The Catawba Project

The Catawba Project

The Catawba Project

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

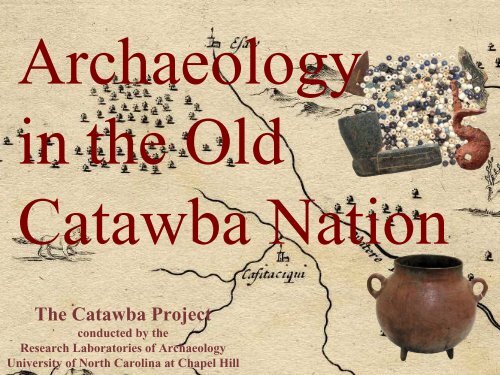

Archaeologyin the Old<strong>Catawba</strong> Nation<strong>The</strong> <strong>Catawba</strong> <strong>Project</strong>conducted by theResearch Laboratories of ArchaeologyUniversity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Because the locations of <strong>Catawba</strong> settlements shiftedthrough time, different areas of Lancaster and Yorkcounties provide archaeological information about specificperiods.Landsford to Long Island (Lancaster and York counties)1676–1715 Early English Contact PeriodNation Ford / Trading Path (York County)1716–1759 Coalescent PeriodPine Tree Hill (Kershaw County)/ Waxhaw Old Fields (Lancaster County)1760–1775 Late Colonial Period1776–1781 Revolutionary War Period1782–1820 Federal PeriodPresent Reservation Area (York County)1821–1840 Late Reservation Period

When John Lawson explored the interior of theCarolinas in 1701, he found numerous nativesocieties. Some, like the Sewee, Santee, andCongaree, had been devastated by Old Worlddiseases. Others, like the Wateree, Saponi, Tutelo,and Occaneechi, were displaced by warfare. Inthe lower <strong>Catawba</strong> River Valley, Lawsonencountered a powerful and vigorous alliance ofWaxhaw, Sugaree, Esaw and Kadapau towns.ca. 1700

By 1715, in the aftermath of the Tuscaroraand Yamassee wars, the piedmont regionwas largely vacant. Many of the formerpiedmont groups moved south to take refugewith the <strong>Catawba</strong> alliance. Others formednew coalescent centers with the Cheraw(formerly Saura) along the Pee Dee River orat Fort Christanna in Virginia.ca. 1715

<strong>The</strong> powerful native alliance that developed near NationFord, where the Great Trading Path crossed the <strong>Catawba</strong>River, gradually gelled by the mid-18 th century tobecome the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation.

Almost miraculously, the <strong>Catawba</strong>Nation has survived to the presentday within its ancient homeland,and is one of the few native nationsto occupy its original territory sinceEuropean contact .

One key to <strong>Catawba</strong> survival andsuccess during the colonial erawas early and constant militaryand economic alliance with theEnglish at Charles Town.<strong>Catawba</strong> warriors protected theCarolina colony from attacks byFrench-allied natives and acted asethnic soldiers for the English intheir frontier wars. In return,Charles Town granted favoredtrading status to the <strong>Catawba</strong>s,and supplied the nation with thefirearms, ammunition and othersupplies critical to its survival.

Another strategy that the<strong>Catawba</strong> Nation employedto build and maintain it’sstrength was incorporationsmall tribes displaced bydisease and warfare. Asearly as 1717, a Shawneeheadman commented on the<strong>Catawba</strong>s that “there aremany nations under thatname.”WaterieCharraWiapieNustieNasawSucca<strong>Catawba</strong> headman’s map ofthe <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation, 1721.About the year 1743, their nation consisted of almost 400 warriors, of above twentydifferent dialects. … the Katahba, is the standard, or court-dialect—the Wataree, whomake up a large town; Eeno, Chewah, [Cheraw] … Canggaree, Nachee, Yamasee,Coosah, &c. James Adair, 1775

During the French and Indian Wars (1754–1763), <strong>Catawba</strong> warriors supported South Carolinaand Virginia troops in campaigns in the Ohio country and Canada. In return, the coloniessupplied the <strong>Catawba</strong>s with essential goods; South Carolina even provisioned cattle and cornto <strong>Catawba</strong> towns when drought caused crop failures.

