The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 59

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 59

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 59

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

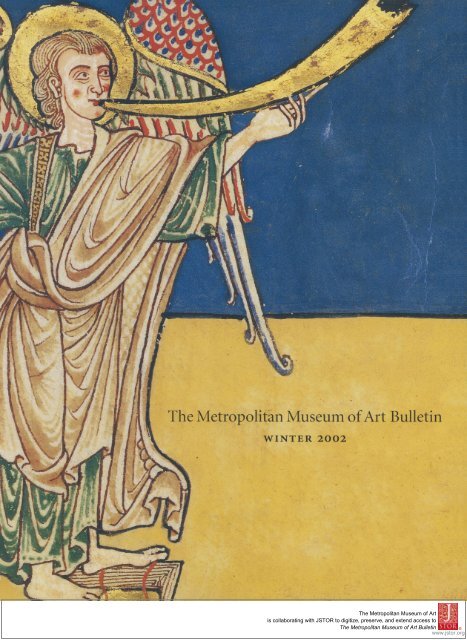

71ri/75~~, lThPerpltnMsufAtBlei;'/ Ift l I<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong>/ i\ g \ WINTER 2002<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> ®www.jstor.org

vPicturing the Apocalypse:Illustrated Leaves from aMedieval Spanish ManuscriptWilliam D. WixomMargaret LawsonTHE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Director's NoteTen years ago, when welcoming the Beatus manuscript leavesfeatured in this <strong>Bulletin</strong> to the <strong>Museum</strong> as a recent acquisition,I mentioned that their collective importance was such thatthree years <strong>of</strong> Cloisters acquisitions funds had been set asidefor their purchase. Selected leaves have since been included intwo major special exhibitions-"<strong>The</strong> Glory <strong>of</strong> Byzantium" in1997 and "Mirror <strong>of</strong> the Medieval World" in 1999-and beenpublished in the accompanying catalogues, but we have not yethad the opportunity to present the entire sequence <strong>of</strong> illuminationsin all <strong>of</strong> their visual splendor and expressive power.Now, we take the unusual step <strong>of</strong> devoting an issue <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Bulletin</strong> to a single work-and as it happens, the timing <strong>of</strong> thepublication is noteworthy as well. <strong>The</strong> title <strong>of</strong> this <strong>Bulletin</strong>,"Picturing the Apocalypse," carries an unavoidable resonancein the wake <strong>of</strong> the tragedies <strong>of</strong> last September. On the day <strong>of</strong>the attacks, whether watching on television or at closer, moredevastating range, we all sought ways to comprehend the magnitude<strong>of</strong> the disaster. We could not help but imagine the worldcaught up in an overwhelming chain <strong>of</strong> events that could leadto further, even broader catastrophes. We looked for solacewherever we could find it. In the days and weeks that followed,many people came to the <strong>Museum</strong> to be comforted, to achieveserenity, to be distracted by beauty.<strong>The</strong> Beatus manuscripts <strong>of</strong> the tenth to thirteenth centuryare illustrated commentaries on the Apocalypse, the final book<strong>of</strong> the New Testament. <strong>The</strong> illustrations depict the end <strong>of</strong> theworld quite literally, as described in the biblical text, with hailand fire, plagues <strong>of</strong> locusts, and trumpeting angels. Medievalreaders <strong>of</strong> our Beatus would no doubt have been terrified bywhat they saw on its pages, but also consoled by the promise <strong>of</strong>redemption <strong>of</strong>fered in the later chapters. We may believe ourselvesto be threatened by a different set <strong>of</strong> more technological,perhaps more daunting terrors-but let us not forget thatanthrax is one <strong>of</strong> the oldest recorded diseases, with symptomsdescribed in Exodus and known to Hippocrates. Some nightmares,in other words, remain constant.We are fortunate that William D. Wixom, who retired fromthe <strong>Museum</strong> in 1998 as the Michel David-Weill Chairman <strong>of</strong>the Department <strong>of</strong> Medieval <strong>Art</strong> and <strong>The</strong> Cloisters, could becoaxed back into service for this publication. Having recommendedthe leaves' purchase-emphatically-back in 1991, heis the ideal person to expound on their intriguing admixture <strong>of</strong>styles. Margaret Lawson, assistant conservator in the ShermanFairchild Center for Works on Paper and Photograph Con-servation, takes a different approach to the manuscript, onethat could almost be described as alchemical. Together, theirtwo perspectives provide a superb introduction to the workawork that cannot, however, be properly appreciated withoutvisits to <strong>The</strong> Cloisters and to the galleries <strong>of</strong> medieval art in themain building, where the leaves are exhibited one or two at atime, on a rotating basis.PHILIPPE DE MONTEBELLODirectorThis publication was made possiblethrough the generosity <strong>of</strong> theLila Acheson Wallace Fund for<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>established by the c<strong>of</strong>ounder <strong>of</strong>Reader's Digest.<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong><strong>Bulletin</strong>Winter 2002Volume LIX, Number 3(ISSN 0026-1521)Copyright ? 2002 by <strong>The</strong><strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>.Published quarterly. Periodicalspostage paid at New York, N.Y., andAdditional Mailing Offices. <strong>The</strong><strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong>is provided as a benefit to <strong>Museum</strong>members and is available by subscription.Subscriptions $25.00 ayear. Single copies $8.95. Fourweeks' notice required for change<strong>of</strong> address. POSTMASTER: Sendaddress changes to MembershipDepartment, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong><strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, 1000 Fifth Avenue,New York, N.Y. 10028-0198. Backissues available on micr<strong>of</strong>ilm fromUniversity Micr<strong>of</strong>ilms, 300 N. ZeebRoad, Ann Arbor, Mich. 48106.Volumes I-XXXVII (1905-42) availableas clothbound reprint set oras individual yearly volumes fromAyer Company Publishers Inc.,50 Northwestern Drive #1o, Salem,N.H. 03079, or from the <strong>Museum</strong>,Box 700, Middle Village, N.Y. 11379.General Manager <strong>of</strong> Publications:John P. O'NeillEditor in Chief <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Bulletin</strong>:Joan HoltEditor: Jennifer BernsteinProduction: Peter Antony, Joan Holt,and Sally VanDevanterDesktop Publishing Assistant:Minjee ChoDesign: Tsang Seymour DesignAll photographs <strong>of</strong> works in the<strong>Museum</strong>'s collection, unless otherwisenoted, are by the PhotographStudio <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong><strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>. New photography<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Museum</strong>'s Cardena Beatusleaves, including the wraparoundcover detail, is by Eileen Travell <strong>of</strong>the Photograph Studio. <strong>The</strong> photograph<strong>of</strong> the acanthus plant on p. 13is by Peter Zeray <strong>of</strong> the PhotographStudio. Photographs <strong>of</strong> the MorganBeatus (figs. 19, 22, 25, 27, 29, 31, 34,35, 38, 39, 41, 44) are courtesy <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong>Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.Additional credits: BibliothequeNationale de France, Paris, fig. 14;<strong>The</strong> Cleveland <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>,fig. 15; Courtauld Institute <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>,University <strong>of</strong> London, fig. 24;National Monuments Record,English Heritage, Swindon, fig. 21;Jerrilyn D. Dodds, fig. 20; <strong>The</strong> JohnRylands University Library <strong>of</strong>Manchester, figs. 32, 45; GabinettoFotografico, Soprintendenza Beni<strong>Art</strong>istici e Storici di Firenze,Florence, fig. 18; Hirmer Fotoarchiv,Munich, figs. 10, 11, 13, 26, 40;Institut Amatller d'<strong>Art</strong> Hispanic,Barcelona, figs. 12, 23, 28, 43;Margaret Lawson, figs. 46-62;<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, Boston,fig. 33; Staatsbibliothek Bamberg,fig. 3; Bruce White, fig. 5On the front and back covers: Detail<strong>of</strong> Cardena Beatus illumination(1991.232.12b; see p. 40)<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to<strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> <strong>Bulletin</strong> ®www.jstor.org

THEAPOCALYPSE". . . the key <strong>of</strong> things past, the knowledge<strong>of</strong> things to come; the opening <strong>of</strong> what is sealed,the uncovering <strong>of</strong> what is hidden."- JOACHIM OF FIORE, LATE 12TH CENTURY

,uII1jI\I- -1I ,^^\/~~~~~~~I~~~~~1II//a,I S..i'~IN". a,, I .-^^'^^^^^F~-1I..I- ..- -I.:,"I.II.jl--el/^v^/rV%.^r,.~ ~ ~ 4'1, I .4-/SnfA'A~~~~~'.1IrT6t-'qlk/F', JOP

