Netsuke: Small Sculptures of Japan: The Metropolitan Museum of ...

Netsuke: Small Sculptures of Japan: The Metropolitan Museum of ...

Netsuke: Small Sculptures of Japan: The Metropolitan Museum of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

'Ayj-; 77- "'r" si??s6. i i'4 '-s? i '"a" (Y t;II,i'I<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Artis collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art Bulletin ®www.jstor.org

Tiger by Raku (see p. 23)balanced and will stand unsupported on a flatsurface. Even slender pieces six or seven incheshigh will remain upright by themselves.Part <strong>of</strong> the appeal <strong>of</strong> netsuke is their smooth,agreeable feel, a special quality called aji in<strong>Japan</strong>ese, by which the artist communicates hisspirit through touch as well as sight. Aji isenhanced by handling, which also produces apatina that gives luster to wood and mellow tintsto ivory.<strong>Netsuke</strong> have depicted a multitude <strong>of</strong> subjectsand have been made from practically everymaterial found in <strong>Japan</strong>. <strong>The</strong> simplest andprobably the earliest were <strong>of</strong> stone, shell, walnutshells, and small gourds. Later and more sophisticatedones were carved from ivory and wood,particularly boxwood, cypress, ebony, cherry,pine, and bamboo. Less commonly employedwere bone, metal, and lacquer, although the latterwas one <strong>of</strong> the earliest materials, used fornetsuke created to match lacquer inro. Occasionally,netsuke were made from hornbill or amber.Several varieties <strong>of</strong> ivory were used. Until wellinto the nineteenth century, marine ivories andelephant ivory, which came from India throughChina, were imported into <strong>Japan</strong>. Elephant ivorywas used for plectrums for the koto, a stringedinstrument, and leftover pieces were sold tonetsuke carvers. <strong>The</strong> rarest and most precious <strong>of</strong>marine ivories came from the tusk <strong>of</strong> thenarwhal, credited with medicinal and magicalpowers. Two major schools <strong>of</strong> artists used deerantler and the teeth and tusks <strong>of</strong> wild boar astheir media.<strong>Netsuke</strong> are classified according to theirdistinctive forms. An early type, the sashi(literally, "thrust between"), was long, narrow,and usually made <strong>of</strong> wood, with the openings atthe top. It was meant to be inserted behind theobi, leaving the cord on the outside and thesagemono swinging freely. Later sashi hadadditional openings lower down and fartherapart.<strong>The</strong> most prevalent form, with the widestvariety <strong>of</strong> subjects and materials, was that <strong>of</strong>small sculptures called katabori, or "carving on allsides." Although they could be almost any shape,katabori are generally compact in keeping withtheir use.Manju netsuke derive their name and shapefrom the round, flat rice cake eaten mainly atthe <strong>Japan</strong>ese New Year. <strong>The</strong> simplest were made<strong>of</strong> solid pieces <strong>of</strong> ivory with a cord hole in thecenter. A variation developed, first in wood andthen in ivory, that had two halves that swiveledto open.<strong>The</strong> kagamibuta ("mirror lid") is a roundedshape having a disk, or lid, commonly <strong>of</strong> metal,set into a bowl <strong>of</strong> ivory or wood. This lid can beopened by releasing the tension on the cord,which is strung through the back <strong>of</strong> the bowl.Decoration was usually restricted to the metal,but in rare examples the bowl was elaboratelycarved as well.Ryusa netsuke, named for the eighteenthcenturycarver said to have originated them, werehollowed out with a turning lathe, a method thatmade possible delicate openwork designs and alightweight form.Mask netsuke were diminutive versions <strong>of</strong>those worn in the traditional dance-dramas <strong>of</strong><strong>Japan</strong>. <strong>The</strong> earliest, mainly <strong>of</strong> wood, were createdby mask carvers seeking to copy the originals,but later examples became stylized and evencomical.Many netsuke had a secondary function.<strong>The</strong>re were ashtray netsuke for transferringsmoldering ashes from the spent pipe into a bowl<strong>of</strong> unlit tobacco. Other useful items that could befound among netsuke were compasses, whistles,sundials, abaci, brush rests, cases for flints andsteels, and even firefly cages.<strong>The</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> netsuke was stimulated bysocial changes <strong>of</strong> the sixteenth and seventeenthcenturies affecting fashions in sagemono. Soonafter Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) becameshogun in 1603, he instituted stringent controlsto ensure his supremacy and maintain peace. Astrict Neo-Confucian code was established.<strong>Japan</strong>ese society was stratified into classes. <strong>The</strong>highest included the samurai, and it wasfollowed by the farmer, artisan, and merchantclasses. Laws governed private conduct, dress,marriage, and, for some, place <strong>of</strong> residence.Although the highest class was subject tosumptuary laws, samurai were allowed to wear4

two swords as symbols <strong>of</strong> their rank. With nowars to fight, sword blades and fittings becamemore decorative than practical, and wealthysamurai lavished enormous amounts <strong>of</strong> moneyon them.On formal occasions samurai sometimes woreinro. Since, like sword fittings, they were notsubject to sumptuary laws, inro also becameobjects for show, and were elaborately embellishedwith gold and other precious materials. Atfirst only the samurai class could afford them,but eventually they were adopted by theprospering members <strong>of</strong> other classes as well, andsoon many wore inro with matching netsuke.Meanwhile, a parallel social and economicdevelopment spurred a second fashion insagemono. When the Portuguese introducedtobacco into <strong>Japan</strong> in the sixteenth century,smoking took hold immediately. Crops wereplanted in southern Kyushu, and soon themajority <strong>of</strong> <strong>Japan</strong>ese were enjoying pipes,although it was considered improper formembers <strong>of</strong> the upper classes to smoke outsidetheir homes. An edict forbidding the use <strong>of</strong>tobacco was passed in 1609, primarily becausethe habit was considered unsanitary, but the lawwas difficult to enforce and was finally repealedin 1716 in the hope that the tobacco crop wouldhelp the economy.<strong>The</strong> repeal encouraged smoking. Amongtradespeople, it became an integral and almostritualistic part <strong>of</strong> any business transaction. <strong>The</strong>demand for portable implements-pipe cases,tobacco pouches, and lighting devices-increased,and with it the production <strong>of</strong> netsuke. As a largepercentage <strong>of</strong> the male population begansmoking, hundreds <strong>of</strong> thousands <strong>of</strong> exampleswere created in various styles and qualities.By the mid-eighteenth century virtually every<strong>Japan</strong>ese male carried one or more sagemonorequiring netsuke. Artisans such as mask makersand Buddhist sculptors, who originally carvednetsuke only as a sideline, began to specialize inthem. By the end <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century,netsuke carving was no longer considered aninsignificant pastime and artists began to signtheir works and form schools with local andregional traditions.By 1781 Inaba Tsuryfi (Shineimon) <strong>of</strong> Osaka, aconnoisseur <strong>of</strong> sword fittings, could devotealmost one volume <strong>of</strong> the seven <strong>of</strong> his Soken Kisho(which may be translated as 'A Treasury <strong>of</strong>Sword Fittings and Rare Accessories") to fiftyfivenetsuke carvers <strong>of</strong> his day and theirdesigns. <strong>The</strong> cursory text discusses artistsworking in Edo (now Tokyo), Osaka, Kyoto, andWakayama, and suggests that they had originallyproduced other forms <strong>of</strong> sculpture, such asmasks, Buddhist images, and architectural details,before turning to netsuke. He fails to mentionwhat might be regarded as the first school <strong>of</strong>netsuke artists-the earliest group having adefinite stylistic relationship, who worked in thesouthern Honshu province <strong>of</strong> Iwami. By thenineteenth century, however, many <strong>of</strong> the carverscited in the Soken Kisho had come to be consideredoriginators <strong>of</strong> schools in their own right.Earlier written descriptions <strong>of</strong> the development<strong>of</strong> netsuke do not exist, and since few seventeenth-centuryexamples survive, we have to relyon scrolls, screens, and prints for a pictorialrecord. In the Kabuki Sketchbook Scroll (in theTokugawa Reimeikai Foundation, Tokyo), datingfrom the first half <strong>of</strong> the seventeenth century, anactress is shown wearing an assortment <strong>of</strong>articles suspended from a large ring around thenarrow obi. <strong>The</strong> next style, depicted in a screen<strong>of</strong> the second quarter <strong>of</strong> the century, was a diskor wheel shape (later the manju), which towardthe middle <strong>of</strong> the century acquired a center pegwith a hole for the knot. <strong>Small</strong> sculptures in theround are not illustrated much before theeighteenth century.Fortunately, many fine netsuke remain fromabout the 1750s on. Early eighteenth-centuryexamples are usually large, spirited, and originalin design, being more direct expressions <strong>of</strong> theircreators' personalities and geographical locationsthan later pieces. For instance, Osaka netsukereflected the vitality <strong>of</strong> a bustling commercialcenter, while those made in Kyoto, the ancientOx by Tomotada (see p. 23)5

