Promoting the Rights of Children with Disabilities, UNICEF

Promoting the Rights of Children with Disabilities, UNICEF

Promoting the Rights of Children with Disabilities, UNICEF

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>1

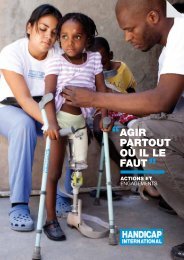

The opinions expressed are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors andeditors and do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> policies or views<strong>of</strong> <strong>UNICEF</strong>.Front cover photo: © <strong>UNICEF</strong>/HQ05-1787/Giacomo PirozziDesign and Layout: Gerber Creative, Denmark© 2007 The United Nations <strong>Children</strong>’s Fund (<strong>UNICEF</strong>)ISBN: 978-88-89129-60-9ISSN: 1028-3528

Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>

AcknowledgementsThe <strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti Research Centre in Florence,Italy, was established in 1988 to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>research capability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Nations <strong>Children</strong>’sFund and to support its advocacy for childrenworldwide. The Centre (formally known as <strong>the</strong>International Child Development Centre) helps toidentify and research current and future areas <strong>of</strong><strong>UNICEF</strong>’s work. Its prime objectives are to improveinternational understanding <strong>of</strong> issues relating tochildren’s rights and to help facilitate <strong>the</strong> full implementation<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> United Nations Convention on <strong>the</strong><strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child in developing and industrializedcountries. Innocenti Digests are produced by <strong>the</strong>Centre to provide reliable and accessible informationon specific child rights issues.The underlying research for this issue <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Innocenti Digest was carried out by Michael Miller.It has been updated and completed by Peter Mittlerand David Parker. The Digest was prepared under<strong>the</strong> guidance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Innocenti Research Centre’sDirector, Marta Santos Pais.Thanks are extended to Nora Groce, GulbadanHabibi and Lena Saleh for <strong>the</strong>ir expert guidanceand perspectives. This publication benefitedfrom <strong>the</strong> contributions <strong>of</strong> participants in an initialconsultation held at <strong>UNICEF</strong> IRC including TonyBooth, Susie Burrows, Nigel Cantwell, SunilDeepak, Gaspar Fajth, Maryam Farzanegan,Garren Lumpkin, Maura Marchegiani, PennyMittler, Michael O’Flaherty, Richard Rieser, FloraSibanda Mulder, Alan Silverman, Sheriffo Sonko,Marc Suhrcke, Illuminata Tukai, Renzo Vianelloand Christina Wahlund Nilsson. Significantcontributions, including comments on drafts,were subsequently made by Naira Avetisyan, NoraGroce, Geraldine Mason Halls, Garren Lumpkin,Reuben McCarthy, Federico Montero, Kozue KayNagata, Voichita Pop, Smaranda Poppa, MartaSantos Pais, Helen Schulte, Nicola Shepherd andTraian Vrasmas. The input <strong>of</strong> Nicola Shepherd inrelation to <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons<strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> is particularly acknowledged.Research support was provided by ShaistaAhmed, Adam Eckstein, Virginia Dalla Pozza,Monica Della Croce, Sarah Enright and GeorgStahl. Administrative support was provided byClaire Akehurst. The IRC Communication andPartnership Unit is thanked for providing editorialand production support for <strong>the</strong> document.The Innocenti Research Centre is grateful to <strong>the</strong><strong>UNICEF</strong> Programme Division, to <strong>UNICEF</strong> countryand regional <strong>of</strong>fices, and to <strong>the</strong> United NationsDivision <strong>of</strong> Economic and Social Affairs and <strong>the</strong>World Health Organization, for <strong>the</strong>ir inputs andsupport in this cooperative undertaking.<strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti Research Centre gratefullyacknowledges <strong>the</strong> support provided to<strong>the</strong> Centre by <strong>the</strong> Government <strong>of</strong> Italy andspecifically for this project by <strong>the</strong> Governments<strong>of</strong> Sweden and Switzerland.Previous Innocenti Digest titles are:• Ombudswork for <strong>Children</strong>• <strong>Children</strong> and Violence• Juvenile Justice• Intercountry Adoption• Child Domestic Work• Domestic Violence against Women and Girls• Early Marriage: Child Spouses• Independent Institutions Protecting<strong>Children</strong>’s <strong>Rights</strong>• Birth Registration: Right from <strong>the</strong> start• Poverty and Exclusion among Urban <strong>Children</strong>• Ensuring <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Indigenous <strong>Children</strong>• Changing a Harmful Social Convention:Female genital mutilation/cuttingFor fur<strong>the</strong>r information and to download or toorder <strong>the</strong>se and o<strong>the</strong>r publications, please visit<strong>the</strong> website at .The Centre’s publications are contributions to aglobal debate on child rights issues and includea wide range <strong>of</strong> opinions. For that reason, <strong>the</strong>Centre may produce publications that do notnecessarily reflect <strong>UNICEF</strong> policies or approacheson some topics. The views expressed are those<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors and are published by <strong>the</strong> Centre inorder to stimulate fur<strong>the</strong>r dialogue on child rights.Extracts from this publication may be freelyreproduced, provided that due acknowledgementis given to <strong>the</strong> source and to <strong>UNICEF</strong>.Correspondence should be addressed to:<strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti Research CentrePiazza SS. Annunziata, 1250122 Florence, ItalyTel: (39) 055 20 330Fax: (39) 055 2033 220Email: florence@unicef.orgWebsite: www.unicef-irc.orgii <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

