Early Termination and Liquidation Provisions in Energy Trading and ...

Early Termination and Liquidation Provisions in Energy Trading and ...

Early Termination and Liquidation Provisions in Energy Trading and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Early</strong> <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Liquidation</strong> <strong>Provisions</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Energy</strong> Trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Market<strong>in</strong>g AgreementsCraig R. EnochsFundi A. MwambaPaul E. VranaJackson Walker L.L.P.1401 McK<strong>in</strong>ney, Suite 1900Houston, Texas 77081Fax: 713-752-4221Telephone: 713-752-4315South Texas College of LawPOWER INSTITUTEJune 5-6, 2003

Table of ContentsI. Master Agreements <strong>in</strong> General..............................................................................................................1A. Remedies found <strong>in</strong> master agreements.............................................................................................1B. Liquidated damages compared to early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rights........................................1II. Summary of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Liquidation</strong> Clauses .....................................................................2A. History of clauses <strong>in</strong> relation to master agreements .........................................................................2B. Events of default .............................................................................................................................2C. <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> events..........................................................................................................................2D. Summary of the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation remedy...............................................................2E. Summary of liquidation...................................................................................................................3F. Summary of setoff...........................................................................................................................3III. Mechanics of Procedure.....................................................................................................................3A. Events of default.............................................................................................................................31. New events of default..............................................................................................................3B. Notice of an event of default <strong>and</strong> early term<strong>in</strong>ation date ..................................................................5C. Election of remedy..........................................................................................................................51. Cherry-pick<strong>in</strong>g transactions to term<strong>in</strong>ate .................................................................................52. Non-exclusive nature ..............................................................................................................5D. <strong>Liquidation</strong> .....................................................................................................................................61. Market quotation versus loss ...................................................................................................62. Net present value ....................................................................................................................73. Disputed valuations.................................................................................................................74. One-way versus two-way payment ..........................................................................................7E. Setoff ..............................................................................................................................................81. In general................................................................................................................................82. Cross-product setoff................................................................................................................83. Cross-party setoff....................................................................................................................94. Setoff of collateral ..................................................................................................................9IV. Bankruptcy ........................................................................................................................................9A. In general........................................................................................................................................9B. Automatic stay..............................................................................................................................101. Exemptions from the automatic stay......................................................................................10a. Forward contracts <strong>and</strong> swap agreements def<strong>in</strong>ed ...............................................................10b. Importance of exemptions from the automatic stay............................................................11C. Avoidance action claims ...............................................................................................................111. Preferences <strong>and</strong> fraudulent transfers ......................................................................................12a. Types of fraudulent transfers.............................................................................................12b. In re Olympic Natural Gas Company ................................................................................12c. Avoidance actions <strong>and</strong> swap agreements ...........................................................................12D. Ipso facto provisions.....................................................................................................................13V. Conclusion........................................................................................................................................13i

I. Master Agreements <strong>in</strong> GeneralThe term “master agreement” generally means an agreement, often st<strong>and</strong>ardized for a commodity, with terms<strong>and</strong> conditions that will apply to multiple transactions, each evidenced by a brief transaction confirmation.Master agreements can be used for physically-delivered commodities or over-the-counter derivativetransactions. 1 St<strong>and</strong>ardized master agreements are commonly used to manage the risks associated withenergy trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g transactions. Recent history demonstrates that such risks are numerous <strong>and</strong>substantial <strong>and</strong> can be costly if left unmitigated. Several events, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Enron’s bankruptcy, 2 the recent<strong>and</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g credit rat<strong>in</strong>g downgrades of some of the <strong>in</strong>dustry’s largest energy trad<strong>in</strong>g companies, <strong>and</strong> thesubsequent exit from the <strong>in</strong>dustry of some of those companies, 3 have dramatically changed the way manyenergy trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g companies view, measure <strong>and</strong> mitigate credit risk. This change <strong>in</strong> perspectiveis caus<strong>in</strong>g companies to re-exam<strong>in</strong>e master agreements to take advantage of some of the hard lessons learned<strong>in</strong> the months follow<strong>in</strong>g Enron’s bankruptcy fil<strong>in</strong>g. In addition, non-traditional participants are enter<strong>in</strong>g themarket <strong>and</strong> br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g with them new ideas concern<strong>in</strong>g credit <strong>and</strong> risk management. Although parties apply it<strong>in</strong> different ways, the most common type of contractual provision used to manage credit risk <strong>in</strong> masteragreements is the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provision. This paper analyzes the contents, mechanics<strong>and</strong> implications of early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions commonly used <strong>in</strong> master agreements.A. Remedies found <strong>in</strong> master agreementsMaster agreements typically conta<strong>in</strong> two types of remedies for the breach<strong>in</strong>g party’s nonperformance:liquidated damages <strong>and</strong> early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation. Upon a party’s breach of its obligation to deliver orreceive a commodity under a master agreement, the non-breach<strong>in</strong>g party is usually entitled to recoverliquidated damages. 4 Liquidated damages can be calculated us<strong>in</strong>g the cover st<strong>and</strong>ard, which provides for therecovery of the difference between the contract price <strong>and</strong> the market price to purchase substitute quantities ofthe commodity, 5 or the spot st<strong>and</strong>ard, which is calculated by subtract<strong>in</strong>g the contract price from either themarket price quoted by <strong>in</strong>dependent market participants or a published, <strong>in</strong>dex price. 6 While these liquidateddamages typically <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>cremental costs <strong>in</strong>curred as a result of the breach <strong>and</strong> the subsequent cover<strong>in</strong>gprocess, such as imbalance penalties or additional transmission costs, 7 they exclude other costs, such asadm<strong>in</strong>istrative costs <strong>in</strong>curred <strong>in</strong> replac<strong>in</strong>g the transaction. 8 Upon an event of default, term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong>liquidation provisions def<strong>in</strong>e the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s rights under the master agreement. Events of defaultare carefully def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> master agreements but usually <strong>in</strong>clude any significant breach other than those relatedto the failure to deliver or receive a physical commodity.B. Liquidated damages compared to early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rightsLiquidated damages <strong>and</strong> early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation differ <strong>in</strong> several material respects. Liquidateddamages are usually the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s sole <strong>and</strong> exclusive remedy for the other party’s failure toperform its obligations to deliver or receive the energy commodity under a master agreement between theparties. As a result, the payment by the default<strong>in</strong>g party of the liquidated damages prevents an event ofdefault under the agreement <strong>and</strong> the affected transactions <strong>and</strong> the master agreement cont<strong>in</strong>ues <strong>in</strong> full force <strong>and</strong>effect. Industry participants typically treat liquidated damages as a rout<strong>in</strong>e occurrence <strong>and</strong> envision thecont<strong>in</strong>uation of the master agreement <strong>and</strong> the transaction despite the failure that caused the liquidateddamages.In contrast, early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rights arise when there has been an occurrence, other than afailure to deliver or receive a commodity, that has global implications upon performance under the masteragreement <strong>and</strong>/or the f<strong>in</strong>ancial obligations of the parties. These occurrences typically relate to the credit,payment history, <strong>and</strong>/or solvency of the default<strong>in</strong>g party. The broad scope of events of default can cause theiroccurrence under one agreement to create early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rights under another agreement.Likewise, a failure on the part of or action of a guarantor or affiliate of a party to a master agreement can alsoconstitute an event of default. Upon an event of default, early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions usuallyprovide a number of rights to the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: (i) the right to term<strong>in</strong>ate all outst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gtransactions under a master agreement; (ii) the right to liquidate the term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions; (iii) the right to1