<strong>The</strong> man smoking a pipe, from the center panel <strong>of</strong> awood-block triptych <strong>of</strong> shellfish gatherers by UtagawaToyokuni (1769-1825), holds an ashtray netsuke that isattached to his tobacco pouch. Rogers Fund, 1914,JP 204imperial city, were dignified and restrained; andartists in the remote area <strong>of</strong> Iwami were interestedin naturalistic local subjects rendered inindigenous materials.Since there was no established tradition t<strong>of</strong>ollow, the artists <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth centuryenjoyed a freedom <strong>of</strong> interpretation. As netsukewere unimportant in the eyes <strong>of</strong> the government,no attempt was made to regulate them. Parody,satire, and parable could be used without fear <strong>of</strong>censorship. Moreover, with traditional religioussculpture in decline by the Edo period, netsukeprovided an opportunity to express religiousthought and feeling.Subject matter was largely derived fromChinese and <strong>Japan</strong>ese legends, religion, andmythology: fantastic animals predominated, likethe shishi (the lion-dog), but animals <strong>of</strong> the zodiacwere also popular. Heroes, reflecting Neo-Confucianvirtues, were part <strong>of</strong> the figure repertoryalong with Buddhist and Taoist saints, whosepious feats appealed to the <strong>Japan</strong>ese taste for thesupernatural.Toward the end <strong>of</strong> the century, new materialswere in evidence, with stain and inlay usedsparingly for dramatic effect. Coral, ranging incolor from black to dark red, was employedprincipally for eyes, providing textural contrastand a reflective surface simulating "life," orvitality, as did the glass eyes inlaid in the largesculptures <strong>of</strong> the Kamakura period (1185-1333).By the first half <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century, asschools developed, pupils tended to carry ontheir masters' techniques and <strong>of</strong>ten copied theirworks. Skilled carvers sometimes published theirdesigns as models, or passed workbooks along totheir more gifted apprentices. Subjects wereincreasingly drawn from printed sources, andthis dependency may be responsible in part forthe diminishing <strong>of</strong> much <strong>of</strong> the spontaneity andoriginality <strong>of</strong> the earlier pieces. To make theirworks distinctive, artists concentrated on refinements<strong>of</strong> technique. <strong>Netsuke</strong> became moreornate and more complicated.In subject, heroic legendary figures gave wayto smaller, compact, and complex representationsespecially those from <strong>Japan</strong>ese folklore. Groups<strong>of</strong> figures-men and animals-were depicted, andportrayals became more naturalistic. <strong>Netsuke</strong>paralleled other artistic developments <strong>of</strong> thetime. <strong>The</strong> introduction <strong>of</strong> such Western conceptsas perspective had its effect on these small sculp-6

tures. <strong>The</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t outlines hardened, and realismbecame the conventional style. Innovation waslargely a matter <strong>of</strong> imaginative technique, anunusual subject, and complicated decorativemotif. If the eighteenth century represented theunrestrained beginnings <strong>of</strong> this art form, the firsthalf <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth shows it fully matured andhighly sophisticated.In 1853 Commodore Perry sailed into theharbor <strong>of</strong> Uraga, and in 1867 <strong>Japan</strong>'s policy <strong>of</strong>isolation begun under Ieyasu was ended. As thecountry became Westernized, the daily wear <strong>of</strong>netsuke declined. Cigarettes replaced the traditionalsmall-bowl pipe and its accouterments,and suits with pockets grew popular withbusinessmen, who would still wear the kimonoat home or for ceremonial occasions. <strong>The</strong> needfor sagemono eventually vanished.<strong>The</strong> opening <strong>of</strong> <strong>Japan</strong>ese ports to foreign tradeacquainted European collectors with netsuke,and their interest prompted a tremendous revival<strong>of</strong> this art form in <strong>Japan</strong>. <strong>Netsuke</strong> were producedin great numbers as souvenirs as well as artobjects. From the 1870s through the 1890s majorcollections were formed in Europe. Unfortunatelythe majority <strong>of</strong> examples produced after thebeginning <strong>of</strong> the Meiji Restoration (1868) weremechanical imitations <strong>of</strong> the earlier delightfulsculptures, and are <strong>of</strong>ten angular and clumsy.In general, Europeans tended to collect theearlier, more robust, and livelier netsuke, whileAmericans, who for the most part did not comeinto contact with them until the twentiethcentury, were attracted to later pieces demonstratingtechnical achievement. Recently therehas been a new surge <strong>of</strong> interest in these smallsculptures in this country, and, stimulated by thepublication <strong>of</strong> more reference material inEnglish, Americans are building some <strong>of</strong> the bestand most well-rounded collections in the world.<strong>The</strong> collection <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong>Art, reflecting as it does the tastes <strong>of</strong> its donors,who made most <strong>of</strong> their acquisitions during thelate nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, isexceptionally strong in nineteenth-centuryexamples. <strong>The</strong> pieces on the following pageshave been chosen to present as broad a range aspossible-in date, subject, and style. Together,these small sculptures, all <strong>of</strong> high quality,provide an introduction to the many forms <strong>of</strong> thenetsuke carver's art, in all its intricacy, charm,and imagination.r ..I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Boar by Tomotada (see p. 22). <strong>The</strong> beautifully carvedunderside displays ferns and other plants, and theartist's signature.7

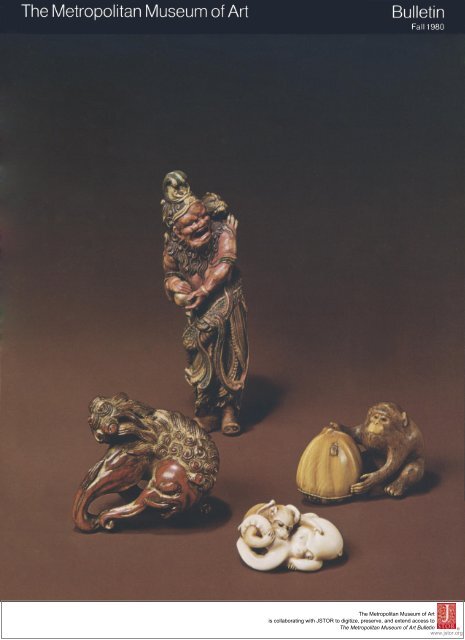

fIeneral Kuan-yii (died A.D. 219), a hero <strong>of</strong> theHan dynasty (202 B.C.-A.D. 220) in China,was considered by the <strong>Japan</strong>ese to be theepitome <strong>of</strong> Confucian virtue. He was a popularimage in Edo period prints, paintings, andnetsuke.This tall, imposing figure communicatesstrength and purpose. <strong>The</strong> interpretation ischaracteristically Chinese in the slenderness <strong>of</strong>the face as well as in the style <strong>of</strong> the long flowingrobes. Here, the undulating mandarin headdressblends into the s<strong>of</strong>tly contoured drapery <strong>of</strong> theouter robe, while the long sleeve falls in gentlefolds from the left arm. Kuan-yii's elegantlyformed hand, with its tapered fingers, caresseshis long beard, as if he were standing in quietcontemplation. His right arm holds his halberdbehind him, further minimizing his martialcharacter. This exquisite carving, enhanced bythe patination <strong>of</strong> time and wear, is one <strong>of</strong> thefinest eighteenth-century netsuke in thecollection.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 478 inches. Signatureundecipherable and added at later date. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs.Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.14968

