Amsterdam 2040

Amsterdam 2040

Amsterdam 2040

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

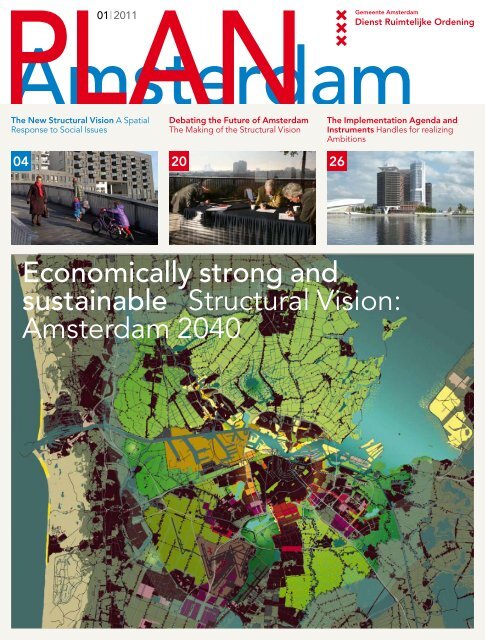

PLAN01 | 2011<strong>Amsterdam</strong>The New Structural Vision A SpatialResponse to Social IssuesDebating the Future of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>The Making of the Structural VisionThe Implementation Agenda andInstruments Handles for realizingAmbitions0420 26Economically strong andsustainable Structural Vision:<strong>Amsterdam</strong> <strong>2040</strong>

infographic Schematicrendering of the four majorthrusts described in theStructural Vision.map The ideal public transportnetwork post 2030.Map: DROexisting rail networkexisting HQPTconnectionsnew HQPT connectionstransfer station1 RER rapid-transit optionusing existing track2 East/West metro lineoptionThis edition’s authors:Conny LauwersBarbara PonteynKoos van ZanenRolling out the city centre Waterfront developments The southern flank Metropolitan landscape

A visionary scenario forthe future, a framework ofanalysis for todayCreditsPLAN <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is published bythe Department of Physical Planning(Dienst Ruimtelijke Ordening, or DRO)and provides information about spatialdevelopments in the city and across theregion in eight thematic issues per year.The DRO is one of the City of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’scentralized services and ensuresthe cohesive spatial development ofcity and region.The DRO is a member of the City of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s Development Alliance,a platform in which it collaboratesintensively with the departments ofInfrastructure, Traffic and Transport andof Economic Affairs, the <strong>Amsterdam</strong>Development Corporation, the ProjectManagement Bureau and the EngineeringBureau.Editing and coordinationKarin BorstDesignBeukers Scholma, HaarlemMain cover image/mapsDRO, Wouter van der Veur, Joris Vos,Bart de Vries, unless stated otherwiseotherwiseTranslationAndrew MayLithography and printingZwaan Printmedia, WormerveerThis publication has been prepared withthe greatest possible care. The DROcannot, however, accept any liability forthe correctness and completeness of theinformation it contains. In the event ofcredits for visual materials being incorrector if you have any other questions,please contact the editors: planamsterdam@dro.amsterdam.nlortel. +31 (0)20 552 7765. You can requesta free subscription by sending an e-mailto planamsterdam@dro.amsterdam.nl.Volume 17, no. 1, March 2011The magazine can also be downloadedfromwww.dro.amsterdam.nlThis edition of Plan <strong>Amsterdam</strong> isavailable in Dutch as well.The Structural Vision is a framework of analysis forspatial plans and provides the basis for setting thecity’s investment agendas, but first and foremost theStructural Vision is a visionary scenario for the future.In the Structural Vision, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> City Council setsout its ambitions for the period 2010 to <strong>2040</strong>.<strong>Amsterdam</strong> has deliberately opted for densificationof the city centre. The city has not chosen for growthby increasing its surface area but for intensificationof the existing urban territory and for transformationof business zones. By building 70,000 new dwellingswith accompanying amenities within the city’s existingboundaries we can expand the city centre milieu thatmakes the city so attractive. That is only feasible if wesimultaneously invest in the public space, public transportand greenery. People want to live in <strong>Amsterdam</strong>because of its combination of metropolitan bustle andlarge expanses of greenery within a short distance ofeach other. That is our strength, with which we draw inresidents and business enterprises.In the Structural Vision, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> emphaticallylooks beyond its borders. Problems, challenges andopportunities present themselves on the scale of the<strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area, so the Vision Mapcovers the whole territory between Zandvoort, Purmerend,Almere and Haarlemmermeer. This is the regionthat must operate as an economically robust entity onthe European and international stage, in order to beable to compete with, for example, the Ruhr Area.<strong>Amsterdam</strong> is the core city within this region and itsshowpiece.During the Structural Vision’s formulation, as manypeople and organizations as possible were encouragedto share their thoughts, using such means asthe internet campaign and the extended series ofchallenging public discussions. All the municipaldepartments concerned with spatial developmentcontributed to the definitive version of the document,making this vision a product that can truly be saidto belong to the whole city.The Structural Vision outlines the ambition for the longterm, which is why the vision must be continuouslyreadjusted in the light of current events, such as theeconomic crisis. Or, indeed, quite the contrary: inturbulent times, the vision for the future must providea framework of analysis to determine the plans thatought to be executed and those that are of secondaryimportance. The vision for the future should not beswayed by the issues of the day; it must map out howwe respond to them. Only then can <strong>Amsterdam</strong>become both economically strong and sustainable.Maarten van PoelgeestAlderman for Spatial Planning01 | 201103

The NewStructural Visionby Koos van Zanen k.van.zanen@dro.amsterdam.nlA spatial response tosocial issuesThe complexity of urban development means itis no longer possible to make do with blueprintplanning; ‘certainties’ that stem from them havelong been lacking in credibility. The <strong>Amsterdam</strong>Structural Vision must seduce and convince witha coherent narrative, a story in which the socialbenefit of spatial interventions is explained andjustified in terms that are as clear as crystal.The ‘Structural Vision: <strong>Amsterdam</strong> <strong>2040</strong>’ carriesforward the city’s long tradition of spatial structuralplanning, yet on important points the new StructuralVision diverges from previous structural plans, bothin substance and in form. The emphasis has shiftedto the vision for the city, while the spatial elaboration,in policy and regulations, primarily plays a complementaryrole.Spatial plans usually excel in their indication of whatmust happen and where, but spatial ambitions are notan end in themselves; they emanate from social needsand concerns. In the Structural Vision the interventionsare constantly subjected to questions, such as ‘Butwhy ...?’ and ‘Then how ...?’ Breadth of support makesor breaks a structural vision; if it were a paper tiger itwould soon disappear into a bottom drawer, and thatis hardly the intention.The city-dweller and the everyday environmentare keyIn the lead-up to the Structural Vision, the argumentsfor the spatial ambitions were laid down in two04PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

1 A bridge leading to ‘De Kas’restaurant in Park Frankendael,with the high-rise cluster nearthe Amstel Station in the background.Photo: Edwin van Eis‘Breadth of support makes or breaks astructural vision; if it were a paper tigerit would soon disappear into a bottomdrawer, and that is hardly the intention.’1documents: a ‘Memorandum of Starting Points’(Vertrekpuntennotitie) and ‘The Pillars’ (De Pijlers).The Structural Vision’s subtitle and motto – ‘<strong>Amsterdam</strong>:Economically strong and sustainable’ – is thebriefest possible encapsulation of these documents.By focusing on the economy and sustainability,<strong>Amsterdam</strong> can continue developing into an attractivemetropolis where people will also be able to reside,work and spend leisure time comfortably in <strong>2040</strong>.The city-dwellers and their everyday environmenttherefore take centre stage in the Structural Vision.Decline and growthAfter a long period of suburbanization which beganin the late 1980s, cities around the world have onceagain become popular and have been growing again.The countryside, by contrast, is faced with shrinkingpopulations. By and large, the further away from thecity, the more marked the decline. The countrysideof the former East Germany is emptying rapidly, whileBerlin is growing. In the Netherlands there is alreadya considerable decline in the country’s periphery,for example in Zeeland, South Limburg and EastGroningen, while <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is growing.It is hardly, for that matter, as if every city can boastthat it is growing. Besides the dividing line betweencity and countryside there is another division runningbetween cities ‘that count’ and those that have fallenout of favour. <strong>Amsterdam</strong> can count itself amongthe former category. The spatial development of the<strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area is to a large extentdetermined by this phenomenon of growth andcontraction and by the increasingly knowledge-driveneconomy that underpins this. <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is expectingan additional 100,000 to 150,000 inhabitants betweennow and <strong>2040</strong>.>01 | 201105

