A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour - International Labour ...

A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour - International Labour ...

A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour - International Labour ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

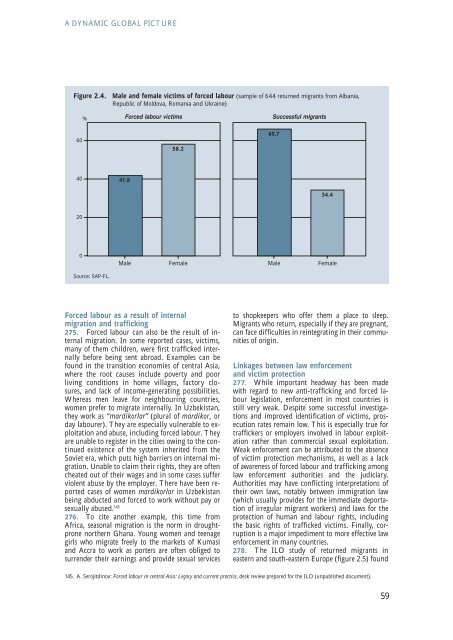

A DYNAMIC GLOBAL PICTUREFigure 2.4.Male and female victims of forced labour (sample of 644 returned migrants from Albania,Republic of Moldova, Romania and Ukraine)%<strong>Forced</strong> labour victimsSuccessful migrants6058.265.74041.834.4200Male Female Male FemaleSource: SAP-FL.<strong>Forced</strong> labour as a result of internalmigration and trafficking275. <strong>Forced</strong> labour can also be the result of internalmigration. In some reported cases, victims,many of them children, were fi rst trafficked internallybefore being sent abroad. Examples can befound in the transition economies of central Asia,where the root causes include poverty and poorliving conditions in home villages, factory closures,and lack of income-generating possibilities.Whereas men leave for neighbouring countries,women prefer to migrate internally. In Uzbekistan,they work as “mardikorlar” (plural of mardikor, orday labourer). They are especially vulnerable to exploitationand abuse, including forced labour. Theyare unable to register in the cities owing to the continuedexistence of the system inherited from theSoviet era, which puts high barriers on internal migration.Unable to claim their rights, they are oftencheated out of their wages and in some cases sufferviolent abuse by the employer. There have been reportedcases of women mardikorlar in Uzbekistanbeing abducted and forced to work without pay orsexually abused. 145276. To cite another example, this time fromAfrica, seasonal migration is the norm in droughtpronenorthern Ghana. Young women and teenagegirls who migrate freely to the markets of Kumasiand Accra to work as porters are often obliged tosurrender their earnings and provide sexual servicesto shopkeepers who offer them a place to sleep.Migrants who return, especially if they are pregnant,can face difficulties in reintegrating in their communitiesof origin.Linkages between law enforcementand victim protection277. While important headway has been madewith regard to new anti-trafficking and forced labourlegislation, enforcement in most countries isstill very weak. Despite some successful investigationsand improved identification of victims, prosecutionrates remain low. This is especially true fortraffickers or employers involved in labour exploitationrather than commercial sexual exploitation.Weak enforcement can be attributed to the absenceof victim protection mechanisms, as well as a lackof awareness of forced labour and trafficking amonglaw enforcement authorities and the judiciary.Authorities may have confl icting interpretations oftheir own laws, notably between immigration law(which usually provides for the immediate deportationof irregular migrant workers) and laws for theprotection of human and labour rights, includingthe basic rights of trafficked victims. Finally, corruptionis a major impediment to more effective lawenforcement in many countries.278. The ILO study of returned migrants ineastern and south-eastern Europe (figure 2.5) found145. A. Serojitdinov: <strong>Forced</strong> labour in central Asia: Legacy and current practice, desk review prepared for the ILO (unpublished document).59