Fahrig, L. 2003. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity ...

Fahrig, L. 2003. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity ...

Fahrig, L. 2003. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

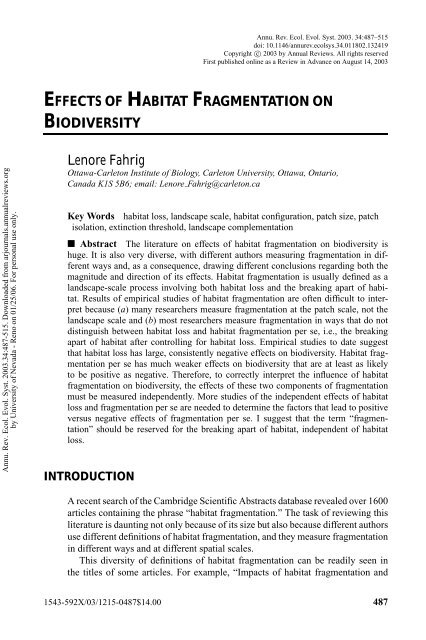

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 491Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.<strong>on</strong>ly two, i.e., <strong>on</strong>e c<strong>on</strong>tinuous landscape and <strong>on</strong>e fragmented landscape. With such adesign, inferences about the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> are weak. Apparent effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> could easily be due to other differences between the landscapes. Forexample, Mac Nally et al. (2000) found c<strong>on</strong>sistent vegetati<strong>on</strong> differences betweenfragments and reference sites and c<strong>on</strong>cluded that apparent effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><strong>on</strong> birds could be due to preexisting <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> differences between the two landscapes.Sec<strong>on</strong>d, this characterizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is strictly qualitative, i.e.,each landscape can be in <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two states, c<strong>on</strong>tinuous or fragmented. Thisdesign does not permit <strong>on</strong>e to study the relati<strong>on</strong>ship between the degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> and the magnitude <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <strong>biodiversity</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>se. Quantifying thedegree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> requires measuring the pattern <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the landscape.The diversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> approaches in the <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> literature arises mainlyfrom differences am<strong>on</strong>g researchers in how they quantify <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>.These differences have significant implicati<strong>on</strong>s for c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s about the effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>.Fragmentati<strong>on</strong> as Pattern: Quantitative C<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong>sThe definiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> above implies four effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> pattern: (a) reducti<strong>on</strong> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount, (b) increase innumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches, (c) decrease in sizes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches, and (d) increasein isolati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches. These four effects form the basis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> most quantitativemeasures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> measures vary widely;some include <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e effect (e.g., reduced <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount or reduced patch sizes),whereas others include two or three effects but not all four.Does it matter which <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> measure a researcher uses? The answerdepends <strong>on</strong> whether the different effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>pattern have the same effects <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. If they do, we can draw generalc<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s about the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> even though thedifferent studies making up the <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> literature measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>in different ways. As I show in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Habitat Fragmentati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Biodiversity,the different effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> pattern do not affect<strong>biodiversity</strong> in the same way. This has led to apparently c<strong>on</strong>tradictory c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>sabout the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. In this secti<strong>on</strong>, I review quantitativec<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. This is an important step towardrec<strong>on</strong>ciling these apparently c<strong>on</strong>tradictory results.FRAGMENTATION AS HABITAT LOSS The most obvious effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is the removal <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Figure 1). This has led many researchersto measure the degree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as simply the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>remaining <strong>on</strong> the landscape (e.g., Carls<strong>on</strong> & Hartman 2001, Fuller 2001, Golden& Crist 2000, Hargis et al. 1999, Robins<strong>on</strong> et al. 1995, Summerville & Crist 2001,Virgós 2001). If we can measure the level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>,why do we call it “<str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>”? Why not simply call it <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss? The