CONTENTSExecutive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ivEditorial . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vi1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1<strong>Promoting</strong> inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Scope <strong>of</strong> this Digest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1Box 1.1: Disability terminology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 How many children<strong>with</strong> disabilities?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Box 2.1: Changing levels <strong>of</strong> disability inCEE/CIS and <strong>the</strong> Baltic States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 Disability and inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5The ’social model’ <strong>of</strong> disability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Disability and poverty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 International standardsand mechanisms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Box 4.1: Human rights instruments andhigh-level decisions reinforcing <strong>the</strong> rights<strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8O<strong>the</strong>r international human rightsinstruments and decisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9UN Standard Rules on <strong>the</strong> Equalization <strong>of</strong>Opportunities for Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> . . . . . . . . . 9Box 4.2: Work <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> UN Special Rapporteuron Disability. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons<strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Article 7: <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> disabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Article 24: Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Article 32: International cooperation . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Monitoring implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention . . . . . 12Implementation at national level: Next steps . . . . . . 12Millennium Development Goals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Box 4.3: Millennium Development Goals. . . . . . . . . . 135 Human rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong>disabilities today . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Global review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities by <strong>the</strong> UN Committeeon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Confronting discrimination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14Box 5.1: Disability and gender . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Access to health, rehabilitation andwelfare services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15Access to education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16Institutionalization and lack <strong>of</strong> appropriate care . . . . 17Protection from violence, exploitation and abuse . . . 19Disability in conflict and emergency situations . . . . . 19Box 5.2: Landmines cause disability in Angola . . . . . 20Participation and access to opportunities . . . . . . . . . 206 Foundations for inclusion . . . . . . . . . . . 22Working <strong>with</strong> families . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Box 6.1: The Portage Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23Box 6.2: Parent advocacy in Newham, London . . . . . 24Working <strong>with</strong> communities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Box 6.3: WHO programme ondisability and rehabilitation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Community-based rehabilitation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Box 6.4: Using local resources toproduce low-cost aids in Mexico and<strong>the</strong> Philippines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26From institutions to communities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Towards inclusive schools and learningenvironments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Box 6.5: Bulgaria’s National SocialRehabilitation Centre . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Box 6.6: Inclusive schooling in Italy:A pioneering approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29Box 6.7: Uganda: An example <strong>of</strong>inclusive planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29Training teachers for inclusive education . . . . . . . . . 30Box 6.8: Empowering teachers in Lesotho . . . . . . . . 30Involving children <strong>with</strong> disabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317 Ensuring a supportiveenvironment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Local governance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Laws and policies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32Box 7.1: Nicaragua: Coordination promotes<strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . 33Box 7.2: Raising disability awarenessin <strong>the</strong> Maldives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34“Nothing about us <strong>with</strong>out us” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Changing attitudes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Budget allocations and priorities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Box 7.3: Monitoring human rightsviolations and abuse against persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Monitoring . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35International and regional partnerships . . . . . . . . . . 358 Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38Notes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39Links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong>Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Optional Protocol to <strong>the</strong> Convention on<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY<strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> disabilities and <strong>the</strong>ir families constantlyexperience barriers to <strong>the</strong> enjoyment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir basichuman rights and to <strong>the</strong>ir inclusion in society. Theirabilities are overlooked, <strong>the</strong>ir capacities are underestimatedand <strong>the</strong>ir needs are given low priority. Yet, <strong>the</strong>barriers <strong>the</strong>y face are more frequently as a result <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> environment in which <strong>the</strong>y live than as a result <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong>ir impairment.While <strong>the</strong> situation for <strong>the</strong>se children is changing for<strong>the</strong> better, <strong>the</strong>re are still severe gaps. On <strong>the</strong> positiveside, <strong>the</strong>re has been a ga<strong>the</strong>ring global momentumover <strong>the</strong> past two decades, originating <strong>with</strong> persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities and increasingly supported by civilsociety and governments. In many countries, small,local groups have joined forces to create regional ornational organizations that have lobbied for reformand changes to legislation. As a result, one by one<strong>the</strong> barriers to <strong>the</strong> participation <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesas full members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir communities arestarting to fall.Progress has varied, however, both between and<strong>with</strong>in countries. Many countries have not enactedprotective legislation at all, resulting in a continuedviolation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities.The Innocenti Digest on <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> attempts to provide aglobal perspective on <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> some 200million children <strong>with</strong> disabilities. The Digest is basedon reports from countries across regions and froma wide range <strong>of</strong> sources. These include accounts bypersons <strong>with</strong> disabilities, <strong>the</strong>ir families and members<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir communities, pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, volunteers andnon-governmental organizations, as well as countryreports submitted by Member States to <strong>the</strong> UnitedNations, including to human rights treaty bodiesresponsible for monitoring <strong>the</strong> implementation <strong>of</strong>international human rights treaties.This Digest focuses particularly on <strong>the</strong> Convention on<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child (CRC) and <strong>the</strong> Convention on<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> (CRPD). Thelatter instrument was signed by an unprecedented81 countries on opening day, 30 March 2007. As <strong>of</strong>15 August 2007, 101 countries had signed <strong>the</strong> CRPDand 4 had ratified it. For entry into force, it is necessarythat <strong>the</strong> Convention receive 20 ratifications. The<strong>Disabilities</strong> Convention <strong>of</strong>fers a unique opportunityfor every country and every community to reexamineits laws and institutions and to promote changesnecessary to ensure that persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesare guaranteed <strong>the</strong> same rights as all o<strong>the</strong>r persons.It expresses basic human rights in a manner that addresses<strong>the</strong> special needs and situation <strong>of</strong> persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities and provides a framework for ensuringthat those rights are realized.Understanding barriers to inclusionThe social model <strong>of</strong> disability acknowledges that obstaclesto participation in society and its institutionsreside in <strong>the</strong> environment ra<strong>the</strong>r than in <strong>the</strong> individual,and that such barriers can and must be prevented,reduced or eliminated.Environmental obstacles come in many guises andare found at all levels <strong>of</strong> society. They are reflectedin policies and regulations created by governments.Such obstacles may be physical – for example barriersin public buildings, transportation and recreationalfacilities. They may also be attitudinal – widespreadunderestimation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> abilities and potential <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities creates a vicious cycle <strong>of</strong> underexpectation,under-achievement and low priority in<strong>the</strong> allocation <strong>of</strong> resources.Poverty is a pervasive barrier to participation worldwide,and is both a cause and a consequence <strong>of</strong>disability. Families living in poverty are much morevulnerable to sickness and infection, especially ininfancy and early childhood. They are also less likelyto receive adequate health care or to be able to payfor basic medicines or school fees. The costs <strong>of</strong> caringfor a child <strong>with</strong> a disability create fur<strong>the</strong>r hardshipfor a family, particularly for mo<strong>the</strong>rs who are<strong>of</strong>ten prevented from working and contributing t<strong>of</strong>amily income.Needed actionsThe articles <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons<strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> spell out <strong>the</strong> specific areas thatneed to be addressed, as well implementation andmonitoring mechanisms. These are complementaryto <strong>the</strong> recommendations issued by <strong>the</strong> Committee on<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child to governments.A major task for international agencies and <strong>the</strong>irnational partners is to ensure that persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesare automatically but explicitly included in <strong>the</strong>initial objectives, targets and monitoring indicators <strong>of</strong>all development programmes, including <strong>with</strong> thoseframed by <strong>the</strong> Millennium Agenda.At national level a number <strong>of</strong> specific actions arecalled for by relevant UN standards. The most important<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se actions are to:1.In partnership <strong>with</strong> organizations <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong>disabilities undertake a comprehensive reviewiv <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