2 Buildings at the Kastanjepleinin <strong>Amsterdam</strong>-East, that arepopular with the modern cityresidentbecause of their specificcharacterand experientialvalue.Photo: Koos van Zanen‘Clean air, properties full of character and anattractive, green public space are all aspectswith which the city can secure the loyalty ofpeople and businesses.’2Economically strong and sustainableThere is a broadly shared view that <strong>Amsterdam</strong> mustposition itself robustly in the changing economic worldorder. Maintaining the welfare and prosperity of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s residents is paramount. The startingpoints for <strong>Amsterdam</strong> are favourable. Major cities arein any case faring well in an economy that is becomingincreasingly reliant on knowledge, but by no meansare all large cities capitalizing on the knowledgeeconomy: people are drawn to cities where life isgood. <strong>Amsterdam</strong> attracts people with its freethinkingimage, its historical city centre, the abundanceof amenities, the many economic opportunities,the water and the greenery. <strong>Amsterdam</strong> boasts adiverse and relatively young population, whichincreases its magnetic pull even further. Scores ofenterprises are establishing operations in <strong>Amsterdam</strong>because they are heavily dependent on the supplyof highly educated professionals – the human capital.The quality of life in the city has thus become animportant economic factor. All in all, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> holdsthe trump cards to remain economically robust.In order to actually bring these trump cards into play,<strong>Amsterdam</strong> must nevertheless continue to work hardon the quality of the living environment in the city.This primarily revolves around sustainability, in all itsfacets. The term ‘sustainable’ is usually associated withclimatological and environmental factors and that iscertainly the case in the Structural Vision, but sustainabilityis also relevant to other matters. A public spacewhich has a high-quality design and use of materialswill provide you with more pleasure and will be moredurable. Many neighbourhoods and buildings that aretechnically speaking out of date prove to be of greatsignificance for the city. Because of their specificcharacter, experiential value and adaptability they areextraordinarily popular with ‘the modern urbanite’.Properties and neighbourhoods from a distant pastcan in that sense be termed ‘sustainable’.Yet the essence of sustainability still involves theenvironment: in order to be a sustainable city we mustbe prepared for climate change: the air, soil and watermust become cleaner; the city will be rendered quieterand more energy-efficient. <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is thereforeswitching to sustainable energy sources and land willbe used more intensively.Economic development and sustainability have formany years no longer been regarded as each other’scounterpoles, but quite the contrary: they are increasinglybecoming extensions of one another. Clean air,properties full of character and an attractive, greenpublic space are all aspects with which the city cansecure the loyalty of people and businesses. Investingin sustainability is therefore tantamount to investingin the economy.The core city of the metropolitan areaTo quote the axiomatic ambition of the StructuralVision, ‘<strong>Amsterdam</strong> continues to develop further asthe core city of an internationally competitive andsustainable European metropolis.’ This has its roots inthe ‘Development Scenario for the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> MetropolitanArea in <strong>2040</strong>’ (Ontwikkelingsbeeld <strong>2040</strong> voorde Metropoolregio <strong>Amsterdam</strong>), in which the region’smunicipalities jointly stated the ambition to foster thegrowth of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> and environs into a metropolis.06PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

3 <strong>Amsterdam</strong> MetropolitanArea Development Scenario for<strong>2040</strong>.Map: Johan Karst (DRO)urban transformationuitbreiding stedelijkgebiedrural living environmentofficesbusiness parks/industrialzones@horticulture under glasscreative businessesknowledge hubScience Park/<strong>Amsterdam</strong>Internet Exchangemotorwaypark & rideregional railwayregional bus routehigh-speed trainferry - pedestrians/cyclistswaterwayexpansion of waterstoragecompartmentalization dike3The area in question, with 2.2 million inhabitants atpresent and a projected 2.5 million in <strong>2040</strong>, boaststhe scale and diversity that are necessary to remaincompetitive internationally. The North Sea beachesof Zandvoort, the family houses in Purmerend tothe north, Schiphol Airport and the open water ofthe IJmeer lake – all these are aspects that make<strong>Amsterdam</strong> a fully fledged metropolis and mean thatour city has become greater than the space within itsown boundaries: <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is the central city, thecore city, in the metropolitan area, and the StructuralVision: <strong>Amsterdam</strong> <strong>2040</strong> has been written from thisperspective.Seven spatial tasksWhat does <strong>Amsterdam</strong> have to do in order to becomeeconomically strong and sustainable and fully able topull its weight in the metropolitan context? In short,to live up to the motto and ambition? The StructuralVision places the emphasis on seven spatial tasks thatare decisive for the Dutch capital’s developmentaldirection thrust:>01 | 201107

4 Structural Vision:<strong>Amsterdam</strong> <strong>2040</strong>Waterfrontlive/work mixwork/live mixworkprojects in planning stageor recently completedRoll-out of centrelive/work mixwork/live mixlimited qualitative impulsefor major streets andsquaresqualitative impulse formajor streetsqualitative impulse forsquaresFormer naval basequalitative impulse for acity parkSouthern flankZuidaslive/work mixwork/live mixworkprojects in planning stageor recently completedMetropolitan landscape➀ Amstel Wedge➁ <strong>Amsterdam</strong>se Bos Wedge➂ Gardens of West➃➄➅➆➇Bretten ZoneZaan WedgeWaterlandDiemen WedgeIJmeer WedgeGeneralaboveground expansion ofmotorway capacityunderground expansion ofmotorway capacityhigh-speed railway lineaboveground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)underground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)international publictransport hub

main public transport hubsecondary public transporthub1 Schiphol/Almere Regiorailoption2 East/West metro lineoptionnew ferry linkunderground connection**P+R facilitysea lock2nd ocean liner terminaltemporary berths forinland shippingintensification of RAIprecinctshigh-class retail areaintensification of porturban support enterprisesqualitative impulse forborough centremarinapossible zone for portexpansionA/Bwater- or groundwaterrelatedproject2nd Schiphol Airportterminaloption for OlympicGames sitestudy area*regional cycle routeDefence Line of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>beachmetropolitan placerecreational programmeproposed naturedevelopmentwaterside developmentqualitative impulse for acity/wedge transitionSports AxisCompass Island andcycle bridge* For the Port-City study areathis map presents Scenario 3,with the exception of Buiksloterham.Future studies could resultin adaptations anywhere in thePort-City study area.Potential developments on thesouthern shores of the Gaasperplaslake were investigated in the‘Gaasperdam Reconnaissance’.** If the Port-City plans revealthat a connection is necessary,then this will be realized as atunnel.03 | 2010 9