During the 1750s, Scots-Irish settlers flooded across <strong>Catawba</strong> territory, establishingcommunities on upper Sugar Creek (present-day Charlotte) and in “<strong>The</strong> Waxhaws.” <strong>The</strong>sewere lands that <strong>Catawba</strong> hunters claimed and used regularly, and friction quickly developedbetween the new settlers and Indians. Because alliance with the <strong>Catawba</strong>s was critical to thestrategic interests of the Carolinas, the colonial governments of North and South Carolinafrequently interceded on behalf of the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation, averting open hostilities with thenew settlers.

<strong>The</strong> Archaeology of mid-18 th century <strong>Catawba</strong>Life<strong>The</strong> archaeological record of mid-18 th century <strong>Catawba</strong> villages is concentrated near Nation Ford, atpresent-day Fort Mill, SC. John Evans’ 1756 map of the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation is a primary source for locatingand identifying these sites on the modern landscape. Other <strong>Catawba</strong> villages sites in this area (e.g.Spratt’s Bottom; Ann Springs Close Greenway site) pre-date the 1756 map.Locations from the 1756 Evansmap in present-day Fort Mill, SC.Nassaw &WeyapeeCharrawNoostee(?)John Evans map of the<strong>Catawba</strong> Nation, 1756.Nation FordWeyaneNationFordSucah

Distribution of mid-18 th centuryartifacts recovered in surveys ofNassaw and Weyapee (ca. 1750-1759)Archaeological investigations atthe paired villages of Nassaw andWeyapee (indicated on the Evansmap) reveal the character of thesemid-18 th century settlements. <strong>The</strong>distribution of artifacts identifiedby surveys indicate compact,nucleated villages, similar toWilliam Richardson’s 1756account of nearby Charraw as a“round town.” <strong>The</strong>se villageswere probably fortified withpalisade walls for defense againstraids by Shawnees, Senecas, andother <strong>Catawba</strong> enemies.

Archaeological investigations at Nassaw and Weyapee in2007 and 2008 revealed traces of houses and otherarchitecture and associated facilities such as food storagepits, pottery smudge pits, and graves. <strong>The</strong>se investigationsby UNC archaeological field schools providethe most detailed evidence of mid-18 th century <strong>Catawba</strong>life recovered to date.

Patterns of postholes at Nassaw indicate rectangularhouses built on earthfast post frameworks. <strong>The</strong>se wereprobably gable-end buildings that resembled theMenominee lodge above. Subfloor pits (shown inbrown) stored food and other household goods.

Most houses at Nassaw included small, deeprectangular storage pits.Posthole with flintlock pistol barrel inserted aspost wedge.Many pits were filled with household garbageafter they deteriorated and were no longeruseful for storage.Smudge pits with charred corncobs and kernalswere used to smoke the interiors of potteryvessels as a means of waterproofing low-firedearthenware.

Much of the household refuse recovered from Nassaw and Weyapee was fragments of native potteryvessels, like these sections of large cooking jars. <strong>The</strong> style of pottery at these sites resembles that madein the <strong>Catawba</strong> River Valley for several hundred years previous, and differs markedly from <strong>Catawba</strong>pottery made after 1760.

Incised Bowl DecorationsFolded & Notched RimsCord-marked Jar FragmentsPottery from Nassaw and WeyapeeCarved Paddle Stamped Jar Fragments

Trade Goods from Nassaw and WeyapeeWine bottle necks<strong>Catawba</strong> families at Nassaw and Weyapee acquired much of their “hardware” for dailylife through trade with itinerant British merchants, or via diplomatic gifts from the SouthCarolina colonial government. <strong>Catawba</strong> towns participated in a vigorous deerskin trade asearly as the 1670s, and were quickly engaged within a growing global economy thatshipped raw leather to Britain and cheap manufactured goods to the Carolina interior.

Nassaw and Weyapee yielded thousands of glass beads once used for personalornamentation. Most of these are embroidery beads used on clothing, sashes,garters, and other accoutrements. Many of these beads came from Venetianglassworks via the great trading houses of London and Glasgow, then throughfactors (merchants) in Charles Town before being hauled with other goods bypackhorses to the <strong>Catawba</strong> towns.

Brass kettles, represented at Nassaw and Weyapee by cut andrecycled sheet brass and cast bronze lugs, were highly prized bynative and European cooks alike. In 1718, a single brass kettlebrought 10 deerskins in the South Carolina trade.