<strong>of</strong> all legislation in order to ensure its conformity<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong>se standards, in particular <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong>children and adults <strong>with</strong> disabilities. All relevantlegislation and regulations should include a prohibition<strong>of</strong> discrimination on grounds <strong>of</strong> disability.2. Provide for effective remedies in case <strong>of</strong> violations<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities andensure that <strong>the</strong>se remedies are accessible to allchildren, families and caregivers.3. Develop a national plan <strong>of</strong> action that integrates<strong>the</strong> relevant provisions <strong>of</strong> all applicable internationalinstruments. Such plans should specifymeasurable and timebound targets as well asevaluation indicators, and should be resourcedaccordingly.4. Create a focal point for disability in each relevantdepartment, as well as a high-level multisectoralCoordinating Committee, <strong>with</strong> members drawnfrom relevant ministries and organizations <strong>of</strong> persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities. This committee should beempowered to initiate proposals, suggest policiesand monitor progress.5. Develop independent monitoring mechanisms,such as an Ombudsperson or <strong>Children</strong>’s Commissioner,and ensure that children and families areaware <strong>of</strong> and fully supported in gaining access tosuch mechanisms.6. Make concerted efforts to ensure that <strong>the</strong> necessaryresources are allocated to and for children<strong>with</strong> disabilities and <strong>the</strong>ir families. This includesfree primary and secondary education in accessiblebuildings, training <strong>of</strong> teachers and o<strong>the</strong>r pr<strong>of</strong>essionals,financial support and social security.Each child should be provided <strong>with</strong> appropriateindividual support, including assistive devices,sign language, Braille materials and a differentiatedand accessible curriculum.7. Establish programmes for <strong>the</strong> deinstitutionalization<strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities, placing <strong>the</strong>m <strong>with</strong><strong>the</strong>ir families or <strong>with</strong> foster families who shouldbe assisted <strong>with</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional and financial support.National standards <strong>of</strong> care and appropriatetraining should be in place and rigorously monitoredto safeguard <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> those childrenthat remain in institutions.8. Conduct awareness-raising and educational campaignsfor <strong>the</strong> public, as well as specific groups<strong>of</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> aim <strong>of</strong> preventing andaddressing <strong>the</strong> de facto discrimination <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities.9. Implement a system <strong>of</strong> community services andsupport for children <strong>with</strong> disabilities.10. Ensure that organizations <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesare consulted in relevant planning and policymaking, and are duly represented and financiallysupported in extending <strong>the</strong>ir activities. <strong>Children</strong><strong>with</strong> disabilities should be supported in making<strong>the</strong>ir voices heard.Such actions taken by governments will promote andfacilitate <strong>the</strong> efforts by families and communities insupport <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities.ConclusionsIn countries <strong>the</strong> world over children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesand <strong>the</strong>ir families continue to face discrimination andare not yet fully able to enjoy <strong>the</strong>ir basic human rights.The inclusion <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities is a matter <strong>of</strong>social justice and an essential investment in <strong>the</strong> future<strong>of</strong> society. It is not based on charity or goodwill but isan integral element <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expression and realization<strong>of</strong> universal human rights.The last two decades have witnessed a ga<strong>the</strong>ringglobal momentum for change. Many countries havealready begun to reform <strong>the</strong>ir laws and structures andto remove barriers to <strong>the</strong> participation <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong>disabilities as full members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir communities.The Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>,building upon <strong>the</strong> existing provisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Conventionon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, opens a new erain securing <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities and<strong>the</strong>ir families. Toge<strong>the</strong>r <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> Millennium Agendaand o<strong>the</strong>r international initiatives, <strong>the</strong>se internationalstandards lay <strong>the</strong> foundation for each country and communityto undertake a fundamental review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situation<strong>of</strong> children and adults <strong>with</strong> disabilities and to takespecific steps to promote <strong>the</strong>ir inclusion in society.Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>v

EditorialThe rights <strong>of</strong> all disabled people, including those<strong>of</strong> children, have been reiterated and given a newimpetus <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong>Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>, which was signed onopening day, 30 March 2007, by <strong>the</strong> representatives<strong>of</strong> an unprecedented 81 countries. This follows anunequivocal statement made by Heads <strong>of</strong> Stateand Government, adopted by <strong>the</strong> United NationsGeneral Assembly following <strong>the</strong> May 2002 SpecialSession on <strong>Children</strong>:Each girl and boy is born free and equal in dignityand rights; <strong>the</strong>refore, all forms <strong>of</strong> discriminationaffecting children must end.... We will take allmeasures to ensure <strong>the</strong> full and equal enjoyment<strong>of</strong> all human rights and fundamental freedoms,including equal access to health, education andrecreational services, by children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesand children <strong>with</strong> special needs, to ensure <strong>the</strong>recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir dignity, to promote <strong>the</strong>ir selfreliance,and to facilitate <strong>the</strong>ir active participationin <strong>the</strong> community. 1The daily reality for most children <strong>with</strong> a disabilityis that <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>of</strong>ten condemned to a ’poor start inlife’ and deprived <strong>of</strong> opportunities to develop to <strong>the</strong>irfull potential and to participate in society. They areroutinely denied access to <strong>the</strong> same opportunitiesfor early, primary and secondary education, orlife-skills and vocational training, or both, that areavailable to o<strong>the</strong>r children. They ei<strong>the</strong>r have no voiceor <strong>the</strong>ir views are discounted. Although <strong>the</strong>y areinvariably more vulnerable to abuse and violence,<strong>the</strong>ir testi-mony is <strong>of</strong>ten ignored or dismissed.In this way, <strong>the</strong>ir isolation is perpetuated as <strong>the</strong>yprepare for adult life.Yet <strong>the</strong>re are changes for <strong>the</strong> better. Much hasbeen accomplished by governments and <strong>the</strong>irpartners working at all levels <strong>of</strong> society. Increasingnumbers <strong>of</strong> children who would have previouslybeen sent to segregated schools or even beendenied an education altoge<strong>the</strong>r now attend regularclasses at <strong>the</strong>ir local school and are accepted asmembers <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir local community. Achieving<strong>the</strong> full participation in society <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong>disabilities is an objective <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> global disabilityrights movement, a powerful initiative by persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities to claim <strong>the</strong>ir basic human rights.This movement is gaining momentum and hasrecorded impressive achievements. Disabledpersons’ organizations have successfully promotededucation reforms in many countries, and <strong>the</strong>yhave been recognized as a major force behind <strong>the</strong>process leading to <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong>Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>.vi <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

