of them, Amir, acknowledges thisresponsibility that he feels: “I wanted to goto school, but I also want to help my familyso I work. I still want to go to school, buthow?”In his study on the causes andconsequences of child labor in Leyte, De Vriesstates that children’s educational aspirationsstrongly influence their decision to work,since they need money to pay their schoolfees. 18 This is certainly the case with thechildren included in this research. Most ofthem use their earnings to save foreducational costs – their own or theirbrother’s or sister’s. It is common for theolder siblings to sacrifice their own educationfor the schooling of their younger brothersand sisters. Like Vicente, who lives inValencia. He works to earn the money for his18 De Vries, 200110

sister’s education. “She starts the First Gradethis June.” Working to earn his sister’seducational costs does not prevent him fromdreaming about returning to school himself,because he adds: “And myself, I want to goback to school in June, to Grade 5.” InSarangani, working boys estimated theirschool costs at 1000 pesos annually. Thismoney is used for school materials, uniforms,enrolment fees and other additional costs.“We keep 10 or 20 pesos for ourselves, tosave for school materials,” they explain. Therest goes to their mothers, who “need it tobuy food”. There was only one boy who saidthat working children use the money to buycoke and candy for themselves. All othersstated that they needed the money orotherwise they could not go to school or didnot have enough food.The dilemma between the child’s wish andthe family’s need does not go unnoticed byparents either. They too cite financialhardships as the first and foremost reasonwhy their children are working. “There is noother way. We are poor and our own incomeis not enough to provide for the wholefamily. We need the money, so the childrenneed to help,” say parents from Talisayan.“Our economic problems force us to allow thechildren to work,” agree parents fromSumangga.In regards to what pulls children to work,there is an overall demand for children’slabor. In literature it is widely propagatedthat this demand is so big because childrencan be paid less than adults. The reality inLeyte seems to be a bit different. Certainlyfinancial factors play a role, even though thewages of children and adults are more or lessequal. However, the outdated productionmethods in sugar cane ask for many laborersto do the manual work. For instance, keepingthe fields weeded is cheaper if done manuallyrather than by spraying herbici<strong>des</strong>. For thisrelatively simple job children are hired toreplace expensive production methods. What’smore is that children are more docile thanadults. “The sugarcane industry is known forits union history,” explains Alex Apit, “Theadults have been organized, and this haseven led them to armed battle. So now thehacienderos want to prevent trouble in theirplantations. So they hire children, becausechildren don’t join unions. You see, unionsare for working people, and children are notsupposed to work.” Children do not ask foradditional benefits that workers are entitledto and do not stand up for their rights aseasily as adults do.What kind of work?There are big differences between amounts ofwork that children do on the plantations. Atthe age of seven or eight children start tohelp in the fields during school holidays andweekends. During the year they usually endup working more. By the time the harvestseason is at its peak, a lot of children workfour or five days every week. Some of themdo not return to school after the harvest, butmost of them try to combine school and workby working part time. For instance, during anon site visit to a plantation where 39 childrenwere at work, 28 children claimed they alsoattended school. The other 11 childrenworked full time.The young children (7 to 10 years old)usually start with weeding or planting thecane. In the Philippines new stalks of canehave to be planted each year. Once the caneis planted, fertilizer is added to make thecane grow. Fertilizers however also stimulatethe growth of weeds. “Weed is the numberone enemy of sugarcane” according toplantation manager Zosima Larrazabal. Soevery row of cane needs to be cleared ofweeds every few weeks. Since all work is donemanually, this chore provi<strong>des</strong> work to tens ofpeople per hectare. Children can do the work,since it is simple and not as heavy as someother tasks, like harvesting. The childrenclear the fields of grasses and weeds with bigcutting knives called bolos,. For weeding onerow of cane – which stretches for 100 meters– a child receives about 30 pesos. Like 11-year old Joy-Marie: “I earn 30 pesos forclearing one line, 100 meters. I start workingat six in the morning and I finish at five inthe afternoon. It takes me two days to clearone line.”Applying fertilizer is another taskconsidered to be suitable for children. Mostplantations use a mixture of urea and potashto make the cane grow faster and to sweeten11