APOCALYPTIC LITERATURE is a class <strong>of</strong> Jewish andChristian texts produced from about 250 B.C.through the early centuries after Christ. <strong>The</strong>seworks were intended to assure the faithful, intheir persecution and suffering, <strong>of</strong> God's righteousness and thefuture triumph <strong>of</strong> Israel, or the messianic kingdom. Prominentexamples <strong>of</strong> the genre include the Old Testament's Book <strong>of</strong> Daniel,parts <strong>of</strong> the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the last book <strong>of</strong> the NewTestament: the Apocalypse, or Book <strong>of</strong> Revelation. We knowfrom the first chapter <strong>of</strong> the latter, quoted in part on page 23,that it was written on the island <strong>of</strong> Patmos, in the southeasternAegean Sea, by a prophet named John, who since the secondcentury has traditionally been identified with the apostle <strong>of</strong>Christ and saint who wrote the Fourth Gospel. Scholars datethe work to the last quarter <strong>of</strong> the first century A.D.<strong>The</strong> first, second, and third <strong>of</strong> the Apocalypse's twenty-twochapters contain instructions and admonitions that "a greatvoice, as <strong>of</strong> a trumpet," commanded the author to deliver to thebishops <strong>of</strong> the seven Christian churches in Asia Minor:Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamus, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia,and Laodicea. Succeeding chapters project prophecies andvisions <strong>of</strong> the future for the church <strong>of</strong> Christ, including a vari-ety <strong>of</strong> cataclysmic events, the destruction <strong>of</strong> Christ's enemies,the end <strong>of</strong> the world, and the triumph <strong>of</strong> the heavenlyJerusalem. <strong>The</strong> intensely vivid descriptive imagery is dramaticand <strong>of</strong>ten horrendous in its details. Actual wars, plagues, andother real-life calamities over the centuries have led many toseek correlations with John's prophetic text in their owncontemporary world. Facing the colorplates after this introductoryessay are selected quotations that provide the characteristicvisionary flavor <strong>of</strong> John's text. <strong>The</strong> excerpts are from anEnglish translation <strong>of</strong> Jerome's original Latin Vulgate Bible <strong>of</strong>the late fourth century, which was widely used throughout theMiddle Ages.<strong>The</strong> visual adoption <strong>of</strong> individual subjects and motifsspringing from John's text was well under way in the EarlyChristian and early medieval eras, as evidenced in the monumentalarts <strong>of</strong> wall painting and mosaic, particularly in thechurches <strong>of</strong> Rome. It is not surprising, therefore, to see in subsequentperiods the use <strong>of</strong> select apocalyptic motifs on altarfurnishings (frontals and crosses) and in the book arts (coversand pages <strong>of</strong> Bibles, Gospel books, and Apocalypse manuscripts),as well as in sculpted church portals and capitals. <strong>The</strong>reare several examples in the collections <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> <strong>Metropolitan</strong><strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong> and <strong>The</strong> Cloisters. Especially dramatic is anivory book-cover plaque (fig. 1) probably made in southernItaly (possibly in Benevento) between 975 and iooo, whichFIGURE 1Cross Plaque with Lamb <strong>of</strong> God andSymbols <strong>of</strong> the Evangelists, froma book cover. Southern Italian(Benevento?), 975-100ooo. Ivory; 91/4 x53/8 in. (23.5 x 13.7 cm). MMA, Gift <strong>of</strong>J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.38)illustrates the four "living creatures" <strong>of</strong> the Apocalypse (Apoc.4.6-8) surrounding the Lamb <strong>of</strong> God. <strong>The</strong>se creatures have tra-ditionally been associated with the four evangelists: Matthew(the winged man or angel), Mark (the winged lion), Luke (thewinged ox), and John (the eagle). On the <strong>Museum</strong>'s plaque,each creature holds a book that signifies the correspondingevangelist's Gospel.<strong>The</strong>re is a long history <strong>of</strong> representing the four evangelistsin this way, in various media; they appear, for example, inChristian mosaics from as early as the fifth century. Bothexegetical tradition (as in the writings <strong>of</strong> the fathers <strong>of</strong> theLatin church) and eschatological concern (fear <strong>of</strong> death andfinal judgment) underlie such depictions, in that the visualOPPOSITE: Detail <strong>of</strong> a leaf from the Cardena Beatus manuscript (1991.232.7a; see p. 30)-5-

FIGURE 2Dragon (detail). Spanish (Le6n-Castile, Burgos, monastery <strong>of</strong> SanPedro de Arlanza), 1200-1220.Fresco, transferred to canvas; 6 ft.10 in. x l10 ft. 5 in. (2.1 x 3.2 m).MMA, <strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, 1931(1931.38.1)portrayals gave concrete form to the biblical imagery. PopeGregory I postulated that while a scriptural image teachesthose who can read, an actual image informs those who cannotread but can see. <strong>The</strong> depiction <strong>of</strong> the Lamb <strong>of</strong> God with theevangelists' symbols reminded viewers <strong>of</strong> the glory and themystery <strong>of</strong> God: "And the four living creatures had each <strong>of</strong>them six wings; and round about and within they are full <strong>of</strong>eyes. And they rested not day and night, saying: Holy, holy,holy, Lord God Almighty, who was, and who is, and who is tocome" (Apoc. 4.8).<strong>The</strong> characterization <strong>of</strong> Satan as a dragon who does battle2 with the archangel Michael (Apoc. 12.7-12, 20.2) also elicitedvisual treatment. An imposing dragon fresco in the CloistersCollection (fig. 2), originally from Arlanza, in Burgos, mayhave served more than a delightful heraldic purpose; it mayalso have reflected apocalyptic imagery from beyond theIberian Peninsula, as is suggested by comparison with a 106-page Ottonian Apocalypse manuscript <strong>of</strong> about 1020 that hasbeen preserved in Bamberg since its donation by EmperorHenry II (r. 1014-24) and his wife, Kunigunde, to the CollegiateChurch <strong>of</strong> Saint Stephen. On the folio in question (fig. 3), boththe dragon and the archangel appear twice, in mirror image.It is in such illustrated manuscripts as that in Bamberg thatmotifs from the Apocalypse found their fullest, most vividexpression. In these works, assorted texts and images becamemnemonic aids in a way that was entirely typical <strong>of</strong> medievalbelief systems. Apocalypse manuscripts took varied forms,which scholars have grouped into "families," with extant ex-amples dating from the first quarter <strong>of</strong> the ninth centurythrough the early fourteenth century. One particularly splendidGothic work, produced in Normandy in about 1320, isin the Cloisters Collection (see fig. 4). This brilliant picturealbum includes only brief quotations from the Apocalypse andno excerpts from any <strong>of</strong> the later commentaries on John's text.More extensive Apocalypse quotations are the foremost ele-3 ment <strong>of</strong> the so-called Beatus manuscripts, books <strong>of</strong> parchmentFIGURE 3pages that also include excerpts from the commentaries.Saint Michael's Battle with the Dragi on, Scholars agree that this composite work was edited andfrom the Bamberg Apocalypse.German (monastery <strong>of</strong> arranged between 776 and 786 by an Asturian monk and pres-Reichenau),ca. 1020. Temperand gold on byter called Beatus <strong>of</strong> Liebana (d. ca. 798), whose biography isparchment; folio 115/8 x 8 in. (29.5 x something <strong>of</strong> a mystery. Near the end <strong>of</strong> his life, he was engaged20.4 cm). Staatsbibliothek Bamberg in a doctrinal controversy with proponents <strong>of</strong> Adoptionism(MS Bibl. 140, fol. 3ov, detail)regarding the nature <strong>of</strong> Christ-specifically, whether Jesus wasdivine from birth or was purely human until God "adopted"him. In Beatus's compilation, an affirmation <strong>of</strong> orthodox belief,especially in eschatological issues, was paramount. As varioustenets, including the nature <strong>of</strong> Christ's divinity, were being-6 -

threatened at the time both by heretics among the Christiansand by "infidels" (Muslims), the Beatus manuscripts servedeven more plainly as a bulwark for the orthodox, though thethreats themselves were never mentioned in the text or in thecaptions for the illustrations.<strong>The</strong> commentary portion <strong>of</strong> the Beatus text consists <strong>of</strong>interpretations <strong>of</strong> the quoted biblical passages cast as Christianallegories, which the compiler appropriated from patristicsources in accordance with established exegetical tradition.<strong>The</strong> sources that Beatus acknowledged in his preface includethe biblical translator Jerome (ca. 347-419/20) and Jerome'sfellow Latin church fathers Augustine (354-430; bishop <strong>of</strong>Hippo, in Numidia, North Africa), Ambrose (339-397; bishop<strong>of</strong> Milan), and Gregory I (the Great; 540-604; pope <strong>59</strong>0-604),as well as Tyconius (active ca. 380 in Numidia), Fulgentius(ca. 540/60-ca. 619; bishop <strong>of</strong> Ecija, in Spain), and Isidore(ca. 560-636; archbishop <strong>of</strong> Seville). Twenty-six illuminatedmedieval copies <strong>of</strong> this compilation are preserved, withillustrations painted in tempera and occasionally heightenedwith gold. <strong>The</strong> pictorial imagery-literal recapitulations <strong>of</strong> thefantastic visions <strong>of</strong> the biblical text-has little or no correlationwith the commentaries.<strong>The</strong> Beatus manuscripts have been designated by a leadingscholar in the field as "the illustrated text <strong>of</strong> medieval Spain."Originating in the mid-tenth century in the kingdom <strong>of</strong>Asturias-Leon, just beyond the northern reaches <strong>of</strong> the Islamicconquest, these manuscripts continued to be produced untilthe early thirteenth century. In the best examples, the illustrationsmay be seen as a match for John's vivid words. <strong>The</strong> textand the miniatures together depict an extraordinary effort onthe part <strong>of</strong> believers against the evils <strong>of</strong> false prophets, the beast(later interpreted as the Antichrist), and other instruments <strong>of</strong>Satan. <strong>The</strong> believers' final victory is registered in confidentscenes <strong>of</strong> exaltation <strong>of</strong> the heavenly Jerusalem and praise <strong>of</strong> themystic lamb (see p. 44).Beatus wrote in the preface to his compilation that it was"for the edification <strong>of</strong> the brethren"-meaning for monks'nonliturgical reading and private contemplation. Indeed, whileproviding a method for remembering the historical, moral,and spiritual import <strong>of</strong> biblical and patristic knowledge, thevolume also became a cherished and enriching fixture <strong>of</strong>monastic life. Yet more than a century earlier, at the FourthCouncil <strong>of</strong> Toledo in 633, the Visigothic church had establishedthe Apocalypse as a canonical book to be read in church fromEaster to Pentecost. <strong>The</strong> symbiosis <strong>of</strong> these two functions-nonliturgical and liturgical-may account in part for theexplosion <strong>of</strong> illustrative vigor in the manuscripts.FIGURE 4<strong>The</strong> Fourth Trumpet, from theCloisters Apocalypse. French(Normandy), ca. 1320. Tempera, gold,silver, and ink on parchment; folioapprox. 121/2 x 9 in. (31.8 x 22.9 cm).MMA, <strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, 1968(68.174, fol. 14r, detail)For the most part, the early Beatus images were rendered inresonant color and with an emblematic simplicity that scholarsbelieve was probably inherited from a lost North Africantradition in Apocalypse manuscripts. <strong>The</strong> vitality and inten-sity <strong>of</strong> these very explicit illustrations, many <strong>of</strong> them full pageand some spread over two pages, rest on their striking linearpatterns, emphatic contours, and sometimes strident contrasts<strong>of</strong> a restricted number <strong>of</strong> flat, mostly "hot" colors. <strong>The</strong> midtenth-centuryBeatus in the Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork, is an outstanding example (see figs. 19, 22, 25, and so on).Nuance, shading, volume, and perspective (both linear andatmospheric) were irrelevant to illuminators working in thisearly style.Curiously palatable to these intrepid artists, however, werecertain Islamic motifs and pictorial details, including thesenmurv (part bird, part lion), the eagle pouncing on a gazelle,the silhouetted tree, the equestrian warrior with streamersflowing from his diadem, and such architectural elementsas stepped crenellations and horseshoe arches. Several <strong>of</strong> thesemotifs may have been inspired directly by Islamic textilesand reliefs or conveyed indirectly from earlier Byzantineand Sasanian works by way <strong>of</strong> Islamic culture and its wideMediterranean inheritance. <strong>The</strong> architectural imagery mayhave referred to Islamic elements already assimilated intoChristian buildings <strong>of</strong> the tenth century in the northern7-