While <strong>the</strong>re are grounds for optimism, we are still farfrom seeing all <strong>the</strong> world’s 200 million children <strong>with</strong>disabilities enjoying effective and equitable access tobasic social services and meaningful participation insociety. For example, around 90 per cent <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities in developing countries do notattend school.Society must adapt its structures to ensure that allchildren, irrespective <strong>of</strong> age, gender and disability,can enjoy <strong>the</strong> human rights that are inherent to <strong>the</strong>irhuman dignity <strong>with</strong>out discrimination <strong>of</strong> any kind. Internationalhuman rights standards, including <strong>the</strong> Conventionon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, <strong>the</strong> UN StandardRules on <strong>the</strong> Equalization <strong>of</strong> Opportunities for Persons<strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong>Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>, all point <strong>the</strong> way towardsovercoming discrimination and recognizing <strong>the</strong> rightto full participation <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities – in <strong>the</strong>home and community, in school, health services, recreationactivities and in all o<strong>the</strong>r aspects <strong>of</strong> life.This Innocenti Digest addresses inclusion in <strong>the</strong> widestsocietal sense and gives particular attention toinclusive strategies for all levels <strong>of</strong> education. Earlychildhood development interventions and informaleducation play a critical role in promoting children’sdevelopment and in preparing <strong>the</strong>m for adult life asactive participants in <strong>the</strong> local community and society.It is a means for raising children’s awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>irrights and overcoming prejudice and discrimination.Through education children acquire <strong>the</strong> skills necessaryto reach <strong>the</strong>ir full potential, both as individualsand citizens. Education <strong>of</strong>fers one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most effectivemeans to break <strong>the</strong> cycle <strong>of</strong> poverty that all too<strong>of</strong>ten overtakes children <strong>with</strong> disabilities and <strong>the</strong>irfamilies. Education can also prepare o<strong>the</strong>r childrenand <strong>the</strong> surrounding community to promote inclusionand to be more receptive to and supportive <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities.Disability cannot be considered in isolation. It cutsacross all aspects <strong>of</strong> a child’s life and can have verydifferent implications at different stages in a child’slife cycle. Many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> initiatives to promote <strong>the</strong>rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities overlap <strong>with</strong> thosefor o<strong>the</strong>r excluded groups. This Innocenti Digestaims, <strong>the</strong>refore, to encourage actors at all levels −from <strong>the</strong> local to <strong>the</strong> international − to include children<strong>with</strong> disabilities in all <strong>the</strong>ir programmes andprojects and to ensure that no child is left out.The information presented here makes it abundantlyclear that real progress is possible in all countries,including <strong>the</strong> poorest, and that obstacles seeming tobe insurmountable can be overcome.Marta Santos PaisDirector<strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti Research CentreInnocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>vii

1 INTRODUCTIONThe Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child (CRC)recognizes <strong>the</strong> human rights <strong>of</strong> all children, includingthose <strong>with</strong> disabilities. The Convention contains aspecific article recognizing and promoting <strong>the</strong> rights<strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities. Along <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> CRC, <strong>the</strong>Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>(CRPD), adopted by <strong>the</strong> United Nations GeneralAssembly in December 2006, provides a powerfulnew impetus to promote <strong>the</strong> human rights <strong>of</strong> allchildren <strong>with</strong> disabilities.In spite <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> almost universal ratification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, and <strong>the</strong> socialand political mobilization that led to adoption <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>,disabled children and <strong>the</strong>ir families continue to beconfronted <strong>with</strong> daily challenges that compromise <strong>the</strong>enjoyment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir rights. Discrimination and exclusionrelated to disabilities occur in all countries, in allsectors <strong>of</strong> society and across all economic, political,religious and cultural settings.<strong>Promoting</strong> inclusionHuman rights have provided both <strong>the</strong> inspiration and<strong>the</strong> foundation for <strong>the</strong> movement towards inclusionfor children <strong>with</strong> disabilities. Inclusion requires <strong>the</strong>recognition <strong>of</strong> all children as full members <strong>of</strong> societyand <strong>the</strong> respect <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir rights, regardless<strong>of</strong> age, gender, ethnicity, language, poverty orimpairment. Inclusion involves <strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> barriersthat might prevent <strong>the</strong> enjoyment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se rights, andrequires <strong>the</strong> creation <strong>of</strong> appropriate supportive andprotective environments.The UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization(UNESCO) states that <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> children whowould o<strong>the</strong>rwise be perceived as ’different’ means“changing <strong>the</strong> attitudes and practices <strong>of</strong> individuals,organisations and associations so that <strong>the</strong>y can fullyand equally participate in and contribute to <strong>the</strong> life<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir community and culture. An inclusive societyis one in which difference is respected and valued,and where discrimination and prejudice are activelycombated in policies and practices.” The WorldConference on Special Needs Education, organizedby UNESCO and held in Salamanca, Spain, in 1994,recommended that inclusive education should be <strong>the</strong>norm. 2 This has now been reaffirmed in <strong>the</strong> new Conventionon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>.In <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> education, inclusion means <strong>the</strong>creation <strong>of</strong> barrier-free and child-focused learningenvironments, including for <strong>the</strong> early years. It meansproviding appropriate supports to ensure that allchildren receive education in non-segregated localfacilities and settings, whe<strong>the</strong>r formal or informal. It isframed by article 29 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, which requires that <strong>the</strong> child’s educationbe directed to <strong>the</strong> development <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir personality,talents and mental and physical abilities to <strong>the</strong>ir fullestpotential; to <strong>the</strong> preparation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child for responsiblelife in a free society, in <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> understandingand tolerance.Inclusion is a process that involves all children,not just a number <strong>of</strong> ’special’ children. It givesnon-disabled children <strong>the</strong> experience <strong>of</strong> growingup in an environment where diversity is <strong>the</strong> normra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> exception. It is when <strong>the</strong> educationsystem fails to provide for and accommodatethis diversity that difficulties arise, leading tomarginalization and exclusion.Inclusion is not <strong>the</strong> same as ’integration’, which impliesbringing children <strong>with</strong> disabilities into a ’normal’mainstream or helping <strong>the</strong>m to adapt to ’normal’standards. For example, in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> schooling,integration means <strong>the</strong> placement <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesin regular schools <strong>with</strong>out necessarily makingany adjustments to school organization or teachingmethods. Inclusion, on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, requires thatschools adapt and provide <strong>the</strong> needed support to ensurethat all children can work and learn toge<strong>the</strong>r.Scope <strong>of</strong> this DigestThe enjoyment <strong>of</strong> human rights by children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiescan be fully realized only in an inclusive society,that is, a society in which <strong>the</strong>re are no barriers toa child’s full participation, and in which all children’sabilities, skills and potential are given full expression.The Digest reviews concrete initiatives and strategiesfor advancing <strong>the</strong> social inclusion <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities. These initiatives are by no meansconfined to income-rich countries. Indeed, some <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> poorest countries in <strong>the</strong> world are now leading<strong>the</strong> way through a combination <strong>of</strong> political will, partnership<strong>with</strong> local communities and, above all, <strong>the</strong>involvement <strong>of</strong> children and adults <strong>with</strong> disabilities indecision-making processes.This Digest is intended to help raise <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ile<strong>of</strong> childhood disability and to give impetus to <strong>the</strong>challenge <strong>of</strong> ensuring that children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesare fully included in efforts to promote <strong>the</strong> humanrights <strong>of</strong> all children. It examines <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>of</strong>children <strong>with</strong> disabilities from a global perspective,considering countries and societies <strong>with</strong> widely differinglevels <strong>of</strong> economic development and serviceprovision, and a variety <strong>of</strong> sociocultural realitiesthat influence attitudes towards persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities.It seeks to demonstrate that <strong>the</strong> inclusivepolicies and practices required to promote <strong>the</strong>enjoyment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se children are bothfeasible and practical.1 <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