setoff amounts due under such transactions <strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> some cases, across master agreements <strong>and</strong> across affiliates;<strong>and</strong> (iv) the right to suspend payment <strong>and</strong>/or performance obligations under the master agreement. 9 Theexercise of a party’s rights under term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions causes the cessation of, at am<strong>in</strong>imum, the term<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>and</strong> liquidated transaction(s), <strong>and</strong> usually the entire master agreement <strong>and</strong> alltransactions thereunder.II.Summary of <strong>Early</strong> <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Liquidation</strong> ClausesA. History of clauses <strong>in</strong> relation to master agreements<strong>Early</strong> master agreements for physical energy transactions did not conta<strong>in</strong> early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidationprovisions. These provisions were orig<strong>in</strong>ally only found <strong>in</strong> the ISDA master agreement, 10 which the energymarkets began to use <strong>in</strong> the late 1980’s to document <strong>in</strong>terest rate <strong>and</strong> currency swap transactions. 11 Dur<strong>in</strong>gthe 1990’s, as physical energy market participants became more sophisticated <strong>in</strong> the manner <strong>in</strong> which risk wasmeasured <strong>and</strong> controlled, exist<strong>in</strong>g master agreements were amended <strong>and</strong> new master agreements were draftedto <strong>in</strong>clude term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions. 12 Today, early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions arenearly ubiquitous <strong>and</strong> may be found <strong>in</strong> a master agreement, <strong>in</strong> an overly<strong>in</strong>g agreement, such as a masternett<strong>in</strong>g agreement, or an underly<strong>in</strong>g agreement, such as a transaction confirmation.B. Events of default<strong>Early</strong> term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rights are triggered by the occurrence of events of default. Becauseterm<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation is a severe remedy which should be available only <strong>in</strong> extreme cases, parties shoulduse great care to select <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>e the circumstances that constitute events of default. An event of default isusually an objective occurrence such as a bankruptcy fil<strong>in</strong>g or the failure to provide collateral when requested,<strong>and</strong> as a result, there is typically little right to dispute the existence of an event of default. Once an event ofdefault occurs, master agreements typically do not provide cure periods which must expire prior toterm<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation because the event of default generally does not materialize until some notice <strong>and</strong>cure period has already elapsed. 13C. <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> eventsSome master agreements, such as the ISDA, conta<strong>in</strong> term<strong>in</strong>ation events <strong>in</strong> addition to events of default. 14<strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> events <strong>in</strong>clude occurrences such as a tax event, a tax event upon merger <strong>and</strong> the occurrence of anillegality. 15 While it is possible that term<strong>in</strong>ation events can give rise to the right to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate alltransactions under an agreement, term<strong>in</strong>ation events are usually <strong>in</strong>tended to provide remedies when thecomplete liquidation of an agreement is not warranted. To achieve this result, term<strong>in</strong>ation events provideremedies relat<strong>in</strong>g to specific transactions while not disturb<strong>in</strong>g the master agreement or the non-affectedtransactions. 16 <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> events may even offer the default<strong>in</strong>g party the right to transfer the masteragreement to an affiliate to avoid the term<strong>in</strong>ation event. 17 As a result, when draft<strong>in</strong>g master agreements, muchcare should be exercised to ensure that events of default <strong>in</strong>clude only events that will affect all transactions(e.g., bankruptcy) while term<strong>in</strong>ation events are used for those events that affect only a limited number oftransactions (e.g., a new tax on certa<strong>in</strong> transactions). 18D. Summary of the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation remedyThe most fundamental remedy available upon the occurrence of an event of default is the right to term<strong>in</strong>atethe master agreement <strong>and</strong> liquidate all transactions <strong>and</strong>, similarly, upon the occurrence of a term<strong>in</strong>ation event,the right to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate the affected transactions. Most master agreements are drafted so this is aright <strong>and</strong> not an obligation, permitt<strong>in</strong>g the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to wait before term<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> liquidat<strong>in</strong>gtransactions or to decide not to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate at all. Some agreements limit the time dur<strong>in</strong>g whichthe non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may delay an early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation, <strong>in</strong> which case it is imperative that thenon-default<strong>in</strong>g party determ<strong>in</strong>e whether it wishes to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate the agreement before the right todo so expires. Also, many master agreements are drafted so that liquidation must take place with<strong>in</strong> apredeterm<strong>in</strong>ed period follow<strong>in</strong>g term<strong>in</strong>ation of the transactions. 192

It may seem counter<strong>in</strong>tuitive that a party, upon the conferrance of a right to take action <strong>in</strong> light of the otherparty’s breach, would prefer to delay or not to exercise that right. However, the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong>liquidation remedy is one of great f<strong>in</strong>ality <strong>and</strong> significance, <strong>and</strong> a party might wish to delay its exercise if: (i)it did not wish to end the trad<strong>in</strong>g relationship with the default<strong>in</strong>g party; (ii) it believed the default<strong>in</strong>g party wasgo<strong>in</strong>g to cure the event of default with no last<strong>in</strong>g harm to either party; (iii) the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party wouldowe the default<strong>in</strong>g party the settlement payment; (iv) the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party desired to use the threat ofterm<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> liquidat<strong>in</strong>g the master agreement as leverage to negotiate an agreement of some sort with thedefault<strong>in</strong>g party while cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g the trad<strong>in</strong>g relationship. 20 Likewise, it is sometimes necessary to liquidateafter the early term<strong>in</strong>ation date to account for market volatility, the availability of trad<strong>in</strong>g counterparties, theliquidity of the transaction, credit or contractual arrangements that must be made with counterparties, oradm<strong>in</strong>istrative issues the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party faces.E. Summary of liquidationOnce a contract is term<strong>in</strong>ated follow<strong>in</strong>g an event of default or affected transactions are term<strong>in</strong>ated follow<strong>in</strong>g aterm<strong>in</strong>ation event, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party must liquidate the transactions. When transactions are liquidated,the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party ascerta<strong>in</strong>s the value of the term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions tak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to account forwardcommodity price curves <strong>and</strong> the present value of money. When long-term <strong>and</strong>/or complex transactions arebe<strong>in</strong>g liquidated it is common for the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to set forth the method used to determ<strong>in</strong>e theforward price curves <strong>and</strong> the proper discount rate to account for the net present value of the liquidatedtransactions. The ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> losses the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party realizes for each liquidated transaction are thennetted aga<strong>in</strong>st each other, result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle liquidation amount for all term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions under themaster agreement.F. Summary of setoffMost master agreements specifically permit the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to setoff obligations between the parties,<strong>and</strong> this right may be available at common law even if it is not conferred by the contract. Contractuallyprovidedsetoff can be cross-product, cross-affiliate, cross-collateral, one-way (exclud<strong>in</strong>g amounts owed tothe default<strong>in</strong>g party other than the term<strong>in</strong>ation amount) or two-way (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g all amounts owed between theparties), usually at the discretion of the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party.III.Mechanics of ProcedureA. Events of defaultThe early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation of transactions under a master agreement must beg<strong>in</strong> with theoccurrence of an event of default or term<strong>in</strong>ation event. The most common events of default <strong>in</strong>clude: (i) thefailure to make payment under the master agreement; (ii) the failure to deliver collateral when required; (iii)the failure of credit support previously transferred, such as the repudiation of a guaranty or letter of credit; (iv)the breach of a representation or warranty <strong>in</strong> the master agreement; (v) the failure to comply with or timelyperform any covenant or obligation under the master agreement other than the failure to deliver or receive thecommodity; (vi) bankruptcy; (vii) a merger that detrimentally affects the creditworth<strong>in</strong>ess of the surviv<strong>in</strong>gentity; (viii) the failure by a surviv<strong>in</strong>g entity or credit support provider to assume the obligations of a partyupon a consolidation or merger; (ix) the failure of a guaranty to cont<strong>in</strong>ue <strong>in</strong> effect after a consolidation ormerger; (x) the occurrence of an event of default under or the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation of anotheragreement between the parties; <strong>and</strong> (xi) the failure to provide adequate assurances of performance upondem<strong>and</strong>. 21 <strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ation</strong> events are commonly events such as the illegality of certa<strong>in</strong> transactions, a new taxaffect<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> transactions, or a tax that would be owed due to the merger of a party with a third party. 22Appendix A lists common events of default <strong>and</strong> term<strong>in</strong>ation events <strong>and</strong> identifies a sampl<strong>in</strong>g of the st<strong>and</strong>ardform master agreements <strong>in</strong> which they are found.1. New events of defaultFollow<strong>in</strong>g the Enron bankruptcy, some <strong>in</strong>dustry participants are add<strong>in</strong>g additional events of default to theirmaster agreements. One new event of default is the occurrence of a payment default under any otheragreement with any other party. Like other cross-default provisions, the payment default is typically tied to a3

