LIVING SPACE: TOMORROW'S CITY - Atkins

LIVING SPACE: TOMORROW'S CITY - Atkins

LIVING SPACE: TOMORROW'S CITY - Atkins

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

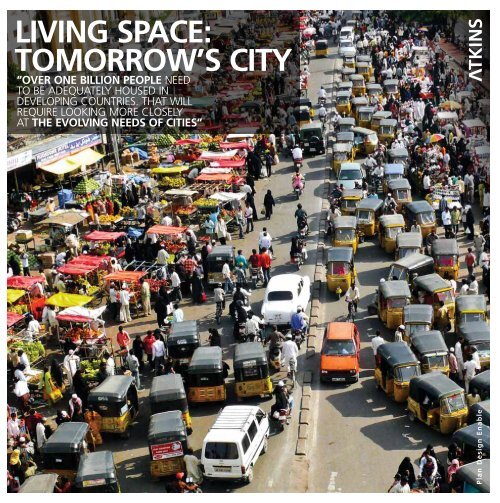

changingcitiesby Richard Alvey,managing directorEnvironmentalplanning, atkinsThe city of tomorrow needs to be plannedwith the bigger picture in mind – and that pictureis now bigger than ever. Governments andplanners must walk a very fine line, balancingthe need for sustainable urban growth as aneconomic driver with the needs of the peoplewho live and work there.Half of the world’s population already lives in citiesand, by 2030, that number is expected to hit 60 percent or higher. What’s more, according to the “Stateof the World’s Cities 2010/2011” report published byUN Habitat: “Between the year 2000 and 2010, over200 million people in the developing world will havebeen lifted out of slum conditions.” India, China andAfrica are all witnessing the rise of a new middle class,aspiring to the kind of lifestyle to which people in theWest have been so long accustomed. This is one ofthe largest population migrations the world has everknown and we’re all watching it happen.In these economies, the emphasis is on highleveltransport and infrastructure planning, to meetthe changing needs of their people. Lifestyles arebecoming increasingly energy-hungry and homeownership is on the rise. For example, in Oman,<strong>Atkins</strong> has recently planned a new city district forSuhar in order to meet the needs of a growingpopulace while also attracting investment anddriving economic growth.The more mature markets of Europe and NorthAmerica, meanwhile, are coping with the increasedexpectations of a well-established population, asthey strive to retain that population and maintaineconomic stability. This means paying greaterattention to issues surrounding public realm – frommore shared public spaces to improved pedestrianand cycling options.What does this mean for the cities in which welive? It means we’re facing some intriguing challengesand some truly remarkable opportunities.Business, transport, infrastructure, climatechange and a host of other practical issues needto be addressed in our march to urbanisation. Addto this the various socio-political and economicpressures we face today and city planning becomesmore complicated than ever.The people paradigmPlanning a city is more than just designing buildingsand creating suitable infrastructure. It’s more thanwater, power and roads. It’s about the ebb and flowof the people who will live and work and travelwithin that space, and anticipating the way inwhich all of these pieces will both intersect andinteract. If the needs of the population are notunderstood, the original spirit of a plan can be lost.It’s an essential distinction: masterplanning canplay a key role in the long-term agenda of a city orregion. Take the recent redesign of the crossingsystem at London’s Oxford Circus, by <strong>Atkins</strong>. On theone hand, the iconic crossroads was notorious forheavy traffic and pedestrian congestion, a frustratingbottleneck of shoppers and tourists. Any plan toupdate the site had to solve these fundamentalissues in order to function.3“Business, transport, infrastructure,climate change and a host of otherpractical issues need to be addressedin our march to urbanisation”

<strong>Atkins</strong>’ new city district forBaku includes a mall, offices,residential areas and acentral business district.

Growthin the GulfPlanners in the Arabian Gulf face quite a task.To ensure long-term and sustainable growth,they must imagine a future that involvesdiversifying economies and rising populations.Could a holistic approach hold the key?

<strong>Atkins</strong>’ projects often involve engaging with local communities in the field – for example, our strategic planning work across the Middle East.8industry and tourism. Bahrain is an island state andthe northern part of the island – which includesthe capital, Manama – is densely populated.“It’s a matter of finding ways to extend thaturban structure to meet future developmentneeds,” says Roger Savage, associate directorwith <strong>Atkins</strong>. “The population is going to increasefrom 1.1 million to perhaps 2.1 million over thenext 20 years, so it’s a large amount of growthto accommodate in quite a small space.”Bahrain’s National Planning and DevelopmentStrategy was launched in 2005 to address thechanging landscape. It began by setting out thespatial plan for the country and now the focus ison turning that plan into a reality.“The work being done now is on implementationto take the strategy forward. This covers planningtools, drafting an updated planning law, and alsopreparing a suite of regulations and guidance togo with that – things like planning and designguidelines, and addressing how developmentshould be delivered in certain areas,” says Savage.Implementation includes a new strategictransport model, making it possible to assess thetraffic effects of new developments. It alsoconsiders how infrastructure and land aremanaged, and – crucially – how it’s all to befunded, including developer contributionsfor infrastructure. “This goes beyond straightplanning,” says Savage. “The public sector isinvolved in planning and subdividing some areas,but you’ve also got privately led schemes, whichare almost self-contained gated communities thatfall completely outside of the current remit.“It requires a balance between private andpublic sector involvement, making sure that openspace and public access to the waterfront aredelivered and that there are adequate communityfacilities to serve these developments.”Risk managementEuropean nations have a tradition of statesponsoredplanning. The same is not true in theGulf, where governments have generally taken aless prominent role in directing development ofprivate land. But that’s changing. There’s growingawareness of the benefits of strategic planningand its ability to bolster economic resilience.“understanding where demandsare likely to be made allowsgovernment to be more efficientin making its own investments”“There’s a realisation that the more speculativeapproach to development may not be the bestway to deliver large-scale projects,” says Savage.“Schemes that have been successful – and areongoing – involved a long-term approach tomanaging land and development, and phasingthe infrastructure.”Crucially, planning can play a decisive role inattracting new investment – and that’s of criticalimportance as countries such as Bahrain continueto diversify away from oil: “Institutional investorssee having a robustly formulated plan as a way ofmanaging risk,” says Savage. “If you have aproper strategic plan, it can flex to accommodatechanges in the market.”Strategic plans also help reduce financial riskfor governments. “If you pay for majorinfrastructure development from the start andthen everything changes, you can’t be sure it willbe able to accommodate what comes next. That’scostly. Understanding where demands are likely tobe made allows government to be more efficientin making its own investments,” says Savage.“Integrated development supportsdiversification and delivers tangible economicbenefits,” observes Savage. “But it also providessome of the more intangible ones, including abetter quality of life.”It is hoped that tackling the complex economicand social challenges facing nations in the Gulfusing a sustainable and holistic approach, as in theUAE, will pave the way to an even brighter future.