© <strong>UNICEF</strong>/HQ95-0451/David BarbourBox 1.1 Disability terminologyLanguage is powerful and <strong>the</strong> choice <strong>of</strong> words usedcan ei<strong>the</strong>r perpetuate social exclusion or promotepositive values. Accordingly, <strong>the</strong> term ’children<strong>with</strong> disabilities’ ra<strong>the</strong>r than ’disabled children’ isemployed in this Digest to emphasize children’sindividuality ra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong>ir condition.The term ’impairment’ is used to refer to <strong>the</strong> loss orlimitation <strong>of</strong> physical, mental or sensory functionon a long-term or permanent basis. ’Disability’, on<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, is used to describe <strong>the</strong> conditionwhereby physical and/or social barriers prevent aperson <strong>with</strong> an impairment from taking part in <strong>the</strong>normal life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> community on an equal footing<strong>with</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs.The Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>states:Persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities include those who havelong-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensoryimpairments, which in interaction <strong>with</strong> various barriersmay hinder <strong>the</strong>ir full and effective participationin society on an equal basis <strong>with</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs. (Article 1) iUnder <strong>the</strong> International Classification <strong>of</strong>Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) establishedby <strong>the</strong> World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001,disability is conceived as <strong>the</strong> outcome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>interaction between impairments and negativeenvironmental impacts. ii The World HealthOrganization emphasizes that most people willexperience some degree <strong>of</strong> disability at some pointin <strong>the</strong>ir lives. Accordingly, <strong>the</strong> ICF classificationfocuses on a child’s abilities and strengths and notjust impairments and limitations. It also gradesfunctioning on a scale from no impairment tocomplete impairment. By shifting <strong>the</strong> focus fromcause to impact, ICF places all health conditions onan equal footing.Sources:iUnited Nations, Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong><strong>Disabilities</strong>, United Nations, New York, 2006. See.iiFor more on <strong>the</strong> International Classification, see or contact <strong>the</strong> Classification,Assessment, Surveys and Terminology Unit, WHO (see’Links’ section).Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>2

2 HOW MANY CHILDRENWITH DISABILITIES?It is estimated that, overall, between 500 and 650million people worldwide live <strong>with</strong> a significantimpairment. According to <strong>the</strong> World HealthOrganization (WHO), around 10 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>world’s children and young people, some 200million, have a sensory, intellectual or mental healthimpairment. Around 80 per cent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m live indeveloping countries. 3 Statistics such as <strong>the</strong>sedemonstrate that to be born <strong>with</strong> or acquire animpairment is far from unusual or abnormal.The reported incidence and prevalence <strong>of</strong>impairment in <strong>the</strong> population vary significantly fromone country to ano<strong>the</strong>r. Specialists, however, agreeon a working approximation giving a minimumbenchmark <strong>of</strong> 2.5 per cent <strong>of</strong> children aged 0-14<strong>with</strong> self-evident moderate to severe levels <strong>of</strong>sensory, physical and intellectual impairments.An additional 8 per cent can be expected to havelearning or behavioural difficulties, or both.These estimates were found to be useful in <strong>the</strong>detailed analysis <strong>of</strong> statistics on incidence andprevalence <strong>of</strong> childhood disability in <strong>the</strong> <strong>UNICEF</strong>study on <strong>Children</strong> and Disability in Transitionin CEE/CIS and Baltic States. 4 They are based onresearch and data ga<strong>the</strong>red over years in countries<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest human development rankings.© <strong>UNICEF</strong>/HQ01-0216/Roger LeMoyne3 <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