it. In the first few months of the growingcycle, the mixture of granules is applied nearthe roots of each cane stalk. Groups ofchildren, supervised by an adult, walk intothe fields to spread the fertilizers. Every nowand then they return to reload their bucketsor tins with granules. They use this time alsoto drink some water, until the supervisorsends them back into the fields again.Working eight, nine or sometimes even tenhours, the children earn 60 pesos per day.However, when it comes to pestici<strong>des</strong> whichare used to protect the crops form insects,plant diseases and weeds, the interviewedparents do not allow their children to spraychemicals. Since pestici<strong>des</strong> such asinsectici<strong>des</strong> and herbici<strong>des</strong> are applied byway of spraying, children are not involved inapplying pestici<strong>des</strong>. Parents are aware of thedangers of inhaling chemicals and forbidtheir children to do this job.Harvest time is the time when all labor isneeded to cut the cane and carry it to thetrucks that will bring it to the sugar mills.The cane is high, thick and strong by now.During harvest most plantation owners payper ton of cane that is cut. Take theLarrazabal family for instance. ZosimaLarrazabal: “A cane cutter earns 100 pesos forevery ton of cane that he has cut, so hisearnings depend on how hard he works.”“Harvesting and carrying the cane is heavy,very heavy. Because I work hard I can earn700 to 800 pesos a week. I work five days perweek – Saturdays and Sundays I do not work:I need the time to sleep” tells Rocky (16years old), who is the breadwinner of hisfamily.Unlike in some other cane-growing areasin the world, the sugar cane in thePhilippines is newly planted each year. Afterthe harvest, the fields need to be cleared inorder to be able to plant new cane, workwhich is done by children as well. But whenthe new cane is planted, the fields arecleared of weeds and the fertilizers andpestici<strong>des</strong> are applied, there is no more workuntil the harvest. In this two-month period,there is a huge shortage of income since theworkers – adults and children alike – receiveno daily wages. Usually one member cancontinue the work on the sugarcaneplantation, but the children cannot providethe same amount of additional incomeanymore. Men migrate to cities like Cebu,Tacloban or Manila to look for work. Womentry to grow vegetables and fruit and look forwork on other plantations, like rice fields.People from job agencies from Manila or Cebucome to look for children who are willing totake their chances in the big city. Oftenthese trips do not work out the way thefamilies had hoped: children disappear intoillegal forms of work, are exploited in cityjobs and do not return nor are they able tosend money back to their families.Fortunately the people in Leyte are not soeager to send their children to the citiesanymore – but they have had to learn thehard way: from bad experience. Some peopletake credit from the plantation administratorsor others who give out loans. But in the highseason, the families need to pay back theirdebts. So when their children manage to earnextra money by working on the sugarcaneplantation during the rest of the year,parents feel relieved that at least they canfeed their families.HazardsOne of the ways in which child labordistinguishes itself from child work is thelevel of hazards that the job encompasses. Itis too often assumed that working in theagricultural sector does not pose a big threatto children’s well being. This assumption isbased on the false belief that the agriculturalsector is made up of family farms, wherethere is not much harm in the additionallabor that the child delivers to help out thefamily. Working on the family farm does infact expose children to a variety of risks.Even when the job itself may seem relativelyharmless, it is the circumstances under whichthe work is carried out that can create a highrisk to the child. Furthermore, the storychanges altogether when children do notwork on the land of the family, but incommercial agriculture. Where family farmsmay strive to provide just enough food for itsown consumption, commercial farms are bytheir very nature aimed at gaining a profit.The likelihood of workers being exploitedincreases dramatically. On top of this,12

commercial farms have better access toagricultural chemicals that pose another,often underestimated, threat to the workers’well being.In the sugarcane fields of Leyte, there isno doubt that the first hazard to the childrenis the sun. Almost all children complain aboutthe heat they have to endure while working.While the work in itself is already tiring, theheat makes it almost unbearable. Taking intoaccount that the children work eight or ninehours every day, the exposure to heat isdangerous. The children do what they can toprotect themselves from the sun. They coveras much of their body as possible; in any casethey cover their heads. Other environmentalfactors include the weather changes andsudden rain showers, which can occur inLeyte. “The children work, rain or shine, theytake no rest and sometimes cannot find timeto eat properly,” say the parents. Thecombination of heat and rain makes thechildren susceptible to colds and fevers.For the children who are weeding,harvesting or preparing the soil, theequipment is not suitable. They use bigmachetes to cut the weeds and the cane.These bolos are made for adult handling. Inchildren’s hands they become dangerous toolsthat cause serious wounds. The risk ofaccidents is enlarged because cane is a toughplant and a certain amount of effort isneeded to cut it. As Larimi (12) says, “Thework is heavy, especially cutting