492 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.reas<strong>on</strong> is that when ecologists think <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, the word invokes more than<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> removal: “<str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> ... not <strong>on</strong>ly causes loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>,but by creating small, isolated patches it also changes the properties <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theremaining <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>” (van den Berg et al. 2001).Habitat can be removed from a landscape in many different ways, resulting inmany different spatial patterns (Figure 2). Do some patterns represent a higherdegree <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> than others, and does this have implicati<strong>on</strong>s for <strong>biodiversity</strong>?If the answer to either <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these questi<strong>on</strong>s is “no,” then the c<strong>on</strong>cept <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is redundant with <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss. The asserti<strong>on</strong> that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>means something more than <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss depends <strong>on</strong> the existence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> that can be attributed to changes in the pattern<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> that are independent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss. Therefore, many researchers define<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as an aspect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>.FRAGMENTATION AS A CHANGE IN HABITAT CONFIGURATION In additi<strong>on</strong> to loss<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>, the process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> results in three other effects: increasein number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches, decrease in patch sizes, and increase in isolati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches. Measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> that go bey<strong>on</strong>d simply <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount aregenerally derived from these or other str<strong>on</strong>gly related measures (e.g., amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>edge). There are at least 40 such measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> (McGarigal et al.2002), many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which typically have str<strong>on</strong>g relati<strong>on</strong>ships with the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>as well as with each other (Bélisle et al. 2001, Boulinier et al. 2001, Droletet al. 1999, Gustafs<strong>on</strong> 1998, Haines-Young & Chopping 1996, Hargis et al. 1998,Robins<strong>on</strong> et al. 1995, Schumaker 1996, Trzcinski et al. 1999, Wickham et al. 1999)(Figure 3).The interrelati<strong>on</strong>ships am<strong>on</strong>g measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> are not widely recognizedin the current <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> literature. Most researchers do not separate theeffects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss from the c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>al effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. This leadsto ambiguous c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s regarding the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>(e.g., Summerville & Crist 2001, Swens<strong>on</strong> & Franklin 2000). It is alsocomm<strong>on</strong> for <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> studies to report individual effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>measures without reporting the relati<strong>on</strong>ships am<strong>on</strong>g them, which again makes theresults difficult to interpret.THE PATCH-SCALE PROBLEM Similar problems arise when <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> is measuredat the patch scale rather than the landscape scale. Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> isa landscape-scale process (Figure 1), <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> measurements are correctlymade at the landscape scale (McGarigal & Cushman 2002). As pointed out byDelin & Andrén (1999), when a study is at the patch scale, the sample size atthe landscape scale is <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e, which means that landscape-scale inference isnot possible (Figure 4; see Brennan et al. 2002, Tischendorf & <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2000).However, in approximately 42% <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> recent <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> studies, individual datapoints represent measurements <strong>on</strong> individual patches, not landscapes (Table 1).Similarly, using a different sample <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the literature, McGarigal & Cushman (2002)

Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 493Figure 2 Illustrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss resulting in some, but not all, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the other threeexpected effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> landscape pattern. Expected effects are(a) an increase in the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches, (b) a decrease in mean patch size, and(c) an increase in mean patch isolati<strong>on</strong> (nearest neighbor distance). Actual changes areindicated by arrows.

Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.494 FAHRIGFigure 3 Illustrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the typical relati<strong>on</strong>ships between <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount and various measures<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. Individual data points corresp<strong>on</strong>d to individual landscapes. Based <strong>on</strong>relati<strong>on</strong>ships in Bélisle et al. (2001), Boulinier et al. (2001), Drolet et al. (1999), Gustafs<strong>on</strong>(1998), Haines-Young & Chopping (1996), Hargis et al. (1998), Robins<strong>on</strong> et al. (1995),Schumaker (1996), Trzcinski et al. (1999), and Wickham et al. (1999).