‘A region that wants to function as a metropoliscannot do this without fast, frequent andcomfortable public transport on the regionalscale.’1 DensifyMore intensive use of the space in the city will makeit possible to accommodate many more people andbusinesses. This increases the customer base foramenities, which makes it possible to manage energyand transportation more efficiently and removesthe need to infringe upon the landscape. In concreteterms it means that an additional 70,000 dwellingswill be realized between now and <strong>2040</strong>, with thecorresponding amenities such as schools, shops andsports facilities. These amenities include servicesand maintenance, enterprises such as plumbers orgarages, though this kind of business activity isincreasingly being elbowed out from the area withinthe A10 orbital motorway. The Structural Visionincludes measures to retain such enterprises withinthe ringroad.The business parks within the city and the portarea will also be used more intensively: more productivefloor space and jobs per hectare. In addition,more high-rise development will be employed in<strong>Amsterdam</strong>, for example along the A10 ringroad andnear public transport hubs. There will also be effortsto find space below ground.2 TransformAs a component of densification, various monofunctionalbusiness parks will be transformed intoareas with an urban mix of residential and businessfunctions, in which the promising knowledge-intensivesectors will play an ever greater role. The primecandidates for this are the industrial sites alongsidethe IJ waterway. The greatest transformation task isthe Port-City project – the section of the port complexthat lies within the A10 ringroad. After 2030 it willbe possible to realize between 13,000 and 19,000dwellings there, mixed with businesses and amenities.3 Public transport on the regional scaleA region that wants to function as a metropolis cannotdo this without fast, frequent and comfortable publictransport on the regional scale; people must be ableto travel swiftly and without problems from Zaandamto Amstelveen or from Schiphol Airport to Almere,by means of regional trains, metro or rapid busconnections. At the moment a number of importantlinks in this regional public transport system arelacking. In the period through to <strong>2040</strong> the necessary‘network-wide leap’ must be achieved, including theextension of the metro’s orbital line into <strong>Amsterdam</strong>-North, the linking of the Westpoort harbour complexwith Schiphol Airport via a dedicated bus lane andthe upgrading of the Amstelveen Line into a fullyfledged metro service. In addition, a seamless transferbetween car and public transport will become possibleat a greater number of points than is currently thecase, by means of the creation of additional P+Rfacilities around the A10 ringroad and in the region,as well as other measures.4 High-quality layout of public spaceThe quality of life in the city is becoming increasinglyimportant, and along with this the layout and the useof the public domain. Within the A10 ringroad inparticular, the pressure on public space is great.<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s streets, squares and waterside embankmentsmust therefore meet high design standards intheir layout. More space will be set aside for cyclistsand pedestrians, which sometimes means less spacefor motorized traffic, though this does not herald thedisappearance of cars from the city. The major streets,those thoroughfares that function as ‘high streets’,where the majority of amenities are concentratedand where there is usually plenty of passing traffic,such as the Bilderdijkstraat, the Middenweg and theBeethovenstraat, deserve special attention. The socialatmosphere in the major streets will be furtherimproved by increasing the quality and diversity of theshops and food services and by refurbishing edificesand street-level frontages.5 Invest in the recreational use of green spaceand waterThe use of the green spaces and water in and aroundthe city is increasing and fulfils an increasinglyimportant role in the welfare of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’sinhabitants and as a precondition for businesses toestablish themselves here. It has therefore become animportant economic factor. Besides being attractive,the greenery and water must also be accessible and10PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

y Wouter van der Veurw.vanderveur@dro.amsterdam.nlThe maps tellthe storya ‘Plan Map’ of the StructuralPlan 1985.b ‘Plan Map’ of the StructuralPlan 1996.c ‘Vision Map’ of the StructuralVision 2011.On the cover of the Structural Vision there is amap of the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area inthe year <strong>2040</strong>. This map stands out in the seriesof maps from the structural plans of previousdecades. It is colourful and lively, and bycomparison with its predecessors looks slightlyless clinical. What are the key differences?The most striking difference is undoubtedly theframing. While the maps in previous structuralplans were exclusively focused on <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’smunicipal territory, the new Structural Vision mapis about the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area.This new outlook on <strong>Amsterdam</strong> as the core city ofthe much larger metropolitan region results in aslight tilting of the Structural Vision’s maps, so thatall the municipalities are properly in the picture.This broadening of the outlook is not the onlything that has changed. The most important mapin previous structural plans was always the ‘PlanMap’, in which <strong>Amsterdam</strong> was depicted in largecoloured panels that indicated the functions of thevarious areas. The zoning plans of city boroughswere appraised against that plan map. The mostimportant map in the new Structural Vision isthe vision map. Instead of large panels it usessubtle shadings that indicate the most importantdevelopmental thrusts in the metropolitan area.The map dovetails with the new philosophy ofthe Structural Vision and tells a story. The map isthe composite representation of the four thrusts:the ‘rolling out’ of the city centre, the renewedinterest in the waterfront, the economic dynamismof the southern flank and the increasinglyinterwoven urban and metropolitan landscapes.The vision map tells at a single glance where thedynamism is likely be highest over the comingdecades. Where possible, the narrative of theStructural Vision is illustrated with many details,such as the development of major streets orqualitative impulses in public spaces.Another change in course compared to previousstructural plans concerns the role of maps in theStructural Vision’s development. Urban plannersand designers worked on the vision’s maps fromday one, never approaching the task from a singlesectoral perspective or an isolated issue butconsistently based on an integral vision for the cityand the metropolis. The maps were honed andpolished from the very start. This means that themaps do not illustrate just the final conclusionof the discussions about the city’s future, buthave chiefly served as guidance throughout theprocess. Discussions were focused more sharplyby showing where strengths lie in maps, whichalso revealed where there are bottlenecks orwhere conflicts arise.The City Council ratified the Structural Visionin February 2011, so the vision map can now beregarded as an inspiring beacon for the future.The earlier structural plans were primarily instrumentsof verification and the accompanying planmaps served as a benchmark for assessment, butthe vision map serves a totally different purpose:to kindle enthusiasm and stimulate by outlining anattractive vision of the future.a b cusable for recreational purposes, which are aspects inwhich they sometimes falls short. The improvement isoften a question of fairly minimal spatial interventions,such as the laying of missing links in the recreationalcycle network, as on the route between <strong>Amsterdam</strong>and Muiden, or opening a teahouse in a park.This could, for example, augment the quality of theRembrandtpark, the Vliegenbos woodland area, theFlevopark and the environs of the Sloterplas lake.Extra marinas are planned on the IJ waterway forrecreational cruising and the sailing possibilities for‘sloops’ in and around the city will be expanded.6 Converting to sustainable energyAt some point fossil fuels will be exhausted. The citymust be ready for the post-fossil fuel era. <strong>Amsterdam</strong>must therefore become more energy-efficient. A bigstep can be made by rendering the existing housing>01 | 201111

5 Densification: pedestrians onthe Han Lammers Bridge leadingto the recently developedWestern Dock Island (primarilyresidential).Photo: Edwin van Eis6 Transformation: the cranewayat the former NDSM dry dockwas transformed into a multitenantoffice building in 2007.Photo: Edwin van Eis7 Public transport on the regionalscale: the bus station at theBijlmer ArenA station, a transfernode for various modes of transport.Photo: Doriann Kransberg8 High-quality design of publicspace: the Rembrandtplein,which was reprofiled in 2010.Photo: Edwin van Eis9 Recreational use of greenspace and water: a watersportsassociation’s sailing dinghies onthe Sloterplas lake.Photo: Edwin van Eis10 The switch to sustainableenergy: wind turbines,oil depots and the typical cloudfilledskies of Holland in the Portof <strong>Amsterdam</strong>Photo: Edwin van Eis11 Entrance to the OlympicStadium at the Stadionplein.Photo: Edwin van Eis512PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>67

8 9101103 | 2010 13

12/13 Port-City: Two scenariosfor the transformation of theport area within the A10 ringroad.workwork/live mixlive/work mixqualitative impulse for acity park- - - - underground connectionindicative route for HQPT12 13stock more energy-efficient, and <strong>Amsterdam</strong> has alsochosen to generate a large proportion of its energyneeds itself, which includes the collection of solarenergy on rooftops, the construction of a closedheat-transfer system in order to be able to transportresidual heat, and the installation of wind turbines.<strong>Amsterdam</strong> will also be investing in sustainable energygeneration throughout the region.7 Olympic Games, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> 2028The Netherlands has the ambition to host the OlympicGames in 2028. The games are a national affair inwhich <strong>Amsterdam</strong> can serve as the logo and canprovide space for the nerve centre of the games, inthe form of the Olympic Stadium, the Olympic Villageand swimming accommodation. There are twocandidate locations for this: the Waterfront (the banksof the IJ) and Zuidas.The four major thrustsThe seven spatial tasks are not autonomous, butare drawn along in the wake of what the StructuralVision terms ‘the four major thrusts’. These are robustdevelopmental trends which can be observed inlarge sections of the city and even outside it. Thesedevelopmental trends can be decisive for the successor failure of an actual plan or project.The crux is ‘metropolitan logic’: the right things in theright place. The ‘right’ plans hitch a ride with one ormore thrusts, while ‘illogical’ plans battle against thecurrent. Conversely, the major thrusts are actualizedand reinforced by concrete plans and projects.The four major thrusts are:1 the roll-out of the city centre;2 the interweaving of the metropolitan landscapeand the city;3 the rediscovery of the waterfront;4 the internationalization of the city’s southern flank.1 Rolling out the city centreOne of the spatial trends is that <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s metropolitancentre is being used more and more intensivelyand is expanding ever further. Almost all the neighbourhoodswithin the A10 orbital motorway nowdisplay city-centre traits. Living within the ringroad ishighly desirable, the parks in this area are attractingmore and more visitors, and for creative and knowledge-basedenterprises this area is the ideal businesslocation. The abundance and variety of amenities inthe northern part of the Pijp and Old-West neighbourhoodscan pretty much hold their own against those inthe historical inner city. Several neighbourhoods thatwere out of favour not so long ago are now beingswept onwards and upwards in this ‘roll-out of the citycentre’. For example, the Bos en Lommer and Indische>14PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

