Queensland Brain Institute 2010 Annual Report - University of ...

Queensland Brain Institute 2010 Annual Report - University of ...

Queensland Brain Institute 2010 Annual Report - University of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

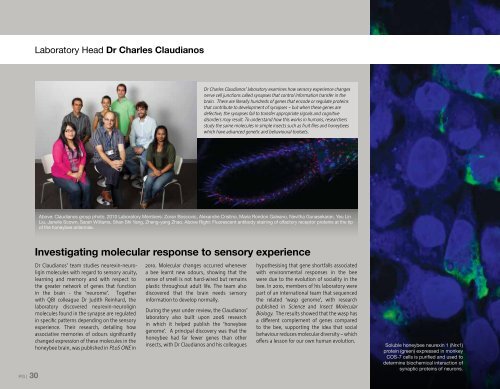

Laboratory Head Dr Charles ClaudianosDr Charles Claudianos’ laboratory examines how sensory experience changesnerve cell junctions called synapses that control information transfer in thebrain. There are literally hundreds <strong>of</strong> genes that encode or regulate proteinsthat contribute to development <strong>of</strong> synapses – but when these genes aredefective, the synapses fail to transfer appropriate signals and cognitivedisorders may result. To understand how this works in humans, researchersstudy the same molecules in simple insects such as fruit flies and honeybeeswhich have advanced genetic and behavioural toolsets.Above: Claudianos group photo. <strong>2010</strong> Laboratory Members: Zoran Boscovic, Alexandre Cristino, Maria Rondon Galeano, Nevitha Gunasekaran, Yeu LinLiu, Janelle Scown, Sarah Williams, Shan Shi Yang, Zheng-yang Zhao. Above Right: Fluorescent antibody staining <strong>of</strong> olfactory receptor proteins at the tip<strong>of</strong> the honeybee antennae.PG | 30Investigating molecular response to sensory experienceDr Claudianos’ team studies neurexin-neuroliginmolecules with regard to sensory acuity,learning and memory and with respect tothe greater network <strong>of</strong> genes that functionin the brain - the ‘neurome’. Togetherwith QBI colleague Dr Judith Reinhard, thelaboratory discovered neurexin-neuroliginmolecules found in the synapse are regulatedin specific patterns depending on the sensoryexperience. Their research, detailing howassociative memories <strong>of</strong> odours significantlychanged expression <strong>of</strong> these molecules in thehoneybee brain, was published in PLoS ONE in<strong>2010</strong>. Molecular changes occurred whenevera bee learnt new odours, showing that thesense <strong>of</strong> smell is not hard-wired but remainsplastic throughout adult life. The team alsodiscovered that the brain needs sensoryinformation to develop normally.During the year under review, the Claudianos’laboratory also built upon 2006 researchin which it helped publish the ‘honeybeegenome’. A principal discovery was that thehoneybee had far fewer genes than otherinsects, with Dr Claudianos and his colleagueshypothesising that gene shortfalls associatedwith environmental responses in the beewere due to the evolution <strong>of</strong> sociality in thebee. In <strong>2010</strong>, members <strong>of</strong> his laboratory werepart <strong>of</strong> an international team that sequencedthe related ‘wasp genome’, with researchpublished in Science and Insect MolecularBiology. The results showed that the wasp hasa different complement <strong>of</strong> genes comparedto the bee, supporting the idea that socialbehaviour reduces molecular diversity – which<strong>of</strong>fers a lesson for our own human evolution.Soluble honeybee neurexin 1 (Nrx1)protein (green) expressed in monkeyCOS-7 cells is purified and used todetermine biochemical interaction <strong>of</strong>synaptic proteins <strong>of</strong> neurons.