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 497Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.Figure 6 Landscape in southern Ontario (from Tischendorf 2001) showing that regi<strong>on</strong>swhere forest patches (black areas) are small typically corresp<strong>on</strong>d to regi<strong>on</strong>s where there islittle forest. Compare (A) and (B), where (A) has small patches and less than 5% forest and(B) has larger patches and approximately 50% forest.or “nearest-neighbor distance” (e.g., Delin & Andrén 1999, Haig et al. 2000, Hargiset al. 1999). Patches with small nearest-neighbor distances are typically situated inlandscapes c<strong>on</strong>taining more <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> than are patches with large nearest-neighbordistances (Figure 7), so in most situati<strong>on</strong>s this measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> isolati<strong>on</strong> is related to<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount in the landscape. Another comm<strong>on</strong> measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch isolati<strong>on</strong> isthe inverse <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> within some distance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the patch in questi<strong>on</strong>(e.g., Kinnunen et al. 1996, Magura et al. 2001, Miyashita et al. 1998). In otherwords, patch isolati<strong>on</strong> is measured as <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount at the landscape scale. Allother measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch isolati<strong>on</strong> are a combinati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> distances to other patchesand sizes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> those patches (or the populati<strong>on</strong>s they c<strong>on</strong>tain) in the surroundinglandscape (reviewed in Bender et al. 2003). As such they are all measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theamount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> in the surrounding landscape.

498 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.Figure 7 Illustrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the relati<strong>on</strong>ship between patch isolati<strong>on</strong> and amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> inthe landscape immediately surrounding the patch. Gray areas are forest. Isolated patches(black patches labeled “I”) are situated in landscapes (circles) c<strong>on</strong>taining less forest than areless isolated patches (black patches labeled “N”).MEASURING HABITAT FRAGMENTATION PER SE How can we measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>independent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount? Some researchers have c<strong>on</strong>structedlandscapes in which they experimentally c<strong>on</strong>trolled <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount while varying<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se (e.g., Caley et al. 2001, Collins & Barrett 1997).Researchers studying real landscapes have used statistical methods to c<strong>on</strong>trol for<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount. For example, McGarigal and McComb (1995) measured 25 landscapeindices for each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 30 landscapes. They statistically corrected each indexfor its relati<strong>on</strong>ship to <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount and then entered the corrected variablesinto a PCA. Each axis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the resulting PCA represented a different comp<strong>on</strong>ent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 499landscape c<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong>. In a similar approach, Villard et al. (1999) measured thenumber <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest patches, total length <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> edge, mean nearest-neighbor distance,and percent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest cover <strong>on</strong> each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> 33 landscapes. They used the residuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the statistical models relating each <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the first three variables to forest amountas measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> that have been c<strong>on</strong>trolled for their relati<strong>on</strong>ships to<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATIONON BIODIVERSITYIn this secti<strong>on</strong> I review the empirical evidence for effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g><strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. This review is not limited to the 100 papers summarized in Table1. The <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> literature can be distilled into two major effects: the generallystr<strong>on</strong>g negative effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>, and the much weaker,positive or negative effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. Because theeffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se is weaker than the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss, to detect theeffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se, the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss must be experimentally orstatistically c<strong>on</strong>trolled.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Habitat Loss <strong>on</strong> BiodiversityHabitat loss has large, c<strong>on</strong>sistently negative effects <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>, so researcherswho c<strong>on</strong>ceptualize and measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as equivalent to <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss typicallyc<strong>on</strong>clude that <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> has large negative effects. The negative effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss apply not <strong>on</strong>ly to direct measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>biodiversity</strong> such asspecies richness (Findlay & Houlahan 1997, Gurd et al. 2001, Schmiegelow&Mönkkönen 2002, Steffan-Dewenter et al. 2002, Wettstein & Schmid 1999),populati<strong>on</strong> abundance and distributi<strong>on</strong> (Best et al. 2001, Gibbs 1998, Gutheryet al. 2001, Hanski et al. 1996, Hargis et al. 1999, Hinsley et al. 1995, Lande1987, Sánchez-Zapata & Calvo 1999, Venier & <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1996) and genetic diversity(Gibbs 2001), but also to indirect measures <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>biodiversity</strong> and factors affecting<strong>biodiversity</strong>. A model by Bascompte et al. (2002) predicts a negative effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss <strong>on</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> growth rate. This is supported by D<strong>on</strong>ovan & Flather(2002), who found that species showing declining trends in global abundance aremore likely to occur in areas with high <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss than are species with increasingor stable trends. Habitat loss has been shown to reduce trophic chain length(Kom<strong>on</strong>en et al. 2000), to alter species interacti<strong>on</strong>s (Taylor & Merriam 1995),and to reduce the number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> specialist, large-bodied species (Gibbs & Stant<strong>on</strong>2001). Habitat loss also negatively affects breeding success (Kurki et al. 2000),dispersal success (Bélisle et al. 2001, Pither & Taylor 1998, With & Crist 1995,With & King 1999), predati<strong>on</strong> rate (Bergin et al. 2000, Hartley & Hunter 1998),and aspects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal behavior that affect foraging success rate (Mahan & Yahner1999).