14 Vision for the roll-out of thecity centre in <strong>2040</strong>Roll-out of centrelive/work mixwork/live mixlimited qualitative impulsefor major streets/squaresqualitative impulse formajor streetsqualitative impulse forsquaresFormer naval basemetropolitan parkqualitative impulse for acity parkGeneralaboveground expansion ofmotorway capacityunderground expansion ofmotorway capacityaboveground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)underground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)international publictransport hubmain public transport hubsecondary public transporthub1 Schiphol/Almere Regiorailoption2 East/West metro lineoptionnew ferry linkA/Bunderground connection**P+R facility2nd ocean liner terminaltemporary berths forinland shippingintensification of RAIprecinctshigh-class retail areaurban support enterprisesoption for OlympicGames sitestudy area*metropolitan placerecreational programmequalitative impulse for acity/wedge transitionSports AxisCompass Island* / ** See notes on page 09.1401 | 201115

15 Vision for the metropolitanlandscape in <strong>2040</strong>Metropolitan landscape➀ Amstel Wedge➁ <strong>Amsterdam</strong>se Bos Wedge➂ Gardens of West➃ Bretten Zone➄ Zaan Wedge➅ Waterland➆ Diemen Wedge➇ IJmeer WedgeGeneralregional cycle routewater- or groundwaterrelatedprojectDefence Line of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>beachmetropolitan placerecreational programmeproposed naturedevelopmentwaterside developmentqualitative impulse for acity/wedge transition1516 PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

16 Vision for the southern flankin <strong>2040</strong>Southern flankZuidaslive/work mixwork/live mixworkprojects in planning stageor recently completedmetropolitan parkqualitative impulse for acity parkGeneralaboveground expansion ofmotorway capacityunderground expansion ofmotorway capacityhigh-speed railway lineaboveground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)underground HQPT (bus/tram/metro)international publictransport hubmain public transport hubsecondary public transporthub1 Schiphol/Almere Regiorailoption2 East/West metro lineoptionP+R facilityintensification of RAIprecinctshigh-class retail areaurban support enterprisesA/Bqualitative impulse forborough centre2nd Schiphol Airportterminaloption for OlympicGames sitestudy area*regional cycle routeDefence Line of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>metropolitan placerecreational programmequalitative impulse for acity/wedge transitionSports Axis* Potential developments onthe southern shores of the Gaasperplaslake are being studiedas part of the ‘GaasperdamReconnaissance’.1601 | 201117

17 Vision for the waterfrontin <strong>2040</strong>Waterfrontlive/work mixwork/live mixworkprojects in planning stageor recently completedqualitative impulse for acity parkFormer naval baseGeneralindicative route foraboveground HQPTindicative route for undergroundHQPTinternational publictransport hubmain public transport hubsecondary public transporthubnew ferry linkunderground connection**P+R facilitysea lock2nd ocean liner terminaltemporary berths forinland shippingintensification of porturban support enterprisesqualitative impulse forborough centremarinapossible zone for portexpansionA/Boption for OlympicGames sitestudy area*regional cycle routebeachmetropolitan placerecreational programmeproposed naturedevelopmentwaterside developmentCompass Island andcycle bridge* / ** See notes on page 09.1718Buurt neighbourhoods are now home to new trendycafés and restaurants that attract a clientele fromacross the city.This ‘major thrust’ emanates from the enormousmagnetism of the heart of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> for countlesspeople, enterprises and institutions. However, thescarcity of space means that people are always forcedto search a little further out: first in the 19th-centurydistricts adjacent to the city centre, then in the surroundingbelt of development realized in the 1920s to1940s, and now the ‘city-centre milieu’ is spreadingout across the IJ waterway and towards Zuidas.2 Interweaving the metropolitan landscapeand the city<strong>Amsterdam</strong> is surrounded by a highly diverse landscape,the so-called metropolitan landscape. Thispenetrates far into the city in the form of wedgesof greenery, which increase the city’s appeal andpresents <strong>Amsterdam</strong> with the possibility of densifyingwithin the existing urban footprint while remainingliveable. This means that the city is heavily dependenton its immediate surroundings. Well-heeled <strong>Amsterdam</strong>residents already sought their recreation in thePLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>circumjacent environs during the Dutch Golden Age.Country estates sprung up in all directions: to the west(along the IJ waterway), south (alongside the RiverAmstel), east (along the River Vecht) and north (in theBeemster Polder). That landscape was incorporatedinto Cornelis van Eesteren’s 1935 General ExtensionPlan (Algemeen Uitbreidingsplan, or AUP) as greenwedges penetrating into the expanding city. The landscapewas partly a given (the River Amstel and the IJinlet) and partly constructed (the manmade <strong>Amsterdam</strong>seBos woodland park and the Sloterplas lake).The ambition of the Structural Vision is to keep thegreen wedges green, improve their accessibility andmake them more attractive for recreational use.3 The rediscovery of the waterfrontThe water in and around the city is of one of thequalities that distinguishes <strong>Amsterdam</strong> from mostother metropolises. The awareness that this is ahuge asset for the city will only grow stronger. The IJwaterway and the IJmeer expanse of water have aparticularly high experiential value and offer manypossibilities for recreation. The waterfronts andshorelines offer countless opportunities for urban

01 | 2011development, especially in the obsolete port precinctsand industrial zones.<strong>Amsterdam</strong> and the Zaan region can be physicallyinterconnected via the IJ waterfront and the banks ofthe River Zaan. With the development of the secondphase of IJburg and the Zeeburger Island, <strong>Amsterdam</strong>will finally gain a new ‘city lobe’, comparable with<strong>Amsterdam</strong>-Southeast (the Bijlmer) and Buitenveldert/Amstelveen. Due to all these developments, the IJwaterway is becoming increasingly central within themetropolitan footprint, while it continues to rankamong the busiest inland shipping routes in theNetherlands. A delicate task is the upgrading of thenatural qualities of the IJmeer, in combination withwatersports and coastal recreation.4 Internationalization of the southern flank<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s southern flank is a succession of massiveprojects: the expansion of Schiphol Airport, thedevelopment of Zuidas and the intensification of theresidential and business areas in <strong>Amsterdam</strong>-Southeast.Station-Zuid, at the heart of Zuidas, will becomeone of the most important public transport hubs in theNetherlands. The main driver of these developmentsis the large bundle of infrastructure that links <strong>Amsterdam</strong>with the other municipalities in the Randstadconurbation, with the rest of the Netherlands, withEurope and, via Schiphol Airport, with the world.New initiatives such as the development of thecorridor between Schiphol Airport and Zuidas andthe further urbanization of Buitenveldert are beingimplemented at a swift pace.<strong>Amsterdam</strong> is never completeDo we now have a structural vision that seduces andconvinces? Does it provide solid backing for concreteactual plans and projects? Does this vision allow sufficientdevelopmental leeway and does it simultaneouslygive direction and a firm footing? A city is nevercomplete, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> is never complete. The textof the Structural Vision has been finalized, but itsstrength should primarily be judged by its spirit ratherthan by the letter. The concrete spatial developmentsthat will characterize our city over the coming decadesshould be regarded as the ultimate proof.19