Abundant gunparts and ammunition recovered from Nassaw and Weyapee indicate that<strong>Catawba</strong> warriors and hunters were well armed and heavily militarized, a function ofthe nation’s close alliance with the British in the French and Indian War.

A Scottish dirk blade from aWeyapee pit may reflect<strong>Catawba</strong> warriors’association with Highlandregiments in the Canadiancampaigns during the Frenchand Indian War.

Cherokee carvedstone tobacco pipesEnglish manufacturedkaolin tobacco pipes<strong>Catawba</strong> calumet styleclay tobacco pipes<strong>Catawba</strong> elbow styleclay tobacco pipeCarved stone and ceramic tobacco pipes are numerous at Nassaw and Weyapee. Some of thestone pipes closely resemble Cherokee pipes from the 1750s, and are carved from stone fromthe southern Appalachians. Long stemmed kaolin pipes came from Charles Town traders,who also brought Virginia tobacco (processed in Glasgow factories) to the <strong>Catawba</strong> towns.

<strong>The</strong> demise of Nassaw, Weyapee, and the other towns at Nation Ford was anunexpected outcome of <strong>Catawba</strong> involvement in the French and Indian War. <strong>Catawba</strong>warriors were present at the siege of Quebec and at the battle on the Plains of Abrahamin September 1759. After the fall of Quebec, warriors returning home contractedsmallpox in Pennsylvania and brought the contagion to their homes at Nation Ford.Within three months, half of the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation had perished and the remnantscattered.<strong>The</strong> Death of General Wolfe at Quebec

1759 1762<strong>The</strong> devastating smallpox epidemic of 1759drove the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation to disperse to breakthe cycle of contagion and death. <strong>The</strong> remnantsof the nation regrouped under Englishprotection at Pine Tree Hill (Camden) in 1760.By 1762, most of the nation had returned to itsold territory to form new towns near TwelveMile Creek (present-day Lancaster County).1760

Late Colonial Period (1760–1775)In the late Colonial Period,<strong>Catawba</strong> leaders negotiatedwith Crown officials tosecure title within a definedboundary to protect their coreterritory from encroachingsettlers. This boundary,surveyed in 1763, is partiallypreserved in the NC–SC stateline.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Catawba</strong> Lands are a veryfine body, it's a square of 14½miles, they occupy but a verysmall part, their Town is builtup in a very close manner andthe field that they plant doesnot exceed 100 acres…Wm. Moultrie, 1772Capt.Redhead,<strong>Catawba</strong>leader, 1772

Samuel Wyly’s 1763 survey of the landsreserved to the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation indicates thelocations of two towns. <strong>The</strong> town at TwelveMile Creek included a fort built by SouthCarolina. <strong>The</strong> northern settlement, now calledthe Old Town Site, was King Haigler’s village.OldTown

<strong>Catawba</strong> Old Town(ca. 1762–1780, 1781–1800)Lancaster County, South CarolinaArchaeologists located the Old Town Site, seat of one of the<strong>Catawba</strong> villages depicted on the 1763 Wyly map, in 2003.Investigations here recovered evidence of two occupationepisodes, ca. 1762–1780 and ca. 1781–1800, with a briefabandonment of the town due to the British invasion of 1780.Old Town

<strong>The</strong> 2003 investigations at Old Townuncovered a series of pits features, smallcellars that were once beneath <strong>Catawba</strong>log cabins, similar to the dwellings ofthe <strong>Catawba</strong>s’ Scots Irish neighbors.

XXX<strong>Catawba</strong> Old TownPhotographic Mosaic of2003 Excavationone meterXExcavation PlanXXXCellar Pit (Feature 7) Cellar Pit (Feature 2) Shallow Pit (Feature 1)

pedestal bases & foot ringspedestal basered-painted pan rimpolished bowlfragmentsblack-painted English-style plate<strong>Catawba</strong> Earthenware from Old TownPits at Old Town yielded pottery that isradically different from the Nassawand Weyapee wares. <strong>The</strong> plain andpolished pottery from Old Townrepresents English pottery forms.<strong>Catawba</strong> potters may have adoptedthese forms and finishes while thenation was at Camden, 1760–1761.