Bl,iE= 3 -~~~~~~~~~a'K3U~~~~~~~~~~~~9W^^M i?--x"ld SFE i?r: HFt~~J~~g}tt l fj3- ~~" WtrKX Z +:~~~"r*00 : M tez 0

mori Hikoshichi (lived about 1340), a vassal<strong>of</strong> Shogun Ashikaga Takauji (1305-58),<strong>of</strong>fered to assist a beautiful maiden on her wayto a celebration <strong>of</strong> his victory over Emperor GoDaigo (reigned 1319-38). As he gallantly carriedher across a stream, he glanced at her reflectionon the water and saw that she had turned into awitch, whereupon Omori slew her with hissword. (In one account she is the daughter <strong>of</strong> ageneral killed in the battle, attempting to avengeher father's death.)When viewed from various angles, the figure<strong>of</strong> the witch presents an unusual contrast. <strong>The</strong>back displays a hair style <strong>of</strong> topknot and curls,characteristic <strong>of</strong> early Buddhist sculpture, andthe body is bare to the waist except for a narrowscarf, again reminiscent <strong>of</strong> images <strong>of</strong> holy men.However, the front view reveals a truly absurdfemale figure-trying modestly to cover herselfwhosebelly protrudes and whose bent legs causeher feet to turn in.Tall and superbly carved, . * .this piece expresses the vitality * P'%l<strong>of</strong> early netsuke. To convey asense <strong>of</strong> physical tension, theartist tilted Omori's bodyrforward, flexed his knees, anddepicted his toes grasping forbalance. Because <strong>of</strong> its large size,fine quality, and humorousinterpretation, this is themost unusual rendition <strong>of</strong>the subject known.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height /6 inches. Signed: Homin and , ,a kakihian (stylized signature).Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, r/,10.211.1502 _X l10

<strong>The</strong> netsuke at the left is a variation on thelegend <strong>of</strong> two symbiotic characters,Ashinaga ("Long Legs") and Tenaga ("LongArms"). <strong>The</strong>y cooperated in catching the fishthat comprised most <strong>of</strong> their diet: as Long Legswaded deeper and deeper into the water, wherethe fish were more abundant, Long Arms wasable to reach down and seize them. <strong>The</strong> legendbecame popular in China, and from there entered<strong>Japan</strong>ese mythology. Here, the artist may havealluded to the source as he knew it by putting aTaoist sage in Chinese dress on Ashinaga'sshoulder in place <strong>of</strong> Tenaga.This is the tallest piece in the collection and isrepresentative <strong>of</strong> an early elongated style thatlasted only a brief period, as it proved tooclumsy for easy wear. Because <strong>of</strong> the shape <strong>of</strong>this netsuke, it may have been worn either thrustinto the sash, or in the more usual way, held tightagainst the body by the cord passing throughtwo openings on the sides.Eighteenth century. Wood, height 63/4 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.230611

ennin were "immortals" thought to possesssupernatural powers. In art they arefrequently accompanied by a spirit, usually inthe form <strong>of</strong> an animal, who attends or guardsthem. Chinese legends describe them asfollowers <strong>of</strong> Taoism, and in <strong>Japan</strong> the name"sennin" was sometimes applied to Buddhistmonks who became mountain hermits. Innetsuke they are characterized by curly hair andbeard and large ears. <strong>The</strong>y usually have a benignexpression, and their Chinese-influencedcostumes include a monk's garment, leaf girdle,and drinking gourd.This sennin carries a karashishi (from the<strong>Japan</strong>ese kara, or "China," and shishi, or "lion"),an animal <strong>of</strong> Buddhist origin (see p. 17). <strong>The</strong>bond between the immortal and his companionis conveyed in the man's upturned smiling face.Western influence is apparent in his costumetheruffed collar, tunic, leggings, and s<strong>of</strong>t shoesbutthe curly hair and beard, gourd, and,Buddhist whisk under his sash (at the back), aswell as the sacred animal, indicate beyond doubtthe this example was not meant to portray aWesterner. Large, solidly proportioned figuressuch as this are representative <strong>of</strong> eighteenthcenturynetsuke.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 5 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs.Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.149812

Kinko (as he is known in <strong>Japan</strong>ese) was aChinese recluse (Ch'in Kao) who lived neara river. One day he was invited by the King <strong>of</strong>the Fishes into the river for a visit. Kink6 badehis pupils farewell and promised to return. Aftera month he reappeared astride a giant carp.According to a <strong>Japan</strong>ese version <strong>of</strong> this legend, hethen instructed his pupils not to kill fish andreturned forever to the underwater domain.This sennin, in a scholar's robe and readingfrom a scroll-perhaps an admonishment againstthe killing <strong>of</strong> fish-suits one <strong>Japan</strong>ese version <strong>of</strong>the story, but the carp's horn, an unusual detail,suggests another in which a sennin nurtured alarge carp that grew horns and wings.Eighteenth-century carvers <strong>of</strong>ten combineddetails from several similar legends. To them,variation and creativity frequently meant morethan adherence to a specific iconography.Here, the carp's tail arches protectively overthe sennin, while the horn projects upward,focusing the viewer's attention on the smallfigure. <strong>The</strong> waves cradle the rider and mount,and seem to be bearing them to their destination.<strong>The</strong> carp's eyes, <strong>of</strong> tortoise shell with inlays <strong>of</strong>black coral, add contrast and color to the design.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 2 inches. <strong>The</strong> H.O.Havemeyer Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O.Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.756<strong>The</strong> figure at the far left on the overleaf isTekkai, a Taoist immortal who blew his soulto heaven. On the soul's return it could not findits body, and had to enter that <strong>of</strong> an old man. Inthis portrayal in wood, the face is given greatexpressiveness through the large ivory eyes,accented by black-coral pupils. <strong>The</strong> lifelikequality <strong>of</strong> the sculpture is enhanced by the tilt <strong>of</strong>the head, puckered lips, and curve <strong>of</strong> the body,which has a sharply defined neck and chest.Tension within the sculpture is further heightenedby the action <strong>of</strong> an unseen wind whippingthe tattered robe against the straining body.A leaf girdle <strong>of</strong> ivory and tortoise shell hugsthe body at the hips and flows smoothly into thelines <strong>of</strong> the robe. <strong>The</strong> inlay adds color and providestextural contrast with the s<strong>of</strong>tly contouredwood. Hanging from the sash, attached to amalachite flower-shaped netsuke, is a movableivory drinking gourd.Late eighteenth-early nineteenth century. Wood,height 23/4 inches. Signed: Chikusai. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs.Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.236213

R yujin (center), the Dragon King <strong>of</strong> the Sea,probably came into <strong>Japan</strong>ese folklore fromChina. He is a popular figure in netsuke, usuallyshown as a fierce old man, with a long curlingbeard, and accompanied by a dragon. Here, heholds the jewel by which he controls the tides.This example is in the style <strong>of</strong> YoshimuraShuzan <strong>of</strong> Osaka, a Kano school painter <strong>of</strong> themid-eighteenth century, who, according to theSoken Kisho, was considered one <strong>of</strong> the finestcarvers <strong>of</strong> his day. He is the innovator in netsuke<strong>of</strong> legendary and mythological figures done inthis technique: the carved wood was coveredwith a gessolike sealer over which watercolorwas applied.Although this sculpture is in Shuzan's style, itis <strong>of</strong> boxwood rather than the s<strong>of</strong>ter, more opengrainedcypress that he favored, suggesting thatit was not carved by the master himself. Itsfreshness <strong>of</strong> color is the result <strong>of</strong> applyingoxidized copper and other minerals in a solution<strong>of</strong> glue. Ryujin's garment is ornamented with adesign in gold lacquer, simulating patterns <strong>of</strong>tenfound on the robes <strong>of</strong> Buddhist sculptures.Late eighteenth-early nineteenth century. Wood,height 4 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910,10.211.2331A mong the few foreigners allowed to remainafter the Tokugawa government bannedChristianity and expelled the Portuguese in 1636were the Dutch, who were confined to the island<strong>of</strong> Deshima in Nagasaki Harbor. Only the representative<strong>of</strong> the Dutch East India Company wasable to travel to the mainland to give his yearlyreport. By the second half <strong>of</strong> the eighteenthcentury, when some <strong>of</strong> the restrictions had beenlifted, there was a revival <strong>of</strong> foreign studies, andin 1789 the first Dutch language school openedin Edo. It seems likely, therefore, that netsuke <strong>of</strong>Dutchmen date from about the last quarter <strong>of</strong>the century. <strong>The</strong>ir popularity was short-lived,however, as they went out <strong>of</strong> fashion around thefirst quarter <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century.Since few <strong>Japan</strong>ese had actually seen aforeigner, genuine portraits are rare, and a type<strong>of</strong> Dutchman developed in netsuke that isexemplified by this representation. Round-eyed,with a bulbous nose and shoulder-length hair, hewears a tasseled, brimmed hat, buttoned tunicwith ruffed collar, knee breeches, stockings, andplain s<strong>of</strong>t shoes. Most <strong>of</strong> the figures carry a dog,gun, or bird-usually a cock, as here, probablyreferring to the Dutch colony's pastime <strong>of</strong>cockfighting. Many <strong>of</strong> these netsuke are ivory,possibly because they would appeal to thewealthier and more worldly clients who couldafford that material.Late eighteenth century. Height, 41/8 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.150615