500 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.INDIRECT EVIDENCE OF EFFECTS OF HABITAT LOSS Negative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>loss <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> are also evident from studies that measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amountindirectly, using measures that are highly correlated with <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount. For example,Robins<strong>on</strong> et al. (1995) found that reproductive success <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest nestingbird species was positively correlated with percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest cover, percentage<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest interior, and average patch size in a landscape. Because the latter twovariables were highly correlated with percentage <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest cover, these all representpositive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount <strong>on</strong> reproductive success. Boulinier et al.(2001) found effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mean patch size <strong>on</strong> species richness, local extincti<strong>on</strong> rate,and turnover rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest birds in 214 landscapes. Because mean patch size had a0.94 correlati<strong>on</strong> with forest amount in their study, this result most likely representsan effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount.Patch isolati<strong>on</strong> effects Patch isolati<strong>on</strong> is a measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the lack <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> in thelandscape surrounding the patch (Figure 7). Therefore, the many studies that haveshown negative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch isolati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> species richness or presence/absencerepresent further evidence for the str<strong>on</strong>g negative effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> landscape-scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>loss <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> (e.g., McCoy & Mushinsky 1999, Rukke 2000, Virgós 2001).Bender et al. (2003) and Tischendorf et al. (2003) c<strong>on</strong>ducted simulati<strong>on</strong> analysesto determine which patch isolati<strong>on</strong> measures are most str<strong>on</strong>gly related to movement<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> animals between patches. They found that the “buffer” measures, i.e., amount<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> within a given buffer around the patch, were best. This suggests a str<strong>on</strong>geffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount <strong>on</strong> interpatch movement. It also suggests, again, thateffects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch isolati<strong>on</strong> and landscape-scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount are equivalent.Patch size effects Individual species have minimum patch size requirements (e.g.,Diaz et al. 2000). Therefore, smaller patches generally c<strong>on</strong>tain fewer species thanlarger patches (Debinski & Holt 2000), and the set <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> species <strong>on</strong> smaller patchesis <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten a more-or-less predictable subset <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the species <strong>on</strong> larger patches (e.g.,Ganzhorn & Eisenbeiß 2001, Kolozsvary & Swihart 1999, Vallan 2000). Similarly,the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> a landscape required for species occurrence there differsam<strong>on</strong>g species (Gibbs 1998, Vance et al. 2003), so landscapes with less <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>should c<strong>on</strong>tain a subset <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the species found in landscapes with more <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>.Despite this apparent corresp<strong>on</strong>dence between patch- and landscape-scale effects,the landscape-scale interpretati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch size effects depends <strong>on</strong> the landscapec<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the patch. For example, D<strong>on</strong>ovan et al. (1995) found that forestbirds had lower reproductive rates in small patches than in large patches. If smallpatches occur in areas with less forest, the reduced reproductive rate may not bethe result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch size, but may result from larger populati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nest predatorsand brood parasites that occur in landscapes with more open <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Hartley &Hunter 1998, Robins<strong>on</strong> et al. 1995, Schmiegelow & Mönkkönen 2002).EXTINCTION THRESHOLD The number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> any species that a landscapecan support should be a positive functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> available to