English ceramics from Old Town include fragments of an Englishporcelain punch bowl and stoneware cups.

ulletmoldlead shotGunparts and ammunitionfrom Old Town indicate that<strong>Catawba</strong> hunters andwarriors abandoned cheaptrade muskets in favor ofstate of the art rifles made inthe American backcountry.gunflintsriflebuttplate

1769English George III halfpennies from Old Town may reflectuse of currency in the <strong>Catawba</strong>s’ regular interactions withScots-Irish neighbors in the nearby Waxhaws settlements.

ass tinkler conesglass beadscufflinkssilver nose banglesPersonal ornaments from Old Town indicate continued use of commerciallymanufactured goods to produce native costume and project native identity.<strong>The</strong> small triangular nose bangles (lower right) were part of a native fashionwave that swept eastern North America in the 1770s.

Revolutionary War Period (1776–1781)During the American Revolution, the<strong>Catawba</strong>s sided with their Whigneighbors, and served with Americanforces from 1775 until 1781. Thissmall Indian nation boasted thehighest per capita rate of service ofany community in the colonies.<strong>The</strong> day after Lord Rawdon reachedWaxhaw, he with a life guard of twentycavalry, visited the <strong>Catawba</strong> Indiantowns, six or eight miles distance fromhis encampment. <strong>The</strong>se towns aresituated above the mouth of TwelveMile Creek, on the east bank of the<strong>Catawba</strong> River.Graham, 1827Mouzon Map,1775<strong>The</strong> advance of Lord Cornwallis’ army in 1780 drove the <strong>Catawba</strong>s from their homes,and the nation took refuge in Virginia. When they returned in 1781, they rebuilt theirhomes at Old Town.

2009 investigations at Old Town revealed evidence of the reoccupation of the village afterthe American Revolution

Here, students and their instructors clean the surface of <strong>Catawba</strong> storage pits at Old Town.

<strong>The</strong>se excavations revealed multiplesubfloor cellars that indicate repeatedhouse rebuilding.basincellar pitbasincellar pitcellar pitPhotographic Mosaic of 2009 Excavation

Investigations at Old Town also revealed a series of coffinburials. <strong>The</strong>se graves were mapped and documented, but were notexcavated.

Extent of 2003 and 2009 excavations at Old Town

pistol barrelrawpotter’sclayceramic panfragmentsdeer antler tineLate 18 th century pits at Old Town closely resemble food storage cellars documentedin European and African cabin contexts in the Carolinas. After the pits were no longerused for food storage, villagers dumped household refuse to fill the empty holes.

<strong>Catawba</strong>pan fragmentsred sealing wax usedto paint potteryraw pottery claybronze jew’sharp frameOld Town pits yielded abundant evidence of pottery production for the growingceramic trade with European settlers.

New Town (1800–1820)By the beginning of the 19 thcentury, the <strong>Catawba</strong> communityhad shifted to anupland ridge about a milenorth of the Old Town site.<strong>The</strong> community at thislocation was known at thetime as New Town. <strong>The</strong> NewTown community (about 200individuals) was largelydependent on leasing the<strong>Catawba</strong>s’ reserved lands andon the production and sale ofpottery for their livelihood.<strong>The</strong>ir Nation is reduced to a verysmall number, and [they] chieflylive in a little town, which inEngland would be only called avillage.Rev. Thomas Coke 1791Price-StrothersMap 1808New Town

<strong>Catawba</strong> Land Leases“<strong>The</strong>se lands are almostall leased out to whitesettlers, for 99 years,renewable, at the rateof from 15 to $20 perannum for eachplantation, of about 300acres.”Robert Mills 1826Plats of Leased Lands in the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation

Systematic metal detectionsurveys at New Townidentified seven clusters ofFederal period metal artifactsthat correspond to thelocations of individualcabins or small groups ofcabins. This pattern ofdispersed cabins correspondsto Calvin Jones’ 1815account of New Town as “6or 8 houses facing an oblongsquare,” along with thenearby homes of Sally NewRiver and Col. Jacob AyresLocus 3Locus 2Locus 6Locus 5Locus 1Locus 7NCabin Loci atNew Town- Metal Detected ArtifactLocus 4