Debatingthe Future of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>by Barbara Ponteyn b.ponteyn@dro.amsterdam.nlThe Making ofthe StructuralVisionMore than ever before in <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’slong tradition of structural planning,the City Council wanted this StructuralVision to take shape in an open process.Citizens, businesses, organizations andother government bodies had to be giventhe opportunity to share their thoughtsand provide input throughout theprocess. The City Council had no desireto devise this vision on its own, seeingas it cannot realize the eventual outcomein isolation.The process of jointly devising a vision by consultationwas at least as important as the end product. Themaking of the structural vision took three years andconsisted of three phases: reconnaissance, integrationand ratification. Citizens and organizations wereinvolved in these phases in various ways. By contrastwith the previous structure plans, the formulation ofthe structural vision was managed as an integratedwhole – both bureaucratically and politically – withthe municipal departments involved in spatial mattersworking as a team and co-authoring the structuralvision. This brought the tasks facing the variousdisciplines into the equation.The great political engagement was terriblyimportant for the process. The coordinating alderman,Maarten van Poelgeest, was in attendance at a greatmany meetings and also entered into smaller-scalediscussions, with organizations such as the <strong>Amsterdam</strong>Centre for the Environment (Milieucentrum <strong>Amsterdam</strong>,or MCA), with students, allotment holders andthe citizens who participated in the public campaign.Reconnaissance: gathering expertiseand ideasDuring the first phase of the process (2008-2009) theemphasis was on the organization of the process anddetermining the important themes for the future ofthe city. To do this it was necessary to ‘gather’ theexpertise and ideas that are alive in the city, not only inorder to be working with the right information but alsoto arrive at a broadly shared outlook for the future.Citizens, the private sector, interest groups andplanning professionals were consulted in discussions,conferences and workshops. A ‘Memorandum ofStarting Points’ (Vertrekpuntennotitie) was drawnup prior to the dialogue, incorporating the basic120PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

y Barbara Ponteynb.ponteyn@dro.amsterdam.nlPlanMER1 Alderman Maarten vanPoelgeest discusses theMemorandum of Starting Pointswith planning experts.Photo: DRO2 The Memorandum of StartingPoints was approved by theCity Executive on 17 June 2008and was discussed by theCouncil Committee for UrbanPlanning, Land Use, WaterManagement and ICT on27 August 2008.3 ‘The Pillars’ were approvedby the City Executive on 14April 2009 and were discussedby the Council Committeefor Urban Planning, Land Use,Water Management and ICTon 6 May 2009.4 Getting down to work at a‘southwest-wards’ meeting heldon 29 October 2009.Photo: DROAn environmental impact report (planMER) isa mandatory component of the process of formulatinga structural vision. This report assessesthe environmental effects of the choices madein the Structural Vision.The planMER has had plenty of influence on theStructural Vision in various phases of the process.An expert meeting led to the four major thrusts inthe vision, for example. The planMER also madea significant contribution to one of the StructuralVision’s objectives, namely its highlighting ofsustainability. According to the committeeresponsible for the environmental impact report,the MER fulfils an exemplary function in theclimatological field. The planMER translatessustainability themes into indicators againstwhich the desired developmental directions aretested, such as ‘the amount of space that willbe reserved for the generation of sustainableenergy’.One outcome of the planMER was the heraldingof a Wind Vision in the Structural Vision. Anotherproduct that stems from the environmental reportis a mobility test, which provides insight into whichcombinations of infrastructure and spatial developmentsscore best. This is useful in complyingwith diverse viewpoints and provides input for thefine-tuning of the phasing of projects.VertrekpuntennotitieGesprek overde toekomstvan <strong>Amsterdam</strong>naar de structuurvisie 2010 - 2020voor de kernstad van de metropoolregioDe Pijlersvoor de ruimtelijkeontwikkelingvan <strong>Amsterdam</strong>4Notitie op weg naar de structuurvisie2/3principles, trends and developments that are decisivefor making choices in spatial development. Oneimportant guiding framework was the ‘DevelopmentScenario for the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area’(Ontwikkelingsbeeld Metropoolregio <strong>Amsterdam</strong>),with <strong>Amsterdam</strong> as the core city of an economicallyrobust metropolitan region.The metropolitan idea was already supportedby the administration and the body politic, but theoutside world was still insufficiently involved. It iscity residents, social organizations, businesspeople,project developers and government bodies whotogether make the metropolis; they shape the identityand appearance of their city. What are their ambitionsand wishes for <strong>Amsterdam</strong> in the context of theMetropolitan Area? During this phase the City Councilwanted to raise awareness and inspire people toaction. In the ‘–wards discussions’ the parties andstakeholders organized according to the points ofthe compass – including the relevant neighbouringmunicipalities – sat down at the conference table totalk about the city’s future. The participants valuedthis regional orientation and were conscious thatinterdependence on a regional scale is increasing.>01 | 2011 21

y Barbara Ponteynb.ponteyn@dro.amsterdam.nlThe ‘within 30 minutes’public campaigna The first round of consultationvia www.binnen30minuten.nl– ‘within 30 minutes’ – thepublic campaign that invited thepeople of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> to sharetheir ideas for the city of thefuture.b The launch of the campaignwas highly visible in the city(March-April 2009).Photo: Koos van Zanen5 Scale model of the ‘NieuweMeer, Global Awareness’ projectby Güller Güller architectureurbanism, which the bureaupresented during the ‘Free Stateof <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’ exhibition.Photo: Marjolein van VossenDuring the drafting of the Structural Vision,<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s inhabitants were presented with theopportunity to share their opinions about thefuture of their city by means of a large-scale publiccampaign. The campaign prompted people tothink about the future. Reactions were receivedfrom across the metropolitan area and sometimeseven from far beyond. The title of the campaignwas inspired by the fact that the city is bigger thanyou might think: it used to take half an hour totravel from the Central Station to the Muiderpoortgateway on the city’s eastern perimeter, butnowadays you can reach Zandvoort on the NorthSea coast or the city of Almere in Flevoland bytrain in those same 30 minutes. The websitewww.binnen30minuten.nl (‘within 30 minutes’)played a pivotal role. The online campaign wasclosely aligned with the phasing of the StructuralVision and encouraged the people of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>to continue sharing their thoughts. The reactionscould be read on the site immediately and byeveryone.It was clear that <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s residents andvisitors are keen that the green space in the citywill be improved in the future. More possibilitiesfor recreation, more cycle paths, fewer rules andmeasures to improve the city’s cleanliness andasafety were other themes in the campaign.The city’s continued growth and the attendantdensification was often appreciated, though highrisemust be inserted with due caution. A greaterdiversity of neighbourhood amenities rankedparticularly high on the wish-list of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’scitizens. A marginal note is that <strong>Amsterdam</strong> mustretain its human scale. Opinion is divided aboutthe prospect of hosting the Olympic Games.When formulating the Structural Vision, thecomments and heartfelt cries of the campaignparticipants were integrated wherever possible.The vision therefore assigns an important place toinvestment in the city parks and improving cycleroutes into the countryside surrounding the city.The decision to give all the spatial tasks a placebwithin the existing urban footprint, at least wherethat was possible, means that the majority ofamenities are within cycling distance.The fact that everything can be found in theproximity of people’s homes contributes to thefeeling that the city retains a human scale: it is nota sprawling city where you are forced to take thecar, but a city where amenities are still be foundaround the corner. A special policy was formulatedfor the integration of high-rise development, sothat there will be no unbridled growth in which thehuman scale is lost. These are just a few examplesof the citizens’ wishes that have been given theirrightful place in the vision. The public campaignproved to be an important gauge during theStructural Vision’s elaboration.5Integration into a well-balanced narrativeIn the second phase (2009-2010) the emphasis shiftedto the framing of a well-balanced narrative in which theambitions and the long-term outlook for the spatialdevelopment of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> within the MetropolitanArea was pivotal. The initial impetus was ‘The Pillars for<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s Spatial Development’ (De Pijlers voor deruimtelijke ontwikkeling van <strong>Amsterdam</strong>), a documentoutlining the ‘10 pillars’ which provided the foundationsfor the definitive structural vision. The documentdescribes the most important spatial tasks and issues.During the development of this document into a DraftStructural Vision, the stakeholders, adjacent municipalitiesand borough councils were once again invited toprovide input. <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s citizens were consulted viawww.binnen30minuten.nl (‘within 30 minutes’), a publiccampaign using the web and social media. The ‘FreeState of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’ (‘Vrijstaat <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’) exhibitionwas staged, with a public programme of narratives anddiscussions about the future of the city. This presentationemployed unorthodox methods to coax city-dwellersand visitors into thinking about urban developmentand speaking their minds. Phase two drew to a conclusionin January 2010 with the City Executive’s adoptionof the ‘Draft Structural Vision for <strong>Amsterdam</strong> in <strong>2040</strong>:Economically strong and sustainable’ (OntwerpStructuurvisie <strong>Amsterdam</strong> <strong>2040</strong>, Economisch sterk enduurzaam) along with the accompanying planMERenvironmental impact report.Ratification: Responding and moving theprocedure forwardDuring the third phase (2010), everyone was given12 weeks to voice opinions about the Draft StructuralVision and the planMER in a letter to the City Council,whether they were a city resident or an organization22 PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