the remainsof the cane stalks after the harvest. My backoften hurts. The machete often bounces backfrom the cane stalks if it is not sharp.” Theharder one tries to cut, the more serious theinjury will be when the machete does not hitthe cane but the child’s leg or foot instead. Itis not only the older children who use thebolos but small seven-year-olds as well.Apart from injuries caused by themachetes, the sugarcane leaves themselvesalso cause small cuts on the children’s legsand arms. Snakes and insects living betweenthe sugarcane stalks sometimes cause deadlyaccidents with their poisonous bites.A fourth hazard is carrying the heavyloads of cane during harvest time. Carryingthe cane from the field to the truck andloading it on the truck can be dangerous toadults considering the weight of the cane. Tochildren it is even more strenuous. They loadthe trucks by climbing them while carryingthe heavy bundles of cane on their shoulders.An adult man tells about his accident thathappened during this activity: “The truck wasloaded with cane. But it slipped and the loadfell off. I was buried under the heavy cane. Iwas brought to the doctor who operated onmy spine [he shows us the scars of theoperation] but the lower part of my body wasstill paralyzed. Ever since I have not beenable to work anymore.” Apart from being atiresome and accident-prone job, carryingheavy loads can cause physical damage to thedeveloping children’s bodies.One last, but very important hazard iscaused by the use of agrochemicals in theproduction of sugarcane. Even though notmuch long-term research into the direct andindirect effects of herbici<strong>des</strong>, insectici<strong>des</strong>and fungici<strong>des</strong> has been undertaken, theexposure of the children to these pestici<strong>des</strong>is obvious. Spraying pestici<strong>des</strong> is consideredto be a job for adults only, but children workon fields where pestici<strong>des</strong> have been sprayed.Working in this unhealthy environment harmsthe physical and mental development of theworking children. Prolonged exposure mayresult in severe respiratory problems, skin andeye irritations, reproductive problems and ageneral decline in health status. Since theirbodies are not fully developed, smaller dosesof pestici<strong>des</strong> are enough to permanentlydamage their health. This hazard isparticularly grave since the plantations usepestici<strong>des</strong> that are toxic and are banned inother countries for their poisonous effects onfarm workers. The fact that children in thesugar cane industry are at serious risk ofpesticide poisoning is too often denied. 19The work that children do on theplantations exposes them to differenthazards. The extent to which the children areat risk varies with the tasks they do and theamount of time that they are doing it. Ingeneral, parents are aware of the dangers19 <strong>Terre</strong> <strong>des</strong> <strong>Hommes</strong> is of the opinion that this issueshould receive much more attention. A paper onchemical hazards for children working in agriculture hasbeen compiled, see annex 3.13

that their children are exposed to. But inspite of all the hazards that childrenencounter, child labor in the sugarcaneplantations is still wi<strong>des</strong>pread. The questionis to what extent children and parents are ina position to change this situation and howthe government can eliminate this hazardousform of child labor.14

4. ResponsesMost parents, children and others involved inthe sugarcane plantations agree that a childideally should not work. However, child laborstill persists on a large scale. Apart from thediscussion if children should be working atall, children themselves indicate that thehazardous working conditions in thesugarcane plantations bother them.Improving working conditions seems toprovide a solution to this problem. However,there is discussion about the effect thiswould have on the child labor situation. AlexApit explains the dilemma: “What makes itvery difficult is of course that child labor isprohibited. So you can hardly work onimproving their labor conditions, becausethey are not allowed to work in the firstplace! This is a matter of discussion betweenNGOs as well: should you improve the workingconditions of children or is that only makingthe work more attractive to children? Are youimproving or worsening the situation if younegotiate for better wages for children?”This issue is of particular relevance forthe children in the sugarcane plantations.Considering the hazards they encounter, partof their work can be classified as a ‘worstform of child labor’. Working more than tenhours per day, performing heavy work underthe heat of the sun, using dangerousequipment and being exposed to chemicalsubstances all contribute to the classificationof the work as ‘hazardous’. Since the worstforms of child labor are to be bannedimmediately, child labor on the sugarcaneplantations should be abolished immediately.The problem is that the hazardousclassification only applies to some tasks orspecific conditions at the sugarcaneplantation. I.e. a child who works four hoursa day at the plantation and who is protectedagainst exposure to heat, chemicals andother physical or biological hazards is notinvolved in a ‘worst form’ of child labor andtherefore should not be ‘rescued’ from thatwork