85per cent of the UAE populationare expats. Migrant workers –both skilled and unskilled – arethe linchpin of the economy.Barking Giamet, quat praessisis nosto od tio consectet wisi.Iriure velessequat lutpat ad euiscin hendionullum dunt augait

The Shizhimen New CBDMasterplan in Zhuhai, China,is intended to act as anadditional economic enginefor the Pearl River Delta.“A recent World Bank study estimatesthat, as of 2007, SEZs still accountedfor about 22 per cent of nationalGDP, about 46 per cent of FDI andabout 60 per cent of exports – andgenerated in excess of 30 million jobs”

economiczonesstimulatingdevelopmentUrban economics:in the zoneYou can’t force economic prosperity and relevance ona locality, or turn a once-underdeveloped area into athriving commercial hub over night. But careful planningand design could act as a catalyst for change.In October 2010, the Associated Chamber of Commerceand Industry of India (Assocham) submitted a paper on thegrowth strategy for Uttar Pradesh to the state’s chiefminister. It predicted that, by using so-called specialeconomic zones (SEZs) to support sectors with exportpotential, it could increase gross state domestic product(GSDP) by 64 per cent by 2020.It’s a bold claim but one that is backed up by the shortyet successful history of the use of SEZs to stimulateeconomic development. Pioneered in India in the 1960s andthen further developed in China under Deng’s government inthe 1980s, SEZs saw huge tracts of undeveloped landearmarked and ring-fenced for industrial use. Infrastructurewas built, thousands of rural dwellers moved in to providelabour and special incentives were created to attract as muchinward investment as possible.Shenzen in China was the first globally recognised majoreconomic zone. Some measure of its success comes from thefact that it went from a fishing village on the Guangdongcoast to an industrial city of nine million people in less than30 years, purely on the back of planned investment inchemical and electronic production. It now boasts eightprovinces, an industrial and software park, and even has itsown stock exchange.According to Robert Zoellick, president of the WorldBank, SEZs played a key role in China’s move from a pooragrarian economy to one of the world’s largestmanufacturing centres. “Special economic zones werea test-bed for economic reforms, for attracting foreigndirect investment, for catalysing development of industrialclusters, and for attracting new technologies and adoptingnew management practices,” he said in September 2010.“Even though their importance has diminished over time,a recent World Bank study estimates that, as of 2007, SEZsstill accounted for about 22 per cent of national GDP, about46 per cent of FDI and about 60 per cent of exports – andgenerated in excess of 30 million jobs.”Celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, President HuJintao hailed the success of Shenzhen as a “miracle in theworld’s history of industrialisation, urbanisation andmodernisation,” adding that it had “contributed significantlyto China’s opening up and reform”. The president urgedfuture SEZs to be bold in reform and innovation in their rolesas the “first movers”.He was right to encourage new thinking. Times havechanged and the centrally planned zones dedicated toindustry have evolved to a new type of economic zoning.“It used to be mono-functional and focused on one typeof industry,” says Roger Savage, associate director with<strong>Atkins</strong>. “The Chinese experiment essentially involved puttingtogether a package of incentives to encourage inwardinvestment and letting it develop along a single track.”But the lessons learned in some early Chinese zones –with inflexible infrastructure, minimal social amenities andpollution issues – have prompted planners to adjust.“Planners have realised that they need to develop servicesand communities to support these zones, and that meansthey need to be more integrated in the range of amenitiesand activities they offer residents, with more attention paidto the quality of the environment,” says Savage.11

“These new zones are based less on heavyindustry and more on services and hi-techsectors. They are better planned”12Future flexibilityThe watchword now is diversification. Whereas the earlySEZs were built around a single industrial process – chemicalproduction or heavy industry, for example – now, plannersare trying to find ways of building on a diverse set offunctions in order to allow adaptability for future use.“These new zones are based less on heavy industry andmore on services and hi-tech sectors,” says Savage. “They arebetter planned and often managed by a single organisationthat coordinates the infrastructure and the amenities.”Planners working on zoning development now focus onincorporating broader sectors of the economy and attractingmore highly skilled workers to populate the zones. Thetheory is, the wider the economic base within the SEZ, thegreater the chances of long-term prosperity. Added to that,just bussing in migrant workers with no thought to the widersocial consequences both within and outside the zone simplywon’t be tolerated by local communities.“It’s about creating a community that people actuallywant to live in,” says Savage. “The lifestyle aspect hasbecome much more important with the rise of serviceindustries. If you look at the business process outsourcing(BPO) sector in India, these are high-tech sectors andoccupations and you can’t just lay out a standard industrialestate and expect skilled people to go and live there. So themodern SEZs are more like a refresh of the old companytowns you used to have in the US with amenities and socialprovision at their heart.”But while the mining towns and the company suburbspioneered by US industrialists like Levitt ultimately fell victimto stagnation, today’s planned economic zones are far moreintegrated and focused on long-term benefits both forworkers, companies and the host country.In common with many cutting-edge economic and urbandevelopment projects, the UAE is leading the way on this.John Barber, an economist by training now consulting with<strong>Atkins</strong>, has seen the theory and practice develop through hiswork over 17 years. Having relocated to China in thesummer of 2011, Barber’s previous work in the Middle Eastfocused on the Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi project,supported by the emirate.The project involves 420 square kilometres of land and<strong>Atkins</strong> has been looking at a range of developmentopportunities in terms of heavy industry, as well asdownstream industry in chemicals, the metal sector andthe construction material sectors.“There is a lot of hydrocarbon money involved in this,”says Barber. “It is perceived as pump-priming from the publicsector to kick-start the private sector.”Khalifa is seen by many as an exemplary project of its type,in that it combines a mix of industrial, commercial, social andresidential developments. It has been planned as a more organicproject designed to adapt to changes in the macroeconomicconditions and not as a rigid, mono-functional factory-state.Similarly, the Musaffah Industrial Area serving Abu DhabiCity is being upgraded in its role as the prime location for lightindustrial and business uses in the UAE. <strong>Atkins</strong> was brought inby Abu Dhabi Municipality to prepare masterplan proposalscovering everything from land use to circulation patterns, andurban design and landscape strategies for public spaces.Some NEW THINKINGPanama Pacifico:designed to attract foreign andThis is a clear example of the new regional investment to the area.thinking currently surrounding Tax incentives, labour benefitseconomic zones. Given theand planning breaks were alsocountry’s history – the Panama introduced. Situated next to oneCanal took over 40 years to build of the world’s most importantand virtually turned the entire trade routes, the zone is lookingcountry into a special economic to leverage its naturalzone – it was only fitting that it advantages to attract commercial,should adopt a similar approach industrial and freight companies.for the 21st century.The masterplan has beenThe area, on the outskirts of praised for its sustainabilityPanama City and near thecredentials, including an awardeastern mouth of the canal, is by former US President BillClinton as part of his ClintonClimate Initiative (CCI). The CCIrecognises projects around theworld that address the dualchallenge of climate change andurbanisation. Clinton’sfoundation created the ClimatePositive Development Programto meet these challenges byencouraging and supportingsustainability in large-scaleurban development.The CCI selected PanamaPacifico as one of just 17 initialprojects across the globe, saying:“A key highlight of PanamaPacifico is the ecologicalsustainability plan... Efforts inrestoring and protecting nearly1,400ha of wetlands and othernative habitats, as well asintegrating natural processeswith their innovative stormwater management plan, will actas a tool for sequestering largeamounts of carbon.”The CCI goes on to highlightPanama Pacifico’s masterplan,citing concepts from theinternational standards ofSmart Growth, New Urbanismand sustainable land use.“The new design includes ahealthy jobs-housing balance,ensuring future success andgrowth in the community andmaking Panama Pacifico thefirst of its kind in Latin America,”according to the CCI.With its diverse mix of businessand residential elements it is atruly modern planning project.