‘The interconnection of variousparties and themes was centralto the production of the StructuralVision.’6 ‘About Tomorrow: Is 020ready for <strong>2040</strong>?’, a visual for theStructural Vision conference on21 April 2011.7 Public information meeting inthe Zuiderkerk on 25 February2010 at the start of public consultations.Foto: DROOver MorgenIs 020 klaar voor <strong>2040</strong>?21 april 2011 | Felix Meritis6 7from within or outside the city. This served as theformal public consultation. The great public interestand engagement was demonstrated by the 420 viewsthat were submitted. The Structural Vision’s projectmanagers also remained in full and frank discussionwith bodies such as the city’s borough councils duringthis phase. These discussions were intended as preparationfor the submission of opinions, which resultedin more sharply formulated viewpoints and thereforefacilitated their swift processing. The opinions wereanswered in a ‘Memorandum of Responses’ (Nota vanBeantwoording). This contributed to certain shifts inemphasis and the modification of dozens of points inthe Draft Structural Vision. One notable modification,in response to a large number of submitted opinions,was the re-routing of a planned road, which had untilthen been destined to cut through a complex of allotmentgardens in the Bretten Zone. This is subject to theconditions that this section of road will not be laid untilafter 2030 and will be realized in the form of a tunnel.The views were especially helpful in the refinement andcloser examination of several aspects, such as the moredetailed study of the Waterfront as a potential Olympicssite. This led to a variant that no longer presents anyproblems for the port-based businesses concerned.In October 2010, with the feedback from thepublic consultations in hand, the newly installed CityExecutive pointed the way forward to the definitiveproposal for the Structural Vision. During the ensuingdiscussions in the Council Committee for Development,Housing and the Climate, interested partiescould explain their standpoints in person once again.The Structural Vision was definitively ratified by the CityCouncil on 17 February 2011.A connecting roleThe interconnection of various parties and themeswas central to the production of the Structural Vision.The themes that were perceived as important byplanning experts, private parties, social groups and cityresidents have, as far as possible, been tracked down,analysed and forged into a logical whole. The stimulationof debate about the city’s future was integral tothis process. Everyone was involved at every stage inthe open planning process, which was fascinating andlabour-intensive but resulted in a broadly supportedvision.With the City Council’s ratification of the StructuralVision we are entering a new phase. Discussions withthe city and with stakeholders within and beyond<strong>Amsterdam</strong> will continue. An important milestone inthis regard is ‘About Tomorrow: Is 020 ready for <strong>2040</strong>?’(Over Morgen, is 020 klaar voor <strong>2040</strong>?), a conference setto take place on 21 April 2011. The topic of discussionwill be how we are going to join forces to implement theStructural Vision together. Thanks to the open processemployed, which includes the forthcoming conference,the likelihood of the ambitions in the Structural Visionbeing realized is increased considerably.01 | 201123

Four personalimpressionsStructuurv<strong>Amsterdam</strong>An integral narrative?Ronald Wiggers Department of Social Development (DMO)In front of me there is a hall full of inquisitive faces. As bestI can, I endeavour to explain the substance and principles ofthe Structural Vision to my colleagues from the Departmentof Social Development (Dienst Maatschappelijke Ontwikkeling,or DMO). My narrative prompts a throng of reactions:But how does combating poverty come into it? What aboutthe neighbourhood approach? How do you know what theworld will be like in <strong>2040</strong>? And where is the body of thoughtfrom the Social Structure Plan? None of these are questionsthat the Structural Vision answers directly.At the dawn of the 21st century, when we were in discussionwith the whole city about metropolitan dynamism, humancapital and a liveable environment, which resulted in awonderful document: the Social Structural Plan 2004-2015,with the subtitle ‘What drives <strong>Amsterdam</strong>?’ And the ideaback then was that we would never produce separate spatialand social structural visions again. The forthcoming StructuralVision would be a wholly integrated document.Economisen duurzaIs this Structural Vision that integral document? No, but it isperhaps an initial step. The maxim that ‘People make the city’is most prominent in the section about the vision and thesocial aspect of sustainability with room for greater flexibility,diversity and stakeholder responsibility is also distinctlypresent. It is just a shame that the human scale and sociospatialtasks, such as those for sports and education, haveoften been obscured again in the elaboration. Wouldn’t it bewonderful if we could also simply sketch in a new small-scalesports park, combined with education and childcare facilitiesas well as amenities for youngsters, on the Northern Banksof the IJ?The social vision for the city’s development calls for a spatialelaboration as well, and in my view that might have beenembodied more emphatically, but we will do that next time.A field of tension inseveral respectsFokko Kuik Department of Infrastructure, Transportand Traffic and Transport (Dienst Infrastructuur Verkeer enVervoer, or dIVV)It was an honour to be allowed to work together with colleaguesfrom other disciplines on the future of my own city.You gain a greater understanding, of each other’s standpointsand of the choices that simply have to be made ifthere are many interests struggling for precedence.At the same time I did not always feel that such a collaborativeprocess, in which everyone sits down around a tabletogether for each topic of discussion, necessarily leads to abalanced appraisal. Sometimes the alderman for spatialplanning opted for his own line, which diverged from theadvice of traffic experts. In and of itself it is, of course,perfectly legitimate that an alderman should set out hisown course.Something I am pleased with is that in the implementationsection it was decided to couple the pace of spatial developmentsto the associated transport infrastructure. Somethingthat pleased me less was that it upholds the long-term planto develop the Gooiseweg into an urban avenue, despite theobjections (in my opinion justified) to the transformation.One drawback is that it undermines two of the key principlesdescribed in the vision: first develop where there is alreadya good public transport access, and retain the importantcorridor function for motor traffic. The Gooiseweg isindispensable as a major arterial road that allows the citycentre to function as an economically strong entity.In general I perceive a field of tension between the toweringlonger-term ambitions of the Structural Vision and theincreasingly pessimistic short-term prospects, because of theeconomic crisis. For a vision peering into the distant futureone should, of course, never allow oneself to be guided bythe issues of the moment, but the chasm between ideal andreality has as a consequence grown pretty large.24 PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