<strong>The</strong> first animal netsuke, dating from theseventeenth century, were mostly <strong>of</strong>creatures derived from Chinese mythology, suchas the kirin, baku, and karashishi. <strong>The</strong> kirin, theOriental version <strong>of</strong> the unicorn, is considered aparagon <strong>of</strong> virtue: so light-footed that it createsno noise when it walks, and so careful that itharms not even the tiniest insect. Its rare appearanceon earth is thought to be a lucky omen.<strong>The</strong> kirin has the head <strong>of</strong> a dragon, with ahorn that lies against the back <strong>of</strong> its head, thebody <strong>of</strong> a deer, legs and hooves similar to those<strong>of</strong> a horse, and the tail <strong>of</strong> a lion. Scales or protuberancesare part <strong>of</strong> the body decoration.Usually, flamelike shapes flare from the chest orshoulders. <strong>The</strong>se "fire markings" are a designelement that originated in Chinese art and wereused by netsuke carvers only during theeighteenth century to indicate that the subjectwas a mythological beast with supernaturalcharacteristics.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 27/8 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.1408-"i": I iL`k *- Trq:::.Ihe \ \I: P -url ? $a'`1P-t; i?i,I16

<strong>The</strong> baku is supposed to eat bad dreams. It isso effective that even the character for"baku" painted on a headrest will keep awayfrightening nightmares. Physically it combinesthe head <strong>of</strong> an elephant, and the body, mane,claws, and tail <strong>of</strong> a karashishi (below). <strong>The</strong><strong>Japan</strong>ese version differs slightly from theChinese, which has the tail <strong>of</strong> an ox and aspotted hide. Fantastic composite animals likethe baku and kirin went out <strong>of</strong> style in netsukeby the end <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century.This is a rare example, depicted not in theusual seated position but crouching as ifsearching for something, and carved in woodrather than the ivory used for most early mythologicalanimals. <strong>The</strong> finish is enhanced bycontrasting gold lacquer applied to the surface(see cover illustration).Eighteenth century. Wood, length 2 inches. Signed:Sadatake or Jobu. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910,10.211.2278T he karashishi is characterized by a fierceexpression with protruding eyes, widenostrils, and open mouth. Its curly mane isusually balanced by long curled locks on its legsand a bushy tail. <strong>The</strong> earlier the rendition, thestronger the facial expression and the moreelaborate the curls. In China they are shown inpairs and commonly associated with the imperialfamily; in <strong>Japan</strong> they are <strong>of</strong>ten found in Buddhistlore, occasionally as temple guardians, and aresometimes associated with holy men (see p. 12).In netsuke shishi are frequently depictedwhimsically, and this one, resting quietly, gazessolemnly out <strong>of</strong> dark inlaid pupils set dramaticallyinto gold eye sockets. This subtle use <strong>of</strong>gold indicated the owner's wealth while circumventingthe government's sumptuary laws.Late eighteenth-early nineteenth century. Ivory, length1/ inches. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.1717

This stag represents the stylistic transitionbetween the highly imaginative creatures <strong>of</strong>the early to middle eighteenth century, and themore realistic animals <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century.Its elegantly simple pose-seated, with anupturned head and stretched neck-is similar tothose <strong>of</strong> kirin in earlier netsuke, but its branchedantlers, sloping ribs, and spotted coat are indications<strong>of</strong> a new interest in authentic details.Late eighteenth century. Ivory, height 51/4 inches. Gift<strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.2308he tanuki, a badgerlike animal that is amember <strong>of</strong> the raccoon family, wasportrayed as a partially imaginary beast endowedwith supernatural powers. Depicted as more <strong>of</strong> apractical joker than a malicious or evil character,it <strong>of</strong>ten assumed disguises to further its subterfuge.Here it wears a lotus-leaf hat, carries abottle <strong>of</strong> sake in one hand, and holds a bill <strong>of</strong>sale for the liquor in the other. While the bottleand the bill suggest drunkenness, the lotts leaf,symbolizing purity, alludes to Buddhism, with itsemphasis on sobriety. This netsuke might betaken as a comment on the priests <strong>of</strong> the time,who sometimes indulged in practices contrary totheir religious vows.Garaku, the artist, is mentioned in the SokenKisho as "a clever carver and a disciple <strong>of</strong>Tawarya Denbei," an early master whose workshave not survived. <strong>The</strong> few authentic netsuke byGaraku are highly imaginative and expressive, asis this one, and frequently communicate thesame feeling <strong>of</strong> humor.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 23/4 inches. Signed:Garaku. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.143618

ighteenth-century animal netsuke by artistsin the Kyoto area had well-defined spinesand rib cages, and if the creature had a tail, itwas usually tucked between the legs and hiddenunder the body. (During the nineteenth century,the tails <strong>of</strong> animal netsuke were incorporated onthe outside <strong>of</strong> the piece, usually wrapped aroundthe body.) On the basis <strong>of</strong> these features alone,this wolf can be attributed to a Kyoto artist <strong>of</strong> theeighteenth century, a date verified by the signature<strong>of</strong> Tomotada, who is listed in the Soken Kishoand probably worked in Kyoto in the second half<strong>of</strong> the century.<strong>The</strong> gaunt figure may represent pure hungeror it may be a symbolic expression <strong>of</strong> angeragainst the poor crops, high taxes, and capricioussamurai overlords <strong>of</strong> the time.Eighteenth century. Ivory, length 2 inches. Signed:Tomotada. <strong>The</strong> H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest<strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.91820

ealistic, the muzzle is s<strong>of</strong>tly rounded anddouble-haltered-with a rope meticulouslycarved in raised relief. Other indications <strong>of</strong> hiswork are the large eyes, inlaid with pupils <strong>of</strong>black coral, the bulging sides, and the tucked-uplegs with clearly defined hooves.Eighteenth century. Ivory, length 23/s inches. Signed:Tomotada. Bequest <strong>of</strong> Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881,81.1.40<strong>The</strong> Oriental zodiac is based on a cycle <strong>of</strong>twelve years, each associated with an animal.<strong>The</strong>se animals also represent the hours <strong>of</strong> theday and the points <strong>of</strong> the compass. According tolegend, Buddha called all the creatures to him fora celebration, but only twelve came. <strong>The</strong> order inwhich they arrived determined the year eachsymbolizes in the zodiac. In the diagram abovethe <strong>Japan</strong>ese characters (reading clockwise) standfor rat, ox, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse,sheep (though the animal depicted is a goat),monkey, cock, dog, and boar, which are illustratedon the overleaf.<strong>Netsuke</strong> representations <strong>of</strong> zodiac animalsbecame popular by the late eighteenth century,and it was considered lucky to wear a netsukerepresenting the year in which one was born.<strong>The</strong> earliest recorded netsuke artists to specializein these animals worked mainly in the Kyotoarea.<strong>The</strong> first to respond to Buddha was the rat,who is usually portrayed as a gentlecreature. Here the presence <strong>of</strong> tiny <strong>of</strong>fspringfurther s<strong>of</strong>tens the characterization.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 178 inches. Bequest<strong>of</strong> Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881, 81.1.34<strong>The</strong> ox is <strong>of</strong>ten found in <strong>Japan</strong>ese artbecause <strong>of</strong> its association with the Zenparable <strong>of</strong> the ox and the herder, which symbolizesa man taming his own spirit. <strong>The</strong> Soken Kishoidentifies this artist, Tomotada, as specializing inthe carving <strong>of</strong> oxen. His netsuke were highlyprized and frequently copied.This example has all the characteristics <strong>of</strong> agenuine Tomotada sculpture: the proportions areYr: Tigers are not native to <strong>Japan</strong>, but their9 ferocity and strength made them favoritesubjects in <strong>Japan</strong>ese art <strong>of</strong> the Edo period. Tigernetsuke are usually carved in a crouchingposition, the head turned into the curve <strong>of</strong> thebody. This feline, with its beetle-brow andmournful eyes, seems like a household pet,although strength is suggested in its haunchesand well-padded paws.Nothing is known about the artist, Raku, butthere are a number <strong>of</strong> tigers with features carvedin this manner that bear his name in a jaggedreserve, as here.Late eighteenth century. Ivory, height 13/8 inches.Signed: Raku. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910,10.211.10994 <strong>The</strong> hare is connected with legends aboutthe moon, in which it administers the task<strong>of</strong> keeping the disk clean. <strong>The</strong> moon hare, a<strong>Japan</strong>ese "Man in the Moon," is said to live along time, and to turn white at an advanced age.This netsuke, with its broad chest and powerfulbody, conveys the spirit <strong>of</strong> an animal preparedfor instant flight.Nineteenth century. Wood, height 21/8 inches. <strong>The</strong>Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Edward C.Moore, 1891, 91.1.988<strong>The</strong> dragon is the only mythical beastincluded in the zodiac. <strong>The</strong> traditional<strong>Japan</strong>ese interpretation has a flat head with twohorns extending down its back, long whiskers, ascaly, snakelike body with spines on its back,and four three-clawed feet (the Chinese imperialdragon has five-clawed feet). It is said to embodyboth male and female characteristics with unlimitedpowers <strong>of</strong> adaptation. This one is unusual,as it seems to be based on the seventeenthcenturydoughnut-shaped style <strong>of</strong> netsuke.Eighteenth century. Ivory, height 13/4 inches. <strong>The</strong> H.O.Havemeyer Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O.Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.787p Before the advent <strong>of</strong> Buddhism in <strong>Japan</strong>,snake deities were worshiped in earlyShinto rites. In Buddhist lore the snake came to21