Khalifa IndustrialZone Abu Dhabi isseen as an exemplarySEZ project andincludes provision fora range of sectors.Open for businessWhile SEZs are being made more diverse in order to attract abroader range of potential investors and workers, ultimatelytheir purpose is to drive investment and attract capital.However, the way in which this is achieved has also changed.“The business environment is probably one of the mostimportant aspects,” says Barber. Because there has been somuch development in the free zones around the Middle East,and the world as a whole, it is becoming more and moredifficult to differentiate between them.”Clearly, the earlier approach, which gave rise to a kindof walled city where everything inside the gates workedtowards the zone’s economic success with no regard toanything outside, can no longer be sustained. Barber’swork in the Middle East in particular has demonstratedthe value of greater integration.“Those planning zones now have to look much moreclosely at ensuring the benefits are accruing for the localeconomy, and the zone does not become a sort of exporthaven where the economy isn’t going to be touched by theactivities in the free zones,” says Barber.This is important because SEZs have been criticised in thepast for being too exclusive. One of the longest runningconcerns about SEZs has been the lack of benefits accruedby the indigenous population. The use of migrant labour hasalso been highlighted as a notable downside to planneddevelopment. However, over the last few years, especially inthe Middle East, that issue has been addressed in several ways.By coupling cutting-edge design and planningtechniques with strong central direction and a skilled andincreasingly mobile workforce – not simply importing cheaplabour but attracting the right talent as needed – manyemerging economies are now viewing SEZ development asa shortcut to imposing economic prosperity on previouslyunder-developed areas. Thankfully, these zones are nowplaying a greater part in spreading prosperity across sectorsand economies.In Savage’s view, we’ve come a long way: “They usedto be one-dimensional and weren’t very lively or interesting.Now it’s about incorporating broader sectors of theeconomy and attracting a wider range of businesses andworkers. Alongside that, in the emerging economies, theplanning and implementation phases tend to overlap a lot22per cent of national GDP in Chinacomes from SEZs. They have playeda key role in China’s move from apoor agrarian economy to one of theworld’s largest manufacturing centres.more now: you do the first phase and see how that goes,and then factor in economic changes, and see whichaspects become successful and adapt accordingly.“The timescales have also decreased,” Savagecontinues. “In Europe you might be looking at five orten years between phases, but in some of these emergingmarkets it can be more like two years in and they’re alreadythinking about the next phase. They can only do thatbecause of the speed of economic growth and theadvances in design.”13Barking Giamet, quat praessisis nosto od tio consectet wisi.Iriure velessequat lutpat ad euiscin hendionullum dunt augaitPanama Pacifico:an updated approachto SEZs in one of theworld’s original plannedeconomic zones.

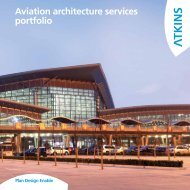

moderncitiesplanning forurbanisationThe new faceof the old cityBy 2050, the largest city in the world will probably bein China – and it hasn’t been built yet. Demographics arealtering the shape of the modern landscape from Shanghaito Mumbai. Masterplanners are defining that newenvironment. From central business districts to mega cityregions, rising incomes worldwide are changing the gameand planners are looking ahead to the city of tomorrow.The city is undergoing a renaissance. People who onceaspired to live in the widening suburban sprawl on the edgeof metropolitan areas now want to be at the heart of citylife. In Europe and North America, widespread gentrificationand the regeneration of industrial districts such as canalsand dockyards is replacing some of the blight and decayof the 1970s and 1980s, resulting in new cityscapes thatare a pleasure to live and work in.Outside the West, exciting new city developments areappearing everywhere from Baku and Nairobi to Abu Dhabiand Seoul, either in the form of huge extensions to existingcities or completely new cities built from scratch. Oftenworking with fewer constraints, city planners arefundamentally re-imagining what the city is all about.Driving this surge in planning is a wide range of factors –including new national wealth, dramatic population shifts fromrural to urban areas, the need to respond to demographic14500new cities havebeen added toChina’s landscapesince 1978. Chinais leading the waywhen it comes tobig developmentsand mass migrationfrom rural to urbanareas. By 2040, theurban population isforecast to expandby 400 million, orabout 15 millionpeople per year.

changes, and ambitious efforts to create sustainable placeswith better access to technology, financial centres or culture.Emerging economies are providing most of the biggestdevelopments, because their needs are often most urgentand they are generally more willing to think big and do awaywith the old. By contrast, in the West, the tendency is topreserve, renew and infill cities – partly because of a lack ofspace, but also because public opinion tends to be lessprepared to embrace new construction.In the developing world, there is a desire for growthand modernity – though this comes at a price, according toDr George Martine, co-author of a 2010 study on urbanisationpublished by the International Institute for Environment andDevelopment and the UN Population Fund (UNFPA).“Massive urban growth in developing countries loom assome of the most critical determinants of economic, socialand ecological wellbeing in the 21st century,” he says.East Asian tigersAs in so many things, China is leading the way when it comesto big developments. Since 1978, it has added roughly 500new cities to the landscape and it already has 160 cities ofmore than a million people (by comparison, Europe has 35).Over the next 20 years, the percentage of Chinese expected tolive in cities will grow from roughly 50 per cent today to 70per cent. By 2040, the urban population is forecast to expandby 400 million – about 15 million people per year.“What’s happening in China is the rapid urbanisationthat we have already seen in Japan and the tigereconomies,” says Mark Harrison, senior technical directorfor <strong>Atkins</strong>’ urban planning consultancy in Beijing. “It’s thesame as what happened in Britain and Europe followingthe Industrial Revolution, and in America in the last century.We’re seeing a rapid urbanisation, and a mass migrationof people to urban areas.”The tremendous growth in China and elsewhere in EastAsia is leading to a new phenomenon: mega city regions,where cities coalesce to form uninterrupted urban stretches.Examples include: the Hong Kong-Shenzhen-Guangzhouregion in China, which is home to 120 million peopleaccording to a recent UN report; the Nagoya-Osaka-Kyoto-Kobe corridor in Japan – 60 million people; and the Malaysia-Singapore area.“These regions are economically sound, but they dopose many challenges. For example, how do you reflectlocal or regional identity in these very large areas, if onlyfrom an aesthetic point of view?”Harrison says.Another big challenge in China is planning for a societythat is evolving so rapidly. “China is changing from asocialist to a market-socialist system, so that changes theway the cities are. If they weren’t exporting to the West,for example, there wouldn’t need to be these massive590million peoplewill be livingin cities in Indiaby 2030, up from340 million in 2008.Thirty per cent ofthe populationalready lives inurban centres.Over 90 millionhouseholds willqualify as middleclass by then, upfrom 22 milliontoday. Urbanisationin India is going tobe paramount.

“new cities that are being developed in China, India and the restof Asia are going to be able to draw on the latest thinking,where we design cities that are sustainable at every level”export processing zones or ports, or for central businessdistricts, retailers, leisure, and so on,” says Harrison.Changing timesIn another 20 years, India will have caught up with China interms of population. Whereas China’s one-child-per-familyrule is resulting in an ageing workforce, India’s burgeoningpopulation is projected to be growing at around 0.6 per cent ayear. Thriving urban areas will be key, as the country will haveto handle the challenge of accommodating a populationgrowing at a faster rate than China’s within a smaller landarea. New McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) projections showIndia’s urban population soaring to 590 million in 2030.The country will also become a nation of upwardlymobile middle-class households. By 2025, the Indian middleclasses will have expanded dramatically to 583 million people– some 41 per cent of the population. In fact, cities are beingbuilt for the emerging middle classes in many areas of theworld. In Azerbaijan, for example, a 200-hectare urbancentre is being developed on the outskirts of Baku, aiming toreclaim lands that were once polluted with oil pits, rail yardsand other industrial facilities.Other new purpose-built cities include Mussafah on theedge of Abu Dhabi. Mussafah is designed as a designatedindustrial area and is one of several projects designed toreduce the region’s dependency on oil and build the necessaryfoundations and infrastructure to support a sustainable societyin the future. According to Abu Dhabi’s Urban PlanningCouncil, some $200bn will have been pumped into variousinfrastructure projects in the Emirate by 2013.Cities have always been built according to proximity ofbasic resources like water, but it’s now possible to build in allkinds of places, even in previously inhospitable environmentssuch as deserts. In a potential precursor to a futuristic worldaltered by climate change, it is perhaps comforting to knowthat purpose-built virtual cities can be situated anywhere.“Whereas in the past cities were located in places foralmost prehistoric reasons, that doesn’t need to be thecase any more,” explains Matt Tribe, director at <strong>Atkins</strong>.“In dealing with climate change, sea-level rises, and othernatural processes, planners may now go through a processof taking people away from risk areas, by understandingthe best place to locate them.”Planning perfect citiesThe advantage of new cities is that sustainability can be builtinto every aspect of the design.“The new cities that are being developed in China, Indiaand the rest of Asia are going to be able to draw on the latestthinking, where we design cities that are sustainable at everylevel. That means how we design individual buildings, andhow we find the optimal mix of land uses so we can reducethe need to travel. This is much harder to put in place onceyou’ve already built your city,” Harrison says. He asserts thatsustainability is an increasingly important part of developmentshe is involved with in China – most recently, a financial districtin Chengdu and a new business district in Beijing.5million peopleare expectedto live in AbuDhabi by 2030.The Emirate ismaking a strategicleap towards a newenvironment thatwill achievesustainable urbanplanning andeconomic growth.