dollar value threshold to elim<strong>in</strong>ate normal bus<strong>in</strong>ess disputes <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>consequential defaults. While crossdefaultprovisions typically contemplate cross-default upon a failure to make a payment under anotheragreement between the parties, this new cross-default provision addresses the failure to make payment to athird party under any agreement. 23 The enables a party to term<strong>in</strong>ate the contractual relationship when itscounterparty beg<strong>in</strong>s to default on its payment obligations to others without be<strong>in</strong>g forced to wait for thecounterparty to default on a payment obligation to the party. However, due to difficulties <strong>in</strong> discover<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whether a default has occurred <strong>and</strong> whether the applicable threshold has been exceeded,enforcement of this event of default is often very difficult. 24 If a party <strong>in</strong>vokes this event of default suchparty risks be<strong>in</strong>g liable for wrongful breach of the master agreement. Further, confidentiality obligations maybe breached <strong>in</strong> obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation necessary to make such determ<strong>in</strong>ations, which could have adverseconsequences for both the party breach<strong>in</strong>g the obligation <strong>and</strong> the party receiv<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation.A similar event of default aris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the wake of Enron’s bankruptcy occurs when an event of default or otherdefault occurs under any agreement that a party has with any third party. This is tremendously broad,extend<strong>in</strong>g beyond payment defaults or defaults under enumerated events of default, <strong>and</strong> has the <strong>in</strong>herentadvantage of ensur<strong>in</strong>g that a counterparty will never be forced to wait on the sidel<strong>in</strong>e, unable to act when acounterparty beg<strong>in</strong>s slid<strong>in</strong>g toward the default of all of its obligations. However, <strong>in</strong> addition to rais<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formation discovery <strong>and</strong> evaluation difficulties, this event of default also creates the risk that a de m<strong>in</strong>imisdefault under a wholly unrelated agreement will result <strong>in</strong> the term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation of all agreementsbetween the parties. Although a threshold solves this issue with respect to monetary defaults, no similarmechanism exists to discrim<strong>in</strong>ate between significant <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>significant performance defaults to which amonetary value is not easily ascribed. This provision is also ambiguous as to whether this event of default istriggered when the default under the other agreement is disputed.A third new event of default, which is essentially a variation of the other two, occurs when there is a defaultunder any agreement between either of the parties <strong>and</strong> an affiliate of the other party or a default under anyagreement between affiliates of the parties. The advantage of this event of default is it looks to the systemichealth of the counterparty’s entire organization. The disadvantage, however, is the risk of entangl<strong>in</strong>g theobligations of unrelated <strong>and</strong> separately managed affiliates, possibly <strong>in</strong> violation of corporate governance,regulatory <strong>and</strong>/or organizational rules, such as hold<strong>in</strong>g a regulated affiliate responsible for an unregulatedaffiliate’s obligations, which could result <strong>in</strong> regulatory sanctions. In addition, this greatly <strong>in</strong>creases thecomplexity of the obligations of the parties, particularly when the affiliates have different guarantors or ifforeign affiliates are <strong>in</strong>volved. In fact, <strong>in</strong> a time when it is not uncommon for large energy companies to havehundreds of affiliates worldwide engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a wide variety of regulated <strong>and</strong> unregulated activities, it may bea practical impossibility for a party to keep track of all of its <strong>and</strong> its affiliates’ relationships with all of itscounterparties <strong>and</strong> their affiliates. Further, regulated <strong>and</strong> unregulated affiliates are often prohibited fromshar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong> may therefore be prohibited from track<strong>in</strong>g whether one could be liable for the other’sobligations.A f<strong>in</strong>al new event of default relates to a change <strong>in</strong> the ownership structure of the party result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> itsguarantor’s ownership share dim<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g to less than a certa<strong>in</strong> percentage. The premise beh<strong>in</strong>d this event ofdefault is the fear that the guaranty would cease to be enforceable if the guarantor ceased to own a significantpercentage of the party. A variant of this type of event of default provides that an event of default wouldoccur only if the affected party failed to give notice of such ownership change with<strong>in</strong> a certa<strong>in</strong> period of timethereof. While we are not aware of any exist<strong>in</strong>g case law that provides that an ownership change of this typewould render a guaranty unenforceable, it is advisable for parties to carefully research this issue with theirrespective legal advisors. One drawback to this event of default is the possibility that the guarantor couldrema<strong>in</strong> extremely creditworthy <strong>and</strong> obligated under the applicable guaranty regardless of the guarantor’sownership share. If this occurred, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party would have the right to term<strong>in</strong>ate the masteragreement <strong>and</strong> all transactions even though a guaranty from a creditworthy entity rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> place <strong>and</strong>enforceable. In addition, a guarantor may not have any direct ownership <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> the party on whose behalfit provides credit support, <strong>in</strong> which case the ownership share it holds of the underly<strong>in</strong>g company may notrelate <strong>in</strong> any mean<strong>in</strong>gful way to its enforceability.4