immediately. In view of the fact thatchildren on the plantations perform differenttasks with different intensity during the year,it is hard to say whether all of theirplantation work is a ‘worst form of childlabor’ and for that reason should be abolishedimmediately. However, it is clear that theconditions that make the work hazardous(heat, long working hours, unsuitableequipment and exposure to chemicals) shouldbe banned immediately for children.When asked who is responsible forprotecting the children against the hazards ofworking on the plantations, there aredifferent reactions. First of all, parents feelresponsible. They are however puzzled overthe question how to change the situation andsee no opportunities to end their financialneed for children’s income. Some parents orchildren suggest they should work evenharder (“We could maybe work 11 hours everyday – so that we earn a bit more”), or try tofind other sources of income such as raisingpigs or growing vegetables. There simply areno other, better-paid jobs around and askingthe landowners for minimum wages is notseen as an option. It would mean riskingtheir jobs and thus aggravating the situation.A NGO worker tells: “We had an experience inSarangani where the workers asked for higherwages. They landlord told them they couldlook for higher wages elsewhere, meaningthat asking for higher wages leads tounemployment.”The responsibility for increasing wageslies with the landowners. They argue thatthey cannot raise the pay for the adultlaborers because of two reasons. One is thatthe present low market prices of sugarcaneand the uncompetitive situation of thePhilippine sugar on the global market leaveno room for higher wages. The other is thatraising the wages of laborers will onlyincrease the prices of the commodities theyproduce. This means that the prices of theirdaily needs will also increase. In the endhigher wages will not contribute to a betterfinancial situation for the families, is theargument.15

However, deciding on the wages is notonly in the hands of employers. ThePhilippine government has set minimumwages for each region and each sector ofwork. As became clear during the research,the wage of the hornals in Leyte is 60 pesosper day while the actual minimum is 153pesos. The government labor inspectionreports do show that on some plantations thepaid wages were below the minimum, but thedeviance was only small and underpaymentdid not occur on many inspected plantations.So even though the adult workers on theplantations have the law on their side,increasing the wages is not a realistic optionas long as law enforcement lags behind.When it comes to ending child labor bynot hiring children anymore, landownersclaim that it is not in their power to do thiseven though they agree that children shouldnot work. As one plantation administratorputs it: “I don’t like it, I don’t want kids towork! But when I say that to them they justsmile, look innocent and work!” Anotherperson in the line of plantationsubcontractors claims that even if he wouldnot hire children, the parents would be angrywith him. “I think it’s not good for thechildren to work here. I pity them. And Iwouldn’t want my own children to work here.But as a kapatas I cannot push the otherparents to do the same. They want theincome to lead an easy live! So even if I wasforbidden to supervise a team of children theparents would be mad at me for notemploying the children.”Indeed, the parents and children doexpress the wish for income generatingopportunities for children. But this wish isborn out of financial necessity, as parentsand children state. Children want to workbecause they want to eat, or – very often –because they want to go to school and theyneed money to do that. Many parentsconsider it their responsibility to ensure thatchildren can go to school, seeing educationas a way out of poverty and child labor. “Iwill not allow my children to drop out ofschool. Even if they progress only slowly andhave to skip classes: I want them to continuestudying.” With education children will beable to find better jobs, is the generalfeeling. Because even simple jobs likeworking in a household requires some skills.“You should know how to read if you need tooperate the household machines” a motherfrom one of the villages comments.Landowners feel that employing childrenprovi<strong>des</strong> an opportunity for them to earn themoney that is needed for education. In thisway they see the employment of children as aform of welfare, even though in principlethey agree that children should not work. “Itis my opinion that children should not beworking, so I help them by offering them anopportunity to earn money for theiradditional educational expenses.” saysZosima Larrazabal.Government responsibilityAs stated earlier, government policies usuallyare based upon the distinction betweendifferent forms of children’s work as offeredby the ILO. This is the case in Filipino childlabor law. The subdivision within children’swork is clearly recognizable, for instance inthe Special Protection of Children AgainstChild Abuse, Exploitation and DiscriminationAct (RA 9231), which was adopted inDecember 2003. The Act is meant to alignnational policies to the spirit of ILO C182. 20It stipulates that children below fifteenare not allowed to work. There are twoexceptions to this rule: children workingunder the sole responsibility of their parentsare allowed to work if the child can go toschool and if her or his life, safety, health,morals and development are not endangered.The second exception is made for children inthe entertainment industry, like radio andtelevision. But in any case children belowfifteen are not allowed to work more thanfour hours per day, five days per week.Children between fifteen and eighteen areallowed to work in non-hazardouscircumstances, but never more than eighthours per day, in no case more than fortyhours per week. Also, the laws sees to it thatworking children have at any time access toprimary and secondary education andtraining, be it formal or non-formal.20 Flores-Oebanda 200416