Cabin Outline (est.)Tree DisturbanceSmall PitChimney BaseTroweling Top of SubsoilCellarCellar (partly excavated)Excavations at Locus 2 revealed the remainsof a dirt-floored cabin with a stick-and-claychimney and a subfloor cellar.one one meter meterPhotographic Mosaic of Excavation

Excavations at Loci 4 and 5revealed remants of cabins withpierstones and elevated hearths,indicating raised floors. In 1815,Calvin Jones observed that“[Sally] New Rivers and [Jacob]Airs (Ayers) houses had floors -all have chimneys.” Locus 4 isprovisionally identified as thehome of Sally New River, thefirst house that Jones encounteredas he approached New Townfrom the Waxhaws area. Thisarea included two cabin seatsmarked by chimney mounds,associated refuse deposits, andfeatures such as a wagon roadand foot path that date to theNew Town occupation.

Elevated chimney bases at Loci 4and 5 are the remains of earth-filledfireboxes with elevated hearths atthe level of raised wooden cabinfloors. <strong>The</strong>se cabins probablyresembled the housing of many ofthe <strong>Catawba</strong>s’ white neighbors.Other dirt floored cabins at NewTown were like the homes that<strong>Catawba</strong> informants describe toFrank Speck:<strong>The</strong> <strong>Catawba</strong> house, of as early a type ascould be remembered by any of the olderpeople in their childhood, was a smallstructure of either plain unbarked, or of peeledand roughly squared logs. From the smallestof these houses twelve by eighteen feet indimension intended for one small family, theyranged to those seldom more than six feetlarger in mean measurements. Lackingwindows, having only a door at the leewardend, with hard trodden dirt floors, they had afireplace at one end, of stone construction,and slat bedsteads on the long sides toaccommodate the sleepers. Such homes wereto be seen until lately.Locus 4 (Sally New River Cabin(?)) chimney baseSchematic cutaway view of awooden earth-filled firebox

Snaffle BitsHorseshoeHarness RingSingletree Clips & ChainStirrupHarness BuckleRiding and draft hardware is especially prominent at New Town, consistent with theimportance of horses as the <strong>Catawba</strong>s’ primary form of wealth, and the role of horses astransportation as the <strong>Catawba</strong>s pursued the itinerant pottery trade.

pistol lockgunflintsbrass escutcheonlead ballbrass buttplateGun parts and ammunition are much less common at New Town than at Nassaw or OldTown, a pattern that reflects the reduced roles of hunting and warfare for <strong>Catawba</strong>s inthe early 19 th century.

Almost all the men and women wore silver nose-rings, hangingfrom the middle gristle of the nose; and some of them had littlesilver hearts hanging from the rings…. In general they dressedlike the white people. But a few of the men were quiteluxurious in their dress, even wearing ruffles, and very showysuits of clothes made of cotton. Thomas Coke, 1791Coke’s account of western dress mixed with nativeornamentation among the <strong>Catawba</strong>s is born out bynumerous brass buttons and other clothing hardwarefound alongside silver earbobs, nose bangles, and glassbeads.

English hand-painted pearlwareNew Town kitchens andtables were well stocked withcommercial goods purchasedfrom local stores. <strong>The</strong>sewares may reflect adoption ofwestern foodways and diningpractice by <strong>Catawba</strong> families.English shell-edged pearlware, transfer- printedpearlware, and creamwareGlass stoppers and container fragmentsCast iron kettle fragment

Sally New River’smilkpan, New TownFragments of <strong>Catawba</strong>-made ceramic vessels are the most prevalent artifacts at New Town. <strong>The</strong>potters of New Town made wares for their own use, but also built thousands of vessels for sale ortrade on South Carolina’s plantations. When Jones visited New Town in 1815, he saw: “Womenmaking pans - Clay from the river - shape them with theirhands and burn them with bark which makesthe exposed side a glossy black. A pitcher a quarter of a dollar. Sell pans frequently for the full[measure] of meal. Saw some sitting on their beds and making pans.”

Red-Painted Rim & Body SherdsCup Bottle Lid HandlePlate RimsHandle AttachmentJar HandlesBowl RimsFooted (Pedestaled) Bowl BasesBowl & Cup Foot RingsStraight Pan RimsBowl or Cup RimFlat Bowl & Pan BasesChamber Pot RimsFolded or Thickened Jar RimsSmudged Pan InteriorContexts at New Town yielded more than 62,000 ceramic fragments that represent a wide range ofvessel forms. <strong>The</strong>se wares are plain or burnished; some are decorated with highlights of red sealing wax.