FIGURE 5Fructuosus (painter; Spanish?).Ferdinand, Sancha, and the Scribe,from <strong>The</strong> Prayer Book <strong>of</strong> Ferdinandand Sancha. Spanish (Leon-Castile,Sahagun?, monastery <strong>of</strong> SantosFacundo y Primitivo?), 1055.Tempera on parchment; folio1214 x 77/8 in. (31 x 20 cm).Biblioteca Universitaria de Santiagode Compostela (Rs. 1, fol. 3v, detail)regions <strong>of</strong> Spain (see fig. 20 on p. 15). <strong>The</strong> ongoing hostility betweenthe Christian and Muslim worlds at the time is obviouslynot reflected in these borrowings.Beatus manuscripts in this early style, which erupted nearthe borders <strong>of</strong> Christian Spain, have typically been labeled"Mozarabic"-a misnomer, because the Mozarabs, meaning"the Arabicized," were Christians living in the Iberian Peninsulaunder direct Muslim rule. To escape persecution many <strong>of</strong> thesepeople emigrated to the Christian regions <strong>of</strong> the north, wherethe illustrated Beatus manuscripts were produced. <strong>The</strong> "Mozarabic"designation has been retained, however, by a number <strong>of</strong>scholars for works dating from the tenth century to about1100. In fact, roughly the last sixty years <strong>of</strong> this period witnessedtwo styles that were juxtaposed and combined: late "Mozar-abic" and early Romanesque. Later in the twelfth century, theBeatus illustrations moved even further away from the insular"Mozarabic" mode and increasingly incorporated stylisticfeatures <strong>of</strong> pan-European Romanesque painting.<strong>The</strong> loose parchment leaves illustrated in color after page 13were produced in this later period. <strong>The</strong>y once belonged to aBeatus manuscript said to have come from San Pedro de Cardefna,a monastic foundation that flourished from the tenthcentury onward a short distance from the city <strong>of</strong> Burgos, in theregion <strong>of</strong> Castile (referred to herein as Leon-Castile; the kingdom<strong>of</strong> Leon had already absorbed Asturias in the previouscentury and would be united with Castile, to its east, in fits andstarts beginning in the eleventh). Presumably the manuscriptwas copied and illuminated by monks working in the scriptorium<strong>of</strong> this or another monastery in the immediate vicinity.San Millan de la Cogolla has been proposed, less compellingly,as an alternative to Cardefna.This manuscript, which we shall call the Cardefna Beatus,was partially dispersed in the 187os. <strong>The</strong> majority is now in theMuseo Arqueologico Nacional, Madrid, and other leaves residein the collection <strong>of</strong> Francisco de Zabalburu y Basabe in theBiblioteca Heredia Spinola, Madrid. Purchased in Paris in 1991,the <strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong>'s pages previously had been in distinguishedFrench collections, namely those <strong>of</strong> Victor MartinLe Roy at Neuilly-sur-Seine and his son-in-law, Jean-JosephMarquet de Vasselot, in Paris. (<strong>The</strong> latter was a curator <strong>of</strong>medieval art at the Musee du Louvre, Paris.) <strong>The</strong> New Yorkleaves, along with the other fragments in Madrid, have beenrecognized in the literature since 1871 (see references on p. 56).A facsimile <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the extant folios and cuttings from theCardefna Beatus, recombined in close to the original order, hasrecently been published by Manuel Moleiro in Spain. <strong>The</strong>accompanying book <strong>of</strong> essays, as well as the forthcoming finalvolume <strong>of</strong> a corpus <strong>of</strong> all known Beatus manuscripts by JohnWilliams, covers codicological, paleographic, textual, iconographic,and stylistic matters; our particular concern here willbe with iconography and style.IN THE EARLY MEDIEVAL period, from the ninth centuryon, the illusionistic aspects <strong>of</strong> Carolingian manuscriptpainting, which had initially been inspired byclassical pictorial concepts and conventions, assertedthemselves to varying degrees in manuscripts painted in portions<strong>of</strong> northern Europe, especially in Ottonian Germany,Anglo-Saxon England, and Romanesque France. But except forthe system <strong>of</strong> framed miniatures and the wide color bands forbackgrounds that were ultimately derived from Roman painting<strong>of</strong> the fifth century A.D. (as seen in the Vatican Virgil,Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Lat. 3225)-and in spite <strong>of</strong>8 -

FIGURE 6 FIGURE 7Angel, from the Cardena Beatus. Angel, from the Cardena Beatus.MMA (1991.232.3a, detail; see p. 22) MMA (1991.232.nb, detail; see p. 38)certain iconographic carryovers-the "Mozarabic" Beatusillustrations, with their powerful yet seemingly naive means,both linear and spaceless, were mostly distinct and separatefrom the early Carolingian stylistic tradition.Beatus manuscripts <strong>of</strong> the twelfth century altered the"Mozarabic" style while building on the few earlier indigenousand tentative efforts to assimilate both Carolingian and contemporaryByzantine styles, such as the portraits <strong>of</strong> the scribeand patrons in <strong>The</strong> Prayer Book <strong>of</strong> Ferdinand and Sancha (seefig. 5). Produced in Leon-Castile in 1055, this work initiated atrend toward a different kind <strong>of</strong> expressive power and elegance,which gained in momentum over the next century.Speculations concerning the historical background <strong>of</strong> thisdevelopment are several. One possible factor is that the fervorfor the Christian reconquest <strong>of</strong> the peninsula had diminishedin this later period with the establishment <strong>of</strong> a cautious equilibriumbetween the Christian and Muslim powers. Another isthat the monastic reforms <strong>of</strong> the Benedictine order had spreadsouthward from Cluny, in Burgundy; by 1030 they hadappeared at one <strong>of</strong> the key monasteries <strong>of</strong> Leon-Castile, SanPedro de Cardefna. <strong>The</strong> appointment <strong>of</strong> Cluniac abbots inseveral widespread bishoprics in the north <strong>of</strong> Spain broughtoutside influence in terms <strong>of</strong> the liturgy: the Visigothic ritewas replaced in 1o8o, at the insistence <strong>of</strong> Pope Gregory VII,with the Roman liturgy. Also, and more gradually, there werechanges in paleography and initial ornamentation. <strong>The</strong>sechanges were paralleled in mid-twelfth-century architecturalsculpture that was stylistically derived from the abbey at Cluny,as seen in two Leonese monasteries, San Salvador de Oiia and,again, San Pedro de Cardefa. Finally, the next and last generation<strong>of</strong> Beatus illustrations became the locus for a creativeamalgam <strong>of</strong> elements, both Leonese and pan-European.Of course, as in the earlier period, the later Beatus paintingsexhibit a clear variation in their level <strong>of</strong> quality, especiallywith respect to the characteristics <strong>of</strong> line and color.When considered in its entirety, the Cardefna Beatus alsoshows something <strong>of</strong> this variation in quality. Nevertheless,many <strong>of</strong> its illuminations, including those reproduced incolor after this essay, are remarkable for their refinement andcontrolled expression.Each <strong>of</strong> the Beatus illustrations in the <strong>Metropolitan</strong><strong>Museum</strong> may be traced to a comparable subject that appearsin one or more <strong>of</strong> the earlier, "Mozarabic" Beatus manuscripts.<strong>The</strong>se correspondences in imagery and iconography aredemonstrated on pages 15 to 45 with details from the MorganBeatus, which is one <strong>of</strong> the earliest preserved illustrated examples.<strong>The</strong> many similar arrangements and devices foundin these comparisons attest to the strength <strong>of</strong> the visually literalresponse to the text that was exercised over more than twocenturies. For instance, on the recto <strong>of</strong> the first folio <strong>of</strong> theCardefna Beatus (reproduced on p. 14), the unmistakable referenceto Islamic architecture in the repeated horseshoe arches,one set behind the other, is a "Mozarabic" carryover (see figs. 19,20 on p. 15).<strong>The</strong> style <strong>of</strong> the illustrations in the Cardefia Beatus is anentirely different concern from their iconography. <strong>The</strong> delicatepen-drawn heads and coiffures and the crosshatched shadingin some <strong>of</strong> the draperies show a stylistic homogeneity, eventhough they are not necessarily by the same hand. Distinctfrom this are two specific substyles, or manners, <strong>of</strong> renderingthe figures themselves and their draperies. A division <strong>of</strong> laborbetween two or more artists may be the explanation.<strong>The</strong> first substyle, perhaps the earlier or more conservativeone, may be observed in the five miniatures reproduced onpages 22, 24, 26, 28, and 30. <strong>The</strong> standing figures in this grouptend to be columnar. <strong>The</strong> tightly wrapped draperies consist <strong>of</strong>red and blue lines over a white ground, with the red and bluedistributed evenly, on all pieces <strong>of</strong> clothing, rather than usedto distinguish one garment from another. <strong>The</strong> lines <strong>of</strong>tenculminate in concentric ellipses delimiting blank white ovals,which represent and emphasize the thighs, hips, and lowerarms (see fig. 6). <strong>The</strong> result is a variation on the clinging,9 --