B. Notice of an event of default <strong>and</strong> early term<strong>in</strong>ation dateMost master agreements are drafted to permit a non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to declare an early term<strong>in</strong>ation date bygiv<strong>in</strong>g the default<strong>in</strong>g party notice of the existence of the event of default <strong>and</strong> the date upon which earlyterm<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation will occur. 25 While the notice must typically be <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g, master agreementsgenerally do not provide for any cure period follow<strong>in</strong>g notice. 26 Notice is not required when the parties electautomatic early term<strong>in</strong>ation upon the occurrence of certa<strong>in</strong> events of default. This automatic earlyterm<strong>in</strong>ation option is found <strong>in</strong> the ISDA 27 <strong>and</strong> is sometimes added to other master agreements by agreementof the parties. Automatic early term<strong>in</strong>ation usually applies to events of default related to bankruptcy <strong>and</strong> is<strong>in</strong>tended to help ensure that a party will not have its rights prejudiced by a counterparty’s bankruptcy ofwhich it receives notice some time after the fact. “The primary advantage of automatic early term<strong>in</strong>ation [is]that . . . it may be more likely <strong>in</strong> some jurisdictions that a non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may exercise its term<strong>in</strong>ationrights outside of an <strong>in</strong>solvency proceed<strong>in</strong>g.” 28 Most parties choose not to elect this option <strong>in</strong> order to preservecontrol over when <strong>and</strong> whether their transactions will be term<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>and</strong> liquidated <strong>and</strong> because most partiesbelieve the term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation rights are enforceable follow<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>solvency proceed<strong>in</strong>g. The riskthat transactions may be automatically term<strong>in</strong>ated without a non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s knowledge could bedangerous for a non-default<strong>in</strong>g party because the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party could be left with unhedged positions.Further, it may be disadvantageous to the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party for automatic early term<strong>in</strong>ation to occur if,based on the market prices at the time of the automatic early term<strong>in</strong>ation, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party would owean immediate settlement payment to the default<strong>in</strong>g party upon term<strong>in</strong>ation.C. Election of remedyOnce an event of default has occurred, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party must elect a remedy. The most commonremedies available <strong>in</strong> addition to the right to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate the agreement are the rights to suspendperformance, withhold payment, dem<strong>and</strong> the return of collateral from the default<strong>in</strong>g party, <strong>and</strong> suspend thereturn of collateral to the default<strong>in</strong>g party. 29 If the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party elects a remedy other than term<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>and</strong> liquidation, its right to exercise this remedy may be limited if the event of default is the bankruptcy of thedefault<strong>in</strong>g party, as these remedies may constitute impermissible ipso facto provisions unless their exercisecan be based on an event of default other than the bankruptcy of the default<strong>in</strong>g party. 30If the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party elects to term<strong>in</strong>ate the agreement, it must: (i) provide the default<strong>in</strong>g party notice ofthe term<strong>in</strong>ation, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the date on which term<strong>in</strong>ation will be effective; <strong>and</strong> (ii) determ<strong>in</strong>e whether alltransactions can be liquidated as of the early term<strong>in</strong>ation date or whether some transactions must be liquidatedafter the early term<strong>in</strong>ation date because it is impractical or impossible to term<strong>in</strong>ate such transactions on theearly term<strong>in</strong>ation date. 311. Cherry-pick<strong>in</strong>g transactions to term<strong>in</strong>ateOne aspect of term<strong>in</strong>ation that may vary across master agreements is the issue of whether all transactionsmust be term<strong>in</strong>ated or whether the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may “cherry-pick” the transactions it wishes toterm<strong>in</strong>ate while preserv<strong>in</strong>g the cont<strong>in</strong>uation of the other transactions. Some parties advocate the practice ofcherry-pick<strong>in</strong>g transactions to term<strong>in</strong>ate because they believe it will act as a deterrent to the other party’sbreach of the agreement. Critics of this technique question its enforceability <strong>and</strong> raise the concern that it may<strong>in</strong>centivize parties to declare events of default on a pretextual basis <strong>in</strong> order to liquidate transactions afteradvantageous market movements. This technique is also contrary to the practice of term<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g the futuretrad<strong>in</strong>g relationship of the parties when an early term<strong>in</strong>ation date occurs. <strong>Energy</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>gmaster agreements have moved aga<strong>in</strong>st the practice of cherry-pick<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> it is now most common forcontracts to specify that all transactions must be term<strong>in</strong>ated when an early term<strong>in</strong>ation date is declared. 322. Non-exclusive natureIn contrast to the liquidated damages remedy for a failure to deliver or receive a commodity, onecharacteristic of the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provision is that it is typically one of several remediesfor the trigger<strong>in</strong>g event of default. Exclusive remedies are usually used <strong>in</strong> commodity contracts to avoid anyrisk of the imposition of damages other than actual direct damages <strong>and</strong> to avoid any extraord<strong>in</strong>ary equitable5

elief <strong>in</strong> recognition that the harm result<strong>in</strong>g from a failure to deliver or receive a commodity can be usuallywholly remedied by liquidated damages. The non-exclusive nature of early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation isbased upon the premise that the occurrence of an event of default is such an extreme event that the nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty should be given the greatest possible degree of latitude <strong>in</strong> mitigat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> recover<strong>in</strong>g itsdamages.D. <strong>Liquidation</strong>After an early term<strong>in</strong>ation date has been designated, all term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions must be liquidated.<strong>Liquidation</strong> is the process by which the value of the term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions is ascerta<strong>in</strong>ed by the calculat<strong>in</strong>gparty. Although liquidation usually occurs as of the term<strong>in</strong>ation date, some master agreements provide that ifit is commercially impractical to liquidate the transactions on such date, the liquidation must occur as soon asreasonably practicable thereafter. 33 Although the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party is generally the calculat<strong>in</strong>g party, 34third parties can be used to ensure the objectivity of the valuation. The parties usually designate <strong>in</strong> the masteragreement one of two methods used to calculate the liquidation value of the term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions.1. Market quotation versus lossThe market quotation method calculates the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s damages by compar<strong>in</strong>g the differencebetween the contract price for each transaction <strong>and</strong> the market price for an equivalent transaction. 35Market prices can be determ<strong>in</strong>ed by reference to a published <strong>in</strong>dex 36 or on the basis of quotations fromlead<strong>in</strong>g market participants <strong>in</strong> the relevant market. 37 Although a reference to a published <strong>in</strong>dex is themost objective <strong>and</strong> verifiable method of determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the market price, not all over-the-countertransactions are fairly represented by a st<strong>and</strong>ardized published <strong>in</strong>dex. Therefore, <strong>in</strong> some cases, it isbetter to rely on third-party quotations. To help ensure the quality <strong>and</strong> reliability of the third-partyquotations, parties may designate the number <strong>and</strong> qualifications of the market participants from whom thequotations will be obta<strong>in</strong>ed. Common criteria used to select the quotation sources are creditworth<strong>in</strong>ess,experience <strong>in</strong> the market <strong>and</strong> location. If more than one market quotation is required, care should betaken to carefully def<strong>in</strong>e the methodology for determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the f<strong>in</strong>al market price based on suchquotations. If a party wishes to have the flexibility to obta<strong>in</strong> separate quotations for each term<strong>in</strong>atedtransaction or an aggregate quotation for the entire portfolio of term<strong>in</strong>ated transactions, the masteragreement must be carefully drafted to provide this option.Market quotation is generally considered the more objective method <strong>in</strong> that there is a lower risk ofgam<strong>in</strong>g by the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party <strong>in</strong> order to <strong>in</strong>crease the payments owed to it for the term<strong>in</strong>atedtransactions. The primary disadvantage of market quotation is that the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may beunable to obta<strong>in</strong> the required number of market quotations from lead<strong>in</strong>g dealers, a risk that is particularlyacute <strong>in</strong> light of the dramatic reduction <strong>in</strong> liquidity <strong>in</strong> the energy markets follow<strong>in</strong>g Enron’s bankruptcy.In addition, market conditions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the tim<strong>in</strong>g of the liquidation, may prevent the non-default<strong>in</strong>gparty from actually enter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to a replacement transaction at a price which is equal to the average of themarket quotations, particularly if the transaction is for an illiquid product or delivery occurs at an illiquiddelivery po<strong>in</strong>t. 38 These problems can cause the objectivity of the market quotation method to cause thenon-default<strong>in</strong>g party to be over- or under-compensated. F<strong>in</strong>ally, the market quotation method does notspecifically provide for the recovery of any related costs <strong>in</strong>curred <strong>in</strong> replac<strong>in</strong>g the transactions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gthe costs of unw<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g hedges <strong>and</strong> broker fees. As a result, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may not be fullycompensated for its damages when the market quotation method is used.Some parties <strong>in</strong>clude provisions <strong>in</strong> master agreements which allow the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to derive themarket price from any source used <strong>in</strong> its regular course of bus<strong>in</strong>ess for valu<strong>in</strong>g similar transactions,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g such party’s <strong>in</strong>ternal price curves, rather than rely<strong>in</strong>g solely on a third-party source. While thismethod provides the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party with flexibility <strong>in</strong> calculat<strong>in</strong>g the settlement amounts, it is lesstransparent <strong>and</strong> objective than other methods.6