New Town vessels include flat-bottomed milkpan, cups and bowls with footrings,soup plates, jars, and pipkins. With the exception of cooking jars with thickenedrims, these forms derive from European vessels, and reflect <strong>Catawba</strong> potters’efforts to meet market demands.

<strong>Catawba</strong> potters traveled from New Town to build and sell their wares on plantationsand in towns throughout South Carolina. This itinerant trade supplied much neededincome for <strong>Catawba</strong> families, and regularly renewed the <strong>Catawba</strong>s’ political ties withCarolina’s elites.“… it was the custom of the <strong>Catawba</strong>Indians … to come down, at certainseasons, from their far homes in theinterior, to the seaboard, bringing toCharleston a little stock of earthenpots and pans … which they barteredin the city ….<strong>The</strong>y did not, however, bring theirpots and pans from the nation, butdescending to the Lowcountry emptyhanded, in groups or families, theysquatted down on the rich clay landsalong the Edisto, … there establishedthemselves in a temporary abidingplace, until their simple potteries hadyielded them a sufficient supply ofwares with which to throw themselvesinto the market.”William Gilmore Simms, 1841Rachael Brown<strong>Catawba</strong> potter,1907

Late Reservation Period (1821–1840)<strong>Catawba</strong> families abandoned NewTown after the death of SallyNew River (ca. 1820) and movedacross to the river to join theremainder of the <strong>Catawba</strong>community. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Catawba</strong> Nationmaintained it’s reserve until 1840,when leaders signed the Treaty ofNation Ford and ceded the tribe’slands to the state of SouthCarolina. Most of the communitythen moved to join the EasternBand Cherokees in NorthCarolina, but returned in the late1840s to the old <strong>Catawba</strong>homelandsDrayton Map, 1822

Strategies that enabled the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation to survive andadapt to the rapidly changing political, economic, andsocial conditions in the post-contact era from 1700 to 1840include:• multi-ethnic coalescence• militarization• territorial management• cottage industries• itinerancy to accesseconomic & politicalresourcesMargaret Brown Burnishing Pot, 1913

<strong>Catawba</strong> children screening Nassaw feature soils,2007Today, the <strong>Catawba</strong> Nation still thrives within it’s ancient territory. <strong>The</strong> UNC <strong>Catawba</strong><strong>Project</strong>, in cooperation with the <strong>Catawba</strong> Indian Nation cultural preservation program, iscommitted to bringing to light evidence of the nation’s rich history for the benefit ofpresent and future generations of <strong>Catawba</strong> people.

Unfortunately, this rich heritage is imminently threatened by rapid commercial andresidential development in the Fort Mill and Indian Land areas. Private developmentthat is not subject to federal review and compliance has already destroyed a numberof important <strong>Catawba</strong> sites.<strong>The</strong> Bowers Site (38La483), an early 19 th -Century <strong>Catawba</strong> cabin. Surrounding cabinseats were recently destroyed by development of a subdivision and golf course.

Each site that is destroyed is like a one-of-a-kind rare book of irreplaceableinformation taken from the library—and gone forever.Early 18 th -century <strong>Catawba</strong> sites along Sugar Creek destroyed by cut-and-fill for a housingdevelopment.

<strong>The</strong> problem of site destruction is exacerbated by the phenomenal expansion of theCharlotte Metro area. <strong>Catawba</strong> sites of the 18 th and 19 th centuries are a finite set, andmore than one-third of these sites have been destroyed in the past decade.Site 38Yk435, an early 18 th -Century Village along the Trading Path, largely obliterated byrecent development.

Growth in York and Lancaster counties is inevitable, but measures (e.g., conservationeasements via land trusts) can be taken to preserve important historic and archaeologicalproperties such as the <strong>Catawba</strong> village sites. In instances where preservation is notpossible, every effort should be made to recover valuable heritage information before it isirrevocably lost.Site 38La125, vicinity of one (of two) <strong>Catawba</strong> towns and South Carolina fort depicted on 1763 SamuelWyly Map, has been heavily damaged by clay digging operations to produce bricks for the building boom.