FIGURE 8Kneeling King, from an Epiphanyrelief. Spanish (Le6n-Castile,Burgos, Cerezo de Riotir6n), thirdquarter <strong>of</strong> 12th century. Limestone;h. 491/2 in. (125.8 cm). MMA, <strong>The</strong>Cloisters Collection, 1930 (30.77.6)FIGURE 9Enthroned Virgin and Child, from anEpiphany relief. Spanish (Le6n-Castile,Burgos, Cerezo de Riotir6n), thirdquarter <strong>of</strong> 12th century. Limestone;h. 541/8 in. (137.2 cm). MMA, <strong>The</strong>Cloisters Collection, 1930 (30.77.8)FIGURE 10Figure <strong>of</strong> Christ in Majesty, WestFacade, Church <strong>of</strong> Santiago. Spanish(Le6n-Castile, Palencia, Carrion delos Condes), 1170-80"damp-fold" style <strong>of</strong> drapery that was initially described byWilhelm Koehler in 1941.<strong>The</strong> second, more forward-looking substyle may be seen inthe eight miniatures reproduced on pages 16, 21, 32, 34, 36, 38,40, and 44. <strong>The</strong> delineation <strong>of</strong> the figures in this group is moredescriptive. <strong>The</strong> suggestion <strong>of</strong> drapery's natural fall into pleatsand bunches is distantly classical and far less abstract than inthe first group. While the figures in the second group are justas colorful, different elements <strong>of</strong> apparel are given distinct colors.Thus, a classical pallium, or mantle, might be shown inred, with white used for highlights, while the undergarment ortunic might be depicted in green, with white again used for thehighlights (see fig. 7).<strong>The</strong> character <strong>of</strong> the two substyles may be further understoodby observing parallels in Leonese and Castilian objects inother media, such as stone sculptures, ivory carvings, wallpaintings, and enameled goldsmiths' work. A contemporarysculptural Epiphany from Cerezo de Riotiron, on view at <strong>The</strong>Cloisters, simultaneously exhibits aspects <strong>of</strong> both manners(see figs. 8, 9). <strong>The</strong> kneeling king, as well as the side view <strong>of</strong> theenthroned Virgin (fig. 30 on p. 29), reveals an approach todrapery that is closely akin to the first manner in the CardefinaBeatus in its utilization <strong>of</strong> elliptical lines and smooth ovoidsfor the shoulders, elbows, and thighs. Yet at the same time aparallel for the second Cardefna manner can be seen in thepleats <strong>of</strong> the Virgin's veil and the overlapping folds about herfeet. <strong>The</strong> two manners again appear side by side in theroughly contemporary exterior reliefs <strong>of</strong> the church <strong>of</strong>Santiago in Carrion de los Condes, as suggested by JohnWilliams. One <strong>of</strong> the apostles there particularly recalls thedamp-fold manner <strong>of</strong> the Cardenia miniatures (see fig. 28 onp. 27), and the second manner finds a special resonance in theheavily pleated draperies <strong>of</strong> the imposing central relief <strong>of</strong>Christ in Majesty (fig. io). <strong>The</strong>re are still other examples <strong>of</strong> thisdual stylistic emphasis in contemporary monuments atOviedo and San Antolin de Toques (see figs. 11, 12). <strong>The</strong> twomanners are combined into a nearly seamless, organic whole inthe champleve enamels <strong>of</strong> Christ and the apostles from theurna (tomb) <strong>of</strong> Saint Dominic <strong>of</strong> Silos, produced in Silos orBurgos around 1150-70 and preserved in the Museo de Burgos.- 10 -

FIGURE 11 FIGURE 12Column Figures <strong>of</strong> Saints Peter Crucifixion Group. Spanish (Le6nandPaul, Chapel <strong>of</strong> San Miguel, Castile, Galicia-Asturias, monas-Cdmara Santa, Oviedo Cathedral. tery <strong>of</strong> San Antolin de Toques),Spanish (Le6n-Castile, Asturias, late 12th centuryOviedo), 1165-75FIGURE 13Arca Santa <strong>of</strong> Oviedo (detail).Spanish (Le6n-Castile, Asturias),late nth or early 12th century. Blackoak and gilded silver; h. (overall)283/4 in. (73 cm). Camara Santa,Oviedo CathedralNot new to Leon-Castile, this composite style had antecedentsin Leonese ivories dating from the mid-eleventh tothe early twelfth century (see fig. 42 on p. 41); in the previouslymentioned Prayer Book <strong>of</strong> Ferdinand and Sancha <strong>of</strong> 1055(fig. 5); and in the gilded silver reliefs and engraved panels <strong>of</strong> alarge reliquary in Oviedo Cathedral (the Arca Santa; see fig. 13),which is now attributed to the late eleventh or early twelfthcentury. <strong>The</strong> sources for the style, while speculative, wereprobably multiple. <strong>The</strong> underlying stimulus over time, besidesEarly Christian Roman and Carolingian art, was undoubtedlyByzantine, either directly through Byzantine objects that hadbeen brought to the Latin West, such as figured silks and ivoryicons, or indirectly through the prism <strong>of</strong> Western works thathad already assimilated iconographic and stylistic elementsfrom Byzantium.If we concentrate on the first substyle in the CardeinaBeatus, it is possible to consider English manuscript painting assuch an intermediate source. Examples dating from the secondquarter <strong>of</strong> the twelfth century were produced at the abbey <strong>of</strong>Bury Saint Edmunds, at Christ Church, Canterbury, and at thecathedral priory <strong>of</strong> Saint Swithun in Winchester. <strong>The</strong> CardeinaBeatus's Majesty illustration (see p. 22) provides an especiallystriking echo <strong>of</strong> the clinging drapery powerfully advanced inboth the Bible <strong>of</strong> about 1135 from Bury Saint Edmunds (seefig. 24 on p. 23) and the first volume <strong>of</strong> the Dover Bible, a work<strong>of</strong> the scriptorium at Christ Church in Canterbury dating toabout 1155 (Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, MS 3, fol. 168v).A variant <strong>of</strong> this style may be seen in the wall painting SaintPaul and the Viper <strong>of</strong> about 1163 in Saint Anselm's Chapel,Canterbury Cathedral (fig. 21 on p. 18). A possible avenue forthis potential English influence at Cardefia may have been theextensive pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela from abroad,not only from England but from elsewhere in Europe. <strong>The</strong>pilgrims' route across northern Spain included Burgos, andthe monastery <strong>of</strong> San Pedro de Cardefna was one <strong>of</strong> the parishes<strong>of</strong> Burgos, as established by Pope Alexander III's bull <strong>of</strong> 1163.11