The minimum benchmark was found particularlyhelpful in comparing <strong>of</strong>ficial country rates to thisstandard since data, if available, are <strong>of</strong>ten not comparablebetween countries. Countries frequentlyuse different classifications, definitions and thresholdsbetween categories <strong>of</strong> ’disabled’ and ’non-disabled’,<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> result that a child who is classifiedas, for example, having a mild impairment accordingto one system might be regarded as not being disabledat all under ano<strong>the</strong>r.Because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> high degree <strong>of</strong> stigma associated<strong>with</strong> disability in certain countries, parents and o<strong>the</strong>rfamily members may be reluctant to report that<strong>the</strong>ir child has a disability. Often <strong>the</strong>se children havenot even had <strong>the</strong>ir birth registered, <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> resultthat <strong>the</strong>y are not known to health, social servicesor schools. In countries where literacy rates are lowand children frequently receive no formal schooling,some learning disabilities (such as dyslexia) maynever be identified. In countries where diagnosisis more advanced and <strong>the</strong> likelihood <strong>of</strong> survivalis greater or where state benefits are available tosupport persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities, <strong>the</strong>re is a greaterincentive to register a child’s disability, thus contributingto a higher recorded prevalence <strong>of</strong> disability.The issue <strong>of</strong> identification is also linked to agegroup: it is not always easy to identify an impairmentin a very young child (a child under three yearsold, for example), and many impairments only becomeevident when a child starts attending school.Some children – especially in developing countries– will also acquire impairments through accidentsand illness, or in conditions <strong>of</strong> civil disturbance andarmed conflict.With regard to data collection, consistent and accurateinformation on children <strong>with</strong> disabilitieshelps to make an ’invisible’ population ’visible’ bydemonstrating <strong>the</strong> extent and, indeed, <strong>the</strong> normality<strong>of</strong> disability. For example, in Gambia, following <strong>the</strong>publication <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> National Disability Survey <strong>of</strong> 1998,recognition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesincreased. The survey, administered to more than30,000 households by a task force that includedpersons <strong>with</strong> disabilities, was conducted to identify<strong>the</strong> kinds <strong>of</strong> disabilities affecting children and <strong>the</strong>irgeographical distribution. The aim was to facilitateprovision <strong>of</strong> services to children <strong>with</strong> disabilities. 5Data on <strong>the</strong> types <strong>of</strong> impairment and <strong>the</strong> numbers<strong>of</strong> children affected can inform service deliveryand improve <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> appropriate aidsand appliances. It also enables <strong>the</strong> monitoring <strong>of</strong>equality <strong>of</strong> opportunity and progress towards <strong>the</strong>achievement <strong>of</strong> economic, social, political andcultural rights. The most useful statistics are thosedisaggregated by gender, age, ethnic origin andurban/rural residence. It is important that figuresare fur<strong>the</strong>r disaggregated in relation to <strong>the</strong> extent<strong>of</strong> impairment, <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong>disabilities living at home or placed in institutions,and <strong>the</strong> number enrolled in regular education orspecial education systems or receiving benefits.Although accurate and representative data ondisability are lacking in many parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world,international efforts are underway to improve <strong>the</strong>quality and availability <strong>of</strong> data. In 2005 <strong>the</strong> UnitedNations Statistics Division initiated <strong>the</strong> systematicand regular collection <strong>of</strong> basic statistics on humanfunctioning and disability by introducing a disabilitystatistics questionnaire to <strong>the</strong> existing datacollection system. 6Box 2.1 Changing levels <strong>of</strong> disability in CEE/CISand <strong>the</strong> Baltic StatesSince <strong>the</strong> break-up <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Soviet Union, manystates in <strong>the</strong> CEE/CIS and Baltic region haveregistered dramatic changes in <strong>the</strong> recordednumber <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities. The totalnumber <strong>of</strong> children recognized as disabled in <strong>of</strong>ficialdata across <strong>the</strong> region tripled, from around500,000 at <strong>the</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> transition to 1.5 millionin 2002. In Estonia, for example, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong>children aged up to 15 <strong>with</strong> disabilities who wereregistered more than doubled from 1,737 in 1989to 4,722 in 2001, while in Ukraine <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong>children aged up to 17 <strong>with</strong> disabilities rose from93,156 in 1992 to 153,453 in 2001. i In Uzbekistan,according to <strong>of</strong>ficial statistics, <strong>the</strong>re were 33,280children registered as having an impairment in1992, while by 1999 this number had increasedto 123,750.These <strong>of</strong>ficial data do not reflect <strong>the</strong> situationfully. There are additional numbers <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities, especially in rural areas, whohave never been <strong>of</strong>ficially registered and whoare effectively hidden because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> stigma attachedto <strong>the</strong>ir condition.A detailed discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> background to andpossible reasons for <strong>the</strong>se dramatic increasescan be found in <strong>the</strong> <strong>UNICEF</strong> report <strong>Children</strong> andDisability in Transition in CEE/CIS and BalticStates. ii The report attributes <strong>the</strong>se changes toa combination <strong>of</strong> improved identification andreporting techniques, and in some cases, <strong>the</strong>incentive <strong>of</strong> improved cash benefits for children<strong>with</strong> disabilities living in <strong>the</strong> community.Sources:iFigures provided from <strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti ResearchCentre, MONEE database. These data were used insupport <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> report ’<strong>Children</strong> and Disability in Transitionin CEE/CIS and Baltic States’, Innocenti Insight,<strong>UNICEF</strong> Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2005.iiIbid.Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>4

3 DISABILITY ANDINCLUSIONThe history <strong>of</strong> disability is for <strong>the</strong> most part one <strong>of</strong>exclusion, discrimination and stigmatization. Oftensegregated from society, persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities –and in particular, children <strong>with</strong> disabilities – have beenregarded as objects <strong>of</strong> charity and passive recipients<strong>of</strong> welfare. This charity-based legacy persists in manycountries and affects <strong>the</strong> perception and treatmentreceived by children <strong>with</strong> disabilities.The ’social model’ <strong>of</strong> disabilityThe human rights approach to disability has led to ashift in focus from a child’s limitations arising fromimpairments, to <strong>the</strong> barriers <strong>with</strong>in society thatprevent <strong>the</strong> child from having access to basic socialservices, developing to <strong>the</strong> fullest potential and fromenjoying her or his rights. This is <strong>the</strong> essence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>social model <strong>of</strong> disability.The emphasis given to equality and non-discriminationin international human rights instruments isreflected in <strong>the</strong> social model <strong>of</strong> disability. This modelrejects <strong>the</strong> long-established idea that obstacles to <strong>the</strong>participation <strong>of</strong> disabled people arise primarily from<strong>the</strong>ir impairment and focuses instead on environmentalbarriers. These include:• prevailing attitudes and preconceptions, leadingto underestimation;• <strong>the</strong> policies, practices and procedures <strong>of</strong> localand national government;• <strong>the</strong> structure <strong>of</strong> health, welfare and educationsystems;• lack <strong>of</strong> access to buildings, transport and to <strong>the</strong>whole range <strong>of</strong> community resources available to<strong>the</strong> rest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> population;• <strong>the</strong> impact <strong>of</strong> poverty and deprivation on <strong>the</strong>community as a whole and more specifically onpersons <strong>with</strong> disabilities and <strong>the</strong>ir families.A great deal can be done to remove or reduce <strong>the</strong>barriers faced by children and adults <strong>with</strong> disabilities.For persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities, this is both a liberatingand an empowering view, one that emphasizes <strong>the</strong>positive contribution that <strong>the</strong>y <strong>the</strong>mselves can makein removing <strong>the</strong> barriers to <strong>the</strong>ir participation. At <strong>the</strong>same time, <strong>the</strong> social model emphasizes <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong>government and civil society in removing <strong>the</strong> obstaclesfaced by citizens <strong>with</strong> disabilities in becoming activeparticipants in <strong>the</strong> various communities in which<strong>the</strong>y live, learn and work.Emphasizing <strong>the</strong> social construction <strong>of</strong> disability inno way implies rejecting medical and pr<strong>of</strong>essionalservices and supports. Nor does it mean denying <strong>the</strong>potential <strong>of</strong> intervention in reducing or alleviating animpairment or in providing rehabilitation or training.Provision <strong>of</strong> technical aids, medical intervention andpr<strong>of</strong>essional support are all important ways <strong>of</strong> promotingempowerment and independence and are anintegral part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> social model. For example, a simplemedical procedure may be all that is required tohelp a child <strong>with</strong> eye or ear infections to benefit fromclassroom learning.Never<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> medical model (sometimes knownas <strong>the</strong> ’defect model’) still exerts a disproportionateinfluence at many levels. For example, teachersand parents sometimes ask questions such as “Canchildren <strong>with</strong> Down’s Syndrome attend an ordinaryschool?” or “How do you teach children <strong>with</strong> musculardystrophy?” The answer to <strong>the</strong> last question wasgiven by a group <strong>of</strong> 48 children <strong>with</strong> muscular dystrophyfrom France:Care providers cannot understand that we are alldifferent, even if we have <strong>the</strong> same condition, <strong>the</strong>same disability. What we want to say to all adultswho take care <strong>of</strong> us is that we are 48 differentpersonalities. There is no personality type knownas muscular dystrophy. 7This quotation emphasizes that <strong>the</strong> rights, needs andvoice <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual child are fundamental. It is thisprinciple that lies at <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Convention on<strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child and is reflected as well in <strong>the</strong>Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>.Disability and povertyThe World Bank has estimated that persons <strong>with</strong>disabilities account for up to one in five <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world’spoorest people, that is, those who live on lessthan one dollar a day and who lack access to basicnecessities such as food, clean water, clothing andshelter. 8 These figures have been brought to life ina recent report from Inclusion International whichdocuments <strong>the</strong> poverty and exclusion experienceddaily by people <strong>with</strong> intellectual disabilities and <strong>the</strong>irfamilies in all regions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world, but which alsorecords many examples <strong>of</strong> how <strong>the</strong>se obstacles arebeginning to be overcome. 9Poverty is both a cause and a consequence <strong>of</strong> disability.Correlates <strong>of</strong> poverty, such as inadequatemedical care and unsafe environments, significantlycontribute to <strong>the</strong> incidence and impact <strong>of</strong> disability,and complicate efforts for prevention and response.By <strong>the</strong> same measure, many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> factors contributingto high levels <strong>of</strong> impairment among children are5 <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