\Irri~~~~~~~r cl-o~~~~~~~~~-cr~~~~~~.~~~~l,s~~~k

I o*loL

24be associated with "female" passions <strong>of</strong> angerand jealousy. However, to dream <strong>of</strong> a snake wasconsidered a good omen.This reptile's satisfied expression and swollenmidsection (more visible from the front) suggesta recent meal. <strong>The</strong> tiered undulations <strong>of</strong> itscoiled body form a compact mass perfect for useas a netsuke. This carving probably enjoyedconsiderable handling: for if the scales on theunderbelly are rubbed the right way, they feelsmooth; and if rubbed in the opposite direction,rough like those <strong>of</strong> a live snake.Late eighteenth century. Wood, length 21/4 inches. Gift<strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.2284{ Although <strong>Japan</strong>ese horses are short-leggedand stocky, they are nevertheless difficultto depict standing in compact netsuke form. Thiscomposition is similar to that <strong>of</strong> the tiger, as theline <strong>of</strong> the neck and head curves along the bodyto form a smooth oval.Tomotada worked mostly in ivory, a mediumin which he seems the most expressive. Hiswood netsuke, such as this horse, lack thedynamic quality found in his ivories.Eighteenth century. Height 17 inches. Signed:Tomotada. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.1645Although the zodiac sign is actually asheep, the animal portrayed is usually agoat, and the few legends associated with it arederived from the Chinese. In <strong>Japan</strong>, where goatflesh is not eaten and the hair scarcely used, theanimals rarely appear in any art form. This artist,however, specialized in them, masterfullyrendering the texture <strong>of</strong> their hair by meticulouslycarving the strands in layers. <strong>The</strong> horns,while sharp, lie gently on this goat's hunchedshoulders, following the curve <strong>of</strong> the spine.Nineteenth century. Signed: Kokei. Wood, length 13/4inches. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.2000r <strong>The</strong> monkey is much loved in <strong>Japan</strong>, andthe subject <strong>of</strong> many paintings and netsuke.<strong>The</strong> small, light-furred and short-tailed variety(Macaca fuscata) is found throughout the islands,and in the north is sometimes called the "snowmonkey." <strong>The</strong> year <strong>of</strong> the monkey is consideredunlucky for marriages, as the word for monkey(saru) has the same pronunciation as the verb "toleave," or "to divorce."Masatami delighted in carving this animal invarious textures. <strong>The</strong> face is molded in smoothplanes; the inlay <strong>of</strong> the eyes is black coral. <strong>The</strong>body is carved with every hair carefully delineated,and its forelegs are beautifully tapered,terminating in minutely articulated fingers andfingernails. <strong>The</strong> smoother, lighter chestnut,accented by a bug, <strong>of</strong>fers a contrast to the detailand darker color <strong>of</strong> the monkey.Nineteenth century. Ivory, length 21/4 inches. Signed:Masatami. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.1065A cock on a drum is both a zodiac sign andj4 a peace symbol. In China and <strong>Japan</strong>, thebeating <strong>of</strong> a drum was a call to arms or awarning <strong>of</strong> danger. In <strong>Japan</strong>ese folklore, whenthe unused drum became a perch for roosters,peace prevailed.Here, the bird's head, tucked into the plumpwing, is balanced by the high arch <strong>of</strong> the tailfeathers, which blend harmoniously into arounded form. <strong>The</strong> careful carving <strong>of</strong> the dragonon the sides <strong>of</strong> the drum is in opposition to thesmooth drumhead, creating a textural contrastfurther dramatized by the studs <strong>of</strong> black coralaround the rim.Late eighteenth century. Ivory, height 15/8 inches. <strong>The</strong>Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Edward C.Moore, 1891, 91.1.1015JX<strong>The</strong> Chinese attitude toward dogs, associatingthem with bad luck and ill health, wasgradually dispelled in <strong>Japan</strong>. Dogs becamesymbolic <strong>of</strong> loyalty and were much loved. <strong>The</strong>irreputation was considerably enhanced by theshogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. Born in 1646, inthe year <strong>of</strong> the dog, Tsunayoshi was told byBuddhist priests that his lack <strong>of</strong> a son might bedue in part to his killing <strong>of</strong> dogs in a former life,so he issued a proclamation protecting them.This group <strong>of</strong> frolicsome puppies by Tomotadais an extraordinary composition that has beencopied many times. From any angle the design isperfectly proportioned, and several naturalopenings allow it to be worn in different ways.Snapping jaws, tiny noses, and shell-like earsconvey the youth and energy <strong>of</strong> these two littleanimals at play.Eighteenth century, Ivory, length 13/8 inches. Signed:Tomotada. <strong>The</strong> H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest<strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.854<strong>The</strong> boar, the twelfth zodiac symbol, isthought to possess reckless courage. It isfound wild in western <strong>Japan</strong>, especially in theprovince <strong>of</strong> Iwami, where its tusks and teethwere carved by a group <strong>of</strong> netsuke artists.This slumbering beast, nestled snugly in a bed<strong>of</strong> boughs and ferns, reveals both a gentle humorand a sense <strong>of</strong> sheer brute force temporarilyrestrained. Although this design by Tomotadawas frequently copied, no other artist hascaptured the power <strong>of</strong> the original.Eighteenth century. Ivory, length 21/4 inches. Signed:Tomotada. Bequest <strong>of</strong> Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1891,81.1.91

Ryusa, named for the carver who originatedthe style, is a form <strong>of</strong> manju netsuke that isturned on a lathe. <strong>The</strong> broad, rounded edgeallows the artist to continue his design uninterruptedfrom front to back.This example, done with extraordinary skill, isprobably the work <strong>of</strong> Ryusa himself. Here thestippled surface gives the illusion <strong>of</strong> morningmist. <strong>The</strong> flowers and other vegetation, as well asthe praying mantis, were fashioned by carvingthe surface <strong>of</strong> the ivory in a higher relief than thebackground, which was stained to providetextural contrast and added dimension. <strong>The</strong>hollow center adds a dark distance, and becomespart <strong>of</strong> the composition. On the reverse, alsocarved in relief, is a scarecrow in a field.Eighteenth century. Ivory, diameter 2 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.127125