FIGURE 14<strong>The</strong> Crucifixion, from a lectionary.French (Burgundy, abbey <strong>of</strong> Cluny),early 12th century. Tempera onparchment; folio 167/8 x 123/4 in. (43 x32.5 cm). Bibliotheque Nationale deFrance, Paris (MS nouv. acq. lat.2246, fol. 42v, detail)Accordingly, another variation on the damp-fold mannermay have been available through the influence <strong>of</strong> paintingfrom the abbey <strong>of</strong> Cluny in Burgundy. Examples <strong>of</strong> Cluniacpainting include the Ildefonsus manuscript <strong>of</strong> about 11oo(Biblioteca Palatina, Parma, MS 1650, fol. 102v); illustrated lectionaryand Bible fragments in Paris (fig. 14) and Cleveland(fig. 15); and the imposing frescoes at Berze-la-Ville. <strong>The</strong>sepaintings, like some <strong>of</strong> the cited Spanish works in other media,actually combine the damp-fold and pleated, descriptive substyles.<strong>The</strong> connection with Cluniac painting may have beenfacilitated by pilgrimages and by the previously mentionedBenedictine reforms and appointments <strong>of</strong> Cluniac abbots inthe north <strong>of</strong> Spain. Another factor, as suggested by JohnWilliams, may have been the close ties with Cluny that werebased in part on Spanish gold. Muslim tribute to the kingdom<strong>of</strong> Leon, ruled by Ferdinand I (the Great; r. 1037-65) and thenby Alfonso VI (r. lo065-1109), thus enabled substantial supportfor the construction <strong>of</strong> the immense third church at Cluny atthe end <strong>of</strong> the eleventh century.Turning the focus more exclusively now to the second, ordescriptive, manner, in which the draperies are almost always14 layered in pleats with zigzagged or stepped edges, we see thatthe figures in this group suggest the low-relief configurations<strong>of</strong> Middle Byzantine ivory icons (see fig. 16), a few <strong>of</strong> whichhad reached the Iberian Peninsula as early as the late eleventhcentury. This patrimony is confirmed by the use <strong>of</strong> suchByzantine conventions as the Virgin's veil, or maphorion, andher high seat or throne, with its footstool and cushion, in theCardefna Adoration <strong>of</strong> the Magi miniature (see p. 21). Yet it isnot certain whether this pleated style was conveyed directly orindirectly, through English or French sources. Some <strong>of</strong> thedraped figures in the historiated initials in the first volume <strong>of</strong>the above-mentioned Dover Bible come to mind. An evenmore convincing source could possibly have been Cluny, asseen in the Cleveland portrait <strong>of</strong> Saint Luke (fig. 15).Attention should be drawn, in closing, to the elegant acanthusbar terminals on the genealogy pages <strong>of</strong> the CardeinaBeatus (see pp. 19-21) and to the foliate capitals and bases thereand elsewhere. When arranged symmetrically, the acanthus15leaves <strong>of</strong>ten flank a bud or flower, which can easily be seen atvarious times in the actual acanthus plant at <strong>The</strong> CloistersFIGUREfo(see fig. 17). An English source for the Cardefna Beatus's useSaint Luke, from a Bible. French(Burgundy, abbey <strong>of</strong> Cluny), ca. 1100oo. <strong>of</strong> the acanthus may be suggested by the manuscripts citedTempera and ink, with gold and above, particularly the Bury and Dover Bibles, as well as by asilver, on parchment; 63/4 x 63/8 in. small, secular oak chest <strong>of</strong> about 1150, attributed to Canterbury(17.1 x 16.2 cm). <strong>The</strong> Cleveland<strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Art</strong>, Purchase from theand preserved in the Louis Carrand collection in the MuseoJ. H. Wade Fund (1968.190, detail) Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (fig. 18).- 12 -

1716As indicated in the foregoing and on many <strong>of</strong> the pagesopposite the colorplates that follow, there is nothing particularlyinnovative in the surviving illustrations <strong>of</strong> the CardeinaBeatus in terms <strong>of</strong> their iconography. Yet the style and thequality <strong>of</strong> execution are, for the most part, quite extraordinaryand creative, even in the utilization <strong>of</strong> borrowed elements."Mozarabic" tradition is still evident, but in a limited way, as inthe flat, broad color bands <strong>of</strong> certain backgrounds and in theoccasional use <strong>of</strong> horseshoe arches and other such details.<strong>The</strong>se features are totally subsumed within a new style, however-onein which the linear patterns and proportions, thetreatment <strong>of</strong> figures as both monumental and kinetic, andthe judicious use <strong>of</strong> color demonstrate an intrinsic authority,an unwavering aesthetic, and a mastery <strong>of</strong> pan-EuropeanRomanesque painting <strong>of</strong> the highest order.FIGURE 16Book Cover, with Icon <strong>of</strong> theCrucifixion. Panel: Byzantine-WILLIAM D. WIXOM(Constantinople), second half <strong>of</strong>loth century. Ivory, with traces <strong>of</strong>gilding; 53/8 x 35/8 in. (13.7 x 9.1 cm).Setting: Spanish (Arag6n, Jaca),before 1085. Gilded silver, withpseud<strong>of</strong>iligree, glass, crystal, andsapphire, over wood core; lol/2 x71/2 in. (26.7 x 19.1 cm). MMA, Gift <strong>of</strong>J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.134)18FIGURE 17Acanthus plant (Acanthus mollis)with flowering spikes, grown in thegardens <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong> CloistersFIGURE 18Casket (detail). English (Canterbury),ca. 1150. Oak; h. (overall)31/8 in. (8 cm). Museo Nazionale delBargello, Florence (Louis CarrandCollection)- 13 -

1991.232.1A

Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beatus<strong>of</strong> Liebana (Cardefia Beatus)Spanish (Leon-Castile, Burgos, probably monastery <strong>of</strong> SanPedro de Cardefna), ca. 1175-80. Tempera, gold, silver, andink on parchment; each folio approx. 175/8 x 117/8 in. (44.8 x30.2 cm); bifolium (1991.232.2) 173/8 x 231/4 in. (44.1 x <strong>59</strong>.1 cm).MMA, Purchase, <strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, Rogers and HarrisBrisbane Dick Funds, and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1991(1991.232.1-.14)As in the earlier Beatusmanuscripts, a series <strong>of</strong>prefatory leaves preceded thebiblical texts and commentariesin the Cardefna Beatus.<strong>The</strong> page at left shows twobays <strong>of</strong> an arcade withgolden horseshoe archessupported on tall, narrowcolumns with lush foliatecapitals and bases. A secondarcade <strong>of</strong> four blue archesappears to stand behindthe first, although all fivecolumns rest on a commonground line.Drawn, painted, and partiallygilded on the recto <strong>of</strong>a folio without any text orcaption, the elegant architecturalscheme might be seenas purposeless. <strong>The</strong> artistmay have intended it, however,to <strong>of</strong>fset the parchmentsheet's fully painted verso(see p. 16), which over timehas become a ghost imageon the recto.An ancestor <strong>of</strong> theCardefnarcade may beobserved in the Beatus manuscripthoused in the PierpontMorgan Library, NewYork (see fig. 19). That earlierexample, in which the arcadeframes and embellishes thegenealogy tables <strong>of</strong> Christ,has, by contrast to the Cardefnaversion, no hint <strong>of</strong>depth or space. Both designsrecall actual architecturalexamples found in thenorthern regions <strong>of</strong> Spain.<strong>The</strong> monastic church <strong>of</strong> SanMiguel de Escalada, builtin 913 just east <strong>of</strong> Leon, isnotable for the high horseshoearches <strong>of</strong> both its naveand the tall screen separatingthe choir from the nave(see fig. 20).FIGURE 19Commentary on the Apocalypse byBeatus <strong>of</strong> Liebana and Commentaryon Daniel by Jerome (MorganBeatus). Spanish (Asturias-Le6n,Le6n), mid-loth century. Temperaand ink on parchment; each folioapprox. 15/4 x 111/4 in. (38.7 x 28.5 cm).<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 5r)NOTE:All Apocalypse quotations arefrom an English translation <strong>of</strong> theLatin Vulgate Bible (the Douay-Rheims version) as revised byBishop Richard Challoner in 1749-52. <strong>The</strong> selections correspondoselyto those chosen by Beatus <strong>of</strong> Liebanato precede the commentaries.FIGURE 20Interior, San Miguel de Escalada.Spanish (Asturias-Le6n), 91315 -

I:1tS,:*^H -i;1991.232.1B

Without any inscription orcaption, this frontispieceimage nevertheless recallsseveral passages in the Apocalypsetext: for example,"I am Alpha and Omega,the beginning and the end,saith the Lord God, who is,and who was, and who isto come, the Almighty"(Apoc. 1.8).<strong>The</strong> lamb is a mysticalimage <strong>of</strong> Christ used frequentlyin the Apocalypsetext, as in 7.17 ("For theLamb, which is in the midst<strong>of</strong> the throne, shall rulethem, and shall lead them tothe fountain <strong>of</strong> the waters <strong>of</strong>life") and 22.14 ("Blessed arethey that wash their robesin the blood <strong>of</strong> the Lamb").Poles for the spear andsponge used to tormentChrist during the Passionrise out <strong>of</strong> the lamb's back,along with the tapered stand<strong>of</strong> a gold processional cross.<strong>The</strong> Greek letters suspendedfrom the cross's crossbar,alpha and omega, are toggleboltedin place. <strong>The</strong> threenails <strong>of</strong> the Crucifixion areheld by one <strong>of</strong> the angels.One might at firstsuppose that the elegantcross, which dominates thefrontispiece, could refer toone <strong>of</strong> the two highlyrevered wood-and-goldcrosses in the treasury <strong>of</strong>Oviedo Cathedral. Thosetwo crosses may be consideredemblems <strong>of</strong> theAsturian rulers in northernLeon: Alfonso II (r. 791-842)and Alfonso III (r. 866-91o).<strong>The</strong> earlier and smaller <strong>of</strong>the crosses, dated 846 (8o8by the modern calendar), isrepresented frequently onthe frontispiece pages <strong>of</strong>"Mozarabic" Beatus manuscripts.Yet that cross, withits flared arms <strong>of</strong> equallength, as in a Greek cross,is obviously not the onerepresented here. Nor is theCardefna cross a likeness<strong>of</strong> Oviedo's second andlarger cross, with its slenderwooden core encrusted withintricate gold decorationand gems and its upper armsconfigured with trefoilextensions. <strong>The</strong> encasement<strong>of</strong> that piece, known asthe Cross <strong>of</strong> Victory, datesto shortly before its presentationto Oviedo Cathedralin 908.John Williams has written<strong>of</strong> the interconnectionsbetween the Carolingianmonastery <strong>of</strong> Saint Martin atTours, in France, and earlySpanish illuminated manuscripts,with a particularfocus on Leonese initialdecoration and such specificiconographics as the lambdepicted with instruments<strong>of</strong> the Passion, namelythe spear and sponge. Hepostulates that a TouronianBible <strong>of</strong> the ninth centurywas present in the northernportion <strong>of</strong> the Spanishpeninsula as early as thesecond quarter <strong>of</strong> the tenthcentury. A review <strong>of</strong> thecorpus <strong>of</strong> extant Touronianmanuscripts reveals severalparallels in the depiction <strong>of</strong>the cross, the suspendedalpha and omega, and thelamb with the spear, sponge,and flanking angels. <strong>The</strong>re-fore, the Cardefna cross maybe designated as a Carolin-gian or Touronian type andnot a "Mozarabic" one.This change is a partialconfirmation <strong>of</strong> the pan-European orientation <strong>of</strong>the figure style discussed onpages 9 to 12.<strong>The</strong> prefatory portion <strong>of</strong>the Cardefna Beatus contin-ued with leaves identifyingeach <strong>of</strong> the four Gospelswith paired figures groupedbeneath column-supportedhorseshoe arches. <strong>The</strong> leavesfor Matthew and Mark, pre-served in Madrid, are fragmentary;those for Luke andJohn are missing entirely.<strong>The</strong> exuberantly foliatedcapitals and bases on thesurviving fragments arecousins to those supportingthe arcade on the recto <strong>of</strong>the Cardefia frontispiece(see p. 14).- 17 -