The Act explicitly states “No child shall beengaged in the worst forms of child labor.”(RA 9231 sec. 12-D). The worst forms in thePhilippine law entail the same categories asthe ones mentioned in ILO C182, with theonly difference that it defines the lastcategory (work which is likely to harm thehealth, safety or morals of children) furtheras work thata) degra<strong>des</strong> the worth and dignity ofchildrenb) exposes the child to abuse(emotional, physical or sexual)c) is performed underground, underwater or at dangerous heightsd) involves dangerous machinery andtools (power-driven)e) exposes the child to physicaldanger (like manual transport ofheavy loads)f) is performed in an unhealthyenvironmentg) is performed under difficultconditionsh) exposes the child to biologicalagents (bacteria, parasites, fungi)i) involves explosivesThe Act also provi<strong>des</strong> for penalties forviolators such as employers, subcontractors orothers facilitating the employment ofchildren in any of these ‘worst forms’.Whereas involving children in trafficking,prostitution and drug trade was alreadypunishable under other Acts; Republic Act9231 ensures that the penalties in the case ofchildren will be maximal. Furthermore, thenew Act sets penalties for involving childrenin hazardous work.The Act amends the previous childprotection Act (RA 7610) and is “(…)providing for the elimination of the worstforms of child labor and affording strongerprotection for the working child”. 21 Strongerprotection is needed since the previous Act7610 has not lead to many court filings onchild labor and to even fewer convictions.Also, during its fourteen years of existencechild labor did not cease to exist in thecountry. On the contrary child labor has beenon the increase from 3.7 million children21 Republic Act 9231working in 1996 to 4 million children in2001. 22 Under the new act, children andparents or other concerned citizens can filecomplaints. It is hoped that this law,together with government programs, willcreate the right environment to abolishintolerable forms of child labor.Since the law in the Philippines is clearon what is allowable work and what is not, itis up to the government to enforce these lawsand protect children from exploitation inlabor. In correspondence with ILO convention182 the government is working on a TimeBound Program to end child labor. Six priorityareas are selected for the Time BoundProgram: pyrotechnics, mining, deep-seafishing, domestic work, agriculture andprostitution. Different agencies are involvedin the effort: the Department of Labor andEmployment, Department of Justice,Department of Social Welfare, Department ofHealth, the police and NGOs. The laws areimplemented down to barangay levels, wherethe barangay council for the protection ofchildren is reportedly very effective. “Theyorganize the parents, educate them on thehazards and dangers of letting their childrenwork. They provide peer pressure on thepeople not to let their children work,”explains Mrs. Soriano of the ILS, the agencythat spearheads this network of agenciesinvolved in the elimination of child labor.She adds: “Unfortunately our justice systemhas yet to change, they are still notprosecuting anyone for hiring child workers.Under the new law an employer is actuallyliable, and this liability goes down tosubcontractors as well, to the kapatas forinstance. The law is very strict, but thechallenge now is to enforce it.”One of the law enforcement agencies, theBureau of Working Conditions, conducts laborinspections. These include underpayment,working conditions and minimum ages. Theuse of child labor should be monitored andnoted by this agency. However, theinspection reports of 211 sugarcaneplantations inspected between January andJune 2001 do not indicate one single workingchild. These findings are very contradictory to22 Flores-Oebanda 200417