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 501Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.Figure 8 Illustrati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold hypothesis in comparis<strong>on</strong> to theproporti<strong>on</strong>al area hypothesis.that species in the landscape. However, several theoretical studies suggest that therelati<strong>on</strong>ship is not proporti<strong>on</strong>al; they predict a threshold <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> level below whichthe populati<strong>on</strong> cannot sustain itself, termed the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold (Bascompte& Solé 1996, Boswell et al. 1998, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2001, Flather & Bevers 2002, Hill &Caswell 1999, Lande 1987, With & King 1999; Figure 8). There have been veryfew direct empirical tests <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold hypothesis (but see Janss<strong>on</strong>& Angelstam 1999).Note that the predicted occurrence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold results from <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>loss, not <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se. Theoretical studies suggest that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se can affect where the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold occurs <strong>on</strong> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>amount axis. Also, the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se are predicted toincrease below some level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss (see The 20–30% Threshold, below).However, the occurrence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the extincti<strong>on</strong> threshold is a resp<strong>on</strong>se to <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss,not <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se. This has led to some ambiguity in interpretati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> empiricalliterature. For example, Virgós (2001) found that patch isolati<strong>on</strong> affects badgerdensity <strong>on</strong>ly for patches in landscapes with

502 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.increase below a threshold amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> in the landscape. Because patch sizeand isolati<strong>on</strong> can be indicators <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount at a landscape scale (see Patchsize: An Ambiguous Measure <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fragmentati<strong>on</strong> and Patch Isolati<strong>on</strong>: A Measure<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Habitat Amount, above), this result could be interpreted as an intensificati<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss at low <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> levels, i.e., it supports the extincti<strong>on</strong>threshold hypothesis (Figure 8). This result has also been viewed as evidence forc<strong>on</strong>figurati<strong>on</strong> effects below a threshold <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> level (e.g., Flather & Bevers 2002,Villard et al. 1999). Again, the interpretati<strong>on</strong> is ambiguous because the relati<strong>on</strong>shipsbetween patch size and isolati<strong>on</strong> and amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> surrounding eachpatch were not c<strong>on</strong>trolled for.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Habitat Fragmentati<strong>on</strong> per se <strong>on</strong> BiodiversityIn this secti<strong>on</strong> I review the empirical evidence for <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> effects per se, i.e.,for effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> “breaking apart” <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>, that are independent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> orin additi<strong>on</strong> to the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss. The 17 studies in Table 2 represent all <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> theempirical studies <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> which I am aware. Some theoreticalstudies suggest that the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se is weak relative to theeffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss (Collingham & Huntley 2000, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1997, Flather & Bevers2002, Henein et al. 1998), although other modeling studies predict much largereffects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se (Boswell et al. 1998, Burkey 1999, Hill & Caswell1999, Urban & Keitt 2001, With & King 1999; reviewed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2002). All theserecent models predict negative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se, in c<strong>on</strong>trastwith some earlier theoretical work (see Reas<strong>on</strong>s for Positive <str<strong>on</strong>g>Effects</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fragmentati<strong>on</strong>,below). The empirical evidence to date suggests that the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>per se are generally much weaker than the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss. Unlike theeffects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss, and in c<strong>on</strong>trast to current theory, empirical studies suggestthat the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se are at least as likely to be positive as negative.The 17 empirical studies <strong>on</strong> the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se (Table 2)range from small-scale experimental studies to c<strong>on</strong>tinental-scale analyses. Theycover a range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resp<strong>on</strong>se variables, including abundance, density, distributi<strong>on</strong>,reproducti<strong>on</strong>, movement, and species richness. About half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the studies are <strong>on</strong>forest birds; other taxa include insects, small mammals, plants, aquatic invertebrates,and a virus, and other <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>s include grasslands, cropland, a coral reef,and an estuary.The 17 studies used a variety <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> approaches for estimating the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>per se. In five <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> them, experimental landscapes were c<strong>on</strong>structed toindependently c<strong>on</strong>trol the levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount and <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se. Four<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these varied both <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount and <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se, and <strong>on</strong>e varied <strong>on</strong>ly<str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>, holding the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>stant. Three <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 12 studies inreal landscapes compared the resp<strong>on</strong>se variable in <strong>on</strong>e large patch versus severalsmall patches (i.e., holding <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount c<strong>on</strong>stant). In the remaining nine studiesin real landscapes, the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se was estimated by statisticallyc<strong>on</strong>trolling for the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount.