<strong>The</strong> next installment <strong>of</strong>prefatory leaves consisted <strong>of</strong>an extensive series <strong>of</strong> tablestracing the ancestry <strong>of</strong>Christ back to the beginning<strong>of</strong> the world. (<strong>The</strong>Apocalypse text itself, <strong>of</strong>course, follows this historythrough to the end <strong>of</strong> theworld.) <strong>The</strong> bifolium in the<strong>Metropolitan</strong> <strong>Museum</strong> givesan indication <strong>of</strong> the appearance<strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> the Cardeinagenealogical diagrams, withtheir linear connectionsbetween inscribed medallionsand architecturalelements. <strong>The</strong> particularschema <strong>of</strong> the Incarnationthat is reproduced, in part,on the opposite page culminatesin an illustration <strong>of</strong>the Magi adoring the Christchild, who is held beforethem by the enthronedVirgin (see p. 21); an angelstands at the left.Byzantine elements havealready been observed withrespect to the Virgin's veiland footstool, her high,cushioned throne, and theother figures' pleateddraperies with zigzaggededges-all <strong>of</strong> which may berelated to the importation<strong>of</strong> Byzantine ivory iconsinto the Iberian Peninsula(see p. 12 and fig. 16). Aspecifically Anglo-Byzantinepatrimony may underlie thekneeling king, whose forwardmovement and clingingdraperies recall (inreverse) those <strong>of</strong> the greatfigure <strong>of</strong> Saint Paul in SaintAnselm's Chapel, CanterburyCathedral (fig. 21).FIGURE 21Saint Paul and the Viper (detail<strong>of</strong> fresco). English (Saint Anselm'sChapel, Canterbury Cathedral),ca. 1163-18-

if.M4...

*qz,*nfiwiftwifg,4 C I11ASL1991.232.2B

ge,ifttsW.~Ai.fugauem. m>mimaw1nLSW ssu?au> (waT^iSu" wam fP;L-Imwoisn ~&wpa~zsaT^?^X^^1?k;.)1991.232.2C

4.:,;, If,.I.-,.!'iI "X.1'4;c0nmmb^uf4gtm.to ipurmKf eu?t,tmumdor ucbo &Sid torqmc adtuuftlmm do4n utmur quulcu^uflouun wttuettui.4Udtwsaconfunau^e -#nfeumltn axbWr.$;clnfo,.fe$ubonm C Sd;w^oe oc^ctifs Co^tipu ti.imtipre r + em - tm?naimuonw fXaw tuctnum dtdim4.tnKwmrd jlpaEqA umdi t tr tno a fm npa uoiu^,mttx uuir quoiu ,qutipti u1hguuquobIe1o nonqu fium u .u&.rtaniunitifus T wnfmdtn uu aomibi b1 -mtue 115tt?ic*usti)it#u*ui'ittttmcAuzr.um~m panmna

APOC. 1.1-6he Revelation <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ,which God gave unto him, tomake known to his servants thethings which must shortly cometo pass: and signified, sending by his angel tohis servant John,2 Who hath given testimony to the word <strong>of</strong>God, and the testimony <strong>of</strong> Jesus Christ, whatthings soever he hath seen.3 Blessed is he, that readeth and heareth thewords <strong>of</strong> this prophecy; and keepeth thosethings which are written in it; for the time isat hand.4 John to seven churches which are in Asia.Grace be unto you and peace from him thatis, and that was, and that is to come, andfrom the seven spirits which are before histhrone,5 And from Jesus Christ, who is the faithfulwitness, the first begotten <strong>of</strong> the dead, andthe prince <strong>of</strong> the kings <strong>of</strong> the earth, who hathloved us, and washed us from our sins in hisown blood,6 And hath made us a kingdom, and priests toGod and his Father, to him be glory andempire for ever and ever. Amen.FIGURE 22Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 23r, detail)FIGURE 23God the Father, from a Bible.Spanish (Le6n-Castile, Burgos,monastery <strong>of</strong> San Pedro deCardena), ca. 1175. Tempera onparchment; folio 201/2 x 145/8 in.(52 x 37 cm). Biblioteca Provincialde Burgos (MS 846, fol. 12v, detail)<strong>The</strong> placement <strong>of</strong> theenthroned Christ, flankedby two angels, in the upperregister and <strong>of</strong> an angeladdressing John and anunidentified companion inthe lower register is carriedover from earlier Beatusillustrations (see fig. 22). <strong>The</strong>architectural framing, suggestive<strong>of</strong> a church interior,is new. <strong>The</strong> three closedbooks depicted in the Cardefnaminiature probablyrepresent the New Testament(held by Christ) and John'sApocalypse text (held by one<strong>of</strong> the large angels and bythe small figure below). <strong>The</strong>Byzantine "damp-fold"drapery style, with ovalor teardrop accentuations<strong>of</strong> the thighs, knees, andforearms, is closest to examplesin English manuscripts(see p. 11 and fig. 24).This feature, as well as theFIGURE 24Master Hugo (English, activeca. 1125-52). Ezekiel's Vision <strong>of</strong> God,from the Bury Bible, vol. 3. Abbey<strong>of</strong> Bury Saint Edmunds, ca. 1135.Tempera on parchment; folio 201/4 x14 in. (51.4 x 35.5 cm). CorpusChristi College, Cambridge (MS 2,fol. 281v, detail)pronounced entasis <strong>of</strong> theengaged columns, is sharedwith another manuscriptfrom Cardefia, a Bible <strong>of</strong>about 1175 (see fig. 23). <strong>The</strong>narrow, columnar character<strong>of</strong> the Cardefna angels recallsthe elongated column statuesin Oviedo Cathedral (seefig. 11). <strong>The</strong> zoomorphicfaldstool supporting Christ,with its animal-head terminalsand claw feet, is aWestern type that alsoappears in one <strong>of</strong> the earlytwelfth-centurynielloimages on the back <strong>of</strong> thereliquary diptych <strong>of</strong> BishopGundisalvo Menendez inthe Camara Santa, OviedoCathedral. Christ's puffedupcushion, however, isByzantine in origin, as isthat beneath the Virgin inthe Adoration <strong>of</strong> the Magiminiature (see p. 21).- 23 -

.: f 01991.232.4A

APOC. 3.1-6A t nd to the angel <strong>of</strong> the church <strong>of</strong>Sardis, write: <strong>The</strong>se things saithhe, that hath the seven spirits <strong>of</strong>God, and the seven stars: I knowthy works, that thou hast the name <strong>of</strong> beingalive: and thou art dead.2 Be watchful and strengthen the things thatremain, which are ready to die. For I find notthy works full before my God.3 Have in mind therefore in what manner thouhast received and heard: and observe, and dopenance. If then thou shalt not watch, I willcome to thee as a thief, and thou shalt notknow at what hour I will come to thee.4 But thou hast a few names in Sardis, whichhave not defiled their garments: and theyshall walk with me in white, because they areworthy.5 He that shall overcome, shall thus be clothedin white garments, and I will not blot outhis name out <strong>of</strong> the book <strong>of</strong> life, and I willconfess his name before my Father, andbefore his angels.6 He that hath an ear, let him hear what theSpirit saith to the churches.FIGURE 25Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 66r, detail)FIGURE 26Master Mateo (Spanish[Le6n-Castile, Galicia], active 1168-88).Figures <strong>of</strong> Apostles, Right Jamb,Central Portal, P6rtico de la Gloria,Cathedral <strong>of</strong> Santiago de Compostela.Le6n-Castile (Santiago deCompostela), 1168-88<strong>The</strong>re are few iconographicdifferences between the Cardefiaillustration and theearlier version <strong>of</strong> the samesubject in the Morgan Beatus(fig. 25). Chiefly, elements <strong>of</strong>the composition have beenreversed; hot colors havebeen abandoned in favor <strong>of</strong> amore subdued palette; andthe figural and architecturalstyles have gained in sophisticationand complexity.Certain details have beenaltered as well. An altar isnow visible inside the church,and John presents his letterin the form <strong>of</strong> a clearly openbook to the angel, who gesturesin response. <strong>The</strong> framingis narrower and subjectto breach by both figures'toes and one <strong>of</strong> the angel'swings; the church towersalso disrupt the picture'srectangularity. Finally,gold has been added to thehalos and to portions <strong>of</strong>the architecture.<strong>The</strong> rendering <strong>of</strong> draperyon the Cardefia page exhibitsa combination <strong>of</strong> the dampfoldand pleated substyles,which again recalls contemporaryarchitectural sculpturein northern Spain,especially, in this case, thehigh-relief column sculpturesat Santiago de Compostela(see fig. 26). <strong>The</strong> church inthe Cardefia illumination,with its interlocking roundarches, foliate capitals, andcolonnaded towers, is representative<strong>of</strong> a pan-EuropeanRomanesque architecture.-25-