Founder <strong>of</strong> the Ch'an (Zen in <strong>Japan</strong>ese) sect <strong>of</strong>Buddhism in China, the Indian monk Bodhidharma,known in <strong>Japan</strong> as Daruma, traveled asa missionary from India to southern China aboutA.D. 520, but finding no welcome there, crossedthe Yangtze River to settle in the north. Thisnetsuke depicts him crossing the river on a reed.Bodhidharma, his robe folded over his hands,displays a stern countenance set in deep concentration.<strong>The</strong> rippling <strong>of</strong> the long robes suggestsmotion and also emphasizes the upright posture<strong>of</strong> the body, balanced precariously on the singlereed and braced against the wind.Nineteenth century. Ivory, height 17/ inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.73126

ne legend concerning Daruma tells <strong>of</strong> hismeditating for nine years facing the wall <strong>of</strong>a cave. During this period, he fell asleep andupon awakening, screamed in consternationbecause he had been unable to remain awake.Here, his rage is fondly reproduced. Althoughnetsuke usually depict him beardless, this renditiongives him eyebrows, a moustache, and ashort beard composed <strong>of</strong> small spiral curls, aform usually associated with the hair on earlysculptures <strong>of</strong> the Buddha. <strong>The</strong> eyes are sorrowfulrather than angry, and are marvelously expressivein their downward droop. <strong>The</strong> flow <strong>of</strong> thegarment is simple, but the careful execution <strong>of</strong>feet and hands with sharply defined nails is anindication <strong>of</strong> the increasing emphasis on realism.Gold lacquer is applied for color.Late eighteenth century. Wood, height 31/8 inches.Signed: Sensai to (literally,"Sensai's knife"). Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.234627

<strong>The</strong> most noticeable change in late eighteenthcenturyanimal netsuke is the use <strong>of</strong>realistic, or active poses rather than the morestatic, "at rest" poses that had been commonfrom the mid-eighteenth century. <strong>The</strong> twistedpose <strong>of</strong> this squirrel succeeds in capturing theanimal's nervous quality. <strong>The</strong> black-coral eyesprotrude and the ears and paws are extended,but the composition still retains its compactform. <strong>The</strong> squirrel's chubby legs and tiny,clenched paws make it a very appealing figure.Late eighteenth century. Ivory, height 11/2 inches. Gift<strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.52B irds other than sparrows and falcons, whichhave symbolic associations, are seldomfound in netsuke. This artist has portrayed akingfisher in a very simple and smooth form.<strong>The</strong> wings curve and blend into the body,creating a slick surface broken only by the cordopenings on the underside. Befitting this smiall,quick bird, the tiny black inset eyes add a quality<strong>of</strong> alertness.Nineteenth century. Ivory, height 23/8 inches. Signed:Yasuchika. <strong>The</strong> Howard Mansfield Collection;Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1936, 36.100.18328

This white rabbit is a masterpiece <strong>of</strong> understatedsimplicity and elegant design.Although very compact, it is subtle in its sophisticatedmodeling. <strong>The</strong> legs are tucked out <strong>of</strong>sight, but the long ears are articulated withloving attention. Despite the abstraction <strong>of</strong>shape, the proportions remain lifelike, and therabbit appears alert, as do most nineteenthcenturyanimals. <strong>The</strong> sharp eyes are inset withblack coral, and the whiskers and nostrilsdefined in black to stand out more clearly againstthe white ivory, which looks sensuously tactileeven in these photographs.Ohara Mitsuhiro (1810-75), who worked inOsaka, is one <strong>of</strong> the outstanding netsuke artists<strong>of</strong> the mid-nineteenth century. A versatile carver,he used many styles and techniques, in piecesthat could be incredibly complicated anddetailed, or as refined and simple as this rabbit.Mid-nineteenth century. Length 11/2 inches. Signed:Mitsuhiro and Ohara (in a seal). <strong>The</strong> Edward C.Moore Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Edward C. Moore, 1891,91.1.97529

ZE~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~OL~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~L

intaro, who was brought up in themountains, had superhuman strength. As asmall child, he could uproot trees, wrestle bears,and was constantly fighting other beasts andgoblins. Most <strong>of</strong>ten he is depicted overcomingthe tengu, which is part bird and part otheranimal or man, that lived deep in the mountainforests.Here, boy and beast are in the final stages <strong>of</strong> astruggle. Both are exceptionally well delineated.<strong>The</strong> boy's hair and features are sharplydescribed, and tortoise-shell eyes with blackinlaid pupils add a realistic touch. His body isrounded with exaggerated but s<strong>of</strong>tly contouredmuscles that are indicative <strong>of</strong> his strength. <strong>The</strong>tengu, on the other hand, is on its stomach withwings spread in the posture <strong>of</strong> weakness, andbends its head backward in a feeble attempt topeck at Kintaro. Every feather <strong>of</strong> the tengu iscarved individually, and small ivory inlays (seebelow) highlight its arms and legs, creating acontrast to the wood. <strong>The</strong> emphasis on realisticdetail and intricate carving, characteristic <strong>of</strong> earlynineteenth-century netsuke, adds complexity tothis piece, but does not detract from the vigor<strong>of</strong> the composition.Early nineteenth century. Wood, height 13/ inches.Signed: Hachigaku. <strong>The</strong> Sylmaris Collection, Gift <strong>of</strong>George Coe Graves, 1931, 31.49.1232

he kappa, a fantastic aquatic creature,appeared in netsuke during the nineteenthcentury. Traditionally, it has a tortoise body, froglegs, and a monkeylike head with a saucershapedhollow in the top. This indentationcontains fluid that makes the kappa ferociousand uncompromising. However, being <strong>Japan</strong>ese,it is very polite; when bowed to, it will bow inreply, losing the fluid and, consequently, itsstrength. <strong>The</strong> face is usually that <strong>of</strong> a poutingchild rather than a terrifying monster, and itwalks upright. Kappas are reputedly responsiblefor drownings, but can be propitiated bythrowing cucumbers, their favorite food, into thewater.In this superbly elegant and sophisticatednetsuke, no surface has been left uncarved. <strong>The</strong>head is gracefully modeled, and small ears peepout <strong>of</strong> the sharply defined striated hair. <strong>The</strong>body's texture appears to imitate a tortoise shell,and the froglike limbs end in webbed feet. <strong>The</strong>carving is sharp and precise, which is typical <strong>of</strong>mid-nineteenth century work, and one <strong>of</strong> thecharacteristics <strong>of</strong> the style <strong>of</strong> this artist.Mid-nineteenth century. Wood, height 17/ inches.Signed: Shoko. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910,10.211.185833

<strong>The</strong> unlikely combination at the left probablyalludes to an episode in the legend <strong>of</strong> Ryujin(see p. 14) in which the Dragon King's doctor, anoctopus, prescribes the liver <strong>of</strong> a live monkey asthe cure for an ailment. A jellyfish is sent to finda monkey, but fails in his mission, and the storyends there. However, the pair shown here is<strong>of</strong>ten depicted in netsuke, probably indicatingthat the octopus finally undertook the task itself.<strong>The</strong> excellence <strong>of</strong> this netsuke lies in theskillful use <strong>of</strong> dissimilar shapes and forms, andin the artist's ability to communicate some <strong>of</strong> theterror and physical pressures <strong>of</strong> the fight.(Struggle for survival is a common theme inRantei's netsuke.) <strong>The</strong> expressions areexaggerated, and the force with which themonkey pushes his adversary is seen in theindentation in the octopus's head.Unlike earlier Kyoto artists who concentratedon the larger, individual zodiac animals, Ranteiand his generation usually worked with combinations<strong>of</strong> figures in a smaller format. Despitethe small size, they were able to give theirnetsuke more expression and more realisticdetailing.Nineteenth century. Ivory, length 11/2 inches. Signed:Rantei. <strong>The</strong> Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest <strong>of</strong>Edward C. Moore, 1891, 91.1.962n <strong>Japan</strong>, the hawk is a symbol <strong>of</strong> masculinity,and hunting with hawks was a popular sportamong the samurai. This bird's great power isexpressed in its spread wings and cocked headglaring down at its prey, a dog. Its mouth andtongue are deeply undercut to emphasize thesharp curve <strong>of</strong> the beak. Black inlaid eyescontrast with the light ivory <strong>of</strong> the body, and astain accents the play <strong>of</strong> light and darkthroughout the composition. <strong>The</strong> placement <strong>of</strong>the hawk's claw in the dog's eye heightens thebrutality <strong>of</strong> the struggle.Nineteenth century. Ivory, height 2 inches. Signed:Hidechika. <strong>The</strong> H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest<strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.79635