Quality, time and moneyKeimpe Reitsma <strong>Amsterdam</strong> Development Corporation(Ontwikkelingsbedrijf <strong>Amsterdam</strong>, or OBA)The Structural Vision is first of all about ambitions andopening up broad panoramas. It goes without saying thatquality is of paramount importance, but at a given momentthe execution comes up for discussion, the matter of makingchoices. That is also a necessity, because the new SpatialPlanning Act (Wet ruimtelijke ordening, Wro) prescribes thatin the Structural Vision the municipalities must also indicatehow they expect to effect the policy’s implementation. That isa fine passage, which you could dwell upon for a long time,certainly the phrase ‘to effect implementation’. The questionis how you can bring about that materialization on the basisof your spatial ambitions. And for that we have found asimple but actually quite brilliant formula: it was decided to setout the realization of the Structural Vision along a timeline. Byopting for a phased realization in three consecutive decades,time has become the flexible factor and the ambitions andthe final outcome have been preserved intact. The motto isthat if it doesn’t materialize today, then it will tomorrow.isie<strong>2040</strong>When the financial crisis raised its head, it happened upona Structural Vision in the throes of development. What doesthis crisis mean for the Structural Vision? Relatively little inthe light of the above, but it did become obvious that theambitions for developing new housing over the first decadewere too high. Shifting the construction of 10,000 dwellingsfurther along the timeline resulted in the painting a more balancedpicture of the future without it affecting <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’sambition to realize 70,000 new dwellings. This was madepossible by the chosen arrangement by decade.But what about that other factor, the money, and doesn’tthat throw a spanner in the works? Something that becameincreasingly apparent during the drafting of the StructuralVision was that less money would be available for urbanprojects than in former times. Important sources of revenue,such as the sale of land for office developments and statesupport for housing construction, have dried up. Sometimesit seems as if there are no longer any funds whatsoever fornew projects, but this ignores the most important financialmainstay of urban developments: the ‘big-money’ demandfor more city. And for the time being that demand shall notbe drying up.ch sterkamThere will be a demand for more <strong>Amsterdam</strong> and more thanbefore this will have to generate the means to continuebuilding on <strong>Amsterdam</strong>. Capitalizing on that demand willtherefore be an important objective of new site-specificdevelopments. A passage such as ‘to implement’ then fallsinto place. You can then also deduce that the StructuralVision incorporates the necessary leeway, for which the fillingin will only become obvious in the long run. Those who arenot reassured by all of this might derive comfort from thewords of the Nobel laureate Ivo Andric: ‘The most terribleand most tragic of all human weaknesses is undoubtedly hiscomplete inability to see into the future, which stands in sharpcontrast with his many talents, his knowledge and his art.’Haarlem to <strong>Amsterdam</strong>and backMarc Hanou Project Manager, Structural Vision forNorth HollandFrom a legal perspective the earlier structural plans for<strong>Amsterdam</strong> were regional plans, for which <strong>Amsterdam</strong> hadreceived the mandate known as ‘freedom in policy’ from theProvince of North Holland. But that was in the days of the‘old’ Spatial Planning Act. In 2000, the City of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>and the Province of North Holland took the initiative toestablish a platform for the North Wing of the Randstad(Noordvleugel), with the aim of devising a shared vision forthe future in cooperation with the 30 or so municipalitiesacross the region. For the region it was an unprecedentedmodel of ‘governance’, though I wonder whether we knewwhat such a collaboration was called back then.In 2007, even before the introduction of the ‘new’ SpatialPlanning Act, a decision was taken to formulate theDevelopment Scenario for the North Wing of the Randstadin <strong>2040</strong> (Ontwikkelingsbeeld Noordvleugel <strong>2040</strong>), which wasmeant to serve as the point of departure for the formulationof all the structural visions in the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> MetropolitanArea. This Development Scenario was a vision for the futurewhich had been forged by means of an open, participativeand intensive collaboration among the government bodiesconcerned. Immediately after the ratification of this vision,the Province of North Holland began work on its StructuralVision. The preceding collaboration was well received,and had whet the appetite for more, so all North Holland’smunicipalities were invited – the City of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> and the<strong>Amsterdam</strong> City Region platform in particular – to participatein the ‘Structural Vision for North Holland’ project as fullmembers of the team.The involvement of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s Department of PhysicalPlanning and the City Region platform in the project team forthe Province of North Holland’s structural vision establisheda collaboration that fostered mutual trust and involved thesharing of content as well as weekly or even daily interchanges:different dishes were prepared using the sameingredients in everyone’s respective kitchens. This was aunique situation that produced two structural visions, eachof which does justice to the formulated point of departure inits own way, elaborating the essential points from the NorthWing Development Scenario for <strong>2040</strong> – the growth andprosperity of the metropolis, the city centre densification,measures for dealing with the changing climate, tacklingextra- and intra-regional accessibility and the use of themetropolitan landscapes – in different ways. Locally wherepossible and centrally where necessary, but always foundedon mutual trust and reciprocal effort.01 | 2011 25

The ImplementationAgenda andInstrumentsby Conny Lauwers c.lauwers@dro.amsterdam.nlHandles for realizingambitionsThe Structural Vision is not a book of pipedreams, but articulates the ambitionsof <strong>Amsterdam</strong> City Council, which seesopportunities for the city to grow andbecome stronger even in less prosperoustimes. Ambitions can, however, only befulfilled if they result in concrete plans, inthe awareness that it is impossible to doeverything everywhere all at once.It is necessary to phase, to organize and wherenecessary to adjust or rein in. These componentsof the Structural Vision are included in the implementationagenda for the coming decade and in the setof instruments.The implementation agendaThe implementation agenda sets out the urbancohesion of projects and the feasibility of ambitions.It is used as a basis to strike agreements with regardto the phasing and scale of projects. It makes adistinction between plans that can be realized overthe coming decade and those plans that only comeinto play thereafter. In the latter case it also concernsplans with a relatively long preparation time, as isoften the case with major infrastructure projects or therelocation of industrial activity. For the realization of allthese ambitions, the city and city boroughs are highlyinterdependent, given that for many projects it is thecity boroughs which turn the ideas into concrete plans.The reason for one development following on thetails of another is usually rooted in the nature of thosedevelopments. For example, it is preferable to lay outthe infrastructure first, followed by actual construction.The pace of restructuring and transformation is alsodependent on many factors, not least the prevailingeconomic circumstances. From a metropolitan perspectiveit is therefore sometimes necessary to prioritizethe transformation of one site before another, butfactors such as accessibility and availability of sites forrelocating industrial activity also play a part. The mixingof business activity with residential use is in certaincases only possible after the repositioning of environmentalcontours or taking noise-limiting measures.The Northern Banks of the IJ as a modelThe process of transformation along the NorthernBanks of the IJ is in full swing, with extensivelyemployed business premises slowly but surely makingway for a mix of housing and smaller-scale enterprisesthat have ties with the city centre. The prospect of amarkedly improved connection to the main public>26PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

1 Phases of Development,2010-2020Developmentslive/work mixwork/live mixZuidasqualitative impulse for aborough centreurban regenerationlive/work mix underdevelopmentwork/live mix underdevelopmentwork zone underdevelopmentZuidas under developmentongoing urbanregenerationqualitative impulse for ametropolitan parkqualitative impulse for acity parkqualitative impulse forpublic spacepostcode area 1012 projectincrease in rail capacityindicative route for HQPT(bus/tram/metro)increase in capacity formotor vehiclesreduction in capacity formotor vehiclesnew ferry connectionmetro sidingsGeneral optionswater- or groundwaterrelatedprojectplanned P+R sitererouting of a cycle pathincrease in station capacitytemporary berths forinland shipping2nd ocean liner terminalintensification of port areastudy area*sea lock* See note on page 09.101 | 2011 27

y Rein de Meijerer.de.meijere@dro.amsterdam.nlThe Structural Vision’sstatutory basis2 The Main Green Structure(Hoofdgroenstructuur, or HGS),showing different types of greenspace.Types of green spacecuriositiescorridorscrubland/naturediscovery areapolder on the urbanperipherycity parkcemeteryallotment complex/schoolgardensports park3 The Noorder IJplas lake.Photo: Wim MolenaarThe basis for the municipal Structural Vision isArt. 2.1 of the new Spatial Planning Act (Wetruimtelijke ordening, or Wro), which came intoforce on 1 July 2008 and replaced the old SpatialPlanning Act (Wet op de Ruimtelijke Ordening,or WRO) dating from 1965.Art. 2.1 is formulated coercively: ‘The municipalcouncil is obliged to enact one or more structuralvisions for the purpose of a well-organized spatialplanning for the municipality’s entire territory.’The Wro does not provide for any direct sanctionin the instance of a municipality failing to fulfil thisobligation.National and provincial tiers of government arealso obliged to draw up one or more structuralvisions. There is no hierarchy between the structuralvisions of national, provincial and municipalgovernments. Leaving aside the question ofwhether this is desirable, the structural visions ofthe government bodies concerned can actuallyconflict with one another.The municipal structural vision sets out the mainfeatures of the intended spatial developmentwithin the municipal territory and the mainpoints of the spatial policy to be pursued by themunicipal council. The Structural Vision must alsoaddress how the council envisages implementingthat proposed development.Just like the structural plan, its predecessorunder the old WRO, the municipal structural visionis a purely indicative policy document. This meansthat it is impossible to lodge an objection or anappeal against a structural vision. The SpatialPlanning Decree’s only provision is that a structuralvision must explain how citizens and socialorganisations were involved in its preparation.The City of <strong>Amsterdam</strong> has nevertheless offeredthe city’s inhabitants the opportunity to make theirviews known to the council in response to thepublic presentation of the Draft Structural Vision2010 (Ontwerp Structuurvisie 2010).A structural vision effectively represents acommitment only for the body that institutes it.This does not, however, alter the fact that, whenthe occasion arises and providing it is properlyjustified, the municipal council may diverge fromthe contents of an enacted structural vision.transport network, first to the west and in about adecade’s time to the east of the Sixhaven, is a hugehelp in this process, into which the implementationagenda provides insight.The set of instrumentsActual plans must obviously satisfy the rules of law andthe relevant policy frameworks of national, provincialand municipal tiers of government. In addition theymust fit in with the mutual agreements between themunicipalities within the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> MetropolitanArea. With the Structural Vision, <strong>Amsterdam</strong> iscommitting itself, the city boroughs included, to rulesthat spatial plans must meet. This also allows the CityExecutive to retain control over the execution of plans.One of the tasks that <strong>Amsterdam</strong> has set itself is tointensify land use within the city while at the sametime keeping the surrounding landscape open.This leads to some important basic principles: thegreen spaces in and around the city require robustprotection, while other parts of the city are optimallyexploited. Densification also leads to transformation(often gradual) and a greater mix of functions. Thatplaces great demands on the existing infrastructureand public space. Respecting <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s wealthof cultural-historical treasures is an importantprecondition in this equation.Keeping it openThe green space in and around the city contributessignificantly to the quality of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s living andworking environment. It is one of the reasons why ourcity is popular as a place of residence and as a businesslocation. The minimum amount of green space that<strong>Amsterdam</strong> wants to safeguard is prescribed in theMain Green Structure (Hoofdgroenstructuur, or HGS).The zones to be included within the HGS and howthese are characterized was re-evaluated in consultationwith the city boroughs.Green spaces that are part of the HGS acquirea certain status. The ambition is to make additionalinvestments in these areas over the coming years.Over against this, the construction or surfacing over(e.g. for roads) within the HGS is subject to strict rules.The green space around the Noorder IJplas lakewas previously set aside for industrial activity with arelatively high environmental impact. This idea has nowbeen abandoned and this green zone will be giventhe status and protection of being part of the HGS.The lake and the surrounding scrubland will assume animportant recreational function for the inhabitants ofthe Borough of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>-North and the Zaanstadregion. In the longer term it will also make a positivecontribution to the broadly outlined ambitions fortransformations along the Waterfront after 2030.>28 PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