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 503Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.TABLE 2 Summary <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> empirical studies that examined the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se, i.e., c<strong>on</strong>trolling for effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>amount <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>Directi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effect(s) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Relative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss versus <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong>Study Taxa and resp<strong>on</strong>se variable(s) <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>biodiversity</strong>Studies in real landscapesMiddlet<strong>on</strong> & Merriam 111 forest taxa (various): n.a. a No effect1983 distributi<strong>on</strong>McGarigal & McComb 15 late-seral forest bird Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 6 positive, 1 negative1995 species: abundanceMeyer et al. 1998 Northern spotted owl: Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> No effectpresence/absence,persistence, reproducti<strong>on</strong>Rosenberg et al. 1999 6 Tanager species and Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 negativepopulati<strong>on</strong>s: presence/absenceTrzcinski et al. 1999 31 forest bird species: Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 2 positive, 4 negativepresence/absenceDrolet et al. 1999 14 forest bird species: Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> No effectpresence/absenceVillard et al. 1999 15 forest bird species: Amount ∼ = <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 4 positive, 2 negativepresence/absenceBélisle et al. 2001 3 forest bird species: homing Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Positivetime and homing successLanglois et al. 2001 Hanta virus: incidence Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> Positive(C<strong>on</strong>tinued)

504 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.TABLE 2 (C<strong>on</strong>tinued)Directi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> effect(s) <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>Relative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss versus <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong>Study Taxa and resp<strong>on</strong>se variable(s) <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>biodiversity</strong>Hovel & Lipcius 2001 Blue crab: juvenile survival, n.a. a 1 positive (juvenileadult (predator) density survival),1 negative (adultdensity)Tscharntke et al. 2002 Butterflies: species richness, n.a. a 2 positive (totalendangered species richness and endangeredspecies richness)Flather et al. 1999 Forest birds: abundance Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> No effectStudies in experimental landscapes:Collins & Barrett 1997 Meadow vole: density n.a. a PositiveWolff et al. 1997 Gray-tailed vole: abundance, Fragmentati<strong>on</strong> > amount Positivedensity, reproductive rate,recruitmentCollinge & Forman 1998 Grassland insects: abundance, Not stated Positivespecies richnessCaley et al. 2001 8 coral commensals: species Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> 1 positiverichness and abundanceWith et al. 2002 Clover insects: spatial aggregati<strong>on</strong> Amount ≫ <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> n.a. ba Habitat amount was held c<strong>on</strong>stant; <strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> was varied.b Resp<strong>on</strong>se variable was spatial distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the insects.