“We try to focus on the key areas of sustainability, likecarbon, water, energy and waste. The important thing is tolook at those things early because it’s then that a lot of themcan be designed out. You can bring population andemployment into balance, minimising the trips people makeand encouraging as many people as possible to use publictransport. Depending on the location, we also want to reactto climate conditions for heating and cooling,” he adds.Harrison says China is likely to be a good learning groundfor masterplanners in the future: “I’m sure a lot of thecomplex urban questions that we’re now facing around theworld will have some answers in China, just simply becauseof the numbers of people involved, the scale of thedevelopment and the relatively free hand.”With sustainability in mind, it is likely that cities willbecome increasingly dense. “Future cities are probablygoing to have public transport taking a more dominant role,perhaps even personal rapid systems, if it’s feasible. But to dothat you are going to need high densities of people, ratherthan people spread out across a city. You need tohave high concentrations around stations to make themeconomically viable,” says Harrison.“I think there will be more transport-orientateddevelopments which will be very dense, but there willalso be clustering as well,” suggests Tribe. “Rather thanmegatropolises like the Chinese are developing, I thinkthere will also be compact densities that are highly linked.That means either physically with super-fast trains or ITwith fast broadband.”The move to denser urban environments is already evidentin Europe and North America, particularly where sprawl is aconcern. After the Second World War, the tendency was tobuild outwards, creating new suburbs and commuter towns.In recent years, however, that sort of construction has becomeincreasingly unacceptable, according to Harrison.“Politically, it’s quite difficult to plan any kind of newgrowth in the UK at the moment. This is due in part to therecession of course, but also because the countryside andheritage is very much valued. So, it’s all about infillingparticular city sites, and a sustainability agenda of havingdenser cities that use land more effectively.“And then there’s the realisation what wonderfularchitectural assets are to be found in the older hearts ofcities, often in buildings that had a previous use,” saysMichael Hebbert, Professor of Town Planning in the Schoolof Environment & Development at the University ofManchester. “Urban renaissance is partly buildingrenaissance – rediscovering old buildings.”The Guangzhou East Towerin China uses the culturalassociation with bamboo todefine its form. It consists of afive-star hotel above servicedapartments and offices.As well as investing heavily in cities like Liverpool,Bristol, Leeds and Cardiff, the previous UK governmentannounced plans for up to 10 eco-towns around England.It was hoped that these settlements would address thepressing need for affordable housing while being sustainableand carbon neutral.Plans included smart meters for residents to track theirenergy usage, plug-in points for electric cars and large spacesfor parks and playgrounds. However critics doubted theeco-towns’ ability to attract the necessary infrastructure,such as transport and schools, and to meet the ambitiousenvironmental standards. The plans have since beendowngraded considerably to four eco-towns. These are nowslated for 2016 and still need to make it through the planningapproval process.“The UK has a fairly robust policy to sustainability,but because we are building in much smaller volumes,it is more difficult to affect some of the fundamentals ofland‐use planning,” says Paul Fraser, a senior urbandesigner at <strong>Atkins</strong>.By comparison, Fraser was part of the team working onMussafah in Abu Dhabi, which is of a sufficient size tosupport a full range of public services.“Ideally, you have a hierarchy of public services. Withina typical five-minute walk, you would expect to find a localshop, post box and so on. A bus network would allow you toget to a health clinic and a bigger set of shops. And thenregional facilities like hospitals would be accessible with atleast one mode of transport.“It is essential that you create an effective network thatallows you to access as many of these things as possiblewithout using your car,” Fraser explains.“There is tremendous latent demand for urban buzz,”says Hebbert. “You can see it in the take-up rates ofresidential opportunities close to city centres. It is about arediscovery of everything that an urban, as opposed to asuburban, lifestyle can offer. So the value of proximity isgoing to increase and, with that, encouragement for a highquality,high-density urban residential offer. I believe that’sgoing to be the trend of the coming century.”17

Living withclimate change

climatechangeplanning forglobal warmingFrom extreme weather systems to coastalfloods, research over the past decade paints adisturbing picture of what rising globaltemperatures could mean for the world’s cities.How can planners today anticipate a changingclimate’s influence and prepare for tomorrow?While the precise effects of climatechange are still impossible to predict, it isbecoming clear that strategic planning couldhold the key to reducing its social andeconomic impact. Intelligent approaches toplanning can’t come soon enough, as manyof the world’s cities lie on the coast or influvial zones, making them especiallyvulnerable to any changes in water level.As highlighted in the UN’s “State of theWorld’s Cities Report 2008/09”, 3,351 of theworld’s cities are situated in low-lying coastalzones – 64 per cent of which are in the highlypopulated developing world. Meanwhile,35 of the 40 largest cities in the developedworld (including Japan) are situated on thecoast or along a riverbank. The report predictsthat most coastal cities will feel the effects ofclimate change.The issue is one not only of geography,but also of demographics. In its most recent“World Disasters Report”, the InternationalFederation of Red Cross highlights what itcalls the “urban risk divide” – the disparitybetween well-planned wealthy cities andpoorer ones.“Physical infrastructure, land planningand the size of informal settlements are thebiggest factors determining the impact ofdisasters on cities,” says N M S IArambepola, director of urban disaster riskmanagement with the Asian DisasterPreparedness Centre in Bangkok. “With somany people migrating to the cities, many ofthe most vulnerable urban populations settlein the more disaster-prone areas where noone else wants to live.”Planning for the unknownIf the experts are right, climate change willmean coming to terms with a world whereextraordinary weather events such as tropicalcyclones may become far more frequent.Speaking at an Environment Agencyconference in November 2010, chairmanLord Chris Smith said: “We mustn’tunderestimate the enormity of theenvironmental challenges that lie ahead of usin the next 20 years. The science of climatechange remains compelling and during thisperiod we will begin to see its impact: moreextreme weather patterns; a moreunpredictable climate; changing agriculturalconditions; and a sea-level rise. There will bemore floods and more droughts.”Finding ways to cope is vital for rich andpoor nations alike. In January 2011 theBrisbane River burst its banks, causing theworst flooding in the city since 1974.The bill for cleaning up after thedevastation has been estimated at $440million, largely to construct new homes,repair transport infrastructure and restorepower to homes and businesses.19