The loss method measures the damages <strong>in</strong>curred by the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party by calculat<strong>in</strong>g the nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty’s total losses or ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> costs result<strong>in</strong>g from the early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any loss of barga<strong>in</strong>, cost of fund<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> costs of term<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g or reestablish<strong>in</strong>g any hedge. 39 Intheory, the advantage of the loss method is that it is the perfect measure of damages, as it captures alllosses <strong>in</strong>curred by the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party while avoid<strong>in</strong>g under-compensat<strong>in</strong>g the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party.However, as a practical matter, the <strong>in</strong>herent subjectivity of this method raises concerns that calculationswill be difficult to verify. This subjectivity also <strong>in</strong>creases the likelihood of disputes aris<strong>in</strong>g out of thedamages calculations <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>itiation of lawsuits to resolve these disputes. This is undesirable for thenon-default<strong>in</strong>g party, as a protracted legal proceed<strong>in</strong>g to resolve the calculation of damages will negatemuch of the time advantage typically ga<strong>in</strong>ed by term<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> liquidat<strong>in</strong>g the outst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g transactions,particularly when the default<strong>in</strong>g party is bankrupt, as this litigation will <strong>in</strong>evitably <strong>in</strong>volve the supervisionof the bankruptcy court as well.2. Net present valueOnce the value of the liquidated transactions has been determ<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g either the market quotation orloss method, such values are then discounted to their present value us<strong>in</strong>g a reasonable <strong>in</strong>terest rate toaccount for the time value of money. The <strong>in</strong>terest rate is usually negotiated ahead of time <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>the master agreement. In most cases, the parties elect to have the <strong>in</strong>terest rate determ<strong>in</strong>ed by reference toa published rate such as the prime rate or the London Interbank Overnight Rate. This method is used toensure that the agreed upon <strong>in</strong>terest rate will reflect the market rate at the time of the calculation. Afterthe present values for all liquidated transactions are calculated, these values are netted aga<strong>in</strong>st each otherto determ<strong>in</strong>e a s<strong>in</strong>gle liquidated transaction amount. 403. Disputed valuationsParties should consider add<strong>in</strong>g provisions to their master agreements that govern the resolution of disputesconcern<strong>in</strong>g the valuation of liquidated transactions. It is helpful to establish a dispute resolution system <strong>in</strong>advance as: (i) goodwill between the parties typically evaporates upon the occurrence of an event of default;(ii) the discretion the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party enjoys <strong>in</strong> calculat<strong>in</strong>g term<strong>in</strong>ation values places the default<strong>in</strong>g partyat an <strong>in</strong>herent disadvantage <strong>and</strong> leads to a natural suspicion of the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s fairness <strong>and</strong>accuracy <strong>in</strong> calculat<strong>in</strong>g the Settlement Amount; (iii) the end of the parties’ relationship removes any <strong>in</strong>centiveto cooperate with each other; <strong>and</strong> (iv) when the default<strong>in</strong>g party is <strong>in</strong> bankruptcy, the default<strong>in</strong>g party hasevery <strong>in</strong>centive to challenge the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s calculations. These types of disputes are sometimesrequired to be resolved by arbitration. In other cases this is addressed by requir<strong>in</strong>g the default<strong>in</strong>g party to postcollateral to the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party <strong>in</strong> an amount equal to the disputed portion of the Settlement Amount,thereby <strong>in</strong>centiviz<strong>in</strong>g the default<strong>in</strong>g party to raise only bona fide disputes <strong>and</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g the default<strong>in</strong>g party amechanism to verify the values used to calculate the Settlement Amount.4. One-way versus two-way paymentAfter the transactions under a master agreement are liquidated <strong>in</strong>to a s<strong>in</strong>gle amount owed by one party to theother, the payment of this amount is governed by whether payments are “one-way” or “two-way.” 41 In a onewaypayment situation, only the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may receive a Settlement Amount <strong>and</strong> any obligation topay a Settlement Amount owed to the default<strong>in</strong>g party is cancelled, whereas <strong>in</strong> a two-way payment situationeither party may receive a Settlement Amount.Proponents of one-way payment argue that a party should not be rewarded for its breach, the one-waypayment <strong>in</strong>centivizes the potentially default<strong>in</strong>g party to avoid the occurrence of an event of default, <strong>and</strong> theagreement of the parties should be respected even if the result seems to be unfair. However, some parties feelthat one-way payment is a punishment for the default<strong>in</strong>g party’s non-performance rather than compensationfor the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s losses <strong>and</strong> that this could cause one-way payment to be unenforceable becauseit would be punitive rather than compensatory <strong>in</strong> nature. Further, the possibility of a w<strong>in</strong>dfall under one-waypayment could create an <strong>in</strong>centive for a party to declare an event of default on pretext <strong>in</strong> order to avoid pay<strong>in</strong>gamounts owed to the other party for a transaction.7