the observations in this research. Thereappear to be two explanations for thisdiscrepancy. The first reason is that there areonly 250 inspectors nationwide, inspecting800,000 establishments. This means thatinspections cannot be carried out with greataccuracy. Up until now, landowners cantherefore easily mislead the inspectors byincluding false information in their records.Anonymous sources claim that the recordsmention the names of the children who workat the plantation, but only state ages thatare above eighteen. Furthermore, the wagesthat are put down in the records are muchhigher than the actual wages that are paid.Considering the amount of establishmentsthat the 250 labor inspectors have tomonitor, one can imagine their attentiongoes to a look at the books and not to onsite inspections. Thus employers can get awaywith hiring children, even under theinspection of the government. The secondreason for the inefficiency of laborinspections in relation to child labor is theopinion that children working in agricultureonly work on family farms. As the Officer inCharge of the Bureau of Working Conditionsexplains: “We are not so much focused onagriculture. Our Bureau deals with formalemployer-employee relations. And agriculturalchild labor is found more in the informalsector.” When asked, BWC admits “We arealarmed by the statistics on the number ofchildren working in agriculture, but thesefindings do not coincide with the ones fromour inspections.” BWC does expect child laborto be found on sugarcane plantations oncethere is an explicit focus on child labor in theinspections. Faced with the problem of alabor inspection force of only 250 inspectorsfor all establishments in the country, thegovernment is looking for new monitoringsystems. For instance, they let establishmentsmonitor themselves together with the workersafter instructing them on labor standards.Inspection alone is not enough toguarantee the elimination of child labor. “Theproblem is that the parents are the ones whosend their children to work. So it will be abattle between the state and the parents,”says Mrs. Soriano from the Institute of LaborStudies (ILS), an attached agency of theDepartment of Labor and Employment. Sinceremoving the child from his or her family isnot an option (“We don’t have the capacity toremove the children and give them shelter”),a lot of government efforts are directedtoward changing attitu<strong>des</strong> in thecommunities. “You’ll find very poor familieswhere children do not work, and others thatare relatively well off in which the childrenhave to work. So the root cause of child laboris poverty, but it also depends on theattitude of the parents,” explains anotheremployee of the ILS. The government alsorecognizes that the outdated productionmethods in sugarcane create a huge demandfor seasonal labor on the plantations, thusnot providing families with a steady financialbasis. For this reason government programstry to initiate other sources of income for theparents, outside the plantation.When it comes to chemical hazards it isunclear who should protect the children whilethey are at work. Since they are not supposedto work, existing guidelines for safe use ofagrochemicals are not adjusted to children’ssusceptibility to poisoning. And, as the OSHC(Occupational Safety and Health Center)states: “Manufacturers do not label theirchemicals properly, so usually there is noinformation on the content, on safe use, onhandling emergencies. The retailers and thesellers are absolutely also responsible, as arethe buyers. Sometimes the farmers will buy itby the gallon, so they can find no labels withinformation.” Even if workers knew thisinformation and the measures were facilitatedby employers, this would still not protectchildren at work.Further restrictions on pestici<strong>des</strong> andother chemicals could limit the exposure tohighly toxic substances. Yet it seems that toomany parties have an interest in pertainingthe situation as it is: pest control producersand handlers do not want to see their marketdecreased and the government can not closeits borders to chemicals unless they can provetheir poisonous effect on human beings.Although the government is aware of thetoxicity of pestici<strong>des</strong>, market demands aremore important. “We cannot afford to bechoosy,” jokes Mr. Sabularse from theFertilizer and Pesticide Authority. But this is18

the reality: farmers and landowners want tosell their produce and do whatever is needed.The Occupational Safety and Health Center:“The agrochemical industry promotes the useof pestici<strong>des</strong> and trains the farmers. But theygave the wrong signal: it is OK to use it inlarge amounts.” As said above, adjustingsafety guidelines to children’s bodies is notan option because it would mean a silentagreement with the fact that children areapplying pestici<strong>des</strong>. However, banningpestici<strong>des</strong> is not an option either since toomany stakes are in the pesticide market. Thebest way to protect children from thechemical hazards they encounter in thesugarcane fields then is to remove them fromthis harmful work.19

5. ConclusionIn the international child labor debate, andconsequently in national laws and policies,distinctions are drawn between child laborand so-called ‘worst forms of child labor’which are to be eliminated without furtherdelay. Even though many NGOs andgovernments welcome this priority on one ofthe most wi<strong>des</strong>pread violations of children’srights, in practice the borders between childlabor and worst forms are not so easilyestablished. When it is not the job per se, butmore the variable working conditions thatnominate certain child work as ‘worst form ofchild labor’ there is room for interpretationon how to deal with it.The work that children perform on thesugarcane plantations of Leyte is exemplaryof this gray area between child labor and theworst forms. Children’s tasks vary fromweeding and planting to applying fertilizersand harvesting. Even though parents andoverseers try to protect children from themost hazardous work at the plantation –spraying