cent rise in the UK’s peakriver flows over the next two decades20percould have significant implications.20The idea of taking long-termenvironmental changes into account inplanning policy has been slow to take root.But that’s starting to change, and one placewhere this is happening is in Bahrain. Thekingdom – an archipelago of more than 30islands in the Gulf – has a population ofmore than 790,000. Accommodating climatechange is a pillar of its National Planning andDevelopment Strategies, which are beingformulated by <strong>Atkins</strong>.Roger Savage, senior planning consultantwith <strong>Atkins</strong>, says that parts of Bahrain arequite low-lying, so a temperature rise of twodegrees in global mean temperatures wouldhave significant consequences. The questionis: how do you encourage development andprotect communities?One way is to ensure that newdevelopments meet rigorous resiliencestandards. Durrat al Bahrain, a massive newisland reclamation project at the southern tipof Bahrain, is an example. Reclamation levelsfor the 20km 2 development, which is beingled by <strong>Atkins</strong>, were set with sea-levelchanges in mind.“Bahrain has expanded quite dramaticallysince the mid-1960s, when the firstreclamation projects took place,” saysSavage. “The practice of reclaiming land,which can provide an opportunity to build inflood protection, is one way of dealing withthe problem of rising sea levels.”The Gulf benefits from the fact that it isrelatively sheltered and the violent stormsassociated with exposed coastlines are rare.But global sea-level rises would have animpact despite this.“There has been flooding of some of themore vulnerable coastal villages over thepast two years,” says Savage. “Part of thestrategic plan covers the marineenvironment. This integrates coastal zonemanagement and looks at the evolution ofthe coastline and how that may need to beadapted to respond to those challenges.”Masterplanning of this sort is aboutsetting long-term objectives and achievingthose objectives through incrementalchanges. These include mechanisms to steernew developments to areas where they arelikely to be sustainable and encouragingenergy-efficient urban design to protectcitizens from rising temperatures.“Traditional Islamic cities were built withshaded streets and narrow alleys. Buildingswere constructed in such a way that theycooled naturally,” notes Savage. “It’spossible to use some of these principles inmodern developments. They can beenshrined into development and designguidelines at the neighbourhood scale.”Locking-in sustainable growth means bigpicturethinking and attention to detail. Andthe effects, he emphasises, are cumulative.“It’s about channelling projects as they comeforward. Some of those will be quite largeand will clearly make large steps towardsdelivering the strategy. Some of the thingsIt is estimated thatit will take billionsof dollars and severalyears to repair thedamage of theBrisbane 2011 floods.will be much more incremental. The key isthat it needs the plan to set the direction.”On the riseClimate change is a major concern for coastalcommunities the world over. Some of thosecommunities have long and painful experienceof adapting to environmental change that has– all too often – come out of the blue.Communities along the Lincolnshire coastin east England are a case in point. Recordsstretching back 800 years paint a picture ofthe awesome power of the sea. It’s a roll callof flood defences breached, towns washedaway and land lost beneath the waves.The Lincolnshire coast is susceptible toflooding for two reasons. The first is the riskfrom storm surges: mass movements ofseawater funnelled down through the NorthSea. The second is isostatic readjustment:since the end of the last ice age, southernBritain has been slowly sinking, so relativesea levels continue to rise.The Lincolnshire coastal study, conductedby <strong>Atkins</strong> and completed earlier this year, isthe first comprehensive undertaking of itskind. The study considers the complex web ofrelationships between a huge range ofenvironmental, social and economic factors.These include rising sea levels, coastalflooding, economic regeneration, housing,agriculture, tourism, transport and health.“Planning for a period of 20 years isnothing when you compare it to naturalphenomena such as rising sea levels,” stressesSavage. “We need to look at a much longerperiod of time: 50 or 100 years.”The study considers how the roles ofcoastal towns could change over the comingdecades – roles that could be shapedsignificantly by strategic planning andspending decisions. It raises some toughquestions. “Do you freeze development asit is now and put in protection measures tostop flooding? Do you start graduallymoving people out of some of the smaller

“The practice of reclaimingland can provide anopportunity to build inflood protection”Land reclamation hasbeen a big part ofBahrain’s growth aswell as its efforts tocope with the impactof climate change.areas and provide new villages? Do youallow for growth but sacrifice some of thebest agricultural land in the country? Youmust develop methodologies to answerthese questions,” says Savage.The big pictureFigures published by the UK EnvironmentAgency suggest that global temperaturerises could have significant implications forthe UK, with peak rainfall intensity rising by10 per cent and peak river flows up 20 percent in the next two decades.In February 2010 Lord Smith spoke of theEnvironment Agency’s long-term investmentstrategy, published in 2009, whichhighlights the scale of investment requiredto protect England from flooding. “Ourmodelling suggests that we need anincrease in investment in building, improvingand maintaining defences – from currentlevels up to more than £1bn a year by 2035– to ensure that present levels of protectionare sustained and improved in the face ofclimate change,” he said.The predicted effects of climate changeare, however, aggregate figures, intended topaint a general picture of the sort ofchanges that could occur. So what couldchanges like this mean at the level of anindividual city? And can anything be done?The city of Bath lies on the River Avon inthe west of England. There’s nothing uniqueabout Bath’s riverside location: most majorsettlements are sited close to rivers oroceans. But local topography exacerbatesflood risk. Bath – a world heritage site – istucked into a relatively deep valley at thesouthern end of the Cotswold hills. Heavyrainfall in the city’s hilly catchment area canturn the Avon into a torrent within hours.The higher peak flows predicted by theEnvironment Agency are – potentially – badnews for Bath, which is already prone toflooding and has a high concentration ofhomes and businesses in its river corridor.In spring 2009 <strong>Atkins</strong> was commissionedto prepare a flood risk management strategyfor Bath & North East Somerset Council. Thestudy identifies ways in which sites at risk offlooding can be built on without increasingthe risk of flooding elsewhere. The key isbalancing the need for economicdevelopment with flood protection.“A lot of the future brownfielddevelopment sites in Bath are along theriver frontage,” explains Savage. “Thepossible effects of different flood events onthe city had to be considered and optionsexplored for mitigating those events,through planning policy, with both on-siteand off-site solutions.”Flood management is one of the trickiestareas of strategic planning. Water has to gosomewhere – but where? Raising the heightof river walls provides protection in theimmediate locality, but it’s an unsightlysolution and – critically – it simply shunts theproblem further downstream.Large-scale engineering fixes of this sortdo have their place, but building them isdisruptive. And, like Bath’s proposedsubterranean flood channel, which wasruled out on cost grounds, massive civilworks can come with a prohibitive price tag.“By appraising all of the differentoptions, a flexible strategy was developedthat could provide greater protection overtime – and a funding strategy was launchedthat involved developers making acontribution,” says Savage.One of the approaches was to embedresilience in each individual development byproviding space for water on site and raisingbuildings to minimise the impact of flooding.“That can have an impact ondevelopment viability, though,” says Savage.“A more strategic approach is required aswell. This involves providing a larger floodstorage area upstream. Developerscontribute in proportion to the volume ofwater storage they would have needed toprovide on site. It solves the problem in a farmore cost-effective way.”“When you look at issues such as climatechange, a lot of emphasis is placed on hardtechnology – smart gadgets, smartinfrastructure,” says Savage. “Whereasplanning is more like soft infrastructure –it’s about dealing with people, dealing withconcerns, finding mechanisms to workthrough these different problems. A planis a good way to do that.”Planning for climate change meanstaking account of the possibilities andthen guiding development through local,regional and national planningmechanisms. The key is an ability to assessrisks that may lie years or even decadesaway. And as the strategy for Bathconfirms, creative approaches are likely tobecome increasingly important.21

Cities: The peoplePARADOXCities in the developing world are struggling to copewith an unprecedented influx of people. Tackling slumsis one of the challenges facing city planners, but municipalcentres also need to address how sustainable urbanisationcan sustain an ever-expanding population, by devisingsolutions that will remain viable across the decades.22The issue of how to design cities has vexedplanners since the days of the pyramids. Thecompeting forces of commerce, environment,geography and culture must all be reconciled as a citygrows beyond its beginnings. Ensuring that thepopulation is safe, fed and free to move around, whilepositioning it to develop economically, has in essencebeen the goal of city planners through the ages.“Cities have been around for 4,000 years,” saysLars Reutersward, director of the global division at UNHabitat. “Of course, some of them have a militarybasis or strategic importance, but fundamentally mostof them grew up to provide a market for products andideas: universities and religions and industry.”In the 21st century, city design and urban planninghas had to keep pace with enormous social andeconomic changes. That’s particularly evident now inthe developing world, where high population growthand massive wealth inequality fuel urban developmenton an exponential basis.In that context, designing urban systems hasbecome as much an art as a science. Cities need to beable to change, while their geography and make-upneed to respond to indeterminate, unpredictable forces.From Lagos, Mumbai and Delhi to Dhaka, as wellas Shanghai and Jakarta, there is clearly the need for anew type of development approach.Reutersward believes that the need to adaptplanning techniques is pressing: “Over one billionpeople need to be adequately housed in developingcountries. So that will require not only technicalimprovements in construction techniques but alsolooking more closely at the evolving needs of a city.”Holistic planningAfrica represents the biggest challenge for urbanplanners. Cities such as Lagos, Kampala and Luandaare all experiencing rampant population growth. Butwhile they attract more people and investment, thestrain is beginning to show. Are urban plans for a cityof two million really fit for purpose when thepopulation has swelled to eight million? For <strong>Atkins</strong>,finding a solution to this has become the biggestsingle planning challenge in emerging cities.Looking forward three decades, the fastestgrowingcities will be those in Africa and Asia. In manyAfrican countries, for instance, planning authoritiesbelieve a longer-term approach is needed and somehave taken the pre-emptive step of asking for amasterplan to oversee and control growth.Paul White, director of planning at <strong>Atkins</strong>, hasworked on many urban regeneration projects. He saysthat, because it’s impossible to put a definitive time onthe lifespan of any plan, the focus for planners islargely on setting the direction of travel.Having worked on several sustainable projects,White and his team have perfected the process ofconsulting the relevant parties – local authorities,planning consultants and community leaders – inorder to set up a “base camp” and produce a basicinitial design plan. “After a few years you revisit this tomake sure that the assumptions you made arecorrect,” he says. “Once that’s done, you can readjustit, and the likelihood is that planners modify that insome way because circumstances will change.Ultimately, it would be pretty unusual for a plan toremain live and current for the duration.”