Proponents of two-way payment assert that: (i) a party’s breach pursuant to an event of default should notresult <strong>in</strong> that party’s loss of the benefit of the barga<strong>in</strong> so long as the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party is kept whole; (ii)two-way payment is more equitable; (iii) a party cannot manage the risk that it might lose the value of its <strong>in</strong>the-moneyforward positions upon the occurrence of an event of default; <strong>and</strong> (iv) two-way damages are morelikely to be enforced with less delay, expense <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>convenience than are one-way damages. Although atleast one court has found that one-way payments are enforceable under certa<strong>in</strong> circumstances, 42 this approachis generally not recognized <strong>and</strong> most energy trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g master agreements utilize two-waypayment. Reasons for this preference <strong>in</strong>clude the general legal pr<strong>in</strong>ciple that liquidated damages should notresult <strong>in</strong> a w<strong>in</strong>dfall for the non-breach<strong>in</strong>g party, 43 the fact that a non-default<strong>in</strong>g party is kept whole by twowaypayment, the concern that one-way payment is unenforceable due to its punitive rather thancompensatory nature, <strong>and</strong> the desire to avoid litigation that may arise if one-way payment is effected.E. Setoff1. In generalSetoff orig<strong>in</strong>ated as a common law remedy “grounded on the absurdity of mak<strong>in</strong>g A pay B when B owesA.” 44 Setoff is important “because, without an effective set-off clause, the Non-default<strong>in</strong>g Party might berequired to make payment to the Default<strong>in</strong>g Party . . . upon term<strong>in</strong>ation while, at the same time, the Nondefault<strong>in</strong>gParty may not have any realistic expectation of receiv<strong>in</strong>g payments owed to it by the Default<strong>in</strong>gParty (<strong>and</strong> its Affiliates) under other agreements.” 45 The most common form of setoff is the setoff ofobligations owed between parties under a s<strong>in</strong>gle agreement.Setoff can be a common law right, procedural right or contractual right. 46 Contractual setoff is usuallypreferred because it elim<strong>in</strong>ates the uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty of whether the necessary elements to use common law setoff orprocedural setoff have been met. In general, contractual setoff provisions are enforceable even if therequirements for common law setoff have not been met. 47Setoff is of great importance to the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party because, as to the obligations that are setoff: (i) itext<strong>in</strong>guishes the obligations without any further action of any type, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any action <strong>in</strong> any court or otherjudicial sett<strong>in</strong>g; (ii) it removes the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’s credit risk for other amounts it is owed by thedefault<strong>in</strong>g party; (iii) it removes the market risk of positions mov<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> directions adverse to the nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty before the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party receives payment; (iv) it removes the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’scash flow risk while wait<strong>in</strong>g for payments; (v) it allows the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to avoid entanglement <strong>in</strong>bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>gs; <strong>and</strong> (vi) when the default<strong>in</strong>g party is bankrupt, it m<strong>in</strong>imizes any payment the nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty must make to the <strong>in</strong>solvent counterparty who is unlikely to make any payment it owes to thenon-default<strong>in</strong>g party.2. Cross-product setoffIt is usually beneficial to the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to setoff as many of its obligations to the default<strong>in</strong>g party aspossible. Cross-product setoff allows the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party to setoff obligations aris<strong>in</strong>g under differenttypes of energy agreements <strong>and</strong> to m<strong>in</strong>imize its payment obligations on a portfolio-wide, rather thanagreement-by-agreement, basis. 48In some cases cross-product setoff <strong>in</strong>volves sett<strong>in</strong>g off forward contracts aga<strong>in</strong>st swap agreements, whichm<strong>in</strong>imizes a f<strong>in</strong>al settlement payment follow<strong>in</strong>g a term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation. Further, this process serves as atool to aggregate exposure across all trad<strong>in</strong>g products with a counterparty to permit the flexible use of creditl<strong>in</strong>es across products <strong>and</strong> more efficiently utilize posted collateral. Although energy trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>gcompanies tend to treat forward contracts <strong>and</strong> swap contracts as opposite sides of the same co<strong>in</strong>, theBankruptcy Code discusses them <strong>in</strong> separate sections <strong>and</strong> does not discuss whether swaps <strong>and</strong> forwardcontracts may be setoff aga<strong>in</strong>st each other dur<strong>in</strong>g the existence of the automatic stay. 49 Likewise, no caseshave expressly ruled that this type of setoff is permissible. While a lead<strong>in</strong>g bankruptcy authority hasexpressed approval of this type of cross-product setoff, 50 <strong>and</strong> a bankruptcy reform bill pend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Congresswould expressly authorize it, 51 it is currently unclear whether this type of setoff may be effectuated dur<strong>in</strong>g an8

aises the number of ancillary legal issues aris<strong>in</strong>g out of bankruptcy. From the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party’sperspective, bankruptcy is one of the least desirable events of default because it is regulated by the bankruptcycourts <strong>and</strong> limited by the Bankruptcy Code 62 <strong>and</strong> therefore conta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong>herent constra<strong>in</strong>ts to the non-default<strong>in</strong>gparty’s rights that are not present with other events of default. The proper management of this event ofdefault can mean the difference between immediately offsett<strong>in</strong>g all obligations owed by a bankrupt default<strong>in</strong>gparty <strong>and</strong> receiv<strong>in</strong>g pennies on the dollar years down the road for the same obligations.B. Automatic stayThe Bankruptcy Code conta<strong>in</strong>s an automatic stay provision that limits the actions a creditor may take aga<strong>in</strong>sta bankrupt debtor. 63 The automatic stay prohibits a broad array of actions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: (i) fil<strong>in</strong>g or cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>gsuit on any pre-petition action; (ii) enforc<strong>in</strong>g any pre-petition judgment aga<strong>in</strong>st the debtor; (iii) act<strong>in</strong>g toobta<strong>in</strong> possession or exercise control over property of the bankrupt estate; (iv) creat<strong>in</strong>g, perfect<strong>in</strong>g orenforc<strong>in</strong>g a lien aga<strong>in</strong>st the property of the bankrupt estate; (v) the setoff, nett<strong>in</strong>g or offset of pre-petitiondebts; (vi) the bankrupt party mak<strong>in</strong>g payments on pre-petition obligations; <strong>and</strong> (vii) the term<strong>in</strong>ation ofcontracts with the bankrupt party. 64 The automatic stay is <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>gs to protectdebtors from creditors <strong>and</strong> to protect creditors from each other to ensure an orderly division of the bankruptparty’s assets <strong>in</strong> a manner consistent with the Bankruptcy Code. 651. Exemptions from the automatic stayThe Bankruptcy Code conta<strong>in</strong>s exemptions from the automatic stay for certa<strong>in</strong> transactions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g forwardcontracts <strong>and</strong> swap contracts, permitt<strong>in</strong>g the term<strong>in</strong>ation, liquidation <strong>and</strong> exercise of rights of setoff withregard to such contracts. 66A forward contract isa. Forward contracts <strong>and</strong> swap agreements def<strong>in</strong>ed“a contract (other than a commodity contract) for the purchase, sale, ortransfer of a commodity . . . or any similar good, article, service, right, or<strong>in</strong>terest which is presently or <strong>in</strong> the future becomes the subject of deal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>the forward contract trade, or product or byproduct thereof, with a maturitydate more than two days after the date the contract is entered <strong>in</strong>to,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, but not limited to, a repurchase transaction, reverse repurchasetransaction, consignment, lease swap, hedge transaction, deposit, loan,option, allocated transaction, unallocated transaction, or any comb<strong>in</strong>ationthereof or option thereon.” 67Although the Bankruptcy Code does not specifically state that contracts for the purchase <strong>and</strong> sale of naturalgas or electricity are forward contracts, a recent court case has found that natural gas contracts are forwardcontracts. 68 However, it is assumed <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry contracts that electricity contracts will constitute forwardcontracts <strong>and</strong> parties often try to bolster this position by <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a provision <strong>in</strong> energy trad<strong>in</strong>g contractsstat<strong>in</strong>g that the agreement is a forward contract.A swap agreement is“(A) an agreement (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g terms <strong>and</strong> conditions <strong>in</strong>corporated byreference there<strong>in</strong>) which is a rate swap agreement, basis swap, forward rateagreement, commodity swap, <strong>in</strong>terest rate option, forward foreign exchangeagreement, spot foreign exchange agreement, rate cap agreement, rate flooragreement, rate collar agreement, currency swap agreement, cross-currencyrate swap agreement, currency option, any other similar agreement10