n old man weary <strong>of</strong> carrying his bag <strong>of</strong>troubles rests for a moment. His burdentakes the form <strong>of</strong> oni, or demons, who are tryingto free themselves. One, stained green, has torn ahole in the bag and glares out between hisfingers with a single eye (below). Another isabout to grasp the old man by his coat collar.<strong>The</strong> man wears a netsuke and tobacco pouchmade <strong>of</strong> wood with tiny brass highlights(repeating the metal ornament on the largerversions). <strong>The</strong> arm <strong>of</strong> the grasping oni is <strong>of</strong>wood, and its wrist is encircled by an inlaidmetal bracelet. Inlays <strong>of</strong> various materials wereapplied only sparingly to eighteenth-centurynetsuke, but in the nineteenth century, artistsincreasingly used distinctive combinations as astatement <strong>of</strong> individual style.This subject was originated during the latterpart <strong>of</strong> the eighteenth century by Ryfikei whocarved it in dark-stained boxwood. This ivorycopy, with its metal inlays, called for techniquesnot associated with ivory carving, and is possiblythe product <strong>of</strong> two artists.Nineteenth century. Ivory, wood, and metal, height 11/4inches. Signed: Seikanshi. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage,1910, 10.211.907he sword is one <strong>of</strong> the three sacred symbols<strong>of</strong> imperial authority. From the earliest timesin <strong>Japan</strong>, a spiritual presence, or kami, has beenassociated with the forging <strong>of</strong> a blade. Thisnetsuke represents the creation <strong>of</strong> the sword"Little Fox," forged by the swordsmith KokajiMunechika (938-1014) for the emperor Ichij6Tenn6 (986-1011). It is said that the fox god Inarimanned the bellows during the making <strong>of</strong> theblade, and here his ghostly form hovers in thebackground.In this ryusa-style netsuke, Munechika isdepicted in the metal cut-out that fits into thesurface <strong>of</strong> the ivory. <strong>The</strong> figure <strong>of</strong> the fox, cut inthe ivory, is made all the more mysterious by thehollow, pierced ground, with its various intensities<strong>of</strong> dark and light.Nineteenth century. Ivory and metal, diameter 13/4inches. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.120337

1.11 e,4~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~8W.~ Ow., ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~::: -j_::iii- -''::-:i:--:iiiiii:-:i- -ii -: i--_ii::-i:.li:-,--~~~~~~~~~~~~~~W;3z~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~~~~~_:i:-i-_- i:--,ir i:- : :i- :::i:ii-_-:i-_i-: --:-,ii_:.ii ii::: :::i: ,, ?~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~LA~-- ::'::::-----:::::---4;jW~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~:::::::::-:;_::--:::-:I::: -::ii----,iiil1:t--:::: -:Ix ~~ ~ ~ ::i-i~iil --::--: ::::: :::

This superbly articulated rendition <strong>of</strong> askeleton astride a skull is a humorous statement<strong>of</strong> the transitory nature <strong>of</strong> life. <strong>The</strong> bonyhips <strong>of</strong> the skeleton are modestly covered with aloincloth, a reminder <strong>of</strong> its humanity and also aniconographic detail found on demonic figures <strong>of</strong>the eighth century. <strong>The</strong> careful definition <strong>of</strong> theskeletal structure demonstrates the knowledge <strong>of</strong>anatomy on the part <strong>of</strong> this artist, Rantei, who<strong>of</strong>ten created subjects dealing with death or thestruggle for survival (see p. 34).In this netsuke the head and arm were madeas a separate unit and then inserted at the top <strong>of</strong>the spine and into the shoulder. This constructionprovided movement, and also allowed forthe contraction and expansion caused by changesin humidity.Nineteenth century. Ivory, height 13/4 inches. Signed:Rantei. Bequest <strong>of</strong> Stephen Whitney Phoenix, 1881,81.1.72A ccording to legend, a group <strong>of</strong> seven godswhose origins derived from Brahminism,Taoism, Buddhism, and Shinto, appeared to theshogun Tokugawa Iemitsu (1603-51) in a dream.In explaining the dream, a courtier pronouncedthem the Seven Gods <strong>of</strong> Luck. Hotei, the mostpopular <strong>of</strong> the group, is commonly portrayed asa fat, jolly figure with an ample stomach andholding a fan. He is frequently surrounded bychildren, and carries a bag <strong>of</strong> twenty-one objectsrepresenting prosperity. Here, he is in his bag.This example by a well-known artist combineselegant simplicity and exquisite detail. <strong>The</strong>smiling fat face and the pudgy arm protrudingfrom the bag create an appearance <strong>of</strong> joviality.<strong>The</strong> well-carved folds and stitching on the baglend authenticity to its fabric, and the fine details<strong>of</strong> Hotei's features and fan provide a texturalcontrast to its smooth worn material. Thiscounterpoint <strong>of</strong> textures is <strong>of</strong>ten found in Mitsuhiro'swork.Nineteenth century. Ivory, height l1/8 inches. Signed:Mitsuhiro and Ohara (in a seal). <strong>The</strong> H.O. HavemeyerCollection, Bequest <strong>of</strong> Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929,29.100.84139

<strong>The</strong> small figure clinging to the top <strong>of</strong> thelong nose <strong>of</strong> the mask netsuke at the left isthe popularized form <strong>of</strong> Uzume-no-Mikoto, who,according to a well-known <strong>Japan</strong>ese legend,danced to entice the sun goddess Amaterasu out<strong>of</strong> a cave where she had hidden, thus deprivingthe world <strong>of</strong> light. Okame, as the deity is alsoknown, created such raucous merriment thatAmaterasu emerged, and light was restored.Certain Shinto songs and dances are said to traceback to those <strong>of</strong> Okame.Okame is shown grasping the nose <strong>of</strong> themask, which represents Saruta-Hiko-no-Mikoto,the Shinto god who blocked the crossways toheaven. <strong>The</strong> sun goddess asked Okame toconfront him and clear the way. This wouldpossibly explain the humorously erotic relationshipillustrated here, a theme commonly found innetsuke <strong>of</strong> the Edo period.This Okame is a playful young girl; herrounded body and chubby arms, hands, and feet,give her a childlike innocence that conflicts withthe scowling mask. By using opposites, the artist,Masanao, has created a successful satire.Nineteenth century. Wood, height 11/2 inches. Signed:Masanao. Bequest <strong>of</strong> Kate Read Blacque in memory<strong>of</strong> her husband Valentine Alexander Blacque, 1938,38.50.296H annya is a demon representing the spirit <strong>of</strong>a jealous woman. One <strong>of</strong> the most fearsome<strong>of</strong> all No masks, it is most <strong>of</strong>ten associated withthe play Dojoji, in which a young maiden falls inlove with a handsome priest. Enraged by hisresistance to her advances, she finally traps himunder the bell <strong>of</strong> the D6jo Temple. After turningherself into a snakelike dragon with the face <strong>of</strong> aHannya, she encircles the bell and burns him todeath with the heat <strong>of</strong> her anger.Hannya are among the most common subjects<strong>of</strong> mask netsuke. <strong>The</strong> one at the right is not atrue copy <strong>of</strong> a No mask as it lacks the reflectingmetal or gilded eyes usually found in No masks<strong>of</strong> supernatural beings. However, the carving issuperb: the strength <strong>of</strong> sculptural movementfrom the powerful forehead to the almost skulllikeform <strong>of</strong> the cheek area and jaw is the work<strong>of</strong> a skilled artist.Nineteenth century. Wood, height 17/8 inches. Gift <strong>of</strong>Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.238840

1:I41

<strong>The</strong> few dignified or graceful representations<strong>of</strong> women in netsuke are <strong>of</strong> heroines <strong>of</strong> theHeian period (794-1185), a time when womenenjoyed considerable success in the arts. Ono noKomachi (834-900) was a renowned court beautyas well as an accomplished poetess. At the height<strong>of</strong> her glory, she was said to be extravagant andproud, setting impossible tasks for her lovers,until one <strong>of</strong> them died in the pursuit <strong>of</strong> herfavors. Out <strong>of</strong> remorse, or perhaps as punishmentby the gods for her extreme vanity, shebecame destitute in her old age. In netsuke, sheis <strong>of</strong>ten portrayed as a toothless hag dressed inrags.This is a rare sympathetic interpretation <strong>of</strong> thepoetess in her last years. <strong>The</strong> carving <strong>of</strong> her faceis particularly sensitive, including a hint <strong>of</strong> adimple in her cheek, a poignant reminder <strong>of</strong> herformer beauty. Takehara Chikko is known for hisfigural netsuke <strong>of</strong> <strong>Japan</strong>ese legendary subjects.Late nineteenth century. Wood, height 31/2 inches.Signed: Chikko saku ("Chikk6 made"). Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs.Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.2336