pestici<strong>des</strong> – children are exposed toa number of hazards while at work. Heat,heavy work and long working hours, cuts andwounds from the equipment used and insectbites affect the children’s well being. On topof this, the children risk pesticide poisoningby working in or near sprayed fields.However, the level of involvement and thesort of work they do varies along with thecane growing season.Very striking is the fact that most peopleinterviewed in this research agree thatchildren should not have to work, thatchildren should go to school and have time toplay, not hindered in their development byheavy and hazardous plantation work. Withthe exception of one or two interviewees whowere of the opinion that children do not workin agriculture apart from helping their ownparents, all involved – children, parents,government representatives, NGOs, theinterviewed plantation manager – wouldrather not see children work. The question iswhy child labor still persists if all theseplayers in the field want it to end?The answers given point out variousbarriers to the elimination of hazardous childlabor on the sugarcane plantations. Children’sforemost barrier consists of lack of moneyand the lack of power to go against theirfamily’s expectations of children helping theirparents. Parents mainly point out financialbarriers: when the children do not work, howwill we pay the educational costs, or even thedaily basic needs? Apart from this theyrecognize a lack of other employment optionsthat ties them – and their children – to thesugar plantations where the work is heavyand the pay is low. NGOs see a set of barriershindering the elimination of child labor,varying from children’s and parents’ attitu<strong>des</strong>and values (‘work is important to learnchildren discipline’) to landlords’ aim toincrease their profits, and to lack of politicalwill from the side of the government.The government in turn says its effortshave limited impact due to lack of manpowerfor law enforcement (as is the case with laborinspection), but also points to parents’ valuesas a huge barrier when it comes to workingchildren in agriculture. Contributing to thislast idea is the strong belief that child laborin agriculture comes down to children helpingtheir parents on the family plot. Limiting itsown influence to formal employer-employeerelationships, child labor in agriculture issomething that the government is involved into a very limited extent.Landowners and their subcontractors likethe kapatas claim that parents want theirchildren to work and that even if they wouldnot allow children to work, the parents wouldbe angry. Another barrier they identify ismoney for the families. Not hiring childrenwill leave the families behind in great povertyand with no opportunity to pay educationalcosts. Furthermore they state that theycannot increase adult workers’ wages becausehigher wages will raise the prices of21

commodities, thus making life expensive forthe workers.All these barriers are exemplary of thedilemmas that the actors in the child laborissueface. Looking at the laws in place in thePhilippines, it is hard to establish whichchildren working in the plantations areengaged in not only child labor, but also inone of the worst forms of child labor, andwhich are not. The hazards that childrenencounter while working vary a great dealalong with the number of hours a child worksand the task he or she performs. Sinceworking in the sugarcane plantations isseasonal, flexible and divers children move inand out of the category ‘worst forms’ fromweek to week. However, several of the foundhazards of plantation work clearly fall underthe definitions of hazardous work asindicated by both international standards andPhilippine law. Long hours, exposure to heatand heavy work indicate that at least somechildren in the plantations are engaged in aworst form of labor. But almost all childrenare exposed to chemicals during their work,no matter how many hours they work or whattask they do. Therefore working in thesugarcane plantations qualifies as one of theworst forms of child labor and it should beeliminated immediately. This is not to saythat children should be removed from thefield without further delay. A carefullyplanned set of measures involving all actorsshould make both the supply and the demandfor child labor disappear.Proposed actionEnding child labor in the sugarcane fields is aresponsibility of all people and institutionsinvolved. With a new child labor law in place,law enforcement is needed to attain the<strong>des</strong>ired results. This means that laborinspections should be carried out in the fieldson a regular basis. Employers who violate thelaw should be held accountable. Given thefact that most parents claim economicnecessity to be the reason for them to lettheir children work, penalizing parents forchild labor seems to be punishing them fortheir poverty. With the government slowlyrecognizing child labor on the sugarcaneplantations as one of the worst forms of childlabor in the country, children should beremoved from the production process. Thiscan however only take place with theprovision that their parents have enoughalternatives to pay for basic needs andeducation costs. The recognition of sugarcane as a sector where children are beingentrapped in a worst form of child laborshould not lead to international