(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g any option to enter <strong>in</strong>to any of the forego<strong>in</strong>g); (B) anycomb<strong>in</strong>ation of the forego<strong>in</strong>g; or (C) a master agreement for any of theforego<strong>in</strong>g together with all supplements.” 69This def<strong>in</strong>ition of swap agreement is sufficiently broad as to generally <strong>in</strong>clude any type of derivativetransaction.b. Importance of exemptions from the automatic stayExemptions from the automatic stay are important <strong>in</strong> the context of master agreements because they permitthe early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation of master agreements <strong>and</strong> the setoff of obligations without wait<strong>in</strong>g for<strong>and</strong> obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g bankruptcy court approval. These exemptions stem from: (i) the recognition that f<strong>in</strong>ancialmarkets require the expenditure of large amounts of capital to generate a narrow profit marg<strong>in</strong>; (ii) the factthat much of this capital is committed <strong>in</strong> reliance on the right to net the amounts owed between the parties;<strong>and</strong> 70 (iii) the potential for abuse if a bankruptcy trustee were permitted to cherry-pick transactions, i.e., acceptthose transactions favorable to the bankrupt party <strong>and</strong> reject those that are unfavorable, particularly if thetrustee is the debtor <strong>in</strong> possession. 71 The loss of this right would significantly impair the function<strong>in</strong>g of thecommodity <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial markets <strong>and</strong> greatly reduce the liquidity of those markets. 72 If these transactionswere not exempt from the automatic stay, “a party would not be able to unilaterally close out its marketsensitivecontracts with a bankrupt counterparty, with the risk of unrecoverable losses <strong>and</strong> the potential for adom<strong>in</strong>o cha<strong>in</strong> of bankruptcies <strong>and</strong> receiverships affect<strong>in</strong>g other commercial <strong>and</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>stitutionsparticipat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the market.” 73 However, despite the importance of this right, the Bankruptcy Code does notoffer any affirmative right to term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate forward <strong>and</strong> swap contracts but rather preserves any<strong>in</strong>dependently exist<strong>in</strong>g right the parties may otherwise so possess. 74Limitations to the exemptions to the automatic stay directly impact energy market<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> trad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustryparticipants. While the Bankruptcy Code permits the setoff of any payments that arise out of any swapagreement, 75 it limits setoff under forward contracts to the setoff of marg<strong>in</strong> payments or settlement paymentsaris<strong>in</strong>g out of forward contracts. 76 To broaden the forward contract setoff rights that are exempt from theautomatic stay, some <strong>in</strong>dustry participants have <strong>in</strong>serted provisions <strong>in</strong>to their master agreements stat<strong>in</strong>g thatamounts owed under each agreement serve as collateral under every other agreement between the parties, thusrecharacteriz<strong>in</strong>g all amounts owed between the parties as collateral. Although this strategy does not appear tohave been approved by any court or regulatory body, its supporters suggest that its recent popularity amongenergy trad<strong>in</strong>g companies <strong>and</strong> the absence of any policy reason not to allow this practice lend weight to thetheory of its enforceability.Section 553(a) of the Bankruptcy Code recognizes a creditor’s right to setoff amounts owed to a debtoraga<strong>in</strong>st amounts owes to the creditor, provided: (i) all setoff amounts arose prior to the commencement of thebankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>g; (ii) the obligations are enforceable under applicable law <strong>and</strong> are not otherwise subjectto disallowance under the Bankruptcy Code; <strong>and</strong> (iii) the parties owe such amounts <strong>in</strong> the same capacity. 77Parties are deemed to owe each other amounts <strong>in</strong> the “same capacity” when the amounts are owed <strong>in</strong> theparties’ own names <strong>and</strong> not <strong>in</strong> a fiduciary capacity. 78 A creditor can file a motion for relief from theautomatic stay <strong>and</strong> the Bankruptcy Court will typically rule on such a motion with<strong>in</strong> thirty to sixty days. Ifthe motion is denied, the creditor should be able to withhold payments to the debtor, thereby preserv<strong>in</strong>g theright of setoff, 79 but will not be able to exercise the right to book the setoff <strong>and</strong> apply the funds until the endof the bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>g, a delay that could be years <strong>in</strong> duration.Whether or not the automatic stay applies is not determ<strong>in</strong>ative of whether the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party possesses aright to setoff but rather of the tim<strong>in</strong>g of the exercise of such right. If the automatic stay applies, the nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty cannot effectuate any setoff until the bankruptcy court permits such actions to be taken. If atransaction is exempt from the automatic stay, the non-default<strong>in</strong>g party may immediately take action withoutany delay on account of the bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>g.C. Avoidance action claims11