I_I.IIII__. .ji..~~~:; -soI** s- B*w s fo'*.; ;k. ;j. .*. E'* *..""..:. .'*:^:^o~,;Ni^-'/'^anptr,.p14uno fua'dick e,.0 b^.ptcdicwtrfc etu -asquiJ.A 4b y a n . U t44 1/D. imo d.,udtr ,tcudtr w uemotius pull4nn^ib4r| .if)onwtbdflimulmmh^=tttwiimw.^u|inmbuse a4di

APOC. 3.7-13A t nd to the angel <strong>of</strong> the church<strong>of</strong> Philadelphia, write: <strong>The</strong>sethings saith the Holy One andthe true one, he that hath thekey <strong>of</strong> David; he that openeth, and no manshutteth; shutteth, and no man openeth:8 I know thy works. Behold, I have given beforethee a door opened, which no man can shut:because thou hast a little strength, and hastkept my word, and hast not denied my name.9 Behold, I will bring <strong>of</strong> the synagogue <strong>of</strong>Satan, who say they are Jews, and are not, butdo lie. Behold, I will make them to come andadore before thy feet. And they shall knowthat I have loved thee.o10 Because thou hast kept the word <strong>of</strong> mypatience, I will also keep thee from thehour <strong>of</strong> temptation, which shall come uponthe whole world to try them that dwell uponthe earth.1 Behold, I come quickly: hold fast that whichthou hast, that no man take thy crown.12 He that shall overcome, I will make him apillar in the temple <strong>of</strong> my God; and he shallgo out no more; and I will write upon himthe name <strong>of</strong> my God, and the name <strong>of</strong> thecity <strong>of</strong> my God, the new Jerusalem, whichcometh down out <strong>of</strong> heaven from my God,and my new name.13 He that hath an ear, let him hear what theSpirit saith to the churches.Here, John <strong>of</strong>fers his visionarytext, in the form <strong>of</strong> aclosed book, to anotherllimiii 11111111111 - - I --angel (this one representingPhiladelphia, the sixth <strong>of</strong> thechurches <strong>of</strong> Asia Minor),whose gestures suggest bothinstruction and wonder.Except for the details <strong>of</strong> thisaction and the presence <strong>of</strong>an altar and eucharisti chalice-which,as on the previ-ous Cardefna leaf, hint at theinterior architectural space<strong>of</strong> an apse-the iconographyremains unchanged fromthat <strong>of</strong> the correspondingillustration in the MorganFIGURE 27Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 70ov, detail)FIGURE 28Apostle Figure, West Facade, Church<strong>of</strong> Santiago. Spanish (Le6n-Castile,Palencia, Carri6n de los Condes),1170-80Beatus (fig. 27). Yet the hotcolors, including an intenseyellow, <strong>of</strong> the earlier manuscripthave again given wayto a less strident and simplercolor scheme, notwithstandingthe addition <strong>of</strong> gold. <strong>The</strong>two figures now suggest lowrelief. <strong>The</strong> damp-fold style<strong>of</strong> drapery in the figure <strong>of</strong>John, which is especiallyclose to that <strong>of</strong> the largerangels on the Majesty page(see p. 22), may be comparedto an analogous apostlefigure in Carri6n de losCondes (see fig. 28).-27-

V9'zfz1'66i4,I'?.-..--:,. J _X --i\,. .44^

APOC. 6.9-11A t nd when he had opened thefifth seal, I saw under the altarthe souls <strong>of</strong> them that wereslain for the word <strong>of</strong> God, andfor the testimony which they held.10 And they cried with a loud voice, saying:How long, 0 Lord (holy and true) dost thounot judge and revenge our blood on themthat dwell on the earth?11 And white robes were given to every one <strong>of</strong>them one; and it was said to them, that theyshould rest for a little time, till their fellowservants, and their brethren, who are to beslain, even as they, should be filled up.Iconographically, this subjectis anticipated in several <strong>of</strong>the earlier Beatus manuscripts,including the onein the Morgan Library (seefig. 29). <strong>The</strong> three registerscontaining broad bands <strong>of</strong>color, the altar and suspendedvotive <strong>of</strong>ferings, the souls<strong>of</strong> the dead as doves, thefocal figure <strong>of</strong> the blessingChrist, and the clusteredmartyrs are common to themall. <strong>The</strong> two trees with elegant,curling branches thatflank Christ in the Cardeinaillustration appear to beunique (and displace theaforementioned doves fromthe middle to the upperregister).<strong>The</strong> draperies in the lowertwo registers, exponents <strong>of</strong>the damp-fold substyledescribed on page 9, are ulti-mately Anglo-Byzantinein nature. <strong>The</strong> martyrs overlapone another enough tocreate a sense <strong>of</strong> space, howevershallow, and this effect isin tension with the ellipses <strong>of</strong>blue and red over white thatmarch in rhythmic sequenceacross the lower register <strong>of</strong>the illustration. <strong>The</strong> smoothovoid shapes, especially onthe thighs, recall those at thesides and on the shoulders <strong>of</strong>the contemporary sculpturesfrom Cerezo de Riotironthat are now in the CloistersCollection (see fig. 30).FIGURE 29Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. lo9r, detail)FIGURE 30Enthroned Virgin and Child, froman Epiphany relief. Spanish (Le6n-Castile, Burgos, Cerezo de Riotir6n),third quarter <strong>of</strong> 12th century. Limestone;h. 541/8 in. (137.2 cm). MMA,<strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, 1930 (30.77.8)-29

...1..:::fff0 Xu :0

APOC. 7.1-3A t fter these things, I saw fourangels standing on the fourcorners <strong>of</strong> the earth, holdingthe four winds <strong>of</strong> the earth,that they should not blow upon the earth,nor upon the sea, nor on any tree.2 And I saw another angel ascending fromthe rising <strong>of</strong> the sun, having the sign <strong>of</strong> theliving God; and he cried with a loud voice tothe four angels, to whom it was given to hurtthe earth and the sea,3 Saying: Hurt not the earth, nor the sea, northe trees, till we sign the servants <strong>of</strong> our Godin their foreheads.<strong>The</strong> iconography persistsfrom the earlier Beatus (seefig. 31). A dramatic blue surroundstill represents the sea(yet without the fish), andthe central area with a treerepresents the earth. <strong>The</strong>Cardefia image lacks theinscriptions MARE and[T]ERRA, which were realizedin the Morgan Beatus withwidely spaced letters, to beread counterclockwise andclockwise, respectively; alsomissing is the sun's inscription,SOL. <strong>The</strong> compositionhas been simplified as well;there are fewer figures, andthe artist has adopted thedamp-fold manner to delineatethem. This manner, alsovisible in the Cardefna Bible(see fig. 23), is diluted andcombined with the pleatedsubstyle in other late Beatusmanuscripts, such as theexample in Manchester (seefig. 32), where it results in arandomly cursive effect. <strong>The</strong>trumpets in these laterBeatus manuscripts, oursand Manchester's, take theform <strong>of</strong> southern Italiantenth- to eleventh-centuryivory blast horns, known asoliphants (see fig. 33).FIGURE 32Angels Restraining the Winds, fromCommentary on the Apocalypse byBeatus and Commentary on Danielby Jerome (Manchester Beatus).Spanish (Leon-Castile, Burgos?),late 12th century. Tempera onparchment; folio 177/8 x 127/8 in.(46 x 32.6 cm). John RylandsUniversity Library <strong>of</strong> Manchester(Lat. MS 8, fol. liv, detail)FIGURE 31Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 115v, detail)FIGURE 33Blast Horn (Oliphant). SouthernItalian (Sarazen), loth-nth century.Ivory; 1. 21 in. (53.4 cm). <strong>Museum</strong> <strong>of</strong>Fine <strong>Art</strong>s, Boston, Frederick BrownFund and H. E. Bolles Fund(50.3425)31

v8'zz't66i

APOC. 8.6-7A t nd the seven angels, who hadthe seven trumpets, preparedthemselves to sound thetrumpet.7 And the first angel sounded the trumpet, andthere followed hail and fire, mingled withblood, and it was cast on the earth, and thethird part <strong>of</strong> the earth was burnt up, and thethird part <strong>of</strong> the trees was burnt up, and allgreen grass was burnt up.<strong>The</strong> cataclysm described inthe Apocalypse is interpretedliterally in both the earlyMorgan Beatus (see fig. 34)and the Cardefna example atleft. While in each the angelis oriented to be read fromthe side, the pictorial meansdiffer greatly. <strong>The</strong> clarity andorder <strong>of</strong> the Cardefna angel,as well as the overall regularizedcomposition, make thisillustration perhaps the lessfrightening <strong>of</strong> the two. <strong>The</strong>narrowing trail <strong>of</strong> wordsquotes the end <strong>of</strong> the seventhverse <strong>of</strong> the Latin text:"... et omne fenum virideco[m]bustum e[st]."<strong>The</strong> trumpeting angelis a fine example <strong>of</strong> thepleated, or descriptive, manneralso exhibited in the firsttwo illustrations with figuresin the <strong>Metropolitan</strong>'s portion<strong>of</strong> the Cardefna Beatus (seepp. 16, 21). <strong>The</strong> remainingleaves continue in this substyle,which is discussed onpages 1o and 12.FIGURE 34Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 134v, detail)-33-

wa{qnarmsn uib tcItrecbenamir4tegimtittm 4i4awhmn...rnodism.rf.ut. ,-XC, mu-I,, ?< ,uiu, i' p jt/iW. ,to .. i.fupma( h tmiwTnieoT u'' &TO n .3'Iti nl au qiv rf0t