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 505Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.The overall result from these studies is that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss has a much largereffect than <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> measures (Table 2). When<str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se did have an effect, it was at least as likely to be positiveas negative (Table 2). Given the relatively small number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> studies and the largevariati<strong>on</strong> in c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s am<strong>on</strong>g studies, it is not possible to tease apart the factorsthat lead to positive versus negative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se. However,the positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> can not be explained as merely resp<strong>on</strong>sesby “weedy,” <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> generalist species. For example, the results reported fromMcGarigal & McComb (1995) are specifically limited to late-seral forest species,and Tscharntke et al. (2002) found a positive effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong>butterfly species richness, even when they <strong>on</strong>ly included endangered butterflyspecies.THE 20–30% THRESHOLD Some theoretical studies suggest that the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>per se should become apparent <strong>on</strong>ly at low levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount,below approximately 20–30% <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> the landscape (<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 1998, Flather &Bevers 2002). To date, there is no c<strong>on</strong>vincing empirical evidence for this predicti<strong>on</strong>.If the threshold does occur, it should result in a statistical interacti<strong>on</strong> effect between<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount and <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se; such an interacti<strong>on</strong> wouldindicate that the effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se depends <strong>on</strong> the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>in the landscape. Trzcinski et al. (1999) tested for this interacti<strong>on</strong> effect but foundno evidence for it. The hypothesis that <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> effects increase below athreshold <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount has not yet been adequately tested.REASONS FOR NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF FRAGMENTATION PER SE Negative effects<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> are likely due to two main causes. First, <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per seimplies a larger number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> smaller patches. At some point, each patch <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>will be too small to sustain a local populati<strong>on</strong> or perhaps even an individualterritory. Species that are unable to cross the n<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> porti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the landscape(the “matrix”) will be c<strong>on</strong>fined to a large number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> too-small patches, ultimatelyreducing the overall populati<strong>on</strong> size and probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> persistence.The sec<strong>on</strong>d main cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> negative effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se is negativeedge effects; more fragmented landscapes c<strong>on</strong>tain more edge for a given amount<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>. This can increase the probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> individuals leaving the <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> andentering the matrix. Overall the amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time spent in the matrix will be largerin a more fragmented landscape, which may increase overall mortality rate andreduce overall reproductive rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the populati<strong>on</strong> (<str<strong>on</strong>g>Fahrig</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2002). In additi<strong>on</strong>, thereare negative edge effects due to species interacti<strong>on</strong>s. Probably the most extensivelystudied <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> these is increased predati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> forest birds at forest edges (Chalfounet al. 2002).REASONS FOR POSITIVE EFFECTS OF FRAGMENTATION PER SE More than half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se that have been documented are positive (Table 2).Some readers will find this surprising, probably because <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss is inextricably

506 FAHRIGAnnu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.included within their c<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>. In this case evenif <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se has a positive effect <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>, this effect will bemasked by the large negative effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss.Haila (2002) describes how the current c<strong>on</strong>cept <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> emergedfrom the theory <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> island biogeography (MacArthur & Wils<strong>on</strong> 1967). The twopredictor variables in this theory are island size and island isolati<strong>on</strong>, or distance<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the island from the mainland. When this theory was c<strong>on</strong>ceptually extendedfrom island archipelagos to terrestrial systems <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> patches, the c<strong>on</strong>cept<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> isolati<strong>on</strong> changed; isolati<strong>on</strong> was now the result <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss, and it representedthe distance from a patch to its neighbor(s), not the distance to a mainland.Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> its roots in island biogeography, isolati<strong>on</strong> was viewed as representing<str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> subdivisi<strong>on</strong> even though it was inextricably linked to <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>loss.However, a parallel research stream, which arose independently <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the theory<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> island biogeography, suggested that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> could have positiveeffects <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. Huffaker’s (1958) experiment suggested that subdivisi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>the same amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> into many smaller pieces can enhance the persistence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>a predator-prey system. He hypothesized that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> subdivisi<strong>on</strong> provides temporaryrefugia for the prey species, where they can increase in numbers and disperseelsewhere before the predator or parasite finds them. The plausibility <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this mechanismwas supported by early theoretical studies (Hastings 1977, Vandermeer 1973).Early theoretical studies also suggested that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> enhances thestability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two-species competiti<strong>on</strong> (Levin 1974, Shmida & Ellner 1984, Slatkin1974), and in an empirical study, Atkins<strong>on</strong> & Shorrocks (1981) found that coexistence<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> two competing species could be extended by dividing the <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> into more,smaller patches. Enhanced coexistence resulted from a trade-<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f between dispersalrate and competitive ability. This trade-<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f, al<strong>on</strong>g with asynchr<strong>on</strong>ous disturbancesthat locally removed the superior competitor, allowed the inferior competitor (butsuperior disperser) to col<strong>on</strong>ize the empty patches first, before being later displacedby the superior competitor (Chess<strong>on</strong> 1985). Other researchers suggested that <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>subdivisi<strong>on</strong> could even stabilize single-species populati<strong>on</strong> dynamics when localdisturbances are asynchr<strong>on</strong>ous by reducing the probability <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> simultaneous extincti<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the whole populati<strong>on</strong> (den Boer 1981; Reddingius & den Boer 1970; R<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f1974a,b).Why has this early work, suggesting positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> perse, been largely ignored in the more recent <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> literature? Onereas<strong>on</strong> is that later theoretical and empirical studies (reviewed in Kareiva 1990)dem<strong>on</strong>strated that the predicted positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se dependstr<strong>on</strong>gly <strong>on</strong> particular assumpti<strong>on</strong>s about the relative movement rates <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predatorversus prey (or host versus parasite), the trade-<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>f between competitive ability andmovement rate, and the asynchr<strong>on</strong>y <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> disturbances. It seems that the sensitivity tothese assumpti<strong>on</strong>s, al<strong>on</strong>g with the misrepresentati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> patch isolati<strong>on</strong> as a measure<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> subdivisi<strong>on</strong>, led researchers to ignore the possibility that <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g>per se could have a positive effect <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>.