citysolutionssustainableurbanisation

“The big challenge is to design a plan with the resourcesnecessary to provide for aN INCREASING population – onethat is going to grow exponentially in the next 10 years”And that’s the key point: sustainable development has atits centre the idea that what works now – the rail networkcan carry the desired number of passengers, say – may notwork in ten years’ time. Flexibility of design thereforebecomes just as important as keeping costs under control.In White’s view, the vibrancy of a transitional city can beboth a blessing – no successful city can continue to thrivewithout attracting new migrants – and a curse.“The big challenge is to design a plan with the resourcesnecessary to provide for an increasing population – one thatis going to grow exponentially in the next 10 years.”The twin issues of housing and transport pose the mostcomplex challenges. Providing sustainable housing is onething, but it is complicated by the demographic changes thatmost developing countries are experiencing. Increasedeconomic activity inevitably leads to a growth in theprofessional class. “The key with transitional cites that act ashoneypots is dealing with the housing issue,” says White.Given the predominance of rural-to-urban migration (insome cases caused by civil war or unemployment), peoplehave flocked from other parts of the country and from thecountryside into cities. As a result, a large proportion ofthose people are housed in poor conditions often in suburbswith little transport or sanitation to serve their needs.“What we really have to do is to produce a plan forthe future development of the city,” says White. That planbegins to take shape during the “optioneering” phase,where a number of scenarios are explored.“We have a workshop while we’re doing that, and weget stakeholders to help formulate those options. Then weevaluate and develop a range of criteria in terms of theenvironmental impact, transport benefits, socio-economiceffects, financial side-effects and so on,” White explains.This is refined so that a plan emerges which has a fairmeasure of support from the various stakeholders. Takehousing, for example: in previous years, the approach totackling widespread slums would be to demolish them.A look at how some urban development has proceededin some parts of China would give an illustration of thetemptation to do that. But that is only a short-term solution.What happens in 10 years when more slums have grownin their place? White believes that a more sustainable andintegrated approach must be taken.“The plan presents a combination of keeping the existingslums in situ but upgrading them, with some demolition andredevelopment where we thought it was necessary to, forinstance, put in new transport routes,” White says.“What we were trying to do was to strike a balancebetween maintaining communities and the necessarymodernisation that the city needs to undergo,” he adds.Setting an exampleThe Middle East, and the UAE in particular, is leading theway with many cutting-edge economic and urban advances.Suhar in Oman is a compelling example of how sympatheticdevelopment planning can produce robust solutions thatlast. Previously the ancient capital of the sultanate, Suhar sitssome 200km north of Muscat. As a coastal city it offereddevelopers the chance to build on existing transport linksand, in common with other <strong>Atkins</strong> sustainable developmentprojects, the plan was based on extensive consultation withcommunity representatives.Suhar is primarily a trading city, a port with historic linksand significant opportunity to expand. Any plan to develop itwould need to take this into account. The main driverswould be the development of downstream industries linkedto the port, as well as forthcoming infrastructure such asSuhar, Oman: a sympathetic andsustainable approach to planningfor population growth.the Gulf Cooperation Council railway linking the major UAEhubs, which is under construction.For <strong>Atkins</strong>, the key challenge of Suhar has to bepreserving its appeal to the population as a place to livewhile allowing as much room for the port and the associatedindustries to flourish. So far the signs are positive: tradevolumes continue to grow at the port while a few blocks tothe north the foundation stone for the city’s new universityhas been laid.Suhar’s sustainable approach to growth – puttingflexible transport and industrial development at its heart– is mirrored elsewhere in the Middle East. Bahrain, forexample, has recently kicked off its national planning anddevelopment strategy, which will see the kingdom build180,000 housing units in the next 20 years to cope with thekingdom’s projected population growth. It’s a clear indicationthat authorities in the region are aware that sustainable,flexible development strategies are needed to harness andcapitalise on growth – and planners are waking up to theneed to plan for 2050 and beyond.

Beyond thegreat wallThe typical “Westerners going abroad” view of tourismin China is being redefined with the ongoing rise of thecountry’s middle class. New approaches are emergingthat seek to meet this new demand while embracinglocal diversity and retaining individual identity.

changingtourismbuilding for themodern travellerTourism in China is changing. The middle classesare on the rise, bringing with them greaterdisposable incomes as well as a genuine interest inexploring their home territory. This is prompting amini-boom in local tourism for communities andhistorically significant sites throughout the country.For Steven Ng, technical director for urbanplanning with <strong>Atkins</strong> in China, the masterplan hasbecome a vital tool when establishing a tourismstrategy that addresses these changing demands.“It’s a question of balance,” he says. “Visitorsincreasingly expect authenticity in their travels. Anymasterplan must bring out the best in a local space.”Ng points to the recently completed Xunliao(Oceania Point) resort in the east of Shenzhen City,in southern China, which was designed around16km of coastline: “It was planning gold – youcould even compare it to the Gold Coast inAustralia in aesthetic terms. Behind the resort arethe mountains and padi fields, and within the deltathe salt and fresh water meet.”In order to maximise the natural surroundingassets, the plan allows for sea views for 60 per centof properties and mountain views for 30 per cent.“We consulted the nearby fishing communitiesand made the rivers a feature of thedevelopment,” Ng explains. “We even built afishing village into the development based ontraditional Chinese architecture.”Sometimes a resort’s existing assets will alsowork on a practical level. For example, mangrovesare attractive indigenous flora but they also help toprevent coastal erosion and not stripping themturned out to be a sensible strategy for the Xunliaoplanners. Unobtrusive solutions such as these tendto be preferable.Xunliao had to fulfil some requests for privatespaces, so the plan clustered spots throughout tocreate public and private areas.“The gaps between the 16km stretch are long,which encourages people to stay in the publicareas,”says Ng. Clustering does not always work,he adds, but in aesthetic terms it is “preferable tofences or barbed wire”.Harmonious solutions within the planningframework also needed to extend to transport.Road and air networks for Xunliao were enhanced.“We looked at developing ferry links tosurrounding coastal cites such as Hong Kong andMacau to open it up as a destination,” says Ng.Tourism from within this huge country is not tobe underestimated. For example, this development,which was planned for 60,000 people, can surviveon the local market alone and hotels are filling upwith business conference travellers.Developing destinationsChina’s vast size means that it’s possible toexperience very different environments without everleaving the country. For example, many northernbasedChinese people are keen to travel to warmerareas. Ng says that many Chinese people are verypatriotic and keen to experience the highlyindividual corners of their fascinating country.Ng worked on a Chinese development called XiaSha and points out that the local ethnic Keija cultureignited collective imaginations. Alongside the scoresof professionals – the economists, tourismconsultants, property development consultants,hotel specialists and golf course consultants – thatworked on Xia Sha and developments like it, theteam also engaged ethnically Keijan designers andplanners for their specific knowledge.Xunliao in China:a new tourism andresort destinationthat includes beaches,mangroves, padi fieldsand fishing villages.16km ofcoastline willhelp to turnXunliao inthe PearlRiver Deltainto a primedestinationfor China’sgrowinginternaltourist trade.“We wanted to preserve and celebrate the localdiversity by developing land that didn’t have animpact on cultural heritage. After all, many of thecommunity wanted to stay. What was important isthat we didn’t just drop something into the area,”says Ng. As a consequence, circular buildings, whichare integral to this ancient culture, were introducedinto the development as a core attraction. Ng saysthat these celebrate the culture of sitting in a circleand eating with the family.China is becoming ever more affluent, he adds.Its economy may still be evolving on the worldstage, but this growing tourist infrastructureillustrates the country’s rapid growth.“We look at the whole natural resource of anarea and we plan our development to fit in withthat,” says Richard Alvey, managing director ofenvironmental planning with <strong>Atkins</strong>. “It’s vital tomake sure that a tourism-based project has a senseof context, place and character.”In the highly competitive world of tourismit is not only responsible to take into account thelocal surroundings but it also makes goodbusiness sense. Creating a unique tourist identityis essential and can be of great importance toany developing economy.27