This unusual figure wears a headdresscomprised <strong>of</strong> three mother-<strong>of</strong>-pearl disksinlaid in wood frames, in a shape based on that<strong>of</strong> a matoi, an implement used in victory celebrationsduring the Meiji period (1868-1912). On thedisks are scratched the characters for Dai NihonSensho iwai, which may be translated as "Celebrationfor <strong>Japan</strong>ese [War] Victory." <strong>The</strong> artist'sdates, 1871-1936, suggest that this netsuke wascarved to commemorate the <strong>Japan</strong>ese victory inthe Russo-<strong>Japan</strong>ese War <strong>of</strong> 1904-1905. <strong>The</strong>figure's face reflects the agony <strong>of</strong> war and war'sconflict with Buddhism, which is symbolized bythe whisk and the necklace <strong>of</strong> leaves.This is a striking interpretation, rendered withboth delicacy and force. <strong>The</strong> subject indicatesthat it was not intended for export, and its highquality is representative <strong>of</strong> many <strong>of</strong> the piecescreated by artists <strong>of</strong> the Meiji and Taisho (1912-26) periods who did not capitulate to theexpanding export market.Early twentieth century. Wood, height 41/8 inches.Signed: Sansho and a kakihan (stylized signature).Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.231943

iC) dire asiBC0?Xs U'IEs I4Bi\?I'r_s88s3;'?Sri p ii=a,: d%''\-?-??cr t?u g? ?'80 "?s aalc a "L i a"i ?sr' t t r5??-.*"' der? ,:?9Bf;x?r?? **i'p \rr8)s;- c9 P;-;1$4'arCidQbJ(b!g:tl_,i''YI

hen netsuke were introduced to Europe inthe Meiji period, variations on traditionalsubjects evolved that were thought moreappealing to Western taste. For example,Kohosai, who created this boar, felt that asomnulent, ferocious animal (see p. 7) would notbe appealing, so he developed a new approach.<strong>The</strong> boar's head is large compared to its bodysize, and the facial expression is amusinglyexaggerated. To embellish this netsuke, the artistincluded a decorated back covering with anelegant dragon pattern. Hanging beads aresimulated by colorful incrustations <strong>of</strong> semipreciousstones in the technique known asshibayama. <strong>The</strong> signature plaque on the undersidebridges the space between the legs and providesthe cord opening.Late nineteenth century. Ivory, length 21/4 inches.Signed: Kohosai and a kakihan (stylized signature).Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.899T he image <strong>of</strong> the elephant has stimulated the<strong>Japan</strong>ese imagination for centuries. EarlyBuddhist paintings and sculpture depict the deityFugen Bosatsu seated on the beast, and mythologicalanimals sometimes derive characteristicsfrom it (see p. 17). In the early part <strong>of</strong> theeighteenth century a pair <strong>of</strong> elephants was sentto <strong>Japan</strong> as a gift to the imperial family, andnetsuke <strong>of</strong> that animal could easily have beenbased on drawings from life.This is an interpretation <strong>of</strong> the allegoryconcerning truth and how man interprets it. <strong>The</strong>blind men are investigating an elephant in anattempt to describe it. <strong>The</strong>ir findings, <strong>of</strong> course,are based on which part they feel.<strong>The</strong> tininess <strong>of</strong> the figures against the beast'sexpansive body is meant to be as amusing as thehumor reflected in the animal's face. This is asensitive rendition by the founder and master <strong>of</strong>the renowned So school <strong>of</strong> netsuke carvers.Late nineteenth century. Ivory, height 15/8 inches.Signed: Kuku Joso to (literally, "Kuku Joso's knife").Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.900......?"~ ~ .~ ~ :: r b-- .~. x - w .. ~~'45

y the late Edo and early Meiji periods,competition among netsuke carvers hadexhausted conventional themes, and artistssearched for fresh subjects. During the 1850s thewell-known artist H6jitsu (died 1872), who waspatronized by the daimyo <strong>of</strong> the Tsugaru District<strong>of</strong> Mutsu Province, began to specialize in genrefigures, depicting in his sculptures the dailyactivities <strong>of</strong> townspeople. His work, supposedlyinfluenced by the genre painter Hanabusa Itcho(1651-1724) is refined, with few frills.This man applies salve to a painful area on hisneck. Although his face is contorted withsuffering, it is still well defined enough to be aportrait. <strong>The</strong> countermovement within the bodyis emphasized by the tilt <strong>of</strong> the shoulders and thefolds <strong>of</strong> the garment as it gathers in the man'slap. His slender wrist and forearm draped in arippling sleeve are elements <strong>of</strong> studied grace.Nineteenth century. Wood, height 11/4 inches. SignedHojitsu. Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.1823hile Hojitsu provided the impetus for theproliferation <strong>of</strong> genre subjects, JosoMiyasaki (1855-1910) further shifted theemphasis from the activities <strong>of</strong> the upper andmiddle classes to those <strong>of</strong> workmen and farmers.<strong>The</strong> man shown here, kneeling in <strong>Japan</strong>esefashion, is cutting a pumpkin on a board. Hisheadband, originally a sweatband, is traditionalamong the working class in <strong>Japan</strong> even today.From any angle, the netsuke displays greatvitality. <strong>The</strong> expression on the man's face-whichis only about /2 inch high-is intense, and hislong tapering fingers energetically grasp thevegetable as he cuts it.At a time when the export market demandedflashy inlays and overly decorated, intricatepieces, Joso concentrated on the smaller homemarket. Typically, his netsuke were <strong>of</strong> simplesubjects, exquisitely executed. Determinationand tension are expressed in the faces, finelymuscled bodies, and strong hands <strong>of</strong> his workers.Occasionally he carved other figures-a cryingchild or a blind man-but they are all treatedwith sympathy rather than ridicule.Late nineteenth century. Wood, height l1/4 inches.Signed: Jos6 yafu t6 (literally, "Joso the rural man'sknife"). Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.182746

okeisai Sansho (1871-1926), the creator <strong>of</strong>this netsuke, was known for his genrefigures. He tended to exaggerate facial characteristicsas a means <strong>of</strong> stylistic expression; here,for example, the twisted features suggestdrunkenness.<strong>The</strong> well-proportioned body clothed in acasually draped, simple garment is pure Sansho.<strong>The</strong> hair is stained black to emphasize theheadband, part <strong>of</strong> the workingman's costume.<strong>The</strong> bare, tightly curled toes grasp the ground tomaintain balance. <strong>The</strong> netsuke, howeverhumorous, may have a serious intent: it mighthave served as a reminder to its owner <strong>of</strong> howfoolish one looks when drunk.Late nineteenth century. Wood, height 31/4 inches.Signed: Sansho and a kakihan (stylized signature).Gift <strong>of</strong> Mrs. Russell Sage, 1910, 10.211.235347

BIBLIOGRAPHYJ.W. Hall, <strong>Japan</strong> from Prehistory to Modern Times, New York,1970H.L. Joly, Legend in <strong>Japan</strong>ese Art, London, 1908D. Keene, Landscapes and Portraits: Appreciations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Japan</strong>eseCulture, Tokyo and Palo Alto, 1971B.T. Okada, <strong>Japan</strong>ese <strong>Netsuke</strong> and Ojime: From the Herman andPaul Jaehne Collection <strong>of</strong> the Newark <strong>Museum</strong>, Newark, 1976G. Sansom, <strong>Japan</strong>: A Short Cultural History, rev. ed., New York,1962U. Reikichi, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Netsuke</strong> Handbook <strong>of</strong> Ueda Reikichi, trans. andadapted by R. Bushell, Tokyo, 1961T. Volker, <strong>The</strong> Animal in Far Eastern Art, reprint 1950 ed.,Leiden, 1975Puppies by Tomotada (see p. 22)48

v .As - -1:C( iLi<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Artis collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Art Bulletin ®www.jstor.org