APOC. 8.12-13A t nd the fourth angel soundedthe trumpet, and the third part<strong>of</strong> the sun was smitten, and thethird part <strong>of</strong> the moon, and thethird part <strong>of</strong> the stars, so that the third part<strong>of</strong> them was darkened, and the day did notshine for a third part <strong>of</strong> it, and the night inlike manner.13 And I beheld, and heard the voice <strong>of</strong> oneeagle flying through the midst <strong>of</strong> heaven,saying with a loud voice: Woe, woe, woe tothe inhabitants <strong>of</strong> the earth: by reason <strong>of</strong> therest <strong>of</strong> the voices <strong>of</strong> the three angels, who areyet to sound the trumpet.FIGURE 35Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 138v, detail)Iconographically, this illustrationagain coincides withearlier examples (see fig. 35).<strong>The</strong> deleted third <strong>of</strong> thesun and third <strong>of</strong> the moon,following "Mozarabic" precedent,are treated as removalsfrom a pie dish.<strong>The</strong> Cardefna illustrationhas a remarkable clarity andpotential largeness <strong>of</strong> scale,as if it had been made inpreparation for a mural. <strong>The</strong>rich color and vigorous linearpatterns in the drapery, wings,and hair give the angel a specialmagnificence and monu-mentality. <strong>The</strong> sure handling<strong>of</strong> the pen establishes this elegantfigure as a tour de force<strong>of</strong> draftsmanship. <strong>The</strong> eagle,equally eloquent, could almostbe a design for metalwork.Although not historicallyrelated, a slighter but no lessfierce falcon sculpture at<strong>The</strong> Cloisters (fig. 36) comesto mind. Each raptor haspowerful talons, a tightlyimbricated body, an incisivehooked beak, and an intensity<strong>of</strong> gaze.<strong>The</strong> broad bands <strong>of</strong> backgroundcolor, traditional inearlier Beatus illustrations,provide a dramatic, stagelikesetting for the protagonistsand for the heavenly bodies.<strong>The</strong> three animistic treeswith Anglo-Byzantine acanthusleaves and blossoms(see p. 12) in the lower registerbehave most alarmingly,yet with the subtlety <strong>of</strong>Venus's-flytraps.<strong>The</strong> text enclosed in atrapezoid in the right margingives a clear instruction:"Reader, think deeply aboutwhat you have read."FIGURE 36Falcon. Southern Italian, ca. 1200.Copper alloy (bronze?), with traces<strong>of</strong> gilding; h. 10o3/4 in. (27.3 cm).MMA, <strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, 1947(47.101.6o)-35-

A...v..rI'

APOC. 9.1-6A t nd the fifth angel sounded thetrumpet, and I saw a star fallfrom heaven upon the earth,and there was given to him thekey <strong>of</strong> the bottomless pit.2 And he opened the bottomless pit: and thesmoke <strong>of</strong> the pit arose, as the smoke <strong>of</strong> agreat furnace; and the sun and the air weredarkened with the smoke <strong>of</strong> the pit.3 And from the smoke <strong>of</strong> the pit there cameout locusts upon the earth. And power wasgiven to them, as the scorpions <strong>of</strong> the earthhave power:4 And it was commanded them that theyshould not hurt the grass <strong>of</strong> the earth, norany green thing, nor any tree: but onlythe men who have not the sign <strong>of</strong> God ontheir foreheads.5 And it was given unto them that they shouldnot kill them; but that they should tormentthem five months: and their torment wasas the torment <strong>of</strong> a scorpion when hestriketh a man.6 And in those days men shall seek death, andshall not find it: and they shall desire to die,and death shall fly from them.FIGURE 37Valve <strong>of</strong> a Mirror Case. English,1180-1200. Copper alloy, withgilding; diam. 4/8 in. (11.1 cm). MMA,<strong>The</strong> Cloisters Collection, 1947(47.101.47)FIGURE 38Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 14ov, detail)<strong>The</strong> parallels with theMorgan Beatus (see fig. 38)are dear. <strong>The</strong> random orien-tation <strong>of</strong> the figures, almostentirely without regard togravity, intensifies the otherworldlyawesomeness <strong>of</strong> thesubject in each miniature.<strong>The</strong> Cardefna angel, to be readfrom the side, exemplifies thepleated substyle. He stepsforward gently, almost hesitantly,with wings outspreadand blows on his upturned,oliphant-like horn (see fig. 33).<strong>The</strong> other figures-theundead recognizable by theirheavy-lidded or closed eyesassumevarious attitudes <strong>of</strong>pleading or collapse. <strong>The</strong>locusts, menacingly stripedin black and white in theCardefia illustration, stingtheir victims with long, segmented,scorpion-like tails.<strong>The</strong>ir heads are seen onlyfrom above in the Morganminiature, whereas in thelater work they are also seenin pr<strong>of</strong>ile. With their froglikebodies, animated articulation,and nodular spines andtails, the Cardefia locustsseem to resemble no knowncreature. Loosely comparableexamples in art, however,may be the dragon-lizards incontemporary Romanesquemetalwork (see fig. 37). Andclosely related in the manuscriptitself are the pr<strong>of</strong>iledragon's heads <strong>of</strong> Christ'sfaldstool on the Majesty page(see p. 22).37-

43:- -i ert .I I 4.:-, a ' .. -* 1rIL...I;:7.tKSI T,jni:la^.lMwqwotttl/tn-' I' _:,J?.^?di

APOC. 9.13-16A t nd the sixth angel sounded thetrumpet: and I heard a voicefrom the four horns <strong>of</strong> thegolden altar, which is before theeyes <strong>of</strong> God,14 Saying to the sixth angel, who had thetrumpet: Loose the four angels, who arebound in the great river Euphrates.15 And the four angels were loosed, who wereprepared for an hour, and a day, anda month, and a year: for to kill the third part<strong>of</strong> men.16 And the number <strong>of</strong> the army <strong>of</strong> horsemenwas twenty thousand times ten thousand.And I heard the number <strong>of</strong> them.All <strong>of</strong> the iconographic elements,even the fish in theEuphrates, mirror those inthe earlier Morgan Beatus(see fig. 39). One <strong>of</strong> the fishin our illustration-the onewith the upturned snoutappearsto represent a sturgeon.<strong>The</strong> celestial arc in theupper left corner <strong>of</strong> eachminiature frames a figure<strong>of</strong> the enthroned Christ. <strong>The</strong>Cardefia Christ, however,sits on an animal-headedfaldstool and a deep pillowsimilar to those beneathChrist on the Majesty page(see p. 22). <strong>The</strong> significance<strong>of</strong> the shift from Christ'sopen book in the olderBeatus to a closed andtightly clasped volume inthe <strong>Museum</strong>'s miniature isopen to conjecture.<strong>The</strong> Cardefna figureshave a particular subtlety <strong>of</strong>movement. While, as in theMorgan Library illustration,they make exclamatory gestures,they also seem to betaking small steps or shiftinglightly on their feet, theirmulticolored and pleateddraperies gathered aboutthem. <strong>The</strong>re is a suggestion <strong>of</strong>modeling and corporeality.<strong>The</strong> Christ figure, <strong>of</strong>fering ablessing, combines features<strong>of</strong> both the damp-fold andpleated manners (see pp. 9-lo). This portrayal, whileactually very small, is large inconcept-imposing andmonumental. One <strong>of</strong> theclosest stylistic parallels insculpture is the trumeaufigure by Master Mateo inthe cathedral <strong>of</strong> Santiago deCompostela (fig. 40).FIGURE 39Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 144r, detail)FIGURE 40Master Mateo (Spanish[Le6n-Castile, Galicia], active 1168-88).Figure <strong>of</strong> the Apostle James theGreater, Trumeau <strong>of</strong> Central Portal,P6rtico de la Gloria, Cathedral <strong>of</strong>Santiago de Compostela. Le6n-Castile(Santiago de Compostela), 1168-88-39-

SGcItinztt^qnt Fony3mucnnw 4einw gtum ..bi mad

APOC. 11.15A nd the seventh angel soundedthe trumpet: and there weregreat voices in heaven, saying:<strong>The</strong> kingdom <strong>of</strong> this world isbecome our Lord's and his Christ's, and heshall reign for ever and ever. Amen.<strong>The</strong> Morgan Beatus (seefig. 41) contains a similarinterpretation <strong>of</strong> John'sverse, the end <strong>of</strong> which isfamiliar from the HallelujahChorus <strong>of</strong> Handel's Messiah.<strong>The</strong> angels in both minia-tures, instead <strong>of</strong> holdingtheir books, literally standon them. <strong>The</strong> Cardefna illustration,while emulating thewide color bands <strong>of</strong> theearlier tradition for itsbackground, takes a newdirection with its variationon a Romanesque stylerooted in Byzantium-wellknown to us by now as thepleated substyle or descriptivemanner. What is remarkablein several <strong>of</strong> theCardefna Beatus miniaturesis the sense <strong>of</strong> figural movement,sometimes tentative,sometimes arrested, but herein full swing with the twisting,gesticulating angelcompletely enveloped inintricate and oscillatingdrapery. This regard for therhythmic torsion <strong>of</strong> a figurehas an ancestry in some <strong>of</strong>the ivory reliefs carved inLeon during the first quarter<strong>of</strong> the twelfth century (seefig. 42).FIGURE 42Noli me tangere (John 20.17:"Touch me not"), detail <strong>of</strong> reliquaryplaque. Spanish (Le6n-Castile,Le6n), ca. 1115-20. Ivory; overall10/8 x 51/4 in. (27 x 13.2 cm). MMA,Gift <strong>of</strong> J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917(17.190.47)FIGURE 41Miniature from the Morgan Beatus.<strong>The</strong> Pierpont Morgan Library, NewYork (MS M. 644, fol. 156r, detail)-41-

:1991.232.13B