© U<strong>UNICEF</strong>/HQ06-1260/Azhar Mahmoodpotentially preventable, thus <strong>of</strong>fering <strong>the</strong> opportunityto reduce <strong>the</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> disability as well as <strong>of</strong> poverty.Such factors include malnutrition and micronutrientdeficiencies, preventable diseases such as measles,lack <strong>of</strong> sanitation and clean water, as well as violence,abuse and exploitation, including through labour. Lack<strong>of</strong> access to all levels <strong>of</strong> education and low levels<strong>of</strong> family support in any community are also closelylinked to both poverty and disability.Significant progress is being made in eliminating majorcauses <strong>of</strong> impairment such as iodine deficiencyand lack <strong>of</strong> access to safe water. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand,<strong>the</strong> last decade has seen a persistence or rise ino<strong>the</strong>r factors that have contributed to <strong>the</strong> incidence<strong>of</strong> impairments, including HIV/AIDS, environmentalpollution, accidents and drug abuse. 10 War and civilstrife are also major causes <strong>of</strong> impairment amongchildren, largely affecting countries in <strong>the</strong> developingworld. <strong>UNICEF</strong> has estimated that between 1990 and2001, 2 million children around <strong>the</strong> world were killedand as many as 6 million disabled by armed conflict. 11The prevention <strong>of</strong> disability caused by landmines andunexploded ordnance needs to be given higher priorityin <strong>the</strong> regions most affected.The additional burden placed on families <strong>with</strong> members,including children, <strong>with</strong> disabilities, deepens <strong>the</strong>impact <strong>of</strong> economic poverty and may fur<strong>the</strong>r perpetuatediscriminatory attitudes towards <strong>the</strong>se groups.In <strong>the</strong> light <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> inextricable link between povertyand disability, effective action to reduce poverty mustaddress disability concerns in a systematic manner. 12This fundamental principle <strong>of</strong> inclusive planning wasrecognized by former President <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World BankJames Wolfensohn:If development is about bringing excluded peopleinto society, <strong>the</strong>n disabled people belong inschools, legislatures, at work, on buses, at <strong>the</strong><strong>the</strong>atre and everywhere else that those who arenot disabled take for granted. Unless disabledpeople are brought into <strong>the</strong> development mainstream,it will be impossible to cut poverty in halfby 2015 or to give every girl and boy <strong>the</strong> chanceto achieve a primary education by <strong>the</strong> same dategoalsagreed by more than 180 world leaders at<strong>the</strong> United Nations Millennium Summit in September2000. 13The World Bank has promoted a broad and inclusiveapproach to disability issues, including through <strong>the</strong>appointment <strong>of</strong> an experienced disability adviser and<strong>the</strong> recruitment <strong>of</strong> disability experts. A guidance notereleased in 2007, which includes consideration <strong>of</strong>issues relevant to children and youth, has <strong>the</strong> aimto “assist Bank projects in better incorporating <strong>the</strong>needs and concerns <strong>of</strong> people <strong>with</strong> disabilities, aswell as integrating a disability perspective into ongoingsector and <strong>the</strong>matic work programs, and to adoptan integrated and inclusive approach to disability.” 14Similar initiatives, developed <strong>with</strong> non-governmentalorganizations (NGOs), are also being pursued by <strong>the</strong>European Union. 15Innocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>6