bans onPhilippine sugar. Measures like these will hitthe laborers in the plantation har<strong>des</strong>t,aggravating the poverty and the generalliving conditions of children on thehaciendas. However, lessening thedependency on the haciendas as the solesource of income and as the major politicalpower ruling the lives of farm workersprobably contributes to a better negotiatingposition. This in turn could create openingsfor them to lobby for better wages andbenefits, thus lowering the number ofchildren that have to work to supplement thefamily’s income. Organizing parents andchildren so that they can voice their standtogether has proven to be effective in thisprocess. Furthermore, the hazardous effectsof plantation work should be furtherresearched since pestici<strong>des</strong> endanger thehealth and well being of plantation workersand other living on or near the plantation.The hazards of plantation work should bemade clear to parents and children, especiallywhen it comes to the chemical hazards.Awareness of the hazards can lead to betterprotection for the workers, to be provided bythe employers.The situation on the sugarcaneplantations in the Philippines is just oneexample of child labor in agriculture. Andeven though working in agriculture mightseem harmless, a closer look into the dailyrealities of working children learns that thechildren are confronted with more dangersthan the international community agreed totolerate. It is very likely that other seeminglytolerable forms of child work contain hiddenhazards as well. However, more research intothe exact dangers and effects of working onthe health and development of children isnecessary in each sector of work before stepscan be taken to eliminate hazardous childlabor.22

Annex 1: LiteratureAlbada, Fernando T., Leonardo Lanzona and Ronald Tamangan (retrieved 2004)A Review of Literature of Child Labor in the PhilippinesManila: Ateneo de Manila UniversityRetrieved July 12, 2004 fromhttp://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/dpnet/documents/review%20of%20related%20literature.pdfApit, Alejandro (2002)Child Labor in the Sugar Plantations: A Cursory AssessmentManila: Bureau of Women and Young Workers – DOLEDepartment of Agriculture (2004)BackgroundRetrieved July 23, 2004 from http://www.da.gov.ph/about/profile.htmFlores-Oebanda, Cecilia (2004)‘Q&A on Child Labour : A New Law, a Stronger Whip ?’ Footprints Volume VI Issue I, April 2004 pp.19-21.New Delhi: Global March Against Child LabourGarcia-Dungo, Nanette (1994)Post-crisis Development in the Sugar Hacienda and the Participation of Women in the Labor Force :The Case of Negros in: Herrin, Alejandro N. (ed.) Population, Human Resources & Development (pp. 976-989). Quezon City: University of the Philippines.ILO (2002)A Future without Child LabourGeneva: ILOKishi, M., N Hirschhorn, M Djajadisastra, LN Satterlee, S Strowman, R Dilts (1995)‘Relationship of pesticide spraying to signs and symptoms in Indonesian farmers’ in: ScandinavianJournal of Work, Environment and Health 1995; 21: 124-33.Lieten, George Kristoffel (2003)Kinderarbeid: Prangende vragen en contouren voor onderzoek.Amsterdam: Amsterdam University PressMyers, William E. (2001)‘Valuing diverse approaches to child labor’ In Lieten, Kristoffel & Ben White (eds) 2001 Child Labour:Policy Options (pp. 27-48)Amsterdam: AksantNSO – ILO/IPEC (2003)2001 Survey on Children 5-17 Years OldManila: ILORollolazo, Mildred G. & Luisa C. Logan (retrieved 2004)An In-Depth Study on the Situation of Child Labor in the Agricultural SectorManila: Department of Labor and EmploymentUNICEF (2003)The State of the World’s Children 2004New York: UNICEF25

Vries, Saul de (2001)Child Labor in Agriculture : Causes, Condition and Consequences. The Case of Child Laborers in Sta. Fe andOrmoc, Leyte.Manila: Institute of Labor StudiesOther relevant documents :ILO C182 Worst forms of child labour conventionUN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN CRC), 1989Philippine Republic Act 7610 and Republic Act 9231Newspaper articles:Jaarlijks 2 miljoen doden op het werk (April 29, 2004) Het Parool26

Annex 2: List of interviewsLeyteOrmoc ECLIPSE staff 17 May 2004Ormoc Alex Apit, KDF 19 May 2004Barangay Talisayan (Albuera) 9 parents 18 May 20044 childrenBarangay Patag (Ormoc) Field visit 18 May 2004Barangay Sumangga (Ormoc) 7 parents 18 May 200417 childrenBarangay Masarayao (Kananga) 13 parents 19 May 200411 childrenBarangay Valencia 1 Field visit 19 May 2004Barangay Valencia 2 (sitio Laray) 39 children 19 May 2004SupervisorOrmoc City 3 medical staff 20 May 2004Ormoc City Plantation owner 20 May 2004MindanaoMagsaysay Plantation owner 21 May 20044 parents6 childrenBarangay Luayon (Makilala) Plantation owner 22 May 2004Barangay captain5 parents7 childrenBarangay Malalag Cogon 9 parents 22 May 2004(sitio Kitagan)24 children (not working)4 working childrenManilaDr. Romeo Quijano, toxicologist University of the Philippines 25 May 2004Staff members (6) Occupational Health and Safety Center (DOLE) 27 May 2004Mrs. Soriano, director Institute of Labor Studies (DOLE) 31 May 2004Atty. E. Anaya, chief Bureau of Working Conditions- Inspections (DOLE) 31 May 2004Mr. Sabularse, deputy executive director Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority 1 June 2004Mr. Alex Apit, Kamalayan Development Foundation 2 June 200427