esilientcitiesdesigns for changeREADY FOR ANYTHING:THE CITIES OF THE FUTURE28Cities are feeling the strain and it’s not likely to get anyeasier. According to projections, the world’s population willcontinue to grow until at least 2050. Complex environmentalchanges will alter the climate in which cities operate, the supplyand availability of materials that are used in cities’ constructionand maintenance, the energy that is required for theireconomies to function, the supply of food and clean water fortheir inhabitants and the provision of sustainable modes oftransport to enable mobility.New and existing cities will encounter shocks and stressesassociated with environmental change, energy scarcity andglobal population – issues that remain difficult to predict reliably.Only by attempting to understand these complexities willplanners, designers and creators of sustainable societies be ableto successfully meet these challenges head on in the future.Changing climates, increasing populations andvarying industry trends are affecting how citiesfunction. Can masterplanners design for thesedevelopments? And how can a city’s resilience andadaptability be maximised when it comes to futureunknowns? Nick Roberts, managing director of<strong>Atkins</strong>’ environment business, addresses these keyquestions in a round-table discussion with colleaguesElspeth Finch, futures director, and Guy Mercer,associate director for land and development.Why do we need these discussions andwhat do we mean by resilient and adaptive cities?Nick Roberts: “We need to have these discussions to explorethe relationships between socio-economic, political, cultural andenvironmental change and their potential effects on cities overlong periods. A resilient city is in essence about adaptability anddiversity. The ability of a city to change, morph, adapt andreinvent itself continually is the key to sustainability.”Elspeth Finch: “There is a huge range of factors that affecta city’s resilience and adaptability. Cities need to be physicallydurable to withstand the physical shocks associated with futureclimate change. This can mean designing mitigation measuresto guard against potential floods or securing food supplies incase of long-term water shortages. They also need to be diversein terms of their sources of energy, the economy and publicinstitutions because with greater diversity comes an increasedability to survive and bounce back from these shocks.”

“The question is: how do we plan for adapTATIONcity being built with a 50- to 100-year lifespan?”30Roberts: “That’s right, and I’d alsosuggest that, with increasingly global flowsof people and capital, it’s important toconsider resilience in economic and socialterms, as well as the more obvious physicaldurability and issues related to climatechange. As we’ve seen in recent years,economic shocks can have major effectson cities and these can often be muchharder to recover from than naturaldisasters. And, as inequalities in wealthbecome greater in many cities, it’s importantthat we start to think about how this couldgenerate conflict between different socialgroups and affect resilience.”Guy Mercer: “The impact of globalinfluences is enormous and increasing everyday. We need to take the global dimensioninto account when looking at a city, or wecan’t look at the resilience. The ability of acity to adapt and be resilient is as much anissue about commerce as it is about peopleand where they want to live.”What are the essentials that everyresilient and adaptive city must have?Mercer: “Food, water, energy and shelterare just some vital ingredients that enablea city to thrive economically and socially.A resilient city would seek to feed peoplewithin its own effective boundaries and beless reliant on global food chains.“It will use local building materials forshelter and sustainable energy supplies todrive its economy and provide people withbasic sustenance.“By delivering essentials locally, citiesmake themselves less vulnerable toexternal economic and environmental issues.A secure flow of goods – in and out – suchas water, sewerage, food etc, make up thebasis of resilience.”Finch: “I agree that we need to sourcelocally, especially as this can help to reducecarbon emissions. But I think we need toremember that, because we’re living in avery globalised world, there are manyexternal influences that will actually affectthe ability of that city to adapt and thrive.It’s impossible for cities to build walls aroundthemselves and think that they’ll be secure.Many cities have varying degrees of controlover their own wealth, their own direction.So, unless we take the global dimension intoaccount when looking at a city, we can’tlook at the resilience.”Mercer: ”The key factor here is making surethat we have reliable and diverse supplychains for a wide range of essentials: food,water, energy, building supplies etc.”Finch: “That’s very true and, in order tounderstand what the city needs to beresilient (from an infrastructure context), wealso need to understand how these thingsconnect, because a city is made up ofdifferent components: transport, energysupplies, buildings etc. If one element goesdown, it can have major implications.Understanding these dependencies is criticalto understanding resilience.“Linked to this, I’d suggest that someredundancy needs to be built into a system.This means that, if one element iscompromised, other parts of the system canfill in for it. I think my one comment aboutwhat infrastructure needs to be in termsof being resilient and adaptive is ‘simple’.“We can’t know exactly what thefuture will hold. If infrastructure istoo over-designed and specific, it makesit very difficult to adapt for differentways of working when change happens,as it always does eventually.”Roberts: “You’re absolutely right. Thesimplicity of infrastructure and its abilityto be used in different ways leads to areal challenge in the way we approachdesign. It’s about saying: ‘How do weprovide something that’s inherently simpleso that it has an adaptive use?’“resilient citiesshouldn’t onlybe aboutdesigning aninsurancepolicy againstnegative shocks– it’s not justan additionalcost. It’s anopportunityto buildbetter livingenvironments”“This principle extends to buildings aswell as infrastructure where requirementsfor the type and size of buildings cansometimes change incredibly quickly witheconomic and technological developments.If you consider Victorian housing stock inLondon, it has been remarkably adaptableto changes in society. It is a relatively simpledesign, but it has been able toaccommodate huge changes in family sizefor over a century. This has undoubtedlyplayed some part in supporting London’sresilience to economic and social change.”Finch: “If you look at cities such asToronto and Helsinki, they have much widertemperature fluctuations than London andvery different climates. As a consequence,their infrastructure has to be much simplerand more flexible. It has to be resilient tobeing under snow for five months of theyear. It’s all about the levels of tolerancethat we design for. Designing for thattolerance may be more expensive, but howdo you weigh up those upfront costsagainst the potential cost to a city of severeweather, the ferocity and frequency ofwhich we cannot be sure?”Mercer: ”Without a doubt, being adaptiveor resilient will cost and the economicquestions are complex. There are otherelements (beyond infrastructure alone) thatneed to be understood in the context of anadaptive and resilient city.“For instance, recreational and openspaces are good examples of land that has aclear economic value which is often notdirectly accounted for in terms of a financialyield per square metre or traditional rentalincome, yet they form an inherent part of amodern city. Parks are not consideredexamples of getting maximum return oninvestment, but they draw in value for otherparts of the city’s economy and that valuestands to be at risk if a city is subject tounforeseen shocks and stresses.”How will adaptive and resilient citieslook across the world?Finch: “I think the first question we need toask is: what does each city need to beresilient to? So should we be looking atresilience to flooding or water shortages,which will affect food? Is it legislativechanges, is it political unrest – is it majorpopulation growth?”