4 INTERNATIONALSTANDARDS ANDMECHANISMSOver four decades, <strong>the</strong> United Nations has made astrong commitment to <strong>the</strong> human rights <strong>of</strong> persons<strong>with</strong> disabilities. 16 This commitment has been reflectedin major human rights instruments as well as<strong>with</strong>in specific measures and initiatives, which began<strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1971 Declaration on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons<strong>with</strong> Mental Retardation and now has culminated in<strong>the</strong> 2006 Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong><strong>Disabilities</strong>. O<strong>the</strong>r examples <strong>of</strong> disability-focused initiativesinclude <strong>the</strong> International Decades <strong>of</strong> DisabledPersons, <strong>the</strong> 1993 Standard Rules on <strong>the</strong> Equalization<strong>of</strong> Opportunities for Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> and <strong>the</strong>1994 Salamanca Statement and Framework for Actionfor Special Needs Education (see box 4.1 for amore complete list).Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ChildThe 1989 Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child(CRC) is <strong>the</strong> first binding instrument in internationallaw to deal comprehensively <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> human rights<strong>of</strong> children, and is notable for <strong>the</strong> inclusion <strong>of</strong> an articlespecifically concerned <strong>with</strong> <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children<strong>with</strong> disabilities. The implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CRC ismonitored and promoted at <strong>the</strong> international level by<strong>the</strong> Committee on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child.The CRC identifies four general principles thatprovide <strong>the</strong> foundation for <strong>the</strong> realization <strong>of</strong> allo<strong>the</strong>r rights:• non-discrimination;• <strong>the</strong> best interests <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child;• survival and development;• respect for <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child.The principle <strong>of</strong> non-discrimination is reflectedin article 2 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CRC that expressly prohibitsdiscrimination on <strong>the</strong> grounds <strong>of</strong> disability:States parties shall respect and ensure <strong>the</strong> rightsset forth in <strong>the</strong> present Convention to each child...<strong>with</strong>out discrimination <strong>of</strong> any kind, irrespective<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child’s...disability...or o<strong>the</strong>r status.This principle is motivated by <strong>the</strong> recognition thatsegregated or separate facilities for education, healthcare, recreation and all o<strong>the</strong>r aspects <strong>of</strong> human lifeon <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> disability can create and consolidateexclusion. These factors <strong>of</strong>ten perpetuate <strong>the</strong>negative perception <strong>of</strong> a child <strong>with</strong> a disability asa ’problem’ and, in doing so, maintain or reinforcemechanisms <strong>of</strong> discrimination.Certain children require additional or different forms<strong>of</strong> support in order to enjoy <strong>the</strong>ir rights. For instance,a child <strong>with</strong> a visual impairment has <strong>the</strong> same rightto education as all children, but in order to enjoy thisright and to ensure her or his participation, <strong>the</strong> childmay require enlarged print, Braille books or o<strong>the</strong>rforms <strong>of</strong> assistance.Article 23 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> CRC refers to <strong>the</strong> obligations <strong>of</strong>States parties and recognizes that a child <strong>with</strong> mentalor physical disabilities is entitled to enjoy a full anddecent life, in conditions that ensure dignity, promoteself-reliance and facilitate <strong>the</strong> child’s active participationin <strong>the</strong> community:i) States parties recognize that a mentally or physi-cally disabled child should enjoy a full and decentlife, in conditions which ensure dignity, promoteself-reliance and facilitate <strong>the</strong> child’s active participationin <strong>the</strong> community.ii) States parties recognize <strong>the</strong> right <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disabledchildren to special care and shall encourage andensure <strong>the</strong> extension, subject to available resources,to <strong>the</strong> eligible child and those responsible forhis or her care, <strong>of</strong> assistance…appropriate to <strong>the</strong>child’s condition….iii) …assistance extended…shall be provided free<strong>of</strong> charge, whenever possible… and shall bedesigned to ensure that <strong>the</strong> disabled child haseffective access to and receives education, training,health care services, rehabilitation services,preparation for employment and recreation opportunitiesin a manner conducive to <strong>the</strong> child’sachieving <strong>the</strong> fullest possible social integrationand individual development, including his or hercultural and spiritual development.iv) States parties shall promote…<strong>the</strong> exchange <strong>of</strong>appropriate information in <strong>the</strong> field <strong>of</strong> preventivehealth care and <strong>of</strong> medical, psychological andfunctional treatment <strong>of</strong> disabled children…. In thisregard, particular account shall be taken <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>needs <strong>of</strong> developing countries.This special article on children <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesis included “<strong>with</strong>out prejudice to” <strong>the</strong> generalapplicability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> principles and provisions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>CRC to <strong>the</strong> situation <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities.The article adds force to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r provisions <strong>of</strong>7 <strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong> Innocenti Digest No. 13

Box 4.1 Human rights instruments and high-level decisions reinforcing <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> persons <strong>with</strong> disabilitiesComplementing <strong>the</strong> Universal Declaration <strong>of</strong> Human <strong>Rights</strong>, <strong>the</strong> International Covenant on Economic,Social and Cultural <strong>Rights</strong>, <strong>the</strong> International Covenant on Civil and Political <strong>Rights</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Conventionon <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, <strong>the</strong> following texts and international events specifically address <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong>persons <strong>with</strong> disabilities:1971 Declaration on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Mentally Retarded Persons stipulates that a person <strong>with</strong> an intellectualimpairment is accorded <strong>the</strong> same rights as any o<strong>the</strong>r person1975 Declaration on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons proclaims <strong>the</strong> equal civil and political rights <strong>of</strong> alldisabled persons, and sets standards for equal treatment and access to services1981 International Year <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons (United Nations)1982 World Programme <strong>of</strong> Action concerning Disabled Persons1983−1992 International Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons (United Nations)1990 World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic LearningNeeds adopted at <strong>the</strong> World Conference on Education for All, in Jomtien, Thailand in March1990, promotes “equal access to education to every category <strong>of</strong> disabled persons as an integralpart <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> education system”1993 United Nations Standard Rules on <strong>the</strong> Equalization <strong>of</strong> Opportunities for Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>provide detailed guidelines for policy development and implementation1993−2002 Asian and Pacific Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons1994 Salamanca Statement and <strong>the</strong> Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Adopted by<strong>the</strong> UNESCO World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Salamanca,Spain, 7-10 June 1994. Adopted by 92 governments and over 25 international organizations,putting <strong>the</strong> principle <strong>of</strong> inclusion on <strong>the</strong> educational agenda worldwide1995 World Summit for Social Development, Copenhagen Declaration and Programme <strong>of</strong> Actioncalls upon governments to ensure equal educational opportunities at all levels for disabled children,youth and adults, in integrated settings1998 Human <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>, Commission on Human <strong>Rights</strong> Resolution 1998/312000 World Education Forum, Dakar, Statement and Framework for Action established attainableand affordable educational goals, including <strong>the</strong> goals <strong>of</strong> ensuring that by 2015 all children <strong>of</strong>primary age have better access to complete free schooling <strong>of</strong> an acceptable quality, that genderdisparities in schooling are eliminated and that all aspects <strong>of</strong> educational quality are improved2000 Human <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>, Commission on Human <strong>Rights</strong> Resolution 2000/512001−2009 African Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons2002 UN General Assembly Resolution on The <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Child, following <strong>the</strong> World Summit on<strong>Children</strong>, calls upon States to take all necessary measures to ensure <strong>the</strong> full and equal enjoyment<strong>of</strong> all human rights and fundamental freedoms by children <strong>with</strong> disabilities, and to developand enforce legislation against <strong>the</strong>ir discrimination, so as to ensure dignity, promoteself-reliance and facilitate <strong>the</strong> child’s active participation in <strong>the</strong> community, including effectiveaccess to educational and health services2002 ’A World Fit for <strong>Children</strong>’, outcome document <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> UN General Assembly Special Session on<strong>Children</strong> makes clear reference to <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> children <strong>with</strong> disabilities, especially regardingprotection from discrimination, full access to services, and access to proper treatment and care,as well as <strong>the</strong> promotion <strong>of</strong> family-based care and appropriate support systems for families2003−2012 Second Asian and Pacific Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons2004−2013 Arab Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled Persons2006 UN Convention on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> Persons <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>2006−2016 Inter-American Decade <strong>of</strong> Disabled PersonsInnocenti Digest No. 13<strong>Promoting</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Children</strong> <strong>with</strong> <strong>Disabilities</strong>8