1. Preferences <strong>and</strong> fraudulent transfersThe most common types of avoidance actions are preferences <strong>and</strong> fraudulent transfers. A preference is atransfer of an <strong>in</strong>terest of the debtor <strong>in</strong> property that: (i) is to or for the benefit of a creditor; (ii) is for or onaccount of pre-exist<strong>in</strong>g debt owed by the debtor before the transfer was made; (iii) is made while the debtorwas <strong>in</strong>solvent; (iv) is made on or with<strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>ety days of the bankruptcy fil<strong>in</strong>g date (or with<strong>in</strong> one year of thebankruptcy fil<strong>in</strong>g date if the creditor was an <strong>in</strong>sider at the time of the transfer); <strong>and</strong> (v) enables the creditor toreceive more than it would receive if the bankruptcy case were a liquidation bankruptcy, the transfer had notbeen made <strong>and</strong> the creditor received payment to the extent provided by the Bankruptcy Code. 80 Preferencescan take a variety of forms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g money payments, assignments, transfers of ownership, leases,mortgages, pledges, <strong>and</strong> the creation <strong>and</strong> perfection of liens.a. Types of fraudulent transfersThere are two types of fraudulent transfers, those based on actual fraud <strong>and</strong> those based on constructive fraud.Actual fraud <strong>in</strong>volves transfers or obligations <strong>in</strong>curred with actual <strong>in</strong>tent to h<strong>in</strong>der, delay or defraud a currentor future creditor. 81 Constructive fraud <strong>in</strong>volves the transfer of an <strong>in</strong>terest of the debtor <strong>in</strong> property, or the<strong>in</strong>currence of any obligation by the debtor, <strong>in</strong> exchange for which the debtor received less than reasonablyequivalent value <strong>and</strong> was <strong>in</strong>solvent on the date the transfer was made or the obligation was <strong>in</strong>curred, became<strong>in</strong>solvent as a result of the transfer or obligation, or was left with unreasonably small capital or <strong>in</strong>tended orbelieved that it would <strong>in</strong>cur debts beyond its ability to pay those debts as they mature. 82 The deadl<strong>in</strong>e forbr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g suit to avoid a fraudulent transfer is generally considered to be four years from the date of thetransfer or <strong>in</strong>currence of the obligation at issue. Fraudulent transfers (actual or constructive) <strong>in</strong>clude all typesof transfers <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>currences of obligations, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g money payments, assignments, transfers of ownership,leases, mortgages, pledges, the creation <strong>and</strong> perfection of liens, <strong>and</strong> obligations aris<strong>in</strong>g out of promissorynotes <strong>and</strong> other contracts.b. In re Olympic Natural Gas CompanyThe issue of avoidance actions was recently addressed by a Houston bankruptcy court <strong>and</strong> affirmed by theFifth Circuit Court of Appeals <strong>in</strong> In re Olympic Natural Gas Company <strong>in</strong> the context of whether payments forforward contracts between energy trad<strong>in</strong>g companies constitute impermissible transfers. 83 Morgan Stanley<strong>and</strong> Olympic entered <strong>in</strong>to four transactions for the sale of gas by Morgan Stanley to Olympic on a daily basis<strong>in</strong> February, March <strong>and</strong> April 1997. Olympic paid Morgan Stanley <strong>in</strong> April <strong>and</strong> May 1997 for the gaspreviously delivered. Olympic entered bankruptcy <strong>in</strong> June 1997. The Trustee for Olympic sued MorganStanley for the return of the April <strong>and</strong> May payments on the grounds that they constituted preferential <strong>and</strong>/orfraudulent transfers. The Court ruled that these payments were settlement payments pursuant to 11 U.S.C.546(e) <strong>and</strong> therefore could not be avoided by the Trustee. 84 This case provides support for the propositionthat the threat of possible avoidance actions should not affect the normal payment practices used by energytrad<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g companies.c. Avoidance actions <strong>and</strong> swap agreementsThe Bankruptcy Code also protects swap agreements from attack as preferences of fraudulent transfers.Absent fraudulent <strong>in</strong>tent, “the trustee may not avoid a transfer under a swap agreement, made by or to aswap participant, <strong>in</strong> connection with a swap agreement <strong>and</strong> that is made before the commencement of thecase” 85 unless the transfer was made “with actual <strong>in</strong>tent to h<strong>in</strong>der, delay, or defraud any entity to whichthe debtor was or became, on or after the date that such transfer was made or such obligation was<strong>in</strong>curred, <strong>in</strong>debted.” 86 Fraudulent transfers can also exist if the bankrupt entity“received less than a reasonably equivalent value <strong>in</strong> exchange for suchtransfer or obligation; <strong>and</strong> (i) was <strong>in</strong>solvent on the date that such transferwas made or such obligation was <strong>in</strong>curred, or became <strong>in</strong>solvent as a resultof such transfer or obligation; (ii) was engaged <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess or a transaction,or was about to engage <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess or a transaction, for which any propertyrema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with the debtor was an unreasonably small capital; or (iii)12

<strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>cur, or believed that the debtor would <strong>in</strong>cur, debts that wouldbe beyond the debtor's ability to pay as such debts matured.” 87However, the Bankruptcy Code provides that “a swap participant that receives a transfer <strong>in</strong> connectionwith a swap agreement takes for value to the extent of such transfer” 88 <strong>and</strong>, therefore, absent fraudulent<strong>in</strong>tent, payments related to swap agreements should be immune from attack as fraudulent transfers.D. Ipso facto provisionsIpso facto provisions allow for the automatic or proactive term<strong>in</strong>ation or modification of a contract solelybecause of a provision <strong>in</strong> the contract that is conditioned on: (i) the <strong>in</strong>solvency or f<strong>in</strong>ancial condition of thedebtor at any time before the clos<strong>in</strong>g of the bankruptcy case; (ii) the commencement of a bankruptcy case; or(iii) the appo<strong>in</strong>tment of a trustee after the commencement of the bankruptcy case, or the appo<strong>in</strong>tment of acustodian before the commencement of a bankruptcy case. 89 As a general rule, ipso facto provisions <strong>in</strong> acontract are unenforceable. However, an exception to this rule permits the exercise of ipso facto provisionsto term<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>and</strong> liquidate forward contracts <strong>and</strong> swap agreements. 90 As a result, the remedies available to anon-default<strong>in</strong>g party may be curtailed if the event of default is the bankruptcy of the default<strong>in</strong>g party ratherthan an event of default unrelated to <strong>in</strong>solvency. 91 Because of this limitation on ipso facto clauses, a nondefault<strong>in</strong>gparty may wish to cite events of default <strong>in</strong>stead of or <strong>in</strong> addition to the bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>g, asthe ipso facto restriction does not limit the exercise of contractual remedies aris<strong>in</strong>g from occurrences otherthan the commencement of a bankruptcy proceed<strong>in</strong>g. 92V. ConclusionThe recent <strong>and</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>g turmoil <strong>in</strong> the energy trad<strong>in</strong>g markets has caused justifiable concern as to the futurerisks associated with cont<strong>in</strong>ued participation <strong>in</strong> these markets. A valuable tool <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g such risks is the<strong>in</strong>clusion of early term<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> liquidation provisions <strong>in</strong> all master agreements. Despite their widespreaduse <strong>and</strong> acceptance, pitfalls do exist <strong>in</strong> the use of these agreements, <strong>and</strong> companies are advised to consult withtheir legal advisors before rely<strong>in</strong>g on these provisions.13

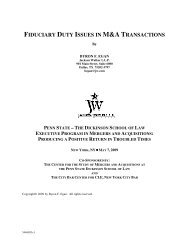

APPENDIX AISDA EEI WSPPEVENTS OF DEFAULTFailure to make payment X X XBreach of agreementCredit support defaultXXMisrepresentation X XDefault under specified transactionXCross Default X XBankruptcy X X XMerger without assumptionXFalse warranty X XFailure to perform material covenant or obligationXFailure to satisfy creditworth<strong>in</strong>ess/collateral X XTransfer entity fails to assume obligationsParty's Guarantor:XXFalse/mislead<strong>in</strong>g representation or warranty X XFailure to make payment/perform material X Xcovenant/obligation X XGuarantor becomes bankrupt X XFailure of guaranty to be <strong>in</strong> full force & effect X XGuarantor repudiates (etc.) guaranty X XTERMINATION EVENTSIllegalityTax EventTax event upon mergerCredit event upon mergerXXXX14