2329

45630PLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong>

4 The high-rise visionUNESCO area in the<strong>Amsterdam</strong> city centre2 km zone around theUNESCO areazone alongside aninfrastructure bundlezone alongside aninfrastructure bundle,outside <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’smunicipal boundariesboundariesOVOVOVhigh-rise accents alongthe IJ waterwayCentral Station publictransport hubpublic transport hubpublic transport hubSchiphol Airportport<strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s wedgesof greenery5 Artist’s impression of thehigh-rise cluster at the formerShell precincts.Artist’s impression: Cees van derGiessen6 Panorama from the RiverAmstel looking towards theOmval high-rise quarter.Photo: Edwin van EisDensificationHigh-rise construction is hardly a new phenomenon for<strong>Amsterdam</strong>. The city now boasts a number of highlydistinctive high-rise clusters, which people use fororientation when approaching the city from thesurrounding landscape. Besides being a means tointensify land use, high-rise is also a powerful urbandevelopment instrument. For example, it has beenemployed along the Waterfront, where towers oneither side of the IJ waterway enhance the spatialrelationship between the two parts of the city.From the high-rise map in the set of instruments onecan see where high-rise is being encouraged fromthe viewpoint of optimum land use or because thereis reason for a hefty landscape-related or urbandevelopment accent. This arises in particular in theeasily accessible and highly visible zones alongsidenational trunk roads, except in specific cases wherethere are solid grounds for raising objections forlandscape-related reasons. This largely applies whenthere is the danger of a negative impact on the‘areas of exceptional value’, such as the city centre’sprotected cityscape and the section of the historicalring of canals that was inscribed on UNESCO’s WorldHeritage List since 2010. The high-rise policy is stricterthan in the past, especially in these zones.The Structural Vision is not just the source of inspirationbut incorporates the joint agreements about itsrealization as well, in terms of a timeline as well as interms of legislation and joint agreements. As noted, itis impossible to do everything everywhere all at once.Sometimes it is necessary to curb activities at onelocation in order to offer them a good chance ofattaining their full development elsewhere, thusencouraging the right function in the right place at theright time.This issue’s authorsConny Lauwers (b. 1950)– Has been working as an urban planner for the DRO since 1980– Between 1980 and 1987 she was involved in the urban regeneration processfor <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s Dapper, Oosterpark and Transvaal neighbourhoods– From 1987 to 1994 she designed urban developments and drew up zoningplans for various port precincts– Since 1992 she has focused on the formulation of planning-related policyframeworks, as well as serving as a policy advisor and assessing policyeffectivenessBarbara Ponteyn (b. 1972)– Has been working as a planning expert for the DRO since 1991– She is active across various fields, including the hotel and food servicesindustry and advertising policy, as well as in the programming of metropolitanprojects such as the Northern and Southern Banks of the IJ, Zuidasand Overamstel– Within the Core Team and the Structural Vision Project Group she was responsiblefor the organization and passage of the Structural Vision through toits governmental enactment– Coordination and editing of the Memorandum of Responses and jointlyresponsible for the final editing of the Structural VisionKoos van Zanen (b. 1963)– Has been working as a planning expert for the DRO since 1992– He has focused on aspects that include residential issues and the housingmarket in the <strong>Amsterdam</strong> Metropolitan Area– Devises spatial policy for the knowledge economy in the city– Served as the Structural Vision’s general editorDuring the Structural Vision’spreparation, the DRO collaboratedclosely with other municipal departmentsinvolved in spatial development. The DROwas responsible for the project managementand provided most of the core team. Theproject group consisted of the followingpeople:Leonie van den Beuken (Port of<strong>Amsterdam</strong>)Ton Bossink (DRO, project managerfrom January 2008 to March 2010)Ellen Croes (DRO)Remco Daalder (DRO, project managerfrom April 2010)Kees Dignum (Housing and Social SupportDepartment)Pito Dingemanse (Port of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>)C.J. Dippel (Economic Affairs Department),Marthe van der Horst (Waternet)Suzanne Jeurissen (DRO)Eef Keijzer (DRO)Fokko Kuik (Department of Infrastructure,Traffic and Transport)Marlies Lambregts (Environmental andBuilding Department)Conny Lauwers (DRO)Margreet Leclercq (DRO)Bas van Leeuwen (DRO/<strong>Amsterdam</strong>Development Corporation)Marloes Michels (City Administration)Barbara Ponteyn (DRO)Esther Reith (DRO)Keimpe Reitsma (<strong>Amsterdam</strong> DevelopmentCorporation)Walewijn de Vaal (<strong>Amsterdam</strong> EngineeringBureau)Wouter van der Veur (DRO)Ronald Wiggers (Social DevelopmentDepartment)Gerard Willemsen (DRO, coordinator ofthe planMER)Paul Wolfs (Project Management Bureau)and Koos van Zanen (DRO)01 | 2011 31

City View 01/11Urgency in the light of demographicdevelopments15,00010,0005,000natural increase in populationnet domestic migrationnet international migrationpopulation growth0-5,000Growth of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s population,1995-2010-10,0001995 2000 2005 2010InwonersTotaal aantal inwonershigh density+ +in 2010hoge dichtheidaverage densitygemiddelde dichtheidlow density- -lage dichtheidsterk dalendsharp decreasevrijwelonveranderdalmost unchangedtrend 2000-2010sterk stijgendsharp increaseDevelopment of the total number ofinhabitants, 2000-2010GroningenLeidenDen HaagDelftRotterdamTilburgUtrechtNijmegenEindhovenThe thickness of the lines indicates therelative rate of migration to <strong>Amsterdam</strong>from the rest of the Netherlands in 2009In 2010 <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s population grew spectacularly. Talented peoplefrom the Netherlands and abroad, many of them young, are movingto the Dutch capital. This influx is important for the economy, but wehave to ensure that <strong>Amsterdam</strong> remains accessible for this newcomers.There is no longer any time for uncertainty or delay: <strong>Amsterdam</strong> andthe region must quickly join forces. They need to jointly invest in astrong and sustainable metropolis and ensure that <strong>Amsterdam</strong>, as theregion’s core city, retains its force of attraction!City View 01/11: Julian Jansen, a DRO demographer, on theconsequences of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’s spectacular population growthj.jansen@dro.amsterdam.nlPLAN<strong>Amsterdam</strong> is published by the City of <strong>Amsterdam</strong>’sDepartment of Physical Planning and can be downloaded fromwww.dro.amsterdam.nl.