TO these societal and local issues for a31Mercer: “In other words: what are themajor threats to a city?”Finch: “Exactly. Cities in different parts ofthe world will face different issues ofresilience and adaptability. We need tounderstand the local climate and thecultural elements.“Understanding the local context andhow people want to live in that particularenvironment (including the family structureand how that needs to be supportedthrough the built infrastructure) isimportant to enable the resilience of thatcity from a societal perspective. We needto learn lessons from the past andimplement those for future design.”Roberts: “The question is: how do weplan for adaptation to these societal andlocal issues for a city that’s being built witha 50- to 100-year lifespan?”Mercer: “If we had to look back over five or50 years, what would the evaluation criteriafor a successful city be? What is a successfulcity from a resilience perspective? I don’tthink we’re asking the right questions yet.We have a feel for what such a place shouldlook like in crude terms, but we don’t knowwhat the success criteria are. This needs tobe considered now and, however imperfectsuch criteria might be at the outset, it willneed to be adopted and refined as we learnfrom lessons throughout our journey.”Finch: “But in some ways there could be areally simple answer to that: a fundamentalaspect of a resilient city is that it’s a placewhere lots of people want to live and willcontinue to want to live 50 years from now.Keeping things simple, if you want to livethere rather than having to live there, it’sprobably because of the choice of jobs, theattractiveness of the urban realm and so on– there are lots of different aspects.Whether or not people want to live in a cityis a good measure of its adaptability and,therefore, its potential resilience.”Mercer: “Here’s a dilemma: to make a placereally attractive/resilient costs money. Howhow are you going to achieve that in thedeveloping world and at the rate required?”Finch: “That’s the question isn’t it? No onething will make a resilient city and the costsinvolved will be different for every city. Inmost cases, though, the upfront costs ofbuilding for resilience should be smallagainst the potential savings. We need tocome up with innovative ways in whichthese investments can be funded, especiallyin the developing world.“But I think what this discussion hashighlighted is that building resilient citiesshouldn’t only be about designing aninsurance policy against negative shocks –it’s not just an additional cost. It’s alsoan opportunity to build better livingenvironments, improve environmentalquality, encourage diverse communities tolive together and secure a better economythat improves everyone’s living standards.That’s got to be the key to a resilient city.”Mercer: “And, ultimately, how far can weor should we take resilience? What shouldwe be realistically looking to control andadapt, and how should we be factoring thisinto our cities of the future, at the sametime making them places in which we wantto live – and can afford to live?”More work on this topic will be exploredby our Cities Board in the comingmonths and we look forward to sharingthis with our clients and partners as weembark on this journey together.

movingforwardlearning frompublic transport<strong>Atkins</strong>’ proposal forBirmingham New StreetStation included bothcomprehensiveredevelopment andreorganisation ofinterchange facilities.All change:public transportThe condition of railway stations across the UK is under fire,criticised for failing to meet basic standards in terms of facilities,appearance and ease of access. Faced with funding difficultiesinherent to the current economic climate, what can we learnfrom successful overseas public transport models?32Some railway station schemes are simply abouttransport, says Warwick Lowe, transport development directorat <strong>Atkins</strong>. They improve the concourse, add a few shops andclean up the immediate environment – but that’s about it.Others do more. They take the chance to regenerate an area,spark economic activity and bring communities to life.“There is this concept in home design of indoor-outdoorliving, where the outdoors is brought indoors and theindoors is brought outdoors. That is how it should be forstations,” says Lowe. “The ideal railway station ends up in alarge open square, with space on all sides for cafés, thatpedestrians, cyclists and buses can all navigate easily,allowing people to flow naturally into the city. It blurs the linebetween where the station ends and where the city begins.”Lowe highlights <strong>Atkins</strong>’ recent proposals for Belfast’sGreat Victoria Street Station, Euston in central London andBarking in east London. Each, he says, offers tremendouspossibilities as catalysts for urban improvement.“Most of the time, proposals focus on cosmeticimprovements because they generate more passengerrevenue than when it was falling down. At Belfast, Barking,and Euston we have proposed new public spaces that allowthe station to function better as part of the community,” hesays. “It’s not only about adding a few shops to the stations.The real benefits are in making the station the hub for localactivity; improving the flow of the area.”There are lessons to be learned from successful urbanstation projects abroad, too. Luca Bertolini, professor ofurban and regional planning at the University of Amsterdam,says that the best examples can be found in Asia.“Tokyo station is the icon for this kind of idea. Stations inJapan are urban centres. Urban ‘centres’ and ‘stations’ aretotally intertwined. These places have great potential forcities, for accessibility and sustainability. But the challenge isto develop them as places, not just as an interchange,” saysBertolini. “Building outside the city is easier, but inside youalready have other things already there. If you can integratethem, you can offer much more to people.”Go with the flowGreat Victoria Street Station dates from 1839, but wasclosed in 1976. A new station was opened near the originalsite in 1995. But, according to Lowe, it remains hiddenfrom the main street, one of Belfast’s most prestigiousthoroughfares. The most important rail services (servingDublin, for instance) operate from Belfast Central, which isnot as central as Victoria Street.The masterplan, created by <strong>Atkins</strong> and which Lowehelped to draw up, “re-establishes a footprint on Belfast’smain street and reconnects the station with thecommunities around it,” he says. The area behind the stationused to be at the centre of a turf war between Protestantsand Catholics, but is now available for redevelopment,allowing boulevards and commercial spaces to beconstructed. The plan also improves the station itself,adding bus bays, platforms and facilities such as waitingareas and toilets.“It’s about improving the functionality of the station andits connectivity with the city, and exploiting the former yardsfor maximum commercial return. The station needs a flowthat boosts economic activity. The easier you make it forpeople to get from A to B, the more likely they are to makethat journey and generate economic activity,” says Lowe.It is vital, he adds, to create open, walkable spacesaround station developments. He cites the example of thenew St Pancras as a scheme that has done this successfully.

In 2009 Only twothirdsof customerswere satisfied withBritain’s stations.Just halF of customerswere satisfied withstation facilities.[Source: “Better Rail Stations Report 2009”,UK Department for Transport]

34 “What you need to create is some space that allows awider circumference of development to happen. There hasbeen an ongoing debate about preserving the piazzabetween King’s Cross and St Pancras because the land isworth so much. But they were right to keep it because itallows St Pancras to flow better with the local area.”Developing areasThe scheme at Barking is similarly ambitious, involvingplans not only for the station but also the town itself.Although Barking is well connected with rail services toThe refurbishment of Barkingstation is intended to provideoffice space in tandem withleisure and retail areas.London and the building itself is grade II listed, the stationitself is unwelcoming and the surrounding area isunderdeveloped, according to Paul Reynolds, a senior urbandesigner at <strong>Atkins</strong>. There is an opportunity to clean up theconcourse, taking out poor-quality shops and removingadvertising hoardings that block the windows, and torefine the area outside allowing better access for pedestriansand cyclists. At the same time, the station’s refurbishmentcould be used to spur development of the wider area.“The regeneration masterplan for the area around thestation is designed to develop a stronger office market,improve the quality of its retail stock and address areas ofstrategic focus,” says Reynolds. “The idea is to provide officespace in tandem with retail and leisure areas. There is verylittle to do in Barking town centre in the evening and thepopulation is quite transient as things stand. Theregeneration is part of a plan to attract a demographic witha higher degree of permanence to the town.”The blueprint for Euston does something similar,although on a larger scale. For example, it creates a newentrance to the station, rationalises the bus station outfront and improves disability access. It also takes theunderground entrance out of the railway station so thatTube passengers no longer clog up the main concourse.“There’s a huge opportunity to have a look at the wholearea,” says Reynolds. <strong>Atkins</strong> produced the plan on behalfof Sydney and London Properties, which owns tower blocksat the front of the station. “There’s plenty of scope formasterplanning that would come about from theopportunities initiated by the station development.”Finding the fundingThe obvious problem with the station development-asregenerationmodel, however, is that it is more expensivethan a station-only project. Moreover, regenerating a wholearea inevitably involves a larger range of stakeholders,including landowners, transport authorities, regionaldevelopment bodies, councils and mayors.