EFFECTS OF HABITAT FRAGMENTATION 507Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. <str<strong>on</strong>g>2003.</str<strong>on</strong>g>34:487-515. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.orgby University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nevada - Reno <strong>on</strong> 01/25/06. For pers<strong>on</strong>al use <strong>on</strong>ly.There are at least four additi<strong>on</strong>al possible reas<strong>on</strong>s for positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong>. First, Bowman et al. (2002) argued that, formany species, immigrati<strong>on</strong> rate is a functi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the linear dimensi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>patch rather than the area <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> the patch. For these species, overall immigrati<strong>on</strong> rateshould be higher when the landscape is comprised <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a larger number <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> smallerpatches (higher <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se) than when it is comprised <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> a smaller number<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> larger patches. In situati<strong>on</strong>s where immigrati<strong>on</strong> is an important determinant<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> populati<strong>on</strong> density, this could result in a positive effect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se<strong>on</strong> density.Sec<strong>on</strong>d, if <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> amount is held c<strong>on</strong>stant, increasing <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per seactually implies smaller distances between patches (Figure 5). Therefore, a positiveeffect <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se could be due to a reducti<strong>on</strong> in patch isolati<strong>on</strong>.Third, many species require more than <strong>on</strong>e kind <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Law & Dickman1998). For example, immature insects and amphibians <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten use different <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>sthan those they use as adults. A successful life cycle requires that the adults canmove away from the <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> where they were reared to their adult <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>s and thenback to the immature <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> to lay eggs. The proximity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> different required <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>types will determine the ease with which individuals can move am<strong>on</strong>g them.For example, Pope et al. (2000) showed that the proximity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> feeding <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> tobreeding p<strong>on</strong>ds affected the abundance <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> leopard frog populati<strong>on</strong>s. Pedlar et al.(1997) found that racco<strong>on</strong> abundance was highest in landscapes with intermediateamounts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest. They suggested that this level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> forest maximized the accessibilityto the racco<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> both feeding areas (grain fields) and denning sites inforest.The degree to which landscape structure facilitates movement am<strong>on</strong>g differentrequired <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> types was labeled “landscape complementati<strong>on</strong>” by Dunning et al.(1992). For the same amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>, a more fragmented landscape (more,smaller patches, and more edge) will have a higher level <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> interdigitati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>different <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> types. This should increase landscape complementati<strong>on</strong>, whichhas a positive effect <strong>on</strong> <strong>biodiversity</strong> (Law & Dickman 1998, Tscharntke et al. 2002).Finally, it seems likely that positive edge effects are a factor. Some speciesdo show positive edge effects (Carls<strong>on</strong> & Hartman 2001, Kremsater & Bunnell1999, Laurance et al. 2001). For a given amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>, more fragmented landscapesc<strong>on</strong>tain more edge. Therefore, positive edge effects could be resp<strong>on</strong>siblefor positive effects <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> per se <strong>on</strong> abundance or distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> somespecies.CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONSHabitat Loss Versus Fragmentati<strong>on</strong>Most researchers view <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> as a process involving both the loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g> and the breaking apart <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>habitat</str<strong>on</strong>g>. The fact that most <str<strong>on</strong>g>fragmentati<strong>on</strong></str<strong>on</strong>g> researchdoes not differentiate between these two effects has led to several problems. First,